Introduction

Choledocholithiasis (CDL), the presence of

gallstones in the common bile duct (CBD), affects approximately

10-15% of patients with cholelithiasis over 10 years (1). In the U.S., gallstone disease

contributes to over 1.2 million emergency department visits

annually (2). The incidence of CDL

is rising, likely due to an aging population and increased use of

diagnostic imaging (3). Prompt and

accurate diagnosis is critical, as undetected CDL can lead to

complications such as cholangitis, pancreatitis, or biliary

obstruction, while unnecessary endoscopic retrograde

cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) may cause iatrogenic harm (4).

While ERCP remains the gold standard for diagnosing

and treating CDL, its invasive nature demands judicious patient

selection (5). The American

Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) revised its risk

stratification criteria in 2019, classifying patients into low,

intermediate, or high-risk groups based on clinical, biochemical,

and imaging data (6,7). However, these criteria have shown

inconsistent accuracy, particularly in high-volume settings,

raising concerns about overuse of ERCP and missed diagnoses

(8).

Artificial intelligence (AI) transforms medicine by

enabling data-driven, personalized care (9). In gastroenterology, AI has been

applied in real-time endoscopic image analysis, polyp detection,

colorectal neoplasia and malignant biliary strictures, and disease

risk stratification (10-12).

Supervised machine learning models (MLMs), such as

gradient-boosting machines (GBMs), learn from labeled input-output

pairs by building and correcting sequential decision trees

(10,13). Deep learning (DL) models, including

artificial neural networks (ANNs) and convolutional neural networks

(CNNs), can integrate diverse clinical inputs such as biochemical

studies and imaging findings, and continuously refine predictions

through iterative learning (10,13).

Unsupervised models, which learn from unlabeled data, are

increasingly used to uncover hidden disease subtypes and patterns

(10,13,14).

Data-driven ML and DL algorithms in diagnosing and

early predicting CDL may improve their therapeutic implementations

and decision-making. Applying AI to CDL diagnosis may reduce

unnecessary ERCP, lower complication rates, and improve outcomes by

enabling noninvasive, individualized risk assessment. However,

evidence of their diagnostic performance remains fragmented. This

systematic review and meta-analysis aim to evaluate AI-assisted

tools' sensitivity, specificity, and overall diagnostic accuracy in

predicting CDL and compare their performance with guideline-based

approaches such as those from the ASGE.

Materials and methods

Search strategy

Two independent investigators systematically

searched MEDLINE, EMBASE, PubMed, and Web of Science from inception

to March 2, 2025. Keywords included ‘Artificial intelligence’,

‘machine learning’, ‘computer-aided diagnosis’, ‘biliary

obstruction’, ‘choledocholithiasis’, and ‘endoscopic retrograde

cholangiopancreatography or ECRP’ with Boolean operators used to

optimize search results. A PRISMA diagram was designed according to

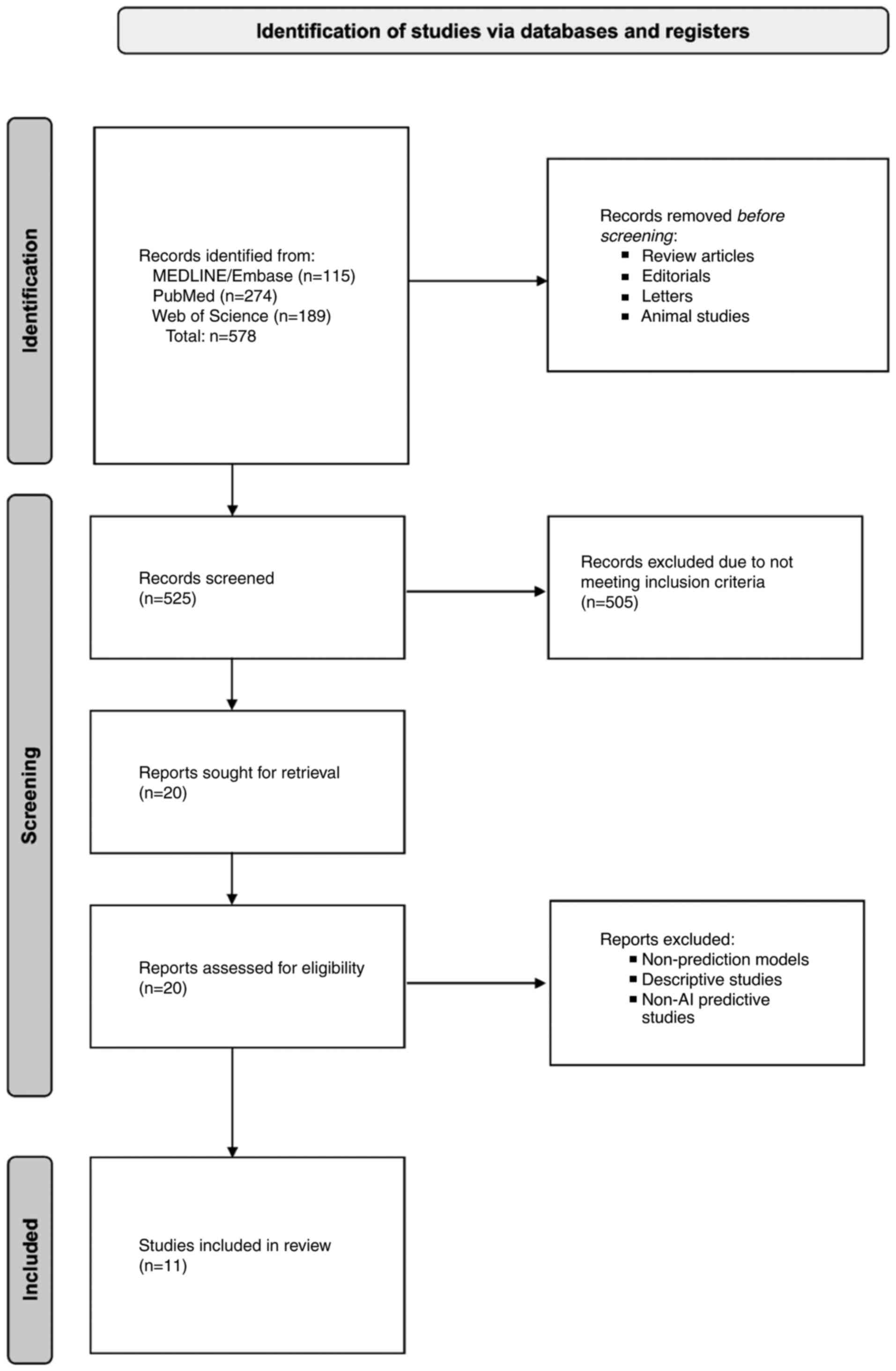

the PRISMA 2020 guidelines, as shown in Fig. 1, including our meta-analysis

studies (15-25).

Our meta-analysis focused on the diagnostic accuracy of AI models,

which does not fall within the scope of PROSPERO registration, as

it primarily registers reviews of interventional studies;

therefore, it was not registered.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies were eligible if they: i) Evaluated AI or

MLMs for CDL diagnosis or prediction, ii) involved human subjects

without age restrictions, and iii) were observational, cohort,

retrospective, or prospective studies. Studies predicting

recurrence or procedural complexity were excluded since they did

not directly evaluate diagnostic performance for initial CDL

detection, which was our primary outcome. Specifically, exclusion

criteria included: i) Models not aimed at diagnostic prediction,

ii) studies not using AI or machine learning (ML) tools, iii)

models focused on predicting procedural complexity or recurrence

prediction after stone removal rather than initial diagnostic

performance for CDL, and iv) studies lacking detailed model

diagnostic accuracy metrics such as sensitivity, specificity,

positive predictive value, negative predictive value, to limit

heterogeneity. All metrics are defined based on the reference

standard, ERCP or intraoperative cholangiography (IOC)

confirmation.

Data extraction

Two reviewers independently extracted data on study

design, model type, comparator (e.g., ASGE guidelines), cohorts,

and performance metrics. Extracted values included sensitivity,

specificity, PPV, LR+, true/false positives and negatives, and

accuracy. LR+ and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated

from raw data where needed. Validation cohort data were prioritized

over training data. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus. Only

clearly reported data was included. Each study was assessed for

data originality to avoid duplication.

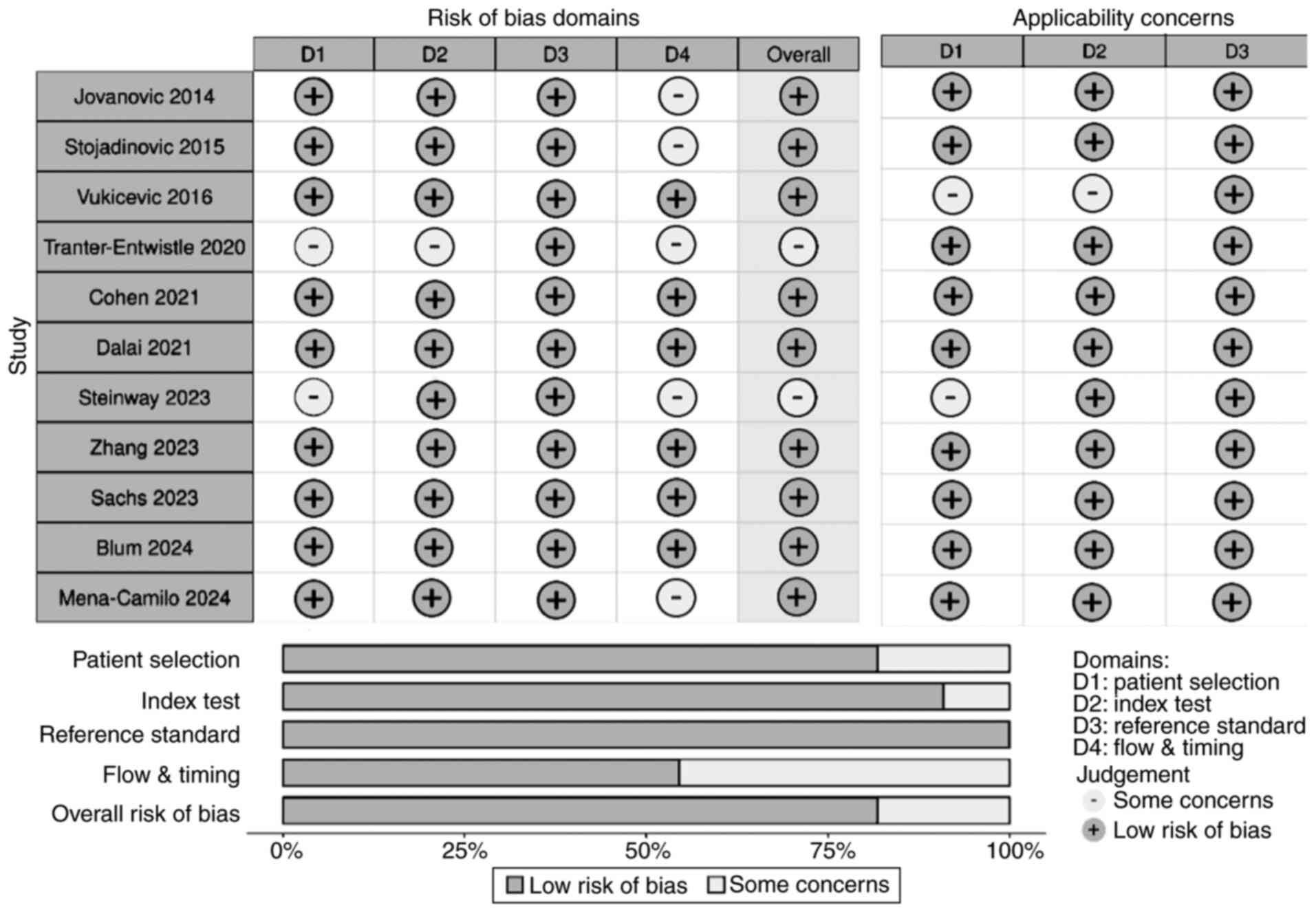

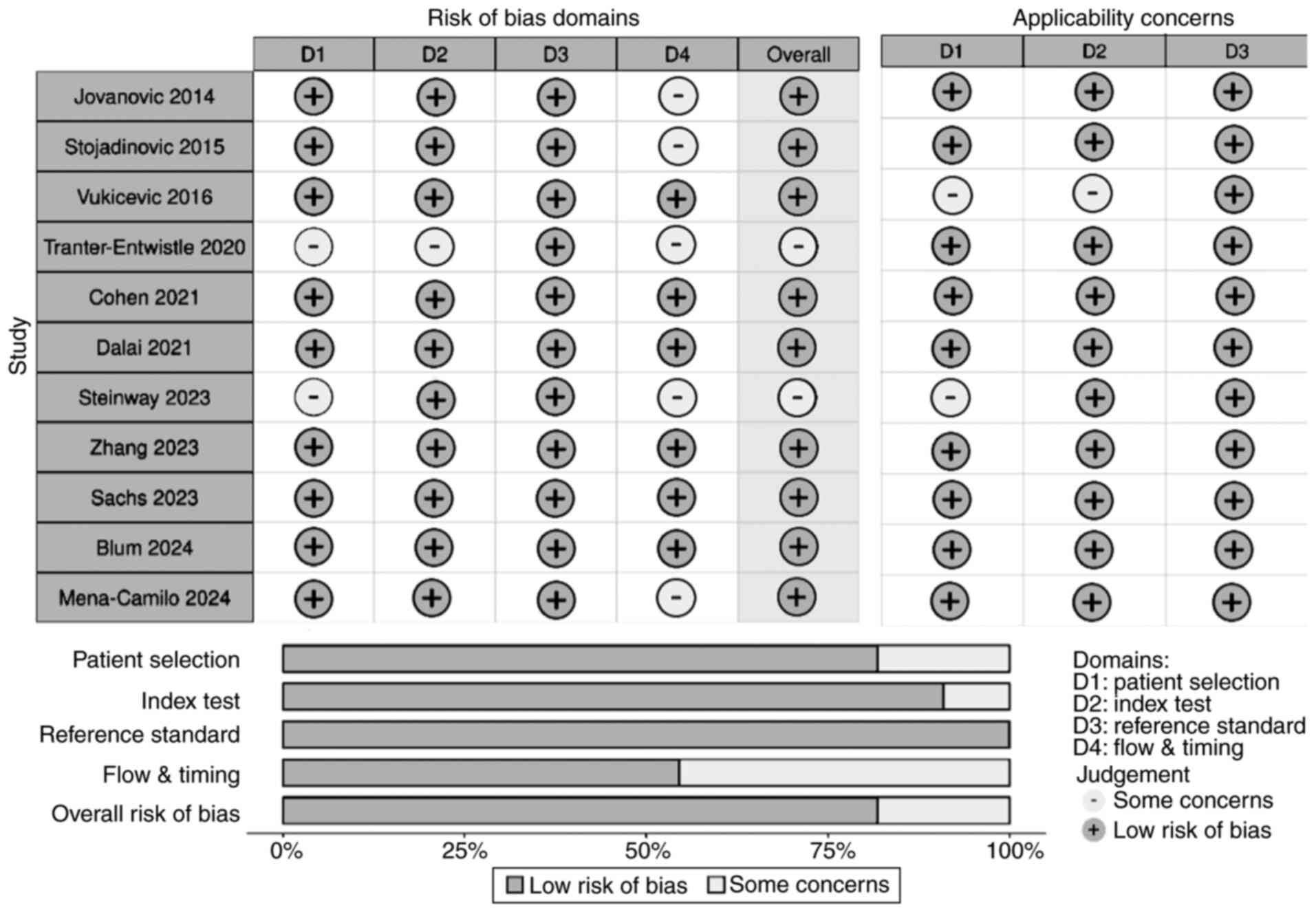

Study quality assessment

Reviewers independently assessed the risk of bias

and applicability concerns using the Quality Assessment of

Diagnostic Accuracy Studies 2 (QUADAS-2) tool, designed for

diagnostic accuracy studies. This tool evaluates four bias domains

(patient selection, index test, reference standard, and

flow/timing) and three applicability domains. All studies were

included regardless of bias ratings, though heterogeneity due to

bias and applicability concerns was acknowledged and considered in

data synthesis and interpretation.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using R

Studio (Version 2020). A bivariate diagnostic random-effects

meta-analysis was conducted, with variance components estimated

using the restricted maximum likelihood (REML) method to minimize

bias. Python and the Clopper-Pearson (exact binomial) method were

used to calculate 95% CI for sensitivity when raw data were

available. Heterogeneity was assessed by calculating the

I2 and τ² statistics within the bivariate

random-effects framework, following the Zhou and Dendukuri approach

for diagnostic test accuracy (DTA) meta-analysis (26). We also visually inspected forest

plots and summary receiver operating characteristic (SROC) curves

to detect threshold effects or outliers. Because moderate

heterogeneity was present in several outcomes, we used a

random-effects model for all pooled estimates and interpreted

summary estimates with caution, emphasizing the direction rather

than the absolute magnitude of effect. SROC curves and

corresponding area under the curve (AUC) values were generated to

evaluate pooled AI model performance and to compare against 2019

ASGE guidelines. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference. Using RStudio, pooled

sensitivity, specificity plots, likelihood ratio positive (LR+) and

Deeks' asymmetry test funnel plots for publication bias were also

created.

Results

Study characteristics

Our systematic search across four databases yielded

578 articles. After screening titles, abstracts, and full texts

using predefined criteria, 20 studies were assessed for

eligibility, and 11 studies were included in the final

meta-analysis (Fig. 1). We

excluded Huerta-Reyna et al for using AI-assisted tools

outside the scope of our review (27) and Shi et al focusing on

recurrence prediction post-ERCP (28). Studies by Huang et al and

Wang et al which assessed the complexity of stone extraction

rather than CDL prediction, were also excluded (29,30).

Li et al's study focused on visualization enhancement of

biliary pathology, rather than stone prediction, which was

similarly omitted (31). Akabane

et al's large multi-center study was excluded due to missing

sensitivity, specificity, and other key diagnostic metrics

(32). Additionally, studies

applying AI solely to imaging without biochemical or clinical data

were excluded (31,33,34).

The 11 included studies encompassed over 7,000

patients evaluated with MLMs. Most studies benchmarked MLM

performance against the ASGE guidelines (2010 or 2019 versions)

(7,35), while several also compared their

models to logistic regression, support vector machines (SVMs), and

k-nearest neighbors (KNN) algorithms, enhancing data robustness.

Table I summarizes AI models,

comparators, patient numbers, sensitivity, specificity, mean age,

sex ratio, PPV, NPV, TP, TN, FN, accuracy, AUC, number of input

variables, and CBD diameter cut-off values. Input variables varied,

incorporating laboratory markers (total bilirubin (TB), alanine

aminotransferase (AST), alanine transaminase (ALT), imaging

features (CBD dilation, ductal stones), and clinical

characteristics. Seven studies compared their models against ASGE

criteria and additional classifiers such as logistic regression,

CART, and KNN.

| Table IDetailed data characteristics of each

study, including sensitivity, specificity, AI model type,

comparator group and total number of patients. |

Table I

Detailed data characteristics of each

study, including sensitivity, specificity, AI model type,

comparator group and total number of patients.

| First author,

year | AI model | Comparator | Patient number | Sens., % | Spec., % | 95% CI Sens. | Accuracy | AUC | Variables | CBD cutoff | F/M | Mean age,

years | PPV | NPV | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Blum, 2024 | RF, LR, KNN,

XGBoost | ASGE | 222 | 86 | 72 | 0.794; 0.923 | 0.79 | 0.83 | 9 | 6 | 1.13:1 | 63.6 | 77 | 82 | (15) |

| Cohen, 2021 | MLR, ΚΝΝ | ASGE | 316 | 40.8 | 90.3 | 0.339; 0.477 | 0.72 | 0.738 | 4 | NM | 1.08:1 | 13.8 | 71.4 | 72.1 | (16) |

| Dalai, 2021 | RF | ASGE | 52 | 61.4 | 100 | 0.789; 0.896 | 0.77 | 0.791 | 9 | 9 | 1.22:1 | 46 | 100 | 32 | (17) |

| Jovanovic,

2014 | ANN | LR | 291 | 92.74 | 68.42 | 0.753; 0.847 | 0.92 | 0.844 | 10 | 7 | 1.49:1 | 63 | 92.34 | 69.64 | (18) |

| Mena-Camilo,

2024 | CNN | LR, LDA, ASGE | 292 | 96.77 | 92.86 | 0.946; 0.990 | 0.93 | 0.927 | 12 | NM | 1.94:1 | 46 | 92.86 | 72.35 | (19) |

| Floan Sachs,

2023 | Extra-Trees ML | Pediatric DUCT

Score | 1,597 | 91.3 | 93.4 | 0.881; 0.945 | 0.72 | 0.935 | 9 | NM | 2.86:1 | 13.9 | 75 | 98 | (20) |

| Steinway, 2023 | GBM | ASGE, ESGE | 1,378 | 70.3 | 72.3 | 0.673; 0.731 | 0.72 | 0.79 | 8 | 6 | 1.58:1 | 43 | 78.1 | 63.4 | (21) |

| Stojadinovic,

2015 | CART | LR | 157 | 80.9 | 94.7 | 0.581; 0.946 | 0.93 | 0.939 | 3 | 4 | 1.44:1 | 57 | 70.8 | 96.3 | (22) |

| Tranter-Entwistle,

2020 | GBM | No comparison | 1,315 | 37 | 96 | 0.458; 0.597 | 0.85 | 0.840 | 9 | NM | 1.33:1 | 70 | 67 | 87 | (23) |

| Vukicevic,

2016 | ANN | LR, DT, NB, SVM,

KNN | 303 | 88.2 | 95.8 | 0.844; 0.920 | 0.92 | 0.934 | 8 | 7 | 2.12:1 | 57 | 78.9 | 97.8 | (24) |

| Zhang, 2023 | Model Arts AI | ASGE, ESGE | 1,199 | 97 | 97 | 0.957; 0.983 | 0.97 | ~0.97 | 11 | 6 | 1.07:1 | 66 | 97.1 | 50 | (25) |

Sensitivity and specificity of AI

models

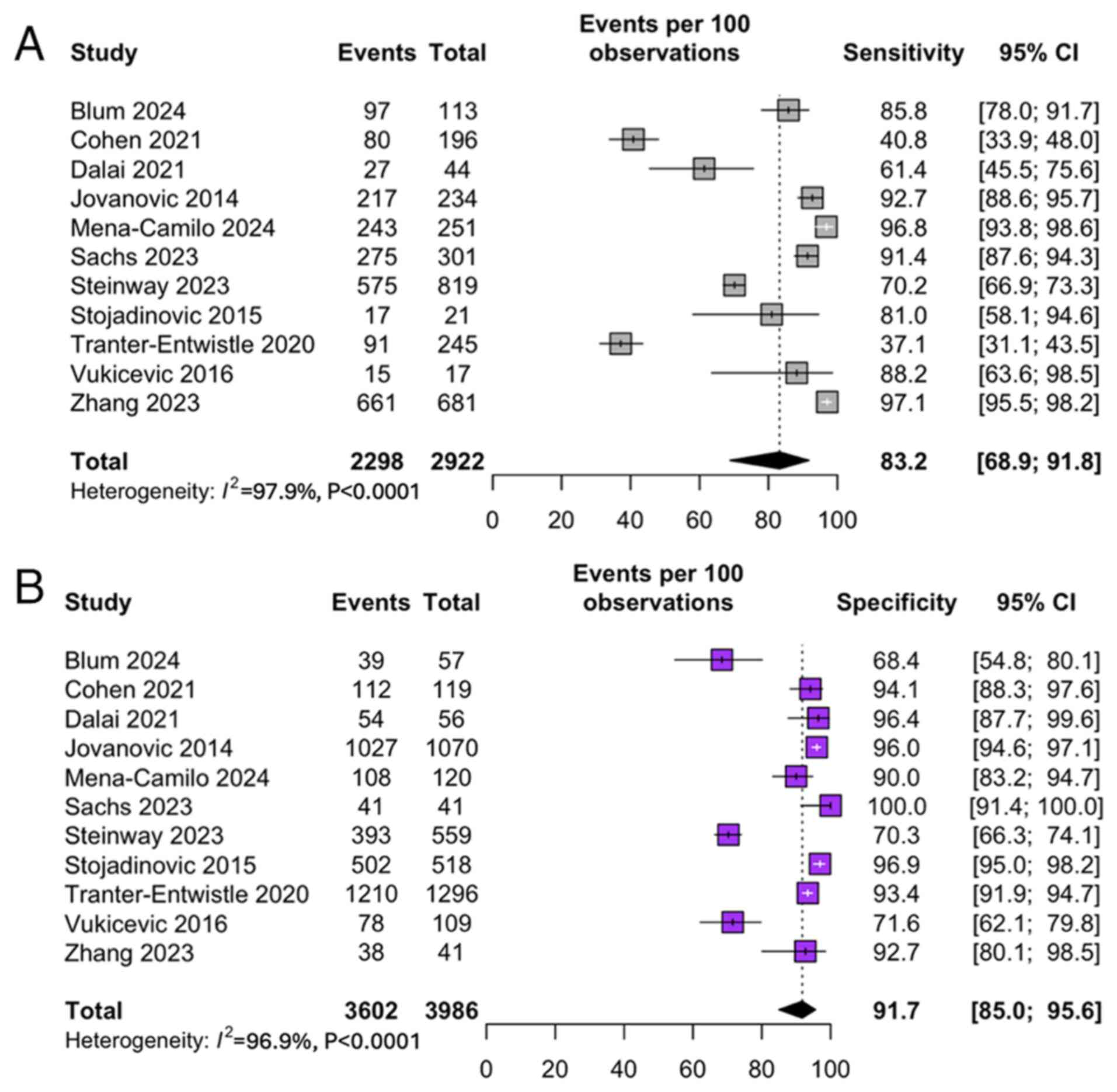

The pooled sensitivity and specificity for MLM

predicting CDL were 83.2% [95% CI: 68.9; 91.8] (Fig. 2A) and 91.1% [95% CI: 84.7; 95.0]

(Fig. 2B), respectively. These

values, calculated using a bivariate random-effects model, reflect

consistently high diagnostic performance across diverse study

settings. Individual studies, such as Blum et al and Floan

Sachs et al reported sensitivities >90% (15,20).

In contrast, others, like Cohen et al exhibited trade-offs

between sensitivity and specificity depending on the model

threshold chosen (16).

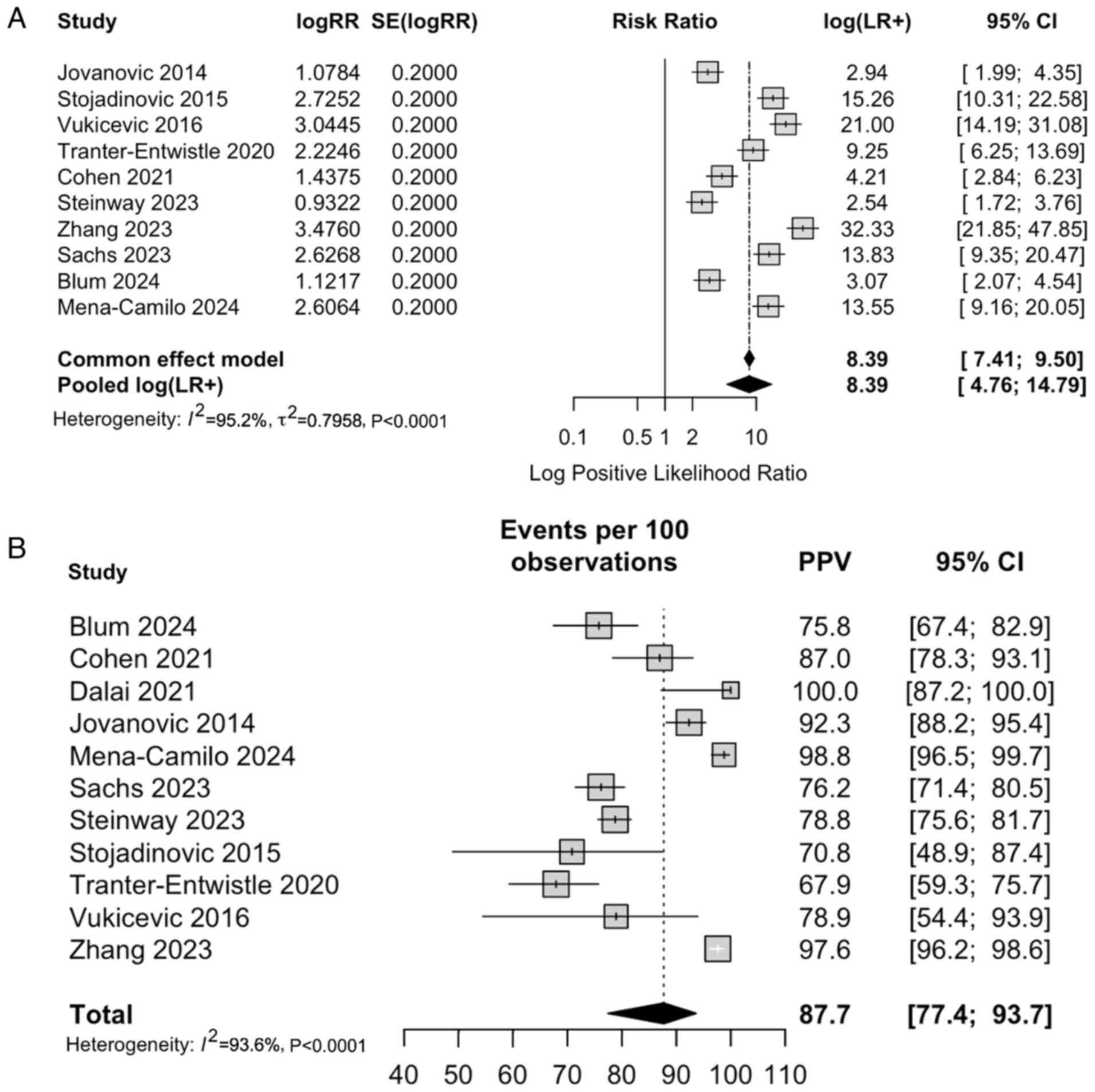

Positive predictive value and

likelihood ratio

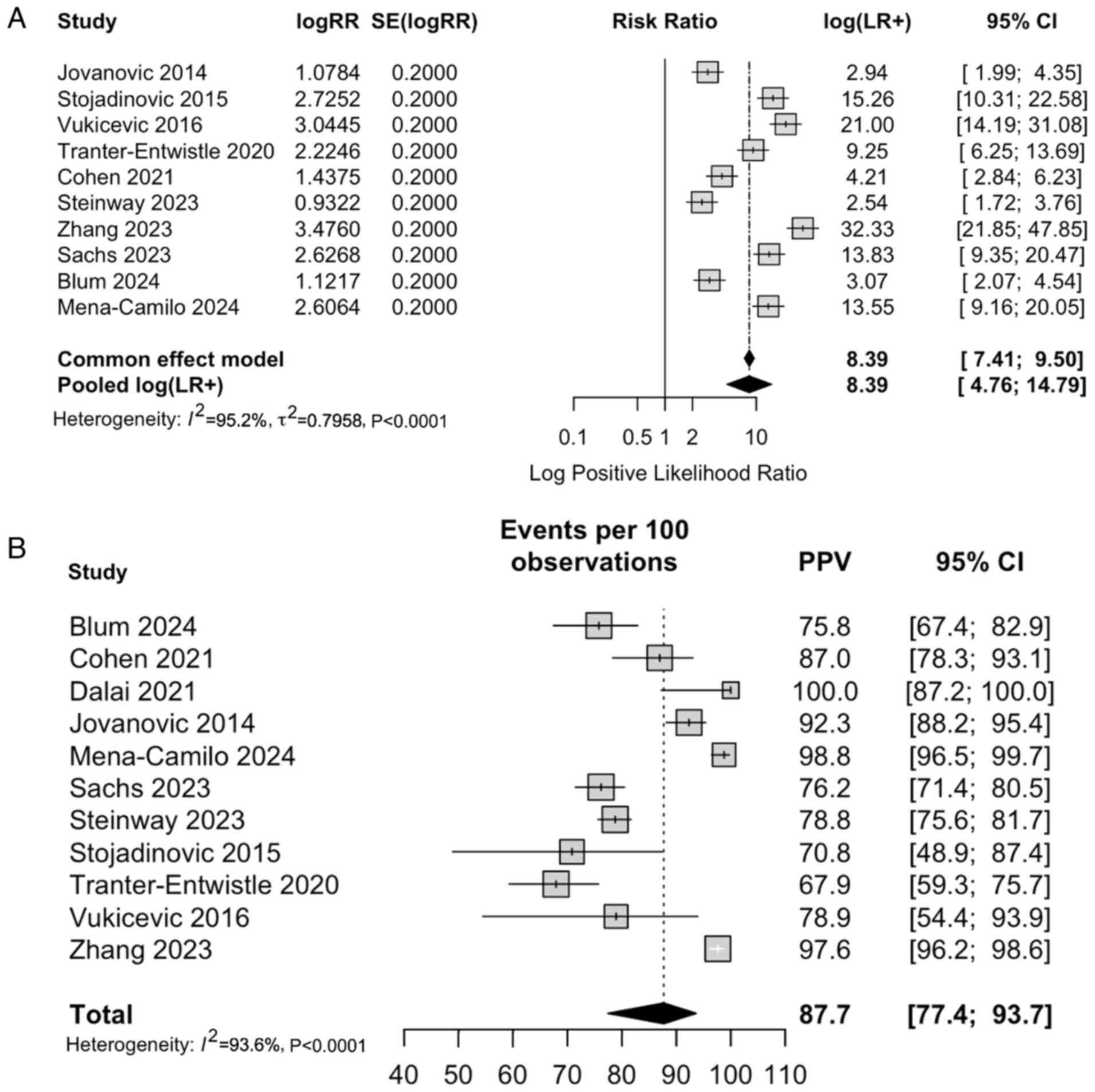

The pooled positive likelihood ratio (LR+) from the

common-effect model was 8.39 [95% CI: 4.4; 9.5], indicating that

patients testing positive via an MLM algorithm were approximately

seven times more likely to truly have CDL compared to those who

tested negative (Fig. 3A). The

pooled PPV was 87.7 [95% CI: 77.4; 93.7] based on the calculated

PPV from the included studies (Fig.

3B).

| Figure 3(A) Forest plot of LR+ for AI-based

diagnostic models across the 11 included studies (>7,000

patients), illustrating their ability to correctly ‘rule in’ CDL

when the test result is positive. The pooled LR⁺ from the

common-effect model was 8.39 (95% CI: 7.41-9.50), indicating that

AI-assisted tools substantially increase the post-test probability

of disease compared to pre-test estimates. (B) Forest plot

summarizing PPV estimates from studies evaluating AI-based

diagnostic tools for CDL. Pooled PPV was 87.7% (95% CI: 77.4-93.7),

demonstrating strong predictive performance in clinical practice.

Cis for individual studies highlight variability related to patient

selection, disease prevalence, and input variable differences, but

overall estimates indicate robust diagnostic accuracy across

diverse populations and model architectures. CDL,

choledocholithiasis; CI, confidence interval; LR+, positive

likelihood ratio; PPV, positive predictive value. AI, artificial

intelligence. |

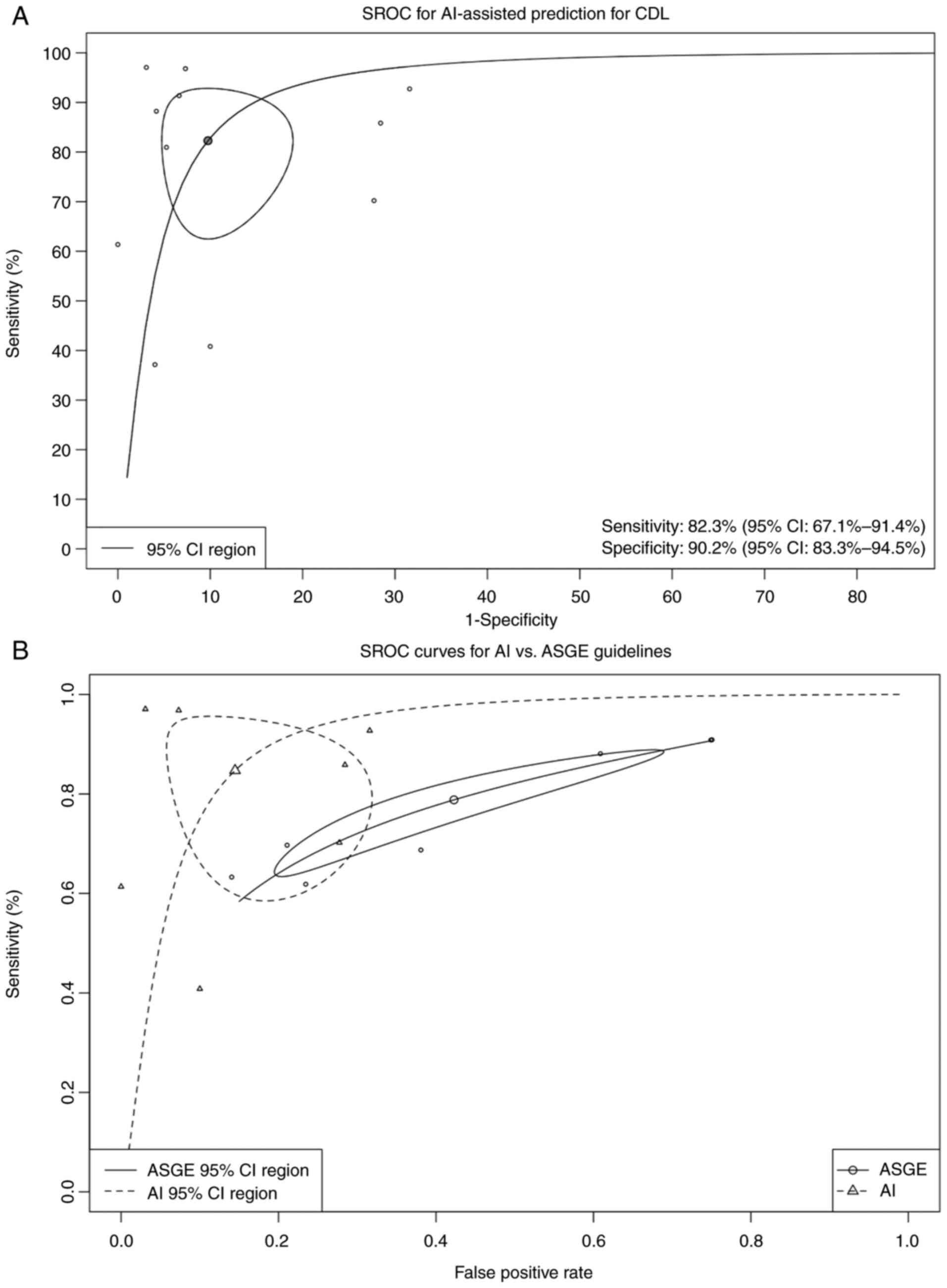

SROC analysis

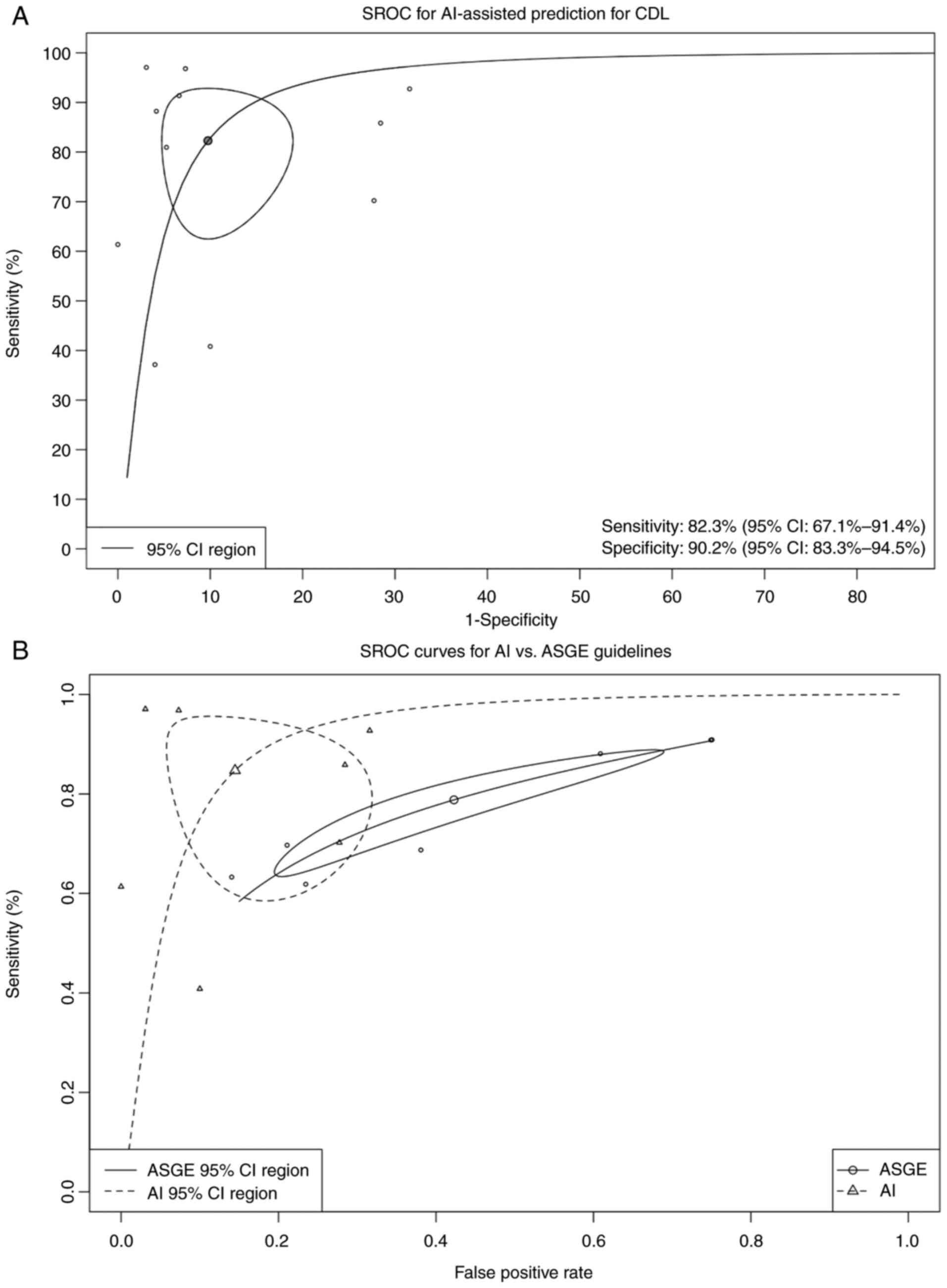

SROC curves and AUC values were generated to assess

pooled diagnostic performance across MLMs (Fig. 4A). The primary SROC curve indicated

excellent discriminative ability, confirming AI models' robust and

consistent performance across diverse study populations and

clinical settings.

| Figure 4(A) Bivariate random-effects SROC

curve of AI-assisted diagnostic tools derived from 11 studies

involving over 7,000 individuals. The pooled AUC was 0.94 (95% CI:

0.83-0.98), indicating high discriminative performance across

diverse clinical populations. Threshold effect testing showed no

significant heterogeneity (P>0.05). Using Deeks' test, funnel

plot analysis for publication bias did not demonstrate significant

asymmetry (t=1.84, P=0.13). (B) Comparative SROC curves of

AI-assisted models vs. the 2019 ASGE high-risk criteria. AI models

demonstrated significantly higher pooled diagnostic accuracy with

an AUC of 0.91 (97.5% CI: 0.76-0.96) compared to ASGE criteria (AUC

0.76; 97.5% CI: 0.72-0.80). Mixed-effects meta-regression

(generalized linear mixed model, likelihood ratio test P=0.019)

confirmed the superior performance of AI models. Sensitivity and

specificity estimates for AI models were 86.1% (95% CI: 68.5-94.7)

and 93.3% (95% CI: 71.4-98.7), respectively, compared to ASGE

guideline performance of 78.4% (95% CI: 67.5-86.4) and 57.5% (95%

CI: 37.3-75.6). CDL, choledocholithiasis; SROC, summary receiver

operating characteristic; AI, artificial intelligence; AUC, area

under the curve; CI, confidence interval; ASGE, American Society

for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. |

Subgroup analysis: AI-models vs. ASGE

guidelines

Seven studies directly compared their MLM to the

2019 ASGE risk stratification criteria. Pooled sensitivity and

specificity values were used to generate SROC curves for both

models. As shown in Fig. 4B, MLMs

consistently achieved higher AUC values and diagnostic accuracy

than ASGE high-risk criteria. This suggests that AI may enhance

precision and reduce reliance on subjective guideline

interpretation in pre-ERCP decision-making.

In bivariate random-effects meta-analysis, MLMs

achieved an AUC of 0.915 (95% CI: 0.763-0.961) compared to 0.766

(95% CI: 0.7;-0.7) for ASGE guidelines. The absolute difference in

AUC (ΔAUC=0.148) reflects a clinically meaningful improvement

favoring AI tools. Although the 95% CI for this difference (-0.002

to 0.205) includes zero, the P-value (0.053) indicates a trend

toward statistical significance. The pooled sensitivity for AI

models was 82.3%, with a false positive rate of 9.8%. Heterogeneity

across studies ranged from 52.4% (Zhou and Dendukuri method) to

97.8% (Holling unadjusted).

Quality assessment for bias

QUADAS-2 tool evaluation identified ‘some concerns’

in several studies, mainly in patient selection (convenience

sampling, exclusion of cholangitis, etc.) and flow/timing (delayed

or unclear index/reference timing) domains (Fig. 5). Specifically, Tranter-Entwistle

et al faced issues with missing clinical data, 36%

misclassification, and manual diagnosis reassignment (23). Temporal alignment of index and

reference tests was inconsistently reported. Steinway et al

lacked clarity regarding blinding details and applied a

retrospective cohort design, excluding cholangitis, potentially

limiting generalizability (21).

Mena-Camilo et al despite ERCP-confirmed diagnoses,

demonstrated significant class imbalance (86% positive) and heavy

reliance on imputed clinical data, raising data integrity concerns

(19). QUADAS-2 revealed moderate

risk biases likely inflated accuracy estimates in some models by

limiting negative cases or excluding diagnostically challenging

scenarios. Therefore, while AI models demonstrated strong pooled

performance, conclusions should be interpreted with caution given

these study-level limitations.

| Figure 5The Quality Assessment of Diagnostic

Accuracy Studies 2 tool was used to evaluate risk of bias and

applicability concerns for the 11 included studies (>7,000

patients). The round-shaped plot (top) summarizes the judgment of

each study across four bias domains, patient selection, index test,

reference standard, and flow/timing, and three applicability

domains, using grey (low risk), and white (some concerns). No areas

of high risk were noted. The summary plot (bottom) depicts the

overall proportion of studies rated at low risk or with some

concerns within each domain. Overall, most studies demonstrated low

risk in the index test and reference standard domains, while

patient selection and flow/timing presented the most frequent

concerns, primarily due to retrospective designs, incomplete

clinical data, or unclear temporal alignment of index and reference

tests. Applicability concerns were minimal for most studies,

reflecting consistent patient populations and appropriate test

applications. These results indicate an overall moderate to high

quality of included studies, supporting the robustness of the

meta-analysis findings. |

Discussion

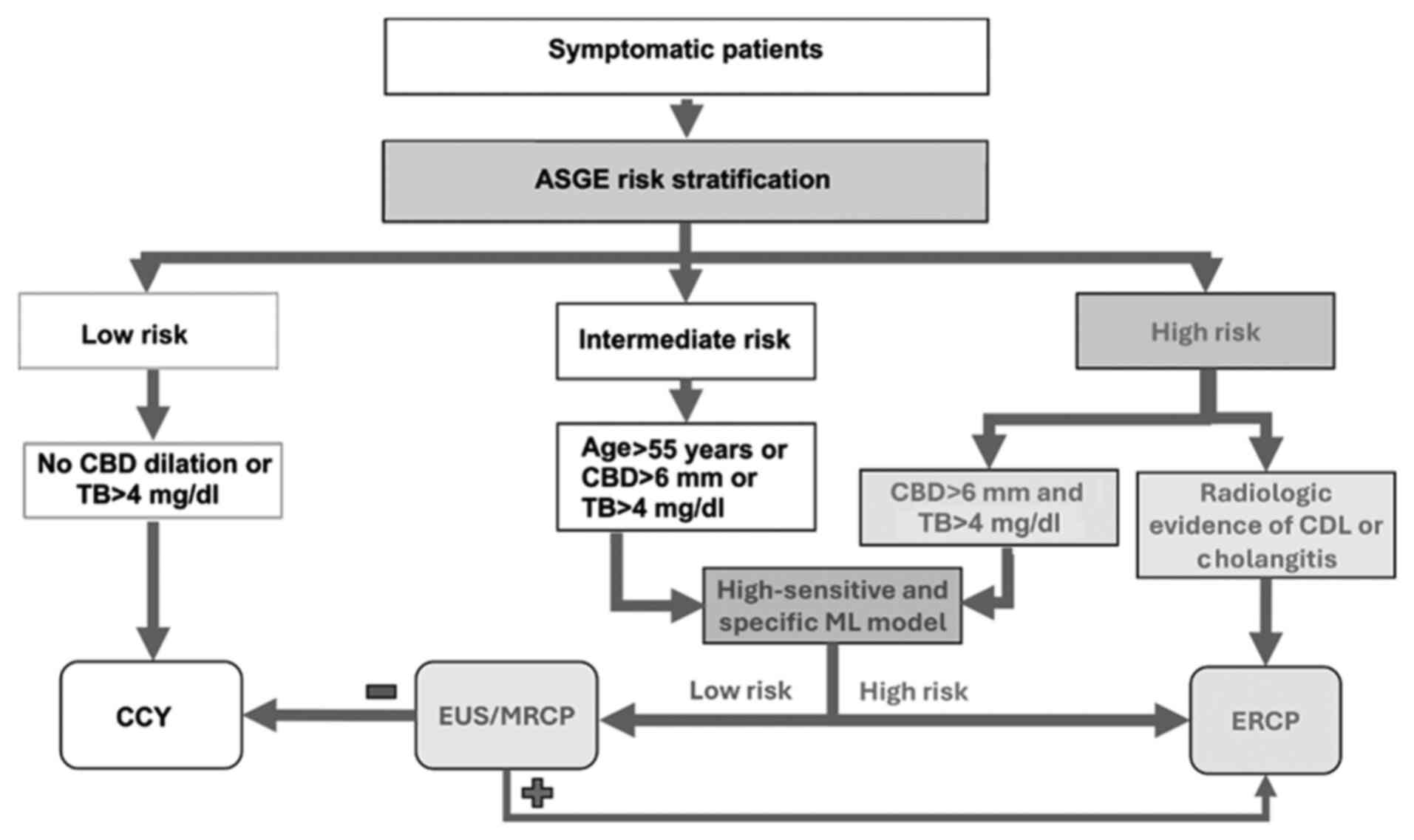

Accurate stratification of patients with suspected

CDL remains clinically challenging. To improve specificity and

reduce unnecessary ERCPs, the 2019 ASGE guidelines revised

high-risk criteria to include only patients with both TB >4

mg/dl and CBD dilation on imaging (Fig. 6) (6). This change, supported by prior

studies showing improved specificity with these combined features

(36,37), raised specificity from 55% under

the 2010 criteria to approximately 80% (38). The 2019 update also incorporated

computed tomography (CT) alongside ultrasonography (USG) for risk

stratification (6). Per the

current guidelines, in the absence of definitive radiologic

evidence of CDL, ERCP is recommended for patients with a suggestive

clinical presentation, elevated liver enzymes, CBD dilation >6

mm, TB >4 mg/dl, or signs of cholangitis (Fig. 6). Those not meeting high-risk

criteria are advised to undergo magnetic resonance

cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) or EUS (Fig. 6) (6). While MRCP is a sensitive and specific

tool (39), its overuse may

prolong hospital stays and increase costs (40). Despite refinements, current

guidelines lack tools for quantitative CDL risk estimation. Our

meta-analysis is the first comprehensive synthesis of AI-assisted

prediction models for CDL, highlighting their potential for

non-invasive risk stratification and optimized ERCP selection

(Fig. 6).

The reviewed studies employed diverse MLMs,

including traditional and DL approaches like ANNs, CNNs, and GBMs,

and supervised learning algorithms such as classification and

regression trees (CART), logistic regression, KNN, Naïve Bayes

(NB), and Scikit-learn frameworks Several models demonstrated

superior performance: Stojadinovic et al found that CART

outperformed logistic (22);

Tranter-Entwistle et al reported that GBM outperformed

random forest and KNN (23); Dalai

et al tested GLM, SVM, and random forest, with the latter

performing best and included in our meta-analysis (17). Cohen et al utilized a

KNN-based model (16), while Zhang

et al developed the ModelArts ExeML tool (Huawei),

outperforming logistic regression, LDA, QDA, NB, KNN, and Ranger

(25). Floan Sachs et al

applied Extra-Trees to a 9-feature pediatric model, outperforming

the 3-feature Pediatric DUCT score (20). Blum et al compared logistic

regression, XGBoost, random forest, and KNN, with random forest

performing best in adults with suspected CDL (15).

ANNs were among the earliest tools. Jovanovic et

al introduced an ANN-based model (18), while Vukicevic et al

enhanced it by automating configuration using genetic algorithms,

outperforming logistic regression, decision trees, NB, SVMs, and

KNN (24). Mena-Camilo et

al applied a CNN-based model that exceeded logistic regression

and LDA in sensitivity, supporting DL's role in non-invasive CDL

diagnosis (19).

Our meta-analysis of 7,000+ subjects across 11

studies showed strong predictive performance of AI-assisted models,

with a pooled sensitivity of 83.2%, specificity of 91.1% and a PPV

of 87.7% [77.4; 93.7]. Despite heterogeneity in models, patient

populations, and predictive variables, consistently high accuracy

supports AI as a non-invasive diagnostic tool and underscores its

adaptability, especially where guidelines fall short. A key source

of heterogeneity is in training/validation cohorts, impacting

generalizability. Jovanovic et al excluded patients with

prior CCY, cholangitis, and primary sclerosing cholangitis,

achieving high AUC (0.884) and sensitivity (92.7%) but lower

specificity (68.7%) due to few ERCP-negative cases and low NPV

(18).

Other studies also assessed high-suspicion cohorts

undergoing ERCP or IOC, excluding cholangitis cases (15,21).

Dalai et al focused on Hispanic/Latino patients with prior

CCY (17). Again, low

ERCP-negative rates skewed the sample distribution. Blum et

al applying similar criteria, confirmed stones in only 50% of

cases (15). Mena-Camilo et

al trained a CNN regardless of CCY status (19); Zhang et al used MRCP or IOC

for diagnosis, excluding cholangitis (25). Tranter-Entwistle et al found

CDL in 19% of acute biliary cases, with their GBM model showing low

sensitivity (37%) and high specificity (96%) due to missing data

imputation (23). In elective

surgical populations, Stojadinovic et al found 37% CDL

prevalence; their CART model exceeded logistic regression in

sensitivity (90.9% vs. 57.2%) but not specificity (92.3% vs. 94.7%)

(22). Similarly, Vukicevic et

al's ANN achieved 88.2% sensitivity and 95.8% specificity among

CCY patients with IOC (24).

Although CDL is typically adult-onset, pediatric

cases are rising with obesity (41-43).

Cohen et al evaluated suspected pediatric CDL using

IOC/ERCP, prioritizing PPV by setting 90% specificity, which

yielded only 40.8% sensitivity and 71.5% accuracy, marking it an

outlier (16). Floan Sachs et

al used pediatric elective CCY cases, with CDL confirmed via

MRCP, ERCP, and/or IOC. Their 9-feature model outperformed the

3-feature Pediatric DUCT score (AUC 0.957 vs. 0.935; sensitivity

91.3% vs. 78.3%), while maintaining specificity (20), estimating only 8.7% of cases

missed, compared to 21.7% with the 3-feature model. These results

support ML's role in optimizing ERCP in children, with performance

thresholds that are unable to meet institutional needs.

Input variables ranged from 3 to 53 (Table I), typically combining biochemical

laboratory data and imaging. USG and CT were common, while MRCP was

underused. Dalai et al showed models incorporating CT/MRCP

had higher AUC than USG alone (17). Cohen et al excluded CBD

stone presence on USG due to its high predictive value; univariate

analysis identified (AST), CBD diameter, and ductal stone presence

on USG as key predictors (16).

Common biochemical values in all studies included TB, AST, ALT, and

alkaline phosphatase (ALP). Few used follow-up biochemical values.

Steinway et al found no benefit from serial labs (21). Stojadinovic et al emphasized

cystic duct diameter (>4 mm), elevated ALP, and multiple small

gallstones (‘dangerous’ stones) as key predictors, though their

elective CCY cohort may not reflect acute cases (22). Jovanovic et al (18) found lipase and CBD diameter to be

influential, with lipase and AST negatively, and CBD diameter

positively associated with CDL, supporting the theory that

pancreatitis may follow stone passage rather than concurrent CDL

(6,18,22).

Seven studies directly compared MLMs to the 2019

ASGE guidelines; others used published ASGE performance data for

benchmarking. MLMs consistently outperformed current guidelines,

particularly in high-suspicion cases (Table I) (18,19,21).

Most models achieved high sensitivity, except Tranter-Entwistle

et al (23) and Cohen et

al (16), which prioritized

specificity above 90%, reducing sensitivity. Most models reported

>90% accuracy, though accuracy can be prevalence-dependent.

Large sample sizes strengthen these conclusions. Integrating MLMs

may enhance individualized CDL risk stratification.

Steinway et al's GBM achieved sensitivity and

specificity above 70%, outperforming ASGE (61.9/62.8%) and European

Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) (46.9/86.3%), avoiding

22% of unnecessary ERCPs and identifying 48% of true positives

missed by ESGE guidelines (21).

Dalai et al's best-performing model (77.3% sensitivity, 75%

specificity) outperformed the ASGE's high-likelihood group, which

had higher sensitivity (90.3%) but lower specificity (25%)

(17). Threshold tuning raised

sensitivity to 97.7%, illustrating MLM flexibility. Blum et

al found Random Forest best among four classifiers (AUC 0.83,

sensitivity 94%), exceeding ASGE (15). Zhang et al reported ASGE's

high sensitivity (98.5%) but poor specificity, while their

ModelArts ExML tool achieved AUCs of 0.77-0.81(25). Jovanovic et al's ANN model

(AUC 0.884) surpassed logistic regression (AUC 0.752), despite

excluding several ASGE criteria (18). Cohen et al's model

prioritized specificity in pediatrics, achieving 40.8% sensitivity

but outperforming ASGE in specificity (16).

This meta-analysis showed higher accuracy for MLMs

(AUC 0.91) vs. ASGE 2019 guidelines (AUC 0.72). Unlike ASGE's fixed

risk categories, MLMs may provide individualized risk

stratification. While ASGE guidelines remain a valuable risk

stratification tool, their broad criteria often underperform in

real-world populations (6). AI

models offer personalization, especially in low-resource settings

or special populations like pediatrics (16,20).

High-specificity models reduce unnecessary ERCPs; high-sensitivity

models expedite referrals. From a therapeutic standpoint, these

tools may refine patient selection for ERCP, particularly in

intermediate/high-risk patients lacking definitive findings. In

such cases, MLMs could guide decisions between MRCP and ERCP. The

findings also open avenues for developing real-time, bedside

decision-support tools trained on multicenter data and embedded

within electronic medical records. Though AI tool thresholds may

vary, high sensitivity supports timely referral in community

hospitals, while high specificity aids triage in tertiary centers.

ASGE guidelines recommend direct CCY for low-risk patients, yet

some harbor occult stones (6).

While the benefit of pre-CCY ERCP is debated, AI may identify

low-risk patients needing further evaluation (6,44-46).

These findings are consistent with broader AI applications in

gastroenterology, including colorectal polyp and neoplasia

detection or classification (11,12,47,48),

highlighting the potential of AI-based tools to improve diagnostic

accuracy and efficiency. However, extrapolation across clinical

settings remains challenging, underscoring the need for external

validation and standardized performance reporting. Integrating AI

into clinical workflows may reduce unnecessary testing, optimize

resources, and improve outcomes (49).

This study supports the diagnostic potential of AI

tools for CDL, but several limitations exist. We identified 11

distinct AI models using varied input data: labs, imaging, clinical

features, introducing heterogeneity that hinders direct comparisons

and pooled estimates. A key limitation is the lack of prospective

validation; most studies were retrospective, single-centered,

limiting generalizability. Homogeneous populations and limited

external validation further constrain applicability. Comparisons

were inconsistent, using differing ASGE guidelines, impairing

uniform benchmarking. Future studies should prioritize standardized

comparisons using current ASGE criteria and diverse cohorts. Some

studies lacked key statistics (e.g., CI, PPV, NPV), and unclear

training-validation cohort separation may have skewed performance.

In several cases, unclear differentiation between training and

validation cohorts may have distorted performance outcomes. These

issues underscore the need for prospective validation and

standardized reporting to enable clinical adoption.

In conclusion, this study highlights that ML tools

demonstrate promising diagnostic potential for CDL detection and

may enhance current or future guideline-based risk stratification.

While pooled sensitivity and specificity were high, heterogeneity,

reliance on retrospective data, and a somewhat limited prospective

validation constrain definitive conclusions. AI-based tools may

complement existing guidelines via a non-invasive accurate

alternative in refining patient selection for ERCP, enhancing both

the safety and efficiency of care, especially in acute and

resource-limited settings. Future work should prioritize validation

in prospective multicenter studies, ensure model generalizability,

and support integration into clinical workflows before clinical

implementation.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

PGD, SGD and AB conceived and designed the study.

PGD and SGD performed literature search, data analysis, and

interpretation of data and results. PGD and SGD confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. PGD, SGD and AB prepared the

draft manuscript and critically revised the manuscript. AB

supervised the study. All authors reviewed the results, and read

and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Authors' information

Panagiotis G. Doukas: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8050-963X. Sotirios G.

Doukas: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1840-659X.

References

|

1

|

Tazuma S, Unno M, Igarashi Y, Inui K,

Uchiyama K, Kai M, Tsuyuguchi T, Maguchi H, Mori T, Yamaguchi K, et

al: Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for cholelithiasis

2016. J Gastroenterol. 52:276–300. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Unalp-Arida A and Ruhl CE: Burden of

gallstone disease in the United States population: Prepandemic

rates and trends. World J Gastrointest Surg. 16:1130–1148.

2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Li S, Guizzetti L, Ma C, Shaheen AA, Dixon

E, Ball C, Wani S and Forbes N: Epidemiology and outcomes of

choledocholithiasis and cholangitis in the United States: Trends

and Urban-rural variations. BMC Gastroenterol.

23(254)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Molvar C and Glaenzer B:

Choledocholithiasis: Evaluation, treatment, and outcomes. Semin

Intervent Radiol. 33:268–276. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Morales SJ, Sampath K and Gardner TB: A

review of prevention of Post-ERCP pancreatitis. Gastroenterol

Hepatol (N Y). 14:286–292. 2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

ASGE Standards of Practice Committee.

Buxbaum JL, Abbas Fehmi SM, Sultan S, Fishman DS, Qumseya BJ,

Cortessis VK, Schilperoort H, Kysh L, Matsuoka L, et al: ASGE

guideline on the role of endoscopy in the evaluation and management

of choledocholithiasis. Gastrointest Endosc. 89:1075–1105.e15.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

ASGE Standards of Practice Committee.

Maple JT, Ben-Menachem T, Anderson MA, Appalaneni V, Banerjee S,

Cash BD, Fisher L, Harrison ME, Fanelli RD, et al: The role of

endoscopy in the evaluation of suspected choledocholithiasis.

Gastrointest Endosc. 71:1–9. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Tunruttanakul S, Chareonsil B, Verasmith

K, Patumanond J and Mingmalairak C: Evaluation of the American

society of gastrointestinal endoscopy 2019 and the european society

of gastrointestinal endoscopy guidelines' performances for

choledocholithiasis prediction in clinically suspected patients: A

retrospective cohort study. JGH Open. 6:434–440. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Rajpurkar P, Chen E, Banerjee O and Topol

EJ: AI in health and medicine. Nat Med. 28:31–38. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Kröner PT, Engels MM, Glicksberg BS,

Johnson KW, Mzaik O, van Hooft JE, Wallace MB, El-Serag HB and

Krittanawong C: Artificial intelligence in gastroenterology: A

state-of-the-art review. World J Gastroenterol. 27:6794–824.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Byrne MF, Chapados N, Soudan F, Oertel C,

Linares Pérez M, Kelly R, Iqbal N, Chandelier F and Rex DK:

Real-time differentiation of adenomatous and hyperplastic

diminutive colorectal polyps during analysis of unaltered videos of

standard colonoscopy using a deep learning model. Gut. 68:94–100.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Korbar B, Olofson AM, Miraflor AP, Nicka

CM, Suriawinata MA, Torresani L, Suriawinata AA and Hassanpour S:

Deep learning for classification of colorectal polyps on

Whole-slide images. J Pathol Inform. 8(30)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

An Q, Rahman S, Zhou J and Kang JJ: A

comprehensive review on machine learning in healthcare industry:

Classification, restrictions, opportunities and challenges. Sensors

(Basel). 23(4178)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Trezza A, Visibelli A, Roncaglia B, Spiga

O and Santucci A: Unsupervised learning in precision medicine:

Unlocking personalized healthcare through AI. Appl Sci.

14(9305)2024.

|

|

15

|

Blum J, Hunn S, Smith J, Chan FY and

Turner R: Using artificial intelligence to predict

choledocholithiasis: Can machine learning models abate the use of

MRCP in patients with biliary dysfunction? ANZ J Surg.

94:1260–1265. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Cohen RZ, Tian H, Sauer CG, Willingham FF,

Santore MT, Mei Y and Freeman AJ: Creation of a pediatric

choledocholithiasis prediction model. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr.

73:636–641. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Dalai C, Azizian J, Trieu H, Rajan A, Chen

F, Dong T, Beaven S and Tabibian JH: Machine learning models

compared to existing criteria for noninvasive prediction of

endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography-confirmed

choledocholithiasis. Liver Res. 5:224–231. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Jovanovic P, Salkic NN and Zerem E:

Artificial neural network predicts the need for therapeutic ERCP in

patients with suspected choledocholithiasis. Gastrointest Endosc.

80:260–268. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Mena-Camilo E, Salazar-Colores S,

Aceves-Fernández MA, Lozada-Hernández EE and Ramos-Arreguín JM:

Non-invasive prediction of choledocholithiasis using 1D

convolutional neural networks and clinical data. Diagnostics.

14(1278)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Floan Sachs G, Ourshalimian S, Jensen AR,

Kelley-Quon LI, Padilla BE, Shew SB, Lofberg KM, Smith CA, Roach

JP, Pandya SR, et al: Machine learning to predict pediatric

choledocholithiasis: A western pediatric surgery research

consortium retrospective study. Surgery. 174:934–939.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Steinway SN, Tang B, Telezing J, Ashok A,

Kamal A, Yu CY, Jagtap N, Buxbaum JL, Elmunzer J, Wani SB, et al: A

machine learning-based choledocholithiasis prediction tool to

improve ERCP decision making: A proof-of-concept study. Endoscopy.

56:165–171. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Stojadinovic MM and Pejovic T: Regression

tree for choledocholithiasis prediction. Eur J Gastroenterol

Hepatol. 27:607–613. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Tranter-Entwistle I, Wang H, Daly K,

Maxwell S and Connor S: The challenges of implementing artificial

intelligence into surgical practice. World J Surg. 45:420–428.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Vukicevic AM, Stojadinovic M, Radovic M,

Djordjevic M, Cirkovic BA, Pejovic T, Jovicic G and Filipovic N:

Automated development of artificial neural networks for clinical

purposes: Application for predicting the outcome of

choledocholithiasis surgery. Comput Biol Med. 75:80–89.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Zhang H, Gao J, Sun Z, Zhang Q, Qi B,

Jiang X, Li S and Shang D: Diagnostic accuracy of updated risk

assessment criteria and development of novel computational

prediction models for patients with suspected choledocholithiasis.

Surg Endosc. 37:7348–7357. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Zhou Y and Dendukuri N: Statistics for

quantifying heterogeneity in univariate and bivariate meta-analyses

of binary data: The case of Meta-analyses of diagnostic accuracy.

Stat Med. 33:2701–2717. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Huerta-Reyna R, Guevara-Torres L,

Martínez-Jiménez MA, Armas-Zarate F, Aguilar-García J,

Waldo-Hernández LI and Martínez-Martínez MU: Development and

validation of a predictive model for choledocholithiasis. World J

Surg. 48:1730–1738. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Shi Y, Lin J, Zhu J, Gao J, Liu L, Yin M,

Yu C, Liu X, Wang Y and Xu C: Predicting the recurrence of common

bile duct stones after ERCP treatment with automated machine

learning algorithms. Dig Dis Sci. 68:2866–2877. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Huang L, Lu X, Huang X, Zou X, Wu L, Zhou

Z, Wu D, Tang D, Chen D, Wan X, et al: Intelligent difficulty

scoring and assistance system for endoscopic extraction of common

bile duct stones based on deep learning: Multicenter study.

Endoscopy. 53:491–498. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Wang Z, Yuan H, Lin K, Zhang Y, Xue Y, Liu

P, Chen Z and Wu M: Artificial intelligence-empowered assessment of

bile duct stone removal challenges. Expert Systems Applications.

258(125146)2024.

|

|

31

|

Li D, Du B, Shen Y and Ge L: Artificial

Intelligence-assisted visual sensing technology under duodenoscopy

of gallbladder stones. J Sensors. 2021(5158577)2021.

|

|

32

|

Akabane S, Iwagami M, Bell-Allen N,

Navadgi S, Kawahara T and Bhandari M: Machine learning-based

prediction for incidence of endoscopic retrograde

cholangiopancreatography after emergency laparoscopic

cholecystectomy: A retrospective, multicenter cohort study. Surg

Endosc. 39:1770–1777. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Hou JU, Park SW, Park SM, Park DH, Park CH

and Min S: Efficacy of an artificial neural network algorithm based

on Thick-slab magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography images

for the automated diagnosis of common bile duct stones. J

Gastroenterol Hepatol. 36:3532–3540. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Sun K, Li M, Shi Y, He H, Li Y, Sun L,

Wang H, Jin C, Chen M and Li L: Convolutional neural network for

identifying common bile duct stones based on magnetic resonance

cholangiopancreatography. Clin Radiol. 79:553–558. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Singhvi G, Ampara R, Baum J and Gumaste V:

ASGE guidelines result in Cost-saving in the management of

choledocholithiasis. Ann Gastroenterol. 29:85–90. 2016.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Kang J, Paik KH, Lee JC, Kim HW, Lee J,

Hwang JH and Kim J: The efficacy of clinical predictors for

patients with intermediate risk of choledocholithiasis. Digestion.

94:100–105. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

He H, Tan C, Wu J, Dai N, Hu W, Zhang Y,

Laine L, Scheiman J and Kim JJ: Accuracy of ASGE high-risk criteria

in evaluation of patients with suspected common bile duct stones.

Gastrointest Endosc. 86:525–532. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Jacob JS, Lee ME, Chew EY, Thrift AP and

Sealock RJ: Evaluating the revised american society for

gastrointestinal endoscopy guidelines for common bile duct stone

diagnosis. Clin Endosc. 54:269–274. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Lee H, Song T, Park DH, Lee SS, Seo DW,

Lee SK, Kim MH, Jun JH, Moon JE and Song YH: Diagnostic performance

of the current Risk-stratified approach with computed tomography

for suspected choledocholithiasis and its options when negative

finding. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 18:366–372.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Anand G, Yeh HC, Khashab M, Kim KJ, Lennon

AM, Shin EJ, Canto M, Okolo PI, Kalloo AN and Singh VK: Mo1582

Patterns of MRCP Utilization prior to ERCP among patients at high

risk for choledocholithiasis. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy.

73:AB393–AB394. 2011.

|

|

41

|

Tuna Kirsaclioglu C, Çuhacı Çakır B,

Bayram G, Akbıyık F, Işık P and Tunç B: Risk factors, complications

and outcome of cholelithiasis in children: A retrospective,

single-centre review. J Paediatr Child Health. 52:944–949.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Frybova B, Drabek J, Lochmannova J, Douda

L, Hlava S, Zemkova D, Mixa V, Kyncl M, Zeman L, Rygl M and Keil R:

Cholelithiasis and choledocholithiasis in children; risk factors

for development. PLoS One. 13(e0196475)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Murphy PB, Vogt KN, Winick-Ng J, McClure

JA, Welk B and Jones SA: The increasing incidence of gallbladder

disease in children: A 20year perspective. J Pediatr Surg.

51:748–752. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Lascia AD, Tartaglia N, Pavone G, Pacilli

M, Ambrosi A, Buccino RV, Petruzzelli F, Menga MR, Fersini A and

Maddalena F: One-step versus two-step procedure for management

procedures for management of concurrent gallbladder and common bile

duct stones. Outcomes and cost analysis. Ann Ital Chir. 92:260–207.

2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Jones M, Johnson M, Samourjian E, Slauch K

and Ozobia N: ERCP and laparoscopic cholecystectomy in a combined

(one-step) procedure: A random comparison to the standard

(two-step) procedure. Surg Endosc. 27:1907–1912. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

de Medeiros KS, Aragão Fernandes AC, Fulco

Gonçalves G, Villarim CVO, Costa E Silva LC, de Sousa VMC, Meneses

Rêgo AC and Araújo-Filho I: Cholecystectomy before, simultaneously,

or after ERCP in patients with acute cholecystitis: A protocol for

systematic review and/or meta analysis. Medicine (Baltimore).

101(e30772)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Ebigbo A, Messmann H and Lee SH:

Artificial intelligence applications in Image-based diagnosis of

early esophageal and gastric neoplasms. Gastroenterology.

169:396–415.e2. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Sharma P and Hassan C: Artificial

intelligence and deep learning for upper gastrointestinal

neoplasia. Gastroenterology. 162:1056–1066. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Alhejaily AG: Artificial intelligence in

healthcare (review). Biomed Rep. 22(11)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|