Introduction

In recent years, RNA-based therapeutics, such as

small interfering RNA (siRNA) and messenger RNA (mRNA), have

garnered significant attention, offering new therapeutic approaches

that specifically modulate gene expression associated with various

diseases (1,2). The success of mRNA vaccines against

coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has accelerated the development

of mRNA-based pharmaceuticals. Consequently, mRNA therapeutics are

expected to have broad applications in fields such as cancer

immunotherapy, genome editing, genetic disorder treatments, and

regenerative medicine (3,4).

RNA therapeutics, including mRNA vaccines, require

the carriers for delivery to the targeted tissue. Various mRNA

carriers have been investigated, including cationic polymers,

lipoplexes, lipid-polymer hybrid nanoparticles, and lipid

nanoparticles (5,6). Among these, mRNA/cationic liposome

complexes (mRNA lipoplexes) have been extensively studied as

efficient delivery systems (7).

Lipoplexes are nanoparticles formed by complexation of mRNA and

cationic liposomes (8). Although

mRNA lipoplex-based products have been investigated for clinical

applications such as cancer immunotherapy (7,9),

successful cases remain limited, and further fundamental research

is needed on the lipid compositions and mRNA used in mRNA

lipoplexes.

To comprehensively investigate the efficacy of mRNA

lipoplexes, establishing analytical technologies is essential to

evaluate how differences in lipid composition influence the

efficiency of cellular delivery and gene expression. Achieving this

goal requires a reproducible, high-throughput mRNA transfection

method using multi-well plates in vitro. There are two major

approaches for in vitro mRNA transfection: forward and

reverse. For forward transfection, target cells are first seeded

and cultured, after which a suspension of pre-formed mRNA

lipoplexes is added. Notably, mRNA lipoplexes are typically

prepared immediately before use because mRNA and mRNA lipoplexes

can be unstable in aqueous suspensions and are unsuitable for

long-term storage (10,11). However, this method involves

multiple handling steps and is time-consuming. To address these

limitations, reverse transfection can be utilized to reduce the

labor and time required. In this method, mRNA lipoplexes are

directly mixed with the cell suspension, enabling simultaneous cell

seeding and mRNA transfection without prior cell culture. This

approach (commonly referred to as liquid-phase reverse

transfection) simplifies workflow. However, freshly prepared mRNA

lipoplexes are required, making them unsuitable for comprehensively

evaluating the effects of a wide variety of lipoplexes and mRNA. To

overcome these challenges, we propose the use of solid-phase

reverse transfection. In this method, mRNA lipoplexes are

pre-applied and lyophilized onto the surface of the culture plate

prior to cell seeding. The cell suspension is then directly added

to the dried mRNA lipoplexes, allowing for mRNA transfection upon

contact. The advantages of this approach include reduced manual

handling, compatibility with automation, and the ability to prepare

large batches of transfection-ready plates. Consequently, this

method facilitates the efficient and scalable screening of lipid

components for mRNA transfection into cells.

We previously reported a method for solid-phase

reverse transfection using lyophilized siRNA lipoplexes (12). Additionally, several studies have

investigated lyophilization conditions for plasmid DNA or siRNA

lipoplexes (13,14). However, little is known about the

effects of lyophilization on mRNA lipoplexes. In our previous

study, we demonstrated that the gene-silencing activity of siRNA

lipoplexes could be preserved regardless of the type of cationic

lipid used by employing disaccharides such as sucrose or trehalose

as cryoprotectants during lyophilization (15). However, whether the same strategy

can be applicable to mRNA lipoplexes remains unclear. To

investigate the impact of disaccharides and cationic lipid types on

the transfection efficiency of lyophilized mRNA lipoplexes,

cationic liposomes were prepared using five types of dialkyl or

trialkyl cationic lipids. Lyophilized mRNA lipoplexes were then

prepared in multi-well plates in the presence of trehalose or

sucrose solutions, and their transfection efficiency was evaluated,

in addition to the retention of transfection activity after

long-term storage.

Materials and methods

Materials

11-((1,3-Bis(dodecanoyloxy)-2-((dodecanoyloxy)methyl) propan-2-yl)

amino)-N,N,N-trimethyl-11-oxoundecan-1-aminium

bromide (cat. no. TC-1-12),

2-(bis(2-(tetradecanoyloxy)ethyl)amino)-N,N,N-trimethyl-2-oxoethan-1-aminium

chloride (cat. no. DC-6-14),

N-hexadecyl-N,N-dimethylhexadecan-1-aminium

bromide (cat. no. DC-1-16) and dimethyldioctadecylammonium bromide

(DDAB, cat. no. DC-1-18) were purchased from Sogo Pharmaceutical

Co., Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan). 1,2-Dioleoyl-3-trimethylammonium-propane

methyl sulfate salt (DOTAP) was purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids,

Inc. (Alabaster, AL, USA).

1,2-Dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (DOPE,

COATSOME® ME-8181) and polyethylene glycol-cholesteryl

ether (PEG-Chol, mean MW of PEG: 1600) were purchased from NOF Co.,

Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan).

mRNAs

CleanCap® firefly luciferase mRNA (FLuc

mRNA, 1922 nucleotides, cat. no. L-7602) and CleanCap®

enhanced green fluorescent protein mRNA (EGFP mRNA, 997

nucleotides, cat. no. L-7601) were purchased from TriLink

Biotechnologies (San Diego, CA, USA). EZ Cap™ Cy5 firefly

luciferase mRNA (5-moUTP) (Cy5-mRNA, 1921 nucleotides, cat. no.

R1010) was purchased from APExBIO Technology, LLC (Boston, MA,

USA).

Preparation of cationic liposomes and

mRNA lipoplexes

Liposomes were prepared using a mixture of cationic

lipid (DDAB, DOTAP, DC-1-16, DC-6-14, and TC-1-12), DOPE, and

PEG-Chol at a molar ratio of 49.5:49.5:1 via the thin-film

hydration method. Briefly, the lipids were dissolved in chloroform

and, subsequently, chloroform was removed using a rotary evaporator

set at 60˚C to obtain a thin lipid film. The lipid film was

hydrated with sterile water at 60˚C and sonicated to reduce the

particle size for 10 min at 100 W, 42 kHz, and room temperature in

a bath-type sonicator (Bransonic 2510J-MTH; Branson Ultrasonics

Corporation, Danbury, CT, USA). To prepare mRNA lipoplexes, each

mRNA was mixed with cationic liposomes at a charge ratio (+:-) of

4:1 and incubated at room temperature for 10 min.

Size measurement of liposomes and

lipoplexes

The particle size distribution and polydispersity

index (PDI) were measured using an ELS-Z2 light-scattering

photometer (Otsuka Electronics Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan) at 25˚C

after diluting the particle dispersion to an appropriate

concentration with sterile water. The ζ-potential was measured

using electrophoretic light scattering with the same instrument at

25˚C after diluting the sample in the same manner.

Lyophilization process of mRNA

lipoplexes

The mRNA lipoplexes containing 0.5 µg mRNA were

dissolved in 125 µl of 50, 100 or 150 mM trehalose or sucrose

solution and placed in a 12-well plate for transfection assay. For

cytotoxicity assay, those containing 0.05 µg mRNA were dissolved in

12.5 µl of 150 mM trehalose or sucrose solution and placed in a

96-well plate. The mixture was first frozen at -80˚C and then dried

under high vacuum (10-20 Pa) using a freeze dryer (FDU-540, Tokyo

Rikakikai Co., Ltd. (EYELA), Tokyo, Japan) equipped with a drying

chamber (DRC-2L, EYELA). For characterization after long-term

storage, the freeze-dried mRNA lipoplexes were stored under vacuum

in a desiccator at room temperature before use.

Cell culture and reverse

transfection

HeLa cells (cat. no. 93021013; Cellosaurus;

CVCL_0030) were obtained from the European Collection of

Authenticated Cell Cultures. The cells were cultured under the

standard condition in Eagle's Minimum Essential Medium (EMEM;

FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation, Osaka, Japan) supplemented

with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS, Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) and 100 µg/ml kanamycin in

humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 at 37˚C. For

liquid-phase reverse transfection, mRNA lipoplex solution

containing 0.5 µg mRNA was mixed with 1x105 HeLa cells

seeded in 1 ml medium and transferred into the wells of a 12-well

plate. Then it was incubated at 37˚C with 5% CO2 for 24

h. For solid-phase reverse transfection, HeLa cells were seeded at

a density of 1x105 cells per well in a 12-well plate or

1x104 cells per well in a 96-well plate, both containing

freeze-dried mRNA lipoplexes, and incubated at 37˚C with 5%

CO2 for 24 h.

Luciferase activity

quantification

HeLa cells in 12-well plate were lysed 24 h

post-transfection by adding 125 µl of cell lysis buffer (Pierce™

Luciferase Cell Lysis Buffer, ThermoFisher Scientific Inc.). The

lysate was frozen at -80˚C, followed by thawing at 37˚C, and then

centrifuged at 13,000 x g for 10 sec. A 10 µl aliquot of the

supernatants were mixed with 50 µl of PicaGene MelioraStar-LT

Luminescence Reagent (Toyo Ink Mfg. Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) and the

luminescence was measured as counts per sec (cps) with a

chemoluminometer (ARVO X2, PerkinElmer, inc., Waltham, MA, USA).

The protein concentration in the supernatant was measured using the

BCA reagent (Pierce™ BCA Protein Assay Kit, Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.), with bovine serum albumin (BSA) as the standard

and then luciferase activity was calculated as cps/µg protein.

Cytotoxicity of lyophilized mRNA

lipoplexes on HeLa cells

In a 96-well plate containing freeze-dried mRNA

lipoplexes, HeLa cells were seeded at a density of 1x104

cells per well, and incubated at 37˚C with 5% CO2 for 24

h. After transfection, cell viability was evaluated using the WST-8

assay (Cell Counting Kit-8, Dojindo Laboratories, Tokyo, Japan),

according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Flow cytometry analysis for expression

analysis and cellular uptake evaluation

To evaluate the cellular uptake of mRNA lipoplexes,

HeLa cells were seeded at a density of 1x105 cells per

well in a 12-well plate containing freeze-dried Cy5-mRNA lipoplexes

(Cy5-mRNA: 0.5 µg/well), and incubated at 37˚C with 5%

CO2 for 3 h. On the other hand, for expression analysis,

HeLa cells were seeded at a density of 1x105 cells per

well in a 12-well plate containing freeze-dried EGFP mRNA

lipoplexes (EGFP mRNA: 0.5 µg/well), and incubated at 37˚C with 5%

CO2 for 24 h. After transfection, the cells were

harvested using TrypLE™ Express Enzyme (Gibco; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) and resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline

containing with 0.1% BSA and 1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid.

To evaluate the Cy5 fluorescence intensity or EGFP expression in

the cells, 10,000 events per sample were processed using BD

FACSVerseTM (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA)

and analyzed using BD FACSuite software ver. 1.0.3 (BD

Biosciences).

Intracellular co-localization of the

Cy5-mRNA and lysosome observed by confocal microscopy

HeLa cells were seeded at a density of

1x105 cells per well in a 35 mm dish containing

freeze-dried Cy5-mRNA lipoplexes (Cy5-mRNA: 0.5 µg/dish), and

incubated at 37˚C with 5% CO2 for 3 h. The cells were

stained with 75 nM Lysotracker® Red DND-99 (Life

Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) for 30 min. After washing with

PBS, the cells were fixed with Mildform® 10N (FUJIFILM

Wako Pure Chemical Corporation) and then stained with 5 µg/ml

Hoechst 33342 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) for 10 min.

Fluorescence images were acquired using a FLUOVIEW FV3000 confocal

laser scanning microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

Statistical analysis

Data were collected from at least three independent

experiments. All results are presented as mean + standard deviation

(S.D.). Statistical analyses were performed using unpaired

Student's t-test or one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's Multiple

Comparison Test. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad

Prism software (version 4.0; GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA,

USA). Statistical significance was set at P<0.05.

Results

Characterization of mRNA lipoplexes

after lyophilization

When liposomes or lipoplexes are lyophilized,

cryoprotectants such as disaccharides are commonly used to enhance

their stability. Previously, we reported that freeze-drying siRNA

lipoplexes in trehalose or sucrose solution resulted in long-term

stability (1 month) without a significant loss of gene-silencing

activity, regardless of the type of cationic lipid used in the

cationic liposomes (15). In this

study, we investigated whether trehalose or sucrose solutions could

have similar effect as cryoprotectants for mRNA lipoplexes during

lyophilization and examined the effect of these disaccharides on

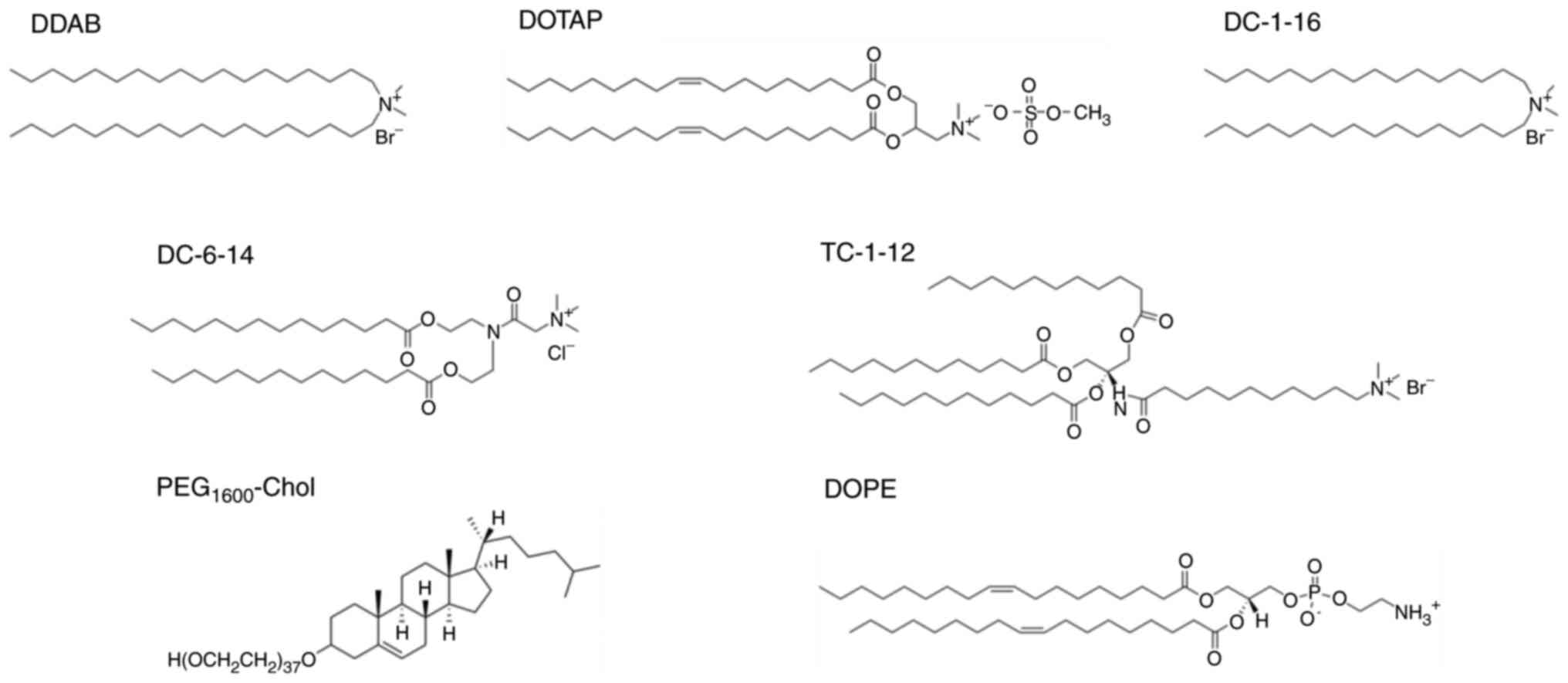

transfection activity after lyophilization. DOTAP, DDAB, DC-6-14,

DC-1-16, and TC-1-12 were used as cationic lipids (Fig. 1). Based on our previous report

(16), liposomes were prepared

with cationic lipids, DOPE, and PEG-Chol at a molar ratio of

49.5:49.5:1, using the thin-film hydration method. The sizes of the

prepared cationic liposomes were approximately 85-106 nm, and the

ζ-potentials were approximately 49-58 mV (Table I).

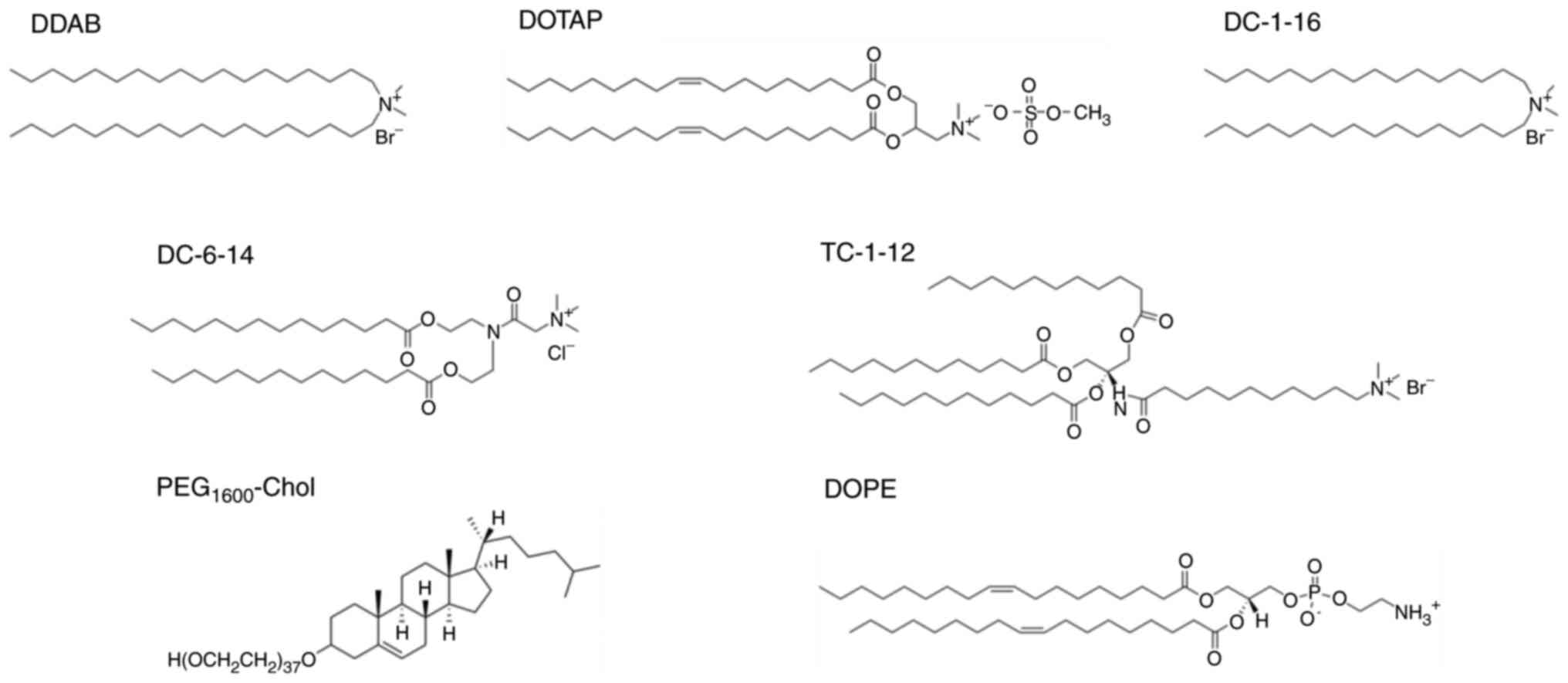

| Figure 1Structures of the lipid components of

liposomes used for mRNA lipoplexes. DDAB,

dimethyldioctadecylammonium bromide; DOTAP,

1,2-dioleoyl-3-trimethylammonium-propane methyl sulfate salt;

DC-1-16,

N-hexadecyl-N,N-dimethylhexadecan-1-aminium

bromide; DC-6-14,

2-(bis(2-(tetradecanoyloxy)ethyl)amino)-N,N,N-trimethyl-2-oxoethan-1-aminium

chloride; TC-1-12,

11-((1,3-bis(dodecanoyloxy)-2-((dodecanoyloxy)methyl) propan-2-yl)

amino)-N,N,N-trimethyl-11-oxoundecan-1-aminium

bromide; DOPE,

1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine;

PEG1600-Chol, polyethylene glycol-cholesteryl ether. |

| Table IParticle size of cationic liposomes

and mRNA lipoplexes. |

Table I

Particle size of cationic liposomes

and mRNA lipoplexes.

| | Liposome | Lipoplex |

|---|

| Cationic lipid | Size, nm | PDI | ζ-potential,

mV | Size, nm | PDI | ζ-potential,

mV |

|---|

| DDAB | 96.0±0.6 | 0.22±0.00 | 50.8±0.9 | 358.8±12.2 | 0.17±0.00 | 34.7±2.1 |

| DOTAP | 85.4±0.5 | 0.22±0.00 | 53.4±1.9 | 367.6±13.4 | 0.17±0.01 | 14.3±0.4 |

| DC-1-16 | 103.5±3.6 | 0.24±0.02 | 58.4±1.4 | 306.6±40.0 | 0.18±0.04 | 20.8±0.4 |

| DC-6-14 | 106.4±0.8 | 0.25±0.01 | 48.9±2.2 | 203.2±14.5 | 0.15±0.07 | 39.9±2.0 |

| TC-1-12 | 85.8±1.5 | 0.22±0.00 | 50.9±1.0 | 278.0±6.4 | 0.14±0.01 | 29.6±0.8 |

Based on our previous report that the optimal charge

ratio (+:-) for mRNA lipoplexes composed of dialkyl or trialkyl

cationic lipids is 4:1(17), we

used the same charge ratio for preparation of mRNA lipoplexes in

subsequent experiments. The mRNA lipoplexes composed of DDAB,

DOTAP, and DC-1-16 formed relatively large particles with diameters

of approximately 310-370 nm. In contrast, the mRNA lipoplexes

containing DC-6-14 were approximately 200 nm in size, whereas those

containing TC-1-12 were approximately 280 nm in size, forming

relatively smaller particles than the aforementioned lipoplexes.

All lipoplexes exhibited a monodisperse distribution (PDI:

0.14-0.18) and the ζ-potentials were approximately 14-40 mV

(Table I).

Effect of lyophilization on the

transfection activity of the mRNA lipoplexes

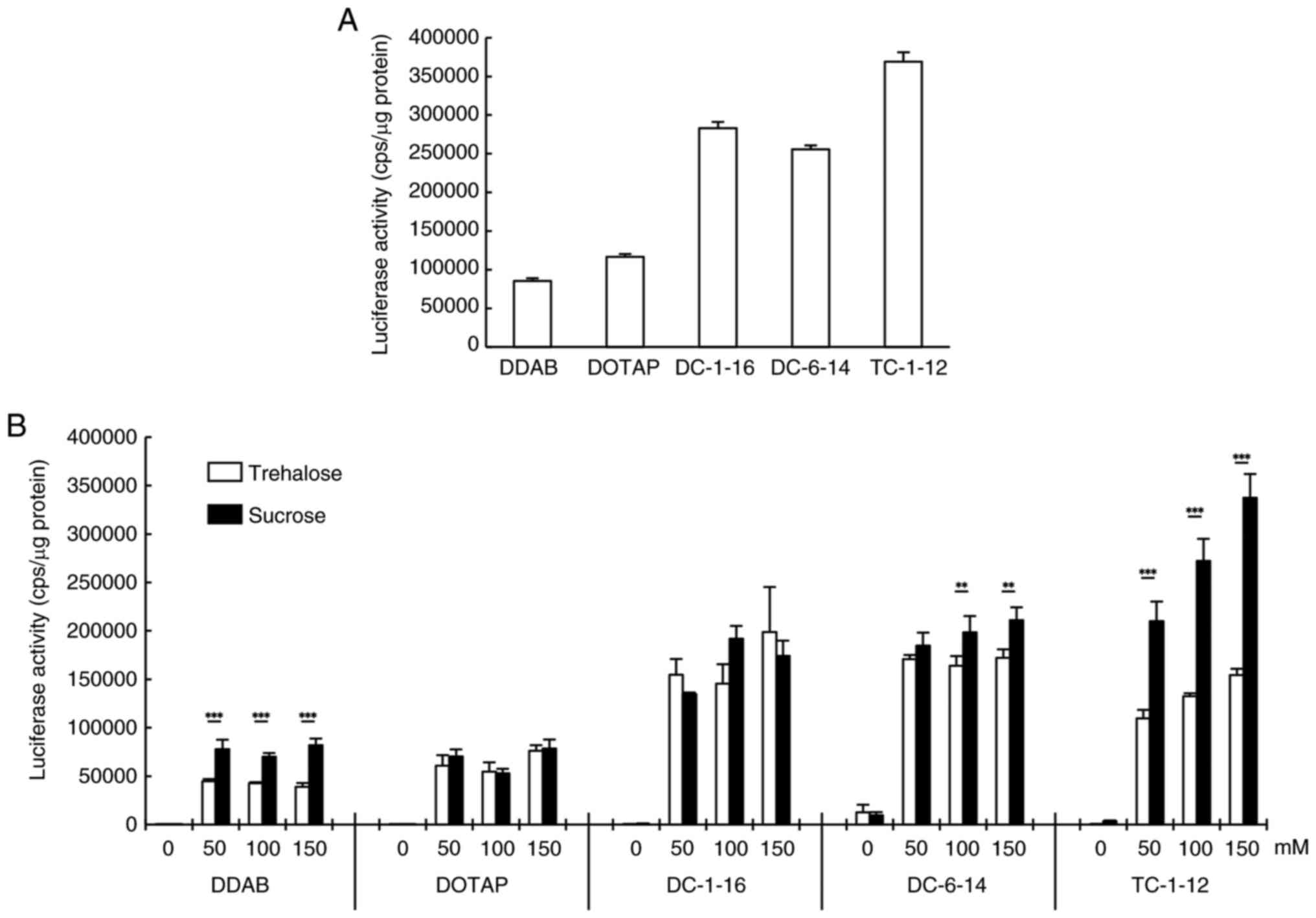

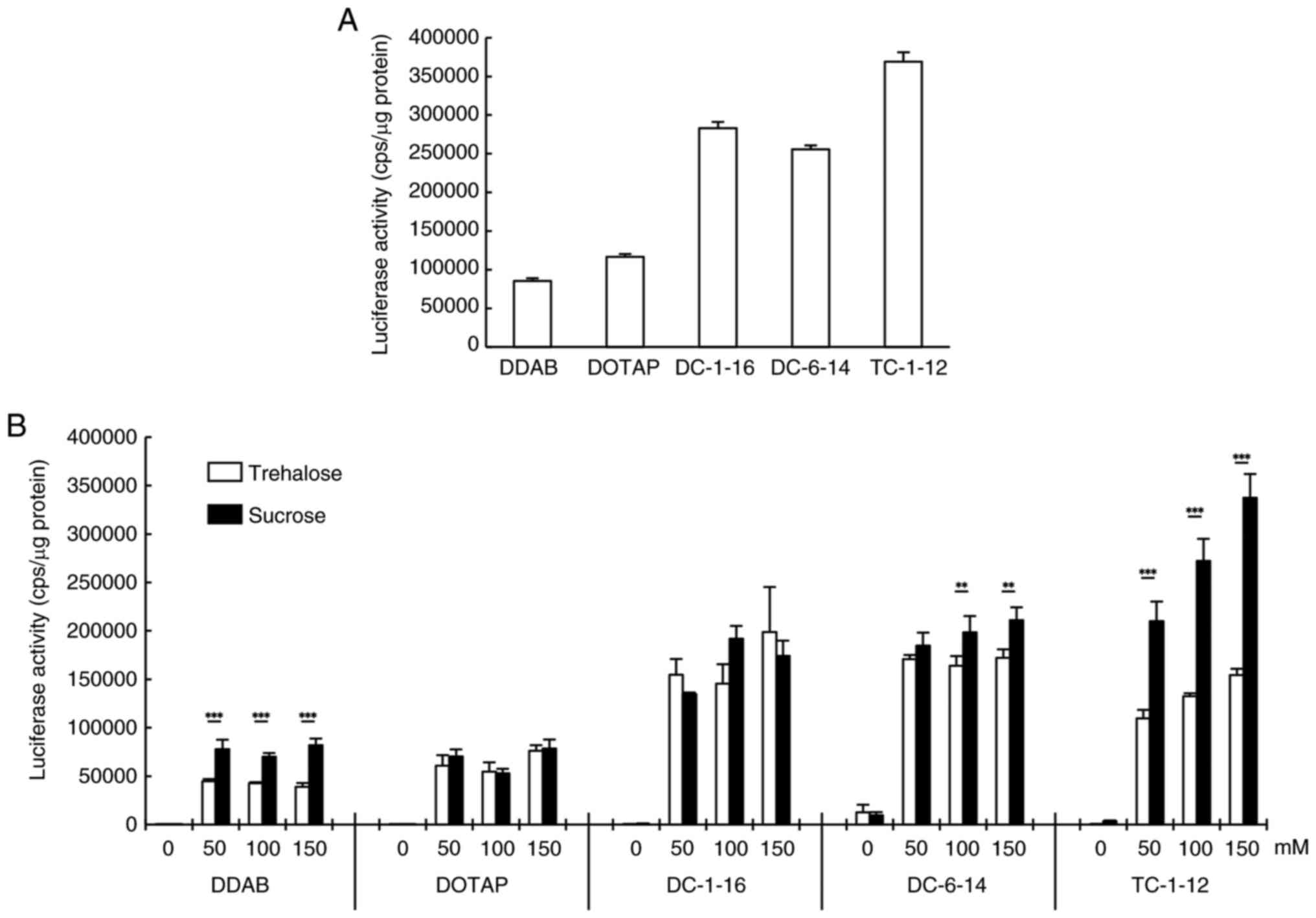

To investigate the effect of lyophilization on the

transfection activity of mRNA lipoplexes, lyophilized FLuc mRNA

lipoplexes containing 0.5 µg of mRNA per well in 12-well plate,

were reverse-transfected into HeLa cells and luciferase activity

was measured 24 h after transfection, because our previous results

showed that a dose of 0.5 µg mRNA with an incubation time of 24 h

resulted in the highest transfection activity in HeLa cells after

forward transfection with mRNA lipoplexes composed of cationic

lipid, neutral lipid and, PEG-Chol at a molar ratio of

49.5:49.5:1(16). Initially,

liquid-phase reverse transfection was performed using mRNA

lipoplexes containing DDAB, DOTAP, DC-1-16, DC-6-14, or TC-1-12

without lyophilization. As previously reported (16), the transfection of mRNA lipoplexes

showed that those containing DC-1-16 or TC-1-12 exhibited high

luciferase activity (Fig. 2A).

FLuc mRNA lipoplexes were lyophilized in 50, 100, or 150 mM

trehalose or sucrose solutions, followed by reverse transfection

into HeLa cells (Fig. 2B).

Regardless of the cationic lipid type used to prepare the

lipoplexes, higher disaccharide concentrations tended to correlate

with increased luciferase activity. Furthermore, in mRNA lipoplexes

containing DDAB, DC-6-14, or TC-1-12, the use of sucrose as a

cryoprotectant resulted in significantly higher activity than

trehalose. Although lyophilization tended to reduce luciferase

activity compared to non-lyophilized conditions, this reduction was

minimized when lipoplexes were lyophilized in 150 mM sucrose

solution. Therefore, in subsequent experiments, a disaccharide

solution with a concentration of 150 mM was used as the

cryoprotectant.

| Figure 2Luciferase activity following reverse

transfection with FLuc mRNA lipoplexes. (A) non-lyophilized FLuc

mRNA lipoplexes containing each cationic lipid were reverse

transfected into HeLa cells and luciferase activity was measured 24

h after the transfection. (B) Lyophilized FLuc mRNA lipoplexes with

0-150 mM trehalose or sucrose were reverse transfected into HeLa

cells. Luciferase activity was measured 24 h after the

transfection. **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001

(trehalose vs. sucrose). Data are presented as mean ± standard

deviation (n=3 in each group). DDAB, dimethyldioctadecylammonium

bromide; DOTAP, 1,2-dioleoyl-3-trimethylammonium-propane methyl

sulfate salt; DC-1-16,

N-hexadecyl-N,N-dimethylhexadecan-1-aminium

bromide; DC-6-14,

2-(bis(2-(tetradecanoyloxy)ethyl)amino)-N,N,N-trimethyl-2-oxoethan-1-aminium

chloride; TC-1-12,

11-((1,3-bis(dodecanoyloxy)-2-((dodecanoyloxy)methyl) propan-2-yl)

amino)-N,N,N-trimethyl-11-oxoundecan-1-aminium

bromide; cps, count per sec. |

Effect of lyophilization on the

particle size and cytotoxicity of the mRNA lipoplexes

To investigate whether lyophilization affects the

physical properties of mRNA lipoplexes, mRNA lipoplexes were

lyophilized on a plate using 150 mM trehalose or sucrose solution

as a cryoprotectant. Particle size measurements after rehydration

of lyophilized mRNA lipoplexes revealed that regardless of the type

of cryoprotectant, mRNA lipoplexes containing DDAB, DOTAP, or

DC-1-16, which exhibited a tendency for larger particle sizes

before lyophilization, showed a reduction in size to approximately

250-280 nm (Table II). In

contrast, the particle size of the mRNA lipoplexes containing

DC-6-14, which were relatively small in diameter before

lyophilization, tended to increase slightly upon lyophilization,

reaching approximately 230 nm. In addition, the particle size of

the mRNA lipoplexes containing TC-1-12 increased upon

lyophilization, reaching approximately 350-380 nm. The ζ-potentials

after lyophilization were approximately 23-40 mV (Table II).

| Table IIParticle size of lyophilized and

rehydrated mRNA lipoplexes. |

Table II

Particle size of lyophilized and

rehydrated mRNA lipoplexes.

| | Trehalose | Sucrose |

|---|

| Cationic lipid | Size, nm | PDI | ζ-potential,

mV | Size, nm | PDI | ζ-potential,

mV |

|---|

| DDAB | 250.6±38.0 | 0.17±0.08 | 28.1±2.5 | 253.1±7.0 | 0.12±0.00 | 26.6±1.6 |

| DOTAP | 251.2±30.1 | 0.18±0.05 | 24.2±2.7 | 282.3±15.5 | 0.13±0.01 | 25.4±0.2 |

| DC-1-16 | 279.1±9.1 | 0.13±0.01 | 30.4±2.1 | 283.0±17.3 | 0.13±0.01 | 29.8±0.6 |

| DC-6-14 | 230.3±16.0 | 0.19±0.07 | 22.8±0.4 | 234.4±7.1 | 0.18±0.05 | 24.7±0.6 |

| TC-1-12 | 350.7±16.3 | 0.16±0.01 | 40.0±0.4 | 379.1±37.1 | 0.17±0.02 | 36.3±1.3 |

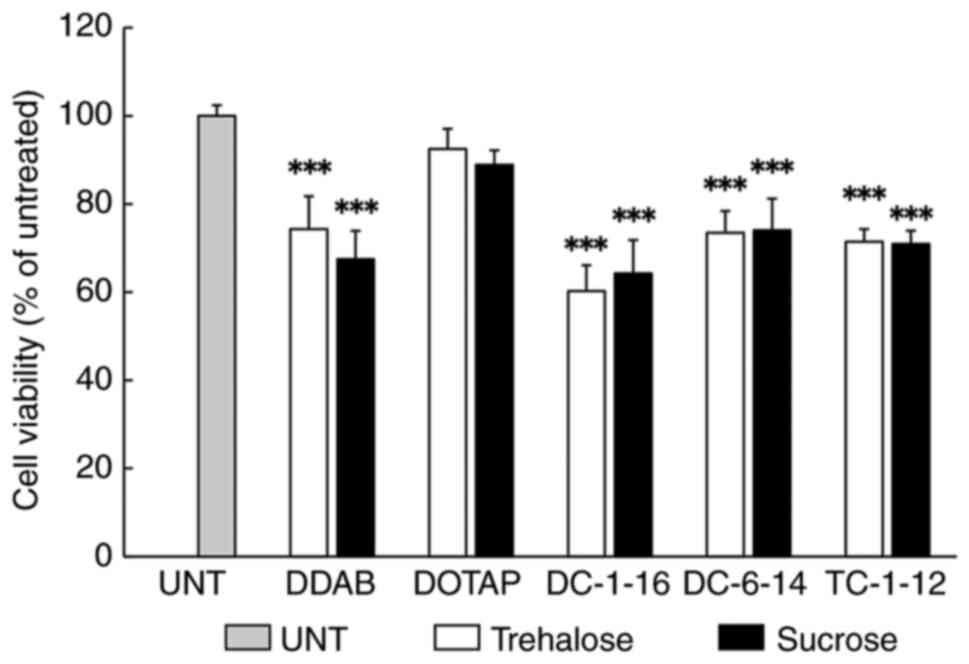

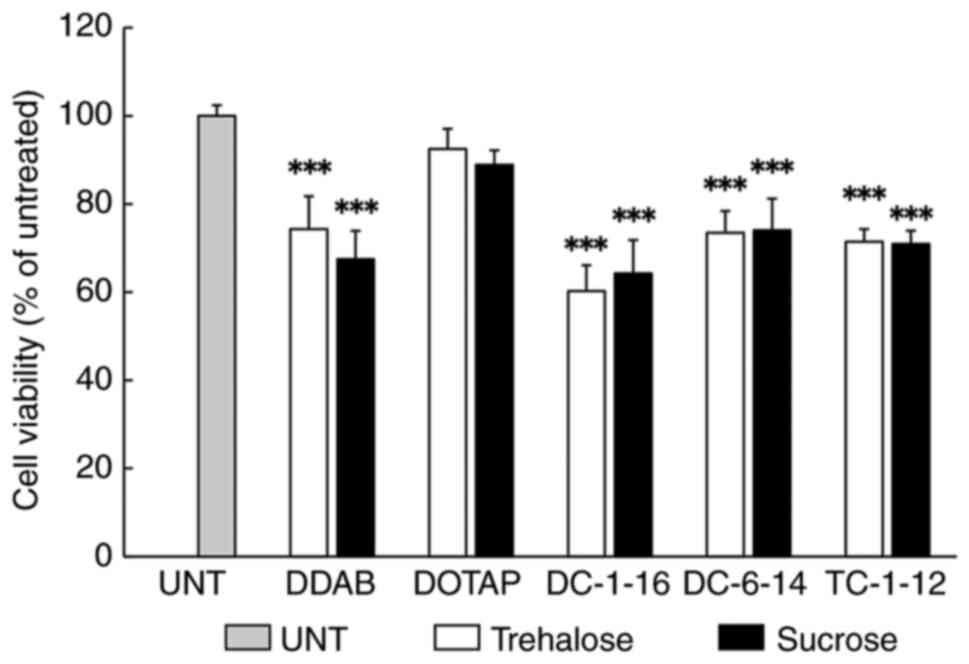

Furthermore, HeLa cell viability was assessed 24 h

after reverse transfection with lyophilized mRNA lipoplexes

(Fig. 3). When lyophilized in the

presence of a 150 mM trehalose or sucrose solution, the mRNA

lipoplexes containing DC-1-16 exhibited a slightly lower cell

viability of approximately 60%. In contrast, the mRNA lipoplexes

containing DOTAP showed cell viability of approximately 90%. For

mRNA lipoplexes containing other cationic lipids, cell viability

was approximately 70%. No significant effect on cell viability was

owing due to the differences in disaccharides.

| Figure 3Toxicity test of lyophilized mRNA

lipoplexes. FLuc mRNA lipoplexes containing each cationic lipid

were lyophilized with 150 mM trehalose or sucrose solution. The

lipoplexes were reverse transfected into HeLa cells and the cell

viability was measured using WST-8 assay 24 h after the

transfection. ***P<0.001 vs. UNT. Data are presented

as mean ± standard deviation (n=5 in each group). UNT, untreated

group; DDAB, dimethyldioctadecylammonium bromide; DOTAP,

1,2-dioleoyl-3-trimethylammonium-propane methyl sulfate salt;

DC-1-16,

N-hexadecyl-N,N-dimethylhexadecan-1-aminium

bromide; DC-6-14,

2-(bis(2-(tetradecanoyloxy)ethyl)amino)-N,N,N-trimethyl-2-oxoethan-1-aminium

chloride; TC-1-12,

11-((1,3-bis(dodecanoyloxy)-2-((dodecanoyloxy)methyl) propan-2-yl)

amino)-N,N,N-trimethyl-11-oxoundecan-1-aminium

bromide. |

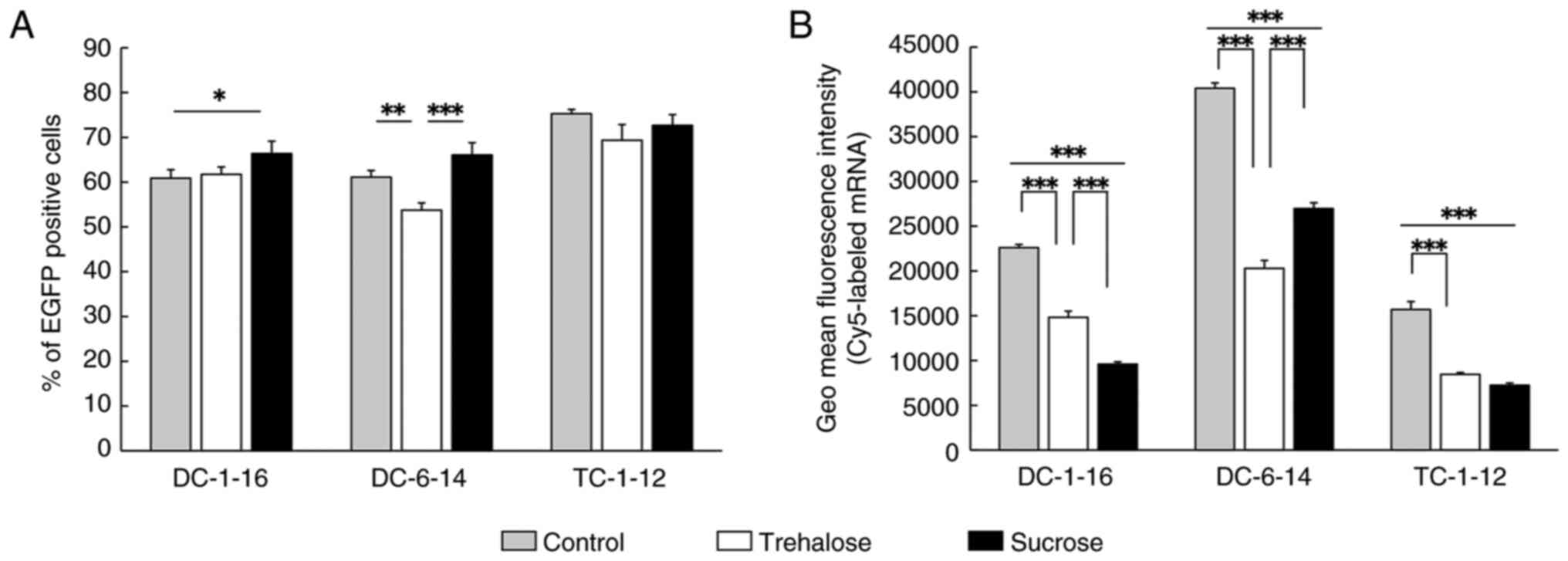

Effect of lyophilization on the

transfection efficiency and cellular uptake

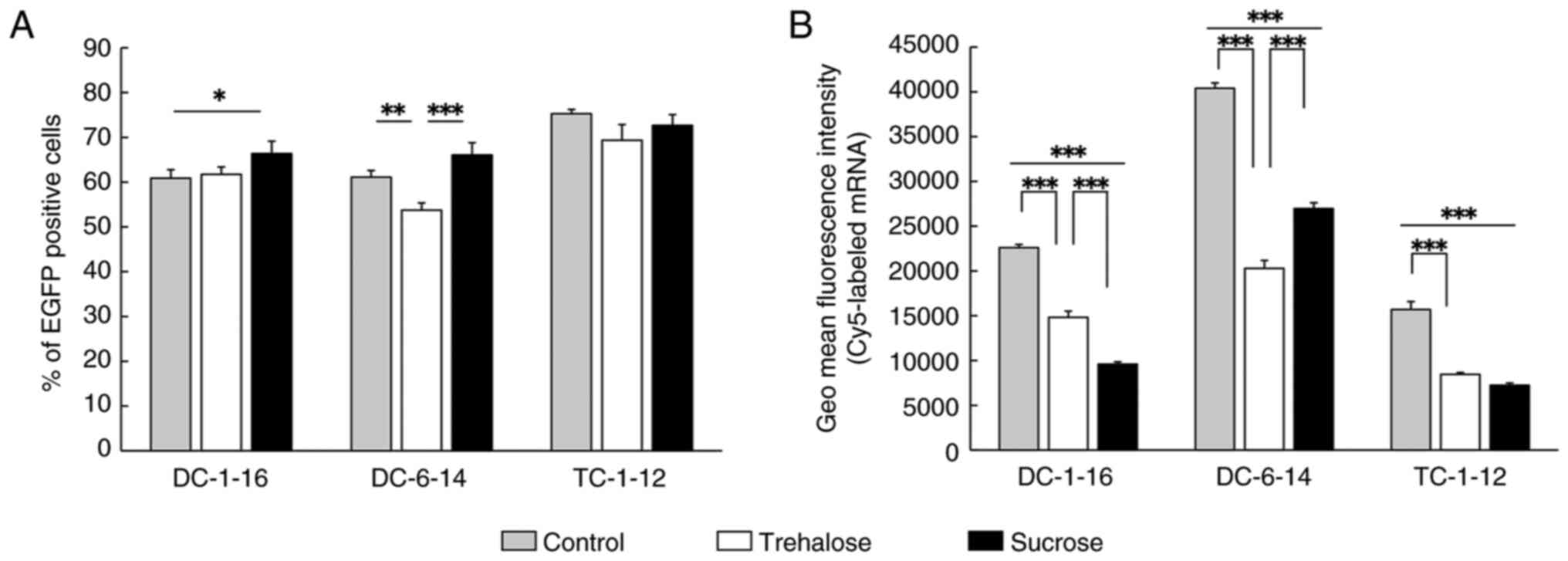

To further investigate the effects of lyophilization

on the transfection activity of mRNA lipoplexes, we examined the

transfection efficiency using mRNA lipoplexes containing DC-1-16,

DC-6-14 or TC-1-12, which exhibited high transfection activity in

the experiments using Luc mRNA. EGFP mRNA lipoplexes were

lyophilized and reverse transfected into HeLa cells, and 24 h after

transfection, flow cytometry showed the appearance of a new peak on

the higher fluorescence intensity side of the histogram compared to

untreated cells, indicating the presence of EGFP-expressing cells

(Fig. S1). Based on these

results, the percentage of EGFP-positive cells was calculated

(Fig. 4A). When mRNA lipoplexes

containing DC-6-14 were lyophilized in a trehalose solution, the

proportion of EGFP-expressed cells decreased compared to that in

the non-lyophilized lipoplexes. However, unexpectedly, when the

mRNA lipoplexes containing DC-1-16 were lyophilized in a sucrose

solution, the proportion of them was increased. In other mRNA

lipoplexes lyophilized in sucrose or trehalose solution, no

significant difference in percentage was observed between

lyophilized and non-lyophilized lipoplexes.

| Figure 4Analysis of transfection efficiency

and cellular uptake of the lyophilized mRNA lipoplexes. (A) EGFP

mRNA lipoplexes containing DC-1-16, DC-6-14 or TC-1-12 were reverse

transfected into HeLa cells. The percentage of EGFP positive cells

was measured 24 h after transfection. (B) Cy5-mRNA lipoplexes

containing DC-1-16, DC-6-14 or TC-1-12 were reverse transfected

into HeLa cells. The fluorescence intensity was measured 3 h after

transfection. Control, Group subjected to reverse transfection with

non-lyophilized mRNA lipoplexes. *P<0.05,

**P<0.01 and ***P<0.001. Data are

presented as mean ± standard deviation (n=3 in each group). EGFP,

enhanced green fluorescent protein; DC-1-16,

N-hexadecyl-N,N-dimethylhexadecan-1-aminium

bromide; DC-6-14,

2-(bis(2-(tetradecanoyloxy)ethyl)amino)-N,N,N-trimethyl-2-oxoethan-1-aminium

chloride; TC-1-12,

11-((1,3-bis(dodecanoyloxy)-2-((dodecanoyloxy)methyl) propan-2-yl)

amino)-N,N,N-trimethyl-11-oxoundecan-1-aminium

bromide. |

These differences in transfection efficiency could

be influenced by the efficiency of the intracellular uptake of mRNA

lipoplexes. Therefore, to investigate this question, we examined

cellular uptake using the same liposome as in the aforementioned

experiment. Lyophilized Cy5-mRNA lipoplexes were reverse

transfected into HeLa cells and the fluorescence intensity of the

internalized Cy5-mRNA was measured using flow cytometry 3 h after

transfection. Compared to untreated cells, the cells transfected

with Cy5-mRNA lipoplexes showed a rightward shift in the histogram

peak, indicating successful uptake of Cy5-mRNA (Fig. S2). The mean fluorescence intensity

of Cy5-mRNA internalized cells was measured, lyophilization led to

a reduction in the Cy5 fluorescence intensity in the cells,

regardless of the type of cationic lipid used (Fig. 4B). Focusing on the differences in

cationic lipids within the lipoplexes, mRNA lipoplexes containing

DC-6-14 exhibited the highest cellular uptake of mRNA regardless of

whether lyophilization was performed with trehalose or sucrose as

the cryoprotectant. Moreover, a similar tendency was observed in

liquid-phase reverse transfection without lyophilization (Fig. 4B). In contrast, focusing on the

differences in the disaccharides used as cryoprotectants, mRNA

lipoplexes containing DC-6-14 lyophilized in sucrose exhibited

higher cellular uptake than those lyophilized in trehalose. In

contrast, those containing DC-1-16 lyophilized in sucrose showed

lower fluorescence intensity than those in trehalose. However, for

those containing TC-1-12, no significant difference in cellular

uptake was observed between lyophilization with sucrose and

trehalose solutions (Fig. 4B).

These results indicate that the cellular uptake of mRNA lipoplexes

may have a limited impact on transfection efficiency.

On the other hand, endosomal escape is also an

important factor for protein expression from transfected mRNA.

Therefore, we additionally examined the intracellular localization

of mRNA and lysosomes. As a result, although partial colocalization

of mRNA with lysosomes was detected regardless of the type of

lipoplex used (Fig. S3), no

noticeable differences in colocalization were observed among the

types of cationic lipid contained or between the disaccharides used

during lyophilization.

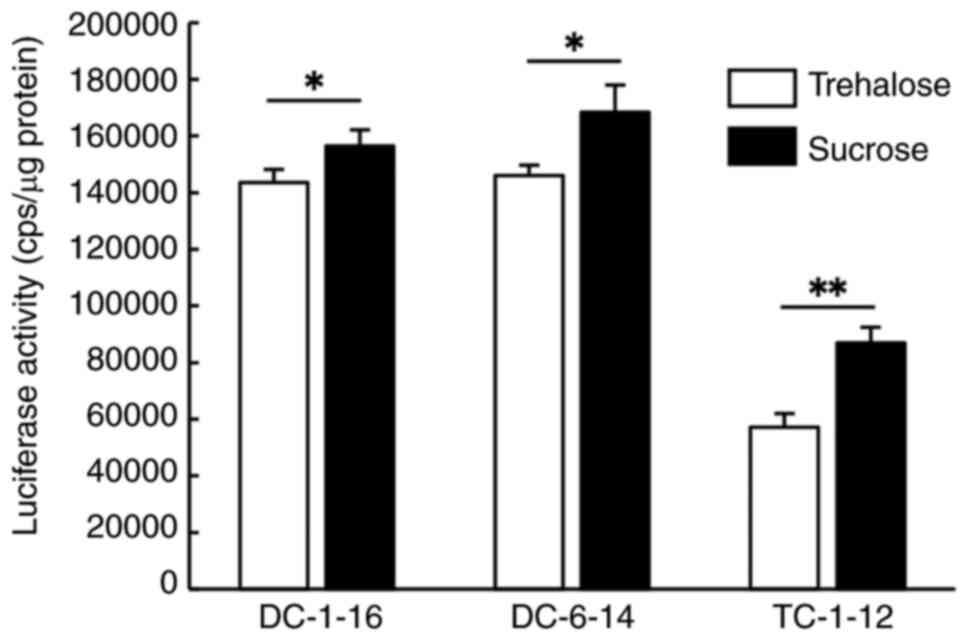

Assessment of long-term stability of

lyophilized mRNA lipoplexes

Since we confirmed that lyophilization does not

necessarily lead to a reduction in the transfection activity of

mRNA lipoplexes, depending on the cationic lipid of the liposome

and the type of cryoprotectant, we evaluated the long-term

stability of mRNA lipoplexes after lyophilization. mRNA lipoplexes

containing DC-1-16, DC-6-14, or TC-1-12 were lyophilized under the

same conditions as in the previous experiments and stored in a

desiccator under vacuum at room temperature for 1 month.

The particle size, PDI, and ζ-potential of mRNA

lipoplexes rehydrated after one month of storage are shown in

Table III. The particle size of

the mRNA lipoplexes containing DC-1-16 or TC-1-12 remained

unchanged. However, those containing DC-6-14 exhibited an increase

in particle size to approximately 300-320 nm after one month of

storage. For the ζ-potential, mRNA lipoplexes containing DC-1-16

exhibited values of approximately 25-26 mV, while those containing

DC-6-14 showed approximately 27-35 mV, and those with TC-1-12 had

approximately 40-44 mV.

| Table IIIParticle size of rehydrated mRNA

lipoplexes after 1 month of storage. |

Table III

Particle size of rehydrated mRNA

lipoplexes after 1 month of storage.

| | Trehalose | Sucrose |

|---|

| Cationic lipid | Size, nm | PDI | ζ-potential,

mV | Size, nm | PDI | ζ-potential,

mV |

|---|

| DC-1-16 | 264.4±14.4 | 0.13±0.01 | 26.0±1.3 | 270.1±4.2 | 0.13±0.00 | 24.6±2.5 |

| DC-6-14 | 321.0± 8.3 | 0.24±0.08 | 35.4±0.3 | 308.0±4.2 | 0.18±0.07 | 27.3±1.4 |

| TC-1-12 | 342.6±18.2 | 0.15±0.01 | 43.5±1.5 | 351.0±13.1 | 0.16±0.01 | 40.2±1.5 |

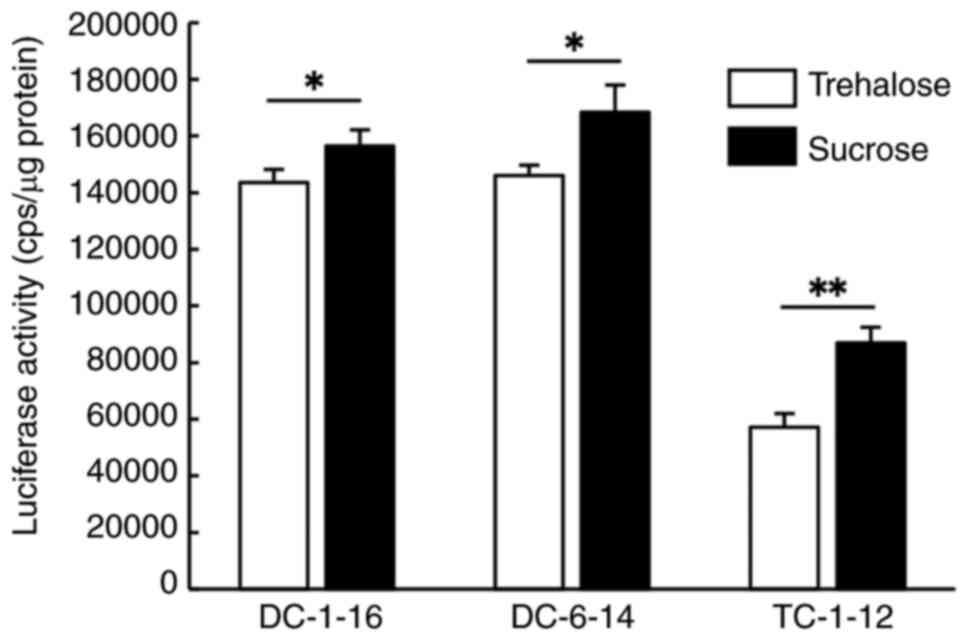

To investigate whether these changes also affected

transfection activity, we performed reverse transfection of HeLa

cells with lyophilized Luc mRNA lipoplexes after one month of

storage. Compared with the results of reverse transfection

performed immediately after lyophilization (Fig. 2B), the luciferase activity of mRNA

lipoplexes containing DC-1-16 or DC-6-14 showed little to no

decrease (Fig. 5). In contrast,

mRNA lipoplexes containing TC-1-12 exhibited a substantial

reduction in luciferase activity after one month of storage

(Fig. 5). Consistent with the

trend observed immediately after lyophilization (Fig. 2B), the use of sucrose solution as a

cryoprotectant resulted in significantly higher luciferase activity

than trehalose solution for all lipoplexes (Fig. 5). From the above results, although

dependent on the type of lipid, it was suggested that the long-term

storage of mRNA lipoplexes is feasible through lyophilization in a

disaccharide solution.

| Figure 5Luciferase activity following reverse

transfection with lyophilized FLuc mRNA lipoplexes after 1 month of

storage. FLuc mRNA lipoplexes containing each cationic lipid were

lyophilized with 150 mM trehalose or sucrose and stored for 1

month. The lipoplexes were reverse transfected into HeLa cells and

luciferase activity was measured 24 h after transfection.

*P<0.05 and **P<0.01. Data are

presented as mean ± standard deviation (n=3 in each group).

DC-1-16,

N-hexadecyl-N,N-dimethylhexadecan-1-aminium

bromide; DC-6-14,

2-(bis(2-(tetradecanoyloxy)ethyl)amino)-N,N,N-trimethyl-2-oxoethan-1-aminium

chloride; TC-1-12,

11-((1,3-bis(dodecanoyloxy)-2-((dodecanoyloxy)methyl) propan-2-yl)

amino)-N,N,N-trimethyl-11-oxoundecan-1-aminium

bromide; cps, count per sec. |

Discussion

Lyophilization removes water via sublimation under

low temperature and vacuum conditions, and is considered an

effective method for maintaining the long-term stability of

lipoplexes (18,19). However, lyophilization imposes

significant stress on the liposomes. Therefore, in the absence of

appropriate cryoprotectants such as sugars, liposomes may be

damaged (13,20). Several studies have reported that,

with certain modifications or optimizations, the lyophilization of

various lipid nanoparticles complexed with nucleic acids, such as

mRNA, can enhance their long-term stability (21,22).

In this study, cationic liposomes were prepared using five types of

cationic lipids in combination with DOPE and PEG-Chol and used as

mRNA carriers for solid-phase reverse transfection. First, we

investigated the effect of lyophilization in the presence of

disaccharide solutions on the particle size of lipoplexes prepared

using these liposomes. The results showed that the mRNA lipoplexes

formulated with cationic lipids with relatively long carbon chains

exhibited a decrease in particle size after lyophilization and

rehydration. In contrast, lipoplexes formulated with cationic

lipids having relatively short carbon chains showed a slight

increase in particle size after lyophilization and rehydration.

Furthermore, the particle size of lyophilized plasmid DNA-based

lipoplexes containing DOTAP decreased after rehydration (23). In contrast, it has also been

reported that the particle size of siRNA lipoplexes containing DDAB

or DOTAP can increase depending on the type of disaccharide

solution used during lyophilization (12). These findings, together with our

results, suggest that both the type of cationic lipid and the

disaccharide solution influence particle size during the

lyophilization process of mRNA lipoplexes.

To evaluate the effect of lyophilization on the

transfection activity, transfection experiments using Luc mRNA were

performed on cultured cells. Initially, we conducted transfection

experiments using the liquid-phase reverse transfection. As

previously reported (16), mRNA

lipoplexes containing cationic lipids with relatively short carbon

chains exhibited higher luciferase activity than those with longer

carbon chains. To examine whether the activity trend due to lipid

differences changes upon lyophilization, solid-phase reverse

transfection was performed, and similar trends were observed. These

results suggest that the lyophilization process does not

significantly affect the variation in luciferase activity owing to

the type of cationic lipid.

Furthermore, the effects of the type and

concentration of disaccharides used during lyophilization were

investigated. When Luc mRNA lipoplexes were lyophilized in

trehalose or sucrose solutions at concentrations ranging from 0 to

150 mM, luciferase activity increased in a concentration-dependent

manner. Additionally, lipoplexes lyophilized in sucrose solution

retained luciferase activity better than those lyophilized in

trehalose solution. These results suggest that, at least for the

liposomes containing cationic lipids used in this study, sucrose is

more suitable for maintaining transfection activity during

lyophilization. In recent years, various saccharides, including

monosaccharides such as glucose and mannitol, and disaccharides

such as sucrose and trehalose, have been used as cryoprotectants

for mRNA lipid nanoparticles (24-26);

however, limited knowledge regarding mRNA lipoplexes exist. Further

research is required to clarify the effects of other saccharide

solutions on mRNA lipoplexes.

To investigate whether the differences in luciferase

activity due to the lipid formulation were attributable to

differences in transfection efficiency, the percentage of

EGFP-expressing cells after reverse transfection with lyophilized

EGFP mRNA lipoplexes was evaluated by flow cytometry. The results

showed that although there were slight increases and decreases

depending on the lipid, similar to the luciferase activity results,

transfection efficiency with EGFP mRNA lipoplexes did not show a

significant difference between liquid- and solid-phase reverse

transfection methods. However, the lipid-dependent differences in

activity observed in the luciferase assay were not observed in the

transfection efficiency of EGFP mRNA lipoplexes. Therefore, to

investigate whether the differences in luciferase activity due to

the lipid formulation resulted from differences in cellular uptake,

the intracellular uptake of Cy5-mRNA was examined. As a result,

unexpectedly, both in the lyophilized and non-lyophilized

conditions, luciferase activity followed the order TC-1-12 >

DC-1-16 ≥ DC-6-14, whereas intracellular uptake followed the

reverse order DC-6-14 > DC-1-16 > TC-1-12, although the

differences were not large. Protein expression following mRNA

transfection may not always correlate with cellular uptake

(27,28). Considering that there were no

remarkable differences observed in endosomal escape, the

differences in transfection activity caused by the lipid

composition may be attributed to changes in mRNA stability or

translation efficiency and so on. While these factors were not

fully explored in this study, identifying the underlying causes is

a key challenge for future studies.

Finally, to evaluate the long-term stability of

these lipoplexes, the lyophilized mRNA lipoplexes were stored under

vacuum at room temperature in a desiccator for one month. No

significant changes in particle size were observed in the mRNA

lipoplexes containing DC-1-16 or TC-1-12. However, those containing

DC-6-14 exhibited an increase in particle size. This suggests that

long-term storage after lyophilization may cause structural changes

in mRNA lipoplexes, depending on the type of cationic lipid used.

However, the changes in luciferase activity after long-term storage

did not necessarily correlate with the changes in particle size.

Although no significant change in particle size was observed in

mRNA lipoplexes containing TC-1-12, luciferase activity was

significantly decreased; the underlying causes remain unclear.

However, we previously reported that siRNA lipoplexes containing

TC-1-12 were unstable following lyophilization (15). Although no clear signs of

aggregation were observed in this study, mRNA lipoplexes containing

TC-1-12 are likely to become unstable over time, which may

ultimately affect the transfection efficiency and luciferase

activity.

In this study, we investigated the effects of

cationic lipids in liposomes and disaccharides used as

cryoprotectants during lyophilization on the transfection

efficiency of lyophilized mRNA lipoplexes. These results suggested

that lyophilization in 150 mM sucrose solution could stabilize

various types of mRNA lipoplexes for at least one month while

minimizing the impact on particle size and transfection activity.

However, certain cationic lipids may not be suitable for long-term

storage, highlighting the need for further investigations into the

relationship between the type of disaccharide cryoprotectant,

selection of cationic lipids, and the long-term stability of

lyophilized mRNA lipoplexes. Furthermore, it remains to be

investigated whether this approach is applicable not only to HeLa

cells but also to other cell types, including primary cultured

cells. This will be an important subject for future studies. Among

the cationic lipids and disaccharide solutions examined, it was

confirmed that lyophilization of mRNA lipoplexes containing DC-6-14

in sucrose solution provided optimal conditions for long-term

storage without significant loss of transfection activity. Based on

the findings of this study, the use of lyophilized mRNA lipoplexes

in reverse transfection strategies suggests their potential for the

development of mRNA-based therapies and gene function screening

methods for various diseases. Specifically, in this platform, by

fixing candidate therapeutic mRNA lipoplexes in multi-well plates,

we can simultaneously test them against multiple types of cancer

cells to identify which types are effective. Additionally, the

preloading of multiple types of therapeutic mRNA as lipoplexes into

multi-well plates enables determination of the most effective

therapeutic mRNA for cancer cells. These approaches enable rapid

identification of therapeutic mRNA for effective cancer therapy,

thereby informing the design of personalized therapies.

In this study, all experiments were conducted in

HeLa cells. Future studies will need to confirm the transfection

efficacy of mRNA lipoplexes across various cancer types. In

particular, to advance toward clinical application, it will be

essential to assess the feasibility of implementing this platform

with patient-derived cancer cells.

Supplementary Material

Representative histograms and gating

areas for the flow cytometry analysis of EGFP positive cells. EGFP

mRNA lipoplexes containing DC-1-16, DC-6-14 or TC-1-12 were reverse

transfected to HeLa cells. The percentage of EGFP positive cells

was measured 24 h after the transfection. Control: Group subjected

to reverse transfection with non-lyophilized mRNA lipoplexes. EGFP,

enhanced green fluorescent protein; DC-1-16,

N-hexadecyl-N,N-dimethylhexadecan-1-aminium

bromide; DC-6-14,

2-(bis(2-(tetradecanoyloxy)ethyl)amino)-N,N,N-trimethyl-2-oxoethan-1-aminium

chloride; TC-1-12, 11-((1,3-bis(dode

canoyloxy)-2-((dodecanoyloxy)methyl) propan-2-yl)

amino)-N,N,N-trimethyl-11-oxoundecan-1-aminium

bromide.

Representative histograms and gating

areas for the flow cytometry analysis of Cy5 positive cells.

Cy5-mRNA lipoplexes containing DC-1-16, DC-6-14 or TC-1-12 were

reverse transfected to HeLa cells. The fluorescence intensity was

measured 3 h after the transfection. Control: Group subjected to

reverse transfection with non-lyophilized mRNA lipoplexes. DC-1-16,

N-hexadecyl-N,N-dimethylhexadecan-1-aminium

bromide; DC-6-14, 2-(bis(2-(tetradecanoyloxy)ethyl)

amino)-N,N,N-trimethyl-2-oxoethan-1-aminium

chloride; TC-1-12,

11-((1,3-bis(dodecanoyloxy)-2-((dodecanoyloxy)methyl) propan-2-yl)

amino)-N,N,N-trimethyl-11-oxoundecan-1-aminium

bromide.

Localization of mRNAs and lysosomes in

HeLa cells after reverse transfection with lyophilized mRNA

lipoplexes. Cy5-mRNA lipoplexes containing DC-1-16, DC-6-14 or

TC-1-12 were reverse transfected to HeLa cells. Lysosomes were

stained by Lysotracker 3 h after the transfection. Blue indicates

cell nuclei stained with Hoechst 33342, green indicates lysosomes

labeled with LysoTracker Red, and red indicates the localization of

Cy5-mRNA. Scale bar, 20 μm. DC-1-16,

N-hexadecyl-N,N-dimethylhexadecan-1-aminium

bromide; DC-6-14, 2-(bis(2-(tetradecanoyloxy)ethyl)

amino)-N,N,N-trimethyl-2-oxoethan-1-aminium

chloride; TC-1-12,

11-((1,3-bis(dodecanoyloxy)-2-((dodecanoyloxy)methyl) propan-2-yl)

amino)-N,N,N-trimethyl-11-oxoundecan-1-aminium

bromide.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Ms. Rio Beppu and Ms. Yuino Mimura

(Department of Molecular Pharmaceutics, Hoshi University, Tokyo,

Japan) for their valuable technical assistance.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

YH conceived the study and designed the project. RS

conducted the experiments. Both YH and RS confirm the authenticity

of the raw data. All authors have read and approved the final

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Sufian MA and Ilies MA: Lipid-based

nucleic acid therapeutics with in vivo efficacy. Wiley Interdiscip

Rev Nanomed Nanobiotechnol. 15(e1856)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Hou X, Zaks T, Langer R and Dong Y: Lipid

nanoparticles for mRNA delivery. Nat Rev Mater. 6:1078–1094.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Zhao W, Hou X, Vick OG and Dong Y: RNA

delivery biomaterials for the treatment of genetic and rare

diseases. Biomaterials. 217(119291)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Inagaki M: Cell reprogramming and

differentiation utilizing messenger RNA for regenerative medicine.

J Dev Biol. 12(1)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Choudry MW, Riaz R, Raza MH, Nawaz P,

Ahmad B, Jahan N, Rafique S, Afzal S, Amin I and Shahid M:

Development of non-viral targeted RNA delivery vehicles-A key

factor in success of therapeutic RNA. J Drug Target. 33:171–184.

2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Wang J, Cai L, Li N, Luo Z, Ren H, Zhang B

and Zhao Y: Developing mRNA nanomedicines with advanced targeting

functions. Nanomicro Lett. 17(155)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Li X, Qi J, Wang J, Hu W, Zhou W, Wang Y

and Li T: Nanoparticle technology for mRNA: Delivery strategy,

clinical application and developmental landscape. Theranostics.

14:738–760. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Audouy S and Hoekstra D: Cationic

lipid-mediated transfection in vitro and in vivo (review). Mol

Membr Biol. 18:129–143. 2001.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Grabbe S, Haas H, Diken M, Kranz LM,

Langguth P and Sahin U: Translating nanoparticulate-personalized

cancer vaccines into clinical applications: Case study with

RNA-lipoplexes for the treatment of melanoma. Nanomedicine (Lond).

11:2723–2734. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Lai E and Van Zanten JH: Evidence of

lipoplex dissociation in liquid formulations. J Pharm Sci.

91:1225–1232. 2002.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Xian H, Zhang Y, Yu C and Wang Y:

Nanobiotechnology-enabled mRNA stabilization. Pharmaceutics.

15(620)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Tang M, Hu S and Hattori Y: Effect of

prefreezing and saccharide types in freeze-drying of siRNA

lipoplexes on genesilencing effects in the cells by reverse

transfection. Mol Med Rep. 22:3233–3244. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Yu J and Anchordoquy TJ: Synergistic

effects of surfactants and sugars on lipoplex stability during

freeze-drying and rehydration. J Pharm Sci. 98:3319–3328.

2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Tang M and Hattori Y: Effect of using

amino acids in the freeze-drying of sirna lipoplexes on gene

knockdown in cells after reverse transfection. Biomed Rep.

15(72)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Hattori Y, Hu S and Onishi H: Effects of

cationic lipids in cationic liposomes and disaccharides in the

freeze-drying of siRNA lipoplexes on gene silencing in cells by

reverse transfection. J Liposome Res. 30:235–245. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Tang M, Sagawa A, Inoue N, Torii S, Tomita

K and Hattori Y: Efficient mRNA delivery with mRNA lipoplexes

prepared using a modified ethanol injection method. Pharmaceutics.

15(1141)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Hattori Y and Shimizu R: Effective mRNA

transfection of tumor cells using cationic triacyl lipid-based mRNA

lipoplexes. Biomed Rep. 22(25)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

del Pozo-Rodríguez A, Solinís MA, Gascón

AR and Pedraz JL: Short- and long-term stability study of

lyophilized solid lipid nanoparticles for gene therapy. Eur J Pharm

Biopharm. 71:181–189. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Mohammed-Saeid W, Michel D, El-Aneed A,

Verrall RE, Low NH and Badea I: Development of lyophilized Gemini

surfactant-based gene delivery systems: Influence of lyophilization

on the structure, activity and stability of the lipoplexes. J Pharm

Pharm Sci. 15:548–567. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Arora S, Dash SK, Dhawan D, Sahoo PK,

Jindal A and Gugulothu D: Freeze-drying revolution: Unleashing the

potential of lyophilization in advancing drug delivery systems.

Drug Deliv Transl Res. 14:1111–1153. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Arte KS, Chen M, Patil CD, Huang Y, Qu L

and Zhou Q: Recent advances in drying and development of solid

formulations for stable mRNA and siRNA lipid nanoparticles. J Pharm

Sci. 114:805–815. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Sun Q, Zhang H, Ding F, Gao X, Zhu Z and

Yang C: Development of ionizable lipid nanoparticles and a

lyophilized formulation for potent CRISPR-Cas9 delivery and genome

editing. Int J Pharm. 652(123845)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Rasoulianboroujeni M, Kupgan G, Moghadam

F, Tahriri M, Boughdachi A, Khoshkenar P, Ambrose JJ, Kiaie N,

Vashaee D, Ramsey JD and Tayebi L: Development of a DNA-liposome

complex for gene delivery applications. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol

Appl. 75:191–197. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Ruppl A, Kiesewetter D, Köll-Weber M,

Lemazurier T, Süss R and Allmendinger A: Formulation screening of

lyophilized mRNA-lipid nanoparticles. Int J Pharm.

671(125272)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Zhao P, Hou X, Yan J, Du S, Xue Y, Li W,

Xiang G and Dong Y: Long-term storage of lipid-like nanoparticles

for mRNA delivery. Bioact Mater. 5:358–363. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Wang T, Sung TC, Yu T, Lin HY, Chen YH,

Zhu ZW, Gong J, Pan J and Higuchi A: Next-generation materials for

RNA-lipid nanoparticles: Lyophilization and targeted transfection.

J Mater Chem B. 11:5083–5093. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Blakney AK, Deletic P, McKay PF, Bouton

CR, Ashford M, Shattock RJ and Sabirsh A: Effect of complexing

lipids on cellular uptake and expression of messenger RNA in human

skin explants. J Control Release. 330:1250–1261. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Sayers EJ, Peel SE, Schantz A, England RM,

Beano M, Bates SM, Desai AS, Puri S, Ashford MB and Jones AT:

Endocytic profiling of cancer cell models reveals critical factors

influencing LNP-mediated mRNA delivery and protein expression. Mol

Ther. 27:1950–1962. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|