1. Introduction

Inflammation is a condition that has been a burden

for decades. Research on the pathophysiology of inflammation has

been gradually deepening over the recent decades (1,2).

However, for certain chronic refractory inflammations, such as

Crohn's disease, difficult-to-treat rheumatoid arthritis, severe

asthma, atopic dermatitis or cutaneous lupus (3-6),

no suitable cure has been found. At present, there are various

treatments for persistent inflammation, including immunotherapy to

restore normal lymphocyte count by using granulocyte-macrophage

colony-stimulating factor and granulocyte-colony-stimulating factor

pair, anti-inflammatory and antioxidant therapy, anabolic and

anti-catabolic therapy and nutritional support therapy (7). For chronic inflammation of the

respiratory system, especially chronic obstructive pulmonary

disease (COPD), the current use of home oxygen therapy,

expectorants, long-acting bronchodilators, such as long-acting

muscarinic antagonists or long-acting β2-agonists,

antibiotics, influenza and pneumococcal vaccines, can only relieve

the clinical symptoms of patients and prevent the further

aggravation of the disease (8).

Similarly, the current treatment strategy for asthma, a common

chronic non-communicable respiratory disease, is limited to

controlling asthma symptoms and reducing the risk of recurrence

(9).

By contrast, cancer has become a major public health

issue in the 21st century, accounting for 25% of the global

mortality cases from non-communicable diseases, according to a 2022

Global Cancer Statistics report (10). With the continuous exploration of

cancer treatment, various ILs have been previously shown to serve a

critical role in the development of cancer, including IL-2, IL-6,

IL-10, IL-12 and IL-35 (11-15).

Amongst them, tumors frequently jointly produce IL-8, a chemotactic

factor, which serves different roles in promoting tumor processes,

such as angiogenesis and survival signal transduction in cancer

stem cells (16,17).

Evidence have been accumulating that gradually

deepened the knowledge into the various cytokine signaling

pathways, which has led to the development of a series of small

molecule antagonists and small molecule inhibitors targeting such

signaling pathways. For inflammation and cancers, IL-1R1

(MEDI8968), IL-5 (mepolizumab) or IL-5R (benralizumab), IL-8

(ABX-IL8), IL-18 (MEDI2338), IL-33 (MEDI3506) have been developed

for the treatment of COPD (18),

whereas AZD5069 is in the clinical development stage of cancer such

as triple-negative breast cancer (18,19).

In addition, AZD8039, danirixin (GSK1325756), ladarixin (DF2156A),

reparixin and SB656933(20), which

are more effective compared with traditional treatments for acute

respiratory distress syndrome, COVID-19 pneumonia, inflammatory

bowel disease (IBD), liver cancer and lung cancer have been

garnering interest.

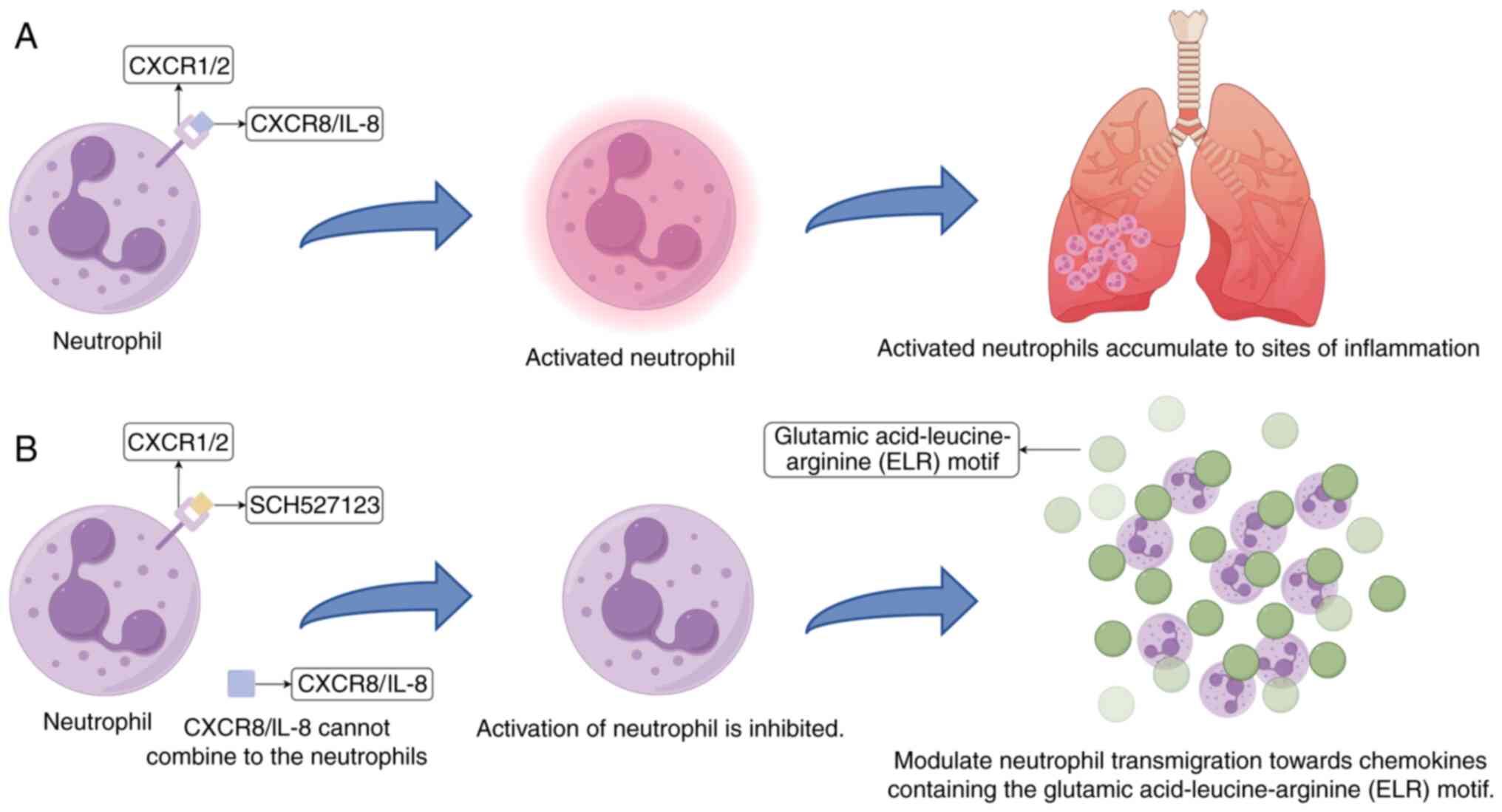

At present, a novel and selective C-X-C motif

chemokine receptor (CXCR)1/2 antagonist that can exert therapeutic

effects against both inflammation and cancers, SCH527123, which can

inhibit the binding (or activation) of chemokines to CXCR1/2 in a

high-affinity manner, has been discovered (21,22).

It can inhibit signal transduction, neutrophil chemotaxis and

myeloperoxidase release (23,24).

It may have clinical value for the treatment of diseases such as

acquired immune deficiency syndrome, IBD and non-small cell lung

cancer directly (or indirectly) mediated by CXCR1/2-expressing

cells (25,26).

To the best of our knowledge, the present review is

the earliest of SCH527123 in the field of inflammation and cancer

treatment. It aims to discuss the history of the development of

SCH527123 and its mechanism of action, whilst summarizing the

application and achievements of SCH527123 in asthma, COPD,

pancreatic cancer and liver cancer and animal models (namely in

mice and rabbits) over recent years. In addition, limitations of

SCH5271213 development are discussed, where the clinical value of

SCH527123 in the treatment of diseases in the future was also

explored, to lay a foundation for future research.

2. C-X-C motif chemokine ligand (CXCL)8/IL-8

is involved in inflammation and tumorigenesis

IL-8 is a basic protein containing four cysteine

residues and two intramolecular disulfide bonds which stabilize the

structure of IL-8, that has strong resistance to deformation

processing, such as plasma peptidase, high temperature and

acid-base environment (27-31).

In addition, IL-8 is a neutrophil chemotactic polypeptide (32). In in vitro experiments, IL-8

has shown chemotactic activity to T lymphocytes, basophils and

neutrophils Although it can promote the migration of T cells and

neutrophils, it requires additional factors to do so (33).

A study performed in 1989 injected IL-8 into the

skin of rabbits and observed the accumulation of neutrophils and

formation of neutrophil-dependent edema in the rabbit skin

(34). Subsequently, 2 years

later, clinical trials demonstrated for the first time the presence

of bioactive substances such as melanoma growth stimulatory

activity, P-thromboglobulin and platelet factor 4 in the synovial

fluid of patients with rheumatoid arthritis and the expression of

IL-8 mRNA in synovial cells (35).

The level of IL-8 detected in patients with metastatic melanoma,

among 56 confirmed cases, showed that some had markedly elevated

serum IL-8 which correlated with tumour load but was independent of

the site of metastasis (36). This

clinical observation is supported by mechanistic studies summarized

by Waugh and Wilson (37), who

described how IL-8, through its receptors CXCR1 and CXCR2, promotes

melanoma cell migration and invasion. Additionally, IL-8

contributes to an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment by

recruiting myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) and inhibiting

lymphocytic infiltration, which together facilitate tumor

progression and metastasis (37).

Using cell culture, IL-8 has also been found to be involved in

airway mucosal tumor progression (38). These aforementioned experimental

data all suggest the important role of IL-8 in inflammation and

tumor development. The following sections of the present review

will discuss the role of IL-8 in inflammation and tumor

development.

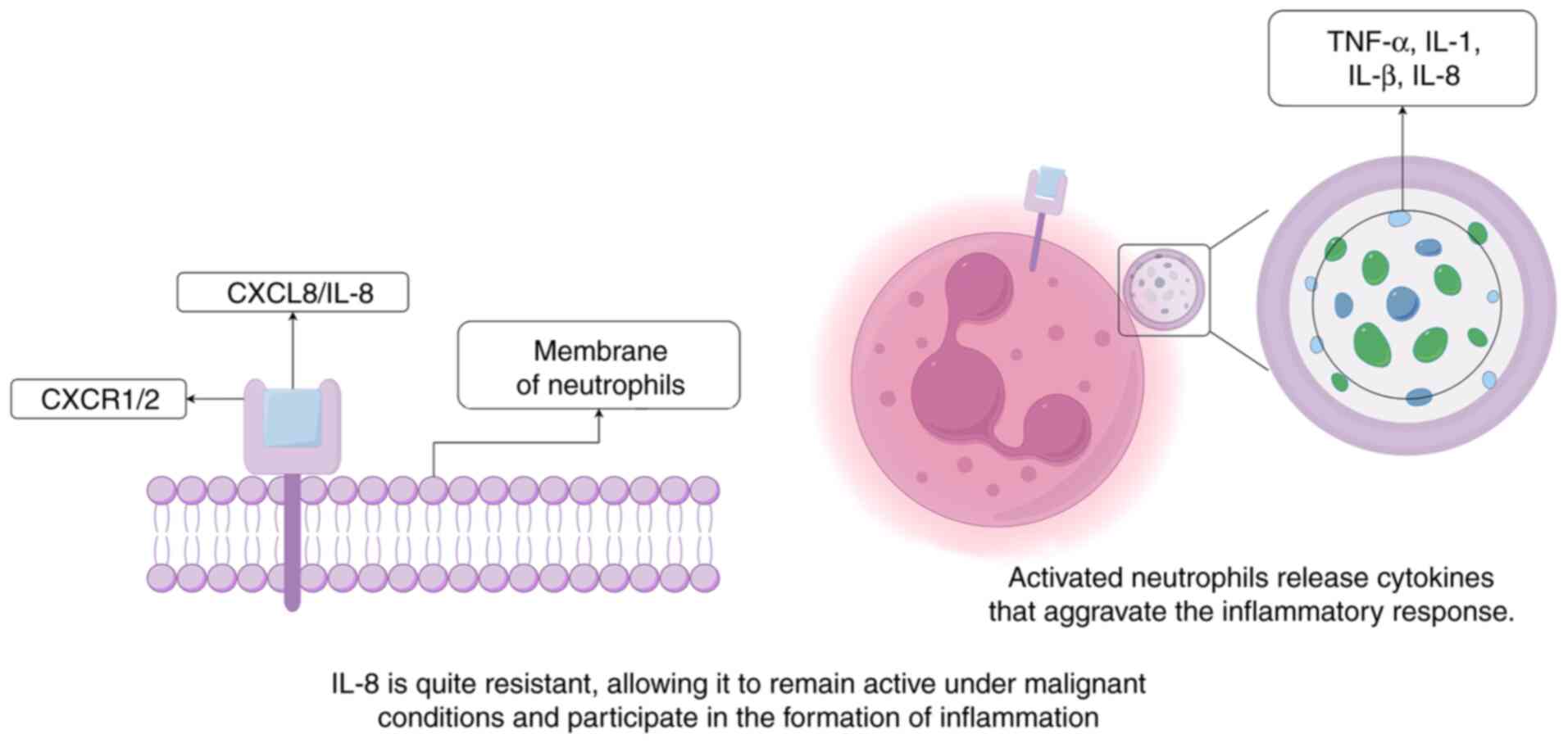

Inflammation is the typical bodily response to

injury, resulting from various causes, such as physical injury,

ischemia-reperfusion injury, infection, toxin exposure, malignant

tumors and autoimmune reactions, all of which would otherwise lead

to tissue damage (39). The

capacity of IL-8 to attract and activate neutrophils has rendered

it a key inflammatory mediator from the initial stages of this

process (33,40). IL-8 can bind to the CXCR2 receptor

on the surface of neutrophils, leading to chemotaxis and the

activation of neutrophils, causing them to secrete various

cytokines, such as TNF-α, IL-1α, IL-1β and IL-8, exacerbating the

occurrence of inflammation (Fig.

1) (41). IL-8 is relatively

resistant to temperature, protein hydrolysis and acidic

environments. These resistances enable IL-8 to maintain its

activity under malignant conditions, making it a main molecule at

sites of acute inflammation (40).

Furthermore, IL-8 is frequently produced early in inflammation and

can remain active at the site of inflammation for extended periods,

up to several weeks. In acute inflammatory responses, such as

bacterial infections or tissue injury, IL-8 activity generally

lasts several weeks, whereas in chronic conditions, such as

rheumatoid arthritis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD),

or certain cancers, it may remain elevated for several months. This

is in contrast to the majority of the other inflammatory cytokines,

such as TNF-α, IL-1β and interleukin-6 (IL-6), which will typically

disappear from the site of inflammation within a few hours in the

body (42). The prolonged activity

of IL-8 may be closely associated with its important role in the

occurrence of inflammation.

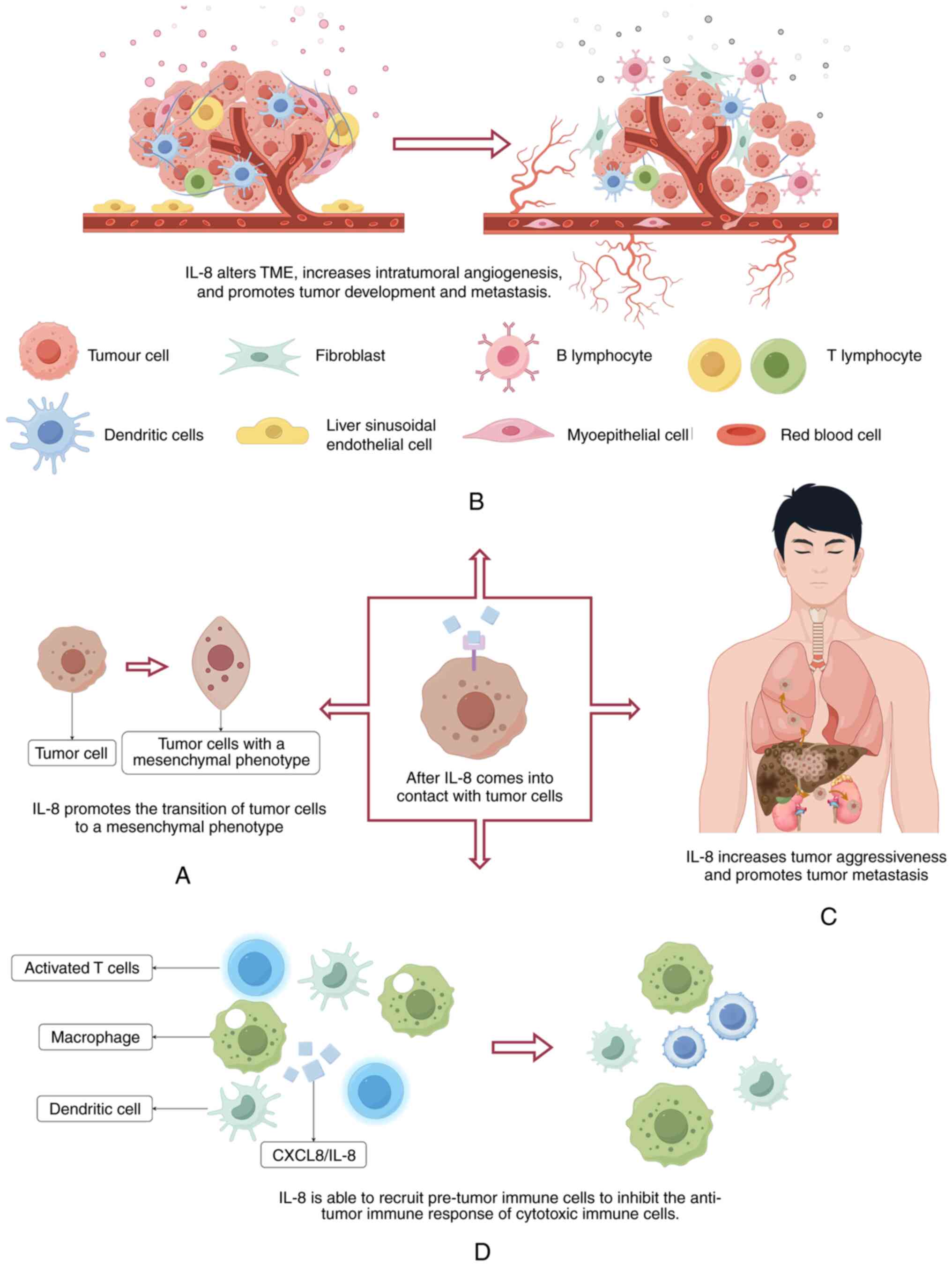

IL-8 has been shown to be associated with the

physiology of various cancers, including melanoma, prostate, colon,

pancreatic, breast and lung cancer (43). IL-8 can directly impact tumors by

altering the characteristics of tumor cells, inducing the

transition of tumor cells to a more mesenchymal phenotype,

consequently promoting migration and proliferation (44). This in turn also promotes the

occurrence of metastasis in vivo (45). By recruiting additional

infiltrating immunosuppressive cells, IL-8 increases angiogenesis

within tumors and alters the immune microenvironment, which further

promotes tumor growth and metastasis (46). The formation of tumors requires the

support of the surrounding normal matrix, which is referred to as

the tumor microenvironment (TME). IL-8 can not only influence the

cellular phenotypes of tumors and endothelial cells within the TME,

but can also alter the immune composition at the tumor site. IL-8

preferentially recruits pre-tumor immune cells (including

myeloid-derived suppressor cells, tumor-associated macrophages,

tumor-associated neutrophils and Natural Killer cells), thereby

suppressing the anti-tumor immune response of cytotoxic immune

cells (16). IL-8 gene

silencing has been shown to suppress the growth of ovarian cancer

through an anti-angiogenic mechanism (Fig. 2) (47). The aforementioned factors all

indicate that IL-8 serves a promotional role in the process of

tumorigenesis.

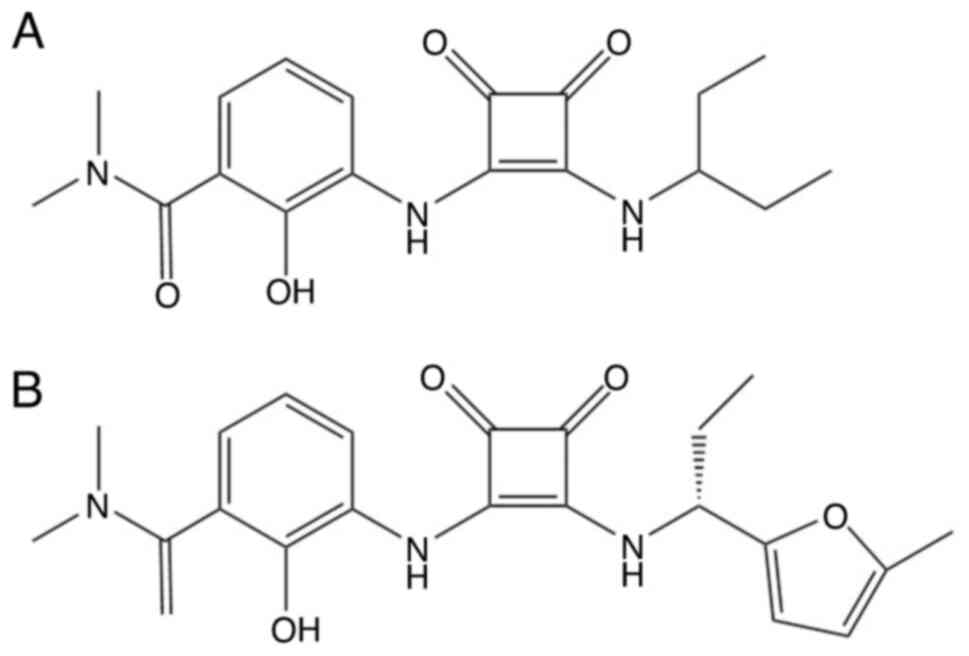

3. Mechanism of action for SCH527123

Since IL-8 and related chemokines (such as CCL2,

CXCL12, CCL5 and CX3CL1) have shown strong association in a variety

of inflammatory conditions and cancers, the research discovery of

small molecule antagonists of CXCR1/2 as novel targets has been

garnering attention. In 1998, the first potent and selective CXCR2

receptor antagonist SB225002 was reported (48). Subsequently, in 2003, PD0220245 was

demonstrated to be the most effective IL-8 antagonist at the time,

where compared with SB225002, PD0220245 was able to inhibit both

CXCR1 and CXCR2 as a dual inhibitor (49). In 2006, Dwyer et al

(50) discovered that the

furan-based derivative of lead (Fig.

3A) was part of the active structure of lead cyclobutene dione,

leading to the development of SCH527123 (Fig. 3B). This is a type of selective

CXCR1/2 antagonist, also known as navarixin (20). CXCL8/IL-8 has been demonstrated to

induce the migration of neutrophils (51), which meant that CXCL8/IL-8 can

induce the recruitment of neutrophils to inflammatory sites by

interacting with CXCR1/2 expressed on the surfaces of these cells

(52). SCH527123 acts as a CXCR1/2

antagonist by blocking the binding of ELR-motif chemokines to

CXCR2, thereby inhibiting downstream signaling pathways (AKT, ERK,

STAT3 and S6 phosphorylation). This suppresses neutrophil

activation and migration toward chemokines, while also reducing

tumor cell proliferation and survival, resulting in comprehensive

modulation of immune cell function and tumor progression. These

chemokines include IL-8, growth homolog (Gro)-α, epithelial

cell-derived neutrophil attractant-78 and neutrophil-activating

peptide-2(53). SCH527123 can

directly block the binding of CXCL8/IL-8 to CXCR1/2, thereby

interrupting the subsequent series of harmful reactions that

CXCL8/IL-8 would otherwise trigger in the human body (Fig. 4). Although SCH527123 can bind to

CXCR1 and CXCR2, SCH527123 binds to CXCR1 with lower affinity

(Kd=3.9±0.3 nM), such that the compound is more

CXCR2-selective (Kd=0.049±0.004 nM). Therefore,

SCH527123 has a CXCR2-specific antagonistic effect, which also

suggests its potential therapeutic effect on inflammation.

4. Role of SCH527123 in relevant

diseases

SCH527123 is a novel small molecule antagonist that

serves as an effective allosteric inhibitor for both CXCR1 and

CXCR2, exhibiting high affinity towards both receptors (albeit with

a higher selectivity for CXCR2). It exerts its therapeutic effects

by suppressing the chemotactic activity of all chemokines on

CXCR1/2, thereby alleviating or treating diseases (25).

Asthma

Asthma is caused by chronic inflammation in the

lower respiratory tract. It is a relatively common disease and a

2024 analysis based on the Global Burden of Disease Study found

asthma prevalence rates of 9.1% in children, 11.0% in adolescents,

and 6.6% in adults worldwide. Variations across regions highlight

asthma as a common and significant public health concern (54). The main symptoms of asthma are

breathing difficulties, shortness of breath, cough and chest

tightness (54). During severe

asthma, neutrophils and eosinophils can be found in the lung

epithelium and mucus. The expression of ELR+ chemokine and its

receptor was found to be increased (ELR+ chemokines, including IL-8

and CXCL1-3) (55), where CXCR1/2

was observed to be expressed on airway smooth muscle cells and

mediated cell contraction and migration to enhance airway

responsiveness and remodeling, causing bronchoconstriction.

IL-8/CXCR2-dependent neutrophil recruitment is critical for the

development of asthma, where blocking this signaling pathway may

provide a novel approach for its treatment (56).

In 1996, a clinical trial on patients with asthma

with a mean age of 39 years found that their bronchoalveolar lavage

fluid contained higher levels of IL-8 compared with those from

healthy individuals, suggesting that non-specific inflammation may

be occurring in the airway (57).

Neutrophils are recruited to the lungs in response to various

chemokines, such as IL-8, GRO-α, MIP-2 and MIP-1 α, which then

accumulate in the airways of patients with asthma (58). The biological effects of IL-8 are

mediated through chemokine receptors CXCR1 and CXCR2(59). In 2012, a number of clinical

studies have reported that blocking CXCR1/2 was safe and

well-tolerated, which could reduce the numbers of sputum

neutrophils in patients with severe asthma (58). In 2016, 19 non-smoking patients

with mild allergic asthma were included in a clinical study. This

previous study demonstrated that CXCLs, including IL-8 and their

receptors CXCR1 and CXCR2, are upregulated in the airways during

asthma exacerbations (60).

Therefore, inhibiting neutrophil chemotaxis by blocking CXCR1 and

CXCR2 may provide an alternative therapeutic strategy for patients

with asthma complicated with neutrophilic inflammation. By

targeting cells that accumulate in airway tissues through

chemotaxis mediated by CXCR1 and CXCR2, the 2016 study conducted by

Todd et al (61) showed

that SCH527123 has emerged as a novel therapeutic agent that may

exert a specific therapeutic effect on inflammation.

COPD

COPD is an insidious but progressive chronic

inflammatory disease of the respiratory system, characterized by an

obstructive ventilation pattern, manifested as incompletely

reversible airflow limitation. In severe cases, it can lead to

chronic respiratory failure (53,62).

Due to the inhalation of harmful particles and gases (such as

chemicals in cigarette smoke) or aberrant innate immune responses,

epithelial cells and resident macrophages can become activated.

These cells in turn release cytokines and chemokines, thereby

recruiting neutrophils to the lungs. The number of activated

macrophages and neutrophils in the lungs then increases, where the

proteases they secrete causes alveolar damage, leading to the

spread of inflammation during COPD (53,63).

CXCR1/2 serves an important role in the chemotaxis

of neutrophils. By studying eight patients with COPD and eight

smokers without COPD, IL-8 was demonstrated to serve a major role

in neutrophil chemotaxis induced by alveolar macrophage-derived

conditioned medium, where blockade of CXCR1 and CXCR2 was observed

to inhibit this chemotaxis. Furthermore, the dual CXCR1/2

antagonist SCH527123 exerted a superior inhibitory effect on

neutrophils compared with that mediated by the single CXCR2

antagonist SB656933, whilst also demonstrating a greater role in

blocking the chemotaxis of IL-8(63). Another study conducted a

single-point, randomized, double-blind, multi-dose,

placebo-controlled, three-way cross-over study on healthy

non-smoking volunteers with normal airway reactivity, which found

that SCH527123 could inhibit the migration of neutrophils to CXCLs,

thereby reducing the number of neutrophils in the sputum of healthy

non-smoking volunteers exposed to ozone (53). Various stimuli, such as cigarette

smoke, air pollution and ozone, can activate lung macrophages,

leading to the secretion of several cell factors, such as IL-8,

TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, CCL2 and GM-CSF, which causes an inflammatory

response and the aggregation of neutrophils at the site of

inflation. Subsequently, the various enzymes released by

neutrophils and the mucus produced by hypertrophic goblet cells can

also contribute to the progression of COPD (64-67).

Therefore, controlling the number of neutrophils using medications

appears to be key to treating COPD. Therefore, it can be

hypothesized that SCH527123 can be a treatment option for COPD,

where its ability to reduce the number of neutrophils may serve a

role in the disease treatment process.

5. CXCL8/IL-8 and SCH527123 in cancers

Accumulating evidence has indicated that TME serves

a key role in promoting cancer progression and regulating the

response to standard treatments (68,69).

Various components can coexist and interact within the TME,

including tumor-associated macrophages, CD4+ and CD8+ T cells,

dendritic cells, natural killer cells, tumor-associated endothelial

cells, the abnormal tumor vasculature, cancer-associated

fibroblasts and myeloid-derived suppressor cells (70). The presence of inflammatory cells

and immune regulatory mediators in the TME polarizes the host

immune response towards specific phenotypes that affect the

progression of tumors (71).

Various studies have previously found that CXCLs are expressed at

increased levels through both autocrine and paracrine pathways in

different types of tumors, suggesting their involvement in tumor

growth and metastasis (72,73).

CXCR2 chemokine ligands, including CXCL1-8, have all been known to

be secreted and expressed in various types of cancers, including

solid tumors, such as melanoma, breast, lung, bladder, pancreatic,

liver, prostate and colorectal cancer, in addition to hematological

malignancies (43). This section

primarily focused on liver, pancreatic, ovarian and colon cancer,

as the CXCL/CXCR2 signaling pathway is highly active in these

tumors and closely linked to inflammatory tumor microenvironment,

tumor growth and metastasis. Moreover, these types of cancer are

clinically common with poor prognosis, making them ideal targets

for evaluating the potential efficacy of the CXCR2 antagonist

SCH527123 (Table I).

| Table ISummary of the role of SCH527123 in

various cancers. |

Table I

Summary of the role of SCH527123 in

various cancers.

| First author/s,

year | Disease | Experimental

result | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Goral et al,

2015 | Liver cancer | CXCR1, CXCR2 and

IL-8 proteins were highly expressed in the cytoplasm of

hepatocellular carcinoma cells, where IL-8 induced the expression

of CXCR1/2. | (82) |

| Fu et al,

2018 | Pancreatic

cancer | SCH527123 can

inhibit the proliferation of PDAC cells by reducing the activity of

cancer cells, inhibiting cancer cell proliferation and blocking

signaling pathways, including the IL-8/CXCR1/2 signaling

pathway. | (26) |

| Ning et al,

2012 | | SCH527123 was found

to inhibit tumor growth in a mouse subcutaneous xenograft

model. | (87) |

| Fu et al,

2018 | | The combination of

SCH527123 and bazedoxifene showed a potent inhibitory effect on

PDAC cells. | (88) |

| Zhang et al,

2022 | Ovarian cancer | Bazedoxifene

hydrochloride and SCH527123 were used to inhibit the proliferation

of ovarian cancer cells in mice by blocking the IL-6 and IL-8

pathways. | (93) |

| Singh et al,

2011 | | IL-8 gene

silencing can inhibit the invasion of tumor cells. | (98) |

| Singh et al,

2011 | | Silencing

CXCR1/2 regulated endothelial cell growth, migration,

survival and new vessel formation, in addition to ERK1/2

phosphorylation by using shRNA. | (98) |

| Varney et

al, 2011 | Colon cancer | Oral administration

of SCH527123 inhibited CXCR1/2 signaling, malignant cell survival

and new vessel formation to inhibit liver metastasis by human colon

cancer in a mouse model. | (80) |

| Ning et al,

2012 | | IL-8/CXCR2 pathway

is the key to the development of colon cancer. SCH527123 has

anti-tumor effect through NF-κB/AKT/MAPK signaling pathway. | (87) |

Liver cancer

Liver cancer is one of the most common fatal cancers

worldwide. HCC ranks as the 6th most common cancer and the 3rd

leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide (74). Even after curative surgical

resection, hepatocellular carcinoma patients have a 5-year overall

survival rate of 30-50% and a median survival of 60 months. This

reflects high recurrence risk and poor long-term prognosis

post-resection, highlighting the malignancy's aggressiveness and

therapeutic challenges (75).

There are various risk factors for liver cancer, including

hepatitis virus infection, fatty liver disease, alcohol-related

cirrhosis, smoking, obesity, diabetes, iron overload and various

dietary exposures (aflatoxins, high-fat diet, red and processed

meats and alcohol consumption) (76). A definitive diagnosis is typically

made when patients are already in the advanced stages of the

disease, where due to the high frequency of recurrence and distant

metastasis after surgical excision, prognosis is poor (76,77).

Previous studies have discovered that the expression of IL-8 is

upregulated and involved in the progression of various human

cancers, including liver cancer (78,79).

In in vitro cultured human liver cells, IL-8 has been shown

to serve a role in promoting cell migration and/or invasion

(77). Therefore, inhibiting the

function of IL-8 may suppress liver cancer malignancy.

Although there is no direct in vivo evidence

that CXCR1 and CXCR2 are expressed in liver cancer, according to an

analysis of immunohistochemical results in China (78) by Bi et al (77), IL-8, CXCR1 and CXCR2 levels were

elevated in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of liver cancer

patients and immunohistochemistry showed higher CXCR1 and CXCR2

expression in tumor tissues compared with adjacent non-cancerous

tissues. CXCR1/CXCR2 expression correlated with clinical stage and

metastasis. In vitro, IL-8 promoted liver cancer cell

migration and invasion, which was attenuated by CXCR1/CXCR2

blockade. These findings indicate that high IL-8 secretion induces

CXCR1 and CXCR2 overexpression on both tumor and inflammatory

cells, contributing to liver cancer progression. This can further

confirm that the high level of IL-8 secretion by liver cancer cells

induces the overexpression of CXCR1 and CXCR2 on both liver cancer

and inflammatory cells, which in turn participate in the

occurrence, invasion and metastasis of liver cancer (77). The study by Bi et al

(77) provides experimental

evidence that IL-8 promotes liver cancer cell migration via CXCR1

and CXCR2. Immunohistochemical and RT-qPCR analyses showed that

IL-8, CXCR1, and CXCR2 were significantly upregulated in liver

cancer tissues compared with normal liver tissues, with IL-8 mRNA

expression positively correlated with CXCR1 (r=0.618, P<0.01)

and CXCR2 (r=0.569, P<0.01). In vitro, treatment of Huh-7

and HepG2 cells with 50 ng/ml IL-8 for 24 h increased wound closure

from 35-78 and 32-72%, respectively in wound healing assays, and

significantly enhanced Transwell migration and invasion

(P<0.01). Pre-treatment with 5 µM CXCR1 or CXCR2 antagonists for

30 min reduced IL-8-induced migration by ~60% (P<0.01),

indicating that the effect is mediated through these receptors.

These results demonstrate that IL-8 facilitates liver cancer cell

migration and invasion in a CXCR1/2-dependent manner. SCH527123 can

inhibit the binding of IL-8 with CXCR1 and CXCR2, thereby

suppressing the chemotactic migration and angiogenic response of

malignant human colon cancer cells (80), slowing down or preventing the

progression of liver cancer, which has development potential for

treating liver cancer or extending the survival cycle of patients

with advanced liver cancer.

Pancreatic cancer (PC)

PC is a deadly cancer among the most insidious

cancers at early stages; typically asymptomatic and hard to detect

early, leading to late diagnosis and poor outcomes, with 90% cases

being of the ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) subtype (81). Because the pancreas is located in

the retroperitoneum (82) and its

deep position, its malignancies cannot be readily found during the

early stages clinically, where a variety of inherent factors (such

as age, sex, environment, blood type and family history) and

lifestyle factors (such as smoking, drinking, eating habits and

obesity) have all been reported to be risk factors for PC (83). All of these factors further

exacerbate the already high mortality rate of PC. The traditional

treatment method of PC includes surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy

and palliative treatment (84).

Over the previous decade, research on the immunotherapy of this

cancer has been gradually expanding (82).

Although the etiology of PC remains unclear,

accumulating evidence has shown that IL-8 and its receptors CXCR1

and CXCR2 are involved in various tumor initiation and

developmental stages (85,86). Inhibition of the CXCR1/2 signaling

pathway has been reported to reduce the activation of downstream

effectors AKT, ERK, STAT3 and S6, inhibiting the proliferation of

PDAC cells (27). SCH527123 has

also been shown to inhibit tumor growth in a xenograft model

(87). Fu and Lin (88) previously found a potent inhibitory

effect of SCH527123 in combination with bazedoxifene on PDAC cells

(88). Taken together, these

results suggest that SCH527123 may serve be a novel targeted

therapy drug that can be used for the treatment of PC

clinically.

Ovarian cancer

Ovarian cancer has one of the poorest survival rates

of all cancers of the female reproductive system (89), which also ranks as the seventh most

common female cancer in the world, 10th in China (90). Between 1990 and 2019, the incidence

of ovarian cancer in China increased by an average of 2.03%

annually and the mortality rate by 1.58% annually. This

three-decade data change shows the growing disease burden of

ovarian cancer in China, with rising new cases and deaths

continuously threatening women's health (90). A number of factors, such as older

age, genetic factors, family history, history of other cancers,

smoking and high fat diet, are risk factors of ovarian cancer

(91). Despite the recognition of

ovarian cancer, treatment and survival trends have not changed

significantly, because the means of early diagnosis are not

accurate, where >50% patients are diagnosed already at advanced

stages. In addition, ~75% patients will relapse due to intrinsic

and acquired chemotherapy resistance, contributing to cancer

recurrence. These are the two main reasons for the low 5-year

overall survival rate (92).

Therefore, the development of targeted therapy with a precise site

of action and few side effects is crucial for the treatment of

ovarian cancer.

Previous mouse experiments have used bazedoxifene

hydrochloride and SCH527123 combined to block IL-6 and IL-8

pathways to inhibit ovarian cancer cell proliferation (93,94).

It has also been previously found that targeted therapy with IL-8

siRNA-1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine combined with

chemotherapy effectively reduced tumor growth in both

chemotherapy-sensitive and chemotherapy-resistant ovarian cancer

models, by observing human ovarian cancer section specimens and

female athymic mouse orthotopic cancer models (48,95,96).

To the best of our knowledge, no study has reported targeting IL-8

as a treatment strategy for ovarian cancer, but it has been

previously found that silencing the IL-8 gene can inhibit

ovarian tumor cell invasion (97).

Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that silencing CXCR1

or CXCR2 can modulate endothelial cell proliferation,

migration, survival and new vessel formation, in addition to ERK1/2

phosphorylation (98). Silencing

CXCR1 or CXCR2 has been shown to modulate endothelial

cell proliferation, migration, survival, and angiogenesis through

pathways including ERK1/2 phosphorylation. CXCL1 and CXCL2, as

ligands of CXCR2, further regulate endothelial cell proliferation

by activating ERK1/2 and PI3K/AKT signaling, promoting cell cycle

progression and survival (99). In

ovarian cancer, the IL-8/CXCR1/2 axis plays a critical role in

tumor progression by promoting tumor-associated angiogenesis, which

supplies nutrients and oxygen to support tumor growth. Activation

of this pathway also enhances tumor cell migration and invasion,

facilitating metastasis, particularly within the peritoneal cavity.

Furthermore, CXCR1/2 signaling contributes to chemoresistance and

shapes an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment by recruiting

myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Therefore, targeting CXCR1/2 not

only inhibits neovascularization but also suppresses ovarian cancer

cell survival and invasiveness, highlighting its potential as a

therapeutic strategy (95,100,101). Therefore, it can be speculated

that blocking the binding of IL-8 to CXCR1/2 using SCH527123 can

inhibit the proliferation of ovarian cancer cells, which has

prospects for the control of invasion and metastasis of ovarian

cancer cells clinically.

Colon cancer

Colorectal cancer is a leading cause of mortality

from gastrointestinal malignancies and the third most commonly

diagnosed cancer, of which >50% patients succumb due to its

associated complications (102).

Modifiable risk factors with clear environmental components include

the lack of activity, sedentary behavior, obesity, smoking, alcohol

consumption, excessive intake of red meat and processed meat. In

addition, hereditary colorectal cancer syndrome, inflammatory bowel

disease and history of colorectal adenoma are also reported risk

factors for colon cancer (103).

SCH527123 was previously reported to inhibit colon

cancer cell survival and new blood vessel formation by inhibiting

CXCR2 and possibly CXCR1 signaling. This in turn inhibited liver

metastasis by human colon cancer cells in a mouse model (77). It has also been demonstrated that

the IL-8/CXCR2 pathway can serve a key role in mediating the

development of colorectal cancer. Specifically, it was found that

SCH527123 can inhibit cancer cell proliferation, motility and

angiogenesis through NF-κB/AKT/MAPK signaling pathway (87). Oxaliplatin is used as an adjuvant

therapy for colon cancer (104).

When it is combined with SCH527123, the NF-κB/AKT/MAPK signal

transduction pathway was found to be further inhibited (87). Based on the results of the

aforementioned previous studies, CXCR2 may be a novel therapeutic

target for colon cancer, where SCH527123 as an antagonist of CXCR2

pathway may provide an idea for the subsequent drug treatment of

colon cancer.

6. Discussion

In the context of increasing refractory inflammation

and rising tumors incidence, in the present review, the

relationship between IL-8, CXCR1/CXCR2 and inflammation and cancers

were discussed, with focus on the CXCR1 and CXCR2 antagonist

SCH527123 to illustrate its possible application for the treatment

of inflammatory diseases and tumors.

Starting in 2007, cytological experiments were

implemented on a cellular level to report that SCH527123 represents

a novel and specific CXCR2 antagonist, with clinical potential in a

variety of inflammatory diseases (21,25,53,62).

In subsequent animal experiments, inhibition of CXCR1- and

CXCR2-mediated chemotaxis by SCH527123 has been observed in rodents

and cynomolgus monkey models, where it was speculated that

SCH527123 may prove beneficial in the treatment of inflammatory

lung diseases, by monitoring bronchoalveolar lavage mucin content

in cynomolgus monkeys (21). To

further confirm the clinical safety of SCH527123 in the human body,

two clinical trials were conducted in 2007 and 2012, which also

yielded certain clinical curative effects (53,58).

In a 2007 trial, oral SCH527123 significantly reduced ozone-induced

airway neutrophilia in healthy subjects, demonstrating good

tolerability and inhibition of neutrophil recruitment (53). In a 2012 multicenter study in

patients with severe refractory asthma, it reduced exacerbation

rates, improved lung function, and decreased airway neutrophil

levels, indicating potential clinical value in chronic inflammatory

diseases (58). In 2011, gene

silencing experiments found that by silencing the CXCR1/2

gene in human microvascular endothelial cells (HMEC-1)

significantly inhibited IL-8-dependent proliferation, survival,

migration and angiogenesis, and attenuated ERK phosphorylation and

cytoskeletal reorganization; these findings suggest that targeting

CXCR1/2 may offer a novel anti-angiogenic strategy for cancer

treatment (98). In 2018, a

cytological experiment inhibiting the IL-6/IL-8 pathway achieved

inhibitory effects on triple-negative breast cancer and PDAC. In

particular, it also showed that SCH527123 was more effective in

inhibiting the progression of triple-negative breast cancer and

PDAC when combined with bazedoxifene or rempacine (88). In addition, when combined with

bazedoxifene hydrochloride, SCH527123 was found to block the IL-6

and IL-8 pathways and inhibited ovarian cancer cell proliferation

in a mouse model (93).

As information on SCH527123 accumulates further,

clinical trials are becoming a possibility to assess the role of

SCH527123 for disease treatment. In 2016, a randomized,

double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter crossover trial

involving 19 non-smoking subjects with mild atopic asthma was

performed (60). For patients with

mild asthma, SCH5271213 was found to effectively reduce the number

of blood neutrophils migrating to the airway, thereby relieving

symptoms without causing adverse effects on bone marrow cells

(60). In 2017, another clinical

trial used SCH527123 in 58 patients with acute exacerbations of

chronic liver failure (ACLF), which found that blocking CXCR1/2

could significantly suppress hepatocyte cell death, which may

alleviate ACLF (23). It has also

been observed that the CXCR1/2 antagonist SCH527123 can inhibit

melanoma, lung, breast, pancreatic and liver tumor cell

proliferation and metastasis (22-24,105-107),

in addition to inhibiting chemotaxis of neutrophils to control the

development of COPD and asthma (Table

I) (58,62).

However, there are also limitations to the clinical

application of SCH527123 at present. SCH527123 research is

relatively mature only at the preclinical stages. Clinical trials

have only begun over the past decade, where the focus has been

mainly on tumors and chronic refractory diseases in the respiratory

system. The role of SCH527123 in inflammation in other organs has

not been tested. In addition, its safety for the treatment of

chronic refractory inflammation and tumors remains to be proven,

such that the biosafety of SCH527123 will become a major testing

avenue for future clinical studies. It has been previously reported

that SCH527123 is generally well-tolerated, where neutropenia is

the most common adverse event, with an incidence rate of 9%

(58). Although SCH527123 has

conferred inhibitory effects on the metastasis of colon cancer and

melanoma cells, neutrophils also serve a dual role in tumor immune

surveillance (108). Therefore,

its long-term use may weaken anti-tumor immunity.

7. Conclusion

Although research on SCH527123 has only been limited

to pre-clinical trials, the existing experimental data suggest that

SCH527123 is more reliable compared with other small molecule

antagonists. Oral administration of SCH527123 is generally safe and

well tolerated, with few adverse reactions. SCH527123 has shown

advantages in combating inflammation and inhibiting tumor growth,

especially with particular potential for the treatment of

refractory inflammation and cancers. However, current experimental

evidence is not sufficient to support the large-scale clinical use

of SCH527123, though it provides a ideas for clinical treatment of

inflammation and cancers. In the future, with the continuous

development of novel therapeutic strategies, SCH527123 is expected

to bring hope to patients.

Acknowledgements

The authors express their sincere gratitude to

Figdraw 2.0 (https://www.figdraw.com) for

providing the drawing platform.

Funding

Funding: The present review was supported by Scientific Research

Project of Luzhou Medical Association (grant no.

2024-YXXM-071).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

JMZ and JWH made major contribution to manuscript

writing and figures. YX contributed to the conception of the

manuscript and performed literature searches. MZL participated in

writing and revising the manuscript. Data authentication is not

applicable. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Serhan CN and Sulciner ML: Resolution

medicine in cancer, infection, pain and inflammation: Are we on

track to address the next Pandemic? Cancer Metastasis Rev.

42:13–17. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Furman D, Campisi J, Verdin E,

Carrera-Bastos P, Targ S, Franceschi C, Ferrucci L, Gilroy DW,

Fasano A, Miller GW, et al: Chronic inflammation in the etiology of

disease across the life span. Nat Med. 25:1822–1832.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Lee KE, Tu VY and Faye AS: Optimal

management of refractory Crohn's disease: Current landscape and

future direction. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 17:75–86. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Hofman ZLM, Roodenrijs NMT, Nikiphorou E,

Kent AL, Nagy G, Welsing PMJ and van Laar JM: Difficult-to-treat

rheumatoid arthritis: What have we learned and what do we still

need to learn? Rheumatology (Oxford). 64:65–73. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Pelaia C, Giacalone A, Ippolito G, Pastore

D, Maglio A, Piazzetta GL, Lobello N, Lombardo N, Vatrella A and

Pelaia G: Difficult-to-treat and severe asthma: Can real-world

studies on effectiveness of biological treatments change the lives

of patients? Pragmat Obs Res. 15:45–51. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Bertin L, Crepaldi M, Zanconato M,

Lorenzon G, Maniero D, De Barba C, Bonazzi E, Facchin S, Scarpa M,

Ruffolo C, et al: Refractory Crohn's disease: Perspectives, unmet

needs and innovations. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 17:261–315.

2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Chadda KR and Puthucheary Z: Persistent

inflammation, immunosuppression, and catabolism syndrome (PICS): A

review of definitions, potential therapies, and research

priorities. Br J Anaesth. 132:507–518. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Halpin DM, Miravitlles M, Metzdorf N and

Celli B: Impact and prevention of severe exacerbations of COPD: A

review of the evidence. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis.

12:2891–2908. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Papi A, Brightling C, Pedersen SE and

Reddel HK: Asthma. Lancet. 391:783–800. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J,

Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I and Jemal A: Global cancer statistics

2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for

36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 74:229–263.

2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Kumari N, Dwarakanath BS, Das A and Bhatt

AN: Role of interleukin-6 in cancer progression and therapeutic

resistance. Tumour Biol. 37:11553–11572. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Raeber ME, Sahin D and Boyman O:

Interleukin-2-based therapies in cancer. Sci Transl Med.

14(eabo5409)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Nguyen KG, Vrabel MR, Mantooth SM, Hopkins

JJ, Wagner ES, Gabaldon TA and Zaharoff DA: Localized

interleukin-12 for cancer immunotherapy. Front Immunol.

11(575597)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Ye C, Yano H, Workman CJ and Vignali DAA:

Interleukin-35: Structure, function and its impact on

immune-related diseases. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 41:391–406.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Salkeni MA and Naing A: Interleukin-10 in

cancer immunotherapy: From bench to bedside. Trends Cancer.

9:716–725. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Chen L, Fan J, Chen H, Meng Z, Chen Z,

Wang P and Liu L: The IL-8/CXCR1 axis is associated with cancer

stem cell-like properties and correlates with clinical prognosis in

human pancreatic cancer cases. Sci Rep. 4(5911)2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Ji Z, Tian W, Gao W, Zang R, Wang H and

Yang G: Cancer-associated fibroblast-derived interleukin-8 promotes

ovarian cancer cell stemness and malignancy through the

notch3-mediated signaling. Front Cell Dev Biol.

9(684505)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Uwagboe I, Adcock IM, Lo Bello F, Caramori

G and Mumby S: New drugs under development for COPD. Minerva Med.

113:471–496. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Ghallab AM, Eissa RA and El Tayebi HM:

CXCR2 small-molecule antagonist combats chemoresistance and

eenhances immunotherapy in triple-negative breast cancer. Front

Pharmacol. 13(862125)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Alfaro C, Sanmamed MF, Rodríguez-Ruiz ME,

Teijeira Á, Oñate C, González Á, Ponz M, Schalper KA, Pérez-Gracia

JL and Melero I: Interleukin-8 in cancer pathogenesis, treatment

and follow-up. Cancer Treat Rev. 60:24–31. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Chapman RW, Minnicozzi M, Celly CS,

Phillips JE, Kung TT, Hipkin RW, Fan X, Rindgen D, Deno G, Bond R,

et al: A novel, orally active CXCR1/2 receptor antagonist,

Sch527123, inhibits neutrophil recruitment, mucus production, and

goblet cell hyperplasia in animal models of pulmonary inflammation.

J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 322:486–493. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Singh S, Sadanandam A, Nannuru KC, Varney

ML, Mayer-Ezell R, Bond R and Singh RK: Small-molecule antagonists

for CXCR2 and CXCR1 inhibit human melanoma growth by decreasing

tumor cell proliferation, survival, and angiogenesis. Clin Cancer

Res. 15:2380–2386. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Khanam A, Trehanpati N, Riese P, Rastogi

A, Guzman CA and Sarin SK: Blockade of Neutrophil's chemokine

receptors CXCR1/2 abrogate liver damage in acute-on-chronic liver

failure. Front Immunol. 8(464)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Baggiolini M and Clark-Lewis I:

Interleukin-8, a chemotactic and inflammatory cytokine. FEBS Lett.

307:97–101. 1992.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Gonsiorek W, Fan X, Hesk D, Fossetta J,

Qiu H, Jakway J, Billah M, Dwyer M, Chao J, Deno G, et al:

Pharmacological characterization of Sch527123, a potent allosteric

CXCR1/CXCR2 antagonist. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 322:477–485.

2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Fu S, Chen X, Lin HJ and Lin J: Inhibition

of interleukin 8/C-X-C chemokine receptor 1,/2 signaling reduces

malignant features in human pancreatic cancer cells. Int J Oncol.

53:349–357. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Zinkernagel AS, Timmer AM, Pence MA, Locke

JB, Buchanan JT, Turner CE, Mishalian I, Sriskandan S, Hanski E and

Nizet V: The IL-8 protease SpyCEP/ScpC of group A Streptococcus

promotes resistance to neutrophil killing. Cell Host Microbe.

4:170–178. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Simpson S, Kaislasuo J, Guller S and Pal

L: Thermal stability of cytokines: A review. Cytokine.

125(154829)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Matsushima K, Yang D and Oppenheim JJ:

Interleukin-8: An evolving chemokine. Cytokine.

153(155828)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Kofanova O, Henry E, Aguilar Quesada R,

Bulla A, Navarro Linares H, Lescuyer P, Shea K, Stone M, Tybring G,

Bellora C and Betsou F: IL8 and IL16 levels indicate serum and

plasma quality. Clin Chem Lab Med. 56:1054–1062. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Shkundin A and Halaris A: IL-8 (CXCL8)

correlations with psychoneuroimmunological processes and

neuropsychiatric conditions. J Pers Med. 14(488)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Kunkel SL, Standiford T, Kasahara K and

Strieter RM: Interleukin-8 (IL-8): The major neutrophil chemotactic

factor in the lung. Exp Lung Res. 17:17–23. 1991.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Harada A, Sekido N, Akahoshi T, Wada T,

Mukaida N and Matsushima K: Essential involvement of interleukin-8

(IL-8) in acute inflammation. J Leukoc Biol. 56:559–564.

1994.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Rampart M, Van Damme J, Zonnekeyn L and

Herman AG: Granulocyte chemotactic protein/interleukin-8 induces

plasma leakage and neutrophil accumulation in rabbit skin. Am J

Pathol. 135:21–25. 1989.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Brennan FM, Zachariae CO, Chantry D,

Larsen CG, Turner M, Maini RN, Matsushima K and Feldmann M:

Detection of interleukin 8 biological activity in synovial fluids

from patients with rheumatoid arthritis and production of

interleukin 8 mRNA by isolated synovial cells. Eur J Immunol.

20:2141–2144. 1990.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Scheibenbogen C, Möhler T, Haefele J,

Hunstein W and Keilholz U: Serum interleukin-8 (IL-8) is elevated

in patients with metastatic melanoma and correlates with tumour

load. Melanoma Res. 5:179–181. 1995.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Waugh DJJ and Wilson C: The interleukin-8

pathway in cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 14:6735–6741. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Luppi F, Longo AM, de Boer WI, Rabe KF and

Hiemstra PS: Interleukin-8 stimulates cell proliferation in

non-small cell lung cancer through epidermal growth factor receptor

transactivation. Lung Cancer. 56:25–33. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Grivennikov SI, Greten FR and Karin M:

Immunity, inflammation, and cancer. Cell. 140:883–899.

2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Singh N, Baby D, Rajguru JP, Patil PB,

Thakkannavar SS and Pujari VB: Inflammation and cancer. Ann Afr

Med. 18:121–126. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Li X, Li J, Zhang Y and Zhang L: The role

of IL-8 in the chronic airway inflammation and its research

progress. Lin Chuang Er Bi Yan Hou Tou Jing Wai Ke Za Zhi.

35:1144–1148. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar : (In Chinese).

|

|

42

|

Ghasemi H, Ghazanfari T, Yaraee R,

Faghihzadeh S and Hassan ZM: Roles of IL-8 in ocular inflammations:

A review. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 19:401–412. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Cheng Y, Ma XL, Wei YQ and Wei XW:

Potential roles and targeted therapy of the CXCLs/CXCR2 axis in

cancer and inflammatory diseases. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer.

1871:289–312. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Zhang J, Shao N, Yang X, Xie C, Shi Y and

Lin Y: Interleukin-8 promotes epithelial-to-mesenchymal ransition

via downregulation of mir-200 family in breast cancer cells.

Technol Cancer Res Treat: Dec 7, 2020 (Epub ahead of print). doi:

10.1177/1533033820979672.

|

|

45

|

Li XJ, Peng LX, Shao JY, Lu WH, Zhang JX,

Chen S, Chen ZY, Xiang YQ, Bao YN, Zheng FJ, et al: As an

independent unfavorable prognostic factor, IL-8 promotes metastasis

of nasopharyngeal carcinoma through induction of

epithelial-mesenchymal transition and activation of AKT signaling.

Carcinogenesis. 33:1302–1309. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Park SY, Han J, Kim JB, Yang MG, Kim YJ,

Lim HJ, An SY and Kim JH: Interleukin-8 is related to poor

chemotherapeutic response and tumourigenicity in hepatocellular

carcinoma. Eur J Cancer. 50:341–350. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Merritt WM, Lin YG, Spannuth WA, Fletcher

MS, Kamat AA, Han LY, Landen CN, Jennings N, De Geest K, Langley

RR, et al: Effect of interleukin-8 gene silencing with

liposome-encapsulated small interfering RNA on ovarian cancer cell

growth. J Natl Cancer Inst. 100:359–372. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

White JR, Lee JM, Young PR, Hertzberg RP,

Jurewicz AJ, Chaikin MA, Widdowson K, Foley JJ, Martin LD, Griswold

DE and Sarau HM: Identification of a potent, selective non-peptide

CXCR2 antagonist that inhibits interleukin-8-induced neutrophil

migration. J Biol Chem. 273:10095–10098. 1998.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Li JJ, Carson KG, Trivedi BK, Yue WS, Ye

Q, Glynn RA, Miller SR, Connor DT, Roth BD, Luly JR, et al:

Synthesis and structure-activity relationship of

2-amino-3-heteroaryl-quinoxalines as non-peptide, small-molecule

antagonists for interleukin-8 receptor. Bioorg Med Chem.

11:3777–3790. 2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Dwyer MP, Yu Y, Chao J, Aki C, Chao J,

Biju P, Girijavallabhan V, Rindgen D, Bond R, Mayer-Ezel R, et al:

Discovery of 2-hydroxy-N,N-dimethyl-3-{2-[[(R)-1-(5-

methylfuran-2-yl)propyl]amino]-3,4-dioxocyclobut-1-enylamino}benzamide

(SCH 527123): A potent, orally bioavailable CXCR2/CXCR1 receptor

antagonist. J Med Chem. 49:7603–7606. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Russo RC, Garcia CC, Teixeira MM and

Amaral FA: The CXCL8/IL-8 chemokine family and its receptors in

inflammatory diseases. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 10:593–619.

2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Sitaru S, Budke A, Bertini R and Sperandio

M: Therapeutic inhibition of CXCR1/2: Where do we stand? Intern

Emerg Med. 18:1647–1664. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Holz O, Khalilieh S, Ludwig-Sengpiel A,

Watz H, Stryszak P, Soni P, Tsai M, Sadeh J and Magnussen H:

SCH527123, a novel CXCR2 antagonist, inhibits ozone-induced

neutrophilia in healthy subjects. Eur Respir J. 35:564–570.

2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Mims JW: Asthma: Definitions and

pathophysiology. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 5 (Suppl 1):S2–S6.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Bizzarri C, Beccari AR, Bertini R,

Cavicchia MR, Giorgini S and Allegretti M: ELR+ CXC chemokines and

their receptors (CXC chemokine receptor 1 and CXC chemokine

receptor 2) as new therapeutic targets. Pharmacol Ther.

112:139–149. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Ha H, Debnath B and Neamati N: Role of the

CXCL8-CXCR1/2 axis in cancer and inflammatory diseases.

Theranostics. 7:1543–1588. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Nocker RE, Schoonbrood DF, van de Graaf

EA, Hack CE, Lutter R, Jansen HM and Out TA: Interleukin-8 in

airway inflammation in patients with asthma and chronic obstructive

pulmonary disease. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 109:183–191.

1996.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

58

|

Nair P, Gaga M, Zervas E, Alagha K,

Hargreave FE, O'Byrne PM, Stryszak P, Gann L, Sadeh J and Chanez P:

Study Investigators. Safety and efficacy of a CXCR2 antagonist in

patients with severe asthma and sputum neutrophils: A randomized,

placebo-controlled clinical trial. Clin Exp Allergy. 42:1097–1103.

2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

59

|

Ordoñez CL, Shaughnessy TE, Matthay MA and

Fahy JV: Increased neutrophil numbers and IL-8 levels in airway

secretions in acute severe asthma: Clinical and biologic

significance. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 161:1185–1190.

2000.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

60

|

Yan Q, Zhang X, Xie Y, Yang J, Liu C,

Zhang M, Zheng W, Lin X, Huang HT, Liu X, et al: Bronchial

epithelial transcriptomics and experimental validation reveal

asthma severity-related neutrophilc signatures and potential

treatments. Commun Biol. 7(181)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

61

|

Todd CM, Salter BM, Murphy DM, Watson RM,

Howie KJ, Milot J, Sadeh J, Boulet LP, O'Byrne PM and Gauvreau GM:

The effects of a CXCR1/CXCR2 antagonist on neutrophil migration in

mild atopic asthmatic subjects. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 41:34–39.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

62

|

Raherison C and Girodet PO: Epidemiology

of COPD. Eur Respir Rev. 18:213–221. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

63

|

Kaur M and Singh D: Neutrophil chemotaxis

caused by chronic obstructive pulmonary disease alveolar

macrophages: The role of CXCL8 and the receptors CXCR1/CXCR2. J

Pharmacol Exp Ther. 347:173–180. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

64

|

Demkow U and van Overveld FJ: Role of

elastases in the pathogenesis of chronic obstructive pulmonary

disease: Implications for treatment. Eur J Med Res. 15 (Suppl

2):S27–S35. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

65

|

Kim S and Nadel JA: Role of neutrophils in

mucus hypersecretion in COPD and implications for therapy. Treat

Respir Med. 3:147–159. 2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

66

|

Arai N, Kondo M, Izumo T, Tamaoki J and

Nagai A: Inhibition of neutrophil elastase-induced goblet cell

metaplasia by tiotropium in mice. Eur Respir J. 35:1164–1171.

2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

67

|

Voynow JA, Fischer BM, Malarkey DE, Burch

LH, Wong T, Longphre M, Ho SB and Foster WM: Neutrophil elastase

induces mucus cell metaplasia in mouse lung. Am J Physiol Lung Cell

Mol Physiol. 287:L1293–L1302. 2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

68

|

Wang Q, Shao X, Zhang Y, Zhu M, Wang FXC,

Mu J, Li J, Yao H and Chen K: Role of tumor microenvironment in

cancer progression and therapeutic strategy. Cancer Med.

12:11149–11165. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

69

|

Desai SA, Patel VP, Bhosle KP, Nagare SD

and Thombare KC: The tumor microenvironment: Shaping cancer

progression and treatment response. J Chemother. 37:15–44.

2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

70

|

Cheng K, Cai N, Zhu J, Yang X, Liang H and

Zhang W: Tumor-associated macrophages in liver cancer: From

mechanisms to therapy. Cancer Commun (Lond). 42:1112–1140.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

71

|

Lorusso G and Rüegg C: The tumor

microenvironment and its contribution to tumor evolution toward

metastasis. Histochem Cell Biol. 130:1091–1103. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

72

|

Chao CC, Lee CW, Chang TM, Chen PC and Liu

JF: CXCL1/CXCR2 paracrine axis contributes to lung metastasis in

osteosarcoma. Cancers (Basel). 12(459)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

73

|

Wu T, Yang W, Sun A, Wei Z and Lin Q: The

role of CXC chemokines in cancer progression. Cancers (Basel).

15(167)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

74

|

Ganesan P and Kulik LM: Hepatocellular

carcinoma: New developments. Clini Liver Dis. 27:85–102.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

75

|

Lee JG, Kang CM, Park JS, Kim KS, Yoon DS,

Choi JS, Lee WJ and Kim BR: The actual five-year survival rate of

hepatocellular carcinoma patients after curative resection. Yonsei

Med J. 47:105–112. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

76

|

Anwanwan D, Singh SK, Singh S, Saikam V

and Singh R: Challenges in liver cancer and possible treatment

approaches. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer.

1873(188314)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

77

|

Bi H, Zhang Y, Wang S, Fang W, He W, Yin

L, Xue Y, Cheng Z, Yang M and Shen J: Interleukin-8 promotes cell

migration via CXCR1 and CXCR2 in liver cancer. Oncol Lett.

18:4176–4184. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

78

|

Yang S, Wang H, Qin C, Sun H and Han Y:

Up-regulation of CXCL8 expression is associated with a poor

prognosis and enhances tumor cell malignant behaviors in liver

cancer. Biosci Rep. 40(BSR20201169)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

79

|

Sun F, Wang J, Sun Q, Li F, Gao H, Xu L,

Zhang J, Sun X, Tian Y, Zhao Q, et al: Interleukin-8 promotes

integrin β3 upregulation and cell invasion through PI3K/Akt pathway

in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Exp Clin Cancer Res.

38(449)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

80

|

Varney ML, Singh S, Li A, Mayer-Ezell R,

Bond R and Singh RK: Small molecule antagonists for CXCR2 and CXCR1

inhibit human colon cancer liver metastases. Cancer Lett.

300:180–188. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

81

|

Vincent A, Herman J, Schulick R, Hruban RH

and Goggins M: Pancreatic cancer. Lancet. 378:607–620.

2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

82

|

Goral V: Pancreatic cancer: Pathogenesis

and diagnosis. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 16:5619–5624.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

83

|

Zhao Z and Liu W: Pancreatic cancer: A

review of risk factors, diagnosis, and treatment. Technol Cancer

Res Treat: Dec 24, 2020 (Epub ahead of print). doi:

10.1177/1533033820962117.

|

|

84

|

National Cancer Institute: Pancreatic

cancer treatment (PDQ®)-Health Professional Version.

National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD, 2025.

|

|

85

|

Liu Q, Li A, Tian Y, Wu JD, Liu Y, Li T,

Chen Y, Han X and Wu K: The CXCL8-CXCR1/2 pathways in cancer.

Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 31:61–71. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

86

|

Xiong X, Liao X, Qiu S, Xu H, Zhang S,

Wang S, Ai J and Yang L: CXCL8 in tumor biology and its

implications for clinical translation. Front Mol Biosci.

9(723846)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

87

|

Ning Y, Labonte MJ, Zhang W, Bohanes PO,

Gerger A, Yang D, Benhaim L, Paez D, Rosenberg DO, Nagulapalli

Venkata KC, et al: The CXCR2 antagonist, SCH-527123, shows

antitumor activity and sensitizes cells to oxaliplatin in

preclinical colon cancer models. Mol Cancer Ther. 11:1353–1364.

2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

88

|

Fu S and Lin J: Blocking interleukin-6 and

interleukin-8 signaling inhibits cell viability, colony-forming

activity, and cell migration in human triple-negative breast cancer

and pancreatic cancer cells. Anticancer Res. 38:6271–6279.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

89

|

Stewart C, Ralyea C and Lockwood S:

Ovarian cancer: An integrated review. Semin Oncol Nurs. 35:151–156.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

90

|

Feng J, Xu L, Chen Y, Lin R, Li H and He

H: Trends in incidence and mortality for ovarian cancer in China

from 1990 to 2019 and its forecasted levels in 30 years. J Ovarian

Res. 16(139)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

91

|

Reid BM, Permuth JB and Sellers TA:

Epidemiology of ovarian cancer: A review. Cancer Biol Med. 14:9–32.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

92

|

Ali AT, Al-Ani O and Al-Ani F:

Epidemiology and risk factors for ovarian cancer. Prz Menopauzalny.

22:93–104. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

93

|

Zhang R, Roque DM, Reader J and Lin J:

Combined inhibition of IL-6 and IL-8 pathways suppresses ovarian

cancer cell viability and migration and tumor growth. Int J Oncol.

60(50)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

94

|

Rašková M, Lacina L, Kejík Z, Venhauerová

A, Skaličková M, Kolář M, Jakubek M, Rosel D, Smetana K Jr and

Brábek J: The role of IL-6 in cancer cell invasiveness and

metastasis-overview and therapeutic opportunities. Cells.

11(3698)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

95

|

Shahzad MM, Arevalo JM, Armaiz-Pena GN, Lu

C, Stone RL, Moreno-Smith M, Nishimura M, Lee JW, Jennings NB,

Bottsford-Miller J, et al: Stress effects on FosB- and

interleukin-8 (IL8)-driven ovarian cancer growth and metastasis. J

Biol Chem. 285:35462–35470. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

96

|

Son JS, Chow R, Kim H, Lieu T, Xiao M, Kim

S, Matuszewska K, Pereira M, Nguyen DL and Petrik J: Liposomal

delivery of gene therapy for ovarian cancer: A systematic review.

Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 21(75)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

97

|

Li Y, Liu L, Yin Z, Xu H, Li S, Tao W,

Cheng H, Du L, Zhou X and Zhang B: Effect of targeted silencing of

IL-8 on in vitro migration and invasion of SKOV3 ovarian

cancer cells. Oncol Lett. 13:567–572. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

98

|

Singh S, Wu S, Varney M, Singh AP and

Singh RK: CXCR1 and CXCR2 silencing modulates CXCL8-dependent

endothelial cell proliferation, migration and capillary-like

structure formation. Microvasc Res. 82:318–325. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

99

|

Park GY, Pathak HB, Godwin AK and Kwon Y:

Epithelial-stromal communication via CXCL1-CXCR2 interaction

stimulates growth of ovarian cancer cells through p38 activation.

Cell Oncol (Dordr). 44:77–92. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

100

|

Yang G, Rosen DG, Liu G, Yang F, Guo X,

Xiao X, Xue F, Mercado-Uribe I, Huang J, Lin SH, et al: CXCR2

promotes ovarian cancer growth through dysregulated cell cycle,

diminished apoptosis, and enhanced angiogenesis. Clin Cancer Res.

16:3875–3886. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

101

|

Li A, Dubey S, Varney ML, Dave BJ and

Singh RK: IL-8 directly enhanced endothelial cell survival,

proliferation, and matrix metalloproteinases production and

regulated angiogenesis. J Immunol. 170:3369–3376. 2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

102

|

Wang ZX, Cao JX, Liu ZP, Cui YX, Li CY, Li

D, Zhang XY, Liu JL and Li JL: Combination of chemotherapy and

immunotherapy for colon cancer in China: A meta-analysis. World J

Gastroenterol. 20:1095–1106. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

103

|

Katsaounou K, Nicolaou E, Vogazianos P,

Brown C, Stavrou M, Teloni S, Hatzis P, Agapiou A, Fragkou E,

Tsiaoussis G, et al: Colon cancer: From epidemiology to prevention.

Metabolites. 12(499)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

104

|

André T, Boni C, Mounedji-Boudiaf L,

Navarro M, Tabernero J, Hickish T, Topham C, Zaninelli M, Clingan

P, Bridgewater J, et al: Oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin

as adjuvant treatment for colon cancer. N Engl J Med.

350:2343–2351. 2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

105

|

Singh JK, Farnie G, Bundred NJ, Simões BM,

Shergill A, Landberg G, Howell SJ and Clarke RB: Targeting CXCR1/2

significantly reduces breast cancer stem cell activity and

increases the efficacy of inhibiting HER2 via HER2-dependent and

-independent mechanisms. Clin Cancer Res. 19:643–656.

2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

106

|

Khan MN, Wang B, Wei J, Zhang Y, Li Q,

Luan X, Cheng JW, Gordon JR, Li F and Liu H: CXCR1/2 antagonism

with CXCL8/Interleukin-8 analogue CXCL8(3-72)K11R/G31P restricts

lung cancer growth by inhibiting tumor cell proliferation and

suppressing angiogenesis. Oncotarget. 6:21315–21327.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

107

|

Hertzer KM, Donald GW and Hines OJ: CXCR2:

A target for pancreatic cancer treatment? Expert Opin Ther Targets.

17:667–680. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

108

|

Gungabeesoon J, Gort-Freitas NA, Kiss M,

Bolli E, Messemaker M, Siwicki M, Hicham M, Bill R, Koch P,

Cianciaruso C, et al: A neutrophil response linked to tumor control

in immunotherapy. Cell. 186:1448–1464.e20. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|