1. Introduction

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is the most

common and aggressive form of pancreatic cancer, accounting for 85%

of all PDAC cases and representing the seventh leading cause of

cancer globally (1,2). While PDAC predominantly arises from

the ductal epithelium of the pancreas, accumulating evidence

indicates that acinar cells can also undergo acinar-to-ductal

metaplasia and subsequently give rise to PDAC. It is characterized

by rapid progression and resistance to therapy, with a 5-year

survival rate of ~10% (3). PDAC is

frequently diagnosed too late due to heterogeneity in clinical

presentation with high metastatic potential, making PDAC the third

most common cause of cancer-associated mortality in the USA

(4,5).

PDAC is associated with poor prognosis due to a lack

of diagnostic biomarkers, a fibrotic tumor microenvironment,

desmoplasia, and resistance to chemotherapy and immunotherapy

(3,6). Additionally, variability in CA19-9,

including absent expression levels in a subset of patients,

elevation in benign conditions and inconsistent secretion by

tumors, reduces its reliability as a prognostic marker. These

limitations hinder early detection and accurate disease monitoring,

thereby contributing to delayed diagnosis and ultimately poor

prognosis, which restricts its clinical utility for screening

asymptomatic patients (7,8). PDAC management poses notable

challenges due to a stroma rich in hyaluronan, adhesion molecules,

cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) and MMPs, which promote

disease progression and drug resistance (9).

A previous study has highlighted the role of cell

adhesion molecules, including CEA-related cell adhesion molecules

(CEACAMs), in cell-cell and cell-matrix interactions whilst

regulating tumor survival, invasion, metastasis, drug resistance

and progression of PDAC (10).

CEACAMs and integrins can modulate tumor progression through

epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), immune evasion and anoikis

resistance (11). Understanding

the mechanisms and function of adhesion molecules in the fibrotic

and immunosuppressive microenvironment of PDAC is essential for the

development of novel therapeutic targets in PDAC management. The

present review provides an updated and PDAC-specific summary,

highlighting recent mechanistic insights and therapeutic

perspectives.

2. Adhesion molecules can facilitate PDAC

progression

Adhesion molecules, which are frequently upregulated

in cancer, enable tumor cell adhesion, invasion and migration by

activating signals that regulate differentiation, the cell cycle

and survival (12,13). These features render adhesion

molecules potential focal nodes for diagnosis and therapeutic

intervention.

Adhesion molecules typically exhibit unique

characteristics. Unlike numerous adhesion molecules that signal

through direct intracellular interactions through transmembrane and

cytoplasmic domains, CEACAM6, a glycosylphosphatidylinositol

(GPI)-anchored glycoprotein of the immunoglobulin (Ig) superfamily,

lacks both a transmembrane and cytoplasmic domain (14-16).

This enables CEACAM6 to mediate cell-cell and cell-matrix adhesion

through lateral associations with lipid rafts and co-receptors,

promoting PDAC progression (17).

Additionally, it can facilitate tumor cell invasion, motility and

signal transduction, thereby contributing to tumor growth and

metastasis processes in solid malignancies, including colorectal,

breast and gastric cancer (16-20).

CEACAM6 expression varies across different stages of

tumorigenesis, and is modulated by components of the tumor

microenvironment, including collagen, laminin and fibrin (14,16).

However, the dynamic and transient membrane association of CEACAM6,

particularly its localization within lipid rafts and its status as

a GPI-anchored protein lacking an intrinsic signaling domain,

hampers precise delineation of its downstream signaling mechanisms

(21). CEACAM6 is a key target in

PDAC due to its upregulation in the disease, promoting resistance

to anoikis, invasion, metastasis and therapy resistance, and it is

readily accessible as a GPI-anchored cell surface protein, making

it an attractive therapeutic target (17,22).

Nevertheless, it is also essential to understand the roles of

integrins and other adhesion molecules in the management of PDAC

(17-22).

Integrins serve a crucial role in cell

communication, tissue regulation and maintenance (23). In addition, integrins facilitate

tumor progression by mediating interactions between extracellular

matrix (ECM) proteins and cytoplasmic components, potentially

influencing the tumor microenvironment (13,16).

Therefore, understanding the role of integrins in PDAC is crucial

for developing targeted therapies, managing cancer spread, and

optimizing patient outcomes (Fig.

1).

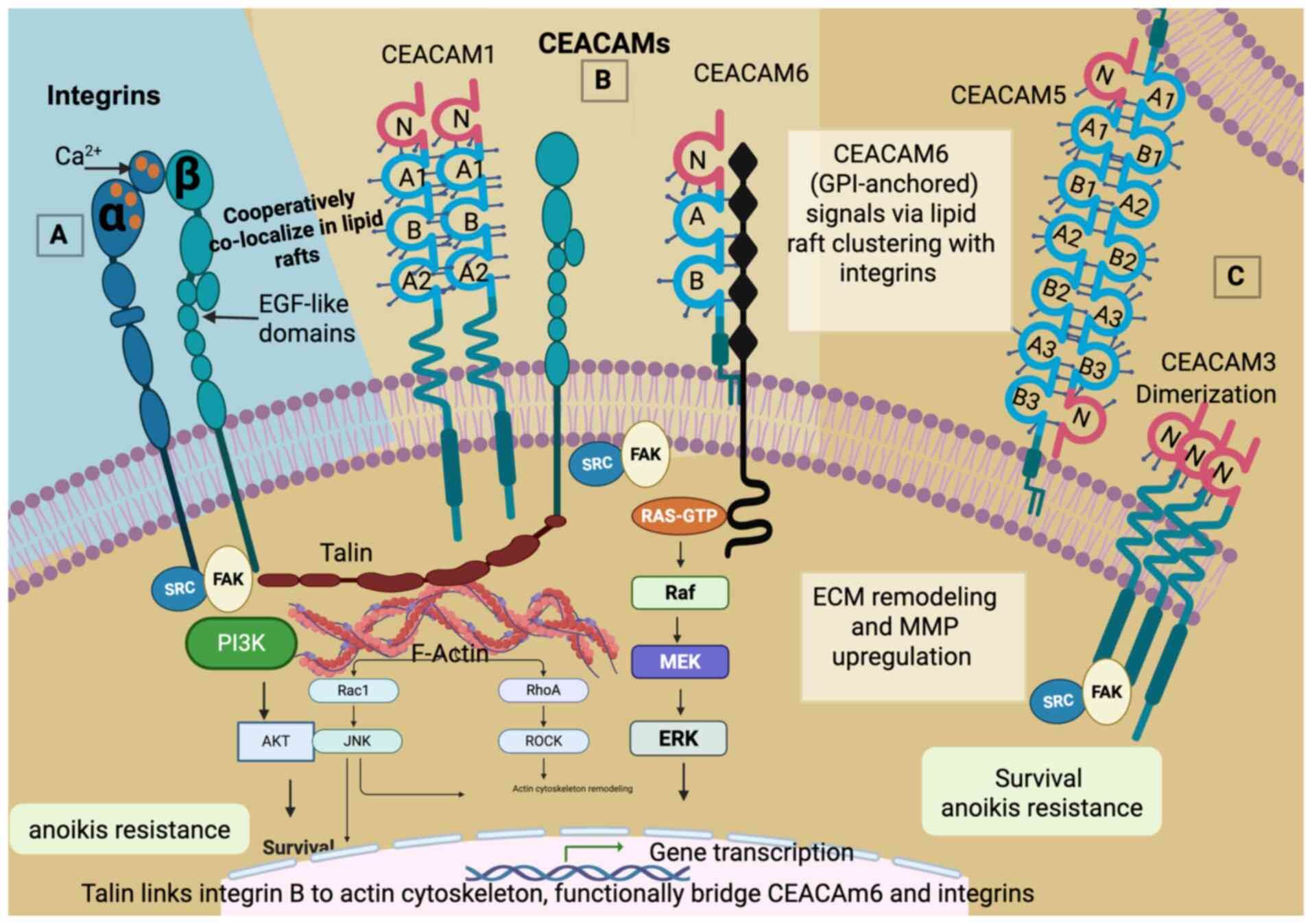

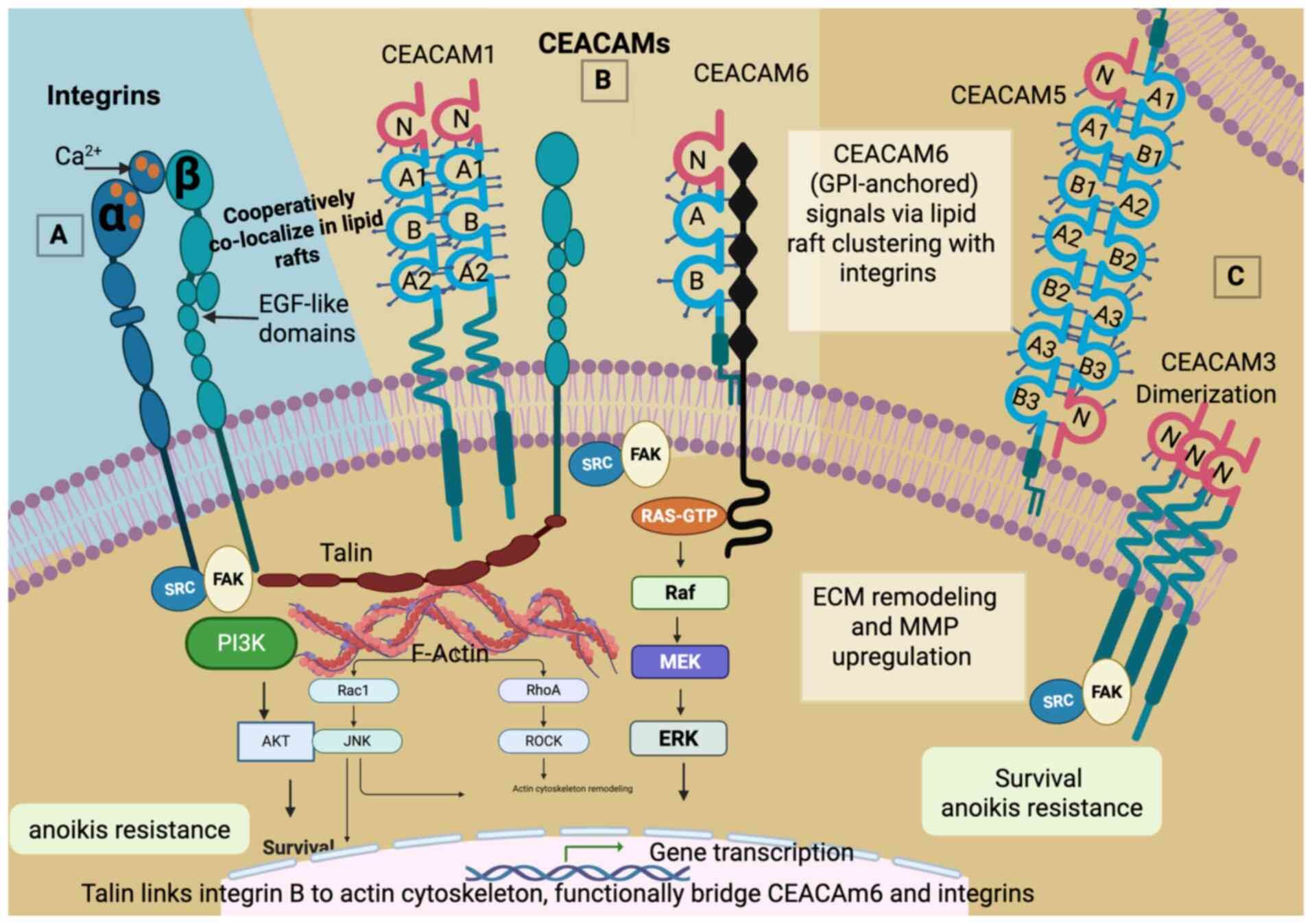

| Figure 1Integrin and CEACAM adhesion

receptors in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. (A) Integrin (left)

receptors with a cytoplasmic domain contain α and β subunits with

EGF-like and calcium-binding domains, which link to intracellular

signaling via talin and focal adhesion kinase (FAK), and (B)

CEACAMs with either a transmembrane receptor anchored by

glycosylphosphatidylinositol on the cell surface, such as CEACAM6

and CEACAM5, or (C) CEACAM receptors with a cytoplasmic domain,

such as CEACAM1 and CEACAM3. Talin is illustrated as a cytoskeletal

adaptor protein that connects integrins to the actin cytoskeleton

and, functionally, to CEACAM-associated signaling hubs. While

direct binding of CEACAMs to talin has not been fully demonstrated,

CEACAMs and integrins co-localize in lipid rafts, enabling shared

downstream signaling via Src/FAK and PI3K/Akt pathways. CEACAM,

carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule; FAK, focal

adhesion kinase; RhoA, Ras homolog family member A; ROCK, Rho

associated protein kinase. |

The present review aims to critically analyze the

oncogenic role of CEACAM6 in PDAC and the mechanisms by which

integrins influs to synthesize evidence on the association between

CEACAMs and integrins in PDAC, focusing on their co-expression,

cross-talk in signaling pathways and combined impact on tumor

progression, invasion and therapy resistance. The review further

discusses how this interplay highlights the potential for

developing targeted therapeutic strategies against these adhesion

molecules (Fig. 1).

3. CEACAMs contribute to PDAC

progression

Ig superfamily and CEACAMs in

PDAC

Ig cell adhesion molecules (IgCAMs), including

calcium-independent glycoproteins, such as CEA, constitute a large

family of cell surface glycoproteins specializing in cell-cell

adhesion (24). CEA, along with

other associated IgCAMs or proteins, are involved in homotypic and

heterotypic interactions, constituting essential diagnostic markers

for various solid tumors, such as colorectal cancer (25).

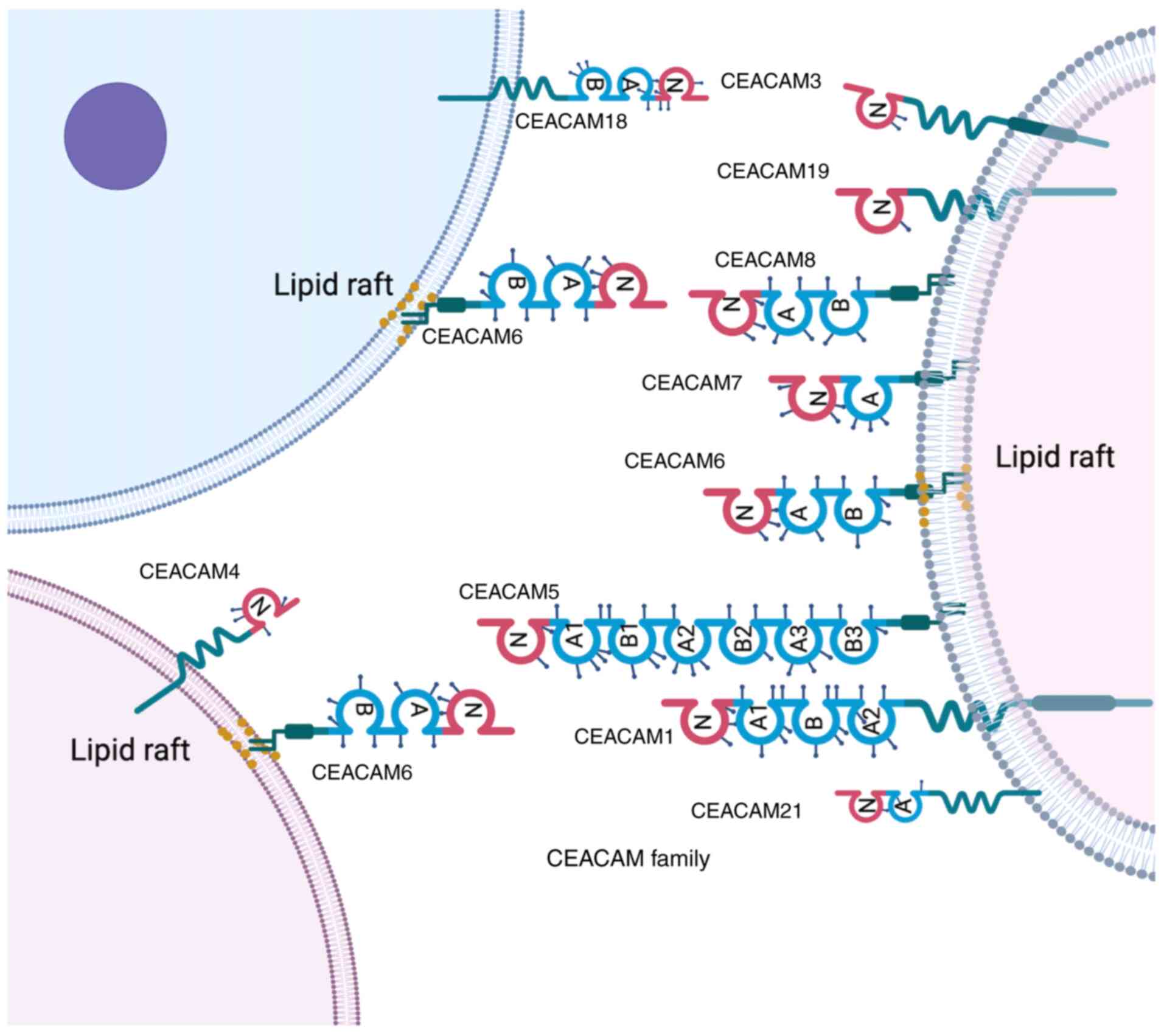

The human CEA family consists of 29 genes, 12 of

which are classified within the CEACAM subgroup (CEACAM1, CEACAM3,

CEACAM4, CEACAM5, CEACAM6, CEACAM7, CEACAM8, CEACAM16, CEACAM18,

CEACAM19, CEACAM20 and CEACAM21), which cluster on the long arm of

chromosome 19(26). Amongst these,

CEACAM1, CEACAM3, CEACAM4, CEACAM6, CEACAM7 and CEACAM8 differ in

their Ig-like domain composition, glycosylation patterns, membrane

anchoring mechanisms and tissue distribution (Fig. 2) (27,28).

Structurally, CEACAMs share an N-terminal Ig variable (IgV)-like

domain followed by constant-like domains (A and B), with extensive

glycosylation accounting for ≤50% of the molecular mass of the

protein (29).

In addition, these proteins are bound to the cell

membrane by either a GPI moiety (CEACAM5, CEACAM6, CEACAM7,

CEACAM8, CEACAM16 and CEACAM18) or a proteinaceous transmembrane

region (CEACAM1, CEACAM3, CEACAM4, CEACAM19, CEACAM20 and CEACAM21)

(Fig. 2) (25,30,31).

This structural diversity influences the functional roles of the

CEACAM subtypes in adhesion, migration and immune modulation in

cancer. However, limited expression of certain CEACAMs in animals

limits their mechanistic investigations (24,32,33).

For example, CEACAM5 and CEACAM6 are highly expressed in humans but

absent in mice, while CEACAM7 and CEACAM8 also lack murine

orthologs, thereby limiting their in vivo study potential

(24,32,33).

CEACAM1

CEACAM1 has a cytoplasmic tail that harbors

immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibition motifs (ITIMs), which are

critical for intracellular signaling (34), and has a molecular weight of ~90

kDa (35). Another feature of

CEACAM1 is the IgV domain that facilitates homophilic and

heterophilic adhesion through complementarity-determining regions

(CDR)-like loops, whilst ITIM phosphorylation recruits Src homology

region 2 domain-containing phosphatase (SHP)-1 (also known as

PTPN6) and SHP-2 (also known as PTPN11), thereby inhibiting T-cell

signaling and supporting immune evasion (34,36).

Previous studies have shown that CEACAM1 is involved in

bidirectional signaling, modulating immune checkpoint regulation

and tumor progression (28,37).

However, it remains under investigation as a prognostic marker

target in PDAC, melanoma, colorectal cancer and non-small cell lung

cancer, and as an emerging immunotherapeutic target across multiple

malignancies (28,37). However, its clinical relevance in

PDAC specifically remains under investigation (38,39).

CEACAM5

CEACAM5, has one IgV domain and six IgC2 domains

(arranged as A1-B1-A2-B2-A3-B3) and a GPI moiety anchored to the

cell membrane (40,41). Furthermore, it has a molecular

weight of 180-200 kDa with extensive N-linked glycosylation

(18,42). CEACAM5 mediates cell-cell adhesion

through its IgV domain and is likely involved in signaling cascades

due to its lipid raft localization (16). By associating with transmembrane

receptors, such as integrins (α5β1, αvβ3), CEACAM1 and EGFR,

CEACAM5 can influence downstream signaling, thereby supporting

metastatic spread and immune evasion (43,44).

Therefore, CEACAM5 has been proposed to be a possible serum

biomarker and target in PDAC immunotherapy in clinical settings

(20,43,45).

CEACAM6

CEACAM6 (also known as CD66c) comprises an

N-terminal IgV domain and two IgC2 domains (A1-B1), forming a

compact three-domain structure that is anchored to the membrane by

a GPI anchor (29). With a

molecular weight of 90-95 kDa, CEACAM6 is heavily glycosylated and

frequently localizes to lipid rafts (28,46).

CEACAM6 lacks a cytoplasmic domain but can facilitate signal

transduction through interactions with various integrin

co-receptors, such as α5β1 and αvβ3, to activate key pathways,

including the focal adhesion kinase (FAK), Src and PI3K/Akt

pathways (16,21,47).

Studies have previously demonstrated that CEACAM6 can promote tumor

cell survival, anoikis resistance and EMT, whilst also contributing

to chemoresistance in pancreatic, colorectal and breast cancer

(16,18-20,22,48).

Through indirect interactions with ECM components, such as

fibronectin and vitronectin, CEACAM6 can also serve a pivotal role

in PDAC invasion and progression (48).

CEACAM7

CEACAM7 consists of an N-terminal IgV domain and two

IgC2 domains (A1-B1), with a GPI anchor facilitating membrane

association (21), and has a

molecular weight of 75-85 kDa (43). Whilst CEACAM7 is generally

considered to be a tumor suppressor in normal epithelial tissues,

it displays oncogenic properties in PDAC (25,49,50).

CEACAM7 mediates both homophilic and heterophilic adhesion,

including interactions with CEACAM6 and integrins, and is involved

in lipid raft-associated signal transduction (49). In addition, CEACAM7 has been

implicated in peritoneal metastasis, is enriched in cancer stem

cell populations, and is a potential early diagnostic and

prognostic marker in PDAC (50).

However, the therapeutic relevance of CEACAM7 is currently under

investigation, including its applications in chimeric antigen

receptor (CAR)-T cell therapy (50).

Integrated structure-function

Within the CEACAM family, the IgV domain is a highly

conserved structural feature that provides adhesive functions

through β-sandwich folds and a CDR-like loop structure (51). However the type of membrane

anchoring varies, with CEACAM1 incorporating a transmembrane helix

allowing direct intracellular signaling, whereas CEACAM5, CEACAM6

and CEACAM7 are GPI-anchored, facilitating dynamic lipid raft

localization and co-receptor engagement (21,52).

By contrast, glycosylation of CEACAM family members influences

protein folding, stability and protease resistance, thereby

contributing to the functional plasticity in tumorigenesis

(29,53).

The IgV domain provides opportunities for

antibody-mediated blockade, since ITIM motifs can be exploited for

immune modulation, whereas GPI anchors may be targeted to disrupt

membrane clustering (54).

Furthermore, the unique structural attributes of each CEACAM

molecule are associated with their distinct roles in PDAC

pathobiology (17,29,53),

offering a framework for biomarker development and personalized

treatment strategies.

CEACAMs are upregulated in PDAC

Members of the CEACAM family, particularly CEACAM1,

CEACAM5, CEACAM6 and CEACAM7, have emerged as key markers of the

pathogenesis of PDAC, influencing diagnosis, prognosis and therapy

(14,53). CEACAM1 has a cytoplasmic tail

containing ITIMs (55) and is

frequently upregulated in PDAC, where it has been proposed as both

a clinical biomarker and a therapeutic target (38-58).

CEACAM1 modulates immune responses through co-inhibitory functions,

particularly by inhibiting T-cell receptor signaling through

SHP-1/2 recruitment, making CEACAM1 a promising target in

immunotherapy (28). However,

previous studies have reported conflicting findings, with CEACAM1

being expressed at lower levels in the tumors of patients with PDAC

compared with in normal pancreatic tissues (59,60).

Furthermore, the roles of CEACAM1 in tumorigenesis and cancer

progression have been inconclusively reported, highlighting the

need for further mechanistic studies (61). CEACAM1 is upregulated in PDAC

tissues and patient serum, and its increased levels are associated

with tumor stage and progression, supporting its potential as a

diagnostic and prognostic biomarker (58). In addition, it has been evaluated

as a non-invasive serum marker (58), with elevated CEACAM1 first reported

in the serum of patients with PDAC. Simeone et al (57) further demonstrated that combining

CEACAM1 with CA19-9 significantly improved sensitivity and

specificity for early-stage PDAC detection. Furthermore,

tissue-based assays revealed that CEACAM1 expression can

distinguish PDAC from chronic pancreatitis and normal pancreatic

tissue, supporting its role as both a serum and tissue biomarker

(57,62). By contrast, high-CEACAM1 expression

is associated with tumor grade, metastatic potential and patient

survival, with functional divergence between isoforms.

Specifically, isoform CEACAM1-L generally suppresses tumor

progression through ITIM-mediated signaling, whereas isoform

CEACAM1-S, lacking ITIM, is often upregulated and linked to

oncogenic behavior (39,62).

Through ITIM-mediated recruitment of SHP-1 and SHP-2

phosphatases, CEACAM1 can downregulate T-cell receptor signaling,

thereby facilitating tumor immune escape (63). In addition, CEACAM1 promotes can

tumor angiogenesis through VEGFR2 pathway activation, thereby

offering opportunities for anti-angiogenic combination therapies

with synergistic potential (59,64).

Monoclonal antibodies neutralizing the inhibitory

effects of CEACAM1 have been assessed, whereas bispecific

antibodies that can target CEACAM1 alongside other checkpoints,

such as TIM3, and small-molecule inhibitors of its downstream

signaling components, including SHP2 inhibitors, Src/FAK inhibitors

and PI3K/Akt or MAPK pathway inhibitors, are actively under

investigation (54,65). Emerging strategies utilizing

CEACAM1-directed CAR-T cell therapies that exploit its

tumor-specific expression profile to achieve targeted cytotoxicity

have also been explored (66,67).

Combinatorial approaches, pairing CEACAM1 inhibition with

chemotherapy, radiotherapy or co-targeting of integrins, may

further enhance therapeutic efficacy by disrupting survival

pathways and modifying the tumor microenvironment (54).

Methodological variability, including differences in

detection techniques, antibody specificity and scoring criteria,

result in heterogeneity in findings on CEACAM1 expression in PDAC

(68). Additionally, intratumoral

heterogeneity further adds to the complexity, with spatially

distinct expression patterns across tumor subclones and stromal

niches (53). The tumor

microenvironment, including immune cell infiltration, stromal

composition and hypoxia, can further influence CEACAM1 expression

and function, underscoring the need for context-specific evaluation

(69,70).

The multifaceted role of CEACAM1 in PDAC supports

its integration into current precision medicine strategies.

Understanding of its involvement in immune regulation, angiogenesis

and cell adhesion should inform the development of targeted

therapies and enable the predictive modeling of treatment outcomes.

Therefore, future research should aim to standardize CEACAM1

detection methods, validate its utility in large patient cohorts

and elucidate isoform-specific mechanisms of action (70).

Similarly, CEACAM5 is involved in cell adhesion,

intracellular signaling, tumor progression and metastasis (71-73).

CEACAM5 can mediate function through homophilic (with itself on

neighboring cells) and through heterophilic interactions with other

CEACAM family members, such as CEACAM6 and CEACAM1(53). CEACAM5 expression is frequently

upregulated in malignancies, including PDAC, where it is localized

to tumor cells and fibrotic or necrotic regions (71-75).

Associations have been reported between CEACAM5 and immune

checkpoint regulation and cancer stemness in PDAC, emphasizing its

potential role as a biomarker and therapeutic target (59).

CEACAM7 has been identified as a potential early

diagnostic and prognostic marker in PDAC (49). Although considered a tumor

suppressor due to its downregulation in several epithelial cancer

types, such as colorectal carcinoma, CEACAM7 expression is

frequently upregulated in PDAC, especially during early

tumorigenesis and in cancer stem cell-enriched populations

(20,75). CEACAM7 has also been implicated in

peritoneal metastasis through interactions with CEACAM6 and

integrin subunit αV (75). Its

dual expression profile and targeting in CAR-T cell study highlight

its complex but important therapeutic potential (50).

CEACAM6/CD66c is a GPI-anchored glycoprotein with a

variable IgV-like domain and two constant domains (A and B),

through which CEACAM6 can form both homo- and heterodimers.

Initially identified in hematological malignancies, CEACAM6 was

later identified as a biomarker for colorectal cancer (17,19,31).

CEACAM6 is expressed on epithelial and leukocyte surfaces (30).

In conclusion, CEACAMs exhibit diverse structural

features and biological functions that can each influence PDAC

development and progression in distinct manners. Their differential

expression patterns and interactions with the tumor

microenvironment offer potential for advancing early detection

strategies and developing targeted therapies.

Pathological role of CEACAM6 in PDAC

diagnosis and progression

CEACAM6 expression is upregulated in PDAC, with a

previous study showing a 20- to 25-fold increase in adenocarcinoma

cells compared with normal pancreatic ductal epithelial cells

(17). Upregulation typically

begins early in pancreatic tumorigenesis, including in pancreatic

intraepithelial neoplasia lesions (1,17),

where it is associated with metastasis and poor prognosis (14,16).

CEACAM6 has been identified to be a prognostic biomarker

independent of KRAS mutation status, and is associated with

aggressive PDAC subtypes (14,76).

In addition, CEACAM6 can promote cell migration,

invasion and proliferation by upregulating MMPs and cyclin D1/CDK4

(53,77). CEACAM6 can facilitate EMT by

promoting loss of epithelial traits and acquisition of mesenchymal

characteristics, which is reflected in its inverse correlation with

E-cadherin expression and its association with increased expression

of mesenchymal markers such as vimentin (73). Mechanistically, miR29 a/b/c

directly targets CEACAM6 mRNA, and their downregulation leads to

CEACAM6 overexpression, thereby enhancing EMT and invasion

(73,74). In addition, CEACAM6 is associated

with anoikis (an apoptotic response triggered by detachment from

the ECM) resistance primarily through enhanced Akt phosphorylation,

which promotes cell survival (47,78).

Supporting this, CEACAM6 inhibition has been reported to increase

cell susceptibility to caspase-mediated anoikis by reducing Akt

phosphorylation (47).

CEACAM6 can support tumor angiogenesis by activating

FAK and paxillin signaling, promoting vasculogenic mimicry

(79). Anti-CEACAM6 antibodies

have been found to reduce MMP9 activity, invasion and angiogenesis

(32). Furthermore, upregulation

of CEACAM6 expression has been observed to contribute to

gemcitabine chemoresistance, whilst its inhibition sensitized cells

to gemcitabine-induced cytotoxicity (80).

Mechanistically, CEACAM6 interacts with ECM

components, such as fibronectin, through α5β1 and αvβ3 integrins,

thereby enhancing anchorage-independent survival (17,47).

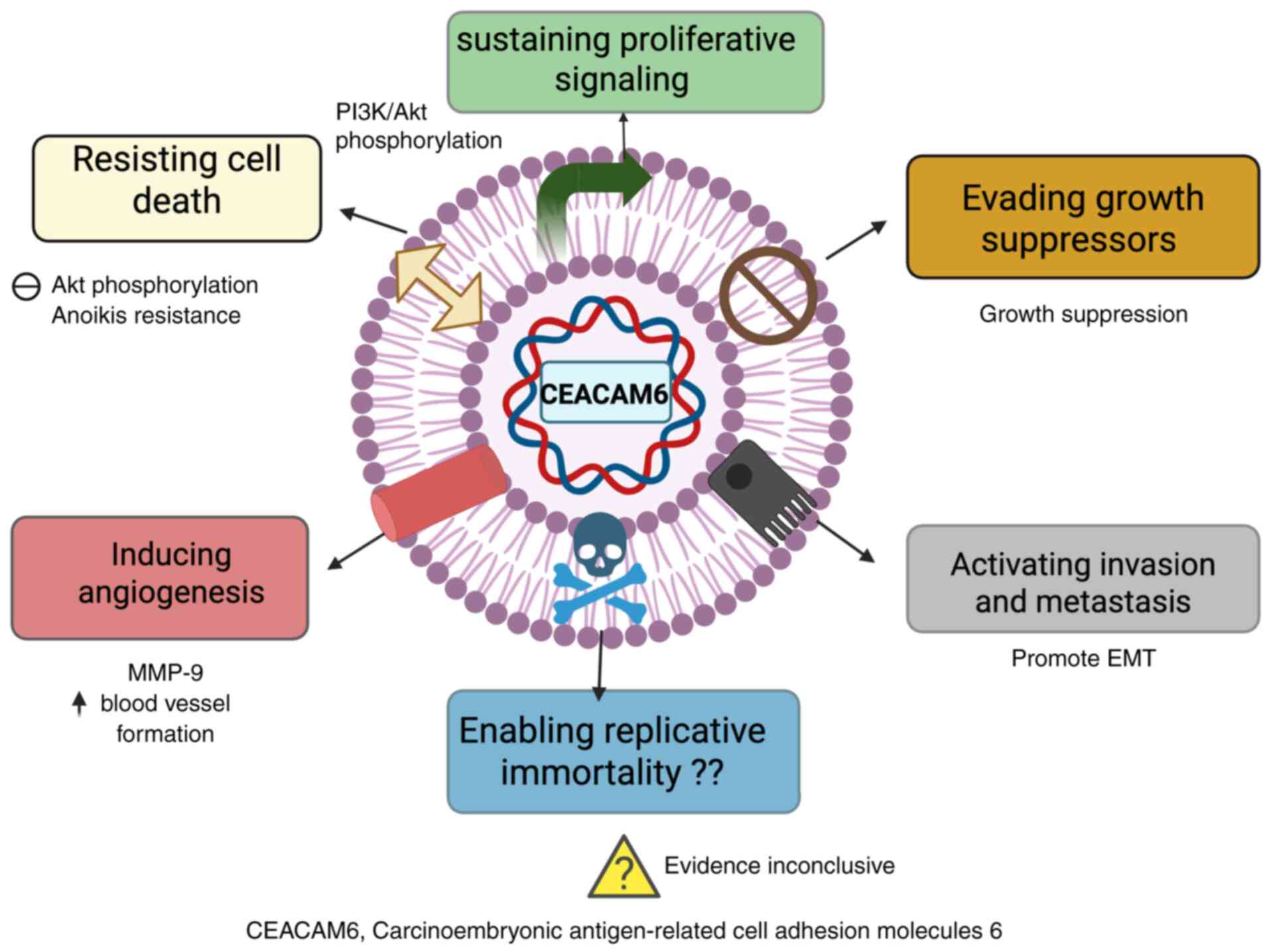

These diverse roles, ranging from EMT and immune evasion to

chemoresistance and angiogenesis, highlight the role of CEACAM6 in

PDAC progression and as a promising therapeutic target (Fig. 3) (81,82).

Role of CEACAM6 in ECM component

interactions

CEACAM6 serves a key role in mediating interactions

with ECM components, influencing PDAC progression, therapeutic

resistance and tumor microenvironment dynamics. Although the

majority of the currently known functional insights stem from

studies in other malignancies, including lung adenocarcinoma, where

CEACAM6 promotes cisplatin resistance and is regulated by miR-146a

and miR-26a, the relevance of CEACAM6 to PDAC is becoming

increasingly evident (83,84).

In the tumor microenvironment, CEACAM6 can modulate

cell adhesion, migration and drug resistance through homotypic and

heterotypic cell-cell interactions involving integrin receptors

(14,17,45).

CEACAM6 activates integrin signaling cascades, particularly those

involving α5β1 and αvβ3 integrins, which are known to interact with

various ECM components, such as laminin, fibronectin, collagen and

hyaluronan (85). These

interactions contribute to anchorage-independent survival, EMT and

chemoresistance in PDAC (14,17).

A previous study has revealed that CEACAM6 can

regulate integrin-mediated signaling through PI3K/Akt activation,

which are mechanisms observed in lung and breast cancer and are

likely conserved in PDAC (16). By

contrast, CEACAM1 has been shown to require tyrosine

phosphorylation for interaction with β3 integrin in melanoma,

suggesting a broader CEACAM-integrin signaling axis (26,86,87).

Despite evidence of oncogenic roles, including

angiogenesis, invasion, resistance to apoptosis and immune evasion,

the molecular mechanisms underlying the interaction of CEACAM6 with

the ECM and the contribution to desmoplastic remodeling in PDAC

remain inadequately characterized (16,73,88-90).

CEACAM6 may influence the fibroinflammatory remodeling of the ECM,

but this desmoplastic interaction remains underexplored (91). Understanding how CEACAM6 interacts

with ECM receptors and regulates PDAC cell behavior is essential.

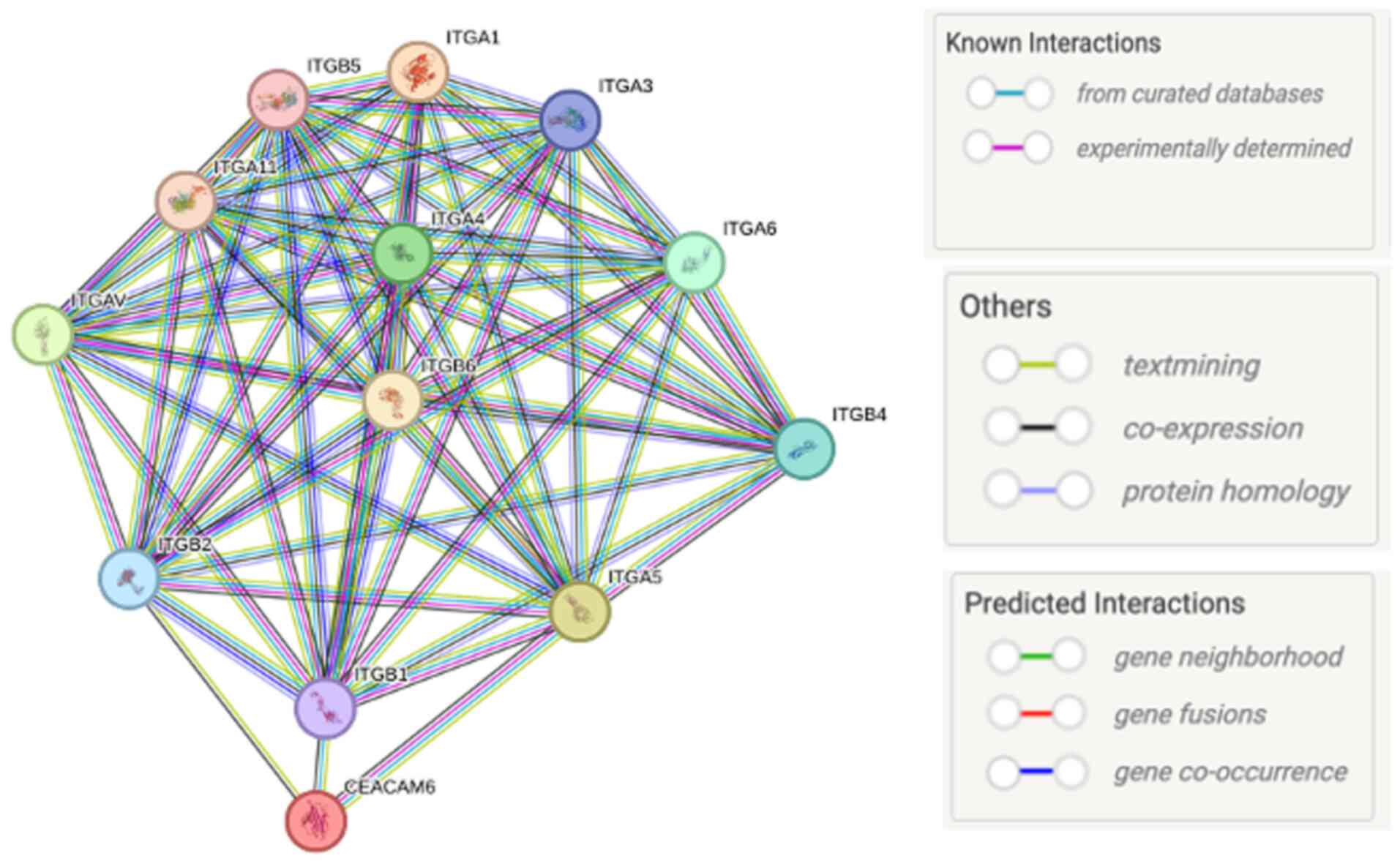

As shown in Fig. 4, STRING-based

protein-protein interaction analysis indicates that CEACAM6 is

connected with multiple integrin subunits [e.g. ITGA5, ITGA2,

ITGB3, integrin β (ITGB)4 and ITGA6], which are key ECM receptors.

These predicated and known associations suggest that CEACAM6 may

influence integrin-mediated adhesion, signaling and ECM remodeling,

thereby supporting its role as both a diagnostic marker and a

therapeutic target in PDAC (Fig.

4).

The desmoplastic reaction in PDAC, marked by dense

collagen deposition, activation of CAFs and altered ECM

composition, is influenced by CEACAM6(14). GPI-anchored localization to lipid

rafts facilitates clustering with integrins α5β1 and αvβ3,

promoting adhesion to fibronectin, collagen I and hyaluronan, and

forming signaling hubs that amplify matrix deposition and tumor

cell survival (16,21). In addition, upregulation of CEACAM6

expression has been found to enhance fibronectin assembly,

stimulate collagen cross-linking and stiffen the ECM (17).

CEACAM6 can also support CAF activation through

α5β1-mediated FAK/Src signaling and TGF-β feedback, thereby

sustaining myofibroblast differentiation (51,92,93).

CEACAM6 upregulates MMP-2 and MMP-9 through the NF-κβ pathway and

increases tissue inhibitors of MMP expression, thereby altering the

proteolytic balance toward ECM accumulation (91). Furthermore, CEACAM6 promotes

mechanotransduction through α5β1 and αvβ3 signaling, reinforcing

fibrosis through Yes-associated protein/WW domain-containing

transcription regulator 1 activation, whilst also driving

hyaluronan accumulation and proteoglycan remodeling, all of which

elevate interstitial fluid pressure and impair drug delivery

(94).

Clinically, CEACAM6-driven desmoplasia can limit

therapy efficacy by creating physical and pharmacological barriers

(14,95). Future studies should explore the

spatial heterogeneity of CEACAM6 expression, identify predictive

biomarkers and optimize anti-desmoplastic interventions for PDAC

management.

4. Integrin and CEACAM involvement in

signaling pathways in PDAC

Integrins are heterodimeric transmembrane receptors

consisting of 18 α and 18 β subunits that combine to form 24

distinct integrin receptors (96).

The structural architecture of integrin subtypes is directly

associated with their functional roles in PDAC progression

(75). Structurally, each subunit

includes a cytoplasmic tail, a transmembrane domain and a large

extracellular region (97). While

the β subunits anchor to the actomyosin cytoskeleton and transmit

intracellular signals, the α subunits mediate selective binding to

ECM proteins, including collagen and laminin (98,99).

These subunits coordinate to form functional integrin receptors

that engage various ECM glycoproteins, such as collagen, laminins

and fibronectin, thereby facilitating bidirectional signaling

between tumor cells and their microenvironment (100).

In PDAC, integrin-mediated signaling can activate

several oncogenic pathways, including the Ras/MAPK, PI3K/Akt and

Rho-GTPase cascades (101,102).

ITGB5 expression, which is upregulated by TGF-β signaling in CAFs,

has been documented to contribute to tumor growth and metastasis.

By contrast, inhibition of TGF-β using LY2157299 in murine models

could reduce ITGB5 expression, leading to smaller tumors and

improved survival (103,104).

Other integrin subtypes also serve distinct roles in

PDAC. Integrin α3 can upregulate the EMT transcription factor zinc

finger E-box binding homeobox 1 (ZEB1) and activate JNK, thereby

promoting chemoresistance and metastasis (105). ITGB4, which is elevated in PDAC,

can also enhance local invasion and metastasis through the

MEK1/ERK1/2 cascade and FAK binding (105-108).

Although ITGB4 is known to facilitate cell migration and invasion,

its precise mechanistic role in PDAC remains to be fully

elucidated. The structural basis for ITGB4 activation involves

tyrosine phosphorylation at Y1510, which induces conformational

changes that facilitate downstream oncogenic signaling and

crosstalk with EGFR pathways. ITGB4 engages in crosstalk with EGFR,

promoting tumor cell proliferation, drug resistance and signaling

interplay central to PDAC pathogenesis (83,109,110).

Beyond the classical integrin subunits, other CEACAM

family members, such as CEACAM1, can contribute to

integrin-associated signaling in PDAC through their roles in immune

modulation, angiogenesis and adhesion regulation (86). CEACAM1 is a valuable clinical

biomarker and a promising therapeutic target in pancreatic cancer

due to its N-terminal IgV-like domain and ≤3 constant C2-like

domains, which enable diverse functional roles in tumor biology

(53). CEACAM1 has been found to

exhibit immunomodulatory functions, where the structural domains

facilitate co-inhibitory activities by inhibiting T-cell receptor

signaling through the recruitment of SHP-1 and SHP-2(87). Importantly, CEACAM1 can also

interact with integrins, such as β2 integrins on immune cells and

β3 integrins on endothelial cells, thereby influencing adhesion and

co-inhibitory signaling (87).

CEACAM1 can promote angiogenesis through the VEGFR2 pathway, which

may inform the development of anti-angiogenic therapeutic

strategies (111).

Despite advances in structural biology, the complete

3D architecture of integrin receptors remains to be fully resolved,

particularly the structural basis for integrin signaling. Further

research into integrin-CEACAM interactions and downstream signaling

mechanisms is essential to understand their role in PDAC

progression and therapeutic resistance.

Integrins as facilitators with other

proteins in PDAC

Integrins are essential mediators of cell-ECM

interactions in PDAC, influencing cell adhesion, migration and

intracellular signaling. By binding to specific ECM proteins,

integrins initiate signal transduction pathways that regulate

cancer progression and therapeutic resistance (112). Certain integrins can also serve

as prognostic biomarkers in PDAC, being associated with disease

severity and patient outcomes (92,93,111,112). For example, high ITGA2 expression

correlates with shorter progression-free and overall survival

times, as well as chemoresistance in PDA (113,114).

Integrins engage in signaling crosstalk with

numerous growth factors and cytokines, including EGF, insulin

growth factor and TGF-β, thereby influencing cellular behavior and

ECM remodeling (115,116). ITGB1 can form heterodimers with

α2, α4 and α5 subunits to mediate focal adhesions between tumor

cells and the ECM (117). By

contrast, cytoplasmic proteins, such as talin and kindlin, can

regulate ligand affinity and integrin activation by linking

integrins to the actin cytoskeleton (113-118).

In addition, as illustrated in Fig.

1, talin may also functionally bridge integrins and CEACAMs

within adhesion complexes. While direct physical binding between

CEACAMs and talin has not been fully demonstrated, experimental

evidence supports integrin-CEACAM co-localization and clustering in

lipid rafts, which facilitates shared downstream signaling through

Src/FAK pathways (16,19,47).

This suggests that integrins and CEACAMs may operate with the same

adhesion and signaling hubs. Integrins, including ITGB3, can be

internalized through clathrin-mediated endocytosis when they are

not under high mechanical tension (119,120).

Within the tumor microenvironment, CAFs can drive

integrin-mediated desmoplasia (121). Integrin αvβ5 regulates the

endocytosis and recycling of active α5β1, which sustains

fibronectin matrix assembly and focal adhesion turnover (122). These processes enhance actomyosin

contractility and ECM stiffening, thereby activating a fibroblast

into myofibroblastic CAF phenotype that maintains ECM remodeling

and promotes disease recurrence (121). Similarly, integrin α11β1 can

mediate CAF-fibronectin interactions, enhancing PDAC cell migration

(122). Integrin α3β1 binds to

laminin-111, collagen I and laminin-332 in the ECM, to facilitate

PDAC cell motility (123).

Targeting integrins in vitro has shown

therapeutic potential. Monoclonal antibodies against α11 integrin

have been developed to disrupt CAF adhesion to collagen and impair

cancer cell invasion (123,124). In 3D models, PDAC cells migrated

along fibroblast extensions using α5β1, which adhered to

fibronectin deposited by CAFs (124). Integrins αvβ3, α5β1 and αvβ5 are

involved in directing tumor invasion and ECM deposition (125). However, the molecular crosstalk

between α11β1 and other integrins in PDAC remains poorly

characterized.

Integrins can also interact with CEACAMs,

co-localizing in lipid rafts where they cluster and modulate

signaling. Specifically, CEACAM1 and CEACAM6 have been reported to

associate with β1 and β4 integrins, enhancing adhesion and survival

pathways in epithelial cancers (19). In PDAC, ITGB4, which influences

tumorigenesis, is activated through tyrosine phosphorylation at

Y1510, regulating downstream MEK1-ERK1/2 signaling (19,108). In addition, ITGB4 expression has

been found to be upregulated in PDAC compared with in normal or

inflamed pancreatic tissues (126). Its activation promotes EMT,

metastasis and chemoresistance, making ITGB4 a potential prognostic

marker (102,127). In gastric cancer, ECM protein 1

promotes metastasis and glycolytic activity through the

ITGB4/FAK/SOX2/hypoxia-inducible factor-1α axis, suggesting a

conserved oncogenic mechanism (126,127).

Additionally, ZEB1 can directly upregulate ITGA3

and ITGB1 by binding to their promoters, contributing to tumor cell

proliferation and migration in PDAC (128). The integration of

integrin-mediated signaling with EMT programs and fibroinflammatory

remodeling emphasizes their role in tumor aggressiveness.

Understanding the function of integrins and their molecular

partners in PDAC is essential for the identification of novel

therapeutic targets. Table I

(74,105,111,129-134).

summarizes the various integrins associated with PDAC pathogenesis

and their functional roles in PDAC.

| Table IDifferent integrins in PDAC and the

distinct functional roles. |

Table I

Different integrins in PDAC and the

distinct functional roles.

| First author/s,

year | Integrin

subtype | Mechanism of

action | Functional

role | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Kemper et

al, 2021 | ITGAV | Mediated by E and P

selectin; high expression of ITGAV activates latent TGF-β and

upregulates TGF-βR1 through the activity of SMAD4. | Upregulation in

selectin deficiency enhances intraperitoneal and pulmonary

metastatic PDAC and drives EMT. | (74) |

| Mia et al,

2021 | ITGβ1 | Binds to TGF-β

receptor 2; signals through focal adhesion molecules and

upregulates pro-fibrotic signaling. | Promotes tumor

growth of PDAC and metastasis through an increase in the expression

of fibronectin or vitronectin; associated with poor patient

survival. | (131) |

| Kuninty et

al, 2019 | ITGA5 | Modulates

TGF-β1/SMAD pathways via focal adhesion kinase pathways. | High ITGA5 in PDAC

is associated with poor overall survival; increases desmoplasia,

decreases tumor perfusion and contributes to gemcitabine

resistance. | (132) |

| Li et al,

2015 | ITGβ6 | Cytoplasmic domain

of ITGβ6 directly binds to ERK2 and increases MAPK activity

(101); ITGB6 induces ETS1

phosphorylation in the ETS-ERK-signaling pathway in the

upregulation of MMP-9(102). | Promotes

proliferation. | (133) |

| Schnittert et

al, 2019 | ITGA11 | Binds to collagen

on the cell surface; Integrin α11 is a receptor of collagen type I

and is upregulated by CAFs; the positive correlation between TGF-β

indicates that the upregulation of ITGA11 may be attributed to

TGF-β, with no clear mechanistic activity. | Promotes cell

metastasis and invasion; regulates pancreatic stellate cell

differentiation into CAFs. | (129) |

| Chen et al,

2022 | ITGA3 | Upregulates

cytokeratin-19 suppresses T-cell activity. ITGA3 interacts with

collagen I and upregulates EGFR signaling via LRIGI induction. | High ITGA3

expression promotes cell invasion and aids tumor cells in evading

apoptosis, and its high expression is associated with a poor

prognosis in PDAC. | (130) |

| Humphries et

al, 2022 | α6β4

(ITGA6/ITGB4) | Interacts with ECM

components, such as fibronectin and laminin. | Formation of

hemidesmosomes is inhibited, allowing α6β4 to act as a signaling

integrin that stimulates tumor progression. | (134) |

| Masugi et

al, 2015 | ITGβ4 | Combines with

several oncogenic receptor tyrosine kinases, including c-Met, ErbB1

and ErbB2, to amplify the signaling pathways that accelerate cancer

invasion. | Involved in

promoting EMT and regulating cancer invasion. | (105) |

| Cavaco et

al, 2018 | α2β1

(ITGA2/ITGB1) | Mediates cancer

cell adhesion to ECM components. | Promotes strong

adhesion of tumor cells to ECM components (e.g., collagen), thereby

supporting PDAC progression. | (111) |

Association between integrins and

CEACAM6 in PDAC

The interplay between CEACAM6 and integrins

contributes to PDAC progression by regulating adhesion, migration

and signaling dynamics within the tumor microenvironment (14,17).

CEACAM6 mediates both homophilic interactions with other CEA family

members and heterophilic interactions with integrins, particularly

αvβ3 and α5β1 (16,17). These interactions facilitate cancer

cell adhesion, invasion, EMT and resistance to anoikis (73,135,136). These interaction between CEACAM

family members and various integrins, supported by both

experimental and predictive evidence, are summarized in Table II (50,74,103,129,137,144-167).

| Table IIAssociation between different CEACAM

members and integrin proteins. |

Table II

Association between different CEACAM

members and integrin proteins.

| First author/s,

year | Association | Integrin

protein | CEACAM member | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Brümmer et

al, 2001 | Interaction between

integrin β3 and a fusion protein containing the

cytoplasmic domain of CEACAM1; cis associations between

integrin β3 and CEACAM1. | β3 | CEACAM1 | (166) |

| Vuijk et al,

2020 | Co-localization at

the cell membrane and highly expressed in pancreatic ductal

adenocarcinoma; co-expressed at the cell membrane and diffusely

expressed in tumor cells and surrounding fibrosis; co-localization

and activation via lipid rafts. | αvβ6; α5β1 | CEACAM5 | (167) |

| Kemper et

al, 2021 | CEACAM7

co-localizes with integrin αV in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma,

facilitating lipid raft–mediated signaling. This interaction

enhances ECM remodeling and supports fibrotic progression. | αV | CEACAM7 | (74) |

| Schnittert et

al, 2018 | Integrin ανβ3

expression is upregulated through CEACAM6 cross-links with

extracellular matrix proteins, fibronectin and vitronectin. In

addition, CEACAM6 co-localizes with integrin α5β1 within the lipid

rafts, where Src kinase-mediated activation of α5β1 enhances

downstream oncogenic signaling | α5β1; ανβ3 | CEACAM6 | (129) |

| Raj et al,

2021 | Fusion of

extracellular Ig variable domain of CEACAM3 and intracellular

domain of integrin β1. | β1 | CEACAM3 | (50) |

CEACAM6 has been implicated in modulating

integrin-dependent signaling, particularly through the activation

of FAK and c-Src kinase pathways, which enhance integrin affinity

for ECM proteins, such as fibronectin and vitronectin (17). In PDAC, CEACAM6 overexpression

upregulates the activation state of α5β1 integrins without altering

receptor abundance, promoting increased fibronectin binding, matrix

assembly, and disruption of normal differentiation and survival

mechanisms (139). Furthermore,

CEACAM6-integrin crosstalk is not limited to cancer but also can

regulate inflammatory and infectious diseases, including the role

of CEACAM6 as a receptor for adherent-invasive E. coli in

Crohn's disease (126),

suggesting its functional versatility across pathologies (20,140). CEACAM6 has also been shown to

facilitate lipid raft-mediated signaling, supporting uptake

mechanisms and the phosphorylation of key downstream effectors,

such as Akt and MAPK, through integrin-linked kinase (ILK)

activation (141,142).

A previous study has demonstrated that clustering

of CEACAM6 on the membrane could promote co-localization with

integrin α5β1, which in turn activated the Akt and MAPK signaling

cascades. This integration of CEA family proteins with integrin

signaling reinforced malignant behaviors, such as enhanced cell-ECM

adhesion, increased invasive capacity and survival under

anchorage-independent conditions (141). Furthermore, STRING network

analysis (Fig. 4) illustrated the

functional protein-protein interaction landscape between CEACAM6

and key integrins. Protein-protein interactions were analyzed using

the STRING database (version 11.5; https://string-db.org/). The query was performed

using Homo sapiens as the organism. Interaction sources included

experimental data, curated databases, co-expression, text mining,

co-occurrence and homology. The confidence score threshold was set

at 0.700 (high confidence). The resulting network was visualized in

STRING, and interaction lines were color-coded based on the

evidence channel (e.g., experimental, co-expression and text

mining).

This bioinformatics representation consolidates

experimental evidence and predictive modeling, reinforcing the

functional relevance of CEACAM6-integrin networks in PDAC

progression.

Mechanistic analysis of

CEACAM6-integrin interactions in PDAC

CEACAM6, a GPI-anchored adhesion molecule, clusters

within lipid rafts and engages integrin receptors, particularly

α5β1 and αvβ3(47). These

interactions enhance integrin avidity for ECM ligands, such as

fibronectin and vitronectin, facilitating stable cell-matrix

adhesion and initiating downstream signal transduction (17). Upon co-localization with integrins,

CEACAM6 promotes the activation of FAK and c-Src, leading to the

phosphorylation of ILK and the subsequent activation of the

PI3K/Akt and MAPK signaling pathways. This dual activation supports

key malignant phenotypes, including sustained proliferation,

survival and invasion (47).

CEACAM6 engages integrins, particularly αvβ3 and

α5β1, to activate Akt signaling, conferring anoikis resistance

under anchorage-independent conditions, a survival effect supported

in multiple models, including colorectal, breast, lung and gastric

cancer, where CEACAM6-driven upregulation of anti-apoptotic

proteins, such as Bcl-2 and survivin (16,51,80,94,136,139). Additionally, CEACAM6 can modulate

ECM remodeling by enhancing the expression and activity of MMP-2

and MMP-9, primarily through FAK- and NF-κB-dependent

transcriptional regulation. This effect is mediated via its

interactions with integrins, particularly α5β1 and αvβ3, which

cluster with CEACAM6 in lipid rafts to activate FAK/Src signaling.

The resulting upregulation of MMPs facilitates the degradation of

the basement membrane, thereby promoting local invasion and

metastatic dissemination (17,142).

CEACAM6-integrin signaling also contributes to EMT

by downregulating E-cadherin and inducing mesenchymal markers, such

as Snail and ZEB1, through the sustained activation of the Akt and

MAPK pathways (143,144). These signaling cascades result in

resistance to gemcitabine and other chemotherapeutic agents

(103,143,144). In addition, CEACAM6-mediated

integrin signaling can increase drug efflux and reinforce survival

pathways, suppressing apoptotic responses to cytotoxic stress

(103). The tumor

microenvironment then further modulates CEACAM6-integrin dynamics.

Increased matrix stiffness, cytokine gradients and altered ECM

composition increase integrin signaling, reinforcing

CEACAM6-mediated oncogenic programs in PDAC (103).

5. Therapeutic targeting of CEACAM6 and

integrins in PDAC

Current therapeutic strategies

CEACAM6 and integrins are promising targets for the

treatment of PDAC due to their roles in tumor adhesion, survival,

invasion and chemoresistance (41). Monoclonal antibodies targeting

CEACAM6 have exhibited preclinical efficacy by disrupting integrin

interactions and downstream signaling pathways, thereby reducing

invasion and metastasis (67).

Similarly, integrin-specific strategies using α5β1 and αvβ3

inhibitors have been shown to impair tumor-ECM interactions and

enhance chemosensitivity (145).

CAR-T therapies targeting CEACAM6 and associated

CEACAM family members, such as CEACAM7, represent an emerging

immunotherapeutic avenue that can overcome the immunosuppressive

microenvironment found in PDAC (146). Combination strategies, pairing

CEACAM6/integrin inhibitors with chemotherapy (gemcitabine) or

matrix-modulating agents, have exhibited synergistic effects and

offer promise in overcoming drug resistance (147).

Clinical trial status and biomarker

validation

Early-phase trials of anti-CEACAM6 antibodies and

antibody-drug conjugates have reported favorable safety and

preliminary efficacy, particularly in patients with high

CEACAM6-urpregulated malignancies, such as colorectal and gastric

cancers. In PDAC, these agents remain at the preclinical stage,

where dual-specificity constructs such as CT109-SN-38 have

demonstrated potent cytotoxicity in a pancreatic cancer model

(148). Integrin inhibitors,

particularly those targeting αvβ3 and α5β1, are currently

undergoing phase I/II evaluation in several solid tumors, including

melanoma, and lung cancer, where combination regimens generally

outperforming monotherapy (149,150). Although clinical data in PDAC

remain limited, a preclinical study suggested that the CEACAM6 and

integrin expression levels are associated with treatment response

(60). Additionally,

CEACAM6-integrin expression profiles may predict chemotherapy

sensitivity, supporting the development of personalized treatment

approaches (17).

Challenges and limitations

Therapeutic resistance remains an important

barrier, mediated by pathway redundancy, tumor heterogeneity and

microenvironmental adaptation (151,152). Subclonal variation in

CEACAM6/integrin expression may lead to incomplete responses,

whilst upregulation of alternative adhesion molecules can bypass

targeted inhibition (153). By

contrast, the desmoplastic and immunosuppressive microenvironment

of PDAC limits drug delivery and the efficacy of immunotherapy

(154,155). Furthermore, variable expression

levels and a lack of standardized cut-off values complicate the

development of biomarkers (60).

6. Clinical translational applications and

future perspectives

Clinical relevance of CEACAM6-integrin

interactions

Although several CEACAM family members have been

implicated in cancer biology, CEACAM6-integrin interactions hold

significant clinical value across early diagnosis, prognosis,

treatment selection and disease monitoring in PDAC (17,57).

CEACAM6 expression is frequently upregulated, by ≤25-fold, in PDAC

tissues and precursor lesions, making it a promising biomarker for

early detection (57,75). High CEACAM6 expression levels are

also associated with aggressive tumor subtypes and poor survival,

serving as an independent prognostic marker regardless of KRAS

status (14,60). This enables risk stratification and

informed decisions on the use of intensified or experimental

therapies and predicts treatment response. Elevated CEACAM6

expression is associated with gemcitabine resistance, whilst

specific integrin expression patterns influence chemotherapy

outcomes, supporting personalized therapeutic strategies (17,156).

Monitoring of circulating CEACAM6 and

integrin-related proteins enables real-time assessment of treatment

efficacy, providing a dynamic alternative to traditional imaging

methods (17,157). Additionally, the strong

association of CEACAM6/integrins with metastasis risk can inform

post-treatment surveillance and the planning of adjuvant therapy

(60).

Translational challenges and

limitations

Translating CEACAM6-integrin research into clinical

application faces several key barriers. A major challenge is the

lack of assay standardization, with varying methodologies across

laboratories hindering reproducibility and cross-study comparison

(158,159). Tumor heterogeneity further

complicates clinical translation, since the expression of CEACAM6

and integrins varies within and between tumors (14,75).

Therefore, single-site biopsies may misrepresent the full molecular

landscape, limiting the accuracy of treatment decisions (160).

The dynamic expression of these molecules during

disease progression and therapy adds complexity, requiring

longitudinal monitoring that may be impractical in routine settings

due to cost and infrastructure constraints (47,161,162). Additionally, unfavorable

regulatory environments, particularly for advanced therapies, such

as CAR-T cell therapies, necessitate specialized clinical trial

designs that can prolong the approval process (163,164).

Future clinical applications

CEACAM6-integrin research is essential in

transforming PDAC management through precision diagnostics,

targeted therapies and real-time monitoring. Molecular profiling of

CEACAM6-integrin expression will enable personalized treatment

selection, guiding choices of chemotherapy, targeted agents or

immunotherapies based on individual tumor characteristics. By

contrast, the emergence of liquid biopsy platforms incorporating

CEACAM6-integrin biomarkers, such as circulating tumor cells,

extracellular vesicles and soluble proteins, offers a non-invasive

method for monitoring disease progression and treatment response,

allowing dynamic, real-time clinical decision-making (166,167).

Integrating CEACAM6-integrin targeting with

immunotherapy or oncolytic virus platforms represents a compelling

strategy to enhance antitumor immune responses by modulating the

tumor microenvironment. In addition, the relevance of

CEACAM6-integrin signaling across multiple tumor types suggests the

potential for pan-cancer therapeutic strategies.

7. Discussion

The present review aimed to highlight the crucial

role of CEACAM6-integrin crosstalk in the pathogenesis of PDAC.

CEACAM6, a GPI-anchored adhesion molecule, is frequently

upregulated in PDAC, which contributes to tumor cell survival,

immune evasion, chemoresistance and desmoplastic remodeling

(14,17). Through lipid raft-mediated

clustering, CEACAM6 co-localizes with integrins, particularly α5β1

and αvβ3, amplifying downstream oncogenic signaling through the

FAK, Src, PI3K/Akt and MAPK pathways (47,48).

The CEACAM6-integrin axis facilitates

anchorage-independent survival, EMT, matrix stiffening and CAF

activation, which are hallmarks of PDAC aggressiveness. These

interactions also contribute to resistance to chemotherapy by

altering drug uptake and activating anti-apoptotic signaling

pathways. CEACAM6-integrin co-expression serves as a prognostic

marker and may guide personalized therapy. High CEACAM6 levels are

associated with poor survival and gemcitabine resistance, whilst

integrin profiles predict responsiveness to combination therapies.

Despite promising therapeutic targets, pathway redundancy, tumor

heterogeneity and assay standardization make PDAC management

challenging.

Therapeutic strategies combining anti-CEACAM6

agents with integrin inhibitors, matrix-degrading enzymes or

immunotherapies show synergistic potential. Additionally, there is

a need to consider integrating CEACAM6-integrin biomarkers into

clinical workflows through liquid biopsy approaches, such as

blood-based assays of circulating tumor cells, extracellular

vesicles or circulating tumor DNA (156-160).

Future studies should explore isoform-specific functions,

protein-protein interactions and temporal expression changes across

disease stages. Mechanistic insights into CEACAM6-integrin

signaling and its impact on ECM remodeling will be crucial for

designing next-generation precision therapies in PDAC.

In conclusion, CEACAM6 and integrins represent

critical regulators of PDAC progression through their influence on

adhesion, survival signaling, desmoplasia and immune modulation.

Their interactions activate oncogenic pathways, such as the FAK,

PI3K/Akt and MAPK pathways, thereby enhancing tumor invasion,

metastasis and therapeutic resistance. The lipid raft-mediated

clustering of CEACAM6 with integrins, such as α5β1 and αvβ3,

reinforces ECM remodeling, chemoresistance and

anchorage-independent survival, whilst integrins themselves

contribute to EMT, angiogenesis and immune evasion. These molecules

shape a tumor microenvironment that is conducive to malignancy and

hinders the effectiveness of therapy.

CEACAM6-integrin dynamics are essential in

precision oncology in PDAC, ranging from biomarker-driven

diagnostics to targeted therapies. Integrating molecular profiling

with emerging treatments, such as CAR-T cells, bispecific

antibodies and matrix-disruptive strategies, may overcome current

limitations posed by tumor heterogeneity, signaling redundancy, and

stromal barriers.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

AAK was responsible for conceptualization,

literature review, drafting, writing, critical revision and final

approval of the manuscript. Data authentication is not applicable.

The author has read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The author declares they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Zińczuk J, Zaręba K, Romaniuk W, Kamińska

D, Nizioł M, Baszun M, Kędra B, Guzińska-Ustymowicz K and

Pryczynicz A: Expression of chosen carcinoembryonic-related cell

adhesion molecules in pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PanIN)

associated with chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic ductal

adenocarcinoma (PDAC). Int J Med Sci. 16:583–592. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Hu JX, Zhao CF, Chen WB, Liu QC, Li QW,

Lin YY and Gao F: Pancreatic cancer: A review of epidemiology,

trend, and risk factors. World J Gastroenterol. 27:4298–4321.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Pereira SP, Oldfield L, Ney A, Hart PA,

Keane MG, Pandol SJ, Li D, Greenhalf W, Jeon CY, Koay EJ, et al:

Early detection of pancreatic cancer. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol.

5:698–710. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Kleeff J, Korc M, Apte M, La Vecchia C,

Johnson CD, Biankin AV, Neale RE, Tempero M, Tuveson DA, Hruban RH

and Neoptolemos JP: Pancreatic cancer. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2:

16022. 2016.

|

|

5

|

Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel

RL, Torre LA and Jemal A: Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN

estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in

185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 68:394–424. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Schober M, Jesenofsky R, Faissner R,

Weidenauer C, Hagmann W, Michl P, Heuchel RL, Haas SL and Löhr JM:

Desmoplasia and chemoresistance in pancreatic cancer. Cancers

(Basel). 6:2137–2154. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Azizian A, Rühlmann F, Krause T, Bernhardt

M, Jo P, König A, Kleiß M, Leha A, Ghadimi M and Gaedcke J: CA19-9

for detecting recurrence of pancreatic cancer. Sci Rep.

10(1332)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Goh SK, Gold G, Christophi C and

Muralidharan V: Serum carbohydrate antigen 19-9 in pancreatic

adenocarcinoma: A mini review for surgeons. ANZ J Surg. 87:987–992.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Moffitt RA, Marayati R, Flate EL, Volmar

KE, Loeza SG, Hoadley KA, Rashid NU, Williams LA, Eaton SC, Chung

AH, et al: Virtual microdissection identifies distinct tumor- and

stroma-specific subtypes of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Nat

Genet. 47:1168–1178. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Tanase CP, Neagu M, Albulescu R and

Hinescu ME: Advances in pancreatic cancer detection. Adv Clin Chem.

51:145–180. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Wang D, Li Y, Ge H, Ghadban T, Reeh M and

Güngör C: The extracellular matrix: A key accomplice of cancer stem

cell migration, metastasis formation, and drug resistance in PDAC.

Cancers (Basel). 14(3998)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Janiszewska M, Primi MC and Izard T: Cell

adhesion in cancer: Beyond the migration of single cells. J Biol

Chem. 295:2495–2505. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Cox TR: The matrix in cancer. Nat Rev

Cancer. 21:217–238. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Pandey R, Zhou M, Islam S, Chen B, Barker

NK, Langlais P, Srivastava A, Luo M, Cooke LS, Weterings E and

Mahadevan D: Carcinoembryonic antigen cell adhesion molecule 6

(CEACAM6) in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDA): An integrative

analysis of a novel therapeutic target. Sci Rep.

9(18347)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Han ZW, Lyv ZW, Cui B, Wang YY, Cheng JT,

Zhang Y, Cai WQ, Zhou Y, Ma ZW, Wang XW, et al: The old CEACAMs

find their new role in tumor immunotherapy. Invest New Drugs.

38:1888–1898. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Johnson B and Mahadevan D: Emerging role

and targeting of carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion

molecule 6 (CEACAM6) in human malignancies. Clin Cancer Drugs.

2:100–111. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Duxbury MS, Ito H, Ashley SW and Whang EE:

c-Src-dependent cross-talk between CEACAM6 and alphavbeta3 integrin

enhances pancreatic adenocarcinoma cell adhesion to extracellular

matrix components. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 317:133–141.

2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Hatakeyama K, Wakabayashi-Nakao K, Ohshima

K, Sakura N, Yamaguchi K and Mochizuki T: Novel protein isoforms of

carcinoembryonic antigen are secreted from pancreatic, gastric and

colorectal cancer cells. BMC Res Notes. 6(381)2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Blumenthal RD, Leon E, Hansen HJ and

Goldenberg DM: Expression patterns of CEACAM5 and CEACAM6 in

primary and metastatic cancers. BMC Cancer. 7(2)2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Zhang Y, Zang M, Li J, Ji J, Zhang J, Liu

X, Qu Y, Su L, Li C, Yu Y, et al: CEACAM6 promotes tumor migration,

invasion, and metastasis in gastric cancer. Acta Biochim Biophys

Sin (Shanghai). 46:283–290. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Tchoupa AK, Schuhmacher T and Hauck CR:

Signaling by epithelial members of the CEACAM family-mucosal

docking sites for pathogenic bacteria. Cell Commun Signal.

12(27)2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Wu G, Wang D, Xiong F, Wang Q, Liu W, Chen

J and Chen Y: The emerging roles of CEACAM6 in human cancer

(Review). Int J Oncol. 64(27)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Valdembri D and Serini G: The roles of

integrins in cancer. Fac Rev. 10(45)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Kuespert K, Pils S and Hauck CR: CEACAMs:

Their role in physiology and pathophysiology. Curr Opin Cell Biol.

18:565–571. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Schölzel S, Zimmermann W, Schwarzkopf G,

Grunert F, Rogaczewski B and Thompson J: Carcinoembryonic antigen

family members CEACAM6 and CEACAM7 are differentially expressed in

normal tissues and oppositely deregulated in hyperplastic

colorectal polyps and early adenomas. Am J Pathol. 156:595–605.

2000.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Zimmermann W and Kammerer R:

Carcinoembryonic antigen. Tumor-Associated Antigens:

Identification, Characterization, and Clinical Applications,

pp201-218, 2009.

|

|

27

|

Gold P and Freedman SO: Specific

carcinoembryonic antigens of the human digestive system. J Exp Med.

122:467–481. 1965.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Gray-Owen SD and Blumberg RS: CEACAM1:

Contact-dependent control of immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 6:433–446.

2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Bonsor DA, Günther S, Beadenkopf R,

Beckett D and Sundberg EJ: Diverse oligomeric states of CEACAM IgV

domains. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 112:13561–13566. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Noworolska A, Harłozińska A, Richter R and

Brodzka W: Non-specific cross-reacting antigen (NCA) in individual

maturation stages of myelocytic cell series. Br J Cancer.

51:371–377. 1985.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Hanenberg H, Baumann M, Quentin I, Nagel

G, Grosse-Wilde H, von Kleist S, Göbel U, Burdach S and Grunert F:

Expression of the CEA gene family members NCA-50/90 and NCA-160

(CD66) in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemias (ALLs) and in

cell lines of B-cell origin. Leukemia. 8:2127–2133. 1994.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Chan CHF and Stanners CP: Novel mouse

model for carcinoembryonic antigen-based therapy. Mol Ther.

9:775–785. 2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Blumenthal RD, Hansen HJ and Goldenberg

DM: Inhibition of adhesion, invasion, and metastasis by antibodies

targeting CEACAM6 (NCA-90) and CEACAM5 (carcinoembryonic antigen).

Cancer Res. 65:8809–8817. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Skubitz KM: The role of CEACAM s in

neutrophil function. Eur J Clin Invest. 54 (Suppl

2)(e14349)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Schumann D, Huang J, Clarke PE, Kirshner

J, Tsai SW, Schumaker VN and Shively JE: Characterization of

recombinant soluble carcinoembryonic antigen cell adhesion molecule

1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 318:227–233. 2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Lu R, Pan H and Shively JE: CEACAM1

negatively regulates IL-1β production in LPS activated neutrophils

by recruiting SHP-1 to a SYK-TLR4-CEACAM1 complex. PLoS Pathog.

8(e1002597)2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Klaile E, Vorontsova O, Sigmundsson K,

Müller MM, Singer BB, Ofverstedt LG, Svensson S, Skoglund U and

Obrink B: The CEACAM1 N-terminal Ig domain mediates cis- and

trans-binding and is essential for allosteric rearrangements of

CEACAM1 microclusters. J Cell Biol. 187:553–567. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Markel G, Achdout H, Katz G, Ling KL,

Salio M, Gruda R, Gazit R, Mizrahi S, Hanna J, Gonen-Gross T, et

al: Biological function of the soluble CEACAM1 protein and

implications in TAP2-deficient patients. Eur J Immunol.

34:2138–2148. 2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Kiriyama S, Yokoyama S, Ueno M, Hayami S,

Ieda J, Yamamoto N, Yamaguchi S, Mitani Y, Nakamura Y, Tani M, et

al: CEACAM1 long cytoplasmic domain isoform is associated with

invasion and recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg

Oncol. 21 (Suppl 4):S505–S514. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Shamsuddin SHB: Biosensors for detection

of colorectal cancer. University of Leeds, 2018.

|

|

41

|

Chan CHF and Stanners CP: Recent advances

in the tumour biology of the GPI-anchored carcinoembryonic antigen

family members CEACAM5 and CEACAM6. Curr Oncol. 14:70–73.

2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Chiang WF, Cheng TM, Chang CC, Pan SH,

Changou CA, Chang TH, Lee KH, Wu SY, Chen YF, Chuang KH, et al:

Carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule 6 (CEACAM6)

promotes EGF receptor signaling of oral squamous cell carcinoma

metastasis via the complex N-glycosylation. Oncogene. 37:116–127.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Swords DS, Firpo MA, Scaife CL and

Mulvihill SJ: Biomarkers in pancreatic adenocarcinoma: Current

perspectives. Onco Targets Ther. 9:7459–7467. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Thomas J, Klebanov A, John S, Miller LS,

Vegesna A, Amdur RL, Bhowmick K and Mishra L: CEACAMS 1, 5, and 6

in disease and cancer: Interactions with pathogens. Genes Cancer.

14:12–29. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Ordonez C, Zhai AB, Camacho-Leal P,

Demarte L, Fan MM and Stanners CP: GPI-anchored CEA family

glycoproteins CEA and CEACAM6 mediate their biological effects

through enhanced integrin alpha5beta1-fibronectin interaction. J

Cell Physiol. 210:757–765. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Kelleher M, Singh R, O'Driscoll CM and

Melgar S: Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEACAM) family members and

inflammatory bowel disease. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 47:21–31.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Al-Khinji A: 122 CEACAM6 molecules mediate

cell adhesion and signaling by modifying integrins in human solid

tumors. J Clin Transl Sci. 9 (Suppl 1)(S35)2025.

|

|

48

|

Zhao D, Cai F, Liu X, Li T, Zhao E, Wang X

and Zheng Z: CEACAM6 expression and function in tumor biology: A

comprehensive review. Discov Oncol. 15(186)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Dhasmana A, Dhasmana S, Kotnala S, Laskar

P, Khan S, Haque S, Jaggi M, Yallapu MM and Chauhan SC: CEACAM7

expression contributes to early events of pancreatic cancer. J Adv

Res. 55:61–72. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Raj D, Nikolaidi M, Garces I, Lorizio D,

Castro NM, Caiafa SG, Moore K, Brown NF, Kocher HM, Duan X, et al:

CEACAM7 is an effective target for CAR T-cell therapy of pancreatic

ductal adenocarcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 27:1538–1552.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Pavlopoulou A and Scorilas A: A

comprehensive phylogenetic and structural analysis of the

carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) gene family. Genome Biol Evol.

6:1314–1326. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Rizeq B, Zakaria Z and Ouhtit A: Towards

understanding the mechanisms of actions of carcinoembryonic

antigen-related cell adhesion molecule 6 in cancer progression.

Cancer Sci. 109:33–42. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Beauchemin N and Arabzadeh A:

Carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecules (CEACAMs)

in cancer progression and metastasis. Cancer Metastasis Rev.

32:643–671. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Zhao L, Li T, Zhou Y, Wang P and Luo L:

Monoclonal antibody targeting CEACAM1 enhanced the response to

anti-PD1 immunotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer. Int

Immunopharmacol. 143(113395)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Singer BB: CEACAMs. In Encyclopedia of

Signaling Molecules. Springer, pp1-9, 2016.

|

|

56

|

Tilki D, Singer BB, Shariat SF, Behrend A,

Fernando M, Irmak S, Buchner A, Hooper AT, Stief CG, Reich O and

Ergün S: CEACAM1: A novel urinary marker for bladder cancer

detection. Eur Urol. 57:648–654. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Simeone DM, Ji B, Banerjee M, Arumugam T,

Li D, Anderson MA, Bamberger AM, Greenson J, Brand RE, Ramachandran

V and Logsdon CD: CEACAM1, a novel serum biomarker for pancreatic

cancer. Pancreas. 34:436–443. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

58

|

Ji B, Simeone D, Ramachandran V, Arumugam

T, Hanash S, Giordano T, Greenson J, Taylor J and Logsdon CD:

CEACAM1 is a biomarker for pancreatic cancer. Pancreas. 29:336–337.

2004.

|

|

59

|

Shi JF, Xu SX, He P and Xi ZH: Expression

of carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule

1(CEACAM1) and its correlation with angiogenesis in gastric cancer.

Pathol Res Pract. 210:473–476. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

60

|

Kurlinkus B, Ger M, Kaupinis A, Jasiunas

E, Valius M and Sileikis A: CEACAM6's role as a chemoresistance and

prognostic biomarker for pancreatic cancer: A comparison of

CEACAM6's diagnostic and prognostic capabilities with those of

CA19-9 and CEA. Life (Basel). 11(542)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

61

|

Qian W, Huang P, Liang X, Chen Y and Guan

B: High expression of carcinoembryonic antigen-associated cell

adhesion molecule 1 is associated with microangiogenesis in

esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Transl Cancer Res. 9:4762–4769.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

62

|

Zhou M, Jin Z, Liu Y, He Y, Du Y, Yang C,

Wang Y, Hu J, Cui L, Gao F and Cao M: Up-regulation of

carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule 1 in

gastrointestinal cancer and its clinical relevance. Acta Biochim

Biophys Sin (Shanghai). 49:737–743. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

63

|

Kim WM, Huang YH, Gandhi A and Blumberg

RS: CEACAM1 structure and function in immunity and its therapeutic

implications. Semin Immunol. 42(101296)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

64

|

Lu R, Kujawski M, Pan H and Shively JE:

Tumor angiogenesis mediated by myeloid cells is negatively

regulated by CEACAM1. Cancer Res. 72:2239–2250. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

65

|

Dong J, Wang B, Wang D, Ni J, Bu T, Wang

H, Nayak B, Wang B, Dong X and Zhang Y: Abstract 2732: NB203: A

novel therapeutic bispecific antibody targeting CEACAM1/VEGF for

tumor immunity and angiogenesis modulation in the tumor

microenvironment. Cancer Res. 84 (6 Suppl)(S2732)2024.

|

|

66

|

Zuo J, Wang Y, Chen Z, Li H, Yang Y, Zhang

Y, Zhang L and Chen J: Development of CEACAM1-specific CAR-T cells

for the treatment of malignant melanoma. Oncol Rep. 49(72)2023.

|

|

67

|

Huang Y, Wang H, Lichtenberger J, Zhang J,

Kappes J and Wu Y: CEACAM1 as a potential therapeutic target in

melanoma and other malignancies. Front Oncol. 9(1072)2019.

|

|

68

|

Partyka K, Maupin KA, Brand RE and Haab

BB: Diverse monoclonal antibodies against the CA 19-9 antigen show

variation in binding specificity with consequences for clinical

interpretation. Proteomics. 12:2212–2220. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

69

|

Yang L, Liu Y, Zhang B, Yu M, Huang F,

Zeng J, Lu Y and Yang C: CEACAM1 is a prognostic biomarker and

correlated with immune cell infiltration in clear cell renal cell

carcinoma. Dis Markers. 2023(3606362)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

70

|

Ligorio M, Sil S, Malagon-Lopez J, Nieman

LT, Misale S, Di Pilato M, Ebright RY, Karabacak MN, Kulkarni AS,

Liu A, et al: Stromal microenvironment shapes the intratumoral

architecture of pancreatic cancer. Cell. 178:160–175.e27.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

71

|

Gisina A, Novikova S, Kim Y, Sidorov D,

Bykasov S, Volchenko N, Kaprin A, Zgoda V, Yarygin K and Lupatov A:

CEACAM5 overexpression is a reliable characteristic of

CD133-positive colorectal cancer stem cells. Cancer Biomark.

32:85–98. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

72

|

Chen J, Li Q, An Y, Lv N, Xue X, Wei J,

Jiang K, Wu J, Gao W, Qian Z, et al: CEACAM6 induces

epithelial-mesenchymal transition and mediates invasion and

metastasis in pancreatic cancer. Int J Oncol. 43:877–885.

2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

73

|

Witzens-Harig M, Hose D, Jünger S,

Pfirschke C, Khandelwal N, Umansky L, Seckinger A, Conrad H,

Brackertz B, Rème T, et al: Tumor cells in multiple myeloma

patients inhibit myeloma-reactive T cells through carcinoembryonic

antigen-related cell adhesion molecule-6. Blood. 121:4493–4503.

2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|