Introduction

Dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) is a primary myocardial

disorder characterized by dilation and impaired systolic function

of the left or both ventricles. In children, DCM is the most common

type of cardiomyopathy and a leading indication for heart

transplantation (1,2). Despite advances in diagnostic and

therapeutic strategies, DCM is associated with considerable

morbidity and mortality in the pediatric population (1).

The incidence of pediatric DCM is relatively low but

clinically significant, with reported annual rates ranging from

0.34 to 1.13 cases per 100,000 children, depending on geographic

region and study methodology (1,2).

Etiological factors are heterogeneous and include post-infectious

myocarditis, genetic mutations affecting cytoskeletal or sarcomeric

proteins, metabolic disorders, neuromuscular diseases,

chemotherapy-related cardiotoxicity and idiopathic forms. Several

studies have shown that more than one-third of pediatric cases

remain idiopathic, highlighting the diagnostic challenges

associated with this condition (2).

Clinical presentation is equally diverse. The

majority of children present with signs of congestive heart

failure, such as tachypnea, feeding difficulties or reduced

exercise tolerance, whereas others may present with arrhythmias,

syncope or even sudden cardiac death. The clinical course is highly

variable, with certain patients demonstrating partial recovery,

while others progress to end-stage heart failure, requiring

mechanical support or transplantation. Despite optimal management,

transplant-free survival remains limited, with 5-year survival

rates reported to be only 50-70% (2). Determining prognosis in pediatric DCM

remains a clinical challenge. Although echocardiographic parameters

such as left ventricular ejection fraction, fractional shortening

and left-ventricular end-diastolic diameter (LVEDD), and clinical

parameters such as New York Heart Association or Ross functional

class and heart failure-related hospitalization, are commonly used

to estimate outcomes, they may not fully reflect the complex

pathophysiology of disease progression (1,2).

These conventional measures are load-dependent and provide only a

snapshot of systolic performance and clinical status at a single

time-point, whereas pediatric DCM is influenced by heterogeneous

mechanisms, including genetic predisposition, myocardial

inflammation, remodeling and arrhythmic risk, which are not

adequately captured by baseline echocardiography or bedside

clinical scores (2). Previously

published evidence has suggested that inflammation may serve a role

in the pathogenesis and progression of DCM, raising interest in the

potential prognostic value of inflammatory markers (3-5).

Amongst the inflammatory markers, the

neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) and the the systemic

inflammatory index (SII), calculated as platelet count x neutrophil

count/lymphocyte count, have been garnering attention as accessible

indicators of systemic inflammation. Previous studies in pediatric

DCM have demonstrated the prognostic utility of elevated NLR,

showing its association with poor clinical outcomes (4,5).

However, to the best of our knowledge, no study has evaluated the

prognostic significance of SII in children with DCM, and the

present study is the first to assess both NLR and SII

simultaneously in this patient population.

The present study aims to evaluate the prognostic

significance of clinical, echocardiographic and laboratory

parameters, particularly NLR and SII, in pediatric patients

diagnosed with DCM. By analyzing a long-term, single-center cohort,

the present study aims to contribute to the current understanding

of the prognostic value of systemic inflammatory markers in

pediatric DCM.

Patients and methods

Patient cohort

The present study included 52 pediatric patients

(age, 0-18 years) diagnosed with DCM who were followed at the

Department of Pediatric Cardiology of Marmara University Faculty of

Medicine (Istanbul, Turkey) between January 2000 and June 2021.

Inclusion criteria were a DCM phenotype defined by LV dilatation

with impaired systolic function on echocardiography, including

cases with various underlying causes, such as idiopathic,

post-myocarditis, anthracycline-related or genetic/metabolic.

Exclusion criteria were structural heart disease causing

ventricular dilatation/dysfunction (e.g., critical aortic stenosis,

aortic coarctation with LV dysfunction, coronary anomalies/ischemic

heart disease), and other primary cardiomyopathy phenotypes not

consistent with DCM (e.g., hypertrophic, LV noncompaction,

restrictive or arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy).

Relevant clinical, diagnostic and outcome data were

retrospectively reviewed using patient charts and electronic

medical records. Data collected included age at diagnosis, sex,

presenting symptoms, etiological classification, echocardiographic

and rhythm monitoring findings (including Holter rhythm monitoring

and ECG), treatment modalities, duration of follow-up and survival

status. The NLR was calculated by dividing the absolute neutrophil

count by the absolute lymphocyte count. The SII was calculated

using the following formula: Platelet count x neutrophil

count/lymphocyte count. These values were obtained retrospectively

from complete blood count results derived from peripheral venous

blood samples collected at the time of diagnosis. All analyses were

performed using standardized automated hematology analyzers in the

Central Laboratory of Marmara University Hospital (Istanbul,

Turkey). Echocardiographic measurements were extracted from

standardized reports prepared by experienced pediatric

cardiologists at the time of diagnosis. Although formal

inter-observer variability testing was not performed due to the

retrospective nature of the study, all evaluations were conducted

using consistent institutional protocols.

The aim of the present study was to evaluate the

prognostic impact of various clinical and laboratory parameters,

particularly the NLR and the SII, on mortality.

Ethical approval for the present study was obtained

from the Marmara University Faculty of Medicine Clinical Research

Ethics Committee (approval no. 09.2022.463). The requirement for

informed consent was waived due to the retrospective design of the

study, in accordance with the approval granted by the ethics

committee.

Statistical analysis

Overall survival (OS) was defined as the time from

the diagnosis of DCM to either mortality or the last follow-up.

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 15.0 (SPSS, Inc.)

for Windows. Descriptive statistics are presented as numbers and

percentages for categorical variables, and as mean ± standard

deviation for numerical variables with normal distribution. Group

comparisons for categorical variables were made using the

χ2 test, with Fisher's exact test applied when expected

cell counts were <5. For continuous variables, the

independent-samples t-test was used when the assumption of

normality, as assessed by the Shapiro-Wilk test, was met;

otherwise, the Mann-Whitney U test was applied. Within-patient

comparisons (namely FS and EF from baseline to final follow-up)

were analyzed using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Survival rates

were analyzed using Kaplan-Meier analysis, whereas risk factors

were evaluated using Cox regression analysis. Cut-off values were

determined using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve

analysis. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically

significant difference.

Results

Demographic characteristics

A total of 52 pediatric patients diagnosed with DCM

were included in the present study. The mean age at diagnosis was

58.8±69.8 months (range, 1-216 months). Within the cohort, 48.1%

were female (n=25), and no statistically significant difference was

observed in the sex distribution between deceased (n=16) and

surviving patients. Although the mean age at diagnosis tended to be

higher among patients who succumbed (73.2±67.6 months) compared

with that in survivors (52.4±70.7 months), this difference did not

reach statistical significance (Table

I).

| Table IDemographic and clinical

characteristics of patients with DCM according to survival

status. |

Table I

Demographic and clinical

characteristics of patients with DCM according to survival

status.

| Patient demographic

and clinical characteristics | Total (n=52) | Deceased (n=16) | Survived (n=36) | P-value |

|---|

| Sex, n (%) | | | | 0.677a |

|

Female | 25 (48.1) | 7 (43.8) | 18 (50.0) | |

|

Male | 27 (51.9) | 9 (56.3) | 18 (50.0) | |

| Age at diagnosis,

months (mean ± SD) | 58.8±69.8 | 73.2±67.6 | 52.4±70.7 | 0.051b |

| Weight, kg (mean ±

SD) | 19.5±16.9 | 23.3±17,1 | 17.8±16.8 | 0.111b |

| Height, cm (mean ±

SD) | 116.1±34.1 | 97.3±28.9 | 121.7±34.8 | 0.271b |

| Weight percentile

range, n (%) | | | | 0.831a |

|

<P3 | 19 (37.3) | 4(25) | 15 (42.9) | |

|

P3-P10 | 5 (9.8) | 2 (12.5) | 3 (8.6) | |

|

P10-P25 | 11 (21.6) | 4 (25.0) | 7 (20.0) | |

|

P25-P50 | 9 (17.6) | 4 (25.0) | 5 (14.3) | |

|

P50-P75 | 4 (7.8) | 1 (6.3) | 3 (8.6) | |

|

>P75 | 3 (5.9) | 1 (6.3) | 2 (5.7) | |

| Height percentile

range, n (%) | | | | 0.770a |

|

<P3 | 6 (46.2) | 1 (33.3) | 5 (50.0) | |

|

P3-P10 | 1 (7.7) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (10.0) | |

|

P10-P25 | 1 (7.7) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (10.0) | |

|

P25-P50 | 3 (23.1) | 1 (33.3) | 2 (20.0) | |

|

P50-P75 | 1 (7.7) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (10.0) | |

|

>P75 | 1 (7.7) | 1 (33.3) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Admission symptoms, n

(%) | | | | 0.773a |

|

Heart

failure symptoms | 31 (59.6) | 10 (62.5) | 21 (58.3) | |

|

Heart

failure symptoms + GI symptoms | 6 (11.5) | 3 (18.8) | 3 (8.3) | |

|

GI symptoms

(isolated) | 5 (9.6) | 1 (6.3) | 4 (11.1) | |

|

Isolated

murmur | 2 (3.8) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (5.6) | |

|

Incidentally

detected | 8 (15.4) | 2 (12.5) | 6 (16.7) | |

| Family history of

DCM, n (%) | | | | 0.116a |

|

Negative | 42 (80.8) | 10 (62.5) | 32 (88.9) | |

|

Positive | 5 (9.6) | 3 (18.8) | 2 (5.6) | |

|

Consanguinity,

n (%) | 21 (41.2) | 9 (60.0) | 12 (33.3) | 0.078a |

| Etiology, n

(%)c | | | | 0.469a |

|

Idiopathic | 36 (69.2) | 11 (30.6) | 25 (69.4) | |

|

Post-myocarditis | 15 (28.8) | 4 (26.7) | 11 (73.3) | |

|

Anthracycline-associated | 1 (1.9) | 1 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Hospitalization

duration at diagnosis, days (mean ± SD) | 8.29±10.5 | 10.06±13.94 | 7.50±8.71 | 0.212b |

| Follow-up duration,

months (mean ± SD) | 25.3±30.2 | 17.6±24.1 | 28.7±32.2 | 0.264b |

Consanguinity was present in 41.2% of +patients

overall and was more frequent in the deceased group (60.0%)

compared with that in the survivor group (33.3%), though this was

not statistically significant. The mean weight and height at

diagnosis were 19.5±16.9 kg (range, 4-70 kg) and 116.1±34.1 cm

(range, 55-185 cm), respectively. However, there was no significant

difference in these anthropometric parameters between the two

groups. A total of 37.3% patients had weight in the <3rd

percentile and 46.2% had height in the <3rd percentile. No

significant difference was observed between the deceased and

surviving patient groups for either of the aforementioned

parameters. All baseline demographic and clinical characteristics

of the patients are summarized in Table I.

Etiological classification and

outcome

Among the 52 patients diagnosed with DCM, 15 (28.8%)

had a history of suspected post-myocarditis and 1 patient (1.9%)

had anthracycline-associated cardiomyopathy, whereas 36 patients

(69.2%) were classified as idiopathic in the absence of a clearly

identifiable secondary cause. Additionally, several patients in the

idiopathic group had identifiable genetic or metabolic syndromes,

including Duchenne muscular dystrophy (n=1), Pompe disease (n=2),

Prader-Willi syndrome (n=1) and propionic acidemia (n=2). However,

these syndromic cases were included into the idiopathic group as

they could not be considered separate categories due to their small

numbers. Etiological subgroup comparisons between deceased and

surviving patients showed no statistically significant differences

(Table I).

Clinical findings

Patients presented with a variety of symptoms at

diagnosis (Table I). The most

frequent presentation was typical signs of heart failure, observed

in 59.6% patients. This group included clinical findings, such as

reduced exercise tolerance, tachypnea and tachycardia.

A total of 21.1% patients reported gastrointestinal

(GI) symptoms, including nausea, vomiting or abdominal pain. Among

them, 6 patients (11.5%) had GI symptoms in combination with heart

failure signs, whereas 5 patients (9.6%) presented with isolated GI

complaints. An isolated murmur was the referral reason in 2

patients (3.8%), whilst 15.4% were referred after incidental

findings during routine pediatric evaluations. No statistically

significant difference was found in the presenting symptoms between

deceased and surviving patients.

Laboratory parameters

All laboratory results were obtained at the time of

diagnosis, prior to the initiation of medical treatment (Table II).

| Table IILaboratory parameters and prognostic

comparison. |

Table II

Laboratory parameters and prognostic

comparison.

| Parameter

(reference range) | Total (n=52) | Deceased

(n=16) | Survived

(n=36) | P-value |

|---|

| White blood cell,

x10³/µl (4.5-13.5) | 10.4±3.6 | 10.6±4.1 | 10.3±3.4 | 0.809a |

| Neutrophil, %

(40.0-75.0) | 59.3±20.8 | 71.7±14.7 | 52.1±20.7 | 0.003a |

| Lymphocyte, %

(20.0-45.0) | 31.6±17.3 | 22.0±13.2 | 37.2±17.1 | 0.005a |

| Hemoglobin, g/dl

(11.0-16.0) | 11.47±2.10 | 10.95±1.45 | 11.74±2.35 | 0.239a |

| Hematocrit, %

(33.0-45.0) | 34.81±6.06 | 33.7±4.12 | 35.38±6.82 | 0.391a |

| Platelet, x10³/µl

(150.0-450.0) | 319.0±137.5 | 310.5±155.1 | 323.6±129.9 | 0.980b |

|

Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio | 2.96±2.49 | 4.53±2.72 | 2.06±1.85 | 0.003b |

| Systemic

inflammatory index |

929,393.6±972,589.4 |

1,532,880.4±1,312,699.9 |

581,228.2±451,576.3 | 0.016b |

| C-reactive protein,

mg/l (<5.0) | 6.24±9.11 | 10.66±16.21 | 4.72±4.39 | 0.176b |

| B-type natriuretic

peptide, pg/ml (<100.0) |

15,317.3±13,311.1 |

11,777.0±12,360.1 |

17,399.9±13,767.8 | 0.290b |

| Na, mmol/l

(135.0-145.0) | 136.7±2.6 | 134.3±2.4 | 137.6±2.1 |

<0.001b |

| Mg, mg/dl

(1.7-2.3) | 2.19±0.42 | 1.98±0.24 | 2.26±0.45 | 0.084a |

| K, mmol/l

(3.5-5.0) | 4.68±0.78 | 4.71±0.77 | 4.67±0.80 | 0.913b |

| Ca, mg/dl

(8.5-10.5) | 9.50±0.89 | 9.42±0.68 | 9.53±0.97 | 0.736a |

| Blood urea

nitrogen, mg/dl (7.0-20.0) | 14.45±8.89 | 16.77±7.22 | 13.46±9.47 | 0.069b |

| Urea, mg/dl

(10.0-50.0) | 30.9±19.9 | 37.7±16.4 | 28.61±20.71 | 0.050b |

| Creatinine, mg/dl

(0.3-1.0) | 0.67±1.50 | 0.39±0.16 | 0.78±1.76 | 0.174b |

| Aspartate

aminotransferase, U/l (5.0-40.0) | 77.3±103.7 | 100.9±163.4 | 67.4±66.8 | 0.842b |

| Alanine

aminotransferase, U/l (7.0-56.0) | 54.8±75.7 | 78.9±111.7 | 44.9±54.9 | 0.430b |

| Albumin,

g/dl(3.5-5.5) | 4.02±0.61 | 3.92±0.60 | 4.05±0.62 | 0.351b |

| CK,

U/l(20.0-200.0) | 599.1±1,390.8 | 249.3±341.8 | 721.6±1,596.6 | 0.472b |

| CK-MB, U/l

(0.0-24.0) | 7.37±6.75 | 10.94±9.80 | 5.81±4.45 | 0.216b |

| Troponin I,

ng/ml(<0.04) | 0.06±0.10 | 0.06±0.04 | 0.06±0.12 | 0.155b |

| Troponin T, ng/l

(<14.0) | 82.3±97.3 | 75.2±65.3 | 85.8±113.1 | 0.391b |

The mean white blood cell count was

10,420.9±3,629.7/mm³ (range, 2,800-19,600/mm³). Neutrophil and

lymphocyte percentages were 59.3±20.8% (range, 14-91%) and

31.6±17.3% (range, 3.5-77%), respectively. Hemoglobin level

averaged 11.47±2.10 g/dl (range, 6.3-16.1 g/dl) and hematocrit was

34.81±6.06% (range, 20.2-47.5%). Platelet count was

319,046.5±137,517.3/mm³ (range, 103,000-742,000/mm³).

The mean C-reactive protein level was 6.24±9.11 mg/l

(range, 0-80 mg/l). Electrolyte analysis revealed a mean sodium

level of 136.7±2.6 mmol/l (range, 129-143 mmol/l) and a mean

magnesium level of 2.19±0.42 mg/dl (range, 1.2-2.9 mg/dl). Serum

sodium levels were significantly lower in the deceased group

compared with the survivors (134.3±2.4 vs. 137.6±2.1 mmol/l;

P<0.001). Serum magnesium levels were also lower in the deceased

group (1.98±0.24 vs. 2.26±0.45 mg/dl), although this difference did

not reach statistical significance (P=0.084). Serum potassium and

calcium levels showed no significant differences between groups

(P=0.913 and P=0.736) and remained within normal limits, with mean

values of 4.68±0.78 mmol/l and 9.50±0.89 mg/dl, respectively

(Table II).

Cardiac biomarkers included B-type natriuretic

peptide (BNP), creatine kinase (CK), CK-MB and troponin I. They

were all markedly elevated compared with the reference range. BNP

levels were also markedly elevated, with a mean of

15,317.3±13,311.1 pg/ml (range, 100-57,000 pg/ml). The mean CK

level was 599.1±1,390.8 U/l (range, 70-5,000 U/l), the CK-MB mean

level was 7.37±6.75 U/l (range, 1.2-28 U/l) and the mean troponin I

level was 0.06±0.10 ng/ml (range, 0-0.50 ng/ml). No significant

differences were observed in cardiac biomarkers between the two

groups (Table II).

Renal function markers measured included blood urea

nitrogen, urea and creatinine, with mean values of 14.45±8.89 mg/dl

(range, 3.0-45.0 mg/dl), 30.9±19.9 mg/dl (range, 10-80 mg/dl) and

0.67±1.50 mg/dl (range, 0.2-6.0 mg/dl), respectively. Liver

function tests showed mean aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and

alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels of 77.3±103.7 and 54.8±75.7

U/l, respectively. Although these means were above the reference

ranges, the elevation was driven by a few patients with markedly

high transaminase levels, while the majority of the cohort had

values within normal limits. These findings are summarized in

Table II.

Echocardiographic findings

Echocardiographic evaluation at the time of

diagnosis demonstrated varying degrees of left ventricular

dilatation and systolic dysfunction, consistent with the clinical

profile of DCM. The mean LVEDD was 4.38±1.10 cm. Although LVEDD

values were higher in the deceased group of patients compared with

those in the survivors, the difference did not reach statistical

significance (Table III).

| Table IIIEchocardiographic findings at

diagnosis, Holter rhythm monitoring and electrocardiographic

abnormalities according to survival status. |

Table III

Echocardiographic findings at

diagnosis, Holter rhythm monitoring and electrocardiographic

abnormalities according to survival status.

| Parameter | Total (n=52) | Deceased

(n=16) | Survived

(n=36) | P-value |

|---|

| Interventricular

septal thickness in diastole, cm | 0.63±0.17 | 0.69±0.19 | 0.60±0.15 | 0.076a |

| Left ventricular

end-diastolic diameter, cm | 4.38±1.10 | 4.74±1.01 | 4.23±1.11 | 0.121a |

| Left ventricular

end-systolic diameter, cm | 3.37±1.30 | 3.64±1.33 | 3.26±1.29 | 0.393a |

| Left ventricular

posterior wall thickness in diastole, cm | 0.68±0.48 | 0.69±0.18 | 0.68±0.56 | 0.054b |

| Fractional

shortening, % | 19.1±7.97 | 16.6±5.6 | 20.3±8.7 | 0.132a |

| Ejection fraction,

% | 39.3±13.8 | 34.8±10.1 | 41.3±14.9 | 0.187b |

| Left atrial

diameter, cm | 2.44±0.87 | 2.63±0.91 | 2.37±0.85 | 0.362a |

| Aortic root

diameter, cm | 1.63±0.60 | 1.98±0.76 | 1.50±0.49 | 0.017a |

| Mitral E,

m/sec | 0.89±0.22 | 0.78±0.18 | 0.94±0.22 | 0.031a |

| Mitral A,

m/sec | 0.64±0.19 | 0.59±0.18 | 0.66±0.19 | 0.240a |

| Deceleration time,

msec | 96.6±39.9 | 92.9±34.4 | 98.2±42.5 | 0.695a |

| Isovolumic

relaxation time, msec | 64.8±18.5 | 66.9±23.7 | 63.9±16.3 | 0.639b |

| Aortic root

velocity, m/sec | 1.14±0.32 | 1.05±0.22 | 1.17±0.35 | 0.219b |

| Pulmonary artery

velocity, m/sec | 1.09±0.29 | 0.98±0.24 | 1.13±0.30 | 0.105a |

| Descending Aortic

root velocity, m/sec | 1.17±0.33 | 1.08±0.28 | 1.20±0.35 | 0.219b |

| Holter rhythm

monitoring findings, n (%) | | | |

>0.999c |

|

Supraventricular

ectopic activity | 1 (1.9) | 0(0) | 1 (2.8) | |

|

Ventricular

ectopic activity | 7 (13.7) | 2 (13.3) | 5 (13.9) | |

|

Supraventricular

tachycardia | 5 (9.8) | 1 (6.7) | 4 (11.1) | |

|

Ventricular

tachycardia | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

|

Electrocardiographic findings, n (%) | | | | |

|

No

additional ECG finding | 16 (31.4) | 6 (40.0) | 10 (27.8) | 0.967c |

|

Left

ventricular hypertrophy | 9 (17.6) | 3 (20.0) | 6 (16.7) | |

|

Left

ventricular hypertrophy + inverted T in V5-V6 | 5 (9.8) | 1 (6.7) | 4 (11.1) | |

|

Left

ventricular hypertrophy + left axis deviation | 5 (9.8) | 1 (6.7) | 4 (11.1) | |

|

Left

ventricular hypertrophy + RBBB | 1(2) | 1 (6.7) | 0 (0) | |

|

Frequent

ventricular ectopic activity | 3 (5.9) | 1 (6.7) | 2 (5.6) | |

|

Left axis

deviation | 1(2) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.8) | |

|

Left axis

deviation + left atrial enlargement | 1(2) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.8) | |

|

Right axis

deviation + ST depression | 2 (3.9) | 0 (0) | 2 (5.6) | |

|

Right axis

deviation + biventricular hypertrophy | 1 (2.0) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.8) | |

|

Low QRS

voltage | 3 (5.9) | 1 (6.7) | 2 (5.6) | |

|

Low QRS

voltage + ST elevation | 1 (2.0) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.8) | |

|

Peaked T

wave | 1 (2.0) | 1 (6.7) | 0 (0) | |

|

Supraventricular

tachycardia episode | 1 (2.0) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.8) | |

Left ventricular systolic function, as measured by

FS and EF, was reduced in both groups compared with the expected

normal pediatric ranges (FS <28% and EF <55% indicating

systolic dysfunction). The mean FS was 19.1±7.97% and the mean EF

was 39.3±13.8%. Although deceased patients had lower values for

both FS and EF compared with those in the survivor group (FS:

16.6±5.6 vs. 20.3±8.7%; EF: 34.8±10.1 vs. 41.3±14.9%), the

differences were not statistically significant. Mitral E wave

velocity was, however, found to be significantly lower in the

deceased group (0.78±0.18 vs. 0.94±0.22 m/sec; P=0.031).

Although the mean aortic root diameter was

statistically larger in deceased patients (1.98±0.76 cm) compared

with that in the survivor group (1.50±0.49 cm; P=0.017), all

measurements fell within the normal Z-score range for age (-2 to

+2). This difference was likely attributable to the older mean age

of patients in the deceased group and was not considered clinically

significant.

Other parameters, including left atrial diameter,

mitral A wave velocity, deceleration time, isovolumic relaxation

time and flow velocities across the aortic valve, pulmonary valve

and descending aorta, showed no statistically significant

differences between groups (Table

III).

Rhythm monitoring findings

Electrocardiograph and Holter rhythm monitoring data

were available for all patients. Ventricular ectopic activity (VEA)

was detected in 7 patients (13.5%) and supraventricular VEA in 1

patient (1.9%). In these cases, the ectopic beat burden was <1%

on 24-h Holter rhythm recordings. Therefore, these arrhythmias were

considered rare and clinically insignificant. Supraventricular

tachycardia was observed in 5 patients (9.6%) and no episodes of

ventricular tachycardia were recorded.

Additional electrocardiographic findings included

left axis deviation, low-voltage QRS complexes, ST-T wave

abnormalities and biventricular or left ventricular hypertrophy. No

statistically significant association was found between any

electrocardiographic or Holter rhythm abnormality and mortality.

All Holter rhythm and electrocardiographic findings are summarized

in Table III.

Heart failure management and follow-up

echocardiography

All patients received standard heart failure

therapy. The most commonly prescribed medications were diuretics

(82.7%), angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (80.8%) and

digoxin (69.2%), followed by beta-blockers (19.2%). In addition,

supportive treatments, such as carnitine (50%) and coenzyme Q10

(48.1%), were frequently utilized. Follow-up echocardiographic

evaluations, performed after a mean follow-up duration of 25.3±30.2

months (range, 1-108 months), demonstrated significant improvements

in both EF and FS (Table IV). The

mean EF increased from 39.3% at diagnosis to 49.8% at the final

follow-up (P<0.001), whilst FS improved from 19.1 to 25.6%

(P<0.001). Final echocardiographic measurements revealed that

deceased patients had significantly lower EF and FS values compared

with the survivors group (both P=0.002). These final post-treatment

follow-up measurements according to survival status are summarized

in Table IV.

| Table IVBaseline and final echocardiographic

measurements according to survival status. |

Table IV

Baseline and final echocardiographic

measurements according to survival status.

| | All patients | Current status |

|---|

| Parameter | Baseline (mean ±

SD) | Final (mean ±

SD) |

P-valuea | Deceased group

(mean ± SD) | Surviving group

(mean ± SD) |

P-valueb |

|---|

| Fractional

shortening, % | 19.1±7.97 | 25.6±8.9 | <0.001 | 19.4±8.1 | 28.4±7.9 | 0.002 |

| Ejection fraction,

% | 39.3±13.8 | 49.8±15.3 | <0.001 | 38.5±14.5 | 54.7±13.1 | 0.002 |

Inflammatory markers and prognostic

indices

At the time of diagnosis, inflammatory indices,

including the NLR and SII, were calculated from complete blood

count parameters (Table II). Both

NLR and SII values were found to be significantly higher in

deceased patients compared with those in the survivors group.

Specifically, the mean NLR value for the entire

cohort was 2.96±2.49. NLR was significantly elevated in the

deceased group (4.53±2.72) compared with that in the survivors

group (2.06±1.85; P=0.003). Similarly, the mean SII was

929,393.6±972,589.4 in the overall cohort, with patients in the

deceased group having a significantly higher SII

(1,532,880.4±1,312,699.9) compared with that in the survivors group

(581,228.2±451,576.3; P=0.016).

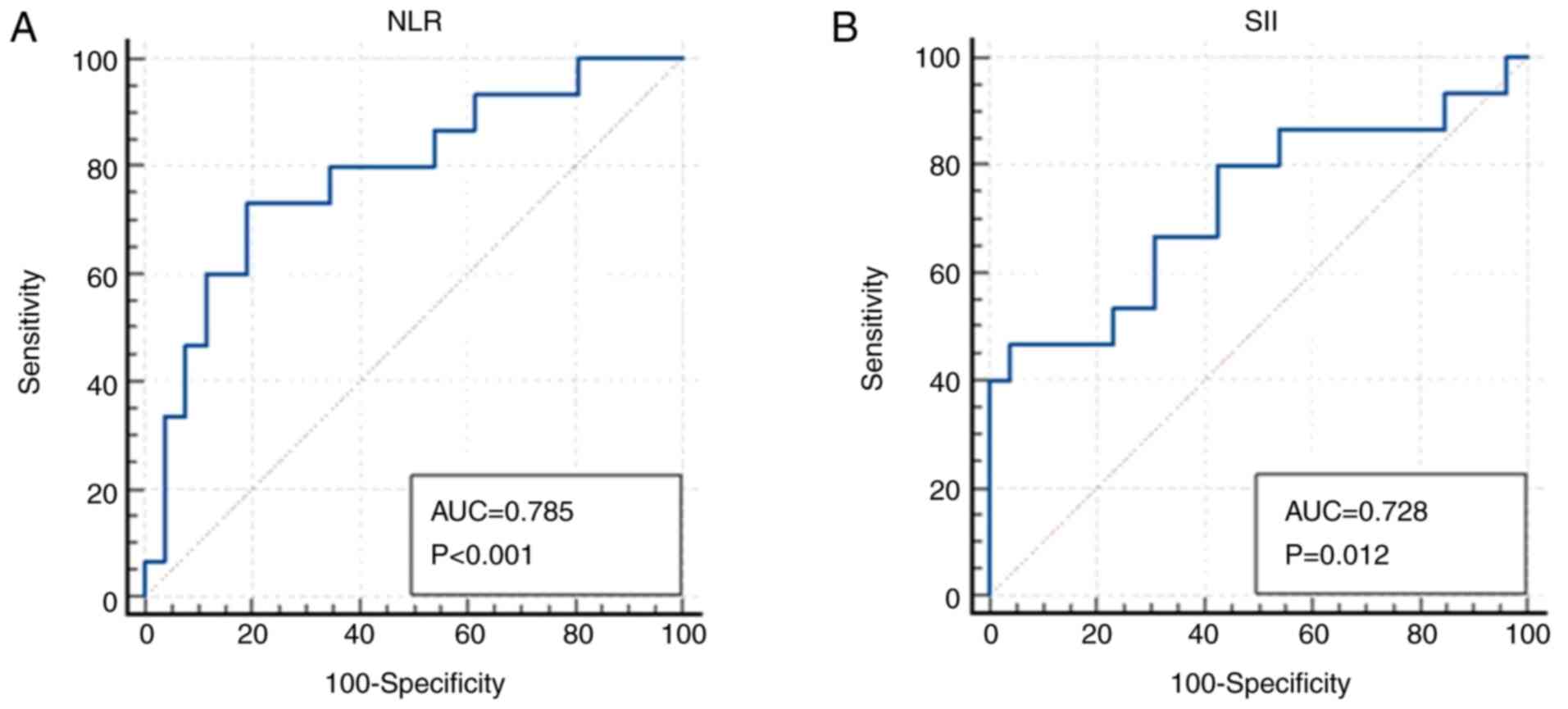

ROC curve analyses were performed separately for NLR

and SII to predict mortality (deceased vs. surviving). The AUC for

NLR was 0.785 (P<0.001) and for SII, it was 0.728 (P=0.012)

(Fig. 1). Based on ROC-derived

thresholds, a cut-off value of >2.75 for NLR and >1,428,898

for SII was associated with increased mortality risk. The AUC

values and corresponding P-values were calculated using the DeLong

test, 95% confidence intervals were computed with the binomial

exact method and optimal cut-off values were determined according

to the Youden index. These findings are summarized in Table V and illustrated in Fig. 1.

| Table VROC curve analysis parameters for NLR

and SII. |

Table V

ROC curve analysis parameters for NLR

and SII.

| Parameter | NLR | SII |

|---|

| Area under the ROC

curve, area under the curve | 0.785 | 0.728 |

| Standard

errora | 0.0777 | 0.0904 |

| 95% Confidence

intervalb | 0.628-0.897 | 0.567-0.855 |

| z statistic | 3.661 | 2.524 |

| Significance level

P-value (area=0.5) | 0.0003 | 0.0116 |

| Youden index J | 0.5410 | 0.4282 |

| Associated

criterion | >2.75 | >1,428,898 |

| Sensitivity | 73.33 | 46.67 |

| Specificity | 80.77 | 96.15 |

Survival and regression analysis

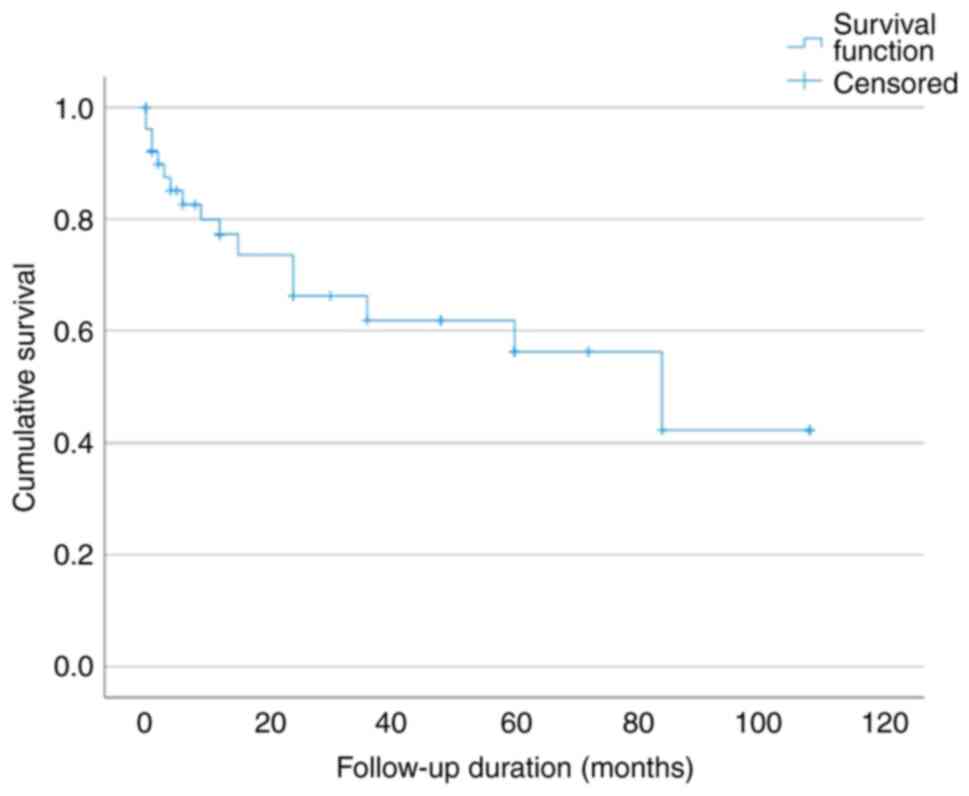

During the follow-up period, 16 of the 52 patients

(30.8%) succumbed. Survival rates were therefore analyzed using

Kaplan-Meier analysis. The OS rates at 1, 2, 3, 5 and 7 years were

77.3, 66.2, 61.8, 56.2 and 42.2%, respectively (Fig. 2). At the end of the follow-up

period, 36 of the 52 patients (69.2%) were alive. This crude

observed survival reflects the survival status at a median

follow-up time of 25 months (mean, 25.3±30.2 months), whereas the

Kaplan-Meier estimate at 7 years (42.2%) was based on a much

smaller number of patients remaining under observation. Although

the median follow-up duration was shorter in deceased patients

(17.6 months) compared with that in the survivors group (28.7

months), this difference was not statistically significant.

Univariate Cox regression analysis (Table VI) identified several variables

that were significantly associated with mortality, including low

serum sodium levels, elevated NLR, higher SII values, increased

aortic root diameter, decreased mitral E wave velocity, low

magnesium levels (within the normal reference range), elevated

neutrophil percentage, decreased lymphocyte percentage and a

positive family history of DCM (the per-unit HR for SII

approximated 1.0 due to its large numeric scale, which limits

interpretability per single-unit increase; however, both group

comparisons and ROC analysis confirmed a significant association

with mortality). Serum sodium levels emerged as one of the most

consistently associated parameters with mortality among all

variables analyzed (P<0.001 for group comparison; HR=0.669, 95%

CI 0.527-0.850; P=0.001 in Cox regression).

| Table VIUnivariate Cox regression analysis of

risk factors for mortality. |

Table VI

Univariate Cox regression analysis of

risk factors for mortality.

| | | 95% CI |

|---|

| Patient

characteristics | P-value | Hazard ratio | Min | Max |

|---|

| Sex (ref:

Female) | 0.953 | 1.031 | 0.380 | 2.793 |

| Age at diagnosis,

months | 0.134 | 1.005 | 0.998 | 1.011 |

| Medical history

present (ref: Absent) | 0.287 | 1.800 | 0.609 | 5.317 |

| Family history

positive (ref: Negative) | 0.049 | 2.808 | 1.006 | 7.838 |

| Consanguinity

present (ref: Absent) | 0.120 | 2.274 | 0.806 | 6.411 |

| Left ventricular

end-diastolic diameter, cm | 0.164 | 1.404 | 0.871 | 2.265 |

| Left ventricular

end-systolic diameter, cm | 0.335 | 1.258 | 0.789 | 2.006 |

| Fractional

shortening, % | 0.618 | 0.980 | 0.905 | 1.061 |

| Ejection fraction,

% | 0.510 | 0.985 | 0.942 | 1.030 |

| Left atrial

diameter, cm | 0.182 | 1.467 | 0.836 | 2.574 |

| Ao diameter,

cm | 0.006 | 2.746 | 1.344 | 5.612 |

| Mitral E,

m/sec | 0.034 | 0.018 | 0.000 | 0.741 |

| Mitral A,

m/sec | 0.210 | 0.126 | 0.005 | 3.221 |

| Ao velocity,

m/sec | 0.511 | 0.471 | 0.050 | 4.441 |

| Pulmonary artery

velocity, m/sec | 0.176 | 0.266 | 0.039 | 1.815 |

| Descending Ao

velocity, m/sec | 0.476 | 0.529 | 0.092 | 3.045 |

| CK, U/l | 0.432 | 0.999 | 0.998 | 1.001 |

| CK-MB, U/l | 0.229 | 1.048 | 0.971 | 1.132 |

| Troponin I,

ng/ml | 0.811 | 0.299 | 0.000 | 5.942 |

| Troponin T,

ng/l | 0.579 | 1.003 | 0.992 | 1.015 |

| B-type natriuretic

peptide, pg/ml | 0.215 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1,000 |

| White blood cells,

x10³/µl | 0.645 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Neutrophil, % | 0.017 | 1.047 | 1.008 | 1.088 |

| Lymphocyte, % | 0.025 | 0.953 | 0.913 | 0.994 |

| Hemoglobin,

g/dl | 0.268 | 0.828 | 0.593 | 1.156 |

| Hematocrit, % | 0.446 | 0.957 | 0.854 | 1.072 |

| Platelet,

x10³/µl | 0.801 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

|

Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio | 0.006 | 1.303 | 1.077 | 1.575 |

| Systemic

inflammation index | 0.001 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| C-reactive protein,

mg/l | 0.905 | 1.003 | 0.959 | 1.048 |

| Blood urea

nitrogen, mg/dl | 0.100 | 1.045 | 0.992 | 1.102 |

| Urea, mg/dl | 0.182 | 1.021 | 0.990 | 1.053 |

| Creatinine,

mg/dl | 0.679 | 0.801 | 0.280 | 2.293 |

| Albumin, g/dl | 0.359 | 0.549 | 0.152 | 1.979 |

| Aspartate

aminotransferase, U/l | 0.199 | 1.003 | 0.999 | 1.007 |

| Alanine

aminotransferase, U/l | 0.285 | 1.003 | 0.997 | 1.010 |

| Na, mmol/l | 0.001 | 0.669 | 0.527 | 0.850 |

| K, mmol/l | 0.631 | 0.773 | 0.270 | 2.211 |

| Ca, mg/dl | 0.463 | 0.768 | 0.381 | 1.552 |

| Mg, mg/dl | 0.019 | 0.026 | 0.001 | 0.547 |

Discussion

DCM in childhood is a rare condition characterized

by impaired ventricular function and progressive heart failure. The

annual incidence of pediatric DCM ranges between 0.57 and 1.13

cases per 100,000 children, with an estimated prevalence of ~1 per

250,000(2). DCM remains one of the

leading indications for cardiac transplantation in the pediatric

population. Despite advances in medical therapy and heart failure

management, predicting outcomes in pediatric DCM continues to be a

major clinical challenge (6). This

is largely due to the disease's heterogeneous etiology, variable

clinical course and the limited data regarding prognostic

indicators in children (2,6).

In previous years, systemic inflammation has been

increasingly recognized to be a contributing factor in various

cardiovascular conditions (7).

Inflammatory responses may influence myocardial function through

cytokine-mediated pathways, microvascular dysfunction and

myocardial remodeling (7,8). Among the accessible inflammatory

markers, NLR and SII have gained attention as simple cost-effective

indicators reflecting the balance between proinflammatory and

regulatory immune responses (9,10).

In pediatric DCM, data on the prognostic role of

inflammatory markers remain limited. The majority of studies to

date have focused solely on the NLR. Ahmed et al (5) demonstrated that elevated NLR levels

were significantly associated with disease severity and adverse

outcomes in children with DCM-related acute heart failure.

Similarly, da Rocha Araújo et al (4) reported that elevated NLR was

associated with poor clinical progression, increased mortality and

the necessity for cardiac transplantation. To the best of our

knowledge, no study to date has evaluated the prognostic role of

the SII or investigated both NLR and SII in the same pediatric DCM

population. By introducing SII into the pediatric cardiology

literature, the present study provides a contribution to the

understanding of inflammation-based risk assessment in this

population.

NLR and SII have both been studied as prognostic

markers in adult patients with heart failure and cardiomyopathies,

where it has been determined that these markers are associated with

poor outcomes and increased mortality (11-14).

By evaluating the prognostic value of NLR and SII simultaneously in

a pediatric DCM cohort, the present study offers data and

contributes to addressing the current knowledge gap in this

field.

In present study, both the NLR and the SII were

significantly higher in patients who succumbed compared with those

in the survivors group. ROC curve analysis confirmed that both

markers had prognostic value for mortality, with NLR showing an AUC

of 0.785 and SII exhibiting an AUC of 0.728. The identified cut-off

values (>2.75 for NLR and >1,428,898 for SII), as determined

by ROC analysis, were statistically significant predictors of

mortality. Specifically, the NLR cut-off demonstrated a sensitivity

of 73.3% and a specificity of 80.8%, indicating balanced diagnostic

accuracy. By contrast, the SII cut-off yielded a lower sensitivity

(46.7%) but a notably high specificity (96.2%), suggesting that

patients exceeding this threshold could be identified as truly

high-risk with greater confidence. These findings were further

supported by univariate Cox regression analysis, in which both

markers showed significant associations with mortality. Notably,

low serum sodium levels also demonstrated the strongest statistical

association with mortality among all variables included in the

analysis. This observation aligns with previous reports from both

adult and pediatric populations, where hyponatremia has been

independently associated with adverse outcomes in heart failure

(15,16).

In addition to systemic inflammatory markers and

serum sodium, several other parameters were also found to be

significantly associated with mortality in the present study. These

included low serum magnesium levels, reduced mitral E wave velocity

and a positive family history of DCM. These findings are consistent

with previous studies demonstrating that hypomagnesemia may

increase cardiovascular mortality risk, whereas reduced mitral E

velocity may indicate diastolic dysfunction and worse outcomes, and

that a positive family history is associated with disease

progression and poorer prognosis in pediatric DCM (17-19).

Notably, although mitral E wave velocity has been

previously studied as a diastolic function parameter, its

prognostic role in pediatric DCM remains underexplored.

Bressieux-Degueldre et al (20) did not observe a significant

association between mitral E velocity and mortality in their

pediatric cohort. By contrast, the present study identified a

statistically significant difference in mitral E velocity, with

patients in the deceased group showing lower E wave velocities

compared with survivors (0.78±0.18 vs. 0.94±0.22 m/sec; P=0.031).

This reduction reflects impaired left ventricular relaxation and

diastolic filling in patients with more advanced myocardial

dysfunction, suggesting that this parameter may warrant further

evaluation as a potential prognostic marker in this population.

It is also worth noting that although aortic root

diameter was found to be statistically larger in patients who

succumbed, all measurements were within the normal Z-score range

for age. This difference likely reflects the older mean age of

deceased patients, instead of an independent prognostic

relationship. Since absolute diameters were used in the analysis

without adjustment for age or body surface area, this finding most

likely reflects age-related anatomical variation rather than

clinically significant aortic dilatation. Therefore, this finding

was not interpreted as clinically meaningful.

To the best of our knowledge, the present study was

the first to evaluate both NLR and SII as prognostic indicators in

pediatric DCM. By integrating two distinct inflammatory markers

derived from complete blood count parameters, the present findings

highlight the potential value of systemic inflammation-based

indices in early risk stratification. Given that NLR and SII are

inexpensive, readily accessible and routinely obtained in clinical

practice, their incorporation into the initial assessment of

children with DCM may enhance prognostic evaluation and inform

closer monitoring strategies. These markers may serve as useful

adjuncts to echocardiographic and clinical data, particularly in

resource-limited settings where advanced biomarkers are not readily

available.

Whilst the present study provides important

preliminary insights, several limitations should be acknowledged.

The present study was a retrospective, single-center analysis with

a relatively small cohort, which may limit the generalizability of

the findings. Systemic inflammatory markers were evaluated only at

the time of diagnosis. Therefore, longitudinal trends and the

potential impact of concurrent infections or other inflammatory

conditions could not be assessed. Additionally, due to the limited

number of events, multivariate analysis could not be performed,

restricting the evaluation of independent associations. The

etiological heterogeneity of the cohort, encompassing idiopathic,

post-infectious, genetic and chemotherapy-related cases, may also

have influenced inflammatory responses and outcomes. Despite these

limitations, the present study introduces novel findings and

highlights the need for prospective multicenter research to further

clarify the prognostic role of inflammatory markers in pediatric

DCM. The findings of the present study may also help inform

clinical decision-making by supporting early risk stratification

and identifying children who may benefit from closer monitoring,

timely intensification of therapy or earlier referral to transplant

centers.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrates that

elevated NLR and SII at the time of diagnosis are significantly

associated with increased mortality in pediatric patients with DCM.

These easily accessible and inexpensive inflammatory markers may

serve as complementary tools to traditional clinical assessments,

particularly in settings where advanced laboratory testing is not

readily available. Although further prospective and multicenter

studies are warranted to validate these findings, the present

results highlight the prognostic relevance of systemic inflammation

in pediatric DCM and suggest a potential role for NLR and SII in

early risk stratification. However, since multivariate analysis

could not be performed due to the limited number of events, these

findings should be interpreted as associations rather than evidence

of independent prognostic value. Further prospective multicenter

studies are needed to confirm their utility before they can be

incorporated into routine clinical decision-making.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

SA contributed to study conception, data collection,

statistical analysis, interpretation of results and manuscript

drafting. FA contributed to study design, interpretation of data

and critical manuscript revision. Both authors read and approved

the final manuscript. SA and FA confirm the authenticity of all the

raw data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics

Committee of Marmara University Faculty of Medicine (Istanbul,

Turkey; approval no. 09.2022.463). The requirement for informed

consent was waived due to the retrospective design of the study, in

accordance with the approval granted by the ethics committee.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Mallavarapu A and Taksande A: Dilated

cardiomyopathy in children: Early detection and treatment. Cureus.

14(e31111)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Lipshultz SE, Cochran TR, Briston DA,

Brown SR, Sambatakos PJ, Miller TL, Carrillo AA, Corcia L, Sanchez

JE, Diamond MB, et al: Pediatric cardiomyopathies: Causes,

epidemiology, clinical course, preventive strategies and therapies.

Future Cardiol. 9:817–848. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Amorim S, Campelo M, Moura B, Martins E,

Rodrigues J, Barroso I, Faria M, Guimarães T, Macedo F,

Silva-Cardoso J and Maciel MJ: The role of biomarkers in dilated

cardiomyopathy: Assessment of clinical severity and reverse

remodeling. Rev Port Cardiol. 36:709–716. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar : (In English,

Portuguese).

|

|

4

|

da Rocha Araújo FD, da Lisboa Silva RMF,

Oliveira CAL and Meira ZMA: Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio used as

prognostic factor marker for dilated cardiomyopathy in childhood

and adolescence. Ann Pediatr Cardiol. 12:18–24. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Ahmed M, El Amrousy D, Hodeib H and Elnemr

S: Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio as a predictive and prognostic

marker in children with dilated cardiomyopathy. Cardiol Young.

33:2493–2497. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Malinow I, Fong DC, Miyamoto M, Badran S

and Hong CC: Pediatric dilated cardiomyopathy: A review of current

clinical approaches and pathogenesis. Front Pediatr.

12(1404942)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Murphy SP, Kakkar R, McCarthy CP and

Januzzi JL Jr: Inflammation in heart failure: JACC state-of-the-art

review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 75:1324–1340. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Boulet J, Sridhar VS, Bouabdallaoui N,

Tardif JC and White M: Inflammation in heart failure:

Pathophysiology and therapeutic strategies. Inflamm Res.

73:709–723. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Fu X, Li X, Gao X, Zuo Q, Wang L, Peng H

and Wu J: The association between systemic inflammation markers and

the risk of incident dilated cardiomyopathy: A prospective study of

351,148 participants. Biomarkers. 30:192–199. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Ye Z, Hu T, Wang J, Xiao R, Liao X, Liu M

and Sun Z: Systemic immune-inflammation index as a potential

biomarker of cardiovascular diseases: A systematic review and

meta-analysis. Front Cardiovasc Med. 9(933913)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Uthamalingam S, Patvardhan EA, Subramanian

S, Ahmed W, Martin W, Daley M and Capodilupo R: Utility of the

neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio in predicting long-term outcomes in

acute decompensated heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 107:433–438.

2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Cho JH, Cho HJ, Lee HY, Ki YJ, Jeon ES,

Hwang KK, Chae SC, Baek SH, Kang SM, Choi DJ, et al:

Neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio in patients with acute heart failure

predicts in-hospital and long-term mortality. J Clin Med.

9(557)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Qiu J, Huang X, Kuang M, Wang C, Yu C, He

S, Xie G, Wu Z, Sheng G and Zou Y: Evaluating the prognostic value

of systemic immune-inflammatory index in patients with acute

decompensated heart failure. ESC Heart Fail. 11:3133–3145.

2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Tang Y, Zeng X, Feng Y, Chen Q, Liu Z, Luo

H, Zha L and Yu Z: Association of systemic immune-inflammation

index with short-term mortality of congestive heart failure: A

retrospective cohort study. Front Cardiovasc Med.

8(753133)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Price JF, Kantor PF, Shaddy RE, Rossano

JW, Goldberg JF, Hagan J, Humlicek TJ, Cabrera AG, Jeewa A,

Denfield SW, et al: Incidence, severity, and association with

adverse outcome of hyponatremia in children hospitalized with heart

failure. Am J Cardiol. 118:1006–1010. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Yoo BS, Park JJ, Choi DJ, Kang SM, Hwang

JJ, Lin SJ, Wen MS, Zhang J and Ge J: COAST investigators.

Prognostic value of hyponatremia in heart failure patients: An

analysis of the clinical characteristics and outcomes in the

relation with serum sodium level in asian patients hospitalized for

heart failure (COAST) study. Korean J Intern Med. 30:460–470.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Adamopoulos C, Pitt B, Sui X, Love TE,

Zannad F and Ahmed A: Low serum magnesium and cardiovascular

mortality in chronic heart failure: A propensity-matched study. Int

J Cardiol. 136:270–277. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Playford D, Strange G, Celermajer DS,

Evans G, Scalia GM, Stewart S and Prior D: NEDA Investigators.

Diastolic dysfunction and mortality in 436 360 men and women: The

national echo database Australia (NEDA). Eur Heart J Cardiovasc

Imaging. 22:505–515. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Khan RS, Pahl E, Dellefave-Castillo L,

Rychlik K, Ing A, Yap KL, Brew C, Johnston JR, McNally EM and

Webster G: Genotype and cardiac outcomes in pediatric dilated

cardiomyopathy. J Am Heart Assoc. 11(e022854)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Bressieux-Degueldre S, Fenton M, Dominguez

T and Burch M: Exploring the possible impact of echocardiographic

diastolic function parameters on outcome in paediatric dilated

cardiomyopathy. Children (Basel). 9(1500)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|