1. Introduction

Over the past decade, a number of studies have shown

that women with endometriosis are at increased risk for developing

various diseases as comorbidities, including asthma (1), various types of cancer, such as

ovarian and breast cancer, as well as cutaneous melanoma (2), cardiovascular and psychiatric

diseases (3,4), hypothyroidism and fibromyalgia

(1). In addition, other studies

have reported an association between different autoimmune diseases,

including autoimmune thyroid disorder, Crohn's disease and

ulcerative colitis, Sjogren's syndrome (SS), systemic lupus

erythematosus (SLE), multiple sclerosis, ankylosing spondylitis

(AS), coeliac disease and rheumatoid arthritis (RA), and an

increased risk for endometriosis (5-9).

Endometriosis is a common yet enigmatic

inflammatory, multifactorial, estrogen-dependent gynecological

condition with an unknown etiology, affecting up to 10% of women of

reproductive age worldwide and 9 million women in the USA (10). Endometriosis is characterized by

the presence of ectopic endometrial tissue (endometrial glands and

stroma) on other organs, predominantly external to the uterine

cavity and most commonly in the pelvic cavity, due to the ectopic

localization of endometrial cells. Endometriosis can appear as

peritoneal lesions, ovarian endometriotic cysts and deeply

infiltrative endometrial lesions (11). Furthermore, endometriosis is

associated with chronic pelvic pain, dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia,

heavy or irregular menstrual bleeding, urinary tract symptoms,

subfertility and infertility in 30% of patients (11,12).

Endometriosis-associated gene polymorphisms, epigenetic

modifications (such as methylation, acetylation, phosphorylation

and modifications to the histone proteins associated with DNA

packaging in chromatin), proinflammatory factors (including

cytokines like IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8 and TNF-α, as well as

prostaglandins), hormonal factors (including an imbalance between

estrogen and progesterone) and environmental factors (including

organic pollutants, polyhalogenated aromatic hydrocarbons, tobacco,

heavy metals and pesticides) contribute to the development of the

disease and trigger its specific clinical symptoms (11,12).

Nowadays, a large amount of evidence indicates that dysregulation

of the immune system leads to chronic inflammatory response in the

ectopic endometrium, thus resulting in the subsequent development

of endometriosis (13,14).

According to previous studies, women with

endometriosis are at a higher risk for developing a concomitant

autoimmune disease, considering the deregulation of the immune

system observed in these patients (2,4,5,10,12).

In this context, both proinflammatory and mitogenic proteins from

endometriotic lesions, including cytokines (RANTES, IL-1, IL-6,

TNF-a) and VEGF, as well as associated activated immune cells, such

as pelvic macrophages and lymphocytes, can cause an imbalance in

the immune system, which contributes to the enhanced inflammatory

reaction that is associated with the development of endometriosis

(15). Accordingly, functional

abnormalities in almost all types of immune cells have been

identified in endometriosis, including neutrophils, macrophages,

natural killer (NK) cells, B and T lymphocytes, as well as

dendritic cells (DCs) (13).

Moreover, a series of anti-nuclear, anti-phospholipid and

anti-endometrial antibodies are produced in endometriosis (14). This link of endometriosis with

aberrant immune responses and the subsequent development of

autoimmune diseases has led to the suggestion that endometriosis

itself may be classified as a typical autoimmune disorder (14,16).

Alternatively, another concept suggests that an underlying abnormal

immune response may contribute to the development of endometriosis

(5).

Recently, Chen et al (17) attempted to clarify whether patients

with endometriosis have a higher risk of developing

antiphospholipid syndrome (APS), by conducting a retrospective

cohort study. It was demonstrated, for the first time to the best

of our knowledge, that patients with endometriosis have a higher

risk (2.84-fold) of developing subsequent APS compared with women

without endometriosis (17).

However, the existing information refers only to epidemiological

and clinical aspects of this detected association. APS is a

systemic autoimmune disease characterized by the occurrence of

vascular or arterial thromboses at different localizations,

including the brain, heart, lungs, kidneys and limbs, obstetric

complications in women of childbearing age including miscarriages,

recurrent fetal deaths and premature birth, and the presence of

circulating antiphospholipid (aPL) antibodies (18). As an autoimmune disease, APS is

developed by an interplay of genetic and antigenic factors, while

specific autoantibodies are present and used for its diagnosis,

such as lupus anticoagulant, anti-cardiolipin (aCL) antibodies,

anti-β2 glycoprotein-I (β2GPI) antibodies and

anti-phosphatidylserine/prothrombin antibodies (19,20).

The genetic predisposition of APS has been demonstrated by studies

in monozygotic twins, gene-association and genome-wide association

studies (GWAS) as well as whole-exome sequencing (WES) approaches

(21-25).

Importantly, APS can occur as a single disorder where there is no

clinical or laboratory evidence of another underlying disease,

called ‘primary APS’ (PAPS), but it can also be associated with

another autoimmune disease, and referred to in this case as

‘secondary APS’ (26).

Consequently, APS may, in part, share a common mechanism for

disease development or progression with other autoimmune or

immunity-related diseases.

The recent data regarding the increased risk of

subsequent APS in women with endometriosis posed an interesting

question concerning the putative role of shared genetic factors in

the co-occurrence of both conditions (17). Notably, our previous studies have

focused on the delineation of the genetic components that are

involved in the co-occurrence of endometriosis with various

autoimmune diseases, including SLE (27), RA (7), AS (8), SS (9), as well as psoriasis and psoriatic

arthritis (28). In the present

review, prompted by the findings of Chen et al (17), the present review sought to

delineate the genetic basis of the co-occurrence of endometriosis

with APS by systematically searching the literature for genes

involved in the development of both diseases, aiming to shed light

on the functional significance of the shared polymorphisms and

unravel the underlying molecular and pathogenetic mechanisms of

these diseases.

2. Shared genetic loci associated with

endometriosis and APS

In the current review, a potential shared genetic

background regarding the co-occurrence of endometriosis and APS was

investigated. To the best of our knowledge, the present review is

the first study in the literature focusing on the genetic basis of

the subsequent development of APS in patients with endometriosis.

The present review included case-control, GWAS, whole-genome

sequencing and WES studies, as well as systematic reviews and

cross-sectional studies. Notably, case report series, editorial

letters, expert opinions and conference abstracts were excluded.

The articles included were written in the English language and

published from 2000-2025. Five electronic databases were used,

namely PubMed (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), PubMed Central

(https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), Google

Scholar (https://scholar.google.com/), Web of

Science (https://www,webofscience.com/wos/) and MEDLINE

(https://www.nlm.nih.gov/medline/medline_home.html/).

The keywords used for the search were as follows: ‘Endometriosis’,

‘antiphospholipid syndrome’, ‘antiphospholipid antibodies’,

‘genetics’, ‘gene polymorphisms’, ‘association studies’ and ‘GWAS’.

Two authors worked individually to extract the data following the

specified criteria and no disagreements arose during this

process.

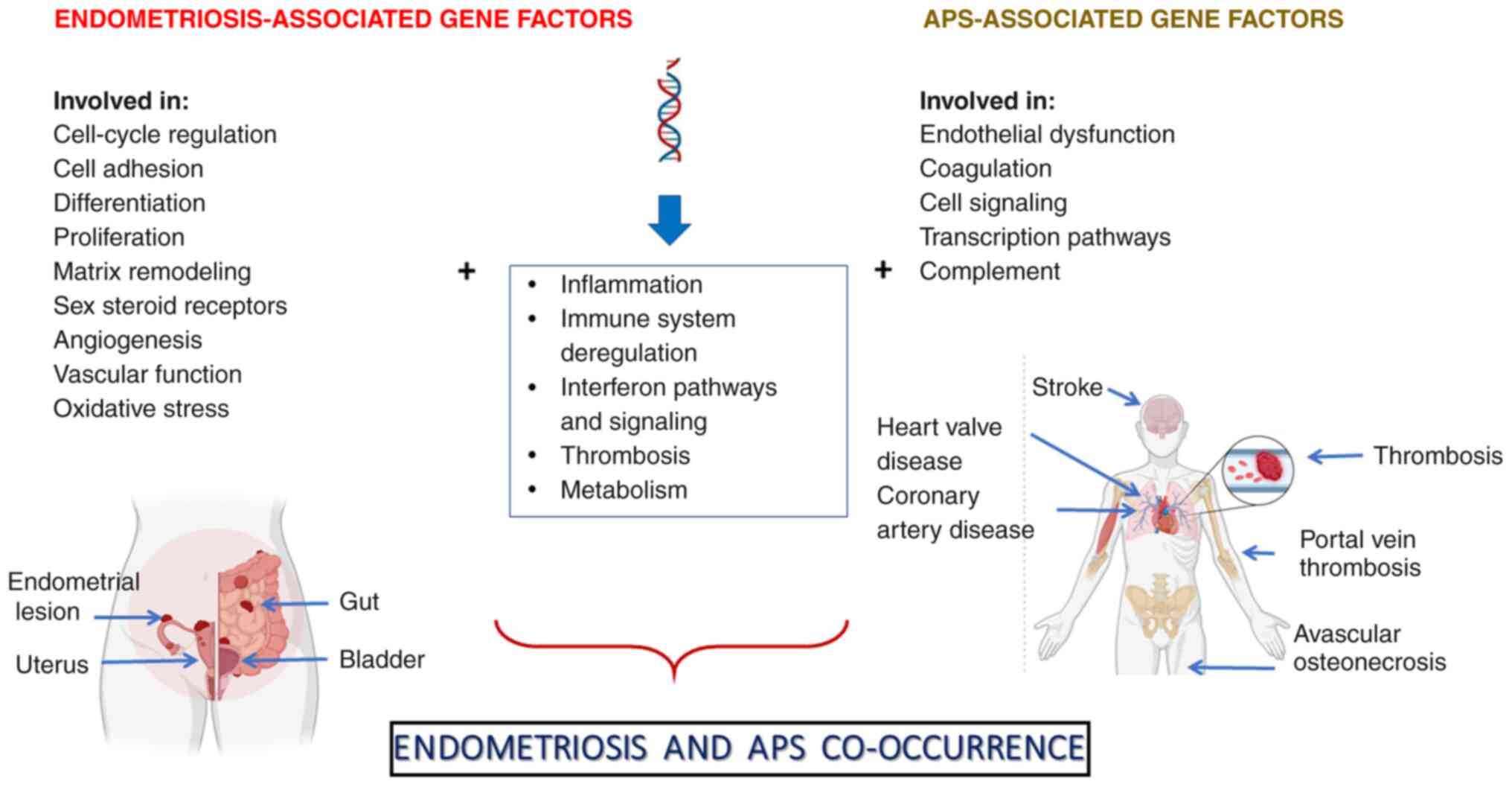

Accordingly, certain genes were identified as

potential risk factors for developing endometriosis and APS, which

are involved in inflammatory and/or interferon (IFN)-inducible

processes, immune system dysregulation and thrombosis (Fig. 1). The identified gene-related risk

factors included the human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-DQB1*0301

(29,30) and HLA-DQA1*0301 alleles

(29,31), the 4G/5G polymorphism of the serpin

family E member 1 (SERPINE1) gene [encoding plasminogen

activator inhibitor type 1 (PAI-1) protein] (32,33),

methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) rs1801133

(34,35), signal transducer and activator of

transcription 4 (STAT4) rs7574865 (36,37)

and toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) rs4986790 (38,39)

single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). The shared gene

polymorphisms and the function of the respective genes are

demonstrated in Table I.

| Table IOverview of genetic polymorphisms

associated with both endometriosis and APS, as confirmed by

gene-association and/or genome-wide association studies. |

Table I

Overview of genetic polymorphisms

associated with both endometriosis and APS, as confirmed by

gene-association and/or genome-wide association studies.

| Endometriosis- and

APS- associated gene | Single nucleotide

polymorphism database ID | Function | (Refs.) |

|---|

|

HLA-DQB1*0301 | N/A | Presents peptides

derived from extracellular proteins | (29,30) |

|

HLA-DQA1*0301 | N/A | Presents peptides

derived from extracellular proteins | (29,31) |

|

SERPINE1 | N/A | A serine protease

inhibitor, involved in fibrinolysis | (32,33) |

| MTHFR | rs1801133 | A key regulatory

enzyme in folate and homocysteine metabolism | (34,35) |

| STAT4 | rs7574865 | A transcription

factor involved in T helper 17 differentiation and monocyte

activation | (36,37) |

| TLR4 | rs4986790 | A transmembrane

protein, member of the TLR family | (38,39) |

3. Biological mechanisms relative to the

co-occurrence of endometriosis and APS

Polymorphisms in genes involved in

immune responses (major histocompatibility complex-associated

genes)

The HLA genes encode proteins that bind

antigen peptides and present them to T cells, and also play key

roles in the immune response by interacting with the complement

system and restricting the recognition of antigenic peptides by T

cells and their involvement in cellular immunity (40). The HLA-DQB1*0301

allele of the HLA class II gene DQB1 has been associated

with increased susceptibility for both endometriosis and APS

(29,30). The association between

endometriosis and the genes encoding the protein components of the

HLA system has not yet been fully elucidated. However, considering

that the suppression of cellular immunity in the peritoneal space

causes endometriosis, it has been hypothesized that particular

HLA gene alleles may signal these cells to decrease their

cytotoxic properties (30). A

notably higher frequency of the HLA-DQB1*0301 allele

has been observed in patients with endometriosis, but the

underlying mechanism of this association has not been fully

clarified yet (30,41). The DQB1*0301 allele has also

been associated with the development of APS, as well as with the

presence of aCL antibodies in PAPS (29). In fact, it has been suggested that

DQB1*0301 among other HLA alleles, such as

HLA-DRB1*04, DRB1*07, DRB1*1302, DRw53,

DQA1*0102 and DQA1*0201, determines the

susceptibility to the production of aPL antibodies, which are

responsible for the clinical manifestations of APS (29). Notably, HLA-DQA1*0301 allele

was also found to be associated with both endometriosis and APS

(29,31); this allele is associated with an

increased production of β2GPI antibodies in patients with APS, thus

leading to thrombotic events and pregnancy morbidity (42).

Polymorphism in a gene involved in

thrombosis

The SERPINE1 gene (coding for PAI-1) encodes

a monomeric glycoprotein that is a fast-acting inhibitor of

plasminogen activation, belonging to the serine protease inhibitor

superfamily and regulating the fibrinolytic pathway (32). Genetic alterations of

SERPINE1 have been considered as risk factors for the

development of various diseases, including thrombosis (43). A common insertion/deletion SNP in

the SERPINE1 gene, located 675 bp upstream from the start

codon, induces the generation of two alleles containing either 4 or

5 sequential guanosines, with individuals carrying homozygosity in

the deletion allele (4G/4G) having increased gene transcriptional

activity and markedly elevated plasma PAI-1 protein activity

compared with those in 5G/5G individuals (44,45).

The 4G/5G polymorphism in the promoter region of SERPINE1

has been associated with the development of endometriosis and APS

(32,33). Particularly, the 4G/4G and the

4G/5G genotypes, as well as the 4G allele of this polymorphism of

the SERPINE1 gene, were found to be associated with an

increased susceptibility for endometriosis. Furthermore, the 4G

allele was also associated with hypofibrinolysis, which was

observed at a notably higher frequency in women with endometriosis

compared with that in women without endometriosis (32). Notably, it has been suggested that

persistence of a fibrin matrix as a result of hypofibrinolysis

could mediate the initiation of endometriotic lesions in the

peritoneal cavity (32). Moreover,

the presence of the 4G allele has been associated with higher

plasma levels of PAI-1 and increased risk for thrombosis in

patients with PAPS, compared with those in healthy controls

(33).

Polymorphism in a metabolism-related

gene

The MTHFR gene encodes the 77-kDa MTHFR

protein, which catalyzes the irreversible reduction of 5-10-MTHF to

5-methylTHF, thus representing an essential enzyme in folate and

homocysteine metabolism (46) and

playing an important role in DNA methylation and synthesis

(46). The missense MTHFR

rs1801133 (Ala222Val, C677T) SNP, located in exon 4, has been shown

to be associated with both endometriosis and APS (29,30).

The risk allele ‘T’ influences the enzymatic activity by producing

a thermally unstable protein, which prevents optimal functioning of

the enzyme at temperatures >37˚C (46) and leads to elevated plasma levels

of homocysteine. In endometriosis, elevated homocysteine, along

with oxidative stress, may contribute to impaired blood flow and

reduced fertility (47). Notably,

the increased homocysteine levels in combination with vascular

inflammation and injury may lead to the development of

cardiovascular disease, which is a known comorbidity of

endometriosis (3,48). It is worth noting that the

accumulation of high levels of cytotoxic homocysteine in the

circulating blood may lead to damage of the inner wall of blood

vessels. Consequently, the coagulation cascade reactions can be

activated and the risk for thrombosis and ultimately APS is

increased (34).

Polymorphisms in genes associated with

IFN pathways and signaling

The STAT4 gene is located on chromosome

2q32.2-2q32-3(49), and encodes a

transcription factor that is expressed in activated peripheral

blood monocytes, macrophages, myeloid cells, DCs and T cells, and

plays pivotal roles in the differentiation and proliferation of

both T helper (Th) 1 and Th17 cells (49,50).

Combined evidence based on gene association studies, GWAS and

meta-analyses has shown an unambiguous association between

STAT4 rs7574865 SNP and various autoimmune diseases, as well

as chronic inflammatory diseases (51). It has been suggested that this

variant of STAT4 may be involved in the regulation of the

balance between the IL-12 and IL-23 effect, thus leading to

inflammatory diseases through the dysregulation of the Th1 vs. Th17

differentiation (51). In

addition, in silico studies have highlighted the regulatory

function of this SNP in gene expression of STAT4,

considering its location near both distal enhancers and an

important genome regulatory factor, CCCTC-binding factor, which

represents a highly conserved zinc finger protein with key roles in

genome organization and gene expression, influencing both gene

activation and repression (52).

In endometriosis, an increased frequency of the TT

genotype of the rs7574865 (G/T) SNP has been observed in women

suffering from minimal or mild endometriosis compared with that in

women without endometriosis (36).

Furthermore, it has been suggested that this SNP may impair either

the gene expression or mRNA splicing of the STAT4 gene,

thereby playing an important role in IFN signaling (36). Furthermore, the role of the

rs7574865 SNP may be strengthened, considering both the strong

association of the T allele with Th1 responses and the association

between Th1 responses and deep infiltration in pelvic endometriosis

(53). Notably, a positive

association between the T allele of STAT4 rs7574865 and APS

has been reported; moreover, this association was still observed

after the stratification of patients with APS by the clinical

manifestations of this disorder, including thrombosis or obstetric

complications (37).

TLRs are pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), which

form a family of transmembrane protein molecules that play a

crucial role in the regulation of immune and inflammatory responses

(54). TLRs activate cellular

signaling pathways to induce immune-response genes, including genes

encoding cytokines, chemokines and other immune mediators, and

represent a host defense mechanism against infections and tissue

damage, leading to the secretion of various inflammatory cytokines

(55). TLR4, a type I

transmembrane glycoprotein, is a PRR that mainly recognizes the

lipopolysaccharide (LPS) of Gram-negative bacteria as well as

structures from fungal and mycobacterial pathogens, and activates

innate immunity through the production of cytokines, such as IL-1,

IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α and MIP (56,57).

TLR4 is composed of three domains, an extracellular, a

transmembrane and a cytoplasmic domain, and was found to be

involved in the pathogenesis of infectious (i.e. gram-negative

infections, periodontitis and septic shock), inflammatory (obesity,

liver and kidney disease, cardiovascular and neurodegenerative

diseases) and autoimmune diseases (SLE, RA, MS, SSc, PS, SS and

APS) (45,58).

The TLR4 rs4986790 SNP results in an aspartic

acid to glycine substitution at position 299 (D299G), which alters

the formation of the TLR4/myeloid differentiation factor 2 complex

(59). This SNP has been

associated with the development of both endometriosis and APS

(25,38). In particular, the involvement of

TLR4 in endometriosis has been linked to its regulatory role in the

activation of immune and inflammatory responses (60). TLR4 is expressed in endometrial and

endometriotic epithelial cells in women with endometriosis, and

alterations in its expression levels or function have been detected

in the endometrium and pelvic environment (38,60).

The risk allele ‘G’ of the rs4986790 SNP was found to affect the

function of TLR4. Particularly, the ‘G’ allele of the TLR4

(A896G) rs4986790 SNP was found to result in hypo-responsiveness of

the receptor, thus resulting in peritoneal inflammation as

suggested by Latha et al (38). Under this condition, the molecular

microenvironment may become favorable for the endometrial cells to

adhere to the pelvic peritoneum, thus leading to the initiation of

endometriosis (38). Previous

findings based on molecular dynamics simulations showed that the

rs4986790 SNP may abrogate the stability of the hexamer complex

that is crucial for LPS recognition and antibacterial immune

response, being necessary to dimerize the cytoplasmic domain of the

TLR4 protein and ultimately result in compromised TLR4 signaling

(61). Notably, an eight-fold

increase of endometriosis risk was seen in women who are carriers

of the GG genotype (38).

Regarding APS, elevated levels of TLR4 in the cell surface of

peripheral blood mononuclear cells, as well as in monocytes, were

observed among patients with PAPS compared with those in healthy

controls (62). As suggested

previously, the activation of the TLR pathway and TLR4 reactivity

can lead to vascular thrombosis in patients with PAPS (45). Pierangeli et al (39) suggested that, in patients with APS,

the risk allele ‘G’ of the rs4986790 SNP confers a higher

susceptibility to prothrombotic endothelial activation mediated by

aPL antibodies.

4. Conclusions and future perspectives

To the best of our knowledge, the present review is

the first study attempting to delineate the genetic basis of the

co-occurrence of endometriosis and APS. Although only a few shared

gene polymorphisms for these disorders were identified, the present

review highlighted a number of loci involved in inflammatory and/or

IFN-inducible processes, immune system deregulation and thrombosis.

Genetic factors are important in the development of both

endometriosis and APS, as has been demonstrated previously by the

familiar occurrence of these health conditions and their

association with various gene polymorphisms. The identification of

further genetic factors associated with these diseases is of

emerging interest and may help to better delineate the mechanisms

leading to their clinical association. These results are important

not only for future genetic and clinical studies, but also for

directing future function/structure studies on the molecular cause

of endometriosis and APS. Moreover, the increasing number of

disease-associated variants may contribute to the development and

validation of gene risk scores for both diseases, thus improving

the risk assessment and tailored management of these disorders.

Further exploration of immune cell signatures and/or

cytokine profiles has emphasized the pivotal role of immune

dysregulation in the immune-mediated mechanisms leading to

endometriosis and APS. The specific immune cell signature of APS is

characterized by activated neutrophils and an enhanced type I IFN

response, while the involvement of other types of immune cells,

including DCs, T and B cells, monocytes and NK cells has been also

reported in the pathogenesis of APS (63,64).

In endometriosis, distinct immune cells signatures have been found

in the peritoneal cavity, including increased numbers of

CD8+ T cells and activated NK cells, along with

follicular Th cells. By contrast, M2 macrophages and resting mast

cells were observed at low levels in eutopic endometria. Moreover,

activated CD4+ T and B cells form part of the immune

signatures associated with endometriosis (65,66),

while neutrophils, macrophages, NK cells and DCs also serve a role

in endometriosis (13). Cytokine

profiles in APS often show an imbalance, with increased levels of

pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α and IL-6, and potentially

decreased levels of anti-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-10.

Furthermore, notably elevated levels of IL-7, IL-8, IL-10, IL-16,

IL-17 and IL-12/IL-23p40 and decreased levels of IL-22 and IL-31

have been detected in patients with APS compared with those in

healthy controls (67,68). In women with endometriosis,

elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines are frequently

observed in both peritoneal fluid and serum. Pro-inflammatory

cytokines, such as IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8 and TNF-α, have been found to

be increased in the peritoneal fluid of women with endometriosis,

while some anti-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-10 and IL-33,

may also appear at elevated levels in endometriosis. IL-25 (also

known as IL-17E), IL-33 and thymic stromal lymphopoietin, which are

involved in Th2 cell development, are increased in the peripheral

blood, endometrium and peritoneal fluid of patients with

endometriosis compared with women without endometriosis.

Furthermore, women with advanced endometriosis (stage 3-4) exhibit

markedly increased levels of IL-1α and IL-6 in the endometrial

fluid compared with those in women without endometriosis (69,70).

In recent years, genomic and epigenomic research in

endometriosis and APS has grown (11,12,21,23,25,71-73),

driven by novel high-throughput technologies that may identify new

potential signatures and therapeutic targets for further

exploration in detail. Notably, Murrin et al (74) performed a systematic analysis of

the contribution of genetics to multimorbidity based on

representative primary care data on 72 chronic diseases, involving

individuals aged ≥65 years from two large primary-care databases.

All diseases were compared between each other in pairs. The study

concluded that most pairs of chronic conditions show evidence of a

shared genetics background and shared pathogenetic mechanisms.

Therefore, it was suggested that the identified patterns of shared

genetics may provide a foundation for future multimorbidity

research. Importantly, the shared genetic polymorphisms have

potential implications for therapeutic interventions and a better

clinical management of the patients, as further analysis of gene

expression patterns and future advanced pharmacogenomic approaches

may refine personalized treatment strategies for women with both

conditions (74).

In a retrospective cohort study of 50,078 women with

endometriosis conducted by Chen et al (17), patients showed a notably increased

risk of APS regardless of the presence or absence of SLE. This is

an interesting but unexpected finding, taking into account that

some of the shared gene polymorphisms identified in the present

study, such as the MTHFR rs1801133 and STAT4

rs7574865 SNPs also represent SLE-associated risk factors (27,75-77).

Notably, STAT4 rs7574865, apart from its association with

the co-occurrence of endometriosis and APS, has been also

associated with the co-occurrence of endometriosis with SLE, RA, AS

and SS (78).

There are a few limitations to be considered in the

present study. Firstly, there is a definite epidemiological lack of

replication studies thus far in the literature, concerning the

development of APS in women with endometriosis in different racial

and/or ethnic populations. Secondly, there is a lack of information

in the literature about the role of the already identified gene

polymorphisms in women with endometriosis and APS of different

ethnic origins. This is an important point, taking into account the

differential level of contribution of the various polymorphisms

involved in the development of these disorders according to the

ancestry of the populations under examination (71,79).

In this framework, in a previous investigation, we showed that the

availability of a number of endometriosis-associated SNPs (302 SNPs

were examined) provided the opportunity for the study of this

condition through SNP genomic disease genomic ‘grammar’ (DGG).

Thus, the genomic pedigree of endometriosis was identified using

its DGG through the reported SNPs for five major groups of the

world human population, including Europeans, Africans, Americans,

East Asians and South Asians, and notable ‘key’ genetic targets of

endometriosis were revealed with the evidence of population-based

heterogeneity (71). Thirdly, the

search strategy was restricted to the English language only;

therefore, there is a possibility of excluding eligible studies

published in other languages. Furthermore, the source of the

inter-individual susceptibility to endometriosis or APS does not

lie exclusively in genetics, considering that epigenetics

mechanisms, such as methylation, acetylation, phosphorylation and

modifications to the histone proteins associated with DNA packaging

in chromatin, or others that have been analyzed in APS, are now

widely believed to participate also in the susceptibility to these

diseases (70,80,81).

Regarding APS, hypomethylation of ETS1 and EMP2 genes

in APS neutrophils, downregulation of miR-19b and miR-20a, as well

as significant reduction in methylation of the IL-8 promoter

and significantly increased methylation of the tissue factor

(F3) gene, have been reported so far (80,81).

Thus, the role of potential shared epigenetic factors has to be

investigated in future studies, considering that this issue was

beyond the scope of the present preliminary study.

Despite the high number of environmental exposure

factors identified for endometriosis and APS, no common factors

have been reported so far. Notably, most endometriosis-associated

environmental factors refer to endocrine disruptors and organic

pollutants, such as polyhalogenated aromatic hydrocarbons, tobacco

smoking and exposure to heavy metals, pesticides and organohalogen

compounds (82,83). By contrast, the environmental

triggers for APS refer to bacteria, viruses, parasites, vaccines

and drugs (such as antiepileptic, antipsychotic, antihypertensive,

antiarrhythmic drugs and antibiotics), as well as other factors

that are potentially capable of inducing a variety of pathogenic

aPL antibodies, and causing thrombosis, pregnancy loss and APS

through a range of mechanisms (84).

In conclusion, the observed association between

endometriosis and APS suggests that clinicians and scientists

conducting research on endometriosis need to be aware of potential

subsequent APS when endometriosis is diagnosed. Thus, as suggested

recently, clinicians should review thoroughly the symptoms and

assess risk factors for APS when evaluating women with

endometriosis (17). A better

functional characterization of the disease-associated genes may

lead to the detection of new therapeutic targets for pharmaceutical

intervention and ultimately result in improved therapeutic

management for the patients by designing and producing monoclonal

antibodies targeting selected genes, specific inhibitors or

mimicking molecules. Notably, transcriptomic profiling and analysis

have allowed for improved understanding of the mechanisms

underlying endometriosis and have created opportunities for drug

repurposing (85). As an example,

fenoprofen, an uncommonly prescribed NSAID, was the top therapeutic

candidate for further investigation, which was tested in an

established rat model of endometriosis and successfully alleviated

endometriosis-associated vaginal hyperalgesia (85). In the same framework, the

identification of altered transcriptome signatures in samples from

patients with APS and analysis using bioinformatics tools have

significantly enhanced the understanding of APS pathology and led

to the identification of potential therapeutic targets related to

the role of the IFN pathway in this disease (81). Particularly, the upregulation of

genes associated with IFN pathways suggested the potential for

targeted therapeutic interventions aimed at modulating the IFN

signaling pathway in patients with APS (81). Moreover, the distinct gene

signatures associated with different thrombosis types and disease

manifestations suggested the possibility of further tailored

treatment strategies based on the patient's thrombotic profile

(81). Therefore, integrating

clinical and molecular data using high-throughput technologies, in

combination with the employment of computational and bioinformatics

tools, can advance precision medicine for patients with

endometriosis and APS.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

MIZ, TBT and GNG designed the current study,

searched the literature and drafted the manuscript. MIZ, BCT, GB

and DAS analyzed and organized the data. TBT, BCT, GB and DAS

critically revised the manuscript. All authors have read and

approved the final manuscript. Data authentication is not

applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

MIZ, TBT, BCT, GB and GNG declare that they have no

competing interests. DAS is the Editor-in-Chief for the journal,

but had no personal involvement in the reviewing process, or any

influence in terms of adjudicating on the final decision, for this

article.

References

|

1

|

Sinaii N, Cleary SD, Ballweg ML, Nieman LK

and Stratton P: High rates of autoimmune and endocrine disorders,

fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome and atopic diseases among

women with endometriosis: a survey analysis. Hum Reprod.

17:2715–2724. 2002.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Kvaskoff M, Mu F, Terry KL, Harris HR,

Poole EM, Farland L and Missmer SA: Endometriosis: A high-risk

population for major chronic diseases? Hum Reprod Update.

21:500–516. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Rafi U, Ahmad S, Bokhari SS, Iqbal MA, Zia

A, Khan MA and Roohi N: Association of inflammatory

markers/cytokines with cardiovascular risk manifestation in

patients with endometriosis. Mediators Inflamm.

2021(3425560)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Surrey ES, Soliman AM, Johnson SJ, Davis

M, Castelli-Haley J and Snabes MC: Risk of developing comorbidities

among women with endometriosis: A retrospective matched cohort

study. J Women's Health (Larchmt). 27:1114–1123. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Shigesi N, Kvaskoff M, Kirtley S, Feng Q,

Fang H, Knight JC, Missmer SA, Rahmioglu N, Zondervan KT and Becker

CM: The association between endometriosis and autoimmune diseases:

A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update.

25:486–503. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Yin Z, Low HY, Chen BS, Huang KS, Zhang Y,

Wang YH, Ye Z and Wei JCC: Risk of ankylosing spondylitis in

patients with endometriosis: A population-based retrospective

cohort study. Front Immunol. 13(877942)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Zervou MI, Vlachakis D, Papageorgiou L,

Eliopoulos E and Goulielmos GN: Increased risk of rheumatoid

arthritis in patients with endometriosis: Genetic aspects.

Rheumatology (Oxford). 61:4252–4262. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Zervou MI, Papageorgiou L, Vlachakis D,

Spandidos DA, Eliopoulos E and Goulielmos GN: Genetic factors

involved in the co-occurrence of endometriosis with ankylosing

spondylitis (review). Mol Med Rep. 27(96)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Zervou MI, Tarlatzis BC, Grimbizis GF,

Spandidos DA, Niewold TB and Goulielmos GN: Association of

endometriosis with Sjögren's syndrome: Genetic insights (review).

Int J Mol Med. 53(20)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

As-Sanie S, Mackenzie SC, Morrison L,

Schrepf A, Zondervan KT, Horne AW and Missmer SA: Endometriosis: A

review. JAMA. 334:64–78. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Symons LK, Miller JE, Kay VR, Marks RM,

Liblik K, Koti M and Tayade C: The immunopathophysiology of

endometriosis. Trends Mol Med. 24:748–762. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Zondervan KT, Becker CM, Koga K, Missmer

SA, Taylor RN and Viganò P: Endometriosis. Nat Rev Dis Primers.

4(9)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Abramiuk M, Grywalska E, Małkowska P,

Sierawska O, Hrynkiewicz R and Niedźwiedzka-Rystwej P: The role of

the immune system in the development of endometriosis. Cells.

11(2028)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Eisenberg VH, Zolti M and Soriano D: Is

there an association between autoimmunity and endometriosis?

Autoimmun Rev. 11:806–814. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Lebovic DI, Mueller MD and Taylor RN:

Immunobiology of endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 75:1–10.

2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Matarese G, De Placido G, Nikas Y and

Alviggi C: Pathogenesis of endometriosis: Natural immunity

dysfunction or autoimmune disease? Trends Mol Med. 9:223–228.

2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Chen Z, Cui R, Wang SI, Zhang H, Chen M,

Wang Q, Tong Q, Wei JCC and Dai SM: Increased risk of subsequent

antiphospholipid syndrome in patients with endometriosis. Int J

Epidemiol. 54(dyae167)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Clark KEN and Giles I: Antiphospholipid

syndrome. Medicine. 46:118–125. 2018.

|

|

19

|

Sciascia S, Amigo MC, Roccatello D and

Khamashta M: Diagnosing antiphospholipid syndrome: ‘Extra-criteria’

manifestations and technical advances. Nat Rev Rheumatol.

13:548–560. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Rodríguez-García V, Ioannou Y,

Fernández-Nebro A, Isenberg DA and Giles IP: Examining the

prevalence of non-criteria anti-phospholipid antibodies in patients

with anti-phospholipid syndrome: A systematic review. Rheumatology

(Oxford). 54:2042–2050. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Celia AI, Galli M, Mancuso S, Alessandri

C, Frati G, Sciarretta S and Conti F: Antiphospholipid syndrome:

Insights into molecular mechanisms and clinical manifestations. J

Clin Med. 13(4191)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Ravindran V, Rajendran S and Elias G:

Primary antiphospholipid syndrome in monozygotic twins. Lupus.

22:92–94. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Lopez-Pedrera C, Barbarroja N,

Patiño-Trives AM, Collantes E, Aguirre MA and Perez-Sanchez C: New

biomarkers for atherothrombosis in antiphospholipid syndrome:

Genomics and epigenetics approaches. Front Immunol.

10(764)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Zubrzycka A, Zubrzycki M, Perdas E and

Zubrzycka M: Genetic, epigenetic, and steroidogenic modulation

mechanisms in endometriosis. J Clin Med. 9(1309)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Barinotti A, Radin M, Cecchi I, Foddai SG,

Rubini E, Roccatello D, Sciascia S and Menegatti E: Genetic factors

in antiphospholipid syndrome: Preliminary experience with whole

exome sequencing. Int J Mol Sci. 21(9551)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Gómez-Puerta JA and Cervera R: Diagnosis

and classification of the antiphospholipid syndrome. J Autoimmun.

48-49:20–25. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Zervou MI, Matalliotakis M and Goulielmos

GN: Comment on ‘Risk of systemic lupus erythematosus in patients

with endometriosis: A nationwide population-based cohort study’.

Arch Gynecol Obstet. 305:543–544. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Goulielmos GN, Tarlatzi TB, Grimbizis GF,

Spandidos DA, Niewold TB, Bertsias G, Tarlatzis BC and Zervou MI:

Co-occurrence of endometriosis with psoriasis and psoriatic

arthritis: Genetic insights (review). Exp Ther Med.

30(171)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Domenico Sebastiani G, Minisola G and

Galeazzi M: HLA class II alleles and genetic predisposition to the

antiphospholipid syndrome. Autoimmun Rev. 2:387–394.

2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Ishii K, Takakuwa K, Kashima K, Tamura M

and Tanaka K: Associations between patients with endometriosis and

HLA class II; the analysis of HLA-DQB1 and HLA-DPB1 genotypes. Hum

Reprod. 18:985–989. 2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Zong L, Pan D, Chen W, He Y, Liu Z, Lin J

and Xu A: Comparative study of HLA-DQA1 and HLA-DRB1 allele in

patients with endometriosis and adenomyosis. Zhonghua Yi Xue Yi

Chuan Xue Za Zhi. 19:49–51. 2002.PubMed/NCBI(In Chinese).

|

|

32

|

Bedaiwy MA, Falcone T and Casper RF:

Plasminogen activator inhibitor (PAI) and thrombin activatable

fibrinolysis inhibitor (TAFI) Polymorphisms in women with

endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 84 (Suppl 1):S189–S190. 2005.

|

|

33

|

Aisina RB, Mukhametova LI, Ostryakova EV,

Seredavkina NV, Patrushev LI, Patrusheva NL, Reshetnyak TM, Gulin

DA, Gershkovich KB, Nasonov EL and Varfolomeyev SD: Polymorphism of

the plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1 gene, plasminogen level

and thromboses in patients with the antiphospholipid syndrome.

Biochem Suppl Ser B Biomed Chem. 7:1–15. 2013.

|

|

34

|

Sayfutdinovich KZ, Shakarimovna AD,

Rudolfovna KT and Erkinovna ZN: Association of MTHFR and MTRR genes

with the development of antiphospholipid syndrome in pregnant women

of Uzbek population. Eur Sci Rev. 7-8:85–87. 2016.

|

|

35

|

Delli Carpini G, Giannella L, Di Giuseppe

J, Montik N, Montanari M, Fichera M, Crescenzi D, Marzocchini C,

Meccariello ML, Di Biase D, et al: Homozygous C677T

methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) polymorphism as a risk

factor for endometriosis: A retrospective case-control study. Int J

Mol Sci. 24(15404)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Bianco B, Fernandes RFM, Trevisan CM,

Christofolini DM, Sanz-Lomana CM, de Bernabe JV and Barbosa CP:

Influence of STAT4 gene polymorphisms in the pathogenesis of

endometriosis. Ann Hum Genet. 83:249–255. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Horita T, Atsumi T, Yoshida N, Nakagawa H,

Kataoka H, Yasuda S and Koike T: STAT4 single nucleotide

polymorphism, rs7574865 G/T, as a risk for antiphospholipid

syndrome. Ann Rheum Dis. 68:1366–1367. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Latha M, Vaidya S, Movva S, Chava S,

Govindan S, Govatati S, Banoori M, Hasan Q and Kodati VL: Molecular

pathogenesis of endometriosis; Toll-like receptor-4 A896G (D299G)

polymorphism: A novel explanation. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers.

15:181–184. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Pierangeli SS, Vega-Ostertag ME, Raschi E,

Liu X, Romay-Penabad Z, De Micheli V, Galli M, Moia M, Tincani A,

Borghi MO, et al: Toll-like receptor and antiphospholipid mediated

thrombosis: In vivo studies. Ann Rheum Dis. 66:1327–1333.

2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Carey BS, Poulton KV and Poles A: Factors

affecting HLA expression: A review. Int J Immunogenet. 46:307–320.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Ali AM, Nader MI, Al-Ghurabi BH and

Mohammed AK: Association of HLA class II alleles (DRB1 and DQB1) in

Iraqi women with endometriosis. Iraqi J Biotechnol. 15:42–50.

2016.

|

|

42

|

Ioannidis JP, Tektonidou MG,

Vlachoyiannopoulos PG, Stavropoulos-Giokas C, Spyropoulou-Vlachou

M, Reveille JD, Arnett FC and Moutsopoulos HM: HLA associations of

anti-beta2 glycoprotein I response in a Greek cohort with

antiphospholipid syndrome and meta-analysis of four ethnic groups.

Hum Immunol. 60:1274–1280. 1999.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Mansilha A, Araújo F, Severo M, Sampaio

SM, Toledo T, Henriques I and Albuquerque R: The association

between the 4G/5G polymorphism in the promoter of the plasminogen

activator inhibitor-1 gene and deep venous thrombosis in young

people. Phlebology. 20:48–52. 2005.

|

|

44

|

Dossenbach-Glaninger A, van Trotsenburg M,

Dossenbach M, Oberkanins C, Moritz A, Krugluger W, Huber J and

Hopmeier P: Plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 4G/5G polymorphism

and coagulation factor XIII Val34Leu polymorphism: Impaired

fibrinolysis and early pregnancy loss. Clin Chem. 49:1081–1086.

2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Islam MA, Khandker SS, Alam F, Kamal MA

and Gan SH: Genetic risk factors in thrombotic primary

antiphospholipid syndrome: A systematic review with bioinformatic

analyses. Autoimmun Rev. 17:226–243. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Raghubeer S and Matsha TE:

Methylenetetrahydrofolate (MTHFR), the one-carbon cycle, and

cardiovascular risks. Nutrients. 13(4562)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Guedes T, Santos AA, Vieira-Neto FH,

Bianco B, Barbosa CP and Christofolini DM: Folate metabolism

abnormalities in infertile patients with endometriosis. Biomark

Med. 16:549–557. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Luo Z, Lu Z, Muhammad C, Chen Y, Chen Q,

Zhang J and Song Y: Associations of the MTHFR rs1801133

polymorphism with coronary artery disease and lipid levels: A

systematic review and updated meta-analysis. Lipids Health Dis.

17(191)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Wu S, Wang M, Wang Y, Zhang M and He JQ:

Polymorphisms of the STAT4 gene in the pathogenesis of

tuberculosis. Biosci Rep. 38(BSR20180498)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Korman BD, Kastner DL, Gregersen PK and

Remmers EF: STAT4: Genetics, mechanisms, and implications for

autoimmunity. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 8:398–403. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Liang YL, Wu H, Shen X, Li PQ, Yang XQ,

Liang L, Tian WH, Zhang LF and Xie XD: Association of STAT4

rs7574865 polymorphism with autoimmune diseases: A meta-analysis.

Mol Biol Rep. 39:8873–8882. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Bravo-Villagra KM, Muñoz-Valle JF,

Baños-Hernández CJ, Cerpa-Cruz S, Navarro-Zarza JE, Parra-Rojas I,

Aguilar-Velázquez JA, García-Arellano S and López-Quintero A: STAT4

gene variant rs7574865 is associated with rheumatoid arthritis

activity and anti-CCP levels in the western but not in the southern

population of Mexico Mexico. Genes (Basel). 15(241)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Podgaec S, Dias Junior JA, Chapron C, de

Oliveira RM, Baracat EC and Abrão MS: Th1 and Th2 ummune responses

related to pelvic endometriosis. Assoc Med Bras (1992). 56:92–98.

2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Medzhitov R and Janeway C Jr: Innate

immunity. N Engl J Med. 343:338–344. 2000.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Ozato K, Tsujimura H and Tamura T:

Toll-like receptor signaling and regulation of cytokine gene

expression in the immune system. BioTechniques. 33 (Suppl):S66–S75.

2002.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Poltorak A, Smirnova I, He X, Liu MY, Van

Huffel C, McNally O, Birdwell D, Alejos E, Silva M, Du X, et al:

Genetic and physical mapping of the Lps locus: Identification of

the toll-4 receptor as a candidate gene in the critical region.

Blood Cells Mol Dis. 24:340–355. 1998.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Akira S, Uematsu S and Takeuchi O:

Pathogen recognition and innate immunity. Cell. 124:783–801.

2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

58

|

Kim HJ, Kim H, Lee JH and Hwangbo C:

Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4): New insight immune and aging. Immun

Ageing. 20(67)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

59

|

Yamakawa N, Ohto U, Akashi-Takamura S,

Takahashi K, Saitoh S, Tanimura N, Suganami T, Ogawa Y, Shibata T,

Shimizu T and Miyake K: Human TLR4 polymorphism D299G/T399I alters

TLR4/MD-2 conformation and response to a weak ligand monophosphoryl

lipid A. Int Immunol. 25:45–52. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

60

|

Khan KN, Kitajima M, Fujishita A,

Nakashima M and Masuzaki H: Toll-like receptor system and

endometriosis. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 39:1281–1292. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

61

|

Anwar MA and Choi S: Structure-activity

relationship in TLR 4 mutations: Atomistic molecular dynamics

simulations and residue interaction network analysis. Sci Rep.

7(43807)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

62

|

Benhamou Y, Bellien J, Armengol G,

Brakenhielm E, Adriouch S, Iacob M, Remy-Jouet I, Le Cam-Duchez V,

Monteil C, Renet S, et al: Role of Toll-like receptors 2 and 4 in

mediating endothelial dysfunction and arterial remodeling in

primary arterial antiphospholipid syndrome. Arthritis Rheum.

66:3210–3220. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

63

|

Palli E, Kravvariti E and Tektonidou MG:

Type I interferon signature in primary antiphospholipid syndrome:

Clinical and laboratory associations. Front Immunol.

10(487)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

64

|

Tang KT, Chen HH, Chen TT, Bracci NR and

Lin CC: Dendritic cells and antiphospholipid syndrome: An updated

systematic review. Life (Basel). 11(801)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

65

|

Wu XG, Chen JJ, Zhou HL, Wu Y, Lin F, Shi

J, Wu HZ, Xiao HQ and Wang W: Identification and validation of the

signatures of infiltrating immune cells in the eutopic endometrium

endometria of women with endometriosis. Front Immunol.

12(671201)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

66

|

Ahn SH, Khalaj K, Young SL, Lessey BA,

Koti M and Tayade C: Immune-inflammation gene signatures in

endometriosis patients. Fertil Steril. 106:1420–1431.e7.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

67

|

Hubben AK, Bazeley P, Swaidani S, Alarabi

A, Kulkarni PP, Shim YJ, Palihati M, Barnard J and Mccrae KR:

Cytokine profiling in antiphospholipid syndrome demonstrates

persistent immune dysregulation and a procoagulant phenotype.

Blood. 142 (Suppl 1)(S5400)2023.

|

|

68

|

Yan H, Li B, Su R, Gao C, Li X and Wang C:

Preliminary study on the imbalance between Th17 and regulatory T

cells in antiphospholipid syndrome. Front Immunol.

13(873644)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

69

|

Llarena NC, Richards EG, Priyadarshini A,

Fletcher D, Bonfield T and Flyckt RL: Characterizing the

endometrial fluid cytokine profile in women with endometriosis. J

Assist Reprod Genet. 37:2999–3006. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

70

|

Oală IE, Mitranovici MI, Chiorean DM,

Irimia T, Crișan AI, Melinte IM, Cotruș T, Tudorache V, Moraru L,

Moraru R, et al: Endometriosis and the Role of Pro-Inflammatory and

Anti-Inflammatory Cytokines in Pathophysiology: A narrative review

of the literature. Diagnostics (Basel). 14(312)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

71

|

Papageorgiou L, Andreou A, Zervou M,

Vlachakis D, Goulielmos GN and Eliopoulos E: A global population

genomic analysis shows novel insights into the genetic

characteristics of endometriosis. World Acad Sci J. 5(12)2023.

|

|

72

|

Goulielmos GN, Matalliotakis M,

Matalliotaki C, Eliopoulos E, Matalliotakis I and Zervou MI:

Endometriosis research in the-omics era. Gene.

741(144545)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

73

|

Zouein J, Naim N, Spencer DM and Ortel TL:

Genetic and genomic associations in antiphospholipid syndrome: A

systematic review. Autoimmun Rev. 24(103712)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

74

|

Murrin O, Mounier N, Voller B, Tata L,

Gallego-Moll C, Roso-Llorach A, Carrasco-Ribelles LA, Fox C, Allan

LM, Woodward RM, et al: A systematic analysis of the contribution

of genetics to multimorbidity and comparisons with primary care

data. EBioMedicine. 113(105584)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

75

|

Remmers EF, Plenge RM, Lee AT, Graham RR,

Hom G, Behrens TW, de Bakker PIW, Le JM, Lee HS, Batliwalla F, et

al: STAT4 and the risk of rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus

erythematosus. N Engl J Med. 357:977–986. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

76

|

Zhou HY and Yuan M: MTHFR polymorphisms

(rs1801133) and systemic lupus erythematosus risk: A meta-analysis.

Medicine (Baltimore). 99(e22614)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

77

|

Chen L, Huang Z, Liao Y, Yang B and Zhang

J: Association between tumor necrosis factor polymorphisms and

rheumatoid arthritis as well as systemic lupus erythematosus: A

meta-analysis. Braz J Med Biol Res. 52(e7927)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

78

|

Zervou MI and Goulielmos GN: Comment on:

Enhancing current guidance for psoriatic arthritis and its

comorbidities: Recommendations from an expert consensus panel.

Rheumatology (Oxford). 64:904–905. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

79

|

Uthman I and Khamashta M: Ethnic and

geographical variation in antiphospholipid (Hughes) syndrome. Ann

Rheum Dis. 64:1671–1676. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

80

|

Weeding E, Coit P, Yalavarthi S, Kaplan

MJ, Knight JS and Sawalha AH: Genome-wide DNA methylation analysis

in primary antiphospholipid syndrome neutrophils. Clin Immunol.

196:110–116. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

81

|

López-Pedrera C, Cerdó T, Jury EC,

Muñoz-Barrera L, Escudero-Contreras A, Aguirre MA and Pérez-Sánchez

C: New advances in genomics and epigenetics in antiphospholipid

syndrome. Rheumatology (Oxford). 63 (SI):SI14–SI23. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

82

|

Caporossi L, Capanna S, Viganò P, Alteri A

and Papaleo B: From environmental to possible occupational exposure

to risk factors: What role do they play in the etiology of

endometriosis? Int J Environ Res Public Health.

18(532)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

83

|

Matta K, Lefebvre T, Vigneau E, Cariou V,

Marchand P, Guitton Y, Royer AL, Ploteau S, Le Bizec B, Antignac JP

and Cano-Sancho G: Associations between persistent organic

pollutants and endometriosis: A multiblock approach integrating

metabolic and cytokine profiling. Environ Int.

158(106926)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

84

|

Martirosyan A, Aminov R and Manukyan G:

Environmental triggers of autoreactive responses: Induction of

antiphospholipid antibody formation. Front Immunol.

10(1609)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

85

|

Oskotsky TT, Bhoja A, Bunis D, Le BL, Tang

AS, Kosti I, Li C, Houshdaran S, Sen S, Vallvé-Juanico J, et al:

Identifying therapeutic candidates for endometriosis through a

transcriptomics-based drug repositioning approach. iScience.

27(109388)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|