Introduction

Distal radius fractures (DRFs) are one of the most

common fractures, accounting for ~18% of fractures in older adult

patients (1). Surgical treatments

for DRFs often achieve good reduction, but the incidence of

reduction loss due to osteoporosis and comminution is as high as

30%, especially for radial height loss (RHL) (2). Currently, there is no consensus

regarding the prevention of RHL.

Previous studies have confirmed that the normal

distal radius of the wrist can withstand an axial load of up to 80%

(3). RHL often occurs due to

insufficient radial support against the axial load, especially in

non-surgical treatments. RHL may also be observed in patients

undergoing open reduction and internal fixation with a volar

locking plate for intra- and extra-articular DRF. Figl et al

(4) found the incidence of RHL was

25% with a mean radial shortening of 1.8 mm (range, 1-3 mm) 1 year

after surgery. As a result, the mean extension-flexion movement and

grip strength were reduced by 21 and 35%, respectively. As for risk

factors for RHL, LaMartina et al (5) suggested that these include advanced

age, poor bone quality, short distance between fracture site and

articular surface, and postoperative ulnar-positive deformity. An

external fixator combined with open reduction and volar plating can

effectively prevent the RHL in older patients with comminuted DRF

compared with volar plating alone, as reported by Han et al

(6). Furthermore, Ruch et

al (7) reported effective

maintenance of RHL using a cross-wrist supporting plate; however,

the disadvantages include creating a dorsal incision and breaking

the blood supply to the fractured end. Therefore, this technique is

used less than the conventional external fixation (8). As an alternative method to treat RHL,

Kulshrestha et al (9)

suggested the bridging external fixation (BEF) for 6 to 8 weeks;

this technique uses a bridging external fixator that spans the

wrist. However, this technique is insufficient in older patients

with comminuted DRF. Non-BEFs often yield instability as only one

or two screws capture the fragments. To reinforce the stability of

distal fragments, combined external fixation (CEF), combining both

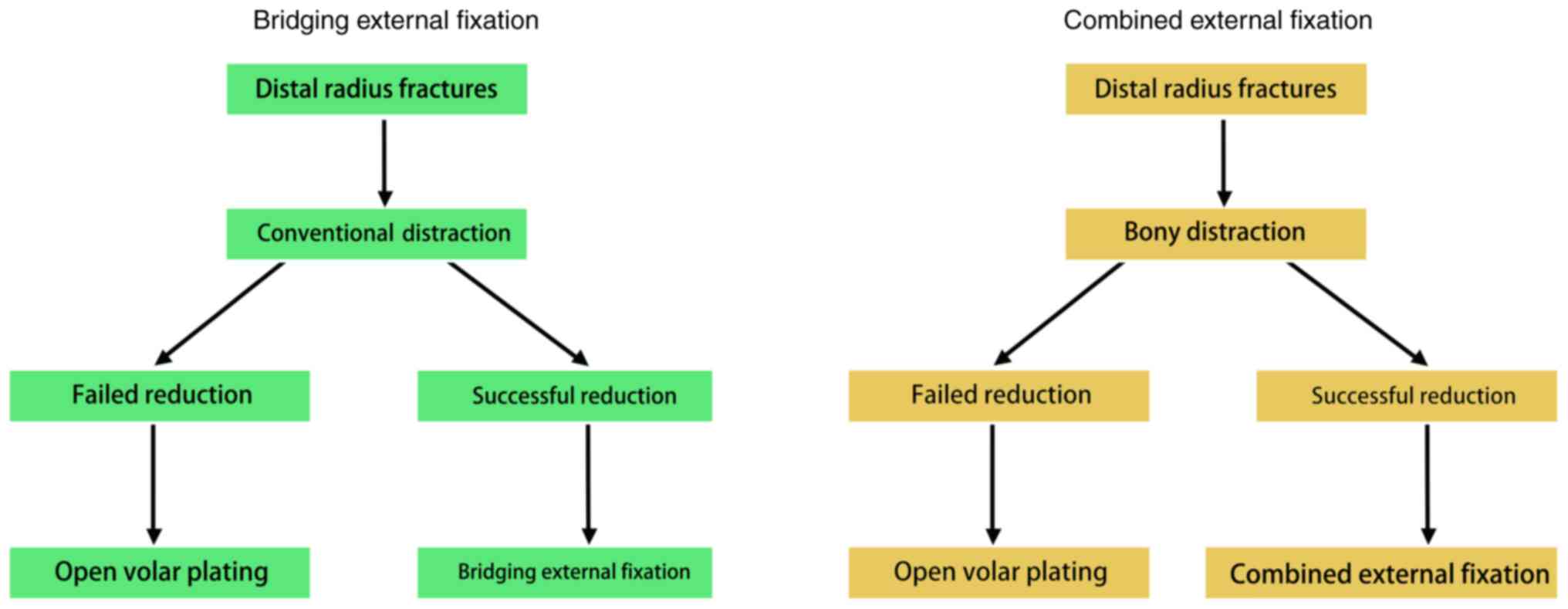

BEF and non-BEF, was used in the present study (Fig. 1).

The present prospective study aimed to compare the

efficacies of BEF and CEF in preventing RHL in older patients with

DRF.

Patients and methods

Patient selection

The research protocol was approved by the

Investigational Review Board of Jingxing County Hospital

(Shijiazhuang, China; approval no. 2017005), and written informed

consent was obtained from all participants prior to the study. The

patients involved in this study consented to the publication of

their images.

Between January 2018 and December 2022, 147

consecutive older patients (≥55 years) (10) with DRF were prospectively enrolled

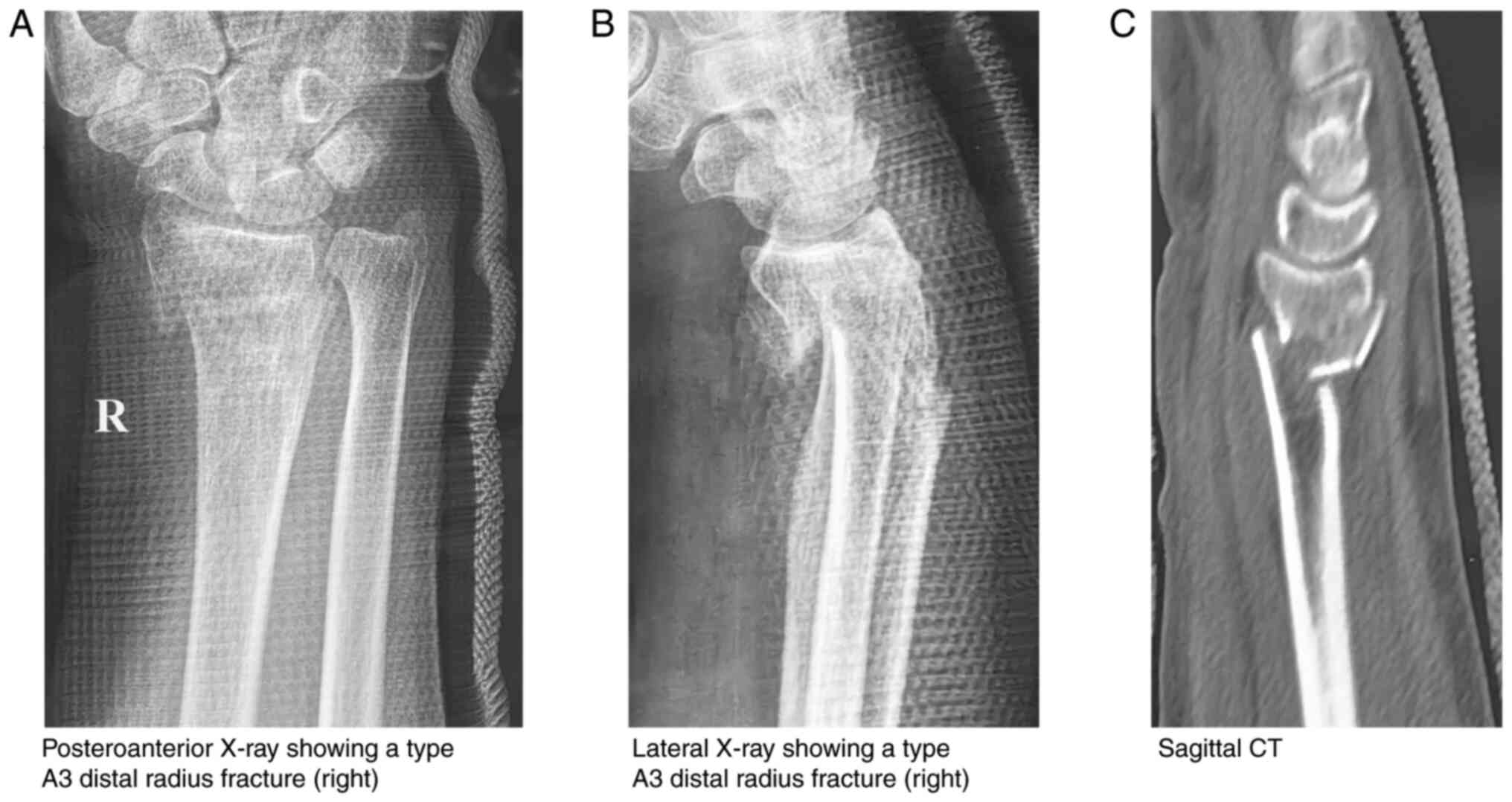

in the present study. Preoperatively, standard posteroanterior and

lateral wrist radiographs were obtained from all patients. Computed

tomography (CT) scans and three-dimensional reconstructions were

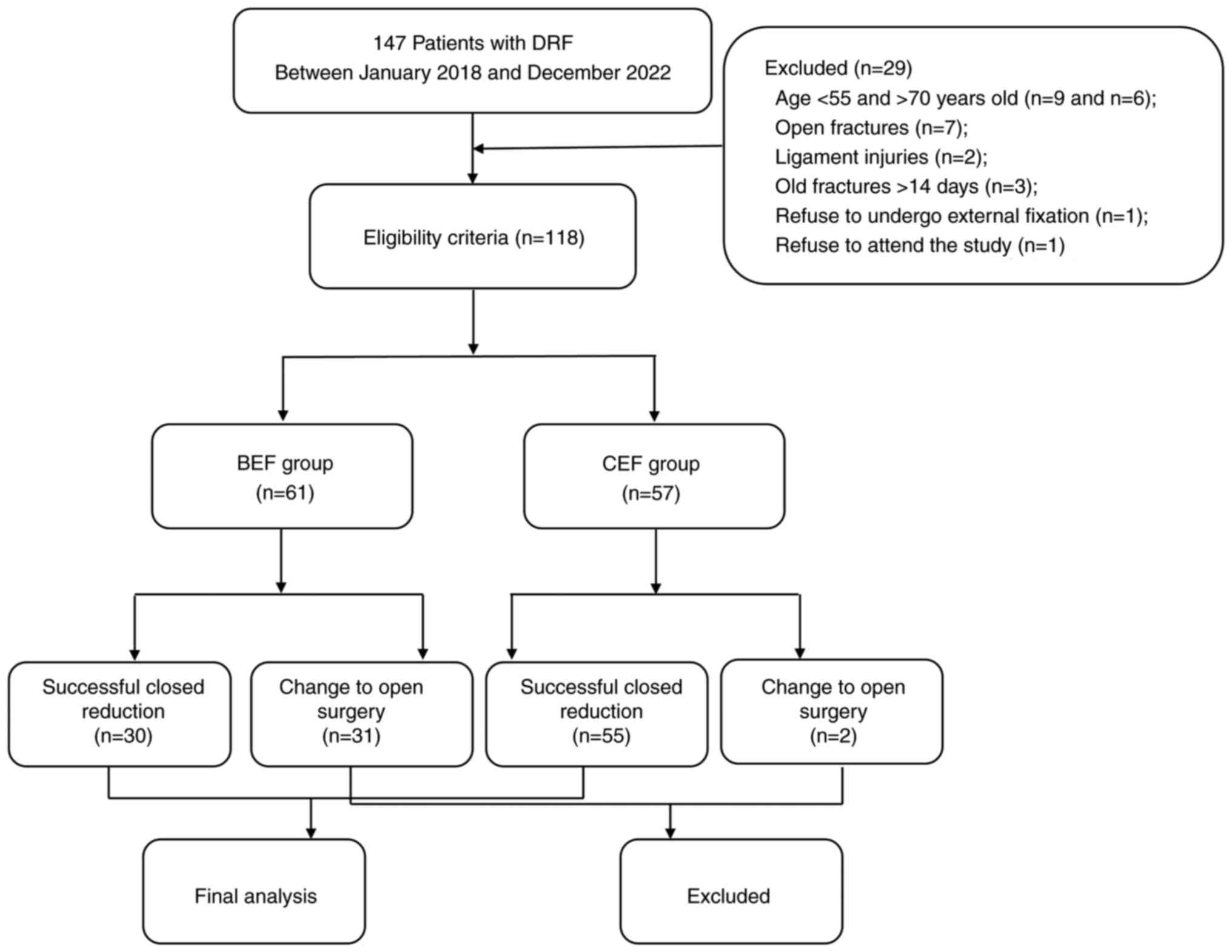

performed, as required (Fig. 2).

Magnetic resonance imaging was performed when a ligament tear was

suspected. Fracture diagnoses and types were determined by three

senior orthopaedic surgeons who were not involved in the

treatments.

The eligibility criteria for the study were as

follows: i) Patients aged between 55 and 70 years; ii) closed

distal radius fractures; iii) acute fractures within 14 days of

injury; iv) confirmed diagnoses of A2, A3, B1, B3, C1, C2 and C3

fractures based on the AO Foundation and Orthopaedic Trauma

Association (AO/OTA) Classification (11); and v) a normal opposite upper limb

for comparison. Patients meeting any of the following conditions

were excluded: i) Patients aged <55 years, as osteoporosis

rarely occurs (n=9); ii) patients aged >70 years, as malunion is

often tolerable (n=6); iii) open fractures (n=7); iv) type A1

fractures, as these do not involve the radius; v) type B2

fractures, as fixation with pins is difficult; vi) combined

ligament injuries (n=2); vii) fractures >14 days old, as

percutaneous reduction becomes difficult (n=3); viii) patients who

refused to undergo external fixation (n=1); and ix) patients who

declined to participate in the study (n=1) (Fig. 3).

Patients were randomly and blindly allocated to the

BEF (n=61) and CEF (n=57) groups using a computational pseudorandom

number generator. Patients in the BEF group underwent BEF, whereas

those in the CEF group were subjected to CEF. All operations were

performed by the same senior surgeon.

Conventional distraction and BEF

Conventional distraction and BEF surgery were

performed under brachial plexus anesthesia without tourniquet

control. Fracture reduction was achieved using a distraction

manoeuvre, as described by Capo et al (12). Insertion of two 3.5-mm Schanz pins

(Hengshui Zengli Medical Instrument Co., Ltd.), into the second

metacarpal and proximal radius was performed, and a bridging

external fixator (Hengshui Zhengli Medical Instrument Company Ltd.)

was installed to maintain reduction. Several 2.5-mm Steinmann pins

(Hengshui Zengli Medical Instrument Co., Ltd.), were inserted to

secure small fragments, as needed. The reduction quality was

assessed using intraoperative X-rays.

Bony distraction and CEF

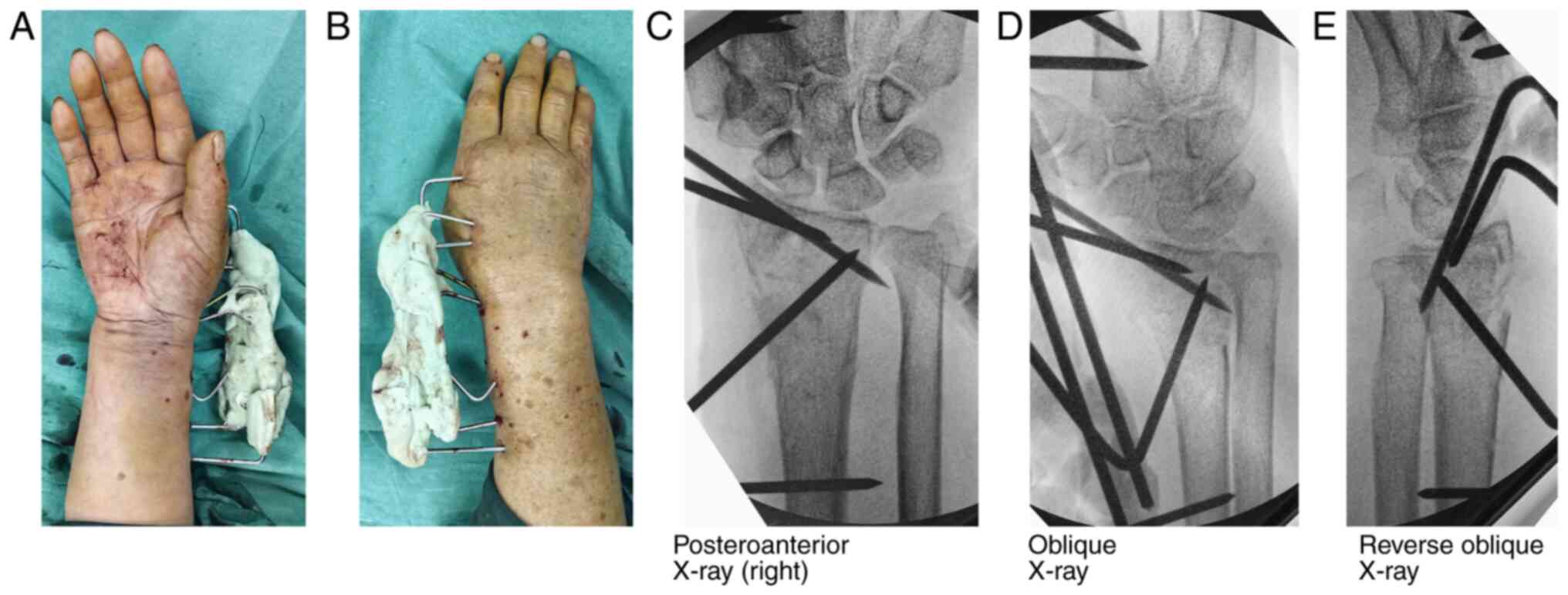

Bony distraction and CEF surgery were also performed

under brachial plexus anesthesia without tourniquet control. The

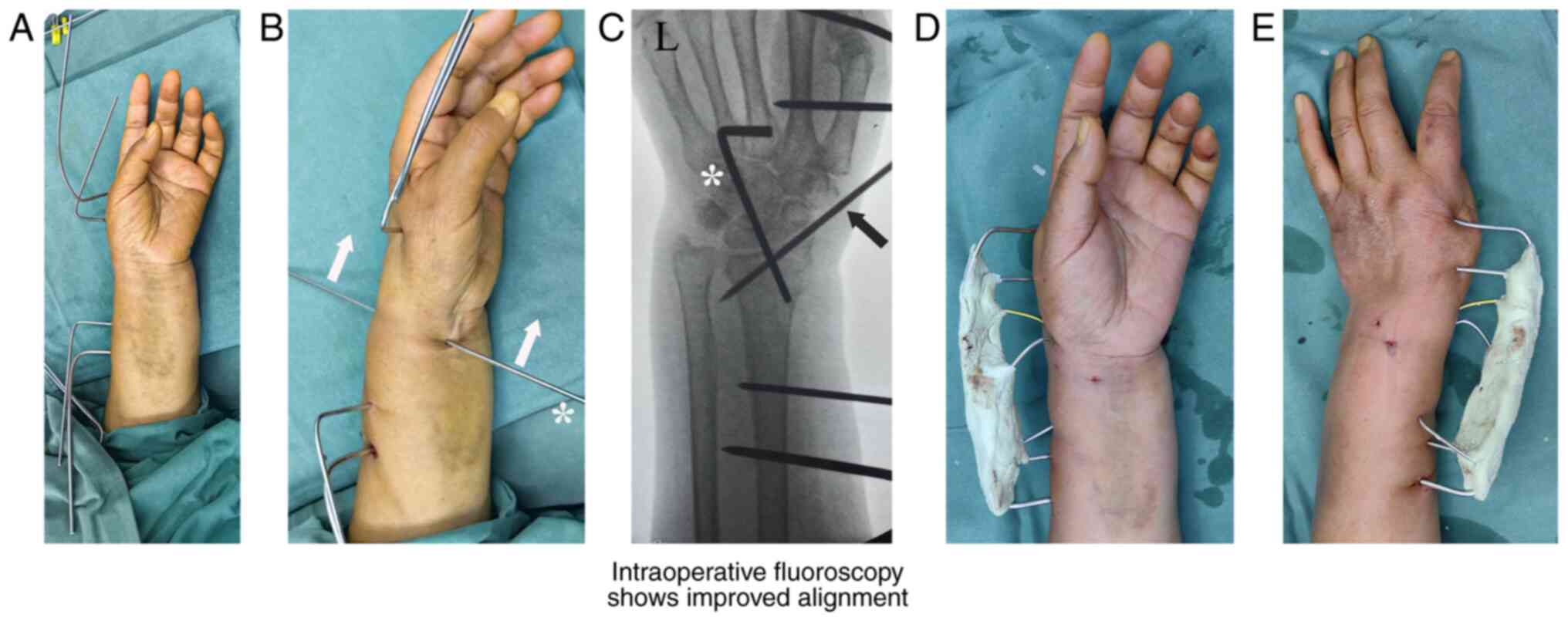

surgery involved the insertion of two to three 2.5-mm transverse

Steinmann pins into the second metacarpal and two to three pins

into the proximal radius, respectively (Fig. 4A). A 2.5-mm Steinmann pin was

manually placed across the fracture line from the anterior to the

posterior wrist. The insertion point was located 0.5 cm distal to

the fracture line that was identified on X-rays and 0.5 cm medial

to the radial artery that could be palpated easily. The attending

surgeon pulled both ends of the reduction pin distally to reduce

the fracture (Fig. 4B). The normal

volar tilt of the radius was restored by pulling the dorsal pin end

more distally and the volar pin end more proximally. The reduction

was maintained using several oblique pins inserted from the radial

styloid and proximal radius. Satisfactory reduction was confirmed

by fluoroscopy (Fig. 4C). All

K-wires were bent toward the fracture site, ~2 cm away from the

skin. The monomers (liquid) and polymers (powder) of the bone

cement (Palacos Bone Cements; Heraeus Medical GmbH) were mixed,

which changed the bone cement viscosity from a runny liquid to a

dough-like state. Subsequently, the mixture was applied to all bent

pin ends to allow it to harden into a solid material (Fig. 4D and E). Satisfactory reduction was confirmed

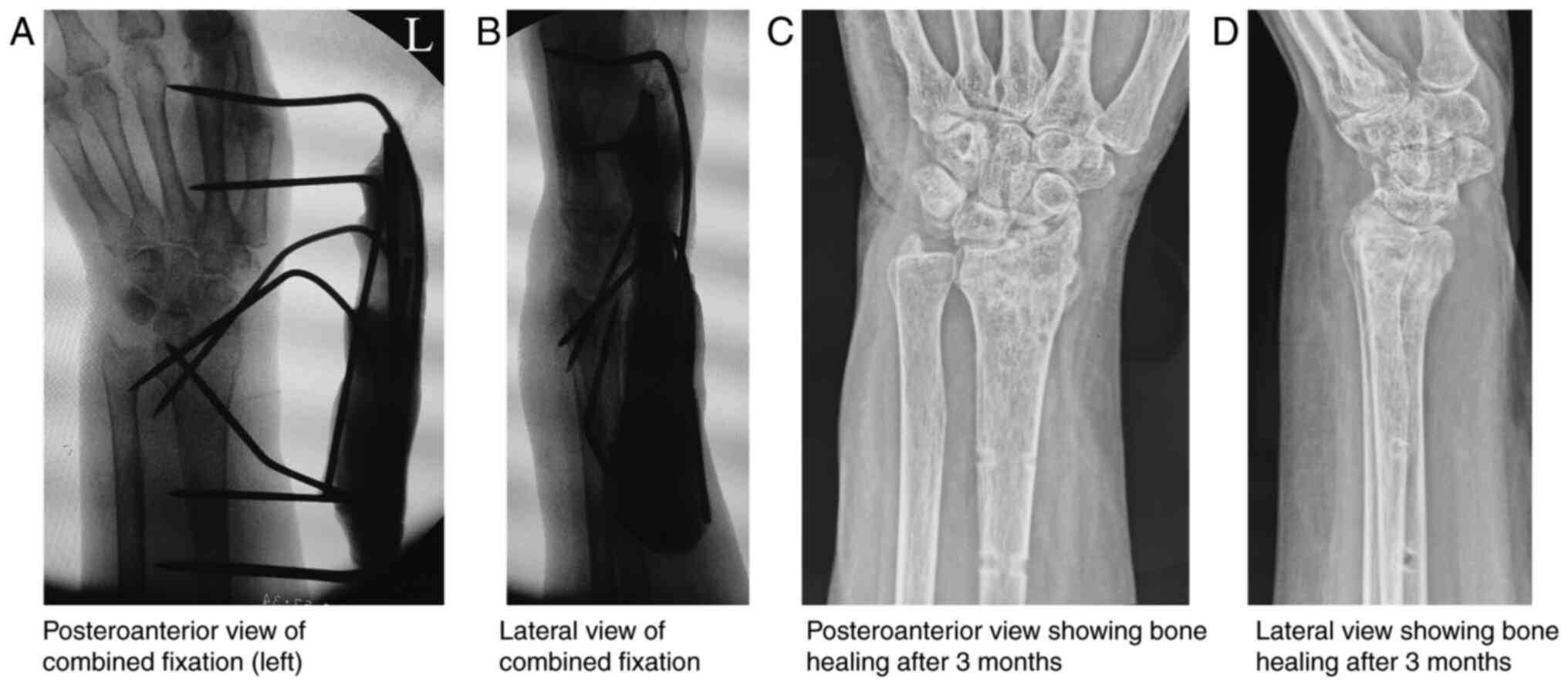

using intraoperative radiography (Fig.

5A and B).

Converting to open surgery

The patients with failed reduction (radial

inclination <15˚, radial shortening <5 mm, dorsal tilt

>15˚ and articular step-off >2 mm), irrespective of group,

were converted to open volar plating as described by Alter et

al (13).

Postoperative management

The injured wrist was protected using a dorsal

splint, which allowed for a range of motion (ROM) of the fingers

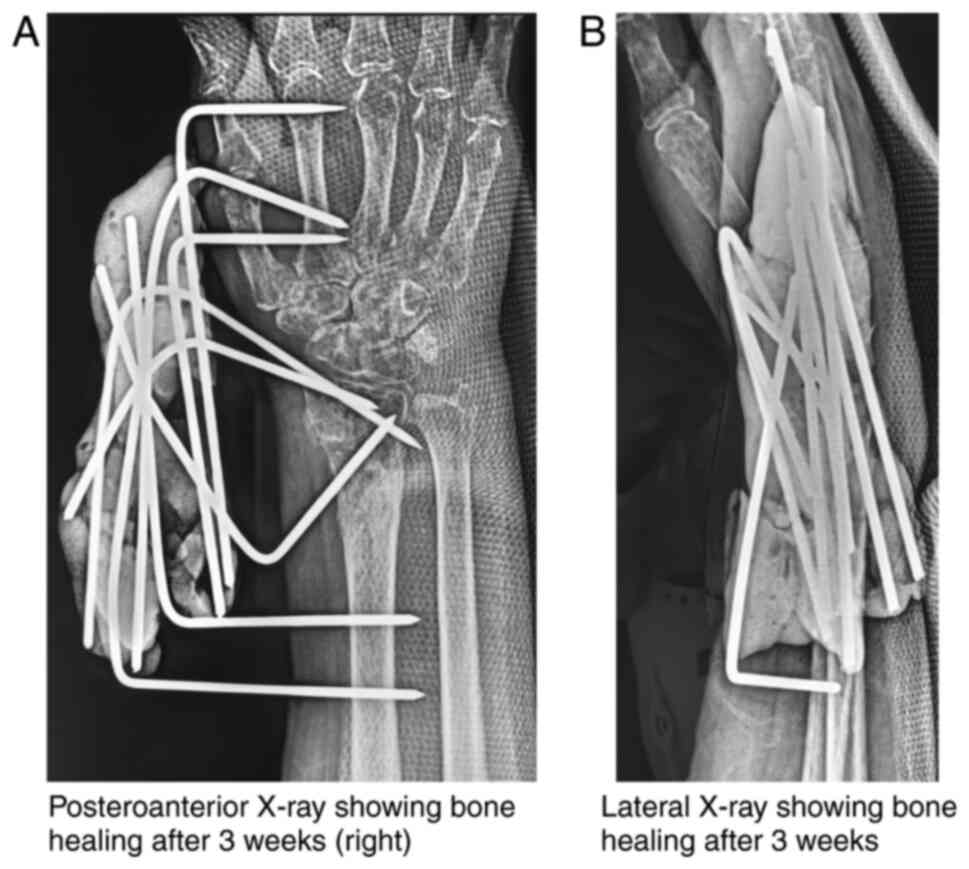

and thumb. The splint was removed after 4 weeks. Radiographs were

taken every 2 weeks until bone healing had occurred, and the

external fixators were removed (Fig.

5C and D). ROM exercises of

the wrist were performed thereafter.

Outcome evaluation

Radial height, palmar tilt, radial inclination,

ulnar variance and articular step-off were measured using standard

radiography. Fracture consolidation and Lidström classification

(14) was determined using

radiography. The wrist ROM was measured using a goniometer

(Fig. 6). Grip strength was

measured with a hand dynamometer (Jamar®; J.A. Preston

Corporation). Pronation torque of the wrist was assessed using the

McConkey method (15) at five

rotation positions (90˚ supination, 45˚ supination, neutral, 45˚

pronation and 80˚ pronation). All measurements were compared with

those on the opposite side. To eliminate the discrepancy between

dominant and non-dominant hand strength, the scores for analysis

were based on the premise that grip strength was 15% higher on the

dominant side than that on the non-dominant side, and no correction

was required for left-handed individuals, according to a previous

study (16). At the final

follow-up, the patients were asked to complete the following

questionnaires: The level of pain during specified activities based

on a numeric rating scale (NRS), a modified Mayo Wrist Score, a

Disabilities of the Arm Shoulder and Hand score, a Patient-Rated

Wrist Evaluation score and a patient satisfaction score

questionnaire (17-21).

To evaluate efficiency of the two external fixation techniques,

those patients undergoing open surgery were excluded.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS

version 21.0 (IBM Corp.). Continuous variables are expressed as the

mean ± SD. Pearson's χ2 test and Fisher's exact test

were used for qualitative data. An unpaired t-test was used for the

between-group analyses, while a paired t-test was used for the

within-group analyses. Pearson's χ2 test and Fisher's

exact test were used to compare the Lidström classification. An

unpaired t-test was used to compare the radiological parameters and

clinical outcomes between the BEF group and the CEF group.

P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

In the present study, 147 patients were reviewed,

with 118 patients (49 men and 69 women) eligible for the final

analysis (Table I). The BEF group

comprised 61 patients, with a mean age of 61.97±3.61 years (range,

56-68 years). According to the AO/OTA classification, the fracture

types in the BEF group were as follows: 3 cases of A2, 8 of A3, 7

of B1, 12 of B3, 17 of C1, 11 of C2 and 3 of C3. The mean follow-up

period was 29.70±3.47 months (range 24-36 months). The CEF group

included 57 patients, with a mean age of 61.51±4.00 years (range,

55-70 years). According to the AO/OTA classification, the CEF group

included 4 A2, 6 A3, 10 B1, 8 B3, 12 C1, 13 C2, and 4 C3 fractures.

The mean follow-up period was 28.53±2.76 months (range, 24-33

months). A successful closed reduction was achieved in 30 patients

(49.2%) in the BEF group and 55 patients (96.5%) in the CEF group.

Pin-site infection occurred in 1 patient (3.3%) in the BEF group

and 1 patient (1.8%) in the CEF group. Statistically significant

differences were observed in operative time (t=12.52; P<0.01),

successful closed reduction (χ2=32.74; P<0.01),

change to open surgery (χ2=32.74; P<0.01) and

treatment cost (t=4585.26; P<0.01). However, no statistically

significant differences were found in AO/OTA classification

(χ2=2.81; P=0.83), time between injury and operation

(t=1.17; =0.25), infection (χ2=0.19; P=0.67), bone

healing time (t=0.69; P=0.49) and follow-up duration (t=1.17;

P=0.09).

| Table IPatient characteristics of the two

groups. |

Table I

Patient characteristics of the two

groups.

| Characteristics | BEF group (n=61) | CEF group (n=57) | Statistical

value | P-value |

|---|

| Mean age ± SD

(range), yearsa | 61.97±3.61

(56-68) | 61.51±4.00

(55-70) | 0.66 | 0.51 |

| Sex (m:f),

nb | 26:35 | 23:34 | 0.06 | 0.80 |

| Injured side (l:r),

nb | 22:39 | 19:38 | 0.10 | 0.76 |

| Dominance,

nb | 34 | 31 | 0.02 | 0.88 |

| Cause,

nc | | | 0.33 | 0.98 |

|

Fall | 27 | 25 | | |

|

Road traffic

accident | 19 | 17 | | |

|

Sports | 12 | 11 | | |

|

Others | 3 | 4 | | |

| AO/OTA,

nc | | | 2.92 | 0.84 |

|

A2 | 3 | 4 | | |

|

A3 | 8 | 6 | | |

|

B1 | 7 | 10 | | |

|

B3 | 12 | 8 | | |

|

C1 | 17 | 12 | | |

|

C2 | 11 | 13 | | |

|

C3 | 3 | 4 | | |

| Ulnar styloid

fracture, nb | 24 | 21 | 0.08 | 0.78 |

| Mean hospital stay

± SD (range), daysa | 6.69±1.78

(4-10) | 6.44±1.54

(3-9) | 0.82 | 0.42 |

| TBIO (range),

daysa | 4.75±1.29

(3-7) | 4.51±0.97

(3-6) | 1.17 | 0.25 |

| Mean operative time

± SD, mina | 52.61±7.03

(42-65) | 38.54±4.91

(30-47) | 12.52 | <0.01 |

| Successful closed

reduction, n (%)b | 30 (49.2) | 55 (96.5) | 32.74 | <0.01 |

| Change to open

surgery, n (%)b | 31 (50.8) | 2 (3.5) | 32.74 | <0.01 |

| Infection, n

(n/total n, %)c | 1

(3.3)d | 1

(1.8)e | - | 1.00 |

| Mean cost ± SD

(RMB)a | 8,023.35±5.53 | 563.73±7.91 | 4,585.26 | <0.01 |

| Mean bone healing

time ± SD (range), weeksa | 7.20±1.13

(6-9) | 7.05±0.80

(6-8) | 0.69 | 0.49 |

| Mean follow-up time

± SD (range), monthsa | 29.70±3.47

(24-36) | 28.53±2.76

(24-33) | 1.71 | 0.09 |

The radiological parameters of intraoperative closed

reduction, bone healing and final follow-up were compared between

the BEF group and the CEF group (Table II). The BEF group showed no

significant differences regarding radial height (t=0.16; P=0.88),

palmar tilt (t=0.40; P=0.69), radial inclination (t=0.46; P=0.65),

ulnar variance (t=0.02; P=0.98) and articular step-off (t=0.93;

P=0.36) between bone healing and the final follow-up. Similarly,

the CEF group also showed no significant differences in radial

height (t=0.69; P=0.49), palmar tilt (t=0.06; P=0.95), radial

inclination (t=0.14; P=0.89), ulnar variance (t=0.39; P=0.70) and

articular step-off (t=0.86; P=0.39) between bone healing and the

final follow-up. Bone healing showed no significant differences in

radial height (t=1.19; P=0.24), palmar tilt (t=0.41, P=0.69),

radial inclination (t=0.37; P=0.71), ulnar variance (t=0.30;

P=0.77) and articular step-off (t=0.92; P=0.36) between the BEF

group and CEF groups. Similarly, the final follow-up also showed no

significant differences in radial height (t=0.78; P=0.44), palmar

tilt (t=0.76; P=0.45), radial inclination (t=0.84; P=0.40), ulnar

variance (t=0.60; P=0.55) and articular step-off (t=0.60; P=0.55)

between the two groups. However, there were significant differences

in radial height (t=10.06; P<0.01), palmar tilt (t=8.77;

P<0.01), radial inclination (t=9.05; P<0.01), ulnar variance

(t=4.19; P<0.01), articular step-off (t=5.05; P<0.01) and

articular step-off ≥2 mm (t=23.45; P<0.01) during intraoperative

closed reduction between the two groups (Table II).

| Table IIRadiological parameters measured at

the time of intraoperative closed reduction, bone healing and final

follow-up. |

Table II

Radiological parameters measured at

the time of intraoperative closed reduction, bone healing and final

follow-up.

| Parameter | BEF group

(n=61a;

n=30b) | CEF group

(n=57a;

n=55b) | t value | P-value |

|---|

| Radial height,

mm | | | | |

|

Intraoperative

closed reduction | 10.06±1.07 | 12.13±1.16 | 10.06 | <0.01 |

|

Bone

healing | 11.78±1.15 | 12.09±1.15 | 1.19 | 0.24 |

|

Final

follow-up | 11.73±1.14 | 11.94±1.18 | 0.78 | 0.44 |

|

t

valuec | 0.16 | 0.69 | | |

|

P-valuec | 0.88 | 0.49 | | |

| Palmar tilt, ˚ | | | | |

|

Intraoperative

closed reduction | 10.08±1.26 | 12.09±1.22 | 8.77 | <0.01 |

|

Bone

healing | 11.94±1.10 | 12.04±1.17 | 0.41 | 0.69 |

|

Final

follow-up | 11.82±1.09 | 12.03±1.24 | 0.76 | 0.45 |

|

t

valuec | 0.40 | 0.06 | | |

|

P-valuec | 0.69 | 0.95 | | |

| Radial inclination,

˚ | | | | |

|

Intraoperative

closed reduction | 20.14±1.65 | 22.84±1.59 | 9.05 | <0.01 |

|

Bone

healing | 22.69±1.89 | 22.84±1.58 | 0.37 | 0.71 |

|

Final

follow-up | 22.49±1.51 | 22.79±1.63 | 0.84 | 0.40 |

|

t

valuec | 0.46 | 0.14 | | |

|

P-valuec | 0.65 | 0.89 | | |

| Ulnar variance,

mm | | | | |

|

Intraoperative

closed reduction | 1.78±1.10 | 1.08±0.61 | 4.19 | <0.01 |

|

Bone

healing | 1.05±0.58 | 1.01±0.59 | 0.30 | 0.77 |

|

Final

follow-up | 1.04±0.56 | 0.96±0.60 | 0.60 | 0.55 |

|

t

valuec | 0.02 | 0.39 | | |

|

P-valuec | 0.98 | 0.70 | | |

| Articular stepoff,

mm | | | | |

|

Intraoperative

closed reduction | 1.58±0.91 | 0.87±0.57 | 5.05 | <0.01 |

|

Bone

healing | 0.85±0.39 | 0.76±0.46 | 0.92 | 0.36 |

|

Final

follow-up | 0.74±0.47 | 0.68±0.45 | 0.60 | 0.55 |

|

t

valuec | 0.93 | 0.86 | | |

|

P-valuec | 0.36 | 0.39 | | |

| Articular stepoff

≥2 mm, n | | | | - |

|

Intraoperative

closed reduction | 25 | 2 | 23.45 | <0.01 |

|

Bone

healing | 0 | 0 | | |

|

Final

follow-up | 0 | 0 | | |

Based on the Lidström classification, the BEF group

included 19 excellent and 11 good results at the time of bone

healing, and 27 excellent and 3 good results at the final

follow-up; the CEF group included 45 excellent and 10 good results

at the time of bone healing, and 54 excellent and 1 good result at

the final follow-up. Significant differences were observed between

bone healing and the final follow-up in the BEF group

(χ2=5.96; P<0.05) and in the CEF group

(χ2=8.18; P<0.01). However, there were no significant

differences between the BEF and CEF groups regarding bone healing

(χ2=3.57, P=0.06) or the final follow-up (P=0.12)

(Table III). The mean cost of

CEF was Renminbi (RMB) 563.73±7.91 (7 to 12 pins, each costing RMB

5.04; bone cement, RMB 517), while the mean cost of BEF was RMB

8,023.35±5.53 (3 to 6 pins, each costing RMB 5.04; external

fixator, RMB 8000) (t=4,585.26; P<0.01). The cost of CEF was ~7%

of that of BEF (Table I).

| Table IIILidström classification at the time

of bone healing and the final follow-up. |

Table III

Lidström classification at the time

of bone healing and the final follow-up.

| | BEF group

(n=30) | CEF group

(n=55) | BEF vs. CEF for

bone healinga | BEF vs. CEF for

final follow-upb |

|---|

| Classification

(score) | Bone healing | Final

follow-up | Bone healing | Final

follow-up | Statistical

value | P-value | Statistical

value | P-value |

|---|

| Excellent

(90-100) | 19 | 27 | 45 | 54 | 3.57 | 0.06 | - | 0.12 |

| Good (80-90) | 11 | 3 | 10 | 1 | | | | |

| Fair (60-80) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | | | | |

| Poor (<60) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | | | | |

| Statistical

valuea | 5.96 | 8.18 | | | | |

| P-value | 0.015 | 0.004 | | | | |

At the final follow-up, there were no significant

differences between the two groups in terms of active ROM (flexion:

t=0.80, P=0.43; extension: t=1.48, P=0.14; radial deviation:

t=0.96, P=0.34; ulnar deviation: t=1.07, P=0.29; pronation: t=1.17,

P=0.25; and supination: t=0.82, P=0.41), grip strength (t=0.98,

P=0.33), supination torque (90˚ of supination: t=1.48, P=0.14; 45˚

of supination: t=1.55, P=0.13; neutral: t=0.62, P=0.54; 45˚ of

pronation: t=0.94, P=0.35; and 80˚ of pronation: t=0.80, P=0.43),

wrist pain (activities of daily living: t=1.33, P=0.19; and hard

work: t=1.75, P=0.09), modified Mayo Wrist score (t=0.86, P=0.39),

Disabilities of the Arm Shoulder and Hand score (t=0.78, P=0.44),

Patient-Rated Wrist Evaluation score (t=0.93, P=0.36), and patient

satisfaction (t=1.74, P=0.09) (Table

IV). Figs. 7, 8 and 9

show another representative case.

| Table IVFunctional and clinical outcomes at

the final follow-up. |

Table IV

Functional and clinical outcomes at

the final follow-up.

| Outcome | BEF group

(n=30) | CEF group

(n=55) | Statistical

valuea | P-value |

|---|

| Active ROM, ˚ | | | | |

|

Flexion | 68.13±6.14 | 69.02±4.09 | 0.80 | 0.43 |

|

Extension | 52.43±3.39 | 53.36±2.37 | 1.48 | 0.14 |

|

Radial

deviation | 25.57±2.61 | 26.05±2.02 | 0.96 | 0.34 |

|

Ulnar

deviation | 29.60±3.20 | 30.40±3.33 | 1.07 | 0.29 |

|

Pronation | 83.30±5.86 | 84.75±5.19 | 1.17 | 0.25 |

|

Supination | 83.93±7.26 | 85.16±6.18 | 0.82 | 0.41 |

|

Grip

strength, % | 98.30±4.97 | 99.33±4.44 | 0.98 | 0.33 |

| Supination torque,

% | | | | |

|

90˚ of

supination | 80.93±4.17 | 91.18±3.47 | 1.48 | 0.14 |

|

45˚ of

supination | 94.53±1.81 | 95.02±1.08 | 1.55 | 0.13 |

|

Neutral | 89.23±5.65 | 88.42±5.92 | 0.62 | 0.54 |

|

45˚ of

pronation | 89.70±4.04 | 90.47±3.40 | 0.94 | 0.35 |

|

80˚ of

pronation | 95.50±4.28 | 96.13±2.93 | 0.80 | 0.43 |

| Wrist pain score

(NRS) | | | | |

|

Rest | 0 | 0 | - | - |

|

Activities

of daily living | 1.30±0.92 | 1.05±0.76 | 1.33 | 0.19 |

|

Hard

work | 1.83±1.29 | 1.40±0.97 | 1.75 | 0.09 |

| Modified Mayo Wrist

score | 92.23±4.22 | 93.13±4.75 | 0.86 | 0.39 |

| DASH score | 8.00±5.10 | 8.85±4.66 | 0.78 | 0.44 |

| PRWE score | 9.80±4.90 | 8.69±5.46 | 0.93 | 0.36 |

| Patient

satisfaction | 9.20±0.66 | 9.45±0.63 | 1.74 | 0.09 |

Discussion

The present study found that CEF may be as effective

as BEF in preventing RHL in older patients with DRF. Percutaneous

bony distraction may be more effective than conventional

distraction manoeuvres for achieving anatomical reduction with

minor morbidity. Both conventional and bony distraction manoeuvres

can produce similar functional outcomes and patient satisfaction

only if a good reduction has been achieved. The outcomes show that

there are no complications due to the percutaneous bony

distraction. The two techniques demonstrate a similar ability for

bone remodeling. Moreover, CEF is less expensive than BEF.

RHL is commonly observed in older patients due to

the axial load on the wrist (22).

RHL produces abnormal volar tilt, radial inclination and ulnar

variance (23). The abnormalities

further contribute to the development of ulnar impaction syndrome,

triangular fibrocartilage complex tears, distal radioulnar joint

instability, ulnar carpal arthritis, and rupture of the extensor

tendons of the little and ring fingers (24).

Various surgical techniques can be employed for

distal radius fractures in older patients. Non-surgical treatments

using a splint or cast are commonly used in minimally displaced or

reducible fractures, but RHL often occurs after 3 weeks due to

osteoporosis, comminution and absorbable collapse at the fracture

site (25,26). Open reduction and plating are

straightforward techniques that provide radial support; however, an

axial load can still be applied to the distal radius. RHL may also

occur postoperatively in patients with osteoporosis, comminution or

insufficient consideration. The use of a bridging external fixator

can effectively avoid axial load on the distal radius and wire

migration (27), but small

fragments of the distal radius cannot be maintained, even when

several spins are used. To reinforce fixation, CEF combining both

BEF and non-BEF has been developed.

Meng et al (28) reported a study in which 78 types of

A2, A3 and B1 distal radius fractures were treated using

percutaneous fixation using a cemented K-wire CEF. It was suggested

that this minimally invasive technique effectively prevented

redisplacement and wire migration, as the cement frame secured all

the pins together. Moreover, percutaneous bony distraction is also

more powerful and effective than conventional distraction in

restoring the radial height, resulting in a high-quality reduction.

This simplifies the preoperative plan, as all distal fragments can

be automatically reduced under powerful bony distraction. The

rationale is that the ligaments and tendons surrounding the wrist

(such as the rotator cuff of the shoulder) are tension-like

splints, pushing the fragments to be reduced. The present study

showed that BEF and CEF achieved similar radiological parameters

and functional outcomes. However, CEF had more advantages than BEF

in achieving a higher rate of successful closed reduction, shorter

operative time and lower treatment cost. The Lidström

classification categorises DRFs based on the fracture line,

direction of displacement, degree of displacement, articular

involvement and distal radioulnar joint involvement. The similar

changes observed between the time of bone healing and the final

follow-up in both techniques suggest a comparable ability for bone

remodeling.

The indication for CEF is AO/OTA classification type

A2, A3, B1, B3, C1, C2 and C3 distal radius fractures, especially

in older adult patients (≥55 years) with poor bone quality and

comminuted fractures, either open or closed fractures, and either

extra- or intraarticular fractures. Contraindications include minor

displacement, old fractures, infection statues and health issues.

The advantages of CEF are that it is easy to perform and has a high

success rate, especially if surgeons are familiar with the volar

wrist anatomy; inexperienced surgeons can identify structures using

ultrasonography or place the reduction pin via blunt dissection

through a small incision. Pin migration into the radiocarpal joint

due to articular fragmentation is rare; however, pin reduction may

also be achieved in this setting. Alternatively, adjustment of the

pin direction is preferred. Anatomical reduction with intact soft

tissues surrounding the wrist may lead to superior wrist function.

No complications due to over-distraction to the ligaments are

observed. However, the shortcomings of CEF include the risk of

iatrogenic injuries to the tendons, median nerve, superficial

branch of the radial nerve and radial artery (29). The present study confirmed that

minimally invasive CEF can achieve satisfactory fracture reduction

and strong external fixation with a short operative time and low

treatment cost.

Infection is a rare complication of minimally

invasive surgery following distal radius fracture. Pin-site

infection occurred in 1 patient (1/30, 3.3%) in the BEF group and

in 1 patient (1/55, 1.8%) in the CEF group, and both are lower than

the rate of pin-site infection (10.3%) reported in the literature

(30). Most pin-site infections

are relatively minor and resolve with disinfectant care, oral

antibiotic therapy and/or removal of the external fixator. Pin

loosening is associated with a high risk of pin-site infection,

which can be reduced by securing all the wire ends to a cemented

CEF (28). The surgeons should not

only pay attention to intraoperative sterilization but also to the

treatment of related underlying diseases, such as diabetes,

hypoimmunity, hypoproteinemia and infection of other body

parts.

The most common reason for distal radial malunion is

improper treatment, with an incidence rate of 33% (31). Malunion is defined as one of the

following: Radial inclination <15˚ on posteroanterior view;

radial length >5 mm shortening on posteroanterior view; radial

tilt >15˚ dorsally or 20˚ volar tilt on lateral view; or

articular incongruity >2 mm of step-off (30). When the DRF is less shortened, bone

grafting may not be necessary if the DRF is stable and some

anterior cortical contact remains. When intraoperative reduction

creates a large space with a loss of cortical contact, the risk of

malunion is greater, and bone grafting is required to avoid

postoperative fracture non-union. Allogeneic bone grafts, including

corticocancellous or cancellous bone, may be suitable candidates;

however, autogenous iliac grafts remain the optimal selection both

mechanically and biologically. During the postoperative follow-up,

high-resolution peripheral CT is feasible to further the evaluation

of bone healing in DRF (32). In

the present study, all patients in both groups showed satisfactory

bone healing, and no postoperative fracture non-union was

observed.

The present study had some limitations. First, the

treatments could not be performed in blinded manner due to the

nature of the study, which may have resulted in a selection bias.

Second, the manoeuvres and assessments were performed at different

time points, and the surgeons' experience improved with time,

thereby influencing the ascertainment of the effects of the

techniques. Third, the biomechanics of fixation were not assessed

and should be investigated in future studies and in randomised

controlled multicentre clinical trials to further determine the

efficacy of the treatments.

In conclusion, CEF may be as effective as BEF in

preventing RHL in older patients with DRF. Percutaneous bony

distraction may prove more effective than conventional distraction

manoeuvres in achieving anatomical reduction with minor morbidity.

The two techniques demonstrate a similar ability for bone

remodeling. Further studies are needed to explore the therapeutic

advantages of CEF over BEF, especially considering its lower cost

when compared with BEF.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

JL and WD were involved in the study conception,

design, implementation, data analysis and interpretation, as well

as the writing of the paper. XZ and YPY contributed to the

collection, analysis and interpretation of data. DZ and YY

participated in implementation of the surgery and data collection.

RC was involved in the study conception and design. All listed

authors have made significant contributions to the development and

writing of this article. All authors have read and approved the

manuscript. JL and WD confirm the authenticity of all the raw

data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The research protocol was approved by the

Investigational Review Board of Jingxing County Hospital

(Shijiazhuang, China; approval no. 2017005), and written informed

consent was obtained from all participants prior to the study.

Patient consent for publication

The patients involved in this study consented to the

publication of their images.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Shapiro LM and Kamal RN: Management of

Distal Radius Fractures Work Group; Nonvoting Clinical Contributor;

Nonvoting Oversight Chairs; Staff of the American Academy of

Orthopaedic Surgeons and the American Society for Surgery of the

Hand. Distal Radius Fracture Clinical Practice Guidelines-Updates

and Clinical Implications. J Hand Surg Am. 46:807–811.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Meena S, Sharma P, Sambharia AK and Dawar

A: Fractures of distal radius: An overview. J Family Med Prim Care.

3:325–332. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Summers K, Mabrouk A and Fowles SM: Colles

Fracture, 2023 Jul 31. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island

(FL), StatPearls Publishing, Jan, 2025.

|

|

4

|

Figl M, Weninger P, Liska M, Hofbauer M

and Leixnering M: Volar fixed-angle plate osteosynthesis of

unstable distal radius fractures: 12 months results. Arch Orthop

Trauma Surg. 129:661–669. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

LaMartina J, Jawa A, Stucken C, Merlin G

and Tornetta P III: Predicting alignment after closed reduction and

casting of distal radius fractures. J Hand Surg Am. 40:934–939.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Han LR, Jin CX, Yan J, Han SZ, He XB and

Yang XF: Effectiveness of external fixator combined with T-plate

internal fixation for the treatment of comminuted distal radius

fractures. Genet Mol Res. 14:2912–2919. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Ruch DS, Ginn TA, Yang CC, Smith BP,

Rushing J and Hanel DP: Use of a distraction plate for distal

radial fractures with metaphyseal and diaphyseal comminution. J

Bone Joint Surg Am. 87:945–954. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Kennedy SA and Hanel DP: Complex distal

radius fractures. Orthop Clin North Am. 44:81–92. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Kulshrestha V, Roy T and Audige L: Dynamic

vs static external fixation of distal radial fractures: A

randomized study. Indian J Orthop. 45:527–534. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Synn AJ, Makhni EC, Makhni MC, Rozental TD

and Day CS: Distal radius fractures in older patients: Is anatomic

reduction necessary? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 467:1612–1620.

2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Mehta SP, MacDermid JC, Richardson J,

MacIntyre NJ and Grewal R: A systematic review of the measurement

properties of the patient-rated wrist evaluation. J Orthop Sports

Phys Ther. 45:289–298. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Capo JT, Rossy W, Henry P, Maurer RJ,

Naidu S and Chen L: External fixation of distal radius fractures:

Effect of distraction and duration. J Hand Surg Am. 34:1605–1611.

2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Alter TH, Varghese BB, DelPrete CR, Katt

BM and Monica JT: Reduction techniques in volar locking plate

fixation of distal radius fractures. Tech Hand Up Extrem Surg.

26:168–177. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Lidstrom A: Fractures of the distal end of

the radius: A clinical and statistical study of end results. Acta

Orthop Scand Suppl. 41:1–118. 1959.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

McConkey MO, Schwab TD, Travlos A, Oxland

TR and Goetz T: Quantification of pronator quadratus contribution

to isometric pronation torque of the forearm. J Hand Surg Am.

34:1612–1617. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Incel NA, Ceceli E, Durukan PB, Erdem HR

and Yorgancioglu ZR: Grip strength: Effect of hand dominance.

Singapore Med J. 43:234–237. 2002.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Cantero-Téllez R, Algar LA, Cruz Gambero

L, Villafañe JH and Naughton N: Joint position sense testing at the

wrist and its correlations with kinesiophobia and pain intensity in

individuals who have sustained a distal radius fracture: A

cross-sectional study. J Hand Ther. 37:218–223. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

MacDermid JC, Turgeon T, Richards RS,

Beadle M and Roth JH: Patient rating of wrist pain and disability:

A reliable and valid measurement tool. J Orthop Trauma. 12:577–586.

1998.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Wajngarten D, Campos JÁDB and Garcia PPNS:

The disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand scale in the

evaluation of disability-A literature review. Med Lav. 108:314–323.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Mulders MAM, Kleipool SC, Dingemans SA,

van Eerten PV, Schepers T, Goslings JC and Schep NWL: Normative

data for the Patient-rated wrist evaluation questionnaire. J Hand

Ther. 31:287–294. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Green DP and O'Brien ET: Classification

and management of carpal dislocations. Clin Orthop Relat Res.

55–72. 1980.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Zhang L, Jiang H, Zhou J and Jing J:

Comparison of modified K-wire fixation with open reduction and

internal fixation (ORIF) for unstable colles fracture in elderly

patients. Orthop Surg. 15:2621–2626. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Cheng MF, Chiang CC, Lin CC, Chang MC and

Wang CS: Loss of radial height in Extra-articular distal radial

fracture following volar locking plate fixation. Orthop Traumatol

Surg Res. 107(102842)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Im JH, Lee JW and Lee JY: Ulnar impaction

syndrome and TFCC injury: Their relationship and management. J

Wrist Surg. 14:14–26. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Liddy N, Mohammed C, Kajitani SH, Prasad

N, Suresh SJ, Mathew P and LaPorte DM: Comparative outcomes of

surgical and nonsurgical treatments for scapholunate ligament

injuries with concomitant distal radius fractures: A systematic

review. Hand (N Y). 29(15589447251324533)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Raittio L, Launonen AP, Hevonkorpi T,

Luokkala T, Kukkonen J, Reito A, Laitinen MK and Mattila VM: Two

casting methods compared in patients with Colles' fracture: A

pragmatic, randomized controlled trial. PLoS One.

15(e0232153)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Biz C, Cerchiaro M, Belluzzi E, Bortolato

E, Rossin A, Berizzi A and Ruggieri P: Treatment of distal radius

fractures with bridging external fixator with optional percutaneous

K-Wires: What are the right indications for patient age, gender,

dominant limb and injury pattern? J Pers Med.

12(1532)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Meng H, Xu B, Xu Y, Niu H, Liu N and Sun

D: Treatment of distal radius fractures using a cemented K-wire

frame. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 23(591)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Gou Q, Xiong X, Cao D, He Y and Li X:

Volar locking plate versus external fixation for unstable distal

radius fractures: A systematic review and meta-analysis based on

randomized controlled trials. BMC Musculoskelet Disord.

22(433)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Yuan ZZ, Yang Z, Liu Q and Liu YM:

Complications following open reduction and internal fixation versus

external fixation in treating unstable distal radius fractures:

Grading the evidence through a Meta-analysis. Orthop Traumatol Surg

Res. 104:95–103. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Cognet JM and Mares O: Distal radius

malunion in adults. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res.

107(102755)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Van den Bergh JP, Szulc P, Cheung AM,

Bouxsein M, Engelke K and Chapurlat R: The clinical application of

high-resolution peripheral computed tomography (HR-pQCT) in adults:

State of the art and future directions. Osteoporos Int.

32:1465–1485. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|