Introduction

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) remains a serious

public health concern that ranks first among causes of

trauma-associated mortality and disability (1). It is estimated that ~69 million

individuals suffer TBI each year worldwide (2). The unfavorable mortality, disability

and the widespread prevalence of TBI brings a heavy economic burden

to society and to patients families (1). The severity of intracranial injury

and neurological complications increase the risk of an unfavorable

outcome after TBI. While non-neurological complications also

commonly occur after TBI and have been confirmed to be associated

with the adverse outcome of patients with TBI (3-5).

Occurring in 7.6-23% of patients with TBI, acute kidney injury

(AKI) is a common type of non-neurological organ dysfunction, which

has been verified to be correlated with increased mortality in

patients with TBI (6-11).

Therefore, evaluating renal function, predicting the possible

occurrence of AKI and sequentially adjusting treatment strategies

in early stage after initial brain injury is beneficial for

physicians to reduce the risk of AKI development and improve

prognosis of patients with TBI.

Encoded by SerpinC1, antithrombin III (ATIII) is a

serine protease inhibitor that plays an anticoagulant role in the

coagulation cascade (12). In

addition to the pivotal role involved in anticoagulation, ATIII has

been revealed to have anti-inflammation properties in previous

studies (13-16).

Previously, several studies explored the beneficial effects of

ATIII on renal protection and found that renal ischemia-reperfusion

injury in a rat model can be alleviated by ATIII through

coagulation-independent anti-inflammation effects (17-19).

In addition, the association between decreased ATIII level and the

occurrence of AKI has been confirmed in several clinical settings

including acute severe pancreatitis, sepsis and in patients

undergoing cardiac surgery (17,20,21).

However, to the best of our knowledge, the relationship between

ATIII level and the development of AKI in patients with TBI has not

been explored. Thus, the present study aimed to test the hypothesis

that ATIII level is associated with the occurrence of AKI after

TBI.

Materials and methods

Study population

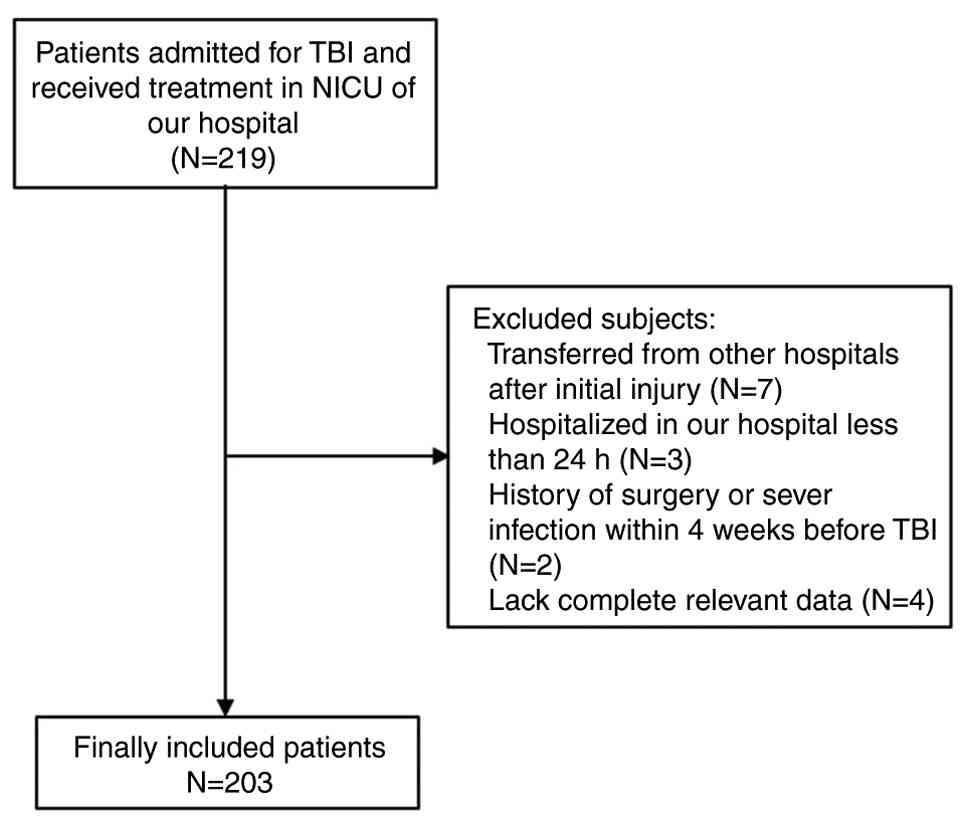

The present retrospective observational study was

performed in West China Hospital (Chengdu, China). Patients

admitted to West China Hospital for TBI and who then received

treatments in the neuro intensive care unit (NICU) between January

2015 and June 2019 were eligible for the present study. Patients

with low consciousness, unstable hemodynamics and intracranial

hypertension who required intensive monitoring and organ function

support were transferred from the emergency department to the NICU

within 24 h after admission. Therefore, the included patients were

mainly diagnosed with moderate to severe TBI. The present study

confirmed the diagnoses of TBI according to radiological signs of

computed tomography (CT) during hospitalization. There were four

exclusion criteria: i) Transferred from other hospitals after

initial injury; ii) hospitalized in West China Hospital for <24

h; iii) history of surgery or severe infection within 4 weeks

before TBI; and iv) lack of complete relevant data. The screening

diagram was shown as seen in Fig.

1. After screening, 203 patients with the median age of 44 and

male ratio of 80.3% were finally included in the present study.

This study was approved by the ethics committee of West China

Hospital and conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed consent form of each patient was routinely signed by

themselves or their authorized legal representatives.

Data collection

All clinical and laboratory variables were

retrospectively reviewed from the records of the electronic medical

record system. The present study included demographic

characteristics such as age and sex, injury mechanisms and vital

signs on admission including systolic blood pressure, diastolic

blood pressure, heart rate, body temperature and respiratory rate.

Occurrence of anisocoria, injury severity score (ISS) and Glasgow

Coma Scale (GCS) on admission were also recorded (22). Variables of laboratory test

including serum ATIII level were obtained by analyzing the first

blood samples collected when patients were admitted to the

emergency department of West China Hospital. Acute liver injury was

confirmed based on the liver function score of sequential organ

failure assessment score, namely total bilirubin ≥20.5 µmol/l

(23). Marshall CT score and

specified injury types, including subarachnoid hemorrhage and

intraventricular hemorrhage, were collected based on the findings

of the CT scans (24). AKI was

diagnosed according to the KDIGO criteria (25). As the aim of the present study was

to predict the development of AKI during hospitalizations, any AKIs

that occurred on the first day after admission were excluded and

only AKIs that occurred after the second day after admission were

selected as primary outcome (since the treatment of first day is

mainly focused on emergency treatment and maintaining vital signs).

In addition, AKI on the first day is difficult to identify because

the AKI is diagnosed based on fluctuation of SCr and the level of

SCr may not be measured more than one time within the first day

after admission. Records of blood product transfusion, drugs

reducing intracranial pressure, nephrotoxic antibiotics and surgery

types were included in the present study. The indications for fresh

frozen plasma (FFP) in West China Hospital for trauma patients were

shown as follows: i) Acute massive hemorrhage (blood loss ≥70 ml/kg

within 24 h); and ii) prothrombin time (PT) or activated partial

thromboplastin time (APTT) prolongation >1.5 times. Records of

aforementioned medicine and operation for AKI group were collected

until AKI developed while those for non-AKI group were collected

during the whole hospitalization.

Statistical analysis

The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to verify the

normality of the included variables. Normally distributed variables

were presented as mean ± standard deviation while non-normally

distributed variables were presented as median (interquartile

range). And categorical variables were presented as counts

(percentage). The present study conducted unpaired Student's t-test

to analyze the difference between two groups of normally

distributed variables. And the difference between two groups of

non-normally distributed variables were testified by utilizing

Mann-Whitney U test. χ2 test or Fisher's exact test were

performed to verify the difference between two groups of

categorical variables. To discover potential risk factors for AKI

in included patients with TBI, univariate logistic regression

analysis was first conducted to present the relationship without

adjusting confounding effects. Odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence

intervals (CI) of each risk factors were calculated and shown.

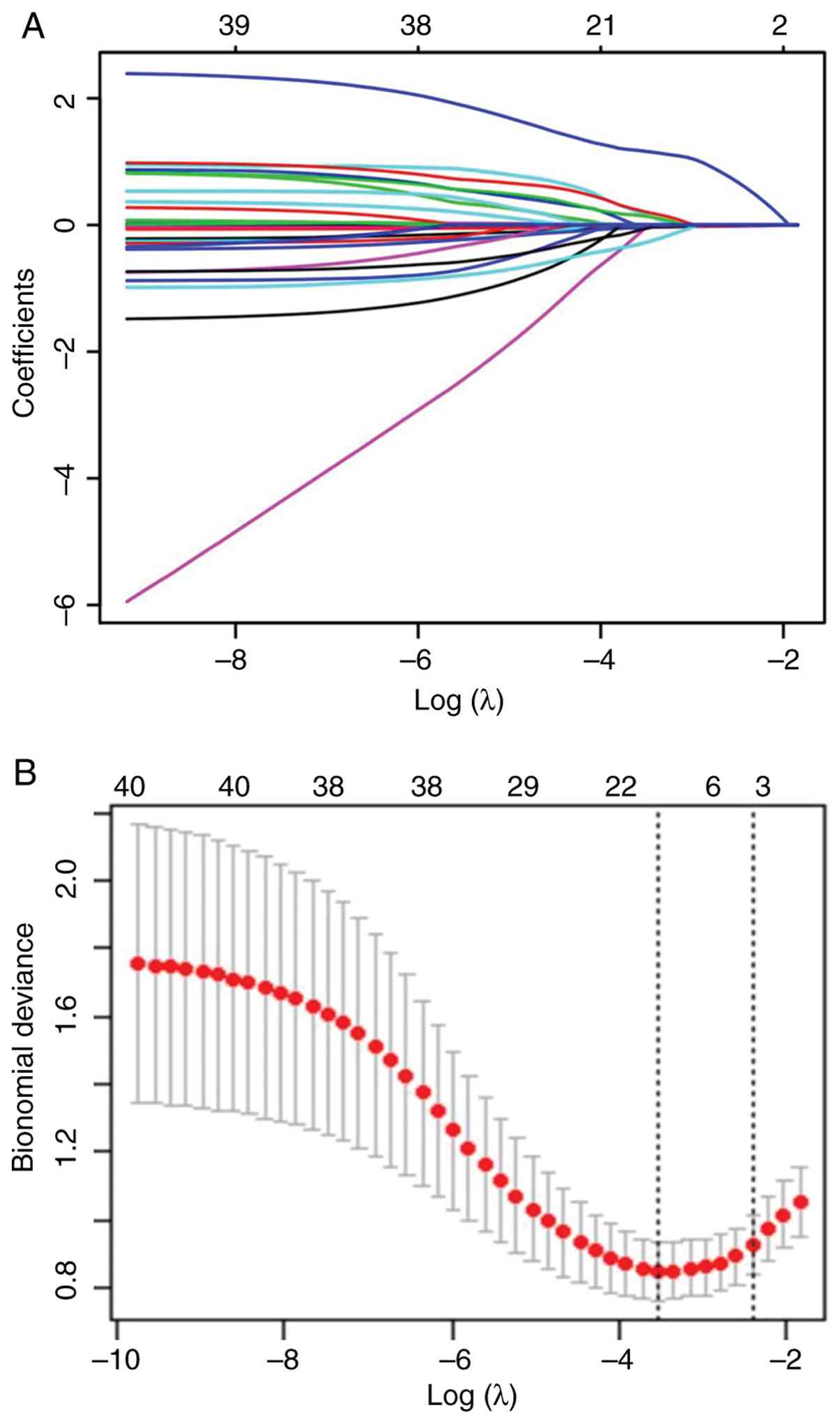

Because of the numerous included variables and limited number of

outcomes, the least absolute shrinkage and selection operator

(LASSO) regression, which could minimize the collinearity of

selected risk factors and avoid overfitting of these factors, was

performed to identify predictors with non-zero coefficients.

Identifying the strongest predictors from plenty of potential risk

factors for targeted outcome with relatively small quantity is the

advantage of LASSO regression. Predictors with non-zero

coefficients were included in multivariate logistic regression

analysis to construct models for predicting AKI in included

patients with TBI. Finally, receiver operating characteristic (ROC)

curve was drawn and area under the ROC curve (AUC) value was

calculated to evaluate the predictive value of single ATIII, SCr

and constructed models. The corresponding sensitivity and

specificity of ATIII and constructed model were shown. Z test was

conducted to verify the difference of AUC value between single

ATIII and constructed models. Two-tailed P<0.05 was considered

to indicate a statistically significant difference. SPSS 22.0

Windows software (IBM Corp.) and R (version 3.6.1; R Foundation)

were used to carry out all statistical analyses.

Results

Baseline characteristics of included

patients with TBI

A total of 203 patients with TBI were finally

included in the present study, with 43 developing AKI 24 h after

admission (Table I). Among 43

confirmed patients with AKI, 30 patients were confirmed as stage 1,

7 patients confirmed as stage 2 and 6 patients confirmed as stage 3

according to KDIGO criteria. No patient received renal replacement

therapy among the included patients with TBI. The age and sex ratio

did not differ between the non-AKI group and AKI group (age, 43 vs.

47, P=0.057; sex, 78.8 vs. 86.0%, P=0.270). Among injury

mechanisms, traffic accident and high falling ranked the first and

the second with rate of 60.1 and 23.2%. Vital signs on admission

did not show any significant differences between the non-AKI group

and AKI group. The AKI group had significantly lower GCS (5 vs. 6;

P=0.002) and higher ISS (25 vs. 24; P=0.009) compared with the

non-AKI group. Records of laboratory test presented that AKI group

had higher blood glucose (12.68 vs. 8.94; P<0.001), prothrombin

time (14.6 vs. 13.4; P=0.002), blood urea nitrogen (BUN; 7.70 vs.

5.75; P=0.001) and SCr (98 vs. 68; P<0.001) compared with the

non-AKI group. While the platelet (100 vs. 122; P=0.031), albumin

(28.95 vs. 32.15; P=0.001), hemoglobin (79 vs. 92; P<0.001),

fibrinogen (1.94 vs. 2.81; P=0.006) and ATIII (62.1 vs. 81.0;

P<0.001) levels were significantly lower in the AKI group

compared with the non-AKI group. Radiological findings demonstrated

that Marshall CT score and incidence of subarachnoid hemorrhage and

intraventricular hemorrhage were not significantly different

between those two groups. As for blood product transfusion, AKI

group were more likely to receive FFP (55.8 vs. 17.5%; P<0.001),

hydroxyethyl starch (46.5 vs. 30.0%; P=0.045) and red blood cell

(55.8 vs. 32.5%; P=0.006). Considering the drugs reducing

intracranial pressure (ICP), hypertonic saline was less likely to

be used in the AKI group (18.6 vs. 43.8%; P=0.02). In addition,

vancomycin was also less likely to be used in the AKI group (11.6

vs. 28.1%; P=0.018). The AKI group had a significantly higher

in-hospital mortality rate compared with the non-AKI group (65.1

vs. 30.0%; P<0.001). Furthermore, the length of ICU stay (11 vs.

16; P=0.177) and length of hospital stay (13 vs. 26; P=0.001) were

both shorter in the AKI group due to the notable early mortalities

among the AKI group.

| Table IBaseline characteristics of non-AKI

group and AKI group in included patients with TBI. |

Table I

Baseline characteristics of non-AKI

group and AKI group in included patients with TBI.

| Variables | Overall patients

(n=203) | Non-AKI group

(n=160; 80.3%) | AKI group (n=43;

19.7%) | P-value |

|---|

| Age, years | 44 (28-58) | 43 (27-55) | 47 (33-64) | 0.057 |

| Male sex, n

(%) | 163 (80.3%) | 126 (78.8%) | 37 (86.0%) | 0.270 |

| Injury

mechanism | | | | 0.152 |

|

Traffic

accident | 122 (60.1%) | 100 (62.5%) | 22 (51.2%) | |

|

High

fall | 47 (23.2%) | 34 (21.3%) | 13 (30.2%) | |

|

Stumble | 21 (10.3%) | 14 (8.8%) | 7 (16.3%) | |

|

Others | 13 (6.4%) | 12 (7.5%) | 1 (2.3%) | |

| Vital signs on

admission | | | | |

|

Systolic

blood pressure, mmHg | 123 (108-138) | 123 (110-138) | 117 (101-145) | 0.324 |

|

Diastolic

blood pressure, mmHg | 73.5±16.3 | 74.2±14.5 | 71.1±21.6 | 0.384 |

|

Heart rate,

min-1 | 98 (80-120) | 98 (80-120) | 100 (80-125) | 0.901 |

|

Body

temperature,˚C | 36.8

(36.5-37.2) | 36.8

(36.5-37.3) | 36.8

(36.5-37.0) | 0.520 |

|

Respiratory

rate, min-1 | 20 (17-24) | 20 (17-24) | 20 (17-22) | 0.588 |

| Anisocoria | 76 (37.4%) | 60 (37.5%) | 16 (37.2%) | 0.972 |

| GCS | 6 (5-7) | 6 (5-8) | 5 (3-7) | 0.002 |

| ISS | 25 (16-25) | 24 (16-25) | 25 (16-29) | 0.009 |

| Laboratory

tests | | | | |

|

Glucose,

mmol/l | 9.70

(7.23-13.31) | 8.94

(6.77-12.61) | 12.68

(8.83-15.45) | <0.001 |

|

White blood

cell, 109/l | 15.45

(11.27-20.43) | 15.38

(11.33-20.39) | 15.65

(10.05-20.73) | 0.974 |

|

Neutrophil,

109/l | 11.75

(8.70-15.81) | 11.81

(9.00-15.76) | 11.63

(7.34-16.9) | 0.713 |

|

Lymphocyte,

109/l | 0.80

(0.53-1.12) | 0.79

(0.53-1.18) | 0.80

(0.50-1.05) | 0.358 |

|

Platelet,

109/l | 113 (80-169) | 122 (86-178) | 100 (58-161) | 0.031 |

|

Albumin,

g/l | 31.47±5.63 | 32.15±5.22 | 28.95±6.39 | 0.001 |

|

Hemoglobin,

g/l | 88 (77-106) | 92 (79-109) | 79 (72-88) | <0.001 |

|

Fibrinogen,

mg/l | 2.53

(1.63-4.07) | 2.81

(1.71-4.49) | 1.94

(1.15-3.31) | 0.006 |

|

D-dimmer,

mg/l | 15.24

(7.37-34.99) | 14.76

(6.10-33.96) | 17.27

(10.38-38.00) | 0.124 |

|

Prothrombin

time, sec | 13.6

(12.2-15.4) | 13.4

(12.0-15.0) | 14.6

(13.3-18.2) | 0.002 |

|

APTT,

sec | 27.4

(26.6-28.9) | 27.2

(26.5-27.9) | 31.3

(28.8-33.2) | |

|

ATIII,

% | 77.0±19.9 | 81.0±18.4 | 62.1±18.3 | <0.001 |

|

Blood urea

nitrogen, mmol/l | 5.93

(4.70-8.51) | 5.75

(4.46-7.82) | 7.70

(5.41-11.44) | 0.001 |

|

Serum

creatinine, µmol/l | 71 (55-98) | 68 (52-86) | 98 (76-131) | <0.001 |

| Acute liver

dysfunction | 58 (28.6%) | 47 (29.4%) | 11 (25.6%) | 0.622 |

| Radiological

findings | | | | |

|

Marshall CT

score | 4 (3-6) | 4 (3-6) | 6 (3-6) | 0.280 |

|

Subarachnoid

hemorrhage, n (%) | 87 (42.9%) | 68 (42.5%) | 19 (44.2%) | 0.843 |

|

Intraventricular

hemorrhage, n (%) | 8 (3.9%) | 8 (5.0%) | 0 | 0.207 |

| Blood product

transfusion, n (%) | | | | |

|

Fresh frozen

plasma | 52 (25.6%) | 28 (17.5%) | 24 (55.8%) | <0.001 |

|

Fibrinogen

transfusion | 26 (12.8%) | 18 (11.3%) | 8 (18.6%) | 0.218 |

|

Hydroxyethyl

starch | 68 (33.5%) | 48 (30.0%) | 20 (46.5%) | 0.045 |

|

Red blood

cell transfusion | 76 (37.4%) | 52 (32.5%) | 24 (55.8%) | 0.006 |

| Drugs reducing ICP,

n (%) | | | | |

|

Mannitol | 158 (77.8%) | 124 (77.5%) | 34 (79.1%) | 0.825 |

|

Fructose

glycerol | 21 (10.3%) | 15 (9.4%) | 6 (14.0%) | 0.401 |

|

Hypertonic

saline | 78 (38.4%) | 70 (43.8%) | 8 (18.6%) | 0.002 |

|

Furosemide | 70 (34.5%) | 53 (33.1%) | 17 (39.5%) | 0.436 |

| Nephrotoxic

antibiotics, n (%) | | | | |

|

Vancomycin | 50 (24.6%) | 45 (28.1%) | 5 (11.6%) | 0.018 |

|

Meropenem | 27 (13.3%) | 22 (13.8%) | 5 (11.6%) | 0.712 |

| Surgical

operations | | | | |

|

Decompressive

craniectomy, n (%) | 74 (36.5%) | 53 (33.1%) | 21 (48.8%) | 0.061 |

|

Hematoma

evacuation, n (%) | 87 (42.9%) | 66 (41.3%) | 21 (48.8%) | 0.374 |

| Length of ICU stay,

days | 15 (5-27) | 16 (6-27) | 11 (2-27) | 0.177 |

| Length of hospital

stay, days | 24 (10-41) | 26 (13-42) | 13 (3-35) | 0.001 |

| In-hospital

mortality, n (%) | 76 (37.4%) | 48 (30.0%) | 28 (65.1%) | <0.001 |

Univariate logistic regression

analysis of risk factors for AKI in patients with TBI

Univariate logistic regression analysis showed that

ISS (P=0.005), glucose (P=0.001), BUN (P=0.035), prothrombin time

(P=0.001), SCr (P<0.001) and transfusion of FFP (P<0.001),

hydroxyethyl starch (P=0.044) and RBC (P=0.006) were potential risk

factors for AKI after TBI (Table

II). Whereas GCS (P=0.004), platelet (P=0.035), albumin

(P=0.001), hemoglobin (P=0.002), fibrinogen (P=0.007), ATIII

(P<0.001) and usage of hypertonic saline (P=0.004) and

vancomycin (P=0.032) were negatively associated with occurrence of

AKI after TBI.

| Table IIUnivariate logistic regression

analysis of risk factors for acute kidney injury in included

patients with traumatic brain injury. |

Table II

Univariate logistic regression

analysis of risk factors for acute kidney injury in included

patients with traumatic brain injury.

| Variables | Odds ratio | 95% Confidence

interval | P-value |

|---|

| Age, years | 1.019 | 1.001-1.038 | 0.041 |

| Male, n (%) | 1.664 | 0.649-4.269 | 0.289 |

|

Systolic

blood pressure, mmHg | 0.995 | 0.982-1.009 | 0.514 |

|

Diastolic

blood pressure, mmHg | 0.989 | 0.969-1.009 | 0.274 |

|

Heart rate,

min-1 | 1.002 | 0.989-1.014 | 0.790 |

|

Body

temperature,˚C | 0.947 | 0.651-1.377 | 0.774 |

|

Respiratory

rate, min-1 | 1.000 | 0.942-1.063 | 0.991 |

| Anisocoria | 0.988 | 0.492-1.982 | 0.972 |

| GCS | 0.798 | 0.684-0.932 | 0.004 |

| ISS | 1.053 | 1.016-1.091 | 0.005 |

|

Glucose,

mmol/l | 1.130 | 1.050-1.215 | 0.001 |

|

White blood

cell, 109/l | 1.011 | 0.964-1.060 | 0.655 |

|

Neutrophil,

109/l | 0.995 | 0.968-1.023 | 0.716 |

|

Lymphocyte,

109/l | 0.642 | 0.328-1.255 | 0.195 |

|

Platelet,

109/l | 0.994 | 0.989-1.000 | 0.035 |

|

Albumin,

g/l | 0.896 | 0.838-0.959 | 0.001 |

|

Hemoglobin,

g/l | 0.971 | 0.953-0.989 | 0.002 |

|

Fibrinogen,

mg/l | 0.738 | 0.592-0.921 | 0.007 |

|

D-dimmer,

mg/l | 1.016 | 0.991-1.042 | 0.218 |

|

Prothrombin

time, sec | 1.149 | 1.057-1.250 | 0.001 |

|

APTT,

sec | 1.600 | 1.357-1.886 | <0.001 |

|

ATIII,

% | 0.943 | 0.922-0.965 | <0.001 |

|

Blood urea

nitrogen, mmol/l | 1.056 | 1.004-1.112 | 0.035 |

|

Serum

creatinine, µmol/l | 1.011 | 1.005-1.017 | <0.001 |

| Acute liver

dysfunction, n (%) | 0.826 | 0.385-1.776 | 0.625 |

| Marshall CT

score | 1.139 | 0.923-1.405 | 0.225 |

| Subarachnoid

hemorrhage, n (%) | 1.071 | 0.543-2.111 | 0.843 |

| Intraventricular

hemorrhage, n (%) | 0 | 0 | 0.999 |

| Fresh frozen

plasma, n (%) | 5.955 | 2.878-12.32 | <0.001 |

| Fibrinogen

transfusion, n (%) | 1.803 | 0.725-4.485 | 0.205 |

| Hydroxyethyl

starch, n (%) | 2.029 | 1.020-4.037 | 0.044 |

| Red blood cell

transfusion, n (%) | 2.623 | 1.320-5.214 | 0.006 |

| Mannitol, n

(%) | 1.097 | 0.482-2.498 | 0.826 |

| Fructose glycerol,

n (%) | 1.568 | 0.569-4.318 | 0.385 |

| Hypertonic saline,

n (%) | 0.294 | 0.128-0.673 | 0.004 |

| Furosemide, n

(%) | 1.320 | 0.659-2.643 | 0.433 |

| Vancomycin, n

(%) | 0.336 | 0.124-0.909 | 0.032 |

| Meropenem, n

(%) | 0.825 | 0.293-2.324 | 0.716 |

| Decompressive

craniectomy, n (%) | 1.927 | 0.974-3.814 | 0.060 |

| Hematoma

evacuation, n (%) | 1.360 | 0.692-2.672 | 0.373 |

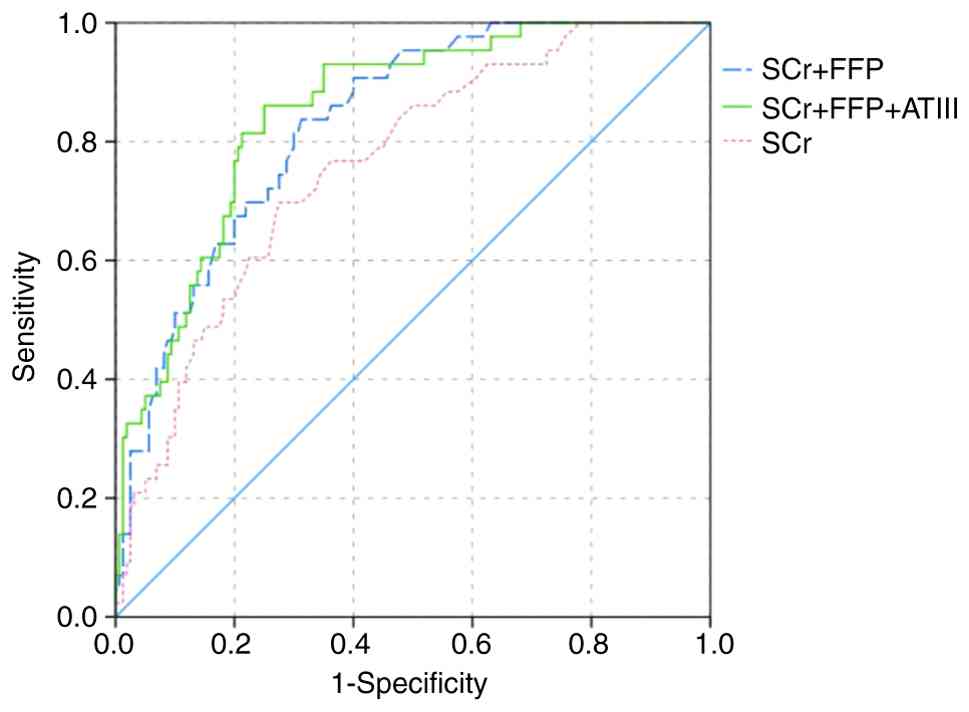

Value of ATIII and constructed

predictive models for predicting AKI after TBI

Utilizing LASSO regression, SCr, ATIII and

transfusion of FFP were finally recognized as the most potent

predictors of AKI in included patients with TBI (Table III; Fig. 2A and B). To enhance predictive accuracy,

multivariate logistic regression was performed to construct

predictive models incorporating these three factors. The AUC value

of single ATIII and SCr was 0.759 and 0.760, respectively (Table IV; Fig. 3). And the AUC value of

three-factors predictive model was 0.850. After removing ATIII,

two-factors model composed of SCr and transfusion of FFP had lower

AUC, but without statistical significance (0.831 vs. 0.850;

Z=0.4404; P>0.05). The two-factors model had a higher AUC

compared with single ATIII (0.831 vs. 0.759; Z=1.3582; P>0.05)

without statistical significance while the three-factors model had

significantly higher AUC compared with single ATIII (0.850 vs.

0.759; Z=1.7356; P<0.05). However, the sensitivity of single

ATIII was 0.869, which was higher compared with sensitivity of SCr

and constructed models. And adding ATIII could improve the

sensitivity of constructed model, which was beneficial for

physicians to evaluate risk of developing AKI in early stage.

| Figure 3Receiver operating characteristic

curve of single ATIII and constructed predictive models for

predicting AKI in included TBI patients. The AUC value of ATIII,

serum creatinine, two-factors predictive model and three-factors

predictive model was 0.759 (0.674-0.844), 0.760 (0.684-0.836),

0.831 (0.770-0.891) and 0.850 (0.792-0.909), respectively. ATIII,

antithrombin III; AKI, acute kidney injury; TBI, traumatic brain

injury; AUC, area under the receiver operating characteristic

curve; Scr, serum creatinine; FFP, fresh frozen plasma. |

| Table IIILASSO regression for selecting the

strongest predictors for acute kidney injury in included patients

with traumatic brain injury. |

Table III

LASSO regression for selecting the

strongest predictors for acute kidney injury in included patients

with traumatic brain injury.

| Variables | LASSO

coefficient | Regression

coefficient (β) |

|---|

| Serum

creatinine | 0.002 | -0.244 |

| ATIII | -0.017 | 0.224 |

| Transfusion of

FFP | 0.586 | 0.309 |

| Table IVPredictive value of ATIII and

constructed models for predicting acute kidney injury after

traumatic brain injury. |

Table IV

Predictive value of ATIII and

constructed models for predicting acute kidney injury after

traumatic brain injury.

| Variable | AUC | 95% CI | SE | P-value | Sensitivity | Specificity | Best cut-off |

|---|

| SCr | 0.760 | 0.684-0.836 | 0.039 | <0.001 | 0.698 | 0.725 | 82.500 |

| ATIII | 0.759 | 0.674-0.844 | 0.043 | <0.001 | 0.869 | 0.581 | 60.650 |

| SCr + FFP | 0.831 | 0.770-0.891 | 0.031 | <0.001 | 0.837 | 0.687 | 0.127 |

| SCr + FFP +

ATIII | 0.850 | 0.792-0.909 | 0.030 | <0.001 | 0.860 | 0.750 | 0.170 |

Discussion

The present study found that ATIII level, SCr and

transfusion of FFP were independently associated with the

development of AKI after TBI. The logistic regression model

constructed using these three factors was effective in predicting

the development of AKI in early stages after TBI. Compared with the

non-AKI group, AKI group had lower level of ATIII on admission.

Based on findings of previous studies, the present study could

conclude that a lower level of ATIII on admission was detrimental

to maintenance of normal renal function and consequently promoted

the development of AKI in patients with TBI.

The results of the present study showed that ATIII

decreased after TBI and the decrease of ATIII was greater in the

AKI group than the non-AKI group. It was demonstrated that the

prevalence of coagulopathy ranged from 12.5 to 45.7% in patients

with TBI (26-29).

Through initiating the extrinsic coagulation pathway, the tissue

factor released from local injured brain tissue can promote the

development of disseminated intravascular coagulation, which

manifests as early hypercoagulation and subsequent fibrinolysis

(30-33).

As a crucial component of natural anticoagulation, ATIII can

neutralize increased production of factor Xa and coagulation

enzymes, including thrombin (factor IIa) and plasmin (34,35).

The reactive center of ATIII is cleaved by thrombin and then

irreversibly combined with thrombin to form an enzyme-inhibitor

complex which is quickly cleared from the circulation (35). In addition to increased

consumption, reduced synthesis due to the impaired liver function

may also lead to the decreased ATIII level. The impaired liver

function in patients with TBI can be attributable to the commonly

existing systemic inflammatory response with elevated inflammatory

cytokines level that promoted the hepato-cellular injury (36,37).

The renal-protective role of ATIII has been

investigated through inhibiting local renal inflammation, oxidative

stress activity and cell apoptosis (20). Both renal local inflammation and

systemic inflammation response take part in the progress of AKI

(38-41).

ATIII can exert anti-inflammatory action in a renal

ischemia-reperfusion injury model by inhibiting the release of

proinflammatory cytokines from endothelial cells and subsequent

chemokine mediated leukocytes infiltration, promoting the

production of prostacyclin (PGI2) (42,43).

Previous studies showed that supplement of ATIII can reduce serum

TNF-α concentration and consequently inhibit the expression levels

of monocyte chemotactic protein 1 and intercellular cell adhesion

molecule 1 in renal tissues (14,20).

In addition, ATIII can exert anti-inflammatory effects by inducing

the synthesis of PGI2, which not only suppresses the

proinflammatory effects of platelets, neutrophils and cytokines,

but also restores renal cortical blood flow as an effective

vasodilator (14,16,17,44,45).

TBI can initiate the systemic inflammatory response syndrome and

the release of various cytokines into the circulation, which is

associated with non-neurological organ failure, such as AKI

(46-48).

Therefore, the present study considered that ATIII can also

alleviate the progress of AKI in patients with TBI by mitigating

the detrimental effects of systemic inflammation and renal local

inflammation.

Imbalanced oxidative stress has been confirmed as a

critical pathogenetic factor which plays an important role in the

development and progress of AKI (49-51).

Therapeutic strategies targeting oxidative stress have attracted

considerable attention (49).

Previous studies have demonstrated that ATIII can alleviate the

aggressive status of oxidative stress in renal tissue of rat models

with AKI (14,17,20).

The mitigation of increased malondialdehyde and decreased

superoxide dismutase in injured renal tissue has been observed in

rats that received a supplement of ATIII (52). The apoptosis of renal tubular

epithelial cells is another key mechanism of AKI (53-55).

It has been verified that ATIII are capable of reducing caspase-3

expression and increasing bcl-2 expression in rat models with AKI

(20). Thus, the present study

hypothesized the association between low ATIII level and AKI

following TBI may also be mediated by oxidative stress and

apoptosis.

Another possible explanation for the role of ATIII

on alleviating renal injury may be the anticoagulative action.

Previous studies hypothesized that thrombin generation can cause

impairment to renal microcirculation and damage to tubular cells

(53-55).

In summary, the present study demonstrated that low ATIII level is

independently related with the occurrence of AKI after TBI through

the aforementioned mechanisms. Maintaining the appropriate ATIII

level may be beneficial to prevent or lessen AKI after TBI.

However, the specific and precise maintaining level of ATIII should

be explored further. In addition, future studies involving animal

models is worthwhile to design to confirm the potential

aforementioned mechanism. In addition to ATIII, SCr and transfusion

of FFP were independent risk factors of AKI after TBI in the

present study. The clinical significance of SCr as an indication of

glomerular filtration function has been acknowledged. The AUC value

of only ATIII and SCr for predicting AKI in the present study was

0.759 and 0.760, respectively. Although the AUC value was

comparable between ATIII and SCr, the sensitivity of ATIII was

higher compared with SCr (0.869 vs. 0.698), which was beneficial

for physicians to quickly identify patients with TBI and high risk

of AKI. The SCr level may be influenced by blood loss, fluid

dilution, muscle mass, nutritional status, age and sex and

therefore may not reflect the acute change of estimated glomerular

filtration rate sensitively. Additionally, the accuracy of BUN

reflecting the renal function may also be disturbed by multiple

factors including gastrointestinal bleeding, dehydration,

inflammation and protein intake (56). The transfusion of FFP was also

confirmed to be a risk factor for AKI in various types of patients,

including those receiving liver transplantation (57-60).

It has been demonstrated that FFP transfusion can trigger and even

exacerbate an inflammatory, immunological and allergic reaction,

which might aggravate the renal injury (61). The results of the present study

showed that combining these factors together was more effective in

predicting AKI compared with ATIII alone in patients with TBI.

The significant differences in blood glucose,

prothrombin time, platelets, albumin, hemoglobin and fibrinogen do

exist but are not present in the predictive model. This

contradiction is due to the present study using the LASSO

regression to develop the predictive model. The LASSO regression

performs well in identifying predictors among a dataset that has

numerous variables and a limited number of outcomes, and it can

minimize the collinearity of selected risk factors and avoid

overfitting of these factors. The clinical outcome of the present

study that 43 TBI patients were identified with the AKI. Therefore,

the present study did not use a traditional multivariate logistic

regression model to explore the risk factors of AKI, but used LASSO

to discover the strongest predictors of AKI from numerous potential

risk factors. The blood glucose, prothrombin time, platelet,

albumin, hemoglobin and fibrinogen levels showed significant

differences; however, they did not show stronger predictive value

compared with the three factors the present study revealed,

including SCr, antithrombin III and FFP.

There were several limitations in the present study.

Firstly, the present study was conducted in a single medical center

and mainly included moderate to severe patients with TBI treated in

NICU. Patients with history of surgery or severe infection within 4

weeks before TBI were also excluded. Therefore, selection bias may

not be avoided. The findings of the present study should be further

verified in future studies with larger sample sizes and more

generalized patients with TBI. Secondly, the detailed dosage and

infusion rate of drugs reducing ICP and blood products were not

collected in the present study. The real confounding effects of

these drugs may be weakened. Thirdly, underlying diseases, such as

cardiovascular diseases, renal diseases and malignant tumor, were

not collected as variables due to the low prevalence of them in the

included patients. Finally, only levels of ATIII on admission but

not subsequent fluctuation of ATIII were recorded; therefore, the

present study could not evaluate the influence of ATIII changes on

AKI development. Therefore, the conclusion drawn from the present

study should be verified in future studies.

In conclusion, ATIII is an easily obtained indicator

of AKI after TBI. Decreased ATIII is associated with higher

possibilities of AKI. Evaluating and avoiding decreased ATIII level

may be helpful for clinicians to avoid possible occurrence of AKI

in patients with TBI.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: This research was supported by the 1·3·5 project for

disciplines of excellence - Clinical Research Incubation Project,

West China Hospital, Sichuan University (grant no. 19HXFH012).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current

study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable

request.

Authors' contributions

RRW and JGX conceived and designed the study,

performed the statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript for

intellectual content. RRW and MH acquired, analyzed and interpreted

the data. RRW and MH confirm the authenticity of all the raw data.

JGX reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors read and

approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

This study was approved by the ethics committee of

West China hospital, Sichuan University (approval number2021-1598)

and has been performed in accordance with the ethical standards

laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent forms of

each patients were legally obtained from themselves or their

authorized families.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Rubiano AM, Carney N, Chesnut R and Puyana

JC: Global neurotrauma research challenges and opportunities.

Nature. 527:S193–S197. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Dewan MC, Rattani A, Gupta S, Baticulon

RE, Hung YC, Punchak M, Agrawal A, Adeleye AO, Shrime MG, Rubiano

AM, et al: Estimating the global incidence of traumatic brain

injury. J Neurosurg. 130:1080–1097. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Zygun DA, Kortbeek JB, Fick GH, Laupland

KB and Doig CJ: Non-neurologic organ dysfunction in severe

traumatic brain injury. Crit Care Med. 33:654–660. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Zygun D: Non-neurological organ

dysfunction in neurocritical care: Impact on outcome and

etiological considerations. Curr Opin Crit Care. 11:139–143.

2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Hanna K, Hamidi M, Vartanyan P, Henry M,

Castanon L, Tang A, Zeeshan M, Kulvatunyou N and Joseph B:

Non-neurologic organ dysfunction plays a major role in predicting

outcomes in pediatric traumatic brain injury. J Pediatr Surg.

55:1590–1595. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Corral L, Javierre CF, Ventura JL, Marcos

P, Herrero JI and Manez R: Impact of non-neurological complications

in severe traumatic brain injury outcome. Crit Care.

16(R44)2012.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Moore EM, Bellomo R, Nichol A, Harley N,

Macisaac C and Cooper DJ: The incidence of acute kidney injury in

patients with traumatic brain injury. Ren Fail. 32:1060–1065.

2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Li N, Zhao WG and Zhang WF: Acute kidney

injury in patients with severe traumatic brain injury:

Implementation of the acute kidney injury network stage system.

Neurocrit Care. 14:377–381. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Skrifvars MB, Moore E, Martensson J,

Bailey M, French C, Presneill J, Nichol A, Little L, Duranteau J,

Huet O, et al: Erythropoietin in traumatic brain injury associated

acute kidney injury: A randomized controlled trial. Acta

Anaesthesiol Scand. 63:200–207. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Barea-Mendoza JA, Chico-Fernández M,

Quintana-Díaz M, Serviá-Goixart L, Fernández-Cuervo A,

Bringas-Bollada M, Ballesteros-Sanz MÁ, García-Sáez Í,

Pérez-Bárcena J and Llompart-Pou JA: Neurointensive Care and Trauma

Working Group of the Spanish Society of Intensive Care Medicine

(SEMICYUC). Traumatic brain injury and acute kidney injury-outcomes

and associated risk factors. J Clin Med. 11(7216)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Maragkos GA, Cho LD, Legome E, Wedderburn

R and Margetis K: Prognostic factors for stage 3 acute kidney

injury in isolated serious traumatic brain injury. World Neurosurg.

161:e710–e722. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Caspers M, Pavlova A, Driesen J, Harbrecht

U, Klamroth R, Kadar J, Fischer R, Kemkes-Matthes B and Oldenburg

J: Deficiencies of antithrombin, protein C and protein S-practical

experience in genetic analysis of a large patient cohort. Thromb

Haemost. 108:247–257. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Levy JH, Sniecinski RM, Welsby IJ and Levi

M: Antithrombin: Anti-inflammatory properties and clinical

applications. Thromb Haemost. 115:712–728. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Lu Z, Cheng D, Yin J, Wu R, Zhang G, Zhao

Q, Wang N, Wang F and Liang M: Antithrombin III Protects Against

Contrast-Induced Nephropathy. EBioMedicine. 17:101–107.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Opal SM: Interactions between coagulation

and inflammation. Scand J Infect Dis. 35:545–554. 2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Roemisch J, Gray E, Hoffmann JN and

Wiedermann CJ: Antithrombin: A new look at the actions of a serine

protease inhibitor. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 13:657–670.

2002.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Wang F, Zhang G, Lu Z, Geurts AM, Usa K,

Jacob HJ, Cowley AW, Wang N and Liang M: Antithrombin III/SerpinC1

insufficiency exacerbates renal ischemia/reperfusion injury. Kidney

Int. 88:796–803. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Ozden A, Sarioglu A, Demirkan NC, Bilgihan

A and Düzcan E: Antithrombin III reduces renal ischemia-reperfusion

injury in rats. Res Exp Med (Berl). 200:195–203. 2001.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Yin J, Wang F, Kong Y, Wu R, Zhang G, Wang

N, Wang L, Lu Z and Liang M: Antithrombin III prevents progression

of chronic kidney disease following experimental

ischaemic-reperfusion injury. J Cell Mol Med. 21:3506–3514.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Kong Y, Yin J, Cheng D, Lu Z, Wang N, Wang

F and Liang M: Antithrombin III Attenuates AKI Following Acute

Severe Pancreatitis. Shock. 49:572–579. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Xie Y, Tian R, Jin W, Xie H, Du J, Zhou Z

and Wang R: Antithrombin III expression predicts acute kidney

injury in elderly patients with sepsis. Exp Ther Med. 19:1024–1032.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Foreman BP, Caesar RR, Parks J, Madden C,

Gentilello LM, Shafi S, Carlile MC, Harper CR and Diaz-Arrastia RR:

Usefulness of the abbreviated injury score and the injury severity

score in comparison to the Glasgow Coma Scale in predicting outcome

after traumatic brain injury. J Trauma. 62:946–950. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Vincent JL, Moreno R, Takala J, Willatts

S, De Mendonça A, Bruining H, Reinhart CK, Suter PM and Thijs LG:

The SOFA (Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment) score to

describe organ dysfunction/failure. On behalf of the Working Group

on Sepsis-Related Problems of the European Society of Intensive

Care Medicine. Intensive Care Med. 22:707–710. 1996.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Marshall LF, Marshall SB, Klauber MR,

Clark MvB, Eisenberg HM, Jane JA, Luerssen TG, Marmarou A and

Foulkes MA: A new classification of head injury based on

computerized tomography. J Neurosurg. 75 (Suppl):S14–S20. 1991.

|

|

25

|

Khwaja A: KDIGO clinical practice

guidelines for acute kidney injury. Nephron Clin Pract.

120:c179–c184. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Lustenberger T, Talving P, Kobayashi L,

Inaba K, Lam L, Plurad D and Demetriades D: Time course of

coagulopathy in isolated severe traumatic brain injury. Injury.

41:924–928. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

de Oliveira Manoel AL, Neto AC, Veigas PV

and Rizoli S: Traumatic brain injury associated coagulopathy.

Neurocrit Care. 22:34–44. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Alexiou GA, Lianos G, Fotakopoulos G,

Michos E, Pachatouridis D and Voulgaris S: Admission glucose and

coagulopathy occurrence in patients with traumatic brain injury.

Brain Inj. 28:438–441. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Wafaisade A, Lefering R, Tjardes T,

Wutzler S, Simanski C, Paffrath T, Fischer P, Bouillon B and

Maegele M: Trauma Registry of DGU. Acute coagulopathy in isolated

blunt traumatic brain injury. Neurocrit Care. 12:211–219.

2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Joseph B, Aziz H, Zangbar B, Kulvatunyou

N, Pandit V, O'Keeffe T, Tang A, Wynne J, Friese RS and Rhee P:

Acquired coagulopathy of traumatic brain injury defined by routine

laboratory tests: Which laboratory values matter? J Trauma Acute

Care Surg. 76:121–125. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Kurland D, Hong C, Aarabi B, Gerzanich V

and Simard JM: Hemorrhagic progression of a contusion after

traumatic brain injury: A review. J Neurotrauma. 29:19–31.

2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Laroche M, Kutcher ME, Huang MC, Cohen MJ

and Manley GT: Coagulopathy after traumatic brain injury.

Neurosurgery. 70:1334–1345. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Stein SC and Smith DH: Coagulopathy in

traumatic brain injury. Neurocrit Care. 1:479–488. 2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Bucur SZ, Levy JH, Despotis GJ, Spiess BD

and Hillyer CD: Uses of antithrombin III concentrate in congenital

and acquired deficiency states. Transfusion. 38:481–498.

1998.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Blajchman MA: An overview of the mechanism

of action of antithrombin and its inherited deficiency states.

Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 5 (Suppl 1):S5–S11; discussion S59-S64.

1994.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Jacome T and Tatum D: Systemic

inflammatory response Syndrome (SIRS) Score independently predicts

poor outcome in isolated traumatic brain injury. Neurocrit Care.

28:110–116. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Szabo G, Romics L Jr and Frendl G: Liver

in sepsis and systemic inflammatory response syndrome. Clin Liver

Dis. 6:1045–1066, x. 2002.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Mulay SR, Holderied A, Kumar SV and Anders

HJ: Targeting inflammation in so-called acute kidney injury. Semin

Nephrol. 6:17–30. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Gomez H, Ince C, De Backer D, Pickkers P,

Payen D, Hotchkiss J and Kellum JA: A unified theory of

sepsis-induced acute kidney injury: Inflammation, microcirculatory

dysfunction, bioenergetics, and the tubular cell adaptation to

injury. Shock. 41:3–11. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Maiwall R, Chandel SS, Wani Z, Kumar S and

Sarin SK: SIRS at Admission Is a Predictor of AKI Development and

Mortality in Hospitalized Patients with Severe Alcoholic Hepatitis.

Dig Dis Sci. 61:920–929. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Toyonaga Y, Asayama K and Maehara Y:

Impact of systemic inflammatory response syndrome and surgical

Apgar score on post-operative acute kidney injury. Acta

Anaesthesiol Scand. 61:1253–1261. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Souter PJ, Thomas S, Hubbard AR, Poole S,

Römisch J and Gray E: Antithrombin inhibits

lipopolysaccharide-induced tissue factor and interleukin-6

production by mononuclear cells, human umbilical vein endothelial

cells, and whole blood. Crit Care Med. 29:134–139. 2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Ostrovsky L, Woodman RC, Payne D, Teoh D

and Kubes P: Antithrombin III prevents and rapidly reverses

leukocyte recruitment in ischemia/reperfusion. Circulation.

96:2302–2310. 1997.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Horie S, Ishii H and Kazama M:

Heparin-like glycosaminoglycan is a receptor for antithrombin

III-dependent but not for thrombin-dependent prostacyclin

production in human endothelial cells. Thromb Res. 59:895–904.

1990.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Harada N, Okajima K, Kushimoto S, Isobe H

and Tanaka K: Antithrombin reduces ischemia/reperfusion injury of

rat liver by increasing the hepatic level of prostacyclin. Blood.

93:157–164. 1999.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Shein SL, Shellington DK, Exo JL, Jackson

TC, Wisniewski SR, Jackson EK, Vagni VA, Bayır H, Clark RS, Dixon

CE, et al: Hemorrhagic shock shifts the serum cytokine profile from

pro- to anti-inflammatory after experimental traumatic brain injury

in mice. J Neurotrauma. 31:1386–1395. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Maier B, Lefering R, Lehnert M, Laurer HL,

Steudel WI, Neugebauer EA and Marzi I: Early versus late onset of

multiple organ failure is associated with differing patterns of

plasma cytokine biomarker expression and outcome after severe

trauma. Shock. 28:668–674. 2007.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Chaikittisilpa N, Krishnamoorthy V, Lele

AV, Qiu Q and Vavilala MS: Characterizing the relationship between

systemic inflammatory response syndrome and early cardiac

dysfunction in traumatic brain injury. J Neurosci Res. 96:661–670.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Tomsa AM, Alexa AL, Junie ML, Rachisan AL

and Ciumarnean L: Oxidative stress as a potential target in acute

kidney injury. PeerJ. 7(e8046)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Lee KH, Tseng WC, Yang CY and Tarng DC:

The Anti-Inflammatory, Anti-Oxidative, and anti-apoptotic benefits

of stem cells in acute ischemic kidney injury. Int J Mol Sci.

20(3529)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Gyurászová M, Kovalčíková AG, Renczés E,

Kmeťová K, Celec P, Bábíčková J and Tóthová Ľ: Oxidative stress in

animal models of acute and chronic renal failure. Dis Markers.

2019(8690805)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Erman T, Yildiz MS, Göçer AI, Zorludemir

S, Demirhindi H and Tuna M: Effects of antithrombin III on

myeloperoxidase activity, superoxide dismutase activity, and

malondialdehyde levels and histopathological findings after spinal

cord injury in the rat. Neurosurgery. 56:828–835. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Havasi A and Borkan SC: Apoptosis and

acute kidney injury. Kidney Int. 80:29–40. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Yang X, Yan X and Yang D, Zhou J, Song J

and Yang D: Rapamycin attenuates mitochondrial injury and renal

tubular cell apoptosis in experimental contrast-induced acute

kidney injury in rats. Biosci Rep. 38(BSR20180876)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Arai S, Kitada K, Yamazaki T, Takai R,

Zhang X, Tsugawa Y, Sugisawa R, Matsumoto A, Mori M, Yoshihara Y,

et al: Apoptosis inhibitor of macrophage protein enhances

intraluminal debris clearance and ameliorates acute kidney injury

in mice. Nat Med. 22:183–193. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Beier K, Eppanapally S, Bazick HS, Chang

D, Mahadevappa K, Gibbons FK and Christopher KB: Elevation of blood

urea nitrogen is predictive of long-term mortality in critically

ill patients independent of ‘normal’ creatinine. Crit Care Med.

39:305–313. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Yu JH, Kwon Y, Kim J, Yang SM, Kim WH,

Jung CW, Suh KS and Lee KH: Influence of Transfusion on the Risk of

Acute Kidney Injury: ABO-Compatible versus ABO-Incompatible Liver

Transplantation. J Clin Med. 8(1785)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

58

|

Kalisvaart M, Schlegel A, Umbro I, de Haan

JE, Polak WG, IJzermans JN, Mirza DF, Perera MTP, Isaac JR,

Ferguson J, et al: The AKI Prediction Score: A new prediction model

for acute kidney injury after liver transplantation. HPB (Oxford).

21:1707–1758. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

59

|

Kim WH, Park MH, Kim HJ, Lim HY, Shim HS,

Sohn JT, Kim CS and Lee SM: Potentially modifiable risk factors for

acute kidney injury after surgery on the thoracic aorta: A

propensity score matched case-control study. Medicine (Baltimore).

94(e273)2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

60

|

Aksu Erdost H, Ozkardesler S, Ocmen E,

Avkan-Oguz V, Akan M, Iyilikci L, Unek T, Ozbilgin M, Meseri Dalak

R and Astarcioglu I: Acute renal injury evaluation after liver

transplantation: With RIFLE Criteria. Transplant Proc.

47:1482–1487. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

61

|

Pandey S and Vyas GN: Adverse effects of

plasma transfusion. Transfusion. 52 (Suppl 1):65s–79s.

2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|