Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a prevalent degenerative

joint disorder that affects the quality of life of >344 million

individuals worldwide, especially postmenopausal women. This places

a substantial burden on healthcare systems as well as a

socioeconomic stress (1-3).

The pathogenesis of OA involves multifactorial factors, including

mechanical stress, inflammation, hormonal imbalance and metabolic

dysregulation. However, a complete understanding of its etiology

and pathological progression is yet to be elucidated. This has led

to a lack of effective clinical interventions among patients with

early-stage OA (4,5).

Among the multifactorial factors involved, estrogen

serves a crucial role in female patients (6). A number of studies demonstrate that

estrogen, particularly estradiol (E2), is a protective factor

against OA as it reduces the release of inflammatory mediators

(such as IL-1β, TNF-α and IL-6) and promotes cartilage matrix

synthesis, which can mitigate the onset and progression of OA

(3,7-9).

Clinical evidence also indicates that estrogen replacement therapy

can delay cartilage degeneration and reduce the risk of OA among

menopausal women, which highlights its anti-inflammatory and

cartilage-protective properties (10,11).

However, estrogen-dependent uterine fibroids (UFs)

are the most common pelvic tumors in women of childbearing age,

affecting >70% of the global population of women (9,12,13).

UFs cause symptoms including excessive menstrual bleeding, anemia,

pelvic pressure and pain. In addition, UFs elevate the risk of

endometrial cancer and compromises the quality of life of women

(9,14-16).

As typical estrogen-dependent tumors, estrogen binds to estrogen

receptors (ERα/ERβ) on myometrial cells, activating proliferation

pathways in fibroid stem cells, such as the β-catenin pathway. This

promotes the proliferation of smooth muscle cells and inhibits

apoptosis (17). Furthermore,

estrogen also enhances the expression of various cytokines, such as

TGF-β3 and activin A, which leads to an increase in the deposition

of extracellular matrix (ECM) in the fibroid. This serves a

critical role in the proliferation and enlargement of fibroids

(17,18). These dual, yet opposing, roles of

estrogen in OA and UFs indicate the complexity of the hormone.

Inflammation is a common risk factor for UFs and OA.

In OA, inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1β, induce cartilage

matrix degradation through the upregulation of matrix

metalloproteinases and the suppression of cartilage-specific

proteins, such as collagen II, aggrecan and cartilage oligomeric

matrix protein (19). Furthermore,

TGF-β, which is normally protective, is often dysregulated,

exacerbating cartilage degradation under inflammatory conditions

(20). Additionally, UF tissues

have increased levels of inflammatory cytokines (such as MMPs, TNFs

and ILs) that promote chronic inflammation and the excessive

deposition of ECM (21).

Therefore, inflammation-driven ECM remodeling represents a shared,

yet divergent, pathway in OA and UF pathogenesis.

The complex association between OA and UF is yet to

be fully elucidated. A number of studies suggest a potential

inverse association between UFs and the risk of OA progression

(22-24).

However, a cross-sectional study by Kovari et al (25) reports a higher incidence of UFs in

individuals with advanced OA. This raises the possibility that OA

may influence the development of UFs through shared hormonal or

inflammatory pathways. For instance, both conditions have been

linked to hormonal imbalances, such as increased estrogen activity,

which can influence the growth and inflammation of tissues.

Inflammation-related pathways, including those involving cytokines

such as IL-1β, TNF-α and TGF-β, are commonly seen in both OA and

UF. These cytokines contribute to cartilage degradation in OA and

to the proliferation of smooth muscle cells in uterine fibroids.

Additionally, the activation of angiogenic factors, such as VEGF,

in both conditions may further promote tissue growth and fibrosis.

However, an investigation by Yan et al (26) demonstrates that there is no causal

link between the concentration of E2 in serum from female patients

and the risk of developing OA. The apparent contradictions in the

evidence may be attributed to the vulnerability of conventional

epidemiological approaches to confounders and reverse causality,

rendering the causal link between UF and OA ambiguous (27). However, conducting extensive

randomized controlled trials to investigate the potential genetic

association between UF and OA is impractical and unethical

(28).

Therefore, Mendelian Randomization (MR) was used in

the present study to reduce the biases introduced by confounding

factors and reverse causation (29). The association between the selected

exposures inferred from genetic polymorphisms and their effects

were investigated in the present MR analysis. The unaltered

characteristics of the genetic polymorphisms after conception

suggested that their use as instrumental variables (IVs)

strengthened the validity of the conclusions in the present study

(30). Additionally, the

widespread availability of genetic information in public databases

facilitated the strategy used in the present study (29).

Materials and methods

Study summary

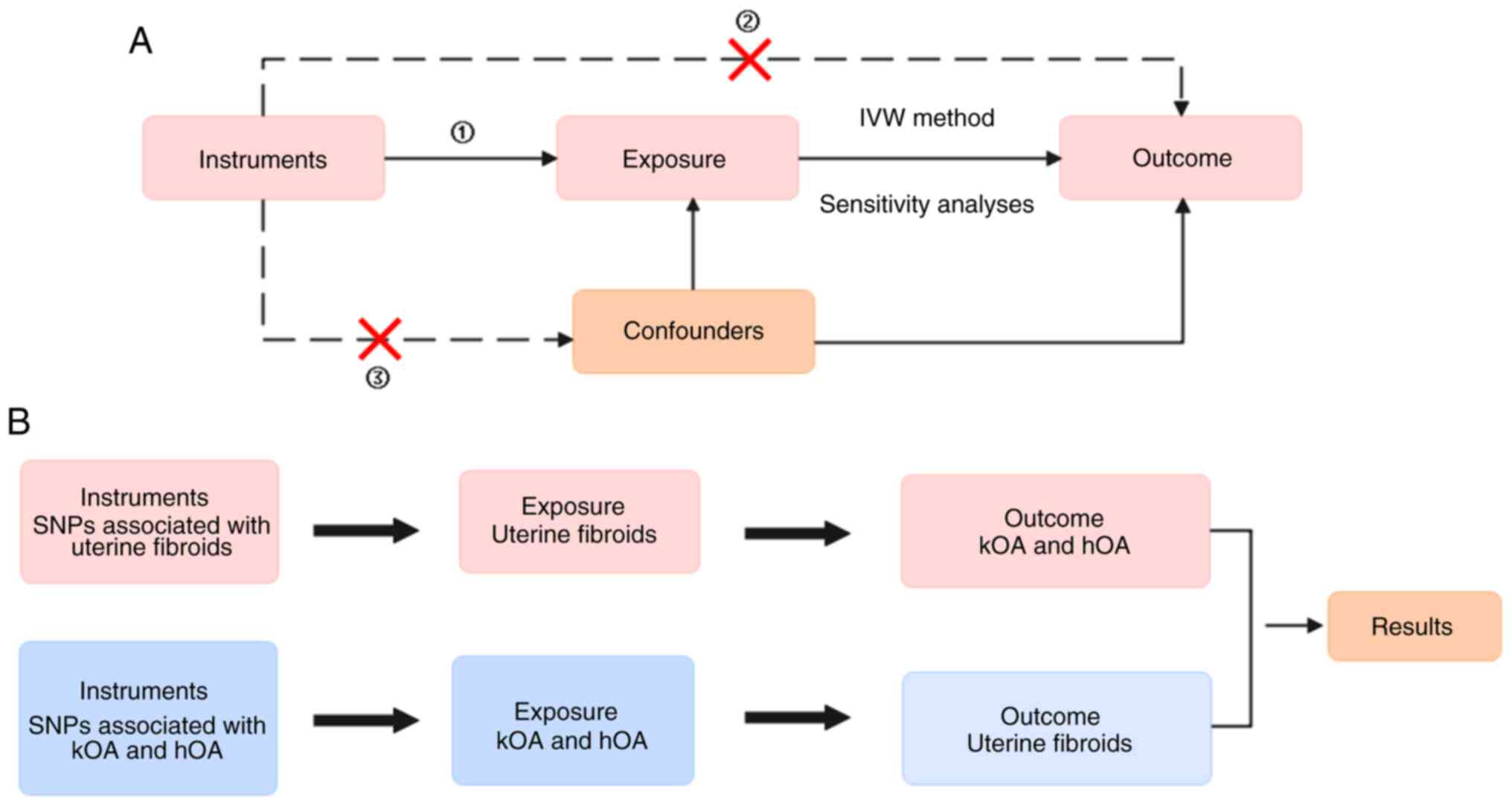

Fig. 1 presents the

design used in the present study of the bidirectional MR

analysis.

Data source and selection of

single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs)

Publicly available data on hip OA (hOA) and knee OA

(kOA) were acquired from a genome-wide study that included

>400,000 European patients (31). The genome-wide association study

(GWAS) database of UF (https://opengwas.io/datasets/ebi-a-GCST90018934) was

obtained from an independent GWAS that included 258,718 European

individuals (32). The detailed

sample characteristics are presented in Table SI.

To satisfy the MR study criteria (33,34),

SNPs with strong associations with UF were selected from the GWAS

database (P<5x10-8). Linkage disequilibrium (LD)

analysis was conducted on these nucleotide polymorphisms to cluster

SNPs (r2 <0.001), and the genetic variants for pairs

in LD were pruned. To minimize bias from sample overlap,

instruments (such as those with an F-statistic >10 for the

instrument-exposure association) were used. Additionally, SNPs were

annotated using the SNiPA SNP annotator online platform (https://snipa.helmholtz-muenchen.de/snipa3/) to find

available proxies for unmatchable SNPs in the GWAS database. The

Phenoscanner database (http://www.phenoscanner.medschl.cam.ac.uk/) was used

to identify SNPs associated with exposure and links to confounding

factors were investigated (P<1x10-5). Table SII was produced by systematically

selecting SNPs from the GWAS database based on the aforementioned

criteria. The selected SNPs were then summarized in Table SII, where their chromosomal

positions, associated genes, effect alleles, non-effect alleles,

effect allele frequencies, β values, P-value, F values and

confounders are shown. These tables directly correspond to the

instrumental variables selected for the bidirectional MR analysis,

which aimed to evaluate causal relationships between UF and OA.

Finally, the filtered SNPs were used as IVs for MR analysis. The

F-statistic was calculated as: F=R2 x (sample

size-2)/(1-R2), where R² is the explained variance in

the exposure by each IV (35,36).

MR analysis

MR analyses were conducted using the version 4.3.1

of TwoSampleMR package (MRC Biostatistics Unit; https://github.com/MRCIEU/TwoSampleMR)

(36), including inverse variance

weighted (IVW), simple median, MR-Egger, weighted mode and weighted

median. If the P-value of the Egger intercept was >0.05, no

potential pleiotropic effects were suggested (37). The MR-pleiotropy residual sum and

outlier method was used to assess the presence of horizontal

pleiotropic outliers. Subsequently, the degree of heterogeneity was

quantified using Cochran's Q statistic (38). ‘Leave-one-out’ analysis, the

sequential exclusion of each SNP, was used to support the

sensitivity and reliability of the outcomes (29). As the results were binary

variables, the β effect estimates were converted to odds ratios

(OR), which were interpreted as the odds of an outcome per unit

increase in exposure (29). The

P-values were adjusted using the Benjamini-Hochberg method

(39).

Cell culture conditions

For the chondrocytes isolated from rats (cat. no.

CP-R087; Procell Life Science & Technology Co., Ltd.), the

culture medium used was rat Articular Chondrocyte Complete Medium

(cat. no. CM-R092; Procell Life Science & Technology Co.,

Ltd.), which primarily contains DMEM/F12, 10% fetal bovine serum

(FBS), 1% penicillin-streptomycin (P-S) solution (cat. no. C0222;

Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology), transferrin and selenium. For

the ELT3 cells (cat. no. 4616; BioVector NTCC Inc.), the complete

culture medium mainly contained DMEM/F12 (cat. no. PM150312;

Procell Life Science & Technology Co., Ltd.), 10% FBS (cat. no.

164250; Procell Life Science & Technology Co., Ltd.), 1% P-S

solution (cat. no. C0222; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology),

ferrous sulfate and sodium selenite. All the cells were incubated

at 37˚C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5%

CO2.

Cell viability analysis

Using the Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) assay (cat.

no. C0037; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) and a Calcein

AM/propidium iodide (PI) kit (cat. no. CA1630; Beijing Solarbio

Science & Technology Co., Ltd.), the viability of chondrocytes

was evaluated. Chondrocytes were seeded in 6-well plates at a

density of 1-1.5x104 cells/well and pretreated with 10

ng/ml IL-1β for 2 h at 37˚C (OA group). Afterward, they were

incubated at 37˚C for 24 h either alone or with ELT3 cells

(0.4-0.8x104 cells/well) in the OA + UF cell (UFC) group

using a 6-well Transwell co-culture system with a 0.4-µm pore size

(cat. no. 3460; Corning, Inc.). Subsequently, 10 µl of CCK-8

reagent was added to each well, followed by a 2 h incubation at

37˚C. The absorbance at 450 nm was recorded using a Rayto RT-6100

microplate reader.

For live/dead staining, chondrocytes were cultured

under the aforementioned conditions and then treated with Calcein

AM and a PI kit, according to the manufacturer's protocol. Live

cells were stained green with Calcein AM for 20 min at room

temperature and protected from light, while dead cells were stained

red with PI for 5 min under the same conditions. Stained cells were

visualized under a fluorescence microscope and quantified using

Image-Pro (version 6.0; Media Cybernetics, Inc.). All experiments

were performed in triplicate. Data are presented as the mean ±

standard deviation (SD). To avoid phenotypic loss, only passages

1-3 of primary cells were used.

Reverse transcription-quantitative

polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was isolated from the chondrocytes using

the RNA Easy Fast Tissue/Cell kit (Tiangen Biotech Co., Ltd.). The

extracted RNA was reverse-transcribed into cDNA using the HiScript

III RT SuperMix for qPCR (+gDNA wiper) kit (cat. no. R323-01;

Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd.) following the manufacturer's protocol..

The cDNA served as a template for qPCR analysis using TB Green

PreMix Ex Taq (cat. no. RR420A; Takara Bio, Inc.), with the

following thermocycling conditions: 95˚C for 30 sec, followed by 40

cycles of 95˚C for 5 sec and 60˚C for 30 sec. Gene expression

levels were determined by calculating the cycle threshold values,

normalized to the internal control GAPDH, and analyzed using the

2-ΔΔCq method (40).

The primer sequences used for the target genes are listed in

Table I.

| Table IPrimer sequences used in reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR. |

Table I

Primer sequences used in reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR.

| Target genes | Forward primer

sequence (5'-3') | Reverse primer

sequence (5'-3') |

|---|

| Collagen II |

GAGTGGAAGAGCGGAGACTACTG |

GTCTCCATGTTGCAGAAGACTTTCA |

| Aggrecan |

CTAGCTGCTTAGCAGGGATAACG |

GATGACCCGCAGAGTCACAAAG |

| GAPDH |

GAAGGTCGGTGTGAACGGATTTG |

CATGTAGACCATGTAGTTGAGGTCA |

Statistical analysis

Experimental data are presented as the mean ± SD and

were visualized using GraphPad Prism (version 6.02; Dotmatics).

Statistical comparisons between groups were carried out using the

unpaired Student's t-test. All experiments were conducted in

triplicate. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically

significant difference.

Results

Genetic associations between UFs and

hOA

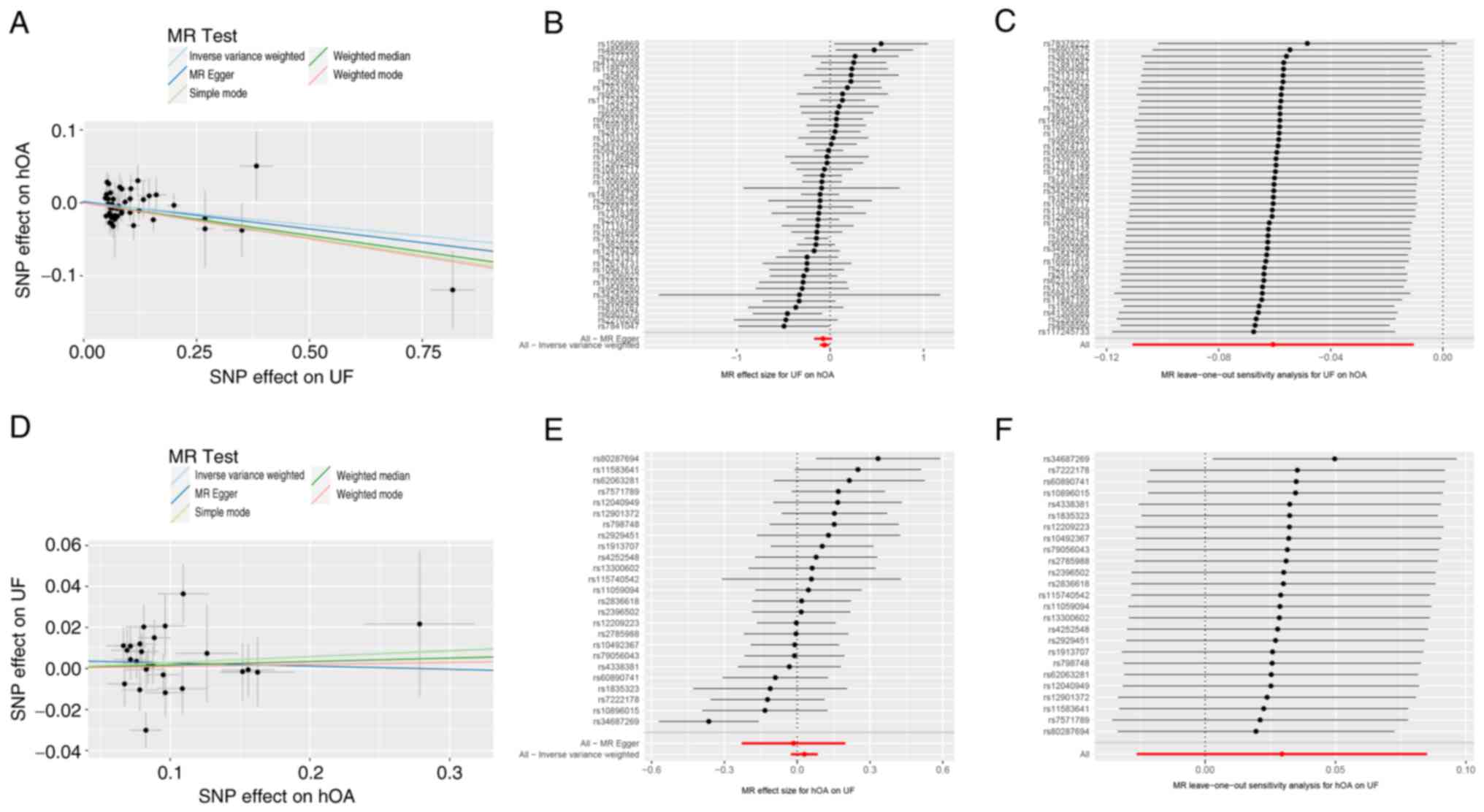

In total, 49 SNPs were initially extracted from the

GWAS database for UF. However, one SNP that was unmatchable in the

GWAS for UF lacked an available proxy on the SNipA SNP annotator

online platform and was removed from the analysis. Using the

Phenoscanner database, two SNPs associated with confounding

factors, such as age, body mass index and ankylosing spondylitis,

were removed. Therefore, 46 genetically independent variants were

selected as IVs for UFs for use in the subsequent MR analyses

(Table SII). As shown in Table II, no heterogeneity was observed

in the associations between the selected IVs of UF and hOA using

the Cochran's Q test (Q=55.24; P=0.14); therefore, IVW was used as

the primary random-effects model. The IVW results indicated a

significant inverse genetic association between UFs and hOA (OR,

0.941; 95% CI, 0.895-0.990; adjusted P=0.042). Additionally, the

weighted median (OR, 0.914; 95% CI, 0.854-0.979; adjusted P=0.045)

and weighted mode (OR, 0.906; 95% CI, 0.833-0.985; adjusted

P=0.042) were in line with the IVW method (Fig. 2A and B; Table

II). However, MR-Egger analysis did not indicate a genetic

association (OR, 0.928; 95% CI, 0.843-1.021; adjusted P=0.161) nor

the presence of horizontal pleiotropy in the IVs (intercept P=0.73)

(Fig. 2A and B; Table

II), which indicated uncertainty regarding the robustness of

the association estimates.

| Table IIMR results of UF and hOA genetic

association. |

Table II

MR results of UF and hOA genetic

association.

| A, 46 SNPs (Exp,

UF; Out, hOA) |

|---|

| | Heterogeneity

test | Pleiotropy

test |

|---|

| Methods | OR (95% CI) | P-value | Adjusted

P-value | Cochran's Q | P-value | Intercept | P-value |

|---|

| IVW | 0.941 (0.895,

0.990) | 0.018 | 0.042 | 55.24 | 0.14 | | |

| Weighted

median | 0.914 (0.854,

0.979) | 0.011 | 0.045 | | | | |

| MR-Egger | 0.928 (0.843,

1.021) | 0.131 | 0.161 | | | 0.002 | 0.73 |

| Simple mode | 0.909 (0.797,

1.037) | 0.161 | 0.161 | | | | |

| Weighted mode | 0.906 (0.833,

0.985) | 0.025 | 0.042 | | | | |

| B, 25 SNPs (Exp,

hOA; Out, UF) |

| | Heterogeneity

test | Pleiotropy

test |

| Methods | OR (95% CI) | P-value | Adjusted

P-value | Cochran's Q | P-value | Intercept | P-value |

| IVW | 1.030 (0.974,

1.089) | 0.300 | 0.891 | 35.71 | 0.06 | | |

| Weighted

median | 1.017 (0.953,

1.086) | 0.612 | 0.891 | | | | |

| MR-Egger | 0.985 (0.795,

1.220) | 0.891 | 0.891 | | | 0.004 | 0.68 |

| Simple mode | 1.029 (0.909,

1.163) | 0.657 | 0.891 | | | | |

| Weighted mode | 1.010 (0.907,

1.125) | 0.859 | 0.891 | | | | |

A ‘leave-one-out’ analysis was conducted to assess

the influence of each UF-associated SNP on the overall association

with hOA, which provided a sensitivity evaluation of the results

(Fig. 2C). The analysis revealed

that the removal of rs11,7245,733 had a significant impact on the

association, suggesting that this SNP plays a critical role in the

observed relationship between UF and hOA.. The funnel plots are

presented in Fig. S1A.

In the reverse MR analysis, 27 SNPs were extracted

from the hOA GWAS database. However, two SNPs associated with

confounding factors were removed, and 25 genetically independent

variants were selected as the IVs of hOA (Table SII). As shown in Table II, the IVW method did not find a

genetic association between hOA and UFs (OR, 1.030; 95% CI,

0.974-1.089; adjusted P=0.891), and Cochran's Q test did not reveal

any significant heterogeneity (Q=35.71; P=0.06). Additionally, the

MR-Egger analysis corroborated the IVW findings (OR, 0.985; 95% CI,

0.795-1.220; adjusted P=0.891) (Fig.

2D and E; Table II). The MR-Egger analysis also

revealed no evidence of horizontal pleiotropy in the IVs (intercept

P=0.68) (Fig. 2D and E; Table

II).

A ‘leave-one-out’ analysis was carried out to assess

the influence of each hOA-associated SNP on UF, which provided a

sensitivity evaluation and consistency of the findings. The

findings indicated that none of the SNPs exhibited a discernible

effect on the pooled results (Fig.

2F). The funnel plots are presented in Fig. S1B.

Genetic associations between UFs and

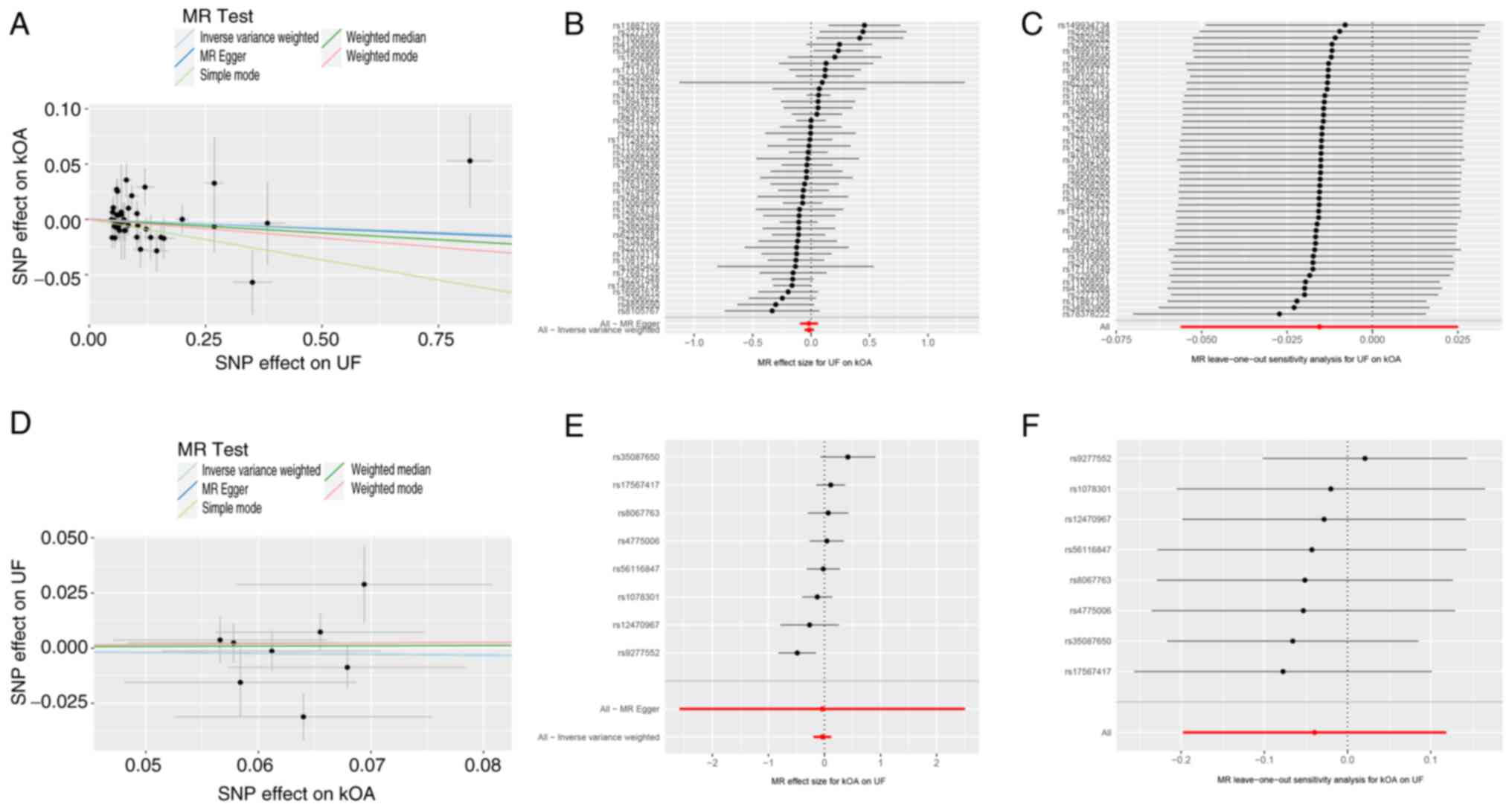

kOA

As aforementioned, 46 genetically independent

variants were identified and selected as IVs for the UF analysis

(Table SII). In the primary

analysis using the IVW method, no genetic association was found

between UFs and kOA (OR, 0.985; 95% CI, 0.945-1.025; adjusted

P=0.569). Cochran's Q test indicated the absence of significant

heterogeneity in the results (Q=57.20; P=0.10) (Fig. 3A and B; Table

III). The results of the MR-Egger analysis were consistent with

those of the IVW analysis (OR, 0.983; 95% CI, 0.910-1.062; adjusted

P=0.662), which indicated the absence of horizontal pleiotropy in

the IVs (intercept P=0.956) (Fig.

3A and B; Table III). Furthermore, the result of

the ‘leave-one-out’ analysis indicated that the genetic association

between UF and kOA was not associated to a single SNP (Fig. 3C). The funnel plots are presented

in Fig. S1C.

| Table IIIMR results of UF and kOA genetic

association. |

Table III

MR results of UF and kOA genetic

association.

| A, 46 SNPs (Exp,

UF; Out, kOA) |

|---|

| | Heterogeneity

test | Pleiotropy

test |

|---|

| Methods | OR (95% CI) | P-value | Adjusted

P-value | Cochran's Q | P-value | Intercept | P-value |

|---|

| IVW | 0.985 (0.945,

1.025) | 0.455 | 0.569 | 57.20 | 0.10 | | |

| Weighted

median | 0.976 (0.921,

1.034) | 0.409 | 0.569 | | | | |

| MR-Egger | 0.983 (0.910,

1.062) | 0.662 | 0.662 | | | 0.0002 | 0.956 |

| Simple mode | 0.930 (0.835,

1.035) | 0.191 | 0.569 | | | | |

| Weighted mode | 0.967 (0.886,

1.054) | 0.454 | 0.569 | | | | |

| B, 8 SNPs (Exp,

kOA; Out, UF) |

| | Heterogeneity

test | Pleiotropy

test |

| Methods | OR (95% CI) | P-value | Adjusted

P-value | Cochran's Q | P-value | Intercept | P-value |

| IVW | 0.961 (0.820,

1.126) | 0.624 | 0.975 | 13.18 | 0.07 | | |

| Weighted

median | 1.016 (0.872,

1.182) | 0.841 | 0.975 | | | | |

| MR-Egger | 0.960 (0.075,

12.247) | 0.975 | 0.975 | | |

7.68x10-5 | 0.999 |

| Simple mode | 1.033 (0.833,

1.283) | 0.774 | 0.975 | | | | |

| Weighted mode | 1.033 (0.855,

1.249) | 0.744 | 0.975 | | | | |

In the reverse MR analysis, the genetic associations

between kOA and UFs were analyzed using the same aforementioned

methodology. In total, 10 SNPs were extracted from the GWAS for

UFs, and eight variants were identified as IVs (Table SII). The subsequent analysis

revealed the absence of a genetic association of kOA on UFs using

the IVW method (OR, 0.961; 95% CI, 0.820-1.126; adjusted P=0.975),

which aligned with the result obtained from the MR-Egger method

(OR, 0.960; 95% CI, 0.075-12.247; adjusted P=0.975) (Fig. 3D and E; Table

III). The MR-Egger analysis showed no evidence of horizontal

pleiotropy among the IVs (intercept P=0.999) (Fig. 3D and E; Table

III). Furthermore, Cochran's Q test revealed no heterogeneity

(Q=13.18; P=0.07) (Table III).

Additionally, the results of the ‘leave-one-out’ analysis indicated

that the genetic association of kOA on UF was not attributable to a

single SNP (Fig. 3F). The funnel

plots are presented in Fig.

S1D.

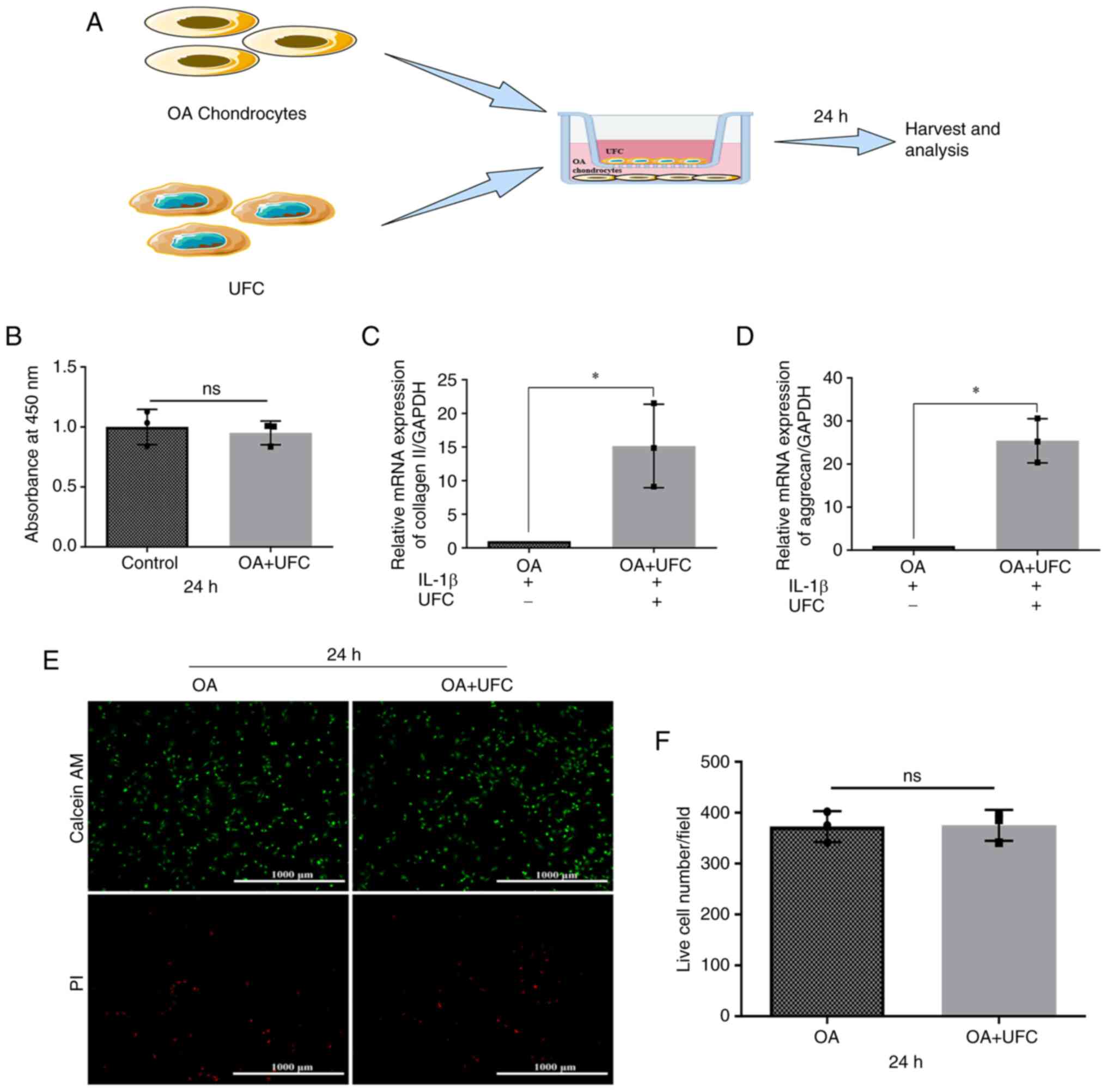

Investigating the role of UFCs in OA

chondrocyte degeneration

A Transwell co-culture system was used to

investigate the effects of UFCs on chondrocytes of OA. Rat

chondrocytes were cultured in the lower chamber and pre-treated

with IL-1β for 2 h to mimic an inflammatory cartilage environment.

UFCs were then cultured in the upper chamber for another 24 h

(Fig. 4A). The CCK-8 assay

indicated that there was no significant difference in the viability

of chondrocytes after exposure to UFCs compared with those in the

control group not exposed to UFCs (Fig. 4B). This was further confirmed by

live/dead cell staining (Fig. 4E

and F). Furthermore, it was

demonstrated that the mRNA levels of Collagen II and Aggrecan were

increased in the chondrocytes treated with UFCs compared with the

chondrocytes that were not co-cultured with UFCs (Fig. 4C and D). These results suggested that UFCs

reduced the levels of markers of chondrocyte degeneration in

vitro, which indicated a possible biological interaction that

warrants further basic mechanistic investigation.

Discussion

In the present study, a bidirectional MR analysis

was carried out using population-based genetic datasets to

investigate the potential genetic association between OA of

weight-bearing joints and the risk of UF. Analysis using the IVW

method indicated an inverse genetic association between genetic

liability to UF and hOA, whereas this association was not observed

in the MR-Egger analysis. This discrepancy highlights the need for

cautious interpretation of the findings of the present study. The

IVW method estimates the association between genetically predicted

exposure and outcome through a weighted regression of SNP-specific

Wald ratios (βoutcome/βexposure), which may

be more sensitive to undetected pleiotropy or confounding factors

(29). The MR-Egger method tests

for directional pleiotropy and provides an assessment of potential

associations, but the strength of evidence is reduced when

accounting for pleiotropy or other unmeasured confounders (35,41).

Therefore, the inconsistency between these two analyses introduced

uncertainty regarding the robustness and interpretation of these

associations. Given the potential limitations in the robustness of

these association inferences from MR analysis, in vitro

co-culture experiments were carried out. These in vitro

experiments used OA chondrocytes and UFCs to provide additional

biological insights. In the present study, IL-1β-stimulated rat

chondrocytes were co-cultured with UFCs to mimic an inflammatory

cartilage environment. The experiments demonstrated that the

presence of UFCs in the co-culture system significantly inhibited

the IL-1β-induced reduction in Aggrecan and Collagen II mRNA

expression in chondrocytes, compared with the OA group. These

results suggest a potential interaction between UFCs and

IL-1β-stimulated chondrocytes, but further mechanistic studies are

needed to validate these findings.

Numerous studies have investigated the potential

associations of various exposures on OA, but the results have been

unfavorable (26,28,42).

For example, a previous MR analysis demonstrates that elevated

serum testosterone and dihydrotestosterone levels may increase the

risk of total hip arthroplasty (26). IVs linked to genetic

predispositions for osteoporosis are associated with an increased

risk of OA, and increasing bone mineral density serves as an

effective strategy to prevent OA (42). Furthermore, MR analysis reveals an

association between OA and bladder cancer (28). However, the association between UFs

and OA is yet to be elucidated. UFs, the most common benign tumor

among women of reproductive age, have an etiology that is still not

completely understood (9). An

observational study by Kovari et al (25) reports a notably higher prevalence

of UFs in patients diagnosed with hOA, which contradict the MR

findings of the present study. One possible explanation for this

discrepancy may involve estrogen (specifically, E2). Previous

studies reveal that elevated serum E2 levels are associated with an

increased risk of UFs, while emerging evidence suggests that E2 may

exert anti-degenerative effects on cartilage, potentially

influencing OA onset or progression (7-9).

Systemic E2 levels in patients with UFs may

contribute to protection against OA via estrogen receptor signaling

(43). However, this mechanism

alone cannot explain the results of the present study, which

demonstrated in vitro that UFCs restrained the IL-1β-induced

reduction of Aggrecan and Collegen II in chondrocytes at the mRNA

level. Given that UFCs do not secrete E2, the observed reduction in

IL-1β-induced reduction of Aggrecan and Collagen II in chondrocytes

may involve alternative mechanisms, such as paracrine

anti-inflammatory signaling or modulation of receptor sensitivity

in chondrocytes (44). Integrating

these findings with the findings of the MR analysis in the present

study, we hypothesize that the inverse association between UF and

hOA likely reflects indirect biological interactions mediated by

alterations in the tumor microenvironment instead of direct effects

of the tumor itself. For example, changes in hormonal levels,

immune cell modulation and inflammatory cytokine profiles within

the tumor microenvironment may influence cartilage metabolism or

immune homeostasis in anatomically adjacent tissues, such as the

hip joint (7,44). This localized paracrine mechanism

may partially account for the anatomical specificity observed in

the MR findings of the present study, in which UF was inversely

associated with hOA, an anatomically adjacent site, but not with

kOA. This specificity may be attributed to the proximity of the

uterus to the hip, which potentially facilitates local crosstalk or

signaling gradients that may not extend to more distant joints.

The findings of the present study indicated novel

evidence of a potential genetic link between UF and hOA, suggesting

that the association between UF pathophysiology and joint

degeneration may be more complex than previously considered

(45,46). However, as the simplified in

vitro model used in the present study cannot fully recapitulate

the complex biological environment of OA, the proposed hypothesis

is speculative. Further comprehensive mechanistic experiments

involving in vivo models and clinical samples are required

to validate these interactions.

However, there were a number of limitations in the

present study that should be considered. Firstly, the present study

was limited by the relatively small number of SNPs. Therefore, to

enhance the validity of the MR analyses, larger GWAS datasets

should be used and a broader array of SNPs should be incorporated

as IVs in future investigations. Secondly, the background of the

patients included in the present study were restricted to those

with European ancestry, and the instruments identified within

European populations may not be applicable to non-European groups.

Therefore, additional MR analyses that include a broader range of

ethnic groups are required. Furthermore, the weak instruments used

in MR analyses can lead to biased and inconsistent association

estimates. Therefore, to assess the strength of the IVs used in the

present study, F-statistics for each SNP was calculated. The

results of the present study showed that the F-statistics for the

instruments exceeded the commonly accepted threshold of 10,

indicating that the instruments were strong and the risk of weak

instrument bias was minimized. However, despite the apparent

strength of the instruments, the possibility of a weak instrument

bias affecting the association estimates cannot be excluded. Weak

instrument bias could lead to attenuated or distorted estimates,

undermining the validity of the conclusions of the present study.

Although, precautions to mitigate this risk were taken in the

present study, further research using alternative IVs or additional

methodological approaches may strengthen the robustness of the

findings of the present study. Finally, the MR analysis combined

with the cellular experiments used in the present study assumed a

unidirectional association between exposure and outcome. However,

biological systems may include complex feedback loops, potentially

affecting the interpretation of results (47).

In conclusion, the novelty of the present study was

in the integration of the bidirectional MR with in vitro

co-culture experiments, an approach that, to the best of our

knowledge, has not previously been used to investigate the

association between UF and hOA. Using this combined strategy the

present study proposed a novel microenvironment-mediated mechanism

that may explain the possible inverse association and its

anatomical specificity. Furthermore, a possible inverse genetic

association between UF and the risk of hOA was demonstrated in the

present study. This was further suggested by the findings of the

in vitro experiments, which demonstrated that Aggrecan and

Collagen II mRNA levels were increased in IL-1β-induced

chondrocytes in the presence of UFCs, compared with that in the OA

group. Furthermore, we hypothesize that this association

potentially reflects indirect effects mediated by the tumor

microenvironment instead of the direct effects of fibroids

themselves. However, due to the discrepancies across the MR

analytical approaches, further detailed mechanistic studies are

warranted to validate the hypothesis of the present study, which

may potentially provide a framework for integrating genetic

epidemiology with experimental biology when investigating complex

disease interactions.

Supplementary Material

Funnel plot. (A) Funnel plot of the

estimated associations of (A) UF on hOA, (B) hOA on UF, (C) UF on

kOA and (D) kOA on UF. UF, uterine fibroids; OA, osteoarthritis;

hOA, hip OA; kOA, knee OA; IV, instrumental variables; MR,

mendalian randomization; SEIV, standard error of IVs.

Baseline profiles of the cohort used

in the present study.

Characteristics of SNPs used as

genetic instruments in UF and hOA.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: The present work was supported by the National Natural

Science Foundation of China Key Programme (grant no. 32130052) and

the National Natural Science Foundation of China Major Research

Plan (grant no. 91949203).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

XM, SM, TW and YZ conceived and designed the present

study. XM, JM, XJ, HZ and SM collected, analyzed and interpreted

the data. XM and SM drafted the manuscript. XM, JM, XJ, TW and YZ

revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final

version of the manuscript. XM and YZ confirm the authenticity of

all the raw data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Jaramillo Quiceno GA, Sarmiento Riveros

PA, Ochoa Perea GA, Vergara MG, Rodriguez Muñoz LF, Arias Perez RD,

Piovesan NO and Muñoz Salamanca JA: Satisfactory clinical outcomes

with autologous matrix-induced chondrogenesis in the treatment of

grade IV chondral injuries of the knee. J ISAKOS. 8:86–93.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Sacitharan PK: Ageing and Osteoarthritis.

Subcell Biochem. 91:123–159. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Atasoy-Zeybek A, Showel KK, Nagelli CV,

Westendorf JJ and Evans CH: The intersection of aging and estrogen

in osteoarthritis. NPJ Women's Health. 3(15)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Nelson AE, Smith MW, Golightly YM and

Jordan JM: ‘Generalized osteoarthritis’: A systematic review. Semin

Arthritis Rheum. 43:713–720. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Loughlin J: Translating osteoarthritis

genetics research: Challenging times ahead. Trends Mol Med.

28:176–182. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Cho HJ, Morey V, Kang JY, Kim KW and Kim

TK: Prevalence and risk factors of spine, shoulder, hand, hip, and

knee osteoarthritis in community-dwelling koreans older than age 65

years. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 473:3307–3314. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Nevitt MC, Cummings SR, Lane NE, Hochberg

MC, Scott JC, Pressman AR, Genant HK and Cauley JA: Association of

estrogen replacement therapy with the risk of osteoarthritis of the

hip in elderly white women. Study of osteoporotic fractures

research group. Arch Intern Med. 156:2073–2080. 1996.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Fan DX, Yang XH, Li YN and Guo L:

17β-Estradiol on the Expression of G-Protein coupled estrogen

receptor (GPER/GPR30) mitophagy, and the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway

in ATDC5 chondrocytes in vitro. Med Sci Monit. 24:1936–1947.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Yang Q, Ciebiera M, Bariani MV, Ali M,

Elkafas H, Boyer TG and Al-Hendy A: Comprehensive review of uterine

fibroids: Developmental origin, pathogenesis, and treatment. Endocr

Rev. 43:678–719. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Dennison EM: Osteoarthritis: The

importance of hormonal status in midlife women. Maturitas.

165:8–11. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Lu Z, Zhang A, Wang J, Han K and Gao H:

Estrogen alleviates post-traumatic osteoarthritis progression and

decreases p-EGFR levels in female mouse cartilage. BMC

Musculoskelet Disord. 23(685)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Al-Hendy A, Myers ER and Stewart E:

Uterine fibroids: Burden and unmet medical need. Semin Reprod Med.

35:473–480. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Baird DD, Dunson DB, Hill MC, Cousins D

and Schectman JM: High cumulative incidence of uterine leiomyoma in

black and white women: Ultrasound evidence. Am J Obstet Gynecol.

188:100–107. 2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Kho PF and Mortlock S: Endometrial Cancer

Association Consortium; International Endometriosis Genetics

Consortium. Rogers PAW, Nyholt DR, Montgomery GW, Spurdle AB, Glubb

DM and O'Mara TA: Genetic analyses of gynecological disease

identify genetic relationships between uterine fibroids and

endometrial cancer, and a novel endometrial cancer genetic risk

region at the WNT4 1p36.12 locus. Hum Genet. 140:1353–1365.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Stewart EA, Cookson CL, Gandolfo RA and

Schulze-Rath R: Epidemiology of uterine fibroids: A systematic

review. BJOG. 124:1501–1512. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Stewart EA, Laughlin-Tommaso SK, Catherino

WH, Lalitkumar S, Gupta D and Vollenhoven B: Uterine fibroids. Nat

Rev Dis Primers. 2(16043)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Borahay MA, Asoglu MR, Mas A, Adam S,

Kilic GS and Al-Hendy A: Estrogen receptors and signaling in

fibroids: Role in pathobiology and therapeutic implications. Reprod

Sci. 24:1235–1244. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Tal R and Segars JH: The role of

angiogenic factors in fibroid pathogenesis: Potential implications

for future therapy. Hum Reprod Update. 20:194–216. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Kapoor M, Martel-Pelletier J, Lajeunesse

D, Pelletier JP and Fahmi H: Role of proinflammatory cytokines in

the pathophysiology of osteoarthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 7:33–42.

2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Blaney Davidson EN, van der Kraan PM and

van den Berg WB: TGF-beta and osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis

Cartilage. 15:597–604. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Ciebiera M, Włodarczyk M, Wrzosek M,

Męczekalski B, Nowicka G, Łukaszuk K, Ciebiera M,

Słabuszewska-Jóźwiak A and Jakiel G: Role of transforming growth

factor β in uterine fibroid biology. Int J Mol Sci.

18(2435)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Pang H, Chen S, Klyne DM, Harrich D, Ding

W, Yang S and Han FY: Low back pain and osteoarthritis pain: A

perspective of estrogen. Bone Res. 11(42)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Wright VJ, Schwartzman JD, Itinoche R and

Wittstein J: The musculoskeletal syndrome of menopause.

Climacteric. 27:466–472. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Felson DT, Lawrence RC, Dieppe PA, Hirsch

R, Helmick CG, Jordan JM, Kington RS, Lane NE, Nevitt MC, Zhang Y,

et al: Osteoarthritis: New insights. Part 1: the disease and its

risk factors. Ann Intern Med. 133:635–646. 2000.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Kovari E, Kaposi A, Bekes G, Kiss Z,

Kurucz R, Mandl P, Balint GP, Poor G, Szendroi M and Balint PV:

Comorbidity clusters in generalized osteoarthritis among female

patients: A cross-sectional study. Semin Arthritis Rheum.

50:183–191. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Yan YS, Qu Z, Yu DQ, Wang W, Yan S and

Huang HF: . Sex steroids and osteoarthritis: A mendelian

randomization study. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne).

12(683226)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Hill HA, Schoenbach VJ, Kleinbaum DG,

Strecher VJ, Orleans CT, Gebski VJ and Kaplan BH: A longitudinal

analysis of predictors of quitting smoking among participants in a

self-help intervention trial. Addict Behav. 19:159–173.

1994.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Zhang X, Wen Z, Xing Z, Zhou X, Yang Z,

Dong R and Yang J: The causal relationship between osteoarthritis

and bladder cancer: A Mendelian randomization study. Cancer Med.

13(e6829)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Chen D, Xu H, Sun L and Li Y, Wang T and

Li Y: Assessing causality between osteoarthritis with urate levels

and gout: A bidirectional Mendelian randomization study.

Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 30:551–558. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Bowden J and Holmes MV: Meta-analysis and

mendelian randomization: A review. Res Synth Methods. 10:486–496.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Tachmazidou I, Hatzikotoulas K, Southam L,

Esparza-Gordillo J, Haberland V, Zheng J, Johnson T, Koprulu M,

Zengini E, Steinberg J, et al: Identification of new therapeutic

targets for osteoarthritis through genome-wide analyses of UK

Biobank data. Nat Genet. 51:230–236. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Sakaue S, Kanai M, Tanigawa Y, Karjalainen

J, Kurki M, Koshiba S, Narita A, Konuma T, Yamamoto K, Akiyama M,

et al: A cross-population atlas of genetic associations for 220

human phenotypes. Nat Genet. 53:1415–1424. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Skrivankova VW, Richmond RC, Woolf BAR,

Yarmolinsky J, Davies NM, Swanson SA, VanderWeele TJ, Higgins JPT,

Timpson NJ, Dimou N, et al: Strengthening the reporting of

observational studies in epidemiology using mendelian

randomization: The STROBE-MR Statement. JAMA. 326:1614–1621.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Cao Z, Wu Y, Li Q, Li Y and Wu J: A causal

relationship between childhood obesity and risk of osteoarthritis:

Results from a two-sample Mendelian randomization analysis. Ann

Med. 54:1636–1645. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Ni J, Zhou W, Cen H, Chen G, Huang J, Yin

K and Sui C: Evidence for causal effects of sleep disturbances on

risk for osteoarthritis: A univariable and multivariable Mendelian

randomization study. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 30:443–450.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Palmer TM, Lawlor DA, Harbord RM, Sheehan

NA, Tobias JH, Timpson NJ, Davey Smith G and Sterne JA: Using

multiple genetic variants as instrumental variables for modifiable

risk factors. Stat Methods Med Res. 21:223–242. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Bowden J, Davey Smith G and Burgess S:

Mendelian randomization with invalid instruments: effect estimation

and bias detection through Egger regression. Int J Epidemiol.

44:512–525. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Bowden J, Del Greco MF, Minelli C, Davey

Smith G, Sheehan NA and Thompson JR: Assessing the suitability of

summary data for two-sample mendelian randomization analyses using

MR-egger regression: The role of the I2 statistic. Int J Epidemiol.

45:1961–1974. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Inkster AM, Konwar C, Peñaherrera MS,

Brain U, Khan A, Price EM, Schuetz JM, Portales-Casamar É, Burt A,

Marsit CJ, et al: Profiling placental DNA methylation associated

with maternal SSRI treatment during pregnancy. Sci Rep.

12(22576)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: . Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 25:402–408.

2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Bowden J, Davey Smith G, Haycock PC and

Burgess S: Consistent estimation in mendelian randomization with

some invalid instruments using a weighted median estimator. Genet

Epidemiol. 40:304–314. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Qu Y, Chen S, Han M, Gu Z, Zhang Y, Fan T,

Zeng M, Ruan G, Cao P, Yang Q, et al: Osteoporosis and

osteoarthritis: A bi-directional Mendelian randomization study.

Arthritis Res Ther. 25(242)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Zhao Z, Niu S, Chen J, Zhang H, Liang L,

Xu K, Dong C, Su C, Yan T, Zhang Y, et al: G protein-coupled

receptor 30 activation inhibits ferroptosis and protects

chondrocytes against osteoarthritis. J Orthop Translat. 44:125–138.

2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Bulun SE, Yin P, Wei J, Zuberi A, Iizuka

T, Suzuki T, Saini P, Goad J, Parker JB, Adli M, et al: UTERINE

FIBROIDS. Physiol Rev. 105:1947–1988. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Kiely M, Lord B and Ambs S: Immune

response and inflammation in cancer health disparities. Trends

Cancer. 8:316–327. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Coussens LM and Werb Z: Inflammation and

cancer. Nature. 420:860–867. 2002.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Haycock PC, Burgess S, Wade KH, Bowden J,

Relton C and Davey Smith G: Best (but oft-forgotten) practices: The

design, analysis, and interpretation of Mendelian randomization

studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 103:965–978. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|