Introduction

As a common type of skeletal disorder, osteoporosis

is characterized by abnormal bone architecture and low bone mineral

density, resulting in increased risk of fracture (1). Osteoporosis was once considered an

inevitable disorder in the elderly population. Recently, multiple

prevention and treatment approaches have been developed for

osteoporosis (2). However, with the

growth of the aging population, the incidence of osteoporosis is

increasing worldwide, alongside increased treatment costs (3). Therefore, novel therapeutic approaches

with higher efficiencies are required to improve the treatment

outcomes of osteoporosis. Osteoblasts and osteoclasts serve

critical roles in bone formation and resorption, respectively

(4,5). However, molecular mechanisms that are

associated with this disease remain poorly understood (4,5),

leading to difficulties in the development of novel therapeutic

regimens.

p53 signaling is a well-studied pathway that plays

pivotal roles in diverse cellular processes, such as cell cycle

progression, genomic stability and cell apoptosis (6-8).

p53 can regulate the apoptosis of osteoblastic cells (9), which plays a key role in the

pathogenesis of osteoporosis (10).

Inhibition of p53 suppresses the apoptosis of osteoblasts, thereby

contributing to recovery from osteoporosis (11). It has been reported that the

development and progression of osteoporosis also requires the

involvement of long (>200 nt) non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), which

participates in diverse biological processes by regulating gene

expression (12). It has been

previously reported that WT1-AS can upregulate p53 in cervical

cancer to inhibit cancer progression (13). Therefore, WT1-antisense RNA (WT1-AS)

may also interact with p53 to participate in the development of

osteoporosis. The present study was performed to explore the

possible interaction between WT1-AS and p53 in osteoporosis.

Materials and methods

Research subjects

The present study included 60 patients with

osteoporosis (23 males and 37 females; age range 33-66 years; mean

age, 49.2±6.1 years) and 60 healthy volunteers (23 males and 37

females, 32-66 years; mean age, 49.6±6.3 years). All patients and

healthy volunteers were admitted to the First Affiliated Hospital

of Hainan Medical College between March 2015 and March 2018. The

inclusion criteria of patients were as follows: i) Newly diagnosed

cases; and ii) no initiated therapies. The exclusion criteria of

patient were as follows: i) Recurrent cases; and ii) complications

with other bone disorders or other types of diseases. All patients

were informed of the experimental principles, and gave their signed

informed consent. The Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated

Hospital of Hainan Medical College approved this study prior to the

admission of subjects. No significant differences in age, gender,

body mass index, or smoking and drinking history were indicated

between the two groups (data not shown). The T-score was calculated

using the following formula: T-score = (bone mineral

density-reference bone mineral density)/reference standard

deviation (14). The T-score of the

patients ranged from -2.5 to -4.7 (mean score, -3.3±0.4), while the

T-score for healthy volunteers ranged from -0.9 to 3.3 (mean score,

1.3±0.5). T-score was significantly lower in patients compared with

controls (data not shown). The disease duration of patients ranged

from 2.2 to 13.8 years, with a mean of 8.1±2.4 years.

Patient treatment and plasma sample

preparation

All 60 patients with osteoporosis were treated with

bisphosphonates, including alendronate, risedronate, zoledronic

acid and ibandronate. Estrogen was only used in females.

Bisphosphonates attenuate bone loss, and estrogen was used in

female patient to control postmenopausal symptoms (15). Drug doses were determined according

to patients' health conditions, disease severity and mid-term

treatment outcomes. Blood (5 ml) was extracted from each healthy

volunteer and patient under fasting conditions prior to therapy

initiation (1-3 days). The same amount of fasting blood was also

extracted from each patient with osteroporosis at 3 months after

therapy initiation. Blood samples were centrifuged at 1,200 x g

(room temperature) for 15 min to prepare plasma samples.

Transient transfection of

osteoblasts

In vitro experiments were performed using

primary osteoblasts purchased from Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA.

Primary osteoblasts were cultivated in Osteoblast Growth Medium

(PromoCell GmbH) at 37˚C. All subsequent experiments were performed

using cells from passage 4 or 5. WT1-AS and p53 expression vectors

(pcDNA3.1) and empty pcDNA3.1 vector, as well as small interfering

RNA (siRNA) negative control and WT1-AS siRNA, were synthesized by

Guangzhou RiboBio Co., Ltd. Osteoblasts (1x106) were

transfected with 10 nM WT1-AS or p53 expression vector, 10 nM empty

pcDNA3.1 vector (negative control, NC group), 40 nM WT1-AS siRNA,

or 40 nM siRNA NC (NC group). Non-transfected osteoblasts acted as

the control (C) group. Osteoblast RNA and protein were harvested at

24 h post-transfection for use in subsequent experiments.

ELISA

Human p53 ELISA kit (cat. no. ab46067; Abcam) was

used to measure levels of p53 in plasma samples. All steps were

performed following manufacturer's instructions. All plasma levels

of p53 were expressed as pg/ml.

RNA extraction and reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

A total of 1x106 osteoblasts and 2 ml of

plasma was mixed with 1 ml of RNAzol (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) to

extract total RNAs. DNase I (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.) was used to digest genomic DNA in all RNA samples at 37˚C for

1 h. Following that, a qScript cDNA Synthesis kit (Quantabio) was

used to perform RT (25˚C for 10 min, 55˚C for 20 min and 85˚C for

10 min). qPCR reaction mixtures were prepared using a KAPA SYBR

FAST qPCR Master Mix kit (Roche Diagnostics). GAPDH was used as an

endogenous control. Primer sequences were: WT1-AS, 5'-GCC

TCTCTGTCCTCTTCTTTG-3' (forward), 5'-GCTGT GAGTC CTGGTGCTTA-3'

(reverse); GAPDH, 5'-TTGGCATCGTTG AGGGTC-3' (forward),

5'-AGTGGGAACACGGAAAGC-3' (reverse); P53, 5'-AGAGTCTATAGGCCCACCCC-3'

(forward), 5'-GCTCGACGCTAGGATCTGAC-3' (reverse). PCR cycling

conditions were: 95˚C for 1 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95˚C for

10 sec and 58˚C for 50 sec. The expression levels of WT1-AS and p53

mRNA were normalized using the 2-ΔΔCq method (16).

Western blot analysis

Osteoblasts were lysed with 1 ml RIPA buffer

(Guangzhou RiboBio Co., Ltd.) to extract total protein. Protein

samples were quantified using a bicinchoninic acid kit (Sangon

Biotech Co., Ltd.), followed by denaturation in boiling water for 5

min. Electrophoresis was performed using 12% SDS-PAGE to separate

proteins (30 µg per well) according to their molecular weights.

Proteins were transferred to a PVDF membrane and blocking was

carried out in 5% non-fat milk for 2 h at room temperature. Primary

antibodies of rabbit GAPDH (1:1,200; cat. no. ab181602; Abcam) and

p53 (1:1,200; cat. no. ab131442; Abcam) were used to incubate the

membranes for 15 h at 4˚C. Horseradish peroxidase goat anti-rabbit

(immunoglobulin G; 1:1,100; cat. no. ab6721; Abcam) secondary

antibody was then used to blot the membranes further at room

temperature for 2 h. The ECL Chemiluminescence Detection kit

(Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd.) was used to develop protein signals.

Gray values were normalized using ImageJ version 1.46 (National

Institutes of Health).

Cell apoptosis analysis

A total of 6x104 osteoblasts were mixed

with 1 ml serum-free aforementioned cell culture medium to prepare

single-cell suspensions. Osteoblasts were cultivated at 37˚C and 5%

CO2 in a 6-well plate with 2 ml of cell suspension in

each well. Cells were incubated at 37˚C for 48 h before being

harvested and digested with 0.25% trypsin. Cells were subsequently

stained using Annexin V-FITC (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and

propidium iodide (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) at 4˚C for 20 min

in dark. Apoptotic cells were analyzed using a flow cytometer. Data

were processed using FCSalyzer Version 0.9.18 (SourceForge; DHI

Group, Inc.).

Statistical analysis

The mean ± SD values of three biological replicates

of each experiment were calculated and used for all comparisons.

Statistical power was calculated using Origin software version 10

(OriginLab Corp.) and a statistical power of ~0.9 was obtained.

Differences between patients and controls were measured using an

unpaired t-test. Differences between two time points in the patient

group were analyzed using a paired t-test. Differences among

different cell transfection groups were investigated using a

one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's test. Correlations were analyzed

using Pearson's correlation coefficient. A receiver operating

characteristic (ROC) curve was plotted for diagnostic analysis.

Patients with disease are grouped in the true positive class and

healthy controls are grouped in the true negative class. Patients

were divided into high and low WT1-AS/p53 level groups (n=30),

using the mean expression levels of WT1-AS/p53 in osteoporosis as a

cutoff score. Any association between patients' clinical data and

WT1-AS/p53 expression was analyzed using a χ2 test.

P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

WT1-AS and p53 levels are positively

correlated in patients with osteoporosis

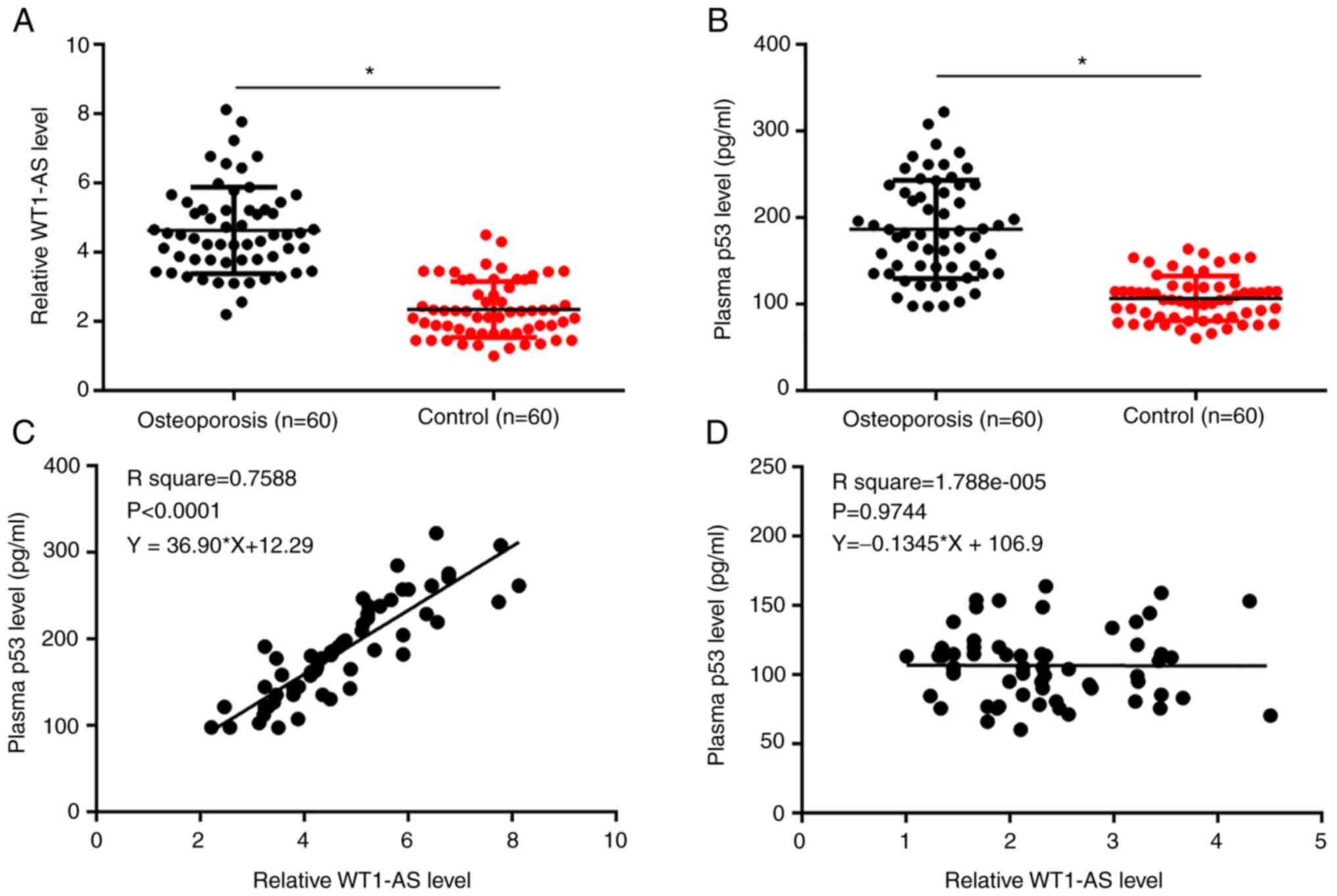

WT1-AS and p53 plasma levels were measured. Plasma

levels of WT1-AS (Fig. 1A) and p53

(Fig. 1B) were significantly higher

in patients with osteoporosis compared with the control group

(P<0.05). Correlations between WT1-AS and p53 were analyzed

using Pearson's correlation coefficient. WT1-AS and p53 levels were

significantly and positively correlated in patients with

osteoporosis (Fig. 1C,

P<0.0001), but not in healthy controls (Fig. 1D, P=0.9744). The T-score of the

patients ranged from -2.5 to -4.7. χ2 test revealed that

expression levels of WT1-AS and p53 were not associated with

patients' age, sex and smoking habits, but were closely associated

with T-score and disease duration (Table I).

| Table IAssociation between patients' clinical

data and WT1-AS and p53 expression. |

Table I

Association between patients' clinical

data and WT1-AS and p53 expression.

| A, WTI-AS |

|---|

| | Expression | |

|---|

| Index | High (n=30) | Low (n=30) | P-value |

|---|

| Age | | | >0.05 |

|

≥50

years | 14 | 15 | |

|

<50

years | 16 | 15 | |

| Sex | | | >0.05 |

|

Male | 13 | 10 | |

|

Female | 17 | 20 | |

| Smoking | | | >0.05 |

|

Yes | 11 | 10 | |

|

No | 19 | 20 | |

| Disease duration | | | <0.001 |

|

≥8

years | 22 | 6 | |

|

<8

years | 8 | 24 | |

| T score | | | |

|

≥-3.5 | 19 | 6 |

| B, p53 |

| | Expression | |

| Index | High (n=30) | Low (n=30) | P-value |

| Age | | | >0.05 |

|

≥50

years | 14 | 15 | |

|

<50

years | 16 | 15 | |

| Sex | | | >0.05 |

|

Male | 13 | 10 | |

|

Female | 17 | 20 | |

| Smoking | | | >0.05 |

|

Yes | 11 | 10 | |

|

No | 19 | 20 | |

| Disease

duration | | | <0.001 |

|

≥8

years | 22 | 6 | |

|

<8

years | 8 | 24 | |

| T score | | | |

|

≥-3.5 | 19 | 6 | 0.001 |

Altered expression of WT1-AS and p53

separates patients with osteoporosis from healthy controls

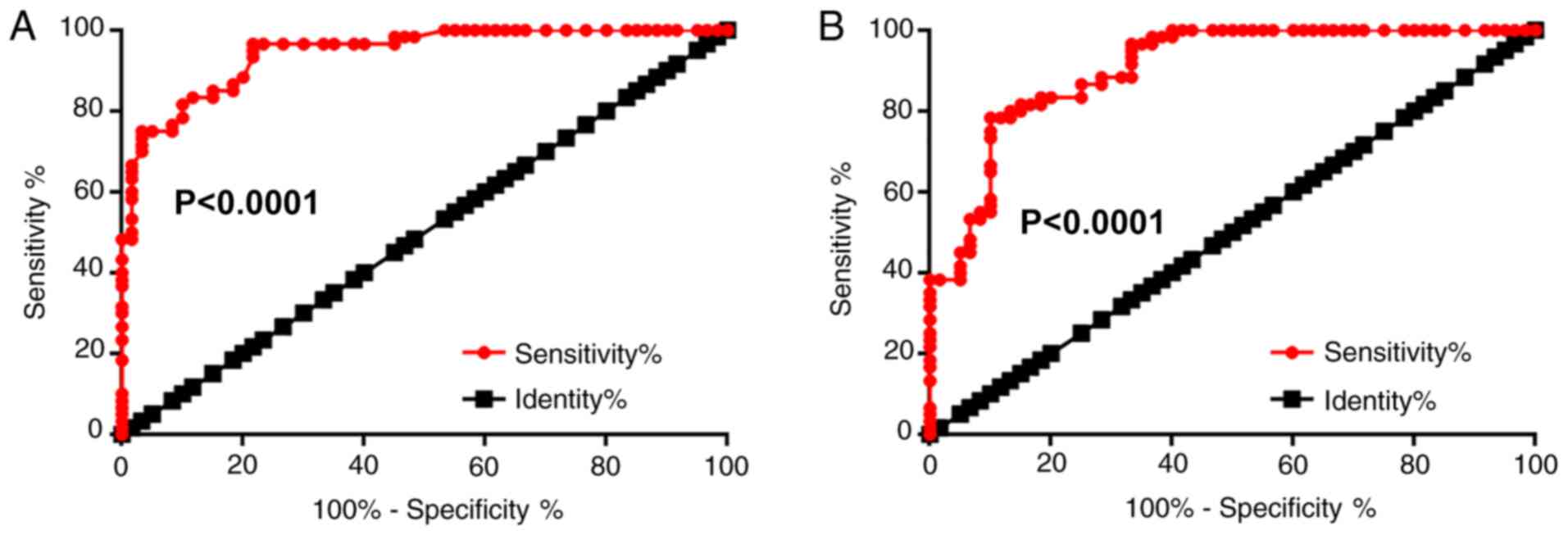

The potential application of plasma WT1-AS and p53

for the diagnosis of osteoporosis was explored by performing a ROC

curve analysis. The area under the curve (AUC) of plasma WT1-AS was

0.94 (95% confidence interval, 0.91-0.98; standard error, 0.019;

P<0.0001; Fig. 2A), while the

AUC of plasma p53 was 0.91 (95% confidence interval, 0.85-0.96;

standard error, 0.026; P<0.0001; Fig. 2B).

Bisphosphonate therapy downregulates

WT1-AS and p53 plasma levels in patients with osteoporosis

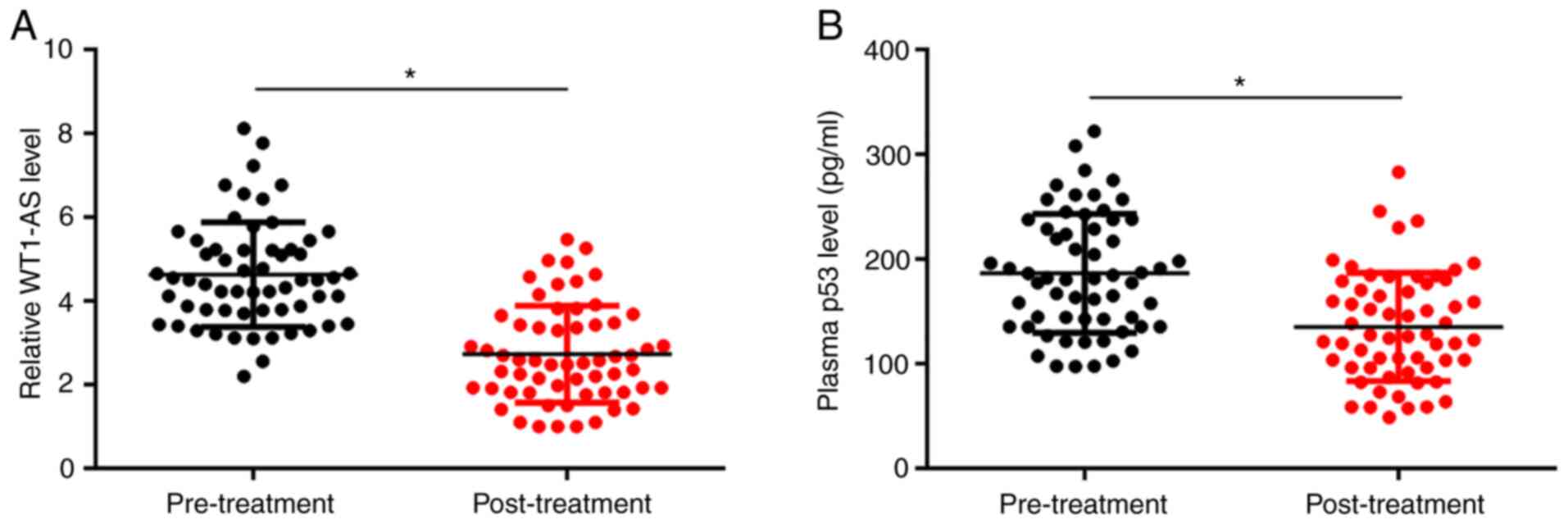

Plasma levels of WT1-AS and p53 were measured during

pre-treatment and at 3 months post-treatment. Levels of WT1-AS

(Fig. 3A) and p53 (Fig. 3B) significantly decreased at 3

months post-treatment compared with pre-treatment levels

(P<0.05).

WT1-AS positively regulates p53

expression in osteoblasts

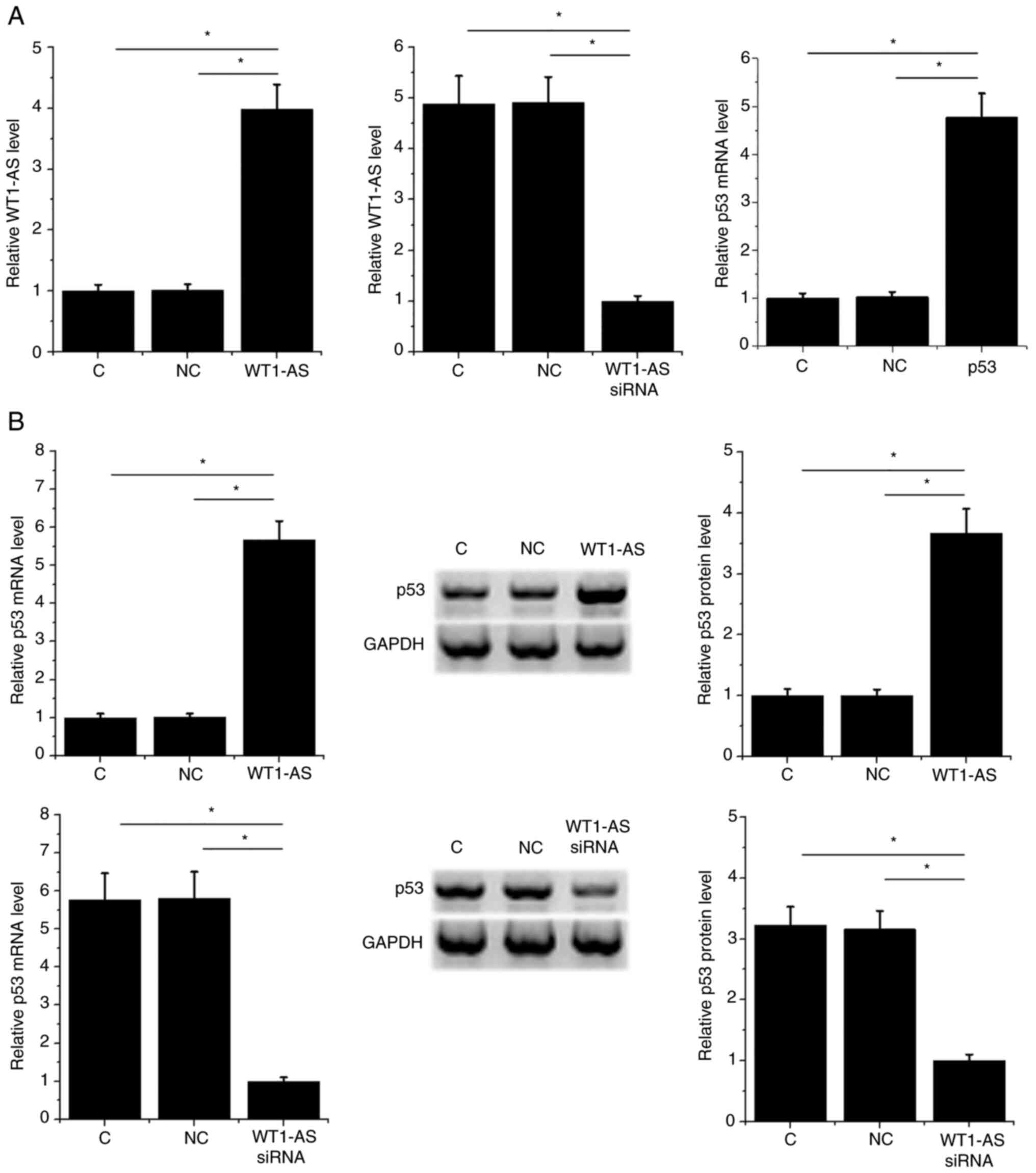

Osteoblasts were transfected with WT1-AS and p53

expression vectors and WT1-AS siRNA. WT1-AS and p53 expression was

significantly altered compared with NC and C groups at 24 h

post-transfection (P<0.05; Fig.

4A). Moreover, WT1-AS overexpression resulted in upregulated

p53 expression, while WT1-AS siRNA silencing resulted in

downregulated p53 expression at mRNA and protein levels compared

with the control and NC groups (P<0.05; Fig. 4B).

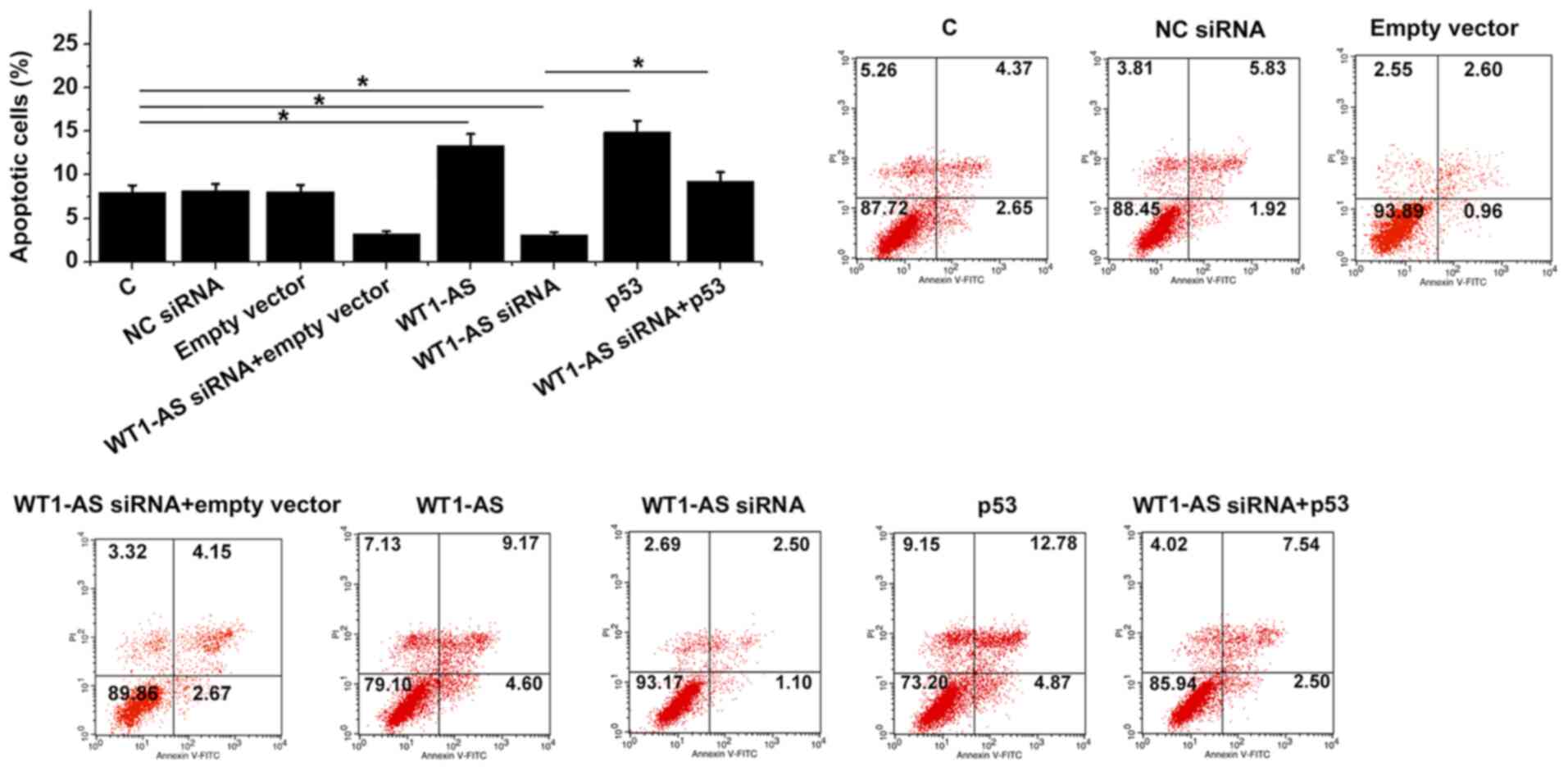

WT1-AS promotes osteoblast apoptosis

through p53

WT1-AS and p53 overexpression resulted in

significantly increased apoptosis rates, while WT1-AS siRNA

silencing resulted in significantly decreased rates of osteoblast

apoptosis compared with NC and C groups. In addition, p53

overexpression was indicated to attenuate the effect of WT1-AS

siRNA silencing on cell apoptosis in comparison to cells with

WT1-AS siRNA transfection alone (P<0.05; Fig. 5).

Discussion

To date, the functions of WT1-AS have only been

investigated in a few types of cancer (13,17,18).

The participation of WT1-AS in cancer biology is mainly mediated by

its roles in regulating cell behaviors such as proliferation,

apoptosis and invasion (3,17,16).

It is known that cell death in osteoblasts contributes to the

pathogenesis of osteoporosis (19).

The present study investigated the roles of WT1-AS in osteoporosis.

WT1-AS was upregulated in osteoporosis and exhibited diagnostic

values. In addition, WT1-AS was revealed to serve a role in

osteoblast apoptosis and indicated an association with p53, which

may indicate an interaction between the genes. Therefore,

overexpression of WT1-AS may promote the progression of

osteoporosis by promoting osteoblast apoptosis.

The diagnosis of osteoporosis mainly relies on the

measurement of bone mineral density (BMD) (20). However, the threshold of BMD to

diagnose osteoporosis is debated, and there is no way to use BMD to

screen people with high risk of osteoporosis (20). In the present study, ROC curve

analysis indicated that WT1-AS and p53 expression could be used to

distinguish patients with osteoporosis from healthy controls. In

addition, increased levels of WT1-AS and p53 were observed after

treatment with bisphosphonates or estrogen. Therefore, plasma

WT1-AS and p53 may be used as a marker to predict osteoporosis.

However, clinical trials are required to test sensitivity and

specificity.

The results of the current study revealed that

WT1-AS positively regulated the expression of p53 in osteoblasts.

The lack of significant correlation between WT1-AS and p53 across

the healthy controls suggested that the interaction between them

was indirect. It is known that lncRNAs can sponge miRNAs to

upregulate the expression of their downstream genes (21). Future studies should assess the

involvement of miRNAs and its interaction with lncRNAs. WT1-AS can

sponge miR-330-5p to regulate p53 in cervical cancer (13). Future studies should try to explore

the involvement of miRNAs in this process.

The present study only investigated the expression

of WT1-AS in plasma. Future studies should include patient

osteoclasts and animal model experiments to further verify the

results of the current study. The pathogenesis of osteoporosis is

complicated and requires the involvement of multiple factors, such

as epigenetic and hormonal factors (22-27).

The interactions between WT1-AS and these factors are needed to be

further analyzed.

However, the present study has limitations,

including the small sample size. Future studies with bigger sampler

sizes are required to further confirm the results of the current

study. The involvement of p53-related apoptotic factors, including

Bax and Bcl-2, was not explored and p53 knockdown experiments were

not included. The current study did not include osteoblast

functionality and proliferation assays and the analysis of changes

in the expression of marker genes. Therefore, future studies are

needed to examine these factors.

In conclusion, WT1-AS was demonstrated to be

upregulated in osteoporosis and promoted the apoptosis of

osteoblasts by upregulating p53.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: This research was supported by the Youth Foundation

Project of the First Affiliated Hospital of Hainan Medical College

in 2018 (grant no. HYFYPY201813) and Key R&D Program Projects

of Hainan Province in 2018 (grant no. ZDYF2018158).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current

study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable

request.

Authors' contributions

CW, QX and YZ designed experiments. CW and QX

performed experiments. WS and YL analysed data. YZ drafted the

manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated

Hospital of Hainan Medical College approved this study prior to the

admission of subjects.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Siris ES, Adler R, Bilezikian J, Bolognese

M, Dawson-Hughes B, Favus MJ, Harris ST, Jan de Beur SM, Khosla S,

Lane NE, et al: The clinical diagnosis of osteoporosis: A position

statement from the National Bone Health Alliance Working Group.

Osteoporos Int. 25:1439–1443. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Khosla S and Hofbauer LC: Osteoporosis

treatment: Recent developments and ongoing challenges. Lancet

Diabetes Endocrinol. 5:898–907. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Lötters FJB, van den Bergh JP, de Vries F

and Rutten-van Mölken MP: Current and future incidence and costs of

osteoporosis-related fractures in the Netherlands: Combining claims

data with BMD measurements. Calcif Tissue Int. 98:235–243.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Curtis EM, Moon RJ, Dennison EM, Harvey NC

and Cooper C: Recent advances in the pathogenesis and treatment of

osteoporosis. Clin Med (Lond). 15 (Suppl 6):S92–S96.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Raisz LG: Pathogenesis of osteoporosis:

Concepts, conflicts, and prospects. J Clin Invest. 115:3318–3325.

2005.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Reyes J, Chen JY, Stewart-Ornstein J,

Karhohs KW, Mock CS and Lahav G: Fluctuations in p53 signaling

allow escape from cell-cycle arrest. Mol Cell. 2018. 71:581–591.

e5. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Willms A, Schittek H, Rahn S, Sosna J,

Mert U, Adam D and Trauzold A: Impact of p53 status on

TRAIL-mediated apoptotic and non-apoptotic signaling in cancer

cells. PLoS One. 14(e0214847)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Yeo CQX, Alexander I, Lin Z, Lim S, Aning

OA, Kumar R, Sangthongpitag K, Pendharkar V, Ho VHB and Cheok CF:

p53 maintains genomic stability by preventing interference between

transcription and replication. Cell Rep. 15:132–146.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Hirasawa H, Tanaka S, Sakai A, Tsutsui M,

Shimokawa H, Miyata H, Moriwaki S, Niida S, Ito M and Nakamura T:

ApoE gene deficiency enhances the reduction of bone formation

induced by a high-fat diet through the stimulation of p53-mediated

apoptosis in osteoblastic cells. J Bone Miner Res. 22:1020–1030.

2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Weinstein RS and Manolagas SC: Apoptosis

and osteoporosis. Am J Med. 108:153–164. 2000.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Zhen YF, Wang GD, Zhu LQ, Tan SP, Zhang

FY, Zhou XZ and Wang XD: P53 dependent mitochondrial permeability

transition pore opening is required for dexamethasone-induced death

of osteoblasts. J Cell Physiol. 229:1475–1483. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Hao L, Fu J, Tian Y and Wu J: Systematic

analysis of lncRNAs, miRNAs and mRNAs for the identification of

biomarkers for osteoporosis in the mandible of ovariectomized mice.

Int J Mol Med. 40:689–702. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Cui L, Nai M, Zhang K, Li L and Li R:

lncRNA WT1-AS inhibits the aggressiveness of cervical cancer cell

via regulating p53 expression via sponging miR-330-5p. Cancer Manag

Res. 11:651–667. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Coulson KA, Reed G, Gilliam BE, Kremer JM

and Pepmueller PH: Factors influencing fracture risk, T score, and

management of osteoporosis in patients with rheumatoid arthritis in

the Consortium of Rheumatology Researchers of North America

(CORRONA) registry. J Clin Rheumatol. 15:155–160. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Al-Azzawi F: Prevention of postmenopausal

osteoporosis and associated fractures: Clinical evaluation of the

choice between estrogen and bisphosphonates. Gynecol Endocrinol.

24:601–609. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 25:402–408.

2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Du T, Zhang B, Zhang S, Jiang X, Zheng P,

Li J, Yan M, Zhu Z and Liu B: Decreased expression of long

non-coding RNA WT1-AS promotes cell proliferation and invasion in

gastric cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1862:12–19. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Dai SG, Guo LL, Xia X and Pan Y: Long

non-coding RNA WT1-AS inhibits cell aggressiveness via

miR-203a-5p/FOXN2 axis and is associated with prognosis in cervical

cancer. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 23:486–495. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Komori T: Cell death in chondrocytes,

osteoblasts, and osteocytes. Int J Mol Sci. 17(2045)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Lorentzon M and Cummings SR: Osteoporosis:

The evolution of a diagnosis. J Intern Med. 277:650–661.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Thomson DW and Dinger ME: Endogenous

microRNA sponges: Evidence and controversy. Nat Rev Genet.

17:272–283. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Yu Y, Newman H, Shen L, Sharma D, Hu G,

Mirando AJ, Zhang H, Knudsen E, Zhang GF, Hilton MJ, et al:

Glutamine metabolism regulates proliferation and lineage allocation

in skeletal stem cells. Cell Metab. 29:966–978. e4. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Hayashi M, Nakashima T, Yoshimura N,

Okamoto K, Tanaka S and Takayanagi H: Autoregulation of osteocyte

Sema3A orchestrates estrogen action and counteracts bone aging.

Cell Metab. 29:627–637.e5. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Fan Y, Hanai JI, Le PT, Bi R, Maridas D,

DeMambro V, Figueroa CA, Kir S, Zhou X, Mannstadt M, et al:

Parathyroid hormone directs bone marrow mesenchymal cell fate. Cell

Metab. 25:661–672. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Stegen S, van Gastel N, Eelen G,

Ghesquière B, D'Anna F, Thienpont B, Goveia J, Torrekens S, Van

Looveren R, Luyten FP, et al: HIF-1α promotes glutamine-mediated

redox homeostasis and glycogen-dependent bioenergetics to support

postimplantation bone cell survival. Cell Metab. 23:265–279.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Liu S, Liu D, Chen C, Hamamura K,

Moshaverinia A, Yang R, Liu Y, Jin Y and Shi S: MSC transplantation

improves osteopenia via epigenetic regulation of notch signaling in

lupus. Cell Metab. 22:606–618. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Mera P, Laue K, Ferron M, Confavreux C,

Wei J, Galán-Díez M, Lacampagne A, Mitchell SJ, Mattison JA, Chen

Y, et al: Osteocalcin signaling in myofibers is necessary and

sufficient for optimum adaptation to exercise. Cell Metab.

23:1078–1092. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|