Introduction

Ketone bodies, which are mainly generated from fatty

acids, are important alternative energy sources during fasting

(1,2). Mitochondrial

3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA synthase (HMGCS2; Nomenclature

Committee of the International Union of Biochemistry and Molecular

Biology classification no. EC 2.3.3.10) catalyzes the condensation

of acetoacetyl-CoA and acetyl-CoA to form

3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA (HMG-CoA), which is the

rate-limiting step of ketone body synthesis (3,4).

HMGCS2 deficiency (Online Mendelian Inheritance in

Man reference no. 605911) is a metabolic disorder caused by

mutations in the HMGCS2 gene, which consists of 10 exons

located on chromosome 1p12-13(5).

To date, nearly 30 cases that have been reported in the literature

describe an autosomal recessive inheritance pattern (6). Most patients present with symptomatic

hypoketotic hypoglycemia and hepatomegaly after a period of

prolonged fasting or intercurrent illness (6). Metabolic acidosis is often noted

during the acute phase (7-12).

During the metabolic crisis, the serum concentration of free fatty

acids (FFAs) is relatively high when compared with that of the

total ketone bodies (TKBs) (6). The

clinical presentation is similar to that observed with fatty acid

β-oxidation defects, but the urinary organic acids and blood

acylcarnitine profiles are non-specific in cases of HMGCS2

deficiency. Urinary 4-hydroxy-6-methyl-2-pyrone (4HMP) is a

possible specific marker of the disorder (10). While the use of liver samples for an

enzyme assay or immunoblotting aids in diagnosis (13), obtaining these samples is an

invasive procedure. The diagnosis of HMGCS2 deficiency is therefore

usually based on genetic analysis.

Genetic analyses were performed on several suspected

cases referred to Department of Pediatrics, Graduate School of

Medicine, Gifu-University (Gifu, Japan) from 2005. From these

cases, four patients carried six rare non-synonymous variants of

HMGCS2, among which five of the variants have, to the best

of our knowledge, not been reported previously. To confirm their

pathogenicity in vitro, the variant enzymes were expressed

in 293T cells and the Escherichia coli strain BL21(DE3).

Materials and methods

Cases

The patients in all four cases were born to

non-consanguineous Japanese parents with no family history of

inherited metabolic disease. All of the patients were born

uneventfully following an uncomplicated term pregnancy. Only

patient 3 was a light-for-date infant; the others had normal birth

weights. After birth, physical growth and neurological development

until the onset of disease were normal except for in patient 4.

Clinical features and the results of first blood examinations

showing metabolic decompensation are listed in Table I. Before enrolling the four patients

into this study, written informed consent was obtained from the

parents of each patient by their attending pediatrician. This study

was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Graduate School of

Medicine, Gifu University, Japan (approval no. 29-503).

| Table ILaboratory findings from a single

blood sample taken during hypoglycemic crisis in each of the four

patients with HMGCS2 variants. |

Table I

Laboratory findings from a single

blood sample taken during hypoglycemic crisis in each of the four

patients with HMGCS2 variants.

| |

Laboratory

findings | Mutation in

HMGCS2 |

|---|

| Patient | Sex | Age of onset

months | pH | BE mM | Glucose mM | TKBs mM | FFAs mM | FFAs/TKBs | Glucose x TKBs | AST IU/l | ALT IU/l | C0 µM | C2 µM | C2/C0 | Allele 1 | Allele 2 |

|---|

| 1 | F | 8 | 7.02 | -26.8 | 0.78 | 0.502 | 3.32 | 6.6 | 0.39 | 358 | 173 | 20.6 | 56.1 | 2.72 | p.S392L | p.R500H |

| 2 | M | 6 | 6.95 | -28.9 | 1.17 | 0.4 | 2.5 | 6.3 | 0.47 | 241 | 140 | 8.03 | 75.8 | 9.44 | p.G219E | p.R500C |

| 3 | M | 7 | 7.13 | -24.4 | 1.83 | 0.161 | 2.20 | 13.7 | 0.29 | 230 | 156 | 8.75 | 53.4 | 6.10 | p.M235T | p.S392L |

| 4 | F | 7 | 6.92 | -29.7 | 1.11 | | 2.39 | | | 193 | 154 | 10.9 | 23.0 | 2.12 | p.M235T | p.V253A |

On the day of symptom onset, in July 2013 (the exact

day remained anonymous to protect the patient's identity), patient

1 was 8 months old. She took breast milk in the early morning.

Afterward, she could not obtain sufficient nutrition orally and

gradually became lethargic, before she began vomiting at 6 PM. At

Nagoya City University Hospital (looked after by TI; Nagoya,

Japan), she presented with tachypnea, tachycardia and hepatomegaly,

prompting the first blood test. In spite of the immediate

correction of hypoglycemia with intravenous 20% glucose infusion,

metabolic acidosis progressed. Continuous hemodiafiltration was

performed for 12 h to improve severe acidosis. Urinary organic acid

analysis showed increased excretion of dicarboxylic acid. In total,

5 µl serum was used for acylcarnitine analysis using NeoSMAAT kit

(cat. nos. 509254, 509261 and 509278; https://www.sekisuimedical.jp/business/diagnostics/others/neosmaat/;

Sekisui Medical Co., Ltd.) and the LCMS-8040 instrument (Shimadzu

Corporation). Her metabolic state was stabilized within 2 days from

the onset and she recovered with no neurological complications.

On the day of symptom onset, in November 2014,

patient 2 was 6 months old. He had a low-grade fever and showed

loss of appetite. The next day, he began having diarrhea and

vomited three times in the evening. After showing impaired

consciousness 2 days later, the first blood test was performed.

Ultrasonography revealed an enlarged and fatty liver. He was

transferred to Fujita Health University Hospital (Toyoake, Japan),

where continuous hemodiafiltration was performed for 18 h in a

similar procedure to that performed on patient 1. In total, 6 µl

serum was used for acylcarnitine analysis using MS2

Screening Neo II kit (https://www.siemens-healthineers.com/jp/newborn-mass-screening/ms2-screening-series;

Siemens Healthineers) and API 3200™ LC-MS/MS System (SCIEX). He

recovered without neurological complications, similar to patient

1.

On the day of symptom onset, in October 2015,

patient 3 was 7 months old. He appeared drowsy in the afternoon and

then gradually developed tachypnea and loss of appetite. The next

morning, the first blood examination was performed and hepatomegaly

was identified at Kitasato University Hospital (looked after by KA;

Sagamihara, Japan). Two dried blood spots were used for

acylcarnitine analysis using MS2 Screening Neo II kit

(https://www.siemens-healthineers.com/jp/newborn-mass-screening/ms2-screening-series;

Siemens Healthineers) and API 3200™ LC-MS/MS System (SCIEX). A

computed tomography scan revealed an enlarged and fatty liver.

Hypoglycemia was immediately corrected by glucose infusion.

Metabolic acidosis was corrected by continuous bicarbonate infusion

(about 2 mEq/kg/h) for 5 h. He recovered without neurological

complications.

As a newborn, patient 4 was fed with both breast

milk and infant formula and showed normal physical growth until 3

months of age. Thereafter, she was fed with only breast milk and

her physical growth and development slowed down. On the day of

symptom onset, in November 2016, she was 7 months old. She vomited

twice around noon and then gradually developed tachypnea and

impaired consciousness. She was hospitalized at Kurume University

Hospital (Kurume, Japan) early the next morning because of severe

hypoglycemia and metabolic acidosis. An infusion of glucose and

bicarbonate was started immediately. The patient's enlarged liver

showed homogeneous hyperechogenicity compared with the kidney,

which suggested a fatty liver. After 11 h, her metabolic status and

consciousness had almost fully recovered. In total, 6 µl serum was

used for acylcarnitine analysis using Quattro Premier MS/MS (cat.

no. 7200000594; Waters Coporation). Labeled carnitine standards set

B-op (cat. no. NSK-B-OP-1; Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.) was

used as internal standards.

In all 4 cases, urinary organic acids were analyzed

using GCMS-QP2010 Plus (Shimadzu Corporation). Urine samples

containing 0.1 mg creatinine were used for this analysis. In

Patient 4, QP5050 GC/MS (Shimadzu Corporation) was also used for

confirmation. Urine sample containing 0.2 mg creatinine was used

for this analysis. Urine samples were prepared according to the

previous report (14). The

mass/charge ratios (m/z) used to detect 4-HMP were 73, 99,

127, 139, 155, 170, 183 and 198(10). The details of blood acylcarnitine

analyses were summarized in Table

SI.

On first evaluation, the results of urinary organic

acid analyses and blood acylcarnitine profiles in the acute phases

of all four cases were regarded as non-specific. Patients 1, 2 and

3 were suspected of having HMGCS2 deficiency, because they

presented with hypoketotic hypoglycemia and a high ratio of

FFAs/TKBs, which prompted sequencing of their HMGCS2 alleles

immediately. In the case of patient 4, because the value of TKBs

during hypoglycemia was unknown, a gene panel analysis was instead

performed. After their critical episode, each patient was advised

to avoid prolonged fasting and to receive glucose infusion

prophylactically during anorexia, to prevent another hypoglycemic

episode. Patients 1, 2 and 4 have been followed for 6, 5 and 3

years, respectively. They have grown and developed normally without

neurological sequelae and fatty liver disappeared in all three. No

data were obtained regarding the prognosis of patient 3 due to the

loss of follow-up.

Mutational analysis

To obtain the white blood cells, ~4 ml whole blood

sample was added to an equivalent volume of solution consisting of

3% (W/V) dextran and 0.9% (W/V) NaCl, which was incubated for 1 h

at room temperature to precipitate the red blood cells and to

obtain the supernatant. The supernatant was then centrifuged at

1,730 x g for 10 min at room temperature to precipitate the white

blood cells. Genomic DNA was purified from the white blood cells

using a Sepa Gene kit (EIDIA Co., Ltd.) following the

manufacturer's protocol. The genomic HMGCS2 sequence was

obtained from the National Center for Biotechnology (NCBI)

Reference Sequence Database (accession no.

NG_013348.1/NM_005518.3). The 10 exons of HMGCS2 from

patients 1, 2 and 3 were amplified by PCR using a TaKaRa Taq™

(Takara Bio Inc.) and flanking intronic primers (listed in Table SII) under the following

thermocycling conditions: Initial denaturation at 94˚C for 1 min,

followed by 35 cycles of 94˚C for 1 min, 54˚C for 1 min and 72˚C

for 1 min. DNA electrophoresis in 2% agarose gel was used to verify

successful amplification. The amplified DNA in the gel was

visualized with EtBr solution (cat. no. 315-90051; Nippon Gene Co.,

Ltd.). Each amplified DNA was sequenced by bidirectional Sanger

sequencing using BigDye™ Terminator v1.1 Cycle Sequencing kit (cat.

no. 4337450; Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.)

and a 3130xl Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The same primers as those listed in

Table SII were used to sequence

the amplified DNA.

In the case of Patient 4, the NextSeq Sequencing

System (Illumina, Inc.) at the Kazusa DNA Research Institute

(Kisarazu, Japan) was used to perform a mutation analysis based on

a DNA panel consisting of 193 genes (Table SIII). In the present study,

additional 25 genes were added to a previous DNA panel containing

168 genes to detect various inherited metabolic diseases, including

fatty acid oxidation, ketone body metabolism and transport and

glycogen storage diseases (15).

The customized probe was designed for target enrichment of the

panel genes by SureSelect DNA Advanced Design Wizard (v5.5;

https://earray.chem.agilent.com/suredesign/) and

obtained from Agilent technologies, Inc. (cat. no. 5190-4859;

Agilent technologies, Inc.). Because genomic DNA was subjected to

enzymatic fragmentation using a KAPA hyperplus library construction

kit (cat. no. KK8510; Roche Diagnostics) for Illumina short-read

next-generation sequencing, the insert DNA size of the resultant

library, but not the integrity of genomic DNA, was monitored on a

MultiNA microchip electrophoresis system (cat. no.

MCE®-202; Shimadzu Corporation). DNA sequencing was done

using a NextSeq 500/550 Mid Output kit v2.5 (75 bp paired end; 150

cycles; cat. no. 20024904; Illumina, Inc.) using a NextSeq 500

system (Illumina, Inc.). The loading concentration of the library

was 1.8 pM, which was quantified with a KAPA library quantification

kit (cat. no. KK4824; KAPA Biosystems; Roche Diagnostics). Variants

in protein-coding exonic regions and their 10-base flanking regions

were detected with the pipeline that was previously described

(15). Briefly, sequence reads were

aligned with the reference human genome (hg38; GCA_000001405.2)

using the Burrows-Wheeler Aligner ‘MEM’ v0.7.5a35 algorithm

(16). The duplicate reads were

removed using Picard-1.84's ‘MarkDuplicates’ command (http://broadinstitute.github.io/picard/). SNPs and

indels were called using VarScan2's v.2.3.3 (http://varscan.sourceforge.net) (17) and Genome Analysis Toolkit-3.6.0

(GATK) HaplotypeCaller and UnifiedGenotyper (18,19).

In silico analysis of identified novel rare

variants in the HMGCS2 gene was performed for all 4 cases

using MutationTaster (https://www.mutationtaster.org/) (20), Polymorphism Phenotyping version 2

(http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2/), Protein

Variation Effect Analyzer (PROVEAN) and Sorting Intolerant from

Tolerant (SIFT) (11 Dec, 2019; https://provean.jcvi.org/index.php).

Construction of two HMGCS2 expression

vectors: One eukaryotic and one prokaryotic

The first step was to clone wild-type full-length

HMGCS2 cDNA (NCBI sequence no.: NM_005518.3), which contains

a mitochondrial targeting sequence, into the EcoRI site of

the eukaryotic expression vector pCAGGS (21), which was performed by DNA Synthesis

Services (GenScript Japan, Inc.). Next, the cDNA fragment encoding

HMGCS2 without the mitochondrial targeting sequence was

amplified by PCR from the eukaryotic expression vector using KOD FX

Neo (Toyobo Life Science) and primers containing BamHI and

EcoRI restriction sequences (italics), respectively:

Forward,

5'-CGCGGATCCCTGGAAGTTCTGTTCCAGGGTCCTACAGCCTCTGCTGTCC-3'; and

reverse, 5'-GAGGAGTGAATTCTTAAACGG-3' under the following

cycling conditions: Initial denaturation at 95˚C for 2 min,

followed by 45 cycles of 98˚C for 10 sec, 58˚C for 30 sec and 68˚C

for 45 sec. The underlined segment of the forward primer is the

recognition sequence of PreScission protease (GE Healthcare), which

was used in subsequent experiments. The amplified fragment was

digested by BamHI and EcoRI, then subcloned into the

bacterial expression vector pGEX-6P-1 (GE Healthcare), which

included the coding sequence of the fusion protein glutathione

s-transferase (GST). The synthesized constructs were transformed

into the E. coli strain JM109 (Toyobo Life Science).

Positive clones were confirmed by the Sanger method and agarose gel

electrophoresis to analyze the size of DNA fragments after

enzymatic digestion of plasmid DNA (data not shown). These plasmid

constructs were purified by an Automatic DNA Isolation system PI-50

(Kurabo Industries, Ltd.) and stored for subsequent experiments.

The simplified map of the bacterial expression vector is

illustrated in Fig. S1. A

pGEX-6P-1 empty vector was used for the expression of an isolated

GST protein. Each variant was introduced into the two HMGCS2

expression vectors (one eukaryotic and one prokaryotic) using a

KOD-Plus mutagenesis kit and KOD-Plus-Neo by following the

manufacturer's instructions (Toyobo Life Sciences, Ltd.).

Transient expression of HMGCS2 in

HEK293T cells and western blotting

293T cells (RIKEN Bioresource Center) were used for

expression experiments. Mycoplasma testing was done using an EZ-PCR

Mycoplasma test kit (Biological Industries) according to the

manufacturer's instructions. Each eukaryotic expression construct

(2 µg) containing wild-type or variant HMGCS2, or empty

vector was transfected into 3x105 293T cells using

Lipofectamine® 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.).

After 1 day, the transfected cells were lysed with 200 µl hypotonic

lysis buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, 10 mM NaCl, 0.5% Triton X-100, 10 mM

EDTA, pH 7.5). Protein in the soluble fraction was quantified by

the Bradford protein assay using Bio-Rad Protein Assay Dye Reagent

Concentrate (cat. no. 500-0006; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.)

(22). Each protein sample (HMGC2,

20 µg; β-actin, 5 µg) was subjected to electrophoresis in a 10%

polyacrylamide gel containing sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS-PAGE),

then transferred to 0.2-µm PVDF membrane using iBlot 2 Dry Blotting

System (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The membranes were then

blocked in TBS supplemented with 0.1% Tween 20 and 5% BSA (cat. no.

015-21274; FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation) for 70 min at

room temperature. The membranes were probed with a rabbit

polyclonal antibody (1:795; cat. no. ab104807; Abcam) against a

synthetic peptide corresponding to a region within C-terminal amino

acids 444-493 of human HMGCS2 (NCBI reference sequence: NP_005509)

or a monoclonal anti-β-actin antibody produced in mouse (1:10,000;

cat. no. A5441; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) for 1 h at room

temperature. This is followed by incubation with the secondary

antibodies for 1 h at room temperature and Amersham™ ECL™ Prime

Western Blotting Detection Reagent (GE Healthcare) for detection.

The secondary antibody used to detect HMGCS2 was horseradish

peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG H + L (cat. no. W4011;

Promega Corporation), whilst that used to detect β-actin was

Amersham ECL sheep anti-mouse IgG, HRP-linked whole Ab (cat. no.

NA931-1ML; Cytiva). Both antibodies had been diluted to 1:10,000

before use.

Expression in E. coli, purification

and western blotting of HMGCS2

Wild-type and mutant HMGCS2 expression vectors were

transformed into the E. coli strain BL21 (DE3; BioDynamics

Laboratory Inc.) grown in lysogeny broth (LB) medium (0.5% NaCl, 1%

tryptone and 0.5% yeast extract; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.)

containing 0.1 mg/ml ampicillin to an A600 of 0.9-1.1 at 37˚C.

Optimal protein expression was induced with 0.3 mM

isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical

Corporation) at 18˚C for 16 h. Cells were recovered by

centrifugation at 1,800 x g at 4˚C for 10 min, resuspended in lysis

buffer A [50 mM HEPES, 200 mM NaCl, pH 7.5, 10% glycerol, 1 mM

dithiothreitol (DTT), 1.1 mM 4-(2-Aminoethyl)-benzenesulfonyl

fluoride] and disrupted by sonication at 0˚C, with 10-sec

sonications repeated 25 times. The interval between each sonication

was 50 sec. After centrifugation at 15,000 x g at 4˚C for 30 min,

the soluble fraction was loaded into a column containing

Glutathione Sepharose 4 Fast Flow (GE Healthcare) before the column

was washed with lysis buffer B (50 mM HEPES, 200 mM NaCl, pH 7.5,

10% glycerol, 1 mM DTT) followed by wash buffer (50 mM HEPES, 200

mM NaCl, pH 7.5, 10% glycerol, 1 mM DTT, 0.5% [v/v] Triton X-100).

Triton X-100 was removed by washing the column again with lysis

buffer B. The GST fusion protein was eluted from the column using

elution buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 9.8 mM reduced glutathione, pH

8.0). After exchanging the buffer with cleavage buffer (50 mM

Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.5, 1 mM DTT) by filtration

and dialysis, GST was separated from HMGCS2 by treatment with

PreScission protease (GE Healthcare) at 4˚C for 12 h. PreScission

protease and separated GST were removed from the mixture by running

it through the Glutathione Sepharose 4 Fast Flow column again.

Purified HMGCS2 was quantified by absorbance at 280 nm using a

NanoDrop™ 1,000 Spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.).

An isolated GST protein was created using the same procedure for

HMGCS2 proteins. To compare the purity of each enzyme, 600 ng each

partially purified wild-type or variant HMGCS2 was separated by 10%

SDS-PAGE transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane. The membrane

was used for Ponceau staining and subsequent Western blotting. TBS

supplemented with 5% BSA was used as the blocking agent. The

nitrocellulose membrane was then blocked for 3 h at room

temperature. The membrane was probed with a rabbit polyclonal

antibody (cat. no. ab104807; Abcam) against a synthetic peptide

corresponding to a region within C-terminal amino acids 444-493 of

human HMGCS2 (NCBI reference sequence: NP_005509) for 17 h at room

temperature before being probed with the alkaline

phosphatase-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (Fc) secondary antibody,

(1:7,500; cat. no. S3731; Promega Corporation) for 70 min at room

temperature.

In another experiment, 450 ng each sample was

separated by 10% SDS-PAGE before the proteins in the gel were

stained with Coomassie brilliant blue R-250 (cat. no. 031-17922;

FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation) for 20 min at room

temperature. These samples were not transferred onto a

membrane.

Enzymatic activity assay for purified

HMGCS2

The spectrophotometric method described by

Clinkenbeard et al (23) was

used with modifications. Each protein sample (16.4-43.2 µg) was

incubated in 900 µl enzyme assay buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl, 100 µM

EDTA, 0.2% v/v Triton X-100, pH 8.2) containing 300 µM acetyl-CoA

(Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) for 17 min at 30˚C to prevent

inactivation of HMGCS2 by succinylation (24,25).

Next, 35 nmol acetoacetyl-CoA (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) were

added, where HMGCS2 activity was calculated from the rate of

decrease of acetoacetyl-CoA measured by spectrophotometry at 300

nm, at which the absorbance of the enolate form of acetoacetyl-CoA

was maximum (26). The molar

extinction coefficient of acetoacetyl-CoA is 3.6x103 in

this enzyme assay buffer (23).

Activity measurements were performed in three independent

experiments. Data are expressed as the mean ± SD.

Statistical analysis

One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Dunnett's

multiple comparison test was performed using Prism 8 software

(GraphPad Software, Inc.) to compare enzyme activities. P<0.05

was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

Mutational analysis

Six rare, non-synonymous variants of HMGCS2

were detected in the four study cases, comprising compound

heterozygotes of two variants (Fig.

S2; Table I). Two of the

variants, c.704T>C (p.M235T) and c.1175C>T (p.S392L), were

identified in two unrelated patients. Five of the variants are

novel mutations: c.656G>A (p.G219E), c.704T>C (p.M235T),

c.758T>C (p.V253A), c.1175C>T (p.S392L), and c.1498C>T

(p.R500C). Only the c.1499G>A (p.R500H) variant had been

reported previously as a pathogenic mutation (27,28).

In the mutation analysis of patient 4, the presence of any rare

variants in other genes known to be related to abnormal blood

glucose levels was not observed (Table

SIII). All five of the novel HMGCS2 variants were

evaluated in silico by MutationTaster, PolyPhen-2, PROVEAN

and SIFT to be disease-causing, probably damaging, deleterious and

damaging, respectively.

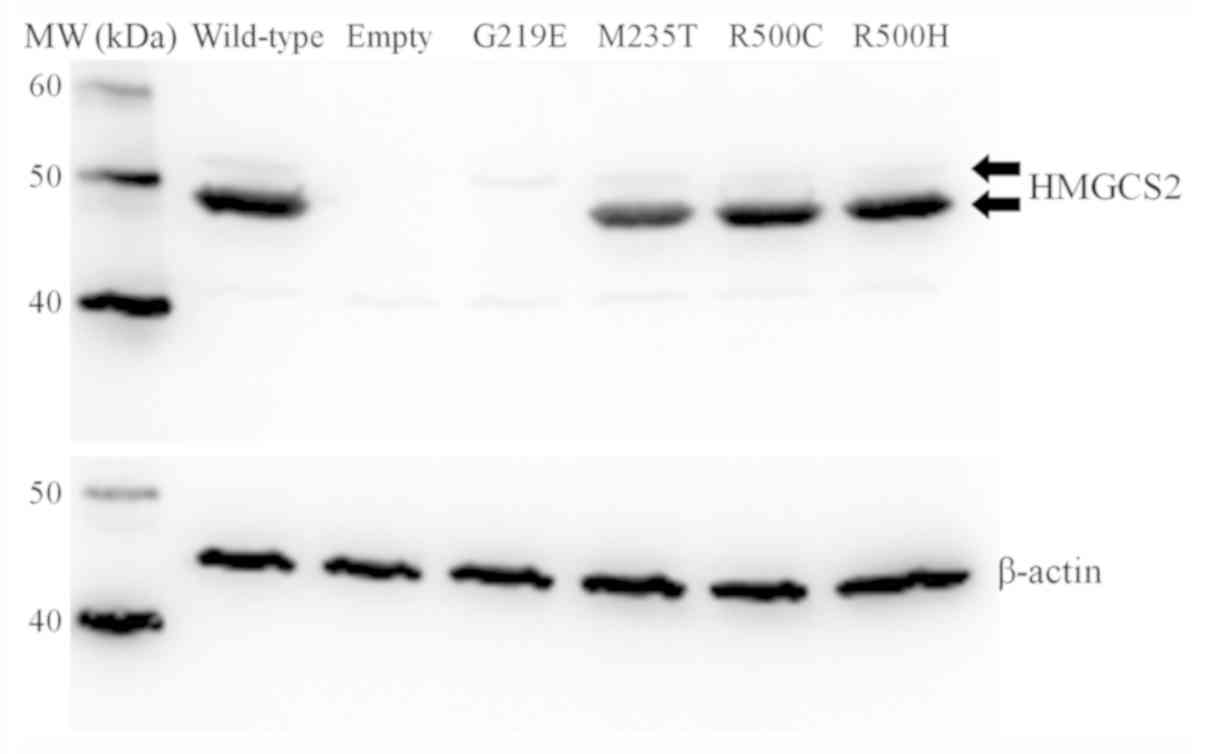

Transient expression and

immunoblotting of HMGCS2 in 293T cells

Full-length HMGCS2 cDNA contains a

mitochondrial targeting sequence. HMGCS2 is expressed in cytosol as

an immature protein with mitochondrial targeting peptide, which is

cleaved in the mitochondrial matrix (5,29).

Western blot analysis confirmed that immature HMGCS2 protein with

mitochondrial targeting peptide was expressed in all transfected

cells except for the empty vector-transfected cells, and each

expression level was similar (upper-band of the suitable molecular

weight of immature HMGCS2 protein with mitochondrial targeting

peptide). This result indicated by the western blot analysis

suggested that each transfection was successful (Fig. 1). An antibody against β-actin was

used as a protein loading control, confirming that the amount of

proteins in applied samples were similar (Fig. 1). The levels of mutant M235T, R500C

and R500H proteins without mitochondrial targeting peptide were

clearly detectable (lower-band). However, mutant G219E protein

without mitochondrial targeting peptide was not detectable, even

though immature protein with mitochondrial targeting peptide was

detected, as were wild-type and other mutants.

Expression and purification of HMGCS2

from E. coli

A wild-type HMGCS2-GST fusion protein that was

expressed in E. coli was successfully constructed. Wild-type

HMGCS2 protein was then purified using Glutathione Sepharose column

chromatography, PreScission protease cleavage and a second

Glutathione Sepharose column (Fig.

S3). Although extra protein bands remained in the purified

wild-type HMGCS2 preparation, a further purification step decreased

its enzyme activity, this partially purified preparation was used

in the enzymatic activity assay. From 1 g of cultured E.

coli 147 µg of wild-type HMGCS2 was purified.

The variant HMGCS2 proteins were expressed and

purified using the same procedure. The amounts of purified proteins

(µg) obtained from 1 g of E. coli expressing the HMGCS2

variants G219E, M235T, V253A, S392L and R500C were 42.2, 258,

147.8, 66.5 and 99.6, respectively.

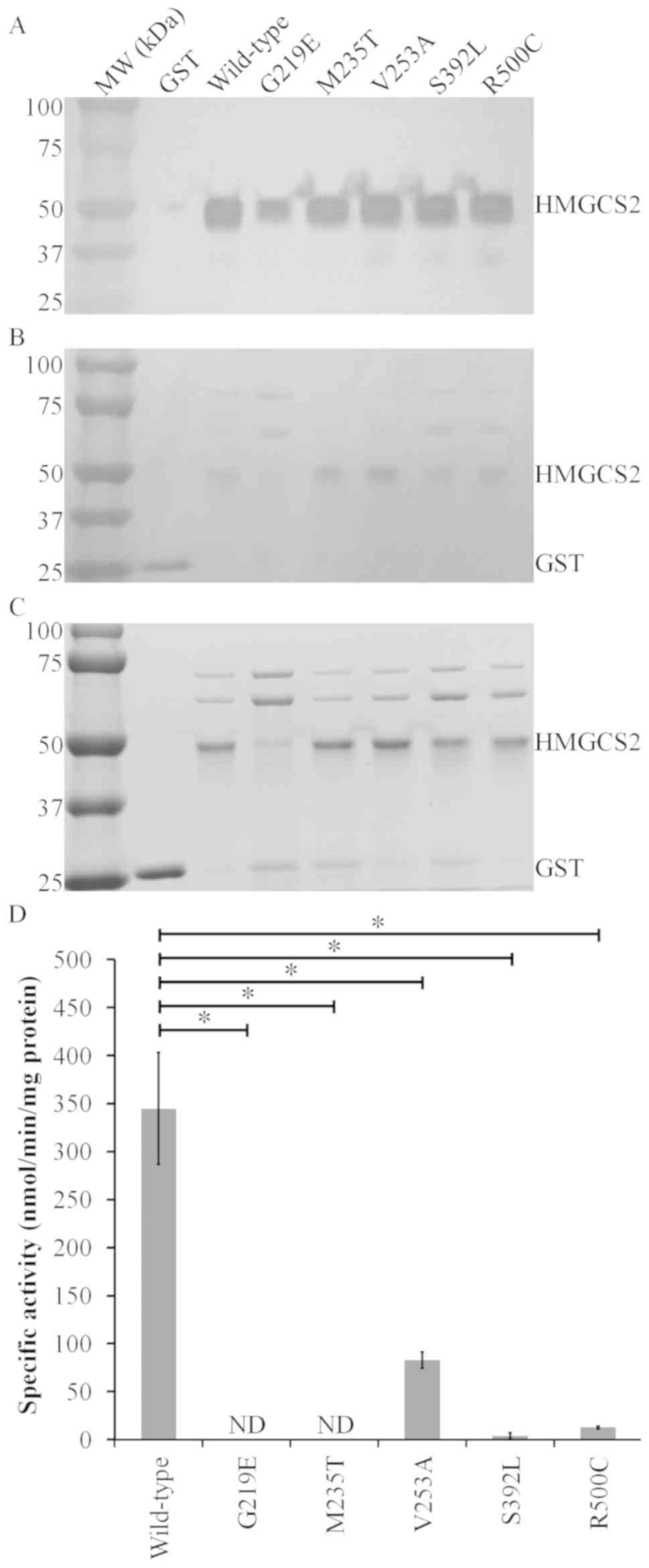

Fig. 2A-C shows

western blotting results, ponceau staining and coomassie brilliant

blue R-250 staining of each partially purified HMGCS2. The G219E

variant had a weaker signal compared with the wild-type and other

HMGCS2 variants, indicating that the purity of the G219E

preparation was lower than the others (Fig. 2A). The enzymatic activity of the

wild-type, V253A, R500C and S392L HMGCS2 were 345±58.2, 83±8.45,

12.7±1.30, and 3.6±3.43 nmol/min/mg protein, respectively, and

these activities of the variants were significantly lower than that

of wild-type. Only the V253A variant had some residual activity.

The other four variants had either no detectable activity or

negligible enzymatic activity. (Fig.

2D). Based on these expression analyses, it was concluded that

all five variants were pathogenic.

Discussion

In the present report, four cases of HMGCS2

deficiency have been described in Japanese patients. All four

patients presented with severe hypoketotic hypoglycemia with severe

metabolic acidosis, hepatomegaly or fatty liver with elevated liver

enzymes, elevated C2 and C2/C0 ratio in acylcarnitine analysis and

an elevated FFA level during an acute episode of metabolic

decompensation (Table I). Although

the TKBs measurement during the acute episode in Patient 4 was not

available, the other three patients had high FFAs/TKBs ratios.

Genetic analyses revealed that these patients were compound

heterozygotes of two variants. Five out of the six identified

variants were novel variants (Table

I). Initially a transient expression analysis of wild-type and

variant HMGCS2 was conducted in human fibroblasts, which was

established and SV40-transformed in the laboratory from a patient

with beta-ketothiolase deficiency and used in previous report

(30). In this earlier study it was

difficult to detect wild-type HMGCS enzyme activity. Using a

bacterial expression system that was previously used for

characterization of HMGCS2 mutants by other groups (28,31) it

was possible to confirm that these novel variants are

disease-causing missense mutations. The p.G219E mutant enzyme

appeared to be less stable than the wild-type enzyme, which was

also confirmed by the transient expression experiment in HEK293T

cells.

Clinically it is still challenging to recognize

HMGCS2 deficiency (10). A

non-ketotic hypoglycemic episode with a high FFAs/TKBs ratio is the

most important feature of HMGCS2 deficiency as well as

defects in fatty acid oxidation (6). Each fatty acid oxidation defect has a

characteristic profile in blood acylcarnitine analysis (32). In cases of HMGCS2 deficiency,

some reports have described that elevated C2 and C2/C0 ratios were

observed during acute episodes (11,12,33).

In the present study high C2 and relatively low C0 was also

observed in the patients. In HMGCS2 deficiency, the

β-oxidation pathway is intact and produces plenty of acetyl-CoA in

times of ketogenic stress, but acetyl-CoA cannot be used for

ketogenesis. Hence, it is reasonable that acetyl-CoA is accumulated

and produces acetylcarnitine (C2) in hepatocytes. However, in

patients with fatty acid oxidation defects, acetyl-CoA production

via β-oxidation is impaired. It may be hypothesized that

hypoketotic hypoglycemia with elevated C2 and C2/C0 ratios during

an acute crisis may be a promising indicator to identify

HMGCS2 deficiency. Urinary organic acid analysis shows

non-ketotic dicarboxylic aciduria in both HMGCS2 deficiency

and fatty acid oxidation defects. Recently, Pitt et al

(10) reported the presence of

characteristic urinary organic acids such as 4HMP during acute

episodes in patients with HMGCS2 deficiency.

Retrospectively, 4HMP was also detected in the urine samples of the

patients in the present study. It should be stressed that such

findings are only detected during acute episodes in both

acylcarnitine and urinary organic acid analyses (10).

Enzymatic assay of HMGCS2 activity is reported to be

challenging (5) and is currently

measured by the reduction of acetoacetyl-CoA spectrophotometrically

(13,28,31,34).

However, another cytosolic form of HMGCS and several other enzymes

may influence the assay because these enzymes utilize

acetoacetyl-CoA (34). The latter

might include mitochondrial acetoacetyl-CoA thiolase, mitochondrial

3-ketoacyl-CoA thiolase, cytosolic acetoacetyl-CoA thiolase, and

acyl-CoA hydrolase. Lascelles and Quant (34) measured HMGCS2 activity in human

liver samples. Whole lysates of transfected SV40-transformed

fibroblasts, which were derived from a patient with mitochondrial

acetoacetyl-CoA thiolase (T2) deficiency (30) and chosen because T2 is one of the

major enzymes that catalyzes acetoacetyl-CoA and thus could affect

the HMGCS2 enzyme assay, failed to show HMGCS2 enzymatic activity.

The expression level of HMGCS2 protein might have been too low to

overcome the other intrinsic enzymes that use acetoacetyl-CoA as a

substrate.

When the research strategy was changed to assay the

activity of HMGCS2 purified from a bacterial expression system

influences from other enzymes no longer needed to be considered.

Previously two reports described the successful characterization of

HMGCS mutants using bacterial expression systems (28,31).

In the bacterial expression system in the present study, enzyme

assays were performed without adding Mg2+.

Mg2+ can increase the absorbance of acetoacetyl-CoA

(26), but it inhibits HMGCS2 in a

concentration-dependent manner; for example, 10 mM Mg2+

in the assay buffer inhibits the reaction by 50% (35). The concentration of free

Mg2+ in the matrix of liver mitochondria is estimated to

range from 0.8 to 1.2 mM (36), so

the in vivo inhibition effect of Mg2+ would seem

to be quite small. While adopting this physiological concentration

of Mg2+ would have been ideal, a reliable molar

extinction coefficient of acetoacetyl-CoA at this physiological

condition was not found in the literature. Thus, in the present

study no Mg2+ was added to the enzyme assay buffer, even

though a previous report adopted 5-10 mM Mg2+ (34).

Enzymatic activity of the V253A variant was

approximately one quarter that of the wild-type enzyme, which was

much higher than the other four variants. The V253A variant was

found in patient 4. Patient 4 C2/C0 and C2 (acetylcarnitine) levels

were the lowest of all four patients, which is compatible with the

fact that this variant showed some residual activity in the

experiments. It may be hypothesized that a small amount of

acetyl-CoA in hepatocytes was transformed into ketone bodies in

Patient 4 by the V253A variant. The data suggest that the V253A

variant may be a disease-causing mutation. It shows lower enzymatic

activity than the R505Q variant, which was reported to be a

disease-causing mutation (31).

The enzyme kinetics of HMGCS2 were also challenging.

The V253A variant showed some residual activity, which led to

further analysis. Kinetic analysis of the V253A variant and

wild-type protein was performed. However, Km values for

acetoacetyl-CoA were too low to be evaluated accurately (data not

shown). An attempt to identify the Km value for

acetyl-CoA was also made. The Km value for acetyl-CoA in

this experiment was higher compared with that described previously

(data not shown) (28). This could

be because large amounts of acetyl-CoA were consumed during

preincubation. Enzyme kinetics of the variant should be further

researched to elucidate its pathophysiology in more detail.

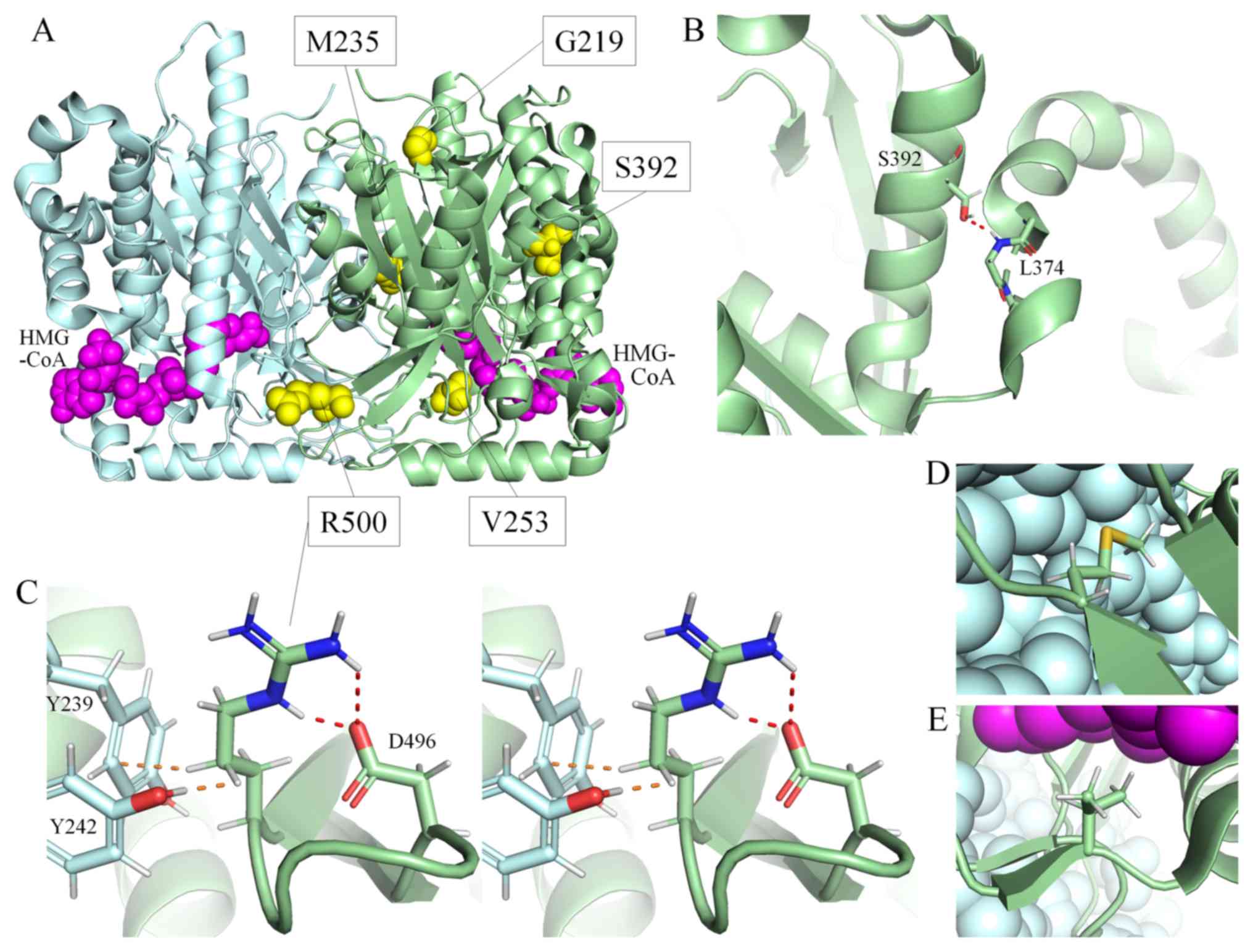

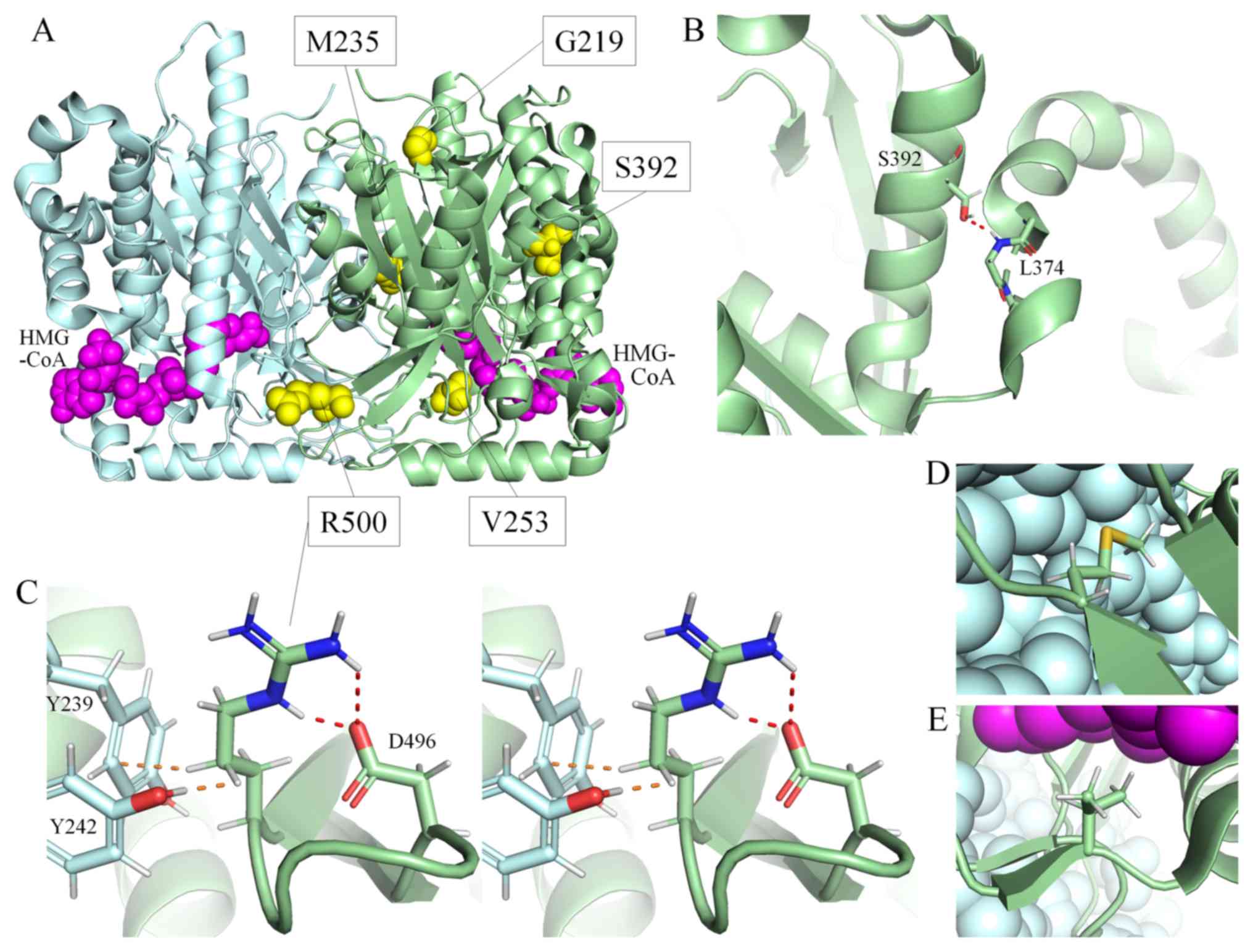

The three-dimensional structure of human HMGCS2

(Protein Databank ID: 2WYA) is shown in Fig. 3A. In this structure, two subunits

form a homodimer, which is crucial for its enzymatic activity

(31). The residues Glu132, Cys166

and His301 catalyze the reaction directly (37). The residues Ser392 and Leu374, each

a part of an α-helix, are connected by the only hydrogen bond

between these two alpha-helices (Fig.

3B). Replacing Ser392 with a Leu residue (S392L) would remove

this hydrogen bond and may alter the tertiary structure of HMGCS2.

Arg500 is located on the neighbor region of a beta-turn, and is

also located on the dimerization surface. Because the side chain of

Arg500 forms two hydrogen bonds with Asp496 (Fig. 3C), this beta-turn may become

unstable when these hydrogen bonds are lost due to the replacement

of Arg500 with Cys (variant R500C), which also could affect

dimerization. Met235 is located on the dimerization surface

(Fig. 3D). Because replacement of

this amino acid with Thr (M235T) would change the hydrophilicity of

this surface, it may affect dimerization. Val253 is one of the

residues that compose the active site of this enzyme (Fig. 3E), but is not directly involved in

the chemical reaction. Replacing this amino acid with Ala (V253A)

could alter the interaction of residues that compose the active

site, and would make it difficult to stabilize the substrates in an

appropriate position. In summary, the secondary structure may be

affected by R500C, the tertiary structure may be affected by S392L,

the quaternary structure may be affected by M235T and R500C and the

V253A variant would be expected to affect the binding to

substrates.

| Figure 3Three-dimensional structure of

HMGCS2, obtained using PyMOL Molecular Graphics System version

2.2.0. (A) The whole structure of wild-type HMGCS2, shown as a

homodimer. Each subunit is indicated by a green or cyan ribbon

diagram. The residues substituted in patients are shown as yellow

spheres. HMG-CoA is indicated by magenta spheres. (B) A partial

structure of wild-type HMGCS2. Ser392 and the main chain of Leu374

are shown as a stick model colored by atom type (cyan or green, C;

red, O; blue, N; white, H; and gold, S). The hydrogen bond between

Ser392 and Leu374 is shown as a dotted red line. (C) A partial

structure of wild-type HMGCS2 in cross-eye stereo view. The side

chains of Asp496 and Arg500, and those of Tyr239 and Tyr242 in

another subunit, are shown as a stick model. Hydrogen bonds are

shown as dotted red lines. The side chain of Arg500 forms two

hydrogen bonds with Asp496. Arg500 is also exposed to Tyr239 and

Tyr242 in another subunit. The shortest interatomic distances to

Arg500 from Tyr242 and Tyr239 (shown as dotted orange lines) are

170 and 280 picometers, respectively. (D) The side chain of Met235

shown as a stick model. Cyan spheres indicate another subunit. (E)

The side chain of Val253 shown as a stick model. HMG-CoA is

indicated by magenta spheres. Cyan spheres indicate another

subunit. HMGCS2, 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA. |

In conclusion, in vitro analysis has shown

that the p.G219E, p.M235T, p.V253A, p.S392L and p.R500C variants of

HMGCS2 are disease-causing mutations. In acylcarnitine

analysis, C2 and C2/C0 in the acute phase may be promising

indicators to differentiate HMGCS2 deficiency from fatty

acid oxidation defects.

Supplementary Material

Simplified map of the bacterial

expression vector. IPTG, isopropyl β-D-thiogalactoside.

Purification of wild-type HMGCS2

protein from Escherichia coli lysates. Sodium dodecyl

sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and Coomassie brilliant

blue R250 staining of protein fractions obtained by affinity

chromatography of wild-type HMGCS2 expressed in E. coli.

Lane 1, whole bacterial cell extract before induction with IPTG;

lane 2, whole bacterial cell extract after IPTG induction for 16 h;

lane 3, cell pellet after sonication; lane 4, supernatant after

sonication; lane 5, soluble fraction passed through a glutathione

sepharose bead column; lane 6, fraction eluted from the affinity

column; lane 7, solution after cleavage of the GST-HMGCS2 fusion

protein with PreScission protease; lane 8, solution after removal

of GST and PreScission protease. HMGCS2,

3.hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA; IPTG, isopropyl

β-D-thiogalactoside; GST, glutathione s-transferase.

DNA sequencing data of the four

patients using the Sanger method.

The details of blood acylcarnitine

analyses.

Sequences of the primers used for PCR

amplification of individual exons of the human HMGCS2

gene.

DNA panel of 193 metabolic disease

genes used for mutation analysis in patient 4. The top row refers

to classifications of genes in the panel.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express gratitude to Ms

Naomi Sakaguchi and Ms Sachie Hori, the Department of Pediatrics,

Gifu University (Gifu, Japan) assisted in these experiments as

laboratory assistants. Dr. Yuki Hasegawa of the Department of

Pediatrics, Shimane University Faculty of Medicine (Izumo, Japan)

confirmed the mas spectra of 4-HMP in all urine samples.

Funding

This research was supported in part by a

Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of

Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan (grant

no. 16K09962) and by grants from Japan Agency for Medical Research

and Development (grant no. JP17ek0109276), Health and Labor

Sciences Research Grants [H29-nanchitou(nan)-ippan-051] for

Research on Rare and Intractable diseases and The Morinaga

Foundation for Health & Nutrition.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the

current study are available in the Figshare repository (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.10308536.v1). All

datasets are additionally available from the corresponding author

on reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

KA, KF, YW, YN and TI were involved in clinical

management of the patients. MN, YA, HS, HM, RF and OO were involved

in mutation analysis. YA, HO, EA and HO were involved in expression

analyses. YA wrote the first draft of the manuscript. TF initiated

and supervised the study and reviewed and revised the manuscript.

All authors approved the final manuscript for submission to this

journal and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the

work.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

This study was approved by the Ethical Committee of

the Graduate School of Medicine, Gifu University, Japan and was

carried out in accordance with the principles contained within the

Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from the

parents of all patients.

Patient consent for publication

All parents of the patients agreed to the

publication of these data without identifying information by

signing informed consent.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Mitchell GA and Fukao T: Inborn errors of

ketone body metabolism. In: The metabolic & molecular basis of

inherited disease. Scriver CR, Beaudet AL, Sly WS and Valle D

(eds.). McGraw-Hill, New York, pp2327-2356, 2001.

|

|

2

|

Sass JO: Inborn errors of ketogenesis and

ketone body utilization. J Interit Metab Dis. 35:23–28.

2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Hegardt FG: Mitochondrial

3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA synthase: A control enzyme in

ketogenesis. Biochem J. 338:569–582. 1999.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Williamson DH, Bates MW and Krebs HA:

Activity and intracellular distribution of enzymes of ketone-body

metabolism in rat liver. Biochem J. 108:353–361. 1968.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Boukaftane Y and Mitchell GA: Cloning and

characterization of the human mitochondrial

3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl CoA synthase gene. Gene. 195:121–126.

1997.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Fukao T, Mitchell G, Sass JO, Hori T, Orii

K and Aoyama Y: Ketone body metabolism and its defects. J Inherit

Metab Dis. 37:541–551. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Wolf NI, Rahman S, Clayton PT and Zschocke

J: Mitochondrial HMG-CoA synthase deficiency: Identification of two

further patients carrying two novel mutations. Eur J Pediatr.

162:279–280. 2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Carpenter KH, Bhattacharya K, Ellaway C,

Zschocke J and Pitt JJ: Improved sensitivity for HMG CoA synthase

detection using key markers on organic acid screen. J Inherit Metab

Dis. 33(S62)2010.

|

|

9

|

Sass JO, Kuhlwein E, Klauwer D, Rohrbach M

and Baumgartner MR: Hemodiafiltration in mitochondrial

3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A synthase (HMG-CoA synthase)

deficiency. J Inherit Metab Dis. 36 (Suppl 2)(S189)2013.

|

|

10

|

Pitt JJ, Peters H, Boneh A, Yaplito-Lee J,

Wieser S, Hinderhofer K, Johnson D and Zschocke J: Mitochondrial

3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA synthase deficiency: Urinary organic

acid profiles and expanded spectrum of mutations. J Inherit Metab

Dis. 38:459–466. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Conboy E, Vairo F, Schultz M, Agre K,

Ridsdale R, Deyle D, Oglesbee D, Gavrilov D, Klee EW and Lanpher B:

Mitochondrial 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA synthase deficiency:

Unique presenting laboratory values and a review of biochemical and

clinical features. JIMD Rep. 40:63–69. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Lee T, Takami Y, Yamada K, Kobayashi H,

Hasegawa Y, Sasai H, Otsuka H, Takeshima Y and Fukao T: A Japanese

case of mitochondrial 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA synthase

deficiency who presented with severe metabolic acidosis and fatty

liver without hypoglycemia. JIMD Rep. 48:19–25. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Morris AA, Lascelles CV, Olpin SE, Lake

BD, Leonard JV and Quant PA: Hepatic mitochondrial

3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme a synthase deficiency. Pediatr

Res. 44:392–396. 1998.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Kimura M, Yamamoto T and Yamaguchi S:

Automated metabolic profiling and interpretation of GC/MS data for

organic acidemia screening: A personal computer-based system.

Tohoku J Exp Med. 188:317–334. 1999.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Fujiki R, Ikeda M, Yoshida A, Akiko M, Yao

Y, Nishimura M, Matsushita K, Ichikawa T, Tanaka T, Morisaki H, et

al: Assessing the accuracy of variant detection in cost-effective

gene panel testing by next-generation sequencing. J Mol Diagn.

20:572–582. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Li H and Durbin R: Fast and accurate short

read alignment with burrows-wheeler transform. Bioinformatics.

25:1754–160. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Koboldt DC, Zhang Q, Larson DE, Shen D,

McLellan MD, Lin L, Miller CA, Mardis ER, Ding L and Wilson RK:

VarScan 2: Somatic mutation and copy number alteration discovery in

cancer by exome sequencing. Genome Res. 22:568–576. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

McKenna A, Hanna M, Banks E, Sivachenko A,

Cibulskis K, Kernytsky A, Garimella K, Altshuler D, Gabriel S, Daly

M and DePristo MA: The genome analysis toolkit: A MapReduce

framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome

Res. 20:1297–1303. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Van der Auwera GA, Carneiro MO, Hartl C,

Poplin R, Del Angel G, Levy-Moonshine A, Jordan T, Shakir K, Roazen

D, Thibault J, et al: From FastQ data to high confidence variant

calls: The genome analysis toolkit best practices pipeline. Curr

Protoc Bioinformatics. 43:11.10.1–11.10.33. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Schwarz JM, Cooper DN, Schuelke M and

Seelow D: MutationTaster2: Mutation prediction for the

deep-sequencing age. Nat Methods. 11:361–362. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Song XQ, Fukao T, Yamaguchi S, Miyazawa S,

Hashimoto T and Orii T: Molecular cloning and nucleotide sequence

of complementary DNA for human hepatic cytosolic

acetoacetyl-coenzyme A thiolase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun.

201:478–485. 1994.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Bradford MM: A rapid and sensitive method

for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing

the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 72:248–254.

1976.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Clinkenbeard KD, Reed WD, Mooney RA and

Lane MD: Intracellular localization of the

3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzme A cycle enzymes in liver.

Separate cytoplasmic and mitochondrial 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl

coenzyme A generating systems for cholesterogenesis and

ketogenesis. J Biol Chem. 250:3108–3116. 1975.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Lowe DM and Tubbs PK:

3-Hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A synthase from ox liver

Properties of its acetyl derivative. Biochem J. 227:601–607.

1985.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Rardin MJ, He W, Nishida Y, Newman JC,

Carrico C, Danielson SR, Guo A, Gut P, Sahu AK, Li B, et al: SIRT5

regulates the mitochondrial lysine succinylome and metabolic

networks. Cell Metab. 18:920–933. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Decker K: Acetoacetyl Coenzyme A. In:

Methods of enzymatic analysis. 3rd edition, Vol. 7, Metabolites 2:

Tri- and dicarboxylic acids, purines, pyrimidines and derivatives,

coenzymes, inorganic compounds. Bergmeyer HU, Bergmeyer J and Graßl

M (eds.). Wiley-Blackwell, Hoboken, pp201-206, 1985.

|

|

27

|

Aledo R, Zschocke J, Pié J, Mir C, Fiesel

S, Mayatepek E, Hoffmann GF, Casals N and Hegardt FG: Genetic basis

of mitochondrial HMG-CoA synthase deficiency. Hum Genet. 109:19–23.

2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Ramos M, Menao S, Arnedo M, Puisac B,

Gil-Rodríguez MC, Teresa-Rodrigo ME, Hernández-Marcos M, Pierre G,

Ramaswami U, Baquero-Montoya C, et al: New case of mitochondrial

HMG-CoA synthase deficiency Functional analysis of eight mutations.

Eur J Med Genet. 56:411–415. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Neupert W: Protein import into

mitochondria. Annu Rev Biochem. 66:863–917. 1997.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Fukao T, Yamaguchi S, Scriver CR, Dunbar

G, Wakazono A, Kano M, Orii T and Hashimoto T: Molecular studies of

mitochondrial acetoacetyl-coenzyme A thiolase deficiency in the two

original families. Hum Mutat. 2:214–220. 1993.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Puisac B, Marcos-Alcalde I,

Hernandez-Marcos M, Tobajas Morlana P, Levtova A, Schwahn BC,

DeLaet C, Lace B, Gómez-Puertas P and Pié J: Human mitochondrial

HMG-CoA synthase deficiency: Role of enzyme dimerization surface

and characterization of three new patients. Int J Mol Sci.

19(1010)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Kompare M and Rizzo WB: Mitochondrial

fatty-acid oxidation disorders. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 15:140–149.

2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Aledo R, Mir C, Dalton RN, Turner C, Pié

J, Hegardt FG, Casals N and Champion MP: Refining the diagnosis of

mitochondrial HMG-CoA synthase deficiency. J Inherit Metab Dis.

29:207–211. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Lascelles CV and Quant PA: Investigation

of human hepatic mitochondrial 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme

A synthase in postmortem or biopsy tissue. Clin Chim Acta.

260:85–96. 1997.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Reed WD, Clinkenbeard D and Lane MD:

Molecular and catalytic properties of mitochondrial (ketogenic)

3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A synthase of liver. J Biol

Chem. 250:3117–3123. 1975.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Romani AM: Cellular magnesium homeostasis.

Arch Biochem Biophys. 512:1–23. 2011.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Shafqat N, Turnbull A, Zschocke J,

Oppermann U and Yue WW: Crystal structures of human HMG-CoA

synthase isoforms provide insights into inherited ketogenesis

disorders and inhibitor design. J Mol Biol. 398:497–506.

2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|