Invasive fungal disease (IFD) is a fungal infection

in which fungi invade the body, grow and multiply in tissues,

organs or the bloodstream, triggering both inflammatory cascades

and direct tissue damage (1,2). IFD

complications markedly elevate mortality in patients with

hematological malignancies (3). A

Chinese multicenter study (n=4,192) analyzing post-chemotherapy IFD

epidemiology revealed three key findings: i) Pediatric cases

accounted for 16.9% of the cohort, with acute myeloid leukemia

(AML; 28.5%), non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (26.3%) and acute

lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL; 20.2%) being predominant; ii) severe

neutropenia occurred in 33.4% of chemotherapy sessions; and iii)

while overall chemotherapy-related mortality was 1.5%, this

escalated to 11.7% when IFD was present (4). IFD also has a high prevalence in

patients with hematological malignancies and hematopoietic stem

cell transplantation (HSCT) (5).

Aspergillus, Candida and Trichosporon are the

major pathogens of IFD: Infections caused by these fungi usually

manifest as non-specific symptoms such as fever and dyspnea, making

early diagnosis challenging, particularly in children. Invasive

Candida infections tend to be candidemia and hepatic and

splenic infections; in patients with liver and spleen infections,

these infections also present with right upper abdominal tenderness

and abdominal pain, making early diagnosis challenging (6,7). In

conclusion, IFD not only increases mortality associated with

post-chemotherapy pediatric hematological malignancies but also

presents multiple diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. Previous

studies highlight that pediatric IFD diagnosis faces unique

challenges due to non-specific clinical manifestations and limited

validated biomarkers for children (8,9).

The diagnostic challenges specific to pediatric IFD

are multifaceted: Clinical manifestations such as persistent fever

and dyspnea lack specificity, overlapping with bacterial or viral

infections, which delays early recognition (10). Invasive candidiasis often presents

as candidemia or hepatosplenic lesions, yet abdominal pain and

right upper quadrant tenderness may be subtle in children, leading

to underdiagnosis (11).

Diagnostic biomarkers face validation gaps in pediatric

populations, while (1→3)-β-D-glucan (BDG) demonstrates

age-dependent diagnostic thresholds (80 pg/ml in children vs. 120

pg/ml in adults), its cross-reactivity with gut commensals limits

specificity (12). Similarly,

galactomannan (GM) assays require pediatric-specific cutoffs [0.7

optimal density index (ODI) for serum in children <12 years vs.

0.5 ODI in adults] (13). Emerging

non-culture techniques, such as metagenomic next-generation

sequencing (mNGS), show promise but lack standardized validation in

children (14-18).

A 2024 study demonstrated that plasma mNGS achieved 89% sensitivity

and 94% specificity for diagnosing IFD in immunocompromised

pediatric patients, although sample contamination risks necessitate

clinical correlation (19).

Furthermore, the absence of age-adjusted diagnostic criteria for

IFD in children contributes to delayed treatment initiation,

exacerbating mortality risks in this vulnerable population

(20,21).

Pediatric IFD exhibits distinct epidemiological

patterns across regions. A French multicenter study involving 2,721

patients and spanning 2015 to 2018 reported a 5.3% IFD incidence

rate, but the generalizability may be limited by the predominantly

Caucasian population (82% of participants were of European descent)

and exclusion of transplant recipients with graft-vs. -host disease

(22,23). While the French cohort provides

valuable multicenter data, its sample size lacks power for subgroup

analyses of rare fungi such as Fusarium. Comparatively,

Chinese cohort data (with 4,192 patients) showed higher mold

predominance (73 vs. 42% in the French cohort), highlighting

regional ecological variations in fungal epidemiology (4). Pediatric IFD exhibits distinct

epidemiological patterns, with patients with AML and allogeneic

HSCT (allo-HSCT) showing the highest susceptibility (12.9 and 4.3%

incidence, respectively). Breakthrough infections under prophylaxis

remain a concern, particularly with prolonged neutropenia lasting

>14 days (24). The prevalence

of IFD in patients with pediatric hematological malignancies is

generally high, and granulocyte deficiency persisting for >10

days after chemotherapy is an independent risk factor associated

with combined IFD in pediatric hematological malignancies, while

granulocyte deficiency persisting for >14 days and not receiving

antifungal prophylaxis (AP) is an independent risk factor

associated with combined IFD in pediatric hematological

malignancies after allo-HSCT. A retrospective analysis of the

incidence of IFD in hematological neoplasms in children showed that

IFD was diagnosed in 75 (7.2%) of 1,047 children, with 15 cases of

candidemia (60% of these being non-Albicans) and 60 cases of

mold infections (55% of these being non-Aspergillus spp.),

and the mortality rate of IFD was 21.7%. Among hematological

malignancies, AML and ALL showed the highest incidence of IFD: In

pediatric patients with these malignancies who developed IFD, 89%

had severe neutropenia and 73% received high-intensity therapy

(25). A previous study analyzing

the epidemiology of IFD occurring in children with hematological

malignancies showed that among 471 at-risk patients (median age,

9.8 years) with hematological malignancies, 27 children experienced

28 IFD episodes. These included 5 cases of candidemia and 23 cases

of bronchopulmonary mycosis; additionally, 20 patients developed

breakthrough infections, 8 required intensive care and six

succumbed to the disease (26).

Rosen et al (14) analyzed

the incidence, site of infection and mortality of IFD in pediatric

patients with hematological malignancies, and retrospectively

analyzed the treatment of 1,052 children with hematological

malignancies from 1991 to 2001. In the pediatric hematological

malignancies cohort study, the incidence of IFD was 4.9%, with the

IFD incidence increasing from 2.9 to 7.8% from 1996 to 2001. Acute

leukemia (AL) cases in children accounted for 36% of cases, but the

incidence of IFD infection was as high as 67%. Candida spp.

were the main pathogens of IFD, with a decrease in infections

caused by Candida and an increase in Aspergillus

infections over time. A total of 62% of all patients who developed

infections did so during the neutropenic phase of

post-chemotherapy, which was 2.6-fold higher in patients with IFD.

IFD is a common complication during chemotherapy for AL in

children, and relevant studies are shown in Table I (20,24,27-30).

The adoption of pharmacological prophylaxis against

IFD pathogens is an effective means of addressing the risk of IFD

infection. AP is preferentially recommended for pediatric patients

with hematological malignancies with a risk of developing IFD

>10% such as patients with AML, relapsed leukemia or undergoing

allo-HSCT. However, with the widespread use of AP in pediatric

patients with hematological malignancies, there is also a need to

address the issue of breakthrough IFD (bIFD), which is defined as

invasive fungal infection occurring during antifungal exposure, as

per the European Confederation of Medical Mycology guidelines

(2020) (31). bIFD has become an

issue in patients receiving systemic antifungal medications, with

time to bIFD defined as the first attributable clinical sign or

symptom, mycological evidence finding or imaging feature. The

duration of bIFD is dependent on pharmacokinetic properties and

lasts at least until one dosing interval after discontinuation

(32). Despite intensified AP

after chemotherapy or allo-HSCT, bIFD remains a common complication

and cause of mortality after hematological malignancy treatment

(33). Risk factors for bIFD

include severe neutropenia, use of corticosteroids and prolonged

use of broad-spectrum antibiotics. The immunosuppressive state of

the body in children with hematological neoplasms undergoing

chemotherapy or post-transplantation directly contributes to the

likelihood of an increased risk of developing bIFD. The occurrence

of a bIFD can be fatal and early intervention may improve the

outcome of IFD (Fig. 1).

Persistent IFD is defined as IFD that remains unchanged and

continues to require antifungal therapy since the initiation of

treatment, and is distinct from refractory IFD, which is defined as

disease progression. Recurrent IFD occurs after treatment and is

caused by the same pathogen at the same site, but transmission may

also occur (34). Fungemia is

predominantly caused by Candida, whereas pulmonary IFD is

primarily due to filamentous fungi, notably Aspergillus, and

the widespread use of AP has increased the proportion of

non-Aspergillus filamentous fungi (35,36).

IFD is a common and serious complication after

allo-HSCT for hematological malignancies in children. The incidence

of IFD is gradually increasing and has become one of the causes of

mortality after transplantation (37,38),

highlighting the need for IFD to be diagnosed and treated as early

as possible (39,40). The occurrence of IFD is related to

factors such as neutrophil deficiency, T-cell dysfunction,

prolonged application of hormones or high-dose chemotherapy

pretreatment during transplantation. The lack major of specificity

of clinical features makes early diagnosis of IFD difficult and

once it occurs the prognosis is notably poor (23,41).

A study has shown that the incidence of Aspergillus exceeded

that of Candida among pathogens causing IFD in transplant

patients, and that IFD occurs mainly in the early and

mid-transplantation periods (42).

In the early stages of transplantation, generally ≥1 month after

transplantation, in patients with neutropenia, broad-spectrum

application of antibiotics and impaired mucosal barrier are the

main risk factors for the development of IFD, with

Aspergillus and Candida being the most common

pathogenic organisms. The mid-transplantation period comprises 2-3

months after transplantation, and the main risk factor for the

occurrence of IFD in this period is the application of

anti-graft-vs. -host disease (GVHD) therapy such as glucocorticoids

(43-45).

Patients in this period may have a combination of GVHD or

cytomegalovirus infection, and the highest percentage of

Aspergillus infections occurs at this time, with a notable

decrease in the percentage of Candida infections (46).

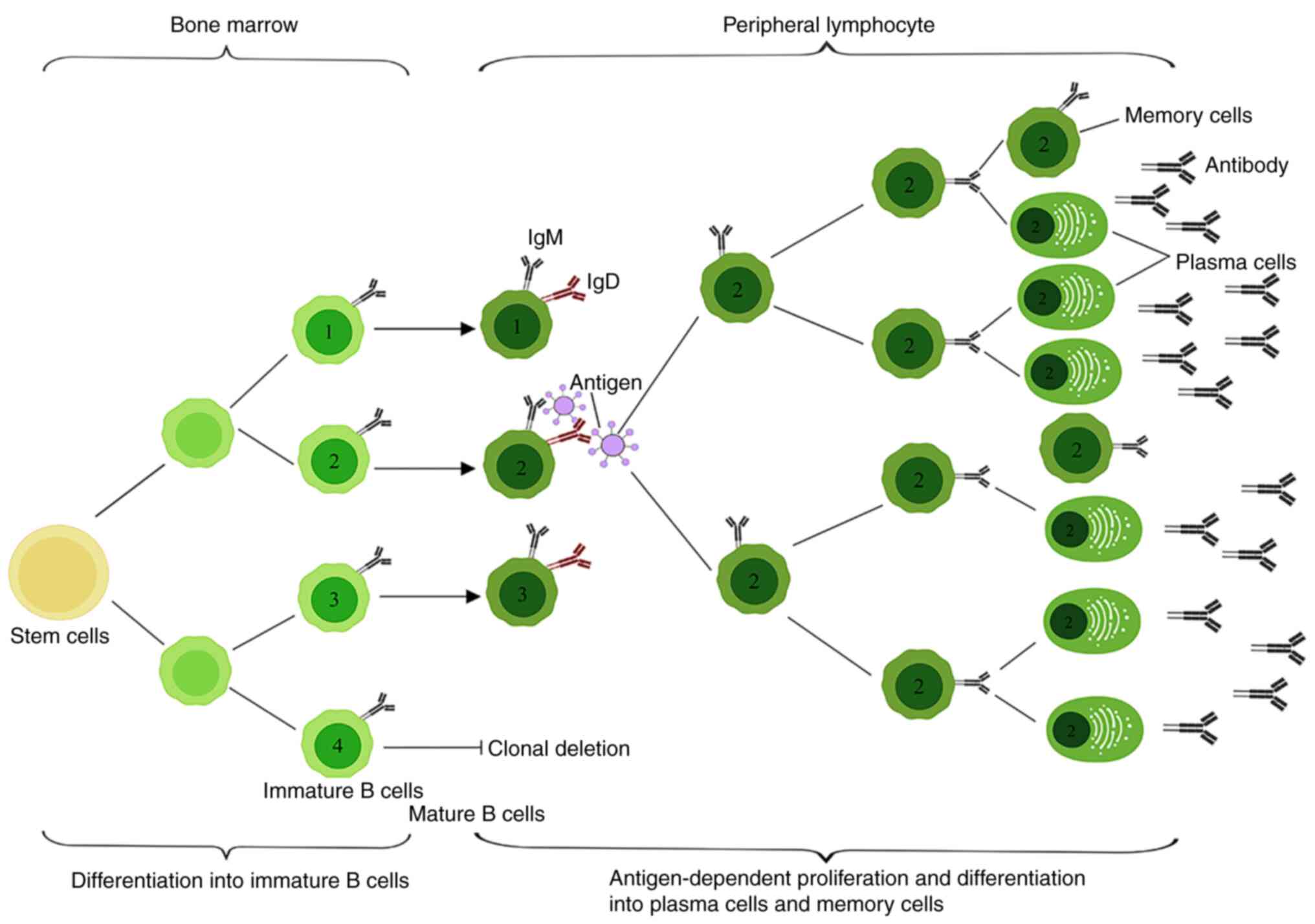

Late B-lymphocyte function after HSCT may take

months to years to fully return to normal; in this period, patients

are susceptible to infections and other complications during the

complex process of B-lymphocyte development, in which HTSCs

differentiate into lymphoid progenitor cells in the bone marrow,

further differentiate into pre-B and immature B cells and finally

develop into mature B cells (47,48).

Following HSCT, the recovery of myeloid lineage cells precedes the

reconstitution of lymphocytes, with B-cell development exhibiting a

delayed time course. B cells are characterized by their cytosolic

membrane surface expression of a variety of cytokine receptors

(such as IL-1, IL-2 and IL-4), which can be secreted by the

cytokines of T helper cells to produce a response (49,50).

Cytokines such as IL-2 and IL-4 promote B cell proliferation and

their subsequent differentiation into antibody-producing plasma

cells. Some of the proliferating B cells migrate to the medulla of

the lymphoid tissue and continue to proliferate and differentiate

to provide a defensive response to antibody production by plasma

cells, whereas some of the B cells and associated T cells migrate

to the nearby primary lymphoid follicle B cell region to continue

to proliferate and form secondary lymphoid follicles in the

germinal center (Fig. 2) (51,52).

The greater the intensity of transplantation preconditioning and

the more immunosuppressive agents applied, the greater the

possibility of IFD infection, and if a patient has a history of IFD

infection prior to transplantation, the risk of IFD infection

during transplantation is markedly increased (53).

In a prospective multicenter study analyzing

clinical data on combined IFD after chemotherapy or allo-HSCT for

hematological malignancies in children, a total of 304 children

were treated with chemotherapy or allo-HSCT, and 19 developed IFD,

including 10 cases of Aspergillus spp. and 5 cases of

Candida spp. that were confirmed. Among these patients, no

fatalities were attributed to IFD; however, in a subgroup of 8

patients who underwent allo-HSCT and developed IFD, 3 cases

resulted in mortality (54).

Invasive candidiasis is a common IFD in children

with hematological malignancies (55). This most commonly presents as

candidemia and liver and spleen infections, with the main clinical

symptoms being fever and other non-specific manifestations such as

fatigue and malaise or reduced appetite and weight loss. In

children with hematological malignancies and suspected invasive

candidiasis, if broad-spectrum antibiotics fail to improve clinical

symptoms (e.g., persistent fever), laboratory examinations for

fungal BDG should be performed to aid in the diagnosis (56). IFD occurring in the liver and

spleen sites upon fungal infections increase the incidence and

mortality after chemotherapy for hematological malignancies in

children (57,58). To the best of our knowledge, there

are insufficient data to support the optimal diagnosis of IFD at

the liver and spleen sites in children, and clinicians should be

alerted to the presence of persistent fever, back pain extending to

the shoulders, widespread muscle pain and elevated serum GM levels

in children with neutropenia after chemotherapy. In children with

prolonged neutropenic fever, early detection and diagnosis of IFD

in the liver and spleen should be recommended by abdominal

ultrasound and abdominal computed tomography (CT), even in the

absence of localized signs or symptoms (59). Invasive aspergillosis (IA) is the

most common type of infection in children after chemotherapy for

hematological malignancies, especially after allo-HSCT, and its

symptomatic presentation depends on the site of infection (60,61).

The most common site of infection in children with hematological

malignancies is the lower respiratory tract, which can cause

Aspergillus bronchitis and pneumonia, followed by nasal

infections and central nervous system (CNS) infections. Common

symptoms of respiratory Aspergillus infections include cough

and dyspnea, brownish-black mucus plugs in some patients and

coughing up blood in severe cases (62). CNS Aspergillus infections

may present with unusual headaches, seizures and severe loss of

consciousness. However, it can be difficult to recognize IA early

in children, as they may present initially with only non-specific

signs such as fever, which can obscure or precede the development

of more specific neurological symptoms. In CNS fungal infections,

Aspergillus spp. are the most common pathogens, and tests

such as magnetic resonance imaging are difficult to use for

diagnosis: By contrast, detecting fungal antigens such as GM or BDG

or early diagnosis by molecular detection of fungal nucleic acids

are preferred (63). In a

multicenter retrospective study, 51 children with AL combined with

CNS fungal infections were analyzed, of whom six patients underwent

HSCT and 17 were clinically diagnosed by combining typical imaging

manifestations of fungal infections of the CNS with positive

microbial results in the cerebrospinal fluid or a positive BDG or

GM assay. The proposed diagnosis was made in 34 cases with only

typical imaging manifestations of fungal infections of the CNS. The

median time from fever to diagnosis was 5 days for all patients,

and the most common fungal pathogen was Aspergillus spp. In

total, 16 patients received monotherapy and 35 received combination

antifungal therapy, whereas 23 patients underwent surgery. A total

of 22 patients eventually succumbed to the disease, and 10 other

patients had neurological sequelae. Early diagnosis and prompt

treatment of childhood AL combined with fungal infections of the

CNS, either antifungal therapy or surgery, are essential to improve

clinical outcomes (64).

Diagnosing pediatric IFD requires overcoming three

key barriers: i) Overlapping symptoms with bacterial infections;

ii) lower sensitivity of GM assays in children compared with

adults; and iii) invasive procedures being less feasible in young

patients. Emerging non-culture techniques such as mNGS show promise

but require pediatric-specific validation (67). Laboratory diagnostic methods for

IFD include traditional fungal tests such as microscopic smear

microscopy, culture and histopathological examination, as well as

laboratory diagnostic tools such as the BDG and GM assays. The BDG

assay detects cell wall components of fungi, such as the

polysaccharide component of the cell wall of yeast-like fungi. The

cell wall component, BDG is a component of numerous pathogenic

fungi, and it is widely used as a diagnostic tool in clinical

practice in assay form, including in children and neonates

(68,69).

The diagnosis of IFD can be categorized into four

levels: Confirmed, clinically diagnosed, proposed and undetermined.

When the condition of a patient is critical and histopathological

biopsy is limited, the diagnosis of IFD consists of host factors

(for example, severe immunodeficiency), clinical manifestations and

microbiological basis for confirmation of the diagnosis in addition

to host factors and identifying microorganisms in the

histopathology (73). The basis

for the proposed diagnosis requires a host factor and a major

clinical manifestations, especially typical imaging basis and a

laboratory basis for the diagnosis of IFD diagnostic grading to the

clinical diagnosis (74). For

instance, the BDG/GM assay demonstrates high sensitivity in

diagnosing pulmonary IFD; a positive BDG/GM result, combined with

definitive lung imaging findings, supports a clinical diagnosis of

IFD. Confirmatory diagnosis requires fiberoptic bronchoscopy with

lavage or tissue biopsy for pathological examination, when feasible

(75).

The consensus on IFD was revised and updated by the

European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer and the

Fungal Disease Research Group Education and Research Federation in

2020(31). This consensus suggests

that there has been a marked increase in evidence for using GM to

diagnose IFDs such as IA, and the detection of BDG assay should

also be expanded to a wider range of patients. At present, an

increasing number of fungal PCR have undergone considerable

standardization, coupled with the availability of commercial

analysis, external quality assessment schemes and a large quantity

of performance validation data, which can be widely used for

screening and diagnosing IFDs (76). Molecular diagnostics exhibit

pediatric-specific characteristics: Fungal PCR achieves 92%

sensitivity in children using whole blood samples (minimum volume,

3 ml), compared with 78% with serum samples, reflecting higher

fungal burdens in pediatric hematological malignancies (77). mNGS shows superior performance in

pediatric pulmonary IFD, with 15% higher detection rates compared

with adults, although environmental fungal DNA contamination may

cause false positives in 8-12% of cases (67,78).

For infections caused by Aspergillus, Candida and

Pneumocystis jirovecii, PCR testing combined with

serological assays is recommended to enhance diagnostic accuracy

(77).

IFD often involves the lower respiratory tract and

fungemia, among which, lung infection is the most common (79). Chest CT performance is complex and

varied, generally manifested as nodular or a patchy shadow.

Ocassionally, a typical halo or crescent sign can be observed,

which is a relatively more characteristic change (80). Some patients may present

non-characteristic changes in the early stage of the disease, such

as bronchial dilatation sign, buds sign, hairy glass shadow, solid

shadow and tiny nodular shadow (81). Ground glass shadows are notable for

early diagnosis and are characteristic of Aspergillus airway

infiltration. It is also important to note that new signs of

infiltration on CT imaging should also be considered, and early use

of effective antifungal medications is a key factor in good

control. IFD is difficult to diagnose early due to the lack of

diagnostic indicators with high specificity and sensitivity

(82). In patients with

hematological malignancies, the presence of characteristic imaging

changes in the lungs combined with a positive specific BDG/GM assay

can clinically confirm the diagnosis. Since BDG is widely present

in fungal cell walls, the BDG assay is not effective in

differentiating Aspergillus from Candida (21), whereas the GM assay is mostly used

to carry out the diagnosis of Aspergillus infections

(70).

Invasive trichothecenes are common in children after

chemotherapy for hematological malignancies, especially after HSCT.

The clinical manifestations of trichothecenes are varied and depend

mainly on the site of infection, which is commonly skin, nasal and

lung infections (83). A previous

multicenter study was conducted to analyze the characteristics of

hematological malignancies involving trichothecenes in children. In

a cohort of 39 pediatric patients with combined trichothecenes, 92%

of trichothecene cases occurred in patients with AL, with a notable

association with high-risk ALL and advancing age, and a total of 15

patients (38%) succumbed to trichothecenes (84). Pulmonary mucormycosis may cause

non-specific segmental or lobar bronchopneumonia with cavitation

similar to aspergillosis and imaging may help to determine the

extent of mucormycosis infection (85,86).

Current serological testing for the diagnosis of trichophytosis is

limited and usually relies on clinical presentation, tissue biopsy

or culture results for diagnosis and PCR can assist in identifying

the pathogen (87).

IFD treatment using drugs can be categorized into

monotherapy and combination therapy according to the presence or

absence of clinical manifestations at the beginning of treatment in

patients with high-risk factors, as well as the type and outcome of

obtaining a diagnostic basis for IFD (88). The choice of therapeutic agents is

based on a combination of factors, including condition of the

patient, the local epidemiology of the fungus, previous antifungal

therapy, and drug metabolism and sensitization results. IFD risk

factors should be considered in clinical practice, and the

increasing age of children should also be taken into account when

assessing IFD risk (89). IFD

treatment strategies can be categorized as preventive, empirical,

diagnosis-driven or targeted. IFD needs to be treated aggressively

due to its diverse clinical manifestations and high mortality rate,

which notably affects the efficacy of chemotherapy (90). Common first-line antifungal agents

for treating IFD include voriconazole injection, itraconazole

injection, caspofungin and amphotericin B (91,92).

These agents may be administered as monotherapy or in combination

regimens, such as voriconazole with caspofungin, voriconazole with

amphotericin B or caspofungin with amphotericin B (93,94).

Previous studies on the treatment of pediatric hematological

malignancies combined with IFD are shown in Table II (95-99).

Prophylaxis includes primary prevention and

re-prophylaxis. Primary prophylaxis refers to the pre-application

of antifungal medications in patients with risk factors for IFD

before the patients develop symptoms of infection, with recommended

medications such as posaconazole, fluconazole, itraconazole and

voriconazole. Posaconazole, micafungin, fluconazole, itraconazole,

voriconazole and caspofungin are recommended for patients

undergoing allo-HSCT transplantation (100). Posaconazole is a triazole

antifungal drug that is available as an intravenous solution, oral

suspension and extended-release tablets, with the oral suspension

being the preferred formulation for pediatric use (101). Micafungin is an intravenous

echinocandin with activity against Candida and

Aspergillus spp; it has a favorable safety profile compared

with other antifungal drugs and is one of the more desirable

options for IFD prophylaxis of hematological malignancies in

children. Secondary prophylaxis refers to the administration of

antifungal medications to prevent recurrence of IFD in patients

with a prior history of confirmed or clinically diagnosed IFD who

are being treated again with chemotherapy or HSCT. Re-prophylaxis

recommended medications are preferred to those effective on

previous antifungal therapy, at the same dosage as for primary

prevention. This is due to the fact that the pathogen may have

developed resistance or tolerance to previously used antifungal

agents, and maintaining the same dosage ensures therapeutic

efficacy while minimizing the risk of suboptimal exposure that

could promote further resistance (102-104).

Additionally, consistent dosing simplifies clinical management and

reduces errors in high-risk populations such as allo-HSCT

recipients (105). The course of

prophylactic therapy is largely dependent on the improvement of the

risk factors of the patient for IFD and generally covers ≥3 months

post-transplantation in patients undergoing HSCT. In a prospective

study comparing caspofungin with fluconazole for the prevention of

IFD during post-chemotherapy neutropenia in children, adolescents

and young adults with AML, there were 23 cases of comorbid IFD in

517 patients, including 6 cases of caspofungin and 17 cases of

comorbid IFD after fluconazole prophylaxis and the pathogenic

organisms included 14 species of molds, seven species of yeasts and

two species of unclassified fungi. The cumulative incidence of IFD

was 0.5% in the caspofungin group and 3.1% in the fluconazole group

(106).

Empirical treatment is generally defined as

persistent granulocyte deficiency with fever after chemotherapy in

children and ineffective treatment with broad-spectrum antibiotics

for 4-7 days as the main criteria for initiating treatment

(107). Risk factors for IFD

after chemotherapy in children at high risk for hematological

malignancies should be one of the following: i) Expected absolute

neutrophil count <0.1x109/l for >7 days; ii)

development of hemodynamically unstable clinical comorbidities;

iii) oral or gastrointestinal mucositis and dysphagia; iv)

intravascular catheter infections; v) new-onset pulmonary

infiltrates or hypoxemia; and vi) hepatic insufficiency or renal

insufficiency (108,109). The pathogens of IFD in pediatric

hematological malignancies are predominantly Aspergillus;

thus, broad-spectrum antibiotics covering Aspergillus are

generally selected, and empirical treatment of IFD starting with

fever after chemotherapy for pediatric hematological malignancies

without any microbiological or imaging evidence is aimed at early

initiation of antifungal agents to reduce the morbidity and

mortality associated with IFD, this has become a standard of care

in the clinic (110). Empirical

treatment should be accompanied by an active search for infectious

lesions, microbiological and imaging tests, such as fungal

cultures, non-culture microbiological tests and chest CT, as well

as tests such as bronchoscopy or biopsy when the condition of the

patient permits, in order to facilitate the diagnosis of IFD and

the adjustment of empirical treatment (111). For febrile neutropenia after

chemotherapy for hematological malignancies in children, most

centers prefer empiric treatment, and the recommended drugs for

empiric treatment are itraconazole, caspofungin, micafungin,

liposomal amphotericin B, amphotericin B and voriconazole.

First-line treatment for candidemia includes fluconazole or

liposomal amphotericin B, while voriconazole is the first-line

treatment for IA (112,113).

Diagnosis-driven treatment refers to the combination

of clinical imaging markers of IFD such as the presence of

Aspergillus infection-related imaging changes on lung CT and

microbiological markers such as a positive BDG/GM assay, positive

fungal culture or microscopic examination of specimens obtained

from non-sterile sites or non-sterile manipulations in pediatric

hematological malignancies patients after chemotherapy; this is in

the absence of clinical symptoms of infection, or in the presence

of a persistent neutrophilic deficiency fever ineffective on

treatment with a broad-spectrum antibiotics. For low-risk patients

with IFD, empiric antifungal therapy, which is also

diagnosis-driven therapy, is recommended in the presence of a

diagnostic basis for IFD such as clinical imaging abnormalities or

a positive serum BDG/GM assay (114).

Comparative analyses reveal distinct

pathophysiological features between pediatric and adult IFD:

Pediatric patients exhibit increased serum BDG levels (median 120

vs. 80 pg/ml in adults) and delayed GM antigenemia positivity

(median 5 vs. 3 days post-symptom onset), contributing to

diagnostic challenges unique to children (21,70).

Notably, CNS involvement occurs in 38% of pediatric IFD cases vs.

12% in adults, with Aspergillus predominating in both groups

but showing increased mucormycosis prevalence in pediatric AML (7.2

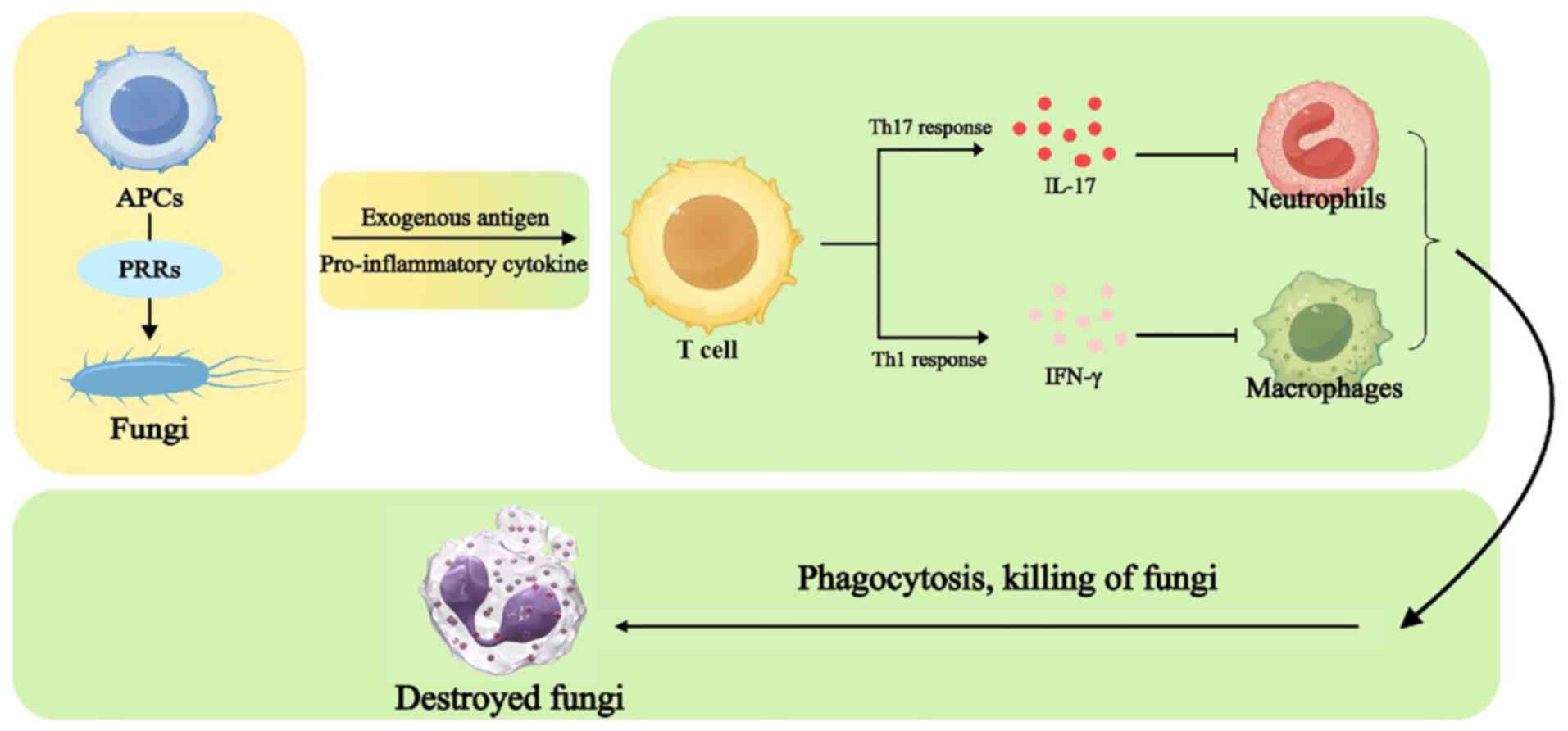

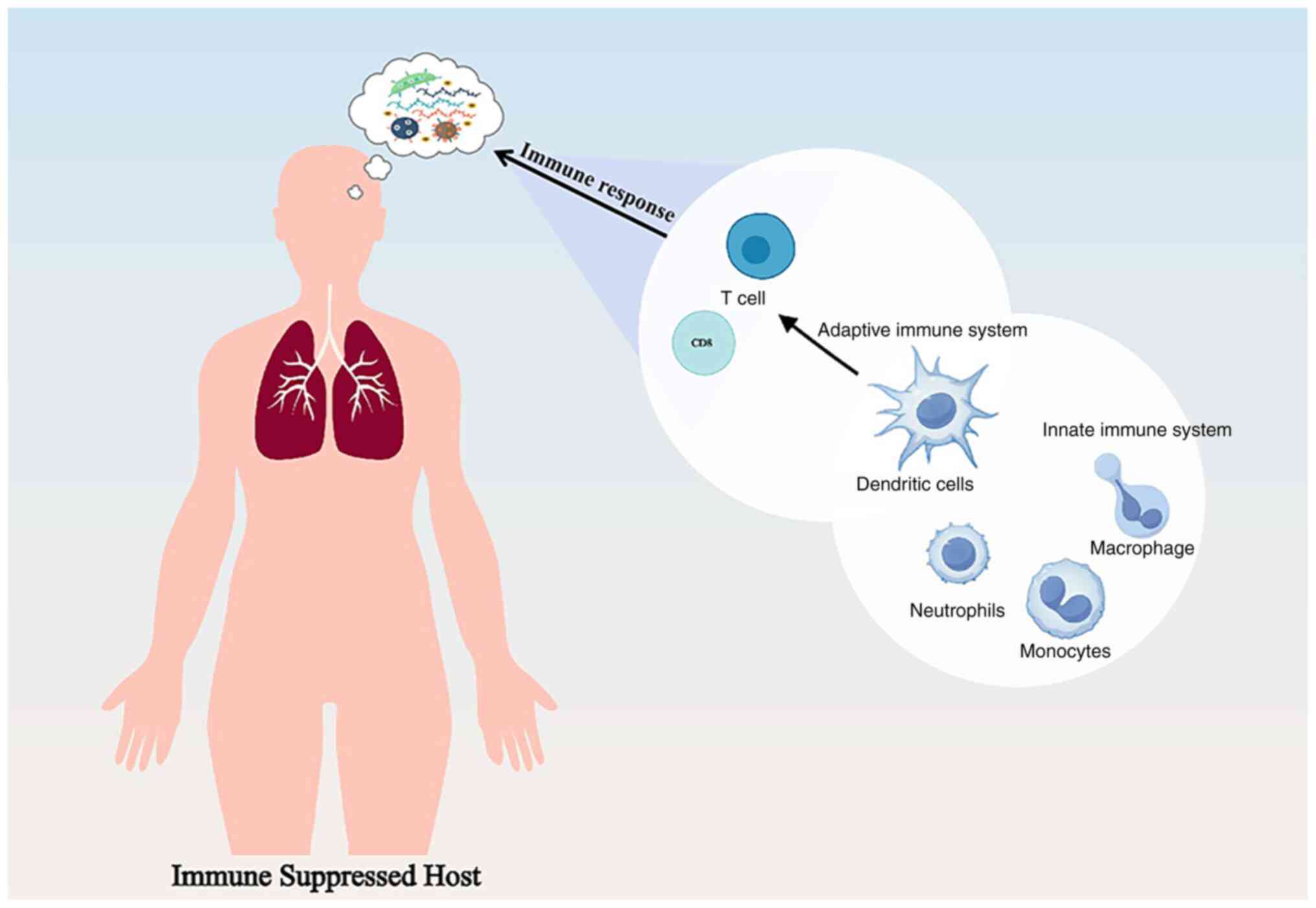

vs. 2.1%) (64,84). IFDs are rare in individuals with

intact immune systems; however, children who have relatively low

immunity are susceptible to IFD. In response to IFD innate and

adaptive immune responses, several pattern recognition receptors on

antigen-presenting cells (APCs) recognize the fungus. Exogenous

antigens and proinflammatory cytokines presented by APCs promote

T-cell activation; secretion of IL-17 by T helper (Th)17 cells

promote the production of chemokines recruited by neutrophils.

Interferon γ induced by Th1 cells activates macrophages, which,

together with neutrophils, phagocytose and kill the fungus. The

mechanisms of innate and adaptive immune responses in IFD are shown

in Fig. 3. This may be one of the

main reasons why children with low immune function are at risk of

IFD. The heightened vulnerability of immunocompromised children

stems from specific defects in both innate and adaptive immune

responses. For instance, neutrophils from pediatric patients

post-HSCT exhibit impaired phagocytic capacity and reduced

oxidative burst activity compared with healthy controls (118).

IFD in pediatric patients with hematological

malignancies undergoing chemotherapy or HSCT presents three major

clinical dilemmas: The higher prevalence of IFD in specific

subgroups, non-specific manifestations complicating early diagnosis

and the emergence of breakthrough infections during prophylaxis or

therapy. First, for the IFD prevalence profile, which is higher in

children with AML and allo-HSCT combined with IFD, this group of

patients requires further clinical attention and therapeutic

management. Second, the clinical presentation increases the

difficulty of diagnosing and treating IFD; common symptoms of IFD,

including fever, cough and dyspnea, exhibit non-specific

characteristics that overlap with bacterial or viral infections.

Furthermore, bIFD can develop during AP or therapy as a consequence

of pathogen profile shifts or resistance evolution (119). The management of bIFD in

immunocompromised children presents multifaceted challenges.

Diagnostic complexity is exacerbated under AP. Conventional

biomarkers such as BDG may lose specificity due to cross-reactivity

with gut commensals, while tissue sampling is often delayed by

thrombocytopenia and bleeding risks (22).

Therapeutic strategies diverge markedly between

populations: Pediatric IFD requires 30% higher voriconazole doses

compared with adult doses, to achieve therapeutic trough levels,

while echinocandin clearance is 1.5-fold faster in children

necessitating weight-adjusted dosing (101,116). Combination therapy shows superior

outcomes in pediatric cohorts compared with adults, particularly

for CNS infections where blood-brain barrier penetration differs

developmentally (122).

Specifically, voriconazole demonstrates non-linear pharmacokinetics

in children <12 years, requiring 30-50% increased

weight-adjusted doses than adults to achieve therapeutic trough

levels (2-6 mg/l) (101,123). Similarly, posaconazole exhibits

40% lower bioavailability in pediatric patients compared with

adults, necessitating therapeutic drug monitoring (13,19).

Implementation of first-line prophylaxis has yielded notable

protective effects, and early diagnosis and prompt treatment,

including antifungals and surgery, are key to improving patient

survival. The use of new diagnostic techniques has helped in the

rapid clinical identification of the causative fungus and the

timely development of therapeutic strategies. The role of early and

accurate diagnosis in the initial stages of active containment of

fungal infections has become critical in preventing the development

of life-threatening conditions. The growing clinical demands in

medical mycology have catalyzed a diagnostic evolution from

conventional microscopy and culture-based methods to advanced

non-culture platforms. A total of four cutting-edge approaches,

namely mNGS, novel PCR systems, next-generation biosensors and

nanotechnology-enhanced tools, collectively demonstrate superior

pathogen detection capabilities (124-126).

These innovations address critical limitations of traditional

isolation techniques, including suboptimal sensitivity and

culturability constraints (67).

Diagnostic advancements highlight age-specific considerations; mNGS

exhibits 92% sensitivity in pediatric pulmonary IFD vs. 78% in

adults, which is attributable to higher fungal burden in children

(67). Conversely, the specificity

of GM assay drops to 67% in children <5 years due to

cross-reacting dietary GMs, compared with 89% in older populations

(10). These differences

underscore the need for pediatric-specific diagnostic

algorithms.

In terms of antifungal regimen selection,

itraconazole, voriconazole, amphotericin B and caspofungin are

generally selected for patients in whom Candida is the

primary source of infection. For Aspergillus infections,

voriconazole continues to be used as the preferred regimen. When

comparing caspofungin monotherapy and voriconazole combination

therapy, voriconazole monotherapy or in combination with

caspofungin resulted in a markedly lower IFD-related mortality

compared with caspofungin monotherapy (122). The selection between monotherapy

and combination antifungal therapy requires consideration of

multiple factors, where infection characteristics carry out a key

role; for example, pulmonary involvement favors voriconazole

monotherapy (127).

Trichophytosis is a rare but emerging life-threatening fungal

disease with limited therapeutic options (128), and the novel antifungal agent

esaconazole, a new triazole, has demonstrated efficacy in both

initial and salvage treatment of trichophytosis in adults and

children, offering more effective therapeutic options for

trichophytosis and other fungal infections (129,130). There is an increasing number of

novel antifungal agents that may be used in the future for

pediatric hematological malignancies during chemotherapy or after

allo-HSCT, such as encochleated amphotericin B deoxycholate,

isavuconazole, olorofim, opelconazole, oteseconazole, fosmanogepix,

ibrexafungerp and rezafungin (13,19).

Early diagnosis and effective treatment of IFD after

chemotherapy and HSCT for pediatric hematological malignancies

requires multiple tools to overcome clinical challenges and improve

patient prognosis. Literature analysis shows that, compared with

bacterial and viral infections, chemotherapy for hematological

malignancies in children combined with IFD only accounts for a

minority of cases, but its impact may be much more severe,

especially in cases where long-term antifungal therapy or even

surgical treatment is required to eradicate colonization (27,131,132). A personalized approach is

recommended, as pediatric patients with hematological malignancies

usually present with different comorbidities that require

tailor-made treatments (133).

Pediatric hematological malignancies, particularly patients with

AML and relapsed patients, are prone to IFD, and the major

challenges facing physicians include the diversity of pathogenic

organisms, the difficulty of early identification and diagnosis,

and the efficacy and safety of drug therapy.

While the present review synthesizes current

evidence on IFD management in pediatric hematological malignancies,

several limitations warrant acknowledgment. First, the majority of

the included studies are retrospective, introducing potential

selection bias and heterogeneity in diagnostic criteria across

centers. Second, pediatric-specific pharmacokinetic data remain

scarce for newer antifungals such as isavuconazole and rezafungin

(13,19). Third, the diagnostic accuracy of

biomarkers (BDG/GM assay) shows notable inter-study variability in

pediatric cohorts (sensitivity range, 62-89%), reflecting unmet

standardization needs (70,72).

These gaps highlight the necessity for prospective multicenter

studies using harmonized protocols. Further research and clinical

practice are needed to advance multiple domains, including the

development of novel antifungal agents, enhancement of

pharmacological prophylaxis strategies, optimization of rapid

pathogen detection methods and exploration of more effective

infection control strategies.

The management of IFD in pediatric hematological

malignancies post-chemotherapy and allo-HSCT remains a key

challenge, necessitating a multifaceted approach to optimize

outcomes. The present review underscores that children with AML and

those undergoing allogeneic HSCT face increased susceptibility to

IFD due to severe immunosuppression, with innate and adaptive

immune dysregulation exacerbating fungal pathogenicity. The

non-specific clinical manifestations of IFD, overlapping with

bacterial or viral infections, coupled with the pathogen diversity

and frequent emergence of breakthrough infections, necessitate

advancements in diagnostic precision.

Emerging non-culture-based diagnostic modalities,

including mNGS and nanotechnology-enhanced assays, offer high

resolution in pathogen identification, enabling timely and targeted

therapeutic interventions; however, challenges such as lack of

standardization, high costs and complex result interpretation

persist (134). For instance,

mNGS may yield false positives due to sample contamination in

immunocompromised hosts, necessitating integration with

conventional culture and clinical context. While voriconazole

retains its primacy in treating Aspergillus infections,

combination therapies (such as voriconazole with caspofungin)

demonstrate marked mortality reduction compared with monotherapy.

Novel antifungals, including esaconazole and rezafungin, expand the

therapeutic arsenal, particularly for refractory cases such as

trichophytosis, although their pediatric-specific safety and

efficacy profiles warrant further validation (135,136).

The present review has several limitations: First,

the heterogeneity in study designs (namely, high proportion of

retrospective studies) may affect result consistency; second, some

data derive from single-center studies with limited sample

representativeness; and third, rare pathogens or special

populations (such as congenital immunodeficiency) were not deeply

analyzed. Therefore, future multicenter prospective studies are

warranted to validate conclusions. Future efforts should prioritize

the development of pediatric-optimized antifungals, enhanced

pharmacovigilance frameworks and scalable rapid diagnostics to

address the persistent gaps in managing this life-threatening

complication. Ultimately, linking basic research, translational

medicine and clinical practice is essential to redefine the

diagnostic and therapeutic criteria for IFD in pediatric

haemato-oncology. A key unmet need is pediatric-focused

pharmacokinetic studies on antifungal agents. Current dosing

regimens for novel antifungals such as isavuconazole and rezafungin

are primarily extrapolated from adult data, despite documented

age-dependent variations in drug metabolism. Future research should

establish age-stratified dosing guidelines through prospective

multicenter trials incorporating population pharmacokinetic

modeling.

Not applicable.

Funding: The present review was supported by the Municipal

Financial Subsidy of Nanshan District Medical Key Discipline

Construction, Shenzhen Nanshan District Health System Science and

Technology Major Project (grant no. NSZD2023018) and the National

Health Commission Key Laboratory of Nuclear Technology Medical

Transformation (Mianyang Central Hospital; grant no.

2023HYX033).

Not applicable.

The present review was conceptualized by MH, FC and

XX. The original draft was written by MH. Writing, reviewing and

editing of the manuscript content was performed by ZG. The present

work was supervised by ZG, who also acquired funding. All authors

have read and approved the final manuscript. Data authentication is

not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

|

1

|

Adzic-Vukicevic T, Mladenovic M, Jovanovic

S, Soldatović I and Radovanovic-Spurnic A: Invasive fungal disease

in COVID-19 patients: A single-center prospective observational

study. Front Med (Lausanne). 10(1084666)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Liu Q, Chen P, Xin L, Zhang J and Jiang M:

A rare intestinal mucormycosis caused by Lichtheimia ramosa in a

patient with diabetes: A case report. Front Med (Lausanne).

11(1435239)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Mori G, Diotallevi S, Farina F, Lolatto R,

Galli L, Chiurlo M, Acerbis A, Xue E, Clerici D, Mastaglio S, et

al: High-Risk neutropenic fever and invasive fungal diseases in

patients with hematological malignancies. Microorganisms.

12(117)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Sun Y, Huang H, Chen J, Li J, Ma J, Li J,

Liang Y, Wang J, Li Y, Yu K, et al: Invasive fungal infection in

patients receiving chemotherapy for hematological malignancy: A

multicenter, prospective, observational study in China. Tumour

Biol. 36:757–767. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Li C, Zhu DP, Chen J, Zhu XY, Li NN, Cao

WJ, Zhang ZM, Tan YH, Hu XX, Yuan HL, et al: Invasive fungal

disease in patients undergoing allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell

transplantation in China: A multicenter epidemiological study

(CAESAR 2.0). Clin Infect Dis. 80:807–816. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Schmiedel Y and Zimmerli S: Common

invasive fungal diseases: An overview of invasive candidiasis,

aspergillosis, cryptococcosis, and Pneumocystis pneumonia.

Swiss Med Wkly. 146(w14281)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Richardson M and Lass-Flörl C: Changing

epidemiology of systemic fungal infections. Clin Microbiol Infect.

14 (Suppl 4):S5–S24. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Zabolinejad N, Naseri A, Davoudi Y, Joudi

M and Aelami MH: Colonic basidiobolomycosis in a child: Report of a

culture-proven case. Int J Infect Dis. 22:41–43. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Huppler AR, Fisher BT, Lehrnbecher T,

Walsh TJ and Steinbach WJ: Role of molecular biomarkers in the

diagnosis of invasive fungal diseases in children. J Pediatric

Infect Dis Soc. 6 (Suppl 1):S32–S44. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Fisher BT, Westling T, Boge CLK, Zaoutis

TE, Dvorak CC, Nieder M, Zerr DM, Wingard JR, Villaluna D,

Esbenshade AJ, et al: Prospective evaluation of galactomannan and

(1→3) β-d-glucan assays as diagnostic tools for invasive fungal

disease in children, adolescents, and young adults with acute

myeloid leukemia receiving fungal prophylaxis. J Pediatric Infect

Dis Soc. 10:864–871. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Huang J, Liu C and Zheng X: Clinical

features of invasive fungal disease in children with no underlying

disease. Sci Rep. 12(208)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Lehrnbecher T, Hassler A, Groll AH and

Bochennek K: Diagnostic approaches for invasive

aspergillosis-specific considerations in the pediatric population.

Front Microbiol. 9(518)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Zimmermann P, Brethon B, Roupret-Serzec J,

Caseris M, Goldwirt L, Baruchel A and de Tersant M: Isavuconazole

treatment for invasive fungal infections in pediatric patients.

Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 15(375)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Rosen GP, Nielsen K, Glenn S, Abelson J,

Deville J and Moore TB: Invasive fungal infections in pediatric

oncology patients: 11-year experience at a single institution. J

Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 27:135–140. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Blauwkamp TA, Thair S, Rosen MJ, Blair L,

Lindner MS, Vilfan ID, Kawli T, Christians FC, Venkatasubrahmanyam

S, Wall GD, et al: Analytical and clinical validation of a

microbial cell-free DNA sequencing test for infectious disease. Nat

Microbiol. 4:663–674. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Schlaberg R, Chiu CY, Miller S, Procop GW

and Weinstock G: Professional Practice Committee and Committee on

Laboratory Practices of the American Society for Microbiology;

Microbiology Resource Committee of the College of American

Pathologists. Validation of metagenomic next-generation sequencing

tests for universal pathogen detection. Arch Pathol Lab Med.

141:776–786. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Agudelo-Pérez S, Fernández-Sarmiento J,

Rivera León D and Peláez RG: Metagenomics by next-generation

sequencing (mNGS) in the etiological characterization of neonatal

and pediatric sepsis: A systematic review. Front Pediatr.

11(1011723)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Wilke J, Ramchandar N, Cannavino C, Pong

A, Tremoulet A, Padua LT, Harvey H, Foley J, Farnaes L and Coufal

NG: Clinical application of cell-free next-generation sequencing

for infectious diseases at a tertiary children's hospital. BMC

Infect Dis. 21(552)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Hsu AJ, Hanisch BR, Fisher BT and Huppler

AR: Pipeline of novel antifungals for invasive fungal disease in

transplant recipients: A pediatric perspective. J Pediatric Infect

Dis Soc. 13 (Suppl 1):S68–S79. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Ávila Montiel D, Saucedo Campos A, Avilés

Robles M, Murillo Maldonado MA, Jiménez Juárez R, Silva Dirzo M and

Dorantes Acosta E: Fungal infections in pediatric patients with

acute myeloid leukemia in a tertiary hospital. Front Public Health.

11(1056489)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Otto WR, Dvorak CC, Boge CLK,

Ostrosky-Zeichner L, Esbenshade AJ, Nieder ML, Alexander S,

Steinbach WJ, Dang H, Villaluna D, et al: Prospective evaluation of

the fungitell® (1→3) beta-D-glucan assay as a diagnostic

tool for invasive fungal disease in pediatric allogeneic

hematopoietic cell transplantation: A report from the children's

oncology group. Pediatr Transplant. 27(e14399)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Olivier-Gougenheim L, Rama N, Dupont D,

Saultier P, Leverger G, AbouChahla W, Paillard C, Gandemer V,

Theron A, Freycon C, et al: Invasive fungal infections in

immunocompromised children: Novel insight following a national

study. J Pediatr. 236:204–210. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Fisher BT, Robinson PD, Lehrnbecher T,

Steinbach WJ, Zaoutis TE, Phillips B and Sung L: Risk factors for

invasive fungal disease in pediatric cancer and hematopoietic stem

cell transplantation: A systematic review. J Pediatric Infect Dis

Soc. 7:191–198. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Yeoh DK, Moore AS, Kotecha RS, Bartlett

AW, Ryan AL, Cann MP, McMullan BJ, Thursky K, Slavin M, Blyth CC,

et al: Invasive fungal disease in children with acute myeloid

leukaemia: An Australian multicentre 10-year review. Pediatr Blood

Cancer. 68(e29275)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Mor M, Gilad G, Kornreich L, Fisher S,

Yaniv I and Levy I: Invasive fungal infections in pediatric

oncology. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 56:1092–1097. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Calle-Miguel L, Garrido-Colino C,

Santiago-García B, Moreno Santos MP, Gonzalo Pascual H, Ponce Salas

B, Beléndez Bieler C, Navarro Gómez M, Guinea Ortega J and

Rincón-López EM: Changes in the epidemiology of invasive fungal

disease in a Pediatric hematology and oncology unit: The relevance

of breakthrough infections. BMC Infect Dis. 23(348)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Lin GL, Chang HH, Lu CY, Chen CM, Lu MY,

Lee PI, Jou ST, Yang YL, Huang LM and Chang LY: Clinical

characteristics and outcome of invasive fungal infections in

pediatric acute myeloid leukemia patients in a medical center in

Taiwan. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 51:251–259. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Sezgin Evim M, Tüfekçi Ö, Baytan B, Ören

H, Çelebi S, Ener B, Üstün Elmas K, Yılmaz Ş, Erdem M,

Hacımustafaoğlu MK and Güneş AM: Invasive fungal infections in

children with leukemia: Clinical features and prognosis. Turk J

Haematol. 39:94–102. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Tüfekçi Ö, Yılmaz Bengoa Ş, Demir

Yenigürbüz F, Şimşek E, Karapınar TH, İrken G and Ören H:

Management of invasive fungal infections in pediatric acute

leukemia and the appropriate time for restarting chemotherapy. Turk

J Haematol. 32:329–337. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Lehrnbecher T, Groll AH, Cesaro S, Alten

J, Attarbaschi A, Barbaric D, Bodmer N, Conter V, Izraeli S, Mann

G, et al: Invasive fungal diseases impact on outcome of childhood

ALL-an analysis of the international trial AIEOP-BFM ALL 2009.

Leukemia. 37:72–78. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Donnelly JP, Chen SC, Kauffman CA,

Steinbach WJ, Baddley JW, Verweij PE, Clancy CJ, Wingard JR,

Lockhart SR, Groll AH, et al: Revision and update of the consensus

definitions of invasive fungal disease from the european

organization for research and treatment of cancer and the mycoses

study group education and research consortium. Clin Infect Dis.

71:1367–1376. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Jenks JD, Cornely OA, Chen SC, Thompson GR

III and Hoenigl M: Breakthrough invasive fungal infections: Who is

at risk? Mycoses. 63:1021–1032. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Liberatore C, Farina F, Greco R, Giglio F,

Clerici D, Oltolini C, Lupo Stanghellini MT, Barzaghi F, Vezzulli

P, Orsenigo E, et al: Breakthrough invasive fungal infections in

allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. J Fungi

(Basel). 7(347)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Cornely OA, Hoenigl M, Lass-Flörl C, Chen

SC, Kontoyiannis DP, Morrissey CO and Thompson GR III: Mycoses

Study Group Education and Research Consortium (MSG-ERC) and the

European Confederation of Medical Mycology (ECMM). Defining

breakthrough invasive fungal infection-position paper of the

mycoses study group education and research consortium and the

European confederation of medical mycology. Mycoses. 62:716–729.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Arendrup MC, Arikan-Akdagli S, Jørgensen

KM, Barac A, Steinmann J, Toscano C, Arsenijevic VA, Sartor A,

Lass-Flörl C, Hamprecht A, et al: European candidaemia is

characterised by notable differential epidemiology and

susceptibility pattern: Results from the ECMM Candida III

study. J Infect. 87:428–437. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Marín Martínez EM, Aller García AI and

Martín-Mazuelos E: Epidemiology, risk factors and in vitro

susceptibility in candidaemia due to non-Candida albicans

species. Rev Iberoam Micol. 33:248–252. 2016.(In Spanish).

|

|

37

|

Castagnola E, Mariani M, Ricci E, Russo C,

Saffioti C and Mesini A: Fungal infections in pediatric patients:

Challenges and considerations in treatment. Expert Rev Anti Infect

Ther: Oct 12, 2025 (Epub ahead of print).

|

|

38

|

Popova M and Rogacheva Y: Epidemiology of

invasive fungal diseases in patients with hematological

malignancies and haematopoietic cell transplantation recipients:

Systematic review and meta-analysis of trends over time. J Infect

Public Health. 18(102804)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Lehrnbecher T: The clinical management of

invasive mold infection in children with cancer or undergoing

hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Expert Rev Anti Infect

Ther. 17:489–499. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Groll AH, Pana D, Lanternier F, Mesini A,

Ammann RA, Averbuch D, Castagnola E, Cesaro S, Engelhard D,

Garcia-Vidal C, et al: 8th European conference on infections in

leukaemia: 2020 Guidelines for the diagnosis, prevention, and

treatment of invasive fungal diseases in paediatric patients with

cancer or post-haematopoietic cell transplantation. Lancet Oncol.

22:e254–e269. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Wang Q, Lei Y, Wang J, Xu X, Wang L, Zhou

H and Guo Z: Tumor and microecology committee of China anti-cancer

association. Expert consensus on the relevance of intestinal

microecology and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Clin

Transplant. 38(e15186)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Elhaj Mahmoud D, Hérivaux A, Morio F,

Briard B, Vigneau C, Desoubeaux G, Bouchara JP, Gangneux JP, Nevez

G, Le Gal S and Papon N: The epidemiology of invasive fungal

infections in transplant recipients. Biomed J.

47(100719)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Pana ZD, Roilides E, Warris A, Groll AH

and Zaoutis T: Epidemiology of invasive fungal disease in children.

J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 6 (Suppl 1):S3–S11. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Steinbach WJ and Fisher BT: International

collaborative on contemporary epidemiology and diagnosis of

invasive fungal disease in children. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 6

(Suppl 1):S1–S2. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Czyżewski K, Gałązka P, Frączkiewicz J,

Salamonowicz M, Szmydki-Baran A, Zając-Spychała O,

Gryniewicz-Kwiatkowska O, Zalas-Więcek P, Chełmecka-Wiktorczyk L,

Irga-Jaworska N, et al: Epidemiology and outcome of invasive fungal

disease in children after hematopoietic cell transplantation or

treated for malignancy: Impact of national programme of antifungal

prophylaxis. Mycoses. 62:990–998. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Wu X, Ma X, Song T, Liu J, Sun Y and Wu D:

The indirect effects of CMV reactivation on patients following

allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: An evidence

mapping. Ann Hematol. 103:917–933. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

van der Maas NG, von Asmuth EGJ, Berghuis

D, van Schouwenburg PA, Putter H, van der Burg M and Lankester AC:

Modeling influencing factors in B-cell reconstitution after

hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in children. Front Immunol.

12(684147)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Marie-Cardine A, Divay F, Dutot I, Green

A, Perdrix A, Boyer O, Contentin N, Tilly H, Tron F, Vannier JP and

Jacquot S: Transitional B cells in humans: characterization and

insight from B lymphocyte reconstitution after hematopoietic stem

cell transplantation. Clin Immunol. 127:14–25. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Maliszewski CR, Sato TA, Vanden Bos T,

Waugh S, Dower SK, Slack J, Beckmann MP and Grabstein KH: Cytokine

receptors and B cell functions. I. Recombinant soluble receptors

specifically inhibit IL-1- and IL-4-induced B cell activities in

vitro. J Immunol. 144:3028–3033. 1990.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Pan L, Sato S, Frederick JP, Sun XH and

Zhuang Y: Impaired immune responses and B-cell proliferation in

mice lacking the Id3 gene. Mol Cell Biol. 19:5969–5980.

1999.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Inaba A, Tuong ZK, Zhao TX, Stewart AP,

Mathews R, Truman L, Sriranjan R, Kennet J, Saeb-Parsy K, Wicker L,

et al: Low-dose IL-2 enhances the generation of IL-10-producing

immunoregulatory B cells. Nat Commun. 14(2071)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Roy K, Chakraborty M, Kumar A, Manna AK

and Roy NS: The NFκB signaling system in the generation of B-cell

subsets: from germinal center B cells to memory B cells and plasma

cells. Front Immunol. 14(1185597)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Puerta-Alcalde P and Garcia-Vidal C:

Changing epidemiology of invasive fungal disease in allogeneic

hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. J Fungi (Basel).

7(848)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Lehrnbecher T, Schöning S, Poyer F, Georg

J, Becker A, Gordon K, Attarbaschi A and Groll AH: Incidence and

outcome of invasive fungal diseases in children with hematological

malignancies and/or allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell

transplantation: Results of a prospective multicenter study. Front

Microbiol. 10(681)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Said AM, Afridi F, Redell MS, Vrana C,

O'Farrell C, Scheurer ME, Dailey Garnes NJ, Gramatges MM and Dutta

A: Invasive candidiasis in pediatric hematologic malignancy:

Increased risk of dissemination with Candida tropicalis.

Pediatr Infect Dis J. 44:58–63. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Barantsevich N and Barantsevich E:

Diagnosis and treatment of invasive candidiasis. Antibiotics

(Basel). 11(718)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Wang L, Wang Y, Hu J, Sun Y, Huang H, Chen

J, Li J, Ma J, Li J, Liang Y, et al: Clinical risk score for

invasive fungal diseases in patients with hematological

malignancies undergoing chemotherapy: China assessment of

antifungal therapy in hematological diseases (CAESAR) study. Front

Med. 13:365–377. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

58

|

Sun Y, Meng F, Han M, Zhang X, Yu L, Huang

H, Wu D, Ren H, Wang C, Shen Z, et al: Epidemiology, management,

and outcome of invasive fungal disease in patients undergoing

hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in China: A multicenter

prospective observational study. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant.

21:1117–1126. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

59

|

Celkan T, Kizilocak H, Evim M, Meral Güneş

A, Özbek NY, Yarali N, Ünal E, Patiroğlu T, Yilmaz Karapinar D,

Sarper N, et al: Hepatosplenic fungal infections in children with

leukemia-risk factors and outcome: A multicentric study. J Pediatr

Hematol Oncol. 41:256–260. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

60

|

Machado M, Fortún J and Muñoz P: Invasive

aspergillosis: A comprehensive review. Med Clin (Barc).

163:189–198. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

61

|

Boyer J, Feys S, Zsifkovits I, Hoenigl M

and Egger M: Treatment of invasive aspergillosis: How it's going,

where it's heading. Mycopathologia. 188:667–681. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

62

|

Duréault A, Tcherakian C, Poiree S,

Catherinot E, Danion F, Jouvion G, Bougnoux ME, Mahlaoui N, Givel

C, Castelle M, et al: Spectrum of pulmonary aspergillosis in

hyper-IgE syndrome with autosomal-dominant STAT3 deficiency. J

Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 7:1986–1995.e3. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

63

|

Luckowitsch M, Rudolph H, Bochennek K,

Porto L and Lehrnbecher T: Central nervous system mold infections

in children with hematological malignancies: Advances in diagnosis

and treatment. J Fungi (Basel). 7(168)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

64

|

Karaman S, Kebudi R, Kizilocak H, Karakas

Z, Demirag B, Evim MS, Yarali N, Kaya Z, Karagun BS, Aydogdu S, et

al: Central nervous system fungal infections in children with

leukemia and undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: A

retrospective multicenter study. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol.

44:e1039–e1045. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

65

|

Alexander BD, Lamoth F, Heussel CP, Prokop

CS, Desai SR, Morrissey CO and Baddley JW: Guidance on imaging for

invasive pulmonary aspergillosis and mucormycosis: From the imaging

working group for the revision and update of the consensus

definitions of fungal disease from the EORTC/MSGERC. Clin Infect

Dis. 72 (Suppl 2):S79–S88. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

66

|

Wu Y, Yan L, Wang H, et al: Clinical study

on empirical and diagnostic-driven (pre-emptive) therapy of

voriconazole in severe aplastic anaemia patients with invasive

fungal disease after intensive immunosuppressive therapy. Eur J

Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 40:949–954. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

67

|

Fang W, Wu J, Cheng M, Zhu X, Du M, Chen

C, Liao W, Zhi K and Pan W: Diagnosis of invasive fungal

infections: challenges and recent developments. J Biomed Sci.

30(42)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

68

|

Lamoth F, Cruciani M, Mengoli C,

Castagnola E, Lortholary O, Richardson M and Marchetti O: Third

European Conference on Infections in Leukemia (ECIL-3). β-Glucan

antigenemia assay for the diagnosis of invasive fungal infections

in patients with hematological malignancies: A systematic review

and meta-analysis of cohort studies from the third European

conference on infections in leukemia (ECIL-3). Clin Infect Dis.

54:633–643. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

69

|

Chen M, Xu Y, Hong N, Yang Y, Lei W, Du L,

Zhao J, Lei X, Xiong L, Cai L, et al: Epidemiology of fungal

infections in China. Front Med. 12:58–75. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

70

|

Çağlar İ, Özkerim D, Tahta N, Düzgöl M,

Bayram N, Demirağ B, Karapinar TH, Sorguç Y, Gözmen S, Dursun V, et

al: Assessment of serum galactomannan test results of pediatric

patients with hematologic malignancies according to consecutive

positivity and threshold level in terms of invasive aspergillosis

diagnosis: Cross-sectional research in a tertiary care hospital. J

Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 42:e271–e276. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

71

|

Springer J, Held J, Mengoli C, Schlegel

PG, Gamon F, Träger J, Kurzai O, Einsele H, Loeffler J and Eyrich

M: Diagnostic performance of (1→3)-β-D-glucan alone and in

combination with Aspergillus PCR and galactomannan in serum

of pediatric patients after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell

transplantation. J Fungi (Basel). 7(238)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

72

|

Ferreras-Antolin L, Borman A, Diederichs

A, Warris A and Lehrnbecher T: Serum beta-D-glucan in the diagnosis

of invasive fungal disease in neonates, children and adolescents: A

critical analysis of current data. J Fungi (Basel).

8(1262)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

73

|

Saffioti C, Mesini A, Bandettini R and

Castagnola E: Diagnosis of invasive fungal disease in children: A

narrative review. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 17:895–909.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

74

|

Warris A and Lehrnbecher T: Progress in

the diagnosis of invasive fungal disease in children. Curr Fungal

Infect Rep. 11:35–44. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

75

|

Otto WR and Green AM: Fungal infections in

children with haematologic malignancies and stem cell transplant

recipients. Br J Haematol. 189:607–624. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

76

|

Cao GJ, Xing ZF, Hua L, Ji YH, Sun JB and

Zhao Z: Evaluation of the diagnostic performance of panfungal

polymerase chain reaction assay in invasive fungal diseases. Exp

Ther Med. 14:4208–4214. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

77

|

White PL, Alanio A, Brown L, Cruciani M,

Hagen F, Gorton R, Lackner M, Millon L, Morton CO,

Rautemaa-Richardson R, et al: An overview of using fungal DNA for

the diagnosis of invasive mycoses. Expert Rev Mol Diagn.

22:169–184. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

78

|

Singh S and Singh M, Verma N, Sharma M,

Pradhan P, Chauhan A, Jaiswal N, Chakrabarti A and Singh M:

Comparative accuracy of 1,3 beta-D glucan and galactomannan for

diagnosis of invasive fungal infections in pediatric patients: A

systematic review with meta-analysis. Med Mycol. 59:139–148.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

79

|

Wang Z, Pan M and Zhu J: Global burden of

reported lower respiratory system fungal infection. Front Cell

Infect Microbiol. 15(1542922)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

80

|

Srivali N, Permpalung N, Ammannagari N,

Cheungpasitporn W and Bischof EF: Significance of halo, reversed

halo and air crescent signs in lymphomatoid granulomatosis and

pulmonary fungal infections. Thorax. 68:1070–1071. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

81

|

Lamoth F, Prakash K, Beigelman-Aubry C and

Baddley JW: Lung and sinus fungal infection imaging in

immunocompromised patients. Clin Microbiol Infect. 30:296–305.

2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

82

|

Alamdaran SA, Bagheri R, Darvari SF,

Bakhtiari E and Ghasemi A: Pulmonary invasive fungal disease:

Ultrasound and computed tomography scan findings. Thorac Res Pract.

24:292–297. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

83

|

Perez P, Patiño J, Franco AA, Rosso F,

Beltran E, Manzi E, Castro A, Estacio M and Valencia DM:

Prophylaxis for invasive fungal infection in pediatric patients

with allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood Res.

57:34–40. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

84

|

Elitzur S, Arad-Cohen N, Barg A,

Litichever N, Bielorai B, Elhasid R, Fischer S, Fruchtman Y, Gilad

G, Kapelushnik J, et al: Mucormycosis in children with

haematological malignancies is a salvageable disease: A report from

the israeli study group of childhood leukemia. Br J Haematol.

189:339–350. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

85

|

Bonifaz A, Tirado-Sánchez A,

Hernández-Medel ML, Araiza J, Kassack JJ, Del Angel-Arenas T,

Moisés-Hernández JF, Paredes-Farrera F, Gómez-Apo E, Treviño-Rangel

RJ and González GM: Mucormycosis at a tertiary-care center in

Mexico. A 35-year retrospective study of 214 cases. Mycoses.

64:372–380. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

86

|

Pagano L, Dragonetti G, De Carolis E,

Veltri G, Del Principe MI and Busca A: Developments in identifying

and managing mucormycosis in hematologic cancer patients. Expert

Rev Hematol. 13:895–905. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

87

|

Antoniadi K, Iosifidis E, Vasileiou E,

Tsipou C, Lialias I, Papakonstantinou E, Kattamis A,

Polychronopoulou S, Roilides E and Tragiannidis A: Invasive

mucormycosis in children with malignancies: Report from the

infection working group of the hellenic society of pediatric

hematology-oncology. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 43:176–179.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

88

|

Zhang Z, Bills GF and An Z: Advances in

the treatment of invasive fungal disease. PLoS Pathog.

19(e1011322)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

89

|

Sun Y, Hu J, Huang H, Chen J, Li J, Ma J,

Li J, Liang Y, Wang J, Li Y, et al: Clinical risk score for

predicting invasive fungal disease after allogeneic hematopoietic

stem cell transplantation: Analysis of the China assessment of

antifungal therapy in hematological diseases (CAESAR) study.

Transpl Infect Dis. 23(e13611)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

90

|

Zhang T, Shen Y and Feng S: Clinical

research advances of isavuconazole in the treatment of invasive

fungal diseases. Front Cell Infect Microbiol.

12(1049959)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

91

|

Herbrecht R, Denning DW, Patterson TF,

Bennett JE, Greene RE, Oestmann JW, Kern WV, Marr KA, Ribaud P,

Lortholary O, et al: Voriconazole versus amphotericin B for primary

therapy of invasive aspergillosis. N Engl J Med. 347:408–415.

2002.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

92

|

Turkova A, Roilides E and Sharland M:

Amphotericin B in neonates: Deoxycholate or lipid formulation as

first-line therapy-is there a ‘right’ choice? Curr Opin Infect Dis.

24:163–171. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

93

|

Tissot F, Agrawal S, Pagano L, Petrikkos

G, Groll AH, Skiada A, Lass-Flörl C, Calandra T, Viscoli C and

Herbrecht R: ECIL-6 guidelines for the treatment of invasive

candidiasis, aspergillosis and mucormycosis in leukemia and

hematopoietic stem cell transplant patients. Haematologica.

102:433–444. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

94

|

Ruhnke M, Cornely OA, Schmidt-Hieber M,

Alakel N, Boell B, Buchheidt D, Christopeit M, Hasenkamp J, Heinz

WJ, Hentrich M, et al: Treatment of invasive fungal diseases in

cancer patients-Revised 2019 recommendations of the infectious

diseases working party (AGIHO) of the German society of hematology

and oncology (DGHO). Mycoses. 63:653–682. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

95

|

Tu S, Zhang K, Wang N, Chu J, Yang L and

Xie Z: Comparative study of posaconazole and voriconazole for

primary antifungal prophylaxis in patients with pediatric acute

leukemia. Sci Rep. 13(18789)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

96

|

Lee KH, Lim YT, Hah JO, Kim YK, Lee CH and

Lee JM: Voriconazole plus caspofungin for treatment of invasive

fungal infection in children with acute leukemia. Blood Res.

52:167–173. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

97

|

Qiu KY, Liao XY, Fang JP, Xu HG, Li Y,

Huang K and Zhou DH: Combination antifungal treatment for invasive

fungal disease after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in

children with hematological disorders. Transpl Infect Dis.

21(e13066)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

98

|

Goscicki BK, Yan SQ, Mathew S, Mauguen A

and Cohen N: A retrospective analysis of micafungin prophylaxis in

children under 12 years undergoing chemotherapy or hematopoietic

stem cell transplantation. J Pediatr Pharmacol Ther. 29:379–384.

2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

99

|

Kazakou N, Vyzantiadis TA, Gambeta A,

Vasileiou E, Tsotridou E, Kotsos D, Giantsidi A, Saranti A,