Introduction

The spleen is the largest lymphoid organ in the

body, and plays a pivotal role in regulating hematologic and immune

homeostasis (1). A wide range of

conditions, including hematologic malignancies, infections and

inflammatory disorders (systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid

arthritis, sarcoidosis), can induce alterations in splenic volume,

morphology and metabolic activity (2). Imaging serves as a critical tool for

evaluating splenic architecture, facilitating the distinction

between focal and diffuse patterns of involvement (3). Among these, diffuse infiltration

poses the greatest diagnostic challenge, arising from either the

accumulation of normal or neoplastic cellular elements, or from

congestion due to hyperemia and impaired venous outflow (3).

Myelofibrosis (MF) is a myeloproliferative neoplasm

of unclear etiology. MF is a rare disorder that typically

progresses insidiously during the early-stage and is characterized

by non-specific clinical manifestations (fatigue, weight loss,

night sweats, and mild abdominal discomfort), contributing to a

high rate of misdiagnosis (4).

Early-stage MF often presents with splenomegaly and cytopenia,

clinical features that can be readily mistaken for liver cirrhosis

(5,6). Consequently, patients frequently

first seek medical evaluation in gastroenterology or infectious

disease clinics, reflecting the subtlety of hematologic

abnormalities at presentation. Due to the limited familiarity with

MF within these clinics, treatment is often suboptimal. MF has

frequently advanced to the intermediate or late stages before

patients are referred to the hematology department, which results

in poor treatment outcomes and prognosis (7). Hence, there is a critical need for

early differential diagnosis between MF and liver cirrhosis.

Non-invasive methods are particularly valuable for assessing the

underlying causes of splenic involvement in patients, given the

constraints of splenic biopsy. Distinguishing variations based on

the qualitative features of spleen cross-sectional images is a

notable challenge (8).

Radiomics, an emerging tool in precision medicine,

leverages advanced algorithms to automatically extract quantitative

features, such as lesion intensity, morphology and texture, from

medical imaging datasets. These features can then be integrated

into predictive models that enhance clinical decision-making

(9). To the best of our knowledge,

no studies have directly compared ultrasound-based radiomic

signatures of splenomegaly attributable to MF vs. liver cirrhosis.

The present study aimed to develop a nomogram incorporating

clinical and ultrasound radiomics features of the spleen to

noninvasively distinguish early-stage MF from cirrhosis, thereby

offering a valuable reference for guiding therapeutic strategies

and patient management.

Materials and methods

Study cohort

The present retrospective study included a total of

40 patients with confirmed MF and treated at Wuxi People's Hospital

(Wuxi, China) or The Second Affiliated Hospital of Soochow

University (Suzhou, China) between January 2020 and August 2024

were included in the present study. The MF cohort comprised of 22

male patients and 18 female patients, aged between 53 and 73 years,

with an average age of 62.93±12.96 years (mean ± SD). Additionally,

50 patients with clinically diagnosed hepatitis B-related cirrhosis

and portal hypertension were selected from the same institutions

during the same period. The cirrhosis group included 36 male and 14

women, aged between 40 and 75 years, with an average age of

50.93±12.96 years. The patients were randomly allocated into a

training set consisting of 72 cases (including 32 patients with MF)

and a validation set comprising of 18 cases (including 8 patients

with MF). Allocation was performed using stratified sampling at an

8:2 ratio. The inclusion criteria comprised: i) Availability of

complete, unannotated ultrasound images suitable for analysis; ii)

a definitive clinical diagnosis supported by comprehensive clinical

data and the absence of prior surgical intervention; and iii) no

history of treatment prior to imaging. The exclusion criteria

encompassed: i) Normal splenic volume; ii) splenic infarction; iii)

presence of cystic or solid splenic lesions; and iv) thrombosis of

the portal or splenic veins. The present study was approved by The

Medical Ethics Committee of Wuxi People's Hospital (approval no.

KY23017). Written informed consent was obtained from the patients

for participation and for the publication of clinical details and

accompanying images.

Clinical data collection

The electronic medical record system was used to

retrieve the clinical data of patients, including the direct

bilirubin level, glutamic-pyruvic transaminase, γ-glutamyl

transferase, glutamic-oxalacetic transaminase and the isozyme of

glutamic-oxalacetic transaminase, as well as complete blood count

parameters including platelet counts.

Ultrasound examination

All ultrasound examinations were performed using

standardized settings: Frequency 3.5-5 MHz, dynamic range 60-65 dB,

gain 50-60%, depth 15-20 cm, focus position at the level of the

spleen, and tissue harmonic imaging enabled. Images were saved in

DICOM format with a resolution of 1,024x768 pixels without

compression. All examinations were performed by sonographers with

>5 years of experience in abdominal imaging. All patients were

required to fast for 8 h before the examination. The present study

utilized the LOGIQ™ E9 color Doppler ultrasound diagnostic

instrument (GE Healthcare) equipped with a convex array probe

operating at 3.5-5 MHz. Patients were positioned in a supine

stance, with their left arm raised above their head to optimize the

supracostal access. The probe was placed between the 9th and 11th

left ribs to capture the oblique section of the major axis of the

spleen. The maximum major-axis section of the spleen was preserved

for subsequent analysis. The major axis and thickness of the spleen

were recorded by identifying the section with the maximum major

axis, with three measurements averaged for accuracy. Portal vein

diameter was measured at the crossing point of the hepatic artery

and splenic vein diameter was measured 2 cm from the splenic hilum

during quiet respiration. These measurements were averaged from

three consecutive readings during the same examination for

accuracy. These procedures were documented and assessed by two

ultrasonography physicians, each with >10 years of diagnostic

experience. The physicians were blinded to each other's diagnoses

and pathological findings. Any discrepancies in diagnoses were

resolved through discussion to reach a consensus.

Image segmentation and data

preprocessing

A high-resolution image of the maximum major-axis

section of the spleen was imported into 3D-Slicer version 5.4

(slicer.org) in JPG format. Two experienced

ultrasonography physicians, each with >10 years of diagnostic

expertise, drew boundaries around the edge of the spleen on the

image. This ensured that the entire spleen was encompassed within

the largest possible region of interest (ROI). In cases where the

discrepancy between the two ROIs drawn by the physicians

(calculated as the ratio of the combined area of non-overlapping

parts to the total area of both ROIs) was <5%, the ROI was

defined as the overlapping region of the two. If the discrepancy

was >5%, the physicians discussed this and reached a consensus.

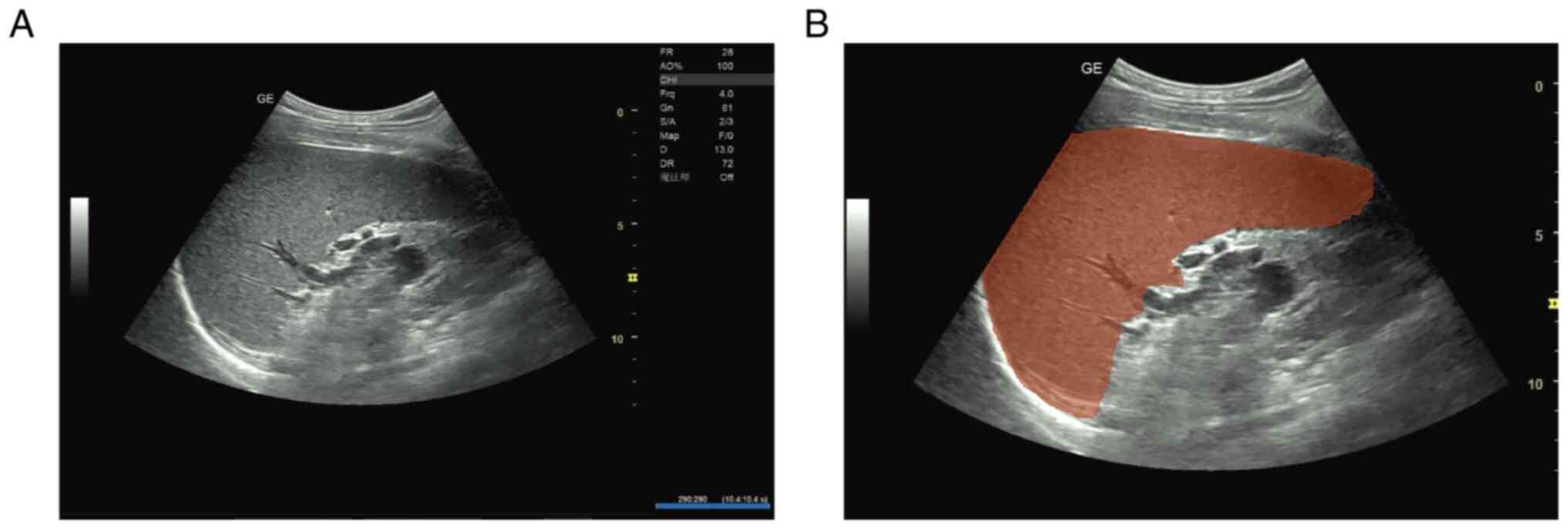

Fig. 1 illustrates the ROI

delineation process, showing the original grayscale ultrasound

image of an enlarged spleen (Fig.

1A) and the same image with manual ROI segmentation performed

by experienced sonographers (Fig.

1B).

To assess segmentation reproducibility, 30 randomly

selected cases (33%) were independently re-segmented (ROI redrawn)

by both ultrasonography physicians after a 4-week interval to

minimize recall bias. The inter-observer intraclass correlation

coefficient (ICC) for ROI segmentation was 0.892 [95% confidence

interval (CI), 0.845-0.932], and the intra-observer ICCs were 0.916

(95% CI, 0.878-0.948) for observer 1 and 0.909 (95% CI,

0.869-0.943) for observer 2. For radiomics feature extraction, an

inter-observer ICC of >0.85 for 782/837 features (93.4%) and

intra-observer ICC of >0.90 for 801/837 features (95.7%) was

achieved. Only features with an ICC of >0.75 were retained for

subsequent analysis.

Feature selection of ultrasound

radiomics

The PyRadiomics module in Python version 3.9 (Python

Software Foundation) was used to extract radiomics features from

the grayscale ultrasound images. Initially, the ICC was utilized to

assess the consistency of feature extraction between and within

observers in the ROI. Higher ICC indicated greater consistency and

improved repeatability. The analysis moved forward to the feature

screening stage when the ICC was >0.75 in both groups. A total

of 837 radiomics features were extracted, and Z-score normalization

was applied to standardize these features and mitigate the effects

of varying dimensions. Subsequently, two dimensionality reduction

methods were employed to refine the selection from the 837

features, which ensured a more manageable set for analysis: i) The

least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) algorithm,

with 5-fold cross-validation, was implemented to compress certain

regression coefficients. This was achieved by introducing a penalty

function that reduced the sum of the coefficients' absolute values

below a predetermined threshold. The glmnet package (version 4.1-7)

in R software (version 4.3.3, R Foundation for Statistical

Computing), with family=binomial for binary result data. Key

parameter α was set to 1 and cross-validation was conducted using

the cv.glmnet function. Two λ values, λ.min and λ.1se, were chosen:

λ.min minimized cross-validation errors, while lambda.1se favored a

more succinct model. The two provided a balance between model

complexity and prediction accuracy. Ultimately, variables

significant to prediction were identified based on non-zero

coefficients, which simplified the model and enhanced

interpretability. ii) The Boruta algorithm, a feature selection

technique rooted in a random forest, assessed feature importance by

creating shadow variables for each original variable in the

dataset. Utilizing Boruta package version 8.0.0 (cran.r-project.org/package=Boruta) for

feature selection, the algorithm systematically compared the

significance of each original variable against its shadow

counterpart. The importance of each variable was confirmed after

500 iterations or when all variables showed stability. The final

results were extracted using the attStats function in R, and the

format was refined with a custom adjustdata function in R

Establishment of a joint

clinical-radiomics model

Independent predictors for differentiating liver

cirrhosis from MF were identified using multivariate logistic

regression. Analysis was based on the independent influencing

factors of selected clinical and ultrasound characteristics, along

with ultrasound radiomics features from the training set.

Subsequently, a comprehensive clinical-radiomics model was

developed and a corresponding nomogram was created.

Statistical processing

Data analysis was conducted using R (version 4.3.3),

Python (version 3.7), and SPSS 27.0 (IBM Corp.) statistical

software. Measurement data that adhered to a normal distribution

are presented as the mean ± SD, with independent sample t-tests

performed for group comparisons. Categorical data are presented as

case counts, and χ2 test was used for group comparisons.

No categorical variables met criteria for statistical analysis in

this cohort. The predictive efficacy of the model in the training

and validation sets was evaluated by creating receiver operating

characteristic curves and determining the area under the curve

(AUC). P<0.05 (two-tailed) was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference.

Results

Selection of ultrasound radiomics

feature

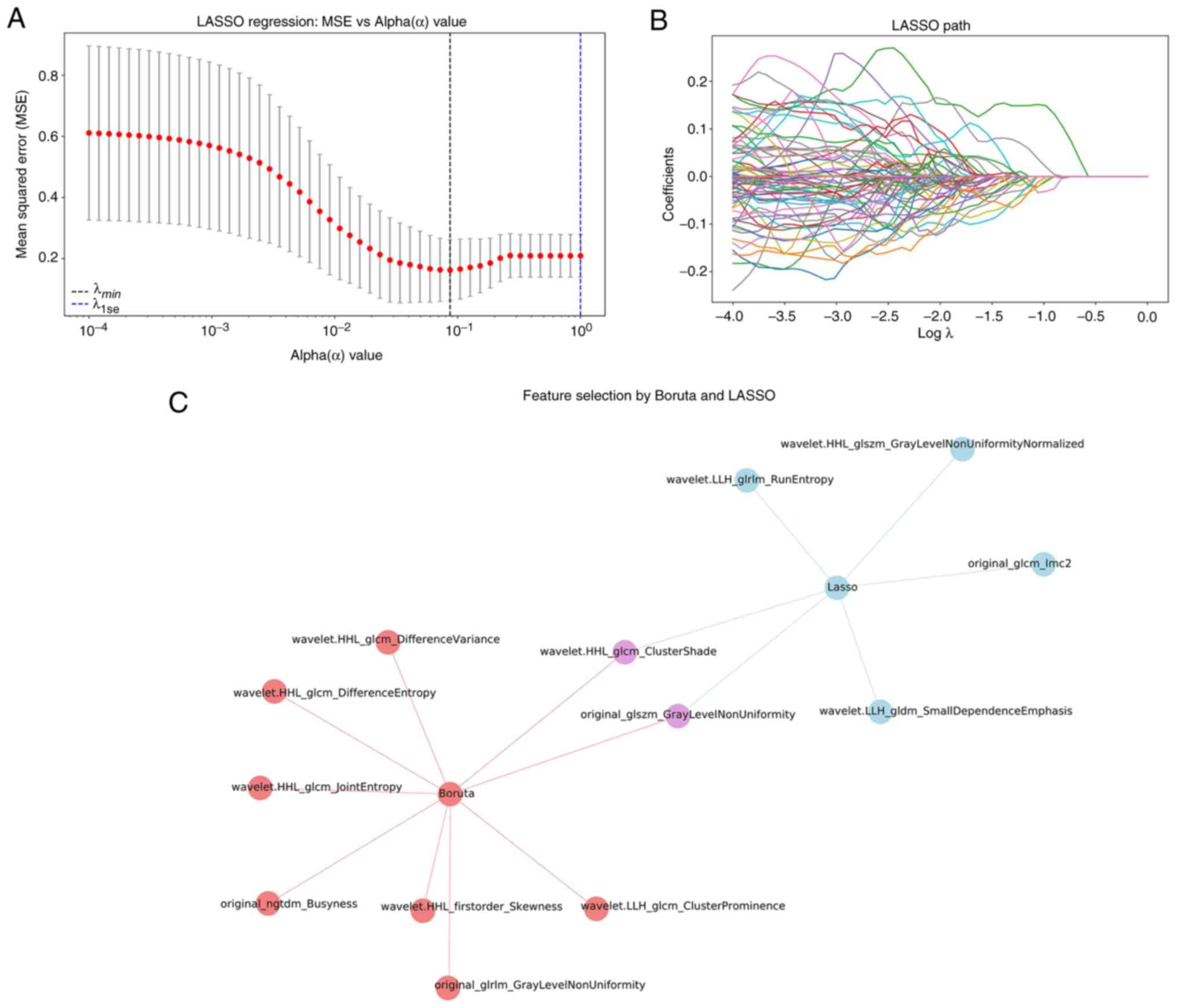

Using the PyRadiomics software package, 837

ultrasound image features of the spleen were extracted. Two key

radiomics features were identified after dimensionality reduction

by LASSO and Boruta algorithms: wavelet.HHL_glcm_ClusterShade (C1)

and original_glszm_GrayLevelNonUniformity (C2) (Fig. 2).

Univariate and multivariate analyses

of clinical and ultrasound radiomics data

The training set consisted of 72 patients, including

40 patients diagnosed with liver cirrhosis and 32 patients with MF.

In univariate analysis, significant differences in C2, direct

bilirubin, glutamic-pyruvic transaminase, glutamic-oxalacetic

transaminase and the major axis of the spleen were observed between

the two groups (all P<0.05). However, the C1, thickness of the

spleen, γ-glutamyl transferase and glutamic-oxalacetic transaminase

isozymes had no statistical significance between the two groups

(all P>0.05; Table I).

| Table IUnivariate analysis of clinical and

ultrasound radiomics data in the training set. |

Table I

Univariate analysis of clinical and

ultrasound radiomics data in the training set.

| Variable | Liver cirrhosis | Myelofibrosis | t-value | P-value |

|---|

| C1 | 0.01±0.87 | 0.63±1.11 | 2.054 | 0.051 |

| C2 | 0.70±0.28 | 1.30±0.60 | -3.790 | 0.001 |

| Spleen major ais

(mm) | 151.00±25.80 | 170.00±20.70 | -2.883 | 0.007 |

| Spleen thickness,

(mm) | 56.2±12.60 | 66.70±6.60 | -1.746 | 0.087 |

| Direct bilirubin

(µmol/l) | 18.00± 6.60 | 6.30±4.30 | 2.679 | 0.010 |

| Glutamic-pyruvic

transaminase (U/l) | 38.00±30.90 | 18.50±9.40 | 3.586 | <0.001 |

| γ-glutamyl

transferase (U/l) | 69.40±105.00 | 37.90± 3.40 | 1.789 | 0.079 |

| Glutamic-oxalacetic

transaminase (U/l) | 55.70±45.90 | 21.40±4.10 | 4.676 | <0.001 |

| Glutamic-oxalacetic

transaminase isozyme (U/l) | 16.70±8.60 | 12.90±5.90 | 1.874 | 0.068 |

| Platelet count

(x109/l) | 96.00±19.60 | 155.50±114.00 | -2.292 | 0.033 |

| Portal vein

(mm) | 13.60±1.55 | 12.40±1.31 | 3.361 | 0.002 |

| Splenic vein

(mm) | 9.50±1.50 | 9.60±2.20 | -0.221 | 0.826 |

As show in Table I,

univariate analysis revealed significant differences in portal vein

diameter between the two groups, with the liver cirrhosis group

showing larger portal vein diameters compared with the MF group

(13.6±1.55 vs. 12.4±1.31 mm, P=0.002). However, splenic vein

diameters showed no statistically significant difference between

the groups (9.5±1.5 vs. 9.6±2.2 mm, P=0.826). In the multivariate

logistic regression analysis (Table

II), portal vein diameter did not emerge as an independent

predictor for differentiating the two conditions. Platelet count

showed significant differences between the two groups (Table I: 96.00±19.60 vs. 155.50±114.00

x109/l, P=0.033), with both conditions demonstrating

thrombocytopenia but to varying degrees. The MF group showed more

variable platelet counts (ranging from 54-488 x109/l)

compared with the liver cirrhosis group.

| Table IIMultivariate analysis of clinical and

ultrasound radiomics data in the training set. |

Table II

Multivariate analysis of clinical and

ultrasound radiomics data in the training set.

| Variable | Regression

coefficient | Standard error | Wald χ2

value | P-value | OR value (95%

confidence intervals) |

|---|

| C2 | 3.694 | 1.608 | 5.279 | 0.022 | 40.218

(1.721-940.008) |

| Direct

bilirubin | -0.376 | 0.166 | 5.146 | 0.023 | 0.687

(0.496-0.950) |

| Glutamic-oxalacetic

transaminase | -0.211 | 0.104 | 4.137 | 0.042 | 0.810

(0.660-0.992) |

| Constant | 2.895 | 2.319 | 1.559 | 0.212 | 18.092

(-1.653-7.443) |

The dependent variable was coded as liver

cirrhosis=0 and MF=1. Multivariate logistic regression analysis

included all variables with P<0.05 in univariate analysis: C2,

direct bilirubin, glutamic-pyruvic transaminase,

glutamic-oxalacetic transaminase, and the major axis of the spleen.

Forward stepwise selection retained three variables in the final

model. C2, direct bilirubin and glutamic-oxalacetic transaminase

were identified as independent predictors for differentiating liver

cirrhosis from MF. The logistic regression equation for predicting

MF probability is: Logit (P)=2.895 + 3.694 x C2-0.376x direct

bilirubin -0.211 x glutamic-oxalacetic transaminase, where P

represents the probability of MF diagnosis (Table II).

Model construction and predictive

diagnosis effectiveness

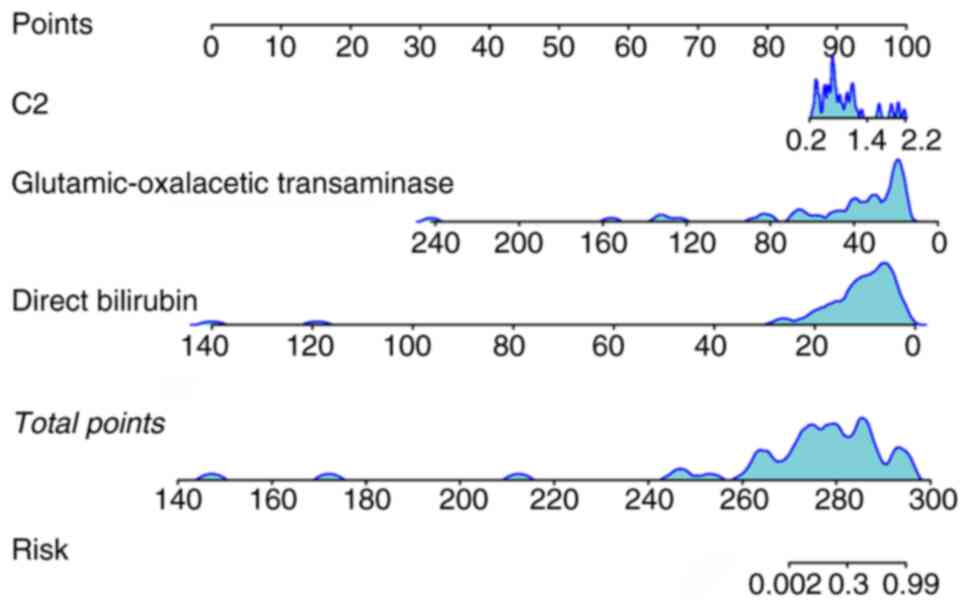

A nomogram model was developed by incorporating two

radiomics features (C1 and C2) and two clinical parameters (direct

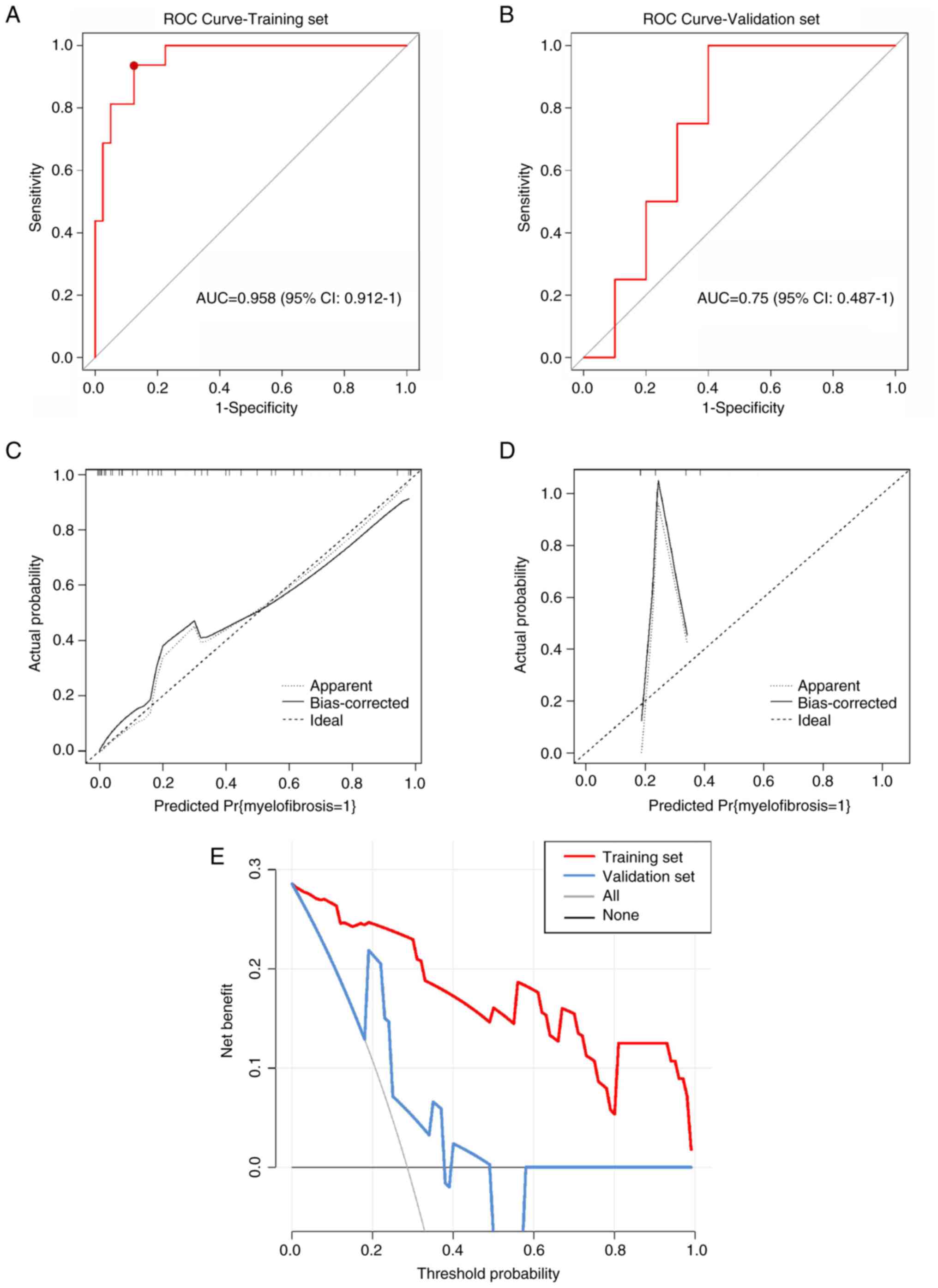

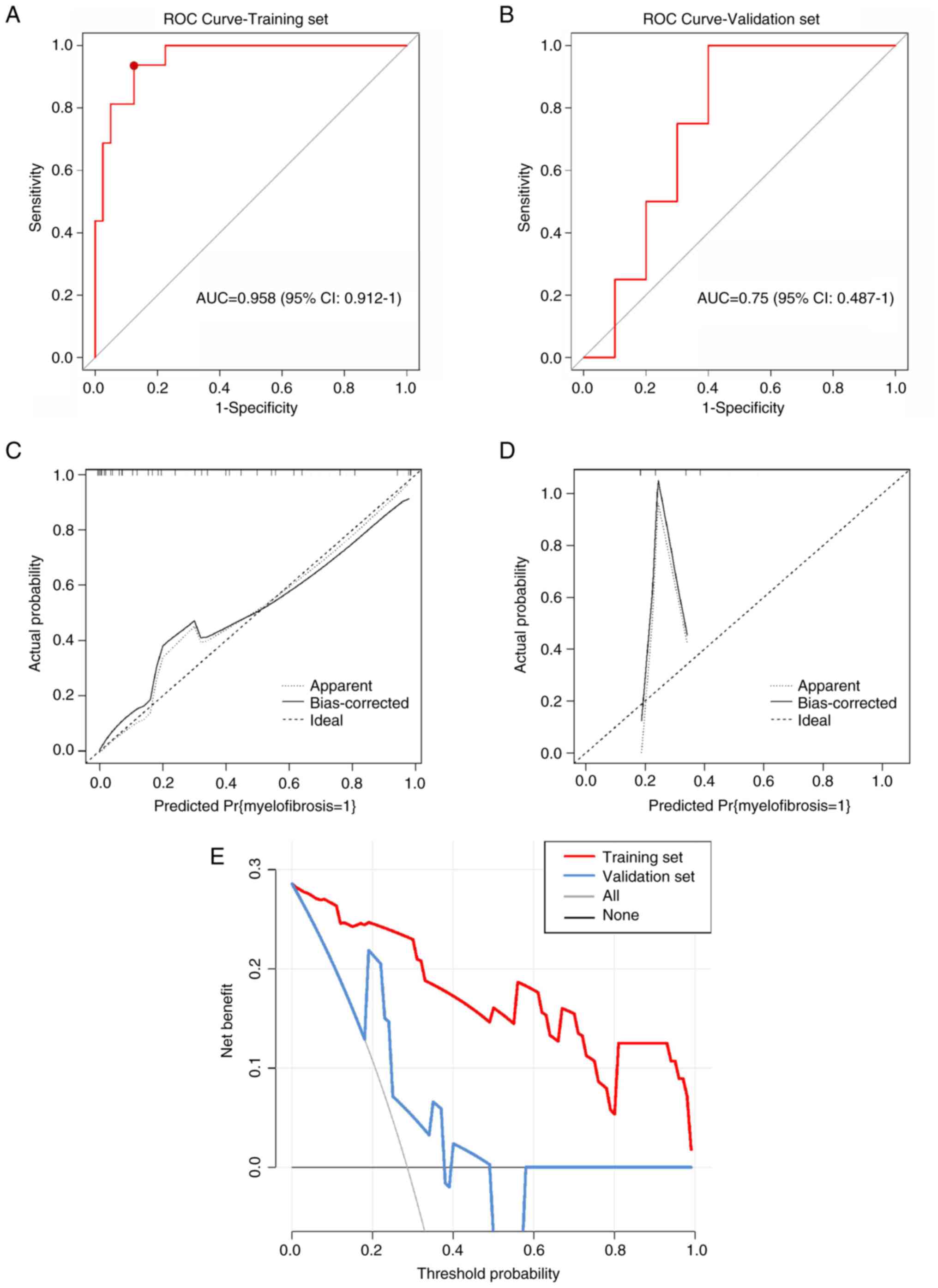

bilirubin and glutamic-oxalacetic transaminase levels) (Fig. 3). The model showed an AUC of 0.958

(95% CI, 0.912-1.0) for the training set and 0.750 (95% CI,

0.487-1.0) for the validation set (Fig. 4A and B). The model also achieved 93.8%

sensitivity, 87.5% specificity and 80.3% accuracy for the training

set, and 100% sensitivity, 60% specificity and 71.4% accuracy for

the validation set. The concordance between liver cirrhosis and

clinical diagnosis was 70% (35/50), and it was 100% (40/40) for MF.

Fig. 4C-E presents the calibration

and decision curves for both the training and validation sets.

| Figure 4Model performance validation and

clinical utility assessment. (A) ROC) curve for the training set

(n=72). The curve demonstrates excellent discrimination with

AUC=0.958 (95% CI, 0.912-1.0). The optimal cutoff point

(sensitivity=93.8%, specificity=87.5%) is marked with a red dot.

(B) ROC curve for the validation set (n=18). The curve shows

moderate discrimination with AUC=0.750 (95% CI, 0.487-1.0),

indicating acceptable but reduced performance compared to the

training set. (C) Calibration curve for the training set. The plot

demonstrates excellent agreement between predicted probabilities

(x-axis) and observed frequencies (y-axis), with the calibration

line closely following the diagonal reference line (perfect

calibration). (D) Calibration curve for the validation set. The

plot shows moderate calibration with some deviation from the

diagonal reference line, particularly at higher predicted

probabilities, suggesting slight model overconfidence in this

cohort. (E) Decision curve analysis for clinical utility

assessment. The graph displays net benefit (y-axis) across

threshold probabilities (x-axis, 0-1.0). The nomogram model (red

line) provides superior clinical utility compared to treat-all

strategy (blue line) or treat-none strategy (black horizontal line

at net benefit=0) for threshold probabilities between 0.1 and 0.8.

ROC, receiver operating characteristic; AUC, area under the curve;

CI, confidence interval. |

Model validation and stability

analysis

To assess potential overfitting given the difference

between training (AUC=0.958) and validation (AUC=0.750)

performance, additional validation analyses were performed.

Five-fold cross-validation within the training set yielded a mean

AUC of 0.856 (95% CI, 0.792-0.920), suggesting more modest

performance than the initial training AUC. Bootstrapping with 1,000

iterations revealed confidence intervals of 0.889-0.987 for the

training AUC, confirming model stability. When a more stringent

feature selection was applied using λ.1se instead of λ.min, the

model retained only the two most robust features (C2 and C1),

supporting their importance for differentiation.

Discussion

The spleen, a central lymphoid organ, plays a

critical role in the pathophysiology of infections (infectious

mononucleosis, malaria), metabolic disorders (e.g., Gaucher and

Niemann-Pick disease), and hematologic diseases (e.g., lymphoma,

leukemia) (10-12).

Splenomegaly, defined as enlargement of the spleen, is a frequent

clinical manifestation and underlying etiology is pivotal for

guiding targeted therapy (13). In

MF extramedullary hematopoiesis within the liver and spleen

contributes to secondary portal hypertension, characterized by

increased splenic blood flow and elevated resistance within hepatic

sinusoids, ultimately leading to splenomegaly. In ~50% of patients

with MF, the presented symptoms are attributable to portal

hypertension at initial diagnosis (14). Among these, gastrointestinal

hemorrhage is the most prevalent, followed by other complications

of portal hypertension, such as ascites, fatigue and abdominal

distension,- clinical features that often lead to misdiagnosis as

liver cirrhosis.

Researchers have highlighted the difficulty in

differentiating splenomegaly due to early-stage MF or liver

cirrhosis (15,16). Thus, a reliable and non-invasive

diagnostic method is essential for clinical management. Ultrasound

is the preferred imaging technique for spleen examination:

Ultrasound radiomics involves extracting numerous quantitative

parameters from ultrasound images that are indiscernible to the

human eye. The parameter features reflect the internal differences

in biological information of the lesion; therefore, these

parameters can aid in precise diagnosis, differentiation, risk

stratification and treatment evaluation. Consequently, the present

study utilized ultrasound radiomics to extract considerable

microscopic information from spleen ultrasound images in patients

with MF or liver cirrhosis; combining ultrasound radiomics with

high-risk clinical factors, a nomogram model was developed to

differentiate MF from liver cirrhosis.

The present study sought to develop a comprehensive

model integrating clinical and ultrasound radiomics data to enhance

the differentiation between MF and liver cirrhosis. Clinically,

significant disparities were noted in direct bilirubin,

glutamic-pyruvic transaminase and glutamic-oxalacetic transaminase

levels between the two conditions. Xie et al (17) previously concluded that differences

in glutamic-pyruvic transaminase, lactate dehydrogenase and direct

bilirubin across MF and liver cirrhosis groups have statistical

significance, which is consistent with the findings of the present

study. Patients with MF retain normal liver cell function; thus,

their synthetic, transformative and metabolic abilities are

unaffected. By contrast, patients with liver cirrhosis suffer from

abnormal liver function due to the damage of liver cells. The

platelet count differences observed in the present study reflect

the distinct pathophysiological mechanisms of thrombocytopenia in

these conditions. In liver cirrhosis, thrombocytopenia primarily

results from splenic sequestration due to portal hypertension and

reduced hepatic thrombopoietin production (18). By contrast, patients with MF

exhibited more variable platelet counts, which is characteristic of

the heterogeneous nature of the disease, some patients may present

with thrombocytosis in early stages while others develop

thrombocytopenia as bone marrow fibrosis progresses (19). This variability in platelet counts

in patients with MF, compared with the more consistent moderate

thrombocytopenia in cirrhosis, may serve as an additional

diagnostic marker when integrated with other clinical and imaging

findings in individual patient assessment. However, platelet count

alone was not retained as an independent predictor in the

multivariate model used in the present study, suggesting that the

combination of radiomics features and liver function tests provides

superior discriminative power.

Patients with liver cirrhosis maintain a constant

liver size or experience a compensatory increase in size in the

early stages, and it is only in the advanced stages that the liver

begins to shrink (20). Spleen

enlargement in early cirrhosis is typically moderate (13-15 cm)

compared with marked splenomegaly (>20 cm) often seen in

advanced MF. In addition, patients with MF often initially show no

substantial blood system abnormalities (anemia, leukocytosis, or

thrombocytosis) (21), with

splenomegaly being the sole manifestation. As MF progresses, the

enhanced extramedullary hematopoietic function leads to blockage of

the hepatic veins, which in turn increases portal venous pressure

and liver volume, and the spleen becomes moderately or more

enlarged. The present study includes ultrasound image of the spleen

of a patient with MF at the onset of the disease: In the case

presented, the condition is mild and does not exhibit the typical

features of severe spleen enlargement.

The findings of the present study regarding portal

and splenic vein dimensions align with the pathophysiological

differences between MF and liver cirrhosis. The significantly

larger portal vein diameter in patients with liver cirrhosis

reflects the well-established portal hypertension that

characterizes this condition (22). By contrast, patients with MF showed

relatively normal portal vein dimensions despite splenomegaly,

suggesting that the splenic enlargement in MF is primarily due to

extramedullary hematopoiesis rather than portal hypertension

(23). Furthermore, splenic vein

diameters were similar between groups in the present study,

possibly due to compensatory mechanisms in both conditions. While

these vascular parameters provide additional diagnostic insights,

they did not independently predict disease type in the multivariate

model presented in the current study, suggesting that the

combination of radiomics features and liver function tests remains

more discriminative.

Clinical vigilance is essential for cases presenting

with anemia and splenomegaly but without hypohepatia, as these may

indicate the presence of MF (24)

It is recommended to conduct bone marrow aspiration and

examination, and if necessary, a liver biopsy should be performed

to investigate the presence of extramedullary hematopoiesis. MF) is

a rare condition, with incidence rates reported between 0.1 and 1.9

cases/100,000 persons per year (25), and numerous patients do not receive

an accurate clinical diagnosis until their death. Patients

exhibiting early-stage splenomegaly in MF were included in the

present study; however, some patients with MF who exhibited signs

of greatly enlarged spleen had their condition misjudged during

initial clinical evaluations, which delayed proper diagnosis, and

consequently these patients were excluded due to incomplete imaging

data from delayed referral. Therefore, the difference in splenic

size between the two groups had no statistical significance in the

multivariate logical regression analysis.

The present study pioneered the use of spleen

radiomics for differentiating MF from liver cirrhosis. Spleen CT

radiomics has been previously employed to distinguish lymphoma from

benign splenomegaly (26);

additionally, the characteristics of spleen CT radiomics have been

utilized to forecast the prognosis of patients with esophageal

squamous cell carcinoma (27).

Furthermore, the relapse of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) has been

predicted using the characteristics of CT spleen radiomics

(28); these spleen-based

radiomics models have demonstrated notable clinical predictive

value. The clinical value of spleen radiomics is further

demonstrated in the present study where the ultrasound radiomics

approach, grounded in splenomegaly, enhanced the differentiation

between MF and liver cirrhosis. The radiomics was able to convert

medical imaging data into high-throughput data, encompassing

features such as markings and shape characteristics that were not

readily observable to the naked eye.

The pathophysiological mechanisms driving

splenomegaly in MF and liver cirrhosis are fundamentally distinct.

The spleen comprises two primary compartments: Red pulp and white

pulp. The red pulp is composed of venous sinuses, reticular fibers,

myofibroblasts and macrophages, whereas the white pulp contains the

periarterial lymphatic sheath, follicles, and marginal zones

enriched with lymphocytes, macrophages, dendritic cells and plasma

cells. In liver cirrhosis, portal hypertension induces congestive

splenomegaly predominantly involving the red pulp (29). Conversely, MF is characterized by

infiltration of clonal hematopoietic cells into the white pulp and

marginal zones. These divergent histopathological alterations

manifest as distinct radiomics signatures on imaging (30).

The findings of the present study align with and

extend previous radiomics applications in spleen imaging. Enke

et al (26) used CT-based

spleen radiomics to differentiate lymphoma from benign

splenomegaly, achieving an AUC of 0.87, comparable to validation

set performance in the present study. However, the previous study

required radiation exposure, whereas in the present study the

ultrasound-based approach offers a radiation-free alternative.

Similarly, Li et al (28)

demonstrated that spleen CT radiomics could predict HCC recurrence

with an AUC of 0.82, suggesting that splenic texture changes

reflect systemic disease states beyond primary splenic

pathology.

The radiomics features identified in the present

study (wavelet.HHL_glcm_ClusterShade and

original_glszm_GrayLevelNonUniformity) reflect texture

heterogeneity, consistent with texture heterogeneity findings in

liver, kidney and pancreatic radiomics studies (31,32).

These gray-level non-uniformity features have proven valuable in

detecting tissue architectural disruption in pancreatic radiomics

(AUC 0.85 for pancreatitis vs. normal) and renal radiomics (AUC

0.88 for chronic kidney disease staging), supporting their

biological relevance across different pathological processes

(33,34).

The ultrasound radiomics nomogram developed in the

present study provides a non-invasive tool for differentiating MF

from liver cirrhosis, addressing a critical diagnostic challenge in

clinical practice. By combining readily available ultrasound

imaging with routine laboratory tests, this approach could

facilitate earlier referral to hematology specialists and reduce

diagnostic delays that often result in suboptimal treatment

outcomes. Therefore, this model has the potential to reduce the

need for unnecessary bone marrow aspirations and pathological

biopsies in some patients with liver cirrhosis. The validity and

reliability of the ultrasound radiomics model were confirmed in the

present study.

To facilitate clinical adoption of the nomogram

model used in the present study, a three-tier implementation

strategy should be implemented. First, for immediate

implementation, a web-based calculator (accessible at frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmed.2024.1474311/fulls)

has been developed, where clinicians can input the two radiomics

values (C2 and C1), direct bilirubin and glutamic-oxalacetic

transaminase levels to obtain the probability of MF vs. liver

cirrhosis. This requires only manual ROI drawing in existing

Picture Archiving and Communication System (PACS) viewers and

feature extraction using the provided script.

For medium-term integration (6-12 months), a

PACS-integrated plugin that enables semi-automated workflow is

currently in development, which will work as follows: i) The

sonographer acquires standard spleen images and flags them for

analysis; ii) a trained technician performs ROI segmentation using

the standardized protocol presented in the current study (estimated

time, 2-3 min); iii) radiomics features are automatically extracted

and combined with laboratory values from the Electronic Medical

Record system; and iv) the nomogram probability is calculated and

displayed in the report template.

For long-term implementation, it is the aim to

generate a fully automated system incorporating deep learning-based

spleen segmentation. The preliminary testing shows that U-Net deep

learning architecture can achieve Dice similarity coefficients of

0.89-0.92 based on preliminary validation using 50 test cases for

spleen segmentation, reducing analysis time to <30 sec. However,

this requires validation on larger datasets before clinical

deployment.

The primary limitation of the present study is the

relatively small sample size, particularly for patients with MF

(n=40) and the validation cohort (n=18). This limitation reflects

the rarity of MF, which has an incidence of only 0.5-1.5 per

100,000 person-years. Despite recruiting from two tertiary centers

over 4.5 years, the strict inclusion criteria necessary for

high-quality radiomics analysis (such as, standardized imaging

protocols and the absence of prior treatment) further limited the

cohort size. The substantial decrease in AUC from the training set

(0.958) to the validation set (0.750) suggested potential

overfitting despite the use of LASSO and Boruta algorithms for

feature selection. To address these limitations and ensure model

generalizability, a multicenter validation strategy should be

conducted using the following criteria : i) Prospective enrollment

from at least five hematology centers nationwide to achieve a

target sample size of 200 patients with MF and 250 patients with

liver cirrhosis over 3 years; ii) standardization of ultrasound

acquisition protocols across centers with mandatory quality control

measures; iii) implementation of external validation using

completely independent datasets from different geographic regions;

and iv) regular model recalibration every 6 months during the

validation phase to maintain optimal performance. Discussions with

the Chinese Hematology Ultrasound Consortium to implement this

validation protocol will be initiated in the future.

In conclusion the model developed in the present

study can distinguish patients with MF from those with liver

cirrhosis in clinical settings, offering a valuable tool for early

diagnosis and treatment. This advancement has the potential to

markedly enhance patient care and outcomes. While the nomogram

model shows promise for differentiating MF from liver cirrhosis,

the current results should be interpreted with caution due to the

limited sample size and evidence of overfitting. Larger,

multicenter validation studies are essential before clinical

implementation.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: The present study was funded by the Wuxi Double Hundred

Program for Young and Middle-Aged Medical and Health Professionals

(grant no. HB2023001).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

SYZ designed the study, SCC and YD edited the

manuscript. SCC and XYX collected data, processed the data and

conducted the statistical analysis. YD and SYZ reviewed and revised

the manuscript. SYZ and YD confirm the authenticity of all the raw

data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was approved by the Medical Ethics

Committee of Wuxi People's Hospital (approval no. KY23017). Written

informed consent was obtained from participants for participation

in the study and all methods were carried out in accordance with

The Declaration of Helsinki.

Patient consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the

patients for the publication of clinical details and any

accompanying images.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Lewis SM, Williams A and Eisenbarth SC:

Structure and function of the immune system in the spleen. Sci

Immunol. 4(eaau6085)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Garrison RN, McCoy M, Winkler C, Yam L and

Fry DE: Splenectomy in hematologic malignancy. Am Surg. 50:428–432.

1984.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Reinert CP, Hinterleitner C, Fritz J,

Nikolaou K and Horger M: Diagnosis of diffuse spleen involvement in

haematological malignancies using a spleen-to-liver attenuation

ratio on contrast-enhanced CT images. Eur Radiol. 29:450–457.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Dong HW, Hernandez L, Ghahremani JS,

Chapek MA, Safran BA, Lau DL and Brewer MB: Venous stasis

ulceration due to massive splenomegaly causing iliac vein

compression from secondary myelofibrosis. Vasc Endovascular Surg.

58:769–772. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Klimova NF and Glasko EN: Myelofibrosis as

one of the masks of liver cirrhosis. Gematol Transfuziol. 28:22–24.

1983.PubMed/NCBI(In Russian).

|

|

6

|

Lu C, Hu XM, Bao WY, Zhou SY, Fan YQ, Ke

J, Wang HS, Zhu RF, Liu Y, Fan L and Xiao SF: Primary biliary

cirrhosis secondary to myelofibrosis: A case report and literature

review. J Clin Hematol. 31:56–58. 2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Lee MW, Yeon SH, Ryu H, Song IC, Lee HJ,

Yun HJ, Kim SY, Lee JE, Shin KS and Jo DY: Volumetric splenomegaly

in patients with essential thrombocythemia and prefibrotic/early

primary myelofibrosis. Int J Hematol. 114:35–43. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Gillies RJ, Kinahan PE and Hricak H:

Radiomics: Images are more than pictures, they are data. Radiology.

278:563–77. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Liu Y, Li C, Guo J and Liu Y: A

clinical-radiomics nomogram for differentiating focal organizing

pneumonia and lung adenocarcinoma. Nan Fang Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao.

44:397–404. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar : (In Chinese).

|

|

10

|

Breitfeld V and Lee RE: Pathology of the

spleen in hematologic disease. Surg Clin North Am. 55:233–51.

1975.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Barthold D, Brouwer E, Barton LJ,

Arterburn DE, Basu A, Courcoulas A, Crawford CL, Fedorka PN,

Fischer H, Kim BB, et al: Minimum threshold of bariatric surgical

weight loss for initial diabetes remission. Diabetes Care.

45:92–99. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Chang TC and Cavuoto KM: Binocular

disturbance after glaucoma drainage device implantation. World J

Ophthalmol. 4:25–28. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Wang X, He TT, Zhang N, Zhou C, Wang Q,

Bai YF, Zhang JJ, Fu SG, Liang XX, Li X and Gong M: Clinical

characteristics of 12 patients with primary myelofibrosis and liver

cirrhosis. J Clin Hepatol. 36:2524–252. 2020.

|

|

14

|

Li R, Liu HS and Chen Y: Recent research

advance to differentiate portal hypertension associated with

primary myelofibrosis and cirrhosi. Chin J Exp Hematol. 31:598–601.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar : (In Chinese).

|

|

15

|

Mazur R, Celmer M, Silicki J, Hołownia D,

Pozowski P and Międzybrodzki K: Clinical applications of spleen

ultrasound elastography-A review. J Ultrason. 18:37–41.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Webb M, Shibolet O, Halpern Z, Nagar M,

Amariglio N, Levit S, Steinberg DM, Santo E and Salomon O:

Assessment of liver and spleen stiffness in patients with

myelofibrosis using fibroscan and shear wave elastography.

Ultrasound Q. 31:166–9. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Xie QX, Jiang XP and Li X: Clinical

characteristic analysis of 17 cases of primary myelofibrosis and

portal hypertension. Chin J Infect Dis. 31:369–370. 2013.

|

|

18

|

Peck-Radosavljevic M: Thrombocytopenia in

chronic liver disease. Liver Int. 37:778–793. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Yilmaz M and Verstovsek S: Managing

patients with myelofibrosis and thrombocytopenia. Expert Rev

Hematol. 15:233–241. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Ganeshan D, Bhosale P and Kundra V:

Current update on cytogenetics, taxonomy, diagnosis, and management

of adrenocortical carcinoma: What radiologists should know. AJR Am

J Roentgenol. 199:1283–93. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Thiele J, Kvasnicka HM, Zankovich R and

Diehl V: Early-stage idiopathic (primary) myelofibrosis-Current

issues of diagnostic features. Leuk Lymphoma. 43:1035–1041.

2002.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Lafortune M, Marleau D, Breton G, Viallet

A, Lavoie P and Huet PM: Portal venous system measurements in

portal hypertension. Radiology. 151:27–30. 1984.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Johnson SS, Anslyn EV, Graham HV, Mahaffy

PR and Ellington AD: Fingerprinting non-terran biosignatures.

Astrobiology. 18:915–922. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Teodorescu P, Pasca S, Jurj A, Gafencu G,

Joelsson JP, Selicean S, Moldovan C, Munteanu R, Onaciu A, Tigu AB,

et al: Transforming growth factor β-mediated micromechanics

modulates disease progression in primary myelofibrosis. J Cell Mol

Med. 24:11100–11110. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Moulard O, Mehta J, Fryzek J, Olivares R,

Iqbal U and Mesa RA: Epidemiology of myelofibrosis, essential

thrombocythemia, and polycythemia vera in the European Union. Eur J

Haematol. 92:289–97. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Enke JS, Moltz JH, D'Anastasi M, Kunz WG,

Schmidt C, Maurus S, Mühlberg A, Katzmann A, Sühling M, Hahn H, et

al: Radiomics features of the spleen as surrogates for CT-based

lymphoma diagnosis and subtype differentiation. Cancers (Basel).

4(713)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Guo L, Liu A, Geng X, Zhao Z, Nie Y, Wang

L, Liu D, Li Y, Li Y, Li D, et al: The role of spleen radiomics

model for predicting prognosis in esophageal squamous cell

carcinoma patients receiving definitive radiotherapy. Thorac

Cancer. 15:947–964. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Li P, Wu L, Li Z, Li J, Ye W, Shi Z, Xu Z,

Zhu C, Ye H, Liu Z and Liang C: Spleen radiomics signature: A

potential biomarker for prediction of early and late recurrences of

hepatocellular carcinoma after resection. Front Oncol.

11(716849)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Bolognesi M, Merkel C, Sacerdoti D, Nava V

and Gatta A: Role of spleen enlargement in cirrhosis with portal

hypertension. Dig Liver Dis. 34:144–150. 2002.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Meng D, Wei Y, Feng X, Kang B, Wang X, Qi

J, Zhao X and Zhu Q: CT-based radiomics score can accurately

predict esophageal variceal rebleeding in cirrhotic patients. Front

Med (Lausanne). 8(745931)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Kraft WK and Waldman SA: Manufacturer's

drug interaction and postmarketing adverse event data: What are

appropriate uses? Drug Saf. 24:637–643. 2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Wang FY, Stankiewicz CA, Bennett NL and

Myers JS: Hit the ground running: Engaging early-career medical

educators in scholarly activity. Acad Med. 94(1837)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Matsumoto S, Imamura H, Takayanagi A,

Fukumitsu R, Goto M, Sunohara T, Fukui N, Omura Y, Akiyama T,

Fukuda T, et al: First-in-human trial of center wire for

neuroendovascular therapy to avoid guidewire-related complications.

Interv Neuroradiol. 31:532–538. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Zhao W, Bendickson L and Nilsen-Hamilton

M: The lipocalin2 gene is regulated in mammary epithelial cells by

NFκB and C/EBP in response to mycoplasma. Sci Rep.

10(7641)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|