Introduction

Primary salivary gland-type lung tumours are rare,

accounting for <1% of all primary lung carcinomas (1,2).

These tumours are thought to originate from glands in the submucosa

of the lower respiratory tract (3); therefore, they usually present as a

central space-occupying lung mass extending into the bronchus

(4). These tumours exhibit the

same histological variability as salivary gland tumours and are

therefore classified according to the World Health Organization

(WHO) criteria for salivary gland tumours (2). The most common histological subtype

of primary salivary gland lung tumours is mucoepidermoid carcinoma,

followed by adenoid cystic carcinoma (5). Primary pulmonary

epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma (P-EMC) is a rare and much less

common tumour that has been recognized only within the last 2

decades (6), with only case

reports and small case series previously published in the

literature (4,6-20).

Morphologically and immunohistochemically, EMC is a low-grade

malignant tumour with biphasic epithelial and myoepithelial

morphology. The WHO classifies the tumour as ‘a malignant tumour

composed of variable proportions of two cell types, which typically

form duct-like structures. The biphasic morphology is represented

by an inner layer of duct-lining epithelial type cells and an outer

layer of clear myoepithelial cells (1). Many of these lesions are low-grade

malignant epithelial neoplasms but often pose diagnostic problems

because of their central location, circumscription, low-grade

cytological features and occasional focal similarity to other

salivary gland tumours, particularly in small endobronchial biopsy

samples (21). These tumours

usually have a good prognosis after complete surgical resection

with clear margins, but recurrence and metastasis have also been

reported (15,22,23).

To the best of our knowledge, ~50 cases of P-EMC

have been reported worldwide, as detailed in Table SI, but few publications concerning

primary P-EMC exist. Due to its rarity and unproven malignant

potential, the optimal treatment for P-EMC has not been

established. The present study reported a typical case of primary

P-EMC with diagnostic challenges and pitfalls associated with small

biopsy specimens of this rare tumor and reviewed the literature to

comprehensively analyse its clinical features, diagnosis and

appropriate treatment.

Case report

A 58-year-old nonsmoking female presented to Taihe

Hospital (Shiyan, China) after having experienced intermittent

haemoptysis for one month. The patient denied other respiratory

symptoms, including cough, expectoration, fever, night sweats,

fatigue, chest tightness and chest pain. The patient also denied

any history of cancer or relevant family history. Physical

examination indicated clear breath sounds on auscultation, with no

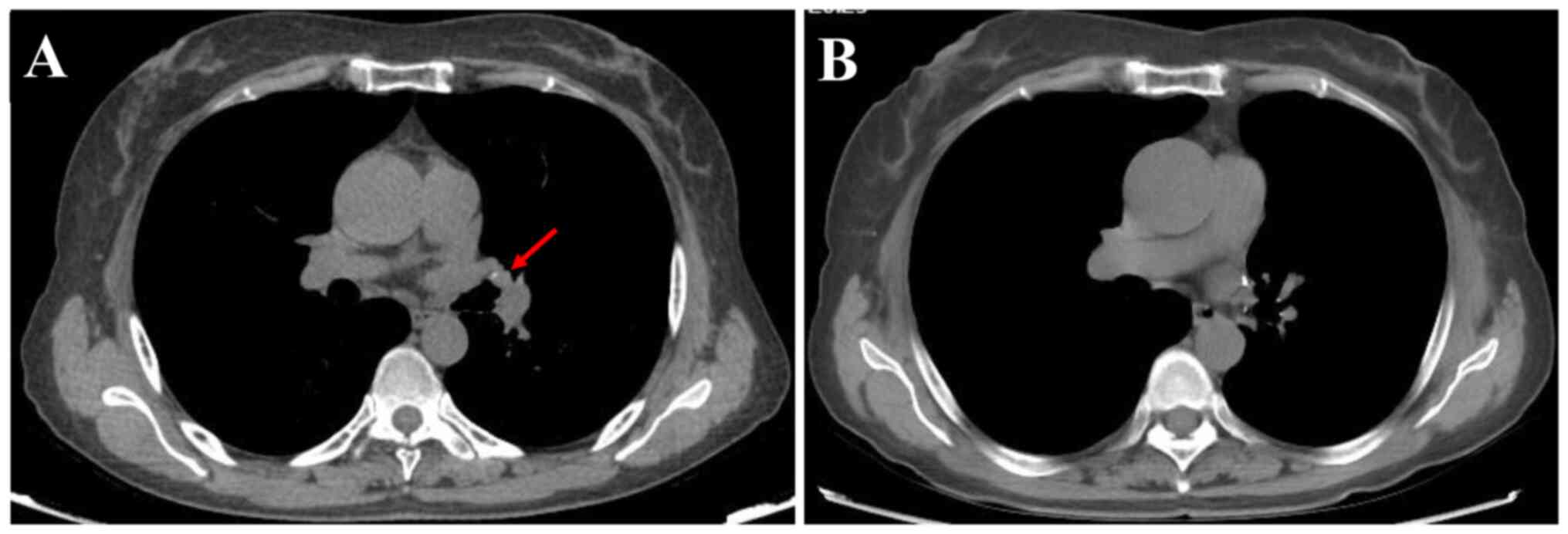

dry or wet rales in both lungs. Chest CT revealed a nodule in the

bronchial lumen of the left superior lobe with a maximum diameter

of 0.8 cm (Fig. 1A). The hilar and

mediastinal lymph nodes were not enlarged. Head and neck magnetic

resonance imaging, bone scintigraphy and whole-body CT scans with

contrast enhancement revealed no distant metastases or

lymphadenopathy. Serum tumour markers for general lung cancer

diagnosis were as follows: Neuron-specific enolase, 10.2 ng/ml

(normal range, 0-16.3 ng/ml); carcinoembryonic antigen, 4.1 µg/l

(normal range, 0-5 µg/l); Cyfra 21-1, 2.9 µg/l (normal range, 0-3.3

µg/l); squamous cell carcinoma antigen, 1.45 ng/ml (normal range,

0-2.7 ng/ml); and ferritin, 164 ng/ml (normal range, 30-400 ng/ml)

- all within normal limits.

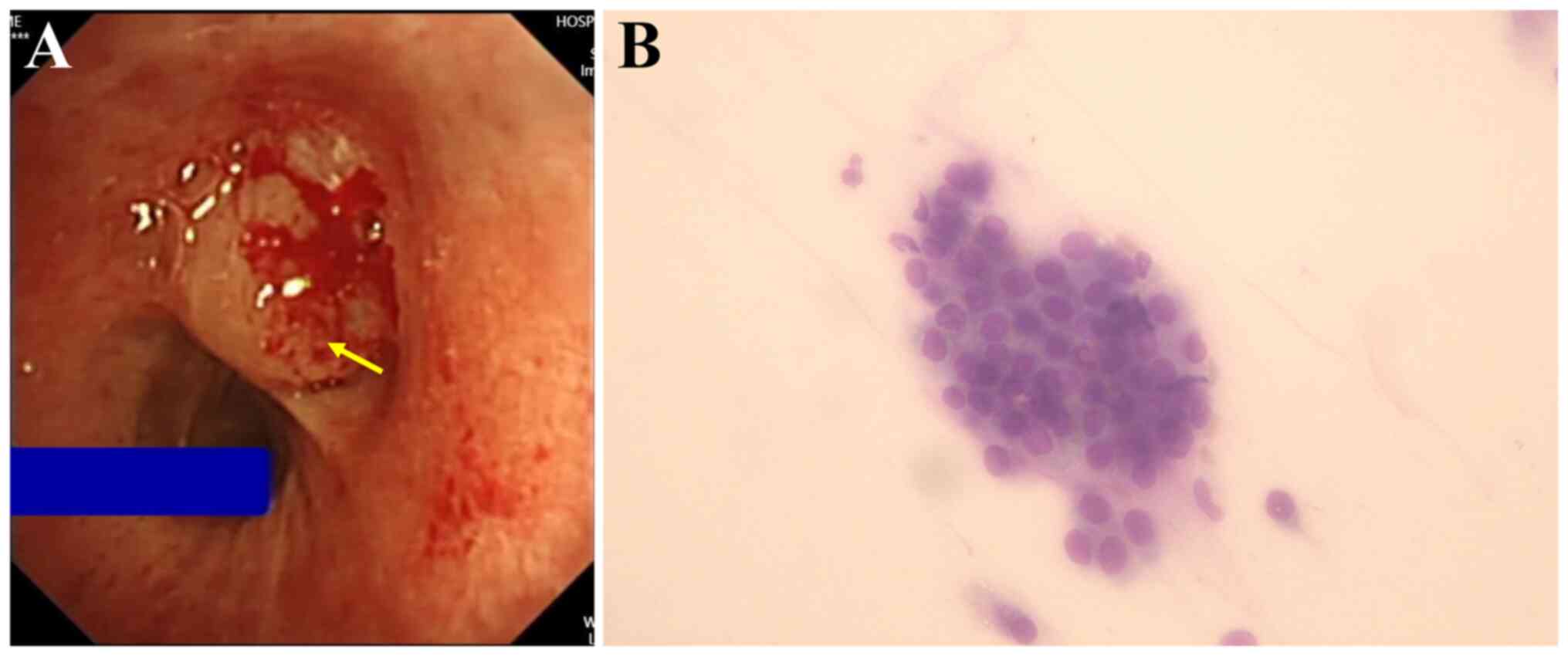

Bronchoscopy revealed a smooth neoplasm obstructing

the lumen at the entrance of the left upper lobe (Fig. 2A). Transbronchial forceps biopsy of

the neoplasm was conducted and rapid onsite evaluation (24) suggested non-small cell lung cancer

(Fig. 2B). Histopathology

indicated a probable diagnosis of mucoepidermoid carcinoma.

Positron emission tomography (PET)-CT scan can determine whether

there is a possibility of tumor metastasis. Given the patient's

financial constraints and the fact that PET-CT scan is not covered

by the local health policy (requiring full out-of-pocket payment),

the patient declined this procedure. Based on the absence of

abnormalities or metastases in the head and neck MRI, bone

scintigraphy and contrast-enhanced whole-body CT, along with

consensus by the multidisciplinary oncologic pulmonology board that

surgical resection was the most appropriate treatment,

video-assisted thoracoscopic (VATS) left upper lobectomy plus

sleeve resection of the left upper lobe bronchus were performed.

Intraoperative frozen section analysis could not definitively

diagnose the tumour, but gross examination of the resected mass

strongly suggested malignancy based on the mass's firm/rubbery

consistency, infiltrative borders (poorly circumscribed) and a

variegated (heterogeneous) cut surface showing mixtures of

grey-white tumour tissue and dense, glistening white sclerotic

areas. Consequently, lymph node dissection was performed at the

carinal, hilar, interlobar and Group 12 lymph nodes based on gross

examination suggested malignancy and the Chinese Society of

Clinical Oncology Non-small Cell Lung Cancer guidelines from

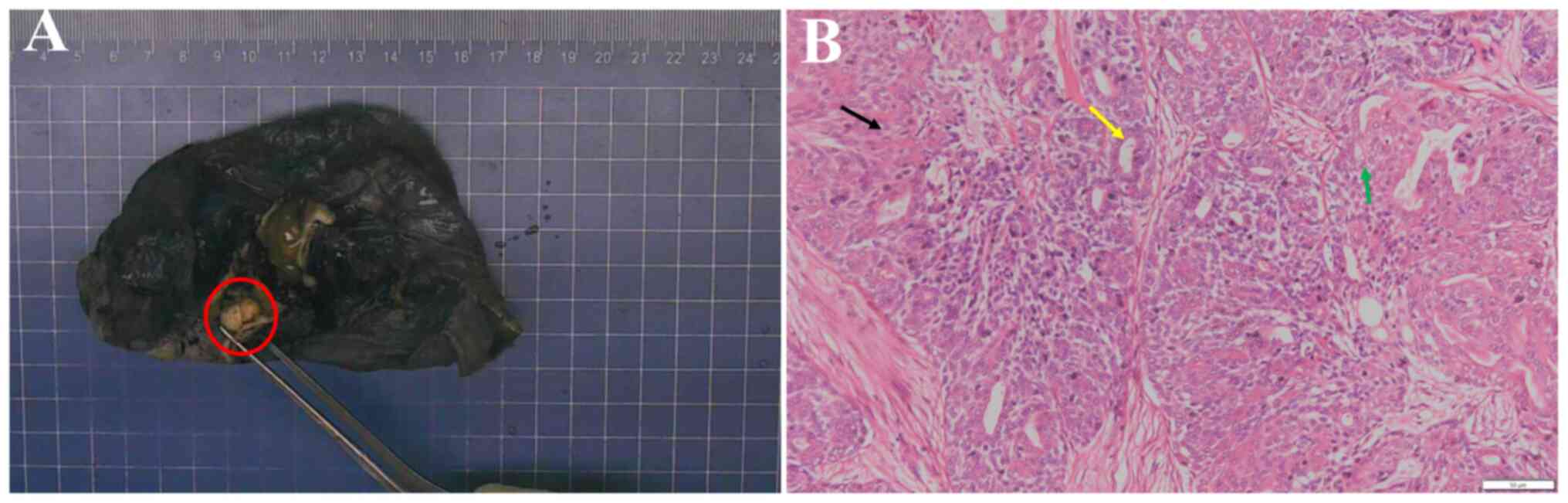

2024(25). Macroscopically, the

size of the resected upper lobe of the left lung was 11.5x8.5x4 cm

and a mass measuring 1.2x1x0.8 cm was observed 0.6 cm from the

bronchial stump (Fig. 3A). The cut

surface was grey-white, solid, firm and nodular, with clear

demarcation from the surrounding tissue, and the remaining lung

tissue was grey-red and soft.

The surgically resected samples were routinely fixed

in 10% neutral-buffered formalin, dehydrated, embedded in paraffin

and sectioned into 4-µm slices. Routine haematoxylin and eosin

staining was performed and the sections were imaged using a CX31

light microscope (Olympus Corp.). Histologically, the tumour

exhibited a biphasic pattern of inner ductal and outer

myoepithelial cells (Fig. 3B). At

low-power magnification, the tumour appeared well-defined but

unencapsulated, displaying a multinodular morphology with irregular

borders. Fibrosis bands were observed dissecting the tumour. The

inner layer consisted of a single row of cuboidal to columnar

epithelial cells and was characterized by dense to finely granular

cytoplasm surrounded by clear myoepithelial cells. The

myoepithelial cells were polygonal or spindle-shaped, with

abundant, clear and glycogen-rich cytoplasm. Myoepithelial cells

forming solid areas were focally observed and areas of squamous

differentiation were also present. These solid patterns blended

with more typical tubular patterns, making distinction between them

challenging. The luminal spaces contained eosinophilic material.

Minimal nuclear pleomorphism and a low mitotic rate were observed.

No metastatic cancer was found in the lymph nodes (0/11) and the

bronchial incisive margin was negative.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) was performed on the

aforementioned surgical sections using the streptavidin-peroxidase

method. The sections were heated at 65˚C for 120 min and then

dewaxed by incubation with xylene for 3 min (six times). The

sections were rehydrated using a graded alcohol series and antigen

retrieval was performed using EDTA repair solution

(EDTA·2Na·2H2O, pH 9.0) with samples heated in a

pressure cooker to the boil and then kept warm for 20 min. The

sections were incubated with 3% H2O2 for 10

min at room temperature and then rinsed with PBS for 3 min to block

endogenous peroxidase activity. Sections were incubated with

primary antibodies against smooth muscle actin (SMA; cat. no.

Kit-0006; Fuzhou Maixin Biotech Co., Ltd.), SOX-10 (cat. no.

RMA-0726; Fuzhou Maixin Biotech Co., Ltd.), S-100 (cat. no.

Kit-0007; Fuzhou Maixin Biotech Co., Ltd.), CKp (cat. no. M3515;

Dako; Agilent Technologies, Inc.), Calponin (cat. no. MAB-0712;

Fuzhou Maixin Biotech Co., Ltd.), P40 (cat. no. RMA-1006; Fuzhou

Maixin Biotech Co., Ltd.), P63 (cat. no. MAB-0694; Fuzhou Maixin

Biotech Co., Ltd.), epithelial membrane antigen (EMA; cat. no.

KIT-0011; Fuzhou Maixin Biotech Co., Ltd.), CD117 (cat. no.

KIT-0029; Fuzhou Maixin Biotech Co., Ltd.), thyroid transcription

factor (TTF)-1 (cat. no. MAB-0599; Fuzhou Maixin Biotech Co.,

Ltd.), CK7 (cat. no. MAB-0828; Fuzhou Maixin Biotech Co., Ltd.) and

Ki-67 (cat. no. MAB-0542; Fuzhou Maixin Biotech Co., Ltd.) for 1 h

at room temperature. The sections were then incubated with the

EnVision detection system peroxidase/diaminobenzidine (DAB) and

rabbit/mouse secondary antibodies (cat. no. K5007; Dako; Agilent

Technologies, Inc.) for 30 min at room temperature. DAB from the

aforementioned secondary staining kit was added for detection. The

sections were counterstained with haematoxylin for 2 min and imaged

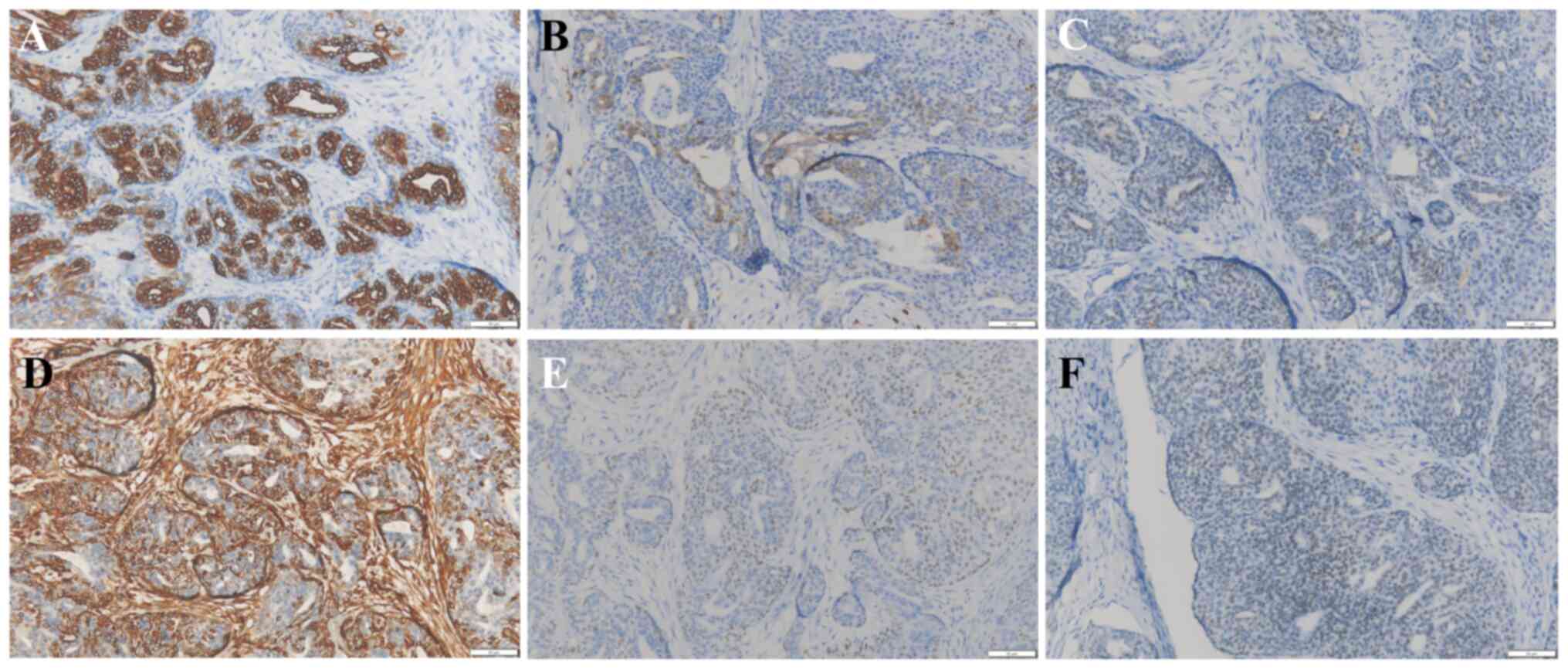

using a CX31 light microscope (Olympus Corp.). Microscopic

observation revealed the following immunohistochemical profile: CKp

(+), calponin (myoepithelium weak +), S-100 (myoepithelium +), SMA

(-), SOX-10 (myoepithelium +), P40 (myoepithelium +), P63

(myoepithelium +), EMA (ductal cell +), CK7 (ductal cell +), CD117

(ductal cell weak +), vimentin (myoepithelium +), TTF-1 (weak +)

and Ki-67 (15% +). Only critical markers for diagnosis were

preserved as images-specifically CK7, S-100, SOX10, VIM, P40 and

TTF-1 (Fig. 4) and images of the

remaining markers are missing.

Based on the above radiological, pathological and

immunostaining findings, the patient was diagnosed with P-EMC. The

patient did not receive any adjuvant chemotherapy and the patient

was discharged 5 days after the surgery with no complications. The

patient was referred to the pulmonary oncology clinic for

postoperative follow-up and underwent contrast-enhanced CT every 3

months within the first year after surgery, and every 6 months from

the second year. The patient was followed up for 5 years, until May

2025. During this period, the oncologist and thoracic surgeon were

responsible for performing the follow-up. A recent

contrast-enhanced chest CT scan (December 2024) revealed no

evidence of recurrence (Fig. 1B)

and the patient remained in good health. A close follow-up of every

1 to 2 years is ongoing.

Literature review

A comprehensive search of the PubMed (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), Google Scholar

(https://scholar.nq69.top/) and Web of

Science databases (https://www.webofscience.com/) for primary P-EMC was

conducted to identify relevant studies published before January

1st, 2025, using the following terms: ‘primary’ AND

(‘tracheobronchial’ OR ‘bronchial’ OR ‘endobronchial’ OR ‘trachea’

OR ‘bronchus’ OR ‘lung’ OR ‘pulmonary’) AND

(‘epithelial-myoepithelial tumour’ OR ‘epithelial-myoepithelial

carcinoma’). Additionally, references from retrieved articles

meeting the inclusion criteria were manually searched. Exclusion

criteria comprised studies not written in English, metastatic

tumours or reports with insufficient data. The extracted data

included patient characteristics (geographic region, age, sex,

symptoms, smoking history, comorbidities, diagnostic modalities,

chest imaging, bronchoscopy, PET-CT, treatment, tumour size,

adjuvant chemotherapy, follow-up and survival). Since 2000, 50

global cases have been reported across 39 publications. After

applying exclusions-three cases for insufficient data, two

non-English reports and one metastatic tumour -44 unique cases met

the criteria for analysis. A total of 44 published cases of P-EMC

were reviewed with relatively complete clinical data reported from

2000 to 2025 (4,6,7,9,11-18,20,26-43),

with the following geographic distribution: The US (n=17), Japan

(n=6), the UK (n=6), China (n=4), South Korea (n=3), Australia

(n=1), Germany (n=1), Greece (n=1), India (n=1), Italy (n=1),

Portugal (n=1), Spain (n=1) and Turkey (n=1). The patients included

20 males and 24 females aged 7-83 years (mean, 55.8 years). A total

of 12 patients had a history of smoking, 22 were non-smokers and 10

had an undocumented smoking status. The tumour size ranged from

0.71 to 6 cm (mean, 2.82 cm), with 27 patients presenting with

endobronchial masses. Among the 10 patients who underwent PET-CT,

only 4 demonstrated normal 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose

(18F-FDG) uptake. Treatment modalities included surgical

resection in 37 patients (lobectomy, n=20; pneumonectomy, n=7;

wedge resection, n=6; segmentectomy, n=1; atypical resection, n=1;

and unspecified resection, n=2); bronchoscopic interventions in 4

patients (electrocautery snare, n=2; curative electrosurgery, n=1;

and laser ablation, n=1); and radiation with chemotherapy in 1

patient with nodal metastasis; while 2 patients received

undocumented treatment. Adjuvant chemotherapy was administered to

only 1 postoperative patient. Among the 44 patients, 32 had

follow-up data ranging from 2.5 to 96 months, while 12 had no

documented follow-up. Outcome analysis revealed no recurrence or

metastasis in 30 patients, death in 2, intrapulmonary metastasis in

1, loss to follow-up in 1 and unknown outcome in 10. Details of the

studies retrieved from the above-mentioned literature review are

provided in Table SI.

Discussion

The present case contributed to the existing

literature by reporting on the diagnostic challenges and pitfalls

associated with small biopsy specimens of this rare tumor and

demonstrating favorable outcomes with no recurrence or metastasis

during 5 years of long-term follow-up. The study underscores the

diagnostic pitfalls in clinical practice and provides evidence that

surgical resection can yield favorable clinical outcomes for this

rare tumor.

The most common salivary gland tumours in the head

and neck are benign, including pleomorphic adenoma, Warthin tumours

and basal cell adenoma, whereas the most common malignant tumours

are mucoepidermoid carcinoma (MEC) and adenoid cystic carcinoma

(ACC). However, salivary gland tumours located in the lungs are

mostly malignant, and the common types include ACC, MEC, EMC and

acinar cell carcinoma (1). EMC is

a rare salivary gland malignancy first described by Donath et

al (44) in 1972, accounting

for ~1% of salivary gland tumours; EMC in the pulmonary system is

even rarer, with only 50 cases reported globally between 2000 and

2025.

The literature review and current case indicate that

primary P-EMC is more prevalent in middle-aged and elderly

individuals, with women showing greater morbidity than men. The

maximum tumour diameter ranged from 0.71 to 6.0 cm (28,30)

and the maximum diameter of the resected mass from the patient of

the present study was 1.2 cm. Among the 44 reported cases of

primary P-EMC, 12 had a history of smoking, 22 had no smoking

history and 10 were undocumented. Therefore, it may be speculated

that the occurrence of primary P-EMC is not associated with

smoking, consistent with the conclusion of Goodwin et al

(45). According to Table SI, radiologically, most P-EMCs are

characterized as endobronchial masses, or bronchoscopy reveals

visible neoplasms or polyps in patients who usually present with

airway obstruction symptoms. However, patients with EMC located in

the lung parenchyma may have no obvious symptoms in the early

stages, and EMC is often detected during chest radiological

examinations. The diagnostic value of 18F-FDG-PET is

unclear; only for 4 cases, elevated glucose metabolism in EMC

lesions was reported (26,32,33,43);

by contrast, the majority of reports indicated normal

18F-FDG uptake (12,17,28,29,31,34).

The diagnosis of EMC depends on histopathology, and a duct-like

structure comprising epithelial and myoepithelial cells is the

typical pathological feature. These duct-like structures can be

categorised into two types: One with a large area with a typical

double-layer tubular structure-epithelial cells forming the inner

layer and myoepithelial cells forming the outer layer of the lumen;

the other type with only few atypical duct-like structures,

consisting of epithelial cells that form a single layer of

duct-like structure surrounded by large confluent myoepithelial

cells. IHC reveals CK positivity in inner epithelial cells, while

the outer myoepithelial cells stain positive for SMA and S-100.

These two pathological patterns may coexist in varying proportions

within the same tumour (6).

Compared with previously reported cases, the

pathological diagnosis presented in the current study poses

significant diagnostic challenges. Initial bronchoscopic biopsy

findings were suggestive of MEC, whereas definitive surgical

specimen pathology confirmed P-EMC. The reasons for the

misdiagnosis or diagnostic discrepancy in the present case are as

follows: Limitations of the small biopsy sample were evident, as

the bronchoscopic biopsy consisted solely of fragmented tissue

measuring 0.5x0.3x0.2 cm, precluding observation of the

characteristic biphasic tubular structure (inner ductal epithelium

plus outer myoepithelial layer) of EMC. The biopsy may have sampled

only an area of epidermoid or intermediate-type cells, mimicking

MEC morphology and leading to misdiagnosis. For instance, abundant

myoepithelial cells could be misinterpreted as myoepithelioma or

myoepithelial carcinoma, while predominant epithelial cells broaden

the differential to include mucinous cystadenocarcinoma, MEC,

mucinous adenoma, acinic cell carcinoma, myoepithelioma,

myoepithelial carcinoma, clear cell (‘sugar’) tumour, metastatic

EMC, and primary or metastatic clear cell carcinomas (6,7,10,30,46).

With respect to tumour heterogeneity, EMC frequently exhibits

regional variation in differentiation: Sampling a dedifferentiated

myoepithelial zone (lacking myoepithelial markers) or a ductal

epithelium-predominant region (expressing CK, P40) in small

biopsies readily leads to MEC misdiagnosis, whereas comprehensive

sampling of resection specimens reveals the typical biphasic

differentiation (6). A critical

diagnostic pitfall involves P40, which is expressed in

myoepithelial cells (particularly basaloid variants), indicating

that a small-biopsy P40(+) result likely represents the

myoepithelial layer of EMC rather than the squamous cells of MEC.

Nevertheless, this P40(+) finding was interpreted as a ‘squamous

differentiation’ marker of MEC. Morphologically, MECs and EMCs

share overlapping features, including solid areas, clear cell

changes and squamoid cells. The absence of definitive EMC biphasic

structures or MEC mucinous cells in limited biopsies creates

diagnostic uncertainty. Finally, while MAML2 rearrangement

demonstrates high specificity for MEC (particularly low- to

intermediate-grade), where positivity supports MEC and negativity

favours EMC, this test was omitted due to the patient's financial

constraints, necessitating reliance on limited immunohistochemistry

for the initial diagnosis.

In general, VATS resection emerged as the most

prevalent therapeutic approach, with lobectomy predominating

(54.1%, n=20), followed by pneumonectomy (18.9%, n=7), wedge

resection (16.2%, n=6) and segmentectomy (2.7%, n=1). Of note,

Hagmeyer et al (11)

reported good outcomes in a young patient who underwent segmental

tracheal resection, with no recurrence or metastasis at the

24-month follow-up. Bronchoscopic interventions were reported in 4

patients (9.1%), including electrocautery snare (n=2), curative

electrosurgery (n=1) and laser ablation therapy (n=1). Among these,

Chao et al (27) reported

successful curative electrosurgery for an endobronchial mass in the

distal left main bronchus of a 43-year-old woman, demonstrating

disease-free survival at the 6-month follow-up. Regrettably, the

remaining three bronchoscopically managed patients were lost to

follow-up or lacked outcome documentation. All patients treated

bronchoscopically and the patient who underwent segmentectomy had

sub-2 cm lesions (≤2 cm), suggesting that bronchoscopic management

is a viable option for small, endobronchially confined tumours,

whereas segmentectomy has favourable outcomes for similarly sized

nonmetastatic lesions. By contrast, lobectomy cases predominantly

involve lesions >2 cm (4,6,7,12,14,18,20,26,30,33,39,40,42).

Among the 6 patients who underwent pneumonectomy, the maximum

diameters of the lesions in 4 patients were 2.7, 4.2, 4.5 and 6 cm,

while the sizes in 2 patients were not recorded. Among the 6

patients who underwent wedge resection, the maximum lesion size was

4 cm and the minimum was 0.8 cm. The patient of the present study

(tumour dimensions: 1.2x1.0x0.8 cm) underwent VATS left upper

lobectomy with bronchial sleeve resection and mediastinal lymph

node dissection due to initial diagnostic pitfalls on bronchoscopic

biopsy. While excellent outcomes with 5-year recurrence-free

survival were achieved, retrospective analysis suggested that

definitive preoperative diagnosis of low-grade malignant P-EMC

might have permitted parenchymal-sparing approaches, such as

segmentectomy or wedge resection, as feasible alternatives.

Of note, the biological characteristics of P-EMC and

salivary EMC are have remained to be fully elucidated. However,

previous reports have shown that the recurrence or metastasis

interval of salivary EMC is relatively long, averaging 5 years

(47) and 15 years (48), respectively. The longest reported

follow-up period to date is 96 months (4). Therefore, the recurrence and

metastasis of P-EMC require further investigation through extended

follow-up. Although typical EMC is generally considered a low-grade

malignancy with a favourable clinical prognosis, numerous studies

have shown that P-EMC with high-grade transformation is aggressive,

with a poor prognosis and a high rate of distant metastasis

(18,30,49).

Tajima et al (18) reported

that Ki-67 and cyclin D1 were key molecules associated with the

high-grade transformation of EMC, suggesting a poor prognosis and

the need for close follow-up. Overall, three studies have reported

the use of NGS to detect mutations associated with primary P-EMC.

Nakashima et al (31)

reported on a 54-year-old female patient with P-EMC in the right

middle lobe. NGS detected no mutations in the Kirsten rat

sarcoma viral oncogene homolog or epidermal growth factor

receptor (EGFR) genes. Sharma et al (17) reported a case of P-EMC in a

38-year-old man presenting with a 3-cm diameter homogeneous mass in

the lower lobe of the right lung. Genetic testing for mutations in

EGFR, anaplastic lymphoma kinase, ROS proto-oncogene

1 tyrosine kinase, B-Raf proto-oncogene, serine/threonine

kinase and mesenchymal-epithelial transition factor was

performed, but no mutations were found. Charles et al

(30) reported on a 72-year-old

female patient with P-EMC with focal high-grade transformation.

Mutations in DNMT3A, APC, STAT3 and

KDM5C were detected. Despite these detected gene mutations,

the patient was still treated with a left pneumonectomy along with

mediastinal lymph node dissection. Based on this literature review,

no specific gene testing is generally recommended for detecting

particular mutations associated with P-EMC, including for guiding

treatment strategies. The clinical significance of DNMT3A,

APC, STAT3 and KDM5C mutations in the

diagnosis, prognosis and treatment of P-EMC requires further

investigation to be established.

In conclusion, primary P-EMC is a low-grade

malignant tumour that most commonly occurs in the tracheobronchial

tree. Histologically, a duct-like structure composed of epithelial

and myoepithelial cells provides evidence for a definite diagnosis.

Based on the present case and a literature review, for

endobronchial EMC lesions confined to the bronchus and measuring

<2 cm without metastasis, bronchoscopic intervention or VATS

segmentectomy are viable therapeutic alternatives; for

nonmetastatic central lesions >2 cm, lobectomy or wedge

resection should be considered to avoid the more traumatic

pneumonectomy as much as possible.

Supplementary Material

Clinical data of previously reported

cases of primary P-EMC.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding authors.

Authors' contributions

DC, JW and FW were involved in the conception/design

of the study. DC and ZZ drafted the manuscript and performed data

acquisition and analysis/interpretation for the study. ZZ and YZ

made contributions to the interpretation of the data for the work

and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual

content. YW, YZ and TR acquired data and collected pathological and

surgical information of the patient. ZZ and JW assisted in updating

patient follow-up information and the literature search. FW, DC and

ZZ confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read

and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

This study was approved by the ethics committee of

Taihe Hospital (approval no., KS2025KS027) and performed in

accordance with the principles of Good Clinical Practice following

the Tri-Council guidelines.

Patient consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the

patient for anonymized information (e.g. medical records/case

information and images) to be published in this article.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Travis WD, Brambilla E, Nicholson AG,

Yatabe Y, Austin JHM, Beasley MB, Chirieac LR, Dacic S, Duhig E,

Flieder DB, et al: The 2015 World health organization

classification of lung tumors: Impact of genetic, clinical and

radiologic advances since the 2004 classification. J Thorac Oncol.

10:1243–1260. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Skálová A, Hyrcza MD and Leivo I: Update

from the 5th Edition of the World Health organization

classification of head and neck tumors: Salivary glands. Head Neck

Pathol. 16:40–53. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Moran CA: Primary salivary gland-type

tumors of the lung. Semin Diagn Pathol. 12:106–122. 1995.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Fulford LG, Kamata Y, Okudera K, Dawson A,

Corrin B, Sheppard MN, Ibrahim NB and Nicholson AG:

Epithelial-myoepithelial carcinomas of the bronchus. Am J Surg

Pathol. 25:1508–1514. 2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Zhu F, Liu Z, Hou Y, He D, Ge X, Bai C,

Jiang L and Li S: Primary salivary gland-type lung cancer:

Clinicopathological analysis of 88 cases from China. J Thorac

Oncol. 8:1578–1584. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Nguyen CV, Suster S and Moran CA:

Pulmonary epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma: A clinicopathologic

and immunohistochemical study of 5 cases. Hum Pathol. 40:366–373.

2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Doganay L, Bilgi S, Ozdil A, Yoruk Y,

Altaner S and Kutlu K: Epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma of the

lung. A case report and review of the literature. Arch Pathol Lab

Med. 127:e177–e180. 2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Naso JR and Roden AC: Recent developments

in the pathology of primary pulmonary salivary gland-type tumours.

Histopathology. 84:102–123. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Shen C, Wang X and Che G: A rare case of

primary peripheral epithelial myoepithelial carcinoma of lung: Case

report and literature review. Medicine (Baltimore).

95(e4371)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Wilson RW and Moran CA:

Epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma of the lung: Immunohistochemical

and ultrastructural observations and review of the literature. Hum

Pathol. 28:631–635. 1997.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Hagmeyer L, Tharun L, Schäfer SC, Hekmat

K, Büttner R and Randerath W: First case report of a curative wedge

resection in epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma of the lung. Gen

Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 65:535–538. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Jindani R, Lopez MA, Miquel TP and Sylvin

E: Robotic resection of pulmonary epithelial myoepithelial

carcinoma: A case report. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg Rep. 10:e42–e44.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Konoglou M, Cheva A, Zarogoulidis P,

Porpodis K, Pataka A, Mpaliaka A, Papaiwannou A, Zarogoulidis K,

Kontakiotis T, Karaiskos T, et al: Epithelial-myoepithelial

carcinoma of the trachea-a rare entity case report. J Thorac Dis. 6

(Suppl 1):S194–S199. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Mori M, Hanagiri T, Nakanishi R, Ashikari

S, Yasuda M and Tanaka F: Primary epithelial-myoepithelial

carcinoma of the lung with cavitary lesion: A case report. Mol Clin

Oncol. 9:315–317. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Nishihara M, Takeda N, Tatsumi S,

Kidoguchi K, Hayashi S, Sasayama T, Kohmura E and Hashimoto K:

Skull metastasis as initial manifestation of pulmonary

epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma: A case report of an unusual

case. Case Rep Oncol Med. 2011(610383)2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Patterson DT, Halverson Q, Williams S,

Bishop JA, Ochoa CD and Styrvoky K: Bronchoscopic management of a

primary endobronchial salivary epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma:

A case report. Respir Med Case Rep. 30(101083)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Sharma S, Tayal A, Khatri S, Mohapatra SG

and Mohanty SK: Primary pulmonary epithelial-myoepithelial

carcinoma: Report of a rare and under-diagnosed low-grade

malignancy. J Cancer Res Ther. 18:795–800. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Tajima S, Aki M, Yajima K, Takahashi T,

Neyatani H and Koda K: Primary epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma

of the lung: A case report demonstrating high-grade

transformation-like changes. Oncol Lett. 10:175–181.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Wang H, Zhang Y, Wang B, Wei J, Ji R, Dong

L and Jiang X: Epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma of the parotid

gland with primary lung cancer: A rare case report. Medicine

(Baltimore). 99(e22483)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Zhang G, Wang R, Qiao X and Li J: Primary

epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma of the lung presenting as

multiple synchronous lesions. Ann Thorac Surg. 115:e17–e19.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

J.W.E. L. Barnes, P. Reichart, and D.

Sidransky, Eds., ‘Epithelial myoepithelial carcinoma,’ in World

Health Organization Classification of Tumors, Pathology and

Genetics of Head and Neck Tumors, 2005.

|

|

22

|

Song DH, Choi IH, Ha SY, Han KM, Han J,

Kim TS, Kim J and Kim H: Epithelial-myoepthelial carcinoma of the

tracheobronchial tree: The prognostic role of myoepithelial cells.

Lung Cancer. 83:416–419. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Muslimani AA, Kundranda M, Jain S and Daw

HA: Recurrent bronchial epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma after

local therapy. Clin Lung Cancer. 8:386–388. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Wang H, Wei N, Tang Y, Wang Y, Luo G, Ren

T, Xiong T, Li H, Wang M and Qian X: The utility of rapid on-site

evaluation during bronchoscopic biopsy: A 2-year respiratory

endoscopy central experience. Biomed Res Int.

2019(5049248)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Chen S, Wang Z and Sun B: Chinese Society

of Clinical Oncology Non-small Cell Lung Cancer (CSCO NSCLC)

guidelines in 2024: Key update on the management of early and

locally advanced NSCLC. Cancer Biol Med. 22:191–196.

2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Cha YJ, Han J, Lee MJ, Lee KS, Kim H and

Zo J: A rare case of bronchial epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma

with solid lobular growth in a 53-year-old woman. Tuberc Respir Dis

(Seoul). 78:428–431. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Chao TY, Lin AS, Lie CH, Chung YH, Lin JW

and Lin MC: Bronchial epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma. Ann

Thorac Surg. 83:689–691. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Kim CH, Jeong JS, Kim SR and Lee YC:

Endobronchial epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma of the lung.

Thorax. 73:593–594. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

McCracken D, Wieboldt J, Sidhu P and

McManus K: Endobronchial laser ablation in the management of

epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma of the trachea. Respir Med Case

Rep. 16:151–153. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Charles R, Murray S, Gray E and Hu J:

Pulmonary epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma (P-EMC) with focal

high grade transformation: Molecular and cytologic findings. Diagn

Cytopathol. 50:E156–E162. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Nakashima Y, Morita R, Ui A, Iihara K and

Yazawa T: Epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma of the lung: A case

report. Surg Case Rep. 4(74)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Arif F, Wu S, Andaz S and Fox S: Primary

epithelial myoepithelial carcinoma of lung, reporting of a rare

entity, its molecular histogenesis and review of the literature.

Case Rep Pathol. 2012(319434)2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Cho SH, Park SD, Ko TY, Lee HY and Kim JI:

Primary epithelial myoepithelial lung carcinoma. Korean J Thorac

Cardiovasc Surg. 47:59–62. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Westacott LS, Tsikleas G, Duhig E, Searle

J, Kanowski P, Diqer M and Binder J: Primary

epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma of lung: A case report of a rare

salivary gland type tumour. Pathology. 45:420–422. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Huang HC, Zhao L, Cao LX, Meng G, Wang YJ

and Wu M: Primary salivary gland tumors of the lung: Two cases date

report and literature review. Respir Med Case Rep.

32(101333)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Doxtader EE, Shah AA, Zhang Y, Wang H,

Dyhdalo KS and Farver C: Primary salivary gland-type tumors of the

tracheobronchial tree diagnosed by transbronchial fine needle

aspiration: Clinical and cytomorphologic features with

histopathologic correlation. Diagn Cytopathol. 47:1168–1176.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Shiina Y, Yoshimura M and Tauchi S:

Pulmonary epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma;report of a case.

Kyobu Geka. 73:708–711. 2020.PubMed/NCBI(In Japanese).

|

|

38

|

Muro M, Yoshioka T, Idani H, Sasaki H,

Asami S, Nojima H, Kubo S, Kurose Y, Hirata M, Yamashita T, et al:

Epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma of the lung. Kyobu Geka.

63:220–223. 2010.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Rosenfeld A, Schwartz D, Garzon S and

Chaleff S: Epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma of the lung: A case

report and review of the literature. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol.

31:206–208. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Muñoz G, Felipo F, Marquina I and Del Agua

C: Epithelial-myoepithelial tumour of the lung: a case report

referring to its molecular histogenesis. Diagn Pathol.

6(71)2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Pelosi G, Fraggetta F, Maffini F, Solli P,

Cavallon A and Viale G: Pulmonary epithelial-myoepithelial tumor of

unproven malignant potential: Report of a case and review of the

literature. Mod Pathol. 14:521–526. 2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Chang T, Husain AN, Colby T, Taxy JB,

Welch WR, Cheung OY, Early A, Travis W and Krausz T: Pneumocytic

adenomyoepithelioma: A distinctive lung tumor with epithelial,

myoepithelial, and pneumocytic differentiation. Am J Surg Pathol.

31:562–568. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Morgado S, Santos AF and Nogueira F:

Primary pulmonary epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma: A case report

and comprehensive literature review of a rare lung neoplasm.

Cureus. 17(e80188)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Donath K, Seifert G and Schmitz R:

Diagnosis and ultrastructure of the tubular carcinoma of salivary

gland ducts. Epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma of the intercalated

ducts. Virchows Arch A Pathol Pathol Anat. 356:16–31.

1972.PubMed/NCBI(In German).

|

|

45

|

Goodwin CR, Khattab MH, Sankey EW, Crane

GM, McCarthy EF and Sciubba DM: Epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma

metastasis to the thoracic spine. J Clin Neurosci. 24:143–146.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Miura K, Harada H, Aiba S and Tsutsui Y:

Myoepithelial carcinoma of the lung arising from bronchial

submucosa. Am J Surg Pathol. 24:1300–1304. 2000.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Luna MA, Ordonez NG, Mackay B, Batsakis JG

and Guillamondegui O: Salivary epithelial-myoepithelial carcinomas

of intercalated ducts: A clinical, electron microscopic, and

immunocytochemical study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol.

59:482–490. 1985.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Cho KJ, el-Naggar AK, Ordonez NG, Luna MA,

Austin J and Batsakis JG: Epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma of

salivary glands. A clinicopathologic, DNA flow cytometric, and

immunohistochemical study of Ki-67 and HER-2/neu oncogene. Am J

Clin Pathol. 103:432–437. 1995.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Costa AF, Altemani A and Hermsen M:

Current concepts on dedifferentiation/high-grade transformation in

salivary gland tumors. Patholog Res Int.

2011(325965)2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|