Introduction

Globally, lung cancer is listed as one of the most

common and lethal types of cancer (1,2). In

total, ~85% of lung cancer cases are non-small cell lung carcinoma

(NSCLC) (3), with lung

adenocarcinoma being the most common subtype of NSCLC. Early-stage

lung cancer often presents with minimal or mild clinical symptoms;

therefore, ~75% of patients are already at an advanced stage at

initial diagnosis (4). When

diagnosed, pleural effusion is present in 20% of patients with lung

cancer (5) and the survival of

patients with lung cancer with malignant pleural effusion (MPE) is

5.5 months from diagnosis (6).

Furthermore, most patients with pleural effusion are not eligible

for surgical intervention due to the advanced stage of the

disease.

Mutations in the EGFR gene have been recognized as

key markers for individualized therapy and evaluating prognosis in

advanced lung cancer, given their close association with the

appropriateness of specific treatments, such as targeted therapy

(7). However, for numerous

patients with advanced lung cancer, sufficient tumor tissue for

molecular diagnosis cannot be obtained due to the inherent

invasiveness and sampling limitations of puncture biopsy or

surgical procedures. MPE cell blocks, often containing tumor cells

from patients, are recognized by pathologists as a valuable

resource for genetic testing, offering a unique opportunity to

directly analyze and understand the molecular characteristics of

malignancies (8). Pleural effusion

may be an alternative specimen to tumor tissue, as it can be safely

and repeatedly collected via thoracentesis (9). A previous study showed that the use

of pleural effusion cell blocks combined with immunohistochemistry

and molecular testing markedly improved the accuracy and

specificity of advanced lung cancer diagnosis compared with

standalone pleural effusion cytology (10).

The objective of the present study was to provide

clinical proof to confirm the diagnostic and predictive

significance of pleural effusion cell block technology in

diagnosing lung cancer and guiding decisions for patient-specific

clinical treatments. Immunohistochemical analysis was performed on

pleural effusion cell blocks from patients with advanced lung

cancer for histological classification, and an amplification

refractory mutation system (ARMS) was used to detect the EGFR

target gene mutation status in cell blocks from patients with

confirmed lung adenocarcinoma.

Materials and methods

Patients

The present study encompassed 231 patients with lung

cancer with pleural effusion complications (MPE) who presented at

Weifang No. 2 People's Hospital (Weifang, China) between July 2018

and December 2022. The population comprised of 129 male patients

and 102 female patients, aged 30-91 years old (mean age,

68.61±10.53 years). Samples of pleural effusion were collected from

each patient through the hospital medical system. No patient had

undergone targeted therapy. Data on clinicopathological features

were collected from the Weifang No. 2 People's Hospital health

record system. Patient overall survival (OS) information was

acquired via telephone follow-ups. The monitoring phase commenced

in July 2018 and concluded in February 2022.

Criteria for inclusion were as follows: i) Patients

diagnosed with lung cancer after admission on the basis of clinical

symptoms, bronchoscopy and pathological examination of cell blocks

using hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining and

immunohistochemistry; ii) patients with lung cancer who had not

received targeted therapy prior to pleural effusion collection;

iii) patients with sufficient pleural effusion material for the

preparation of cell blocks and subsequent experimental procedures

(at least 20 tumor cells in one H&E-stained section of the cell

block); and iv) comprehensive clinical data for patients provided

by the medical record system, encompassing the patient's age, sex,

clinical stage and smoking history.

The exclusion criteria were: i) Individuals

suffering from acute respiratory, heart or brain vessel disorders;

and ii) individuals with a background of or simultaneous presence

of other cancerous diseases, such as breast, colon or cervical

cancer.

The Ethics Committee of Weifang No. 2 People's

Hospital approved the present study (approval no. KY2023-015-01)

and all participants provided written informed consent for the use

of their tissues/data for scientific research purposes.

Reagents and instruments

The primary antibodies used in immunohistochemistry

were purchased from Fuzhou Maixin Biotechnology Development Co.,

Ltd. The secondary antibody and colorimetric reagents were obtained

from Roche Diagnostics (Shanghai) Co., Ltd.

A low-speed centrifuge (TDL-40B) was obtained from

Shandong Bio-Medical Technology Co., Ltd. The BenchMark GX

automated staining system was purchased from Roche Diagnostics

(Shanghai) Co., Ltd. The SLAN-96S fully automated medical

polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis system was purchased from

Shanghai Hongshi Medical Technology Co., Ltd.

Preparation of cell blocks

After collection of pleural fluid specimens, the

samples were promptly delivered to the Department of Pathology of

Weifang No. 2 People's Hospital. The sample was maintained at

ambient temperature for a duration of 15-30 min, following which

50-100 ml liquid was collected from the bottom of the container.

Samples underwent centrifugation at 1,000 x g for 5 min at room

temperature, followed by the extraction of the pellet for

cytological smear analysis by H&E staining. Following removal

of the supernatant, a solution of 4% neutral buffered formalin was

introduced to fix the pellet samples for 15 min at room

temperature. Subsequently, samples underwent centrifugation at

1,000 x g for 5 min at room temperature, after which the pellet was

moved to qualitative filter paper (Nanchang Yulu Experimental

Equipment Co., Ltd.) and then routinely dehydrated through a graded

ethanol series for 1-2 h at each concentration to remove water,

followed by clearing with xylene to achieve transparency for a

duration of 1-3 h. The slides were embedded in paraffin and

subsequently stained with H&E, with hematoxylin applied for 5

min and eosin applied for 30 sec, both at room temperature. An

optical microscope was used to observe the results.

Immunohistochemistry

The cell blocks were sectioned into 4-µm slices and

stained using the Roche BenchMark GX fully automated

immunohistochemistry system. Positive (antigen-expressing tissue)

and negative (replacement of primary antibody with negative

reagent) controls were routinely set up. The primary antibodies

used included antibodies against pan-cytokeratin (pCK), CK7, CK5/6,

napsin A, thyroid transcription factor-1 (TTF-1), P40, Wilms tumor

1 (WT-1), synaptophysin, chromogranin A (CgA), homeobox protein

CDX2, villin, CD56, Ki-67, desmin and calretinin (Table SI; Data SI). All cell blocks were

independently evaluated by two pathologists to ascertain whether

the cytomorphology matched the immunophenotyping results and to

assess whether the tumor cell content met the requirements for PCR

testing (a cell block H&E-stained section must contain at least

20 tumor cells). Tumor cells of lung adenocarcinoma exhibit

glandular/acinar patterns, while tumor cells of small cell

carcinoma are tightly arranged in a ‘stacked or regimented’

formation and tumor cells of squamous cell carcinoma are often

dispersed as single cells or in small clusters.

Genomic DNA extraction from

paraffin-embedded samples

After the tumor cell content was evaluated by

immunohistochemistry (number of tumor cells and percentage of tumor

cells relative to the total tissue area in the H&E-stained

section), 4-12 cell block sections were cut to a 5-µm thickness

using a disposable microtome blade and transferred into clean

1.5-ml centrifuge tubes. DNA extraction was performed using a

nucleic acid extraction kit (FFPE DNA; cat. no. 8.02.0017; Amoy

Diagnostics Co., Ltd.) following the manufacturer's instructions.

DNA purity and concentration were quantified using an Eppendorf UV

spectrophotometer (Eppendorf SE).

Detection of EGFR gene mutations

EGFR gene mutation status was evaluated by ADx-ARMS

using the human EGFR gene mutation detection kit (cat. no.

8.01.0131; Amoy Diagnostics Co., Ltd.), including primers and

fluorophore, following the manufacturer's guidelines. Using this

kit, the ARMS technique was used to identify 21 prevalent forms of

mutations in EGFR exons 18, 19, 20 and 21. The thermocycling

conditions used were as follows: 1 cycle at 95˚C for 5 min; 15

cycles at 95˚C for 25 sec, 64˚C for 20 sec and 72˚C for 20 sec; and

31 cycles at 93˚C for 25 sec, 60˚C for 35 sec and 72˚C for 20 sec.

Upon completion of the reaction, the SLAN-96S fluorescence

quantitative PCR instrument provided the amplification curve, and

the mutations were determined following the interpretation

principles outlined in the kit instructions. Each experiment

included a positive control from the kit and nuclease-free purified

water as a negative control.

Patient treatment

Patients with single EGFR mutations received EGFR

tyrosine kinase inhibitors as first-line treatment, as detailed in

Table I. Patients without EGFR

gene mutations were treated with chemotherapy, specifically

cisplatin (a platinum-based drug) at 75 mg/m² combined with

pemetrexed (an antimetabolite agent) at 500 mg/m² for 4-6 cycles,

followed by pemetrexed maintenance at 500 mg/m². Treatment

continued until disease progression or the occurrence of

intolerable adverse reactions. Based on the completeness of

follow-up data, prognostic analysis was performed only on 36 cases

with EGFR gene mutations and 65 cases without EGFR gene

mutations.

| Table ITKI treatments (patients received only

one oral medication listed). |

Table I

TKI treatments (patients received only

one oral medication listed).

| EGFR mutation

type | Specific TKI | Generation | Dosage | Treatment

duration |

|---|

| L858R 19-del | Gefitinib | 1st Generation | 250 mg once

daily | Until disease

progression or unacceptable toxicity |

| | Erlotinib | 1st Generation | 150 mg once

daily | |

| | Icotinib | 1st Generation | 125 mg three times

daily | |

| | Afatinib | 2nd Generation | 40 mg once daily | |

| | Osimertinib | 3rd Generation | 80 mg once daily | |

| G719X,L861Q | Afatinib | 2nd Generation | 40 mg once daily | |

Statistical and prognostic

analyses

Statistical evaluation was performed using SPSS 25.0

software (IBM Corp.). The χ2 test was employed to

explore the associations between mutations in the EGFR gene and

clinicopathological features. Data are presented as n (%). The

analysis of prognosis was performed with GraphPad Prism 9.4.0

software (Dotmatics). Survival curves were generated using

Kaplan-Meier analysis. Statistical evaluation of the survival rates

for patients with EGFR mutations and those with wild-type EGFR was

performed using the log-rank test. P<0.05 was considered to

indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Histological types of lung tumors in

the study group

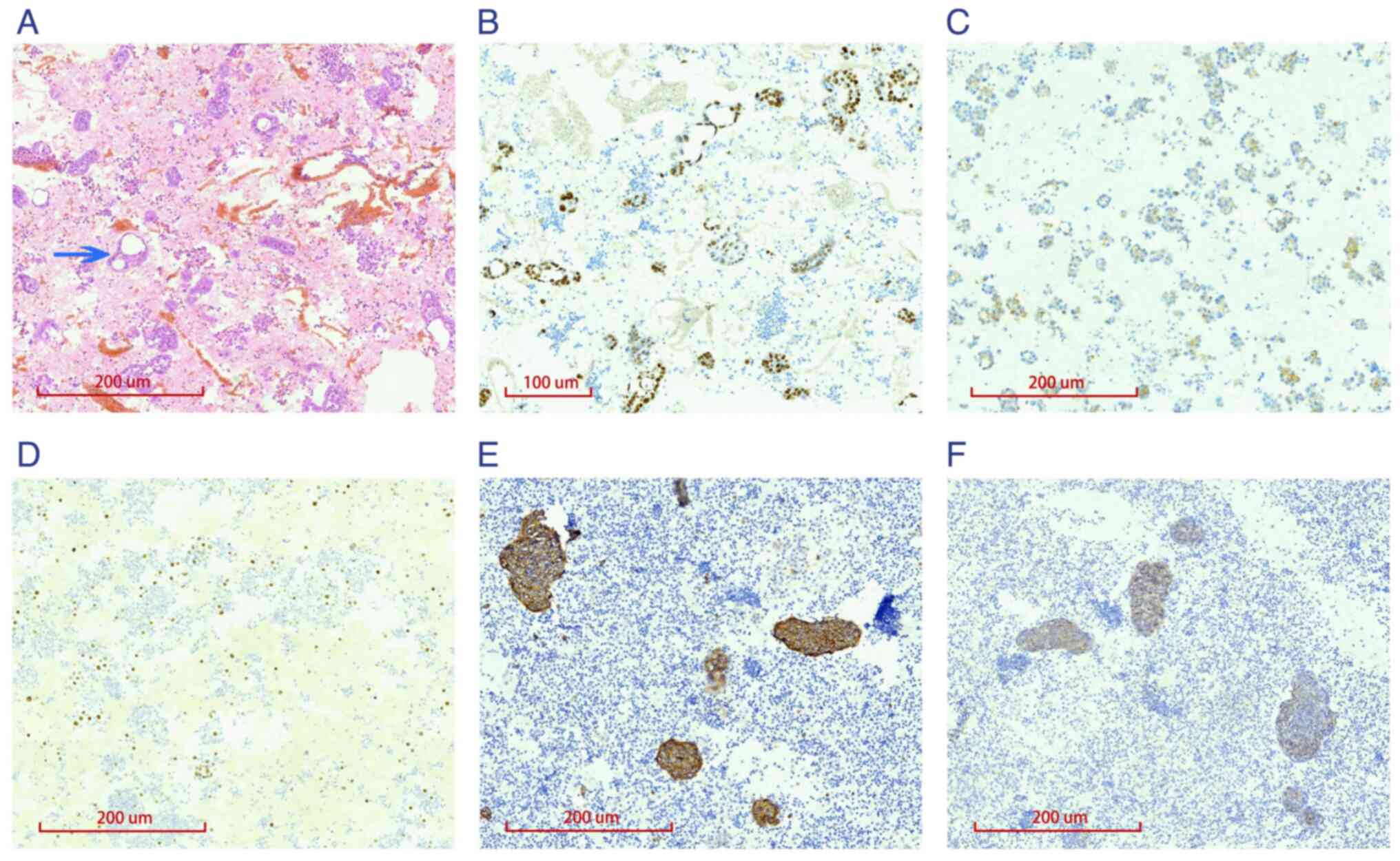

H&E analysis and immunohistochemistry with

different antibodies was conducted on the cell blocks from pleural

effusions of 231 patients with advanced lung cancer for

histological classification. TTF-1, P40, CDX-2, Ki-67 and WT-1

exhibited nuclear staining, pCK, CK7, CK5/6, napsin A, villin,

desmin, CgA and synaptophysin showed cytoplasmic staining, CD56

displayed membrane staining, and calretinin showed either nuclear

or cytoplasmic staining. Among the 231 cell blocks analyzed, 222

showed cancer cells arranged in glandular and rosette-like patterns

(Fig. 1A), with positive staining

for the lung adenocarcinoma markers TTF-1, napsin A and CK7

(Figs. 1B and C and S1A). Two cases were positive for the

squamous cell carcinoma markers P40 and CK5/6 (Figs. 1D and S2D). Seven cases showed positive

staining for the neuroendocrine markers synaptophysin, CD56 and CgA

(Figs. 1E and F and S2B), along with focal perinuclear

dot-like expression of cytokeratin (Fig. S2A), supporting a diagnosis of

small cell carcinoma. Additionally, the Ki-67 proliferation marker

was highly expressed in the small cell carcinoma cases (Fig. S2C). The remaining proteins

(calretinin, WT-1, villin, CDX2 and desmin) showed negative

staining in the tumor cells (Fig.

S1B-F).

EGFR gene mutations in the study

group

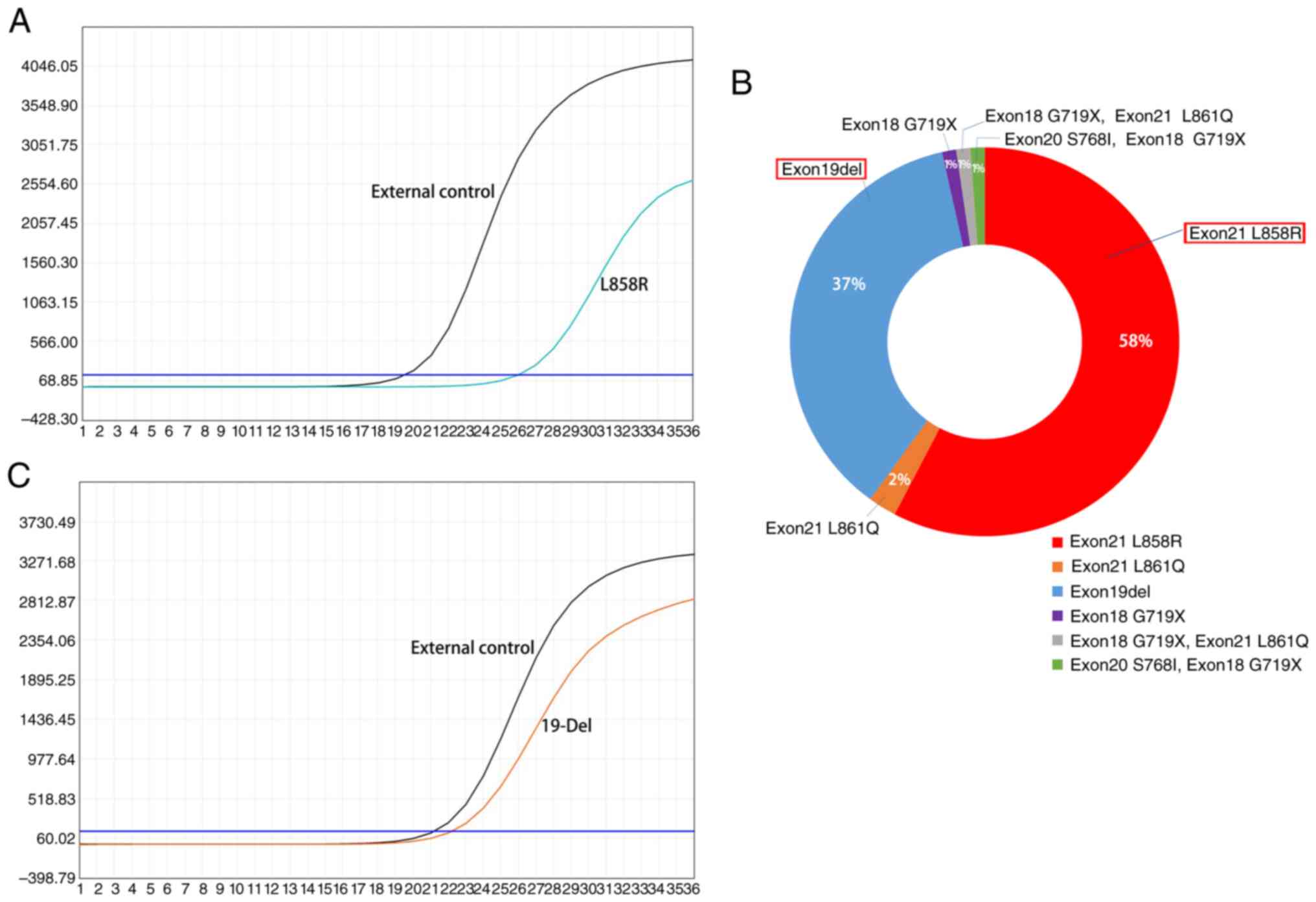

Among the 231 pleural effusion cell blocks from

patients with lung cancer, 161 underwent EGFR gene mutation

testing, all of which were obtained from patients with lung

adenocarcinoma. The remaining 70 patients did not receive the

testing for various reasons, such as financial constraints. Among

the 161 cases, 85 were positive for EGFR gene mutations (positive

rate, 52.8%). The detected genetic alterations encompassed 49

instances of the L858R mutation in exon 21, 31 instances of

deletions in exon 19, 2 instances of the L861Q mutation in exon 21

and a single case of the G719X mutation in exon 18. Another 2

patients showed complex mutations; 1 patient had the G719X mutation

in exon 18 alongside the L861Q mutation in exon 21, whereas the

other patient had the S768I mutation in exon 20 coupled with the

G719X mutation in exon 18 (Figs. 2

and S3).

Association between EGFR gene

mutations and clinicopathological characteristics in patients with

lung adenocarcinoma

Subsequently, the present study focused on the link

between the clinicopathological traits of 161 patients with lung

adenocarcinoma and EGFR mutations detected through pleural effusion

cell block analysis. There was a significantly greater occurrence

of EGFR gene mutations in female patients (32.3%) than in male

patients (20.5%) (P=0.001) (Table

II). Whereas EGFR gene mutations tended to show differences in

patients stratified by age and smoking history, the results did not

reach statistical significance (Table

II).

| Table IIAssociation of EGFR gene mutations

with patient clinical parameters. |

Table II

Association of EGFR gene mutations

with patient clinical parameters.

| | EGFR gene

mutations | |

|---|

| Clinical

parameter | Patient number | Mutation | Wild-type | Mutation rate, % |

χ2-value | P-value |

|---|

| Sex | | | | | 11.682 | 0.001 |

|

Male | 83 | 33 | 50 | 20.50 | | |

|

Female | 78 | 52 | 26 | 32.30 | | |

| Age, years | | | | | 0.328 | 0.608 |

|

<65 | 48 | 27 | 21 | 16.77 | | |

|

≥65 | 113 | 58 | 55 | 36.03 | | |

| Smoking

history | | | | | 3.520 | 0.086 |

|

Smoker | 66 | 29 | 37 | 18.02 | | |

|

Non-smoker | 95 | 56 | 39 | 34.78 | | |

Prognostic comparison

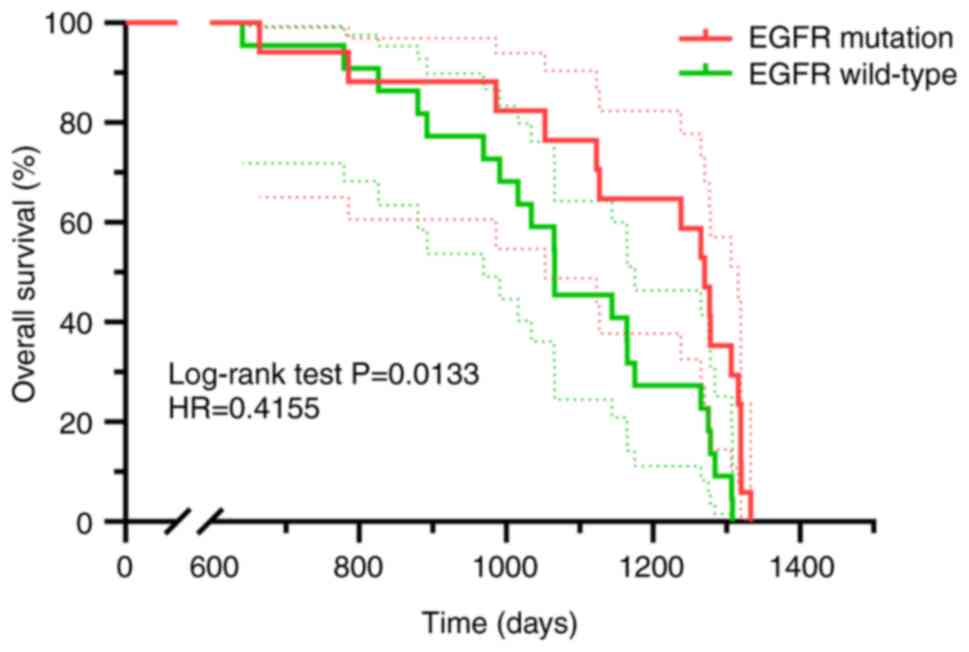

An observational analysis was performed on 36

patients exhibiting single EGFR mutations determined from pleural

effusion cell blocks and receiving EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor

(TKI) as their primary therapeutic intervention and 65 patients

without EGFR gene mutations determined from pleural effusion cell

blocks and treated with chemotherapy as first-line treatment. The

monitoring phase concluded in February 2022. Patients carrying EGFR

mutations exhibited a significantly extended OS rate compared with

patients with wild-type EGFR (hazard ratio=0.4155, P=0.0133;

Fig. 3).

Discussion

Over the last 20 years, studies have shown that

focusing on specific driver genes in therapy can extend the

duration of progression-free survival and OS in patients with lung

cancer. A study by Ramalingam et al (11) demonstrated that patients with EGFR

mutations (exon 19 deletion or L858R) who received osimertinib

treatment showed significantly extended OS. Alterations in the EGFR

gene frequently emerge as the primary driver of genetic changes in

lung cancer (12). Multiple

studies (13-15)

have demonstrated the superior efficacy and reduced toxicity of

targeted drugs compared with traditional chemotherapy, indicating

that targeted drug treatments provide sustained clinical benefits

and markedly improve prognostic outcomes for patients with lung

cancer. For patients with advanced NSCLC and sensitizing EGFR

mutations, EGFR TKIs serve as the primary treatment option

(16); however, sufficient tumor

tissue for genetic testing is not available for all patients with

advanced NSCLC.

The present study demonstrates that detecting

genetic mutations through MPE cell blocks is of value for

predicting patient response to targeted therapy. The ARMS-PCR

technique was employed to detect genetic mutations that drive tumor

progression in MPE cell blocks from patients with NSCLC lacking

tumor tissue samples. The findings showed a 52.8% detection rate of

EGFR mutations in MPE specimens, a rate similar to that observed

with tumor tissue samples (8,17).

The detected mutations included the L858R mutation in exon 21 and

the deletion mutation in exon 19 of EGFR, detected in 49 and 31

patients, respectively, constituting 95% of all detected EGFR

mutations. These proportions align with previous results in studies

of tumor tissues with reported rates of 85-90% (18-20).

The results of the present study also revealed the presence of

three less common mutation types (L861Q, G719X and S768I), with no

other rare EGFR mutations identified. These findings indicated that

the frequency of EGFR oncogenic driver gene mutations identified in

MPE may mirror that found in tumor tissues.

While a previous study has verified the diagnostic

precision of MPE in detecting oncogenic driver genes compared with

tumor tissue (21), to the best of

our knowledge there is almost no research on the efficacy of TKI

targeted therapy administered solely on the basis of the detection

of mutations through MPE analysis. The current study revealed that

patients with single EGFR mutations identified via MPE analysis and

treated initially with EGFR-TKIs experienced a significantly longer

OS rate compared with patients without EGFR mutations who received

chemotherapy as first-line treatment. This aligns with a previous

study on patients with EGFR sensitizing mutations detected on tumor

tissue who were administered EGFR-TKIs as an initial treatment

(11). Additionally, the findings

of the present study demonstrated variations in EGFR mutation rates

in MPE based on sex, with a notably higher incidence in female

patients than in male patients, consistent with the outcomes of

previous studies based on tumor tissue analysis, where the

detection rate of EGFR gene mutation was 52.8% in women and 31.6%

in men (22-24).

The present study has certain limitations. First,

only ARMS-PCR was used for detection of EGFR gene mutations, and

this technique has limitations in terms of detection sensitivity

and coverage (25,26), particularly in identifying

low-frequency mutations and rare mutations related to EGFR-TKI

resistance. This limitation affects the completeness of the

mutation spectrum in MPE samples. Upcoming initiatives ought to

focus on employing diverse mutation detection platforms, and

amalgamating advanced detection methods, such as next-generation

sequencing and droplet digital PCR, for a more detailed gene

mutation profile. Secondly, since this study only collected data

from malignant pleural effusion cell blocks of patients with lung

cancer, and the data analysis was based on comparisons with other

literature rather than a direct comparison with the patients' own

tumor tissue specimens, there are inherent differences in the

research subjects and tumor heterogeneity, which impose relative

limitations on the results. In future research, the study design

will be refined further by conducting advance planning and patient

recruitment to ensure standardized and consistent data

collection.

In conclusion, the findings of the present study

indicated that the OS rate of EGFR-TKI-treated patients, with EGFR

gene mutations identified solely via MPE cell block tests, may be

comparable with that of patients with similar mutations identified

on tumor tissues in previous studies. Furthermore, the frequency of

EGFR gene alterations identified in MPE paralleled that reported in

cancerous tissues in previous studies. Therefore, when sufficient

tumor tissue cannot be obtained, MPE is recommended as an

alternative specimen for the detection of EGFR mutations.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary methods

Immunohistochemical staining of

pleural effusion cell blocks from patients with lung cancer. (A)

Immunohistochemical staining showing positive cytokeratin 7

expression in adenocarcinoma. Immunohistochemical staining showing

(B) negative calretinin expression, (C) negative WT-1 expression,

(D) negative villin expression, (E) negative homeobox protein CDX2

expression and (F) negative desmin expression in tumor cells.

Immunohistochemical staining of

further markers in pleural effusion cell blocks from patients with

lung cancer. (A) Immunohistochemical staining showing perinuclear

dot-like positivity for pan-cytokeratin in small cell carcinoma.

(B) Immunohistochemical staining showing focal weak positivity (red

arrows) for chromogranin A in small cell carcinoma. (C)

Immunohistochemical staining showing a high Ki-67 proliferation

index in small cell carcinoma. (D) Immunohistochemical staining

showing positive cytokeratin 5/6 expression in squamous cell

carcinoma.

Representative detection images of the

other four types of EGFR gene mutations. (A) Exon 21 L861Q

mutation. (B) Exon 18 G719X mutation. (C) Compound mutation of exon

18 G719X and exon 21 L861Q. (D) Compound mutation of exon 20 S768I

and exon 18 G719X.

Ready-to-use primary antibodies

incubated at 37˚C for 32 min.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: The present study was supported by the Health

Commission of Weifang, China (grant nos. WFWSJK-2023-122 and

2024-200) and the Medical and Health Science and Technology Project

of Shandong, China (grant no. 202401040090).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

SZ, YuL and XC designed the present study. SZ, YuL

and TW conducted the experiments. ZC and YiL performed statistical

analysis, and SZ wrote the manuscript. XC and YiL conducted the

systematic literature search and supervised the writing of the

manuscript. SZ, YuL and XC confirm the authenticity of all the raw

data. All authors have read and approved the final version of the

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was conducted in accordance with

ethical standards and was approved by the Ethics Committee of

Weifang No. 2 People's Hospital (approval no. KY2023-015-01;

Weifang, China). Written informed consent was obtained from all

patients for the use of their data and specimens in scientific

research.

Patient consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained for

publication of the patient data and images.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Huang S, Yang J, Shen N, Xu Q and Zhao Q:

Artificial intelligence in lung cancer diagnosis and prognosis:

Current application and future perspective. Semin Cancer Biol.

89:30–37. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Lee E and Kazerooni EA: Lung cancer

screening. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 43:839–850. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J,

Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I and Jemal A: Global cancer statistics

2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for

36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 74:229–263.

2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Cho JH: Immunotherapy for non-small-cell

lung cancer: Current status and future obstacles. Immune Netw.

17:378–391. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Chen Y, Mathy NW and Lu H: The role of

VEGF in the diagnosis and treatment of malignant pleural effusion

in patients with nonsmall cell lung cancer (review). Mol Med Rep.

17:8019–8030. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Ferreiro L, Suárez-Antelo J,

Álvarez-Dobaño JM, Toubes ME, Riveiro V and Valdés L: Malignant

pleural effusion: Diagnosis and management. Can Respir J.

2020(2950751)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Russo A, Lopes AR, McCusker MG, Garrigues

SG, Ricciardi GR, Arensmeyer KE, Scilla KA, Mehra R and Rolfo C:

New targets in lung cancer (excluding EGFR, ALK, ROS1). Curr Oncol

Rep. 22(48)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Mao L, Zhao W, Li X, Zhang S, Zhou C, Zhou

D, Ou X, Xu Y, Tang Y, Ou X, et al: Mutation spectrum of

EGFR from 21,324 Chinese patients with non-small cell lung

cancer (NSCLC) successfully tested by multiple methods in a

CAP-accredited laboratory. Pathol Oncol Res.

27(602726)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Mohammed A, Hochfeld U, Hong S, Hosseini

DK, Kim K and Omidvari K: Thoracentesis techniques: A literature

review. Medicine (Baltimore). 103(e36850)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Porcel JM: Diagnosis and characterization

of malignant effusions through pleural fluid cytological

examination. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 25:362–368. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Ramalingam SS, Vansteenkiste J, Planchard

D, Cho BC, Gray JE, Ohe Y, Zhou C, Reungwetwattana T, Cheng Y,

Chewaskulyong B, et al: Overall survival with osimertinib in

untreated, EGFR-mutated advanced NSCLC. N Engl J Med.

382:41–50. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Su C: Emerging insights to lung cancer

drug resistance. Cancer Drug Resist. 5:534–540. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Wu YL, Saijo N, Thongprasert S, Yang JC,

Han B, Margono B, Chewaskulyong B, Sunpaweravong P, Ohe Y, Ichinose

Y, et al: Efficacy according to blind independent central review:

Post-hoc analyses from the phase III, randomized, multicenter,

IPASS study of first-line gefitinib versus carboplatin/paclitaxel

in Asian patients with EGFR mutation-positive advanced NSCLC. Lung

Cancer. 104:119–125. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Shi Y, Zhang L, Liu X, Zhou C, Zhang L,

Zhang S, Wang D, Li Q, Qin S, Hu C, et al: Icotinib versus

gefitinib in previously treated advanced non-small-cell lung cancer

(ICOGEN): A randomised, double-blind phase 3 non-inferiority trial.

Lancet Oncol. 14:953–961. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Hu X, Zhang L, Shi Y, Zhou C, Liu X, Wang

D, Song Y, Li Q, Feng J, Qin S, et al: The efficacy and safety of

Icotinib in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer

previously treated with chemotherapy: A single-arm, multi-center,

prospective study. PLoS One. 10(e0142500)2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Ettinger DS, Wood DE, Aisner DL, Akerley

W, Bauman JR, Bharat A, Bruno DS, Chang JY, Chirieac LR, DeCamp M,

et al: NCCN guidelines® insights: Non-small cell lung

cancer, version 2.2023. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 21:340–350.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Wang JL, Fu YD, Gao YH, Li XP, Xiong Q, Li

R, Hou B, Huang RS, Wang JF, Zhang JK, et al: Unique

characteristics of G719X and S768I compound double mutations of

epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) gene in lung cancer of

coal-producing areas of East Yunnan in Southwestern China. Genes

Environ. 44(17)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Batra U, Biswas B, Prabhash K and Krishna

MV: Differential clinicopathological features, treatments and

outcomes in patients with exon 19 deletion and exon 21 L858R EGFR

mutation-positive adenocarcinoma non-small-cell lung cancer. BMJ

Open Respir Res. 10(e001492)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Kutsuzawa N, Takahashi F, Tomomatsu K,

Obayashi S, Takeuchi T, Takihara T, Hayama N, Oguma T, Aoki T and

Asano K: Successful treatment of a patient with lung adenocarcinoma

harboring compound EGFR gene mutations, G719X and S768I, with

afatinib. Tokai J Exp Clin Med. 45:113–116. 2020.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Suda K, Mitsudomi T, Shintani Y, Okami J,

Ito H, Ohtsuka T, Toyooka S, Mori T, Watanabe SI, Asamura H, et al:

Clinical impacts of EGFR mutation status: Analysis of 5780

surgically resected lung cancer cases. Ann Thorac Surg.

111:269–276. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Yao Y, Peng M, Shen Q, Hu Q, Gong H, Li Q,

Zheng Z, Xu B, Li Y and Dong Y: Detecting EGFR mutations and

ALK/ROS1 rearrangements in non-small cell lung cancer using

malignant pleural effusion samples. Thorac Cancer. 10:193–202.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Wang H, Zhang W, Wang K and Li X:

Correlation between EML4-ALK, EGFR and clinicopathological features

based on IASLC/ATS/ERS classification of lung adenocarcinoma.

Medicine (Baltimore). 97(e11116)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Wang T, Zhang Y, Liu B, Hu M, Zhou N and

Zhi X: Associations between epidermal growth factor receptor

mutations and histological subtypes of lung adenocarcinoma

according to the IASLC/ATS/ERS classification in Chinese patients.

Thorac Cancer. 8:600–605. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Li D, Ding L, Ran W, Huang Y, Li G, Wang

C, Xiao Y, Wang X, Lin D and Xing X: Status of 10 targeted genes of

non-small cell lung cancer in eastern China: A study of 884

patients based on NGS in a single institution. Thorac Cancer.

11:2580–2589. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

He C, Wei C, Wen J, Chen S, Chen L, Wu Y,

Shen Y, Bai H, Zhang Y, Chen X and Li X: Comprehensive analysis of

NGS and ARMS-PCR for detecting EGFR mutations based on 4467 cases

of NSCLC patients. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 148:321–330.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Xu T, Kang X, You X, Dai L, Tian D, Yan W,

Yang Y, Xiong H, Liang Z, Zhao GQ, et al: Cross-platform comparison

of four leading technologies for detecting EGFR mutations in

circulating tumor DNA from non-small cell lung carcinoma patient

plasma. Theranostics. 7:1437–1446. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|