Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a

chronic lung condition marked by ongoing respiratory symptoms and

reduced airflow (1). Beyond the

immediate respiratory compromise, acute exacerbations of COPD

(AE-COPD) trigger a potent systemic inflammatory response, creating

a prothrombotic state that markedly elevates the risk of venous

thromboembolism (VTE), including deep vein thrombosis (DVT)

(2,3). The concurrence of DVT in patients

with AE-COPD is not a minor complication; it is a critical event

associated with a notable increase in short- and long-term

mortality. A study indicated that the 1-year mortality rate of

AE-COPD patients with VTE was significantly higher than that of

patients without VTE (12.9 vs. 4.5%) (2). In addition to acquired risk factors,

underlying hereditary thrombophilias may contribute to VTE risk, as

highlighted in patients with unprovoked pulmonary embolism

(4), highlighting the complexity

of thrombotic risk in inflammatory diseases such as AE-COPD,

thereby emphasizing the urgent need for effective risk

stratification.

Platelets play a crucial role not only in hemostasis

and thrombosis but also in immune and inflammatory responses; they

participate in the activation of the coagulation cascade and

interact with immune cells such as neutrophils, monocytes and

lymphocytes, promoting cellular activation (5-7).

During an AE-COPD episode, systemic inflammation leads to

widespread platelet activation, which in turn amplifies the

inflammatory cascade and promotes a hypercoagulable state. This

dual role of platelets provides a crucial mechanistic link between

the inflammatory surge of an exacerbation and the subsequent risk

of thrombosis. Consequently, abnormalities in platelet counts are

common in AE-COPD and serve as important prognostic indicators

(8). Thrombocytosis (platelet

count >400x109/l) is a well-documented phenomenon

associated with the severity of exacerbations and an independent

predictor of adverse outcomes (9),

consistent with its established role in promoting thrombosis.

However, a previous study found that a decrease in platelet count

was associated with an increased risk of AE-COPD over 2 years,

suggesting that platelet levels may serve as a predictive marker

for COPD exacerbation risk (10).

A more complex and clinically challenging scenario arises in a

marked subset of patients, particularly those with severe,

infection-driven exacerbations, who present with

thrombocytopenia.

The development of thrombocytopenia in this context

is not a passive event but rather a dynamic biomarker reflecting a

dysregulated host response to severe infection, the primary trigger

for most AE-COPD events. The occurrence of thrombocytopenia

signifies an advanced state of systemic inflammation where

accelerated platelet consumption, sequestration and impaired bone

marrow production occur. This leads to a critical clinical

conundrum known as the ‘thrombocytopenia-thrombosis paradox’

(8). While a low platelet count is

traditionally viewed as a risk factor for bleeding, in pathological

states of severe inflammation, such as sepsis or disseminated

intravascular coagulation, it is paradoxically associated with a

heightened risk of microvascular and macrovascular thrombosis

(11). This occurs as the low

platelet count is a direct consequence of the widespread activation

and consumption of platelets in the formation of thrombi, driven by

endothelial injury and systemic inflammation. This paradox presents

a formidable challenge for clinicians managing patients with

AE-COPD (12). The presence of

infection-induced thrombocytopenia obscures the true thrombotic

risk, creating a dilemma where the need to prevent potentially

fatal thrombotic events must be weighed against a perceived risk of

major bleeding.

Current risk assessment models for VTE are not

specifically designed for this patient population and often fail to

account for the complex interplay between inflammation, infection

severity and platelet dysregulation. Therefore, a clear gap exists

in the ability to accurately risk-stratify patients with AE-COPD,

particularly those with thrombocytopenia, for the development of

DVT. To address this, the aim of the current study was to explore

the intricate association between thrombocytopenia, the severity of

the underlying infection and the incidence of DVT in patients

hospitalized with AE-COPD. It was hypothesized that a composite

model that integrates biomarkers reflecting both the inflammatory

state, platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR) and downstream

coagulation activation (D-dimer), can more accurately predict DVT

risk in this vulnerable population. The development of such a model

would provide a valuable tool for clinical decision-making,

enabling targeted prophylactic strategies and ultimately improving

outcomes for patients with AE-COPD.

Patients and methods

Subjects

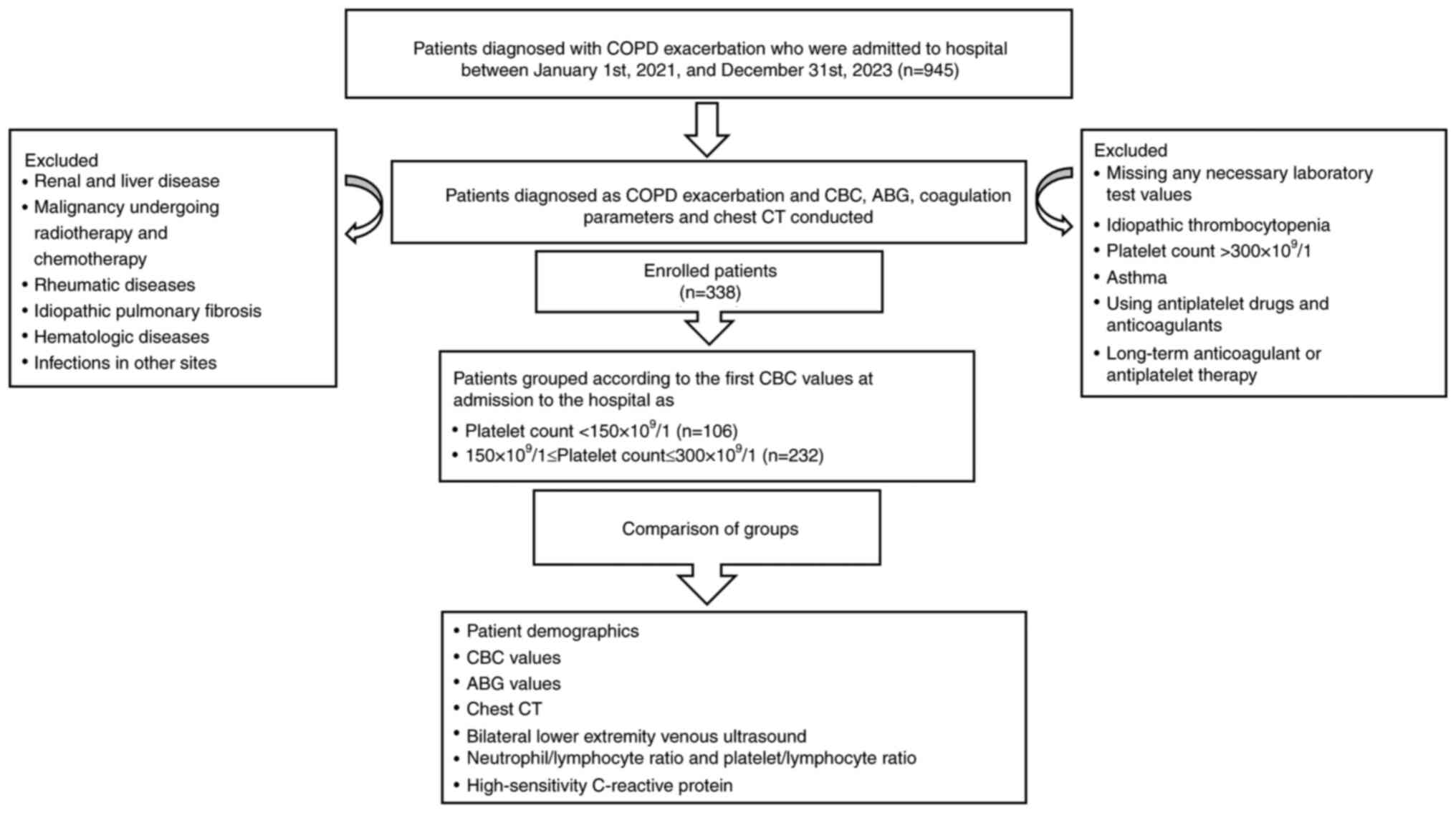

The selection process and design of the present

study are shown in Fig. 1. The

medical records of patients with AE-COPD (n=945) who were

hospitalized in the Department of Respiratory and Critical Care

Medicine at The Affiliated Jiangning Hospital of Nanjing Medical

University (Nanjing, China) between January 2021 and December 2023

were retrospectively reviewed. All enrolled patients underwent a

chest computed tomography (CT) scan. The CT findings were utilized

to confirm the presence and assess the severity of pulmonary

infection, such as the pulmonary infiltrates of infection analyzed

in the manuscript. This provided objective radiological support for

the clinical diagnosis. To ensure that the present study focused

specifically on the systemic response driven by pulmonary

pathology, patients with definitive, active non-pulmonary

infections at the time of admission were excluded. This exclusion

process was based on a comprehensive review of each patient's

electronic medical record, which included, but was not limited to

the following: i) Reviewing the attending physician's diagnostic

records to rule out infections at other sites, such as urinary

tract infections, skin and soft tissue infections or

intra-abdominal infections; and ii) scrutinizing relevant

laboratory results (for example, urinalysis and procalcitonin) and

imaging studies from other body regions (for example, abdominal

ultrasound). All patients had peripheral blood drawn and underwent

a systematic vascular ultrasound of both lower extremities within

24 h of admission, before starting anticoagulant therapy. Bilateral

lower extremity vascular ultrasound screening is actually routinely

performed for all patients with AE-COPD within The Affiliated

Jiangning Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, regardless of

their symptoms. COPD was diagnosed based on clinical presentations,

pulmonary function tests and chest CT scans. The Padua Prediction

Score (including immobility status, recent surgery, prior VTE

history, history of cancer and corticosteroid use) was calculated

for each patient with AE-COPD (13). The specific diagnostic criteria

included: i) A previous pulmonary function test showing a

post-bronchodilator forced expiratory volume in 1 sec/forced vital

capacity value of <0.70, indicating irreversible airflow

limitation; ii) chest CT showing signs of emphysema; and iii)

AE-COPD defined as symptoms such as worsening dyspnea, increased

sputum volume and yellow sputum, requiring a change in the current

treatment regimen. The exclusion criteria were: i) Severe renal and

liver diseases; ii) a history of malignancy undergoing radiotherapy

or chemotherapy; iii) rheumatic diseases; iv) idiopathic pulmonary

fibrosis; v) bronchial asthma; vi) long-term use of oral

antiplatelet and anticoagulant drugs; vii) hematological diseases;

viii) infections in other sites; ix) missing essential laboratory

test results; and x) anticoagulant therapy initiation before blood

samples were obtained and a lower extremity venous ultrasound was

performed. Ultimately, 338 patients with AE-COPD were included in

the present study, with an age range of 57-93 years and a median

age of 75 years.

Data collection and assessment

Relevant clinical information was collected from the

patients' hospitalization records. If multiple repeated tests were

conducted during hospitalization, the results from the first test

upon admission were selected. Data on the demographic

characteristics, medical history, comorbidities, laboratory tests,

bilateral lower limb venous ultrasound examinations, chest CT scans

and mechanical ventilation treatment of patients with AE-COPD were

collected. The PLR was calculated as the platelet count divided by

the lymphocyte count. The neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) was

calculated as the neutrophil count divided by the lymphocyte count.

The D-dimer-to-lymphocyte ratio (DLR) was calculated as the D-dimer

level divided by the lymphocyte count. Based on the platelet count

at the time of admission, patients were divided into the

thrombocytopenia group (<150x109 cells/l) and the

normal platelet count group (≥150 to <300x109

cells/l) (14).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS

(version 26.0; IBM Corp.), GraphPad Prism (version 9.0; Dotmatics)

and the R (version 4.1.3; R Core Team). Normality of all continuous

variables was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Quantitative

data conforming to a normal distribution are presented as the mean

± standard deviation and were compared between groups using an

unpaired Student's t-test. Non-normally distributed continuous

variables are presented as median (interquartile range) and were

compared using the Mann-Whitney U test. Categorical variables are

described using frequencies (percentages) and were compared using

the χ2 test. Correlation analysis between two continuous

variables was conducted using Spearman's correlation coefficient.

Subgroup analyses were performed to assess intergroup associations

and thrombosis risk within different subgroups. Univariate and

multivariate analyses were conducted using binary logistic

regression. Discrimination in the prediction model was assessed

using the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve

(AUC-ROC). Bootstrap ROC was used to evaluate the performance of

the prediction model. Two-sided P<0.05 was considered to

indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Patient demographics and clinical

characteristics

As shown in Table

I, 338 patients with AE-COPD were included, with 72.4% being

male and with an overall mean age of 75.60±7.42 years. Among these,

106 patients had platelet counts <150x109 cells/l,

and 232 patients had platelet counts of 150-300x109

cells/l. The body mass index (BMI) of patients in the

thrombocytopenia group was significantly lower than that of

patients in the normal platelet count group (P=0.039). There were

no significant statistical differences between the two groups

regarding age, smoking history sex and Padua prediction score.

| Table ISociodemographics of patients with

acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. |

Table I

Sociodemographics of patients with

acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

| Factors | Thrombocytopenia | Normal platelets | P-value |

|---|

| Total patients,

n | 106 | 232 | - |

| Age, years | 73.60±7.18 | 76.60±7.35 | 0.448 |

| Male, n (%) | 83 (78.3) | 162 (69.8) | 0.106 |

| Smoking history, n

(%) | 51 (48.1) | 86 (37.1) | 0.055 |

| BMI,

kg/m2 | 21.32±3.51 | 22.24±3.92 | 0.039a |

| Padua prediction

score | 3.43±1.86 | 3.71±1.81 | 0.196 |

Laboratory results (Table II) showed that the

thrombocytopenia group had a significantly lower white blood cell

count (WBC; P<0.001), neutrophil count (P<0.001) and monocyte

count (P<0.001), as well as lower PLR (P<0.001) and

plateletcrit (P=0.014), compared with the normal platelet group,

with no other results showing statistical significance.

| Table IILaboratory data of patients with

acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. |

Table II

Laboratory data of patients with

acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

| Factors | Reference

range |

Thrombocytopenia | Normal

platelets | P-value |

|---|

| WBC count,

x109/l | 3.5-9.5 | 5.8 (2.9) | 7.77 (4.33) |

<0.001a |

| Red blood cell

count, x1012/l | | | | |

|

Male | 4.3-5.8 | 4.20 (0.88) | 4.36 (0.89) | 0.258 |

|

Female | 3.8-5.1 | 4.03 (0.83) | 4.34 (0.68) | 0.252 |

| Neutrophil count,

x109/l | 1.8-6.3 | 4.4 (3.09) | 6.5 (4.22) |

<0.001a |

| Neutrophils, % | 40-75 | 78.9 (16.35) | 80.2 (15.17) | 0.231 |

| Lymphocyte count,

x109/l | 1.1-3.2 | 0.72 (0.59) | 0.9 (0.64) | 0.460 |

| Lymphocytes, % | 20-50 | 13.20 (13.4) | 11.2 (9.7) | 0.191 |

| Monocyte count,

x109/l | 0.1-0.6 | 0.40 (0.22) | 0.54 (0.45) |

<0.001a |

| Monocytes, % | 3-10 | 6.58±2.75 | 6.50±3.78 | 0.888 |

| PLR | - | 150.0 (116.6) | 230.97 (172.6) |

<0.001a |

| NLR | - | 6.16 (8.00) | 7.07 (7.13) | 0.164 |

| DLR | - | 0.85 (1.11) | 0.78 (1.44) | 0.528 |

| MPV, fl | 7.4-12.5 | 10.92±1.41 | 10.78±1.49 | 0.534 |

| PDW, % | 12-16.5 | 15.2 (3.6) | 14.4 (4.7) | 0.120 |

| Plateletcrit,

% | 0.11-0.28 | 0.19 (0.09) | 0.21 (0.08) | 0.014b |

| Hemoglobin,

mmol/l | | | | |

|

Male | 8.1-10.9 | 7.94±1.10 | 8.06±1.09 | 0.390 |

|

Female | 7.1-9.3 | 7.88±1.06 | 7.74±1.05 | 0.588 |

| Hs-CRP, mg/l | 0.95-95.2 | 84.1 (404.2) | 100.3 (583.4) | 0.285 |

| Procalcitonin,

pmol/l | 0.0-38.5 | 4.6 (10.8) | 5.4 (13.1) | 0.318 |

| D-dimer,

µmol/l | 0.0-3.06 | 3.50 (3.06) | 3.89 (5.78) | 0.052 |

| FBG-G, g/l | 5.9-11.8 | 10.47 (3.59) | 10.58 (5.38) | 0.823 |

| TT, sec | 14-21 | 14.3 (2.15) | 14.1 (1.9) | 0.408 |

| PT, sec | 9-15 | 11.9 (2.0) | 12 (1.7) | 0.943 |

| APTT, sec | 20-40 | 32.3 (4.1) | 31.8 (5.1) | 0.132 |

| INR, % | 0.8-1.2 | 1.1 (0.16) | 1.11 (0.16) | 0.764 |

| OI, mmHg | 300-500 | 313.8±78.0 | 313.2±98.11 | 0.960 |

| PaCO2,

mmHg | 35-45 | 46 (17.5) | 45 (19.9) | 0.241 |

| Pathogen positivity

rate of sputum, n (%) | Negative | 21 (19.8) | 61 (26.3) | 0.197 |

Comparison of comorbidities and

changes in clinical status upon admission and discharge in the two

groups

As shown in Table

III, there were no statistically significant differences in the

proportions of arrhythmias, cor pulmonale, respiratory failure,

assisted ventilation, hypertension and diabetes between the

thrombocytopenia group and the normal platelet group among patients

with AE-COPD. However, the ratio of patients with cardiovascular

diseases (CVDs) was 33.0% in the thrombocytopenia group compared

with 44.4% in the normal platelet group, a difference that was

statistically significant (P=0.048). The incidence of DVT during

hospitalization was significantly lower in the thrombocytopenia

group than in the normal platelet group (4.7 vs. 12.5%; P=0.027).

While there was no significant difference in the overall pulmonary

infiltrate rates between the two groups, the percentage of patients

with pulmonary confluent infiltrates infections was significantly

higher in the thrombocytopenia group than in the normal platelets

group (43.4 vs. 17.7%; P<0.001). The analysis revealed the

following results: None vs. patchy infiltrates, P=0.198; none vs.

confluent infiltrates, P<0.001; and patchy infiltrates vs.

confluent infiltrates, P<0.001.

| Table IIIComparison of comorbidities and

changes in clinical status upon admission and discharge. |

Table III

Comparison of comorbidities and

changes in clinical status upon admission and discharge.

| Factors |

Thrombocytopenia | Normal

platelets | P-value |

|---|

| Patient number | 106 | 232 | - |

| Arrhythmia, n

(%) | 19 (17.9) | 78 (33.6) | 0.810 |

| Assisted

ventilation, n (%) | 19 (17.9) | 39 (16.8) | 0.951 |

| Respiratory

failure, n (%) | 62 (58.5) | 129 (55.6) | 0.619 |

| Hypertension, n

(%) | 53 (50.0) | 116 (50.0) | 1.000 |

| Diabetes, n

(%) | 16 (15.1) | 34 (14.7) | 0.916 |

| CVD, n (%) | 35 (33.0) | 103 (44.4) | 0.048a |

| Pulmonary

infection, n (%) | 86 (81.1) | 170 (74.6) | 0.118 |

| Cor pulmonale, n

(%) | 43 (40.6) | 79 (34.1) | 0.247 |

| DVT, n (%) | 5 (4.7) | 29 (12.5) | 0.027a |

| Pulmonary

infiltrates of infection, n (%)c | | |

<0.001b |

|

None | 20 (18.9) | 62 (26.7) | |

|

Patchy

infiltrates | 40 (37.7) | 129 (55.6) | |

|

Confluent

infiltrates | 46 (43.4) | 41 (17.7) | |

Correlation between laboratory

measurements in the two groups

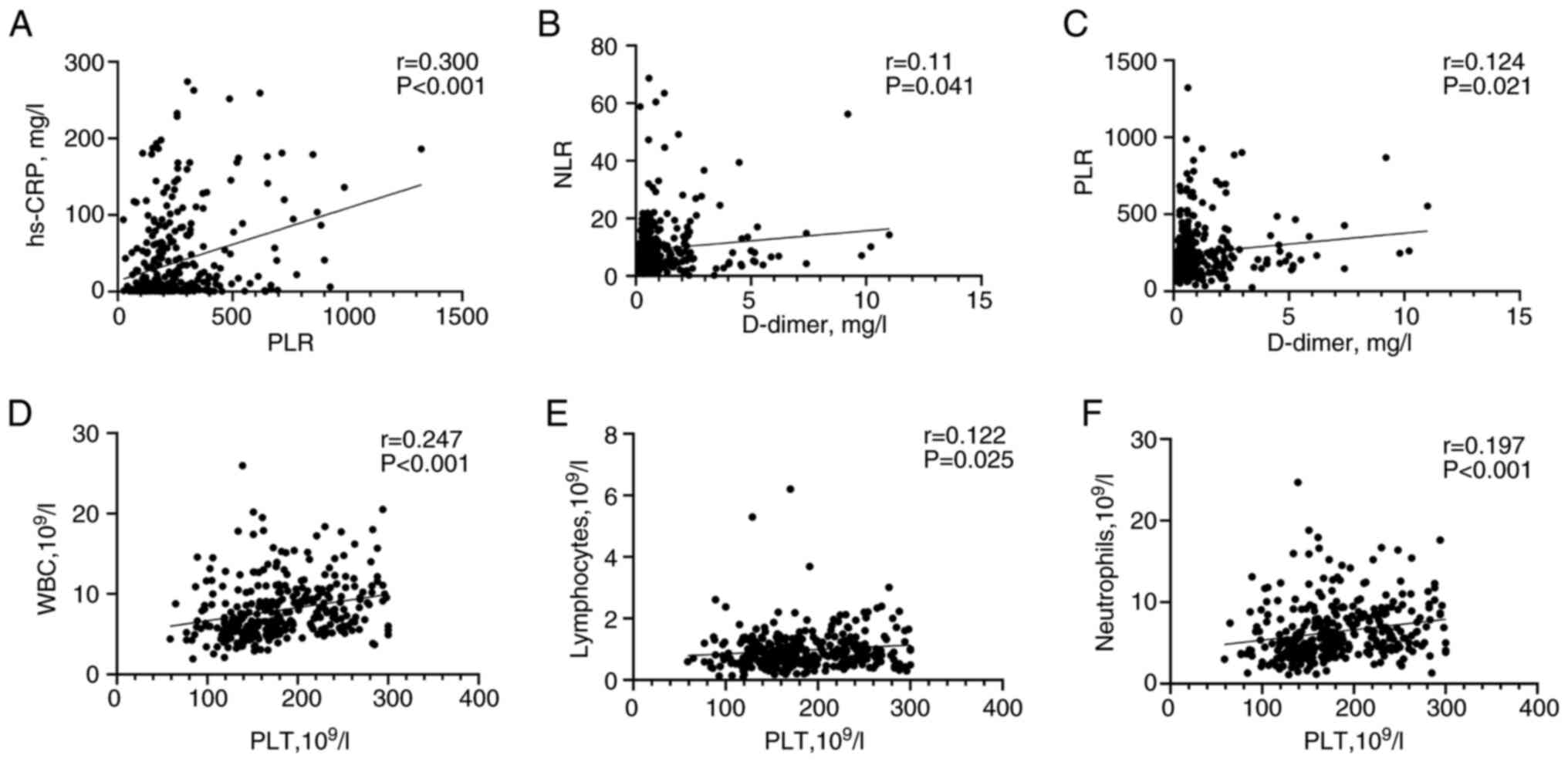

The results of the correlation analysis between

platelet parameters, coagulation markers and infection indicators

in patients with AE-COPD are shown in Fig. 2. The correlations were weak, with

PLR being positively correlated with high sensitivity C-reactive

protein (r=0.300; P<0.001; Fig.

2A), and with D-dimer being positively correlated with NLR

(r=0.110; P=0.041; Fig. 2B) and

PLR (r=0.124; P=0.021; Fig. 2C),

all showing statistical significance. Additionally, platelet count

was positively significantly correlated with WBC (r=0.247;

P<0.001; Fig. 2D), lymphocyte

count (r=0.122; P<0.025; Fig.

2E) and neutrophil count (r=0.197; P<0.001; Fig. 2F).

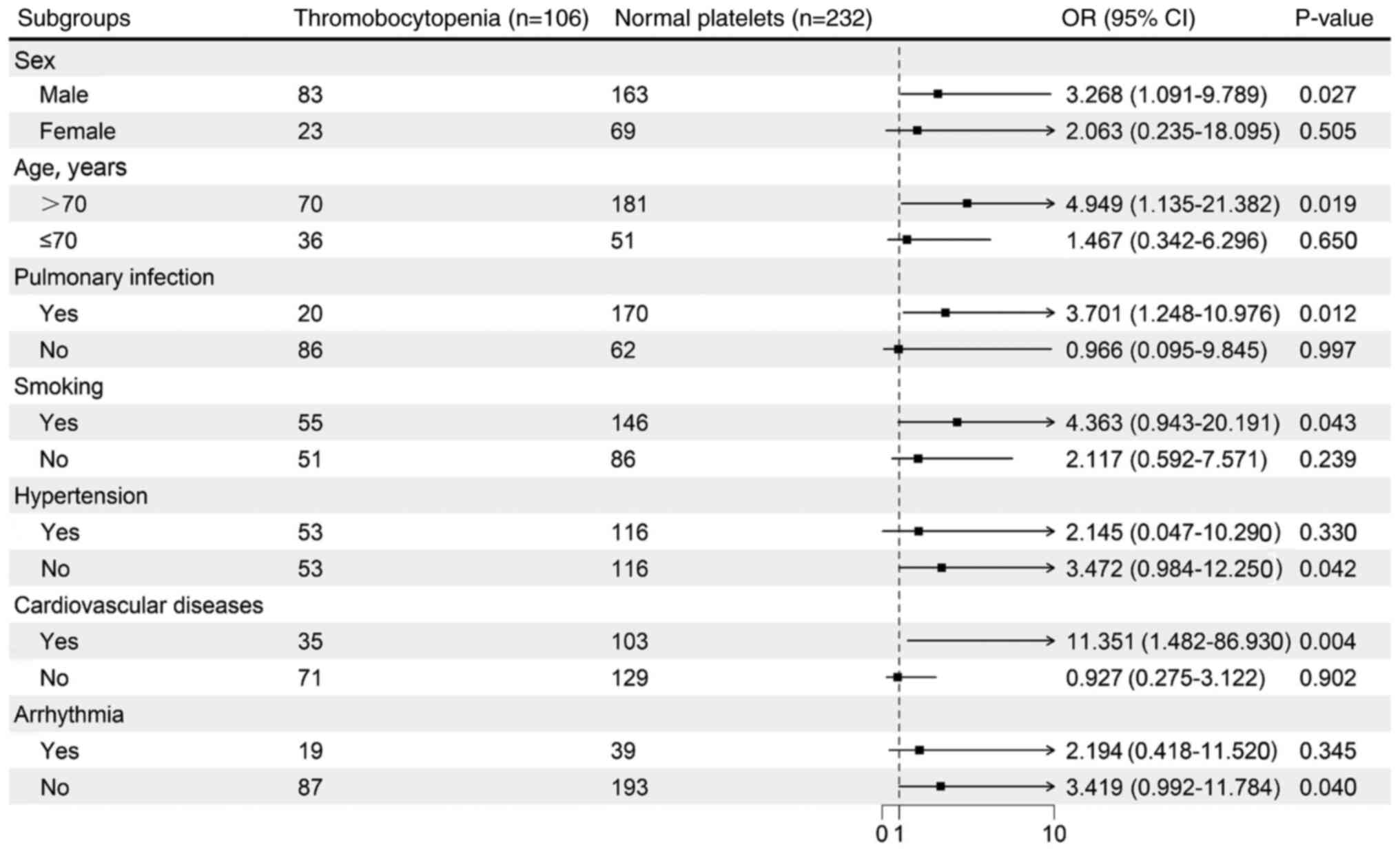

Subgroup analysis

A forest plot was used to perform stratified

analysis of DVT risk. In most subgroups, the risk of DVT was lower

in the thrombocytopenia group compared with that in the normal

platelet group. Notably, in the subgroup of males who were >70

years old with CVD and concurrent pulmonary infection, patients

with AE-COPD in the normal platelet group had a higher risk of DVT

(Fig. 3).

Risk factors associated with DVT

development in patients with AE-COPD

Initially, a univariate logistic regression analysis

was performed to identify the variables influencing thrombus

formation during hospitalization in patients with AE-COPD.

Significant indicators identified include platelet count (P=0.130),

normal platelets (P=0.875), lymphocyte count (P=0.845), lymphocyte

percentage (P=0.723), monocyte percentage (P=0.366), NLR (P=0.894),

PLR (P=0.012), DLR (P=0.720) and D-dimer (P=0.024) (Table IV). Subsequent multivariate

logistic regression analysis revealed that PLR [odds ratio (OR),

1.004; 95% confidence interval (CI), 1.001-1.007; P=0.012] and

D-dimer (OR, 1.454; 95% CI, 1.051-2.011; P=0.024) were independent

risk factors for thrombus formation during hospitalization of

patients with AE-COPD (Table IV).

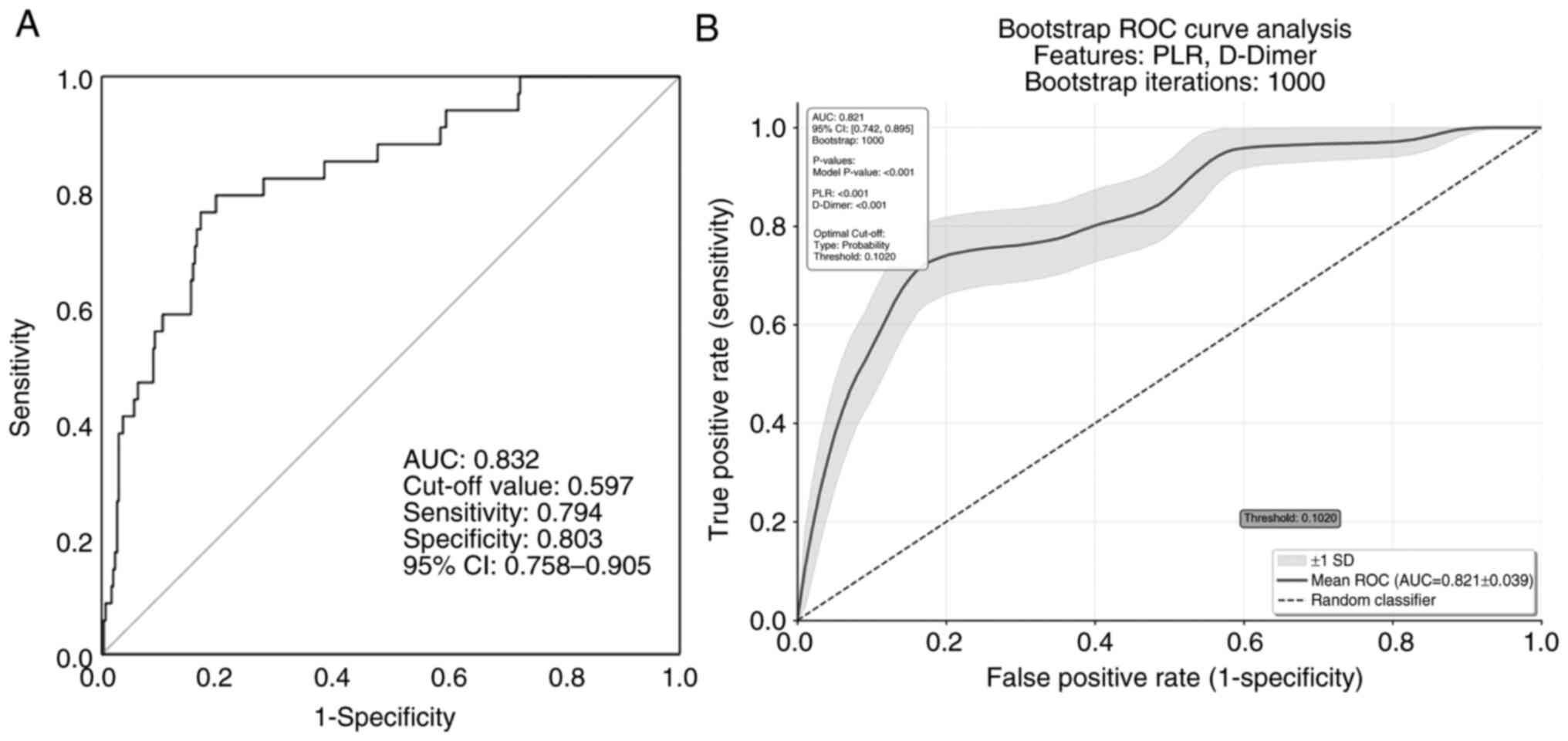

The AUC-ROC values of D-dimer and PLR were 0.802 (95% CI,

0.733-0.971; cut-off, 0.520; P=0.012) and 0.745 (95% CI,

0.649-0.841; cut-off, 408.51; P=0.024), respectively (Table V). The AUC-ROC in the model of PLR

and D-dimer in the present study was 0.832 (95% CI, 0.758-0.905;

P<0.001; Fig. 4A). Given the

small sample size, the bootstrap method was used to validate the

prediction model. After 1,000 repeated samplings, the AUC-ROC was

0.821 and the optimal cut-off was 0.1 (95% CI, 0.742-0.895;

P<0.001; Fig. 4B).

| Table IVUnivariate and multivariate logistic

regression analysis of deep vein thrombosis formation during

hospitalization in patients with acute exacerbations of chronic

obstructive pulmonary disease. |

Table IV

Univariate and multivariate logistic

regression analysis of deep vein thrombosis formation during

hospitalization in patients with acute exacerbations of chronic

obstructive pulmonary disease.

| | Univariate

analysis | Multivariate

analysis |

|---|

| Factors | OR (95% CI) | P-value | OR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|

| Platelet count,

x109/l | 1.012

(1.005-1.019) |

<0.001a | 1.009

(0.997-1.020) | 0.130 |

| Normal

platelets | 2.886

(1.085-7.678) | 0.034b | 0.891

(0.211-3.765) | 0.875 |

| Lymphocyte count,

x109/l | 0.286

(0.109-0.747) | 0.011b | 0.845

(0.183-4.014) | 0.845 |

| Lymphocytes, % | 0.934

(0.882-0.989) | 0.019b | 1.081

(0.923-1.122) | 0.723 |

| Monocytes, % | 0.867

(0.776-0.967) | 0.011b | 0.945

(0.837-1.068) | 0.366 |

| NLR | 1.043

(1.016-1.071) | 0.032b | 0.995

(0.944-1.049) | 0.894 |

| PLR | 1.004

(1.003-1.006) |

<0.001a | 1.004

(1.001-1.007) | 0.012b |

| DLR | 1.212

(1.089-1.349) |

<0.001a | 0.975

(0.846-1.123) | 0.720 |

| D-dimer, mg/l | 1.423

(1.203-1.683) |

<0.001a | 1.454

(1.051-2.011) | 0.024b |

| Table VROC curve analysis for D-dimer and

PLR. |

Table V

ROC curve analysis for D-dimer and

PLR.

| Factors | AUC-ROC | 95% CI | Cut-off | P-value |

|---|

| D-dimer, mg/l | 0.802 | 0.733-0.971 | 0.520 | 0.012b |

| PLR | 0.745 | 0.649-0.841 | 408.510 | 0.024b |

Discussion

The current study demonstrated that a diagnostic

model combining D-dimer level and PLR exhibited excellent

performance in detecting DVT in patients with AE-COPD.

Additionally, it was shown that males >70 years old with

pulmonary infections and CVDs are at higher risk of DVT.

Furthermore, thrombocytopenia may be associated with more severe

pulmonary infections, as the results confirmed that patients with

AE-COPD and thrombocytopenia were more likely to develop extensive

infiltrative infections. These findings can assist clinicians in

risk-stratifying patients upon admission to rapidly identify those

at high risk for developing thrombocytopenia.

The interplay between inflammation, platelet

activation and coagulation function has been extensively studied

(15,16). The present study found that the

incidence of DVT was significantly lower in the thrombocytopenia

group compared with that in patients with normal platelet counts

(4.7 vs. 12.5%). We speculate that this phenomenon may be related

to consumptive thrombocytopenia (17). A previous study found that 20% of

patients with AE-COPD experience thrombocytopenia, which is closely

associated with systemic infections (18). In the context of infection and

inflammation, platelets may be excessively consumed or destroyed.

Infection can cause abnormal aggregation and consumption of

platelets within the body, especially at sites of pulmonary

inflammation, further exacerbating thrombocytopenia (19). The severe inflammatory response and

infection in AE-COPD can activate the coagulation system, leading

to the formation of microthrombi within the pulmonary and systemic

microvasculature (20). This

process consumes a large number of platelets, resulting in a

decreased peripheral platelet count.

D-dimer level and PLR reflect different yet related

pathological processes. While the continuous OR from the current

regression analysis quantified the statistical risk associated with

rising D-dimer levels, a more clinically actionable insight arose

from the ROC curve analysis. This analysis identified an optimal

D-dimer cut-off of 0.520 for predicting DVT. This finding

reinforces the utility of using a standard D-dimer threshold to

identify patients with high-risk AE-COPD who may require further

diagnostic evaluation, such as lower limb venous ultrasound, even

when other traditional risk factors are not prominent. PLR

represents the inflammation-platelet activation state (an upstream

event), whereas D-dimer reflects the ultimate outcome of fibrin

formation and degradation (a downstream event) (21). The weak correlation suggests that

PLR and D-dimer may provide complementary, rather than redundant,

risk information. For instance, a high PLR might indicate that a

patient is in an intense inflammatory storm with high thrombotic

potential, even while their D-dimer level has not yet become

significantly elevated (22).

Combining these two markers may therefore offer a more

comprehensive assessment of a patient's thrombosis risk than using

either one alone. After internal validation, the optimal cut-off

value for the combined prediction model was determined to be 0.10.

In clinical practice, this model can be developed into a tool where

clinicians input a patient's D-dimer and PLR values to calculate a

predictive score. A score >0.10 would indicate a higher risk for

DVT, thereby prompting the early initiation of pharmacological and

mechanical anticoagulant therapies.

A key finding of the current study is the

discordance between absolute platelet count and thrombotic risk.

Logistic regression analysis identified D-dimer level and PLR as

independent prognostic factors for in-hospital thrombosis in

patients with AE-COPD, but it did not confirm platelet count as an

independent factor influencing DVT. In acute inflammatory diseases

such as AE-COPD, the risk of thrombosis depends not only on the

quantity of procoagulant cells but, more importantly, on the

complex interplay between the systemic inflammatory state and the

coagulation system, a concept known as immuno-thrombosis (23). The PLR, as a composite biomarker,

aptly captures the essence of this interaction; it reflects

platelet-driven prothrombotic activity (the numerator) occurring

within the context of severe systemic inflammation and

immunosuppression (the denominator). By contrast, a simple platelet

count fails to capture this critical inflammatory background, thus

limiting its predictive power. Therefore, in the context of

AE-COPD, the driving force behind DVT risk is not the absolute

number of platelets, but rather their activation state and the

host's inflammatory microenvironment, as reflected by

lymphocytopenia (24).

It is well known that PLR reflects the inflammatory

and immune status of the body, and research has shown that PLR is a

good predictor of VTE incidence, poor prognosis and mortality

(25,26). The NLR is a recognized indicator of

subclinical inflammation, with a high NLR suggesting increased

systemic inflammation and being considered a negative prognostic

factor for various arterial diseases (27,28).

Elevated NLR is markedly linked to mesenteric artery embolism and

venous thrombosis in patients with coronary artery disease

(29,30). The results of the present study

align with the findings of the study by Selvaggio et al

(31), which observed that

patients with concurrent DVT show a heightened inflammatory-immune

response, exhibiting higher NLR and PLR levels compared with those

without DVT. After adjusting for confounding factors, PLR, but not

NLR, remained notably associated with DVT (OR, 3.379). This

suggests that in acute inpatient settings, the interplay between

platelets and the immune response, captured by PLR, is a robust

indicator of thrombotic events. This conclusion somewhat

contradicts the results in the study by Artoni et al

(32), which determined that high

PLR and NLR were not generally linked to an increased risk of VTE

or cerebral venous thrombosis (CVT). However, this discrepancy is

likely attributable to fundamental differences in the study

populations. The study by Artoni et al (32) included non-acute outpatients

referred for thrombophilia screening after their first objectively

confirmed VTE or CVT episode. These patients were in a stable,

non-acute phase, whereas the current study focused exclusively on

patients during an active, inflammatory state of AE-COPD. It is

likely that the predictive value of inflammatory markers such as

PLR is most prominent during acute systemic inflammation, which

acts as a potent trigger for thrombosis. Therefore, the differing

results are not necessarily conflicting but rather highlight that

the utility of these biomarkers is context-dependent, being

particularly relevant in acutely ill, hospitalized patients.

Further research is still needed to fully elucidate these

associations.

Additionally, in the present study, it was observed

that the patients in the thrombocytopenia group had a significantly

lower BMI compared with the patients in the normal platelet count

group. COPD, being a chronic disease, is often accompanied by

malnutrition, which can result in a deficiency of key hematopoietic

nutrients, such as vitamin B12 and folic acid (33), potentially impairing bone marrow

function and resulting in reduced platelet production. This may, in

turn, lead to relatively lower D-dimer levels upon hospital

admission, which might explain the observations in the present

study. While the present study did not include specific nutritional

markers, such as serum albumin, the lower BMI in the

thrombocytopenia group suggests that poor nutritional status may be

a contributing factor, potentially leading to reduced platelet

production and relatively lower D-dimer levels upon hospital

admission. Future studies should incorporate these nutritional

assessments to further clarify their role.

However, as the present study is a retrospective

analysis, the results primarily reveal associations rather than

causal relationships. Future research should focus on validating

these findings through large-scale, prospective cohort studies and

further investigate the underlying pathophysiological mechanisms by

which these risk factors lead to thrombocytopenia, in order to

provide a scientific basis for more precise clinical interventions.

Limitations of the study include the fact that the number of DVT

cases in the thrombocytopenia group was small, which could lead to

increased variance in the statistical analysis. Additionally, the

potential influence of various hematological parameters should be

recognized. For example, protein-energy malnutrition and specific

micronutrient deficiencies, such as vitamin B12 or folate, are

known factors that can cause or exacerbate thrombocytopenia and

anemia (34). However, specific

nutritional markers other than hemoglobin were not systematically

gathered or recorded. Subsequent studies should build upon the

current results by incorporating protocols that include distinct

groups with and without the use of anticoagulants, intravenous

corticosteroids and other agents; these will allow for a more

detailed investigation into how these variables affect the

association between platelets and DVT incidence.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: This study was supported by grants from the Nanjing

Science and Technology Project (grant no. ZKX22062) and the

Affiliated Jiangning Hospital of Nanjing Medical University Youth

Innovation Scientific Research Project (grant nos. JNYYZXKY202305

and JNYYZXKY202205).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

YG and LW were responsible for data collection and

the writing of the draft manuscript. ZW, YW and QL were responsible

for statistical analysis and editing the presentation of data and

figures. XZ analyzed the data. LW and BW were responsible for

designing and planning the entire research project, as well as

reviewing and revising the manuscript. LW and BW confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. All authors have read and

approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

This study was approved by the Research Ethics

Committee of The Affiliated Jiangning Hospital of Nanjing Medical

University (Nanjing, China; approval no. 2024-03-037-K01). Informed

consent was not required for this study, as it is a retrospective

analysis utilizing de-identified clinical data without active

patient recruitment. The study adheres to the principles outlined

in The Helsinki Declaration.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Kim V and Aaron SD: What is a COPD

exacerbation? Current definitions, pitfalls, challenges and

opportunities for improvement. Eur Respir J.

52(1801261)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Liu X, Jiao X, Gong X, Nie Q, Li Y, Zhen

G, Cheng M, He J, Yuan Y and Yang Y: Prevalence, risk factor and

clinical characteristics of venous thrombus embolism in patients

with acute exacerbation of COPD: A prospective multicenter study.

Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 18:907–917. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Song YJ, Zhou ZH, Liu YK, Rao SM and Huang

YJ: Prothrombotic state in senile patients with acute exacerbations

of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease combined with respiratory

failure. Exp Ther Med. 5:1184–1188. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Gegin S, Karakaya T, Aksu EA, Özdemir B,

Özdemir L and Pazarlı AC: The distribution of hereditary risk

factors in patients with pulmonary thromboembolism without

identifiable acquired risk factors. Duzce Med J. 27:69–74.

2025.

|

|

5

|

Yan C, Wu H, Fang X, He J and Zhu F:

Platelet, a key regulator of innate and adaptive immunity. Front

Med (Lausanne). 10(1074878)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Bakogiannis C, Sachse M, Stamatelopoulos K

and Stellos K: Platelet-derived chemokines in inflammation and

atherosclerosis. Cytokine. 122(154157)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Rawish E, Nording H, Münte T and Langer

HF: Platelets as mediators of neuroinflammation and thrombosis.

Front Immunol. 11(548631)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

van der Vorm LN, Li L, Huskens D, Hulstein

JJJ, Roest M, de Groot PG, Ten Cate H, de Laat B, Remijn JA and

Simons SO: Acute exacerbations of COPD are associated with a

prothrombotic state through platelet-monocyte complexes,

endothelial activation and increased thrombin generation. Respir

Med. 171(106094)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Harrison MT, Short P, Williamson PA,

Singanayagam A, Chalmers JD and Schembri S: Thrombocytosis is

associated with increased short and long term mortality after

exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A role for

antiplatelet therapy? Thorax. 69:609–615. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Nieri D, Morani C, De Francesco M, Gaeta

R, Niceforo M, De Santis M, Giusti I, Dolo V, Daniele M, Papi A, et

al: Enhanced prothrombotic and proinflammatory activity of

circulating extracellular vesicles in acute exacerbations of

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Med.

223(107563)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Jiménez-Zarazúa O, González-Carrillo PL,

Vélez-Ramírez LN, Vélez-Ramírez LN, Alcocer-León M, Salceda-Muñoz

PAT, Palomares-Anda P, Nava-Quirino OA, Escalante-Martínez N,

Sánchez-Guzmán S and Mondragón JD: Survival in septic shock

associated with thrombocytopenia. Heart Lung. 50:268–276.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Xiang M, Wu X, Jing H, Liu L, Wang C, Wang

Y, Novakovic VA and Shi J: The impact of platelets on pulmonary

microcirculation throughout COVID-19 and its persistent activating

factors. Front Immunol. 13(955654)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Barbar S, Noventa F, Rossetto V, Ferrari

A, Brandolin B, Perlati M, De Bon E, Tormene D, Pagnan A and

Prandoni P: A risk assessment model for the identification of

hospitalized medical patients at risk for venous thromboembolism:

The Padua Prediction Score. J Thromb Haemost. 8:2450–2457.

2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Fawzy A, Anderson JA, Cowans NJ, Crim C,

Wise R, Yates JC and Hansel NN: Association of platelet count with

all-cause mortality and risk of cardiovascular and respiratory

morbidity in stable COPD. Respir Res. 20(86)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Semple JW, Italiano JE Jr and Freedman J:

Platelets and the immune continuum. Nat Rev Immunol. 11:264–274.

2011.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Nicolai L and Massberg S: Platelets as key

players in inflammation and infection. Curr Opin Hematol. 27:34–40.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Yamada S and Asakura H: How we interpret

thrombosis with thrombocytopenia syndrome? Int J Mol Sci.

25(4956)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Rahimi-Rad MH, Soltani S, Rabieepour M and

Rahimirad S: Thrombocytopenia as a marker of outcome in patients

with acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Pneumonol Alergol Pol. 83:348–351. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Thomas MR and Storey RF: The role of

platelets in inflammation. Thromb Haemost. 114:449–458.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Iba T, Umemura Y, Wada H and Levy JH:

Roles of coagulation abnormalities and microthrombosis in sepsis:

Pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Arch Med Res.

52:788–797. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Mandel J, Casari M, Stepanyan M, Martyanov

A and Deppermann C: Beyond hemostasis: Platelet Innate immune

interactions and thromboinflammation. Int J Mol Sci.

23(3868)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Wen H and Chen Y: The predictive value of

platelet to lymphocyte ratio and D-dimer to fibrinogen ratio

combined with WELLS score on lower extremity deep vein thrombosis

in young patients with cerebral hemorrhage. Neurol Sci.

42:3715–3721. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Zaid Y and Merhi Y: Implication of

platelets in immuno-thrombosis and thrombo-inflammation. Front

Cardiovasc Med. 9(863846)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Gasparyan AY, Ayvazyan L, Mukanova U,

Yessirkepov M and Kitas GD: The platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio as an

inflammatory marker in rheumatic diseases. Ann Lab Med. 39:345–357.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Xue J, Ma D, Jiang J and Liu Y: Diagnostic

and prognostic value of immune/inflammation biomarkers for venous

thromboembolism: Is it reliable for clinical practice? J Inflamm

Res. 14:5059–5077. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Yao C, Zhang Z, Yao Y, Xu X, Jiang Q and

Shi D: Predictive value of neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio and

platelet to lymphocyte ratio for acute deep vein thrombosis after

total joint arthroplasty: A retrospective study. J Orthop Surg Res.

13(40)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Kim NY, Chun DH, Kim SY, Kim NK, Baik SH,

Hong JH, Kim KS and Shin CS: Prognostic value of systemic

inflammatory indices, NLR, PLR, and MPV, for predicting 1-year

survival of patients undergoing cytoreductive surgery with HIPEC. J

Clin Med. 8(589)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Yüksel M, Yıldız A, Oylumlu M, Akyüz A,

Aydın M, Kaya H, Acet H, Polat N, Bilik MZ and Alan S: The

association between platelet/lymphocyte ratio and coronary artery

disease severity. Anatol J Cardiol. 15:640–647. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Wang S, Liu H, Wang Q, Cheng Z, Sun S,

Zhang Y, Sun X, Wang Z and Ren L: Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio

and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio are effective predictors of

prognosis in patients with acute mesenteric arterial embolism and

thrombosis. Ann Vasc Surg. 49:115–122. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Luo Q, Li X, Zhao Z, Zhao Q, Liu Z and

Yang W: Nomogram for hospital-acquired venous thromboembolism among

patients with cardiovascular diseases. Thromb J.

22(15)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Selvaggio S, Brugaletta G, Abate A, Musso

C, Romano M, Di Raimondo D, Pirera E, Dattilo G and Signorelli SS:

Platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and

monocyte-to-HDL cholesterol ratio as helpful biomarkers for

patients hospitalized for deep vein thrombosis. Int J Mol Med.

51(52)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Artoni A, Abbattista M, Bucciarelli P,

Gianniello F, Scalambrino E, Pappalardo E, Peyvandi F and

Martinelli I: Platelet to lymphocyte ratio and neutrophil to

lymphocyte ratio as risk factors for venous thrombosis. Clin Appl

Thromb Hemost. 24:808–814. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Robalo Nunes A and Tátá M: The impact of

anaemia and iron deficiency in chronic obstructive pulmonary

disease: A clinical overview. Rev Port Pneumol (2006). 23:146–155.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Lederer AK, Maul-Pavicic A, Hannibal L,

Hettich M, Steinborn C, Gründemann C, Zimmermann-Klemd AM, Müller

A, Sehnert B, Salzer U, et al: Vegan diet reduces neutrophils,

monocytes and platelets related to branched-chain amino acids-A

randomized, controlled trial. Clin Nutr. 39:3241–3250.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|