Introduction

Human telomeres are nucleoprotein structures

consisting of the repeating nucleotide sequence 5'-TTAGGG-3', along

with protein complexes, that interact with the DNA. They are

located at the end of eucaryotic chromosomes, and their main role

is to maintain the stability of chromosomes and their protection

from degradation throughout enzymatic decay (1). Telomeres have been found to be at

their maximum length after birth and as cells divide over time,

they gradually get shorter due to incomplete synthesis of DNA.

After 40-60 cell divisions, they reach a critically short length

known as Hayflick's limit, that triggers cellular senescence and

apoptosis (2,3). To avoid the shortening of telomeres,

human somatic cells produce the enzyme telomerase, which adds

nucleotides at the 3' end of the telomeres, and thus the telomeres

can maintain their length. This enzyme is active in numerous

somatic tissues during fetal and early neonatal development, but

its activity gradually decreases with age, resulting in

inactivation in the somatic cells of adults (4).

Telomere length (TL) is a biomarker of cellular

aging and genomic stability, and is influenced by genetic,

environmental, and physiological factors. TL is known to be

partially inherited and may reflect maternal health and stress

exposures. Preterm birth has been associated with adverse

intrauterine environments, including inflammation, oxidative

stress, and maternal metabolic conditions, all of which may affect

telomere dynamics (4).

Investigating the correlation of TL between mothers and their

neonates, especially comparing full-term and preterm births, may

provide insight into how maternal health and gestational age

influence early-life biological aging.

TL can differ significantly among individuals of the

same age, and this variability is noticeable from birth. During in

utero development, the fetus undergoes crucial phases of cellular

growth, differentiation, and maturation, that cause modifications

in telomere dynamics (5). These

alterations can have far-reaching consequences for an individual's

health and susceptibility to diseases throughout their life

(6). Emerging research suggests

that TL in neonates can also impact the development of age-related

diseases. Shorter telomeres have been associated with increased

risks of cardiovascular diseases, cancer, neurodegenerative

disorders, and other chronic conditions (7-10).

Therefore, it is highly probable that the TL of an individual as

they age is significantly shaped by their TL at birth and the

subsequent attrition of telomeres during early life (11).

The typical duration of a human pregnancy is usually

between 37 to 42 gestational weeks, during which the developing

fetus undergoes cell differentiation and organ maturation,

essential for successful survival outside the womb. In this case,

the TL that neonates are born with has been estimated to be 9 to

12,5 kilobases (12). When the

gestation period is disrupted and childbirth occurs before 37

weeks, childbirth is characterized as premature (13). Preterm birth is a multifactorial

phenomenon that, according to the WHO, ranged from 4 to 16% across

countries in 2020 (https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/preterm-birth).

It is more prevalent among male infants, with ~55% of preterm

births occurring in boys (14),

and mortality rates are also higher among premature boys compared

with premature girls (15).

Multiple pregnancies, obesity, gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM),

alcohol use during pregnancy, and smoking are main maternal factors

that appear to affect preterm birth, and studies have indicated

that these factors can also affect embryonic TL throughout

pregnancy (16-20).

Previous research has revealed that higher maternal pre-pregnancy

body mass index (BMI) is associated with shorter in both mothers

and their infants, indicating increased oxidative stress and

accelerated cellular aging (11).

The purpose of the present study was to investigate

the correlation between neonatal TL and that of their mothers, and

to examine potential differences between preterm and full-term

neonates. Additionally, associations between maternal

characteristics, medical history, and pregnancy-related events with

neonatal TL was assessed.

Materials and methods

Patients and ethics approval

The present study was conducted at the Department of

Neonatology and the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit, University

Hospital of Heraklion (Heraklion, Greece), and at the Laboratory of

Toxicology, Medical School, University of Crete (Heraklion,

Greece). Ethics approval (approval no. 112/08.09.2021) for the

study was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee of the

University of Crete (Heraklion, Greece). Informed consent was

obtained from all participants for both their own participation and

that of their newborns. All participants completed a specialized

questionnaire concerning their medical history, habits during

pregnancy, and anthropometric characteristics. All samples

generated by the present study were anonymized, and personal data

were managed according to the EU General Data Protection Regulation

(GDPR; https://gdpr-info.eu/).

Blood samples were collected from 54 mothers and

their neonates hospitalized at the Department of Neonatology and

Neonatal Intensive Care Unit, University Hospital of Heraklion

(Heraklion, Greece), from October 2022 to February 2023. Genomic

DNA was extracted using the QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit (cat no.

51104; QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer's instructions. All

the samples were measured using a photometer and the necessary

dilutions were made in order to achieve a final DNA concentration

of 5 ng/µl in the working solution. Subsequently, quantitative PCR

was performed to determine the length of the telomeric ends. The

thermocycling conditions were as follows: Initial denaturation at

95˚C for 10 min, denaturation at 95˚C for 20 sec, annealing at 52˚C

for 20 sec, extension at 72˚C for 45 sec with 32 number of cycles

and hold at 20˚C. The total telomere length of the target sample

was calculated as follows: Reference sample telomere length x

2-ΔΔCq (21).

The 2X GoldNStart TaqGreen qPCR Master Mix (cat no.

MB6018a-1; ScienCell Research Laboratories, Inc.) was a

SYBR® Green dye-based qPCR master mix with a ‘hot-start’

property). The single copy reference (SCR) primer set recognizes

and amplifies a 100 bp-long region on rat chromosome 17, and serves

as a reference for data normalization. The kit used was the

Relative Human Telomere Length Quantification qPCR Assay kit and

the primers were part of the kit (cat. no. 8918; ScienCell Research

Laboratories, Inc.). The telomere length was calculated based on

the instructions of the kit.

Statistical analysis

Data mainly consisted of qualitative data and were

expressed as counts and frequencies. Numerical variables were

expressed as means and standard deviation. Pearson's χ2

was used to associate discrete (qualitative) data, while Pearson's

r or Spearman's ρ coefficient was used to correlate continuous

variables. Independent samples t-tests were applied to continuous

variables to examine possible differences between two groups, while

one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by LSD post-hoc test,

was applied for differences in more than two groups. IBM SPSS

Statistics 24.0 (IBM Corp.) was used for analysis, and an a=0.05

was set as the significance level.

Results

Maternal and neonatal characteristics

and TL correlations

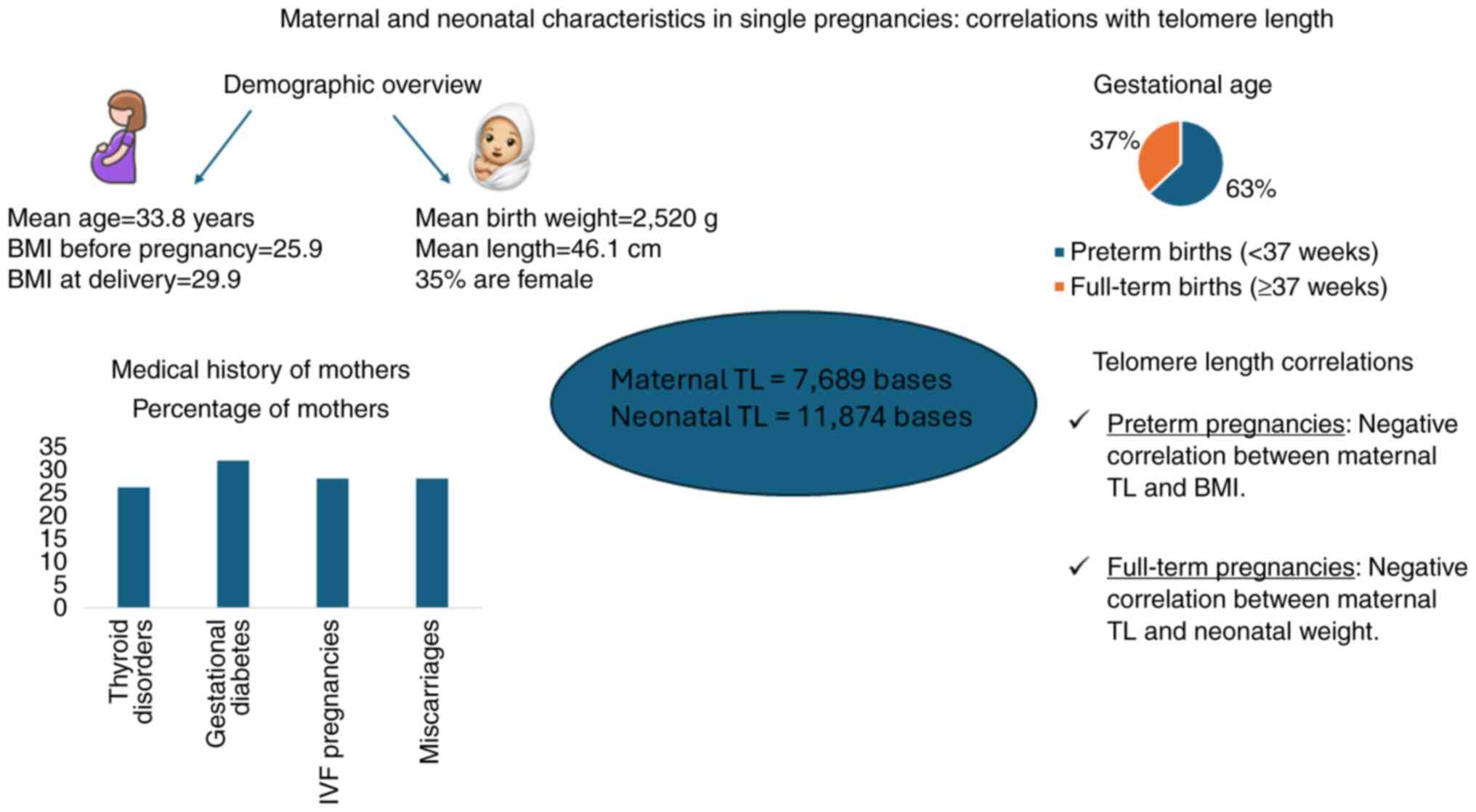

A total of 54 neonates, resulting from single

pregnancies, were included in the present study. Demographic

characteristics of participating mothers are presented in Table I. The mean maternal age was

33.8±6.1 years, ranging from 19 to 50 years. The mean BMI increased

from from 25.9±6.0 before pregnancy to 29.9±5.8 at delivery. The

medical history of the mothers is described in Table II. A total of 39 mothers (72.2%)

stated that they had not experienced a miscarriage in the past,

while the rest of them had at least one (27.8%). Thyroid disorders

were observed in 14 (25.9%) of the examined mothers. In addition,

17 (31.5%) of the mothers developed gestational diabetes. In

vitro fertilization (IVF) was performed for 27.8% of the total

pregnancies. Gestational age was #x003C;37 weeks in 63.0% of all

pregnancies (Table III).

| Table IDemographic and somatometric

characteristics of participating mothers. |

Table I

Demographic and somatometric

characteristics of participating mothers.

| Variable | Mean | ± SD | Median | Min | Max |

|---|

| Age (years) | 33.8 | 6.1 | 33.5 | 19 | 50 |

| Height (cm) | 166.1 | 5.3 | 166.0 | 147 | 176 |

| Weight before

(kg) | 71.7 | 17.8 | 67.0 | 47 | 133 |

| Weight at delivery

(kg) | 82.5 | 16.8 | 78.5 | 58.0 | 128 |

| BMI before

(kg/m2) | 25.9 | 6.0 | 24.2 | 18.1 | 45.6 |

| BMI at delivery

(kg/m2) | 29.9 | 5.8 | 28.7 | 21.4 | 50.2 |

| Table IIMedical history of the mothers. |

Table II

Medical history of the mothers.

| Maternal medical

history | n | Percentage (%) |

|---|

| Μiscarriage | 15 | 27.8 |

| Thyroid

disorders | 14 | 25.9 |

| Gestational

diabetes | 17 | 31.5 |

| Polycystic

ovaries | 6 | 11.1 |

| Cushing

syndrome | 1 | 1.9 |

| Hypertension | 1 | 1.9 |

| Table IIIPregnancy characteristics. |

Table III

Pregnancy characteristics.

| Pregnancy-related

variables | N | Percentage (%) |

|---|

| IVF | 15 | 27.8 |

| Gestational

age | | |

|

Gestational

weeks #x003C;37 | 34 | 63.0 |

|

Gestational

weeks ≥37 | 20 | 37.0 |

The mean length of newborns was 46.1±5.4 cm, ranging

from 28 to 55 cm. The mean weight of the neonates was 2.520±842 g,

ranging from 600 to 4,180 g, and the mean BMI of the neonates was

11.4±1.9 kg/m2, ranging from 6.7 to 14.3

kg/m2. Only 19 (35.2%) of the neonates included were

females (Table IV). Notably, the

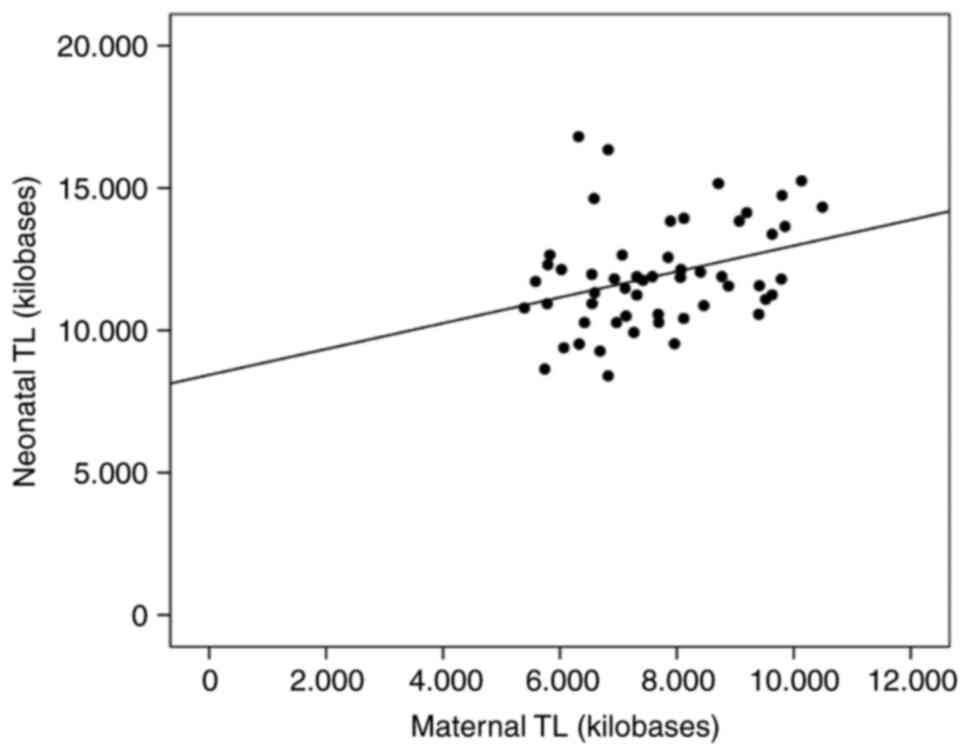

maternal mean TL was estimated at 7,689±1,528 bases, while the

neonate TL was in the range of 11,874±1,787 bases. A weak to

moderate significant correlation was observed between maternal and

neonatal TL (Spearman's ρ=0.323; P=0.017) (Fig. 1).

| Table IVCharacteristics of neonates. |

Table IV

Characteristics of neonates.

| At birth | Mean | Median | ± SD | Min | Max |

|---|

| Length (cm) | 46.1 | 47.0 | 5.4 | 28.0 | 55.0 |

| Birth weight

(g) | 2,520 | 2,590 | 842 | 600 | 4,180 |

| BMI

(kg/m2) | 11.4 | 11.6 | 1.9 | 6.7 | 14.3 |

Μaternal TL was negatively correlated with BMI

before pregnancy (r=-0.285; P=0.037), while a statistically

significant trend was also observed with maternal BMI at delivery

(r=0.251; P=0.067; 0.05#x003C;P#x003C;0.100) was observed.

Similarly, a trend towards significance was found between maternal

TL and weight before pregnancy (r=-0.229; P=0.096; 0.05#x003C;

P#x003C;0.100). No significant correlations were observed between

maternal TL and neonatal somatometrics and sex (Table V).

| Table VCorrelation of maternal and neonatal

TL with maternal and neonatal somatometrics. |

Table V

Correlation of maternal and neonatal

TL with maternal and neonatal somatometrics.

| | Maternal TL | Neonatal TL |

|---|

| Somatometrics | r | P-value | r | P-value |

|---|

| Mother | | | | |

|

Age | 0.126 | 0.364 | 0.083 | 0.550 |

|

Height

(cm) | -0.077 | 0.582 | -0.165 | 0.234 |

|

Weight

before pregnancy (kg) | -0.229 | 0.096 | -0.123 | 0.375 |

|

Weight

during pregnancy (kg) | -0.179 | 0.178 | -0.087 | 0.516 |

|

BMI (before

pregnancy) | -0.285 | 0.037 | -0.091 | 0.515 |

|

BMI (at

delivery) | -0.251 | 0.067 | -0.002 | 0.990 |

| Neonate | | | | |

|

Height

(cm) | -0.053 | 0.709 | -0.060 | 0.673 |

|

Weight

(kg) | -0.037 | 0.793 | -0.127 | 0.368 |

|

BMI

(kg/m2) | 0.023 | 0.874 | -0.120 | 0.397 |

|

Sex | -0.088 | 0.525 | -0.004 | 0.979 |

Neonatal TL was not correlated with maternal age,

maternal somatometric measures, neonatal somatometric measures or

sex.

The effect of maternal smoking habits and diseases

on neonates TL are presented in Table

VI. There was no significant effect of smoking before pregnancy

(P=0.892), smoking during pregnancy (P=0.724), history of

miscarriage (P=0.488), type of conception (P=0.770), thyroid

disorders (hyperthyroidism, P=0.153 and hypothyroidism, P=0.971),

gestational diabetes (P=0.974) and gestational age at term

(P=0.867) on neonatal TL. No significant differences were found

between maternal TL and medical or gestational history.

| Table VIAssociation between neonatal TL and

maternal smoking habits and medical history. |

Table VI

Association between neonatal TL and

maternal smoking habits and medical history.

| | | No | | Yes | |

|---|

| Neonate TL | n | Mean | SD | n | Mean | SD | P-value |

|---|

| Smoking before

pregnancy | 37 | 11.896 | 1.723 | 17 | 11.971 | 2.199 | 0.892 |

| Smoking during

pregnancy | 45 | 11.961 | 1.806 | 9 | 11.717 | 2.247 | 0.724 |

| Miscarriages | 39 | 12.123 | 1.972 | 15 | 11.698 | 1.603 | 0.488 |

| Thyroid

disorders | 40 | 11.992 | 2.038 | 14 | 11.715 | 1.285 | 0.637 |

|

Hyperthyroidism | 53 | 11.970 | 1.846 | 1 | 11.970 | 1.846 | 0.153 |

| Hypothyroidism | 41 | 11.925 | 2.057 | 13 | 11.903 | 1.119 | 0.971 |

| Gestational

diabetes | 37 | 11.958 | 1.915 | 17 | 11.837 | 1.805 | 0.974 |

| Full-term pregnancy

(≥37 weeks) | 34 | 11.953 | 1.871 | 20 | 11.864 | 1.900 | 0.867 |

| IVF conception | 38 | 11.954 | 1.978 | 15 | 11.784 | 1.661 | 0.770 |

Analysis between preterm and full-term

groups

This section presents the analysis of maternal and

neonate TL in relation to demographics, medical history and other

variables comparing preterm and full-term infants. In preterm

pregnancies #x003C;37 weeks, maternal TL showed a statistically

significant negative correlation with BMI before pregnancy

(r=-0.403; P=0.018) and BMI after pregnancy (r=-0.349; P=0.043). A

trend towards significance was observed between maternal TL and

pre-pregnancy weight (r=-0.313; P=0.072). No significant

associations were found between maternal TL and neonate variables

(P>0.100) in preterm pregnancies. Similarly, neonatal TL did not

show any significant correlations with maternal or neonatal

parameters (P>0.100).

In full-term pregnancies (gestational age, ≥37),

maternal TL was significantly correlated with neonatal weight after

delivery (r=-0.505; P=0.039), while a trend towards significance

was also observed between maternal TL with neonatal height

(0.05#x003C; P#x003C;0.100). No significant correlations were found

between neonatal TL and any of the measured maternal or neonatal

variables in full-term pregnancies (Table VII).

| Table VIICorrelation of maternal and neonatal

TL with maternal somatometric variables in preterm and full-term

pregnancies. |

Table VII

Correlation of maternal and neonatal

TL with maternal somatometric variables in preterm and full-term

pregnancies.

| | Preterm pregnancy

(#x003C;37 weeks) | Full-term pregnancy

(≥37 weeks) |

|---|

| Variables | Maternal TL r | Neonatal TL r | Maternal TL r | Neonatal TL r |

|---|

| Mother | | | | |

|

Age

(year) | 0.202 | 0.018 | -0.049 | 0.185 |

|

Height

(cm) | 0.029 | -0.018 | -0.274 | -0.408a |

|

Weight

before pregnancy (kg) | -0.313a | -0.161 | -0.104 | -0.156 |

|

Weight

during pregnancy (kg) | -0.281 | -0.120 | -0.051 | 0.018 |

|

BMI before

pregnancy (kg/m2) | -0.403b | -0.166 | -0.143 | -0.051 |

|

BMI after

pregnancy (kg/m2) | -0.349b | -0.105 | -0.164 | 0.149 |

| Neonate | | | | |

|

Height

(cm) | 0.133 | -0.077 | -0.462a | -0.116 |

|

Weight

(g) | -0.048 | -0.132 | -0.505b | -0.308 |

|

BMI

(kg/m2) | 0.053 | 0.038 | 0.156 | -0.374 |

|

Sex | -0.253 | -0.103 | 0.230 | 0.142 |

In addition, no significant differences in maternal

and neonatal TL were observed between preterm and full-term

pregnancies based on history of miscarriage, smoking habits,

thyroid disorders, mode of conception and gestational diabetes

(Table VIII).

| Table VIIIAssociation of maternal and neonatal

TL with smoking status, maternal medical history, and pregnancy

characteristics in preterm and full-term pregnancies. |

Table VIII

Association of maternal and neonatal

TL with smoking status, maternal medical history, and pregnancy

characteristics in preterm and full-term pregnancies.

| A, Preterm

pregnancy |

|---|

| | | Maternal TL | | Neonatal TL | |

|---|

| Variables | Yes/No | Mean | ± SD | P-value | Mean | ± SD | P-value |

|---|

| Abortions | No | 7.929 | 1.344 | 0.243 | 12.064 | 2.068 | 0.744 |

| | Yes | 7.334 | 1.548 | | 11.722 | 1.437 | |

| Smoking before

pregnancy | No | 7.694 | 1.429 | 0.772 | 12.029 | 1.784 | 0.885 |

| | Yes | 7.826 | 1.458 | | 11.795 | 2.125 | |

| Smoking during

pregnancy | No | 7.753 | 1.439 | >0.999 | 11.953 | 2.054 | 0.947 |

| | Yes | 7.660 | 1.442 | | 11.975 | 1.336 | |

| Thyroid

disorders | No | 7.832 | 1.435 | 0.645 | 11.945 | 2.054 | 0.673 |

| | Yes | 7.472 | 1.417 | | 11.975 | 1.336 | |

| Conception | Normal | 7.814 | 1.618 | 0.813 | 12.002 | 2.005 | 0.598 |

| | IVF | 7.791 | 1.457 | | 11.824 | 1.791 | |

| Gestational

diabetes | No | 7.984 | 1.355 | 0.204 | 12.075 | 1.952 | 0.817 |

| | Yes | 7.282 | 1.476 | | 11.730 | 1.774 | |

| B, Full-term

pregnancy |

| | | Maternal TL | | Neonatal TL | |

| Variables | Yes/No | Mean | ± SD | P-value | Mean | ± SD | P-value |

| Miscarriages | No | 7.477 | 1.291 | 0.622 | 12.220 | 1.874 | 0.179 |

| | Yes | 8.230 | 1.180 | | 11.033 | 1.846 | |

| Smoking before

pregnancy | No | 7.823 | 1.388 | 0.274 | 11.679 | 1.658 | 0.659 |

| | Yes | 7.000 | 941 | | 12.296 | 2.501 | |

| Smoking during

pregnancy | No | 7.557 | 1.403 | 0.765 | 11.973 | 1.873 | 0.616 |

| | Yes | 7.683 | 623 | | 11.247 | 2.359 | |

| Thyroid

disorders | No | 7.487 | 1.354 | 0.612 | 12.069 | 2.080 | 0.612 |

| | Yes | 7.842 | 1.245 | | 11.247 | 1.170 | |

| Pregnancy | Normal | 7.500 | 1.298 | 0.442 | 11.902 | 2.005 | 0.674 |

| | IVF | 8.263 | 1.623 | | 11.525 | 64 | |

| Gestational

diabetes | No | 7.542 | 1.240 | 0.933 | 11.787 | 1.913 | 0.612 |

| | Yes | 7.676 | 1.639 | | 12.094 | 2.064 | |

Discussion

The present study highlighted a weak to moderate,

positive and statistically significant correlation between maternal

and neonatal TL, irrespective of full-term or preterm pregnancy.

Some maternal features, particularly BMI before pregnancy, appeared

to be the determinant factor in maternal TL. Additionally, grouping

cases into preterm or full-term neonates influenced some of the

findings; however, no statistically significant associations were

observed between neonatal TL and maternal characteristics, medical

history, and pregnancy details (Fig.

2).

The mean maternal TL in the present study fell

within the reference range of 7 to 9 kilobases for women in their

30s (22), consistent with the

mean maternal age in our sample. For neonates, the TL was predicted

to fall within 8 to 11 kilobases (22). Most of the neonates examined were

preterm and the slightly higher mean TL, supports a previous

observation that preterm neonates tend to have longer telomeres

than those born at term (23).

A study involving 319 mother-newborn pairs found a

significant positive association between maternal and newborn TLs

(β=0.31; P#x003C;0.001), indicating that maternal TL is a predictor

of neonatal TL (24). Research has

shown that preterm infants have significantly longer telomeres than

their term-born counterparts. Specifically, TL was negatively

correlated with gestational age and birth weight in preterm infants

(25). In a cohort of African

American women, shorter maternal peripheral blood TL was associated

with an increased risk of preterm birth. Notably, for every 10-unit

decrease in the telomere-to-single-copy gene (T/S) ratio, the odds

of preterm birth increased by a factor of 2.664(26).

Previous studies did not directly correlate maternal

BMI with the TL of neonates, in contrast to most previous studies

(11,27). Indeed, prior research has

identified a negative correlation between maternal BMI and neonatal

TL (11). At the molecular level,

elevated maternal BMI may promote oxidative stress and inflammation

in the fetal environment, which could contribute to telomere

shortening during prenatal development (28-30).

Additionally, neonatal telomere shortening was more likely to occur

in infants born to mothers with higher anxiety scores, elevated

fasting blood glucose levels, lower levels of plasma insulin-like

growth factor-binding protein 3 (IGFBP-3) and vitamin B12, and who

actively smoke status pregnancy (27). However, there are studies which

support that a high maternal pre-pregnancy BMI is associated with

shorter maternal TL and TL in infants, indicating increased

oxidative stress and accelerated cellular aging (31,32).

The lack of association between maternal BMI and

neonatal TL contrasts with previous studies (11,27),

potentially due to the BMI distribution in this cohort, which

consisted primarily of normal-weight participants. Additionally,

the variability in qPCR protocols, along with factors such as

maternal stress, smoking, or nutrition, which can modulate TL

independently of BMI, may confound results. Furthermore, limited

statistical power and sample size may lack the statistical power to

detect subtle associations (33,34).

Pre-pregnancy maternal BMI was not correlated with

neonatal TL as expected but has been found to be related to preterm

birth, and the present study aligns with this indication (P=0.017)

(Fig. 1). Preterm deliveries

resulting from premature labor with cervical dilation or early

rupture of membranes are categorized as ‘spontaneous’, while those

that are induced or carried out via cesarean section, due to

maternal or fetal health concerns, are termed ‘indicated’ preterm

births. In the present study, the type of preterm delivery was not

provided. Most mothers who participated were categorized as

οverweight (BMI between 25 and 30; mean BMI, 26) prior to

pregnancy, which could also justify why a significant correlation

with neonatal TL was not observed. However, the sample did include

individuals from both the underweight and overweight categories,

with BMIs ranging from 18.1 to 45.6. Previous studies have found

that maternal overweight is more commonly associated with medically

indicated preterm births, whereas maternal underweight tends to

slightly increase the risk of spontaneous preterm labor (35). The exact mechanisms by which

abnormal maternal BMI affects neonatal TL are not fully understood,

although these effects may be linked to chronic inflammation and

oxidative stress during fetal development (30). Moving forward, this research is

planned to be expanded by categorizing participants into different

BMI groups. Through this approach, further exploration into how

maternal BMI may influence preterm deliveries is expected to be

conducted, possibly revealing novel insights into its effects on

fetal genotypic outcomes.

When mothers were examined separately, a moderate

negative correlation between pre-pregnancy maternal BMI and

maternal TL was observed (P=0.037). Previous research has examined

the correlation between maternal BMI and TL. For instance, adult

women with a BMI exceeding 30 kg/m2, had telomeres that

were on average, 240 base pairs shorter compared with women with a

BMI below 20 kg/m2, and this difference was equivalent

to an aging effect of ~8.8 years (36).

Finally, no evidence of a the relationship between

maternal pregnancy complications and neonatal TL was revealed in

the present study. This finding appears to be consistent with

recent data showing that maternal stress does not exert a

significant effect on infant TL of infants as determined by qPCR

analysis (37). Currently, the

results of the present study appear to contradict previous findings

supporting that maternal pregnancy complications can contribute to

neonatal telomere shortening (5,24,38-40).

The discrepancies among studies can be attributed to the small

sample size in previous studies. Indeed, numerous detrimental

variables (such as oxidative stress, inflammation, and other

genetic/epigenetic, immunological, physiological, lifestyle, and

environmental factors, including nutrition) have been shown to

result in an advanced aging trajectory and exacerbate placental

dysfunction, given that TL reflects the cumulative impact of

stressors (41,42). In addition, several pregnancy

complications, such as GDM, intrauterine growth restriction,

hypertensive disorders and preeclampsia, have been demonstrated to

be associated with prematurity and neonatal telomere alterations

while still in utero (43,44). In the majority of studies, GDM has

been associated with reduced neonatal telomeres (45-49),

although some other studies have found similar TLs (43,44,50)

or even longer ones in newborns compared with those from mothers

without GDM (51). Cardiovascular

conditions such as hypertension and preeclampsia have also been

associated with shorter telomeres in previous research, although

the mechanisms remain unclear (52). The small sample size in the present

study limited the ability to assess how pregnancy complications and

lifestyle factors (such as alcohol consumption and smoking) affect

neonatal TL, and future studies with larger participant pools are

required to address these gaps.

Even though a correlation between maternal and

neonatal TL was identified in the present study, it has several

limitations. Initially, qPCR was used to evaluate relatively

average TL, although this technique has been considered more

variable than the classically used terminal restriction fragment

analysis (53,54). Secondly, evaluating TL in neonates

represents only a snapshot of aging at birth, as limited data are

available on TL in embryos during pregnancy and childhood.

Indeed, the qPCR method was used to assess maternal

and neonatal TL, as only 200 µl of neonatal blood, obtained from

the complete blood count, was available for analysis. The collected

blood from preterm or full-term neonates was of invaluable and

utmost importance since neonate samples are unique, especially that

of preterm neonates. It is worth noting that the acquisition of

increased blood amounts can result in the reduction of neonatal

hematocrit (55). However, the

present study did not detect TL differences across chromosomes at a

single-cell level, which can be accomplished through metaphase

Q-FISH (56,57). The Q-FISH technique can provide an

overall analysis of TL distributions, providing measurements for

extremely short or extremely long telomeres at the chromosome level

(57). Despite this limitation,

the present study provides unique insight into the average TL of

maternal and full-term or preterm neonates. A limitation was also

noted due to the small sample size, which affects the statistical

power of sample. However, numerous studies have confirmed the

reproducibility of the qPCR method in neonatal samples (58-60).

Another challenge of the study was the limited

sample size. In most cases, there was also an insufficient number

of participants diagnosed with some of the examined disorders

within the timeframe of sample collection. Due to the shortcoming

of the sample size, a general overview of neonatal TL in relation

to maternal characteristics could not be provided. Therefore,

future studies with a more substantial and diverse participant pool

are encouraged to validate and strengthen the conclusions derived

from the present research.

In conclusion, the present study revealed a weak to

moderate, positive and statistically significant correlation

between maternal and neonatal TL, regardless of pregnancy duration.

No significant differences were observed between maternal TL and

maternal habits, medical history, or gestational history. However,

maternal BMI before pregnancy appears to have a decisive impact on

determining maternal TL. Future studies with a larger sample size

and the inclusion of additional parameters, such as socioeconomic

status, maternal stress levels, and environmental exposures, are

recommended to further clarify these associations.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

EV, EH, AT and DAS conceived the study. EV, MT and

PF acquired and interpreted the data of the study. EM, ZV, NA and

FM designed the study. AA, PI, SB, AM, NIP, MTV, TL, EV and AT

analyzed the data of the study and were major contributors in the

writing of the manuscript. AT and AA confirm the authenticity of

all the raw data. EV, EH and AT, provided final approval of the

version to be published. All authors have read and agreed to the

published version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Ethics approval (approval no. 112/08.09.2021) for

the study was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee of the

University of Crete (Heraklion, Crete). Informed consent was

obtained from all participants for both their participation and

that of their newborns. All participants completed a specialized

questionnaire concerning their medical history, habits during

pregnancy, and anthropometric characteristics. All samples

generated by the present study were anonymized, and personal data

were managed according to the EU General Data Protection Regulation

(GDPR; https://gdpr-info.eu/).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

DAS is the editor-in-chief for the journal, but had

no personal involvement in the reviewing process, or any influence

in terms of adjudicating on the final decision, for this article.

The other authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Blackburn EH: Structure and function of

telomeres. Nature. 350:569–573. 1991.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Hayflick L and Moorhead PS: The serial

cultivation of human diploid cell strains. Exp Cell Res.

25:585–621. 1961.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Bartlett Z: The hayflick limit. Embryo

Project Encyclopedia, 2014. http://embryo.asu.edu/handle/10776/8237.

|

|

4

|

Gomes NM, Shay JW and Wright WE: Telomere

biology in Metazoa. FEBS Lett. 584:3741–3751. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Entringer S, de Punder K, Buss C and

Wadhwa PD: The fetal programming of telomere biology hypothesis: An

update. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci.

373(20170151)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Entringer S, Buss C and Wadhwa PD:

Prenatal stress and developmental programming of human health and

disease risk: Concepts and integration of empirical findings. Curr

Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 17:507–516. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Yeh JK and Wang CY: Telomeres and

telomerase in cardiovascular diseases. Genes (Basel).

7(58)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Okamoto K and Seimiya H: Revisiting

telomere shortening in cancer. Cells. 8(107)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Levstek T, Kozjek E, Dolžan V and Trebušak

Podkrajšek K: Telomere attrition in neurodegenerative disorders.

Front Cell Neurosci. 14(219)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Gruber HJ, Semeraro MD, Renner W and

Herrmann M: Telomeres and age-related diseases. Biomedicines.

9(1335)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Martens DS, Plusquin M, Gyselaers W, De

Vivo I and Nawrot TS: Maternal pre-pregnancy body mass index and

newborn telomere length. BMC Med. 14(148)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Okuda K, Bardeguez A, Gardner JP,

Rodriguez P, Ganesh V, Kimura M, Skurnick J, Awad G and Aviv A:

Telomere length in the newborn. Pediatr Res. 52:377–381.

2002.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Samuel TM, Sakwinska O, Makinen K, Burdge

GC, Godfrey KM and Silva-Zolezzi I: Preterm birth: A narrative

review of the current evidence on nutritional and bioactive

solutions for risk reduction. Nutrients. 11(1811)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Haghighi L, Najmi Z, Barzegar SH and

Barzegar N: Twin's sex and risk of pre-term birth. J Obstet

Gynaecol. 33:823–826. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Kent AL, Wright IM and Abdel-Latif ME: New

South Wales and Australian Capital Territory Neonatal Intensive

Care Units Audit Group. Mortality and adverse neurologic outcomes

are greater in preterm male infants. Pediatrics. 129:124–131.

2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Monden C, Pison G and Smits J: Twin peaks:

More twinning in humans than ever before. Hum Reprod. 36:1666–1673.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Buchanan TA, Xiang AH and Page KA:

Gestational diabetes mellitus: Risks and management during and

after pregnancy. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 8:639–649. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Hawthorne G: Maternal complications in

diabetic pregnancy. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 25:77–90.

2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

McCarthy FP, O'Keeffe LM, Khashan AS,

North RA, Poston L, McCowan LME, Baker PN, Dekker GA, Roberts CT,

Walker JJ and Kenny LC: Association between maternal alcohol

consumption in early pregnancy and pregnancy outcomes. Obstet

Gynecol. 122:830–837. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Shah NR and Bracken MB: A systematic

review and meta-analysis of prospective studies on the association

between maternal cigarette smoking and preterm delivery. Am J

Obstet Gynecol. 182:465–472. 2000.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408.

2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Factor-Litvak P, Susser E, Kezios K,

McKeague I, Kark JD, Hoffman M, Kimura M, Wapner R and Aviv A:

Leukocyte telomere length in newborns: Implications for the role of

telomeres in human disease. Pediatrics.

137(e20153927)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Colatto BN, de Souza IF, Schinke LAA,

Noda-Nicolau NM, da Silva MG, Morceli G, Menon R and Polettini J:

Telomere length and telomerase activity in foetal membranes from

term and spontaneous preterm births. Reprod Sci. 27:411–417.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Send TS, Gilles M, Codd V, Wolf I, Bardtke

S, Streit F, Strohmaier J, Frank J, Schendel D, Sütterlin MW, et

al: Telomere length in newborns is related to maternal stress

during pregnancy. Neuropsychopharmacology. 42:2407–2413.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Vasu V, Turner KJ, George S, Greenall J,

Slijepcevic P and Griffin DK: Preterm infants have significantly

longer telomeres than their term born counterparts. PLoS One.

12(e0180082)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Huang W, Han G, Taylor BD, Neal G, Kochan

K and Page RL: Maternal peripheral blood telomere length and

preterm birth in African American women: A pilot study. Arch

Gynecol Obstet. 311:1591–1598. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Wei B, Shao Y, Liang J, Tang P, Mo M, Liu

B, Huang H, Tan HJJ, Huang D, Liu S and Qiu X: Maternal overweight

but not paternal overweight before pregnancy is associated with

shorter newborn telomere length: Evidence from Guangxi Zhuang birth

cohort in China. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 21(283)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Malti N, Merzouk H, Merzouk SA, Loukidi B,

Karaouzene N, Malti A and Narce M: Oxidative stress and maternal

obesity: Feto-placental unit interaction. Placenta. 35:411–416.

2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Myatt L: Placental adaptive responses and

fetal programming. J Physiol. 572:25–30. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Maugeri A, Magnano San Lio R, La Rosa MC,

Giunta G, Panella M, Cianci A, Caruso MAT, Agodi A and Barchitta M:

The relationship between telomere length and gestational weight

gain: Findings from the mamma & bambino cohort. Biomedicines.

10(67)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Barchitta M, Maugeri A, La Mastra C,

Favara G, La Rosa MC, Magnano San Lio R, Gholizade Atani Y, Gallo G

and Agodi A: Pre-pregnancy BMI, gestational weight gain, and

telomere length in amniotic fluid: a causal graph analysis. Sci

Rep. 8(14(1):23396)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Martens D. S..Plusquin M..Gyselaers W..De

Vivo I..Nawrot T. S: Maternal pre-pregnancy body mass index and

newborn telomere length. BMC Medicine. 14(1)(148)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Lame-Jouybari AH, Fahami MS, Hosseini MS,

Moradpour M, Hojati A and Abbasalizad-Farhangi M: Association

between maternal prepregnancy and pregnancy body mass index and

children's telomere length: A systematic review and meta-analysis.

Nutr Rev. 83:622–635. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Vahter M, Broberg K and Harari F:

Placental and cord blood telomere length in relation to maternal

nutritional status. J Nutr. 150:2646–2655. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Liu Y and Gao L: Preterm labor, a syndrome

attributed to the combination of external and internal factors.

Matern Fetal Med. 4:61–71. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Valdes AM, Andrew T, Gardner JP, Kimura M,

Oelsner E, Cherkas LF, Aviv A and Spector TD: Obesity, cigarette

smoking, and telomere length in women. Lancet. 366:662–664.

2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Ämmälä AJ, Vitikainen EIK, Hovatta I,

Paavonen J, Saarenpää-Heikkilä O, Kylliäinen A, Pölkki P,

Porkka-Heiskanen T and Paunio T: Maternal stress or sleep during

pregnancy are not reflected on telomere length of newborns. Sci

Rep. 10(13986)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Salihu HM, King LM, Nwoga C, Paothong A,

Pradhan A, Marty PJ, Daas R and Whiteman VE: Association between

maternal-perceived psychological stress and fetal telomere length.

South Med J. 109:767–772. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Marchetto NM, Glynn RA, Ferry ML, Ostojic

M, Wolff SM, Yao R and Haussmann MF: Prenatal stress and newborn

telomere length. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 215:94.e1–e8. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Xu J, Ye J, Wu Y, Zhang H, Luo Q, Han C,

Ye X, Wang H, He J, Huang H, et al: Reduced fetal telomere length

in gestational diabetes. PLoS One. 9(e86161)2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Manna S, McCarthy C and McCarthy FP:

Placental ageing in adverse pregnancy outcomes: Telomere

shortening, cell senescence, and mitochondrial dysfunction. Oxid

Med Cell Longev. 2019(3095383)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Menon R, Boldogh I, Hawkins HK, Woodson M,

Polettini J, Syed TA, Fortunato SJ, Saade GR, Papaconstantinou J

and Taylor RN: Histological evidence of oxidative stress and

premature senescence in preterm premature rupture of the human

fetal membranes recapitulated in vitro. Am J Pathol. 184:1740–1751.

2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Sultana Z, Maiti K, Dedman L and Smith R:

Is there a role for placental senescence in the genesis of

obstetric complications and fetal growth restriction? Am J Obstet

Gynecol. 218 (2S):S762–S773. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Ferrari F, Facchinetti F, Saade G and

Menon R: Placental telomere shortening in stillbirth: A sign of

premature senescence? J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 29:1283–1288.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Liu S, Xu L, Cheng Y, Liu D, Zhang B, Chen

X and Zheng M: Decreased telomerase activity and shortened telomere

length in infants whose mothers have gestational diabetes mellitus

and increased severity of telomere shortening in male infants.

Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 15(1490336)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Hjort L, Vryer R, Grunnet LG, Burgner D,

Olsen SF, Saffery R and Vaag A: Telomere length is reduced in 9- to

16-year-old girls exposed to gestational diabetes in utero.

Diabetologia. 61:870–880. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Garcia-Martin I, Penketh RJA, Janssen AB,

Jones RE, Grimstead J, Baird DM and John RM: Metformin and insulin

treatment prevent placental telomere attrition in boys exposed to

maternal diabetes. PLoS One. 13(e0208533)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Pérez-López FR, López-Baena MT,

Ulloque-Badaracco JR and Benites-Zapata VA: Telomere length in

patients with gestational diabetes mellitus and normoglycemic

pregnant women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Reprod Sci.

31:45–55. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Maeda S, Ohno K, Uchida K, Igarashi H,

Goto-Koshino Y, Fujino Y and Tsujimoto H: Intestinal

protease-activated receptor-2 and fecal serine protease activity

are increased in canine inflammatory bowel disease and may

contribute to intestinal cytokine expression. J Vet Med Sci.

76:1119–1127. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Gilfillan C, Naidu P, Gunawan F, Hassan F,

Tian P and Elwood N: Leukocyte telomere length in the neonatal

offspring of mothers with gestational and pre-gestational diabetes.

PLoS One. 11(e0163824)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Gielen M, Hageman G, Pachen D, Derom C,

Vlietinck R and Zeegers MP: Placental telomere length decreases

with gestational age and is influenced by parity: A study of third

trimester live-born twins. Placenta. 35:791–796. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Tellechea M, Gianotti TF, Alvariñas J,

González CD, Sookoian S and Pirola CJ: Telomere length in the two

extremes of abnormal fetal growth and the programming effect of

maternal arterial hypertension. Sci Rep. 5(7869)2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Kimura M, Stone RC, Hunt SC, Skurnick J,

Lu X, Cao X, Harley CB and Aviv A: Measurement of telomere length

by the Southern blot analysis of terminal restriction fragment

lengths. Nat Protoc. 5:1596–1607. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Aviv A, Hunt SC, Lin J, Cao X, Kimura M

and Blackburn E: Impartial comparative analysis of measurement of

leukocyte telomere length/DNA content by Southern blots and qPCR.

Nucleic Acids Res. 39(e134)2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Davenport P and Sola-Visner M: Hemostatic

challenges in neonates. Front Pediatr. 9(627715)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Gutierrez-Rodrigues F, Santana-Lemos BA,

Scheucher PS, Alves-Paiva RM and Calado RT: Direct comparison of

flow-FISH and qPCR as diagnostic tests for telomere length

measurement in humans. PLoS One. 9(e113747)2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Tsatsakis A, Tsoukalas D, Fragkiadaki P,

Vakonaki E, Tzatzarakis M, Sarandi E, Nikitovic D, Tsilimidos G and

Alegakis AK: Developing BIOTEL: A semi-automated spreadsheet for

estimating telomere length and biological age. Front Genet.

10(84)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

58

|

Chen L, Tan KML, Gong M, Chong MFF, Tan

KH, Chong YS, Meaney MJ, Gluckman PD, Eriksson JG and Karnani N:

Variability in newborn telomere length is explained by inheritance

and intrauterine environment. BMC Med. 20(20)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

59

|

Wang C, Alfano R, Reimann B, Hogervorst J,

Bustamante M, De Vivo I, Plusquin M, Nawrot TS and Martens DS:

Genetic regulation of newborn telomere length is mediated and

modified by DNA methylation. Front Genet. 13(934277)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

60

|

Daneels L, Martens DS, Arredouani S,

Billen J, Koppen G, Devlieger R, Nawrot TS, Ghosh M, Godderis L and

Pauwels S: Maternal vitamin D and newborn telomere length.

Nutrients. 13(2012)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|