1. Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) was the third leading

cause of cancer-related mortality in 2020, with ~905,000 new cases

and 830,000 deaths worldwide (1).

The incidence remains the highest in East Asia and Africa, but is

increasing in Western nations. In total, ~54% cases are caused by

chronic hepatitis B infection, whereas 15% are caused by hepatitis

C. Alcohol abuse, aflatoxin, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis and

metabolic syndrome-related diabetes are also contributing factors

(2,3). The male predominance (2-3:1) in

hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) suggests gender-specific differences

in exposure to risk factors like chronic viral infections and

alcohol consumption, which may contribute to the higher incidence

in men (2).

Autophagy is a cellular self-digestion process that

serves to maintain homeostasis by degrading damaged organelles and

macromolecules through the lysosomes. In cancer, autophagy serves

complex, context-dependent roles, suppressing tumor initiation by

removing harmful cellular components, but can also promote the

survival of established tumors under stress (4,5).

Starvation-induced non-selective macroautophagy randomly engulfs

the cytoplasm and generates nutrients through indiscriminate

lysosomal breakdown (5). Selective

autophagy uses cargo receptors containing LC3-interacting regions,

such as sequestosome 1 (p62), nuclear dot protein 52 kDa or nuclear

receptor coactivator 4 (NCOA4), to bind ubiquitin-tagged substrates

(such as damaged mitochondria, ferritin and aggregates) and recruit

phagophores exclusively to them. This receptor-guided precision

allows for organelle-specific quality control whilst minimizing

biomass loss and can be adjusted independently of bulk autophagy

(6,7). HCC frequently exhibits dysregulated

autophagy (4,5). Selective autophagy involves the

autophagic targeting of specific intracellular organelles or

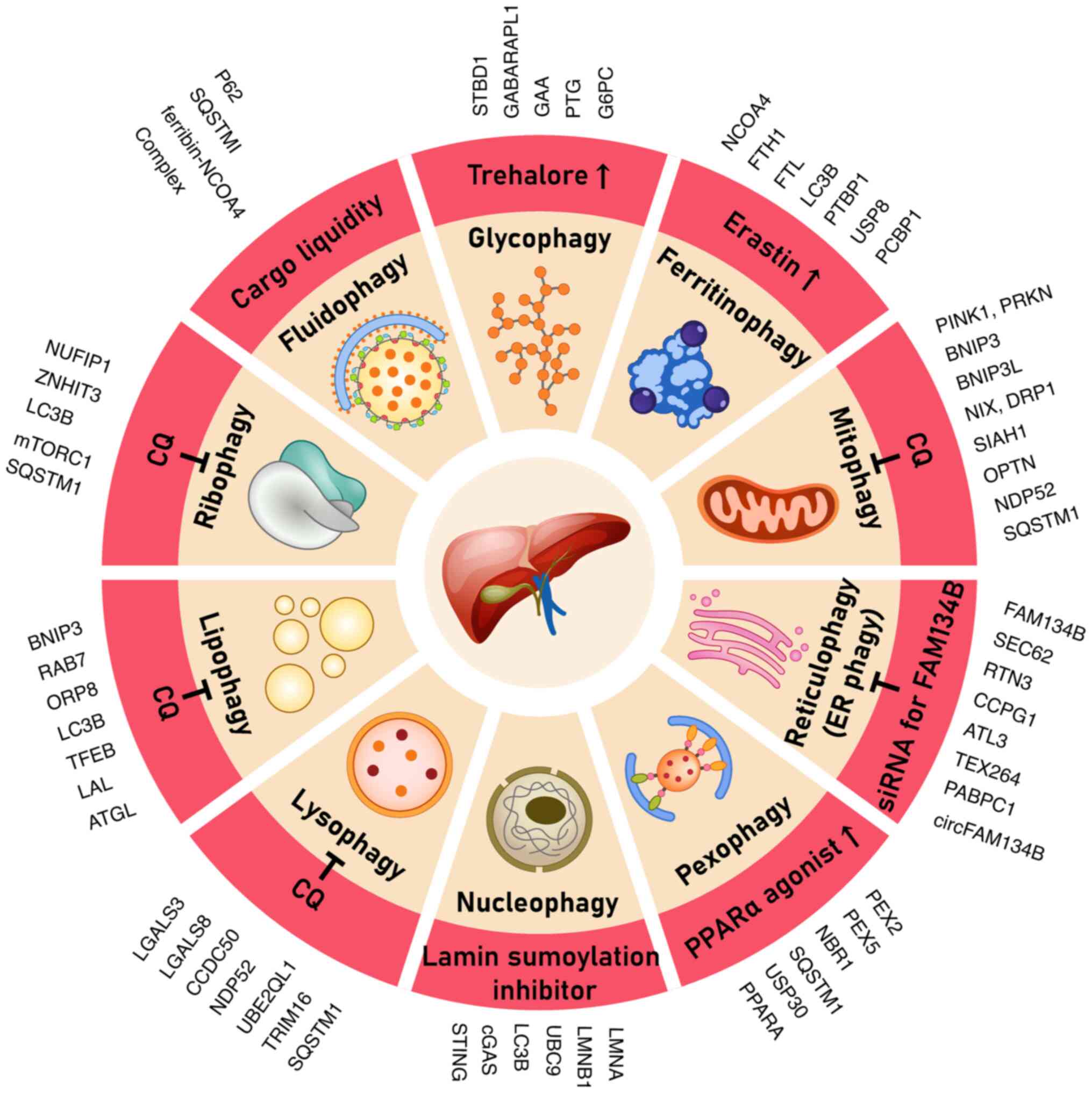

materials. Key forms of autophagy (Table I) include mitophagy (mitochondria)

(8-11),

lysophagy (lysosomes) (10,12),

reticulophagy [endoplasmic reticulum (ER)] (9,13),

pexophagy (peroxisomes) (14),

nucleophagy (nucleus) (15),

ribophagy (ribosomes) (16,17),

lipophagy (lipid droplets) (11,17-19),

glycophagy (glycogen) (19,20),

ferritinophagy (ferritin/iron) (13,21)

and fluidophagy (autophagy of phase-separated liquid condensates

(18-22).

Each of the aforementioned processes has been implicated in the

pathogenesis and therapeutic response in HCC. Target regulators and

therapeutic agents unique to each type of selective autophagy are

shown in Fig. 1.

| Table IExperimental findings in selective

autophagy in HCC. |

Table I

Experimental findings in selective

autophagy in HCC.

| Autophagy type | Key experimental

findings | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Mitophagy | • PINK1/Parkin

inhibition leads to dysfunctional mitochondria and increased

apoptosis | (8) |

| | • High mitophagy

gene expression correlates with worse survival | (8) |

| | • Parkin-mediated

mitophagy supports cancer stem cells and neutralizes p53 | (8) |

| Lysophagy | •

Sorafenib-resistant HCC cells rely on lysophagy; polyphyllin D

disrupts this process, causing cell death | (12) |

| | • UBE2QL1 knockdown

leads to damaged lysosome accumulation, sensitizing cells to

lysosomal death | (12) |

| Reticulophagy | • Sorafenib

activates FAM134B-mediated ER-phagy, protecting against

ferroptosis | (34) |

| | • FAM134B knockdown

enhances ferroptotic cell death | (9) |

| | • circFAM134B

silencing enhances lenvatinib-induced ferroptosis | (34) |

| Pexophagy | • Oxidative stress

triggers peroxisomal protein ubiquitination and p62/NBR1-mediated

clearance | (14) |

| | • Blocking

autophagy leads to dysfunctional peroxisome accumulation and DNA

oxidation | (14) |

| | • HCC cells may use

pexophagy to shift metabolism toward mitochondria | (14) |

| Nucleophagy | • Autophagy

degrades micronuclear DNA via cGAS-LC3 interaction, reducing STING

signaling | (15) |

| | • Autophagy

inhibition increases cytosolic DNA and interferon signaling | (15) |

| | • cGAS-STING can

trigger autophagy-dependent cell death under severe telomere

damage | (15) |

| Ribophagy | • Nutrient

starvation/mTORC1 inhibition relocates NUFIP1 to ribosomes, driving

degradation | (17) |

| | • Blocking

autophagy during nutrient deprivation reduces HCC cell

survival | (17) |

| | • Ribophagy may

help cells remove stalled ribosomes and adapt to stress | (17) |

| Lipophagy | • Autophagy

dysfunction leads to lipid accumulation and HCC development | (18) |

| | • Blocking

autophagy causes lipid droplet buildup and energy depletion | (19) |

| | • BNIP3-driven

lipophagy restrains tumor growth; low BNIP3 yields lipid-rich

tumors | (30) |

| Glycophagy | • STBD1/PTG loss

sensitizes HCC cells to glucose withdrawal | (19) |

| | • Autophagy

inhibition reduces glucose output during fasting | (20) |

| | • G6PC deficiency

impairs glycophagy, leading to adenomas/HCC | (64) |

| Ferritinophagy | • NCOA4 releases

iron from ferritin, enabling ferroptosis | (13) |

| | • NCOA4

overexpression increases labile iron and slows tumor growth | (49) |

| | • PTBP1 silencing

upregulates NCOA4 and sensitizes tumors to sorafenib | (13) |

| Fluidophagy | • Optineurin/NDP52

form droplets on damaged mitochondria to facilitate clearance | (22) |

| | • p62 forms liquid

droplets that sequester ubiquitinated proteins | (22) |

| | • In

autophagy-deficient tumors, p62 aggregates activate NRF2, promoting

tumorigenesis | (18) |

In this review work, PubMed and Google Scholar were

searched for entries added between January 2015 and March 2025 with

Boolean strings combining ‘selective autophagy’, ‘hepatocellular

carcinoma’ and each pathway name (such as ‘mitophagy’ and

‘ferritinophagy’) for a narrative-review approach. In addition, the

reference lists of the retrieved articles were hand-screened. The

inclusion criteria were as follows: English-language primary data

or systematic reviews detailing mechanisms, biomarkers or

therapeutic manipulation of selective autophagy in HCC or liver

models. The exclusion criteria were non-HCC cancers, conference

abstracts without the full text, studies lacking mechanistic

details and commentaries. Two authors independently screened

titles/abstracts, and any disagreements were resolved by a third

reviewer. Data on the pathway effectors, experimental design and

translational relevance were extracted and tabulated to ensure

consistency.

2. Mitophagy in HCC

Mitophagy is the selective autophagic removal of

mitochondria that is critical for mitochondrial quality control.

This is primarily mediated by the phosphatase and tensin

homolog-induced kinase 1 (PINK1)/Parkin pathway, wherein PINK1

accumulates in depolarized mitochondria and recruits Parkin to tag

the mitochondria for autophagy (23,24).

In HCC, Parkin expression is frequently lost or reduced

(downregulated in ~50% HCC tumors) (25). Previous studies have identified

siah E3 ubiquitin protein ligase 1 (SIAH1) as a key Parkin

substitute in HCC. Specifically, SIAH1 can cooperate with PINK1 to

ubiquitinate mitochondrial proteins and initiate mitophagy

(26,27).

Sorafenib-induced mitophagy serves as a

cytoprotective mechanism, clearing drug-damaged mitochondria and

preventing the excess accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS)

(26). Sorafenib actively induces

mitophagy as a defense mechanism against HCC, by inducing PINK1

accumulation and Parkin recruitment to damaged mitochondria, in

turn activating mitophagy in HCC cells. Inhibition or silencing of

PINK1 or SIAH1 has been found to suppress mitophagy and increase

sorafenib-induced cell death, confirming their role as a

cytoprotective component (28,29).

In orthotopic Huh7 xenografts, combining sorafenib with the

dynamin-related protein 1 (DRP1) inhibitor mdivi-1 (50 mg/kg) was

observed to cut tumor volume by 63 vs. 41% for sorafenib

monotherapy, indicating that blocking mitophagy can magnify

sorafenib lethality (30).

Consequently, HCC cells can survive more readily after sorafenib

treatment when mitophagy remains intact. Although basal mitophagy

can prevent liver tumor initiation by removing dysfunctional

ROS-producing mitochondria in established HCC, it frequently

promotes tumor cell metabolism and therapy resistance (5). Chemotherapy (such as cisplatin) has

been reported to induce mitophagy in surviving HCC cells through

DRP1-mediated mitochondrial fission (31). Inhibiting DRP1 with mdivi-1 can

block this mitophagy and increase the apoptosis of

cisplatin-treated HCC cells (31).

Excessive mitophagy activation has been explored as

a therapeutic strategy for inducing HCC cell death (Table II). The iron chelator deferiprone

triggers PINK1/Parkin-independent mitophagy in liver cells and

slows HCC tumor growth in mice, presumably by forcing mitochondrial

turnover and compromising tumor bioenergetics (8). Chronic hepatitis B virus infection, a

major etiological factor of HCC, can influence mitophagy (32,33).

Hepatitis B virus X protein has been shown to induce NIP3-like

protein X-dependent mitophagy in liver cells, which reprograms

metabolism towards glycolysis to enhance cancer stem cell

properties (34).

| Table IITherapeutic strategies for selective

autophagy in HCC. |

Table II

Therapeutic strategies for selective

autophagy in HCC.

| Autophagy type | Therapeutic

targets/strategies |

Mechanism/rationale | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Mitophagy | • Parkin/PINK1

pathway inhibition | • Increases

dysfunctional mitochondria, ROS and apoptosis | (8) |

| | •

Chloroquine/Hydroxychloroquine | • Prevents

autolysosome formation, increases mitochondrial ROS | (10) |

| | • AMPK activators

(Metformin) | • Removes damaged

mitochondria, reduces steatosis | (11) |

| | • BNIP3

upregulation | • Triggers

excessive mitophagy and cell death | (9) |

| Lysophagy | • ASM inhibitors

(Desipramine) | • Destabilizes

lysosomes, mimicking polyphyllin D effects | (10,12) |

| | • Lysosomal BH3

mimetics (BMH-21) | • Activates

autophagy to overwhelm lysosomes | (10) |

| | • TFEB activators

(Trehalose) | • Increases

lysosome biogenesis, generates autophagy trap | (10) |

| | • Lysosomal pH

alkalinizers | • Impairs

degradation, causing substrate accumulation | (10) |

| Reticulophagy | • FAM134B

inhibition | • Enhances

sorafenib-induced ferroptosis | (9) |

| | • PABPC1

inhibitors | • Reduces FAM134B

translation and ER-phagy | (9) |

| | • Ferroptosis

inducers + autophagy inhibitors | • Prevents

ferroptosis mitigation via ER-phagy | (9) |

| Pexophagy | • USP30

inhibitors | • Increases

peroxisome ubiquitination and clearance | (14) |

| | • ROS inducers +

autophagy inhibitors | • Forces peroxisome

damage accumulation | (14) |

| | • PPARα agonists +

autophagy inhibitors | • Increases

peroxisome load then blocks turnover | (14) |

| Nucleophagy | • STING agonists +

autophagy inhibitors | • Amplifies innate

immune activation by sustaining STING signals | (15) |

| | • Immune checkpoint

inhibitors + autophagy inhibitors | • Promotes

immunogenic cell death via DNA release | (15) |

| | • p53 reactivators

+ mTOR inhibitors | • Induces death in

genomically unstable cells | (15) |

| Ribophagy | • mTORC1

inhibitors | • Induces autophagy

including ribophagy | (16) |

| | • Dual PI3K/mTOR

inhibitors + autophagy blockers | • Traps

non-functional ribosomes in autophagosomes | (16) |

| | • NUFIP1/ZNHITE3

disruptors | • Prevents ribosome

clearance during stress | (17) |

| Lipophagy | • Autophagy

inhibitors in NAFLD-HCC | • Blocks fat

mobilization, causing energy deficit | (17-19) |

| | • AMPK activators +

autophagy inhibitors | • Creates autophagy

trap during peak lipid mobilization | (11) |

| | • DGAT1/2

inhibitors + autophagy blockers | • Prevents

triglyceride formation, increasing toxic free fatty acids | (11) |

| Glycophagy | • Glycogen

phosphorylase inhibitors + autophagy blockers | • Redirects to

lysosomal route then blocks it, causing energy crisis | (19) |

| | • STBD1

stabilizers | • Increases

glycogen autophagy beyond handling capacity | (19) |

| | • Glucose

restriction/SGLT2 inhibitors | • Forces tumors to

consume internal glycogen | (19,20) |

|

Ferritinophagy/ | • NCOA4

upregulation | • Increases iron

release from ferritin | (13) |

| Ferroptosis | • Ferroptosis

inducers | • Promotes

iron-dependent lipid peroxidation | (13) |

| | • Iron

mobilizers | • Primes cells for

ferroptosis | (13,21) |

In summary, mitophagy in HCC appears to have a dual

role. It can either protect cells by clearing damaged mitochondria

(limiting oxidative stress and cell death) or enable tumor survival

under treatments, such as kinase inhibitors or chemotherapy

(5,31). Therapeutically, mitophagy can be

manipulated by inhibition (to prevent tumor cells from escaping

apoptosis during therapy) or overactivation (to induce metabolic

crisis in tumors) (8,31).

3. Lysophagy in HCC

Lysophagy is the selective removal of lysosomes

damaged by autophagy. When lysosomal membranes are compromised,

cells can target these leaky lysosomes for autophagic degradation

to prevent the release of hydrolytic enzymes into the cytosol

(9). The process involves damage

recognition by cytosolic galectins (whereby galectin-3/8 binds to

exposed luminal glycans on ruptured lysosomes) and the

ubiquitination of lysosomal membrane proteins, followed by the

recruitment of autophagy receptors (35,36).

Recently, coiled-coil domain containing 50 (CCDC50)

was identified as a dedicated lysophagy receptor in human melanoma

cells (9). CCDC50 can bind to

galectin-3-decorated K63-ubiquitinated lysosomes and facilitate

their clearance through autophagy (9). In HCC, CCDC50 serves a

tumor-promoting role by sustaining lysosomal homeostasis. It was

previously shown that CCDC50 expression is upregulated in HCC

tumors and cell lines, where its high expression associates with

more aggressive tumor features and worse patient prognosis

(9).

Functionally, CCDC50 loss led to the accumulation of

broken lysosomes in HCC cells, impaired autophagic flux, elevated

ROS levels and cell death (9). In

mouse models, CCDC50 deficiency was found to significantly suppress

HCC tumor growth, presumably due to the cytotoxic buildup of

dysfunctional lysosomes and oxidative damage (9). Therapeutically, inhibiting lysophagy

could harm cancer cells by allowing lysosomal damage to accumulate.

Polyphyllin D has been observed to cause lysosomal membrane

permeabilization in HCC cells, resulting in the loss of lysophagy

and spillage of enzymes to trigger cell death (37). Lysosome-targeting agents, such as

chloroquine or the palmitoyl-protein thioesterase 1 (PPT1)

inhibitor GNS561, can effectively kill HCC cells by overwhelming

the lysosomal system (38). GNS561

(ezurpimtrostat) showed potent anti-tumor activity in preclinical

HCC models and has since entered clinical trials (39).

Overall, these aforementioned findings suggest that

lysophagy allows HCC cells to maintain the functionality of their

digestive organelles. Disruption of lysophagy (either genetically

or with lysosomotropic drugs) will likely cause catastrophic

lysosomal failure and tumor suppression (9,37).

4. Reticulophagy (ER-phagy) in HCC

Reticulophagy is the selective autophagic

degradation of portions of the ER. Several ER-resident receptor

proteins [family with sequence similarity 134 member B (FAM134B),

SEC62 homolog, preprotein translocation factor (SEC62), reticulon 3

(RTN3) and cell cycle progression 1 (CCPG1)] can mediate

reticulophagy by binding LC3/γ-aminobutyric acid

receptor-associated protein (GABARAP), a type B autophagy-related

gene 8 family protein receptor, to form autophagosomes and capture

ER fragments (40). FAM134B is a

critical ER-phagy receptor that binds to LC3 through a conserved

LIR motif and selectively fragments the ER membrane for autophagic

engulfment (40).

Sorafenib induces ER stress and activates

FAM134B-dependent reticulophagy (41). Liu et al (41) reported that sorafenib can stimulate

ER-phagy through FAM134B, potentially mitigating the cytotoxicity

of sorafenib. FAM134B knockdown blocked ER-phagy and enhanced

sorafenib-induced ferroptosis in HCC cells (40). Intact FAM134B-mediated

reticulophagy was protective because it contains ER components,

including misfolded proteins, calcium-overloaded ER fragments, and

damaged ER membranes, along with oxidized lipids and proteins

generating ROS, that contribute to oxidative stress and ferroptosis

(40).

A recent study on the circular (circ)RNA of the

FAM134B gene (circFAM134B) showed that this circRNA increases

FAM134B expression and promotes ER-phagy, leading to the

suppression of ferroptosis in HCC cells treated with lenvatinib.

Silencing circFAM134B increased the sensitivity of HCC cells to

Lenvatinib (40). From a

therapeutic perspective, inhibiting FAM134B-mediated ER-phagy may

be beneficial by eliminating ferroptosis in tyrosine kinase

inhibitor-treated tumors (40).

This hypothesis is based on the observation that FAM134B knockdown

potentiated sorafenib and lenvatinib lethality in preclinical

models (40).

5. Pexophagy in HCC

Pexophagy is the selective autophagic degradation of

peroxisomes. Peroxisomes are vital organelles involved in lipid

metabolism, ROS detoxification, biosynthesis of bile acids and

plasmalogens (42). Quality

control of peroxisomes is essential because dysfunctional

peroxisomes can produce excessive ROS and toxic byproducts.

Pexophagy removes surplus or damaged peroxisomes to maintain the

cellular redox balance (5).

Pexophagy malfunction leads to peroxisomal

accumulation, which is associated with oxidative stress and

inflammation in the liver (43).

In catalase-knockout mice, extended fasting triggered excessive

pexophagy and hepatocyte cell death (44). This suggests that under conditions

of high oxidative stress burden, pexophagy may be activated to the

point of cell death, a mechanism potentially relevant in chronic

liver disease and HCC development (5).

To the best of our knowledge, direct studies of

pexophagy in HCC are sparse. However, analyses of HCC tissues have

revealed the dysregulation of peroxisomal proteins and redox

imbalance, which could be partly due to altered pexophagic activity

(5). Pexophagy in HCC remains

underexplored therapeutically. Peroxisome proliferator-activated

receptor-α agonists (such as clofibrate) can induce peroxisome

proliferation and subsequent pexophagy in the liver, such that they

trigger pexophagy in fatty liver contexts (45). Another approach is to target

autophagy adapters, such as neighbor of BRCA1 gene 1 protein which,

along with p62, can act as receptors for ubiquitinated peroxisomes

to enhance the efficiency of pexophagy (46).

6. Nucleophagy in HCC

Nucleophagy is the selective autophagic degradation

of nuclear material. In mammalian cells, nucleophagy is less common

but has been observed during senescence and after DNA damage

(21). One key mechanism described

in cancer cells is DNA damage-induced nucleophagy through lamin

tagging (21). Nucleophagy excises

and degrades damaged nuclear constituents when chromatin breaks or

lamin scaffolds become irreparable. During this process,

SUMO-modified lamin A/C binds to LC3, allowing autophagosomes to

sequester micronuclei or ruptured envelope fragments for lysosomal

digestion (47). In hepatocytes,

inhibiting lamin A/C SUMOylation increases γ-H2AX foci and

micronuclei, reflecting elevated DNA damage. Activation of

nucleophagy mitigates this damage by removing damaged nuclear

components, thereby preserving genome stability. However, this

protective process may allow tumor cells to survive genotoxic

stress. Cells do not necessarily die immediately, because

nucleophagy selectively engulfs and digests damaged nuclear

material, maintaining nuclear integrity and cellular viability

despite persistent DNA lesions. Consequently, nucleophagy functions

as a double-edged sword, limiting DNA-damage signaling while

potentially promoting tumor cell survival (21).

Li et al (21) demonstrated that when DNA damage

causes small fragments of DNA to leak from the nucleus, the cell

responds by SUMOylating nuclear lamin A/C through the E2 enzyme

ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2 I. SUMOylation creates a signal

that recruits LC3, effectively bridging the nuclear lamina to the

autophagosome (21). In the

context of HCC, direct evidence of nucleophagy is limited. However,

the liver tumor environment such as DNA-damaging chemotherapeutic

agents, metabolic stress or lamina deformations, trigger

nucleophagy in HCC. HCC cells are frequently exposed to genotoxic

stress, which can result in double-stranded DNA breaks and

micronucleus formation (21,47).

From a therapeutic standpoint, targeting nucleophagy

is challenging because it is not well defined and can harm normal

cells. One potential angle is that inhibiting SUMOylation can block

nucleophagy and perhaps make HCC cells more prone to accumulating

nuclear damage, leading to cell death.

7. Ribophagy in HCC

Ribophagy involves the selective autophagic

degradation of ribosomes. During nutrient starvation, cells degrade

their ribosomes to recycle amino acids and nucleotides (48). Autophagy-dependent degradation of

ribosomal RNA has been shown to be crucial for maintaining

nucleotide pools during development (13). During metabolic stress, ribophagy

dismantles superfluous or stalled ribosomes to recycle nucleotides

and amino acids. Starvation or mTOR1 inhibition drives nuclear

FMR1-interacting protein 1 (NUFIP1) from the nucleoplasm to the 60S

subunits, where its LC3-interacting region, aided by zinc finger

HIT domain-containing protein 3, targets ribosomes to

autophagosomes, whereas concurrent p62 recruitment clears

ubiquitinated ribosomal proteins (49). Suppressing NUFIP1 in

nutrient-deprived HCC cells heightens proteotoxic stress, ATP

depletion and apoptosis, underscoring the role of ribophagy in

balancing translation load and energy supply (49). Direct studies on the role of

ribophagy in HCC are lacking. However, given that solid tumors

frequently experience nutrient-poor and hypoxic microenvironments,

it is conceivable that HCC cells can invoke ribophagy as an

adaptive mechanism. A study has previously shown that blocking

late-stage autophagy with chloroquine similarly impaired ribophagic

recycling in HCC cells (22). From

a functional standpoint, ribophagy in HCC could contribute to

therapy resistance, where when exposed to metabolic stress (such as

glycolysis inhibitors or anti-angiogenic therapy), HCC cells may

digest ribosomes and survive longer.

8. Lipophagy in HCC

Lipophagy is the autophagic degradation of lipid

droplets. In liver cells, lipophagy is crucial for mobilizing

stored triglycerides and cholesterol esters, delivering them to

lysosomes where lipases break them down to free fatty acids

(50). This process is central to

energy homeostasis. In the context of liver disease and HCC,

lipophagy has significant implications in counteracting lipid

accumulation (51).

In HCC tumors, lipophagy appears to have a

context-dependent role. Cancer cells can use lipophagy to tap into

lipid droplet reserves to meet energy demands (4). During starvation or therapy-induced

nutrient stress, HCC cells can upregulate factors, such as

CCAAT/enhancer binding protein α, enhancing lipophagy to release

fatty acids from lipid droplets to sustain ATP production (4).

Conversely, lipophagy can act as a tumor-suppressive

mechanism by preventing excessive lipid accumulation and

lipotoxicity. Preventing lipotoxicity suppresses tumors because

BCL2-interacting protein 3 (BNIP3)-mediated lipophagy tethers lipid

droplets to autophagosomes, ensuring their degradation. By clearing

excess lipids, this process avoids lipid-driven energy supply and

toxic lipid accumulation, restraining tumor growth. Loss of BNIP3

leads to lipid-rich tumors and poorer survival, underscoring

lipophagy's tumor-suppressive role. Chen et al (34) previously showed that BNIP3 can

tether lipid droplets to autophagosomes through LC3 binding in a

process termed ‘mitolipophagy’, which restrained HCC development.

In a genetic HCC mouse model, loss of BNIP3 led to the earlier

development of larger tumors that contained markedly more lipid

droplets (51).

In human HCC specimens, low BNIP3 expression has

been associated with higher lipid content in tumors and poor

patient survival (51). These

findings indicate that insufficient lipophagy (at least in part due

to BNIP3 inactivation) can promote HCC progression by allowing

lipids to accumulate and fuel tumor growth (51). Therapeutically, there are two

potential strategies: Inhibition of lipophagy to starve HCC cells

or enhancement of lipophagy to induce lipotoxic stress in tumors.

It has been previously demonstrated that combining an autophagy

inhibitor (e.g., chloroquine or its analog hydroxychloroquine) with

a metabolic stressor increased lipid accumulation and cell death in

HCC (22,38).

9. Glycophagy in HCC

Glycophagy is the selective autophagy of glycogen.

The liver is the main storage site for glycogen, where in addition

to canonical cytosolic glycogenolysis, hepatocytes possess a

lysosomal route to degrade glycogen. This pathway is mediated by

starch-binding domain-containing protein 1, which binds glycogen

and recruits it to the autophagosome by interacting with

γ-aminobutyric acid receptor-associated protein-like 1(52). Inside lysosomes, glycogen is broken

down by acid α-glucosidase (52).

In HCC, the role of glycophagy is not well

characterized but is likely relevant, given that numerous HCC cells

exhibit metabolic flexibility and the ability to store glucose as

glycogen (53). HCC cells may

invoke glycophagy when extracellular glucose is scarce. During

transarterial embolization therapy, which induces acute nutrient

starvation in the tumor region, cancer cells can survive by

consuming their glycogen through autophagy (53). Previous studies have shown that

depriving HCC cells of glucose triggers autophagy activation

(26,53). Therapeutically, targeting

glycophagy is challenging. A conceivable approach during

transarterial embolization or fasting-mimicking diet therapy for

HCC is to add an agent that stimulates glycophagy to rapidly

deplete tumor glycogen, thereby rendering the nutrient cut-off more

lethal to cancer cells.

10. Ferritinophagy in HCC

Ferritinophagy is the selective autophagy of

ferritin, a cellular iron storage complex. This process is mainly

mediated by the cargo receptor NCOA4, which binds to ferritin and

delivers it to autophagosomes (54). Through ferritinophagy, iron stored

in ferritin can be released upon lysosomal degradation, increasing

the labile iron pool within the cell (54). Ferritinophagy links autophagy to

iron homeostasis and ferroptosis, which is a form of cell death

caused by iron-dependent lipid peroxidation.

Aberrant iron metabolism is common in HCC. Previous

studies have indicated that ferritinophagy serves a role in HCC

cell death and survival (10,55).

The induction of ferritinophagy can kill HCC cells by ferroptosis.

NCOA4 mediates ferritinophagy, targeting ferritin for lysosomal

degradation to release stored iron. This NCOA4-driven iron

liberation expands the cellular labile iron pool, providing

redox-active Fe²+ that catalyzes ROS generation through

Fenton chemistry (56). The

resulting oxidative stress triggers the peroxidation of

polyunsaturated fatty acids in membranes, which is a hallmark of

ferroptosis (10).

Mechanistically, NCOA4-mediated ferritinophagy sensitizes cells to

ferroptosis by elevating catalytic iron and accelerating lethal

lipid peroxide accumulation. Consistently, inducing ferritinophagy

(such as by caryophyllene oxide) increases free Fe²+ and

malondialdehyde levels (a lipid peroxidation product), whereas

NCOA4 knockdown or interfering with NCOA4-ferritin binding prevents

iron release and protects cells from ferroptotic damage (42). In addition, suppression of NCOA4 or

its regulator, polypyrimidine tract-binding protein 1 (PTBP1), can

reduce the labile iron pool and lipid peroxidation, blunting

ferroptotic death (43).

Therefore, NCOA4-driven ferritinophagic iron release is a pivotal

trigger of ferroptosis through labile iron accumulation and

subsequent ROS-mediated lipid peroxidation. In an in vitro

study, caryophyllene-oxide treatment (20 µM; 6 h) doubled the

extent of NCOA4-ferritin co-localization in Hep3B cells, raised

calcein-quenchable Fe²+ by 42% and increased

malondialdehyde by 2.5X. By contrast, NCOA4 knockdown abolished

iron release and rescued 60% cells from cell death (54).

Another study by Yang et al (57) identified a pathway involving PTBP1

that can regulate ferritinophagy and ferroptosis in HCC.

Specifically, PTBP1 can bind to NCOA4 mRNA to enhance its

translation, where the knocking down PTBP1 expression in

sorafenib-treated HCC cells led to lower NCOA4 levels, reducing

free iron and malondialdehyde levels whilst increasing glutathione

levels, suppressing ferroptosis (57). Simultaneously, PTBP1 depletion

lowered NCOA4 by 48 %, shrank the labile iron pool by 35 % and

suppressed erastin-induced ferroptosis in MHCC-97H xenografts

(57). However, ferritinophagy may

also help HCC cells survive under certain conditions by providing

iron for essential enzymes. A recent report on pancreatic cancer

has shown that NCOA4-mediated ferritinophagy is required for tumor

growth by supplying iron to the proliferating cells (58).

Induction of excessive ferritinophagy appears to be

a promising therapeutic approach for HCC, essentially pushing cells

into ferroptosis, which is a lethal oxidative form of cell death

that cancer cells cannot easily reverse. Various compounds, such as

artesunate, sorafenib and caryophyllene oxide, can induce

ferroptosis, at least partly by increasing free iron levels either

through ferritinophagy or direct iron import (54).

11. Fluidophagy in HCC

Fluidophagy is a relatively novel term, describing

the autophagic degradation of fluid-like, phase-separated

intracellular condensates (59).

Cells contain numerous non-membrane-bound organelles that behave as

liquid droplets. A number of biophysical studies have previously

shown that the ‘wetting’ properties of droplets on autophagosome

membranes are crucial (60-62).

This process of droplet autophagy has been named ‘fluidophagy’

(59,63). At present, fluidophagy is a

mechanistic insight into selective autophagy, rather than a

distinct pathway with unique regulators.

For HCC, the biophysical state of the cargo (solid

aggregates vs. liquid droplets) can affect autophagic clearance. In

particular, the NCOA4-ferritin complex, which can form liquid

condensates in the cytosol, helps concentrate ferritin into such

droplets, which are then autophagically consumed (63). In addition, the autophagic

degradation of p62/sequestosome 1 (SQSTM1) bodies is another

possible example of fluidophagy (59).

In HCC, fluidophagy likely underlies the removal of

certain protein aggregates or storage complexes from the cells. HCC

cells frequently accumulate aggregates of p62 and ubiquitinated

proteins (p62 is commonly elevated in HCC and is used as a marker

of autophagic flux) (11).

12. Therapeutic targeting

Dysregulated selective autophagy contributes to HCC

progression and resistance to therapy, making the components of

these pathways attractive therapeutic targets. Strategies to

modulate autophagy in cancer are two-fold: Inhibition (to prevent

tumor cells from recycling organelles and evading death) and

activation (to drive cancer cells into lethal self-digestion).

Inhibiting pro-survival autophagy

HCC has been a prime candidate for autophagy

inhibition trials. Chloroquine (CQ) and hydroxychloroquine, which

inhibit lysosomal acidification and late-stage autophagy, have been

tested in preclinical HCC models and in early clinical studies

(38,39). Combining CQ with chemotherapeutic

oxaliplatin led to more pronounced tumor suppression in HCC

xenografts compared with chemotherapy alone (38). Newer lysosome-targeted agents, such

as GNS561, show even greater potency. GNS561, a PPT1 inhibitor,

accumulates in the lysosomes and blocks autophagy at a late stage,

causing cancer cell death (12).

In HCC models, GNS561 not only killed bulk tumor cells but was also

active against cancer stem cell populations (56). One previous clinical trial tested

hydroxychloroquine with the mTOR inhibitor everolimus in HCC

according to the ‘simultaneous activation and blockade’ strategy,

with disease control reaching 67% (with 6% partial responses) and

45% of patients had ≥6-month progression-free survival (14). Additionally, nutrient modulation,

such as ketogenic or fasting-mimicking diet to induce autophagy in

tumors, followed by autophagy inhibitor administration, is another

reported experimental approach aiming to catch cancer cells in a

vulnerable state (‘autophagy trap’) (15).

Targeting specific autophagy

pathways

A more tailored approach is to target regulators

unique to the selective autophagy types on which HCC depends. The

role of DRP1 in mitophagy in HCC has been proposed. DRP1-driven

mitophagy allows HCC cells to survive chemotherapy, since

inhibiting DRP1 with mdivi-1 was found to sensitize tumors to

cisplatin in mice (31). Another

proposed lysophagy target is CCDC50. Since CCDC50 knockdown causes

HCC cell death and tumor suppression by blocking lysophagy

(9), a drug that inhibits CCDC50

may mimic this tumor-suppressive effect. In the ER-phagy arena,

FAM134B and its regulator circFAM134B are potential targets to

enhance ferroptosis in tumors resistant to tyrosine kinase

inhibitors. An antisense oligonucleotide against circFAM134B was

found to decrease FAM134B levels, impairing ER-phagy and promoting

lenvatinib-induced ferroptosis (40). For lipophagy, one approach is to

restore BNIP3 function in HCC. BNIP3 is frequently silenced

epigenetically in cancers. Therefore, demethylating the BNIP3

promoter or delivering BNIP3 by gene therapy may reinstate

autophagic clearance of lipid droplets, potentially slowing tumor

growth in steatotic HCC (51).

Exploiting ferritinophagy and

ferroptosis

This is a promising novel direction. Ferroptosis

inducers (including sorafenib, sulfasalazine or experimental

agents, such as erastin and RSL3) can be combined with strategies

to increase ferritinophagy. Furthermore, various drugs, such as

caryophyllene oxide, may upregulate NCOA4 and drive ferritinophagy,

since they have shown efficacy in HCC models (54).

Precision considerations

Whether a given autophagy process is inhibited or

induced depends on the tumor context. Early-stage,

well-differentiated HCC may be more vulnerable to autophagy

induction to trigger cell death, whereas late-stage,

therapy-resistant HCC may require autophagy inhibition to remove

its survival crutch (4,5). Biomarkers are being investigated: For

instance, a ‘mitophagy gene signature’ stratifies patients with HCC

and correlates with immune microenvironment differences (16). The mitophagy gene signature is an

eight-gene score derived from core mitophagy regulators (e.g.,

optineurin and ATG12). By calculating a composite expression score

and splitting at the median, it divides patients with HCC into

high-risk and low-risk groups for survival. High scores indicate

aggressive disease and are associated with immunosuppressive tumour

microenvironments-characterised by increased infiltration of

certain immune cells (B cells, CD4/8 T cells, dendritic cells, NK

cells and macrophages) and altered cytokine gene expression. Thus,

the signature not only predicts prognosis but also reflects

differences in immune cell infiltration patterns (16).

13. Biomarkers of autophagy in HCC

Several autophagy-related biomarkers have been

documented to serve prognostic and predictive values for HCC

(Table III).

| Table IIIAutophagy-related biomarkers in

HCC. |

Table III

Autophagy-related biomarkers in

HCC.

| Biomarker | Clinical

findings | (Refs.) |

|---|

| p62/SQSTM1 | • Accumulates in

autophagy-defective HCC | (18,65,66) |

| | • High levels

associate with larger tumors, venous invasion and poor

survival | |

| | • Acts as

oncoprotein through NRF2 activation | |

| LC3B | • Increased

expression associates with superior differentiation and smaller

tumors | (16,67) |

| | • Positive staining

predicts longer survival | |

| | •

Context-dependent: Sometimes indicates high autophagic flux in

advanced HCC | |

| Beclin-1 | • Frequently

downregulated in HCC (17q loss or low transcription) | (68-70) |

| | • Preserved

expression associates with favorable OS and DFS | |

| | • Low levels

associate with poor differentiation and vascular invasion | |

| BNIP3 | • Frequently

silenced in HCC, especially in fatty liver-associated cases | (44) |

| | • Low expression

associates with high lipid content and worse prognosis | |

| | • Higher expression

associated with lower microvascular invasion | |

| NCOA4 | • Emerging

biomarker with higher expression in some HCC tissues | (13,49) |

| | • May predict

response to ferroptosis-inducing therapy | |

| | • Prognostic value

unclear; correlation with iron load needed | |

| p62/LC3 ratio | • High p62/low LC3

indicates autophagy-deficient tumors with poor RFS | (66,67) |

| | • Low p62/high LC3

associated with less aggressive tumors | |

| | • Dual staining

used to gauge autophagy flux | |

| Autophagy gene | • 8-gene mitophagy

score (such as optineurin and ATG12) stratifies HCC prognosis | (72,74) |

| signatures | • Multiple

predictive signatures (6-13 genes) correlate with outcomes | |

| | • High autophagy

gene expression indicates aggressive disease | |

| Immune-autophagy

markers | • High LC3 in

surrounding tissue but low in tumor correlates with recurrence | (10,15) |

| | • Circulating HMGB1

may predict immunotherapy response | |

| | • Links autophagy

status to tumor microenvironment | |

p62/SQSTM1

p62/SQSTM1 frequently accumulates in HCC cells with

defective autophagy. High p62 levels are associated with larger

tumor size, venous invasion and poorer overall survival (17). In addition, p62 can serve as an

oncoprotein through nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2

activation (18).

LC3B

Increased LC3B expression is associated with

increased differentiation and smaller tumor size. A meta-analysis

has previously indicated that positive LC3B immunostaining predicts

longer survival in patients with HCC (19).

Beclin-1

This protein is downregulated in HCCs due to the

monoallelic loss of 17q or low transcription. Patients with

preserved Beclin-1 expression tend to have a more favorable overall

survival and disease-free survival (20).

BNIP3

It is frequently silenced or have its expression

reduced in HCC, particularly in fatty liver-associated HCC. Low

BNIP3 expression is associated with high intracellular lipid levels

and poor prognosis (51).

NCOA4

Initial data have suggested higher NCOA4 mRNA levels

in HCC tissues compared with those in adjacent tissues. It has been

hypothesized that NCOA4-high tumors respond with superior efficacy

to ferroptosis-inducing therapies (51).

p62/LC3 ratio

The combination of high p62 and low LC3 levels in

HCC tumor tissues indicates autophagy-deficient tumors, which are

associated with shorter recurrence-free survival (64).

Autophagy gene signatures

Several prognostic signatures using

autophagy-related genes have been developed to predict recurrence

and overall survival (65). An

eight-gene mitophagy score containing optineurin, ATG12 and related

genes that stratifies patients into high- and low-risk groups and a

series of predictive signatures using 6-13 autophagy genes or gene

pairs (e.g., LC3B/p62/BNIP3). These signatures correlate with

recurrence or overall survival, and higher autophagy-gene

expression generally signifies more aggressive disease (65).

14. Clinical implications and future

directions

Understanding selective autophagy in HCC has

important clinical implications because HCC cells frequently co-opt

organelle-specific recycling to survive hypoxia, metabolic stress

and chemotherapy (51,66). The autophagy status may serve as a

stratification tool to identify patients who can benefit from

autophagy modulation. Tumors with high autophagic flux may be more

vulnerable to autophagy inhibition, whereas those with impaired

autophagy may benefit from strategies that overcome their

compromised degradation systems. Furthermore, late-stage agents,

such as hydroxychloroquine or the lysosomotropic inhibitor GNS561,

can be used to exploit this vulnerability by arresting lysophagy

and bulk flux. GNS561 was found to achieve durable disease control

in a previous phase I clinical study and is advancing to phase II

(30). Targeted inhibition of

pro-survival mitophagy may enhance drug efficacy. Mdivi-1, genetic

PINK1 or PRKN (the Parkin gene) knockdown was found to boost

sorafenib-induced apoptosis by >30 % in xenografts (67).

Conversely, activating death-linked pathways is

equally promising. Agents that stimulate NCOA4-dependent

ferritinophagy (such as caryophyllene oxide) can enlarge the

labile-iron pool, intensifying lipid peroxidation to synergize with

ferroptosis inducers, achieving tumor shrinkage without added

systemic toxicity (54,68). ER-phagy modulation offers

precision, where circFAM134B silencing can disable reticulophagy,

magnifying lenvatinib-triggered ferroptosis in resistant HCC models

(40). Finally, autophagy gene

signatures (LC3B, p62 and BNIP3) are emerging prognostic tools for

stratifying patients according to combination regimens (69). Collectively, these data support a

future in which pathway-specific autophagy modulators, paired with

existing systemic or locoregional therapies can be used to drive

personalized HCC management whilst sparing normal hepatocytes

(70,71).

The concept of ‘synthetic lethality’ is particularly

relevant, identifying genetic or metabolic vulnerabilities in HCC

that, when coupled with autophagy manipulation, can lead to tumor

cell death (53,55,72,73).

HCC tumors with BNIP3 deficiency (and thus impaired

mitophagy/lipophagy) may be particularly sensitive to treatments

that increase lipid or oxidative stress (41,51,74).

Future directions in this field include the

following: i) Development of selective autophagy inhibitors, moving

beyond chloroquine to more targeted agents against specific

autophagy receptors or regulators (4); ii) biomarker-guided therapy, where

autophagy signatures can be used to guide treatment decisions (such

as which patients should receive autophagy inhibitors in addition

to conventional therapy) (75);

iii) Combined metabolic and autophagic targeting, by exploiting the

dependence of HCC on autophagy for metabolic adaptation by

simultaneously targeting metabolic pathways and autophagy (76); iv) local delivery technologies, by

developing liver-targeted delivery systems for autophagy modulators

to minimize systemic effects (77); and v) integration with

immunotherapy, by understanding how selective autophagy influences

tumor immune microenvironments and exploring combinations with

immune checkpoint inhibitors (78).

15. Limitations of the review

The present narrative review has several limitations

that readers should consider. No formal systematic review

methodology with structured database queries or predefined

inclusion/exclusion criteria was applied, which introduced

potential selection bias in the literature citations. Given the

breadth of the field, certain relevant studies may have been

inadvertently omitted, particularly since the primary focus was on

English-language publications in common databases, such as PubMed.

In addition, research on certain selective autophagy pathways in

HCC, such as nucleophagy and ribophagy, is limited, requiring

analogies to be drawn from other contexts or rely on preliminary

data. the majority of the evidence discussed is also only

preclinical, derived from cell lines or animal models rather than

from clinical trials. Although ongoing trials were mentioned, the

proposed therapeutic strategies using autophagy modulators lack

proven clinical efficacy for HCC treatment. These limitations

establish appropriate interpretive boundaries, ensuring the scope

of the present review is within the current preclinical landscape

whilst highlighting areas that require further investigation.

16. Conclusion

The selective autophagy pathways in HCC are emerging

as druggable nodes. By understanding whether a given type of

autophagy supports or hinders tumor growth, interventions can be

designed to tip the balance against cancer. The complexity of

autophagy in HCC highlights the need for personalized approaches.

Some tumors rely on specific autophagy pathways for survival,

whereas others may be suppressed by the same pathways. Therefore,

characterizing the autophagy dependence of individual tumors is

crucial for effective therapeutic interventions. The bidirectional

nature of autophagy, both tumor-promoting and tumor-suppressing,

necessitates careful consideration of the context, timing and

specific pathways when designing therapeutic strategies. As

understanding deepens, selective autophagy modulation promises to

become an important component of personalized HCC treatment. As

research progresses, a promising approach may be to first stress

cancer cells with conventional treatments and then disable their

selective autophagy defenses, thereby driving them into

irrecoverable failure.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: The present review was supported by a grant from Chang

Gung Memorial Hospital (grant no. CORPG8N0241).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

CHH was involved in the conceptualization of the

review, literature search, writing of the manuscript and funding

acquisition. Data authentication is not applicable. The author has

read and agreed to the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The author declares that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M,

Soerjomataram I, Jemal A and Bray F: Global cancer statistics 2020:

GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36

cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 71:209–249.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Llovet JM, Kelley RK, Villanueva A, Singal

AG, Pikarsky E, Roayaie S, Lencioni R, Koike K, Zucman-Rossi J and

Finn RS: Hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers.

7(6)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Ker CG: Hepatobiliary surgery in Taiwan:

The past, present, and future. Part I; biliary surgery. Formosan J

Surg. 57:1–10. 2024.

|

|

4

|

Alim Al-Bari A, Ito Y, Thomes PG, Menon

MB, García-Macia M, Fadel R, Stadlin A, Peake N, Faris ME, Eid N

and Klionsky DJ: Emerging mechanistic insights of selective

autophagy in hepatic diseases. Front Pharmacol.

14(1149809)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Nguyen TH, Nguyen TM, Ngoc DTM, You T,

Park MK and Lee CH: Unraveling the janus-faced role of autophagy in

hepatocellular carcinoma: Implications for therapeutic

interventions. Int J Mol Sci. 24(16255)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Klionsky DJ, Abdel-Aziz AK, Abdelfatah S,

Abdellatif M, Abdoli A, Abel S, Abeliovich H, Abildgaard MH, Abud

YP, Acevedo-Arozena A, et al: Guidelines for the use and

interpretation of assays for monitoring autophagy (4th edition).

Autophagy. 17:1–382. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Vainshtein A and Grumati P: Selective

autophagy by close encounters of the ubiquitin kind. Cells.

9(2349)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Narendra DP, Jin SM, Tanaka A, Suen DF,

Gautier CA, Shen J, Cookson MR and Youle RJ: PINK1 is selectively

stabilized on impaired mitochondria to activate Parkin. PLoS Biol.

8(e1000298)2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Youle RJ and Narendra DP: Mechanisms of

mitophagy. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 12:9–14. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Wang F, Denison S, Lai JP, Philips LA,

Montoya D, Kock N, Schüle B, Klein C, Shridhar V, Roberts LR and

Smith DI: Parkin gene alterations in hepatocellular carcinoma.

Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 40:85–96. 2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Feng J, Zhou J, Wu Y, Shen HM, Peng T and

Lu GD: Targeting mitophagy as a novel therapeutic approach in liver

cancer. Autophagy. 19:2164–2165. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Szargel R, Shani V, Elghani FA, Mekies LN,

Liani E, Rott R and Engelender S: The PINK1, synphilin-1 and SIAH-1

complex constitutes a novel mitophagy pathway. Hum Mol Genet.

25:3476–3490. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Zhou J, Feng J, Wu Y, Dai HQ, Zhu GZ, Chen

PH, Wang LM, Lu G, Liao XW, Lu PZ, et al: Simultaneous treatment

with sorafenib and glucose restriction inhibits hepatocellular

carcinoma in vitro and in vivo by impairing SIAH1-mediated

mitophagy. Exp Mol Med. 54:2007–2021. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Luo P, An Y, He J, Xing X, Zhang Q, Liu X,

Chen Y, Yuan H, Chen J, Wong YK, et al: Icaritin with

autophagy/mitophagy inhibitors synergistically enhances anticancer

efficacy and apoptotic effects through PINK1/Parkin-mediated

mitophagy in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Lett.

587(216621)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Zhang S, Wang Y, Cao Y, Wu J, Zhang Z, Ren

H, Xu X, Kaznacheyeva E, Li Q and Wang G: Inhibition of the

PINK1-parkin pathway enhances the lethality of sorafenib and

regorafenib in hepatocellular carcinoma. Front Pharmacol.

13(851832)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Ma M, Lin XH, Liu HH, Zhang R and Chen RX:

Suppression of DRP1-mediated mitophagy increases the apoptosis of

hepatocellular carcinoma cells in the setting of chemotherapy.

Oncol Rep. 43:1010–1018. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Aman Y, Cao S and Fang EF: Iron out,

mitophagy in! A way to slow down hepatocellular carcinoma. EMBO

Rep. 21(e51652)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Kim SJ, Khan M, Quan J, Till A, Subramani

S and Siddiqui A: Hepatitis B virus disrupts mitochondrial

dynamics: Induces fission and mitophagy to attenuate apoptosis.

PLoS Pathog. 9(e1003722)2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Li Y and Ou JJ: Regulation of

mitochondrial metabolism by hepatitis B virus. Viruses.

15(2359)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Chen YY, Wang WH, Che L, Lan Y, Zhang LY,

Zhan DL, Huang ZY, Lin ZN and Lin YC: BNIP3L-dependent mitophagy

promotes HBx-induced cancer stemness of hepatocellular carcinoma

cells via glycolysis metabolism reprogramming. Cancers (Basel).

12(655)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Jia P, Tian T, Li Z, Wang Y, Lin Y, Zeng

W, Ye Y, He M, Ni X, Pan J, et al: CCDC50 promotes tumor growth

through regulation of lysosome homeostasis. EMBO Rep.

24(e56948)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Eapen VV, Swarup S, Hoyer MJ, Paulo JA and

Harper JW: Quantitative proteomics reveals the selectivity of

ubiquitin-binding autophagy receptors in the turnover of damaged

lysosomes by lysophagy. Elife. 10(e72328)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Hoyer MJ, Swarup S and Harper JW:

Mechanisms controlling selective elimination of damaged lysosomes.

Curr Opin Physiol. 29(100590)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Wang Y, Wang Z, Sun J and Qian Y:

Identification of HCC subtypes with different prognosis and

metabolic patterns based on mitophagy. Front Cell Dev Biol.

9(799507)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Ding ZB, Hui B, Shi YH, Zhou J, Peng YF,

Gu CY, Yang H, Shi GM, Ke AW, Wang XY, et al: Autophagy activation

in hepatocellular carcinoma contributes to the tolerance of

Oxaliplatin via reactive oxygen species modulation. Clin Cancer

Res. 17:6229–6238. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Brun S, Bestion E, Raymond E, Bassissi F,

Jilkova ZM, Mezouar S, Rachid M, Novello M, Tracz J, Hamaï A, et

al: GNS561, a clinical-stage PPT1 inhibitor, is efficient against

hepatocellular carcinoma via modulation of lysosomal functions.

Autophagy. 18:678–694. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Bi T, Lu Q, Pan X, Dong F, Hu Y, Xu Z, Xiu

P, Liu Z and Li J: circFAM134B is a key factor regulating

reticulophagy-mediated ferroptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma.

Cell Cycle. 22:1900–1920. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Liu Z, Ma C, Wang Q, Yang H, Lu Z, Bi T,

Xu Z, Li T, Zhang L, Zhang Y, et al: Targeting FAM134B-mediated

reticulophagy activates sorafenib-induced ferroptosis in

hepatocellular carcinoma. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 589:247–253.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Wu H, Liu Q, Shan X, Gao W and Chen Q: ATM

orchestrates ferritinophagy and ferroptosis by phosphorylating

NCOA4. Autophagy. 19:2062–2077. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Wei X, Manandhar L, Kim H, Chhetri A,

Hwang J, Jang G, Park C and Park R: Pexophagy and oxidative stress:

Focus on peroxisomal proteins and reactive oxygen species (ROS)

signaling pathways. Antioxidants (Basel). 14(126)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Dutta RK, Maharjan Y, Lee JN, Park C, Ho

YS and Park R: Catalase deficiency induces reactive oxygen species

mediated pexophagy and cell death in the liver during prolonged

fasting. Biofactors. 47:112–125. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Ohshima K, Hara E, Takimoto M, Bai Y,

Hirata M, Zeng W, Uomoto S, Todoroki M, Kobayashi M, Kozono T, et

al: Peroxisome proliferator activator α agonist clofibrate induces

pexophagy in coconut oil-based high-fat diet-fed rats. Biology

(Basel). 13(1027)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Deosaran E, Larsen KB, Hua R, Sargent G,

Wang Y, Kim S, Lamark T, Jauregui M, Law K, Lippincott-Schwartz J,

et al: NBR1 acts as an autophagy receptor for peroxisomes. J Cell

Sci. 126:939–952. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Li Y, Jiang X, Zhang Y, Gao Z, Liu Y, Hu

J, Hu X, Li L, Shi J and Gao N: Nuclear accumulation of UBC9

contributes to SUMOylation of lamin A/C and nucleophagy in response

to DNA damage. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 38(67)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Papandreou ME and Tavernarakis N:

Nucleophagy: From homeostasis to disease. Cell Death Differ.

26:630–639. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Cebollero E, Reggiori F and Kraft C:

Reticulophagy and ribophagy: Regulated degradation of protein

production factories. Int J Cell Biol. 2012(182834)2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Liu Y, Zou W, Yang P, Wang L, Ma Y, Zhang

H and Wang X: Autophagy-dependent ribosomal RNA degradation is

essential for maintaining nucleotide homeostasis during C. elegans

development. eLife. 7(e36588)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Wyant GA, Abu-Remaileh M, Frenkel EM,

Laqtom NN, Dharamdasani V, Lewis CA, Chan SH, Heinze I, Ori A and

Sabatini DM: NUFIP1 is a ribosome receptor for starvation-induced

ribophagy. Science. 360:751–758. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Xu F, Tautenhahn HM, Dirsch O and Dahmen

U: Blocking autophagy with chloroquine aggravates lipid

accumulation and reduces intracellular energy synthesis in

hepatocellular carcinoma cells, both contributing to its

anti-proliferative effect. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 148:3243–3256.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Xu C and Fan J: Links between autophagy

and lipid droplet dynamics. J Exp Bot. 73:2848–2858.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Berardi DE, Bock-Hughes A, Terry AR, Drake

LE, Bozek G and Macleod KF: Lipid droplet turnover at the lysosome

inhibits growth of hepatocellular carcinoma in a BNIP3-dependent

manner. Sci Adv. 8(eabo2510)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Koutsifeli P, Varma U, Daniels LJ,

Annandale M, Li X, Neale JPH, Hayes S, Weeks KL, James S, Delbridge

LMD and Mellor KM: Glycogen-autophagy: Molecular machinery and

cellular mechanisms of glycophagy. J Biol Chem.

298(102093)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Gade TPF, Tucker E, Nakazawa MS, Hunt SJ,

Wong W, Krock B, Weber CN, Nadolski GJ, Clark TWI, Soulen MC, et

al: Ischemia induces quiescence and autophagy dependence in

hepatocellular carcinoma. Radiology. 283:702–710. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Xiu Z, Zhu Y, Han J, Li Y, Yang X, Yang G,

Song G, Li S, Li Y, Cheng C, et al: Caryophyllene oxide induces

ferritinophagy by regulating the NCOA4/FTH1/LC3 pathway in

hepatocellular carcinoma. Front Pharmacol.

13(930958)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Wang G, Li J, Zhu L, Zhou Z, Ma Z, Zhang

H, Yang Y, Niu Q and Wang X: Identification of hepatocellular

carcinoma-related subtypes and development of a prognostic model: A

study based on ferritinophagy-related genes. Discov Oncol.

14(147)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Zhou B, Liu J, Kang R, Klionsky DJ,

Kroemer G and Tang D: Ferroptosis is a type of autophagy-dependent

cell death. Semin Cancer Biol. 66:89–100. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Subburayan K, Thayyullathil F,

Pallichankandy S, Cheratta AR, Alakkal A, Sultana M, Drou N, Arshad

M, Palanikumar L, Magzoub M, et al: Tumor suppressor Par-4

activates autophagy-dependent ferroptosis. Commun Biol.

7(732)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Yang H, Sun W, Bi T, Wang Q, Wang W, Xu Y,

Liu Z and Li J: The PTBP1-NCOA4 axis promotes ferroptosis in liver

cancer cells. Oncol Rep. 49(45)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Santana-Codina N, del Rey MQ, Kapner KS,

Zhang H, Gikandi A, Malcolm C, Poupault C, Kuljanin M, John KM,

Biancur DE, et al: NCOA4-Mediated ferritinophagy is a pancreatic

cancer dependency via maintenance of iron bioavailability for

iron-sulfur cluster proteins. Cancer Discov. 12:2180–2197.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Yang Z, Yoshii SR, Sakai Y, Zhang J, Chino

H, Knorr RL and Mizushima N: Autophagy adaptors mediate

Parkin-dependent mitophagy by forming sheet-like liquid

condensates. EMBO J. 43:5613–5634. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Agudo-Canalejo J, Schultz SW, Chino H,

Migliano SM, Saito C, Koyama-Honda I, Stenmark H, Brech A, May AI,

Mizushima N and Knorr RL: Wetting regulates autophagy of

phase-separated compartments and the cytosol. Nature. 591:142–146.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Mangiarotti A, Sabri E, Schmidt KV,

Hoffmann C, Milovanovic D, Lipowsky R and Dimova R: Lipid packing

and cholesterol content regulate membrane wetting and remodeling by

biomolecular condensates. Nat Commun. 16(2756)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Mangiarotti A, Chen N, Zhao Z, Lipowsky R

and Dimova R: Wetting and complex remodeling of membranes by

biomolecular condensates. Nat Commun. 14(2809)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Ohshima T, Yamamoto H, Sakamaki Y, Saito C

and Mizushima N: NCOA4 drives ferritin phase separation to

facilitate macroferritinophagy and microferritinophagy. J Cell

Biol. 221(e202203102)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Cerda-Troncoso C, Varas-Godoy M and Burgos

PV: Pro-tumoral functions of autophagy receptors in the modulation

of cancer progression. Front Oncol. 10(619727)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Brun S, Pascussi JM, Gifu EP, Bestion E,

Macek-Jilkova Z, Wang G, Bassissi F, Mezouar S, Courcambeck J,

Merle P, et al: GNS561, a new autophagy inhibitor active against

cancer stem cells in hepatocellular carcinoma and hepatic

metastasis from colorectal cancer. J Cancer. 12:5432–5438.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Shalhoub H, Gonzalez P, Dos Santos A,

Guillermet-Guibert J, Moniaux N, Dupont N and Faivre J:

Simultaneous activation and blockade of autophagy to fight

hepatocellular carcinoma. Autophagy Rep. 3(2326241)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

58

|

Qian R, Cao G, Su W, Zhang J, Jiang Y,

Song H, Jia F and Wang H: Enhanced sensitivity of tumor cells to

autophagy inhibitors using fasting-mimicking diet and targeted

lysosomal delivery nanoplatform. Nano Lett. 22:9154–9162.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

59

|

Liu C, Wu Z, Wang L, Yang Q and Huang J

and Huang J: A mitophagy-related gene signature for subtype

identification and prognosis prediction of hepatocellular

carcinoma. Int J Mol Sci. 23(12123)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

60

|

Umemura A, He F, Taniguchi K, Nakagawa H,

Yamachika S, Font-Burgada J, Zhong Z, Subramaniam S, Raghunandan S,

Duran A, et al: p62, Upregulated during preneoplasia, induces

hepatocellular carcinogenesis by maintaining survival of stressed

HCC-initiating cells. Cancer Cell. 29:935–948. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

61

|

Saito T, Ichimura Y, Taguchi K, Suzuki T,

Mizushima T, Takagi K, Hirose Y, Nagahashi M, Iso T, Fukutomi T, et

al: p62/Sqstm1 promotes malignancy of HCV-positive hepatocellular

carcinoma through Nrf2-dependent metabolic reprogramming. Nat

Commun. 7(12030)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

62

|

Meng YC, Lou XL, Yang LY, Li D and Hou YQ:

Role of the autophagy-related marker LC3 expression in

hepatocellular carcinoma: A meta-analysis. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol.

146:1103–1113. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

63

|

Qiu DM, Wang GL, Chen L, Xu YY, He S, Cao

XL, Qin J, Zhou JM, Zhang YX and Qun E: The expression of beclin-1,

an autophagic gene, in hepatocellular carcinoma associated with

clinical pathological and prognostic significance. BMC Cancer.

14(327)2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

64

|

Lin CW, Chen YS, Lin CC, Lee PH, Lo GH,

Hsu CC, Hsieh PM, Koh KW, Chou TC, Dai CY, et al: Autophagy-related

gene LC3 expression in tumor and liver microenvironments

significantly predicts recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma after

surgical resection. Clin Transl Gastroenterol.

9(166)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

65

|

Cao J, Wu L, Lei X, Shi K and Shi L: A

signature of 13 autophagy-related gene pairs predicts prognosis in

hepatocellular carcinoma. Bioengineered. 12:697–707.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

66

|

Wang S, Cheng H, Li M, Gao D, Wu H, Zhang

S, Huang Y and Guo K: BNIP3-mediated mitophagy boosts the

competitive growth of Lenvatinib-resistant cells via energy

metabolism reprogramming in HCC. Cell Death Dis.

15(484)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

67

|

Bassissi F, Jílková Z, Brun S, Courcambeck

J, Tracz J, Kurma K, Roth GS, Khaldi C, Chaimbault C, Quentin B, et

al: Abstract 5124: GNS561 a new quinoline derivative inhibits the

growth of hepatocellular carcinoma in a cirrhotic rat and human PDX

orthotopic mouse models. Cancer Res. 77 (Suppl 13)(5124)2017.

|

|

68

|

Miao Y, Yin Q, Ping L, Sheng H, Chang J,

Li W and Lv S: Pseudolaric acid B triggers ferritinophagy and

ferroptosis via upregulating NCOA4 in lung adenocarcinoma cells. J

Cancer Res Ther. 19:1646–1653. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

69

|

Zhu J, Wang M and Hu D: Development of an

autophagy-related gene prognostic signature in lung adenocarcinoma

and lung squamous cell carcinoma. PeerJ. 8(e8288)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

70

|

Rahdan F, Abedi F, Dianat-Moghadam H, Sani

MZ, Taghizadeh M and Alizadeh E: Autophagy-based therapy for

hepatocellular carcinoma: from standard treatments to combination

therapy, oncolytic virotherapy, and targeted nanomedicines. Clin

Exp Med. 25(13)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

71

|

Zai W, Chen W, Han Y, Wu Z, Fan J, Zhang

X, Luan J, Tang S, Jin X, Fu X, et al: Targeting PARP and autophagy

evoked synergistic lethality in hepatocellular carcinoma.

Carcinogenesis. 41:345–357. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

72

|

Qian M, Wan Z, Liang X, Jing L, Zhang H,

Qin H, Duan W, Chen R, Zhang T, He Q, et al: Targeting autophagy in

HCC treatment: Exploiting the CD147 internalization pathway. Cell

Commun Signal. 22(583)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

73

|

Macleod K: Abstract 4984: BNip3 suppresses

hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) growth by limiting lipogenesis.

Cancer Res. 77 (Suppl 13)(4984)2017.

|

|

74

|

Zai W, Chen W, Liu H and Yuxuan H:

MO1-5-3-Compromised autophagy sensitizes hepatocellular carcinoma

to PARP inhibition. Ann Oncol. 30:vi91–vi2. 2019.

|

|

75

|

Sadagopan N and He AR: Recent progress in

systemic therapy for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Mol

Sci. 25(1259)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

76

|

Byrnes K, Blessinger S, Bailey NT, Scaife

R, Liu G and Khambu B: Therapeutic regulation of autophagy in

hepatic metabolism. Acta Pharm Sin B. 12:33–49. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

77

|

Allaire M, Rautou PE, Codogno P and

Lotersztajn S: Autophagy in liver diseases: Time for translation? J

Hepatol. 70:985–998. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

78

|

Martini G, Ciardiello D, Paragliola F,

Nacca V, Santaniello W, Urraro F, Stanzione M, Niosi M, Dallio M,

Federico A, et al: How immunotherapy has changed the continuum of

care in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancers (Basel).

13(4719)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|