Introduction

TAM receptors are a family of receptor tyrosine

kinases (RTKs) consisting of TYRO3, AXL, and MERTK that are

involved in cell survival, innate immunity, and immunosuppression

(1-6).

They are overexpressed in various types of tumor cells and immune

cells and activate several downstream signaling pathways such as

phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, extracellular signal-regulated

kinase, and nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated

B cells pathways. These downstream signaling pathways play a role

in promoting the growth and metastasis of tumor cells. Therefore,

activation of TAM receptors has shown the correlations with tumor

progression and poor prognosis in many cancers and is also

recognized as a mediator of acquired resistance to chemotherapy and

targeted therapy (1,2,7).

With regard to its immunomodulatory role, previous studies using a

syngeneic breast cancer model showed that conditional knockout of

MERTK caused an increase in tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and

inflammatory cytokines, showing that antitumor immunity could be

promoted. Numerous studies suggest that genetic modification or

pharmacologic inhibition of TAM receptors can act as therapeutic

targets to prevent tumor progression (8-12).

Several TAM tyrosine kinase inhibitors have been

developed, and some are undergoing clinical trials for cancer

treatment. The first-in-class AXL inhibitor R428, is being actively

investigated in several cancers including acute myeloid leukemia,

non-small cell lung cancer, and melanoma (13). Another MERTK inhibitor, UNC2025,

has a 40-fold higher inhibitory activity on MERTK than AXL. Mice

treated with UNC2025 show a significant reduction in tumor size and

increased survival compared with vehicle-treated mice in leukemia

models (14,15). However, other studies have

indicated that inhibition of a single TAM receptor can result in

drug resistance by inducing intrinsic and adaptive compensatory

mechanisms by activating other subunits. R428 showed an increase in

the expression of MERTK protein both in vitro and in

vivo in proportion to AXL inhibition, thereby reducing the

efficacy of the drug. In addition, the combined targeting of MERTK

and AXL showed a synergistic antitumor effect. Based on these

results, it has been hypothesized that targeting multiple members

of the TAM family would be a more effective cancer treatment than

single-target agents (16,17).

Pan-TAM inhibitors, such as BMS-777607 and

INCB081776, are under development for the treatment of cancer, but

it will take some time to achieve Food and Drug Administration

(FDA) approval. Despite the development of high-throughput

screening technologies, both a considerable cost and a long

development time are required for a drug to be approved and

released to the market. Above all, a significant number of novel

drug candidates have failed in preclinical or clinical trials for

various reasons, such as poor pharmacokinetics, unexplained

toxicity, and lack of efficacy. Therefore, drug repurposing, which

repurposes existing drugs into new treatments for intractable

diseases, is being proposed as one of the methods to overcome the

difficulties of drug development from novel compounds. Another

advantage of drug repurposing is that existing drugs have a proven

safety profile, so there are relatively few concerns about safety

issues. Recently, there have been many attempts in the drug

repurposing area that are expected to increase the success rate of

drug development using advanced in silico strategies

(18,19). Virtual screening using machine

learning and artificial intelligence (AI) provides insights into

finding new anticancer drug candidates from a large-scale

drug–target interaction (DTI) dataset, including BindingDB

(20), PubChem (21), and ChEMBL (22). Our group has developed a new deep

DTI prediction model called Molecule Transformer (MT)-DTI (23). In 2020, using MT-DTI, we predicted

that atazanavir and remdesivir were drugs that could inhibit

SARS-CoV-2(24). We then searched

for a drug among commercially available medications that could

simultaneously target AXL, MERTK, and TYRO3, using the MT-DTI

algorithm. As a result, fostamatinib, one of the spleen tyrosine

kinase (Syk) inhibitors, was predicted to inhibit TAM family

members effectively, and we further verified this result using

several cancer cell lines. Fostamatinib has been approved as a drug

for treating chronic immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) (25), but its inhibitory effect on TAM

kinases has not been reported. Here, we demonstrate that the

inhibitory effect on the TAM family is a unique function of

fostamatinib that is not observed with other Syk inhibitors. Our

results suggest not only the possibility of expanding the use of

fostamatinib by revealing a new function but also suggest the

possibility of identifying new drug mechanisms through AI.

Materials and methods

Prediction of bioactivity and binding

affinity for TAM kinases

The Deargen MT-DTI was used for the chemical

prediction to target triple TAM kinases simultaneously (23). Based on a manually curated public

database, the model was trained on bioactivity data

(IC50/EC50) and affinity data (Kd)

from the ChEMBL database (22),

Drug Target Common database (26),

and BindingDB database (27).

MT-DTI uses a GCN (28) algorithm

to extract molecular features and a ProtBert (29) algorithm to extract protein

features. With these features, our model was trained to predict

each parameter (IC50, EC50, and Kd)

simultaneously as multitask learning (30). It allowed prediction of the

IC50, EC50, and Kd values for one

drug-protein pair.

Connectivity map analysis

The Connectivity Map (CMap) CLUE web application

(https://clue.io) was used to assess the connectivity

of gene expression signatures between chemical and genetic

perturbations (31). The

Touchstone app of the CLUE database provided connectivity scores

ranging from -100 to +100, where positive scores corresponded to

the positive correlation of gene signatures between the two

perturbagens. Signatures with connectivity scores >40 (similar)

were further investigated in this study.

Cell culture and reagents

NCI-H1299 (H1299; human non-small cell lung cancer

cells), MDA-MB-231 (MB231; human breast adenocarcinoma cells), SCC4

(human tongue squamous cell carcinoma cells), and CAL27 (human

tongue squamous cell carcinoma cells) cells were obtained from the

Korean Cell Line Bank (Seoul, Korea) and American Type Culture

Collection (Manassas, VA, USA). H1299 and MB231 cells were

maintained in RPMI 1640 (HyClone, Logan, UT, USA), and SCC4 cells

were maintained in DMEM: F12 medium (Gibco, Waltham, MA, USA)

containing 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco) and 1% antibiotics at

37˚C in the presence of 5% CO2. Fostamatinib (#S2625),

BMS-777607 (#S1561), TAK-659 (#S8442), and MG-132 (#M7449) were

purchased from Selleckchem (Houston, TX, USA).

Cell viability assay

Cell viability was evaluated using a CellTiter

96® AQueous One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay

(Promega, San Luis Obispo, CA, USA). Cells were seeded at

3x103 cells/well in 96-well plates and then exposed to

fostamatinib, BMS-777607, or TAK-659 for 48 h. Assays were

performed by adding CellTiter 96® AQueous One Solution

Reagent directly to the wells, incubating them for 2 h, and then

measuring absorbance at 490 nm with a 96-well plate reader.

Western blotting and densitometric

analysis

Cells were lysed in RIPA buffer (Elpis Biotech,

Daejeon, Korea; #EBA-1149). Cell lysates were separated using

SDS-PAGE, transferred onto PVDF membranes, and then incubated with

primary antibodies followed by HRP-conjugated second antibodies

(Genetex, Irvine, CA, USA). Chemiluminescent signals were

visualized using the NEW Clarity ECL substrate (GE Healthcare,

Chicago, IL, USA). Antibodies for phospho-AXL (#5724), AXL (#8661),

and TYRO3 (#5585) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology

(Beverly, MA, USA). Antibodies for phospho-MERTK (#ab14921), MERTK

(#ab52968), phospho-Syk (#ab62338), Syk (#ab3993), and α-tubulin

(#ab4074) were purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, MA, USA). Western

blot quantification was performed using ImageJ software (version

1.51, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA). The

intensity of each protein band was quantified by measuring the

integrated density value using ImageJ software. Background

intensity was subtracted from each band intensity. The relative

protein expression was calculated by normalizing the target protein

intensity to that of α-tubulin from the same sample. Data from

three independent experiments were analyzed and presented as mean ±

standard deviation (SD).

Statistical analysis

All experiments were performed independently at

least three times. Results are presented as the mean ± SD.

Statistical significance was calculated by unpaired Student's t

test using GraphPad Prism (La Jolla, CA, USA).

Results

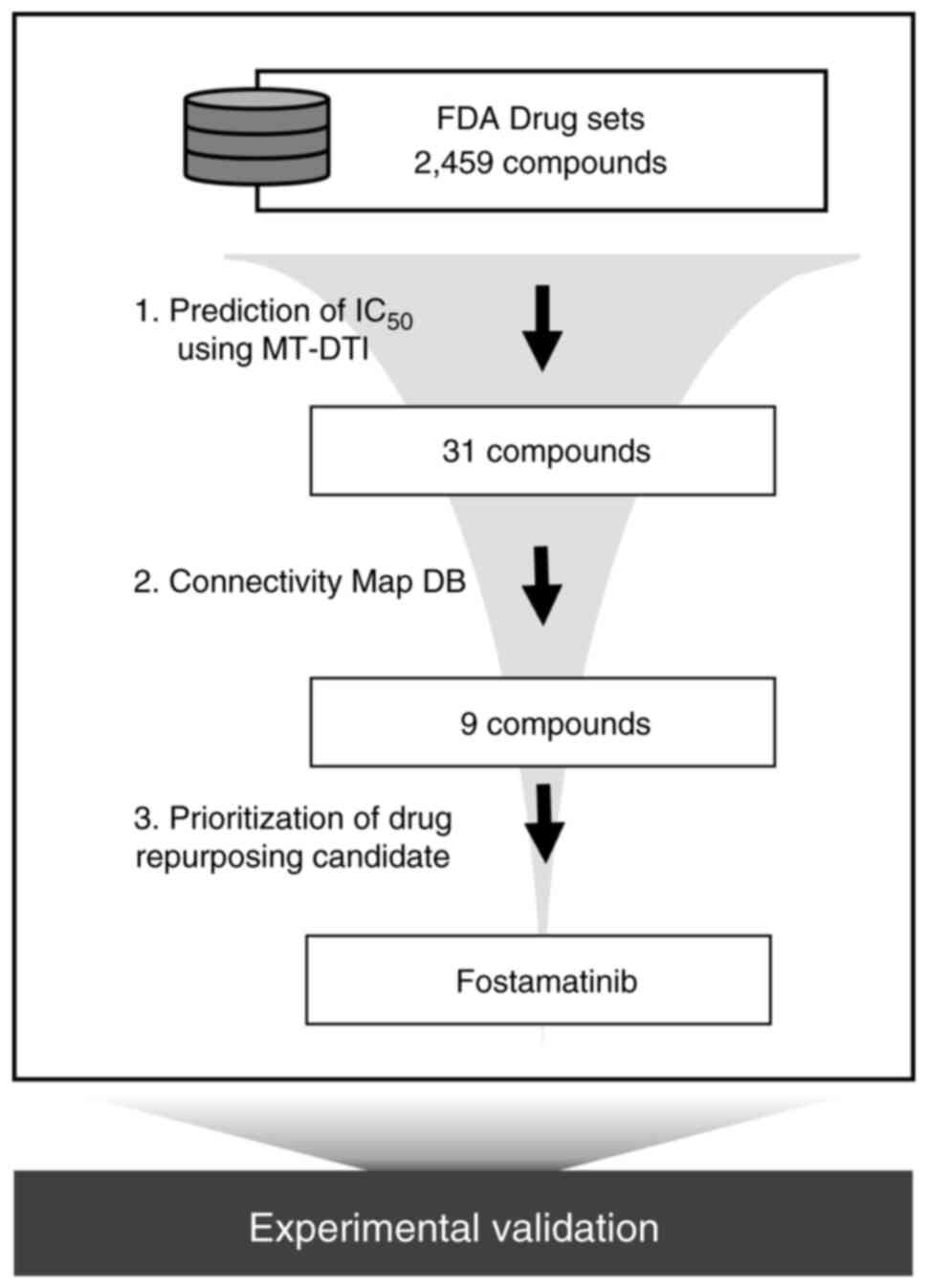

MT-DTI predicts commercially available

TAM kinase triple inhibitor candidates

To find an FDA-approved drug that can simultaneously

target triple TAM kinases, we performed in silico screening

using a deep learning-based model (23). By comparing the values predicted

through MT-DTI (predicted IC50 and predicted

EC50), drugs with an inhibitory effect twice that of the

activating effect were selected. Thirty-one drugs with an

IC50 of less than 1 µM in AXL, MERTK, and TYRO3 remained

out of 2,459 FDA drug sets (Table

SI). Of these 31 compounds, 21 were kinase inhibitors,

including multi-kinase inhibitors (e.g. ponatinib, cabozantinib,

lenvatinib), epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) inhibitors

(e.g. neratinib, osimertinib, afatinib), and MEK inhibitors (e.g.

selumetinib, trametinib, binimetinib, cobimetinib). In addition to

kinases, 10 drugs included androgen receptor antagonists (e.g.

apalutamide, enzalutamide), an antihypertensive (e.g. sitaxentan),

and antibiotics (e.g. ceforanide, ozenoxacin). To explore the

effects of each drug on TAM signaling, we analyzed the CMap

resource. The CMap database, developed by the Broad Institute, is a

collection of genome-wide gene expression data encompassing 1.5

million gene expression profiles from ~5,000 drug perturbagens and

~3,000 genetic perturbagens (32).

CLUE (https://clue.io/) is a cloud-based software

platform that provides a connectivity score between a query and a

perturbagen and allows users to access publicly available CMap data

(33). We compared the gene

signatures induced by 31 drug treatments with the gene signatures

by knock-down of AXL, MERTK, and TYRO3 using the Touchstone app in

the CLUE platform, which shows connectivity between perturbagens.

Gene signature scores for nine drugs among 31 compounds showed

>40 connectivity with gene knock-down signature scores (Table I). This suggests that the nine

drugs predicted by MT-DTI may act as potential inhibitors of TAM

kinases. According to the FDA labeling information, afatinib,

neratinib, axitinib, and bosutinib have already been approved for

the treatment of various types of tumors, suggesting there is a

limit to the concept of expansion of the drug indication through

repurposing. In addition, ruxolitinib resulted in an additive

effect by combined treatment with the AXL inhibitors, TP-0903 and

bemcentinib (34,35). Because ceforanide and zafirlukast

do not have a kinase inhibitor structure, the possibility of direct

action on the TAM family is relatively low. By contrast, because

fostamatinib, a Syk inhibitor, is already used as a treatment for

ITP, and there are no reports of the effect of fostamatinib on the

TAM family, we sought to verify the effect of fostamatinib on TAM

signaling. The workflow of the current study is illustrated in

Fig. 1.

| Table IList of drugs with connectivity

scores >40 after knock-down of TAM kinases. |

Table I

List of drugs with connectivity

scores >40 after knock-down of TAM kinases.

| | DTI scores

(predicted IC50, nM) | Connectivity

scores | |

|---|

| Drug | AXL | MERTK | TYRO3 | AXL | MERTK | TYRO3 | MoA | FDA-labeled

indication |

|---|

| Afatinib | 619.3 | 700.7 | 601.5 | 68.6 | - | 94.0 | EGFR inhibitor | Untreated,

metastatic non-small cell lung cancer |

| Neratinib | 156.3 | 349.1 | 158.8 | 67.6 | 45.6 | - | EGFR inhibitor |

HER2-overexpressed/amplified breast

cancer |

| Axitinib | 127.5 | 98.0 | 184.9 | 60.0 | 68.7 | 45.7 | VEGFR

inhibitor | Advanced renal cell

carcinoma |

| Ruxolitinib | 740.3 | 114.9 | 498.8 | 43.6 | 73.6 | 60.8 | JAK inhibitor | Intermediate or

high-risk myelofibrosis, including primary myelofibrosis |

| Bosutinib | 123.6 | 126.4 | 73.9 | 40.7 | 51.9 | 51.9 | Src/Abl

inhibitor | Chronic myelogenous

leukemia |

| Ceforanide | 358.0 | 553.9 | 516.9 | - | 51.9 | - | Antibacterial | Antibacterial |

| Zafirlukast | 643.8 | 623.7 | 748.4 | - | 47.9 | - | Leukotriene D4

receptor antagonist | Asthma |

| Selumetinib | 191.3 | 336.3 | 186.9 | - | - | 46.6 | MEK inhibitor | Neurofibromatosis

type 1 |

| Fostamatinib | 754.4 | 867.8 | 978.4 | - | - | 40.5 | Syk inhibitor | Immune

thrombocytopenia |

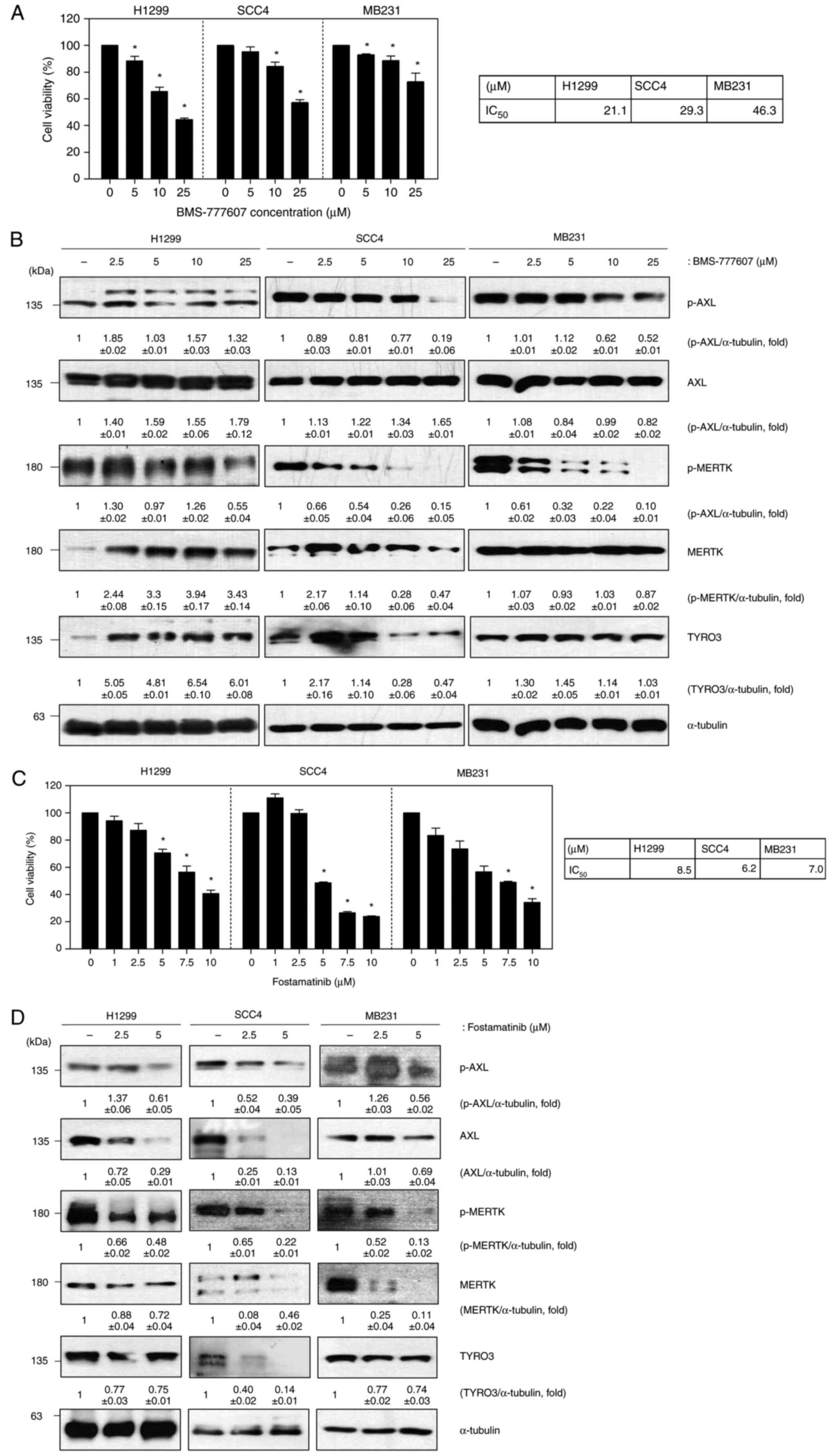

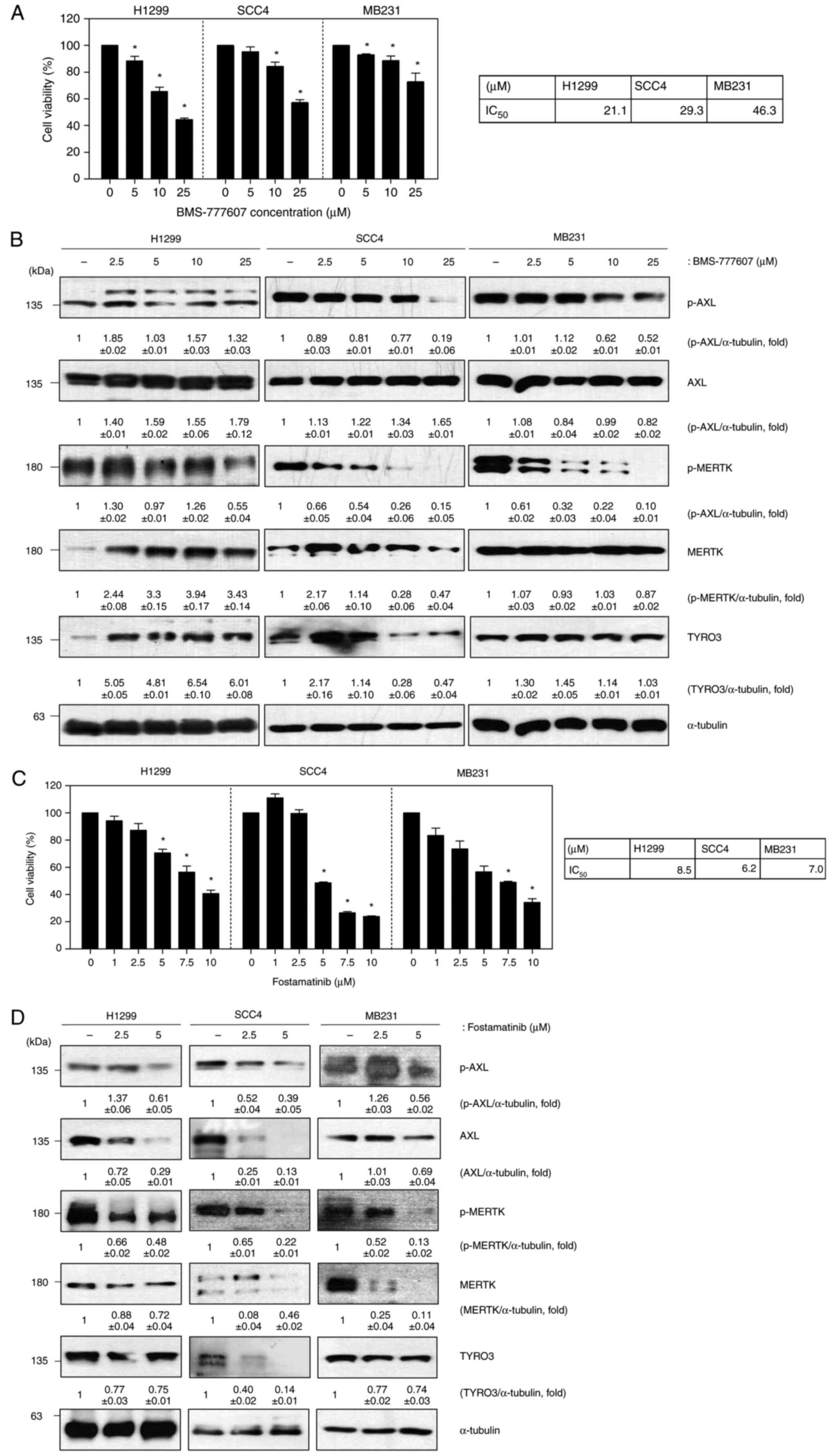

Fostamatinib suppresses cell

proliferation via inhibition of TAM kinases

The TAM family (AXL, MERTK, and TYRO3) are known to

play an important role in the development of various cancers. Based

on the results using MT-DTI, fostamatinib was predicted to be an

inhibitor of the TAM family. To determine the effect of the TAM

family on solid cancers, experiments were conducted using the

following cancer cell lines: H1299 cells (lung cancer); SCC4 cells

(head and neck squamous cell carcinoma); and MB231 cells (breast

cancer). We first evaluated the impact of BMS-777607, a known

pan-TAM inhibitor, on cell viability and TAM protein expression in

H1299, SCC4, and MB231 cells. BMS-777607 treatment resulted in a

dose-dependent decrease in cell viability across all three cell

lines (Fig. 2A). Western blot

analysis revealed that BMS-777607 treatment led to reduced

phosphorylation of both AXL and MERTK, indicating successful

inhibition of these kinases (Fig.

2B). While we observed a decrease in total TYRO3 protein

levels, we were unable to directly assess TYRO3 phosphorylation

status due to technical limitations of available antibodies. This

limitation stems from the high sequence homology between TYRO3

phosphorylation sites (Y681, Y685) and MERTK phosphorylation sites

(Y749, Y753), which causes commercially available phospho-specific

antibodies to cross-react with phosphorylated MERTK. Despite this

technical constraint, the reduction in cell viability and clear

effects on AXL and MERTK signaling demonstrate the effectiveness of

BMS-777607 as a TAM family inhibitor. Based on these results, the

same experiment was conducted using the cell lines listed above to

confirm the role of fostamatinib in solid cancers (Fig. 2C and D). Cell viability was decreased on

addition of increasing concentrations of fostamatinib, although

there was a difference in degree. Both the phosphorylated and total

forms of AXL and MERTK were decreased following fostamatinib

treatment. These results suggest that fostamatinib reduces cell

viability through the inhibition of TAM family proteins.

| Figure 2Fostamatinib suppresses cell

proliferation via inhibition of TAM kinases. (A) Cell viability

assay of H1299, SCC4 and MB231 cells after BMS-777607 treatment for

48 h; (B) Western blot of p-AXL, AXL, p-MERTK, MERTK and TYRO3 in

BMS-777607-treated cells (α-tubulin was used as a loading control);

(C) Cell viability assay of H1299, SCC4 and MB231 cells after

fostamatinib treatment for 48 h; (D) Western blot of p-AXL, AXL,

p-MERTK, MERTK and TYRO3 in fostamatinib-treated cells (α-tubulin

was used as a loading control). Data are representative of three

independent experiments and are presented as the mean ± SD. The

statistical significance was analyzed via Student's t-test;

*P<0.05 vs. untreated group. TAM, TYRO3, AXL, MERTK;

p-, phosphorylated. |

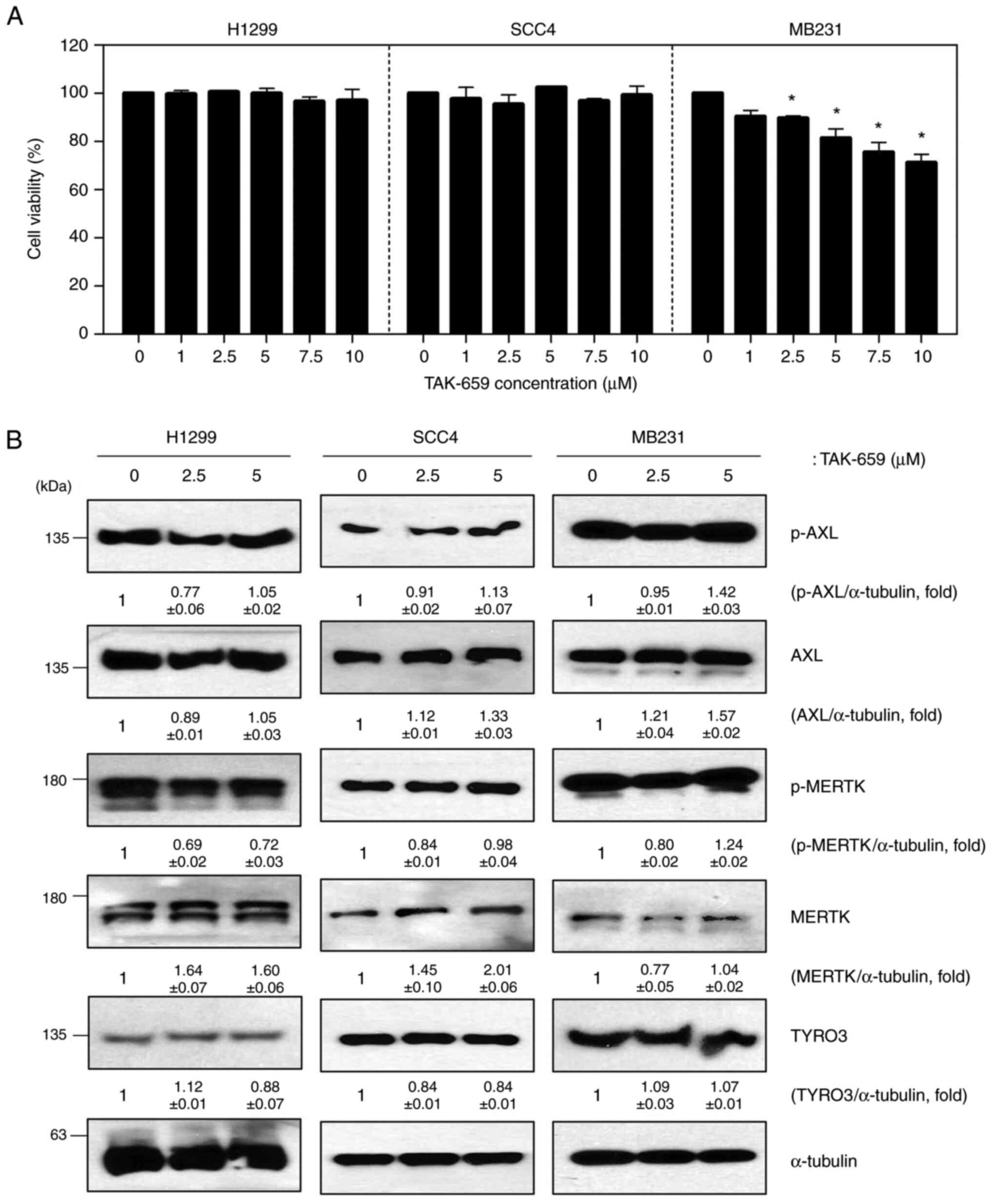

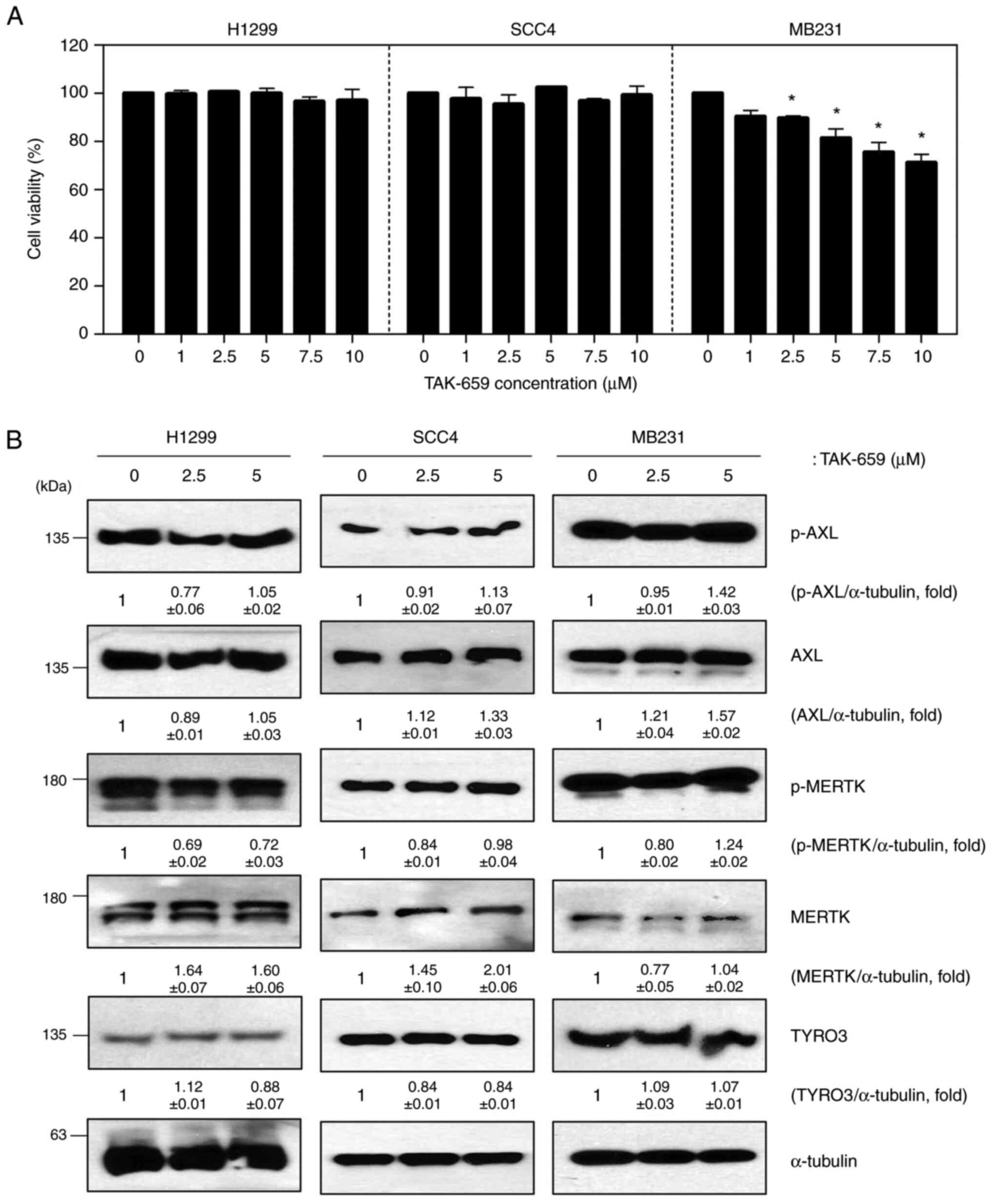

Other Syk inhibitors do not affect TAM

signaling

Fostamatinib was previously known as a Syk

inhibitor; therefore, we investigated whether other Syk inhibitors

had the same effect on TAM signaling. TAK-659 is a potent and

selective inhibitor of Syk. H1299, SCC4, and MB231 cells were

assessed for cell viability and TAM family protein levels after

TAK-659 treatment. H1299 and SCC4 cells did not show a change in

cell viability on exposure to TAK-659, but MB231 cell viability was

decreased slightly in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3A). Unlike the results after

fostamatinib treatment, TAM family protein expression levels did

not change after TAK-659 treatment in any of the cell lines tested

(Fig. 3B). Basal levels of Syk

protein expression were undetectable in H1299, SCC4, and MB231

cells, so we confirmed the effect of TAK-659 on TAM signaling using

CAL27 cells, a cell line with high Syk expression. TAK-659

significantly reduced the Syk protein levels in CAL27 cells,

whereas it did not affect the activity of AXL, MERTK, and TYRO3

(Fig. S1). These results suggest

that the effect of fostamatinib on TAM signaling is a unique

feature not found in other Syk inhibitors.

| Figure 3TAK-659, a Syk inhibitor, does not

affect TAM signaling. (A) Cell viability assay of H1299, SCC4 and

MB231 cells after TAK-659 treatment for 48 h; (B) Western blot of

p-AXL, AXL, p-MERTK, MERTK, and TYRO3 in TAK-659-treated cells

(α-tubulin was used as a loading control). Data are representative

of three independent experiments and presented as the mean ± SD.

The statistical significance was analyzed via Student's t-test.

*P<0.05 vs. untreated group. TAM, TYRO3, AXL, MERTK;

p-, phosphorylated; Syk, spleen tyrosine kinase. |

Discussion

Syk is a non-RTK and is known to play a crucial role

in autoimmune diseases and hematological malignancies (1). Syk mediates diverse biological

functions, including innate immune recognition, platelet

activation, cellular adhesion, osteoclast maturation, and vascular

development (1,2). Fostamatinib is a prodrug that is

converted to the active metabolite R406, which is a specific

inhibitor of Syk-dependent Fcγ receptors-mediated signaling in a

wide variety of tissues (36). In

phase III randomized double-blind placebo-controlled FIT1 and FIT2

trials, the efficacy and safety of fostamatinib were demonstrated

in patients with chronic ITP (37). Most adverse events were mild to

moderate, and manageable. Based on these results, in 2018, the FDA

approved fostamatinib for the treatment of chronic ITP in adults

who had insufficient response to prior therapy (36,37).

Although the clinical activity of fostamatinib has been reported in

some hematological and solid cancers (8,9), the

mechanism of action of fostamatinib, other than as a Syk kinase

inhibitor, has not yet been described, and it has not been approved

as an anticancer treatment. In this study, we discovered a novel

function of fostamatinib by employing a drug repositioning approach

via a machine learning algorithm.

An AI-driven drug repurposing approach, such as

MT-DTI, and computational pharmacogenomics using large-scale

perturbation databases, provide effective drug discovery and drug

repurposing/repositioning methodologies. As a result, we predicted

fostamatinib to be a drug that can inhibit TAM RTKs. The inhibitory

effect of fostamatinib on TAM kinases was verified with three

different types of cancer cell lines: lung cancer (H1299), head and

neck cancer (SCC4), and breast cancer (MB231). Fostamatinib

significantly decreased the expression levels of AXL, MERTK, and

TYRO3 equally in all three different types of cancer cell lines,

and reduced cell viability in a dose-dependent manner. For each

cell line, the IC50 values of fostamatinib were between

5 and 10 µM, and the cytotoxic effect of fostamatinib was superior

to that of the pan-TAM kinase inhibitor, BMS-777607. Regan-Fendt

et al (38) investigated

the possibility of dasatinib and fostamatinib as a treatment for

hepatocellular carcinoma using a transcriptomics-based drug

repurposing method. They showed that fostamatinib was able to

inhibit the growth of hepatocellular carcinoma cells with

IC50 values between 20 and 35 µM (38). In the experiment using another

well-known Syk inhibitor, the inhibitory effect on TAM kinases was

not shown, indicating it is a unique characteristic of

fostamatinib. Regarding the mechanism of action by which

fostamatinib inhibits TAM receptors, we investigated the potential

involvement of proteasomal degradation pathway. Our preliminary

experiment with the proteasome inhibitor, MG132, showed that MG132

pretreatment could attenuate the fostamatinib-induced decrease in

both phosphorylated and total protein levels of AXL and MERTK (data

not shown). While these initial findings suggested that

fostamatinib might promote TAM receptor degradation through a

proteasome-dependent mechanism, we faced significant technical

challenges in fully validating this hypothesis. Specifically, when

we attempted to optimize the MG132 and fostamatinib co-treatment

conditions using H1299 cells, the combination showed considerable

cellular toxicity that prevented us from obtaining reliable protein

expression data, particularly for TYRO3 blots. This technical

limitation, combined with the complex nature of receptor tyrosine

kinase regulation, suggests that additional studies using

alternative approaches would be needed to fully elucidate the

precise mechanism by which fostamatinib regulates TAM receptor

stability and function. Further investigation into the role of

fostamatinib as a potential molecular glue degrader (MGD) might

provide additional insights into its mechanism of action, as MGDs

destabilize target proteins by bridging them near E3 ubiquitin

ligases leading to polyubiquitylation and proteasomal degradation

of the target protein.

The TAM family of RTKs, including AXL, MERTK, and

TYRO3, is expressed in hematopoietic-derived cells that play

important roles in efferocytosis, and in the balancing of immune

responses and inflammation (10).

TAM kinases are also overexpressed in a variety of cancers that are

associated with chemoresistance, metastasis, and poor survival

outcomes (10,11). As well as the promotion of tumor

cell survival, proliferation, and invasion through activation of

downstream oncogenic signaling pathways, TAM receptors contribute

to tumor progression through an immunosuppressive tumor

microenvironment and tumor immune escape (12-14).

The key roles of TAM kinases as both oncogenic drivers and immune

system regulators have led to a growing interest in TAM receptor

inhibition, especially in the era of cancer immunotherapy. Of note,

the TAM receptors, in particular MERTK, have been shown to

upregulate the immune checkpoint molecule programmed cell death

ligand 1 (PD-L1) in tumor cells (39). These data suggest that TAM tyrosine

kinase inhibitors, in combination with immune checkpoint inhibitors

(ICIs), could enhance treatment efficacy. In support of this

hypothesis, Kasikara et al (40) reported that combined administration

of an ICI with the pan-TAM tyrosine kinase inhibitor BMS-777607

enhanced tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and T-cell-mediated

immunity, with improved antitumor activity in a murine model of

triple-negative breast cancer.

Several multitargeted tyrosine kinase inhibitors

show the inhibitory effects of TAM kinases, but few have been

specifically developed as TAM tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Several

TAM-selective inhibitors are currently in development, and

promising agents undergoing clinical trials include bemcentinib and

BMS-777607 (10,13). Bemcentinib (also known as BGB324 or

R428) is an orally available, selective inhibitor of AXL RTK that

showed antitumor effects in preclinical models with multiple cancer

cell lines (1,3,10).

Bemcentinib also demonstrated synergistic effects when combined

with ICIs, targeted therapies, and chemotherapeutic agents. As a

result, this drug is now in phase I/II clinical trials for a

variety of cancers, either alone or in combination with other

chemotherapy regimens including ICIs (7,10,39).

BMS-777607 was initially designed as a selective and orally

available MET kinase inhibitor, but it was found to have a role as

a potent pan-TAM inhibitor. BMS-777607 also demonstrated antitumor

activity in in vivo models of several cancers, and it is now

undergoing phase I/II clinical trials in patients with advanced

tumors (7,8,35,40).

Despite some of these promising drugs, there are still unmet needs

for more potent TAM kinase inhibitors with good safety profiles as

new anticancer agents. The first consideration is the relative

potency of the drug against the target. Previous studies indicate

that inhibiting only one of three TAM receptors may not be

effective because of the induction of compensatory activation of

the other subunits (11,16). In preclinical models, MERTK

inhibition alone was not sufficient to impact tumor growth, and

some small-molecule inhibitors of AXL or MERTK showed low

inhibitory potency against targets (7). In addition, some studies showed that

AXL expression was increased after treatment with bemcentinib

(41). This increase is caused by

the inhibition of ubiquitination and degradation of AXL receptors

by AXL phosphorylation blocking with small-molecule AXL inhibitors

(42). Further research is needed

to determine whether the paradoxical upregulation of AXL protein

could have the potential to reverse any desired effect of

treatment. Based on these previous data, we chose BMS-777607, the

same pan-TAM inhibitor, instead of bemcentinib, a selective AXL

inhibitor, to compare the efficacy of fostamatinib. Second, the

potential concern of TAM kinase inhibition is about safety issues.

TAM receptors are expressed in a wide range of tissues and have

crucial roles in the maintenance of an organ's normal functions.

Furthermore, because of their role in diminishing the innate immune

response, any sustained TAM kinase inhibition may lead to adverse

immune or inflammatory reactions, such as autoimmunity; thus,

careful monitoring is required (39).

Taken together, TAM family kinases are distinct

oncogenic drivers of novel anticancer targets through their

promotion of tumor cell survival, proliferation, invasion, and

chemoresistance, as well as their suppression of antitumor

immunity. This study suggests that fostamatinib has the potential

to be a novel anticancer agent through its inhibition of TAM

tyrosine kinase. In addition, its efficacy is expected to be better

than other previous TAM kinase inhibitors. An AI-driven drug-target

interaction prediction model, such as MT-DTI, can contribute to the

development of targeted therapy and be a powerful tool for drug

repurposing. Further validation is warranted in animal models and

clinical trials of patients with various types of cancer.

Additional investigation into the role of fostamatinib in immune

modulation in the tumor microenvironment, and in combination

therapy with ICI, may provide clinically useful information for a

new therapeutic strategy.

Supplementary Material

TAK-659 inhibits the Syk expression

but does not affect TAM signaling in CAL27 cells with high Syk

expression. Western blot of p-Syk, Syk, p-AXL, AXL, p-MERTK, MERTK,

and TYRO3 in TAK-659-treated cells (α-tubulin was used as a loading

control). TAM, TYRO3, AXL, MERTK; p-, phosphorylated.

MT-DTI prediction results of Food and

Drug Administration-approved drugs against the TAM receptor

kinases.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: This study was supported by a grant from the National

R&D Program for Cancer Control, Ministry of Health &

Welfare, Republic of Korea (grant no. 1720100). This study was also

supported by National Research Foundation of Korea grants funded by

the Korean government (MSIT) (grant nos. NRF-2020R1A5A2019210 and

NRF-2022R1A2C1011772).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

YC, HSW and YHK conceptualized the study. The

machine learning was performed by BL. BRB, HL, JHL, SK and SHC

performed experiments and analyzed data. YC, HL, HSW and YHK wrote

the original draft. YC, HSW and YHK reviewed and edited the

manuscript. HSW and YHK acquired funding. YC and HSW confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. All authors have read approved

the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

YC, BRB and BL were employed by the company Deargen

Inc., who developed the deep DTI prediction model called Molecule

Transformer (MT)-DTI employed in this study. The remaining authors

declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any

commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a

potential conflict of interest. All other authors do not have any

financial and non-financial conflict of interest and declare that

they have no competing interests.

References

|

1

|

Graham DK, DeRyckere D, Davies KD and Earp

HS: The TAM family: Phosphatidylserine sensing receptor tyrosine

kinases gone awry in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 14:769–785.

2014.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Wu G, Ma Z, Cheng Y, Hu W, Deng C, Jiang

S, Li T, Chen F and Yang Y: Targeting Gas6/TAM in cancer cells and

tumor microenvironment. Mol Cancer. 17(20)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Lemke G and Rothlin CV: Immunobiology of

the TAM receptors. Nat Rev Immunol. 8:327–336. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Cook RS, Jacobsen KM, Wofford AM,

DeRyckere D, Stanford J, Prieto AL, Redente E, Sandahl M, Hunter

DM, Strunk KE, et al: MerTK inhibition in tumor leukocytes

decreases tumor growth and metastasis. J Clin Invest.

123:3231–3242. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Paolino M, Choidas A, Wallner S, Pranjic

B, Uribesalgo I, Loeser S, Jamieson AM, Langdon WY, Ikeda F, Fededa

JP, et al: The E3 ligase Cbl-b and TAM receptors regulate cancer

metastasis via natural killer cells. Nature. 507:508–512.

2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Werfel TA and Cook RS: Efferocytosis in

the tumor microenvironment. Semin Immunopathol. 40:545–554.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Axelrod H and Pienta KJ: Axl as a mediator

of cellular growth and survival. Oncotarget. 5:8818–8852.

2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Holland SJ, Pan A, Franci C, Hu Y, Chang

B, Li W, Duan M, Torneros A, Yu J, Heckrodt TJ, et al: R428, a

selective small molecule inhibitor of Axl kinase, blocks tumor

spread and prolongs survival in models of metastatic breast cancer.

Cancer Res. 70:1544–1554. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Crittenden MR, Baird J, Friedman D, Savage

T, Uhde L, Alice A, Cottam B, Young K, Newell P, Nguyen C, et al:

Mertk on tumor macrophages is a therapeutic target to prevent tumor

recurrence following radiation therapy. Oncotarget. 7:78653–78666.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Ludwig KF, Du W, Sorrelle NB,

Wnuk-Lipinska K, Topalovski M, Toombs JE, Cruz VH, Yabuuchi S,

Rajeshkumar NV, Maitra A, et al: Small-molecule inhibition of Axl

targets tumor immune suppression and enhances chemotherapy in

pancreatic cancer. Cancer Res. 78:246–255. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Kim JE, Kim Y, Li G, Kim ST, Kim K, Park

SH, Park JO, Park YS, Lim HY, Lee H, et al: MerTK inhibition by

RXDX-106 in MerTK activated gastric cancer cell lines. Oncotarget.

8:105727–105734. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Cummings CT, Zhang W, Davies KD,

Kirkpatrick GD, Zhang D, DeRyckere D, Wang X, Frye SV, Earp HS and

Graham DK: Small molecule inhibition of MERTK is efficacious in

non-small cell lung cancer models independent of driver oncogene

status. Mol Cancer Ther. 14:2014–2022. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Gay CM, Balaji K and Byers LA: Giving AXL

the axe: Targeting AXL in human malignancy. Br J Cancer.

116:415–423. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Zhang W, DeRyckere D, Hunter D, Liu J,

Stashko MA, Minson KA, Cummings CT, Lee M, Glaros TG, Newton DL, et

al: UNC2025, a potent and orally bioavailable MER/FLT3 dual

inhibitor. J Med Chem. 57:7031–7041. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

DeRyckere D, Lee-Sherick AB, Huey MG, Hill

AA, Tyner JW, Jacobsen KM, Page LS, Kirkpatrick GG, Eryildiz F,

Montgomery SA, et al: UNC2025, a MERTK small-molecule inhibitor, is

therapeutically effective alone and in combination with

methotrexate in leukemia models. Clin Cancer Res. 23:1481–1492.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

McDaniel NK, Cummings CT, Iida M, Hülse J,

Pearson HE, Vasileiadi E, Parker RE, Orbuch RA, Ondracek OJ, Welke

NB, et al: MERTK mediates intrinsic and adaptive resistance to

AXL-targeting agents. Mol Cancer Ther. 17:2297–2308.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Rios-Doria J, Favata M, Lasky K, Feldman

P, Lo Y, Yang G, Stevens C, Wen X, Sehra S, Katiyar K, et al: A

potent and selective dual inhibitor of AXL and MERTK possesses both

immunomodulatory and tumor-targeted activity. Front Oncol.

10(598477)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Ekins S, Puhl AC, Zorn KM, Lane TR, Russo

DP, Klein JJ, Hickey AJ and Clark AM: Exploiting machine learning

for end-to-end drug discovery and development. Nat Mater.

18:435–441. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Issa NT, Stathias V, Schurer S and

Dakshanamurthy S: Machine and deep learning approaches for cancer

drug repurposing. Semin Cancer Biol. 68:132–142. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Gilson MK, Liu T, Baitaluk M, Nicola G,

Hwang L and Chong J: BindingDB in 2015: A public database for

medicinal chemistry, computational chemistry and systems

pharmacology. Nucleic Acids Res. 44 (D1):D1045–D1053.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Kim S, Chen J, Cheng T, Gindulyte A, He J,

He S, Li Q, Shoemaker BA, Thiessen PA, Yu B, et al: PubChem 2019

update: Improved access to chemical data. Nucleic Acids Res. 47

(D1):D1102–D1109. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Gaulton A, Bellis LJ, Bento AP, Chambers

J, Davies M, Hersey A, Light Y, McGlinchey S, Michalovich D,

Al-Lazikani B and Overington JP: ChEMBL: A large-scale bioactivity

database for drug discovery. Nucleic Acids Res. 40 (Database

Issue):D1100–D1107. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Beck BR, Shin B, Choi Y, Park S and Kang

K: Predicting commercially available antiviral drugs that may act

on the novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) through a drug-target

interaction deep learning model. Comput Struct Biotechnol J.

18:784–790. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Choi Y, Shin B, Kang K, Park S and Beck

BR: Target-centered drug repurposing predictions of human

angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) and transmembrane protease

serine subtype 2 (TMPRSS2) interacting approved drugs for

coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) treatment through a drug-target

interaction deep learning model. Viruses. 12(1325)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Connell NT and Berliner N: Fostamatinib

for the treatment of chronic immune thrombocytopenia. Blood.

133:2027–2030. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Tanoli Z, Alam Z, Vähä-Koskela M,

Ravikumar B, Malyutina A, Jaiswal A, Tang J, Wennerberg K and

Aittokallio T: Drug target commons 2.0: A community platform for

systematic analysis of drug-target interaction profiles. Database

(Oxford). 2018:1–13. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Liu T, Lin Y, Wen X, Jorissen RN and

Gilson MK: BindingDB: A web-accessible database of experimentally

determined protein-ligand binding affinities. Nucleic Acids Res. 35

(Database Issue):D198–D201. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Zhou J, Cui G, Hu S, Zhang Z, Yang C, Liu

Z, Wang L, Li C and Sun M: Graph neural networks: A review of

methods and applications. AI Open. 1:57–81. 2020.

|

|

29

|

Elnaggar A, Heinzinger M, Dallago C,

Rihawi G, Wang Y, Jones L, Gibbs T, Feher T, Angerer C, Steinegger

M, et al: ProtTrans: Towards cracking the language of life's code

through self-supervised deep learning and high performance

computing. arXiv preprint arXiv: 200706225, 2020.

|

|

30

|

Ruder S: An overview of multi-task

learning in deep neural networks. arXiv preprint arXiv: 170605098,

2017.

|

|

31

|

Duan Q, Flynn C, Niepel M, Hafner M,

Muhlich JL, Fernandez NF, Rouillard AD, Tan CM, Chen EY, Golub TR,

et al: LINCS canvas browser: Interactive web app to query, browse

and interrogate LINCS L1000 gene expression signatures. Nucleic

Acids Res. 42 (Web Server Issue):W449–W460. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Lamb J, Crawford ED, Peck D, Modell JW,

Blat IC, Wrobel MJ, Lerner J, Brunet JP, Subramanian A, Ross KN, et

al: The connectivity map: Using gene-expression signatures to

connect small molecules, genes, and disease. Science.

313:1929–1935. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Subramanian A, Narayan R, Corsello SM,

Peck DD, Natoli TE, Lu X, Gould J, Davis JF, Tubelli AA, Asiedu JK,

et al: A next generation connectivity map: L1000 platform and the

first 1,000,000 profiles. Cell. 171:1437–1452.e17. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Beitzen-Heineke A, Berenbrok N,

Waizenegger J, Paesler S, Gensch V, Udonta F, Vargas Delgado ME,

Engelmann J, Hoffmann F, Schafhausen P, et al: AXL inhibition

represents a novel therapeutic approach in BCR-ABL negative

myeloproliferative neoplasms. Hemasphere. 5(e630)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Yan D, Earp HS, DeRyckere D and Graham DK:

Targeting MERTK and AXL in EGFR mutant non-small cell lung cancer.

Cancers (Basel). 13(5639)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Markham A: Fostamatinib: First global

approval. Drugs. 78:959–963. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Bussel J, Arnold DM, Grossbard E, Mayer J,

Treliński J, Homenda W, Hellmann A, Windyga J, Sivcheva L,

Khalafallah AA, et al: Fostamatinib for the treatment of adult

persistent and chronic immune thrombocytopenia: Results of two

phase 3, randomized, placebo-controlled trials. Am J Hematol.

93:921–930. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Regan-Fendt K, Li D, Reyes R, Yu L, Wani

NA, Hu P, Jacob ST, Ghoshal K, Payne PRO and Motiwala T:

Transcriptomics-based drug repurposing approach identifies novel

drugs against sorafenib-resistant hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancers

(Basel). 12(2730)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Aehnlich P, Powell RM, Peeters MJW,

Rahbech A and Thor Straten P: TAM receptor inhibition-implications

for cancer and the immune system. Cancers (Basel).

13(1195)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Kasikara C, Davra V, Calianese D, Geng K,

Spires TE, Quigley M, Wichroski M, Sriram G, Suarez-Lopez L, Yaffe

MB, et al: Pan-TAM tyrosine kinase inhibitor BMS-777607 enhances

anti-PD-1 mAb efficacy in a murine model of triple-negative breast

cancer. Cancer Res. 79:2669–2683. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Chen F, Song Q and Yu Q: Axl inhibitor

R428 induces apoptosis of cancer cells by blocking lysosomal

acidification and recycling independent of Axl inhibition. Am J

Cancer Res. 8:1466–1482. 2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Lauter M, Weber A and Torka R: Targeting

of the AXL receptor tyrosine kinase by small molecule inhibitor

leads to AXL cell surface accumulation by impairing the

ubiquitin-dependent receptor degradation. Cell Commun Signal.

17(59)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|