Introduction

Perivascular epithelioid cell tumors (PEComas) are a

rare group of mesenchymal neoplasms characterized by distinctive

histological and immunohistochemical features. This tumor family

was first described by Bonetti et al (1) in 1992, initially encompassing renal

angiomyolipoma and the clear cell ‘sugar’ tumor of the lung.

Subsequently, additional neoplasms were incorporated

into the PEComa family based on their characteristic co-expression

of melanocytic markers (HMB-45, Melan-A) and smooth muscle markers

(SMA), including lymphangioleiomyomatosis (2). The same research group later expanded

the category to include clear cell myomelanocytic tumors of the

falciform ligament (ligamentum teres) and other clear cell tumors

across multiple organs (3), such

as the urinary bladder, prostate, uterus, ovary, vulva, vagina,

lung, pancreas and liver (hepatic angiomyolipoma). Molecular

studies have established a strong link between PEComas and the

tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC), an autosomal dominant disorder

caused by mutations or deletions of the TSC1 (9q34) or TSC2

(16p13.3) genes (4,5). Clinically, TSC is associated with

intellectual disability, seizures, and various neoplasms, including

angiomyolipomas, subependymal giant cell astrocytomas, cutaneous

angiofibromas, cardiac rhabdomyomas, lymphangioleiomyomatosis, and

multifocal micronodular pneumocyte hyperplasia. Further research

has demonstrated that TSC1/TSC2 loss results in activation of

Rheb/mTOR/p70S6K signaling pathway, a key driver of tumorigenesis

in PEComas and the biological rationale for the use of mTOR

inhibitors in selected cases (6-8).

It is noteworthy, however, that PEComas do not occur more

frequently in patients with clinical TSC. Instead, most PEComas

harbor somatic mutations in TSC1 or, more commonly, TSC2 without

affected individuals meeting the diagnostic criteria for systemic

TSC. This distinction highlights the role of TSC gene alterations

as driver mutation in PEComa tumorigenesis, rather than as

manifestations of germline disease.

In 2005, Folpe et al (9) reported on 26 cases of soft tissue and

gynecologic PEComas, have proposed histological criteria for risk

classification into benign, uncertain malignant potential, and

malignant categories. Parameters associated with aggressive

behavior include tumor size >5 cm, infiltrative growth, high

nuclear grade, necrosis, and mitotic activity >1/50 high-power

fields. Surgical excision remains the standard treatment,

particularly for tumors with high-risk features.

Yamasaki et al (10) have reported the first description

of hepatic PEComa. in 2000. Since then, additional reports,

including malignant variants, have been described, with a total of

224 primary hepatic PEComas described across 75 publications

(11,12).

Here, we present an unusual case of hepatic PEComa

diagnosed in the hepatobiliary surgery center of the University

Hospital Münster, Germany. With a particular focus on

histopathological evaluation, this case highlights the importance

of distinguishing PEComas from morphologically overlapping hepatic

neoplasms, particularly hepatocellular carcinoma, in order to

ensure accurate diagnosis and appropriate treatment.

Case report

A 43-year-old man with no known comorbidities and in

good health (height: 188 cm, weight: 75 kg, BMI: 21.2 kg/m²)

presented with abdominal discomfort and right upper quadrant

tenderness. Initial laboratory tests were unremarkable. The

alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) was within the reference range (2.4 ng/ml;

reference <7 ng/ml). During admission, fluctuating elevations of

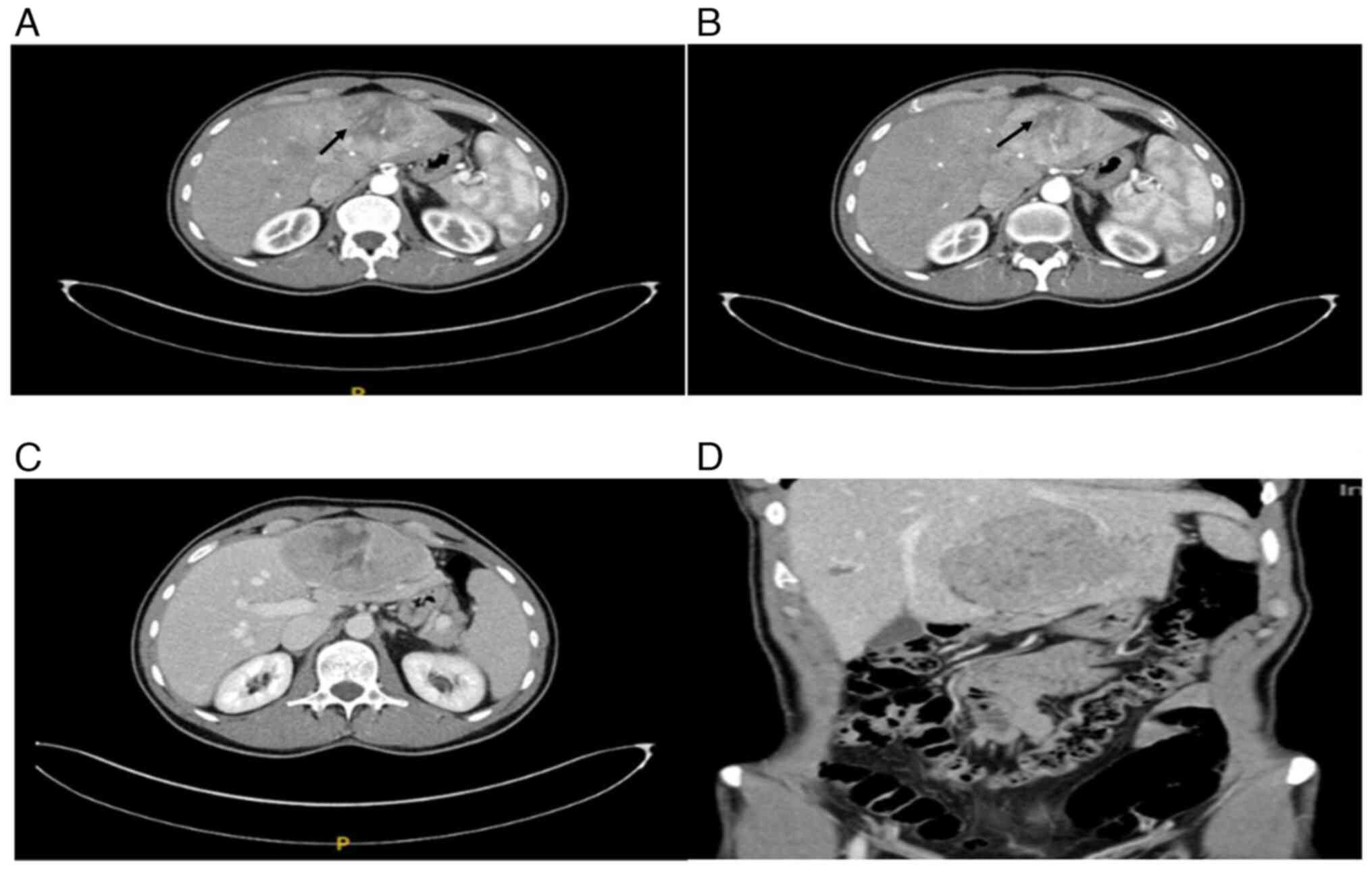

GPT and GOT were noted. Dynamic contrast-enhanced CT multi-slice

(MSCT) revealed a large tumor in the hepatic left lobe measuring

11.6x10.3x6.8 cm (Fig. 1A-D). The

lesion was inhomogeneous, peripherally hypervascular, and showed

partial washout in the portal venous phase. Based on imaging, a

liver adenoma was suspected, and the interdisciplinary tumor board

recommended resection.

The patient underwent robotic-assisted left

hemihepatectomy. Postoperative recovery was uneventful, and he was

discharged on day 5 with negative resection margins.

Gross pathology revealed a liver specimen weighing

604 g containing a lobulated, heterogeneous, pseudocapsulated tumor

measuring 12x8x5.5 cm, located 2 mm from the resection margin

(Fig. 2).

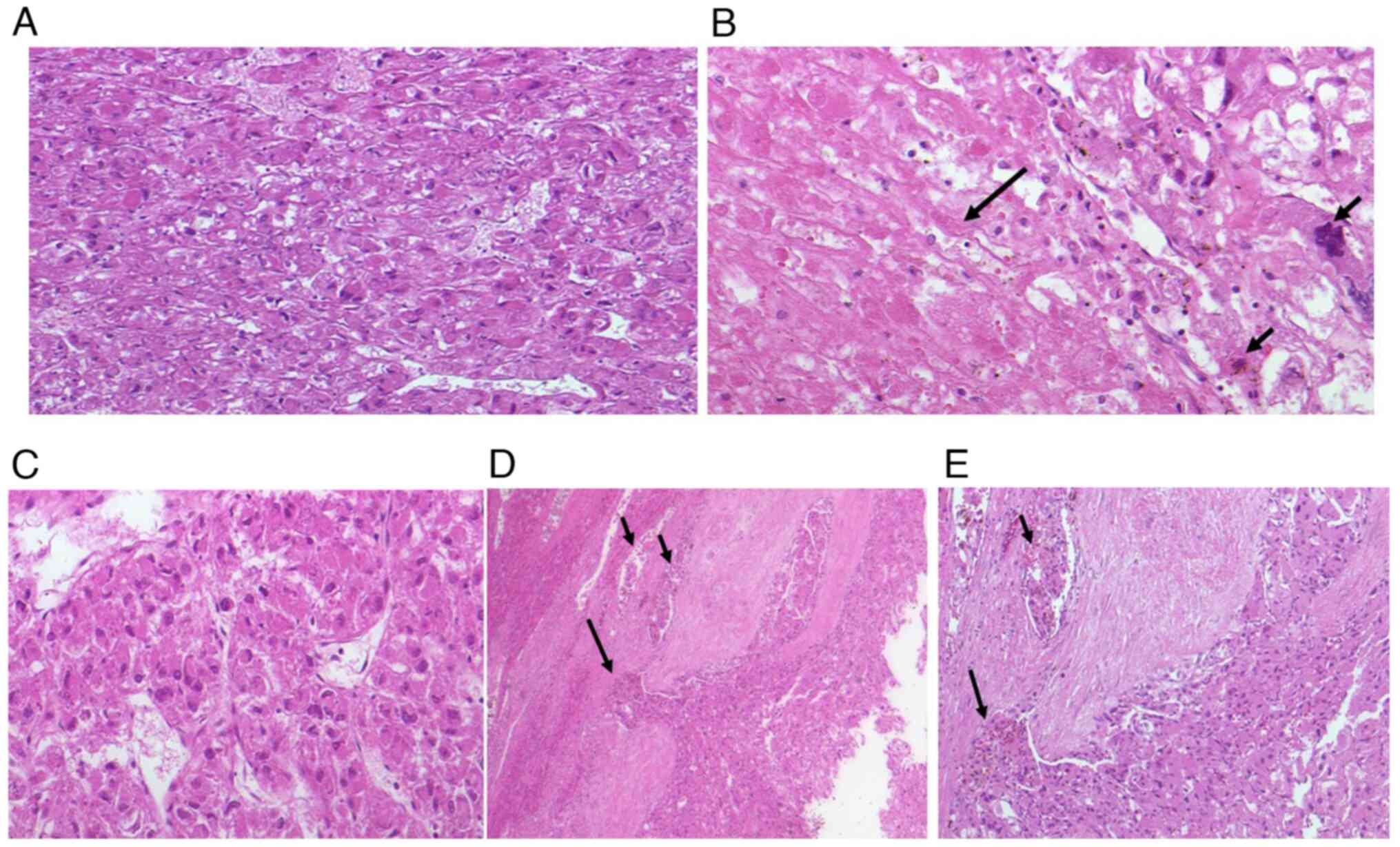

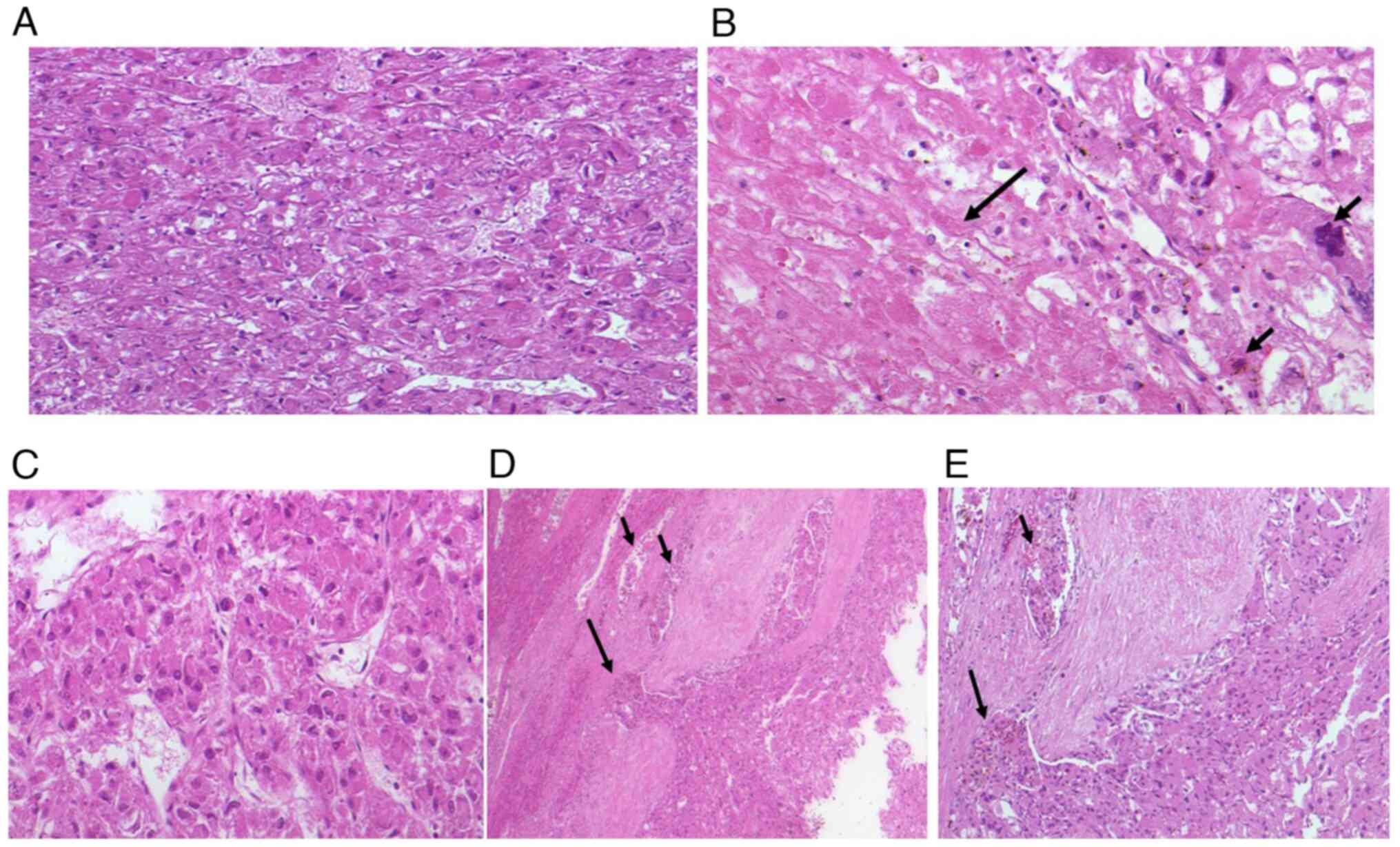

Microscopy (Fig.

3A-E) showed epithelioid, polyhedral cells with central to

eccentric nuclei and abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm, arranged in

nests and separated by a delicate capillary network. Central

necrosis (Fig. 3B; arrow) was

present, and, at the periphery, the tumor infiltrated its

pseudocapsule with vascular invasion (Fig. 3D and E; arrow). Nuclei displayed irregular

contours with focal nucleolar prominence, and the mitotic rate was

up to 6/10 HPF. Based on these features and the epithelioid

morphology, the initial histopathological differential diagnosis

was moderately differentiated hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

| Figure 3(A) Microscopic examination showed

epithelioid, polyhedral tumor cells with central to eccentric

nuclei and abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm, arranged in nests and

separated by a delicate capillary network (H&E staining;

magnification, x20). (B) Central necrosis (long arrow) was present.

Nuclei displayed irregular contours with focal nucleolar prominence

and abnormal mitotic figures (short arrow) (H&E staining;

magnification, x20). (C) Microscopic examination revealed

polyhedral epithelioid tumor cells with centrally to eccentrically

located nuclei and abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm. The cells were

arranged in trabeculae, separated by a fine capillary network

(H&E staining; magnification, x20). (D) Microscopic examination

demonstrated tumor cell infiltration into blood vessels and

capillaries (short arrow) as well as penetration of the

pseudocapsule (long arrow) (H&E staining; magnification, x10).

(E) At higher magnification, peripheral tumor infiltration was

evident, with the long arrow indicating pseudocapsule penetration

and the short arrow indicating vascular invasion (H&E staining;

magnification, x20). |

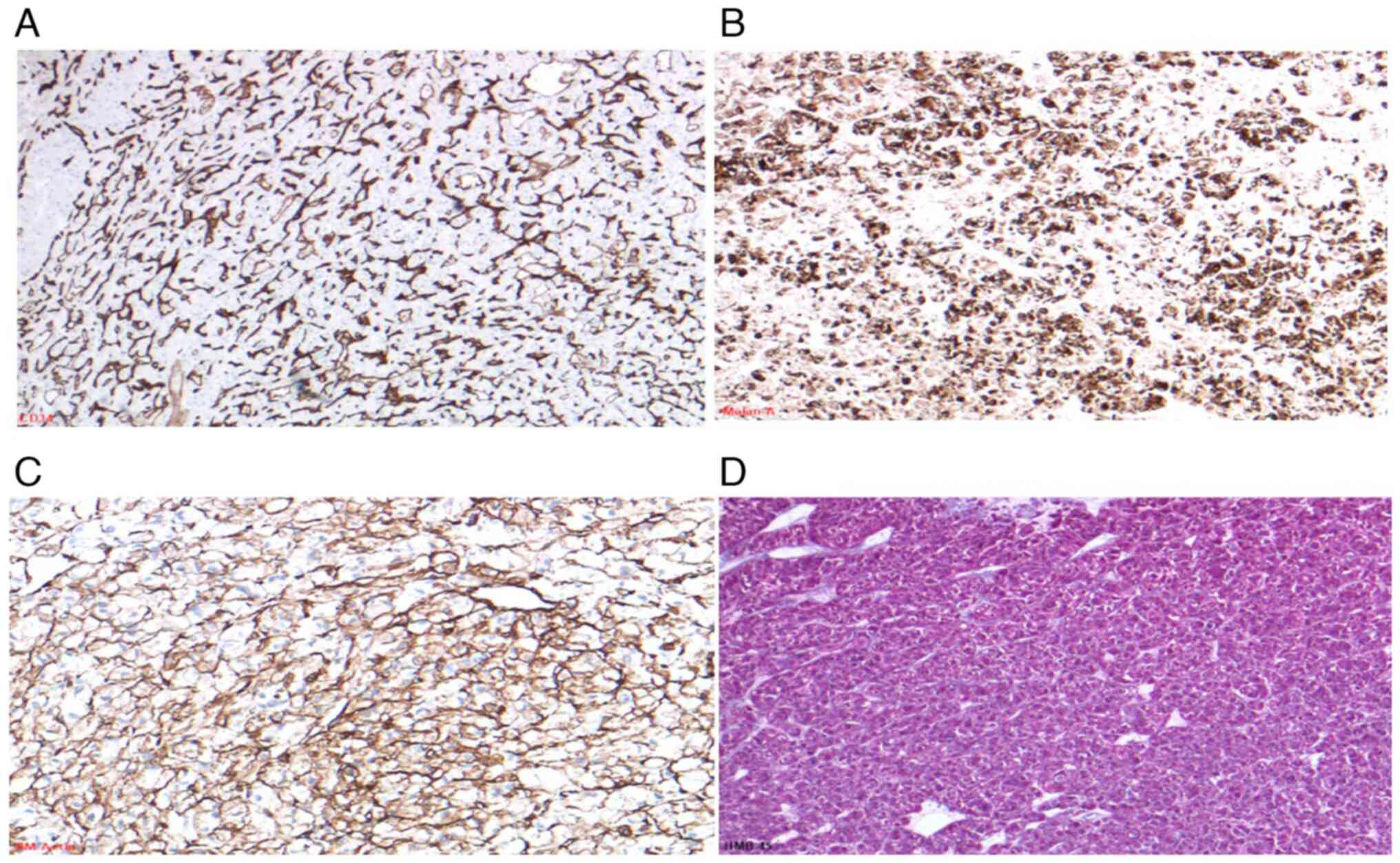

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) demonstrated complete

negative for HepPar-1, Arginase-1, Glypican-3, and Glutamine

Synthetase. HSP-70 showed weak, non-specific positivity. The Ki-67

proliferation index was <5% and CD34 staining highlighted the

peritumoral capillary network.

To refine these unexpected findings, an extended IHC

panel was applied. The tumor was negative for β-catenin, Serum

Amyloid A (SAA), L-FABP, CD10, CK7, CK20, and pancytokeratin,

effectively excluding HCC and hepatocellular adenoma. Further

testing revealed no expression of SOX10, S100, PAX8, Chromogranin

A, Vimentin, CD117 (c-Kit), Desmin, H-Caldesmon, Myogenin, MyoD1,

OCT-4, and SALL4. BRG1 and INI-1 expression were preserved.

Notably, tumor cells showed strong, diffuse expression of Melan-A

and HMB-45, with focal weak positivity for SMA (Fig. 4A-D), consistent with a perivascular

epithelioid cell tumor (PEComa).

Molecular analysis supported this diagnosis. NGS

revealed truncating mutations in exons 10 and 27 of the TSC2 gene

(Table I). FISH analysis excluded

a TFE3 rearrangement at Xp11.23, ruling out TFE3-associated

PEComa.

| Table IDetected mutations. |

Table I

Detected mutations.

| Gene | Reference

sequences | Exon | Alteration

(interpretation) | AF, % | Database ID |

|---|

| TSC1

(HGNC:12362) |

NM_000368/NP_000359 | -/- | -/- | -/- | -/- |

| TSC2

(HGNC:12363) |

NM_000548/NP_000539 | 10 | c.913G>T; p.

Gly305* (likely loss of function, likely pathogenic) | 11,3 | ClinVar: n.a. |

| TSC2

(HGNC:12363) |

NM_000548/NP_000539 | 27 | c.3093dup; p.

Arg1032Serfs*13 (likely loss of function, likely pathogenic) | 13,3 | ClinVar: 2910389 |

The final pathology report summarized the

histological and molecular features, highlighting adverse

prognostic indicators: large tumor size, infiltrative growth,

necrosis, and mitotic activity (7). The case was reviewed at the

multidisciplinary tumor board, and close clinical follow-up was

recommended. The patient has been treated surgically to date, and

follow-up was recommended. The most recent whole-body imaging,

performed five months after the left hemihepatectomy, showed no

metastases or residual lesions.

The Ethics Committee of University Hospital Münster

(Approval No. 2019-636-f-S) approves this case.

Discussion

Most hepatic PEComas reported to date are benign.

However, histological and clinical features predictive of

aggressive behavior have been defined. Yoo et al (12) have identified ‘worrisome features’,

including tumor size ≥7 cm, infiltrative borders, mitotic activity

>1/10 mm², necrosis, vascular invasion, and classification as

PEComa not otherwise specified (NOS). Risk stratification is based

on these features: high-risk if ≥3 are present, intermediate-risk

if 1-2 are present, and low-risk if none are identified. In the

present case, multiple adverse features indicated high-risk

disease.

Molecular findings further supported this

assessment. The identified truncating mutations in TSC2 are

typically loss-of-function variants that drive mTOR pathway

activation and are more frequently associated with aggressive

clinical behavior, whereas missense variants may have variable

consequences depending on their functional domains. Pan et

al (7) have demonstrated that

TSC2 alterations correlate with poor prognosis, highlighting the

biological relevance of mutation type.

Despite their malignant potential, PEComas generally

have a low recurrence (3.1%) and metastasis rate (2.7%), as

reported by Kvietkauskas et al (13). Complete surgical resection with

negative margins remains the standard treatment. In selected cases,

neoadjuvant mTOR inhibitors have been shown to reduce tumor size

and resection without complications (14).

Histological subtypes may also guide diagnostic

interpretation. Bennett et al (15) have emphasized that epithelioid

PEComas, such as in our patient, often lack strong smooth muscle

marker expression, in contrast to spindle cell-dominant PEComas,

which generally stain strongly positive. Recognition of this

pattern is essential to avoid misdiagnosis.

In summary, we report a rare case of hepatic PEComa

with multiple high-risk features and pathogenic TSC2 mutations.

This underscores the importance of a thorough immunohistochemical

and molecular workup in epithelioid liver tumors to differentiate

PEComa from morphologically similar entities such as hepatocellular

carcinoma Awareness of this diagnostic pitfall is crucial for

pathologists and clinicians to ensure accurate diagnosis,

appropriate patient management, and optimal therapeutic

decision-making.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr Kim Falkenberg

(Gerhard-Domagk-Institute of Pathology and Cytology, University

Hospital Muenster, D-48149 Muenster, Germany) for processing the

next-generation sequencing analysis, interpreting the results and

providing the data link, and Mrs. Petra Abbas (Muenster, Germany)

for proofreading.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The next-generation sequencing data generated in the

present study may be found in the Sequence Read Archive database

under accession number PRJNA1332571 or at the following URL:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/PRJNA1332571. The

other data generated in the present study are not publicly

available due to data privacy and protection regulations but may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

MA was involved in detection and diagnosis of the

rare case, performance and analysis of immunohistochemistry and

molecular pathology, development of the study concept, and

manuscript writing and final proofreading. BS participated in the

surgical procedure, was involved in case discussion, and critically

reviewed and proofread the manuscript, including validation of the

overall concept. MHM was involved in case discussion, patient

follow-up and proofreading of the manuscript. AP was involved in

case discussion, and critical review and reading of the manuscript,

with validation of the study concept. WH was involved in detection

and diagnosis of the rare case, contributed to the study concept,

analyzed immunohistochemistry and molecular pathology data, and

proofread the manuscript. EW was involved in detection and

diagnosis of the rare case, contributed to the study concept,

analyzed immunohistochemistry and molecular pathology data, and

proofread the manuscript. MA and WH confirm the authenticity of all

the raw data. All authors have read and approved the final version

of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The Ethics Committee of University Hospital Münster

(approval no. 2019-636-f-S; Muenster, Germany) approved this

case.

Patient consent for publication

The patient provided written consent for

publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Bonetti F, Pea M, Martignoni G and Zamboni

G: PEC and sugar. Am J Surg Pathol. 16:307–308. 1992.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Pea M, Martignoni G, Zamboni G and Bonetti

F: Perivascular epithelioid cell. Am J Surg Pathol. 20:1149–1153.

1996.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Martignoni G, Pea M, Reghellin D, Zamboni

G and Bonetti F: PEComas: The past, the present and the future.

Virchows Arch. 452:119–132. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

European Chromosome 16 Tuberous Sclerosis

Consortium. Identification and characterization of the tuberous

sclerosis gene on chromosome 16. Cell. 75:1305–1315.

1993.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

van Slegtenhorst M, de Hoogt R, Hermans C,

Nellist M, Janssen B, Verhoef S, Lindhout D, van den Ouweland A,

Halley D, Young J, et al: Identification of the tuberous sclerosis

gene TSC1 on chromosome 9q34. Science. 277:805–808. 1997.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Kwiatkowski DJ: Tuberous sclerosis: From

tubers to mTOR. Ann Hum Genet. 67:87–96. 2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Pan CC, Chung MY, Ng KF, Liu CY and Wang

JS: (2012). Constant allelic alteration of the TSC2 gene in

PEComas: A genetic hallmark? Modern Pathology, 25(3), 393–398.

|

|

8

|

Kenerson H, Folpe AL, Takayama TK and

Yeung RS: Activation of the mTOR pathway in sporadic PEComas.

Journal of Pathology. 211:445–453. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Folpe AL, Mentzel T, Lehr HA, Fisher C,

Balzer BL and Weiss SW: Perivascular epitheliod cell neoplasms of

soft tissue and gynecologic origin: A clinicopathologic study of 26

cases and review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol. 29:1558–1575.

2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Yamasaki S, Tanaka S, Fujii H, Matsumoto

T, Okuda C, Watanabe G and Suda K: Monotypic epithelioid

angiomyolipoma of the liver. Histopathology. 36:451–456.

2000.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Fang SH, Zhou LN, Jin M and Hu JB:

Perivascular epithelioid cell tumor of the liver: A report of two

cases and review of the literature. World J Gastroenterol.

13:5537–5539. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Yoo Y, Kim J and Song IH: Risk prediction

criteria for the primary hepatic perivascular epithelioid cell

tumour family, including angiomyolipoma: Analysis of 132 cases with

a literature review. Histopathology. 86:979–992. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Kvietkauskas M, Samuolyte A, Rackauskas R,

Luksaite-Lukste R, Karaliute G, Maskoliunaite V, Valkiuniene RB,

Sokolovas V and Strupas K: Primary liver perivascular epithelioid

cell tumor (PEComa): Case report and literature review. Medicina

(Kaunas). 60(409)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Bergamo F, Maruzzo M, Basso U, Montesco

MC, Zagonel V, Gringeri E and Cillo U: Neoadjuvant sirolimus for a

large hepatic perivascular epithelioid cell tumor (PEComa). World J

Surg Oncol. 12(46)2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Bennett JA, Braga AC, Pinto A, Van de

Vijver K, Cornejo K, Pesci A, Zhang L, Morales-Oyarvide V, Kiyokawa

T, Zannoni GF, et al: Uterine PEComas: A morphologic,

immunohistochemical, and molecular analysis of 32 tumors. Am J Surg

Pathol. 42:1370–1383. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|