Introduction

Achalasia is a rare motility disorder of the

esophagus characterized by dysphagia, chest pain, and weight loss

(1,2). It has an annual incidence of one in

100,000 individuals and a prevalence of 10 in 100,000 individuals,

and occurs equally in male and female patients (3). Although the exact cause remains

largely unknown, a combination of genetic and environmental

factors, such as viral infection-mediated immune reactions, may

lead to ganglionitis and the loss of esophageal neurons (1,4,5).

Achalasia is defined by a combination of symptoms, endoscopic

findings, esophagography, and esophageal high-resolution manometry

(HRM) (2,6).

Although the underlying causes and variations in

esophageal motility disorders remain largely unknown, HRM has

emerged as an essential tool for defining and detecting these

disorders (2,6). The Chicago classification using HRM

is helpful for the diagnosis and pretreatment evaluation of

esophageal achalasia (7). The

integrated relaxation pressure (IRP) indicates the elevation of the

lower esophageal sphincter (LES) pressure for several seconds after

swallowing (8). In the Chicago

classification, this value serves as the starting point for

developing the algorithm, indicating an abnormal motility disorder

(7). However, relying solely on

the IRP in the algorithm is often inconsistent with the clinical

diagnosis (9); therefore, a

comprehensive assessment by a physician, incorporating other

modalities, is usually necessary. The IRP value, essential for

diagnosis, is dynamic and influenced by factors such as

diaphragmatic activity, LES function, intrabolus pressure, and

catheter positioning (10,11). An accurate interpretation requires

a comprehensive assessment that extends beyond the numerical values

(11). Interpreting HRM poses

significant challenges and requires specialized expertise for an

accurate diagnosis. This exclusive reliance on specialists for this

diagnostic procedure has led to delays in identifying esophageal

motility disorders, such as achalasia.

Artificial intelligence (AI) can alleviate issues

associated with the clinical interpretation of HRM. Due to the

rarity of this disease, few studies have assessed AI in patients

with achalasia. Kou et al (12) first demonstrated a deep

learning-based model for diagnosing achalasia using HRM images,

employing a variational autoencoder (VAE). Surdea-Blaga et

al (13) demonstrated the

classification of swallowing disorders using the DenseNet201

convolutional neural network (CNN) architecture combined with the

automated Chicago classification, yielding 86% accuracy without

human intervention. Although AI-based tools are emerging in the

medical field, a black-box problem arises: they do not reveal how

or why they were concluded. In AI-based achalasia, whether AI

focuses on the same area as clinicians remains unclear.

In this study, we validated an automated diagnostic

system using AI to assess HRM. In addition, we utilized a gradient

class activation map (Grad-CAM) to evaluate the features of HRM,

where the AI focused on distinguishing achalasia from other

esophageal motor disorders.

Materials and methods

Data collection and ethical

approval

The research implementation system was conducted at

a single center. This retrospective study was approved by the

Nagasaki University Hospital Research Ethics Committee. This

retrospective study was approved by the ethics review board and the

requirement for informed consent was waived.

Data pre-processing

A total of 211 HRM images were de-identified to

protect patient confidentiality and were collected between December

2018 and August 2022 at the Nagasaki University Hospital. Typical

HRM images obtained from patients with achalasia who underwent POEM

were used as achalasia images, whereas HRM images from asymptomatic

individuals were used as normal controls. Images that were unclear

or diagnostically ambiguous were excluded from the analyses. Before

submitting the images for model training, each image was cropped to

remove the patient identification, machine settings, annotations,

and scale bars. High-resolution esophageal manometry was performed

using the Starlet system (Star Medical, Tokyo, Japan).

We selected tracings from ten test swallows for

analysis (n=22 patients; 211 images): achalasia type I, 67 images;

achalasia type II, 30 images; achalasia type III, 9 images;

hypercontractile esophagus, 20 images; and normal esophageal

motility, 97 images. We used the raw data, which contained only the

markers mentioned above (vertical white lines) preceding each wet

swallow. The manometry software enabled the storage of 60 s long

images of the recordings, which represented the raw images. The

region of interest (wet swallowing) was marked with a white

vertical line during the procedure. For each patient, we created a

folder with ten images, with each image representing a test

swallow.

Each set is assigned a diagnostic category. We used

five diagnostic categories as follows: normal, type I achalasia,

type II achalasia, type III achalasia, and hypercontractile

esophagus, based on the Chicago v3.0 classification for esophageal

motility disorders (7).

Developing a deep learning

algorithm

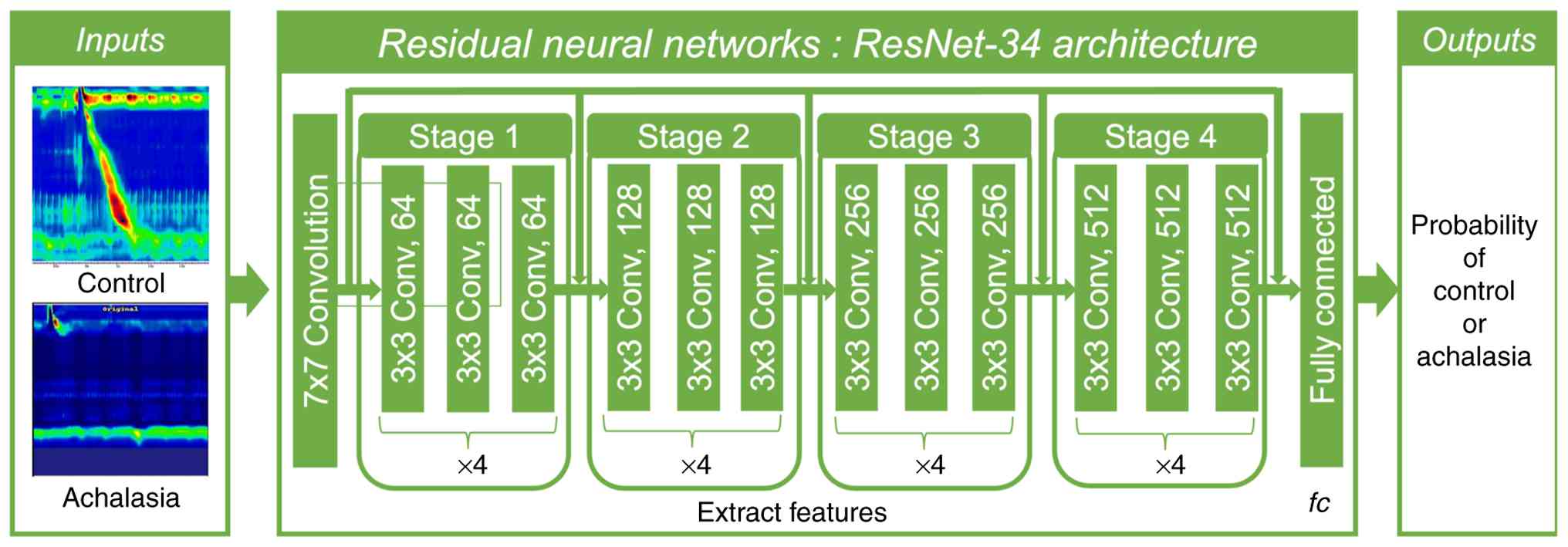

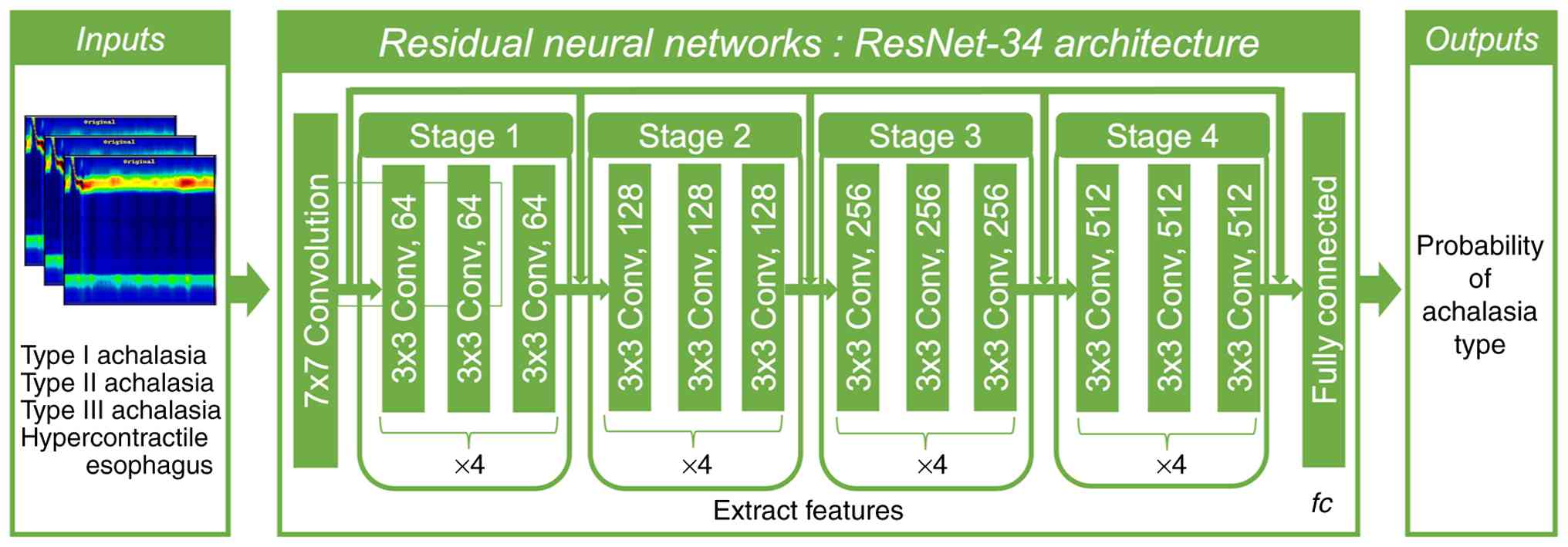

Achalasia was predicted by using the CNN. The

ResNet-34 network was used as the backbone of the encoder network

to encode the downsampling layer of the image. The model was

trained using Python 3.8 (Python Software Foundation, Beaverton,

OR, USA), Pytorch 1.8.1 (The Linux Foundation), and an Nvidia RTX

A6000 graphics card. The achalasia prediction training process

utilized a mean-squared error loss function and an Adam optimizer

with a batch size of 4; the learning rate decreased linearly from

5e-4 to 1e-6.

Grad-CAM method

Grad-CAM was used to reconstruct the image and

localize intensive areas for feature extraction. This method

identifies the image features used by a CNN to perform the

decision-making process, thereby enabling an understanding of the

predictive features determined by the trained model. We used

Grad-CAM to identify key abnormal features in the dataset. Regions

with high feature extraction intensities were assumed to be key

points in identifying anomalies.

Dimensions reduction analysis

Principal component analysis (PCA) and

three-dimensional t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding

(3D-tSNE) were used for feature analysis of the entire image

(14). PCA was used to reduce the

dimensions. A TensorBoard Embedding Projector, which offers 3D-tSNE

views, was used to compute the top ten principal components. These

components were projected onto a combination of three components.

The most popular nonlinear dimensionality reduction technique is

t-SNE (15).

Statistical analysis

Testing accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity, as

calculated from the confusion matrix, were used to evaluate the

models. The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve, which is

a graphical plot highly correlated with the confusion matrix, was

also used as an evaluation index. Diagnostic accuracy based on the

confusion matrix was calculated as follows: (true positives + true

negatives)/(true positives + true negatives + false positives +

false negatives). All statistical analyses were performed using the

R statistical software (version 4.1.1; The R Foundation for

Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Statistical significance

was set at P<0.05.

Results

All patients with achalasia included in the study

were treatment-naïve and had no prior interventions, such as

balloon dilation, Heller myotomy, or peroral endoscopic myotomy

(POEM) (Table I). The training

process for the achalasia-2CNN is illustrated in Fig. 1. First, we developed an achalasia

prediction model using HRM with CNN (Fig. 1). The ResNet-34 model, which has

already been proven to be versatile, was used for transfer

learning. Two hundred images were divided into training and

validation datasets, and a CNN based primarily on the PyTorch

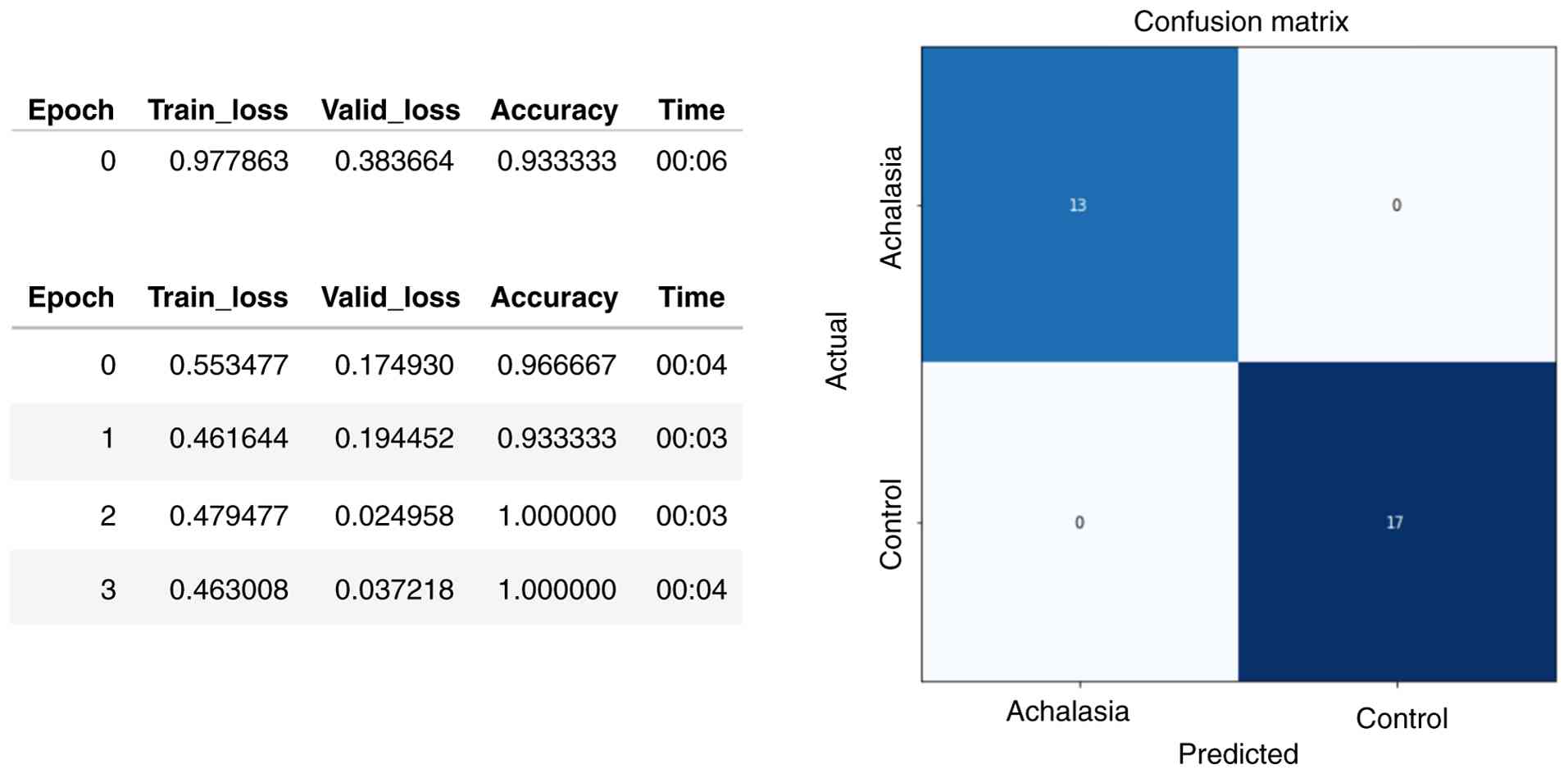

framework was used. With training, the accuracy of the training and

validation sets increased, and the loss value decreased. The

accuracy of the validation set was highest in the fourth epoch of

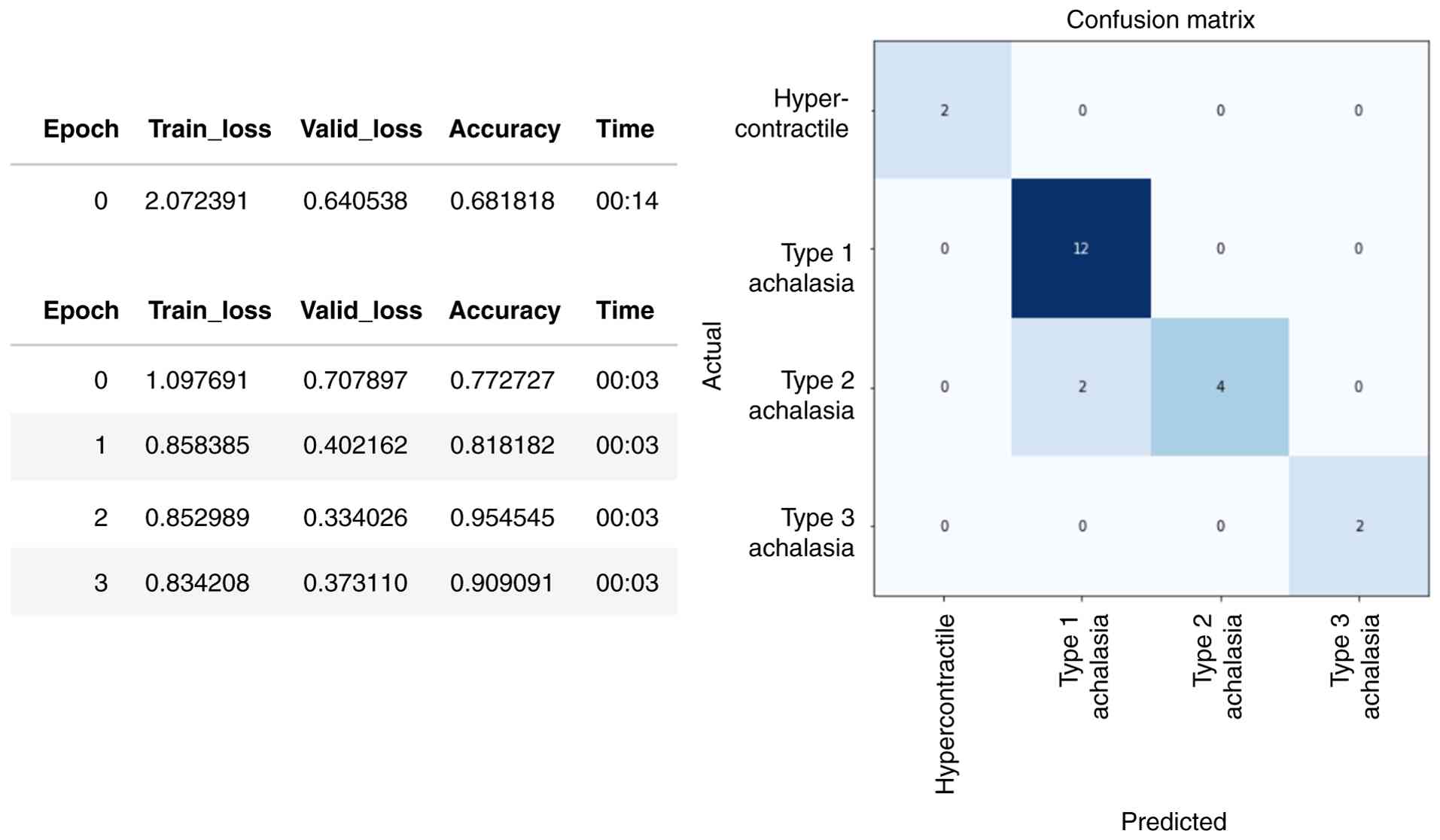

training (Fig. 2, left panel).

Fig. 2 (right panel) shows that

the confusion matrix of the achalasia-CNN optimal model was 100%

accurate for the external test set, with both sensitivity and

specificity reaching 100%. The receiver operating characteristic

(ROC) curve, area under the curve (AUC), sensitivity, and

specificity are shown in Table SI

and Fig. S1.

| Table IPatient characteristics. |

Table I

Patient characteristics.

|

Characteristics | Achalasia

(n=12) | Normal (n=9) |

|---|

| Age, years | 41 (16-89) | 72 (50-82) |

| Sex (male) | 7(58) | 6(67) |

| Eckardt score

(normal, ≤3) | 7 (1-10) | 0 (0-0) |

| Prior treatment

(yes) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| IRP, mmHg (normal,

≤25 mmHg) | 23.6

(0.6-55.0) | 10.4

(3.6-18.5) |

| Maximum DCI,

mmHg·sec·cm (normal range, 450-8,000 mmHg·sec·cm) | 796.1

(397.0-493,490.0) | 1,701.1

(238.1-3,713.1) |

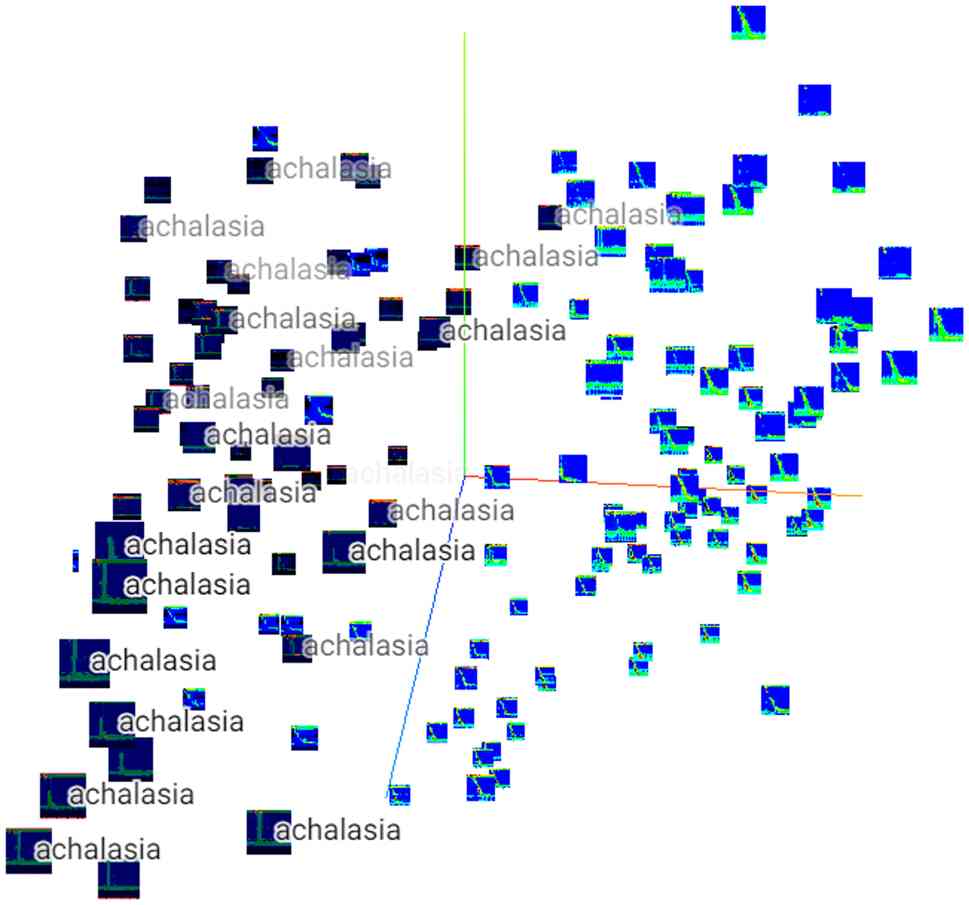

Owing to the nearly 100% correct response rate, and

despite the small dataset, PCA was performed on the characteristics

of the dataset. The HRM of patients with achalasia was distributed

mainly on the left side of Fig. 3,

indicating that the features of each HRM image differed between the

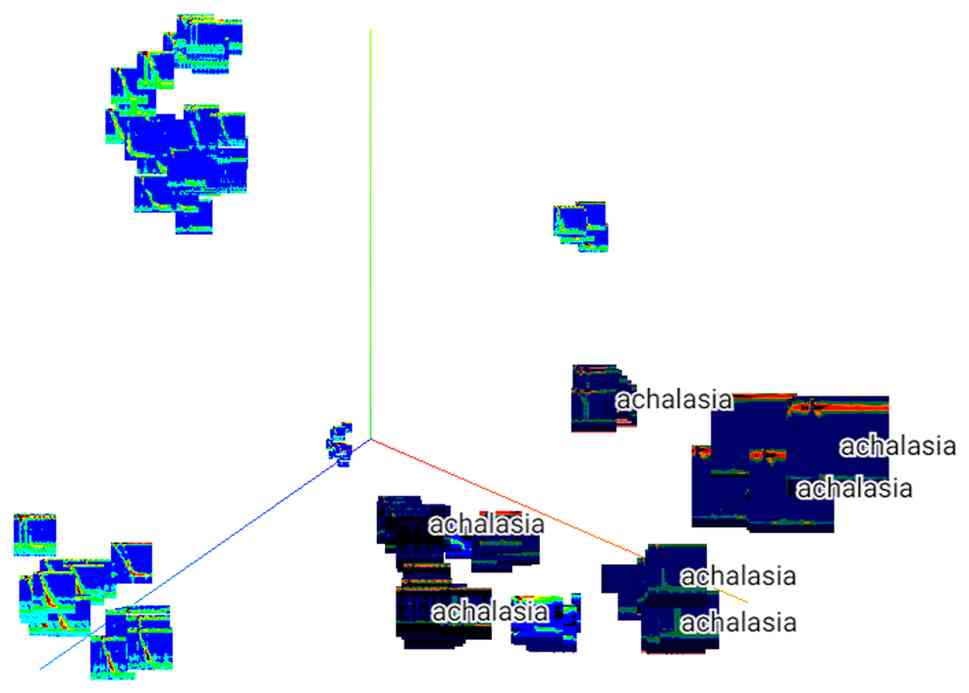

controls and patients with achalasia. Similarly, a 3D-tSNE

analysis, a dimensionality removal method, was performed (Fig. 4), which showed that the achalasia

group could be further subdivided into several groups, suggesting

the possibility of extracting features using an achalasia-type

classification.

The difference in HRM features between the controls

and patients with achalasia, even in the absence of a large number

of HRM images, suggests that deep learning may be predominantly

predictive of the disease. Thus, predictors of each type of

achalasia were developed using the same methods.

Next, we developed an achalasia-type prediction

model using HRM with deep learning. The confusion matrix in

Fig. 5 shows the predictions for

each type. Of the 22 validation datasets, two were incorrectly

classified as type 1 for type 2 achalasia; however, the others were

correctly classified (Fig. 6).

These results demonstrate that deep learning can achieve high

accuracy rates in HRM diagnosis, even with small datasets. The

comprehensive performance metrics are presented in Table SII and Fig. S2.

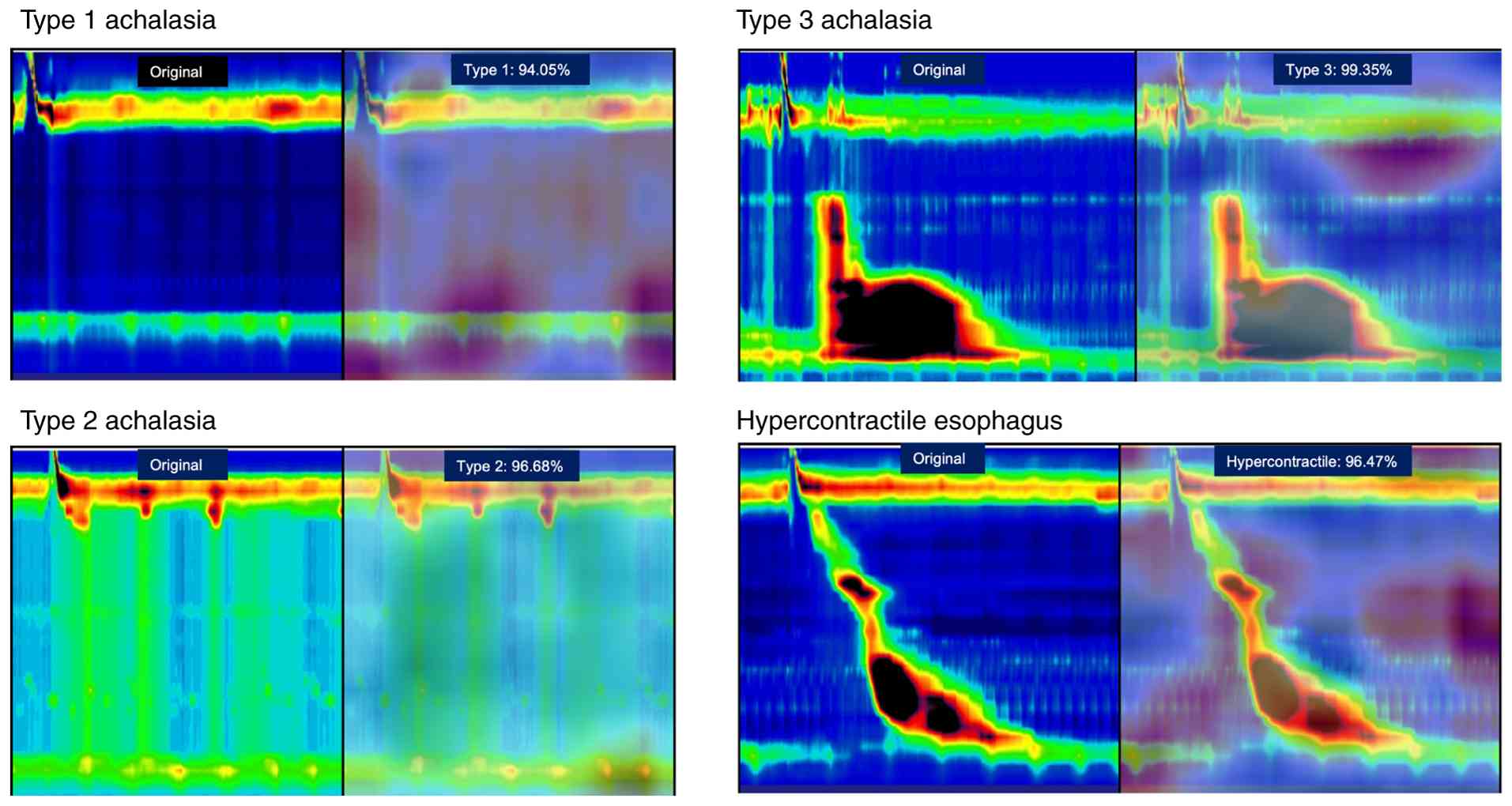

The legends visualized using Grad-CAM are shown in

Fig. 7. The images were reviewed

by two achalasia diagnosticians, primarily based on the diagnosis,

with high-signal images in the heatmap of the LES pressure region,

which is a crucial area for achalasia diagnosis.

When reexamining the areas of focus of Grad-CAM, we

found that pan-esophageal pressurization, which is continuous with

upper esophageal sphincter contraction, is a feature of type 2

achalasia (Fig. S3).

Interestingly, these features are not found in type 1 achalasia,

suggesting that they may be imaging features of type 2

achalasia.

Discussion

In recent years, multimodal therapy combining

surgical resection with chemotherapy, chemoradiotherapy, and

immunotherapy has become widely adopted for malignant esophageal

diseases such as esophageal cancer, leading to significant

improvements in patient prognosis (16-19).

Furthermore, advances in endoscopic diagnosis have enabled earlier

detection of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC), and

endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) for early lesions has

markedly improved prognosis (20,21).

In contrast, benign esophageal motility disorders,

such as achalasia, require precise functional evaluation and have

often been overlooked due to the complexity of diagnostic tools and

a limited comprehensive understanding of these conditions (22,23).

HRM serves as a highly valuable functional imaging examination

tool, and its diagnostic accuracy and progression are pivotal for

future elucidation and treatment of the underlying causes of

esophageal motility disorders (1,9,24).

Once achalasia is accurately diagnosed using HRM, patients can

experience marked symptom improvement through appropriate

therapeutic interventions, such as peroral endoscopic myotomy

(POEM) or Heller-Dor surgery (1,25,26).

However, the diagnosis of esophageal motility

disorders using HRM can be highly challenging. Even in achalasia,

cases with normal IRP values (9 out of 12 patients, within the

normal range of ≤25 mmHg) were observed in our cohort, and such

patients cannot always be accurately diagnosed, even when the

Chicago Classification is applied. Several studies have reported

the presence of achalasia with normal IRP values. Proposed

mechanisms include impaired esophagogastric junction opening due to

fibrotic changes of the LES (27),

as well as advanced age or pronounced esophageal tortuosity and

dilatation (28). In addition,

when using the Starlet catheter, Type I achalasia may present with

lower IRP values than expected (29). Therefore, diagnosing esophageal

motility disorders based on HRM topography, rather than relying

solely on numerical indices such as IRP, is essential. However,

describing and quantifying the image features that serve as

diagnostic criteria remains challenging. The present results

demonstrate that AI-assisted diagnosis can be a valuable approach

for identifying achalasia.

Rare esophageal motility disorders, such as distal

esophageal spasm (DES) and esophagogastric junction outflow

obstruction (EGJOO), have been reported in previous studies

(30). Achalasia is characterized

by a selective loss of inhibitory myenteric neurons in the distal

esophagus and LES, resulting in impaired esophagogastric junction

(EGJ) relaxation and loss of normal peristalsis (31). High-resolution manometry shows an

elevated IRP with absent peristalsis, with type I-III subtypes

distinguished by the presence of panesophageal pressurization or

premature spastic contractions. In contrast, EGJ outflow

obstruction is defined in the Chicago Classification as an elevated

median IRP with preserved- or only weakly impaired-peristalsis, and

is considered a heterogeneous manometric pattern that may reflect

early or variant achalasia, mechanical obstruction (e.g., hiatal

hernia, stricture, malignancy), or post-surgical changes rather

than a single primary motility disorder (32). Accordingly, the current Chicago

Classification v4.0 requires not only HRM findings but also

supportive evidence from endoscopy, timed barium esophagram, or

functional lumen imaging probe (FLIP) to distinguish clinically

relevant EGJOO from incidental manometric abnormalities (33). Distal esophageal spasm (DES) is

thought to result from an imbalance between excitatory and

inhibitory innervation confined mainly to the distal esophagus; HRM

in DES demonstrates premature contractions (distal latency <4.5

s) in ≥20% of swallows with normal EGJ relaxation, typically in

patients with dysphagia or non-cardiac chest pain (34). Thus, while all three conditions

share abnormalities in inhibitory neural control of the esophagus,

achalasia is defined by impaired EGJ relaxation with absent

peristalsis, EGJOO by impaired EGJ relaxation with preserved

peristalsis, and DES by premature distal contractions with normal

EGJ relaxation. In HRM, premature contractions can also be observed

in type III achalasia, and some achalasia cases may present with

normal IRP values, making it easily confused with DES. Moreover,

EGJOO cannot be accurately diagnosed based solely on HRM findings;

additional evaluations, such as endoscopy, timed barium esophagram,

or FLIP, are required to confirm true obstruction. Therefore, we

considered DES and EGJOO to be inappropriate as the initial targets

for AI model development.

In this study, we developed and validated an

achalasia prediction and classification model using HRM with deep

learning. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time AI

has demonstrated the potential to support medical practice by

visualizing AI prediction sites using Grad-CAM and reevaluating

them from a physician's perspective. Few reports are available on

the use of deep learning for HRM images. For example, models based

on VAE and DenseNet201(35) have

been shown to achieve high accuracy rates, reaching approximately

93% in classifying esophageal motility disorders (36). In addition, Kou et al

(37) reported that a Long

Short-Term Memory (LSTM) model achieved a correct classification

rate of 88% for the Chicago Classification using HRM images. We

employed a relatively generic convolutional neural network,

ResNet-34(38), with transfer

learning for HRM image classification, achieving a correct

classification rate of 95%, consistent with prior deep-learning

studies. To investigate the underlying cause, we conducted PCA and

3D-tSNE analyses, which indicated that the discriminative challenge

could be advantageous for AI in distinguishing between normal HRM

and achalasia cases, given the fundamental differences in the image

features. Although the internal validation yielded AUCs of 1.000

and very high sensitivity and specificity, these figures should be

regarded as optimistic estimates rather than evidence of perfect

clinical performance. The validation sets were small (22 cases for

the multiclass task and 30 cases for the binary task), and with

such sample sizes, an empirically perfect ROC curve can occur when

the model ranks all cases correctly in a single split. In addition,

we fine-tuned a pre-trained ResNet-34 model on data from a single

source, which increases the risk of overfitting to the local data

distribution. Therefore, the present results should be interpreted

as showing that the model can separate these particular data well,

and not that it will achieve 100% accuracy in broader practice.

Future studies should include repeated cross-validation and, more

importantly, external validation in a larger and more heterogeneous

cohort.

Previous studies have reported that AI prediction of

HRM images is helpful for the Chicago classification of achalasia,

achieving a high accuracy level of 81-93% (37,39).

In this study, our validation dataset yielded a classification

accuracy of 95% for the Chicago Classification groups. Furthermore,

we not only developed a classification model but also applied

Grad-CAM to visualize the regions contributing to the AI's

predictions and reviewed all images from the perspective of

esophageal specialists. The Grad-CAM results also focused on LES

pressure in the HRM image, demonstrating that the LES plays a

crucial role in representing pathological function, as mentioned

previously (40). These findings

are valuable for guiding treatment choices. Grad-CAM images can be

instrumental in determining whether to cut or preserve the LES

during procedures such as peroral endoscopic myotomy, diffuse

esophageal spasm, and hypercontractile esophagus, which are

collectively referred to as esophageal motility disorders (30).

In the future, we plan to introduce our developed

model in medical practice and investigate its potential not only

for the identification of achalasia but also as a tool for medical

education, supporting residents and other physicians through

AI-assisted diagnostics.

A limitation of HRM is that it is primarily used to

evaluate rare diseases, making validation with large datasets and

balanced case designs challenging. Therefore, validation on large

datasets and with a balanced case design is difficult. Although a

discriminator and classification model for achalasia was developed

in this study, further development and validation of the model were

constrained by the lack of sufficient training data for other rare

esophageal diseases. Future directions may include the

implementation of abnormality-detection models based on generative

adversarial networks, which hold promise for addressing these

limitations.

In conclusion, our AI-based HRM assistance system

not only enhances diagnostic accuracy but also offers clinicians

new insights and interpretative perspectives for HRM evaluation.

Further large-scale studies are required to validate its

utility.

Supplementary Material

Binary ROC curve for control vs.

achalasia (positive=achalasia). The solid line is the ROC curve;

the diagonal dotted line indicates the line of no discrimination.

AUC, 1.000 (bootstrap 95% CI, 1.000-1.000). The sensitivity,

specificity and accuracy at a fixed probability threshold of 0.5

are reported in Table SI. AUC,

area under the curve; ROC, receiver operating characteristic.

Multiclass ROC curves (one vs. rest)

for type 1, type 2 and type 3 achalasia, and hypercontractile

esophagus. Solid lines denote class-specific ROC curves; the dashed

line indicates the micro-average ROC. The diagonal dotted line

indicates the line of no discrimination. AUCs: Class-wise, 1.000

for all classes; micro-average, 0.999 (95% CI, 0.996-1.000);

macro-average, 1.000 (95% CI, 1.000-1.000). The macro-average AUC

value is reported; however, a macro-average ROC curve is not

displayed because the macro-average AUC represents an average of

the class-specific AUCs and does not correspond to a single ROC

curve. AUC, area under the curve; ROC, receiver operating

characteristic.

Examples of gradient class activation

map images. In achalasia type 2, a persistent increase in

panesophageal pressure was observed accompanied by lower esophageal

sphincter and UES contraction (upper panel; yellow arrow). By

contrast, patients with achalasia type 1 exhibit no concurrent

increase in esophageal pressure during UES contraction (lower

panel; yellow arrow). This observation may serve as an imaging

characteristic specific to achalasia type 2. The percentage

indicates the predicted probability for each class obtained from

the softmax output. UES, upper esophageal sphincter.

Comprehensive performance metrics for

binary tasks (control vs. achalasia; positive = achalasia).

Comprehensive performance metrics for

multiclass tasks (type 1, type 2 and type 3 achalasia, and

hypercontractile esophagus).

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study are not

publicly available because they contain information that could

compromise the privacy of research participants, but may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

MT and YN conducted the experiments and wrote the

manuscript. HMin, NY, YA and HMiy made substantial contributions to

the conception and design of the study. MT, HI, JS, TA, KH, MK, KM

and HMin contributed to acquisition and analysis of data. NY, YA

and HMiy critically revised the manuscript for important

intellectual content. HMin, JS and YN confirm the authenticity of

all the raw data. All authors have read and approved the final

version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the

Nagasaki University Hospital Research Ethics Committee (approval

no. 23041703-2; Nagasaki, Japan), and the need for informed consent

was waived. The hospital website ensures that patients have the

right to refuse to share information through an opt-out system.

Patient consent for publication

Patient consent for publication was obtained using

an opt-out approach, whereby the study information was publicly

disclosed, as approved by the Nagasaki University Hospital Research

Ethics Committee.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Use of artificial intelligence tools

During the preparation of this work, artificial

intelligence tools were used to improve the readability and

language of the manuscript or to generate images, and subsequently,

the authors revised and edited the content produced by the

artificial intelligence tools as necessary, taking full

responsibility for the ultimate content of the present

manuscript.

References

|

1

|

Boeckxstaens GE, Zaninotto G and Richter

JE: Achalasia. Lancet. 383:83–93. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Vaezi MF, Pandolfino JE, Yadlapati RH,

Greer KB and Kavitt RT: ACG clinical guidelines: Diagnosis and

management of achalasia. Am J Gastroenterol. 115:1393–1411.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Vaezi MF, Pandolfino JE and Vela MF: ACG

clinical guideline: Diagnosis and management of achalasia. Am J

Gastroenterol. 108:1238–1249, 1250. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Naik RD, Vaezi MF, Gershon AA,

Higginbotham T, Chen JJ, Flores E, Holzman M, Patel D and Gershon

MD: Association of achalasia with active varicella zoster virus

infection of the esophagus. Gastroenterology. 161:719–721.e2.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Gaber CE, Cotton CC, Eluri S, Lund JL,

Farrell TM and Dellon ES: Autoimmune and viral risk factors are

associated with achalasia: A case-control study. Neurogastroenterol

Motil. 34(e14312)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Yamasaki T, Tomita T, Mori S, Takimoto M,

Tamura A, Hara K, Kondo T, Kono T, Tozawa K, Ohda Y, et al:

Esophagography in patients with esophageal achalasia diagnosed with

high-resolution esophageal manometry. J Neurogastroenterol Motil.

24:403–409. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Kahrilas PJ, Bredenoord AJ, Fox M, Gyawali

CP, Roman S, Smout AJ and Pandolfino JE: International High

Resolution Manometry Working Group. The Chicago Classification of

esophageal motility disorders, v3.0. Neurogastroenterol Motil.

27:160–174. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

do Carmo GC, de Assis Mota G, da Silva

Castro Perdoná G and de Oliveira RB: Integrated relaxation pressure

and its diagnostic ability may vary according to the conditions

used for HREM recording. Dysphagia. 39:746–756. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Cha B and Jung KW: Diagnosis of dysphagia:

High resolution manometry & EndoFLIP. Korean J Gastroenterol.

77:64–70. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar : (In Korean).

|

|

10

|

Czako Z, Surdea-Blaga T, Sebestyen G,

Hangan A, Dumitrascu DL, David L, Chiarioni G, Savarino E and Popa

SL: Integrated relaxation pressure classification and probe

positioning failure detection in high-resolution esophageal

manometry using machine learning. Sensors (Basel).

22(253)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Gong EJ: Integrated relaxation pressure

during swallowing: An Ever-changing metric. J Neurogastroenterol

Motil. 27:151–152. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Kou W, Carlson DA, Baumann AJ, Donnan E,

Luo Y, Pandolfino JE and Etemadi M: A deep-learning-based

unsupervised model on esophageal manometry using variational

autoencoder. Artif Intell Med. 112(102006)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Surdea-Blaga T, Sebestyen G, Czako Z,

Hangan A, Dumitrascu DL, Ismaiel A, David L, Zsigmond I, Chiarioni

G, Savarino E, et al: Automated Chicago classification for

esophageal motility disorder diagnosis using machine learning.

Sensors (Basel). 22(5227)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Luus F, Khan N and Akhalwaya I: Active

learning with tensorboard projector. arXiv.org, 2019.

|

|

15

|

Van der Maaten L and Hinton G: Visualizing

data using t-SNE. J Mach Learn Res. 9:2579–2605. 2008.

|

|

16

|

Kanamori K, Koyanagi K, Ozawa S, Yamamoto

M, Ninomiya Y, Yatabe K, Higuchi T and Tajima K: Multimodal therapy

for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma according to TNM staging in

Japan-a narrative review of clinical trials conducted by Japan

clinical oncology group. Ann Esophagus. 6(32)2023.

|

|

17

|

Koyanagi K, Kanamori K, Ninomiya Y, Yatabe

K, Higuchi T, Yamamoto M, Tajima K and Ozawa S: Progress in

multimodal treatment for advanced esophageal squamous cell

carcinoma: Results of multi-institutional trials conducted in

Japan. Cancers (Basel). 13(51)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Higuchi T, Shoji Y, Koyanagi K, Tajima K,

Kanamori K, Ogimi M, Yatabe K, Ninomiya Y, Yamamoto M, Kazuno A, et

al: Multimodal treatment strategies to improve the prognosis of

locally advanced thoracic esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: A

narrative review. Cancers (Basel). 15(10)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Bolger JC, Donohoe CL, Lowery M and

Reynolds JV: Advances in the curative management of oesophageal

cancer. Br J Cancer. 126:706–717. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Yang H, Wang F, Hallemeier CL, Lerut T and

Fu J: Oesophageal cancer. Lancet. 404:1991–2005. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Nishizawa T and Suzuki H: Long-term

outcomes of endoscopic submucosal dissection for superficial

esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancers (Basel).

12(2849)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Averbukh LD and Tadros M: The role of

automatically generated Chicago classification in delayed achalasia

diagnosis. ACG Case Rep J. 7(e00345)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Müller M, Förschler S, Wehrmann T, Marini

F, Gockel I and Eckardt AJ: Atypical presentations and pitfalls of

achalasia. Dis Esophagus. 36(doad029)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Richter JE: High-resolution manometry in

diagnosis and treatment of achalasia: Help or hype. Curr

Gastroenterol Rep. 16(420)2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Inoue H, Minami H, Kobayashi Y, Sato Y,

Kaga M, Suzuki M, Satodate H, Odaka N, Itoh H and Kudo S: Peroral

endoscopic myotomy (POEM) for esophageal achalasia. Endoscopy.

42:265–271. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Schlottmann F and Patti MG: Esophageal

achalasia: Current diagnosis and treatment. Expert Rev

Gastroenterol Hepatol. 12:711–721. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Sato H, Takahashi K, Mizuno KI, Hashimoto

S, Yokoyama J and Terai S: A clinical study of peroral endoscopic

myotomy reveals that impaired lower esophageal sphincter relaxation

in achalasia is not only defined by high-resolution manometry. PLoS

One. 13(e0195423)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Kim E, Yoo IK, Yon DK, Cho JY and Hong SP:

Characteristics of a subset of achalasia with normal integrated

relaxation pressure. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 26:274–280.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Kawami N, Hoshino S, Hoshikawa Y,

Takenouchi N, Hanada Y, Tanabe T, Goto O, Kaise M and Iwakiri K:

Validity of the cutoff value for integrated relaxation pressure

used in the Starlet high-resolution manometry system. J Nippon Med

Sch. 86:322–326. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Morley TJ, Mikulski MF, Rade M, Chalhoub

J, Desilets DJ and Romanelli JR: Per-oral endoscopic myotomy for

the treatment of non-achalasia esophageal dysmotility disorders:

Experience from a single high-volume center. Surg Endosc.

37:1013–1020. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Rogers AB, Rogers BD and Gyawali CP:

Pathophysiology of achalasia. Ann Esophagus. 3(27)2020.

|

|

32

|

Rohof WOA and Bredenoord AJ: Chicago

classification of esophageal motility disorders: Lessons learned.

Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 19(37)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Yadlapati R, Kahrilas PJ, Fox MR,

Bredenoord AJ, Prakash Gyawali C, Roman S, Babaei A, Mittal RK,

Rommel N, Savarino E, et al: Esophageal motility disorders on

high-resolution manometry: Chicago classification version

4.0©. Neurogastroenterol Motil.

33(e14058)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Fox MR, Sweis R, Yadlapati R, Pandolfino

J, Hani A, Defilippi C, Jan T and Rommel N: Chicago classification

version 4.0© technical review: Update on standard

high-resolution manometry protocol for the assessment of esophageal

motility. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 33(e14120)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Huang G, Liu Z, Pleiss G, van der Maaten L

and Weinberger KQ: Convolutional networks with dense connectivity.

IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 44:8704–8716. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Popa SL, Surdea-Blaga T, Dumitrascu DL,

Chiarioni G, Savarino E, David L, Ismaiel A, Leucuta DC, Zsigmond

I, Sebestyen G, et al: Automatic diagnosis of high-resolution

esophageal manometry using artificial intelligence. J

Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 31:383–389. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Kou W, Galal GO, Klug MW, Mukhin V,

Carlson DA, Etemadi M, Kahrilas PJ and Pandolfino JE: Deep

learning-based artificial intelligence model for identifying

swallow types in esophageal high-resolution manometry.

Neurogastroenterol Motil. 34(e14290)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

He K, Zhang X, Ren S and Sun J: Deep

residual learning for image recognition. arXiv. [csCV]:770–778.

2015.

|

|

39

|

Kou W, Carlson DA, Baumann AJ, Donnan EN,

Schauer JM, Etemadi M and Pandolfino JE: A multi-stage machine

learning model for diagnosis of esophageal manometry. Artif Intell

Med. 124(102233)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Cohen S, Lipshutz W and Hughes W: Role of

gastrin supersensitivity in the pathogenesis of lower esophageal

sphincter hypertension in achalasia. J Clin Invest. 50:1241–1247.

1971.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|