Introduction

Treatment options for wide-necked anterior

communicating artery (ACoA) aneurysms include open surgical

clipping and endovascular embolization. While surgical clipping

offers robust aneurysm occlusion, endovascular techniques are

increasingly preferred due to lower complication rates and

favorable clinical outcomes (1).

Despite these advantages, wide-necked ACoA aneurysms present

technical challenges during endovascular intervention, primarily

due to the risk of coil protrusion into the parent vessel.

Therefore, adjunctive techniques such as stent-assisted or

balloon-assisted coiling are frequently used. Stent-assisted

coiling effectively prevents coil protrusion, improving the

completeness and durability of embolization (2). However, the need for antiplatelet

therapy following stent placement may increase the risk of

rebleeding in patients with ruptured aneurysms (3,4).

Other techniques, such as balloon remodeling and

triple-microcatheter techniques, have been employed to mitigate

coil protrusion (5,6). However, each has inherent

limitations. Balloon remodeling in ACoA aneurysms requires

temporary flow arrest, increasing the risk of ischemia,

particularly in patients with a unilaterally dominant A1 segment.

Furthermore, the small caliber and limited luminal space of the

anterior cerebral arteries render triple-microcatheter techniques

technically challenging (7). In

the present study, a modified technique using dual microcatheter

and guidewire support is described to address these limitations and

provide a less complex, potentially safer alternative. This method

offers vessel protection and enables successful coil embolization

without adjunctive devices, thereby minimizing stent-related risks

and procedural complexity.

Case report

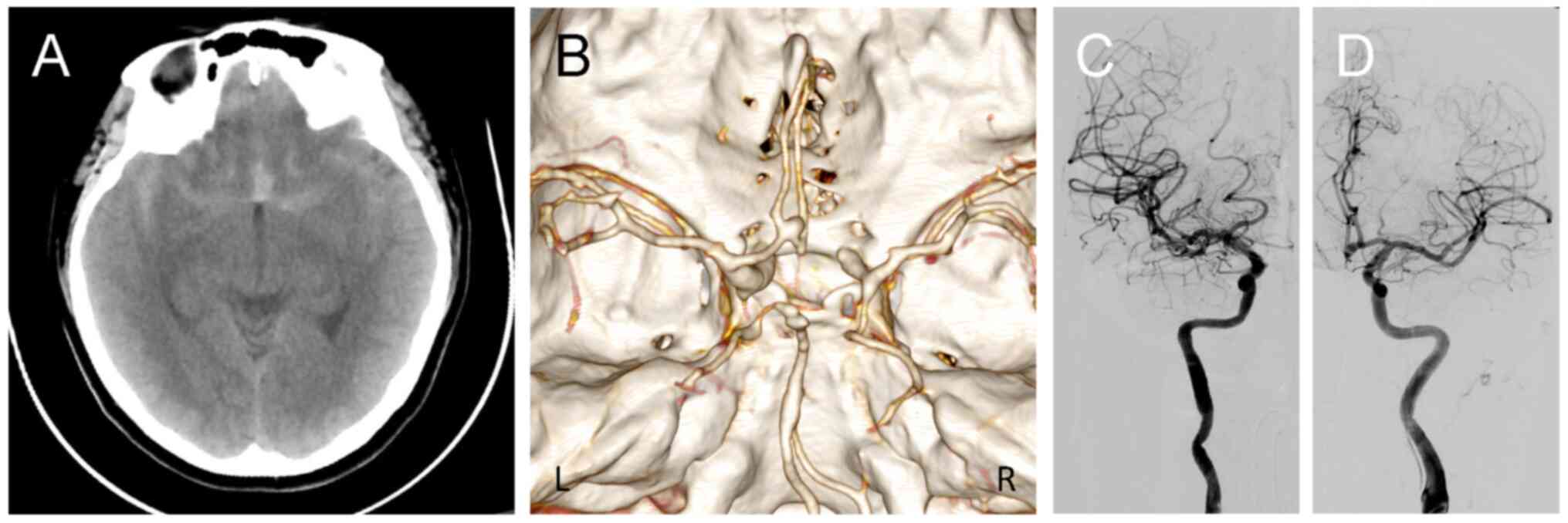

A 36-year-old female presented with the sudden onset

of a severe headache. Non-contrast computed tomography (CT)

performed at a local hospital in September 2024 revealed

subarachnoid hemorrhage, predominantly in the interhemispheric

fissure, with a modified Fisher grade of 2 (Fig. 1A). CT angiography further

demonstrated an ACoA aneurysm (Fig.

1B).

Following the initial evaluation, the patient was

transferred to Beijing Anzhen Nanchong Hospital of Capital Medical

University & Nanchong Central Hospital (Nanchong, China) later

that day. Upon admission, neurological examination was unremarkable

and the patient was classified as World Federation of Neurological

Surgeons Grade 1. After a discussion of treatment options, the

patient declined surgical clipping and opted for endovascular

intervention. Diagnostic cerebral angiography confirmed an ACoA

aneurysm predominantly supplied by the left anterior cerebral

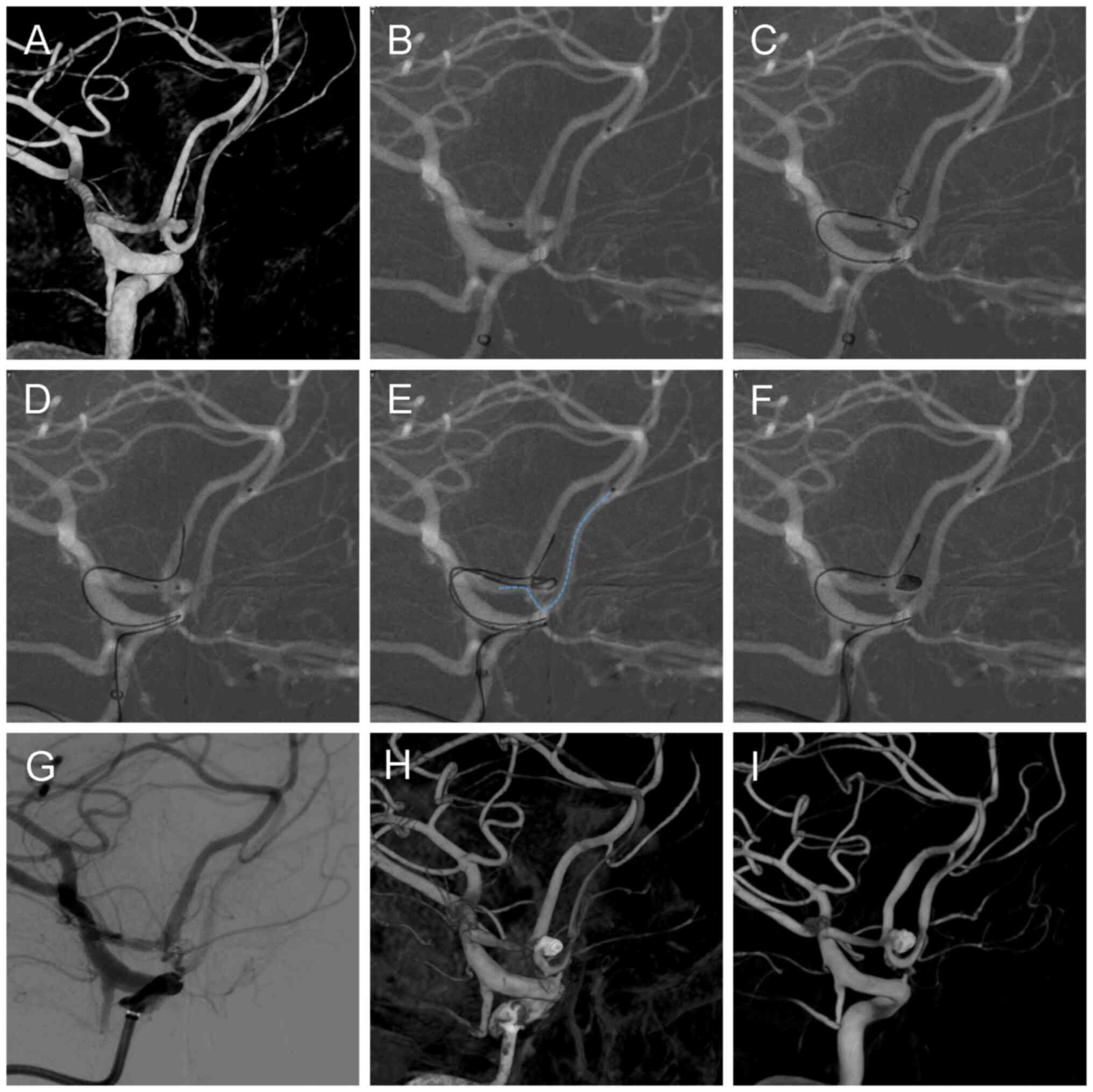

artery (Fig. 1C and D). Three-dimensional (3D) rotational

angiography revealed a wide-necked aneurysm measuring ~4x3x3 mm

(width x depth x height), with a dome-to-neck ratio of 1.2

(Fig. 2A). No pretreatment with

dual antiplatelet agents was administered. The procedure was

performed under general anesthesia with continuous nimodipine

infusion at 5 ml/h. A right 8F femoral sheath (Terumo Corporation)

was inserted and a 6F 115-cm intracranial support catheter

(Tonbridge Medical Technology Co., Ltd.) was advanced into the

distal internal carotid artery at the C4 segment. Following

vascular access, systemic heparinization was initiated with a 5,000

U bolus, followed by maintenance at 1,000 U/h.

Due to the left-sided dominance of the ACoA

aneurysm's inflow and its morphology, stent deployment, if

required, would necessitate crossing from the ACoA to the

contralateral (right) A2 segment to cover the aneurysm neck

adequately. To prepare for this contingency, a Synchro 14 guidewire

(Stryker Neurovascular) was used to advance a Headway 17

microcatheter (MicroVention, Inc.) into the distal right A2

segment, positioning it for potential deployment of a Neuroform

Atlas stent (Stryker Neurovascular) (Fig. 2B). A second Headway 17

microcatheter (MicroVention, Inc.) was introduced into the aneurysm

sac for coil embolization. However, during deployment of the

initial coil, protrusion into the left A2 segment occurred despite

multiple attempts (Fig. 2C). To

address this coil protrusion, a Synchro 14 guidewire (Stryker

Neurovascular) was inserted through the y-connector hemostasis

valve (Merit Medical Systems, Inc.) of the stent microcatheter and

navigated through the intracranial support catheter to a position

distal to the left A2 segment (Fig.

2D). The guidewire tip was shaped ~1.5 cm from its distal end

to optimize its conformation to the aneurysm neck, forming a stable

‘guardrail’ configuration at the aneurysm orifice. This Y-shaped

configuration of the guidewire and microcatheter enabled stable

coil framing without protrusion (Fig.

2E), leading to complete aneurysm occlusion without stent

deployment (Fig. 2F). Given the

instability typically associated with aneurysms of this

configuration, strict adherence to a defined withdrawal sequence

was essential to maintain coil stability (8). After confirming final coil

detachment, the distal tip of the coil pusher was kept slightly

extended beyond the microcatheter tip to facilitate the release of

the coil tail and prevent displacement. The guidewire was then

carefully withdrawn, followed by the gradual withdrawal of the

coiling microcatheter. Finally, the stent microcatheter was

withdrawn at a slow and controlled pace. Continuous digital

subtraction angiography (DSA) was performed throughout the

withdrawal process to monitor coil mass stability and ensure no

displacement or protrusion.

Post-embolization 2D (Fig. 2G) and 3D (Fig. 2H) rotational angiography

demonstrated satisfactory aneurysm occlusion, with patent bilateral

A2 segments and no evidence of distal thromboembolic complications.

The operative procedure is documented in Video S1.

The patient was discharged one week postoperatively

without hemiparesis or cognitive deficits and resumed routine

activities, including work. The modified Rankin Scale score was 0.

At the six-month follow-up, DSA demonstrated stable coil placement

with continued patency of the bilateral anterior cerebral arteries

(Fig. 2I).

Discussion

Stent-assisted coiling for ruptured aneurysms

presents significant challenges compared to coil embolization

alone. The requirement for dual antiplatelet therapy increases the

risk of post-procedural rebleeding, particularly in cases involving

external ventricular drains (4).

Alternative endovascular strategies, including

multi-catheter and balloon-assisted techniques, have their own

limitations. Multiple microcatheter techniques frequently require

removing previously placed catheters, necessitating upsizing a 7F

or 8F access sheath. This approach escalates procedural complexity,

duration and cost. Furthermore, the small caliber of the anterior

cerebral arteries renders multi-catheter navigation technically

challenging or unfeasible. When balloon remodeling fails to achieve

adequate neck control, the lack of readily deployable stent bailout

heightens the risk of coil protrusion (9).

The documented dual-catheter technique involves an

adjunctive microcatheter that facilitates partial aneurysm neck

occlusion to reduce coil migration and enhance framing (8). However, our initial experience with

this technique revealed critical limitations: The stent

microcatheter prevented coil protrusion into the right anterior

cerebral artery A2 segment but not into the left. Based on the

aforementioned technical enhancements, a combined microcatheter and

guidewire technique was developed and implemented in the present

study to overcome the challenges associated with treating ruptured

wide-necked ACoA aneurysms. This novel approach, developed in our

study, modifies the adjunctive microcatheter technique by

incorporating a guidewire for enhanced support. This technique

employs the strategic combination of guidewire and microcatheter

placement to establish a ‘Y’-shaped configuration that functions as

a dual-support ‘physical barrier’. This configuration thereby

facilitates stable coil framing within the anterior communicating

artery aneurysm while preventing coil protrusion into the parent

vessel. The contrast between our initial and refined approaches

demonstrates the technique's evolution: While the auxiliary method

failed due to incomplete neck coverage, the microcatheter-guidewire

combination achieved complete neck sealing and procedural

efficacy.

This technology boasts broad clinical applicability,

accommodating a wide range of patient populations, and is generally

not constrained by the inherent disease severity or coexisting

comorbidities. However, procedural success and safety remain

contingent upon individual intracranial vascular anatomy and

pathophysiology. Several technical challenges may arise. Primarily,

long-distance microcatheter navigation through cerebral vasculature

frequently diminishes torque transmission and pushability,

compromising tactile feedback. This is particularly pronounced in

tortuous vessels, necessitating intermediate catheter deployment

for optimal maneuverability. Furthermore, simultaneous operation of

two microcatheters and one micro guidewire reduces intraluminal

space, predisposing to entanglement and knotting. Mitigation

strategies include avoiding complex microcatheter shaping and

sequential delivery with microcatheter positioning preceding

microwire advancement. Additionally, patients with compromised

cerebrovascular architecture, particularly those with

atherosclerotic burden, vessel tortuosity or significant stenosis,

demonstrate heightened susceptibility to thromboembolic

complications and plaque disruption during manipulation (10-13).

Risk mitigation encompasses prophylactic anticoagulation and

precision navigation under continuous fluoroscopic monitoring

(14).

Of note, there are currently no specific training

programs or simulation methods dedicated to mastering the present

technique, to the best of our knowledge. This procedure may have a

certain learning curve and appear somewhat complex for beginners.

However, experienced neurointerventional physicians may be able to

acquire proficiency in this technique quickly and efficiently due

to their foundational skills and experience with similar

procedures.

This technique demonstrates several distinct

advantages, as demonstrated in the present case. First, it

eliminates the need to upsize the access sheath, allowing the

procedure to be completed via a standard 6F system. This allows for

further advancement of a guidewire to the A2 segment of the

anterior cerebral artery without removing pre-existing long

sheaths, intracranial support catheters and microcatheters. This

minimizes catheter exchanges, thereby reducing procedural steps and

mitigating the risk of vascular injury associated with repeated

device manipulation. Second, it provides optimal support to both A2

segments of the anterior cerebral arteries, thereby minimizing the

risk of coil protrusion and facilitating successful embolization

without requiring adjunctive devices such as stents or balloons.

Third, compared to balloon remodeling, this technique better

preserves cerebral perfusion throughout the procedure (5).

However, certain limitations and risks must be

acknowledged. Despite the enhanced stability afforded by this

technique, the potential for coil migration or incomplete aneurysm

occlusion persists. In such scenarios, stent deployment remains a

viable contingency option to ensure coil retention and prevent

protrusion. Furthermore, compared to stent-assisted coiling, coil

embolization alone shows superior immediate occlusion rates and

better prevents rebleeding in ruptured aneurysms. However, coil

embolization alone may be associated with higher recurrence rates

over time (15,16). The absence of extended follow-up is

a limitation of the present study. Extended follow-up is essential

to confirm the long-term stability and efficacy of the

treatment.

In conclusion, ruptured wide-necked bifurcation

aneurysms, such as those of the ACoA, carry a substantial risk of

coil protrusion when treated with coil embolization alone. This

report details an improved technique employing dual microcatheter

and guidewire support via a 6F access system to embolize select

ruptured wide-necked ACoA aneurysms, obviating the need for

adjunctive devices. In the presented case, this technique proved

safe and effective. However, stent deployment remains a viable

bailout strategy in select complex cases.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Data.

Coil embolization of an anterior

communicating artery aneurysm using combined microcatheter and

guidewire technique.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

HT performed the surgery as the lead surgeon. HT and

ZL were involved in the conception and design of the study, were

responsible for the project and provided final approval of the

manuscript. ZL, CC and YZ collected, acquired and interpreted the

data. HT, MS and ZL wrote the manuscript. HT, ZL and MS critically

revised the article. HT and MS were responsible for creating and

assembling the figures. HT and ZL edited the supplementary video.

HT and ZL verified the authenticity of the raw data. All authors

have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Written informed consent was obtained from the

patient and their family for the proposed treatment.

Patient consent for publication

Written consent was obtained from the patient and

family for the publication of the patient's case information and

images. All identifying patient information has been removed to

ensure confidentiality.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Sattari SA, Shahbandi A, Lee RP, Feghali

J, Rincon-Torroella J, Yang W, Abdulrahim M, Ahmadi S, So RJ, Hung

A, et al: Surgery or endovascular treatment in patients with

anterior communicating artery aneurysm: A systematic review and

meta-analysis. World Neurosurg. 175:31–44. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Kocur D, Ślusarczyk W, Przybyłko N,

Bażowski P, Właszczuk A and Kwiek S: Stent-Assisted endovascular

treatment of anterior communicating artery aneurysms-literature

review. Pol J Radiol. 81:374–379. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Proust F, Martinaud O, Gérardin E, Derrey

S, Levèque S, Bioux S, Tollard E, Clavier E, Langlois O, Godefroy

O, et al: Quality of life and brain damage after microsurgical clip

occlusion or endovascular coil embolization for ruptured anterior

communicating artery aneurysms: Neuropsychological assessment. J

Neurosurg. 110:19–29. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Zhao B, Tan X, Yang H, Zheng K, Li Z,

Xiong Y and Zhong M: AMPAS study group. Stent-assisted coiling

versus coiling alone of poor-grade ruptured intracranial aneurysms:

A multicenter study. J Neurointerv Surg. 9:165–168. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Moon K, Albuquerque FC, Ducruet AF,

Crowley RW and McDougall CG: Balloon remodeling of complex anterior

communicating artery aneurysms: Technical considerations and

complications. J Neurointerv Surg. 7:418–424. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Cho YD, Rhim JK, Kang HS, Park JJ, Jeon

JP, Kim JE, Cho WS and Han MH: Use of triple microcatheters for

endovascular treatment of wide-necked intracranial aneurysms: A

single center experience. Korean J Radiol. 16:1109–1118.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Chung EJ, Shin YS, Lee CH, Song JH and

Park JE: Comparison of clinical and radiologic outcomes among

stent-assisted, double-catheter, and balloon-assisted coil

embolization of wide neck aneurysms. Acta Neurochir (Wien).

156:1289–1295. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Muralidharan V, Travali M, Cavallaro TL,

Tomarchio L, Corsale G, Cosentino F, Politi MA and Cristaudo C:

Micro-catheter assisted coiling (MAC) A mid-path between simple and

assisted coiling techniques in treating ruptured wide neck

aneurysms and immediate post procedure outcomes. J Cerebrovasc Sci.

9:3–8. 2021.

|

|

9

|

Ladner TR, He L, Davis BJ, Froehler MT and

Mocco J: Simultaneous stent expansion/balloon deflation technique

to salvage failed balloon remodeling. BMJ Case Rep.

2015(bcr2014011600)2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Kim SH, Nam TM, Lee SH, Jang JH, Kim YZ,

Kim KH, Kim DH and Lee CH: Association of aortic arch calcification

on chest X-ray with procedural thromboembolism after coil

embolization of cerebral aneurysm. J Clin Neurosci. 99:373–378.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Ogata A, Suzuyama K, Ebashi R, Takase Y,

Inoue K, Masuoka J, Yoshioka F, Nakahara Y and Abe T: Association

between extracranial internal carotid artery tortuosity and

thromboembolic complications during coil embolization of anterior

circulation ruptured aneurysms. Acta Neurochir (Wien).

161:1175–1181. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Park CK, Shin HS, Choi SK, Lee SH and Koh

JS: Clinical analysis and surgical considerations of

atherosclerotic cerebral aneurysms: Experience of a single center.

J Cerebrovasc Endovasc Neurosurg. 16:247–253. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Yin Z, Zhang Q, Zhao Y, Lu J, Ge P, Xie H,

Wu D, Yu S, Kang S, Zhang Q, et al: Prevalence and procedural risk

of intracranial atherosclerotic stenosis coexisting with unruptured

intracranial aneurysm. Stroke. 54:1484–1493. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Ihn YK, Shin SH, Baik SK and Choi IS:

Complications of endovascular treatment for intracranial aneurysms:

Management and prevention. Interv Neuroradiol. 24:237–245.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Hong Y, Wang YJ, Deng Z, Wu Q and Zhang

JM: Stent-assisted coiling versus coiling in treatment of

intracranial aneurysm: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS

One. 9(e82311)2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Nabizadeh F, Valizadeh P and Balabandian

M: Stent-assistant versus non-stent-assistant coiling for ruptured

and unruptured intracranial aneurysms: A meta-analysis and

systematic review. World Neurosurg X. 21(100243)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|