Introduction

Femtosecond laser, as an infrared laser, has the

advantages of a short action time, high instantaneous power and a

small thermal effect area. Thus, it can achieve high-precision

incisions (1). Small-incision

lenticule extraction (SMILE) uses a femtosecond laser to perform

three-dimensional scanning of the corneal stroma to form a

lenticule. The lenticule was then removed from the corneal stroma

through a small (2-4 mm) incision to correct myopia. The SMILE

procedure is safe, effective and highly predictable. Studies have

shown that it has better corneal biomechanics compared to

traditional surgery (2). Owing to

its significant clinical advantages, SMILE is being increasingly

adopted by experts. The corneal stromal lenticule is a biological

material that can be used to correct hyperopia (3,4) and

treat corneal ulcers, perforations (5,6) and

keratoconus (7-9).

Conical cornea is a common, progressive,

non-inflammatory corneal degeneration disease that typically

develops in adolescents (10).

Early refractive correction involves the use of frames and rigid

gas-permeable (RGP) lenses, whereas disease progression is

controlled by corneal collagen cross-linking. Corneal collagen

cross-linking uses chemical principles to increase the connections

between collagen fibres, thereby enhancing the biomechanics of the

cornea and controlling keratoconus progression (11,12).

High-energy UV irradiation can damage the corneal endothelium and

lenticule. Therefore, the cornea must be 400 µm or greater in

thickness before the cross-linking procedure to minimise damage to

the corneal endothelium and lenticule (13). Consequently, patients with advanced

keratoconus and thin corneas face significant treatment

limitations. Treatment options for this group of patients include

corneal transplantation or lenticule implantation, depending on the

degree of scarring (14).

Femtosecond laser-assisted lenticule transplantation

is used to treat keratoconus by implanting a surgically acquired

stromal lenticule into the recipient's stromal capsular bag through

a small 2-4 mm incision (15).

This surgical procedure is flapless, minimally invasive,

single-step and does not require postoperative sutures. Therefore,

suture scarring can be avoided. The increased thickness of the

cornea postoperatively also enhances its biomechanical strength to

a certain extent. Corneal stromal lenticule implantation for

keratoconus has several advantages and limitations. SMILE-derived

lenticules, used in myopia correction, are convex, with a thick

centre and thin edges (15). In

comparison, patients with keratoconus are characterised by a

central anterior protrusion and an increase in curvature (16). Therefore, the curvature does not

improve or even become increasingly steep despite an increase in

the thickness. This phenomenon may result in intolerance to

postoperative framed lenticules. It may also cause a poor RGP fit,

difficulty in refractive reconstruction and poor patient

satisfaction (7,8). The excimer laser can cut corneal

tissues with high precision without affecting tissues outside the

cutting area, making it highly safe (17). In the present study, excimer laser

cutting of the corneal stromal lenticule was performed. Thus, a

corneal stromal lenticule is produced, which is either parallel or

concave. Consequently, the thickness of the corneal cone can be

increased while avoiding excessive curvature during the

postoperative period. This outcome is conducive to refractive

reconstruction.

Patients and methods

Study objective and grouping

A total of 75 patients (111 eyes) who underwent

SMILE surgery at Jinan Mingshui Eye Hospital (Jinan, China) between

September 2023 and April 2024 were selected for this study. All

patients voluntarily came to Jinan Mingshui Eye Hospital for

refractive surgery, and none had received any treatment for an eye

condition. A complete ophthalmological examination was performed

before the surgery. The surgically designed spherical equivalent

lenticule was -6.75 [interquartile range (IQR): -7.00, -6.38;

range: -8.13, -5.00] D. Astigmatism in each eye did not exceed 1.00

D. A complete preoperative ophthalmological examination was

conducted. The lenticules were randomly divided into three groups

at a ratio of 1:1:1 using a random number table. Each group

consisted of 37 lenticules. Group I was cut using a 1:1 ratio

according to the equivalent spherical mirror of the lenticule

itself (diopters of the excimer laser cutting=equivalent spherical

power of the lenticule). Group II was cut using a 1:1.5 ratio

(excimer laser cutting diopter=1.5 times the equivalent spherical

lenticule). Group III was cut at a 1:2 ratio (diopters of excimer

laser cutting=2 times the equivalent spherical power of the

lenticule). After cutting, the thickness measurements of the centre

of the corneal stromal lenticule were repeated at distances of 1.5,

2 and 2.5 mm from the centre. The interval between pre- and

post-cutting measurements was recorded as the time T. The research

protocol complied with the principles of the Declaration of

Helsinki and was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Jinan

Mingshui Eye Hospital (Ref. Ethics/2024/004). Informed consent was

obtained from all adult participants and the guardians of juvenile

participants. A pre-experiment was conducted before the main

experiment, in which the degree of expansion of the corneal stromal

lenticule in the balanced salt solution was measured. Based on

this, the ratios were designed as a reference.

Corneal stromal lenticule acquisition

process

All patients underwent a detailed ophthalmological

examination before surgery and the same experienced physician

performed all of the surgeries. Levofloxacin eye drops

(levofloxacin bromofenac sodium; Ruilin Medicince) were routinely

administered for 1 day before surgery, with a total dosage of 5 ml.

Furthermore, local anaesthetic proparacaine hydrochloride eye drops

were applied for surface anaesthesia after rinsing the conjunctival

sac and routinely disinfecting the periocular area during

preoperative preparations, with two applications, each containing

one drop (~0.1 ml in total; concentration, 0.5%). Femtosecond laser

lenticule production and small-incision parameters included the

following: Visumax 500 kHz femtosecond Laser System (Carl Zeiss

AG); laser pulse frequency, 500 kHz; energy, 130 nJ; lenticule

cutting diameter, 6.5 mm; corneal cap thickness, 120 µm; and

small-incision length, 2 mm (18).

The removed stromal lenticules were placed on a flat surface of a

Petri dish. Subsequently, one to two drops of balanced salt

solution were added to flatten the stromal lenticules.

Measurement of corneal stromal

lenticules

Measurements were taken using an optical coherence

tomography (OCT) scanner (RTVue100-2; Kelin Instrument Co., Ltd.).

Preparations and measurements were conducted at the same suitable

temperature (temperature, 20±0.5˚C; humidity, 42±2%). The excess

liquid on the surface and sides of the lenticule was absorbed using

a surgical sponge. The preparation process was completed in 1 min.

The Petri dish was then fixed to the homemade fixation device made

from foam, which was positioned in front of the OCT. The thickness

of the corneal stromal lenticule was measured at the centre and

1.5, 2 and 2.5 mm from the centre. Immediately after the

measurement, the flat dish was placed on an Amax excimer machine

for excimer cutting and the optical zone of the cutting was set to

4 mm.

Data processing

The change in central thickness was represented by

the central thickness change (ctc). The thickness changes at 1.5,

2.0 and 2.5 mm from the centre were denoted as 1.5tc, 2tc and

2.5tc, respectively. Lenticule concavity was expressed as the

difference between the central thickness and thickness at 2 mm from

the centre (ct-2t). ct-2t values #x003C;-3 µm indicate a concave

lens, values between -3 and 3 µm indicate a parallel lens and

values >3 µm indicate a convex lens.

Statistical analysis

All data were analysed using SPSS version 27.0 (IBM

Corp.). The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to assess the normal

distribution of data. If the normal distribution and χ2

criteria were met, a one-way ANOVA was used with the Least

Significant Difference post hoc test. If the assumptions were not

met, the data were analysed using the Kruskal-Wallis test and the

Dunn's test was employed as the post hoc test. The χ2

test was used for sex in Table I.

P#x003C;0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

| Table IBasic information statistics of

patients before the operation. |

Table I

Basic information statistics of

patients before the operation.

| Parameter | Total (n=111) | Group I (n=37) | Group II (n=37) | Group III (n=37) | H-value | P-value |

|---|

| Age, years | 22 (19, 25) | 22 (21, 23) | 20 (18, 23) | 20 (20.5, 27.5) | 5.342 | 0.069 |

| Sex | | | | | 1.510 | 0.470 |

|

Male | 60 (54.1) | 18 (48.6) | 19 (51.4) | 23 (62.2) | | |

|

Female | 51 (45.9) | 19 (51.4) | 18 (48.6) | 14 (37.8) | | |

| Diopters | -6.75 (-7.00,

-6.38) | -6.88 (-7.25,

-6.57) | -6.75 (-7.00,

-6.44) | -6.5 (-7.00,

-6.07) | 5.265 | 0.072 |

| Spherical

diopters | -6.5 (-6.75,

-6.00) | -6.75 (-7.00,

-6.25) | -6.37 (-6.75,

-6.06) | -6.25 (-6.75,

-5.75) | 5.595 | 0.061 |

| Cylindrical

diopters | -0.5 (-0.75,

-0.25) | -0.50 (-0.75,

-0.25) | -0.50 (-0.75,

-0.25) | -0.50 (-0.75,

-0.25) | 2.075 | 0.354 |

Results

Basic information statistics of

patients

Participants were aged 17-35 years (23.15±4.982

years). The surgically designed equivalent spherical lenticule was

-6.75 (-7.00, -6.38) (range, -8.13 - -5.00 D). Astigmatism in each

eye did not exceed 1.00 D. Basic information statistics showed no

statistically significant differences in age, sex or diopters among

the three groups (Table I).

Comparison of pre-plastic thickness in

the three groups

No statistically significant differences were found

among the three groups in the plastic anterior centre, thickness at

distances of 1.5, 2 and 2.5 mm from the centre, or ct-2t (Table II).

| Table IIComparison of pre-shaping thickness

among the three groups and between two groups. |

Table II

Comparison of pre-shaping thickness

among the three groups and between two groups.

| Parameter | Group I, µm | Group II, µm | Group III, µm | F/H value | P-value |

|---|

| Center [M

(P25, P75)] | 247 (225.5, 257) | 236 (216, 245) | 243 (223.5,

253.5) | 4.832 | 0.890 |

| 1.5 mm [M

(P25, P75)] | 205 (184, 220) | 189 (180, 203) | 197 (184.5,

213.5) | 5.054 | 0.080 |

| 2 mm (x̄ ± SD) | 173.162±23.367 | 162.054±18.824 | 165.622±16.914 | 3.009 | 0.053 |

| 2.5 mm [M

(P25, P75)] | 128 (118, 142) | 120 (112, 130) | 120 (111, 134) | 5.086 | 0.079 |

| ct-2t [M

(P25, P75)] | 72 (60, 80.5) | 69 (61.5, 80.5) | 72 (62, 83) | 0.663 | 0.718 |

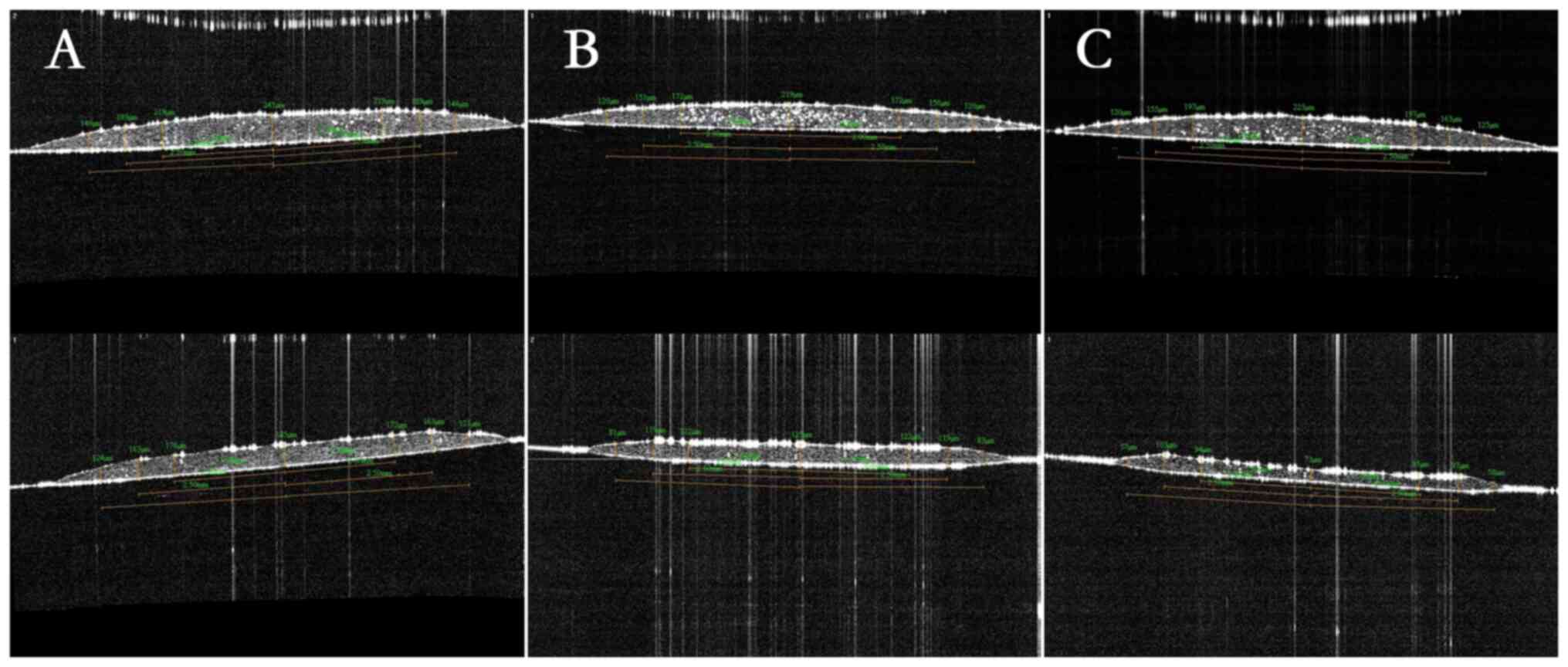

Comparison of the three groups

The cuttings of the three groups are shown in

Fig. 1. The difference between the

two measurement intervals (T) in the three groups was not

statistically significant (Table

III). The difference in ctc and 1.5tc of the three groups was

statistically significant. No statistically significant differences

were observed in the 2tc or 2.5tc values of the three groups. The

difference in ct-2t after laser plasticity was statistically

significant among the three groups (Table III).

| Table IIIComparison of post-shaping thickness

among the three groups and between two groups. |

Table III

Comparison of post-shaping thickness

among the three groups and between two groups.

| Considerations | Group I | Group II | Group III | F/H value | P-value | a | b | c |

|---|

| ctc, µm [M

(P25, P75)] | 75 (66, 84) | 111 (100, 124) | 138 (128, 147) | 82.082 | #x003C;0.001 | #x003C;0.001 | #x003C;0.001 | #x003C;0.001 |

| 1.5tc, µm [M

(P25, P75)] | 54 (47.5,

63.5) | 73 (62, 86) | 88 (81, 94.5) | 51.623 | #x003C;0.001 | #x003C;0.001 | #x003C;0.001 | #x003C;0.001 |

| 2tc, µm (x̄ ±

SD) | 48.351±18.662 | 46.784±14.675 | 53.162±12.518 | 1.702 | 0.187 | | | |

| 2.5tc, µm [M

(P25, P75)] | 36 (32, 42) | 41 (35.5,

53.5) | 39 (34, 50) | 5.147 | 0.076 | | | |

| ct-2t, µm [M

(P25, P75)] | 38 (28, 53.5) | 6 (-3, 15.5) | -10 (-16.5,

-5) | 87.169 | #x003C;0.001 | #x003C;0.001 | #x003C;0.001 | #x003C;0.001 |

| T, min [M

(P25, P75)] | 3.27 (2.67,

4.75) | 4.1 (2.94,

4.5) | 3.69 (2.51,

4.35) | 3.071 | 0.215 | | | |

Postplasticisation ct-1/4t

After laser plasticity, Group I had a ct-2t of 38

(IQR, 28, 53.5) µm, Group II had a ct-2t of 6 (IQR, -3, 15.5) µm

and Group III had a ct-2t of -10 (IQR, -16.5, -5) µm (Table III).

Discussion

Femtosecond laser-assisted corneal lenticule

transplantation has achieved good results in the treatment of

conical corneas. Zhao et al (7), Wang et al (8) and Sun et al (9) used surface lenticule transplantation

combined with corneal collagen cross-linking to treat patients with

advanced keratoconus and thin corneas. The postoperative surface

lenticules were well-adhered, with increased corneal thickness, and

a significant reduction of irregular astigmatism. Furthermore, the

mean keratometry (K) value, steep K value and maximal postoperative

surface height value stabilised from the third month. Li et

al (19) reported a case of

corneal dilatation after laser-assisted in situ

keratomileusis (LASIK). SMILE allogeneic lenticule lamellar

transplantation was performed first, followed by corneal collagen

cross-linking surgery 4 months postoperatively. Follow-up was

maintained for 30 months. Therefore, the corneal thickness

increased and the corneal morphology stabilised. Previous studies

have collectively demonstrated the safety and efficacy of corneal

stromal lenticule implantation combined with corneal collagen

cross-linking for the treatment of keratoconus.

However, the process of effectively controlling the

further development of keratoconus can lead to a further increase

in corneal curvature in patients with the disease, thereby

resulting in difficulty in postoperative refractive reconstruction.

For instance, Zhao et al (7) used surface lenticule implantation

combined with corneal collagen cross-linking to treat a patient

with advanced keratoconus who could not tolerate an RGP contact

lens. Preoperatively, the steep K was 62.7 D and the average K was

55.4 D. At three years postoperatively, the steep K was 63.8 D,

with an average K value of 61.9 D. Wang et al (8) reported that surface lenticule

implantation combined with cross-linking for thin corneal cone

treatment resulted in a corneal curvature that was significantly

higher than that at 1 and 3 months after surgery. Li et al

(19) reported that in patients

with corneal dilatation after LASIK, the preoperative flat

keratometry (K1), steep keratometry (K2) and

maximum keratometry (Kmax) values were 57.5, 67.2 and 74.9 D,

respectively. Simultaneously, the postoperative K1,

K2 and Kmax values were 59.7, 71.7 and 82.7 D,

respectively. Sun et al (9)

reported that preoperative K1 was 55.26 D, K2

was 64.80 D and the mean K value was 59.65 D. One year after

surgery, the K1, K2 and mean K values were

62.44, 64.04 and 63.23 D, respectively. These values were

significantly higher than the preoperative values. In a recent

domestic study, Gao et al (20) used parallel lenticule row corneal

transplantation to avoid these problems. Furthermore, a

statistically significant decrease in anterior central corneal

elevation and an increase in central corneal thickness were

observed in the postoperative period. However, the scarcity of

corneal sources and shortage of donor sources for corneal

transplantation have not changed for a long time (21). The corneal stromal lenticule is an

anterior layer of tissue in the central region of the corneal

stroma. It is composed of collagen fibres arranged in an orderly

fashion, and its normal anatomical structure and physiological

functions are essential for maintaining corneal transparency and

biomechanics. The excimer laser can cut corneal tissue with high

precision without affecting tissues outside the cut area.

Therefore, this approach is considered safe (22). In the present study, an excimer

laser was used to cut the corneal stromal lenticule, which was

either parallel or concave.

In the present study, an excimer laser was used to

cut three groups of lenticules at ratios of 1:1, 1:1.5 and 1:2. The

optical zone was 4 mm, and the thickness at 1.5 mm from the centre

was within the cutting range. Furthermore, a thickness of 2 mm from

the centre represents the boundary of the cutting zone, with the

lenticule's centre at the centre of cutting. When the three groups

were compared, the differences between the ctc and 1.5 tc among the

three groups were caused by the different cutting ratios. No

differences were observed in the 2tc and 2.5 tc of the three

groups. This finding indicates that thicknesses of 2 and 2.5 mm

were probably not affected by cutting. Because all other conditions

of the three groups were consistent except for the different

cutting ratios, 2tc and 2.5tc were probably only caused by

dehydration. No difference in ct-2t was observed before laser

plastination in the three groups because ct-2t was affected by the

diopters. No differences were observed in the refraction of the

lenticules incorporated into any of the three groups. However, a

significant difference in ct-2t was observed after laser

plastination. One group had a ct-2t of 38 (IQR: 28, 53.5) µm after

laser plasticity, with a distinct convex lenticule at the centre.

The second group had a ct-2t of 6 (IQR, -3, 15.5) µm after laser

plasticity, which was still a convex lenticule in the centre but

was already very close to a parallel lenticule compared with the

two other groups. The third group had a ct-2t of -10 (IQR: -16.5,

-5) µm after laser plasticity, with a distinct concave lenticule at

the centre. This may be because the amount of tissue ablation is

affected by the corneal stromal lenticule, which swells because of

in vitro water absorption (23). This finding shows that excimer

cutting changed the morphology of the centre of the stromal

lenticule. Given the water-absorbing swelling of the stromal

lenticule in vitro, a 1:1.5 ratio of excimer cutting can be

used to obtain a stromal lenticule with a centre close to a

parallel lenticule. Similarly, a 1:2 excimer cutting ratio can be

used to obtain a stromal lenticule with a concave lenticule at the

centre. We hypothesize that this technology can also customize the

corneal stromal lenticule according to the different needs of

patients and then reuse it, thus transforming the traditional

corneal laser surgery from the ‘subtraction’ mode of ‘thinning and

weakening’ to the ‘addition’ mode of ‘thickening and

strengthening’. Additionally, we hypothesize that this

transformation not only provides a new treatment approach for

patients with thin corneal refractive errors, but also opens up new

possibilities for the treatment of corneal diseases. Our

experimental results indicated that the use of excimer

laser-plasticised corneal stromal lenticules for keratoconus

treatment is highly conducive to refractive reconstruction because

it avoids excessive postoperative curvature while adding thickness

to the conical cornea.

However, this study still has certain limitations.

The current research is only confined to in vitro

experiments of corneal stromal lenticules and has not yet conducted

in-depth exploration of the series of changes after their

implantation into the recipient's capsular bag. Whether the corneal

stromal lenticules, after being shaped by excimer laser, can

achieve the ideal refractive correction effect, effectively

increase the biomechanical strength of the cornea and their

long-term stability and biocompatibility in the body all need to be

evaluated through more clinical experiments and long-term

follow-ups. Future research can further study the refractive effect

and biomechanical changes of corneal stromal lenticules after

implantation through animal models or clinical trials; optimize the

cutting parameters by comparing the effects of different cutting

ratios on the microstructure and biomechanical properties of

corneal stromal lenticule; and conduct a comprehensive assessment

of the long-term performance of corneal stromal lenticules in the

body by combining advanced imaging techniques and biomechanical

analysis methods to ensure their safety and effectiveness. These

studies are expected to further improve the corneal stromal

lenticule implantation technique and provide more reliable and

efficient treatment options for refractive and corneal

diseases.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

YL contributed to the study conception and design.

JH, SL, SY, XL and XW acquired and interpreted study data. XW

conducted the statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript. YL

and JH provided critical manuscript revisions and administrative,

technical support. YL supervised the study. XW and YL checked and

confirmed the authenticity of the raw data. All authors have read

and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The study protocol conformed to the tenets of

Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Human Ethics

Committee of Jinan Mingshui Eye Hospital (approval no. Ref.

Ethics/2024/004). Informed consent was obtained in writing from all

adult participants and the guardians of juvenile participants.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Akimoto K, Tsuichihara S, Takamatsu T,

Soga K, Yokota H, Ito M, Gotoda N and Takemura H: Evaluation of

laser-induced plasma ablation focusing on the difference in pulse

duration. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2019:6987–6990.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Reinstein DZ, Archer TJ and Randleman JB:

Mathematical model to compare the relative tensile strength of the

cornea after PRK,LASIK, and small incision lenticule extraction. J

Refract Surg. 29:454–460. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Sun L, Yao P, Li M, Shen Y, Zhao J and

Zhou X: The safety and predictability of implanting autologous

lenticule obtained by SMILE for hyperopia. J Refract Surg.

31:374–379. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Dong Y, Hou J, Zhang J, Lei Y, Yang X and

Sun F: Epithelial thickness remodeling after small incision

lenticule intrastromal keratoplasty in correcting hyperopia

measured by RTVue OCT. BMC Ophthalmol. 24(13)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Wu F, Jin X, Xu Y and Yang Y: Treatment of

corneal perforation with lenticules from small incision lenticule

extraction surgery: A preliminary study of 6 patients. Cornea.

34:658–663. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Jiang Y, Li Y, Liu XW and Xu J: A novel

tectonic keratoplasty with femtosecond laser intrastromal lenticule

for corneal ulcer and perforation. Chin Med J (Engl).

129:1817–1821. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Zhao J, Shang J, Zhao Y, Fu D, Zhang X,

Zeng L, Xu H and Zhou X: Epikeratophakia using small-incision

lenticule extraction lenticule addition combined with corneal

crosslinking for keratoconus. J Cataract Refract Surg.

45:1191–1194. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Wang KN, Fu MJ, Zhao JJ, Wang YC, Wang JH,

Zhang HR and Wang R: Corneal surface mirror (stromal lens)

implantation combined with corneal collagen cross-linking for the

treatment of keratoconus: A case report. J Clin Ophthalmol.

30:552–553. 2022.

|

|

9

|

Sun X, Shen D, Cai J, Zhang CN and Wei W:

A case of keratoconus treated by femtosecond laser assisted

implantation of corneal allogenic matrix lens combined with corneal

collagen crosslinking. Chin J Optom Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 24:472–474.

2022.

|

|

10

|

Ferrari G and Rama P: The keratoconus

enigma: A review with emphasis on pathogenesis. Ocul Surf.

18:363–373. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Wollensak G, Spoerl E and Seiler T:

Riboflavin/ultraviolet-a-induced collagen crosslinking for the

treatment of keratoconus. Am J Ophthalmol. 135:620–627.

2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Padmanabhan P and lsheikh A: Keratoconus:

A biomechanical perspective. Curr Eye Res. 48:121–129.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Wollensak G, Spörl E, Reber F, Pillunat L

and Funk R: Corneal endothelial cytotoxicity of riboflavin/UVA

treatment in vitro. Ophthalmic Res. 35:324–328. 2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Matthyssen S, Van den Bogerd B,

Dhubhghaill SN, Kompen C and Zakaria N: Corneal regeneration: A

review of stromal replacements. Acta Biomater. 69:31–41.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Fasolo A, Galzignato A, Pedrotti E,

Chierego C, Cozzini T, Bonacci E and Marchini G: Femtosecond

laser-assisted implantation of corneal stroma lenticule for

keratoconus. Int Ophthalmol. 41:1949–1957. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Sun X, Zhang H, Shan M, Dong Y, Zhang L,

Chen L and Wang Y: Comprehensive transcriptome analysis of patients

with keratoconus highlights the regulation of immune responses and

inflammatory processes. Front Genet. 13(782709)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Shah SU and Gritz DC: Application of the

femtosecond laser LASIK microkeratome in eye banking. Curr Opin

Ophthalmol. 23:257–263. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Reinstein DZ, Archer TJ and Gobbe M: Small

incision lenticule extraction (SMILE) history, fundamentals of a

new refractive surgery technique and clinical outcomes. Eye Vis

(Lond). 1(3)2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Li M, Yang D, Zhao F, Han T, Li M, Zhou X

and Ni K: Thirty-month results after the treatment of post-LASIK

ectasia with allogenic lenticule addition and corneal

cross-linking: A case report. BMC Ophthalmol.

18(294)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Gao H, Liu M, Li N, Chen T, Qi X, Xie L

and Shi W: Femtosecond laser-assisted minimally invasive lamellar

keratoplasty for the treatment of advanced keratoconus. Clin Exp

Ophthalmol. 50:294–302. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Gain P, Jullienne R, He Z, Aldossary M,

Acquart S, Cognasse F and Thuret G: Global survey of corneal

transplantation and eye banking. JAMA Ophthalmol. 134:167–173.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Laurent JM, Schallhorn SC, Spigelmire JR

and Tanzer DJ: Stability of the laser in situ keratomileusis

corneal flap in rabbit eyes. J Cataract Refract Surg. 32:1046–1051.

2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Wang Q, Rao J, Zhang M, Zhou L, Chen X, Ma

Y, Guo H, Gu J, Wang Y and Zhou Q: SMILE-derived corneal stromal

lenticule: Experimental study as a corneal repair material and drug

carrier. Cornea: Jan 21, 2025 (Epub ahead of print).

|