Introduction

Bone morphogenetic proteins (BMP) are reported to be

associated with proliferation and differentiation of numerous types

of cells (1,2). In a previous in vitro study,

bone morphogenetic protein-7 (BMP-7) was shown to promote

odontogenic differentiation of stem cells derived from dental pulp

(3). BMP-7 at concentrations of 50

and 100 ng/ml was shown to produce dental pulp stem cells that

tended toward odontogenic differentiation through the Smad5

signaling pathway and did not significantly interrupt cell

proliferation in vitro (3). A

previous report showed that BMP-7 made the fibroblasts derived from

a human dermis differentiate into osteoblasts and promoted

osteogenesis (4). Similarly, BMP-7

enhanced the human-induced pluripotent stem cells' differentiation

potential (5).

Mesenchymal stromal cells from intraoral region drew

great attention in tissue regeneration because they can be achieved

with a minimally invasive maneuver (6). For several years, gingiva-derived stem

cells have been used for various purposes (7–9).

Mesenchymal gingiva-derived stem cells repaired calvarial and

mandibular defects, and gingival tissue can serve as a source for

stem cell therapy (10).

Gingiva-derived stem cells can aggregate into tight

three-dimensional spheroids, which can produce their own matrix

(8). Gingiva-derived stem cells have

demonstrated to have immunoregulatory effects by promoting Treg

cell polarization, inducing T-cell apoptosis and suppressing the

in vitro polarization of Th17 cell (9). Gingiva-derived stem cells encapsulated

in an alginate/hyaluronic acid three-dimensional scaffold have been

applied (7). Gingiva-derived stem

cells have been used for bone and nerve regeneration (11). This study was aimed at examining the

time-dependent impact of BMP-7 on changes of gene expression in the

stem cells. mRNA sequencing and data analysis were performed along

with gene ontology and pathway analysis. Quantitative analysis of

mRNA using real-time polymerase chain reactions of ColI, Sp7 and

IBSP and western blot analysis of collagen I, osterix and bone

sialoprotein as well as β-actin were performed. The purpose of this

study was to demonstrate the effects of BMP-7 on the

gingiva-derived stem cells.

Materials and methods

Stem cells collected from human

gingivae

Human gingivae were collected from healthy

participants following the method used in a previous study

(12). Approval of this study was

obtained from the Institutional Review Board at Seoul St Mary's

Hospital (KC18SESI0199). The participants signed the written

consent, and all of the procedures completed in this study followed

the relevant regulations and guidelines.

Concisely, de-epithelialization of the obtained

tissues was performed, and the tissues were dissected into

1–2-mm2 fragments. The tissues were dissolved using

collagenase type IV (Sigma-Aldrich Co., St. Louis, MO, USA) at 2

mg/ml and dispase (Sigma-Aldrich Co.) at 1 mg/ml. The resultant

products was filtered with a 70-µm cell strainer (Falcon, BD

Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA), and sterile

phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, Welgene, Daegu, Korea) was applied

to remove the non-adherent cells after incubation for 24 h.

Treatment of the stem cells with

BMP-7

The gingivae-derived stem cells were then treated

with BMP-7 (CYT-333; ProSpec Co., Nagoya, Japan) at a final

concentration of 100 ng/ml. The control group was loaded with the

same concentration of the dissolving media of acetic acid. The

cells were obtained at 3 or 24 h.

Evaluation of the secretion of human

vascular endothelial growth factor for paracrine effect

Secretion of human vascular endothelial growth

factor was determined at 3 and 24 h using a kit

(Quantikine® ELISA, cat. no. DVE00; R&D Systems,

Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA). Preparation of the samples and

reagents were performed following the manufacturer's

recommendations. The resulting products were diluted ten times. The

differences of absorbance levels at 450 and 570 nm were used for

the evaluation of paracrine effects.

RNA isolation

Isolation of total RNA was done using Trizol reagent

(Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA, USA). Quality of RNA was evaluated

by bioanalyzer (Agilent 2100; Agilent Technologies, Amstelveen, The

Netherlands) using the nanochip (RNA 6000, Agilent Technologies),

and quantification of RNA was carried out using a spectrophotometer

(ND-2000, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA).

Library preparation and

sequencing

Library of control and test RNAs were built using

SMARTer Stranded RNA-Seq Kit (Clontech Laboratories, Inc., Palo

Alto, CA, USA) following the manufacturer's instructions.

Concisely, each 2 µg total RNA was prepared and reacted with

magnetic beads coated with oligo-dT. Washing solution was used to

remove other RNAs except mRNA. Initiation of library production was

performed by the random hybridization of starter/stopper

heterodimers to the poly(A) RNA still attached to the magnetic

beads. Illumina-compatible linker sequences were part of these

starter/stopper heterodimers. The starter was extended to the next

hybridized heterodimer by a single-tube reverse transcription and

ligation reaction. The stopper ligated the newly-synthesized cDNA

insert. The library was released by second strand synthesis from

the beads and the library was amplified with introduction of

barcodes. Paired-end 100 sequencing performed high-throughput

sequencing using HiSeq 2500 (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA,

USA).

Data analysis

TopHat software tool was used to map mRNA-Seq reads

tool in order to gain the alignment file (13). Counts from unique and multiple

alignments were used to determine differentially expressed gene

from coverage in Bedtools (14).

Quantile-quantile normalization method was applied to process the

read count data were processed from EdgeR within Rusing

Bioconductor (15). Cufflinks were

used for assembling transcripts, estimating their abundances and

revealing differential expression of genes or isoforms with the

alignment files. The expression level of the gene regions was

determined by applying method of fragments per kilobase of exon per

million fragments. Gene classification was based on searches

performed by DAVID (http://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov/) (16). Pathway analysis was performed on

differentially expressed genes basted on the Kyoto encyclopedia of

genes and genome pathway databases (17).

Quantification by real-time polymerase

chain reaction

Total RNA was isolated from cultured stem cells

using Trizol (Invitrogen Corp.) and was reverse transcribed. Primer

sequences were as follows: Collagen I Forward

5′:CCAGAAGAACTGGTACATCAGCAA-3′, Reverse

5′:CGCCATACTCGAACTGGAATC-3′, Sp7 Forward

5′:TTGCCAATCACTCTCTTTACC-3′, Reverse 5′: GAGATACCCAAGCCCAGAAT-3′,

IBSP Forward 5′:AGGACTGCCAGAGGAAGCAA-3′, Reverse 5′:

CACAGGCCATTCCCAAAATG-3′ and β-actin Forward 5′:

TGGCACCCAGCACAATGAA-3′ and Reverse 5′:

CTAAGTCATAGTCCGCCTAGAAGCA-3′. The housekeeping gene was β-actin in

this study, which was used for normalization. SYBR Green Real-Time

PCR Master Mixes (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA, USA) was used

to detect mRNA expression through a real-time polymerase chain

reaction following the manufacturer's manual.

Western blot analysis

Samples were rinsed with ice-cold PBS twice and

treated with a lysis buffer at 3 and 24 h for 30 min. The lysates

were centrifuged at 13,500 rpm for 15 min at 4°C . Separation of

the samples were performed by gel electrophoresis

(Mini-PROTEAN® TGX™ Precast Gels; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA,

USA), transblotted to the membranes (Immun-Blot®;

Bio-Rad) and immunoblotted with the corresponding antibodies and

the detection kits. Primary antibodies against collagen I (ab6308;

Abcam, MA, USA), RUNX2 (ab76956; Abcam), OCN (ab13418; Abcam), Sp7

transcription factor (ab22552; Abcam), bone sialoprotein (ab52128,

Abcam), β-actin (SC-516102; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Dallas,

TX, USA) and secondary antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz

Biotechnology. The protein expressions of Collagen I, Sp7, bone

sialoprotein and β-actin was quantitatively analyzed using with

image processing program (ImageJ, National Institutes of Health,

Bethesda, MD, USA).

Alkaline phosphatase activity

In the test groups, the stem cells were treated with

BMP-7 for 3 or 24 h. Then media were changed to osteogenic media

composed of α-MEM (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA), containing 200 mM

of L-glutamine (Sigma-Aldrich Co.), 10 mM of ascorbic acid

2-phosphate (Sigma-Aldrich Co.), 100 µg/ml of streptomycin

(Sigma-Aldrich Co.), 15% fetal bovine serum (Gibco), 100 U/ml of

penicillin, 2 mg/ml of glycerophosphate disodium salt hydrate, and

38 µg/ml of dexamethasone. A commercially available kit (K412-500;

BioVision, Inc., Milpitas, CA, USA) were used for the analysis of

alkaline phosphatase activity on Day 7.

Statistical analysis

The data were presented as mean ± standard

deviations of the results. A test of normality was conducted with

Shapiro-Wilk, and differences among the groups were analyzed by

one-way analysis of variance with Tukey's post hoc test using a

statistical package (SPSS 12 for Windows; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL,

USA).P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically

significant difference.

Results

Evaluation of gene ontology and

pathway analysis

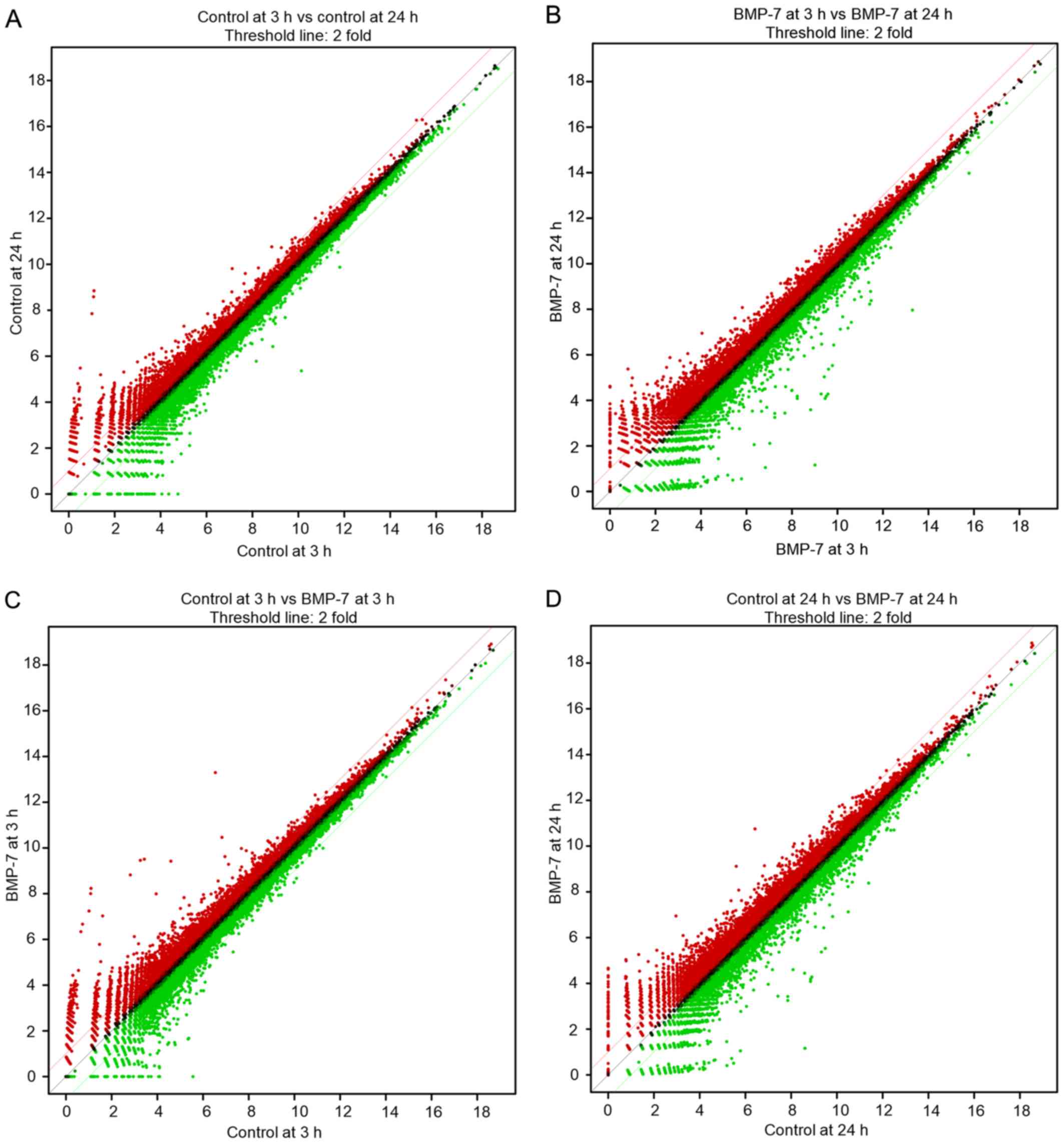

Differentially expressed mRNAs in this study is a

total of 25,737. The scatter plots displaying differentially

expressed mRNAs, are illustrated in Fig.

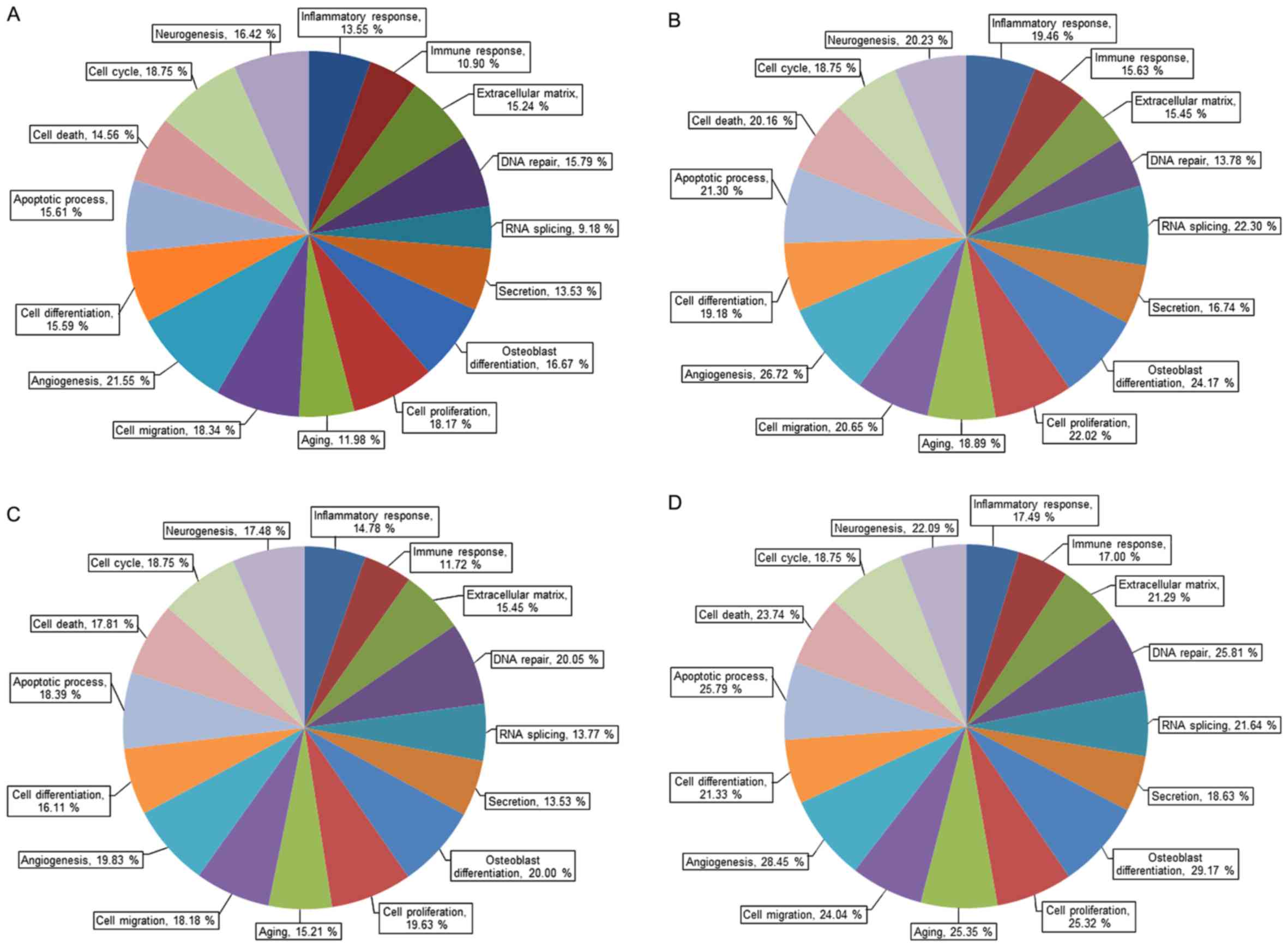

1. Gene ontology analysis of mRNA expression is categorized by

its importance and the selection criteria were fold change ≥1.3 and

log2 normalized read counts ≥4 (Fig.

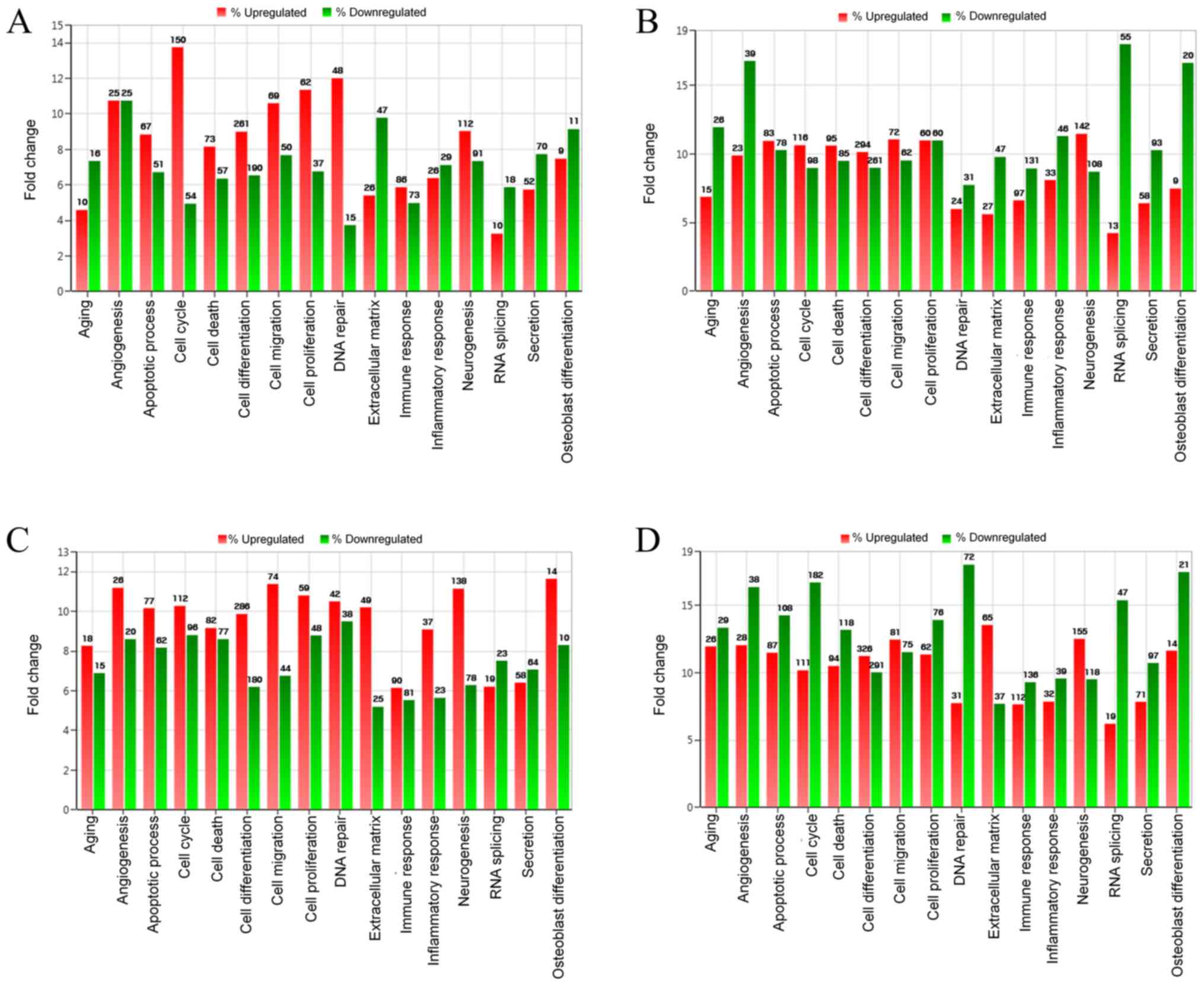

2). Fig. 3 shows gene ontology

analysis of mRNA expression by upregulation and downregulation

(fold change of 1.3 or greater, log2 normalized read counts of 4 or

greater were selected).

The results of differentially expressed mRNA related

to osteoblast differentiation, are displayed in Table I. To analyze the effects of

incubation time on the cultured cells, the comparisons were

performed between the control at 24 and at 3 h. The investigation

demonstrated that upregulation was seen in 9 mRNAs and

downregulation was noted in 11 mRNAs. Comparisons between BMP-7 at

24 h and BMP-7 at 3 h showed that 9 mRNAs were upregulated and 20

were downregulated. Comparisons between BMP-7 at 3 h and the

control at 3 h exhibited upregulation of 14 mRNAs and

downregulation of 10 mRNAs. When the results of BMP-7 at 24 h were

compared with the control at 24 h, upregulation of 14 mRNAs and

downregulation of 21 mRNAs were seen.

| Table I.Differentially expressed mRNA related

to osteoblast differentiation (fold change of 1.3 or greater, log2

normalized read counts ≥4 were selected). |

Table I.

Differentially expressed mRNA related

to osteoblast differentiation (fold change of 1.3 or greater, log2

normalized read counts ≥4 were selected).

| Gene symbol | Control-24

h/Control-3 h | Gene symbol | BMP7-24 h/BMP7-3

h | Gene symbol | BMP7-3 h/Control-3

h | Gene symbol | BMP7-24

h/Control-24 h |

|---|

| AMELX | 2.167 | BMP4 | 2.073 | LRRC17 | 3.748 | WNT11 | 3.428 |

| SOX8 | 1.932 | ALPL | 2.069 | WNT11 | 2.907 | ALPL | 2.946 |

| HDAC4 | 1.743 | WNT11 | 1.900 | SOX8 | 2.304 | BMP4 | 2.805 |

| CHRD | 1.523 | SHOX2 | 1.800 | BMP3 | 2.150 | SHOX2 | 2.684 |

| NF1 | 1.478 | RUNX2 | 1.734 | HDAC4 | 1.808 | RUNX2 | 1.829 |

| DNAJC13 | 1.415 | TMSB4Y | 1.592 | AMELX | 1.741 | TWIST1 | 1.723 |

| BMP2 | 1.407 | WNT3 | 1.476 | PTH1R | 1.568 | NOG | 1.709 |

| GLI2 | 1.365 | CREB3L1 | 1.418 | DNAJC13 | 1.447 | SMO | 1.518 |

| SMAD3 | 1.301 | SNAI2 | 1.309 | BMP4 | 1.445 | PTHLH | 1.514 |

| PENK | 0.761 | SMAD3 | 0.752 | NF1 | 1.440 | IFT80 | 1.513 |

| SNAI2 | 0.691 | HSPE1 | 0.731 | VCAN | 1.434 | ITGA11 | 1.390 |

| SEMA7A | 0.655 | IGFBP5 | 0.718 | SHOX2 | 1.400 | WNT3 | 1.389 |

| HSPE1 | 0.654 | FASN | 0.706 | BMP2 | 1.390 | SNAI2 | 1.386 |

| SNAI1 | 0.638 | RSL1D1 | 0.674 | IFT80 | 1.321 | PENK | 1.347 |

| EPHA2 | 0.634 | IGFBP3 | 0.661 | SNAI2 | 0.732 | PHB | 0.749 |

| PTHLH | 0.592 | FHL2 | 0.639 | TMSB4Y | 0.718 | LIMD1 | 0.749 |

| JUNB | 0.585 | FZD1 | 0.636 | JUNB | 0.693 | RSL1D1 | 0.724 |

| IGFBP3 | 0.585 | SYNCRIP | 0.628 | EPHA2 | 0.662 | GLI2 | 0.714 |

| NOG | 0.371 | ALYREF | 0.626 | FBL | 0.659 | SMAD3 | 0.682 |

| ALPL | 0.312 | MYBBP1A | 0.596 | MEF2D | 0.643 | FBL | 0.680 |

|

|

| GTPBP4 | 0.579 | NOG | 0.581 | SNAI1 | 0.666 |

|

|

| AMELX | 0.577 | SEMA7A | 0.516 | SYNCRIP | 0.661 |

|

|

| SEMA7A | 0.519 | ALPL | 0.444 | FASN | 0.656 |

|

|

| BMP3 | 0.511 | SNAI1 | 0.439 | FHL2 | 0.638 |

|

|

| DDX21 | 0.507 |

|

| MYBBP1A | 0.637 |

|

|

| MSX2 | 0.440 |

|

| CHRD | 0.629 |

|

|

| CBFB | 0.427 |

|

| FZD1 | 0.623 |

|

|

| LRRC17 | 0.268 |

|

| ALYREF | 0.606 |

|

|

| SOX8 | 0.057 |

|

| GTPBP4 | 0.562 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| DDX21 | 0.526 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| CBFB | 0.519 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| MSX2 | 0.512 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| AMELX | 0.464 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| SEMA7A | 0.409 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| SOX8 | 0.068 |

Secretion of human vascular

endothelial growth factor

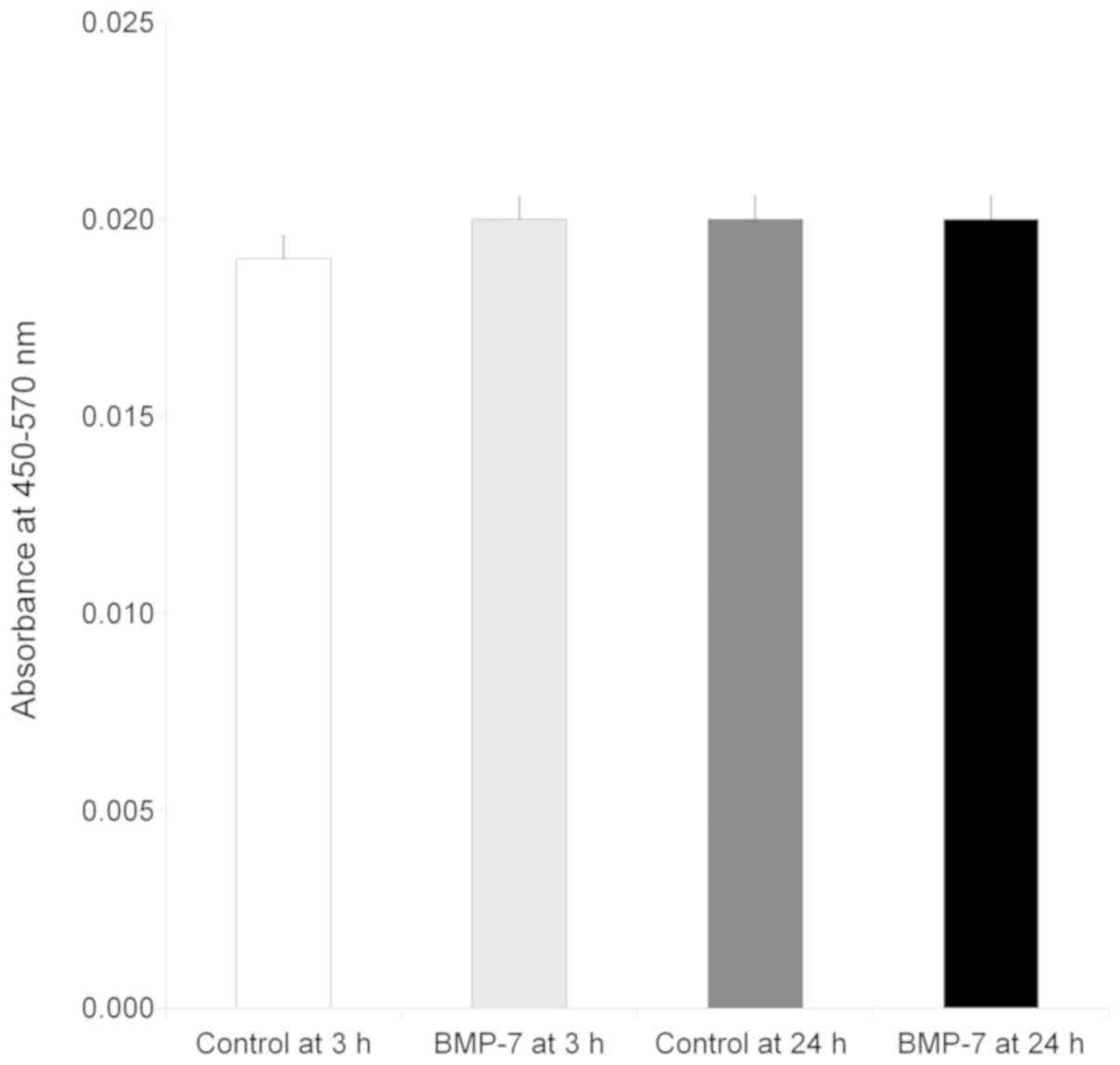

The results clearly demonstrated that the vascular

endothelial growth factor was secreted at 3 and 24 h irrespective

of culture period (Fig. 4). No

significant change in secretion of the vascular endothelial growth

factor was seen at 3 h with the addition of bone morphogenetic

protein (P>0.05). Similarly, no statistically significant

changes were noted with the loading of bone morphogenetic protein

at 24 h (P>0.05).

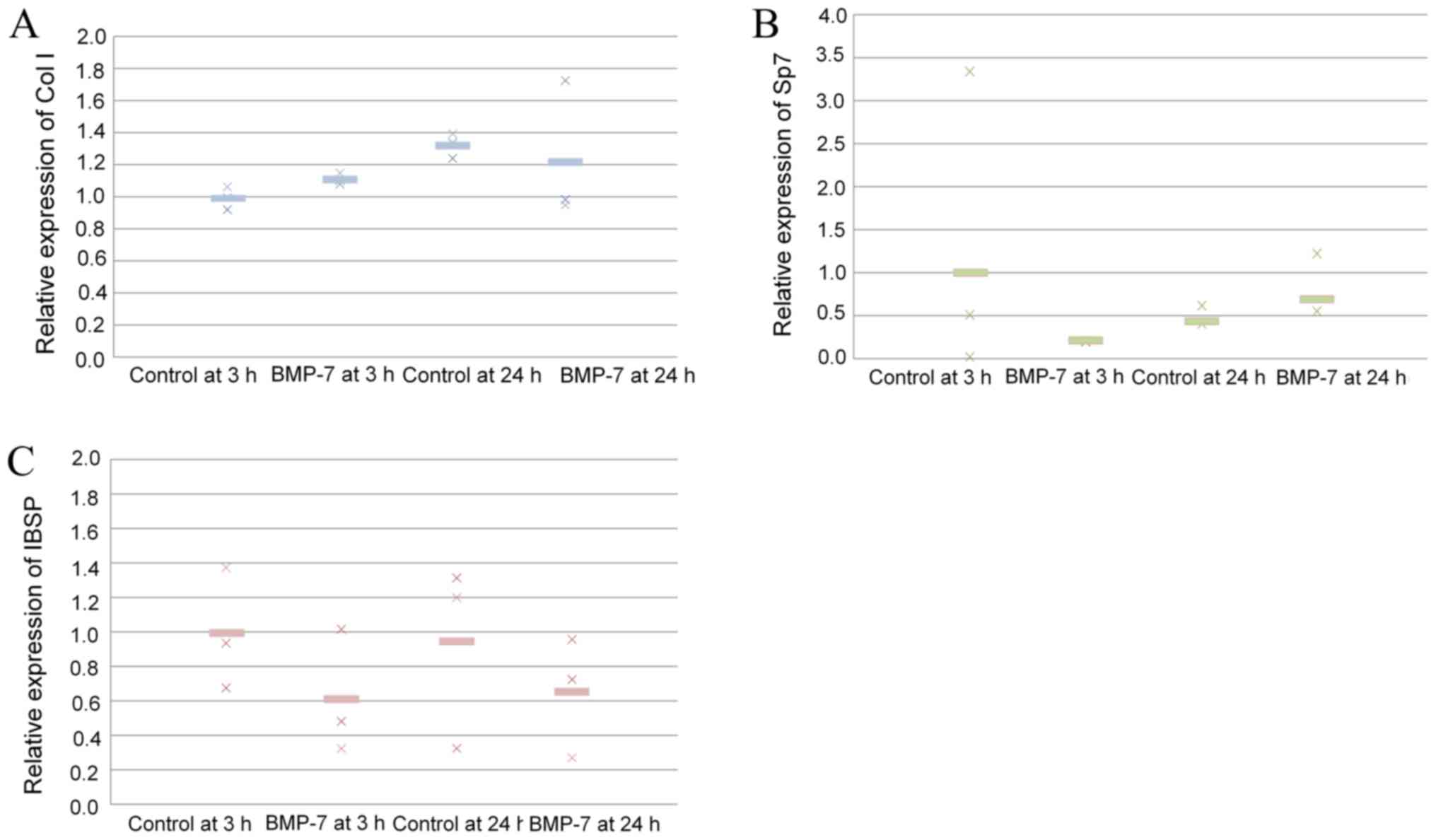

Validation of mRNA expression

Quantitative real-time PCR revealed that mRNA levels

of collagen I were higher in the 24-h control group than in 3-h

control group (P>0.05; Fig.

5A). Application of BMP-7 increased the expression of collagen

I at 3 and 24 h. The results showed that application of BMP-7 at 24

h produced a decrease of Sp7 (P>0.05; Fig. 5B). The results showed that

application of BMP-7 at 24 h showed a decrease of IBSP, but no

significant differences were noted (P>0.05; Fig. 5C).

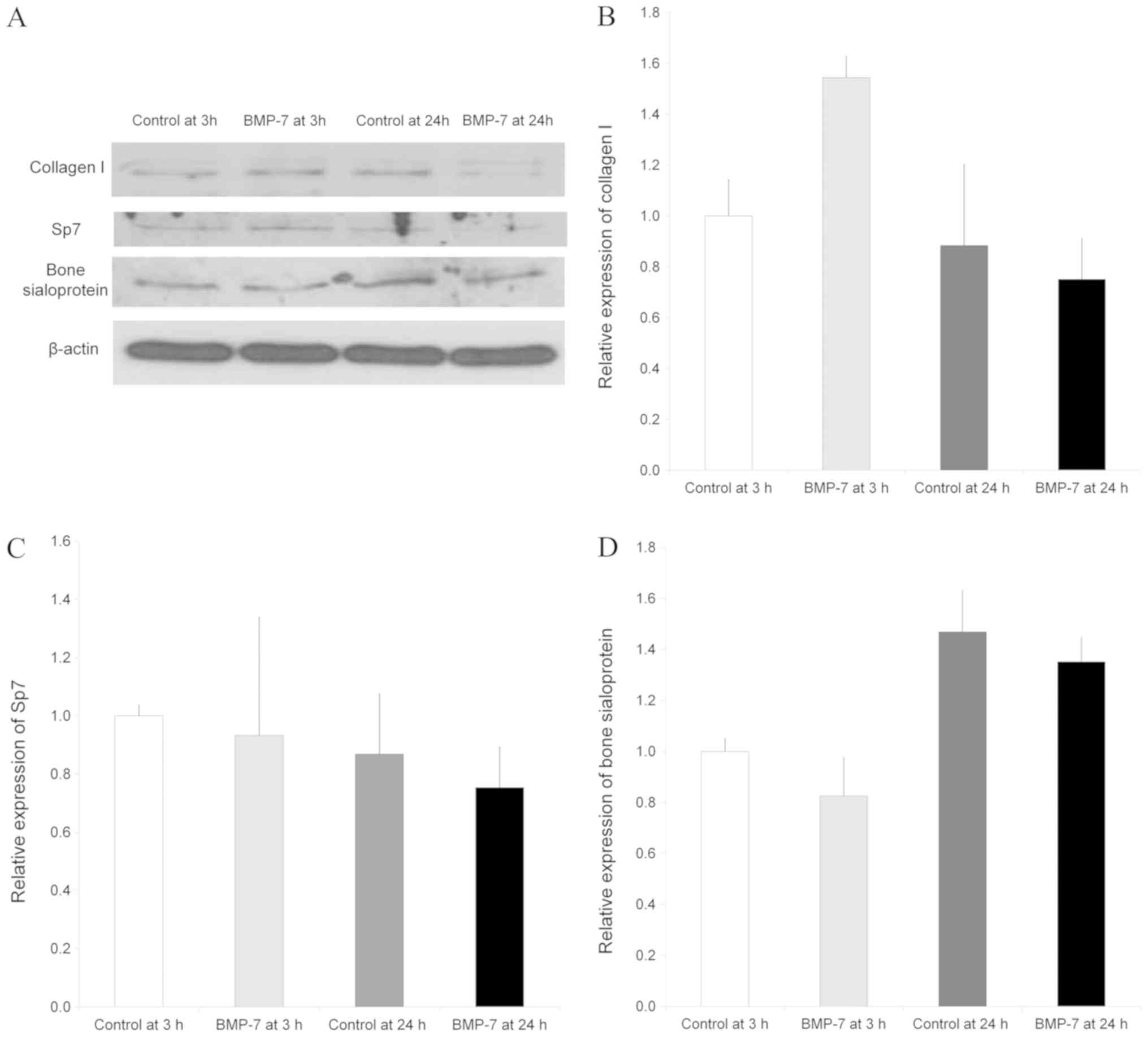

Western blot analysis

Western blot analysis was done to analyze protein

expression of collagen I, Sp7 and bone sialoprotein following the

application with BMP-7 at 3 and 24 h compared with the untreated

control group at 3 and 24 h (Fig.

6A). Normalization of the protein expressions showed that the

control at 24 h showed 88.4±31.8% expression of collagen I, and the

group treated with BMP-7 yielded 154.5±8.2% and 75.1±16.0% of

expression of collagen I at 3 and 24 h, respectively, compared to

control values at 3 h as a baseline of 100% (100.0±14.3%)

(P>0.05, Fig. 6B).

The expression of Sp7 in the control group at 24 h

did not show significant change compared with the control at 3 h.

Normalization of the protein expressions revealed that the control

at 24 h showed 86.8±20.7% expression of Sp7, and the group treated

with BMP-7 yielded 93.2±40.6% and 75.4±13.9% of expression of Sp7

at 3 and 24 h, respectively, compared to control values at 3 h as a

baseline of 100% (100.0±3.6%) (P>0.05, Fig. 6C).

The relative expression of bone sialoprotein is

shown in Fig. 6C. Normalization of

the protein expressions demonstrated that the control at 24 h

showed 146.8±16.4% expression of bone sialoprotein, and the group

treated with BMP-7 yielded 82.5±15.1% and 135.1±9.6% of expression

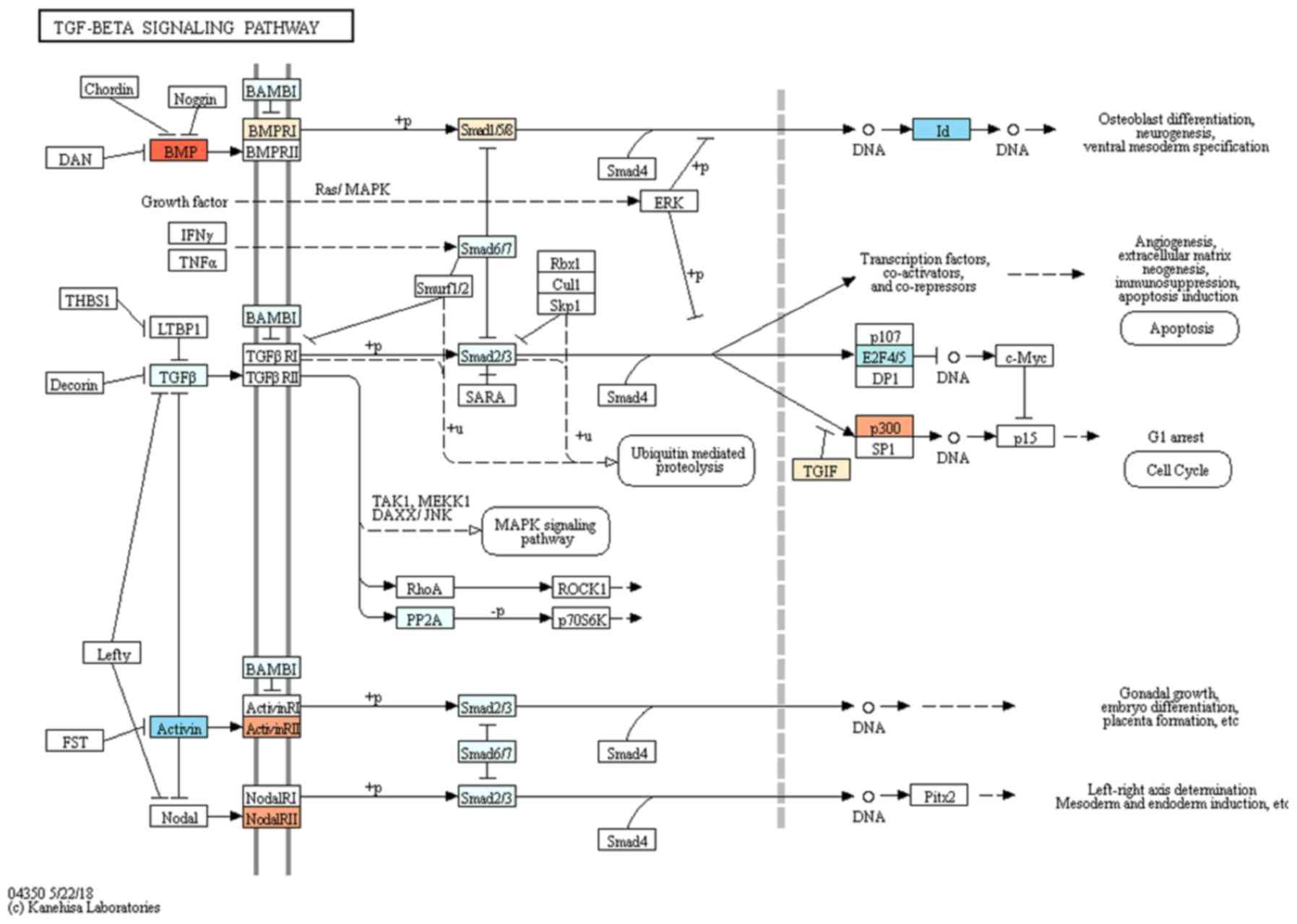

of bone sialoprotein at 3 and 24 h, respectively, when the control

value at 3 h were considered 100% (100.0±5.0%). TGF-β signaling

pathway was associated with the target genes selected for

osteoblast differentiation (Fig.

7).

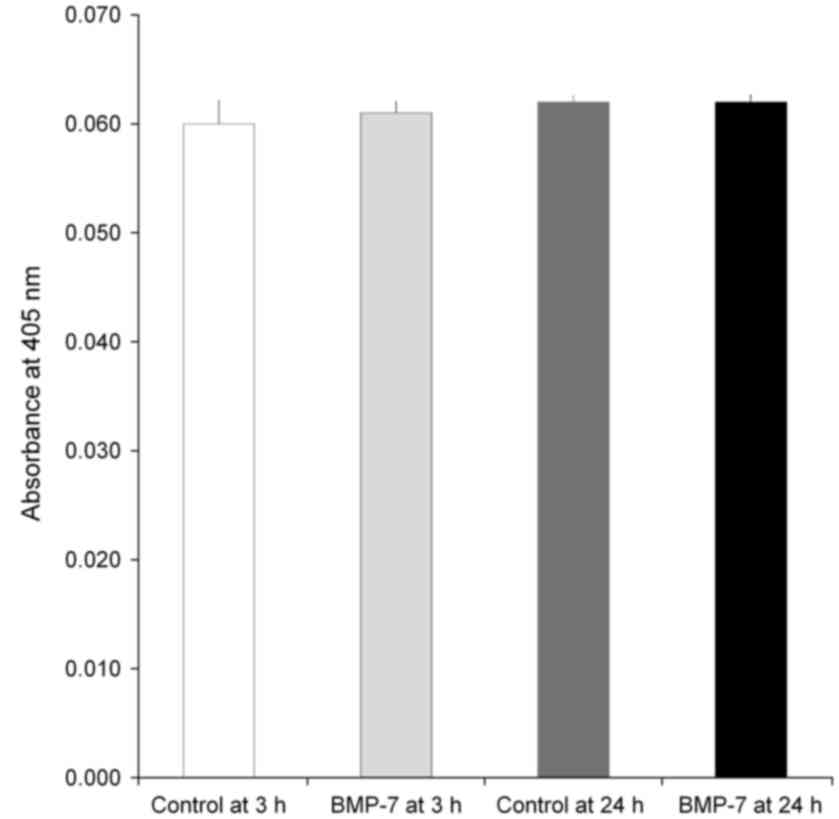

Alkaline phosphatase activity

The data of the alkaline phosphatase activity assays

at Day 7 are demonstrated in Fig. 8.

The absorbance values at 405 nm at Day 7 for control at 3 h, BMP-7

at 3 h, control at 24 h and BMP-7 at 24 h were 0.060±0.002,

0.061±0.001, 0.062±0.001, and 0.062±0.001, respectively

(P>0.05).

Discussion

In this report, we evaluated the effects of BMP-7 on

stem cells under predetermined concentrations at 3 and 24 h. mRNA

sequencing and validation of the expression was done with

qualitative real-time PCR and Western blot analysis. It was seen

that the application of BMP-7 produced increased expression of

collagen I of human gingiva-derived mesenchymal stem cells.

Application with gingiva-derived stem cell inhibited

macrophage foam cell formation and reduction of inflammatory

macrophage activation (18).

Previous reports showed that long incubation of gingiva-derived

stem cells lead to neural precursor cells in vitro (19). Three-dimensional bioprinted

constructs made with gingiva-derived stem cells promoted facial

nerve regeneration (8).

BMP-7 expressing stem-cell sheets were applied in

the previous studies (20–22). In a previous report, BMP-7

overexpressing adenovirus vector was used to transfect mesenchymal

stem cells (22). In a non-union

fracture model, BMP-7 expressing mesenchymal stem cells enhanced

bone regeneration (20). Similarly,

BMP-7 expressing stem cells produced enhanced bone healing in

critical-sized defects when compared with the control stem cell

sheets (23). Moreover, application

of BMP-7 overexpressing stem cells derived from bone marrow

decelerated the development of disc degeneration (21).

It is widely accepted that differentiation of

mesenchymal stem cells is associated with gene transcription and

courses of molecular signaling (24). Researchers previously used RNA

sequencing to analyze transcriptional profiling of osteoblast

differentiation (25). Moreover, RNA

sequencing and quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain

reactions were applied for characterization of three-dimensional

organoids (26). RNA Sequencing has

also been applied to compare the differences between mesenchymal

stem cells derived from bone marrow from healthy control and

diseased participants (27).

Researchers previously tested the functionality of mesenchymal stem

cells, the precursors of osteoblasts, using RNA sequencing to

measure the epigenetic changes with aging (28). This study tested gingiva-derived stem

cells' responsiveness to BMP-7 showed differentially expressed mRNA

related to osteoblast differentiation in each group.

Researchers previously tested the expression of

osteoblast-associated genes and proteins, including COL1A1, Runx2,

IBSP, SPARC, SPP1 and BGALP (29).

In this study, several gene expressions were tested in mesenchymal

stem cells, including Runx2, Sp7 and collagen I (29–31).

Researchers previously demonstrated that romidepsin promoted

osteogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells and that

it showed increased SP7 (Osterix) and alkaline phosphatase

expression (32). They also showed

that transfection of Runx2/SP7 enhanced the osteogenic

differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells (33). This study showed that BMP-7

upregulates genes related to osteoblast differentiation, including

collagen I, in gingiva-derived stem cells. Alkaline phosphatase

activity is considered an early-stage marker for osteoblast

differentiation, the lack of difference may be dues to various

reasons including the treatment time of BMP-7 and the stage of

tested cells (34,35).

Conclusively, the effects of BMP-7 on stem cells

were assessed using mRNA sequencing, and the validation of the

expression was done with quantitative real-time polymerase chain

reactions and Western blot analysis. The short-term application of

BMP-7 produced an increased expression of collagen I, which was

related to target genes chosen for osteoblast differentiation. This

study may provide new insights into the role of BMP-7 using mRNA

sequencing.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Thε present study was supported by Basic Science

Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea

(NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science, Information and

Communication Technology & Future Planning (Grant no.

NRF-2017R1A1A1A05001307).

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are

included in this published article.

Authors' contributions

HL, SM, YS, YP, and JP contributed to study

conception and design. HL, SM, YS, YP, and JP performed the

experiments; HL, SM, YS, YP, and JP analyzed the data and HL, SM,

YS, YP, and JP wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed the

manuscript.

Ethical approval and consent to

participate

The protocol of the study was reviewed and the

Institutional Review Board of the Catholic University of Korea,

College of Medicine approved the design of this study

(KC18SESI0199). Written informed consent was gathered from the

participants according to the Act on Legal Codes for Biomedical

Ethics and Safety and the Declaration of Helsinki.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Park JB: Use of bone morphogenetic

proteins in sinus augmentation procedure. J Craniofac Surg.

20:1501–1503. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Park JB: Effects of the combination of

fibroblast growth factor-2 and bone morphogenetic protein-2 on the

proliferation and differentiation of osteoprecursor cells. Adv Clin

Exp Med. 23:463–467. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Zhu L, Ma J, Mu R, Zhu R, Chen F, Wei X,

Shi X, Zang S and Jin L: Bone morphogenetic protein 7 promotes

odontogenic differentiation of dental pulp stem cells in vitro.

Life Sci. 202:175–181. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Chen F, Bi D, Cao G, Cheng C, Ma S, Liu Y

and Cheng K: Bone morphogenetic protein 7-transduced human

dermal-derived fibroblast cells differentiate into osteoblasts and

form bone in vivo. Connect Tissue Res. 59:223–232. 2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Jovanovic VM, Salti A, Tilleman H, Zega K,

Jukic MM, Zou H, Friedel RH, Prakash N, Blaess S, Edenhofer F and

Brodski C: BMP/SMAD pathway promotes neurogenesis of midbrain

dopaminergic neurons in vivo and in human induced pluripotent and

neural stem cells. J Neurosci. 38:1662–1676. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Soundara Rajan T, Giacoppo S, Scionti D,

Diomede F, Grassi G, Pollastro F, Piattelli A, Bramanti P, Mazzon E

and Trubiani O: Cannabidiol activates neuronal precursor genes in

human gingival mesenchymal stromal cells. J Cell Biochem.

118:1531–1546. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Ansari S, Diniz IM, Chen C, Sarrion P,

Tamayol A, Wu BM and Moshaverinia A: Human periodontal ligament-

and gingiva-derived mesenchymal stem cells promote nerve

regeneration when encapsulated in alginate/hyaluronic acid 3D

scaffold. Adv Healthc Mater. 6:2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Zhang Q, Nguyen PD, Shi S, Burrell JC,

Cullen DK and Le AD: 3D bio-printed scaffold-free nerve constructs

with human gingiva-derived mesenchymal stem cells promote rat

facial nerve regeneration. Sci Rep. 8:66342018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Yang R, Yu T, Liu D, Shi S and Zhou Y:

Hydrogen sulfide promotes immunomodulation of gingiva-derived

mesenchymal stem cells via the Fas/FasL coupling pathway. Stem Cell

Res Ther. 9:622018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Wang F, Yu M, Yan X, Wen Y, Zeng Q, Yue W,

Yang P and Pei X: Gingiva-derived mesenchymal stem cell-mediated

therapeutic approach for bone tissue regeneration. Stem Cells Dev.

20:2093–2102. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Lee SI, Ko Y and Park JB: Evaluation of

the shape, viability, stemness and osteogenic differentiation of

cell spheroids formed from human gingiva-derived stem cells and

osteoprecursor cells. Exp Ther Med. 13:3467–3473. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Jin SH, Lee JE, Yun JH, Kim I, Ko Y and

Park JB: Isolation and characterization of human mesenchymal stem

cells from gingival connective tissue. J Periodontal Res.

50:461–467. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Trapnell C, Pachter L and Salzberg SL:

TopHat: Discovering splice junctions with RNA-Seq. Bioinformatics.

25:1105–1111. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Quinlan AR and Hall IM: BEDTools: A

flexible suite of utilities for comparing genomic features.

Bioinformatics. 26:841–842. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Gentleman RC, Carey VJ, Bates DM, Bolstad

B, Dettling M, Dudoit S, Ellis B, Gautier L, Ge Y, Gentry J, et al:

Bioconductor: Open software development for computational biology

and bioinformatics. Genome Biol. 5:R802004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Huang DW, Sherman BT, Tan Q, Collins JR,

Alvord WG, Roayaei J, Stephens R, Baseler MW, Lane HC and Lempicki

RA: The DAVID gene functional classification tool: A novel

biological module-centric algorithm to functionally analyze large

gene lists. Genome Biol. 8:R1832007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Kanehisa M, Furumichi M, Tanabe M, Sato Y

and Morishima K: KEGG: new perspectives on genomes, pathways,

diseases and drugs. Nucleic Acids Res. 45:D353–D361. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Zhang X, Huang F, Li W, Dang JL, Yuan J,

Wang J, Zeng DL, Sun CX, Liu YY, Ao Q, et al: Human gingiva-derived

mesenchymal stem cells modulate monocytes/macrophages and alleviate

atherosclerosis. Front Immunol. 9:8782018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Rajan TS, Scionti D, Diomede F, Piattelli

A, Bramanti P, Mazzon E and Trubiani O: Prolonged expansion induces

spontaneous neural progenitor differentiation from human

gingiva-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Cell Reprogram. 19:389–401.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Song J, Kim Y, Kweon OK and Kang BJ: Use

of stem-cell sheets expressing bone morphogenetic protein-7 in the

management of a nonunion radial fracture in a Toy Poodle. J Vet

Sci. 18:555–558. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Liao JC: Cell therapy using bone

marrow-derived stem cell overexpressing BMP-7 for degenerative

discs in a rat tail disc model. Int J Mol Sci. 17:E1472016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Yan X, Zhou Z, Guo L, Zeng Z, Guo Z, Shao

Q and Xu W: BMP7-overexpressing bone marrow-derived mesenchymal

stem cells (BMSCs) are more effective than wild-type BMSCs in

healing fractures. Exp Ther Med. 16:1381–1388. 2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Kim Y, Kang BJ, Kim WH, Yun HS and Kweon

OK: Evaluation of mesenchymal stem cell sheets overexpressing BMP-7

in canine critical-sized bone defects. Int J Mol Sci. 19:E20732018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Fakhry M, Hamade E, Badran B, Buchet R and

Magne D: Molecular mechanisms of mesenchymal stem cell

differentiation towards osteoblasts. World J Stem Cells. 5:136–148.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Khayal LA, Grünhagen J, Provazník I,

Mundlos S, Kornak U, Robinson PN and Ott CE: Transcriptional

profiling of murine osteoblast differentiation based on RNA-seq

expression analyses. Bone. 113:29–40. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Wiener DJ, Basak O, Asra P, Boonekamp KE,

Kretzschmar K, Papaspyropoulos A and Clevers H: Establishment and

characterization of a canine keratinocyte organoid culture system.

Vet Dermatol. 29:375–e126. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Sargent A, Shano G, Karl M, Garrison E,

Miller C and Miller RH: Transcriptional profiling of mesenchymal

stem cells identifies distinct neuroimmune pathways altered by CNS

disease. Int J Stem Cells. 11:48–60. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Del Real A, Pérez-Campo FM, Fernández AF,

Sañudo C, Ibarbia CG, Pérez-Núñez MI, Criekinge WV, Braspenning M,

Alonso MA, Fraga MF and Riancho JA: Differential analysis of

genome-wide methylation and gene expression in mesenchymal stem

cells of patients with fractures and osteoarthritis. Epigenetics.

12:113–122. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Baird A, Lindsay T, Everett A, Iyemere V,

Paterson YZ, McClellan A, Henson FMD and Guest DJ: Osteoblast

differentiation of equine induced pluripotent stem cells. Biol

Open. 7:bio0335142018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Barone A, Toti P, Funel N, Campani D and

Covani U: Expression of SP7, RUNX1, DLX5, and CTNNB1 in human

mesenchymal stem cells cultured on xenogeneic bone substitute as

compared with machined titanium. Implant Dent. 23:407–415.

2014.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Hajizadeh N, Madani ZS, Zabihi E, Golpour

M, Zahedpasha A and Mohammadnia M: Effect of MTA and CEM on

mineralization-associated gene expression in stem cells derived

from apical papilla. Iran Endod J. 13:94–101. 2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Ali D, Chalisserry EP, Manikandan M, Hamam

R, Alfayez M, Kassem M, Aldahmash A and Alajez NM: Romidepsin

promotes osteogenic and adipocytic differentiation of human

mesenchymal stem cells through inhibition of histondeacetylase

activity. Stem Cells Int. 2018:23795462018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Kim HJ, Park JS, Yi SW, Oh HJ, Kim JH and

Park KH: Sequential transfection of RUNX2/SP7 and ATF4 coated onto

dexamethasone-loaded nanospheresenhances osteogenesis. Sci Rep.

8:14472018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Prins HJ, Braat AK, Gawlitta D, Dhert WJ,

Egan DA, Tijssen-Slump E, Yuan H, Coffer PJ, Rozemuller H and

Martens AC: In vitro induction of alkaline phosphatase levels

predicts in vivo bone forming capacity of human bone marrow stromal

cells. Stem Cell Res. 12:428–440. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Lu C, Xing Z, Yu YY, Colnot C, Miclau T

and Marcucio RS: Recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-7

enhances fracture healing in an ischemic environment. J Orthop Res.

28:687–696. 2010.PubMed/NCBI

|