Introduction

Pituitary abscesses are extremely rare in clinical

practice, accounting for ~1% of all pituitary lesions (1). However, as a central nervous system

infection, they pose a risk of disability and mortality (2). Pituitary abscesses are classified as

primary or secondary. Primary pituitary abscesses are more common,

accounting for ~67% of cases, and typically result from

hematogenous bacterial spread to an otherwise normal pituitary

gland. By contrast, secondary pituitary abscesses, which arise from

pre-existing sellar lesions such as pituitary adenomas, Rathke's

cleft cysts or craniopharyngiomas, represent 33% of cases (3). The pathogenetic mechanisms leading to

secondary pituitary abscesses include anatomical distortion,

impaired circulation and altered immune status, which predispose

patients to infection (4). The

clinical presentation of pituitary abscesses is variable, with

symptoms including hormonal imbalances, diabetes insipidus and

visual disturbances, often due to mass effects. When the pituitary

gland is infected, hypopituitarism may occur, resulting in

deficiencies in one or more pituitary hormones. This dysfunction

can cause severe endocrine disorders, such as diabetes insipidus

(due to antidiuretic hormone deficiency), hypothyroidism (due to

thyroid-stimulating hormone deficiency) and adrenal insufficiency

(due to adrenocorticotropic hormone deficiency) (5). These hormonal imbalances can lead to

systemic complications, including electrolyte disturbances,

metabolic abnormalities and cardiovascular instability, emphasizing

the potentially dangerous nature of pituitary abscesses (6). MRI findings typically reveal a cystic

lesion with ring enhancement, which is hyperintense on T2-weighted

images and hypointense on T1-weighted images. However, despite

advancements in imaging technology, the preoperative diagnosis of

pituitary abscesses remains challenging, particularly in cases

associated with pre-existing sellar lesions such as

craniopharyngiomas. Early surgical drainage combined with

antibiotic therapy remains the cornerstone of treatment, but

outcomes depend heavily on a timely diagnosis and the extent of the

underlying lesion. Delayed treatment may result in irreversible

hormonal deficiencies and increased morbidity (7).

The difficulty in diagnosing secondary pituitary

abscesses, particularly those associated with craniopharyngiomas,

necessitates a broader understanding of their pathophysiology and a

more systematic approach to diagnosis and management. Early

recognition and intervention are crucial for reducing the high

prevalence of pituitary dysfunction in patients treated for these

abscesses and for improving overall prognosis. The present case

report highlights the clinical features and management of a

secondary pituitary abscess arising from a craniopharyngioma and

provides a literature review of similar cases.

Case report

A 59-year-old man presented to Beijing Tiantan

Hospital, Capital Medical University (Beijing, China) in August

2023 with complaints of progressive visual deterioration in both

eyes, along with visual field constriction, dizziness, headaches,

nausea, vomiting and an intermittent fever with a peak temperature

of 39.2˚C. The visual impairment had worsened over several months,

with difficulty recognizing faces and reading, particularly in dim

lighting. The patient reported a gradual narrowing of the

peripheral vision, which was later confirmed as bitemporal

hemianopsia, a hallmark of sellar region pathology. The patient

also described intermittent diplopia and a sensation of 'pressure'

behind the eyes. In addition, a single episode of transient loss of

consciousness accompanied by convulsions lasting about 1 min was

experienced. Neurologically, the patient exhibited mild confusion,

generalized fatigue and occasional dizziness upon standing, raising

suspicion of an underlying endocrine disturbance. The patient did

not have a family history of cancer.

An MRI scan performed at a local hospital revealed a

cystic lesion with rim enhancement in the sellar and suprasellar

regions, measuring ~18x22x20 mm, with mass effect on the optic

chiasm. The lesion exhibited heterogeneous hyperintensity on

T2-weighted images and hypointensity on T1-weighted images,

suggesting a pituitary abscess (data not shown). The patient was

treated with intravenous cephalosporin antibiotics; however, the

symptoms persisted, and the patient was subsequently transferred to

the Department of Neuroinfections and Immunology at Beijing Tiantan

Hospital (Beijing, China).

Neurological examination upon admission, 5 days

after the patient initially presented to the local hospital,

revealed bilateral visual decline with confirmed bitemporal

hemianopsia. The visual acuity was significantly reduced, measured

at 0.2 (right eye) and 0.1 (left eye) on the Snellen chart. Further

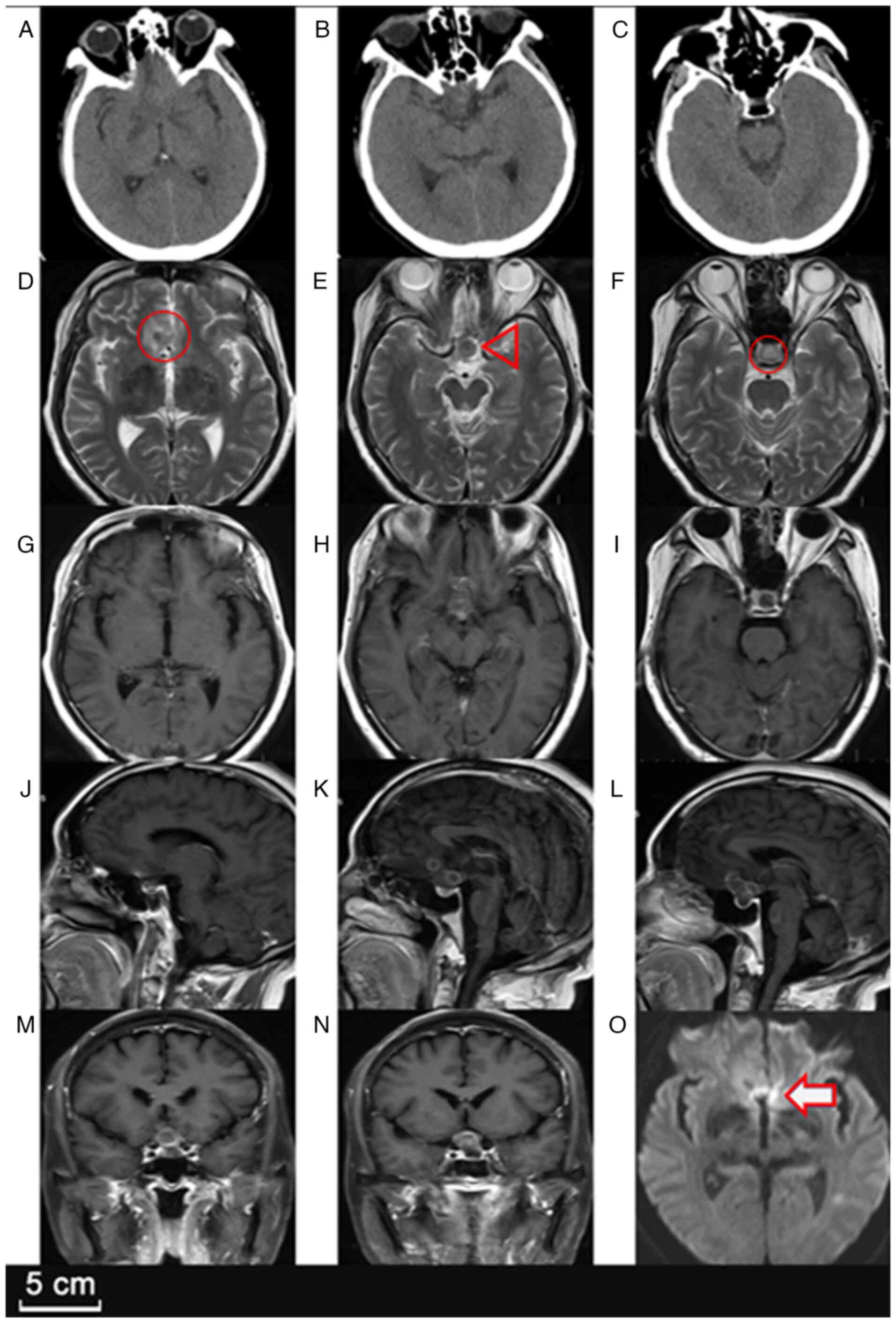

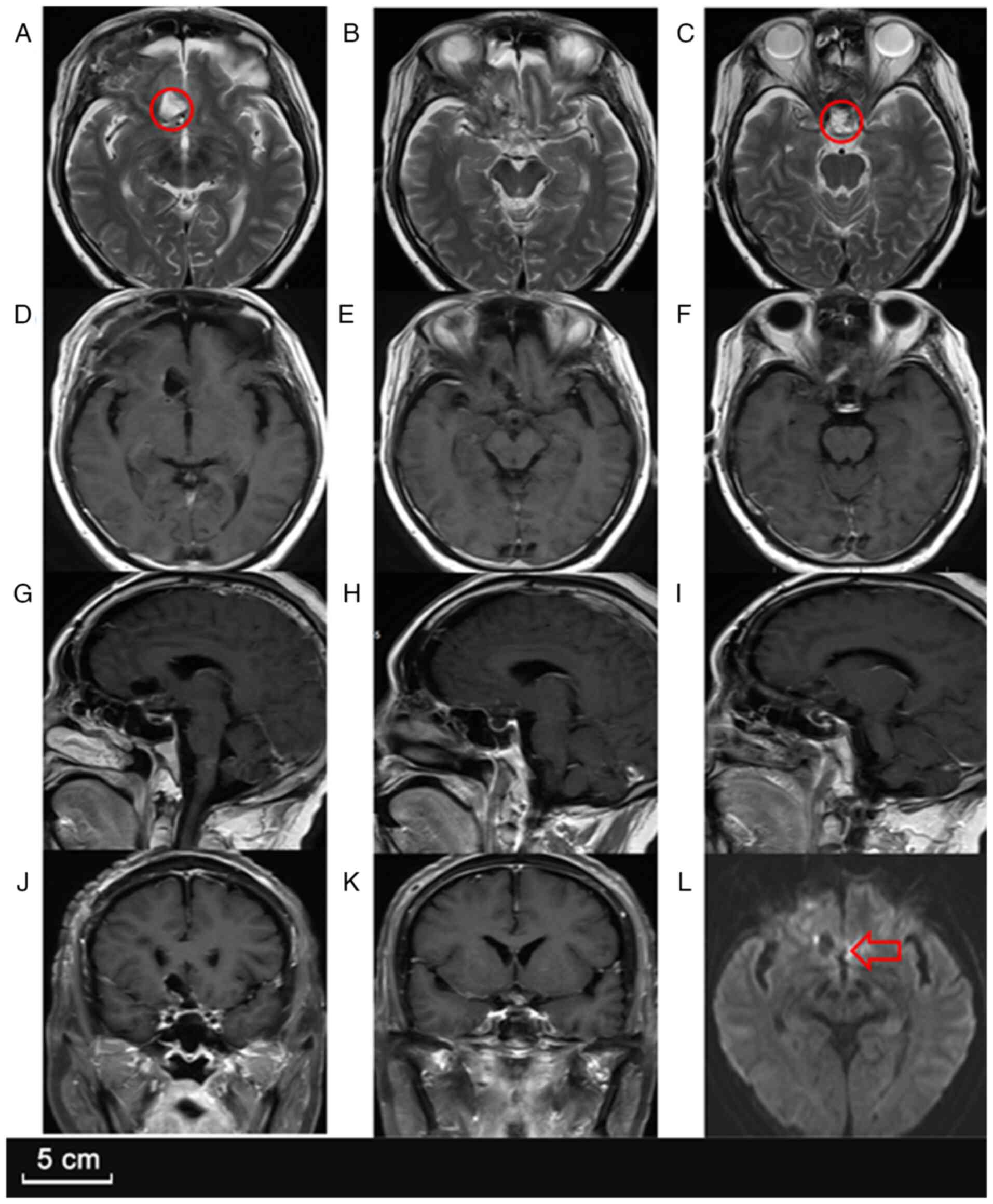

imaging studies, including a head CT scan and contrast-enhanced MRI

(Fig. 1), indicated a

well-defined, multilobulated, ring-enhancing lesion in the sellar

region, extending into the suprasellar cistern. Additionally,

another small ring-enhancing lesion was noted in the right frontal

lobe, suggesting the possibility of multifocal abscess formation.

The sellar lesion showed mild perifocal edema, with compression of

the optic chiasm and partial displacement of the third ventricle,

raising concern for obstructive hydrocephalus.

A comprehensive hormonal evaluation of the pituitary

gland (Table I) revealed

significant suppression of the thyroid and growth hormone axes,

with a free thyroxine level of 7 pmol/l (reference range,

7.64-16.03 pmol/l) and an insulin-like growth factor 1 level of

33.7 ng/ml (reference range, 45-210 ng/ml). Additionally, the

patient exhibited symptoms of adrenal insufficiency, including

postural dizziness and chronic fatigue, with a morning cortisol

level of 3.1 µg/dl (reference range, 5-25 µg/dl), necessitating

corticosteroid replacement. Oral prednisone acetate tablets were

administered at a daily dose of 10 mg from the time of diagnosis of

adrenocortical insufficiency until postoperative hormone

replacement therapy. The dosage was gradually tapered and

eventually discontinued after follow-up revealed progressive

recovery of pituitary function. Prolactin was elevated to 54.4

ng/ml (reference range, 2.50-17.00 ng/ml) due to the pituitary

stalk effect. Urine tests revealed low urine specific gravity

(1.002) and a marked increase in 24-h urinary sodium excretion

(609.96 mmol/day), supporting a diagnosis of central diabetes

insipidus. The patient underwent a lumbar puncture, and the

cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis revealed a markedly elevated

white blood cell count of 1,301/µl (reference range, 0-8/µl), with

70.4% polymorphonuclear cells, consistent with a bacterial

infection. CSF protein was elevated at 251.25 mg/dl (reference

range, 15.00-45.00 mg/dl) and lactate level was increased to 3.8

mmol/l (reference range, 1.1-2.4 mmol/l), suggesting an ongoing

central nervous system (CNS) infection.

| Table IPatient's laboratory results and

normal ranges. |

Table I

Patient's laboratory results and

normal ranges.

| Test | Pre-surgery

result | Post-surgery result

(1 week after surgery) | Normal range |

|---|

| ACTH, pg/ml | 5.34 | 5.07 | 0-46 |

| IGF-1, ng/ml | 33.7 | 72.4 | 45-210 |

| Free thyroxine,

pmol/l | 7 | 12.1 | 7.64-16.03 |

| TSH, µIU/ml | 1.62 | <0.005 | 0.49-4.91 |

| FSH, mIU/ml | 1.89 | <0.1 | 0.7-11.1 |

| LH, mIU/ml | <0.1 | <0.1 | 0.8-7.6 |

| Progesterone,

ng/ml | <0.2 | <0.2 | 0.27-0.90 |

| Testosterone,

ng/ml | <0.2 | <0.2 | 2.1-7.5 (male

>50 years) |

| Estradiol,

pg/ml | <11.8 | <11.8 | 0-39.8 (male) |

| Prolactin,

ng/ml | 54.4 | <0.5 | 2.5-17 |

| Urine specific

gravity | 1.002 | 1.002 | 1.003-1.030 |

| 24-h urine sodium

content, mmol/24 h | 609.96 | 458.65 | 40-220 |

Initial treatment and disease

progression

Empirical broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy with

meropenem (1,000 mg, bid, iv, one month) and vancomycin (500 mg,

every day, intravenously for 1 month) was initiated to control the

CNS infection, along with oral levetiracetam (500 mg, twice per

day, orally; administered long-term and continued postoperatively

for prophylactic purposes) for seizure control and desmopressin

(0.1 mg, three times a day, orally; administered long-term until

the symptoms of diabetes insipidus gradually resolved after

surgery) for central diabetes insipidus. The patient's fever and

systemic inflammatory response improved, and the patient's body

temperature returned to normal. However, despite a prolonged course

of intravenous antibiotics, the visual deficits and endocrine

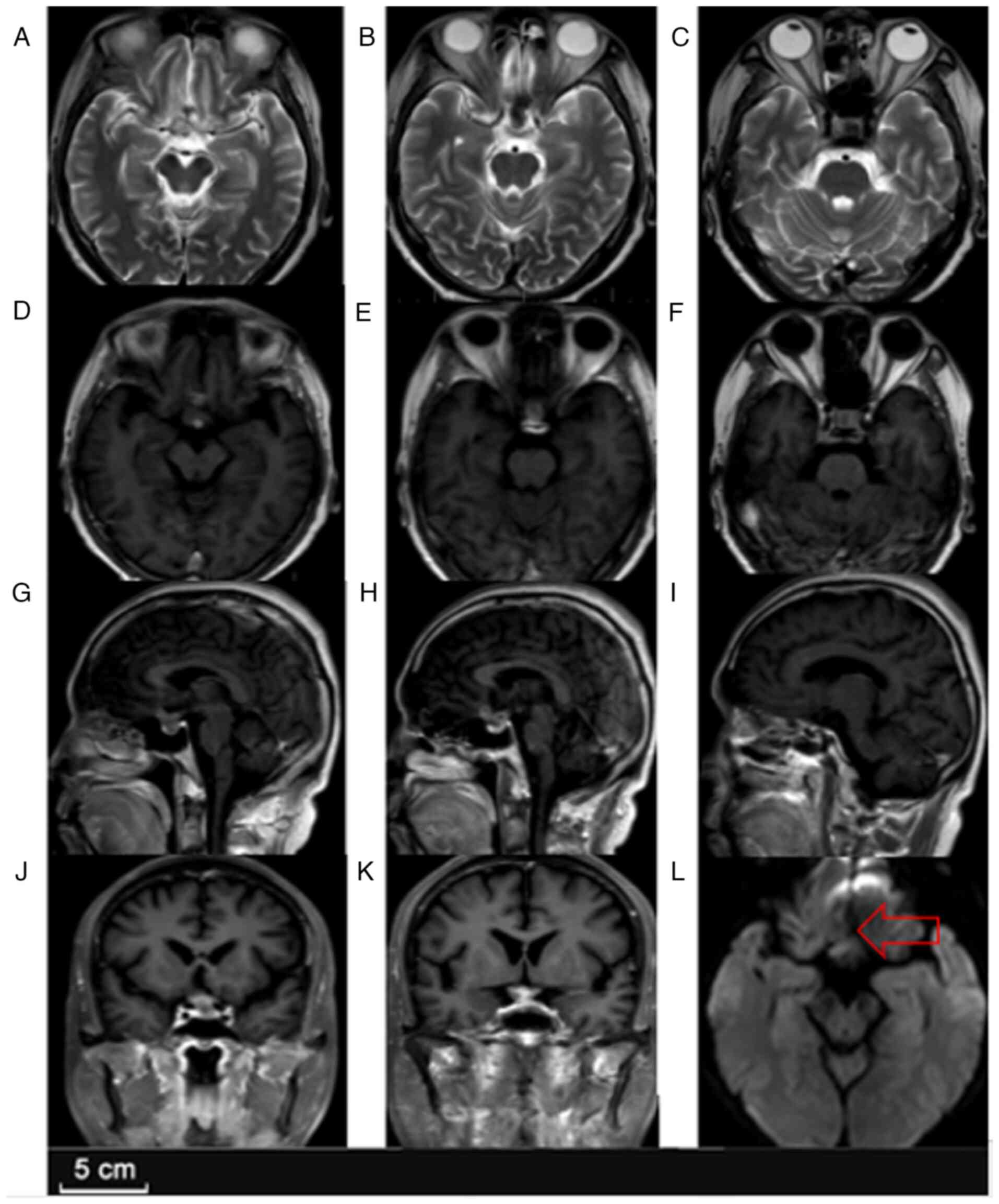

dysfunction persisted. Follow-up MRI (Fig. 2) at discharge in January 2024

showed a slight reduction in lesion size but persistent enhancement

and perifocal edema, indicating that infection had not been

completely eradicated.

After discharge, the patient continued antibiotic

treatment at a community hospital. However, in March 2024, the

fever, dizziness and lethargy recurred, and the patient again had a

seizure episode characterized by jaw clenching, loss of

consciousness and generalized tonic-clonic movements lasting ~1

min.

Surgical intervention

The patient was readmitted in April 2024 to

Neurosurgical Oncology Unit 7 at Beijing Tiantan Hospital. A

physical examination upon admission revealed that the patient was

conscious but lethargic, with further decreased visual acuity (0.1

in both eyes), constricted visual fields and persistent endocrine

symptoms. Neck stiffness was present, raising suspicion of

worsening intracranial infection.

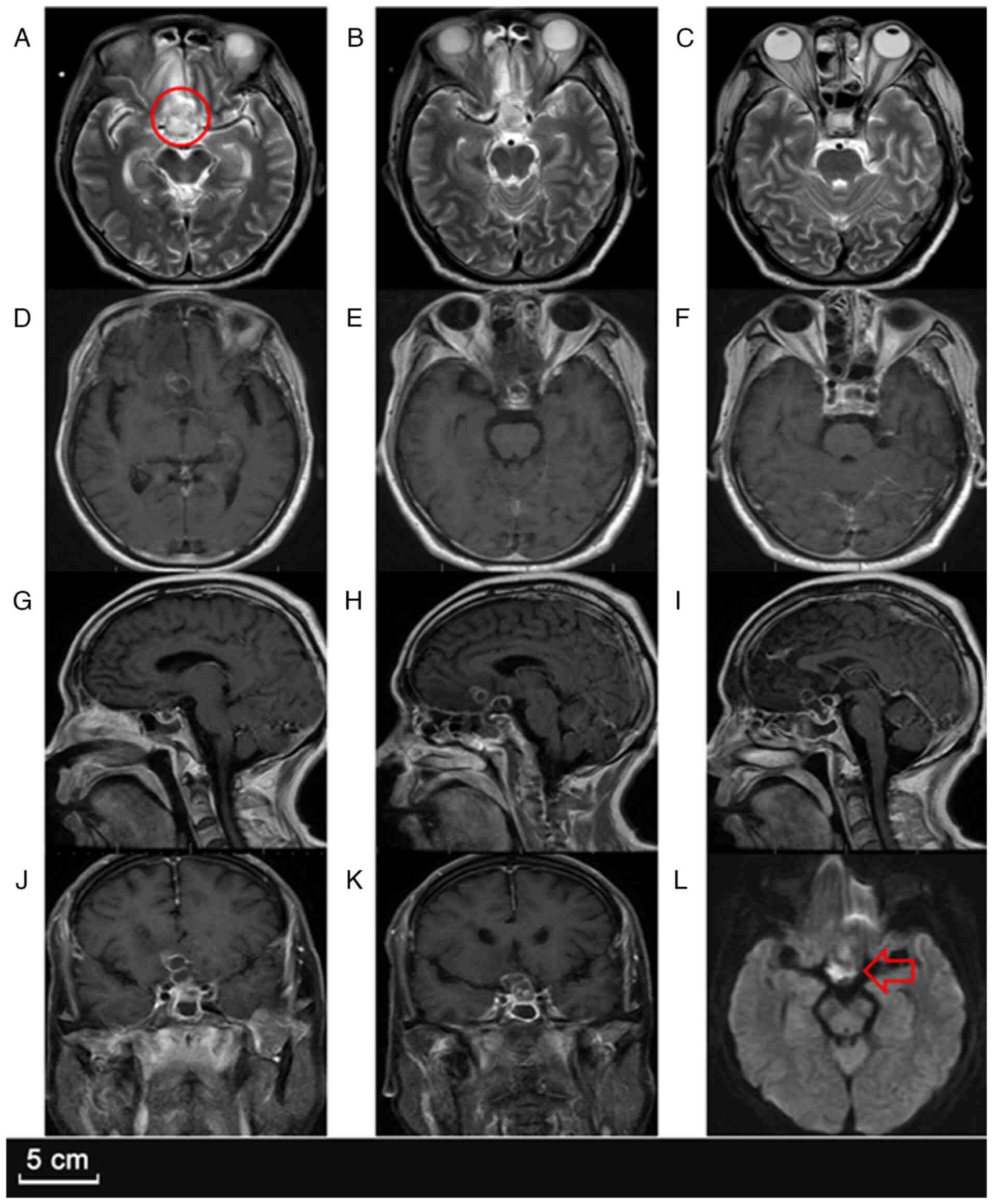

A follow-up MRI (Fig.

3) demonstrated marked enlargement of the sellar lesion, which

had increased to 26x32x28 mm, with intensified ring enhancement,

worsening perifocal edema and an increased mass effect on the optic

chiasm. The right frontal lesion had also slightly enlarged,

suggesting ongoing infection despite antibiotic therapy. Given the

failure of conservative management, the neuro-oncology team decided

to proceed with a craniotomy for lesion resection and thorough

abscess drainage.

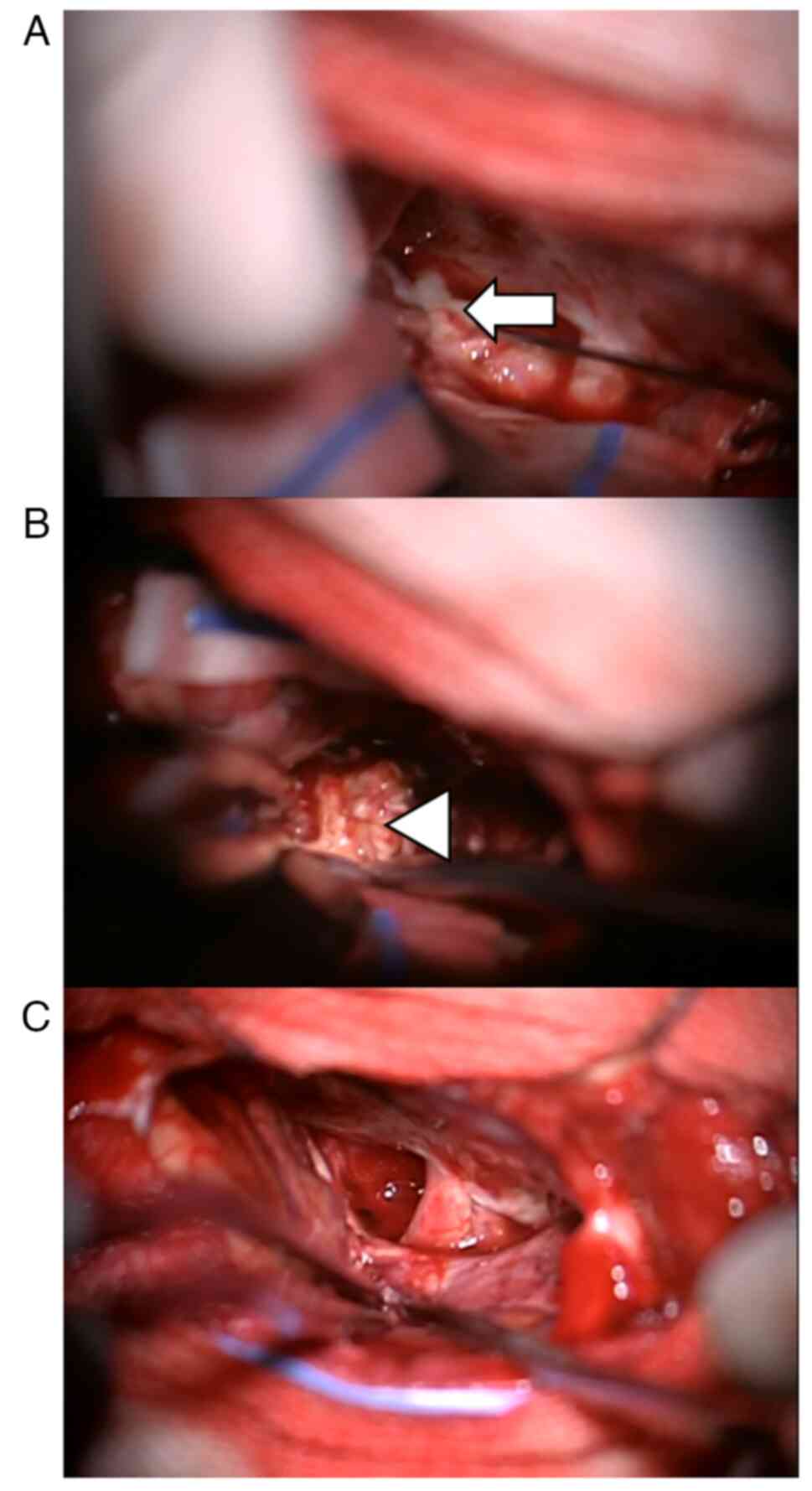

The surgery was performed via a right frontotemporal

approach, revealing a grayish-white cystic-solid lesion extending

from the right frontal base to the sellar region. Intraoperatively,

thick, white, purulent fluid was aspirated from the cystic

component, confirming an abscess (Fig.

4). The cystic cavity was irrigated with antibiotic solution

and the surrounding solid lesion was meticulously excised. The

excised specimen measured ~20x28x22 mm.

Postoperative findings and

follow-up

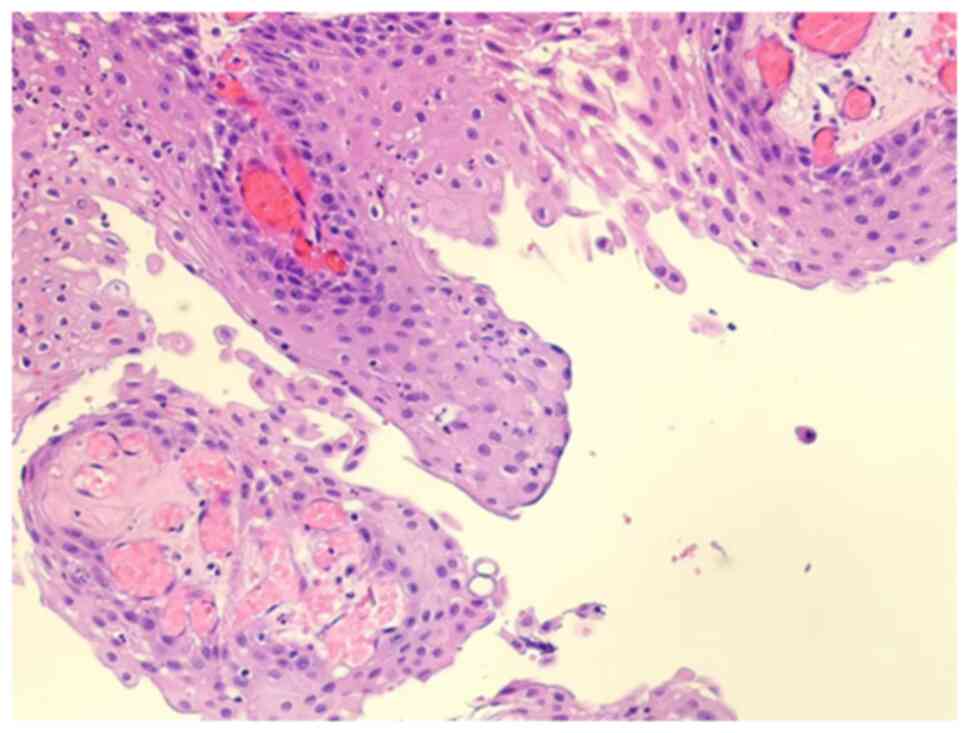

Tissue samples from the wall of the sellar abscess

were fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin at room temperature

(~22˚C) for 24 h. The fixed tissues were then processed and

embedded in paraffin. Sections were cut at a thickness of 4 µm

using a microtome. Routine hematoxylin and eosin staining was

performed at room temperature, with hematoxylin staining for 5 min

and eosin for 2 min. The stained slides were examined using a light

microscope (Olympus BX53; Olympus Corporation). Images were

captured at x200 magnification. A targeted next-generation

sequencing approach (BGI Genomics Co., Ltd.) was used to detect a

BRAFV600E mutation in the tumor sample. Genomic DNA was extracted

from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tumor tissue using

the QIAamp DNA FFPE Tissue Kit (cat. no. 56404; Qiagen, Inc.)

according to the manufacturer's protocol. DNA quantity and quality

were assessed using a Qubit 4.0 Fluorometer (Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) and an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent

Technologies, Inc.). Library preparation was conducted using the

MGIEasy Universal DNA Library Prep Set (cat. no. 1000006985; BGI

Genomics Co., Ltd.) following the manufacturer's instructions.

Sequencing was performed on the MGISEQ-2000 platform with

paired-end 150 base pair reads (PE150). The sequencing kit was the

MGISEQ-2000RS High-throughput Sequencing Set (FCL PE150; cat. no.

1000005267; BGI Genomics Co., Ltd.). The final library was loaded

at a concentration of 10 pM, quantified using a Qubit Fluorometer

and calculated based on molar concentration. Raw sequencing data

were processed with SOAPnuke (v1.5.6, https://github.com/BGI-flexlab/SOAPnuke) for quality

control, and downstream analysis, including alignment, variant

calling and annotation, was performed using Sentieon DNAseq

(v202112.05; https://www.sentieon.com/), following the standard

bioinformatics pipeline for BGI Genomics Co., Ltd. The histological

and genetic analysis confirmed the presence of a papillary

craniopharyngioma with a BRAFV600E mutation, accompanied by a

marked inflammatory infiltrate (Fig.

5). Microbial cultures from intraoperative specimens were

negative; however, next-generation sequencing (NGS) identified a

Gram-positive Staphylococcus species, confirming a secondary

pituitary abscess. Immediate postoperative MRI (Fig. 6) revealed complete resection of the

lesion and a marked reduction in the mass effect. A follow-up

hormone level assessment (Table I)

was performed, confirming persistent hypopituitarism. The patient

continued on antibiotic therapy (1,000 mg ceftriaxone, every day,

intravenously for 3 weeks), levetiracetam (500 mg, twice per day,

orally; continued postoperatively for prophylactic purposes) for

seizure control, and hormone replacement therapy (50 µg

levothyroxine, every day, orally; 10 mg prednisone, every day,

orally; long-term postoperative replacement therapy was maintained

until pituitary function recovered). The drainage tube was removed

on the fifth postoperative day.

At the 3-month follow-up, the patient's vision had

markedly improved, with better peripheral vision and reduced visual

field defects. However, long-term hormone replacement therapy,

including hydrocortisone, levothyroxine and desmopressin, was still

required to manage the pituitary insufficiency and diabetes

insipidus. The patient remains under regular follow-up (initially

once a month, and then once every 3 months.) to monitor endocrine

function and assess for potential recurrence.

Discussion

Pituitary abscesses are rare in clinical practice

and poorly understood. Pituitary abscesses are classified as either

primary or secondary, depending on the presence or absence of

underlying pituitary lesions. Secondary pituitary abscesses can

occur in association with pre-existing conditions such as

craniopharyngiomas, Rathke's cleft cysts and pituitary adenomas

(8).

In a systematic review of 488 cases of pituitary

abscesses, Stringer et al (6) found that 68% were primary and 32%

were secondary. Secondary infections can be further divided into

iatrogenic infections following surgery and spontaneous infections.

Iatrogenic infections may be caused by a disruption of the normal

blood supply to the pituitary, leading to decreased immune function

in the sellar region (9), or by

retrograde infection from sphenoid sinusitis (10,11).

In addition to iatrogenic infections, there are a number of reports

(2,12-14)

of pituitary abscesses secondary to pre-existing sellar lesions,

accounting for ~37% of secondary pituitary abscesses (15). This situation is the primary issue

that the present study aims to discuss in relation to the present

patient.

The English research literature was searched for

isolated case reports of pituitary abscesses secondary to sellar

lesions. A systematic literature search was performed using the

PubMed database. The following search terms were used: ['pituitary

abscess'(All Fields) OR 'sellar abscess'(All Fields)] AND ['case

report'(Title/Abstract) OR 'case series'(Title/Abstract)] AND

['secondary'(Title/Abstract) OR 'sellar lesion'(Title/Abstract) OR

'sellar mass'(Title/Abstract) OR 'sellar tumor'(Title/Abstract)].

These scattered cases suggested that the pathophysiological

mechanisms of such abscess formation are poorly understood

(Table II) (2,9,13-47).

| Table IIReported cases of secondary sellar

infections following sellar lesions (1952-2024). |

Table II

Reported cases of secondary sellar

infections following sellar lesions (1952-2024).

| First author,

year | Cases, n | Pathological

diagnosis | Culture | Treatment | Outcome | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Whalley, 1952 | 1 | Pituitary

adenoma | Escherichia

coli | None | Died before

treatment | (16) |

| De Villiers

Hammann, 1956 | 1 | Pituitary

adenoma | Staphylococcus

aureus | Transcranial

surgery | Recovered | (17) |

| Obenchain and

Becker, 1972 | 1 | Rathke's cleft

cyst | Staphylococcus

aureus | Transcranial

surgery | Recovered | (18) |

| Obrador and

Blazquez, 1972 | 1 |

Craniopharyngioma | Negative | Transcranial

surgery | Recovered | (19) |

| Domingue and

Wilson, 1977 | 2 | Pituitary

adenoma | 1 negative; 1

Diplococcus pneumoniae | 1 Transcranial

surgery; 1 transnasal surgery | 1 died after

recurrence; 1 died after sepsis | (20) |

| Zorub et al,

1979 | 1 | Pituitary

adenoma | Streptococcus

pneumoniae | Transnasal

surgery | Died after acute

hydrocephalus | (21) |

| Gomez Perun et

al, 1981 | 1 | Rathke's cleft

cyst | NS | Transcranial

surgery | NS | (22) |

| Holck and Laursen,

1983 | 1 | Pituitary

adenoma | Negative | Transnasal

surgery | NS | (23) |

| Nelson et

al, 1983 | 3 | Pituitary

adenoma |

Bacteroides | 1 transcranial

surgery; 2 transnasal surgery | 3 recovered | (24) |

| Bossard et

al, 1992 | 1 | Pituitary

adenoma | NS | Transnasal

surgery | NS | (25) |

| Bognàr et

al, 1992 | 2 | Rathke's cleft

cyst | Staphylococcus

aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes | 1 transcranial and

transnasal surgery; 1 transnasal surgery | 1 died after

secondary surgery; 1 recovered | (26) |

| Shanley and Holmes,

1994 | 1 |

Craniopharyngioma | Salmonella

typhi | Transnasal

surgery | Recovered | (27) |

| Jain et al,

1997 | 2 | 1 Rathke's cleft

cyst, 1 pituitary adenoma | 1 negative; 1

Aspergillus | 1 transcranial

surgery, 1 transnasal surgery | 2 recovered | (28) |

| Thomas et

al, 1998 | 1 | Rathke's cleft

cyst | Anaerobic

streptococci | Transnasal

surgery | NS | (29) |

| Jadhav et

al, 1998 | 1 | Pituitary

adenoma | Staphylococcus

epidermidis | Transcranial

surgery | Recovered | (30) |

| Sharma et

al, 2000 | 1 | Pituitary

adenoma | Tuberculosis | NS | Recovered | (31) |

| Kroppenstedt et

al, 2001 | 1 | Pituitary

adenoma | Negative | Transnasal

surgery | Recovered | (32) |

| Vates et al,

2001 | 5 | 3 pituitary

adenoma, 1 craniopharyngioma; 1 rathke's cleft cyst | 2 negative; 1

Streptococcus pneumoniae; 1 Staphylococcus aureus; 1

alpha Streptococcus | NS | NS | (9) |

| Zhang et al,

2002 | 1 | Pituitary

adenoma | Toxoplasma

gondii | NS | NS | (33) |

| Jaiswal et

al, 2004 | 1 | Pituitary

adenoma | Escherichia

coli | Transnasal

surgery | Recovered | (34) |

| Hatiboglu et

al, 2006 | 1 | Pituitary

adenoma | Gram-positive

cocci | Transnasal

surgery | Recovered | (35) |

| Dutta et al,

2006 | 1 | Pituitary

adenoma | MRSA | Transnasal

surgery | Recovered | (36) |

| Celikoglu et

al, 2006 | 2 | Rathke's cleft

cyst | NS | Transnasal

surgery | 2 recovered | (37) |

| Takayasu et

al, 2006 | 1 | Rathke's cleft

cyst | Pseudomonas

aeruginosa | Transnasal

surgery | Recovered | (38) |

| Salinas-Lara et

al, 2008 | 1 | Pituitary

adenoma | Mucormycosis | Transnasal

surgery | Died during

surgery | (39) |

| Ciappetta et

al, 2008 | 1 | Pituitary

adenoma | Negative | Transnasal

surgery | Recovered | (15) |

| Qi et al,

2009 | 1 |

Craniopharyngioma | Staphylococcus

aureus | Transcranial

surgery | Recovered | (40) |

| Bakker and Hoving,

2010 | 1 | Pituitary

adenoma | MRSA | Transcranial

surgery | Recovered | (41) |

| Kuge et al,

2011 | 1 | Pituitary

adenoma | Gram-positive

cocci | Transnasal

surgery | Recovered | (42) |

| Kotani et

al, 2012 | 1 | Pituitary

adenoma | Gram-negative

cocci | None | Died | (43) |

| Awad et al,

2014 | 4 | Pituitary

adenoma | 1 group A

Streptococcus; 1 staphylococcus epidermidis; 1 MRSA;

1 Streptococcus pneumoniae | Transnasal

surgery | 3 recovered; 1

died | (14) |

| Safaee et

al, 2016 | 1 | Pituitary

adenoma | Staphylococcus

aureus | Transnasal

surgery | Recovered | (2) |

| Muscas et

al, 2017 | 1 | Pituitary

adenoma | Negative | Transcranial

surgery | Died after

surgery | (44) |

| Bhaisora et

al, 2018 | 1 |

Craniopharyngioma | Staphylococcus

aureus | Transnasal

surgery | Recovered | (45) |

| Coulden et

al, 2022 | 1 | Rathke's cleft

cyst | Staphylococcus

aureus | Transnasal

surgery | Recovered | (46) |

| López Goméz et

al, 2022 | 1 |

Caniopharyngioma | Negative | Transnasal

surgery | Recovered | (13) |

| Inoue et al,

2024 | 1 | Rathke's cleft

cyst | Negative | Transnasal

surgery | Recovered | (47) |

Pituitary abscesses are rare but serious

complications, often arising as secondary infections in the context

of underlying sellar lesions, including craniopharyngiomas. The

pathophysiology behind secondary pituitary abscesses is

multifactorial. Craniopharyngiomas, being locally invasive tumors,

may cause significant inflammatory responses, leading to tumor

necrosis and subsequent abscess formation. Additionally, the

disruption of vascular supply to the pituitary gland due to the

tumor's encroachment can compromise immune defenses, further

predisposing the patient to infection (45,48).

In the present case, the patient's craniopharyngioma exhibited

extensive inflammatory infiltration, which likely contributed to

the development of the abscess. A retrograde infection from

adjacent structures, such as the sphenoid sinus or the nasopharynx,

cannot be ruled out as a contributing factor. In the present case,

the MRI findings suggested a mixed cystic-solid lesion in the

suprasellar region, which was consistent with the craniopharyngioma

(13). While the role of

tumor-induced necrosis has been implicated in other reports, immune

dysfunction plays a significant role in increasing the risk of

secondary infections in these patients. In the present case, the

inflammatory changes seen in the craniopharyngioma likely

compromised local immune responses, predisposing the patient to the

development of an abscess.

Clinically, secondary pituitary abscesses often

present with symptoms related to the mass effect of the primary

lesion and signs of infection. The most common non-specific

symptoms include headache (91.7%) (8). Blurred vision and visual field

defects (58%) (49) are the second

most frequent symptoms, following headache. In addition to the mass

effect, inflammation of the optic nerve and optic chiasm due to the

abscess can also contribute to visual disturbances. Moreover,

pituitary hormone secretion may be impaired due to the involvement

of the pituitary gland, leading to hypopituitarism, with

panhypopituitarism being the most common manifestation. The extent

of pituitary dysfunction can reflect the severity of the abscess

(50). This feature can make it

difficult to differentiate from non-functioning pituitary adenomas;

however, the latter typically do not present with signs of

infection. If the lesion involves the pituitary stalk, polyuria

(50%) may occur, with a higher incidence than in pituitary adenomas

(51). The lack of typical

infectious symptoms aligns with the literature, where secondary

pituitary abscesses often lack clear signs of infection,

complicating the diagnosis (13).

Diagnosing secondary pituitary abscesses is often

challenging, particularly when they are associated with

pre-existing lesions, as demonstrated in the present case. The

initial clinical presentation of visual disturbances, headaches and

nausea can easily be misattributed to the primary craniopharyngioma

itself or to other more common causes of sellar mass effects.

Therefore, early suspicion and a comprehensive diagnostic approach

are crucial in identifying this rare complication. In the present

case, advanced imaging modalities, including MRI with contrast and

CT scans, were employed. Imaging by CT typically shows an enlarged

sella turcica and a low-density sellar mass, which does not

significantly aid in diagnosis. The typical MRI appearance is a

cystic or cystic-solid sellar mass that is hypointense or

isointense on T1-weighted images and hyperintense or isointense on

T2-weighted images. A characteristic finding is the rim enhancement

of the cystic mass after contrast administration (52,53).

Due to the restricted diffusion within the abscess cavity, it often

appears hyperintense on diffusion-weighted imaging, which can help

differentiate a pituitary abscess from other sellar lesions

(54). However, there are reported

cases that lack this feature (55,56).

According to reports, the most common causative

microorganisms in secondary pituitary abscesses are gram-positive

bacteria, including Staphylococcus and Streptococcus

species. However, as in the present case, numerous patients have

negative culture results whereby no pathogenic organisms are

identified from secretions. In >50% of cases, pathogens fail to

be isolated (57). This absence of

bacteria may be related to the use of antibiotics before surgery or

limitations of culture conditions (54-56).

Thus, metagenomic NGS (mNGS) is recommended for analyzing abscesses

and tissues obtained during surgery, as mNGS provides more accurate

information on the presence of pathogens. The mNGS platform can

perform high-throughput nucleic acid analysis of samples containing

microorganisms and match them to reference genomes to identify the

microbial species present and their relative abundance (57,58).

For the treatment of secondary pituitary abscesses,

surgical intervention is considered the preferred approach

(59). Surgery serves two primary

purposes: It alleviates the mass effect of the primary lesion and

promptly drains the infection, thereby preventing further

progression of the infection and minimizing the risk of permanent

neurological and pituitary dysfunction. Upon the identification of

symptoms suggestive of a pituitary abscess, empirical antibiotic

therapy should be initiated immediately to establish an optimal

window for surgical intervention. This early antibiotic treatment

is crucial in controlling infection and preparing the patient for

subsequent surgery.

Regarding surgical options, the endoscopic

transsphenoidal approach is generally the first choice due to its

ability to reduce the risk of infection spread and minimize damage

to critical structures such as the optic nerves. This minimally

invasive technique offers a relatively quick recovery time and

avoids the need for more invasive procedures. However, if the

pituitary abscess extends into the suprasellar region or if the

patient has contraindications for transnasal surgery (such as

anatomical anomalies or prior nasal surgery), a craniotomy may be

necessary for abscess drainage (60). Craniotomy, while effective, is

associated with a higher risk of abscess recurrence (7), and requires more extensive

postoperative care.

For the patient in the present case, the abscess had

significantly extended into the right frontal lobe, prompting the

decision to opt for craniotomy to ensure thorough and effective

drainage. During surgery, the abscess wall was excised completely

to minimize the risk of recurrence and repeated irrigation of the

surgical site was performed with saline and antibiotics to further

reduce the infection risk.

The timing of surgery is also critical. Procedures

should be avoided during the acute phase of infection or when the

patient presents with a high fever, as this can increase the risk

of bacteremia and sepsis. During this period, the patient should

receive appropriate antibiotic therapy and fluid support to manage

symptoms. The selection of antibiotics should be tailored to the

identified or suspected pathogen, with consideration for local

antibiotic resistance patterns (61). Emerging clinical guidelines

emphasize the importance of initiating broad-spectrum antibiotics

until culture or sequencing results are available, followed by a

more targeted regimen based on these findings (62).

Postoperatively, antibiotic therapy should continue

for 3-4 weeks, adjusted according to the results of culture or

sequencing. Although some patients may experience partial recovery

of pituitary function following surgery (32.3%) (7), hormone replacement therapy remains

essential. Long-term management is particularly important for

patients who had significant preoperative pituitary dysfunction, as

these individuals are at a high risk of developing permanent

hypopituitarism after surgery (59).

Usually, it is difficult to identify the primary

lesion in secondary pituitary abscesses based solely on the

patient's history and imaging before surgery. Only after obtaining

histopathological evidence during surgery can clinicians determine

the primary sellar lesion, although histopathology often does not

fully explain the source of the sellar infection. An early and

accurate diagnosis of a pituitary abscess, followed by timely

intervention, can lead to a better prognosis (63).

A comprehensive review of the literature highlights

that secondary pituitary abscesses are more commonly associated

with pituitary adenomas (64%) and Rathke's cleft cysts (24%) than

with craniopharyngiomas (12%). Despite the relatively low frequency

of craniopharyngioma-associated abscesses, this case illustrates

the significant differential diagnostic challenges that clinicians

face. Differential diagnoses for secondary pituitary abscesses

include other sellar lesions such as pituitary adenomas, Rathke's

cleft cysts and sellar metastases. Inflammatory conditions, such as

sarcoidosis or tuberculosis, should also be considered, as these

can mimic the clinical and radiological features of a pituitary

abscess (64). A detailed clinical

history, coupled with advanced imaging and microbiological workup,

is essential for distinguishing these entities.

The present case report had several limitations. The

lack of long-term follow-up is a significant limitation, as the

resolution of abscesses and recovery of pituitary function can

evolve over time. Additionally, the rarity of secondary pituitary

abscesses means that our understanding of the optimal treatment

regimen is still evolving. Further investigation, ideally through

multi-center studies, is necessary to establish consensus

guidelines for the management of this rare and challenging

condition.

In conclusion, the present case highlighted the rare

occurrence of a secondary pituitary abscess arising from a

craniopharyngioma, emphasizing the diagnostic and therapeutic

challenges associated with such cases. Given the overlapping

clinical and radiological features with other sellar lesions,

maintaining a high index of suspicion is crucial for early

identification. A multidisciplinary approach involving

neurosurgeons, endocrinologists and infectious disease specialists

is essential to ensure prompt diagnosis and tailored management.

The present literature review provided a more comprehensive

discussion of the pathophysiology, clinical implications and

management strategies for this rare entity. The importance of early

surgical intervention combined with appropriate antibiotic therapy

to optimize patient outcomes was underscored. Furthermore,

long-term follow-up is necessary to monitor endocrine function and

prevent recurrence. By detailing this case and analyzing the

existing literature, the present study aimed to enhance awareness

among clinicians regarding the potential for secondary pituitary

abscesses in patients with pre-existing sellar lesions, ultimately

contributing to improved diagnostic accuracy and patient care.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: This project was supported by the Key Research and

Development Plan of China (grant no. 2022YFB3204304).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

RF was the principal investigator who contributed

substantially to the study design, provided the treatment plan, and

was responsible for the analysis and interpretation of the

patient's clinical data. RF also participated in drafting and

revising the manuscript and approved the final version. WW designed

the case study, performed the surgical procedure, contributed to

the clinical decision-making, and was involved in the manuscript

revision. RZ and YZ were responsible for the acquisition of key

medical images, including MRI and CT scans. WW and RF confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. All authors have read and

approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was approved by the Ethics

Committee of Beijing Tiantan Hospital (Beijing, China; approval no.

KY2024-062-02). Studies involving human participants followed

ethical guidelines established by the institutional and/or national

research committee and complied with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration

and its subsequent amendments.

Patient consent for publication

The patient provided written informed consent for

the publication of the case report and associated clinical

images.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Gao L, Guo X, Tian R, Wang Q, Feng M, Bao

X, Deng K, Yao Y, Lian W, Wang R and Xing B: Pituitary abscess:

Clinical manifestations, diagnosis and treatment of 66 cases from a

large pituitary center over 23 years. Pituitary. 20:189–194.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Safaee MM, Blevins L, Liverman CS and

Theodosopoulos PV: Abscess formation in a nonfunctioning pituitary

adenoma. World Neurosurg. 90:703.e15–703.e18. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Mallereau CH, Todeschi J, Ganau M, Cebula

H, Bozzi MT, Romano A, Le Van T, Ollivier I, Zaed I, Spatola G, et

al: Pituitary abscess: A challenging preoperative diagnosis-A

multicenter study. Medicina (Kaunas). 59(565)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Aranda F, García R, Guarda FJ, Nilo F,

Cruz JP, Callejas C, Balcells ME, González G, Rojas R and

Villanueva P: Rathke's cleft cyst infections and pituitary

abscesses: Case series and review of the literature. Pituitary.

24:374–383. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Altas M, Serefhan A, Silav G, Cerci A,

Coskun KK and Elmaci I: Diagnosis and management of pituitary

abscess: A case series and review of the literature. Turk

Neurosurg. 23:611–616. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Stringer F, Foong YC, Tan A, Hayman S,

Zajac JD, Grossmann M, Zane JNY, Zhu J and Ayyappan S: Pituitary

abscess: A case report and systematic review of 488 cases. Orphanet

J Rare Dis. 18(165)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Agyei JO, Lipinski LJ and Leonardo J: Case

report of a primary pituitary abscess and systematic literature

review of pituitary abscess with a focus on patient outcomes. World

Neurosurg. 101:76–92. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Wang L, Yao Y, Feng F, Deng K, Lian W, Li

G, Wang R and Xing B: Pituitary abscess following transsphenoidal

surgery: The experience of 12 cases from a single institution. Clin

Neurol Neurosurg. 124:66–71. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Vates GE, Berger MS and Wilson CB:

Diagnosis and management of pituitary abscess: A review of

twenty-four cases. J Neurosurg. 95:233–241. 2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Batra PS, Citardi MJ and Lanza DC:

Isolated sphenoid sinusitis after transsphenoidal hypophysectomy.

Am J Rhinol. 19:185–189. 2005.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Caimmi D, Caimmi S, Labò E, Marseglia A,

Pagella F, Castellazzi AM and Marseglia GL: Acute isolated sphenoid

sinusitis in children. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 25:e200–e202.

2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Zhang X, Yu G, Du Z, Tran V, Zhu W and Hua

W: Secondary pituitary abscess inside adenoma: A case report and

review of literature. World Neurosurg. 137:281–285. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

López Gómez P, Mato Mañas D, Bucheli

Peñafiel C, Rodríguez Rodríguez EM, Pazos Toral FA, Obeso Aguera S,

Viera Artiles J, Yange Zambrano G, Marco de Lucas E and Martín Láez

R: A rare case of a secondary pituitary abscess arising in a

craniopharyngioma with atypical presentation and clinical course.

Neurocirugia (Engl Ed). 33:99–104. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Awad AJ, Rowland NC, Mian M, Hiniker A,

Tate M and Aghi MK: Etiology, prognosis, and management of

secondary pituitary abscesses forming in underlying pituitary

adenomas. J Neurooncol. 117:469–476. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Ciappetta P, Calace A, D'Urso PI and De

Candia N: Endoscopic treatment of pituitary abscess: Two case

reports and literature review. Neurosurg Rev. 31:237–246.

2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Whalley N: Abscess formation in a

pituitary adenoma. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 15:66–67.

1952.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

De Villiers Hammann H: Abscess formation

in the pituitary fossa associated with a pituitary adenoma. J

Neurosurg. 13:208–210. 1956.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Obenchain TG and Becker DP: Abscess

formation in a Rathke's cleft cyst. Case report. J Neurosurg.

36:359–362. 1972.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Obrador S and Blazquez MG: Pituitary

abscess in a craniopharyngioma. Case report. J Neurosurg.

36:785–789. 1972.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Domingue JN and Wilson CB: Pituitary

abscesses. Report of seven cases and review of the literature. J

Neurosurg. 46:601–608. 1977.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Zorub DS, Martinez AJ, Nelson PB and Lam

MT: Invasive pituitary adenoma with abscess formation: Case report.

Neurosurgery. 5:718–722. 1979.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Gomez Perun J, Eiras J and Carcavilla LI:

[Intrasellar abscess into a cyst of the Rathke's pouch (authors'

translation)]. Neurochirurgie. 27:201–205. 1981.PubMed/NCBI(in French).

|

|

23

|

Holck S and Laursen H: Prolactinoma

coexistent with granulomatous hypophysitis. Acta Neuropathol.

61:253–257. 1983.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Nelson PB, Haverkos H, Martinez AJ and

Robinson AG: Abscess formation within pituitary tumors.

Neurosurgery. 12:331–333. 1983.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Bossard D, Himed A, Badet C, Lapras V,

Mornex R, Fisher G, Tavernier T and Bochu M: MRI and CT in a case

of pituitary abscess. J Neuroradiol. 19:139–144. 1992.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Bognàr L, Szeifert GT, Fedorcsàk I and

Pàsztor E: Abscess formation in Rathke's cleft cyst. Acta Neurochir

(Wien). 117:70–72. 1992.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Shanley DJ and Holmes SM: Salmonella

typhi abscess in a craniopharyngioma: CT and MRI.

Neuroradiology. 36:35–36. 1994.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Jain KC, Varma A and Mahapatra AK:

Pituitary abscess: A series of six cases. Br J Neurosurg.

11:139–143. 1997.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Thomas N, Wittert GA, Scott G and Reilly

PL: Infection of a Rathke's cleft cyst: A rare cause of pituitary

abscess. Case illustration. J Neurosurg. 89(682)1998.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Jadhav RN, Dahiwadkar HV and Palande DA:

Abscess formation in invasive pituitary adenoma: Case report.

Neurosurgery. 43:616–619. 1998.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Sharma MC, Arora R, Mahapatra AK,

Sarat-Chandra P, Gaikwad SB and Sarkar C: Intrasellar

tuberculoma--an enigmatic pituitary infection: A series of 18

cases. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 102:72–77. 2000.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Kroppenstedt SN, Liebig T, Mueller W, Gräf

KJ, Lanksch WR and Unterberg AW: Secondary abscess formation in

pituitary adenoma after tooth extraction. Case report. J Neurosurg.

94:335–338. 2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Zhang X, Li Q, Hu P, Cheng H and Huang G:

Two case reports of pituitary adenoma associated with Toxoplasma

gondii infection. J Clin Pathol. 55:965–966. 2002.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Jaiswal AK, Mahapatra AK and Sharma MC:

Pituitary abscess associated with prolactinoma. J Clin Neurosci.

11:533–534. 2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Hatiboglu MA, Iplikcioglu AC and Ozcan D:

Abscess formation within invasive pituitary adenoma. J Clin

Neurosci. 13:774–777. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Dutta P, Bhansali A, Singh P, Kotwal N,

Pathak A and Kumar Y: Pituitary abscess: Report of four cases and

review of literature. Pituitary. 9:267–273. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Celikoglu E, Boran BO and Bozbuga M:

Abscess formation in Rathke's cleft cyst. Neurol India. 54:213–214.

2006.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Takayasu T, Yamasaki F, Tominaga A, Hidaka

T, Arita K and Kurisu K: A pituitary abscess showing high signal

intensity on diffusion-weighted imaging. Neurosurg Rev. 29:246–248.

2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Salinas-Lara C, Rembao-Bojórquez D, de la

Cruz E, Márquez C, Portocarrero L and Tena-Suck ML: Pituitary

apoplexy due to mucormycosis infection in a patient with an ACTH

producing pulmonary tumor. J Clin Neurosci. 15:67–70.

2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Qi S, Peng J, Pan J, Lu Y and Fan J:

Secondary abscess arising in a craniopharyngioma. J Clin Neurosci.

16:1667–1669. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Bakker NA and Hoving EW: A rare case of

sudden blindness due to a pituitary adenoma coincidentally infected

with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA).

Acta Neurochir (Wien). 152:1079–1080. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Kuge A, Sato S, Takemura S, Sakurada K,

Kondo R and Kayama T: Abscess formation associated with pituitary

adenoma: A case report: Changes in the MRI appearance of pituitary

adenoma before and after abscess formation. Surg Neurol Int.

2(3)2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Kotani H, Abiru H, Miyao M, Kakimoto Y,

Kawai Y, Ozeki M, Tsuruyama T and Tamaki K: Pituitary abscess

presenting a very rapid progression: Report of a fatal case. Am J

Forensic Med Pathol. 33:280–283. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Muscas G, Iacoangeli F, Lippa L and

Carangelo BR: Spontaneous rupture of a secondary pituitary abscess

causing acute meningoencephalitis: Case report and literature

review. Surg Neurol Int. 8(177)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Bhaisora KS, Prasad SN, Das KK and Lal H:

Abscess inside craniopharyngioma: Diagnostic and management

implications. BMJ Case Rep. 2018(bcr2017223040)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Coulden A, Pepper J, Juszczak A, Batra R,

Chavda S, Senthil L, Ayuk J, Phol U, Nagaraju S, Karavitaki N and

Tsermoulas G: Rathke's Cleft Cyst Abscess with a Very Unusual

Course. Asian J Neurosurg. 17:527–531. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Inoue E, Kesumayadi I, Fujio S, Makino R,

Hanada T, Masuda K, Higa N, Kawade S, Niihara Y, Takagi H, et al:

Secondary hypophysitis associated with Rathke's cleft cyst

resembling a pituitary abscess. Surg Neurol Int.

15(69)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Han SJ, Rolston JD, Jahangiri A and Aghi

MK: Rathke's cleft cysts: Review of natural history and surgical

outcomes. J Neurooncol. 117:197–203. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Dalan R and Leow MKS: Pituitary abscess:

Our experience with a case and a review of the literature.

Pituitary. 11:299–306. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Liu F, Li G, Yao Y, Yang Y, Ma W, Li Y,

Chen G and Wang R: Diagnosis and management of pituitary abscess:

Experiences from 33 cases. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 74:79–88.

2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

St-Pierre GH, de Ribaupierre S, Rotenberg

BW and Benson C: Pituitary abscess: Review and highlight of a case

mimicking pituitary apoplexy. Can J Neurol Sci. 40:743–745.

2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Wang Z, Gao L, Zhou X, Guo X, Wang Q, Lian

W, Wang R and Xing B: Magnetic resonance imaging characteristics of

pituitary abscess: A review of 51 cases. World Neurosurg.

114:e900–e912. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Connor SEJ and Penney CC: MRI in the

differential diagnosis of a sellar mass. Clin Radiol. 58:20–31.

2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Taguchi Y, Yoshida K, Takashima S and

Tanaka K: Diffusion-weighted MRI findings in a patient with

pituitary abscess. Intern Med. 51(683)2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Huang KT, Bi WL, Smith TR, Zamani AA, Dunn

IF and Laws ER Jr: Intrasellar abscess following pituitary surgery.

Pituitary. 18:731–737. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Kawano T, Shinojima N, Hanatani S, Araki

E, Mikami Y and Mukasa A: Atypical pituitary abscess lacking rim

enhancement and diffusion restriction with an unusual organism,

Moraxella catarrhalis: A case report and review of the

literature. Surg Neurol Int. 12(617)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Zhang Y, Cui P, Zhang HC, Wu HL, Ye MZ,

Zhu YM, Ai JW and Zhang WH: Clinical application and evaluation of

metagenomic next-generation sequencing in suspected adult central

nervous system infection. J Transl Med. 18(199)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

58

|

Sherrod BA, Makarenko S, Iyer RR, Eli I,

Kestle JR and Couldwell WT: Primary pituitary abscess in an

adolescent female patient: Case report, literature review, and

operative video. Childs Nerv Syst. 37:1423–1428. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

59

|

Ovenden CD, Almeida JP, Oswari S and

Gentili F: Pituitary abscess following endoscopic endonasal

drainage of a suprasellar arachnoid cyst: Case report and review of

the literature. J Clin Neurosci. 68:322–328. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

60

|

Oktay K, Guzel E, Yildirim DC, Aliyev A,

Sari I and Guzel A: Primary pituitary abscess mimicking meningitis

in a pediatric patient. Childs Nerv Syst. 37:3241–3244.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

61

|

Walia R, Bhansali A, Dutta P,

Shanmugasundar G, Mukherjee KK, Upreti V and Das A: An uncommon

cause of recurrent pyogenic meningitis: Pituitary abscess. BMJ Case

Rep. 23(bcr0620091945)2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

62

|

Lin L, Fang J, Li J, Tang Y, Xin T, Ouyang

N, Cai W, Xie L, Lu S and Zhang J: Metagenomic next-generation

sequencing contributes to the early diagnosis of mixed infections

in central nervous system. Mycopathologia. 189(34)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

63

|

Cabuk B, Caklılı M, Anık I, Ceylan S,

Celik O and Ustün C: Primary pituitary abscess case series and a

review of the literature. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. 40:99–104.

2019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Zhang X, Sun J, Shen M, Shou X, Qiu H,

Qiao N, Zhang N, Li S, Wang Y and Zhao Y: Diagnosis and minimally

invasive surgery for the pituitary abscess: A review of twenty nine

cases. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 114:957–961. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|