Introduction

Osteoporosis, a metabolic disease affecting millions

of older adults globally, is represented by the deterioration of

bone mass and microarchitecture, leading to fragility fracture

(1). Dual-energy X-ray

absorptiometry (DXA) is the gold-standard method for diagnosing

osteoporosis. It quantifies bone mineral density (BMD) as a

surrogate of bone strength. However, DXA is not portable and emits

ionising radiation. Therefore, it is unsuitable for deployment in

mass bone health screening. These limitations can be overcome with

quantitative ultrasonometry (QUS), which provides alternative

measures of bone health (2).

Previous studies have established that QUS indices predict

osteoporosis/osteopenia (3,4) and

fracture risk (5) and may reflect

microarchitecture (6).

Apart from being female and menopausal, being

underweight is a major risk factor for osteoporosis (7,8). A

low body weight negatively impacts bone health by acting as a

surrogate for malnutrition or exerting low mechanical loading on

bone (9). Mechanical loading is

important to stimulate bone repair and maintain bone health

(10). Previous studies have

firmly established body weight and the body mass index (BMI) as

positive predictors of bone health status (11). Obesity, defined by BMI, is found to

decrease the odds of osteoporosis by 70.1% (11). The BMI is reflective of body size

but may not reflect adiposity status correctly (12). It underestimates the degree of

adiposity in patients with sarcopenia but overestimates that in

athletes (12). The relationship

between adiposity and bone health remains controversial even after

the delineation of the effects of the BMI (13).

Adiposity may be a double-edged sword for bone

health. On the positive side, it exerts mechanical loading on bone;

such loading stimulates bone mass accrual to support a person's

weight (14). Adipose tissue also

synthesises oestrogens, which are beneficial for bone health

(15). Furthermore, the

hyperinsulinaemia that is often associated with obesity can

increase bone mass because of the anabolic action of insulin

(16).

On the negative side, adiposity is associated with

chronic inflammation, a state known to cause bone loss. Adipokines

secreted by adipocytes, such as adiponectin and resistin, can

actively promote bone loss (17,18).

Meanwhile, leptin's role is complex: It can be either pro- or

antiosteogenic depending on whether it regulates bone health

through central or peripheral pathways (19). Therefore, the net effect of

adiposity on bone health remains debatable.

Other indices have been developed as alternatives in

consideration of the limitations of the BMI in reflecting

adiposity. Waist circumference (WC) (20), waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) (21), waist-to-height ratio (WtHR)

(22), a body shape index (ABSI)

(23), body roundness index (BRI)

(24) and conicity index (CI)

(25), derived from body

anthropometric measurements, can predict cardiometabolic risks

well. The relationship between these alternative adiposity indices

and bone health has been explored. However, most studies that

investigated these relationships are derived from the databases of

the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey on the United

States population (26-32),

whereas those from other geographical regions are sparse (33-37).

Heterogenous findings, whereby negative and positive relationships

between adiposity indicated by the above indices and bone health

have been observed, have been obtained. These gaps suggest that

additional studies on diverse populations should be

implemented.

The present study attempts to address the above

research gaps by comparing the associations between various

adiposity indices and bone health measured via calcaneal QUS

amongst Malaysians. It will help clarify the effect of adiposity on

bone health. Its findings are particularly important for Malaysians

at two levels. Firstly, Malaysia is rapidly advancing to an ageing

society, with 15% of the overall population projected to be aged 60

years or above by 2030(38).

Secondly, Malaysians have a combined obesity and overweight

prevalence of 54.4% (39). The

compounded effects of ageing and obesity could have an influence on

the prevalence of osteoporosis in Malaysia. Therefore, the present

study offers insight into adiposity as an interventional target in

osteoporosis.

Patients and methods

Ethical considerations

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the

Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia Ethics Committee (Kuala Lumpur,

Malaysia; approval code: JEP-2024-739). Subjects were briefed on

the details of the study and provided written informed consent

before participating.

Subject recruitment

This cross-sectional study was conducted from

October 2024 to November 2024 in conjunction with the institutional

Osteoporosis Month programme. Subjects were recruited through

purposive sampling, in which all individuals who met the selection

criteria were invited to participate in the study. The purposive

sampling strategy was adopted because of the nature of the health

screening event. The screening site was the lobby of Hospital

Canselor Tuanku Muhriz, affiliated with Universiti Kebangsaan

Malaysia (Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia). The researchers were aware of

the biases carried by the recruitment strategy. These biases are

discussed amongst the limitations of the study.

The subjects included were adult Malaysians aged 20

years and above. They were excluded if they declared having medical

conditions affecting bone health (such as Paget's disease,

osteogenesis imperfecta, osteomalacia, rickets,

hyper/hypothyroidism, hyper/hypoparathyroidism and chronic kidney

diseases) or taking medication that affects bone health [such as

glucocorticoids, sex hormones, aromatase inhibitors, androgen

deprivation therapy, anticoagulants (heparin and warfarin), loop

diuretics, chemotherapeutics, anticonvulsants, antidepressants,

thiazolidinediones and antiretrovirals].

Sample size calculation

Sample size was calculated by using G*Power version

3.1.97 (Heinrich-Heine-Universität) with input effect size=0.15

(moderate effect size by convention), alpha error=0.05, power=0.8

and number of predictors (variables of interest and

confounders)=16. The calculated minimum sample was 143.

Confounder measurements

The subjects answered a demographic, lifestyle and

medical history questionnaire that has been used in previous bone

health studies (40). Their date

of birth and citizenship were identified from their national

registration identity card. Their biological sex, ethnicity,

household income, pre-existing medical conditions and medical use

were self-declared. The lifestyle questionnaire explores the

subjects' habits in smoking cigarettes and consuming alcohol, dairy

products, tea and coffee. Female subjects answered additional

questions on menstrual status.

Anthropometric measurements

The subjects' waist circumference at the midpoint

between the lowest point of the ribcage and highest point of the

iliac crest was determined by using a measuring tape. Hip

circumference was measured at the widest part of the gluteal

muscle. The subjects' height without shoes was measured with a

stadiometer. These three measurements were recorded to the nearest

1 cm. The subjects' body weight while wearing light clothing

without shoes was recorded by using a scale (BC353; Accunic) to the

nearest 0.1 kg.

Calculation of adiposity indices

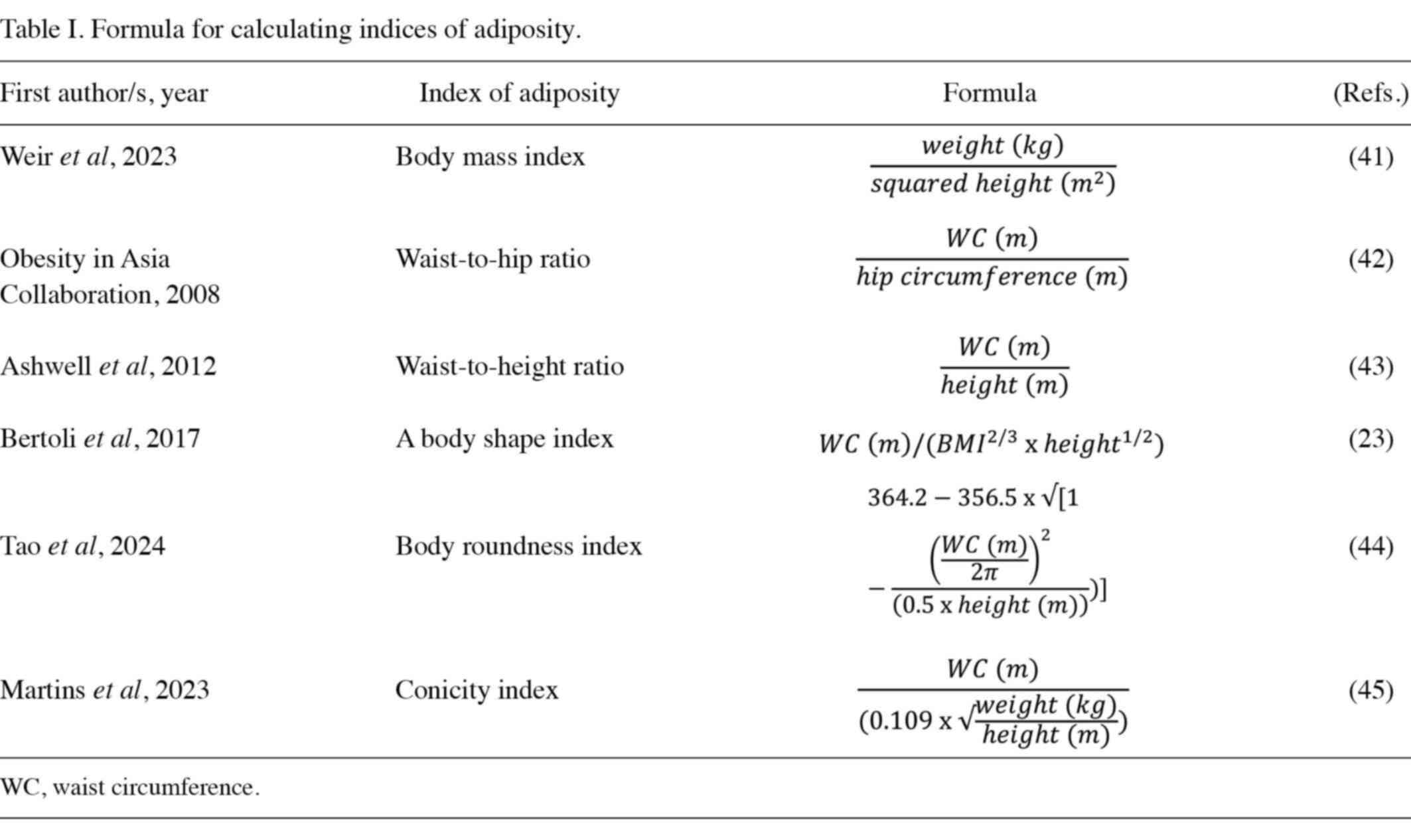

The adiposity indices BMI (41), WHR (42), WtHR (43), ABSI (23), BRI (44) and CI (45) were calculated on the basis of the

formulas shown in Table I.

Bone health measurements

The bone health of the subjects was quantified by

using a calcaneal bone sonometer (OSTEOKJ3000; Kejin) and recorded

as speed of sound (SOS) and broadband ultrasound attenuation (BUA).

The osteoporosis index (OI) was calculated automatically by using

the formula OI=0.106 x SOS + 0.5 x BUA-127.4, as preset by the

manufacturer. The subject inserted their nondominant foot into the

holder. Two oil-filled balloon transducers were inflated to touch

the lateral sides of the calcaneus, which had been cleaned with

alcohol and covered with ultrasonic gel. Ultrasound was transmitted

through the calcaneal bone and the device interpreted signals. Each

subject was measured two times and a third reading was taken when

the previous two readings were inconsistent. The categorisation of

subjects based on T-score or Z-score was not performed in the

present study because the World Health Organisation's cut-offs

apply only to DXA. Therefore, raw OI values were used to reflect

the bone health of the subject, in which a high value indicates

good bone health.

Statistical analysis

The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to test for

data normality. The subjects' characteristics were compared between

men and women by using an independent-samples t-test for normally

distributed parameters and the Mann-Whitney U-test for skewed data.

Comparison between categorical variables was conducted by employing

the Chi-squared test or Fisher's exact test. Multiple linear

regression was used to investigate the association between OI and

bone health, with adjustment for potential confounders, such as

age, sex, ethnicity, status of smoking (yes or former/no), status

of alcohol use (yes or former/no), status of regular

milk/tea/coffee consumption (yes/no), calcium supplements (yes/no),

self-reported fracture (yes/no), self-reported parental fracture

(yes/no), self-reported height reduction (yes/no), use of

medication (yes/no) and presence of comorbidities (yes/no). Cook's

distance was employed to identify multivariate outliers, which were

subsequently removed to ensure the generalisability of the models.

Associations were reported in the form of B and β values.

Statistical analysis was performed by utilising SPSS version 26

(IBM, Corp.). The data were expressed as mean standard ± deviation

and n (%). P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically

significant difference.

Results

Subject characteristics

The present study recruited 320 subjects (231 women

and 89 men) within the study period. The mean age of the subjects

was 50.1±16.7 years. The height, weight, waist circumference, WHR,

WtHR, CI, BRI, ABSI, skeletal muscle mass, visceral fat area, BUA

and OI of men were significantly higher compared with women

(P>0.05). The body fat percentage of women was significantly

higher compared with men (P>0.05; Table II). Significantly more men were

regular cigarette smokers and alcohol consumers (P<0.05).

Significantly more women were regular coffee and calcium supplement

consumers (P<0.05). The distributions of ethnicity, regular milk

and tea consumption, self-reported fracture history, parental

fracture history and height reduction were not significantly

different between sexes (P>0.05; Table III).

| Table IISubject's age, body composition and

calcaneal quantitative ultrasonometry data. |

Table II

Subject's age, body composition and

calcaneal quantitative ultrasonometry data.

| Parameter | Total (n=320) | Women (n=231) | Men (n=89) | P-value |

|---|

| Age, years | 50.1±16.7 | 50.0±16.0 | 50.5±18.5 | 0.802 |

| Height, cm | 159.8±8.4 | 156.1±5.2 | 169.4±7.5 | <0.001 |

| Weight, kg | 66.8±16.4 | 63.4±14.2 | 75.6±18.5 |

<0.001a |

| Body weight index,

kg/m2 | 26.1±5.6 | 26.0±5.7 | 26.2±5.5 | 0.770a |

| Waist

circumference, cm | 85.1±12.0 | 82.1±10.1 | 92.7±13.2 | <0.001 |

| Waist-to-hip

ratio | 0.89±0.09 | 0.87±0.07 | 0.94±0.12 | 0.009b |

| Waist-to-height

ratio | 0.53±0.07 | 0.53±0.07 | 0.55±0.07 | 0.017 |

| Conicity index | 1.21±0.06 | 1.19±0.03 | 1.28±0.06 | <0.001 |

| Body roundness

index | 4.08±1.46 | 3.96±1.39 | 4.39±1.61 | 0.024a |

| A body shape

index | 0.077±0.004 | 0.075±0.002 | 0.081±0.003 |

<0.001b |

| Skeletal muscle

mass, kg | 24.9±5.4 | 22.6±3.3 | 30.8±5.4 |

<0.001c |

| Fat mass, kg | 21.6±8.9 | 22.2±8.5 | 20.1±9.7 | 0.060 |

| Body fat

percentage, % | 31.5±7.2 | 33.8±5.9 | 25.3±6.9 | <0.001 |

| Visceral fat area,

cm2 | 99.1±52.0 | 90.7±47.2 | 120.9±57.8 |

<0.001a |

| Speed of sound,

m/sec | 1,530.3±26.5 | 1,528.9±24.1 | 1,533.9±31.9 | 0.183 |

| Broadband

attenuation of sound, dB/MHz | 25.1±6.1 | 24.1±5.7 | 27.5±6.5 | <0.001 |

| Osteoporosis

index | 47.0±5.4 | 46.4±4.9 | 48.6±6.2 | 0.003 |

| Table IIISubject characteristics. |

Table III

Subject characteristics.

| Item | Total (n=320) | Women (n=231) | Men (n=89) | P-value |

|---|

| Ethnicity | | | | 0.145 |

|

Malay | 180 (56.3) | 137 (59.3) | 43 (48.3) | |

|

Chinese | 113 (35.3) | 79 (34.2) | 34 (38.2) | |

|

Indian | 18 (5.6) | 10 (4.3) | 8(9) | |

|

Others | 9 (2.8) | 5 (2.2) | 4 (4.5) | |

| Menstrual

status | | | | NR |

|

Regular | 105 (45.5) | 105 (45.5) | NR | |

|

Irregular | 16 (6.9) | 16 (6.9) | NR | |

|

Menopausal | 110 (47.6) | 110 (47.6) | NR | |

| Regular

smokinga | | | | <0.001 |

|

No | 303 (94.7) | 227 (98.3) | 76 (85.4) | |

|

Yes | 17 (5.3) | 4 (1.7) | 13 (14.6) | |

| Regular alcohol

drinking | | | | 0.009 |

|

No | 304(95) | 224(97) | 80 (89.9) | |

|

Yes | 16(5) | 7(3) | 9 (10.1) | |

| Regular milk

consumption | | | | 0.845 |

|

No | 195 (60.9) | 140 (60.6) | 55 (61.8) | |

|

Yes | 125 (39.1) | 91 (39.4) | 34 (38.2) | |

| Regular coffee

drinking | | | | 0.021 |

|

No | 161 (50.3) | 107 (46.3) | 54 (60.7) | |

|

Yes | 159 (49.7) | 124 (53.7) | 35 (39.3) | |

| Regular tea

drinking | | | | 0.289 |

|

No | 177 (55.3) | 132 (57.1) | 45 (50.6) | |

|

Yes | 143 (44.7) | 99 (42.9) | 44 (49.4) | |

| Regular calcium

supplement | | | | 0.018 |

|

No | 228 (71.3) | 156 (67.5) | 72 (80.9) | |

|

Yes | 92 (28.7) | 75 (32.5) | 17 (19.1) | |

| Self-reported

fracture history | | | | 0.962 |

|

No | 280 (87.5) | 202 (87.4) | 78 (87.6) | |

|

Yes | 40 (12.5) | 29 (12.6) | 11 (12.4) | |

| Self-reported

parental fracture | | | | 0.151 |

|

No | 273 (85.3) | 193 (83.5) | 80 (89.9) | |

|

Yes | 47 (14.7) | 38 (16.5) | 9 (10.1) | |

| Self-reported

height reduction | | | | 0.238 |

|

No | 280 (87.5) | 199 (86.1) | 81(91) | |

|

Yes | 40 (12.5) | 32 (13.9) | 8(9) | |

Association between bone health and

adiposity indices

Linear regression revealed a positive association

between OI and BMI (β=0.212, P<0.001), waist circumference

(β=0.268, P<0.001), WtHR (β=0.190, P=0.001), CI (β=0.151,

P=0.007) and BRI (β=0.203, P<0.001) before adjustment for

confounders (Table IV, Model 1).

After adjustment for confounders (Table IV, Model 2), a significant

positive association was found between OI and BMI (β=0.172,

P<0.001), waist circumference (β=0.184, P=0.001), WHR (β=0.124,

P=0.025), WtHR (β=0.160, P=0.002) and BRI (β=0.165, P=0.001). A

significant negative association was found between OI and ABSI

(β=-0.183, P=0.008). The changes in the regression coefficient with

the increment of confounders are presented in Table SI. The associations between OI and

adiposity indices were consistent in each model, showing their

robustness.

| Table IVAssociation between bone health

(osteoporosis index) and adiposity indices. |

Table IV

Association between bone health

(osteoporosis index) and adiposity indices.

| | | Model 1 | Model 2 |

|---|

| Parameter | na | B | SE | β | P-value | B | SE | β | P-value |

|---|

| Body mass

index | 300 | 0.189 | 0.05 | 0.212 | <0.001 | 0.152 | 0.043 | 0.172 | <0.001 |

| Waist

circumference | 300 | 0.105 | 0.022 | 0.268 | <0.001 | 0.072 | 0.021 | 0.184 | 0.001 |

| Waist-to-hip

ratio | 302 | 1.182 | 3.024 | 0.022 | 0.700 | 6.485 | 2.874 | 0.124 | 0.025 |

| Waist-to-height

ratio | 302 | 13.756 | 4.111 | 0.190 | 0.001 | 11.581 | 3.625 | 0.16 | 0.002 |

| Conicity index | 302 | 14.647 | 5.367 | 0.151 | 0.007 | 7.106 | 7.078 | 0.073 | 0.316 |

| Body roundness

index | 302 | 0.695 | 0.194 | 0.203 | <0.001 | 0.566 | 0.171 | 0.165 | 0.001 |

| A body shape

index | 298 | 5.529 | 79.668 | 0.004 | 0.945 | -251.311 | 94.264 | -0.183 | 0.008 |

Discussion

The present cross-sectional study found a positive

association between bone health and BMI, waist circumference, WHR,

WtHR, CI and BRI and a negative association between bone health and

ABSI amongst Malaysians. It found no significant association

between bone health and CI.

In the present study, the BMI was found to be

positively associated with bone health. This observation agrees

with the authors' previous findings on Malaysian men aged >20

years that revealed a positive relationship between BMI and bone

health, as indicated by QUS (46).

As mentioned earlier, underweight is well recognised as a strong

risk factor for osteoporosis (7,8). A

Mendelian randomisation study demonstrated a causal relationship

between BMI and BMD; however, this relationship is site-specific

(47). A high BMI was found to

causally increase the BMD at the lumbar spine and calcaneus but

exerts no effects on forearm and femoral neck BMD (47). This association is likely driven by

mechanical loading (11). However,

the relationship between the BMI and bone health is highly complex.

A meta-analysis reported a low risk of vertebral fracture with a

high BMI in men, whereas the inverse was observed in women after

adjustment for BMD (48). Another

meta-analysis found that an increased BMI was associated with

trabecular microarchitecture deterioration (49). Therefore, an increased BMI

associated with BMD does not always translate into improved bone

quality.

In this work, bone health was positively associated

with the waist circumference, WHR, WtHR and BRI. Given that these

indices were not adjusted for the BMI, they could act as surrogate

measures for body size, reflecting the relationship between

mechanical loading and bone health. This observation was supported

by other studies that indicated a positive association between the

above indices and BMD (37) or a

negative association between the above indices and osteoporosis

risk (29,31,50).

Nevertheless, other studies reported contradictory results

(32,34,51).

These controversies may be explained by a nonlinear relationship

between these indices and bone health (U-shape) and sex differences

in this relationship (52). As a

result of the limited number of male subjects, a sex-based

subanalysis was not performed in the present study.

CI was positively associated with bone health in the

adjusted model. However, this association weakened after adjustment

for potential confounders. CI primarily reflects central adiposity

and, indirectly, the effects of body size and mechanical loading on

bone, thereby explaining the above positive association.

Nevertheless, this association is weak and not independent of the

covariates studied. While CI is a useful cardiometabolic risk

marker, it may not effectively predict bone health. Another study

comparing the association between various anthropometric indices

and osteoporosis risk found that CI did not perform as well as BRI

and WtHR (53).

In this research, bone health was negatively

associated with ABSI. Similar findings were obtained by previous

studies (27,28,30,34-36,54),

which reported low BMD and high osteoporosis risk. Given that the

calculation of ABSI accounts for BMI, ABSI may accurately reflect

the adiposity status independent of body size. It has been shown to

correlate with visceral adiposity without being influenced by body

weight (55). Visceral fat has a

more significant association with systemic inflammation and

metabolic dysregulation than subcutaneous fat (56). These underlying mechanisms could

explain the negative association between ABSI and bone health

observed in the present study. However, given that inflammatory

cytokine and adipokine levels were not determined in the subjects

of this research, this mechanistic explanation remains

speculative.

Several limitations should be noted before

generalising the results of the present study. The cross-sectional

nature of this work prevents causal inference between adiposity and

bone health. The subjects' recruitment from a health screening

programme is prone to suffering from selection and volunteer

biases. Therefore, the characteristics of these subjects might

differ from those of the general population. For example, the

subjects who volunteered for the present study may be more

health-conscious than the general population. Conversely, they may

have specific health concerns that motivated them to participate in

the research. The nonrandomised sampling approach also prevented

the authors from comparing the baseline characteristics of the

subjects with those of a national representative cohort, such as

the cohort included in the National Health and Morbidity Survey of

Malaysia, to verify the extent of sampling bias. The small sizes of

subgroups (based on sex, ethnicity and BMI status) also prevented

the authors from investigating the relationship between variables

in different contexts. Certain studies have demonstrated that the

association between the adiposity index and bone health can be

influenced by sex and diabetes status (28,52),

and most have revealed consistent associations (26,31,32).

A study found that the connection between adiposity and bone health

differs by sex in older adults (52). For postmenopausal women, the

relationship is U-shaped: Both very low and very high adiposity

levels are associated with poor bone health. This may be because

low body fat limits their postmenopausal oestrogen production

(57), which supports bone health,

while high body fat promotes chronic inflammation that damages

bones. For older men, the relationship is linear, meaning bone

health simply declines as adiposity increases, likely due to the

damaging effects of chronic inflammation.

Regarding the bone health assessment tool, QUS is

not the gold standard for diagnosing osteoporosis despite its

portability and safety features. Its T- and Z-scores cannot be used

interchangeably with the values generated by DXA because of

differences in reference values and technology. In the present

study, the physical activity levels of the subjects were excluded

from the analysis because the subjects had difficulty in accurately

recalling their physical activities. Bone health biochemical

markers, such as circulating vitamin D, calcium and phosphorus

levels, were not determined in this research because blood

collection was not performed in the health screening session.

Nevertheless, this work provides novel insights into the

relationship between adiposity and bone health and affirms that

ABSI could be considered as a risk factor for osteoporosis in the

general population.

In conclusion, amongst Malaysians, adiposity indices

unadjusted for body size, such as the BMI, waist circumference,

WHR, WtHR, CI and BRI, are positively associated with the bone

health index measured by QUS. By contrast, ABSI, which accounts for

body size, shows a negative association with the bone health index.

The findings of this work suggest that ABSI may be a useful marker

for identifying individuals at risk of poor bone health in the

Malaysian population. However, its critical value and clinical

effectiveness still require further substantial validation before

it can be reliably used as a routine risk assessment tool.

Supplementary Material

Changes in association between bone

health (osteoporosis index) and adiposity indices with increasing

adjustments.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Associate Professor Bo Ma

(Department of Traditional Chinese Medicine, The First People's

Hospital of Sishui County, Jining, China) for lending the QUS bone

ultrasonometer. The authors also thank Ms. Tianru Ruan, Nanjing

Kejing Industrial Co., Ltd. (Nanjing, Jiangsu, China) for technical

support in data retrieval of QUS. The authors also thank Ms Goh Li

Lian (School of Medicine, IMU University, Bukit Jalil, Selangor,

Malaysia) for assistance in the literature search.

Funding

Funding: Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia funded the study via the

Fundamental Research Grant (grant no. FF-2024-403).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

KYC, NM, SKW, TRJ and SA were involved in the

conceptualisation of the study and acquired funding. KYC, WjZ, YW,

XJ and YG performed data curation. KYC performed formal analysis,

project administration and supervision. WjZ, WzZ, KYC, XM, HSTS,

SOE, YW, XJ and YG performed investigations. KYC, NM, SKW, TRJ and

SA were responsible for methodology. WjZ, WzZ and XM provided

resources. WjZ, WzZ and KYC wrote the original draft. NM, SKW, TRJ

and SA reviewed and edited the manuscript. KYC and WjZ confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. All authors have read and

approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia Ethics Committee

approved the present study (Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia; approval no:

JEP-2024-739) and participants provided informed consent prior to

participation.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Use of artificial intelligence tools

During the preparation of this work, artificial

intelligence tools [ChatGPT 3.0 (OpenAI)] were used to improve the

readability and language of the manuscript, and subsequently, the

authors revised and edited the content produced by the artificial

intelligence tools as necessary, taking full responsibility for the

ultimate content of the present manuscript.

References

|

1

|

Chin KY, Ng BN, Rostam MKI, Muhammad

Fadzil NFD, Raman V, Mohamed Yunus F, Syed Hashim SA and Ekeuku SO:

A mini review on osteoporosis: From biology to pharmacological

management of bone loss. J Clin Med. 11(6434)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Chin KY and Ima-Nirwana S: Calcaneal

quantitative ultrasound as a determinant of bone health status:

What properties of bone does it reflect? Int J Med Sci.

10:1778–1783. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Jiang Y, Wu H, Yang D, Wang W, Chu J, Tang

J and Yao X: Diagnostic value of quantitative ultrasound for

osteoporosis in elderly women: A meta-analysis. Altern Ther Health

Med. 30:226–231. 2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Subramaniam S, Chan CY, Soelaiman IN,

Mohamed N, Muhammad N, Ahmad F, Ng PY, Jamil NA, Aziz NA and Chin

KY: The performance of a calcaneal quantitative ultrasound device,

CM-200, in stratifying osteoporosis risk among malaysian population

aged 40 years and above. Diagnostics (Basel).

10(178)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Fu Y, Li C, Luo W, Chen Z, Liu Z and Ding

Y: Fragility fracture discriminative ability of radius quantitative

ultrasound: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoporos Int.

32:23–38. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Olmos JM, Hernández JL, Pariente E,

Martínez J, Valero C and González-Macías J: Trabecular bone score

and bone quantitative ultrasound in Spanish postmenopausal women.

The Camargo Cohort Study. Maturitas. 132:24–29. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Liu Y, Huang X, Tang K, Wu J, Zhou J, Bai

H, Zhou L, Shan S, Luo Z, Cao J, et al: Prevalence of osteoporosis

and associated factors among Chinese adults: A systematic review

and modelling study. J Glob Health. 15(04009)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Tong X, Cui S, Shen H and Yao XI:

Developing and validating a nomogram prediction model for

osteoporosis risk in the UK biobank: A national prospective cohort.

BMC Public Health. 25(1263)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Park SM, Park J, Han S, Jang HD, Hong JY,

Han K, Kim HJ and Yeom JS: Underweight and risk of fractures in

adults over 40 years using the nationwide claims database. Sci Rep.

13(8013)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Ma Q, Miri Z, Haugen HJ, Moghanian A and

Loca D: Significance of mechanical loading in bone fracture

healing, bone regeneration, and vascularization. J Tissue Eng.

14(20417314231172573)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Liu Y, Liu Y, Huang Y, Le S, Jiang H, Ruan

B, Ao X, Shi X, Fu X and Wang S: The effect of overweight or

obesity on osteoporosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis.

Clin Nutr. 42:2457–2467. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Sweatt K, Garvey WT and Martins C:

Strengths and limitations of BMI in the diagnosis of obesity: What

is the path forward? Curr Obes Rep. 13:584–595. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Hou J, He C, He W, Yang M, Luo X and Li C:

Obesity and bone health: A complex link. Front Cell Dev Biol.

8(600181)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Gkastaris K, Goulis DG, Potoupnis M,

Anastasilakis AD and Kapetanos G: Obesity, osteoporosis and bone

metabolism. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact. 20:372–381.

2020.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Steiner BM and Berry DC: The regulation of

adipose tissue health by estrogens. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne).

13(889923)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Ravindran S, Wong SK, Mohamad NV and Chin

KY: A review of the relationship between insulin and bone health.

Biomedicines. 13(1504)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Shu L, Fu Y and Sun H: The association

between common serum adipokines levels and postmenopausal

osteoporosis: A meta-analysis. J Cell Mol Med. 26:4333–4342.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Tariq S, Tariq S, Khaliq S and Lone KP:

Serum resistin levels and related genetic variants are associated

with bone mineral density in postmenopausal women. Front Endocrinol

(Lausanne). 13(868120)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Cosme D and Gomes AC: Leptin levels and

bone mineral density: A friend or a foe for bone loss? A systematic

review of the association between leptin levels and low bone

mineral density. Int J Mol Sci. 26(2066)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Nevill AM, Duncan MJ and Myers T: BMI is

dead; long live waist-circumference indices: But which index should

we choose to predict cardio-metabolic risk? Nutr Metab Cardiovasc

Dis. 32:1642–1650. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Cheng CH, Ho CC, Yang CF, Huang YC, Lai CH

and Liaw YP: Waist-to-hip ratio is a better anthropometric index

than body mass index for predicting the risk of type 2 diabetes in

Taiwanese population. Nutr Res. 30:585–593. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Tewari A, Kumar G, Maheshwari A, Tewari V

and Tewari J: Comparative evaluation of waist-to-height ratio and

BMI in predicting adverse cardiovascular outcome in people with

diabetes: A systematic review. Cureus. 15(e38801)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Bertoli S, Leone A, Krakauer NY, Bedogni

G, Vanzulli A, Redaelli VI, De Amicis R, Vignati L, Krakauer JC and

Battezzati A: Association of Body Shape Index (ABSI) with

cardio-metabolic risk factors: A cross-sectional study of 6081

Caucasian adults. PLoS One. 12(e0185013)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Xu J, Zhang L, Wu Q, Zhou Y, Jin Z, Li Z

and Zhu Y: Body roundness index is a superior indicator to

associate with the cardio-metabolic risk: Evidence from a

cross-sectional study with 17,000 Eastern-China adults. BMC

Cardiovasc Disord. 21(97)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Kheirouri S and Alizadeh M: Contribution

of body adiposity index and conicity index in prediction of

metabolic syndrome risk and components. Human Nutrition &

Metabolism. 38(200290)2024.

|

|

26

|

Wu J and Wu G: Association between a body

shape index and bone mineral density in US adults based on NHANES

data. Sci Rep. 15(2817)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Wu M, Lu B, Wang Y, Zhang A, Zhou X, Zeng

X, Zhu Y, Chen S and Lin R: The association between A in body shape

index and total bone mineral density adults aged 20 to 59 NHANES

2011 to 2018. Medicine (Baltimore). 104(e42652)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Zhang M, Hou Y, Ren X, Cai Y, Wang J and

Chen O: Association of a body shape index with femur bone mineral

density among older adults: NHANES 2007-2018. Arch Osteoporos.

19(63)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Li H, Qiu J, Gao Z, Li C and Chu J:

Association between waist-to-height ratio and osteoporosis in the

National health and nutrition examination survey: A cross-sectional

study. Front Med (Lausanne). 11(1486611)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Niu HG, Hu GK, Li T, Guo Z, Hu Y, Gong YK,

Ye GQ, Chen DJ, An JL and Gao WS: Association of a body shape index

with bone mineral density and osteoporosis among U.S. adults:

Evidence from NHANES. Calcif Tissue Int. 116(76)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Zhang X, Liang J, Luo H, Zhang H, Xiang J,

Guo L and Zhu X: The association between body roundness index and

osteoporosis in American adults: Analysis from NHANES dataset.

Front Nutr. 11(1461540)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Ding Z, Zhuang Z, Tang R, Qu X, Huang Z,

Sun M and Yuan F: Negative association between body roundness index

and bone mineral density: Insights from NHANES. Front Nutr.

11(1448938)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Deng G, Yin L, Li K, Hu B, Cheng X, Wang

L, Zhang Y, Xu L, Xu S, Zhu L, et al: Relationships between

anthropometric adiposity indexes and bone mineral density in a

cross-sectional Chinese study. Spine J. 21:332–342. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Zhao X, Sun J, Xin S and Zhang X:

Association between new anthropometric indices and osteoporosis in

Chinese postmenopausal women-retrospective study based on

hospitalized patients in China. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne).

16(1535540)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Xiong MF, He P, Chen YH, Cao RR and Lei

SF: The effect of a body shape index (ABSI) and its interaction

with low estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) on

osteoporosis in elderly Chinese. J Orthop Sci. 29:262–267.

2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Kim B, Kim GM, Kim E, Park J, Isobe T,

Mori Y and Oh S: The anthropometric measure ‘a body shape index’

may predict the risk of osteoporosis in middle-aged and older

Korean people. Int J Environ Res Public Health.

19(4926)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Murat S, Dogruoz Karatekin B, Demirdag F

and Kolbasi EN: Anthropometric and body composition measurements

related to osteoporosis in geriatric population. Medeni Med J.

36:294–301. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Abdullah JM, Ismail A and Yusoff MSB:

Healthy ageing in Malaysia by 2030: Needs, challenges and future

directions. Malays J Med Sci. 31:1–13. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Tee ES and Voon SH: Combating obesity in

Southeast Asia countries: Current status and the way forward. J

Glob' Health. 8:147–151. 2024.

|

|

40

|

Chan CY, Subramaniam S, Mohamed N,

Ima-Nirwana S, Muhammad N, Fairus A, Ng PY, Jamil NA, Abd Aziz N

and Chin KY: Determinants of bone health status in a multi-ethnic

population in klang valley, Malaysia. Int J Environ Res Public

Health. 17(384)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Weir CB and Jan A: BMI Classification

Percentile And Cut Off Points. Journal 2023.

|

|

42

|

Obesity in Asia Collaboration. Is central

obesity a better discriminator of the risk of hypertension than

body mass index in ethnically diverse populations? J Hypertens.

26:169–177. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Ashwell M, Gunn P and Gibson S:

Waist-to-height ratio is a better screening tool than waist

circumference and BMI for adult cardiometabolic risk factors:

Systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 13:275–286.

2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Tao L, Miao L, Guo YJ, Liu YL, Xiao LH and

Yang ZJ: Associations of body roundness index with cardiovascular

and all-cause mortality: NHANES 2001-2018. J Hum Hypertens.

38:120–127. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Martins CA, do Prado CB, Santos Ferreira

JR, Cattafesta M, Dos Santos Neto ET, Haraguchi FK, Marques-Rocha

JL and Salaroli LB: Conicity index as an indicator of abdominal

obesity in individuals with chronic kidney disease on hemodialysis.

PLoS One. 18(e0284059)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Chin KY, Soelaiman IN, Mohamed IN, Ibrahim

S and Wan Ngah WZ: The effects of age, physical activity level, and

body anthropometry on calcaneal speed of sound value in men. Arch

Osteoporos. 7:135–145. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Song J, Zhang R, Lv L, Liang J, Wang W,

Liu R and Dang X: The relationship between body mass index and bone

mineral density: A mendelian randomization study. Calcif Tissue

Int. 107:440–445. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Kaze AD, Rosen HN and Paik JM: A

meta-analysis of the association between body mass index and risk

of vertebral fracture. Osteoporos Int. 29:31–39. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Kusuman K, Wiryadana KA, Setiawan IMB and

Rante SDT: Body mass index inversely associated with bone

microarchitecture quality: A systematic review and meta-analysis.

IJBS. 16:28–33. 2022.

|

|

50

|

Chen R, Zhao W, Cai P, Peng C and Liu H:

The association between body roundness index and risk of

osteoporosis in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A

cross-sectional study based on NHANES database. J Orthop Surg (Hong

Kong). 33(10225536251356804)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Tian N, Chen S, Han H, Jin J and Li Z:

Association between triglyceride glucose index and total bone

mineral density: A cross-sectional study from NHANES 2011-2018. Sci

Rep. 14(4208)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Chen PJ, Lu YC, Lu SN, Liang FW and Chuang

HY: Association between osteoporosis and adiposity index reveals

nonlinearity among postmenopausal women and linearity among men

aged over 50 years. J Epidemiol Glob Health. 14:1202–1218.

2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Zhang J, Wang Y, Guo J, Liu H, Lei Z,

Cheng S and Cao H: The association between ten anthropometric

measures and osteoporosis and osteopenia among postmenopausal

women. Sci Rep. 15(10994)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Zhao Z, Ji H, Liu W, Wang Z, Ren S, Liu C,

Wu C, Wang J and Ding X: The saturation effect of a body shape

index on lumbar bone mineral density in US adults: Findings from a

nationwide survey. PLoS One. 20(e0324160)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Ryotaro B, Masahiro A, Norihiko O, Nakano

Y, Takeuchi T, Murakami M, Sasahara Y, Numasawa M, Minami I,

Izumiyama H, et al: Indirect measure of visceral adiposity ‘A Body

Shape Index’ (ABSI) is associated with arterial stiffness in

patients with type 2 diabetes. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care.

4(e000188)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Yu JY, Choi WJ, Lee HS and Lee JW:

Relationship between inflammatory markers and visceral obesity in

obese and overweight Korean adults: An observational study.

Medicine (Baltimore). 98(e14740)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Hetemäki N, Savolainen-Peltonen H,

Tikkanen MJ, Wang F, Paatela H, Hämäläinen E, Turpeinen U, Haanpää

M, Vihma V and Mikkola TS: Estrogen metabolism in abdominal

subcutaneous and visceral adipose tissue in postmenopausal women. J

Clin Endocrinol Metab. 102:4588–4595. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|