Introduction

Pearl powder is a Traditional Chinese Medicine with

a variety of active substrates, which can be applied for numerous

processes, such as wound healing and bone repair, rendering it a

promising biological agent. The nacre organic matrix, an active

component of pearl powder, mainly regulates the mineralization of

bivalve mollusks (1). The nacre is

an organic/inorganic complex that is not too dissimilar to human

bone tissues (2). In addition, the

organic matrix of pearl powder is the processed product of pearl

powder (3). The solvent capable of

dissolving the organic components of the medium is typically

combined with the pearl powder components, which are obtained by

centrifugation, freezing and other methods such as supercritical

CO2 extraction and enzyme-acid extraction. The insoluble

matrix components are then removed and the soluble organic matrix

is retained (4). Pearl powder has

been applied in traditional Chinese medicine and cosmetics for

>1,000 years (5). Chiu et

al (6) previously found that

pearl powder extract can prolong the life of Caenorhabditis

elegans. Additionally, in the same study, 20 subjects (aged

38-50 years) were administered pearl powder capsules and placebo.

After 10 weeks of treatment, antioxidant-related indices were found

to be increased in plasma samples, suggesting that pearl powder has

antioxidant activity (6). This

also suggests the potential of pearl powder for the treatment of

age-related degenerative diseases. Chen et al (7) conducted in vitro and in

vivo experiments with pearl powder with different particle

sizes, and found that the mixed preparation of pearl

powder/glycerol/normal saline could promote the proliferation and

migration of fibroblasts, accelerate wound closure and promote skin

angiogenesis in full-thickness skin excision wounds in

Sprague-Dawley rats and shaped dermal wounds in New Zealand

rabbits. In another study, Zhang et al (8) assessed the effects of pearl powder

and its extract on the motor ability and anticonvulsant ability of

mice, where the results showed that rearing was inhibited in

ordinary mice, whilst the convulsant latency of pentylenetetrazol

model mice was prolonged. These results provide the basis for the

development of sedative drugs based on pearl powder.

The bone tissue is comprised of a diverse range of

cell components, namely preosteoblasts, osteoblasts and

osteoclasts, which jointly modulate the growth and absorption of

bone tissues (9). Osteoblasts,

derived from bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), serve a

function in osteogenesis and serve a critical role during bone

remodeling. Specifically, osteoblasts promote bone tissue formation

by secreting organic matrix and regulating calcification (10). Certain cytokines, such as TNF-α,

have an important role in regulating bone metabolism (11). This cytokine, produced mainly by

activated macrophages, T lymphocytes, activated macrophages,

monocytes, CD4+ T cells, B cells, neutrophils and mast

cells, induces apoptosis of leukemia cell lines in vitro and

stimulates osteoclast activation, and TNFα promotes osteoblast

differentiation and bone formation by polarizing macrophages to

secrete insulin like 6 and Jagged1, while anti-TNF treatment may

indirectly affect osteoblast activity by inhibiting the expression

of these factors, which in turn promotes bone degradation (12,13).

Other factors, such as transcriptional coactivator Yes1-associated

transcriptional regulator (YAP), also serve important roles in

osteogenesis. YAP acts as a key molecular bridge connecting the

mechanical microenvironment (substrate size/spatial features) to

osteogenic differentiation, directly mediating the sequential

regulation of MSC and osteoblast differentiation through focal

adhesion-dependent cytoskeletal tension (regulated by F-actin and

phospho-myosin light chain 2) that drives its nuclear localization.

This mechanoregulatory role has further been confirmed in

cytoskeleton disruption assays (14).

As an active component of nacre pearls, nacre powder

organic matrix has been documented to regulate the mineralization

of bivalve mollusks such as Pinctada spp. and Crassostrea

gigas, where its effects on osteoblasts has been extensively

studied (1,15).

Pearl powder is similar to nacre powder. Pearl

powder and nacre powder differ in their origins: Natural pearls

form when foreign irritants (such as sand or parasites)

accidentally enter oysters and become progressively mineralized

under nacreous encapsulation (16). By contrast, the nacreous layer

constitutes a laminated composite material secreted by mantle

epithelial cells, characterized by alternating deposition of

calcium carbonate crystals and chitinous proteins (17). Both materials share similar

chemical compositions, containing 95% calcium carbonate and 5%

organic components, including diverse amino acids, trace elements,

vitamins and bioactive peptides (18,19).

Notably, their core bioactive constituents derive from the organic

matrix, which is a complex system comprising proteins,

polypeptides, glycoproteins, chitin, lipids and pigments (18,19).

A proteomic study has revealed compositional differences between

nacre from Pinctada maxima (Kamingi shell) and that of

cultured pearls in protein profiles (20). This structure confers

osteoinductive properties, enabling stimulation of osteoblast

differentiation via the bone morphogenetic protein 2/Smad signaling

pathway and biomimetic mineralization, making it suitable for bone

regeneration applications (21).

However, to the best of our knowledge, research on the effect of

the organic matrix extracted from pearl powder on osteoblasts

remains scarce. In the present study, hFOB1.19 cells were cultured

with the water-soluble matrix (WSM) derived from nanometer pearl

powder (NPP) to analyze its possible effects on the osteogenic

differentiation of these osteoblasts. It is hoped that the present

study will encourage the application of pearl powder for promoting

bone formation in the clinic. In particular, pearl powder WSM can

be applied in artificial bone materials or for the treatment of

osteoporosis.

Materials and methods

NPP WSM preparation

Micron-grade pearl powder (Hainan Jingrun Pearl Co.,

Ltd.) was first ground into nano-grade pearl powder. Briefly, a

CNB-T1L nanorstick needle mill (Dongguan Kangbo Machinery Co. Ltd.)

was used, sterile distilled water was used for cleaning to

eliminate potential contaminants, anhydrous ethanol was used as the

medium, the rotation speed of the main engine was set at 540 x g,

the feed pressure was 0.35 kPa, the mass/volume ratio was 1:15

(g/ml) to add pearl powder, and mechanical grinding was performed

for 1 h at room temperature (25˚C). A uniform nanosuspension was

obtained. The slurry was oven-dried at 60˚C for 24 h, manually

pulverized using a ceramic mortar in a clean workbench, sieved

through a 120 mesh, and stored as uniform nanopearl powder in

sterile containers. After freeze drying and irradiation

sterilization, the pearl powder was mixed with Milli-Q ultra-pure

water (MilliporeSigma) at a ratio of 1:2 (g/ml), before the

supernatant was collected by centrifugation (500 x g; 20 h) at room

temperature (25˚C). The sample was later filtered with a 0.22-µm

strainer and freeze-dried to obtain the WSM powder, which was then

dissolved in PBS. The stock WSM protein concentration was

determined using the BCA protein quantitative kit and the stock

solution was stored at 4˚C. The protein concentration of WSM

calculated by the BCA protein assay method was 2.689 mg/ml. It was

calculated that 134.47 mg protein could be extracted per 100 g of

nano-pearl powder. WSM was then diluted to 10, 20 and 40 µg/ml

before the subsequent experiments.

hFOB1.19 cell culture

hFOB1.19 cells (cat. no. CL-0353; Procell Life

Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) were cultivated in DMEM/F12

(cat. no. C11330500BT; Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.)

containing 10% FBS (cat. no. 10099141C; Gibco; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) and 0.3 mg/ml G418 [cat. no. 1811031;

Geneticin™ Selective Antibiotic (G418 Sulfate); Gibco;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.] in a 5% CO2 atmosphere

at 34˚C. The medium was changed every 2 days. After reaching 80-90%

confluency, trypsin (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) was

added to digest the cells and 1:2 passaging was performed. In the

experimental groups, solutions of 10, 20 and 40 µg/ml WSM were

added to the cells, whilst an equal amount of complete medium was

added to the control group. Co-cultures were incubated for 1, 4, 7

and 14 days as required. The cultures were incubated at 34˚C in a

5% CO2 atmosphere.

Cell differentiation detection based

on alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity

Cells in passage 3 were selected and inoculated into

a 24-well plate at 2x105 cells/well. The cells were

grouped as aforementioned and three replicate wells were set up for

every group. The culture medium was discarded when the cells

attached to the well, before WSM was added. After intervention for

1, 4 and 7 days at 34˚C with 5% CO2, the medium was

discarded, and subsequent procedures were conducted according to

the ALP kit manufacturer's protocol (cat. no. A059-1-1; Nanjing

Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute). The absorbance was measured

using an absorbance reader (800TS; BioTek; Agilent Technologies,

Inc.).

Cell mineralization detection by

alizarin red staining

Cells in passage 3 were selected and inoculated into

6-well plates at 5x106 cells/well. Cell grouping and

culture were performed following the same method as those performed

for measuring ALP activity. Medium was removed after culturing for

7 and 14 days, before the cells were washed three times with PBS

for 5 min each and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min at

25˚C. After washing with PBS three times again, 4 ml 2% alizarin

red solution (cat. no. DF0563; Yingxin Biotechnology, Co., Ltd.)

was added to every well for 15 min at ambient temperature (25˚C)

for staining. Following further washing with PBS three times, the

calcified nodules formed were monitored using an LED light

microscope (Nikon TS100; Nikon Corporation), before images were

collected and the relative absorbance value (595 nm) of the

mineralized area (ImageJ Software 1.54a; National Institutes of

Health) was determined for statistical analysis.

Relevant osteogenic gene expression

levels measured by reverse transcription-quantitative PCR

(RT-qPCR)

Cells in passage 3 were selected and inoculated into

a 6-well plate at 5x106 cells/well. Cell grouping and

culture were conducted with the same method as those performed for

measuring ALP activity. The medium was removed following a 7-day

culture and TRNzol Universal Reagent (cat. no. DP424; Tiangen

Biotech Co., Ltd.) was utilized to extract the total cellular RNA.

The RNA concentration and purity were determined by an ultraviolet

spectrophotometer (BioTek; Agilent Technologies, Inc.).

Subsequently, 0.85 µg RNA was reverse transcribed using a

PrimeScript™ RT Master Mix (Perfect Real Time; cat. no.

RR036A; Takara Bio, Inc.) to synthesize cDNA at 37˚C for 15 min and

85˚C for 5 sec. The cDNA was used as the template and amplified

according to the instructions of the Hieff® qPCR SYBR

Green Master Mix (cat. no. 11201ES08; Shanghai Yeasen Biotechnology

Co., Ltd.). The relative mRNA expression levels of type I collagen

(Col-I), osteocalcin (OCN), osteopontin (OPN) and Runt-associated

transcription factor 2 (Runx-2) were detected by 2-ΔΔCq

method, with GAPDH as the reference gene (22). Table

I displays the primers. The qPCR conditions included

pre-denaturation at 95˚C for 5 min, followed by 40 cycles of

denaturation at 95˚C for 10 sec and annealing at 60˚C for 30

sec.

| Table IPrimers designed for reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR. |

Table I

Primers designed for reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR.

| Gene | Sequence

(5'-3') |

|---|

| GAPDH |

CACCCACTCCTCCACCTTTGAC |

| |

GTCCACCACCCTGTTGCTGTAG |

| Collagen-I |

CCTGCCTGGTGAGAGAGGT |

| |

AGTAGCACCATCATTTCCACGA |

| Osteocalcin |

AGCAAAGGTGCAGCCTTTG |

| |

GCGCCTGGGTCTCTTCACT |

| Osteopontin |

GACCTGAACGCGCCTTCTGAT |

| |

ATCTGGACTGCTTGTGGCTGTG |

| Runt-associated

transcription factor 2 |

CCGCTTCTCCAACCCACGAAT |

| |

TGGCAGGTAGGTGTGGTAGTGA |

Relevant osteogenic protein expression

levels detected by western blotting

Western blotting was performed according to Jurisic

et al (23). Cells in

passage 3 were selected and inoculated into a 6-well plate at

5x106 cells/well. Cell grouping and culture were

conducted with the same method as those performed for measuring ALP

activity. The medium was removed following a 7-day culture, before

cellular proteins were extracted from every group using RIPA lysis

buffer (cat. no. BL504A; Biosharp Life Sciences). The protein

concentration was quantified using the BCA method. Equal amounts of

protein (50 µg per lane) were resolved by 12% SDS-PAGE and

electrophoretically transferred onto 0.22-µm PVDF membranes. The

proteins were transferred onto PVDF membranes, which were

subsequently blocked with 5% skimmed milk in TBS with 20% Tween 20

(cat. no. ST1726; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) for 1 h at

room temperature (25˚C). The membranes were then incubated with the

primary antibodies at 4˚C overnight. The primary antibodies (all

from Affinity Biosciences) were as follows: Rabbit polyclonal Col-I

(cat. no. AF7001; 1:1,000), rabbit polyclonal OCN (cat. no.

DF12303; 1:1,000), rabbit polyclonal OPN (cat. no. AF0227;

1:1,000); rabbit polyclonal Runx-2 (cat. no. AF5186; 1:1,000) and

rabbit polyclonal GAPDH (cat. no. AF7021; 1:10,000). The membrane

was then incubated with goat anti-rabbit IgG (H + L) HRP secondary

antibody (cat. no. S0001; 1:10,000; Affinity Biosciences, Ltd.) at

room temperature for 1 h. The Affinity™ ECL kit

(femtogram) (cat. no. KF8003; Affinity Biosciences, Ltd.) was used

for band exposure development. Finally, ImageJ software

(version1.53e; National Institutes of Health) was used for the

semi-quantitative analysis of the protein bands, before the ratio

between the target protein and the internal reference protein

(GAPDH) was calculated for statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis

Each assay was conducted three times. The

experimental data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation.

Statistical analysis and mapping were performed using GraphPad

Prism 8.2.1 software (Dotmatics). Data among several groups were

compared by one-way analysis of variance. The Tukey post hoc test

was used for analysis of variance. P<0.05 was considered to

indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Effects of different NPP WSM

concentrations on the early osteogenic differentiation of

cells

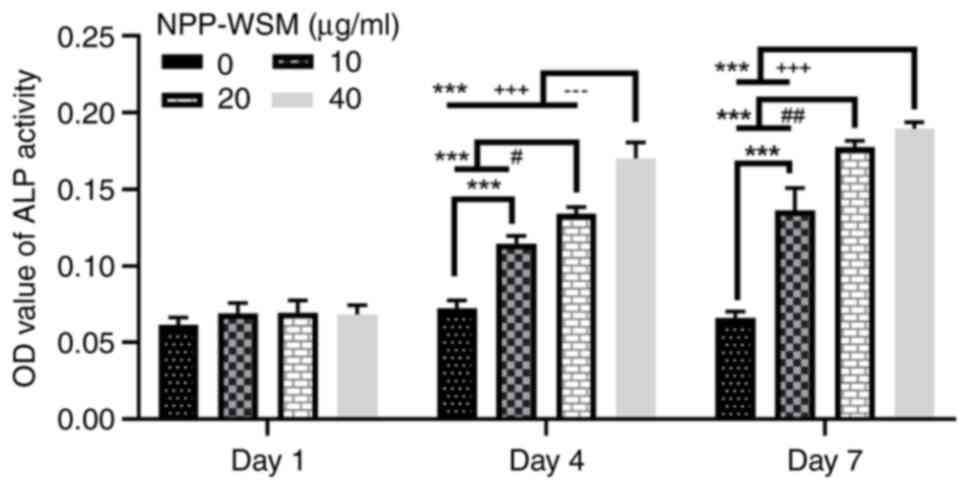

The ALP activity was not found to be significantly

different among all experimental groups after 1 day of treatment

with WSM (Fig. 1). Following WSM

treatment for 4 and 7 days, the ALP activity was enhanced as the

WSM concentration increased, as significant differences were

detected between the groups with different WSM concentrations and

the control group. On day 4, significant differences were observed

between all treatment groups and the control group, demonstrating a

concentration-dependent increase in ALP activity. By day 4, there

were statistically significant differences between each treatment

group and the control group, and between all treatment groups. By

day 7, statistically significant variations were noted not only

between each treatment group and the control group, but also

between the 10 µg/ml group and both the 20 and 40 µg/ml groups.

However, no significant difference was detected between the 20 and

40 µg/ml groups on day 7 (Fig. 1).

Therefore, these data suggest that WSM promoted the secretion and

activity of ALP in hFOB1.19 cells.

Effects of different NPP WSM

concentrations on cell mineralization

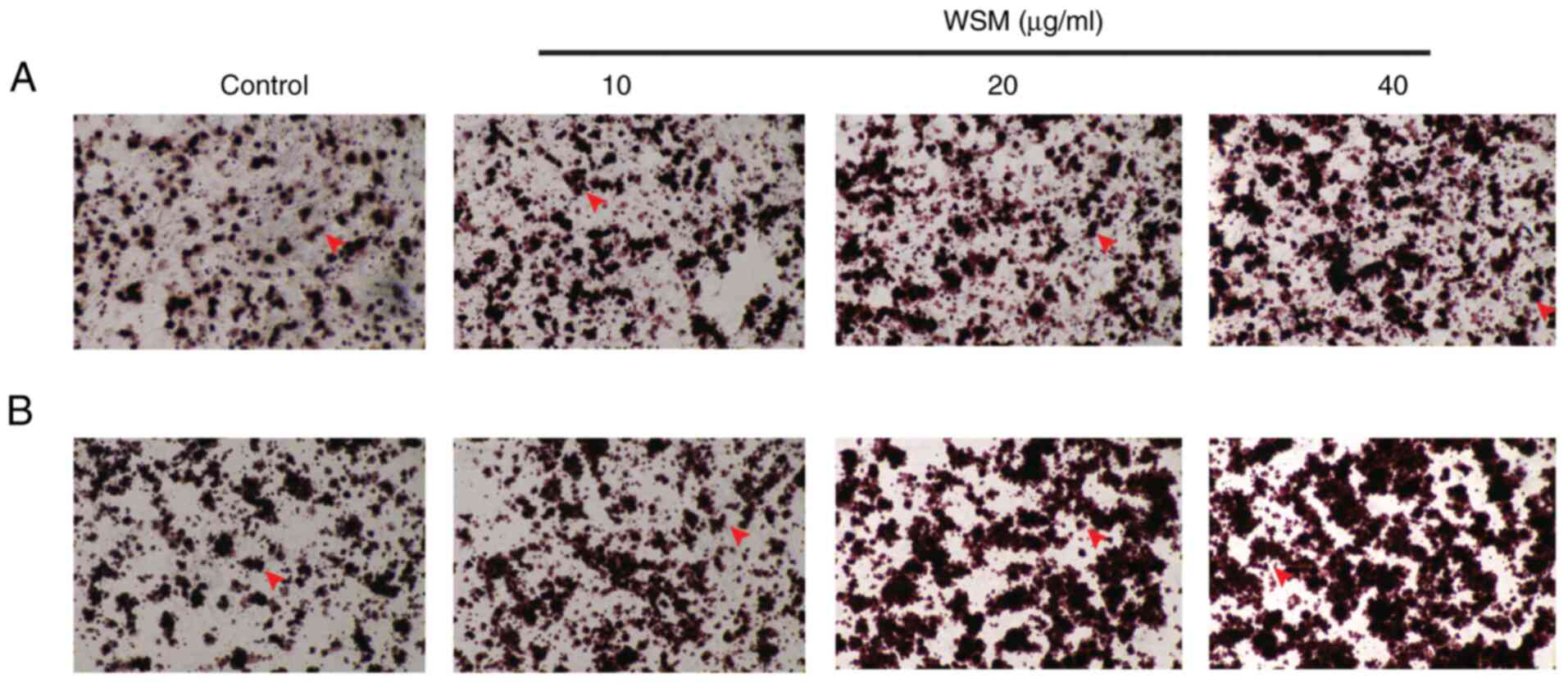

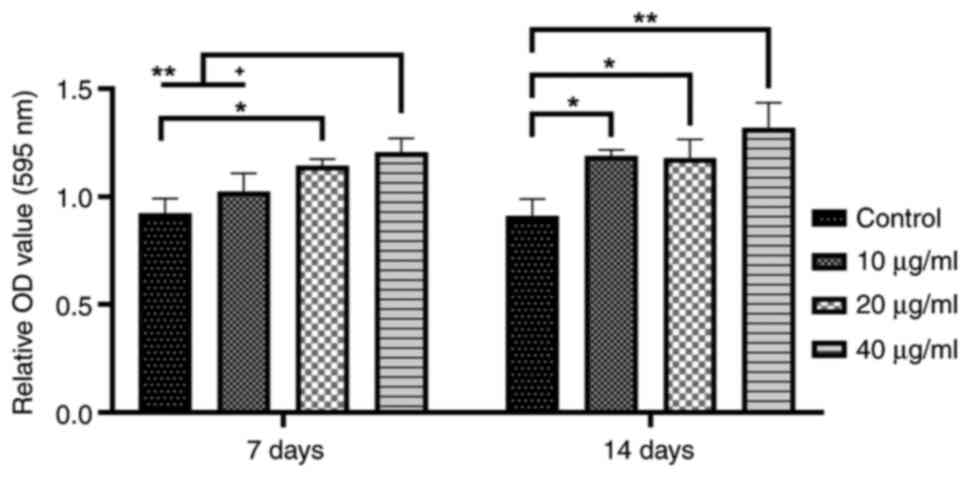

After 7 days of culture, mineralization in the 20

and 40 µg/ml WSM groups was found to be significantly increased

compared with that in the blank control group. Following a 14-day

culture, compared with that in the blank control group, the area of

mineralized nodules in the 10-40 µg/ml WSM groups was significantly

elevated, particularly in the 40 µg/ml WSM group. However, there

was no difference among the WSM treatment groups on day 14

(Figs. 2 and 3).

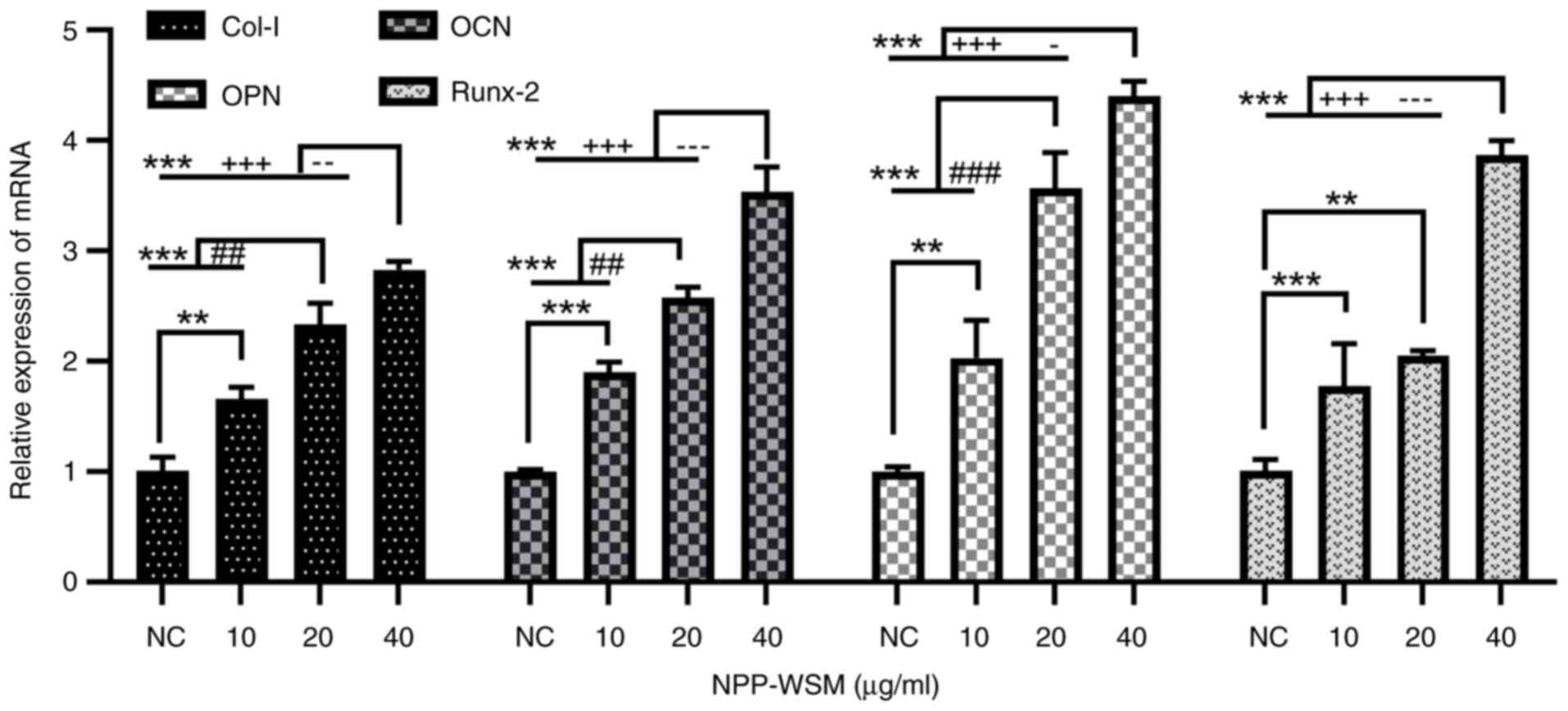

Effects of different NPP WSM

concentrations on osteogenic gene expression

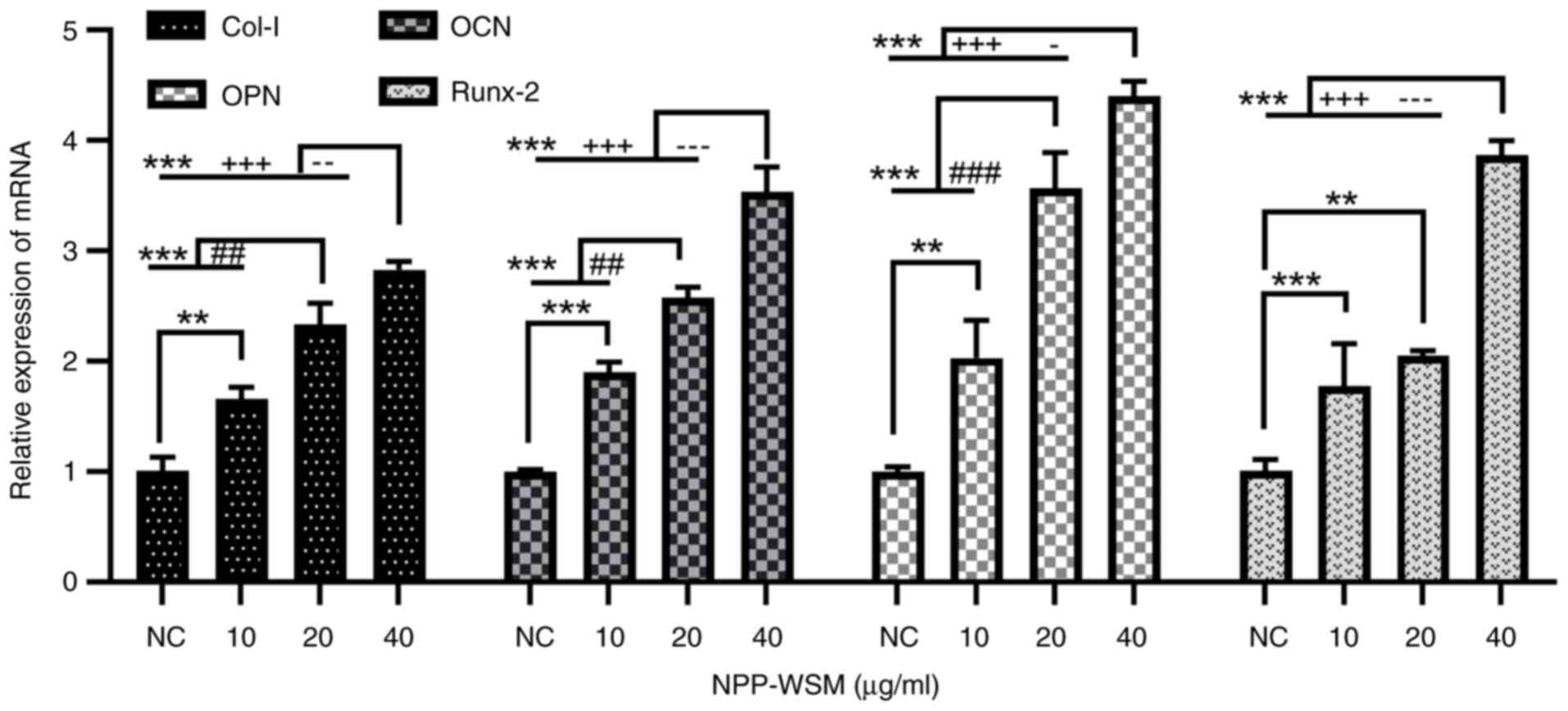

As shown in Fig. 4,

after 7 days of culture, the expression of target genes (Col-I,

OCN, OPN and Runx-2) in the 10-40 µg/ml WSM groups was found to be

significantly increased compared with that in the blank control

group. Additionally, the target gene mRNA levels in the 40 µg/ml

WSM group were significantly elevated compared with those in the 10

and 20 µg/ml WSM groups.

| Figure 4mRNA expression of osteogenic genes

in each WSM treatment group (0, 10, 20 and 40 µg/ml) measured

through reverse transcription-quantitative PCR. Data are presented

as the means ± standard deviation, n=4; **P<0.01 and

***P<0.001 (0 µg/ml vs. all other groups);

##P<0.01 and ###P<0.001 (10 vs. 20

µg/ml); -P<0.05, --P<0.01 and

---P<0.001 (20 vs. 40 µg/ml);

+++P<0.001 (10 vs. 40 µg/ml). WSM, water-soluble

matrix; Col-I, type I collagen; OCN, osteocalcin; OPN, osteopontin;

Runx-2, Runt-associated transcription factor 2; NC, negative

control. |

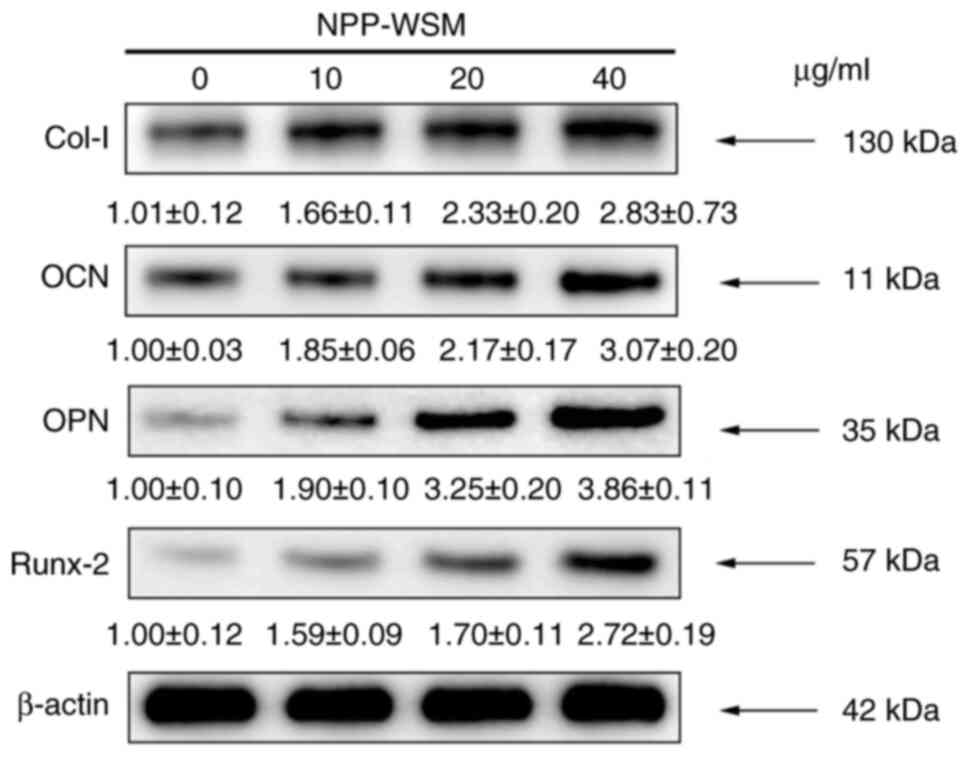

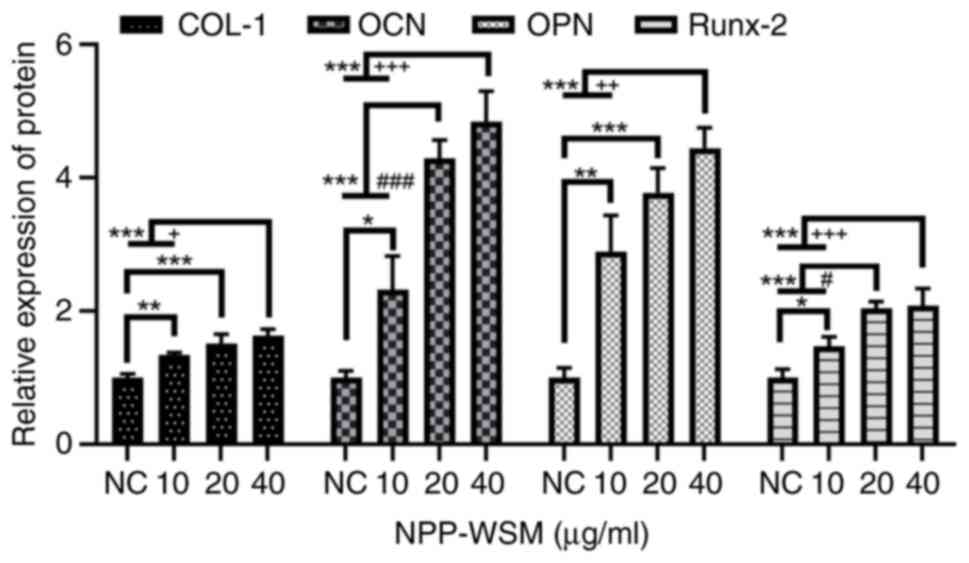

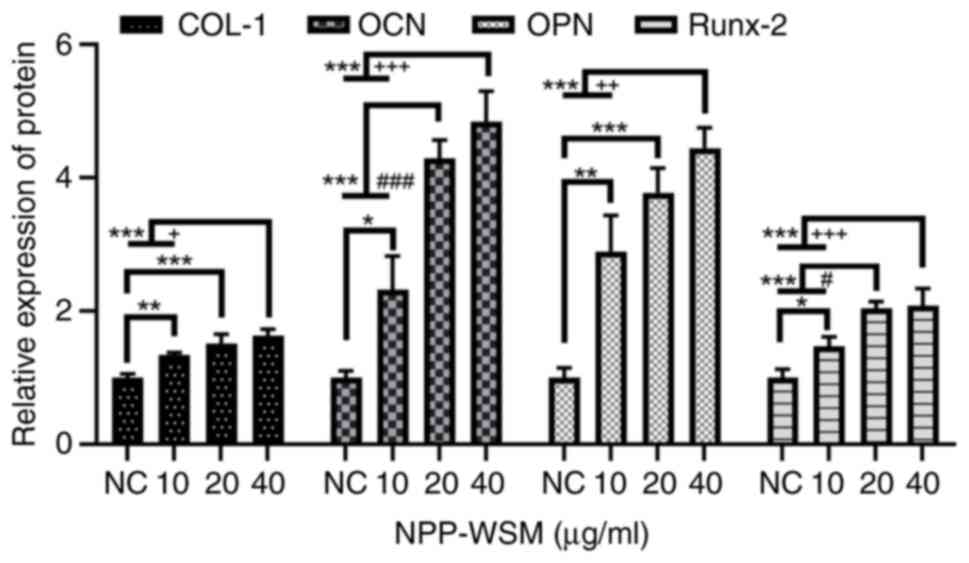

Effects of different NPP WSM

concentrations on osteogenic protein expression

As shown in Figs. 5

and 6, target protein (Col-I, OCN,

OPN and Runx-2) expression in the 10, 20 and 40 µg/ml WSM groups

was found to be increased following 7 days of culture compared with

that in blank control group. However, the protein expression level

in the 40 µg/ml group was not significantly different compared with

that in the 20 µg/ml group.

| Figure 6Osteogenic protein expression

detected in each group following WSM treatment (0, 10, 20 and 40

µg/ml) by western blotting. There were significant differences in

the expression of bone-related proteins following WSM treatment.

Data are presented as the means ± standard deviation, n=4.

*P<0.05, **P<0.01 and

***P<0.001 (0 µg/ml vs. all other groups);

#P<0.05 and ###P<0.001 (10 vs. 20

µg/ml); +P<0.05, ++P<0.01 and

+++P<0.001 (10 vs. 40 µg/ml). Col-I, type I collagen;

OCN, osteocalcin; OPN, osteopontin; Runx-2, Runt-associated

transcription factor 2; NC, negative control; WSM, water-soluble

matrix. |

Discussion

Remodeling of the bone tissue is regulated by a

variety of cytokines, where the key to maintaining the integrity of

bone tissue is to regulate the homeostasis between osteoblasts and

osteoclasts (24). Pro-osteoclast

cytokines include TNF-α and the IL family, whereas anti-osteoclast

cytokines mainly include IFN-α, IFN-β and IFN-γ (25). These aforementioned factors serve a

key role in osteoclast formation through the interaction between

the bone and the immune system (26). Lan et al (27) previously studied the regulatory

effect of hydrolyzed seawater pearl tablet (HSPT) on Th1/Th2

imbalance in immunosuppressed mice induced by cyclosporin A. The

results showed that the protein and mRNA expression levels of Th1

cytokines IL-2 and IFN-γ were increased in mice treated with HSPT.

HSPT may ameliorate Th1/Th2 imbalance under immunosuppressive

conditions by upregulating the expression of Th1 cytokines, IL-2

and IFN-γ. Future studies should further explore whether these

immunomodulatory effects indirectly influence bone metabolism or

the balance between osteoblast and osteoclast activity.

As a natural polymer, pearl powder is currently a

topic of intense research in the field of bone tissue engineering

(28-30).

The composition of pearl powder is similar to that of nacre powder

(31). Previous studies have shown

that pearl powder and artificial bone materials containing pearl

powder have osteogenic effects both in in vivo and in

vitro (32,33). However, the majority of recent

studies have focused on the osteogenic application of nacre powder

matrix (15,34), whilst to the best of our knowledge,

studies on the effect of pearl powder matrix on osteoblasts

remained scarce. The nacre organic matrix is a key substance in

regulating the mineralization of bivalve mollusks (1). The invertebrate mineralization

process and mammalian bone calcification have similar signaling

pathways where the signaling molecules have similar protein

domains. Previous studies have shown that the NPP organic matrix

can promote the differentiation of osteoblasts (35,36).

Pearl powder has also been shown to promote collagen production and

serve a role in wound healing following skin injuries (7,37).

In particular, pearl powder and composite materials constructed

with pearl powder have been documented to promote osteogenesis in a

variety of cell lines, such as mouse bone marrow MSCs (38) and rat bone MSCs (39).

Nanomaterials have properties that materials of

general size (>1 µm) do not have. Nano-treatment of pearl powder

or pearl layer powder not only retains the effective components of

pearl powder, but also results in an improved osteogenic effects

(40). A previous review examined

the effects of four inorganic or metallic nanoparticles widely used

as biomaterials, namely hydroxyapatite, silica, silver and calcium

carbonate, on the osteogenic and lipogenic differentiation of MSCs

(41). The size of the materials

can affect cell function, revealing that these materials have rich

application prospects on the nanoscale (41). There have been a number of studies

on the use of NPP and its scaffold materials. Chen et al

(7) previously found that NPP can

promote the proliferation and migration of skin cells, accelerate

wound healing and improve the biomechanical strength of healed skin

in both in vivo and in vitro experiments. In

addition, Yang et al (42)

constructed a NPP/poly (lactide-co-glycolide) biocomposite

scaffold, which promoted the uniform seeding, adhesion and

proliferation of MC3T3-E1 cells, which is a pre-osteoblastic cell

line derived from mouse calvaria, possessing osteogenic

differentiation potential. Therefore, NPP is relatively

reproducible and provides structural features that can enhance the

formation of bone tissues. A previous study also demonstrated that

scaffolds constructed with NPP had osteogenic effects (30).

The pearl powder matrix can be obtained according to

the different media, where the finished products are termed ‘WSM’,

‘water-insoluble matrix’ and ‘acid-soluble protein’ (31). WSM has a high water solubility and

can be widely used in cell assays and skin wound healing

experiments. The active ingredients of WSM are rapidly absorbed by

cells and skin, making it the pearl powder-related product that is

closest to clinical application (7,32,37,38,43).

Liu et al (44) previously

obtained the WSM of pearl powder using a CO2

supercritical extraction system, where the subsequent product was

found to promote the migration and proliferation of fibroblasts. In

rats with skin defects, 5 and 10 mg/ml WSM had a marked effect on

wound healing (the healing area of the wound was higher than that

in the control group), whilst 15 mg/ml had a poor effect (the wound

healing area was not as good as in other groups). It was speculated

that a high WSM concentration may have toxic effects on the skin,

since the Masson's staining of tissues has also shown abundant

collagen hyperplasia (38). In

another study, Dai et al (45) extracted the WSM from pearl powder

and further fractionated it into MR14 (>14 kDa), MR3-14 (3-14

kDa) and MR3 (<3 kDa) based on molecular weight. The authors

found that WSM and MR14 promoted proliferation, while all fractions

enhanced collagen deposition in primary oral fibroblasts from

BALB/c mice.

In a previous study, NPP WSM was found to enhance

autophagy in MC3T3-E1 cell lines to promote their differentiation

through the MEK/ERK signaling pathway (46). In the present study, NPP WSM was

applied to human cells. Specifically, NPP WSM was further applied

to hFOB1.19 cells, where the results demonstrated that there was no

significant difference in ALP activity among all experimental

groups after 1 day of incubation, which may be due to the

insufficient time allowed for osteoblast differentiation. On days 3

and 7, the ALP activity of the treated hFOB1.19 cells was

significantly enhanced, where the effect of WSM on the osteogenic

differentiation of hFOB1.19 cells on day 7 was stronger compared

with that on day 3. These results suggest that 10, 20 and 40 µg/ml

NPP WSM can promote the osteogenesis of hFOB1.19 cells. Col-I, OCN,

OPN and Runx-2 are biomarkers commonly used in biological

experiments and clinical examinations to reflect the effects of

bone formation (43). In the

present study, the expression levels of Col-I, OCN, OPN and Runx-2

were found to be significantly increased in hFOB1.19 cells treated

with NPP WSM, suggesting that NPP WSM may achieve osteogenic

effects by regulating the expression of these proteins. In two

other previous studies on skin wound healing, Col-I expression was

observed to be increased in mice fibroblasts treated with pearl

powder WSM (44,45), whereas in another previous study

Col-I and Runx-2 expression levels were also reported to be

increased in MC3T3-E1 cells treated with NPP WSM (46). These results are consistent with

those in the present study.

However, there are a number of limitations in the

present study. The signaling pathways associated with NPP WSM

osteogenesis were not investigated further. In addition, a positive

control group with a known substance that can definitively induce

osteogenesis was not included.

In conclusion, the results of the present study

suggest that NPP WSM may promote the osteogenic differentiation of

hFOB1.19 cells, by regulating the expression of the osteogenic

factors, Col-I, OCN, OPN and Runx-2, in a dose-dependent manner.

These results suggest that NPP WSM could be further explored in

future studies for its potential application in oral implants

addressing insufficient alveolar ridge bone mass. In follow-up

studies, a bone defect model in animals is required, with

implantation surgeries, to explore the effective concentration and

therapeutic effect of NPP WSM in vivo, with aims of eventual

clinical studies.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: The present study was funded by the China National

Natural Science Foundation Project (grant no. 82060194), Hainan

Province Key Research and Development Project (grant no.

ZDYF2022SHFZ119).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

The experiments were conceived and designed by LL

and PX. The experiments and analysis were performed by XX and LL.

The data were analyzed by WZ and LL. The manuscript was written and

revised by XX and PX. XX and PX confirm the authenticity of all the

raw data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Cuif JP, Dauphin Y, Luquet G, Medjoubi K,

Somogyi A and Perez-Huerta A: Revisiting the organic template model

through the microstructural study of shell development in Pinctada

margaritifera, the polynesian pearl oyster. Minerals.

8(370)2018.

|

|

2

|

Farre B, Brunelle A, Laprévote O, Cuif JP,

Williams CT and Dauphin Y: Shell layers of the black-lip pearl

oyster Pinctada margaritifera: Matching microstructure and

composition. Comp Biochem Physiol B Biochem Mol Biol. 159:131–139.

2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Ma Y, Qiao L and Feng Q: In-vitro study on

calcium carbonate crystal growth mediated by organic matrix

extracted from fresh water pearls. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl.

32:1963–1970. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Almeida MJ, Milet C, Peduzzi J, Pereira L,

Haigle J, Barthelemy M and Lopez E: Effect of water-soluble matrix

fraction extracted from the nacre of Pinctada maxima on the

alkaline phosphatase activity of cultured fibroblasts. J Exp Zool.

288:327–334. 2000.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Zhang J, Li S, Yao S, Si W, Cai L, Pan H,

Hou J, Yang W, Da J, Jiang B, et al: Ultra-performance liquid

chromatography of amino acids for the quality assessment of pearl

powder. J Sep Sci. 38:1552–1560. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Chiu HF, Hsiao SC, Lu YY, Han YC, Shen YC,

Venkatakrishnan K and Wang CK: Efficacy of protein rich pearl

powder on antioxidant status in a randomized placebo-controlled

trial. J Food Drug Anal. 26:309–317. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Chen X, Peng LH, Chee SS, Shan YH, Liang

WQ and Gao JQ: Nanoscaled pearl powder accelerates wound repair and

regeneration in vitro and in vivo. Drug Dev Ind Pharm.

45:1009–1016. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Zhang JX, Li SR, Yao S, Bi QR, Hou JJ, Cai

LY, Han SM, Wu WY and Guo DA: Anticonvulsant and sedative-hypnotic

activity screening of pearl and nacre (mother of pearl). J

Ethnopharmacol. 181:229–235. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Ansari N and Sims NA: The cells of bone

and their interactions. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 262:1–25.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Dai R, Liu M, Xiang X, Xi Z and Xu H:

Osteoblasts and osteoclasts: An important switch of tumour cell

dormancy during bone metastasis. J Exp Clin Cancer Res.

41(316)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Jurisic V, Terzic T, Pavlovic S, Colovic N

and Colovic M: Elevated TNF-alpha and LDH without parathormone

disturbance is associated with diffuse osteolytic lesions in

leukemic transformation of myelofibrosis. Pathol Res Pract.

204:129–132. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Yao Z, Getting SJ and Locke IC: Regulation

of TNF-induced osteoclast differentiation. Cells.

11(132)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Akdis M, Aab A, Altunbulakli C, Azkur K,

Costa RA, Crameri R, Duan S, Eiwegger T, Eljaszewicz A, Ferstl R,

et al: Interleukins (from IL-1 to IL-38), interferons, transforming

growth factor β, and TNF-α: Receptors, functions, and roles in

diseases. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 138:984–1010. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Zhao Y, Sun Q and Huo B: Focal adhesion

regulates osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells and

osteoblasts. Biomater Transl. 2:312–322. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Nahle S, Lutet-Toti C, Namikawa Y, Piet

MH, Brion A, Peyroche S, Suzuki M, Marin F and Rousseau M: Organic

matrices of calcium carbonate biominerals improve osteoblastic

mineralization. Mar Biotechnol (NY). 26:539–549. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Jin C, Zhao JY, Liu XJ and Li JL:

Expressions of shell matrix protein genes in the pearl sac and its

correlation with pearl weight in the first 6 months of pearl

formation in Hyriopsis cumingii. Mar Biotechnol (NY). 21:240–249.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Commission CP and Commission SP:

Pharmacopoeia of the people's Republic of China 2015. (No Title),

2015.

|

|

18

|

Huang F, Deng CM and Fu Z: GC-MS

determination of microamounts of organic chemical compositions in

nacre powder of Hyriopsis cumingii Lea. Phs Test Chem Anal.

46:300–302. 2010.

|

|

19

|

He JF, Deng Q, Pu YH, Liao B and Zeng M:

Amino acids composition analysis of pearl powder and pearl layer

powder. Food Ind. 37:270–273. 2016.

|

|

20

|

Berland S, Ma Y, Marie A, Andrieu JP,

Bedouet L and Feng Q: Proteomic and profile analysis of the

proteins laced with aragonite and vaterite in the freshwater mussel

Hyriopsis cumingii shell biominerals. Protein Pept Lett.

20:1170–1180. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Green DW, Kwon HJ and Jung HS: Osteogenic

potency of nacre on human mesenchymal stem cells. Mol Cells.

38:267–272. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408.

2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Jurisic V, Srdic-Rajic T, Konjevic G,

Bogdanovic G and Colic M: TNF-α induced apoptosis is accompanied

with rapid CD30 and slower CD45 shedding from K-562 cells. J Membr

Biol. 239:115–122. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Kim JM, Lin C, Stavre Z, Greenblatt MB and

Shim JH: Osteoblast-osteoclast communication and bone homeostasis.

Cells. 9(2073)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Li S, Liu G and Hu S: Osteoporosis:

Interferon-gamma-mediated bone remodeling in osteoimmunology. Front

Immunol. 15(1396122)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Jurisic V: Multiomic analysis of cytokines

in immuno-oncology. Expert Rev Proteomics. 17:663–674.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Lan TJ, Luo X, Mo MY, Chen ZX, Luo F, Han

SY, Liu P, Liang ZX, Zhang T, Li TY, et al: Hydrolyzed seawater

pearl tablet modulates the immunity via attenuating Th1/Th2

imbalance in an immunosuppressed mouse model. J Tradit Chin Med.

41:397–405. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Loh XJ, Young DJ, Guo H, Tang L, Wu Y,

Zhang G, Tang C and Ruan H: Pearl powder-an emerging material for

biomedical applications: A review. Materials (Basel).

14(2797)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Luo W, Chen Y, Chen C and Ren G: The

proteomics of the freshwater pearl powder: Insights from

biomineralization to biomedical application. J Proteomics.

265(104665)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Zhang W, Xu P, Cheng Y, Yang Y, Mao Q and

Chen Z: Preparation of a nanopearl powder/C-HA (chitosan-hyaluronic

acid)/rhBMP-2 (recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2)

composite artificial bone material and a preliminary study of its

effects on MC3T3-E1 cells. Bioengineered. 13:14368–14381.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Pei J, Wang Y, Zou X, Ruan H, Tang C, Liao

J, Si G and Sun P: Extraction, purification, bioactivities and

application of matrix proteins from pearl powder and nacre powder:

A review. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 9(649665)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Li X, Xu P, Cheng Y, Zhang W, Zheng B and

Wang Q: Nano-pearl powder/chitosan-hyaluronic acid porous composite

scaffold and preliminary study of its osteogenesis mechanism. Mater

Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 111(110749)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Zhang X, Du X, Li D, Ao R and Yu B and Yu

B: Three dimensionally printed pearl powder/poly-caprolactone

composite scaffolds for bone regeneration. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed.

29:1686–1700. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Li SG, Guo ZL, Tao SY, Han T, Zhou J, Lin

WY, Guo X, Li CX, Diwas S and Hu XW: In vivo study on osteogenic

efficiency of nHA/gel porous scaffold with nacre water-soluble

matrix. Tissue Cell. 88(102347)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

de Muizon CJ, Iandolo D, Nguyen DK,

Al-Mourabit A and Rousseau M: Organic matrix and secondary

metabolites in nacre. Mar Biotechnol (NY). 24:831–842.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Evans JS: The biomineralization proteome:

Protein complexity for a complex bioceramic assembly process.

Proteomics. 19(e1900036)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Han S, Huang D, Lan T, Wu Y, Wang Y, Wei

J, Zhang W, Ou Y, Yan Q, Liu P, et al: Therapeutic effect of

seawater pearl powder on UV-induced photoaging in mouse skin. Evid

Based Complement Alternat Med. 2021(9516427)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Wu Y, Ding Z, Ren H, Ji M and Yan Y:

Preparation, characterization and in vitro biological evaluation of

a novel pearl powder/poly-amino acid composite as a potential

substitute for bone repair and reconstruction. Polymers (Basel).

11(831)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Du X, Yu B, Pei P, Ding H, Yu B and Zhu Y:

3D printing of pearl/CaSO4 composite scaffolds for bone

regeneration. J Mater Chem B. 6:499–509. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Qiu-Hua M and Pu X: Research progress of

pearl/nacer in bone tissue repair. J Oral Sci Res. 32:311–333.

2016.

|

|

41

|

Yang X, Li Y, Liu X, He W, Huang Q and

Feng Q: Nanoparticles and their effects on differentiation of

mesenchymal stem cells. Biomater Transl. 1:58–68. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Yang YL, Chang CH, Huang CC, Kao WMW, Liu

WC and Liu HW: Osteogenic activity of nanonized pearl powder/poly

(lactide-co-glycolide) composite scaffolds for bone tissue

engineering. Biomed Mater Eng. 24:979–985. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Rico-Llanos GA, Borrego-González S,

Moncayo-Donoso M, Becerra J and Visser R: Collagen type I

biomaterials as scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Polymers

(Basel). 13(588)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Liu M, Tao J, Guo H, Tang L, Zhang G, Tang

C, Zhou H, Wu Y, Ruan H and Loh XJ: Efficacy of water-soluble pearl

powder components extracted by a CO2 supercritical

extraction system in promoting wound healing. Materials (Basel).

14(4458)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Dai J.P, Chen J, Bei Y.F, Han B.X, Guo S.B

and Jiang L.L: Effects of pearl powder extract and its fractions on

fibroblast function relevant to wound repair. Pharm Biol.

48:122–127. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Cheng Y, Zhang W, Fan H and Xu P:

Water-soluble nano-pearl powder promotes MC3T3-E1 cell

differentiation by enhancing autophagy via the MEK/ERK signaling

pathway. Mol Med Rep. 18:993–1000. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|