Introduction

Ovarian reserve, reflecting the female reproductive

capacity, refers to the quantity and quality of follicles at

various developmental stages (1,2). A

significant reduction in baseline antral follicle count (AFC) and

anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) levels, coupled with an elevation in

basal follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), indicates decreased

ovarian reserve (DOR) (3). Women

with DOR exhibit impaired ovarian function, manifested by

suboptimal responses to ovarian stimulation, decreased oocyte

retrieval and higher cycle cancellation rates, all contributing to

a lowered probability of successful conception (4). The impact of DOR on fertility has

become increasingly pronounced with the delay of reproductive age.

The etiology of DOR is complex, involving age, genetics, immune

factors and environmental exposures (5). For example, Biallelic germline BRCA1

frameshift mutations associated with isolated DOR (6); Dehydroepiandrosterone regulates the

balance of CD4+/CD8+ T cells to improve balance of CD4+/CD8+ T

cells with DOR (7); A history of

heavy smoking may increase risk of DOR (8). Despite advances, the precise

molecular mechanisms underlying DOR remain incompletely understood,

highlighting the need to unravel the molecular pathways implicated

in DOR and identify potential therapeutic targets.

Small extracellular vesicles (referred to as

exosomes in the present study) play a key role in intercellular

communication by transferring diverse molecules, including

proteins, nucleic acids and metabolites (9,10).

Increasing evidence highlights their function as central mediators

of extracellular signaling, with substantial implications for

biological processes, such as insulin signaling, lipolysis and

inflammation (11,12). Exosomes have been extensively

studied in the context of female reproductive disorders (13), such as polycystic ovary syndrome

(PCOS) (14,15), intrauterine adhesion (16), premature ovarian insufficiency

(POI) (17) and premature ovarian

failure (18). However, the

expression of exosome-derived circular RNAs (circRNAs) in DOR

follicles remains underexplored. Oxidative stress, caused by an

imbalance between pro-oxidants, such as reactive oxygen species

(ROS) and nitrogen species, and the body's antioxidant defenses,

can result in cellular damage to DNA, proteins and lipids (19). This imbalance is a recognized

contributor to fertility decline in both sexes (20) and plays a marked role in ovarian

aging (21). Huang et al

(22) observed a notable decrease

in the oxidative stress marker glutathione in follicular fluid from

individuals with DOR compared with that in healthy controls.

Despite these observations on oxidative stress in DOR, the precise

mechanisms by which circRNAs participate in regulation remain

poorly understood and are the subject of ongoing research.

To the best of our knowledge, no previous studies

have explored the alterations in exosomal circRNA profiles in the

follicular fluid of individuals with DOR. The present study

represents the first attempt to assess the variations in circRNA

expression within exosomes from the follicular fluid of patients

with DOR. The current study aimed to evaluate the influence of key

differentially expressed circRNAs on granulosa cells in DOR in

terms of cell viability and oxidative stress, in an effort to

identify potential therapeutic targets for DOR.

Materials and methods

Clinical samples

In total, 6 women diagnosed with DOR and 6

age-matched control women (median age, 32 years; range, 31-34

years) were recruited from Fujian Maternity and Child Health

Hospital (Fuzhou, China), with ethics approval granted by the

Ethics Committee of Fujian Maternity and Child Health Hospital

(approval no. 2023KYLLR01082). Controls were women who presented

for a routine fertility check-up or preconception consultation and

were found to have no significant infertility or known fertility

issues. All participants provided written informed consent. All

patients presented to the hospital between January 2020 and

December 2020. The subjects met the diagnostic criteria for DOR

based on AMH <1.1 ng/ml and AFC <5 on transvaginal ultrasound

(23,24). Exclusion criteria included any

history of medication affecting glucose or lipid metabolism, as

well as known conditions that cause hormonal, metabolic and

reproductive abnormalities, such as Cushing's syndrome,

endometriosis, congenital adrenal hyperplasia or androgen-secreting

tumors. Preovulatory follicular fluid was collected from

participants during oocyte retrieval, and samples were subsequently

stored at -80˚C for RNA extraction and exosome isolation. The

clinical characteristics of patients with DOR were obtained from

medical records.

Exosome isolation

To identify differentially expressed circRNAs in

exosomes of individuals with DOR and normal controls, exosomes were

isolated from the follicular fluid of both groups using

ultracentrifugation, as previously described (25). In brief, 500 µl follicular fluid

was centrifuged at 10,000 x g for 45 min at 4˚C. The supernatant

was filtered through a 0.45-µm membrane, and the filtrate was

collected and transferred to a new centrifuge tube.

Ultracentrifugation was then performed at 100,000 x g for 70 min at

4˚C. After removal of the supernatant, the pellet was resuspended

in ice-cold PBS. The sample was subjected to another round of

ultracentrifugation at 100,000 x g for 70 min at 4˚C. The resulting

precipitate was resuspended in 100 µl PBS. The isolated exosomes

were stored at -80˚C for further analysis.

Exosome analysis

Exosome isolation quality was assessed by diluting

the samples with PBS (w/v=1:100), followed by analysis using the

NanoSight LM10 instrument (Malvern Instruments, Ltd.) according to

the manufacturer's instructions. Size and concentration were

quantified through the Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis 2.0 (NTA 2.0)

software (Malvern Instruments, Ltd.).

Transmission electron microscopy

(TEM)

To examine the structural characteristics of the

isolated exosomes, 10 µl exosome suspension was carefully placed

onto a 300 mesh formvar/carbon-coated copper grid (MilliporeSigma).

The exosomes were allowed to adsorb to the grid for 1 min at room

temperature, after which excess liquid was removed to ensure

optimal sample preparation. The adsorbed exosomes were then

subjected to negative staining with 2.5% uranyl acetate for 5 min

and embedded with 1% methyl cellulose (Sigma-Aldrich, Shanghai,

China) on ice for 10 min. Following staining, the samples were

air-dried for several minutes at room temperature. Finally, the

exosomes were analyzed using TEM (FEI Tecnai 12; Philips Medical

Systems B.V.) at a magnification of x60,000 to observe their

structural features.

Western blot analysis

Total protein of samples was separated by

radio-immunoprecipitation assay lysis buffer (Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology), and then quantified using the BCA Protein Assay Kit

(Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). A total of 20 µg protein

from each isolated exosome sample and follicular fluid [negative

control (NC)] were subjected to SDS-PAGE on 10% gels for protein

separation. The separated proteins were then transferred onto PVDF

membranes and incubated overnight in TBS-Tween (TBS-T) buffer,

containing Tris (15 mM, pH 7.8), NaCl (100 mM), Tween-20 (0.5%),

with 5% defatted dry milk at 4˚C. The membranes were subsequently

incubated with primary antibodies against CD9 (1:1,000; cat. no.

ab236630; Abcam) and CD63 (1:1,000; cat. no. A5271; ABclonal

Biotech Co., Ltd.) in TBS-T buffer with 5% defatted dry milk for 3

h at 25˚C. After washing with TBS-T buffer, the membranes were

incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (goat

anti-mouse/rabbit IgG; cat. nos. SA00001-1& SA00001-2;

Proteintech Group, Inc.) at a 1:2,000 dilution for 1 h at 25˚C.

Protein bands were visualized using an electrochemiluminescence

detection system (Pierce ECL Western; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.). All experiments were repeated at least three times to ensure

the reliability and reproducibility of the results.

circRNA sequencing and analysis

circRNA sequencing was employed to identify

differentially expressed circRNAs in follicular fluid exosomes

between four DOR and four normal control samples, as previously

described (26). A concentration

≥50 ng/µl was used for each sample, and the EVs concentration was

determined by NTA software as the basis for standardization. Total

RNA was extracted from exosomes using TRIzol® (cat. no.

155976018; Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) as per the

manufacturer's protocol, with RNA quality assessed using the

optical density (OD)260/OD280 ratio between

1.8 and 2.0, adhering to establish quality control standards. For

library construction, RNA was processed with the TruSeq Stranded

Total RNA library preparation kit (cat. no. 20020599; Illumina,

Inc.). Post-preparation, library quality and quantity were

evaluated using the Bioanalyzer 2100 system (Agilent Technologies,

Inc.). The prepared library, at a concentration of 10 pM, was

converted into single-stranded DNA, which was then captured and

amplified in situ to form clusters (using a dilute NaOH for

denaturation and then hybiridzation and extension in ~35 cycles).

Sequencing was performed for 150 cycles in paired-end mode on the

Illumina HiSeq4000 sequencer (Illumina, Inc.) with the HiSeq

3000/4000 SBS Kit (150 cycles) (cat. no. TG-410-1002; Illumina,

Inc.), ensuring a Q30 quality score. Following trimming of 30

adapters with Cutadapt software (v3.4; National Bioinformatics

Infrastructure Sweden) and removal of low-quality sequences,

high-quality read fragments were used for circRNA analysis.

High-quality reads were aligned using the STAR software (v2.5.1b;

National Human Genome Research Institute of NIH), while circRNAs

were identified and analyzed with the DCC program (v0.4.4;

Karolinska Institutet), and annotation of the detected circRNAs was

performed using the Circ2Traits (http://gyanxet-beta.com/circdb/) and circBase

(https://www.circbase.org/) databases.

Data normalization and differential expression analysis of circRNAs

were conducted with the EdgeR software (v3.16.5; https://bioconductor.org/packages/edgeR), with

circRNAs considered differentially expressed when fold change was

≥2.0 and P<0.05. Heatmaps and clustering of differentially

expressed circRNAs were generated using the R ggplot2 package

(v2.1.0; https://www.rdocumentation.org/packages/ggplot2/versions/2.1.0)

(27). Functional predictions of

circRNAs were performed through Gene Ontology (GO; https://geneontology.org/) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of

Genes and Genomes (KEGG; https://www.kegg.jp/) analyses on the associated

genes. These analyses were carried out using the Database for

Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (https://david.ncifcrf.gov/home.jsp) (28). Terms with

Benjamini-Hochberg-adjusted P<0.05 and containing ≥5 annotated

genes were considered statistically significant. The raw data were

uploaded to the National Centre for Biotechnology Information

Sequence Read Archive database (BioProject accession no.

PRJNA1191187).

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR

(RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted from the follicular fluid

precipitate following centrifugation using TRIzol. RT of the RNA

into cDNA was carried out using a PrimeScript ™ RT reagent kit with

gDNA Eraser (Perfect Real Time) (cat. no. RR047Q; Takara

Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) according to the manufacturer's

instructions. The resulting cDNA was subsequently amplified by

qPCR, utilizing the AceQ Universal SYBR qPCR Master Mix (cat. no.

Q511; Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd.) and the ABI 7500 PCR system (cat.

no. 4351104; Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.).

The amplification protocol included an initial denaturation step at

95˚C for 15 sec, followed by 45 cycles of amplification at 55-60˚C

for 15 sec, and a final extension step at 72˚C for 15 sec. Relative

RNA expression levels were calculated using the 2-ΔΔCq

method and using GAPDH as the reference gene (29). All reactions were performed in

triplicate to ensure reliability and reproducibility of the

results. The reference sequence accession nos. of circRNAs were

derived from the circBank database (http://www.circbank.cn/#/home). The circBank IDs of

hsa_circ_0000344, hsa_circ_0001126, hsa_circ_0005379,

hsa_circ_0005777 and hsa_circ_0007509 are hsa_RSF1_0004200,

hsa_PTPRA_0009800, hsa_GDI2_0006400, hsa_ARHGEF28_0005700 and

hsa_PPP4R1_0010200, respectively. Primer sequences are provided in

Table I.

| Table IPrimer sequences used in the present

study. |

Table I

Primer sequences used in the present

study.

| Gene | Sequence

(5'-3') |

|---|

| GAPDH | F:

ACAGCAACAGGGTGGTGGAC |

| | R:

TTTGAGGGTGCAGCGAACTT |

|

hsa-circ-0000344 | F:

GCTTGGTGTATGTTGGTATCAGT |

| | R:

GAAGGCAGGCAGTATGGTATC |

|

hsa-circ-0001126 | F:

ACAAGAACAGCAAGCACCAAT |

| | R:

GCATCATCCATTACCACTCAGT |

|

hsa-circ-0005379 | F:

AGATCAACCGTGTTATGAAACCAT |

| | R:

TTGCCATTCACTGACATTATACCT |

|

hsa-circ-0005777 | F:

TTCGTGTGCTTCCAACTTGA |

| | R:

CACTGGGACTGGTTTCTGTAG |

|

hsa-circ-0007509 | F:

CGAAAGGCTTGTGCTGAATG |

| | R:

TCCAGGGCTGAAGGTATAATAATC |

Cell culture

The KGN ovarian granulosa cell line was obtained

from Shanghai Fuheng Biotechnology Co., Ltd., and cultured in

DMEM/F12 medium (cat. no. 11320033, Gibco; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum

(HyClone; Cytiva) and 0.5% penicillin-streptomycin (Invitrogen;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The cells were maintained in a 5%

CO2 atmosphere at 37˚C with 100% humidity.

Cyclophosphamide (CTX; cat. no. HY-17420; MedChemExpress) may

destroy the follicular pool, leading to primary ovarian

insufficiency (30). To induce

cell damage, CTX was administered at concentrations of 0, 10, 15,

20, 25 and 30 µM for 24 h at 37˚C. The NC was treated without

CTX.

Cell transfection

To investigate the role of hsa_circ_0005379 in KGN

cells, short hairpin (sh)-hsa_circ_0005379 and NC

sh-circRNA(pLKO.1), as well as hsa_circ_0005379-overexpression (OE)

and NC plasmids (pcDNA3.1) were synthesized by GeneChem, Inc. KGN

cells were transfected for 5 h with the corresponding plasmids (500

µM) using Lipofectamine® 2000 reagent (Invitrogen;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) at room temperature according to

the manufacturer's protocol, as previously described (31). The transfection efficiency was

detected by RT-qPCR 48 h after transfection. All subsequent

experiments were performed 48 h after transfection. The sequences

of sh-hsa_circ_0005379 and NC are presented in Table II.

| Table IISequence of shRNAs and scramble

control. |

Table II

Sequence of shRNAs and scramble

control.

| Name | Sequence

(5'-3') |

|---|

|

hsa-circ-0005379-sh1 |

CTGTTGTGCTGACCTCTGA |

|

hsa-circ-0005379-sh2 |

GACAGCTTCATGGTCCAGA |

|

hsa-circ-0005379-sh3 |

TACCAGGATGTGCTGGTCA |

|

sh-hsa-circ-0005379-NC |

CCTAAGGTTAAGTCGCCCTCG |

Cell viability assay

Cell viability was assessed using Cell Counting

Kit-8 (CCK-8) (cat. no. A311; Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd.) according

to the manufacturer's instructions, as previously described

(32). Briefly, 10 µl CCK-8

reagent were added to each well of a 96-well plate

(3x103 cells/well), followed by incubation for 1 h at

37˚C. Absorbance at 450 nm was measured using a BioTek

multifunctional microplate reader (Agilent Technologies, Inc.).

Cell apoptosis assay

A total of 1x106 cells were collected in

the logarithmic phase, washed with PBS and then digested with

trypsin (cat. no. C0205; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology).

After treatment with 30 µM CTX, 1x105 KGN cells were

incubated with 5 µl Annexin V-APC and 5 µl PI at room temperature

for 15 min as per the manufacturer's instructions (Beyotime

Institute of Biotechnology). The apoptosis rate was then evaluated

by flow cytometry (FACSCalibur; BD Biosciences), and the data were

analyzed utilizing FlowJo software (version 10.0.7; TreeStar,

Inc.).

Biochemical assays of malondialdehyde

(MDA) and superoxide dismutase (SOD)

MDA and SOD levels of KGN cells were measured using

the MDA detection kit (cat. no. A003-1) and SOD detection kit (cat.

no. A001-3) from Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute,

following the manufacturer's protocols.

ROS detection

ROS detection was performed using a ROS detection

kit (cat. no. MA0219; Dalian Meilun Biotechnology Co., Ltd.). KGN

cells were seeded in a six-well plate and treated with 30 µM CTX

for 24 h at room temperature. Each well received 1 ml

dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA; prepared at a

1:1,000 dilution in basal DMEM/F12) and incubated at 37˚C for 20

min to allow probe uptake. Following incubation, the cells were

washed with 1X PBS three times to remove excess probe. The cells

were then digested with 0.25% Trypsin (cat. no. C0205; Beyotime

Institute of Biotechnology), centrifuged at 300 x g for 5 min at

4˚C, and resuspended in 300 µl fresh ice-cold basal DMEM/F12

medium. ROS levels were quantified by flow cytometry (FACSCalibur;

BD Biosciences), with excitation and emission wavelengths set at

488 nm and 525 nm, respectively, as previously described (33). The data were analyzed utilizing

FlowJo software (version 10.0.7; TreeStar, Inc.). ROS mean

fluorescence intensity ratio was calculated as the fluorescently

stained cell number/total cell number.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were independently performed at

least 3 times. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation

and data analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism v9 software

(GraphPad; Dotmatics). Comparisons between two groups were

performed using unpaired Student's t-test. Comparisons among three

or more groups were conducted using one-way ANOVA followed by

Tukey's multiple comparisons test. P<0.05 was considered to

indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Cohort characteristics and exosome

characterization

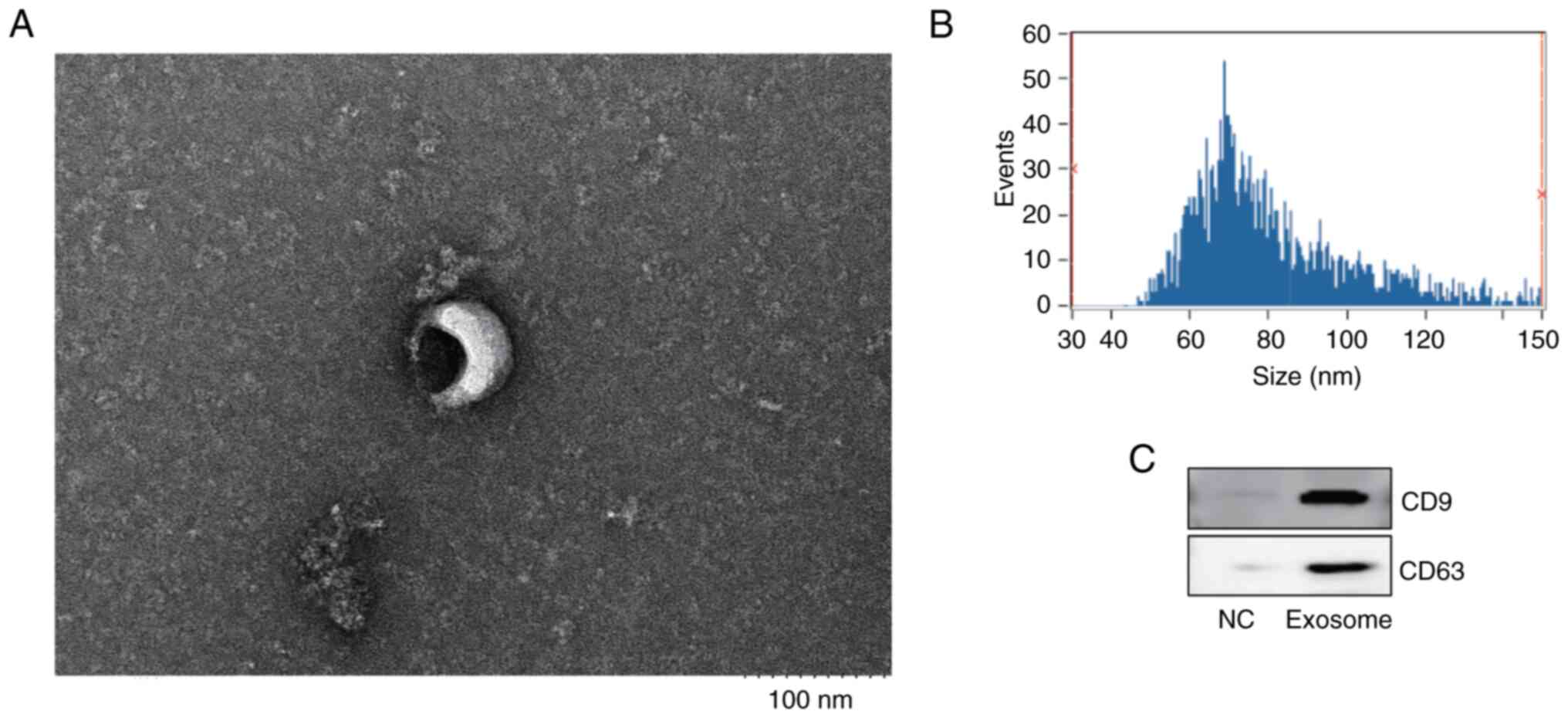

The clinical characteristics of patients with DOR

and controls were evaluated (Table

III), and no significant differences in age, BMI, duration of

infertility, estradiol, follicle-stimulating hormone, luteinizing

hormone, anti-mullerian hormone and cleaved zygotes ratio between

the two groups were observed. By contrast, significant differences

in AMH and AFC levels between the DOR and control groups were

detected. Significant decreases in AMH and AFC usually indicate a

significant decline in ovarian reserve function, which may be

accompanied by reduced fertility or an increased risk of

menopausal-related conditions. Exosomes were then isolated from the

follicular fluid of both DOR and control groups. TEM analysis was

performed to examine exosome size and morphology (Fig. 1A). Nanoparticle tracking analysis

determined the exosome size and concentration, revealing that the

mean diameter was 81.18 nm and the concentration was

2.79x109 particles/ml (Fig.

1B). Additionally, the presence of the exosome markers CD9 and

CD63 was confirmed through western blot analysis of follicular

fluid exosomes (Fig. 1C).

| Table IIIGeneral characteristics of the study

population. |

Table III

General characteristics of the study

population.

|

Characteristics | Normal control

group | Decreased ovarian

reserve group | P-value |

|---|

| Age, years | 31.50±1.73 | 32.50±1.29 | 0.390 |

| BMI | 20.41±3.10 | 22.18±4.38 | 0.530 |

| Duration of

infertility, years | 2.25±0.50 | 3.25±1.26 | 0.190 |

| Estradiol baseline,

pg/ml | 31.25±10.71 | 44.25±13.45 | 0.180 |

|

Follicle-stimulating hormone baseline,

mIU/ml | 5.98±0.54 | 8.27±3.70 | 0.270 |

| Luteinizing hormone

baseline, mIU/ml | 3.55±0.76 | 3.48±1.01 | 0.910 |

| Anti-mullerian

hormone baseline, ng/ml | 3.91±0.71 | 0.73±0.23 | <0.001 |

| Antral follicle

count | 10.75±2.36 | 4.00±2.45 | <0.010 |

| Cleaved zygotes,

% | 91.25±12.74 | 82.50±13.58 | 0.380 |

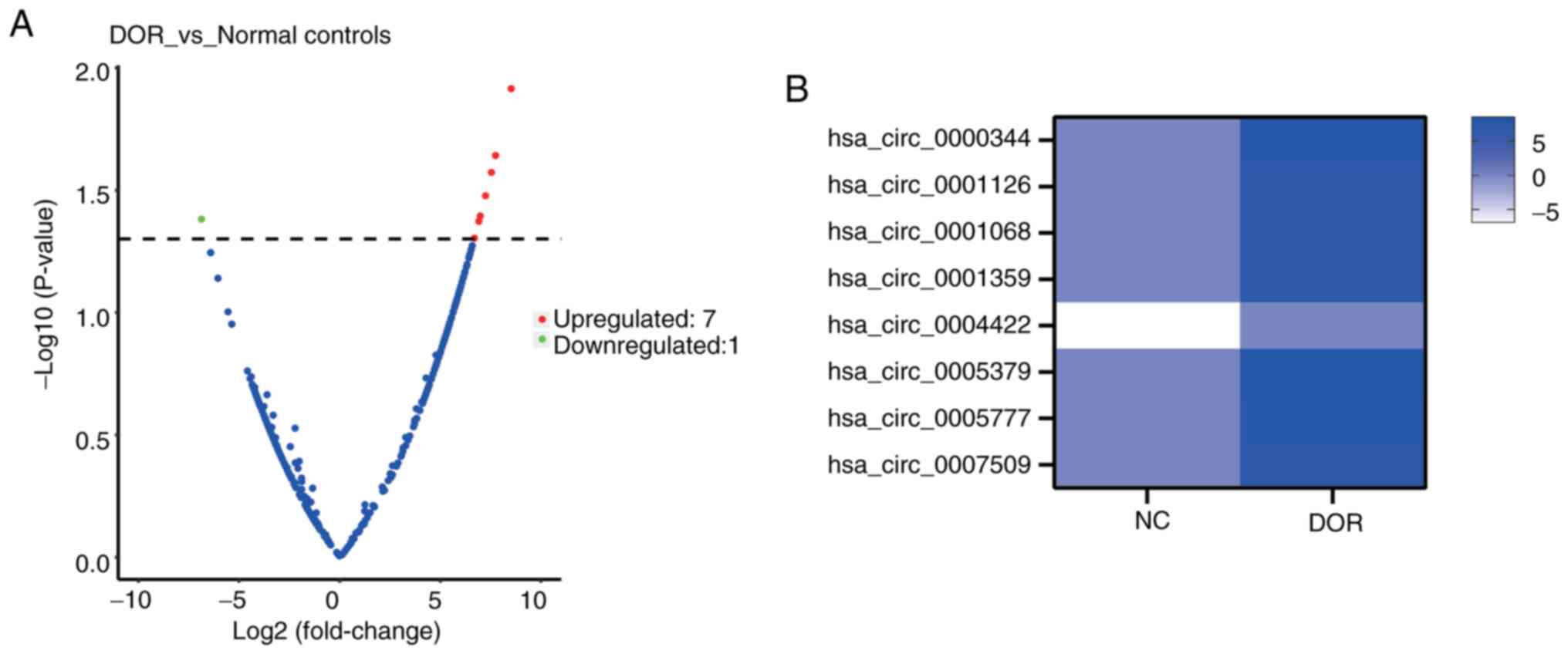

Expression profiling of circRNAs in

patients with DOR

Differentially expressed circRNAs in exosomes were

identified and summarized in Table

IV. Information on the fold changes, P-values and the

corresponding host genes of all eight circRNAs is provided. As

illustrated in Fig. 2A, the

volcano plot revealed a clear separation between the DOR and

control groups, with seven circRNAs upregulated and one

downregulated in the DOR group. The heatmap in Fig. 2B displays the expression profiles

of these eight differentially expressed circRNAs.

| Table IVDifferentially expressed circRNAs

between patients with decreased ovarian reserve and normal

controls. |

Table IV

Differentially expressed circRNAs

between patients with decreased ovarian reserve and normal

controls.

| circRNA ID | Log2 fold

change | P-value | Host gene |

|---|

|

hsa_circ_0000344 | 7.50 | 0.026802 | RSF1 |

|

hsa_circ_0001126 | 6.95 | 0.040373 | PTPRA |

|

hsa_circ_0001068 | 6.66 | 0.049757 | MGAT5 |

|

hsa_circ_0001359 | 6.88 | 0.042484 | PHC3 |

|

hsa_circ_0004422 | -6.90 | 0.041604 | - |

|

hsa_circ_0005379 | 8.49 | 0.012191 | GDI2 |

|

hsa_circ_0005777 | 7.71 | 0.022859 | RGNEF |

|

hsa_circ_0007509 | 7.21 | 0.033397 | PPP4R1 |

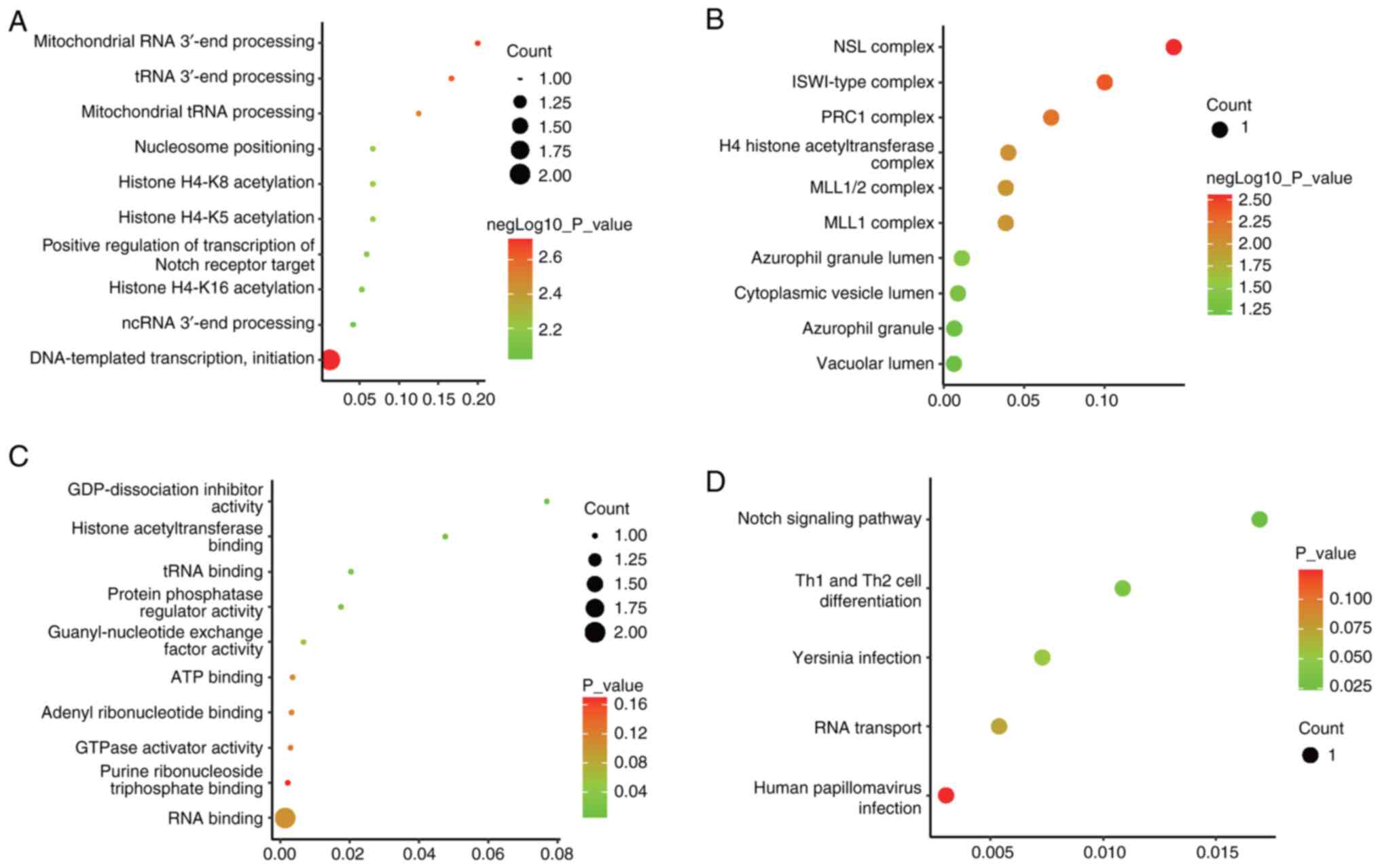

Functional enrichment analysis

To explore the potential roles of differentially

expressed circRNAs, GO and KEGG analyses were performed, focusing

on the host genes associated with these circRNAs. The top 10

enriched terms related to molecular functions, cellular components

and biological processes are summarized in Fig. 3A-C. The leading biological

processes included ‘DNA-templated transcription, initiation’

‘mitochondrial RNA 3'-end processing’ and ‘tRNA 3'-end processing’

(Fig. 3A). For cellular

components, the most enriched terms were ‘NSL complex’, ‘ISWI-type

complex’ and ‘PRC1 complex’ (Fig.

3B). Regarding molecular functions, the most significant terms

were ‘GDP-dissociation inhibitor activity’, ‘histone

acetyltransferase binding’ and ‘tRNA binding’ (Fig. 3C). Additionally, five KEGG pathways

were enriched (Fig. 3D), with the

‘Notch signaling pathway’ and ‘Th1 and Th2 cell differentiation’

showing significant enrichment (P<0.05), which suggests

that these pathways may contribute to the pathogenesis of DOR.

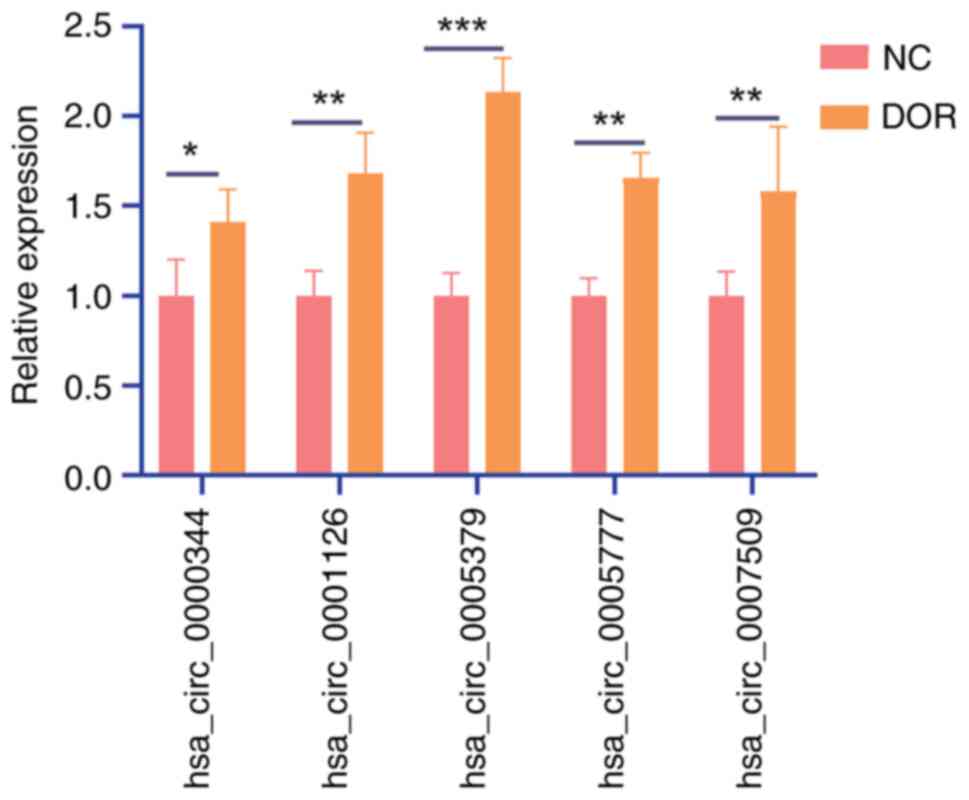

Verification of selected circRNAs and

the function of hsa_circ_0005379

In total, 6 patients with DOR and 6 normal controls

were included for RT-qPCR validation. The top five most

significantly altered genes, based on the P-value from the RNA-seq

data, were selected for further validation (Table IV). Hsa_circ_0005379 was

identified as the most significantly upregulated circRNA in the DOR

group (Fig. 4) and was selected

for subsequent analysis. Ovarian granulosa KGN cells were treated

with varying concentrations of CTX (0, 10, 15, 20, 25 and 30 µM) to

induce cellular damage. The CCK-8 assay demonstrated a

dose-dependent decrease in KGN cell viability, with higher

concentrations of CTX producing a more pronounced effect (Fig. 5A). The 30 µM CTX treatment was

found to be the most effective in reducing cell viability. To

further investigate the biological role of hsa_circ_0005379, it was

selected as the optimal concentration for subsequent experiments.

Then, KGN cells were transfected with shRNAs or an overexpression

vector to explore the function of hsa_circ_0005379 (Fig. 5B and C). The results showed that sh1 had the

highest knockdown efficiency and was therefore used for subsequent

experiments (Fig. 5B). Following

CTX treatment and transfection of the overexpression vector, a

significant increase in the apoptosis rate was observed compared

with that in CTX-treated KGN cells transfected with the NC vector.

By contrast, knockdown of hsa_circ_0005379 with CTX treatment

resulted in a decrease in apoptosis compared with

sh-hsa_circ_0005379-NC+CTX group (Fig.

5D).

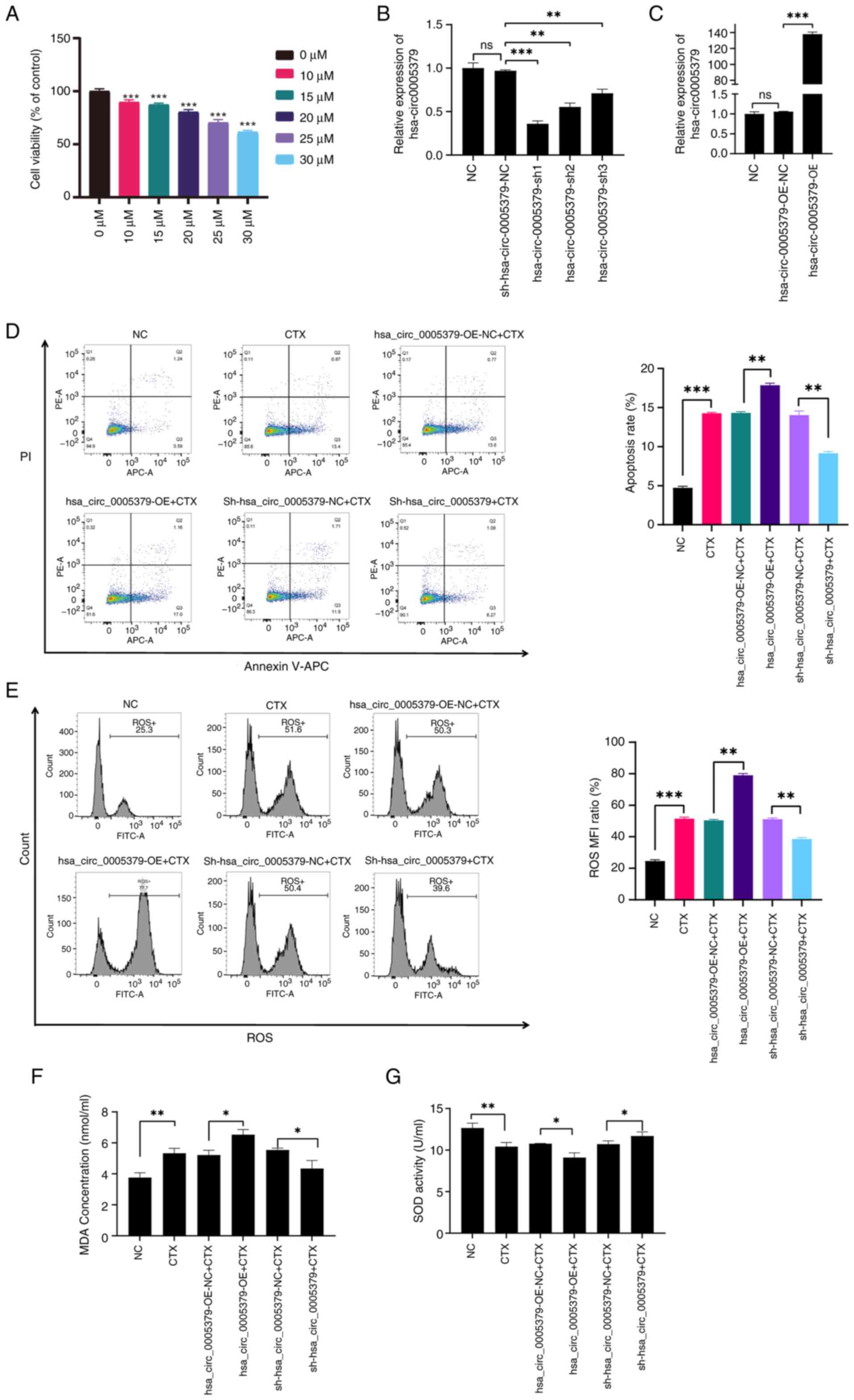

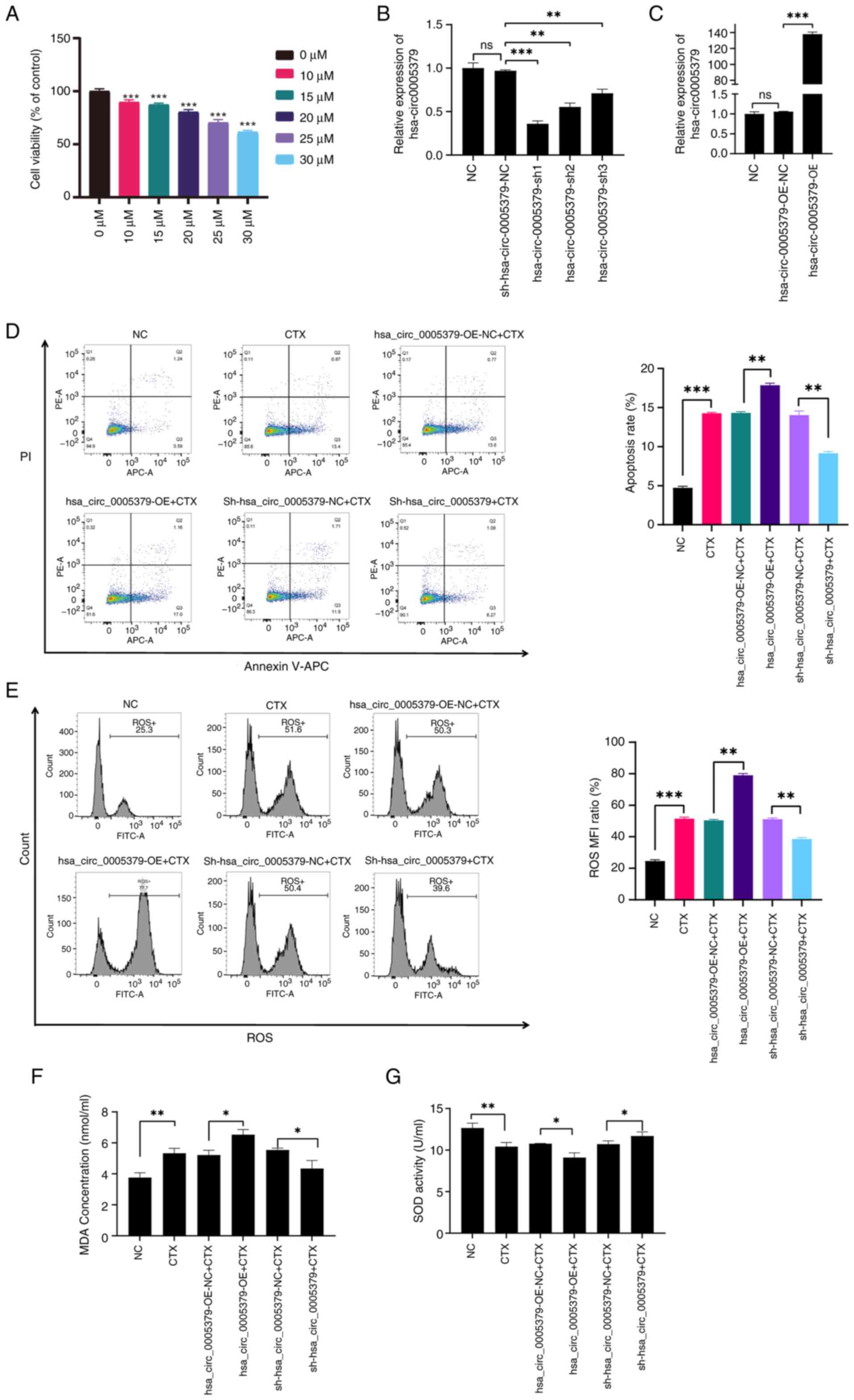

| Figure 5Function of hsa_circ_0005379 in

CTX-induced KGN ovarian granulosa cells. (A) Different gradient

concentrations (0, 10, 15, 20, 25 and 30 µM) of CTX were used to

induce ovarian granulosa cell damage, and Cell Counting Kit-8 assay

was used to detect KGN cell viability. (B) RT-qPCR analysis of

hsa_circ_0005379 expression after transfection with three shRNAs

and negative control sh-NC. (C) RT-qPCR analysis of

hsa_circ_0005379 expression after transfection with OE vector and

an empty OE-NC vector. (D) The apoptosis of sh-hsa_circ_0005379 or

hsa_circ_0005379-OE transfected KGN cells was detected using

annexin V/PI staining. (E) Flow cytometry was used to detect the

ROS level of cells after different treatments. The concentration of

(F) MDA and (G) SOD in KGN cells with different treatments was

determined using corresponding biochemistry detection kits. n=3,

*P<0.05, **P<0.01 and

***P<0.001 vs. 0 µΜ or as indicated. CTX,

cyclophosphamide; RT-qPCR, reverse transcription-quantitative PCR;

OE, overexpression; NC, negative control; sh, short hairpin; SOD,

superoxide dismutase; MDA, malondialdehyde; ROS, reactive oxygen

species; MFI, mean fluorescence intensity; ns, not significant. |

The effect of hsa_circ_0005379 on oxidative stress

in CTX-treated cells was further examined. The results indicated

increased levels of ROS and MDA in the hsa_circ_0005379-OE group,

whereas the sh-hsa_circ_0005379 group showed reduced levels of both

markers, compared with those in the corresponding NC groups

(Fig. 5E and F). By contrast, the antioxidant enzyme

SOD, which is involved in aging processes, displayed an inverse

pattern compared with that of ROS and MDA (Fig. 5G). These findings suggest that

silencing hsa_circ_0005379 may alleviate oxidative stress in

DOR.

Discussion

DOR is characterized by reduced oocyte quality and

quantity, leading to impaired ovarian endocrine function and

diminished fertility in women (34). The follicular microenvironment is

believed to play a critical role in oocyte maturation and

development (22). Therefore, the

present study investigated the follicular microenvironment

isolating exosomes (small vesicles containing biological molecules)

from the follicular fluid of patients with DOR. A subsequent

analysis of follicular exosomes using circRNA sequencing was

performed, thus conducting the first examination of the exosomal

circRNA profile in the follicular fluid of individuals with DOR, to

the best of our knowledge.

circRNAs, a class of single-stranded RNA molecules,

are characterized by covalently closed loops. These molecules are

widely distributed across various organisms, ranging from viruses

to mammals. Considerable progress has been made in understanding

the biogenesis, regulation, localization, degradation and

modification of circRNAs (35,36).

In the present study, eight differentially expressed circRNAs were

identified between patient with DOR and normal controls, followed

by enrichment analyses. GO biological process enrichment analysis

revealed the involvement of the identified circRNAs in numerous

biological processes, including ‘DNA-templated transcription,

initiation’. Notably, the enrichment of this process was also

observed in rats with DOR, induced by tripterygium glycoside tablet

suspension (37). Additionally,

two key pathways were found to be significantly enriched: ‘Notch

signaling pathway’ and ‘Th1 and Th2 cell differentiation’. Hughes

et al (38) reported that

elevated ovarian oocyte death triggered an increase in Notch

signaling and ovarian inflammation, and that Notch signaling

pathway activation in granulosa cells exacerbated apoptosis.

However, the specific role of the Notch pathway in DOR remains to

be further elucidated. In addition, increased oxidative stress

caused by smoking can further promote the onset and development of

cancer by amplifying the inflammatory response and activating

Notch-1 signaling (39).

Overexpression of long non-coding RNA NONHSAT098487.2 has been

shown to inhibit H2O2-induced oxidative

stress injury in cardiomyocytes by activating Notch signaling

pathway (40) and polystyrene

microplastics have been demonstrated to promote colon barrier

damage through oxidative stress-mediated overactivation of the

Notch signaling pathway (41).

These studies suggest an association between oxidative stress and

Notch pathway activation. Since oxidative stress is closely related

to DOR (42), future studies may

explore the association between DOR and the Notch pathway in terms

of oxidative stress generation. Furthermore, a recent study showed

that polysaccharides could collectively inhibit inflammation,

apoptosis and oxidative stress in asthmatic rats via regulation of

T helper (Th)1/Th2 and Th17/Treg cell immune imbalances (43). Dehydroepiandrosterone has been

shown to improve Th1 immune responses and regulate the balance of

the Th1/Th2 response in patients with DOR (7). These studies collectively suggest

that Th1/Th2 responses may be involved in the regulation of

oxidative stress in DOR.

During follicular development, the interaction

between oocytes and adjacent granulosa cells is essential for the

production of fertilizable oocytes and the regulation of ovarian

function (44-46).

Thus, diminished oocyte competence in women with DOR may stem from

dysregulated granulosa cell function (47). CTX exposure causes premature

ovarian insufficiency (48). In

the present study, a DOR cell model was established by exposing

granulosa cells to CTX, and this model was subsequently used to

investigate the role of hsa_circ_0005379.

Hsa_circ_0005379 has previously been identified as a

key regulator in neuroblastoma (49). In the present study, upregulation

of hsa_circ_0005379 was observed in exosomes isolated from the

follicular fluid of patients with DOR. Silencing hsa_circ_0005379

partially reversed granulosa cell apoptosis. A significant

association between oxidative stress and aging has been reported

(50), with oxidative stress also

being recognized as a major contributor to ovarian aging (21). Alterations in ROS, MDA and SOD

levels reflect changes in oxidative stress, providing an indication

of ovarian aging. Increased oxidative stress has been observed in

both animal models and patients with DOR (22,51).

In the present study, reduced hsa_circ_0005379 levels alleviated

oxidative stress in CTX-induced DOR cells, suggesting the potential

of hsa_circ_0005379 as a therapeutic target for DOR.

In addition, other circRNAs have been reported in

the literature to be associated with DOR. For example,

hsa_circ_0031584 has been indicated to be an important molecule

regulating the mitotic process of granulosa cells in DOR (52). The findings of the present study

were compared with studies on circRNAs in other female reproductive

diseases, noting conserved roles in oxidative stress regulation.

For example, Bu-Shen-Ning-Xin decoction has been shown to inhibit

oxidative stress by regulating circRNA_012284 expression in POI.

Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes

secreted circBRCA1, which directly sponged microRNA (miR)-642a-5p

to upregulate FOXO1, thereby preventing oxidative stress injuries

in granulosa cells and protecting ovarian function in rats with POI

(53). Furthermore, knockdown of

hsa_circ_0118530 was shown to suppress PCOS progression by

inhibiting oxidative stress and inflammation factor release

(54). In another study,

overexpression of circ_0097636 protected PCOS cell models from

dihydrotestosterone-induced oxidative stress by increasing sirtuin

3 expression (55).

Hsa_circ_0005777 is derived from the cyclization of

the host gene rho guanine nucleotide exchange factor (RGNEF);

circRGNEF promotes bladder cancer progression via regulation of the

miR-548/KIF2C axis (56).

Similarly, hsa_circ_0001126 originates from the protein tyrosine

phosphatase receptor type a (PTPRA) gene, and circPTPRA inhibits

RNA N6-methyladenosine recognition by interacting with insulin-like

growth factor 2 mRNA-binding protein 1, thereby suppressing bladder

cancer progression (57). Future

investigations involving small interfering RNA-mediated knockdown

or overexpression of these circRNAs are essential to further

elucidate their involvement in DOR pathogenesis.

The present study has certain limitations. The small

sample size represents an important constraint in this pilot

investigation. Due to the strict exclusion criteria (such as the

lack of history of medications known to influence glucose and lipid

metabolism) and the challenges in recruiting patients with

well-defined DOR, achieving a larger cohort was logistically

difficult within the study timeframe. In future studies, a

multicenter collaboration is necessary to recruit a larger, more

diverse cohort. Additionally, the exclusion of individuals with a

history of medications affecting glucose or lipid metabolism, as

well as conditions such as Cushing's syndrome, congenital adrenal

hyperplasia, androgen-secreting tumors and endometriosis, is rooted

in the need to minimize confounding variables. These factors could

independently alter metabolic or hormonal outcomes under

investigation, thereby obscuring the true effects of the

intervention or exposure being studied. For example, medications

influencing glucose/lipid metabolism (such as insulin, statins and

glucocorticoids) could mask or exaggerate metabolic changes

(58), compromising the assessment

of the study's primary endpoints. Furthermore, endocrine disorders

(such as Cushing's syndrome, congenital adrenal hyperplasia and

androgen-secreting tumors) directly disrupt hormonal or metabolic

pathways, potentially mimicking outcomes relevant to conditions

like PCOS or insulin resistance (59-61).

Endometriosis is known to alter follicular fluid composition and

inflammatory pathways, which could independently influence the

present study's endpoints, such as ROS levels and associated

pathways (20). By excluding these

factors, the internal validity of the present study was enhanced,

ensuring that the observed effects are more likely attributable to

the variables under investigation rather than pre-existing

conditions or treatments. Excluding certain groups of individuals

bolsters confidence in causal inferences by reducing confounding

factors, particularly in studies focusing on metabolic or endocrine

mechanisms (such as studies evaluating insulin sensitivity or

androgen levels). By contrast, the homogeneity of the study

population may limit external validity. For instance, the results

may not apply to individuals with overlapping conditions (such as

patients with PCOS or untreated congenital adrenal hyperplasia) or

those on common glucose/lipid-modifying therapies. This restricts

the findings to a narrower, ‘idealized’ population. If the excluded

conditions are rare (such as androgen-secreting tumors), their

omission may not markedly impact applicability. As a preliminary

study, the findings may be specific to idiopathic DOR. Future

research should include stratified analyses comparing subgroups

(patients with DOR with vs. without endometriosis) to evaluate the

broader applicability of these results, consistent with a recent

study on DOR heterogeneity (4).

In conclusion, the present study provided a

comprehensive profile of circRNA expression in exosomes isolated

from the follicular fluid of patients with DOR. Additionally, the

current study represents, to the best of our knowledge, the first

report on the role of hsa_circ_0005379 in DOR. The results

demonstrated that silencing hsa_circ_0005379 alleviated apoptosis

and oxidative stress in CTX-induced granulosa cells. However, the

underlying mechanisms through which hsa_circ_0005379 modulates

oxidative stress and contributes to DOR remain to be further

explored.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: The present study was funded by the Fujian Natural

Science Foundation (grant no. 2021J05083), the Joint Funds for the

Innovation of Science and Technology of Fujian Province (grant no.

2023Y9384), the Fujian Provincial Health Technology Project (grant

no. 2025QNGGA010) and the Zhejiang Medical and Health Project

(grant no. 2023KY781).

Availability of data and materials

The raw RNA sequencing data generated in the present

study may be found in the National Center for Biotechnology

Information Sequence Read database under accession number

PRJNA1191187 or at the following URL: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/?term=PRJNA1191187.

The other data generated in the present study may be requested from

the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

PH, YF and DL were responsible for the

conceptualization, design and execution of the study. PH, YF, JC

and DL were responsible for drafting and revising the manuscript.

SC, JC and CJ were responsible for resources and investigation. PH,

SC, JC, CJ and BL analyzed and interpreted the data. SC and JC were

responsible for reviewing and editing the manuscript. PH, YF and DL

confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read and

approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was approved by the Ethics

Committee of Fujian Maternity and Child Health Hospital (approval

no. 2023KYLLR01082; Fuzhou, China). Written informed consent was

obtained from all participants.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Rotshenker-Olshinka K, Michaeli J, Srebnik

N, Samueloff A, Magen S, Farkash R and Eldar-Geva T: Extended

fertility at highly advanced reproductive age is not related to

anti-Mullerian hormone concentrations. Reprod Biomed Online.

45:147–152. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Wen J, Huang K, Du X, Zhang H, Ding T,

Zhang C, Ma W, Zhong Y, Qu W, Liu Y, et al: Can Inhibin B Reflect

ovarian reserve of healthy reproductive age women effectively?

Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 12(626534)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Liang C, Zhang X, Qi C, Hu H, Zhang Q, Zhu

X and Fu Y: UHPLC-MS-MS analysis of oxylipins metabolomics

components of follicular fluid in infertile individuals with

diminished ovarian reserve. Reprod Biol Endocrinol.

19(143)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Cedars MI: Managing poor ovarian response

in the patient with diminished ovarian reserve. Fertil Steril.

117:655–656. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Park SU, Walsh L and Berkowitz KM:

Mechanisms of ovarian aging. Reproduction. 162:R19–R33.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Helbling-Leclerc A, Falampin M, Heddar A,

Guerrini-Rousseau L, Marchand M, Cavadias I, Auger N, Bressac-de

Paillerets B, Brugieres L, Lopez BS, et al: Biallelic Germline

BRCA1 Frameshift mutations associated with isolated diminished

ovarian reserve. Int J Mol Sci. 25(12460)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Zhang J, Qiu X, Gui Y, Xu Y, Li D and Wang

L: Dehydroepiandrosterone improves the ovarian reserve of women

with diminished ovarian reserve and is a potential regulator of the

immune response in the ovaries. Biosci Trends. 9:350–359.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Oladipupo I, Ali T, Hein DW, Pagidas K,

Bohler H, Doll MA, Mann ML, Gentry A, Chiang JL, Pierson RC, et al:

Association between cigarette smoking and ovarian reserve among

women seeking fertility care. PLoS One. 17(e0278998)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Ma X, Chen Z, Chen W, Chen Z and Meng X:

Exosome subpopulations: The isolation and the functions in

diseases. Gene. 893(147905)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Gregory CD and Rimmer MP: Extracellular

vesicles arising from apoptosis: Forms, functions, and

applications. J Pathol. 260:592–608. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Quan M and Kuang S: Exosomal secretion of

adipose tissue during various physiological states. Pharmaceutical

Res. 37(221)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Gallet R, Dawkins J, Valle J, Simsolo E,

de Couto G, Middleton R, Tseliou E, Luthringer D, Kreke M, Smith

RR, et al: Exosomes secreted by cardiosphere-derived cells reduce

scarring, attenuate adverse remodelling, and improve function in

acute and chronic porcine myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J.

38:201–211. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Esfandyari S, Elkafas H, Chugh RM, Park

HS, Navarro A and Al-Hendy A: Exosomes as biomarkers for female

reproductive diseases diagnosis and therapy. Int J Mol Sci.

22(2165)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Yuan D, Luo J, Sun Y, Hao L, Zheng J and

Yang Z: PCOS follicular fluid derived exosomal miR-424-5p induces

granulosa cells senescence by targeting CDCA4 expression. Cell

Signal. 85(110030)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Cao J, Huo P, Cui K, Wei H, Cao J, Wang J,

Liu Q, Lei X and Zhang S: Follicular fluid-derived exosomal

miR-143-3p/miR-155-5p regulate follicular dysplasia by modulating

glycolysis in granulosa cells in polycystic ovary syndrome. Cell

Commun Signal. 20(61)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Yao Y, Chen R, Wang G, Zhang Y and Liu F:

Exosomes derived from mesenchymal stem cells reverse EMT via

TGF-beta1/Smad pathway and promote repair of damaged endometrium.

Stem Cell Res Ther. 10(225)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Li Z, Zhang M, Zheng J, Tian Y, Zhang H,

Tan Y, Li Q, Zhang J and Huang X: Human umbilical cord mesenchymal

stem cell-derived exosomes improve ovarian function and

proliferation of premature ovarian insufficiency by regulating the

hippo signaling pathway. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne).

12(711902)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Qu Q, Liu L, Cui Y, Liu H, Yi J, Bing W,

Liu C, Jiang D and Bi Y: miR-126-3p containing exosomes derived

from human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells promote

angiogenesis and attenuate ovarian granulosa cell apoptosis in a

preclinical rat model of premature ovarian failure. Stem Cell Res

Ther. 13(352)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Burton GJ and Jauniaux E: Oxidative

stress. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 25:287–299.

2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Agarwal A, Aponte-Mellado A, Premkumar BJ,

Shaman A and Gupta S: The effects of oxidative stress on female

reproduction: A review. Reprod Biol Endocrinol.

10(49)2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Wang L, Tang J, Wang L, Tan F, Song H,

Zhou J and Li F: Oxidative stress in oocyte aging and female

reproduction. J Cell Physiol. 236:7966–7983. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Huang Y, Cheng Y, Zhang M, Xia Y, Chen X,

Xian Y, Lin D, Xie S and Guo X: Oxidative stress and inflammatory

markers in ovarian follicular fluid of women with diminished

ovarian reserve during in vitro fertilization. J Ovarian Res.

16(206)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Zhang Q, Zhang D, Liu H, Fu J, Tang L and

Rao M: Associations between a normal-range free thyroxine

concentration and ovarian reserve in infertile women undergoing

treatment via assisted reproductive technology. Reprod Biol

Endocrinol. 22(72)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Can S, Yang X, He Y, Wang C, Zou H, Fan Q,

Xu X, Cai G, Yunxia C and Xiaoqing P: Diminished ovarian reserve

associates with pregnancy and birth outcomes after IVF: A

retrospective cohort study. Hum Fertil (Camb).

27(2414813)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Lin Q, Qi Q, Hou S, Chen Z, Jiang N, Zhang

L and Lin C: Exosomal circular RNA hsa_circ_007293 promotes

proliferation, migration, invasion, and epithelial-mesenchymal

transition of papillary thyroid carcinoma cells through regulation

of the microRNA-653-5p/paired box 6 axis. Bioengineered.

12:10136–10149. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Xiong S, Peng H, Ding X, Wang X, Wang L,

Wu C, Wang S, Xu H and Liu Y: Circular RNA expression profiling and

the potential role of hsa_circ_0089172 in Hashimoto's thyroiditis

via sponging miR125a-3p. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 17:38–48.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Gustavsson EK, Zhang D, Reynolds RH,

Garcia-Ruiz S and Ryten M: ggtranscript: An R package for the

visualization and interpretation of transcript isoforms using

ggplot2. Bioinformatics. 38:3844–3846. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Sherman BT, Hao M, Qiu J, Jiao X, Baseler

MW, Lane HC, Imamichi T and Chang W: DAVID: A web server for

functional enrichment analysis and functional annotation of gene

lists (2021 update). Nucleic Acids Res. 50:W216–W221.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408.

2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Kalich-Philosoph L, Roness H, Carmely A,

Fishel-Bartal M, Ligumsky H, Paglin S, Wolf I, Kanety H, Sredni B

and Meirow D: Cyclophosphamide triggers follicle activation and

‘burnout’; AS101 prevents follicle loss and preserves fertility.

Sci Transl Med. 5(185ra62)2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Mao X, Meng Q, Han J, Shen L, Sui X, Gu Y

and Wu G: Regulation of dynamin-related protein 1 (DRP1) levels

modulates myoblast atrophy induced by C26 colon cancer-conditioned

medium. Transl Cancer Res. 10:3020–3032. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Zhang D, Yi S, Cai B, Wang Z, Chen M,

Zheng Z and Zhou C: Involvement of ferroptosis in the granulosa

cells proliferation of PCOS through the circRHBG/miR-515/SLC7A11

axis. Ann Transl Med. 9(1348)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Sun L, Wang H, Yu S, Zhang L, Jiang J and

Zhou Q: Herceptin induces ferroptosis and mitochondrial dysfunction

in H9c2 cells. Int J Mol Med. 49(17)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Lv Z, Lv Z, Song L, Zhang Q and Zhu S:

Role of lncRNAs in the pathogenic mechanism of human decreased

ovarian reserve. Front Genet. 14(1056061)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Zhou WY, Cai ZR, Liu J, Wang DS, Ju HQ and

Xu RH: Circular RNA: metabolism, functions and interactions with

proteins. Mol Cancer. 19(172)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Patop IL, Wust S and Kadener S: Past,

present, and future of circRNAs. EMBO J. 38(e100836)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Lu G, Zhu YY, Li HX, Yin YL, Shen J and

Shen MH: Effects of acupuncture treatment on microRNAs expression

in ovarian tissues from Tripterygium glycoside-induced diminished

ovarian reserve rats. Front Genet. 13(968711)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Hughes CHK, Smith OE, Meinsohn MC,

Brunelle M, Gevry N and Murphy BD: Steroidogenic factor 1 (SF-1;

Nr5a1) regulates the formation of the ovarian reserve. Proc Natl

Acad Sci USA. 120(e2220849120)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Chiappara G, Di Vincenzo S, Cascio C and

Pace E: Stem cells, Notch-1 signaling, and oxidative stress: A

hellish trio in cancer development and progression within the

airways. Is there a role for natural compounds? Carcinogenesis.

45:621–629. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Feng G, Zhang H, Guo Q, Shen X, Wang S,

Guo Y and Zhong X: NONHSAT098487.2 protects cardiomyocytes from

oxidative stress injury by regulating the Notch pathway. Heliyon.

9(e17388)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Shaoyong W, Jin H, Jiang X, Xu B, Liu Y,

Wang Y and Jin M: Benzo [a] pyrene-loaded aged polystyrene

microplastics promote colonic barrier injury via oxidative

stress-mediated notch signalling. J Hazard Mater.

457(131820)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Zhou Z, Li Y, Ding J, Sun S, Cheng W, Yu

J, Cai Z, Ni Z and Yu C: Chronic unpredictable stress induces

anxiety-like behavior and oxidative stress, leading to diminished

ovarian reserve. Sci Rep. 14(30681)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Zhang B, Zeng M, Zhang Q, Wang R, Jia J,

Cao B, Liu M, Guo P, Zhang Y, Zheng X and Feng W: Ephedrae Herba

polysaccharides inhibit the inflammation of ovalbumin induced

asthma by regulating Th1/Th2 and Th17/Treg cell immune imbalance.

Mol Immunol. 152:14–26. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Buratini J, Dellaqua TT, Dal Canto M, La

Marca A, Carone D, Mignini Renzini M and Webb R: The putative roles

of FSH and AMH in the regulation of oocyte developmental

competence: From fertility prognosis to mechanisms underlying

age-related subfertility. Hum Reprod Update. 28:232–254.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Gilchrist RB, Lane M and Thompson JG:

Oocyte-secreted factors: Regulators of cumulus cell function and

oocyte quality. Hum Reprod Update. 14:159–177. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Jin L, Yang Q, Zhou C, Liu L, Wang H, Hou

M, Wu Y, Shi F, Sheng J and Huang H: Profiles for long non-coding

RNAs in ovarian granulosa cells from women with PCOS with or

without hyperandrogenism. Reprod Biomed Online. 37:613–623.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Levi AJ, Raynault MF, Bergh PA, Drews MR,

Miller BT and Scott RT Jr: Reproductive outcome in patients with

diminished ovarian reserve. Fertil Steril. 76:666–669.

2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Zhang S, Zou X, Feng X, Shi S, Zheng Y, Li

Q and Wu Y: Exosomes derived from hypoxic mesenchymal stem cell

ameliorate premature ovarian insufficiency by reducing

mitochondrial oxidative stress. Sci Rep. 15(8235)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Zhang L, Zhou H, Li J, Wang X, Zhang X,

Shi T and Feng G: Comprehensive Characterization of Circular RNAs

in Neuroblastoma Cell Lines. Technol Cancer Res Treat.

19(1533033820957622)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Khan F, Chen Y, Hartwell HJ, Yan J, Lin

YH, Freedman A, Zhang Z, Zhang Y, Lambe AT, Turpin BJ, et al:

Heterogeneous oxidation products of fine particulate isoprene

Epoxydiol-derived methyltetrol sulfates increase oxidative stress

and inflammatory gene responses in human lung cells. Chem Res

Toxicol. 36:1814–1825. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Li F, Wang Y, Xu M, Hu N, Miao J, Zhao Y

and Wang L: Single-nucleus RNA Sequencing reveals the mechanism of

cigarette smoke exposure on diminished ovarian reserve in mice.

Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 245(114093)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Chen P, Li W, Liu X, Wang Y, Mai H and

Huang R: Circular RNA expression profiles of ovarian granulosa

cells in advanced-age women explain new mechanisms of ovarian

aging. Epigenomics. 14:1029–1038. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Zhu X, Li W, Lu M, Shang J, Zhou J, Lin L,

Liu Y, Xing J, Zhang M, Zhao S, et al: M6A demethylase

FTO-stabilized exosomal circBRCA1 alleviates oxidative

stress-induced granulosa cell damage via the miR-642a-5p/FOXO1

axis. J Nanobiotechnology. 22(367)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Jia C, Wang S, Yin C, Liu L, Zhou L and Ma

Y: Loss of hsa_circ_0118530 inhibits human Granulosa-like tumor

cell line KGN cell injury by sponging miR-136. Gene.

744(144591)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Wang S, Wang Y, Qin Q, Li J, Chen Q, Zhang

Y, Li X and Liu J: Berberine protects against

Dihydrotestosterone-induced human ovarian granulosa cell injury and

ferroptosis by regulating the circ_0097636/MiR-186-5p/SIRT3

pathway. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 196:5265–5282. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Yang C, Li Q, Chen X, Zhang Z, Mou Z, Ye

F, Jin S, Jun X, Tang F and Jiang H: Circular RNA circRGNEF

promotes bladder cancer progression via miR-548/KIF2C axis

regulation. Aging (Albany NY). 12:6865–6879. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Xie F, Huang C, Liu F, Zhang H, Xiao X,

Sun J, Zhang X and Jiang G: CircPTPRA blocks the recognition of RNA

N6-methyladenosine through interacting with IGF2BP1 to

suppress bladder cancer progression. Mol Cancer.

20(68)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

58

|

She J, Tuerhongjiang G, Guo M, Liu J, Hao

X, Guo L, Liu N, Xi W, Zheng T, Du B, et al: Statins aggravate

insulin resistance through reduced blood glucagon-like peptide-1

levels in a microbiota-dependent manner. Cell Metab. 36:408–421.e5.

2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

59

|

Ferriere A and Tabarin A: Cushing's

syndrome: Treatment and new therapeutic approaches. Best Pract Res

Clin Endocrinol Metab. 34(101381)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

60

|

Auer MK, Nordenstrom A, Lajic S and Reisch

N: Congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Lancet. 401:227–244.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

61

|

Macut D, Ilic D, Mitrovic Jovanovic A and

Bjekic-Macut J: Androgen-Secreting ovarian tumors. Front Horm Res.

53:100–107. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|