Introduction

Diffuse gliomas are a type of neuroepithelial tumor

characterized by astrocytic or oligodendrocytic morphology and

diffuse infiltrative growth patterns (1). Although rare in children compared

with adults (6 per 100,000 vs. 29 per 100,000, respectively), they

represent the most common solid tumors in pediatric patients

globally (1). The World Health

Organization (WHO) guidelines for the ‘Classification of Tumors of

the Central Nervous System (CNS)’ introduced molecular and

histological/phenotypic information for the first time in

2016(2). However, with

advancements in molecular research, notable differences between

adult and pediatric diffuse glioma have been identified in their

pathogenesis, development, molecular variations and epigenetics

(3). Consequently, the 2016 WHO

CNS classification has limitations.

In response, the 2021 fifth edition of the WHO CNS

tumor classification guidelines (4) incorporated molecular and

histopathological criteria with distinct guidelines that could

categorize and diagnose diffuse glioma into adult and pediatric

types. Despite histopathological similarities, these types exhibit

distinct genetic and molecular profiles, treatments and prognoses

(4). The fifth edition further

subdivided pediatric diffuse low-grade glioma (pDLGG) into four

categories: i) Diffuse astrocytoma, MYB- or MYBL1-altered; ii)

angiocentric glioma (AG); iii) polymorphous low-grade

neuroepithelial tumor of the young (PLNTY) and iv) DLGG, MAPK

pathway-altered. Accurate tumor classification is crucial for

guiding precise treatment, assessing clinical prognosis and

developing new therapies.

LGG is the most common pediatric brain tumor;

however, DLGG with infiltrative margins is relatively rare,

accounting for only 8% of cases (5). Genetic alterations such as BRAF

p.V600E mutations, fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR)

modifications, and MYB or MYBL1 rearrangements are common in pDLGG

(6,7). Diagnostic classification becomes

challenging when there is an overlap of histopathological and

genetic features, especially in tumors without characteristic

histopathological or radiological findings. Differential diagnosis

is particularly difficult with pilocytic astrocytoma (PA), the

glial component of ganglioglioma, pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma

(PXA) and dysembryoplastic neuroepithelial tumor (DNT).

The current study presents a case of pDLGG with

oligodendrocyte-like components that was challenging to diagnose.

This case emphasizes the importance of integrating clinical,

histopathological and molecular features for guiding the management

of pediatric diffuse gliomas.

Case report

Patient details

The patient was an 11-year-old girl who was

diagnosed with generalized epilepsy at 1-year-old. The patient

presented to the Shanghai Sixth People's Hospital (Jinjiang, China)

in July 2024 for evaluation and treatment due to symptoms of

intracranial hypertension, including headache and vomiting. The

patient presented to Jinjiang Municipal Hospital for further

treatment in August 2024. Despite long-term use of antiepileptic

drugs, the patient experienced 4-5 seizures per month. The patient

had no history of brain trauma, central nervous system infection or

cerebrovascular disease, and no family history, and the

neurological examination did not reveal any abnormalities.

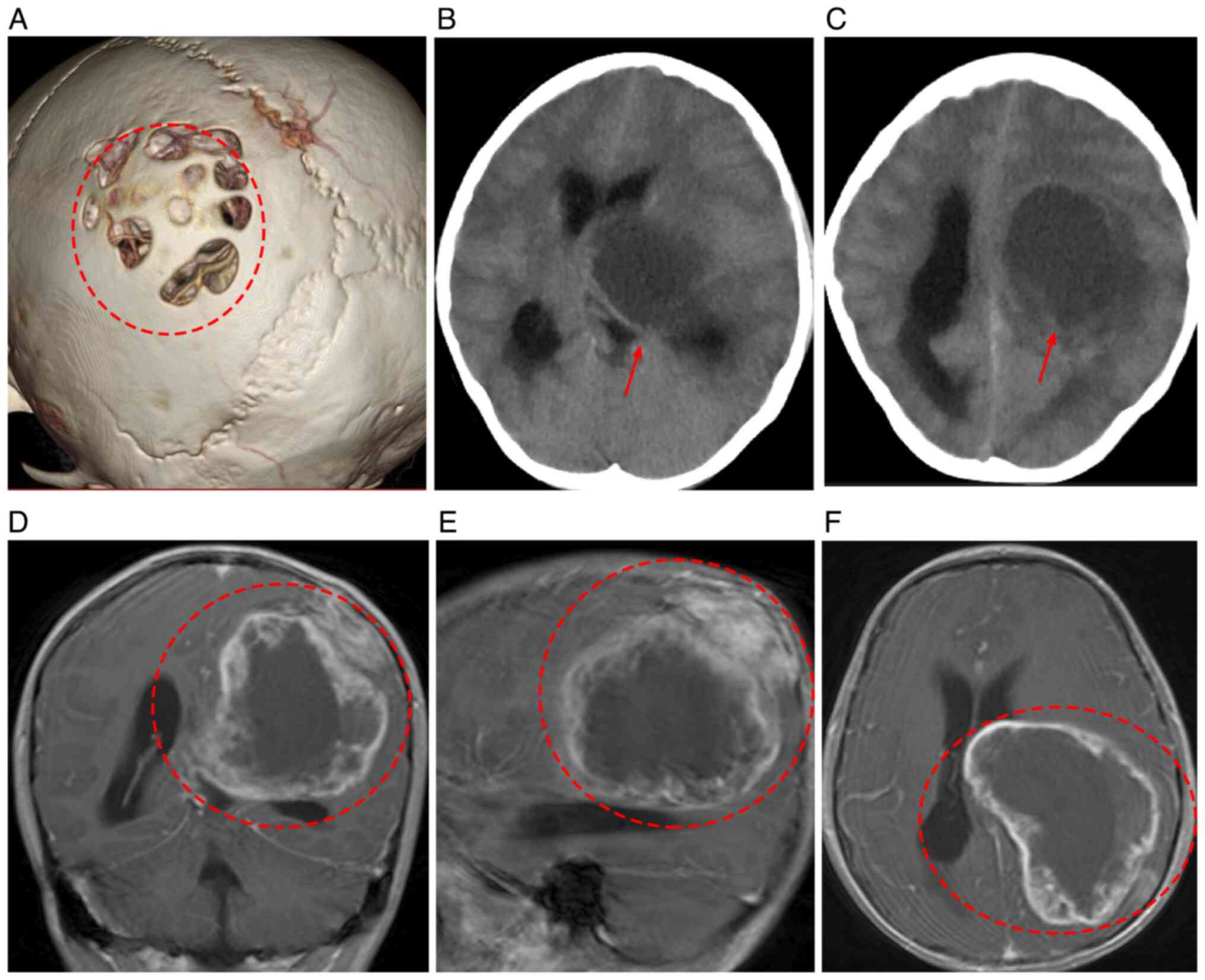

Cranial MRI (Fig.

1) revealed a large lesion (6.9x9.6x6.4 cm) in the left

temporo-parieto-occipital region, predominantly in the parietal

lobe. The lesion exhibited low T1-weighted imaging and high

T2-weighted imaging signals, with fluid-attenuated inversion

recovery showing hyperintensity and diffusion-weighted imaging

showing predominantly hypointense signals. Peripheral enhancement

was observed, along with marked compression of sulci and

ventricles. Cranial CT showed resorptive bone loss in the left

parietal bone without calcification (Fig. 1). Due to the mass effect of the

lesion, ventricular compression and midline shift to the right, the

patient developed consciousness disturbances and coma (Glasgow coma

scale, E1V1M4=6) 2 days after admission (8). Symptoms of brain herniation,

including anisocoria and absent light reflex in the left pupil,

were noted.

Emergency surgery and intraoperative

findings

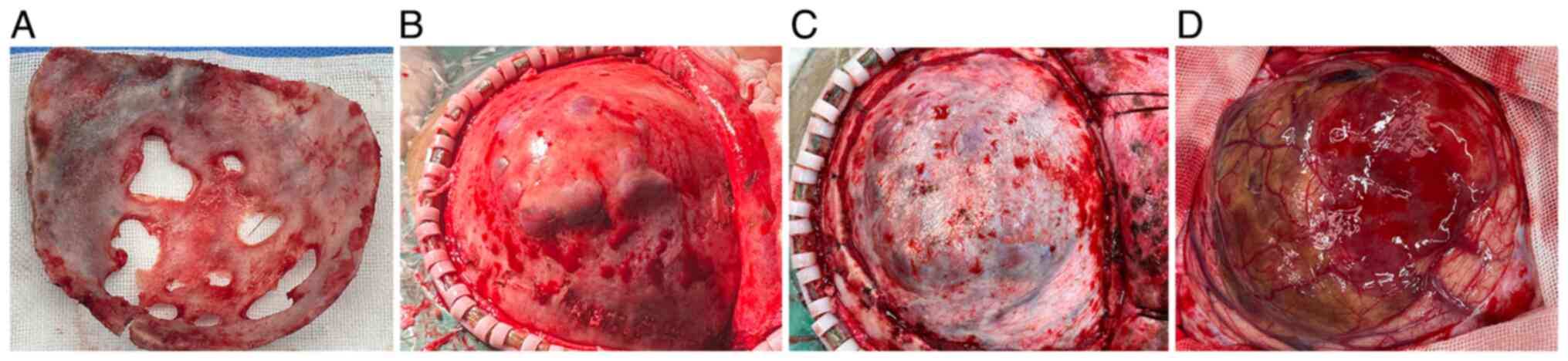

Intraoperatively, the central portion of the

craniotomy window appeared outwardly protruded and thinned due to

tumor compression, with multiple areas of bone destruction

(Fig. 2A). The tumor protruded

onto the cortical surface with the dura mater intact (Fig. 2B and C), the surrounding cortical gyri were

swollen and the sulci were shallow. The tumor was resected in

segments and appeared grayish yellow and grayish red, with a

moderately soft and fibrous consistency (Fig. 2D). The tumor lacked a well-defined

capsule and exhibited unclear boundaries with the surrounding brain

tissue. The tumor was highly vascularized, with areas of necrosis

and hemorrhage (Fig. 2D), and

cystic degeneration was observed in the central portion. The tumor

extended medially to the ventricular trigone, the body of the

lateral ventricle, the internal capsule and the thalamus, and its

dimensions were ~6.5x7.0x10.0 cm. Intraoperative pathological

evaluation suggested features consistent with a LGG.

Postoperative course and

complications

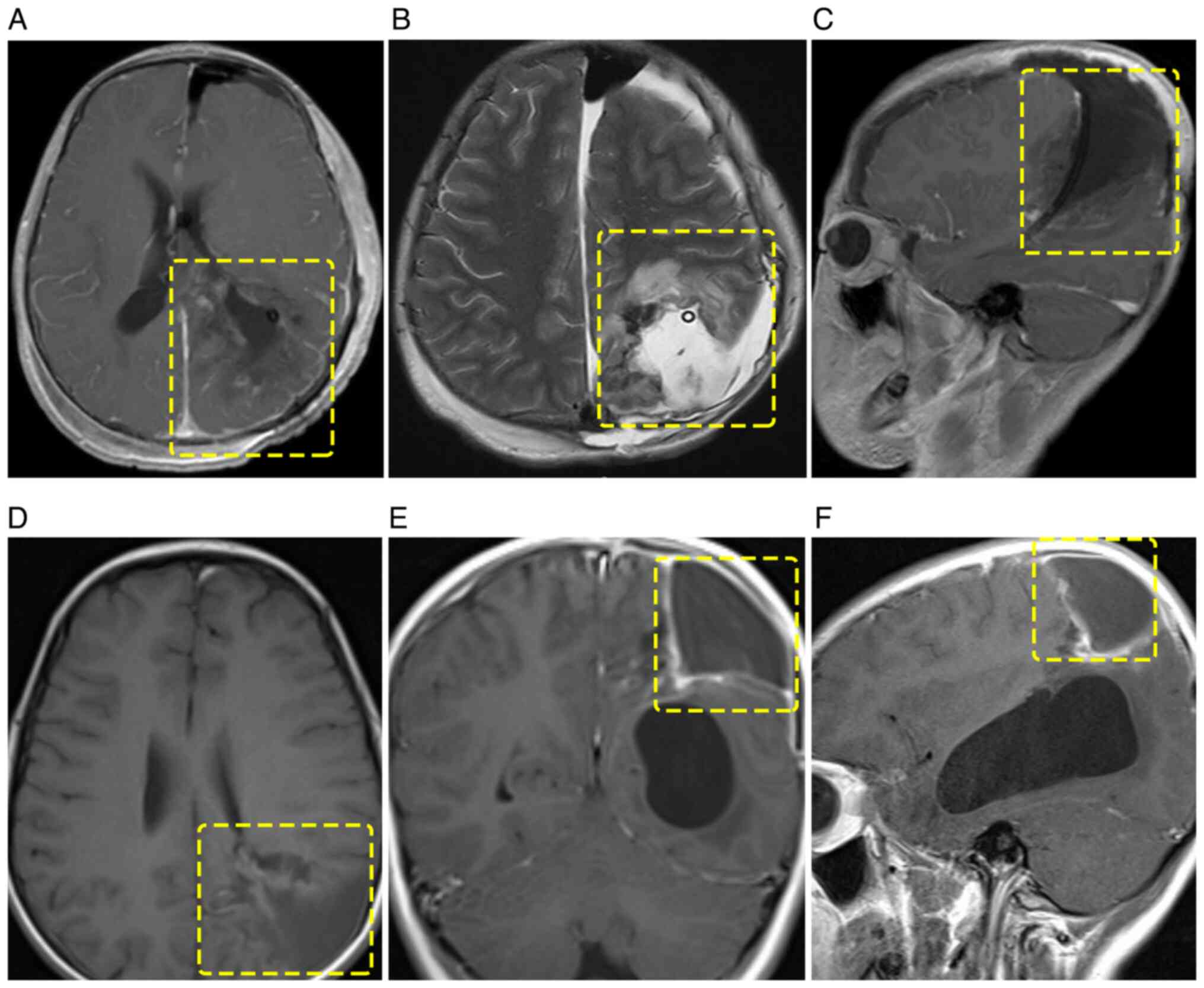

Postoperative cranial MRI confirmed complete tumor

resection (Fig. 3A-C). The patient

was transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU) for observation.

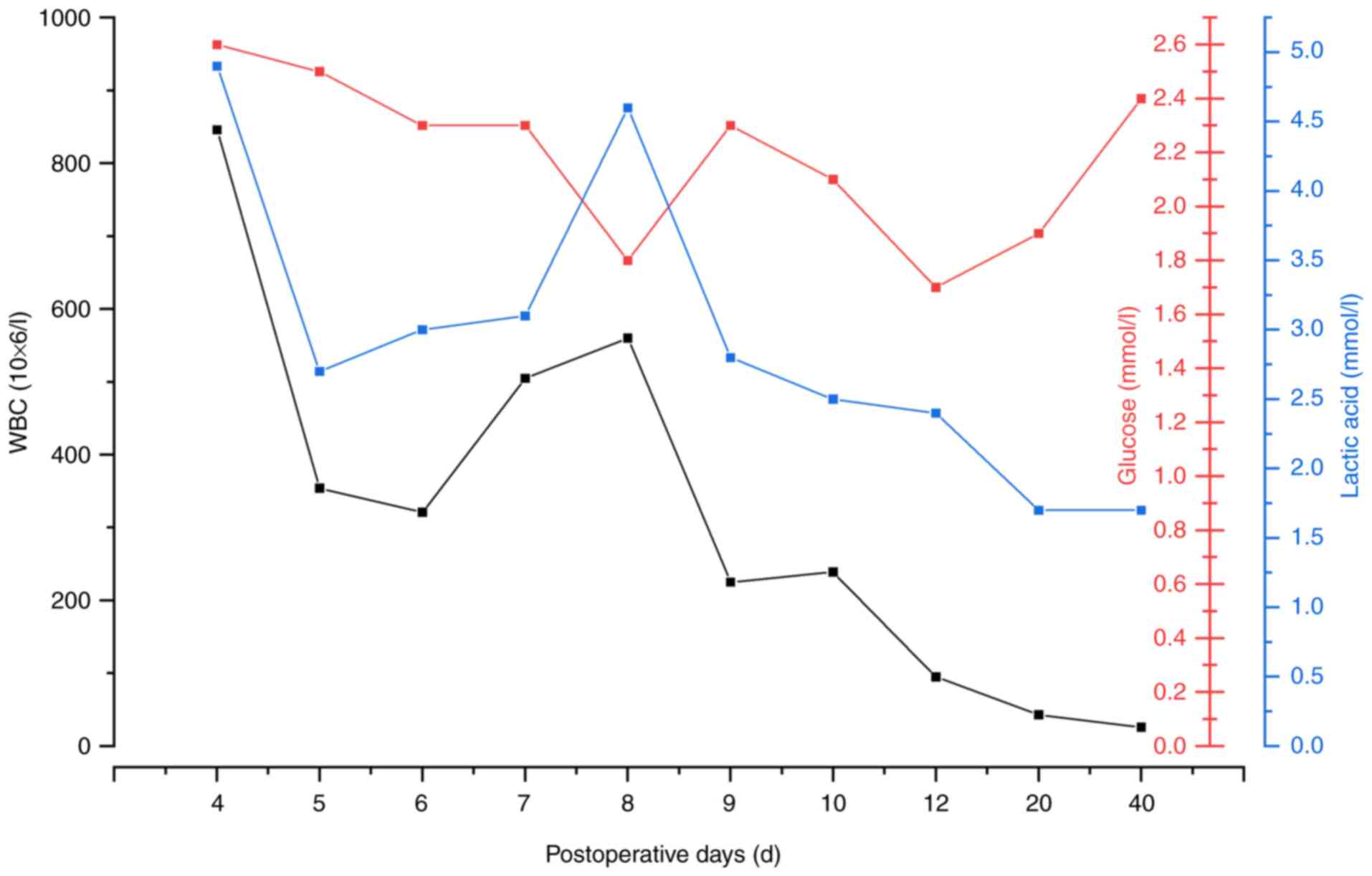

On day 2 post-operation, the patient developed a fever, with a peak

temperature of 40.3˚C. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) appeared yellow

and slightly turbid, with a notable elevated white blood cell

count, glucose and lactate levels (Fig. 4). To identify the causative

pathogen, cerebrospinal fluid bacterial culture was performed. The

culture results confirmed Staphylococcus aureus as the

etiological agent of the intracranial infection. The patient was

treated with a regimen of antibiotics, including

piperacillin-tazobactam (120 mg/kg, every 8 h), vancomycin (20

mg/kg, every 12 h) and meropenem (40 mg/kg, every 8 h). By

postoperative day 11, the condition of the patient had stabilized

and they were consequently transferred out of the ICU.

Histopathological examination

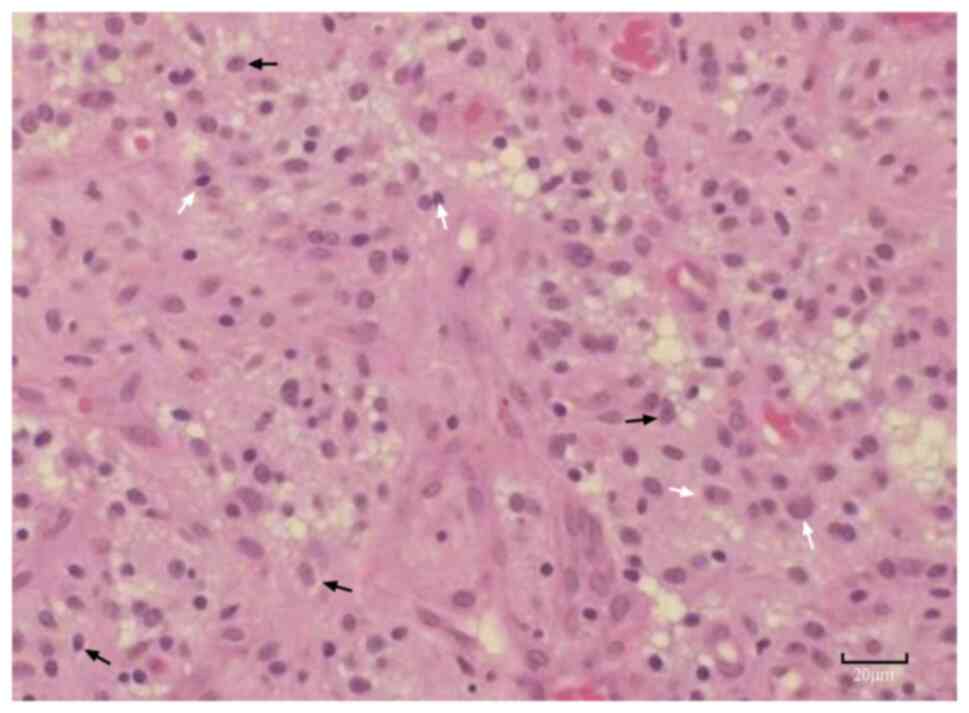

The excised tumor tissue was fixed using 10% neutral

buffered formalin, with fixation performed at room temperature for

24-48 h. After fixation and paraffin embedding, the tissue blocks

were sectioned into slices with a thickness of 4 µm. Hematoxylin

and eosin staining was conducted at room temperature with a

staining duration of 5-10 min for hematoxylin and 1-3 min for

eosin. The staining revealed that the tumor cells exhibited diffuse

infiltrative growth with low to moderate cellular density (Fig. 5). The tumor showed polymorphic

cellular morphology and architecture, forming microcystic and

oligodendroglioma-like astrocytic proliferations. Some areas

displayed spindle-shaped cells, mucinous degeneration,

epithelial-like features and perivascular arrangements. Notable

findings included prominent microvascular proliferation, focal

areas of clear cytoplasm, necrosis and calcification. The tumor

demonstrated moderate cellular proliferation, with mitotic figures

observed at a rate of 2-3 per 10 high-power fields. Focal regions

resembling oligodendroglioma were observed; however, hallmark

features such as Rosenthal fibers, perivascular pseudorosettes and

eosinophilic granular bodies were absent. The morphological

characteristics were consistent with diffuse astrocytoma (9).

Immunohistochemical (IHC) staining and

molecular analysis

For the IHC analyses of the tumor tissue involved in

the present study, the following experimental details were

conducted in accordance with standard pathological procedures and

the information documented in the study. For detecting specific

molecular markers (including glial fibrillary acidic protein,

microtubule-associated protein 2, Olig-2, S-100, vimentin, ATRX,

CD34, and Ki-67), IHC staining was performed at room temperature

for 60 min. All stained sections were observed and analyzed under a

light microscope. Initial IHC staining, including analysis for

GFAP, Ki-67, S-100, Vimentin and CD34, was performed by the

Department of Pathology Service at Jinjiang Municipal Hospital. Due

to the diagnostically challenging nature of the case, an

independent expert consultation was sought from the Pathology

Department of The First Affiliated Hospital of Fujian Medical

University (Fuzhou, China). This secondary consultation encompassed

additional IHC staining for MAP2, Olig-2, and ATRX, as well as

high-throughput tumor sequencing. IHC staining was performed on

formalin-fixed (10% neutral buffered formalin), paraffin-embedded

tissue sections (4-µm thick) as previously described (10). The staining process was conducted

at room temperature for a duration of 60 min. Primary antibodies

included glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP),

microtubule-associated protein 2 (MAP2), Olig-2, S-100, vimentin,

ATRX, CD34 and Ki-67 (Dako, Abcam, and Millipore; dilutions

1:100-1:500) as previously described (10). Appropriate antigen retrieval and

detection procedures were applied. Negative and positive controls

were included in each run.

Tumor cells showed positive staining for GFAP, MAP2,

Olig-2, S-100, vimentin and ATRX, CD34 exhibited focal positivity,

and the Ki-67 proliferation index was ~10%. Analysis by tumor cell

genetic sequencing demonstrated the absence of 1p/19q co-deletion

and chromosome +7/-10 alterations but confirmed the presence of

mutations in BRAF p.V600E, FGFR1 and FGFR4.

Molecular testing

Genomic DNA was extracted from FFPE tumor tissue

using the MagMAX™ FFPE DNA/RNA Ultra Kit (cat. no. A31881; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.). DNA purity and integrity were assessed by

spectrophotometry (NanoDrop 2000; A260/A280 and A260/230 ratios;

NanoDrop Technologies; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and

microcapillary electrophoresis (DNA Integrity Number; Agilent 2100

Bioanalyzer; Agilent Technologies, Inc.). Sequencing libraries were

prepared using the ThruPLEX DNA-seq Kit (cat. no. R400406; Takara

Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) and quantified by qPCR (KAPA Library

Quantification Kit; cat. no. KK4824; Kapa Biosystems; Roche

Diagnostics) to a final loading concentration of 1.2-1.8 nM.

High-throughput sequencing was performed on an Illumina platform

with paired-end 150 bp reads (2x150 bp).

High-throughput sequencing of brain tumor-related

genes revealed mutations in the following genes: ALK, BRCA2, DAXX,

FAT1, FGFR1, FGFR4, MSH2, NRAS, SMO and TSC2 (Table I). Although ATRX IHC staining was

positive, no ATRX mutation was detected via genetic analysis. Given

the higher specificity and reliability of genetic testing, the IHC

finding was considered less definitive. Based on the morphological

and IHC features, the pathology department initially diagnosed the

tumor as a PLNTY. However, considering the genetic analysis

results, the diagnosis of the tumor was revised to a pDLGG with

MAPK pathway alterations.

| Table IHigh-throughput sequencing of mutated

brain tumor-related genes. |

Table I

High-throughput sequencing of mutated

brain tumor-related genes.

| Mutated gene | Mutation type and

location | Mutation abundance,

% |

|---|

| ALK | Missense mutation

in exon 9 | 45.52 |

| BRCA2 | Missense mutation

in exon 11 | 3.92 |

| DAXX | Missense mutation

in exon 5 | 46.7 |

| FAT1 | Missense mutation

in exon 19 | 40.36 |

| FGFR1 | Insertion mutation

in exons 9-18 | 20.72 |

| FGFR4 | Missense mutation

in exon 16 | 52.82 |

| MSH2 | 5' untranslated

region mutation in exon 1 | 63.24 |

| NRAS | Mutation at splice

site in intron 3 | 49.87 |

| SMO | Missense mutation

in exon 12 | 51.0 |

| TSC2 | Missense mutation

in exon 34 | 45.46 |

Follow-up 3 months post-surgery

During the 3-month postoperative follow-up period,

the frequency of seizures in the patient decreased to 1-2 per

month, with periods of no seizures. Therefore, the dosage of

antiepileptic medications was gradually reduced. Repeat

contrast-enhanced MRI showed no residual or recurrent lesions

(Fig. 3D-F).

Discussion

DLGG is the most common brain tumor in children and

adolescents (11,12). When these tumors are located in the

temporal lobe, patients often experience difficult-to-control

seizures, which are resistant to anti-epileptic drugs (13). Since Hughlings Jackson's classic

study in the late 19th century (14), the association between brain tumors

and epilepsy has been well recognized. In 2003, Luyken et al

(15) referred to these tumors as

'long-term epilepsy-associated tumors' (LEATs). LEATs differ from

traditional brain tumors in that they tend to present at a younger

age (seizures are typically the primary and often the only

neurological symptom), grow slowly, are localized to the neocortex

and are often predominantly found in the temporal lobe (16); seizure control is closely

associated with the tumor subtype and the timing of intervention.

In most cases, surgical resection of LEATs yields favorable

outcomes in terms of both seizure reduction and tumor management

(17). Differential diagnoses

include ganglioglioma, DNT, desmoplastic infantile ganglioglioma,

papillary glioneuronal tumor, PA, PXA, AG and PLNTY (18). The patient in the current case

study presented in a similar manner, with seizures as the initial

symptom. The condition was not clearly diagnosed and the patient

suffered from drug-resistant epilepsy for >10 years.

Preoperative imaging did not provide a clear diagnosis, and the

postoperative tumor histopathological features were not

characteristic enough to definitively identify the type of glioma.

Thus, imaging and histopathological features alone could not

establish the definitive glioma type. The importance of

immunohistochemistry and molecular genetic testing is increasingly

apparent in characterizing and refining tumor classification. In

particular, whole-genome DNA methylation analysis and

identification of recurrent genomic alterations (such as mutations,

rearrangements and copy number abnormalities) are essential for

describing biologically distinct disease entities and fine-tuning

tumor classification.

CD34 is a single-chain transmembrane glycoprotein

that is primarily expressed on immature hematopoietic stem cells,

myeloid cells and endothelial cells. It is commonly used as a

marker for certain tumor cells and is widely used to assess LEATs,

glioneuronal lesions and dysplastic cells (19). CD34 is also associated with the

diagnosis of epilepsy-associated tumors (19). CD34 expression is observed in 80%

of ganglioglioma and 84% of PXA cases (18,19).

BRAF p.V600E is an important member of the MAPK pathway that

influences cell proliferation, and BRAF p.V600E mutations,

especially BRAF p.V600E, are commonly seen in glioma subgroups,

including ganglioglioma, PXA, DNT and a subgroup of PA (20,21).

The FGFR family consists of transmembrane tyrosine kinase receptors

(FGFR1-4). Among these, fusions involving FGFR2 and FGFR3 are the

most frequently observed in PLNTY, with FGFR3::TACC3, FGFR2::SHTN1

(KIAA198) and FGFR2::INA fusions being specifically identified

(22).

The case described in the present study was

histologically diagnosed as a diffuse astrocytoma, although despite

improving molecular phenotyping, it was still difficult to

definitively categorize the tumor as a specific LGG. The molecular

markers included Olig-2 positivity, BRAF p.V600E mutation, FGFR1

mutation, FGFR4 mutation and focal CD34 positivity. Notably, there

were no IDH mutations or 1p/19q co-deletions, which led to

differential considerations including oligodendroglioma, PA, PXA,

clear cell ependymoma, ganglioglioma, DNT and PLNTY.

Oligodendrogliomas are typically CD34-negative and exhibit IDH

mutations and 1p/19q co-deletions, which were absent in the tumor.

Oligodendroglioma was initially considered in the differential

diagnosis due to the tumor's low-grade neuroglial morphology;

however, it was ruled out as the tumor lacked the defining IDH

mutation and 1p/19q co-deletion, and was positive for CD34. PA was

excluded due to the lack of Rosenthal fibers and the presence of

focal CD34 expression. PXA and clear cell ependymoma were excluded

based on the positive Olig-2 expression. Diffuse astrocytoma

usually expresses CDKN2A/B, which was absent in the present case.

Ganglioglioma is characterized by MAPK pathway activation gene

alterations, and in high-grade forms, TERT mutations, TP53

mutations, ATRX loss and H3K27M mutations may be detected.

DNT and PLNTY were the most difficult to

differentiate from the tumor in the present case. CD34 may be

positive in the FGFR1 tyrosine kinase fusion or mutation subtype,

but this positivity is limited to a few cells, not as diffuse as in

PLNTY and PLNTY typically shows a Ki-67 expression of <5%

(23). DNT often shows

calcifications on CT, no mass effect or edema, and histologically,

it exhibits oligodendroglioma-like cells arranged in columns with a

microcystic structure, mucinous matrices and scattered dysmorphic

neurons that appear to ‘float’ within the mucinous microcysts. DNT

commonly exhibits FGFR1 gene fusions and BRAF p.V600E mutations

(24). DLGG with MAPK pathway

alterations share similarities with PLNTY, as both are classified

under childhood DLGG. However, in MAPK pathway-altered glioma, CD34

does not show strong diffuse positivity, which differentiates DLGG

from PLNTY (25). Yang et

al (26) categorized DLGG with

MAPK pathway alterations and BRAF p.V600E mutations as intermediate

risk tumors with a high risk of recurrence and progression.

Therefore, based on this information, the current case was

diagnosed as a pDLGG with MAPK pathway alterations. This diagnosis

encourages more frequent follow-up and heightened vigilance in

monitoring for potential changes or complications. Therefore, in

future follow-ups, potential biological evolution should be

assessed in combination with clinical manifestations, imaging

changes and molecular retesting when necessary.

In recent years, with the rapid advancement of

molecular biology techniques, research on pDLGG has shifted its

focus from conventional histopathological classification toward

more refined molecular subtyping (23). The majority of pediatric LGG cases

harbor distinct driver alterations that commonly lead to activation

of the MAPK pathway, along with downstream activation of the

mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling cascade (27-29).

The MAPK pathway, mediated through receptor tyrosine kinases (RTK)

and downstream metabolic and transcriptional effectors, plays a

central role in cellular signal transduction (30). In addition to canonical

alterations, such as the BRAF p.V600E mutation (6,30)

and FGFR fusions (19,31), studies have identified other

genetic events. These events, include TERT promoter mutations,

CDKN2A/B deletions, MYB/MYBL1 rearrangements, and alterations in

NTRK, KRAS and IDH1, also play a notable role in a subset of

pediatric patients with LGG (7,27-28,32).

The role of IDH1 mutations in the formation of pDLGG remains

unclear; however, a recent case series demonstrated that while

patients with IDH1-mutant pDLGG exhibited good short-term survival,

the 5-year progression-free survival rate was 42.9%, and

glioma-related mortality emerged at the 10-year mark (33).

These molecular alterations not only facilitate

precise tumor classification but are also closely associated with

patient prognosis (23,34). Molecular targeted therapies for

patients with pDLGG represent a promising frontier in pediatric

neuro-oncology. Targeting hyperactivation of the Ras-MAPK pathway

has been a major focus of recent research, with Raf and MEK

inhibitors either already approved by the US Food and Drug

Administration or currently under investigation in clinical trials

for patients with pLGG (35,36).

Current research is also investigating the role of mTOR inhibitors

and RTK inhibitors as monotherapies or in combination with other

treatment modalities (37).

In addition, increasing attention has been directed

toward the study of the tumor immune microenvironment (38-41).

Targeted therapies against BRAF-altered tumors have proven to be

highly effective; Sievert et al (42) demonstrated that second-generation

BRAF p.V600E inhibitors, such as PLX PB-3, can successfully target

the KIAA1549-BRAF p.V600E fusion, a result of the 7q34 tandem

duplication, which is particularly dominant in pediatric PA. This

provides a novel therapeutic opportunity for tumors with BRAF

p.V600E mutations, with efficacy dependent on the level of Ras

activation in tumor cells (43).

In the future, multi-omics approaches integrating techniques such

as genetic testing, single-cell RNA sequencing and genomic

structural variations may become crucial for precise tumor

classification and personalized treatment strategies.

Meanwhile, the application of BRAF p.V600E or FGFR

inhibitors (such as vemurafenib, dabrafenib and trametinib) in

pDLGG is being explored in clinical trials and has shown promising

efficacy (35-37,43,44).

Immunotherapy and small-molecule targeted therapies are expected to

offer new treatment options for these tumors, warranting further

attention and investigation.

In conclusion, the present case highlights the

importance of enhancing the recognition of potential low-grade

tumors in pediatric and adolescent patients with temporal lobe

epilepsy in clinical practice, and emphasizes the need for timely

molecular testing to achieve precise diagnosis since

histopathological classification can be challenging. The diagnosis

of DLGG with MAPK pathway alterations, in cases such as that

presented in the present study, remains controversial and

additional evidence-based research is needed to establish risk

stratification and intervention guidelines for these tumors. With

the advancement of targeted therapies, such as those targeting BRAF

p.V600E and FGFR, the treatment of these tumors will become more

precise and individualized, and recognizing molecular abnormalities

will ensure targeted treatment options for future rare cases of

malignant transformation or epilepsy control.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The sequencing data generated in the present study

may be found in the SRA database at the following URL: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/PRJNA1330527. The

other data generated in the present study may be requested from the

corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

PWH conceived the study, and analyzed and

interpreted imaging data. CZC and MYL collected and analyzed

clinical data, and drafted the manuscript. XLG and MFC contributed

to the analysis and interpretation of data, and revised the

manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors

reviewed, discussed, read and approved the final manuscript. CZC

and MYL confirm the authenticity of all the raw data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the

patient's parents for the publication of this case report.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Ferris SP, Hofmann JW, Solomon DA and

Perry A: Characterization of gliomas: From morphology to molecules.

Virchows Arch. 471:257–269. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Louis DN, Perry A, Reifenberger G, von

Deimling A, Figarella-Branger D, Cavenee WK, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD,

Kleihues P and Ellison DW: The 2016 World Health Organization

classification of tumors of the central nervous system: A summary.

Acta Neuropathol. 131:803–820. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Purkait S, Mahajan S, Sharma MC, Sarkar C

and Suri V: Pediatric-type diffuse low grade gliomas:

Histomolecular profile and practical approach to their integrated

diagnosis according to the WHO CNS5 classification. Indian J Pathol

Microbiol. 65 (Suppl):S42–S49. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Patel T, Singh G and Goswami P: Recent

updates in pediatric diffuse glioma classification: Insights and

conclusions from the WHO 5th edition. J Med Life. 17:665–670.

2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Lassaletta A, Zapotocky M, Bouffet E,

Hawkins C and Tabori U: An integrative molecular and genomic

analysis of pediatric hemispheric low-grade gliomas: An update.

Childs Nerv Syst. 32:1789–1797. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Ellison DW, Hawkins C, Jones DTW,

Onar-Thomas A, Pfister SM, Reifenberger G and Louis DN: cIMPACT-NOW

update 4: Diffuse gliomas characterized by MYB, MYBL1, or FGFR1

alterations or BRAFV600E mutation. Acta Neuropathol.

137:683–687. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Suh YY, Lee K, Shim YM, Phi JH, Park CK,

Kim SK, Choi SH, Yun H and Park SH: MYB/MYBL1::QKI fusion-positive

diffuse glioma. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 82:250–260.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Teasdale G and Jennett B: Assessment of

coma and impaired consciousness. A practical scale. Lancet.

2:81–84. 1974.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Wirsching HG, Galanis E and Weller M:

Glioblastoma. Handb Clin Neurol. 134:381–397. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Hu Y, Zhang S, Ye H, Wang G, Chen X and

Zhang Y: Lateral ventricle chordoid meningioma presenting with

inflammatory syndrome in an adult male: A case report. Exp Ther

Med. 25(236)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Pallud J and McKhann GM: Diffuse low-grade

glioma-related epilepsy. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 30:43–54.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

PDQ Pediatric Treatment Editorial Board.

Childhood astrocytomas, other gliomas, and glioneuronal/neuronal

tumors treatment (PDQ®): Health professional version.

In: PDQ Cancer Information Summaries [Internet]. Bethesda (MD):

National Cancer Institute (US), 2002.

|

|

13

|

Lombardi D, Marsh R and de Tribolet N: Low

grade glioma in intractable epilepsy: Lesionectomy versus epilepsy

surgery. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 68:70–74. 1997.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Hughlings-Jackson J: Observations on the

physiology and pathology of hemi-chorea. Edinb Med J. 14:294–303.

1869.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Luyken C, Blümcke I, Fimmers R, Urbach H,

Elger CE, Wiestler OD and Schramm J: The spectrum of long-term

epilepsy-associated tumors: Long-term seizure and tumor outcome and

neurosurgical aspects. Epilepsia. 44:822–830. 2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Thom M, Blümcke I and Aronica E: Long-term

epilepsy-associated tumors. Brain Pathol. 22:350–379.

2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Baticulon RE, Wittayanakorn N and Maixner

W: Low-grade glioma of the temporal lobe and tumor-related epilepsy

in children. Childs Nerv Syst. 40:3085–3098. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Giulioni M, Marucci G, Cossu M, Tassi L,

Bramerio M, Barba C, Buccoliero AM, Vornetti G, Zenesini C,

Consales A, et al: CD34 expression in low-grade epilepsy-associated

tumors: Relationships with clinicopathologic features. World

Neurosurg. 121:e761–e768. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Huse JT, Snuderl M, Jones DTW, Brathwaite

CD, Altman N, Lavi E, Saffery R, Sexton-Oates A, Blumcke I, Capper

D, et al: Polymorphous low-grade neuroepithelial tumor of the young

(PLNTY): An epileptogenic neoplasm with oligodendroglioma-like

components, aberrant CD34 expression, and genetic alterations

involving the MAP kinase pathway. Acta Neuropathol. 133:417–429.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Schindler G, Capper D, Meyer J, Janzarik

W, Omran H, Herold-Mende C, Schmieder K, Wesseling P, Mawrin C,

Hasselblatt M, et al: Analysis of BRAF V600E mutation in 1,320

nervous system tumors reveals high mutation frequencies in

pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma, ganglioglioma and extra-cerebellar

pilocytic astrocytoma. Acta Neuropathol. 121:397–405.

2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Vuong HG, Altibi AMA, Duong UNP, Ngo HTT,

Pham TQ, Fung KM and Hassell L: BRAF mutation is associated with an

improved survival in glioma-a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Mol Neurobiol. 55:3718–3724. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Louis DN, Perry A, Wesseling P, Brat DJ,

Cree IA, Figarella-Branger D, Hawkins C, Ng HK, Pfister SM,

Reifenberger G, et al: The 2021 WHO classification of tumors of the

central nervous system: A summary. Neuro Oncol. 23:1231–1251.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Orhan O, Eray HA, Alpergin BC, Zaimoglu M,

Ozpiskin OM, Aras N, Heper A and Eroglu U: Polymorphous low-grade

neuroepithelial tumor of the young (PLNTY): A case report with

surgical and neuropathological differential diagnosis. Clin

Neuropathol. 43:83–91. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Surrey LF, Jain P, Zhang B, Straka J, Zhao

X, Harding BN, Resnick AC, Storm PB, Buccoliero AM, Genitori L, et

al: Genomic analysis of dysembryoplastic neuroepithelial tumor

spectrum reveals a diversity of molecular alterations dysregulating

the MAPK and PI3K/mTOR pathways. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol.

78:1100–1111. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Ryall S, Zapotocky M, Fukuoka K, Nobre L,

Guerreiro Stucklin A, Bennett J, Siddaway R, Li C, Pajovic S,

Arnoldo A, et al: Integrated molecular and clinical analysis of

1,000 pediatric low-grade gliomas. Cancer Cell. 37:569–583.e5.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Yang RR, Aibaidula A, Wang WW, Chan AK,

Shi ZF, Zhang ZY, Chan DTM, Poon WS, Liu XZ, Li WC, et al:

Pediatric low-grade gliomas can be molecularly stratified for risk.

Acta Neuropathol. 136:641–655. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Zhang J, Wu G, Miller CP, Tatevossian RG,

Dalton JD, Tang B, Orisme W, Punchihewa C, Parker M, Qaddoumi I, et

al: Whole-genome sequencing identifies genetic alterations in

pediatric low-grade gliomas. Nat Genet. 45:602–612. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Jones DTW, Hutter B, Jäger N, Korshunov A,

Kool M, Warnatz HJ, Zichner T, Lambert SR, Ryzhova M, Quang DA, et

al: Recurrent somatic alterations of FGFR1 and NTRK2 in pilocytic

astrocytoma. Nat Genet. 45:927–932. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Bandopadhayay P, Ramkissoon LA, Jain P,

Bergthold G, Wala J, Zeid R, Schumacher SE, Urbanski L, O'Rourke R,

Gibson WJ, et al: MYB-QKI rearrangements in angiocentric glioma

drive tumorigenicity through a tripartite mechanism. Nat Genet.

48:273–282. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Manoharan N, Liu KX, Mueller S, Haas-Kogan

DA and Bandopadhayay P: Pediatric low-grade glioma: Targeted

therapeutics and clinical trials in the molecular era. Neoplasia.

36(100857)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Rivera B, Gayden T, Carrot-Zhang J, Nadaf

J, Boshari T, Faury D, Zeinieh M, Blanc R, Burk DL, Fahiminiya S,

et al: Germline and somatic FGFR1 abnormalities in dysembryoplastic

neuroepithelial tumors. Acta Neuropathol. 131:847–863.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Qaddoumi I, Orisme W, Wen J, Santiago T,

Gupta K, Dalton JD, Tang B, Haupfear K, Punchihewa C, Easton J, et

al: Genetic alterations in uncommon low-grade neuroepithelial

tumors: BRAF, FGFR1, and MYB mutations occur at high frequency and

align with morphology. Acta Neuropathol. 131:833–845.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Yeo KK, Alexandrescu S, Cotter JA,

Vogelzang J, Bhave V, Li MM, Ji J, Benhamida JK, Rosenblum MK, Bale

TA, et al: Multi-institutional study of the frequency, genomic

landscape, and outcome of IDH-mutant glioma in pediatrics. Neuro

Oncol. 25:199–210. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Bale TA and Rosenblum MK: The 2021 WHO

classification of tumors of the central nervous system: An update

on pediatric low-grade gliomas and glioneuronal tumors. Brain

Pathol. 32(e13060)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Kakadia S, Yarlagadda N, Awad R, Kundranda

M, Niu J, Naraev B, Mina L, Dragovich T, Gimbel M and Mahmoud F:

Mechanisms of resistance to BRAF and MEK inhibitors and clinical

update of US food and drug administration-approved targeted therapy

in advanced melanoma. Onco Targets Ther. 11:7095–7107.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Nicolaides T, Nazemi KJ, Crawford J,

Kilburn L, Minturn J, Gajjar A, Gauvain K, Leary S, Dhall G, Aboian

M, et al: Phase I study of vemurafenib in children with recurrent

or progressive BRAFV600E mutant brain tumors: Pacific

pediatric neuro-oncology consortium study (PNOC-002). Oncotarget.

11:1942–1952. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Ullrich NJ, Prabhu SP, Reddy AT, Fisher

MJ, Packer R, Goldman S, Robison NJ, Gutmann DH, Viskochil DH,

Allen JC, et al: A phase II study of continuous oral mTOR inhibitor

everolimus for recurrent, radiographic-progressive

neurofibromatosis type 1-associated pediatric low-grade glioma: A

neurofibromatosis clinical trials consortium study. Neuro Oncol.

22:1527–1535. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

de Visser KE and Joyce JA: The evolving

tumor microenvironment: From cancer initiation to metastatic

outgrowth. Cancer Cell. 41:374–403. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Bejarano L, Jordāo MJC and Joyce JA:

Therapeutic targeting of the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Discov.

11:933–959. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Rajendran S, Hu Y, Canella A, Peterson C,

Gross A, Cam M, Nazzaro M, Haffey A, Serin-Harmanci A, Distefano R,

et al: Single-cell RNA sequencing reveals immunosuppressive myeloid

cell diversity during malignant progression in a murine model of

glioma. Cell Rep. 42(112197)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Jones DTW, Kocialkowski S, Liu L, Pearson

DM, Bäcklund LM, Ichimura K and Collins VP: Tandem duplication

producing a novel oncogenic BRAF fusion gene defines the majority

of pilocytic astrocytomas. Cancer Res. 68:8673–8677.

2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Sievert AJ, Lang SS, Boucher KL, Madsen

PJ, Slaunwhite E, Choudhari N, Kellet M, Storm PB and Resnick AC:

Paradoxical activation and RAF inhibitor resistance of BRAF protein

kinase fusions characterizing pediatric astrocytomas. Proc Natl

Acad Sci USA. 110:5957–5962. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Wang H, Long-Boyle J, Winger BA,

Nicolaides T, Mueller S, Prados M and Ivaturi V: Population

pharmacokinetics of vemurafenib in children with

recurrent/refractory BRAF gene V600E-mutant astrocytomas. J Clin

Pharmacol. 60:1209–1219. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Wen PY, Stein A, van den Bent M, De Greve

J, Wick A, de Vos FYFL, von Bubnoff N, van Linde ME, Lai A, Prager

GW, et al: Dabrafenib plus trametinib in patients with

BRAFV600E-mutant low-grade and high-grade glioma (ROAR):

A multicentre, open-label, single-arm, phase 2, basket trial.

Lancet Oncol. 23:53–64. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|