Introduction

Approximately 30% of patients with cirrhosis have

oesophageal varices at the time of diagnosis; this proportion

increases with time and reaches 90% after ~10 years (1). Patients with oesophageal varices have a

high tendency to develop bleeding. Only 10-20% of variceal bleeding

occurs from gastric varices, but the associated outcome is worse

than that of bleeding from oesophageal varices (2-5).

Patients surviving a variceal bleed are at high risk of rebleeding

(>60% in the first year) and the mortality of each rebleeding

episode is ~20% (6). Therefore,

prevention of recurrent variceal bleeding is important for patients

with cirrhosis.

For secondary prophylaxis of variceal bleeding, the

goal of improving outcomes is evolving, since therapy in these

cases attempts to reduce the risk of death, and thus prevent the

onset of complications of cirrhosis that may lead to death

(1). The treatment effectiveness of

secondary preventions, including endoscopic ligation or endoscopic

sclerotherapy (ES), drug therapies [non-selective β-blockers (NSBB)

with or without isosorbide mononitrate (ISMN)] and transjugular

intrahepatic portosystemic shunts (TIPS) is an area of interest,

but at present, a firm consensus as to the most effective treatment

has not been reached. Several randomized controlled trials (RCTs)

have investigated treatment outcomes in terms of mortality,

complications and adverse effects (7-12).

A previous study compared endoscopic variceal ligation (EVL) with a

combination of EVL and nadolol and identified that adverse effects

more frequently occurred in the EVL plus nadolol group (0.03 vs.

33%) (12). Another trial compared

nadolol plus ISMN alone with EVL plus the drug combination and

observed that the combination of EVL and drugs led to more adverse

effects (62 vs. 32%), but there were no significant differences in

either mortality or the causes of death (11). However, a previous direct

meta-analysis comprising 925 patients comparing endoscopic therapy

with a combination of BB and endoscopic therapy identified that

mortality at 24 months was significantly lower in the combined

treatment group (13). In addition

to inconsistent results among the previous trials and analyses, to

the best of our knowledge, there has been no previous network

meta-analysis to compare treatment outcomes. Therefore, the present

study was performed to compare the effectiveness of standard

treatments for the secondary prevention of variceal bleeding in

patients with cirrhosis through a network meta-analysis. The

specific treatments studied were TIPS, endoscopic therapy (EVL

alone or ES alone), a combination of EVL and ES, a combination of

EVL/ES and NSBB (propranolol and nadolol) with or without ISMN, as

well as a combination of NSBB and ISMN.

Materials and methods

Literature search

Searches were performed in the electronic PubMed,

Cochrane Library, Embase and Web of Science databases in February

2018. The following search terms were used: ‘Cirrhotic patients’,

‘patients with cirrhosis’, ‘liver cirrhosis’, ‘haemorrhage’,

‘bleeding’, ‘rebleeding’, ‘variceal’, ‘oesophageal varices’,

‘endoscopic variceal ligation’, ‘endoscopic band ligation’,

‘endoscopic ligation’, ‘endoscopic sclerotherapy’, ‘sclerotherapy’,

‘endoscopic therapy’, ‘vasoconstrictors’, ‘venodilators’,

‘adrenergic beta antagonist’, ‘adrenergic-beta antagonist’,

‘adrenergic beta-antagonist’, ‘adrenergic-beta-antagonist’,

‘nitrate’, ‘beta-blocker’, ‘isosorbide mononitrate’, ‘placebo’,

‘TIPS’, ‘transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt’ and

‘randomized controlled trial’. Manual searches of reference lists

of relevant articles were also performed to identify additional

studies. Only RCTs were included.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

RCTs, irrespective of publication status, were

included if they investigated endoscopic therapy with various

combinations of NSBB and ISMN, or TIPS alone among adult patients

with cirrhosis, who had at least one previous episode of upper

gastrointestinal bleeding. Trials fulfilling the following criteria

were excluded: i) Focus on primary prevention of variceal bleeding;

ii) inclusion of pediatric patients or patients without cirrhosis;

iii) comparison of only one of the aforementioned treatment

regimens with other treatment(s), as it was impossible to make a

network comparison; or iv) a clearly irrelevant topic, e.g.

nutrition after variceal bleeding.

Study selection

Only RCTs whose reports were available in English or

Chinese were included. If a trial was designed with more than two

treatment arms, at least two of the arms had to match the scope of

the present study.

Data extraction

According to the newly published guidelines of the

American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) and

consensus (14), therapies for

secondary prophylaxis must account for the presence or absence of

other complications of cirrhosis. In patients with a low risk of

death (those with variceal haemorrhage as the sole complication of

cirrhosis), the objective of therapy should be the prevention of an

additional complication, whereas in patients with a high risk of

death (those with variceal haemorrhage and other decompensating

events), the objective of therapy should be to improve survival

(15,16). Mortality (overall mortality,

mortality due to rebleeding and mortality due to liver failure),

treatment failure and complications (bleeding from gastroesophageal

ulcer) were analyzed.

Data of treatment failure were analyzed when clearly

stated in the literature, with exclusion of data that satisfied

certain criteria but lacked declaration of treatment failure.

Authors of the included trials were not approached for further data

due to the large number of RCTs selected and acquisition of

adequate data associated with treatment outcomes. The primary

outcomes were overall mortality, mortality due to rebleeding,

including but not limited to recurrent variceal bleeding and

mortality due to liver failure. Overall mortality was defined as

death that occurred during the trial treatment or follow-up caused

by disease progression or treatment complications. Secondary

outcomes were treatment failure and bleeding from gastroesophageal

ulcers, including but not limited to post-banding ulcers.

Methodological quality

A bias assessment was performed for the included

trials by evaluating randomization, completion of trials and

blinding. The major targets were concealment randomization,

participant blinding, health care provider blinding, data collector

blinding, outcome assessor blinding and early trial cessation.

Randomization was considered concealed if it

involved a third independent party or person not involved in the

treatment of patients, opaque sealed envelopes or a similar method.

Trials were not considered to feature early cessation unless

premature termination was specifically announced in the

article.

Statistical analysis

The odds ratio (OR) was used to denote the results

with a 95% CI, indicating the strength of association between

treatments and outcomes. An OR<1 represents the benefit of the

comparison group compared with the control group. Pooled ORs and

their 95% CIs were also calculated. Statistical significance was

established with a two-sided P<0.05 or a CI that did not include

a value of 1. The risk ratio was not used to measure outcomes due

to limited data regarding the number of events among the selected

trials.

To assess the comparability of the included trials,

a heterogeneity analysis was performed. Since inconsistency is a

source of heterogeneity in network meta-analyses, a generalized

Cochran's Q statistic (Qtotal) and I2

statistic were adopted for assessment of homogeneity and

consistency assumptions. Statistical heterogeneity was considered

significant when P<0.10 for the Q-test or I2<50%.

The network meta-analysis used fixed-effects models with

I2 values of 0% for overall mortality, mortality due to

rebleeding, mortality due to liver failure and bleeding from a

gastroesophageal ulcer, and I2=29.4% for treatment

failure.

All treatments were ranked according to P-score,

which is on a scale from 0 (worst) to 1 (best). P-scores are based

solely on the point estimates and standard errors of the most

frequent network meta-analysis estimates under normality

assumption, and can easily be calculated as means of one-sided

P-values. They measure the extent of certainty that a treatment is

better than another treatment, averaged over all competing

treatments (17). Sensitivity

analysis was performed by removal of trials with a mean follow-up

of <6 months. The network meta-analyses were performed using R

3.3.1 along with the ‘netmeta’ package by Schwarzer et al

(18).

Results

Search results

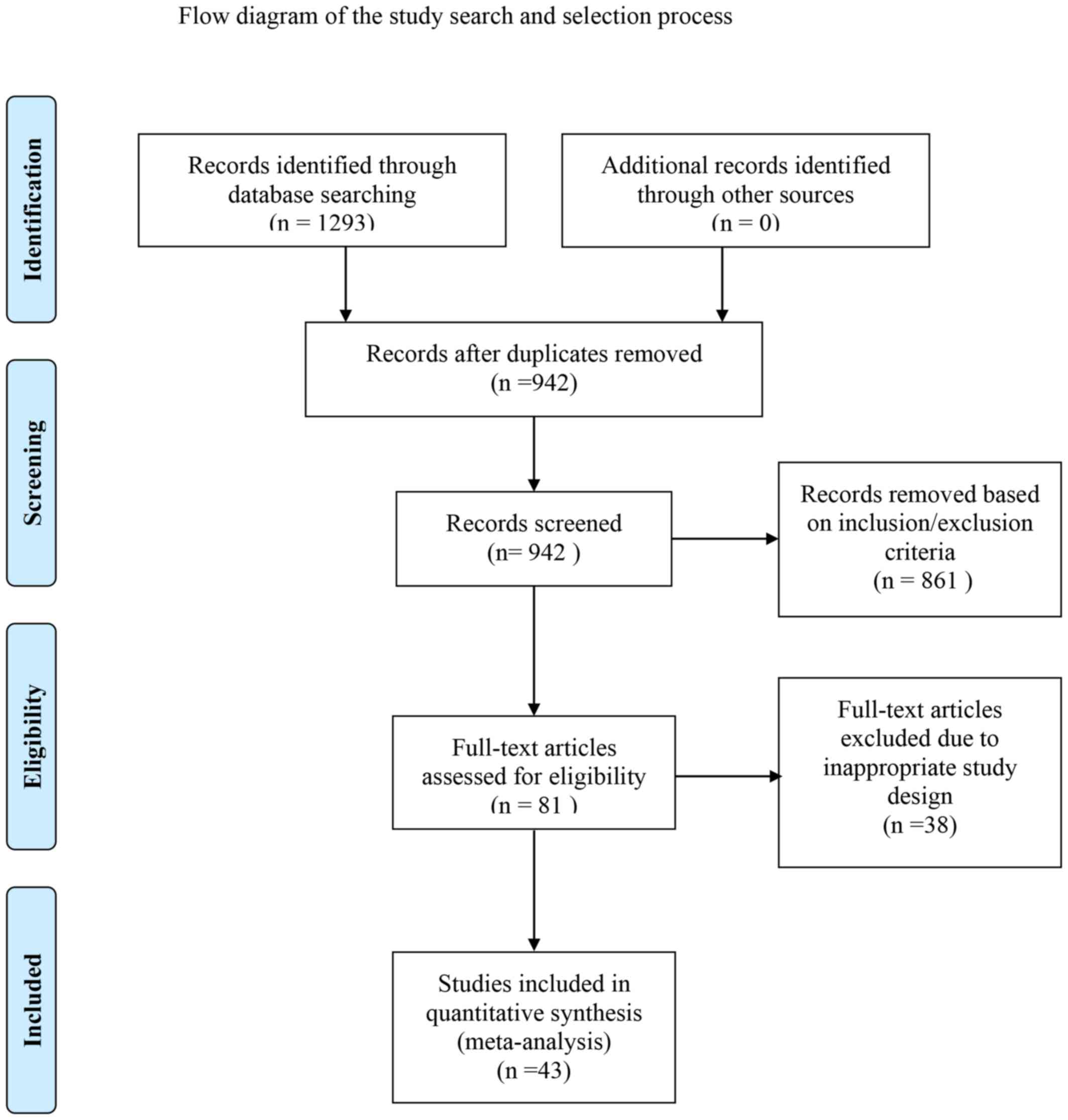

Electronic and manual searches identified 1,293

records in total. Following screening of titles and abstracts, 861

references were excluded and the remainder was subjected to

full-text screening. Among the excluded studies were duplicates,

non-RCTs, trials investigating other treatments, or those covering

different topics or focusing on primary prevention of variceal

bleeding, due to inadequate data for the present study or

randomizing patients without cirrhosis. A previous trial

investigating the effects of carvedilol plus EVL was excluded, as

it assessed hemodynamic responses but not mortality (19). The screening process followed the

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

(PRISMA) guidelines and is depicted in a flow chart in Fig. 1.

Characteristics of the studies

included

A total of 43 trials (20-62)

with a total sample size of 3,787 patients with cirrhosis were

included for quantitative network meta-analysis. In total, 5

references were published or available as abstracts (22,35,39,42,43) and

the remainder were available in full text. A previous trial had 4

treatment arms (44), among which 3

(EVL alone, EVL plus propranolol plus ISMN and propranolol plus

ISMN) were included from the present study. Another had 3 arms

(22), of which 2 (EVL alone and

propranolol plus ISMN) were included, and the arm of carvedilol

treatment alone was excluded. All of the other trials were designed

with 2 treatment arms. The proportion of patients with cirrhosis

was 100% in all of the trials. The baseline characteristics of the

trials are presented in Table I.

Patient inclusion and exclusion criteria varied slightly across

trials, but patients were generally eligible if they were adults

with cirrhosis with at least one episode of endoscopic-proven

oesophageal or gastric variceal bleeding. Exclusion criteria

included hepatocarcinoma, non-bleeding varices, existing

multi-organ failure and lack of cirrhosis. A total of 30 of the 43

studies had a mean follow-up time of >2 years, as presented in

Table I. In total, five trials were

excluded from the sensitivity analysis due to follow-up times that

were unknown or <6 months (43,47,55,60,61).

TIPS alone was used as the comparative treatment in the forest

plots, since it is a recommended surgery for secondary prophylaxis

according to the newest UK guidelines (5).

| Table ICharacteristic of randomized

controlled trials included in the network meta-analysis. |

Table I

Characteristic of randomized

controlled trials included in the network meta-analysis.

| First author

(year) | Treatment

groups | Patients (n) | Mean age

(years) | Females (%) | Varices, grade or

size, n | Child-Pugh class

(A/B/C) | Mean Pugh

score | Mean follow-up

(days) | No. of

subjectsa | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Sauerbruch

(2015) | TIPS | 90 | 55 | 31 | NA | 45% A | 6.9 | 906 | 27/NA/11/NA/NA | (20) |

| |

Propranolol+ISMN | 95 | 55 | 34 | NA | 49% A | 7 | 906 | 25/NA/9/NA/NA | |

| Luo (2015) | TIPS | 37 | 51 | 49 | NA | 0/25/12 | 8.76 | 690 | 12/1/9/NA/0 | (21) |

| |

EVL+Propranolol | 36 | 50 | 33 | NA | 0/24/12 | 8.89 | 637 | 17/3/10/NA/2 | |

| Kumar (2015) | EVL | 56 | 44 | NA | NA | NA | 8.6 | 500 | 9/NA/NA/NA/NA | (22) |

| |

Propranolol+ISMN | 39 | 44 | NA | NA | NA | 8.6 | 500 | 8/NA/NA/NA/NA | |

| Kong (2015) | EVL | 20 | 54 | 30 | F2:10; F3:10 | 9/11/0 | NA | 488 | 0/NA/NA/NA/NA | (23) |

| | ES | 18 | 53 | 50 | F2:9; F3:11 | 8/10/0 | NA | 488 | 0/NA/NA/NA/NA | |

| Kumar (2009) |

EVL+Propranolol+ISMN | 88 | 42 | 15 | MG 3.1:88 | 35/31/10 | 3.2 | 458 | 2/NA/NA/NA/NA | (24) |

| | EVL | 89 | 41 | 12 | MG 3.2:89 | 26/34/15 | 3.2 | 458 | 3/NA/NA/NA/NA | |

| Sauer (2002) | TIPS | 43 | 54 | 37 | MG 2.4:43 | 15/16/12 | 7.9 | 1,498 | 8/1/4/1/NA | (25) |

| | EVL | 42 | 55 | 45 | MG 2.6:42 | 10/19/13 | 8.2 | 1,315 | 7/2/2/5/NA | |

| Gülberg (2002) | TIPS | 28 | 57 | 29 | NA | 11/15/2 | NA | 730 | 4/1/2/NA/NA | (26) |

| | EVL | 26 | 56 | 27 | NA | 10/12/4 | NA | 730 | 4/2/1/NA/NA | |

| Escorsell

(2002) |

Propranolol+ISMN | 46 | 56 | 20 | NA | 0/28/16 | NA | 470 | 11/4/2/NA/NA | (27) |

| | TIPS | 47 | 57 | 30 | NA | 0/30/17 | NA | 436 | 13/3/5/NA/NA | |

| Villanueva

(2001) | EVL | 72 | 58 | 35 | G1: 1; G2:49;

G3:22 | 11/43/18 | 8.4 | 666 | 30/10/12/23/7 | (28) |

| | Nadolol+ISMN | 72 | 60 | 40 | G1: 2; G2:41;

G3:29 | 19/39/14 | 7.9 | 605 | 23/4/10/12/0 | |

|

Pomier-Layrargues | EVL | 39 | 54 | 31 | NA | NA | 9.8 | 581 | 16/3/9/NA/NA | (29) |

| (2001) | TIPS | 41 | 53 | 29 | NA | NA | 9.6 | 678 | 17/0/10/NA/NA | |

| Narahara

(2001) | TIPS | 38 | 51 | 16 | NA | NA | 6.8 | 1,116 | 11/NA/7/NA/0 | (30) |

| | ES | 40 | 55 | 25 | NA | NA | 7.4 | 1,047 | 7/NA/NA/NA/NA | |

| Hou (2001) | EVL | 47 | 55 | 34 | NA | 14/17/16 | 8.2 | 351 | 6/NA/4/NA/NA | (31) |

| | EVL+ES | 47 | 59 | 23 | NA | 11/23/13 | 8 | 336 | 7/NA/5/NA/NA | |

| Meddi (1999) | TIPS | 18 | 61 | 28 | NA | NA | 7.6 | 545 | 4/NA/NA/NA/NA | (32) |

| | ES | 20 | 58 | 30 | NA | NA | 7.6 | 545 | 2/NA/NA/NA/NA | |

| Villarreal

(1999) | TIPS | 22 | 58 | 32 | NA | 5/10/7 | 8.6 | 760 | 3/0/1/0/NA | (33) |

| | ES | 24 | 55 | 8 | NA | 3/14/7 | 8.8 | 503 | 8/6/1/7/NA | |

| Sauer (1997) | TIPS | 42 | 54 | 64 | NA | 15/18/9 | 7 | 530 | 12/0/7/NA/0 | (34) |

| | ES | 41 | 60 | 51 | NA | 12/18/11 | 7 | 584 | 11/5/3/NA/3 | |

| Sanyal (1997) | TIPS | 41 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 1,000 | 12/NA/2/NA/NA | (35) |

| | ES | 39 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 1,000 | 7/NA/2/NA/NA | |

| Villanueva

(1996) | Nadolol+ISMN | 43 | 58 | 33 | G1:3; G2:30;

G3:10 | 9/27/7 | NA | 545 | 4/0/2/3/1 | (36) |

| | ES | 43 | 60 | 33 | G1:2; G2:31;

G3:10 | 11/22/10 | NA | 545 | 9/2/5/16/7 | |

| Li (2010) | ES | 36 | 54 | 58 | G1:0; G2:0;

G3:36 | NA | 7.36 | 181.5 | 7/NA/NA/4/7 | (37) |

| | EVL | 27 | 51 | 26 | G1: 0; G2:0;

G3:27 | NA | 6.86 | 181.5 | 1/NA/NA/0/0 | |

| Holster (2016) |

EVL+Propranolol | 35 | 54 | 49 | NA | 13/18/4 | 7.3 | 708 | 9/NA/0/12/2 | (38) |

| | TIPS | 37 | 56 | 34 | NA | 13/19/5 | 7.5 | 708 | 12/NA/3/14/1 | |

| van Buuren

(2000) | TIPS | 19 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 632 | NA/NA/NA/1/NA | (39) |

| | EVL | 18 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 632 | NA/NA/NA/0/NA | |

| Cabrera (1996) | ES | 32 | 56 | 28 | NA | 14/16/2 | 7.22 | 454 | 5/3/NA/10/5 | (40) |

| | TIPS | 31 | 56 | 35 | NA | 14/13/4 | 7.1 | 454 | 6/0/NA/0/0 | |

| Dobrucali

(1998) | EVL | 50 | 55 | 22 | G2:1; G3:5;

G4:44 | 18/23/9 | NA | 908 | NA/NA/4/NA/NA | (41) |

| | ES | 28 | 42 | 43 | G2:2; G3:3;

G4:23 | 7/13/8 | NA | 908 | NA/NA/0/NA/NA | |

| Holster (2013) | TIPS | 35 | 54 | 44 | NA | NA | 7.4 | 545 | 8/NA/NA/NA/NA | (42) |

| | EVL | 36 | 54 | 44 | NA | NA | 7.4 | 545 | 7/NA/NA/NA/NA | |

| Merli (1994) | TIPS | 21 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 2/NA/NA/NA/NA | (43) |

| | ES | 17 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 1/NA/NA/NA/NA | |

| Ahmad (2009) |

Propranolol+ISMN | 35 | 52 | 40 | G1+G2:12;

G3:23 | 2/19/14 | 9.11 | 182 | 6/4/4/9/0 | (44) |

| | EVL | 39 | 53 | 36 | G1+G2:15;

G3:24 | 7/23/9 | 8.28 | 182 | 8/2/3/12/3 | |

| |

EVL+propranolol+ISMN | 37 | 50 | 19 | G1+G2:15;

G3:22 | 4/27/6 | 8.32 | 182 | 7/2/3/8/2 | |

| Argonz (2000) | EVL | 41 | 53 | 22 | G2:27; G3:14 | 14/23/4 | NA | 337 | 16/9/1//1 | (45) |

| | EVL+ES | 39 | 53 | 23 | G2:22; G3:17 | 11/26/2 | NA | 386 | 12/4/3//2 | |

| Avgerinos

(1997) | EVL | 37 | 55 | 16 | S:1; M:19;

L:17 | 23/11/3 | 7.7 | 472 | 8/0/NA/5/2 | (46) |

| | ES | 40 | 56 | 20 | S:3; M:19;

L:18 | 27/10/3 | 8 | 454 | 8/2/NA/4/4 | |

| Avgerinos

(2004) | ES | 25 | 52 | 24 | G1:3; G2:13;

G3:9 | 6/8/11 | 9.4 | 42 | 7/4/NA/13/NA | (47) |

| | EVL | 25 | 56 | 20 | G1:3; G2:12;

G3:10 | 7/6/12 | 9.2 | 42 | 5/2/NA/6/NA | |

| Avgerinos

(1993) | ES | 40 | 59 | 20 | S:3; M:19;

L:18 | 30/8/2 | 7.3 | 1,004 | 9/2/3/NA/NA | (48) |

| | ES+Propranolol | 45 | 58 | 36 | S:4; M:19;

L:22 | 33/8/4 | 7.6 | 1,035 | 8/3/3/NA/NA | |

| Baroncini

(1997) | ES | 54 | 61 | 31 | F3:36; F2:18 | 18/22/14 | 8 | 534 | 12/3/NA/NA/NA | (49) |

| | EVL | 57 | 63 | 33 | F3:42; F2:15 | 17/24/16 | 7.7 | 496 | 12/1/NA/NA/NA | |

| Chen (2016) | EVL | 48 | 56 | 33 | G1:18; G2:26;

G3:4 | 19/29/0 | NA | 182 | 1/1/NA/0/NA | (16) |

| | EVL+ES | 48 | 54 | 35 | G1:19; G2:23;

G3:6 | 20/28/0 | NA | 182 | 3/2/NA/0/NA | |

| García-Pagán

(2009) | Nadolol+ISMN | 78 | 56 | 32 | L:73 | 18/42/18 | 8.1 | 454 | 15/8/1/22/0 | (50) |

| |

EVL+Nadolol+ISMN | 80 | 57 | 19 | L:73 | 16/46/18 | 8.2 | 454 | 16/5/4/17/4 | |

| Hou (1995) | ES | 67 | 61 | 21 | F3:49;

F2+F1:18 | 15/29/23 | 8.2 | 293 | 11/4/6/NA | (51) |

| | EVL | 67 | 60 | 19 | F3:55;

F2+F1:12 | 17/21/29 | 8.8 | 287 | 14/0/13/NA/NA | |

| Hou (2000) | ES | 70 | 60 | 19 | F3:51;

F2+F1:19 | 17/34/19 | 8 | 1,918 | 11/4/NA/NA/2 | (52) |

| | EVL | 71 | 60 | 21 | F3:57;

F2+F1:14 | 20/26/25 | 8.4 | 1,818 | 9/1/NA/NA/3 | |

| Lo (1995) | ES | 59 | 54 | 17 | NA | 7/24/28 | 8.9 | 290 | 19/9/6/NA/NA | (53) |

| | EVL | 61 | 57 | 21 | NA | 9/22/30 | 9.5 | 310 | 10/4/6/NA/NA | |

| Lo (1997) | EVL | 37 | 53 | 14 | F3:27; F2:10 | 2/13/22 | NA | 30 | 7/3/3/NA/NA | (54) |

| | ES | 34 | 55 | 12 | F3:26; F2:8 | 3/11/20 | NA | 30 | 12/6/3/NA/NA | |

| de la Peña

(2005) | EVL+Nadolol | 43 | 60 | 23 | G1:10; G2:26;

G3:7 | 6/20/11 | NA | 529 | 5/0/2/2/1 | (55) |

| | EVL | 37 | 60 | 27 | G1:7; G2:17;

G3:13 | 6/25/12 | NA | 454 | 4/1/2/7/3 | |

| Peña (1999) | ES | 46 | 59 | 35 | G1:10; G2:31;

G3:5 | 12/22/13 | NA | 545 | 10/NA/3/11/2 | (56) |

| | EVL | 42 | 59 | 19 | G1:6; G2:25;

G3:11 | 10/22/10 | NA | 484 | 8/NA/2/5/3 | |

| Romero (2006) | Nadolol+ISMN | 57 | 51 | 35 | NA | 40/44/16 | 7 | 348 | 11/9/NA/18/0 | (57) |

| | EVL | 52 | 53 | 33 | NA | 32/58/10 | 7 | 363 | 10/6/NA/12/3 | |

| Stiegmann

(1992) | ES | 65 | 53 | 22 | G1:9; G2:31;

G3:25 | 20/32/11 | 9.9 | 303 | 29/8/NA/NA/NA | (58) |

| | EVL | 64 | 51 | 17 | G1:8; G2:35;

G3:21 | 22/30/12 | 9.4 | 303 | 18/3/NA/NA/NA | |

| Umehara (1999) | EVL+ES | 25 | 58 | NA | F3:9; F2:16 | 10/11/4 | NA | 611 | 3/0/NA/NA/NA | (59) |

| | EVL | 26 | 59 | NA | F3:8; F2:18 | 7/13/6 | NA | 629 | 4/0/NA/NA/NA | |

| Viazis (2002) | EVL | 36 | 64 | 42 | S:9; M:17;

L:10 | 4/18/14 | NA | 50 | NA/NA/NA/NA/NA | (60) |

| | ES | 37 | 62 | 46 | S:10; M:15;

L:12 | 6/16/15 | NA | 59 | NA/NA/NA/NA/NA | |

| Vinel (1992) | ES | 35 | 57 | 43 | F3:30; F2:5 | NA | 9.1 | 92 | 5/3/NA/NA/NA | (61) |

| | ES+Propranolol | 39 | 55 | 23 | F3:20; F2:19 | NA | 9.2 | 102 | 5/4/NA/NA/NA | |

Bias assessment

Risk of bias assessment for the RCTs included was

performed following the PRISMA recommendations; the results are

presented in Table SI. A total of

26 (61%) trials (20-22,24-30,34,36,38,44,47,16,50,56,61)

adopted concealed randomization via sealed opaque envelopes, by

using central randomization or through an independent person not

involved in the treatment of the patients. Only one trial declared

early cessation (54). A total of

two trials were open labelled (20,24) and

two trials reported using outcome assessors under blinded

conditions (27,16). Blinding of the remaining trials was

not specified.

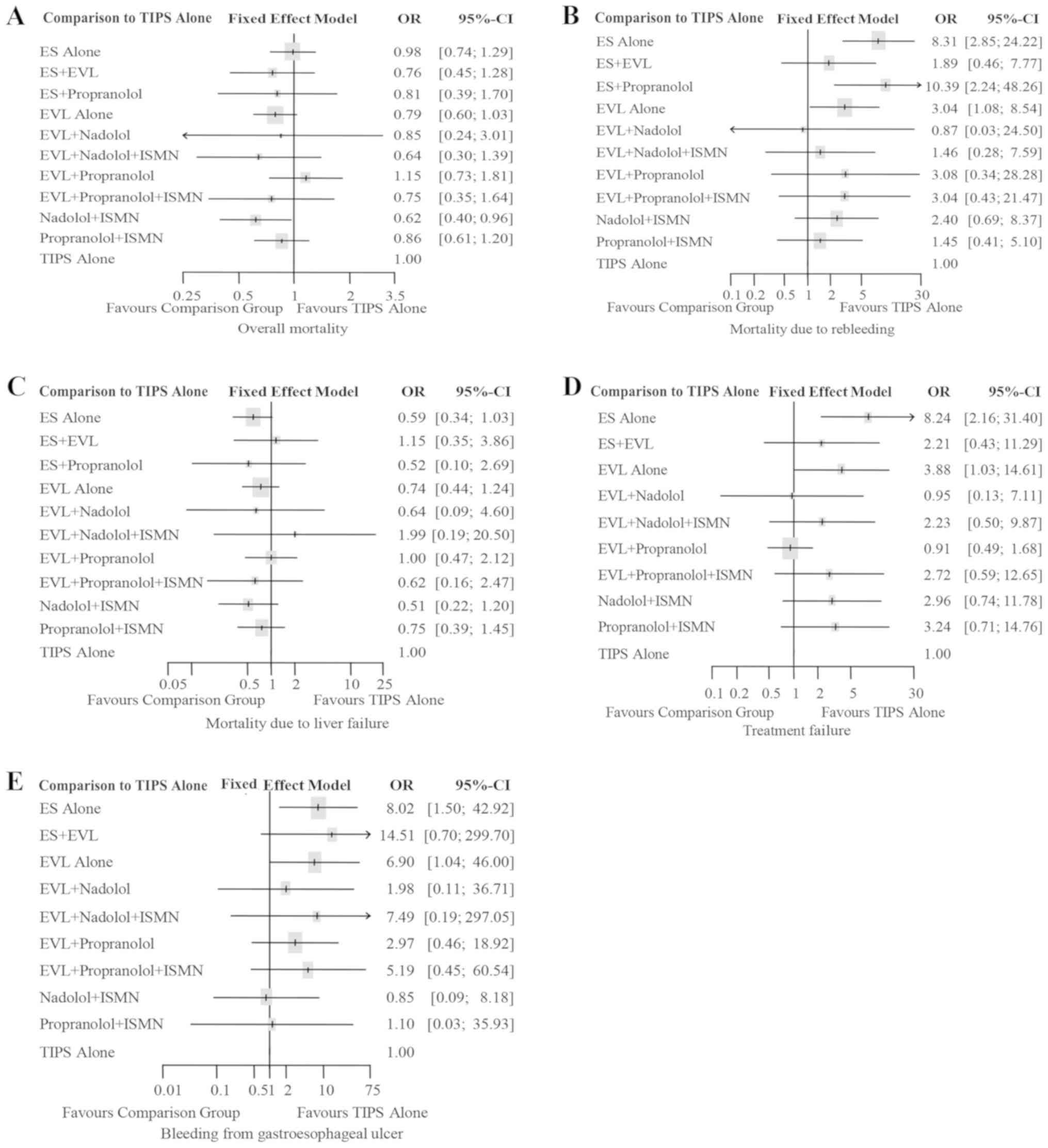

Overall mortality

In total, 40 trials with a total of 3,599 patients

reported overall mortality, involving all 11 treatment regimens.

Fig. S1A illustrates the evidence

networks connecting the regimens. Nadolol plus ISMN also had the

highest P-score (P-score=0.8162, Table

II) with the largest probability to reduce mortality when

compared with the other treatments. No statistical heterogeneity

was observed (Heterogeneity I2=0%; Cochran's test

P=0.9618, Table III) in this

outcome measure. The fixed-effects model analysis suggested that

nadolol plus ISMN was significantly more effective than TIPS alone

(OR=0.62, 95% CI: 0.40-0.96, Table

III), as presented in Fig. 2A.

Pairwise comparisons indicated that nadolol plus ISMN and EVL alone

were significantly more effective than ES alone in reducing overall

mortality (OR=0.63, 95% CI: 0.42-0.94; OR=0.80, 95% CI: 0.65-0.99,

respectively, Table III), while

differences among other treatments were not statistically

significant.

| Table IIRanking for efficacy of 11 potential

treatment options. |

Table II

Ranking for efficacy of 11 potential

treatment options.

| | Overall

mortality | Mortality due to

rebleeding | Mortality due to

liver failure | Treatment

failure | Bleeding from

gastroesophageal ulcer |

|---|

| Rank | P-score | Treatment | P-score | Treatment | P-score | Treatment | P-score | Treatment | P-score | Treatment |

|---|

| 1 | 0.8162 | Nadolol+ISMN | 0.8276 | TIPS alone | 0.7536 | Nadolol+ISMN | 0.8071 |

EVL+propranolol | 0.7536 | Nadolol+ISMN |

| 2 | 0.7135 |

EVL+nadolol+ISMN | 0.7265 | EVL+nadolol | 0.6964 | ES alone | 0.7938 | TIPS alone | 0.6964 | ES alone |

| 3 | 0.5983 | ES+EVL | 0.6931 |

EVL+nadolol+ISMN | 0.6651 | ES+propranolol | 0.7932 | EVL+nadolol | 0.6651 | ES+propranolol |

| 4 | 0.5887 | EVL alone | 0.6833 |

Propranolol+ISMN | 0.6044 |

EVL+propranolol+ISMN | 0.5630 |

EVL+nadolol+ISMN | 0.6044 |

EVL+propranolol+ISMN |

| 5 | 0.5843 |

EVL+propranolol+ISMN | 0.6047 | ES+EVL | 0.5755 | EVL+nadolol | 0.5189 | ES+EVL | 0.5755 | EVL+nadolol |

| 6 | 0.5218 | ES+propranolol | 0.5041 | Nadolol+ISMN | 0.5230 | EVL alone | 0.4520 |

EVL+propranolol+ISMN | 0.5230 | EVL alone |

| 7 | 0.4847 | EVL+nadolol | 0.4377 |

EVL+propranolol | 0.5226 |

Propranolol+ISMN | 0.4328 | Nadolol+ISMN | 0.5226 |

Propranolol+ISMN |

| 8 | 0.4744 |

Propranolol+ISMN | 0.4331 |

EVL+propranolol+ISMN | 0.3439 |

EVL+propranolol | 0.3680 |

Propranolol+ISMN | 0.3439 |

EVL+propranolol |

| 9 | 0.2811 | ES alone | 0.3934 | EVL alone | 0.3022 | TIPS alone | 0.2513 | EVL alone | 0.3022 | TIPS alone |

| 10 | 0.2624 | TIPS alone | 0.1125 | ES alone | 0.2966 | ES+EVL | 0.0199 | ES alone | 0.2966 | ES+EVL |

| 11 | 0.1747 |

EVL+propranolol | 0.0842 | ES+propranolol | 0.2167 |

EVL+nadolol+ISMN | | | 0.2167 |

EVL+nadolol+ISMN |

| Table IIINetwork meta-analysis results of

pairwise comparisons (Odds ratios with 95% CI). |

Table III

Network meta-analysis results of

pairwise comparisons (Odds ratios with 95% CI).

| A, Overall

mortality (Heterogeneity I2=0%, P=0.9618), fixed-effects

model |

|---|

| Group | ES alone | ES+EVL | ES+propranolol | EVL alone | EVL+nadolol |

EVL+nadolol+ISMN |

EVL+propranolol |

EVL+Propranolol+ISMN | Nadolol+ISMN |

Propranolol+ISMN | TIPS alone |

|---|

| ES alone | - | 1.29

[0.79,2.10] | 1.21

[0.61,2.40] | 1.25

[1.01,1.54] | 1.16

[0.33,4.07] | 1.53

[0.72,3.23] | 0.85

[0.50,1.45] | 1.30

[0.60,2.83] | 1.59

[1.06,2.38] | 1.14

[0.77,1.71] | 0.98

[0.74,1.29] |

| ES+EVL | 0.78

[0.48,1.27] | - | 0.94

[0.40,2.18] | 0.97

[0.62,1.52] | 0.90

[0.24,3.36] | 1.18

[0.50,2.78] | 0.66

[0.33,1.32] | 1.01

[0.42,2.43] | 1.23

[0.69,2.19] | 0.89

[0.49,1.60] | 0.76

[0.45,1.28] |

| ES+propranolol | 0.83

[0.42,1.64] | 1.06

[0.46,2.47] | - | 1.03

[0.50,2.11] | 0.96

[0.23,4.01] | 1.26

[0.46,3.48] | 0.70

[0.30,1.68] | 1.08

[0.38,3.03] | 1.31

[0.59,2.90] | 0.95

[0.43,2.09] | 0.81

[0.39,1.70] |

| EVL alone | 0.80

[0.65,0.99] | 1.03

[0.66,1.63] | 0.97

[0.47,1.99] | - | 0.93

[0.27,3.21] | 1.22

[0.59,2.53] | 0.68

[0.40,1.16] | 1.05

[0.49,2.22] | 1.27

[0.89,1.82] | 0.92

[0.63,1.35] | 0.79

[0.60,1.03] |

| EVL+nadolol | 0.86

[0.25,3.03] | 1.11

[0.30,4.16] | 1.04

[0.25,4.37] | 1.08

[0.31,3.71] | - | 1.32

[0.31,5.54] | 0.74

[0.19,2.83] | 1.12

[0.26,4.79] | 1.37

[0.38,4.98] | 0.99

[0.27,3.61] | 0.85

[0.24,3.01] |

|

EVL+nadolol+ISMN | 0.66

[0.31,1.39] | 0.84

[0.36,1.99] | 0.79

[0.29,2.19] | 0.82

[0.40,1.69] | 0.76

[0.18,3.19] | - | 0.56

[0.23,1.37] | 0.85

[0.30,2.43] | 1.04

[0.55,1.96] | 0.75

[0.33,1.70] | 0.64

[0.30,1.39] |

|

EVL+propranolol | 1.17

[0.69,2.00] | 1.51

[0.76,3.02] | 1.42

[0.60,3.38] | 1.46

[0.86,2.48] | 1.36

[0.35,5.23] | 1.79

[0.73,4.39] | - | 1.53

[0.62,3.76] | 1.86

[0.99,3.52] | 1.34

[0.76,2.36] | 1.15

[0.73,1.81] |

|

EVL+propranolol+ISMN | 0.77

[0.35,1.67] | 0.99

[0.41,2.38] | 0.93

[0.33,2.61] | 0.96

[0.45,2.03] | 0.89

[0.21,3.79] | 1.17

[0.41,3.33] | 0.65

[0.27,1.61] | - | 1.22

[0.53,2.80] | 0.88

[0.40,1.92] | 0.75

[0.35,1.64] |

| Nadolol+ISMN | 0.63

[0.42,0.94] | 0.81

[0.46,1.44] | 0.76

[0.34,1.69] | 0.79

[0.55,1.12] | 0.73

[0.20,2.65] | 0.96

[0.51,1.81] | 0.54

[0.28,1.01] | 0.82

[0.36,1.89] | - | 0.72

[0.43,1.21] | 0.62

[0.40,0.96] |

|

Propranolol+ISMN | [0.59,1.31]

0.87 | 1.13

[0.62,2.03] | 1.06

[0.48,2.34] | 1.09

[0.74,1.60] | 1.01

[0.28,3.71] | 1.33

[0.59,3.03] | 0.74

[0.42,1.31] | 1.14

[0.52,2.49] | 1.39

[0.82,2.34] | - | 0.86

[0.61,1.20] |

| TIPS alone | 1.02

[0.77,1.35] | 1.31

[0.78,2.22] | 1.23

[0.59,2.58] | 1.27

[0.97,1.67] | 1.18

[0.33,4.20] | 1.56

[0.72,3.37] | 0.87

[0.55,1.37] | 1.33

[0.61,2.89] | 1.62

[1.04,2.52] | 1.17

[0.83,1.63] | - |

| B, Mortaility due

to rebleeding (Heterogeneity I2=0%, P=0.9963),

fixed-effects model |

| Group | ES alone | ES+EVL | ES+propranolol | EVL alone | EVL+nadolol |

EVL+nadolol+ISMN |

EVL+propranolol |

EVL+Propranolol+ISMN | Nadolol+ISMN |

Propranolol+ISMN | TIPS alone |

| ES alone | - | 4.39 | 0.80 | 2.74 | 9.53 | 5.68 | 2.70 | 2.74 | 3.46 | 5.75 | 8.31 |

| ES alone | - | 4.39

[1.45,13.26] | 0.80

[0.27,2.41] | 2.74

[1.59,4.73] | 9.53

[0.38,237.86] | 5.68

[1.42,22.68] | 2.70

[0.23,31.58] | 2.74

[0.42,17.81] | 3.46

[1.44,8.31] | 5.75

[1.30,25.47] | 8.31

[2.85,24.22] |

| ES+EVL | 0.23

[0.08,0.69] | - | 0.18

[0.04,0.87] | 0.62

[0.24,1.63] | 2.17

[0.08,59.65] | 1.29

[0.26,6.44] | 0.61

[0.04,8.50] | 0.62

[0.08,4.83] | 0.79

[0.24,2.60] | 1.31

[0.23,7.41] | 1.89

[0.46,7.77] |

| ES+propranolol | 1.25

[0.42,3.76] | 5.49

[1.15,26.14] | - | 3.42

[1.00,11.71] | 11.91

[0.40,357.18] | 7.10

[1.21,41.67] | 3.37

[0.23,49.96] | 3.42

[0.39,30.05] | 4.33

[1.06,17.67] | 7.19

[1.13,45.80] | 10.39

[2.24,48.26] |

| EVL alone | 0.37

[0.21,0.63] | 1.60

[0.61,4.19] | 0.29

[0.09,1.00] | - | 3.48

[0.15,82.91] | 2.07

[0.57,7.50] | 0.98

[0.09,11.36] | 1.00

[0.16,6.09] | 1.26

[0.62,2.57] | 2.10

[0.50,8.88] | 3.04

[1.08,8.54] |

| EVL+nadolol | 0.10

[0.00,2.62] | 0.46

[0.02,12.66] | 0.08

[0.00,2.52] | 0.29

[0.01,6.85] | - | 0.60

[0.02,18.24] | 0.28

[0.01,15.52] | 0.29

[0.01,11.04] | 0.36

[0.01,9.36] | 0.60

[0.02,19.66] | 0.87

[0.03,24.50] |

|

EVL+nadolol+ISMN | 0.18

[0.04,0.70] | 0.77

[0.16,3.85] | 0.14

[0.02,0.83] | 0.48

[0.13,1.74] | 1.68

[0.05,51.36] | - | 0.47

[0.03,7.51] | 0.48

[0.05,4.42] | 0.61

[0.21,1.78] | 1.01

[0.15,6.97] | 1.46

[0.28,7.59] |

|

EVL+propranolol | 0.37

[0.03,4.34] | 1.63

[0.12,22.53] | 0.30

[0.02,4.40] | 1.02

[0.09,11.71] | 3.53

[0.06,193.72] | 2.11

[0.13,33.29] | - | 1.01

[0.05,19.49] | 1.28

[0.10,16.33] | 2.13

[0.17,27.32] | 3.08

[0.34,28.28] |

|

EVL+propranolol+ISMN | 0.37

[0.06,2.38] | 1.60

[0.21,12.42] | 0.29

[0.03,2.57] | 1.00

[0.16,6.10] | 3.48

[0.09,133.93] | 2.08

[0.23,19.05] | 0.99

[0.05,18.94] | - | 1.27

[0.18,8.80] | 2.10

[0.29,15.46] | 3.04

[0.43,21.47] |

| Nadolol+ISMN | 0.29

[0.12,0.69] | 1.27

[0.38,4.19] | 0.23

0.06,0.94] | 0.79

[0.39,1.61] | 2.75

[0.11,70.92] | 1.64

[0.56,4.80] | 0.78

[0.06,9.91] | 0.79

[0.11,5.50] | - | 1.66

[0.33,8.26] | 2.40

[0.69,8.37] |

|

Propranolol+ISMN | 0.17

[0.04,0.77] | 0.76

[0.13,4.31] | 0.14

[0.02,0.89] | 0.48

[0.11,2.01] | 1.66

[0.05,53.91] | 0.99

[0.14,6.79] | 0.47

[0.04,6.00] | 0.48

[0.06,3.49] | 0.60

[0.12,2.99] | - | 1.45

[0.41,5.10] |

| TIPS alone | 0.12

[0.04,0.35] | 0.53

[0.13,2.17] | 0.10

[0.02,0.45] | 0.33

[0.12,0.93] | 1.15

[0.04,32.17] | 0.68

[0.13,3.54] | 0.32

[0.04,2.97] | 0.33

[0.05,2.32] | 0.42

[0.12,1.45] | 0.69

[0.20,2.44] | - |

| C, Mortality due to

liver failure (Heterogeneity I2=0%, P=0.8985),

fixed-effects model |

| Group | ES alone | ES+EVL | ES+propranolol | EVL alone | EVL+nadolol |

EVL+nadolol+ISMN |

EVL+propranolol |

EVL+Propranolol+ISMN | Nadolol+ISMN |

Propranolol+ISMN | TIPS alone |

| ES alone | - | 0.51

[0.15,1.68] | 1.13

[0.24,5.26] | 0.80

[0.49,1.29] | 0.92

[0.13,6.63] | 0.29

[0.03,2.97] | 0.59

[0.23,1.50] | 0.94

0.23,3.90] | 1.15

[0.52,2.55] | 0.79

[0.34,1.79] | 0.59

[0.34,1.03] |

| ES+EVL | 1.96

[0.60,6.46] | - | 2.21

[0.31,15.51] | 1.56

[0.53,4.65] | 1.82

[0.20,16.37] | 0.58

[0.05,7.24] | 1.15

[0.28,4.78] | 1.85

[0.32,10.65] | 2.26

[0.62,8.24] | 1.54

[0.41,5.87] | 1.15

[0.35,3.86] |

| ES+propranolol | 0.89

[0.19,4.16] | 0.45

[0.06,3.18] | - | 0.71

[0.14,3.56] | 0.82

[0.07,10.03] | 0.26

[0.02,4.21] | 0.52

[0.09,3.17] | 0.84

[0.10,6.83] | 1.02

[0.18,5.79] | 0.70

[0.12,4.01] | 0.52

[0.10,2.69] |

| EVL alone | 1.26

[0.78,2.03] | 0.64

[0.22,1.90] | 1.41

[0.28,7.11] | - | 1.16

[0.17,7.85] | 0.37

[0.04,3.62] | 0.74

[0.30,1.84] | 1.19

[0.30,4.66] | 1.44

[0.72,2.91] | 0.99

[0.46,2.14] | 0.74

0.44,1.24] |

| EVL+nadolol | 1.08

[0.15,7.75] | 0.55

[0.06,4.97] | 1.22

[0.10,14.84] | 0.86

[0.13,5.81] | - | 0.32

[0.02,6.23] | 0.64

[0.08,5.27] | 1.02

[0.10,10.69] | 1.24

[0.16,9.50] | 0.85

[0.11,6.67] | 0.64

[0.09,4.60] |

|

EVL+nadolol+ISMN | 3.39

[0.34,34.20] | 1.73

[0.14,21.63] | 3.82

[0.24,61.42] | 2.70

[0.28,26.39] | 3.14

[0.16,61.42] | - | 1.99

[0.17,23.05] | 3.20

[0.23,45.57] | 3.90

[0.45,34.12] | 2.67

[0.24,29.42] | 1.99

[0.19,20.50] |

|

EVL+propranolol | 1.70

[0.67,4.33] | 0.87

[0.21,3.59] | 1.91

[0.32,11.62] | 1.35

[0.54,3.37] | 1.57

[0.19,13.06] | 0.50

[0.04,5.80] | - | 1.61

[0.33,7.70] | 1.96

[0.63,6.08] | 1.34

[0.49,3.64] | 1.00

[0.47,2.12] |

|

EVL+propranolol+ISMN | 1.06

[0.26,4.39] | 0.54

[0.09,3.11] | 1.19

[0.15,9.71] | 0.84

[0.21,3.32] | 0.98

[0.09,10.28] | 0.31

[0.02,4.45] | 0.62

[0.13,2.99] | - | 1.22

[0.26,5.64] | 0.83

[0.22,3.16] | 0.62

[0.16,2.47] |

| Nadolol+ISMN | 0.87

[0.39,1.93] | 0.44

[0.12,1.62] | 0.98

[0.17,5.55] | 0.69

[0.34,1.40] | 0.80

[0.11,6.16] | 0.26

[0.03,2.24] | 0.51

[0.16,1.59] | 0.82

[0.18,3.80] | - | 0.68

[0.24,1.91] | 0.51

[0.22,1.20] |

|

Propranolol+ISMN | 1.27

[0.56,2.90] | 0.65

[0.17,2.47] | 1.43

[0.25,8.23] | 1.01

[0.47,2.19] | 1.18

[0.15,9.24] | 0.38

[0.03,4.14] | 0.75

[0.27,2.04] | 1.20

[0.32,4.55] | 1.46

[0.52,4.09] | - | 0.75

[0.39,1.45] |

| TIPS alone | 1.70

[0.97,2.97] | 0.87

[0.26,2.90] | 1.91

[0.37,9.87] | 1.35

[0.81,2.28] | 1.57

[0.22,11.39] | 0.50

[0.05,5.15] | 1.00

[0.47,2.11] | 1.61

[0.41,6.36] | 1.95

[0.83,4.58] | 1.34

[0.69,2.60] | - |

| D, Treatment

failure (Heterogeneity I2=29.4%, P=0.1739),

fixed-effects model |

| Group | ES alone | ES+EVL | EVL alone | EVL+nadolol |

EVL+nadolol+ISMN |

EVL+propranolol |

EVL+Propranolol+ISMN | Nadolol+ISMN |

Propranolol+ISMN | TIPS alone |

| ES alone | - | 3.72

[1.30,10.67] | 2.13

[1.31,3.45] | 8.65

[1.77,42.15] | 3.69

[1.65,8.27] | 9.09

[2.08,39.68] | 3.02

[1.22,7.53] | 2.78

[1.54,5.02] | 2.54

[1.06,6.12] | 8.24

[2.16,31.40] |

| ES+EVL | 0.27

[0.09,0.77] | - | 0.57

[0.22,1.48] | 2.32

[0.39,13.82] | 0.99

[0.31,3.21] | 2.44

[0.43,13.94] | 0.81

[0.24,2.77] | 0.75

[0.27,2.11] | 0.68

[0.21,2.27] | 2.21

[0.43,11.29] |

| EVL alone | 0.47

[0.29,0.76] | 1.75

[0.68,4.53] | - | 4.07

[0.90,18.39] | 1.74

[0.87,3.46] | 4.28

[0.99,18.49] | 1.42

[0.66,3.08] | 1.31

[0.86,1.98] | 1.20

[0.57,2.49] | 3.88

[1.03,14.61] |

| EVL+nadolol | 0.12 | 0.43 | 0.25 | - | 0.43 | 1.05 | 0.35 | 0.32 | 0.29 | 0.95 |

| EVL+nadolol | 0.12

[0.02,0.56] | 0.43

[0.07,2.56] | 0.25

[0.05,1.11] | - | 0.43

[0.08,2.24] | 1.05

[0.13,8.61] | 0.35

[0.06,1.91] | 0.32

[0.07,1.54] | 0.29

[0.05,1.58] | 0.95

[0.13,7.11] |

|

EVL+nadolol+ISMN | 0.27

[0.12,0.61] | 1.01

[0.31,3.26] | 0.58

[0.29,1.15] | 2.34

[0.45,12.30] | - | 2.46

[0.49,12.31] | 0.82

[0.29,2.31] | 0.75

[0.43,1.31] | 0.69

[0.25,1.89] | 2.23

[0.50,9.87] |

|

EVL+propranolol | 0.11

[0.03,0.48] | 0.41

[0.07,2.34] | 0.23

[0.05,1.01] | 0.95

[0.12,7.78] | 0.41

[0.08,2.03] | - | 0.33

[0.06,1.74] | 0.31

[0.07,1.39] | 0.28

[0.05,1.44] | 0.91

[0.49,1.68] |

|

EVL+propranolol+ISMN | 0.33

[0.13,0.82] | 1.23

[0.36,4.19] | 0.70

[0.32,1.52] | 2.86

[0.52,15.57] | 1.22

[0.43,3.44] | 3.01

[0.57,15.74] | - | 0.92

[0.38,2.21] | 0.84

[0.37,1.93] | 2.72

[0.59,12.65] |

| Nadolol+ISMN | 0.36

[0.20,0.65] | 1.34

[0.47,3.77] | 0.76

[0.50,1.16] | 3.11

[0.65,14.86] | 1.33

[0.77,2.30] | 3.27

[0.72,14.83] | 1.09

[0.45,2.61] | - | 0.91

[0.39,2.12] | 2.96

[0.74,11.78] |

|

Propranolol+ISMN | 0.39

[0.16,0.95] | 1.46

[0.44,4.86] | 0.84

[0.40,1.74] | 3.40

[0.63,18.20] | 1.45

[0.53,3.98] | 3.57

[0.70,18.38] | 1.19

[0.52,2.73] | 1.09

[0.47,2.54] | - | 3.24

[0.71,14.76] |

| TIPS alone | 0.12

[0.03,0.46] | 0.45

[0.09,2.30] | 0.26

[0.07,0.97] | 1.05

[0.14,7.83] | 0.45

[0.10,1.98] | 1.10

[0.60,2.05] | 0.37

[0.08,1.71] | 0.34

[0.08,1.34] | 0.31

[0.07,1.41] | - |

| E, Bleeding from

gastroesophageal ulcer (Heterogeneity I2=0%, P=0.8354),

fixed-effects model |

| Group | ES alone | ES+EVL | EVL alone | EVL+nadolol |

EVL+nadolol+ISMN |

EVL+propranolol |

EVL+Propranolol+ISMN | Nadolol+ISMN |

Propranolol+ISMN | TIPS alone |

| ES alone | - | 0.55

[0.04,6.88] | 1.16

[0.48,2.82] | 4.05

[0.37,44.27] | 1.07

[0.04,28.38] | 2.71

[0.22,32.94] | 1.64

[0.24,11.51] | 9.41

[2.07,42.79] | 7.51

[0.35,160.14] | 8.02

[1.50,42.92] |

| ES+EVL | 1.81

[0.15,22.50] | - | 2.10

[0.20,22.27] | [0.29,187.21] | 1.94

[0.03,109.86] | 4.89

[0.14,170.35] | 2.97

[0.16,55.53] | 17.01

[1.03,280.81] | 13.58

[0.32,583.96] | 14.51

[0.70,299.70] |

| EVL alone | 0.86

[0.35,2.09] | 0.48

[0.04,5.04] | - | 3.49

[0.38,32.10] | 0.92

[0.03,24.40] | 2.33

[0.16,33.00] | 1.41

[0.25,7.99] | 8.09

[1.78,36.77] | 6.46

[0.35,120.78] | 6.90

[1.04,46.00] |

| EVL+nadolol | 0.25

[0.02,2.69] | 0.14

[0.01,3.48] | 0.29

[0.03,2.64] | - | 0.26

[0.01,13.83] | 0.67

[0.02,21.21] | 0.41

[0.02,6.78] | 2.32

[0.16,34.08] | 1.85

[0.05,73.08] | 1.98

[0.11,36.71] |

|

EVL+nadolol+ISMN | 0.93

[0.04,24.71] | 0.52

[0.01,29.25] | 1.09

[0.04,28.72] | 3.78

[0.07,197.91] | - | 2.52

[0.04,155.57] | 1.53

[0.04,62.41] | 8.78

[0.48,160.33] | 7.01

[0.09,567.49] | 7.49

[0.19,297.05] |

|

EVL+propranolol | 0.37

[0.03,4.50] | 0.20

[0.01,7.11] | 0.43

[0.03,6.09] | 1.50

[0.05,47.60] | 0.40

[0.01,24.40] | - | 0.61

[0.03,14.43] | 3.48

[0.19,64.62] | 2.78

[0.05,144.26] | 2.97

[0.46,18.92] |

|

EVL+propranolol+ISMN | 0.61

[0.09,4.26] | 0.34

[0.02,6.28] | 0.71

[0.13,4.00] | 2.47

[0.15,41.18] | 0.65

[0.02,26.51] | 1.65

[0.07,39.07] | - | 5.72

[0.57,57.07] | 4.57

[0.23,91.89] | 4.88

[0.37,63.66] |

| Nadolol+ISMN | 0.11

[0.02,0.48] | 0.06

[0.00,0.97] | 0.12

[0.03,0.56] | 0.43

[0.03,6.33] | 0.11

[0.01,2.08] | 0.29

[0.02,5.35] | 0.17

[0.02,1.74] | - | 0.80

[0.03,21.58] | 0.85

[0.09,8.18] |

|

Propranolol+ISMN | 0.13

[0.01,2.84] | 0.07

[0.00,3.17] | 0.15

[0.01,2.89] | 0.54

[0.01,21.28] | 0.14

[0.00,11.55] | 0.36

[0.01,18.72] | 0.22

[0.01,4.40] | 1.25

[0.05,33.83] | - | 1.07

[0.03,34.99] |

| TIPS alone | 0.12

[0.02,0.67] | 0.07

[0.00,1.42] | 0.14

[0.02,0.97] | 0.51

[0.03,9.37] | 0.13

[0.00,5.30] | 0.34

[0.05,2.15] | 0.20

[0.02,2.67] | 1.17

[0.12,11.23] | 0.94

[0.03,30.66] | - |

Mortality due to rebleeding

A total of 27 trials with 2,447 patients

investigated all 11 treatments and reported death due to

rebleeding. The evidence network presented in Fig. S1B connects all of the treatments.

Cochran's Q test did not identify any statistical heterogeneity

among the selected trials for this outcome measure (Heterogeneity

I2=0, P=0.9963, Table

III). Compared with TIPS alone, ES plus propranolol increased

the risk of mortality due to rebleeding (OR=10.39, 95% CI:

2.24-48.26, Fig. 2B; P-score=0.0842;

Table II).

Pairwise comparisons indicated that ES plus EVL, EVL

alone, EVL combined with nadolol plus ISMN, Nadolol plus ISMN,

Propranolol plus ISMN and TIPS alone were significantly more

effective than ES alone in reducing mortality due to rebleeding

(OR=0.23, 95% CI: 0.08-0.69; OR=0.37, 95% CI: 0.21-0.63; OR=0.18,

95% CI: 0.04-0.70; OR=0.29, 95% CI: 0.12-0.69; OR=0.17, 95% CI:

0.04-0.77; OR=0.12, 95% CI: 0.04-0.35, respectively, Table III).

Mortality due to liver failure

A total of 24 trials with 2,258 patients

investigating all 11 treatments reported on death due to liver

failure. The evidence network presented in Fig. S1C connects all of the treatments. No

statistical heterogeneity was observed (Heterogeneity

I2=0%, P=0.8985; Table

III). The results of the fixed-effects model analysis comparing

with TIPS alone indicated that none of the other treatments were

superior, though nadolol plus ISMN may be the next best option

(OR=0.51, 95% CI: 0.22-1.20, Fig.

2C; P-score=0.7536; Table II).

Furthermore, EVL combined with nadolol plus ISMN had the lowest

P-score (P-score=0.2167, Table II),

indicating the highest probability to increase mortality due to

liver failure. Results of pairwise comparisons indicated no

statistically significant differences when comparing with

treatments other than TIPS (Table

III).

Treatment failure

In total, 14 trials with a total of 1,445 patients

reported on treatment failure. No data of this outcome were

available for the treatment regimen ES plus propranolol. The

evidence network in Fig. S1B

connects the other 10 treatments for assessment of this outcome.

Mild heterogeneity was identified for treatment failure

(Heterogeneity I2=29.4%, P=0.1739; Table III). A fixed-effects model analysis

was performed for comparing with TIPS alone. Differences were not

statistically significant (Fig. 2D).

The evidence network presented in Fig.

S1D connects all of the treatments. EVL plus propranolol had

the highest efficacy (P-score=0.8071), closely followed by TIPS

(P-score=0.7938) and EVL plus nadolol (P-score=0.7932). ES alone

ranked last (P-score=0.0199), suggesting that it was most likely to

have the highest rate of treatment failure. Rankings are presented

in Table II.

Pooled ORs suggested that ES alone was

disadvantageous compared with the other 9 treatments with regard to

treatment failure (OR=3.72, 95% CI: 1.30-10.67 compared with ES

plus EVL; OR=2.13, 95% CI: 1.31-3.45 compared with EVL alone;

OR=8.65, 95% CI: 1.77-42.15 compared with EVL plus nadolol;

OR=3.69, 95% CI: 1.65-8.27 compared with EVL plus nadolol plus

ISMN; OR=9.09, 95% CI: 2.08-39.68 compared with EVL plus

propranolol; OR=3.02, 95% CI: 1.22-7.53 compared with EVL plus

propranolol plus ISMN; OR=2.78, 95% CI: 1.54-5.02 compared with

nadolol plus ISMN; OR=2.54, 95% CI: 1.06-6.12 compared with

propranolol plus ISMN; OR=8.24, 95% CI: 2.16-31.40 compared with

TIPS alone; Table III).

Bleeding from gastroesophageal

ulcer

A total of 24 trials with a total of 2,258 patients

investigated all 11 treatments and reported death due to bleeding

from gastroesophageal ulcer. The evidence network is presented in

Fig. S1E. There was no

statistically significant heterogeneity for this outcome measure

(Heterogeneity I2=0, P=0.8354; Table III). Results of the fixed-effects

model analysis performed in comparison with TIPS alone indicated

that none of the other 10 treatments were superior, but nadolol

plus ISMN appeared to be the best among the compared treatments

(OR=0.85, 95% CI: 0.09-8.18, Fig.

2E; P-score=0.7536, Table

II).

Nadolol plus ISMN had the highest P-score

(P-score=0.7536), indicating that it had the highest probability of

reducing mortality due to rebleeding, followed closely by ES alone

(P-score=0.6964) and ES plus propranolol (P-score=0.6651). The

lowest P-score was obtained for EVL plus nadolol and ISMN

(P-score=0.2167), indicating the lowest probability to reduce

bleeding from gastroesophageal ulcer (Table II).

Pairwise comparisons among the treatments indicated

that nadolol plus ISMN was associated with a relatively lower risk

of causing bleeding from gastroesophageal ulcer when compared with

ES alone (OR=0.11, 95% CI: 0.02-0.48), ES plus EVL (OR=0.06, 95%

CI=0.00-0.97) or EVL alone (OR=0.12, 95% CI: 0.03-0.56) in Table III.

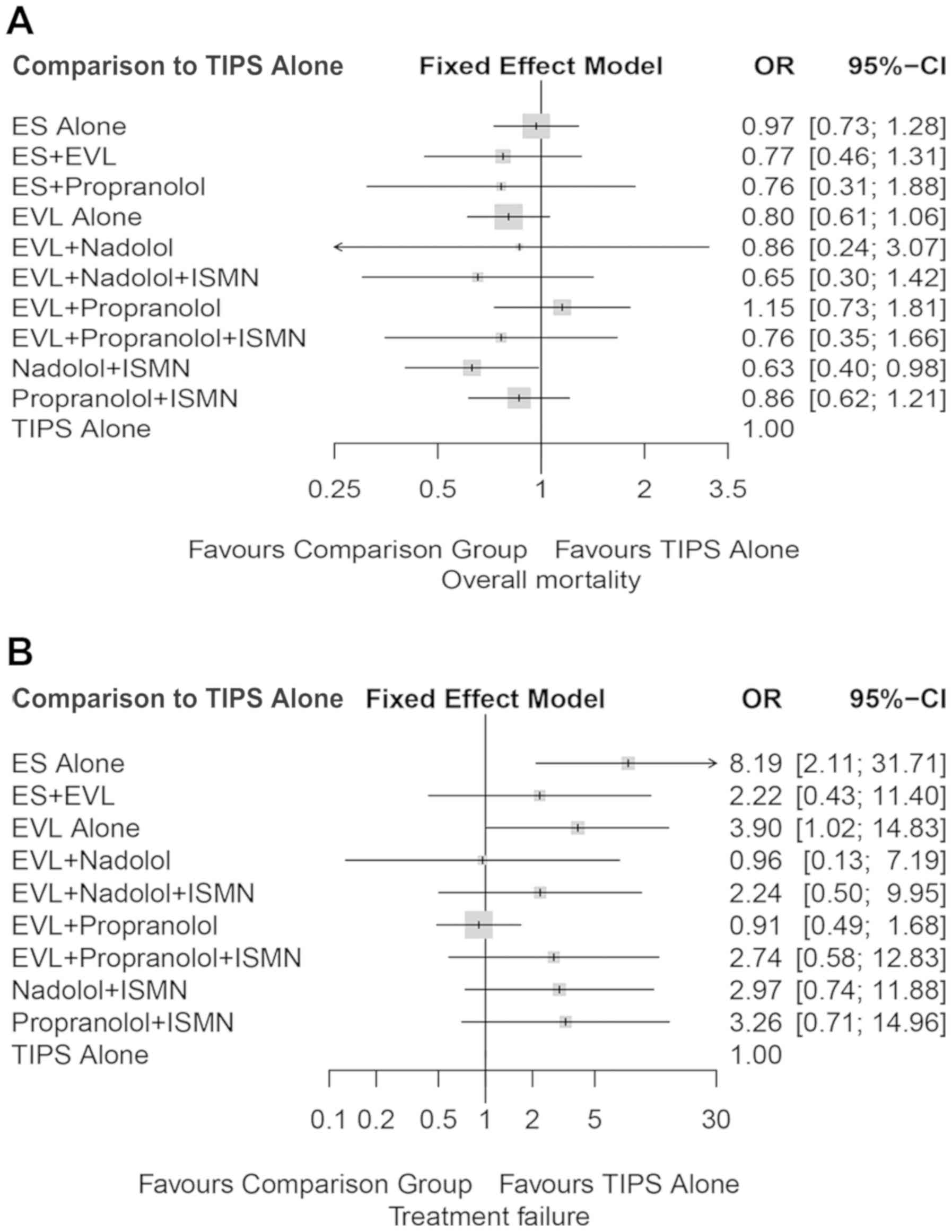

Sensitivity analysis

A sensitivity analysis was performed by removing

several studies. The only criterion for removal was a mean

follow-up time of <6 months, based on which 5 trials (43,47,55,60,61) were

removed. The results were consistent with those of the primary

meta-analysis (Table IV). Nadolol

plus ISMN was still superior to TIPS with regard to overall

mortality (OR=0.63, 95% CI: 0.40-0.98, Fig. 3A; Heterogeneity I2=0,

P=0.9249, Table IV), while no

significant differences were obtained for treatment failure

(OR=2.97, 95% CI: 0.74-11.88, Fig.

3B; Heterogeneity I2=37.3%, P=0.1206, Table IV).

| Table IVHeterogeneity test results. |

Table IV

Heterogeneity test results.

| Item | I2

(%) | Q | DF | P-value |

|---|

| Overall

mortality | 0 | 19.34 | 32 | 0.9618 |

| Overall mortality

(sensitivity analysis) | 0 | 18.05 | 28 | 0.9249 |

| Mortality due to

rebleeding | 0 | 5.97 | 18 | 0.9963 |

| Treatment

failure | 29.4 | 12.76 | 9 | 0.1739 |

| Treatment failure

(sensitivity analysis) | 37.3 | 12.75 | 8 | 0.1206 |

| Bleeding from

gastroesophageal ulcer | 0 | 4.23 | 8 | 0.8354 |

| Mortality due to

liver failure | 0 | 8.58 | 15 | 0.8985 |

Discussion

The present network meta-analysis included 43

randomized controlled trials to compare the treatment effectiveness

of 11 mainstay secondary prophylaxes in patients with cirrhosis in

terms of mortality, treatment failure and bleeding from

gastroesophageal ulcers. The results suggested that nadolol plus

ISMN was most likely to reduce the risk of overall mortality,

mortality due to liver failure and bleeding from gastroesophageal

ulcers, and was superior to ES and TIPS alone for reducing overall

mortality. ES was inferior to 9 treatments for reducing treatment

failure. The combination of endoscopic therapy and NSBB with or

without ISMN was not significantly more effective than EVL or the

drug combination alone.

The present study included 4 trials that

investigated nadolol plus ISMN (26,36,51,57) with

a total of 250 randomized patients. Nadolol plus ISMN was indicated

to be more effective than TIPS alone in reducing overall mortality.

The present results are consistent with those of Villanueva et

al (28), which concluded that

combination therapy was more effective than endoscopic ligation for

the prevention of recurrent bleeding and was associated with lower

rates of major complications. As a vasoconstrictor, nadolol is able

to reduce portal pressure and blood flow in the porto-collateral

system. The vasodilator ISMN has been demonstrated to decrease

portal pressure in patients with cirrhosis by reducing

intra-hepatic resistance (29).

Despite adverse drug-associated effects, including hypotension,

asthenia and headaches, proper dosage of this combination is most

likely to reduce mortality and other complications of bleeding from

ulcers.

In the newly published AASLD and UK guidelines, TIPS

is recommended as a treatment option when endoscopic and

pharmacologic treatments have failed (5). In the present study, a total of 16

trials provided data for TIPS in 590 patients with cirrhosis

(20,21,25-27,29,30,32-35,38-40,42,43).

The mean follow-up time for TIPS groups was 748.5 days [data for

one trial (43) were not available].

Although TIPS is known to have the potential to increase hepatic

encephalopathy (20,27), the present study demonstrated that it

may reduce the risk of death due to rebleeding. The trials were

contradictory regarding whether TIPS is superior to endoscopic or

combination therapies. In one previous trial (26), TIPS alone was superior to EVL plus

propranolol in the prevention of rebleeding, but this superiority

did not result in improved survival. In this previous study

(26), liver failure, hepatobiliary

cancer and sepsis were the predominant causes of death. Clinically,

it may be difficult to attribute death to rebleeding or to any one

cause. Zheng et al (62)

performed a meta-analysis of 12 RCTs to compare TIPS with

endoscopic therapy, and the results suggested that TIPS reduced

variceal rebleeding, but was associated with an increased risk of

encephalopathy, although no differences in survival were observed.

The present study indicated that TIPS was superior to ES alone, ES

plus propranolol and EVL alone with a tendency for reduced

mortality due to rebleeding. In clinical practice, TIPS has certain

advantages in reducing portal pressure and reducing the risk of

rebleeding. However, compared with endoscopic treatment, TIPS is

more costly and technically more difficult.

Data from 4 previous studies (21,26,27,38) that

used covered stents in their trials provided similar results among

TIPS, EVL, EVL plus propranolol and propranolol plus ISMN in terms

of overall mortality, although TIPS appeared to cause less

mortality due to rebleeding than EVL plus propranolol (21).

Although ES was not recommended by the Baveno VI

Consensus Workshop as a first-line treatment (15), it is still commonly used in China

(61). Furthermore, the guidelines

of the Chinese Society of Gastroenterology, Chinese Medical

Association and Chinese Society of Endoscopy suggest that

physicians choose EVL or ES for secondary prophylaxis based on

their experience and the patients' clinical conditions (62). Therefore, RCTs on ES were not

excluded from the present study.

Results of pooled ORs demonstrated inferiority of ES

regarding treatment failure over the other 9 treatments. ES plus

propranolol may increase the risk of mortality due to rebleeding.

No statistically significant benefit of ES alone or ES plus drugs

was identified in the present study. The results of the present

study are consistent with those of previous studies (7-12,15)

and support the most recent UK and AASLD guidelines, which do not

recommend ES for secondary prevention of variceal bleeding in

patients with cirrhosis (5).

EVL has been accepted as the preferred endoscopic

treatment for the prevention of variceal rebleeding (37). Although EVL plus NSBB is now the

first-line treatment, a review by Cotoras et al (64) reported that addition of β-blockers to

EVL does not lead to a difference in mortality. In line with this,

in the present study, the combination of EVL and NSBB with or

without ISMN was not more effective than EVL alone or the drug

combination of NSBB and ISMN.

The present study identified a tendency of EVL plus

propranolol to increase mortality, which may be attributed to the

data that were extracted from the included trials for this outcome

measure. In a previous trial whose patients all had grade II-IV

portal vein thrombosis (PVT), Luo et al (21) determined that the ability of EVL plus

propranolol to reduce variceal bleeding may be counteracted by

deteriorated PVT. Additional evidence from high-quality RCTs is

required to address this issue.

The present study has several limitations. Therapy

using drugs alone or using drugs other than NSBB or ISMN were

beyond the scope of the present study, as regimens of single drugs

are now seldom used in clinical practice for secondary prophylaxis.

Although the included trials provided a solid foundation based on

collected data, more data on serious adverse effects, the frequency

and severity of drug-associated adverse effects,

procedure-associated complications and consequent hospitalization

may be helpful for further comparison. The quality of the present

study depends on the RCTs that were included. A total of 4 RCTs

focusing on acute variceal bleeding (37,38,47,54) were

included, as they also assessed the outcomes of rebleeding and

overall mortality. The included references were published between

1992 and 2015, which is a long period of time; there may be

technical differences in the early stages; however, with the

continuous standardization and maturity of operation technology,

the differences are gradually narrowing. Therefore, the clinical

value of the present results may be limited.

In conclusion, the present network meta-analysis

suggested that for prophylaxis of variceal rebleeding in patients

with cirrhosis, nadolol plus ISMN may be the preferred choice to

decrease mortality and ES may be associated with a relatively

higher risk of unfavourable treatment outcomes, particularly

treatment failure.

Supplementary Material

Evidence network with regard to (A)

overall mortality, (B) mortality due to rebleeding, (C) mortality

due to liver failure, (D) treatment failure and (E) bleeding from

gastroesophageal ulcer.

Risk of bias assessment in included

randomized controlled trials.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr Sam Zhong and Dr

Michelle Liu (Shanghai KNOWLANDS MedPharm Consulting Co.,Ltd.) for

their support with data analyses in the present study.

Funding

No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed in the present

study are availabled from the correspoding author on reasonable

request.

Authors' contributions

YK was responsible for the study design, data

collection and analysis and manuscript review. LS reviewed the data

collection and analysis and drafted the manuscript. Both authors

read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Bresci G: Portal hypertension: The

management of esophageal/gastric varices, portal hypertensive

gastropathy or hypertensive colopathy. Therapy. 4:91–96. 2007.

|

|

2

|

Mansour L, El-Kalla F, EL-Bassat H,

Abd-Elsalam S, El-Bedewy M, Kobtan A, Badawi R and Elhendawy M:

Randomized controlled trial of scleroligation versus band ligation

alone for eradication of gastroesophageal varices. Gastrointest

Endosc. 86:307–315. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Sarin SK, Lahoti D, Saxena SP, Murthy NS

and Makwana UK: Prevalence, classification and natural history of

gastric varices: A long-term follow-up study in 568 portal

hypertension patients. Hepatology. 16:1343–1349. 1992.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Trudeau W and Prindiville T: Endoscopic

injection sclerosis in bleeding gastric varices. Gastrointest

Endosc. 32:264–268. 1986.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Tripathi D, Stanley AJ, Hayes PC, Patch D,

Millson C, Mehrzad H, Austin A, Ferguson JW, Olliff SP, Hudson M,

et al: U.K. guidelines on the management of variceal haemorrhage in

cirrhotic patients. Gut. 64:1680–1704. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Bosch J and García-Pagán JC: Prevention of

variceal rebleeding. Lancet. 361:952–954. 2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Brunner F, Berzigotti A and Bosch J:

Prevention and treatment of variceal haemorrhage in 2017. Liver

Int. 37 (Suppl 1):S104–S115. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Gonzalez R, Zamora J, Gomez-Camarero J,

Molinero LM, Bañares R and Albillos A: Meta-analysis: Combination

endoscopic and drug therapy to prevent variceal rebleeding in

cirrhosis. Ann Intern Med. 149:109–122. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Ravipati M, Katragadda S, Swaminathan PD,

Molnar J and Zarling E: Pharmacotherapy plus endoscopic

intervention is more effective than pharmacotherapy or endoscopy

alone in the secondary prevention of esophageal variceal bleeding:

A meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials. Gastrointest

Endosc. 70:658–664.e5. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Garcia-Tsao G, Abraldes J, Berzigotti A

and Bosch J: Portal Hypertensive Bleeding in Cirrhosis: Risk

Stratification, Diagnosis, and Management: 2016 practice guidance

by the American association for the study of liver diseases.

Hepatology. 65:310–335. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Thiele M, Krag A, Rohde U and Gluud LL:

Meta-analysis: Banding ligation and medical interventions for the

prevention of rebleeding from oesophageal varices. Aliment

Pharmacol Ther. 35:1155–1165. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Puente A, Hernández-Gea V, Graupera I,

Roque M, Colomo A, Poca M, Aracil C, Gich I, Guarner C and

Villanueva C: Drugs plus ligation to prevent rebleeding in

cirrhosis: An updated systematic review. Liver Int. 34:823–833.

2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Funakoshi N, Ségalas-Largey F, Duny Y,

Oberti F, Valats JC, Bismuth M, Daurès JP and Blanc P: Benefit of

combination β-blocker and endoscopic treatment to prevent variceal

rebleeding: A meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 16:5982–5992.

2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Garcia-Tsao G, Abraldes JG, Berzigotti A

and Bosch J: Portal hypertensive bleeding in cirrhosis: Risk

stratification, diagnosis, and management: 2016 practice guidance

by the American Association for the study of liver diseases.

Hepatology. 65:310–335. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

de Franchis R: BavenoV Faculty: Expanding

consensus in portal hypertension: Report of the Baveno VI Consensus

Workshop: stratifying risk and individualizing care for portal

hypertension. J Hepatol. 63:743–752. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Chen J, Zeng XQ, Ma LL, Huang XQ, Tseng

YJ, Wang J, Luo TC and Chen SY: Long-term efficacy of endoscopic

ligation plus cyanoacrylate injection with or without sclerotherapy

for variceal bleeding. J Dig Dis. 17:252–259. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Rücker G and Schwarzer G: Ranking

treatments in frequentist network meta-analysis works without

resampling methods. BMC Med Res Methodol. 15(58)2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Schwarzer G, Carpenter J and Rücker G:

Netmeta: Network meta-analysis with R (2016). R Package Version

0.9-2. netmeta, Cited February 22, 2016. Available from http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=netmeta.

|

|

19

|

Gupta V, Rawat R and Shalimar Saraya A:

Carvedilol versus propranolol effect on hepatic venous pressure

gradient at 1 month in patients with index variceal bleed: RCT.

Hepatol Int. 11:181–187. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Sauerbruch T, Mengel M, Dollinger M,

Zipprich A, Rössle M, Panther E, Wiest R, Caca K, Hoffmeister A,

Lutz H, et al: Prevention of rebleeding from esophageal varices in

patients with cirrhosis receiving small-diameter stents versus

hemodynamically controlled medical therapy. Gastroenterology.

149:p. 660–688.e1. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Luo X, Wang Z, Tsauo J, Zhou B, Zhang H

and Li X: Advanced cirrhosis combined with portal vein thrombosis:

A randomized trial of TIPS versus endoscopic band ligation plus

propranolol for the prevention of recurrent esophageal variceal

bleeding. Radiology. 276:286–293. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Kumar P, Saxena KN, Misra SP and Dwivedi

M: Secondary prophylaxis of variceal hemorrhage: A comparative

study of band ligation, carvedilol and propranolol plus isosorbide

mononitrate. Ind J Gastroenterology. 34(A54)2015.

|

|

23

|

Kong DR, Wang JG, Chen C, Yu FF, Wu Q and

Xu JM: Effect of intravariceal sclerotherapy combined with

esophageal mucosal sclerotherapy using small-volume sclerosant for

cirrhotic patients with high variceal pressure. World J

Gastroenterol. 21:2800–2806. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Kumar A, Jha SK, Sharma P, Dubey S, Tyagi

P, Sharma BC and Sarin SK: Addition of propranolol and isosorbide

mononitrate to endoscopic variceal ligation does not reduce

variceal rebleeding incidence. Gastroenterology. 137:892–901.

2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Sauer P, Hansmann J, Richter GM, Stremmel

W and Stiehl A: Endoscopic variceal ligation plus propranolol vs.

transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stent shunt: A long-term

randomized trial. Endoscopy. 34:690–697. 2002.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Gülberg V, Schepke M, Geigenberger G, Holl

J, Brensing KA, Waggershauser T, Reiser M, Schild HH, Sauerbruch T

and Gerbes AL: Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunting is

not superior to endoscopic variceal band ligation for prevention of

variceal rebleeding in cirrhotic patients: A randomized, controlled

trial. Scand J Gastroenterol. 37:338–343. 2002.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Escorsell A, Bañares R, García-Pagán JC,

Gilabert R, Moitinho E, Piqueras B, Bru C, Echenagusia A, Granados

A and Bosch J: TIPS versus drug therapy in preventing variceal

rebleeding in advanced cirrhosis: A randomized controlled trial.

Hepatology. 35:385–392. 2002.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Villanueva C, Miñana J, Ortiz J, Gallego

A, Soriano G, Torras X, Sáinz S, Boadas J, Cussó X, Guarner C and

Balanzó J: Endoscopic ligation compared with combined treatment

with nadolol and isosorbide mononitrate to prevent recurrent

variceal bleeding. N Engl J Med. 345:647–655. 2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Pomier-Layrargues G, Villeneuve JP,

Deschênes M, Bui B, Perreault P, Fenyves D, Willems B, Marleau D,

Bilodeau M, Lafortune M and Dufresne MP: Transjugular intrahepatic

portosystemic shunt (TIPS) versus endoscopic variceal ligation in

the prevention of variceal rebleeding in patients with cirrhosis: A

randomised trial. Gut. 48:390–396. 2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Narahara Y, Kanazawa H, Kawamata H, Tada

N, Saitoh H, Matsuzaka S, Osada Y, Mamiya Y, Nakatsuka K, Yoshimoto

H, et al: A randomized clinical trial comparing transjugular

intrahepatic portosystemic shunt with endoscopic sclerotherapy in

the long-term management of patients with cirrhosis after recent

variceal hemorrhage. Hepatol Res. 21:189–198. 2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Hou MC, Chen WC, Lin HC, Lee FY, Chang FY

and Lee SD: A new ‘sandwich’ method of combined endoscopic variceal

ligation and sclerotherapy versus ligation alone in the treatment

of esophageal variceal bleeding: A randomized trial. Gastrointest

Endosc. 53:572–578. 2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Meddi P, Merli M, Lionetti R, De Santis A,

Valeriano V, Masini A, Rossi P, Salvatori F, Salerno F, de Franchis

R, et al: Cost analysis for the prevention of variceal rebleeding:

A comparison between transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt

and endoscopic sclerotherapy in a selected group of Italian

cirrhotic patients. Hepatology. 29:1074–1077. 1999.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

García-Villarreal L, Martínez-Lagares F,

Sierra A, Guevara C, Marrero JM, Jiménez E, Monescillo A,

Hernández-Cabrero T, Alonso JM and Fuentes R: Transjugular

intrahepatic portosystemic shunt versus endoscopic sclerotherapy

for the prevention of variceal rebleeding after recent variceal

hemorrhage. Hepatology. 29:27–32. 1999.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Sauer P, Theilmann L, Stremmel W, Benz C,

Richter G and Stiehl A: Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic

stent shunt versus sclerotherapy plus propranolol for variceal

rebleeding. Gastroenterology. 113:1623–1631. 1997.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Sanyal AJ, Freedman AM, Luketic VA, Purdum

PP III, Shiffman ML, Cole PE, Tisnado J and Simmons S: Transjugular

intrahepatic portosystemic shunts compared with endoscopic

sclerotherapy for the prevention of recurrent variceal hemorrhage.

a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 126:849–857.

1997.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Villanueva C, Balanzó J, Novella MT,

Soriano G, Sáinz S, Torras X, Cussó X, Guarner C and Vilardell F:

Nadolol plus isosorbide mononitrate compared with sclerotherapy for

the prevention of variceal rebleeding. N Engl J Med. 334:1624–1629.

1996.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Li P, Kong RD, Xie HJ, Sun B and Xu JM:

Efficacy and safety of endoscopic variceal ligation and endoscopic

injection sclerotherapy in patients with cirrhosis and esophageal

varices: A prospective study. World Chinese J Digestology.

18:3791–3795. 2010.

|

|

38

|

Holster IL, Tjwa E, Moelker A, Wils A,

Hansen BE, Vermeijden JR, Scholten P, van Hoek B, Nicolai JJ,

Kuipers EJ, et al: Covered transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic

shunt versus endoscopic therapy+β-blocker for prevention of

variceal rebleeding. Hepatology. 63:581–589. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

van Buuren HR, Groeneweg M, Vleggaar FP,

Lesterrhuis W, Van Tillburg AJP, Hop WCJ, Peiterman H, Schalam SW,

van Hout BA and Lameris JS: The results of a randomized controlled

trial evaluating TIPS and endoscopic therapy in cirrhotic patients

with gastro-esophageal variceal bleeding. J Hepatol.

32(71)2000.

|

|

40

|

Cabrera J, Maynar M, Granados R, Gorriz E,

Reyes R, Pulido-Duque JM, Rodriguez SanRoman JL, Guerra C and

Kravetz D: Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt versus

sclerotherapy in the elective treatment of variceal hemorrhage.

Gastroenterology. 110:832–839. 1996.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Dobrucali A, Bal K, Tuncer M, Ilkova F,

Çelik A, Uzunismail H, Yurdakul I and Oktay E: Endoscopic banding

ligation compared with sclerotherapy for the treatment of

esophageal varies. Turk J Gastroenterol. 9:340–344. 1998.

|

|

42

|

Holster IL, Moelker A, Tjwa ET, et al:

Early transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) as

compared to endoscopic treatment reduces rebleeding but not

mortality in cirrhotic patients with a 1st or 2nd episode of

variceal bleeding: A multicentre randomized controlled trial.

United European Gastroenterology Journal. 1(A84)2013.

|

|

43

|

Merli M, Riggio O, Capocaccia L, et al:

TIPS vs sclerotherapy in preventing variceal rebleeding in

cirrhotic patients: Preliminary results of a randomised controlled

trial (EASL abstract). Journal of hepatology. 21(S41)1994.

|

|

44

|

Ahmad I, Khan AA, Alam A, Butt AK, Shafqat

F and Sarwar S: Propranolol, isosorbide mononitrate and endoscopic

band ligation-alone or in varying combinations for the prevention

of esophageal variceal rebleeding. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak.

19:283–286. 2009.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Argonz J, Kravetz D, Suarez A, Romero G,

Bildozola M, Passamonti M, Valero J and Terg R: Variceal band

ligation and variceal band ligation plus sclerotherapy in the

prevention of recurrent variceal bleeding in cirrhotic patients: A

randomized, prospective and controlled trial. Gastrointest Endosc.

51:157–163. 2000.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Avgerinos A, Armonis A, Manolakopoulos S,

Poulianos G, Rekoumis G, Sgourou A, Gouma P and Raptis S:

Endoscopic sclerotherapy versus variceal ligation in the long-term

management of patients with cirrhosis after variceal bleeding. A

prospective randomized study. J Hepatol. 26:1034–1341.

1997.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Avgerinos A, Armonis A, Stefanidis G,

Mathou N, Vlachogiannakos J, Kougioumtzian A, Triantos C,

Papaxoinis C, Manolakopoulos S, Panani A and Raptis SA: Sustained

rise of portal pressure after sclerotherapy, but not band ligation,

in acute variceal bleeding in cirrhosis. Hepatology. 39:1623–1630.

2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Avgerinos A, Rekoumis G, Klonis C,

Papadimitriou N, Gouma P, Pournaras S and Raptis S: Propranolol in

the prevention of recurrent upper gastrointestinal bleeding in

patients with cirrhosis undergoing endoscopic sclerotherapy. A

randomized controlled trial. J Hepatol. 19:301–311. 1993.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Baroncini D, Milandri GL, Borioni D,

Piemontese A, Cennamo V, Billi P, Dal Monte PP and D'Imperio N: A

prospective randomized trial of sclerotherapy versus ligation in

the elective treatment of bleeding esophageal varices. Endoscopy.

29:235–240. 1997.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

García-Pagán JC, Villanueva C, Albillos A,

Bañares R, Morillas R, Abraldes JG and Bosch J: Spanish Variceal

Bleeding Study Group: Nadolol plus isosorbide mononitrate alone or

associated with band ligation in the prevention of recurrent

bleeding: A multicentre randomised controlled trial. Gut.

58:1144–1150. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Hou MC, Lin HC, Kuo BI, Chen CH, Lee FY

and Lee SD: Comparison of endoscopic variceal injection

sclerotherapy and ligation for the treatment of esophageal variceal

hemorrhage: A prospective randomized trial. Hepatology.

21:1517–1522. 1995.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Hou MC, Lin HC, Lee FY, Chang FY and Lee

SD: Recurrence of esophageal varices following endoscopic reagent

and impact on rebleeding: Comparison of sclerotherapy and ligation.

J Hepatology. 32:202–208. 2000.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Lo GH, Lai KH, Cheng JS, Hwu JH, Chang CF,

Chen SM and Chiang HT: A prospective, randomized trial of

sclerotherapy versus ligation in the management of bleeding

esophageal varices. Hepatology. 22:466–4671. 1995.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Lo GH, Lai KH, Cheng JS, Lin CK, Huang JS,

Hsu PI and Chiang HT: Emergency banding ligation versus

sclerotherapy for the control of active bleeding from esophageal

varices. Hepatology. 25:1101–1104. 1997.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Peña J, Brullet E, Sanchez-Hernández E,

Rivero M, Vergara M, Martin-Lorente JL and Garcia Suárez C:

Variceal ligation plus nadolol compared with ligation for

prophylaxis of variceal rebleeding: A multicenter trial.

Hepatology. 41:572–578. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

de la Peña J, Rivero M, Sanchez E, Fábrega

E, Crespo J and Pons-Romero F: Variceal ligation compared with

endoscopic sclerotherapy for variceal hemorrhage: Prospective

randomized trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 49:417–423. 1999.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Romero G, Kravetz D, Argonz J, Vulcano C,

Suarez A, Fassio E, Dominguez N, Bosco A, Muñoz A, Salgado P and

Terg R: Comparative study between nadolol and 5-isosorbide

mononitrate vs. Endoscopic band ligation plus sclerotherapy in the

prevention of variceal rebleeding in cirrhotic patients: A

randomized controlled trial. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 24:601–611.

2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

58

|

Stiegmann GV, Goff JS, Michaletz-Onody PA,

Korula J, Lieberman D, Saeed ZA, Reveille RM, Sun JH and Lowenstein

SR: Endoscopic sclerotherapy as compared with endoscopic ligation

for bleeding esophageal varices. N Engl J Med. 326:1527–1532.

1992.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

59

|

Umehara M, Onda M, Tajiri T, Toba M,

Yoshida H and Yamashita K: Sclerotherapy plus ligation versus

ligation for the treatment of esophageal varices: A prospective

randomized study. Gastrointest Endosc. 50:7–12. 1999.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

60

|

Viazis N, Armonis A, Vlachogiannakos J,

Rekoumis G, Stefanidis G, Papadimitriou N, Manolakopoulos S and

Avgerinos A: Effects of endoscopic variceal treatment on

oesophageal function: a prospective, randomized study. Eur J

Gastroenterol Hepatol. 14:263–269. 2002.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

61

|

Vinel JP, Lamouliatte H, Cales P, Combis

JM, Roux D, Desmorat H, Pradere B, Barjonet G and Quinton A:

Propranolol reduces the rebleeding rate during endoscopic

sclerotherapy before variceal obliteration. Gastroenterology.

102:1760–173. 1992.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

62

|

Zheng M, Chen Y, Bai J, Zeng Q, You J, Jin

R, Zhou X, Shen H, Zheng Y and Du Z: Transjugular intrahepatic

portosystemic shunt versus endoscopic therapy in the secondary

prophylaxis of variceal rebleeding in cirrhotic patients:

meta-analysis update. J Clin Gastroenterol. 42:507–516.

2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

63

|

Chinese Society of Gastroenterology,

Chinese Medical Association, Chinese Society of Endoscopy:

Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of esophageal and

gastric variceal bleeding in cirrhotic portal hypertension. Chinese

Society of Hepatology, Chinese Medical Association. Chinese Medial

Association. J Clin Hepatol 32: 203-219, 2016 (In Chinese).

|

|

64

|