Introduction

Pulmonary sequestration (PS) is a rare pulmonary

dysplasia, accounting for 0.2-6.4% of congenital pulmonary

malformations (1,2). Radiologically, PS can manifest as a

solid mass, a cystic lesion, a cavity or a pneumonic consolidation,

with mass-like lesions being one of the most common presentations

(3). It often presents as

recurrent pulmonary infections; however, fungal infections are

rare. Pulmonary cryptococcosis (PC) is an invasive fungal infection

primarily caused by Cryptococcus neoformans or

Cryptococcus gattii (4),

which is widely distributed in nature and can be found in bird

droppings, soil and decaying wood (5). This infection invades the respiratory

system after inhalation of cryptococcal spores, followed by the

central nervous system (6).

Cryptococcal infections range from superficial, affecting the skin

and mucous membranes, to deep-seated or disseminated, involving

internal organs. PC falls into the latter category, representing an

invasive fungal disease. While pathogenic fungi including

Cryptococcus are ubiquitous in the environment, symptomatic

infection typically occurs in individuals harboring specific risk

factors. An immunocompromised state constitutes the primary risk

factor for developing invasive cryptococcosis. This includes

individuals living with HIV or acquired immunodeficiency syndrome,

solid organ transplant recipients, patients with hematologic

malignancies and those receiving immunosuppressive therapies such

as corticosteroids or biologic agents (4,7).

However, it is increasingly recognized that a marked proportion of

PC cases, <30-50% in certain studies, occur in immunocompetent

hosts who often exhibit a history of environmental exposure to

soil, decaying wood or bird droppings (8). In these immunocompetent individuals,

the clinical presentation is often more indolent and the disease is

frequently localized to the lungs. However, to the best of our

knowledge, the coexistence of PS and PC is exceedingly rare, with

only one prior case reported in the published English literature to

date (9). In this previously

reported case, the cryptococcal infection was located within the

sequestered lung segment. The concomitant occurrence of these two

entities, particularly when presenting in separate lobes, poses

unique diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. The non-specific

radiological features often lead to an initial misdiagnosis of lung

cancer, potentially resulting in inappropriate management (6,8).

Therefore, enhancing awareness and understanding of this rare

co-occurrence is of notable clinical importance. The present case

report outlines a unique case of intralobar PS in the right lower

lobe of the patient, coexisting with PC in the contralateral left

lower lobe, representing an alternative clinical scenario from the

previously reported, aforementioned case. Within the present case

report, the clinical presentation, imaging findings, diagnostic

workup and successful treatment strategy are described, followed by

a review of the relevant literature, with the aim to provide

insights that will aid clinicians in the timely diagnosis and

appropriate management of such complex cases.

Case report

In August 2021, a 52-year-old Han male patient was

admitted to Taihe Hospital (Shiyan, China), due to a cough,

expectoration and chest tightness for 2 weeks. The patient

complained of respiratory symptoms and denied any other discomfort.

However, the total leukocyte (white blood cell) count was elevated

at 11.2x109/l (normal range, 3.5-9.5x109/l).

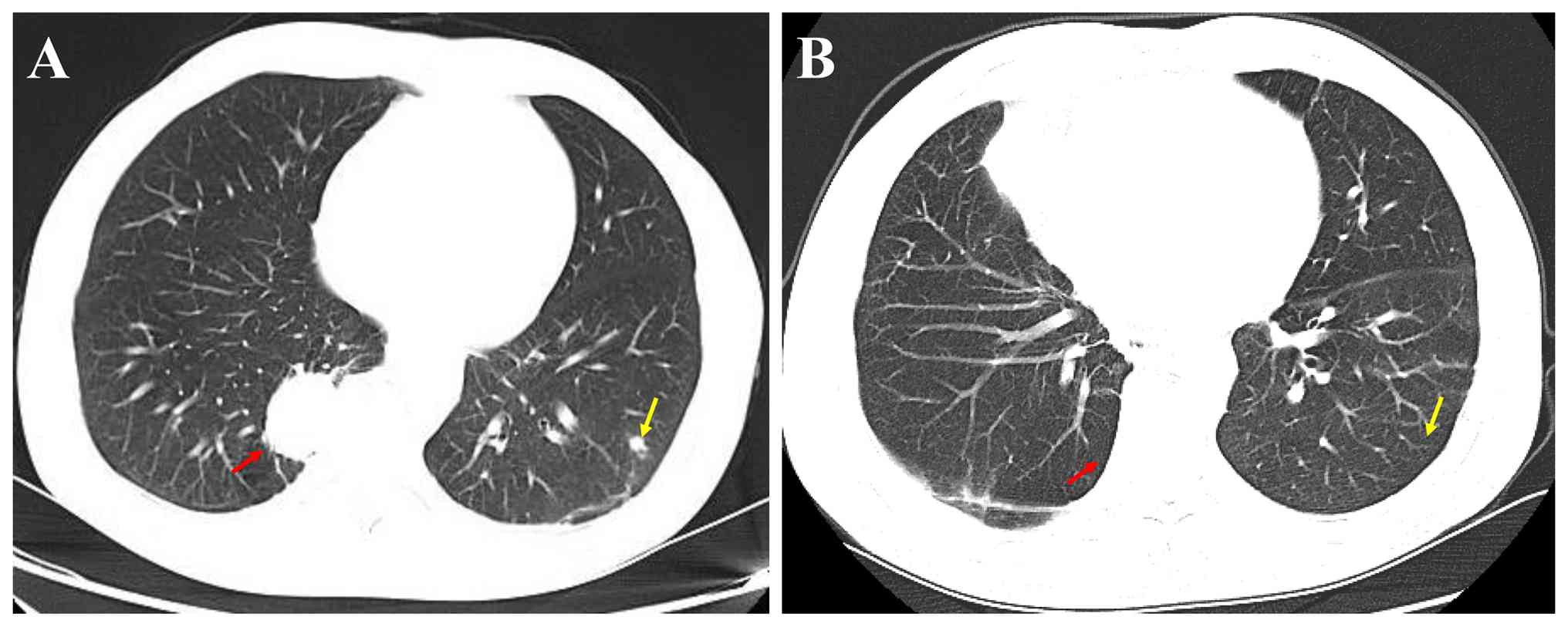

Contrast-enhanced chest CT scans showed an oval lesion measuring

3.5x2.7 cm in the right lower lobe of the lung (Fig. 1A). Notably, no definitive aberrant

systemic artery supplying the lesion was identified on the

contrast-enhanced CT scan due to institutional-specific practices.

Within the institution, three-dimensional CT angiography

reconstruction is performed only as part of a dedicated vascular CT

angiography protocol, which was not included in contrast-enhanced

CT. Furthermore, a 0.9x0.6 cm nodule in the lower lobe of the left

lung (Fig. 1A) was also observed,

which was initially suspected to be peripheral lung cancer. Given

the non-specific imaging features and the primary differential

diagnosis of lung cancer, a CT-guided percutaneous biopsy of the

right lower lobe lesion was conducted to obtain a definitive

diagnosis. The patient was immunocompetent, had no history of

recent travel, no history of exposure to pigeon manure or soil, no

history of smoking or drinking and no extensive use of hormones and

antibiotics before presenting to Taihe Hospital (Shiyan, China).

The medical history of the patient included chronic gastritis for

>2 years. Upon admission, the vital signs were within normal

limits: Heart rate was 77 bpm (normal, 60-100 bpm), blood pressure

was 112/73 mmHg (normal, <120/80 mmHg), respiratory rate was 20

bpm (normal, 12-20 bpm) and body temperature was 36.6˚C (normal,

36.1-37.2˚C). Physical examination showed normal breath sounds.

There were no skin lesions, lymph node enlargement or splenomegaly

present. Laboratory results showed that the whole blood leukocyte

count was 6.82x109/l [neutrophils, 63.6% (normal range,

50-70%); lymphocytes, 27.9% (normal range, 20-50%); monocytes, 6.2%

(normal range, 3-10%); eosinophils, 1.7% (normal range, 0.4-8%);

and basophils, 0.6% (normal range, 0-1%)], the red blood cell count

was 5.1x1012/l (normal range, 4.3 to 5.8

x1012/l), hemoglobin was 157 g/l (normal range, 130-175

g/l) and the platelet count was 231x109/l (normal range,

125-350x109/l). Blood glucose was measured as 4.65

mmol/l (normal range, 3.9-6.1 mmol/l), total bilirubin was 21.85

µmol/l (normal range, 3.42-20.5 µmol/l), aspartate aminotransferase

was 18 U/l (normal range, 0-40 U/l), alanine aminotransferase was

16 U/l (normal range, 0-50 U/l), lactate dehydrogenase was 99 IU/l

(normal range, 100-240 IU/l) and highly sensitive C-reactive

protein was 3.05 mg/l (normal range, 0-5 mg/l). Urinalysis and

microscopic examination results appeared normal. Tumor marker

analysis demonstrated that neuron-specific enolase [15.6 ng/ml

(normal range, 0-16.3 ng/ml)], carcinoembryonic antigen [1.25 µg

(normal range, 0-5 µg/l)] and ferritin [68.1 ng/ml, (normal range,

30-400 ng/ml)] exhibited normal levels. However, the cytokeratin 19

fragment exhibited a value of 5.8 µg/l (normal range, 0-3.3 µg/l),

which exceeded the normal upper limit of 2.5 µg/l. The patient had

normal T-lymphocyte subsets and was negative for HIV antibodies.

Sputum gram stain and bacterial culture showed no microorganisms

present. No acid-fast bacteria were found in acid-fast staining and

sputum culture. Fiberbronchoscopy was performed and revealed no

endobronchial lesions in either the right or left main bronchi.

Given the peripheral location of both the right lower lobe mass and

the left lower lobe nodule, a transbronchial biopsy was not

attempted. Bronchoalveolar lavage was performed in the right lower

lobe, targeting the region of the PS mass. The bacteriological,

cytological and pathological examinations of the bronchoalveolar

lavage fluid were negative. To obtain a definitive diagnosis, a

CT-guided percutaneous lung biopsy of the lesion in the lower lobe

of the right lung was performed, which was pathologically confirmed

to be PS. The histopathological examination of the biopsy specimens

revealed features highly suggestive of and consistent with PS,

including: i) Marked fibrotic thickening of the alveolar septa; ii)

chronic inflammation with lymphocyte infiltration; and iii)

dilated, cystically remodeled airspaces. These features, in

conjunction with the radiological presentation of a well-defined

mass in a typical location (posteromedial lower lobe), the absence

of an endobronchial lesion on bronchoscopy to suggest an

obstructive etiology, as well as the overall clinical context,

collectively supported a working diagnosis of PS. Malignancy was

ruled out by the absence of malignant cells. One week after

admission, a CT-guided percutaneous lung needle biopsy was

performed in the left lower lobe nodule, which was

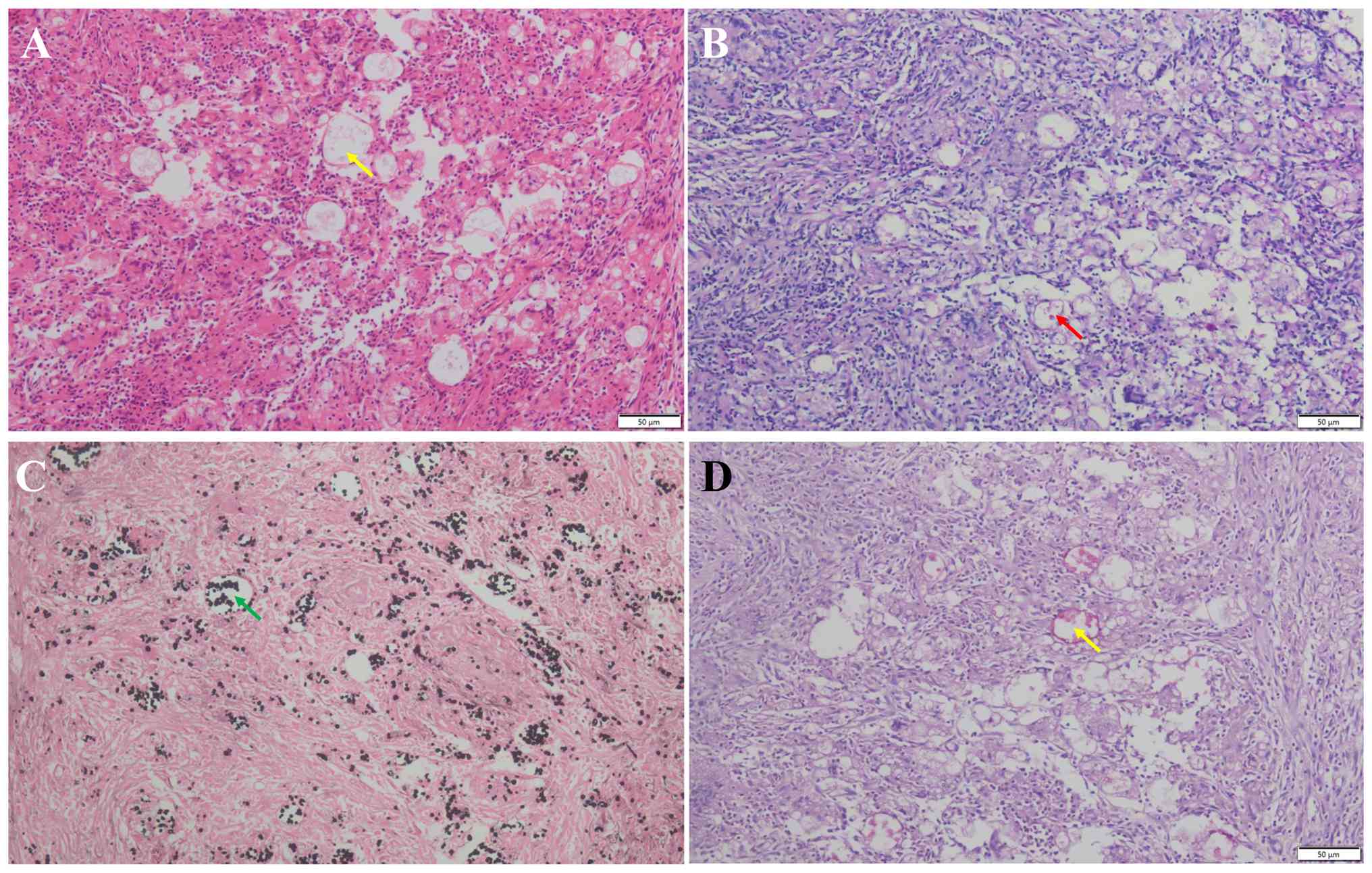

histopathologically confirmed to be a PC infection. Histologically,

hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining revealed granulomatous

inflammation with multinucleated giant cells containing a number of

round and oval yeast cells, which were identified as cryptococcus

through periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) stain, silver hexamethonium

(GMS) and mucocarsine staining (Fig.

2A-D). For histopathological examination, the percutaneous lung

biopsy specimens from the left lower lobe nodule were immediately

fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin at room temperature for

24-48 h. After routine processing, tissues were embedded in

paraffin and serially sectioned at 4-µm thickness. Sections were

stained with H&E for initial assessment. For fungal

identification, special stains including PAS, GMS and mucicarmine

were performed according to the manufacturer's standard protocols

(all reagents from Baso Inc.). Staining incubation was performed at

room temperature with durations as follows: PAS (15 min), GMS (60

min) and mucicarmine (10 min). All stained slides were examined

under a light microscope (Olympus CX31; Olympus Corp.).

Photomicrographs were captured using an attached digital camera

(Mshot MS60; Micro-shot Technology, Ltd.). The scale bars (50 µm)

and magnifications (x200) for each image are provided in Fig. 2A-D.

At two weeks after admission, the patient underwent

a video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery resection of PS. Notably,

the decision to perform a lobectomy, rather than a more limited

resection, was based on intraoperative findings and surgical

principles for PS, namely the sequestered lung tissue was diffusely

abnormal and involved multiple segments of the lower lobe.

Furthermore, the risk of injury to the often large, friable and

anomalous systemic vessels was deemed higher with a sublobar

resection, making lobectomy the safer and more definitive

procedure. Intraoperatively, careful dissection along the inferior

pulmonary ligament and the posteromedial aspect of the lesion

revealed a single aberrant systemic feeding artery. This vessel, ~6

mm in diameter, originated directly from the descending thoracic

aorta. It was meticulously isolated, doubly ligated with

non-absorbable suture and then divided prior to parenchymal

dissection. Securing this anomalous vessel was a step prioritized

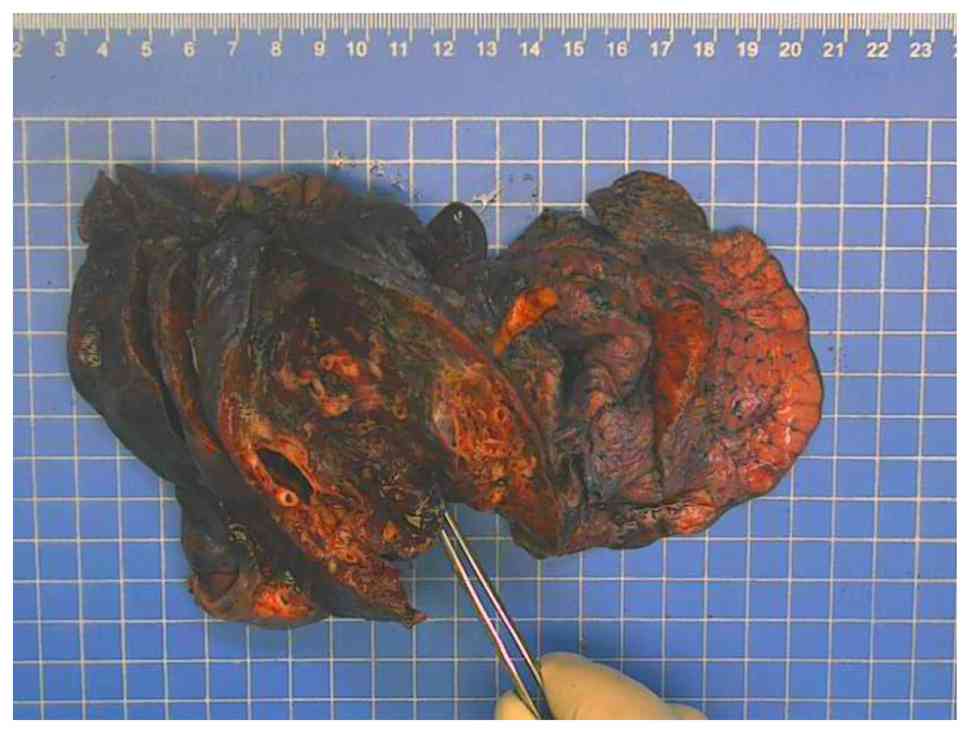

to prevent catastrophic hemorrhage. Macroscopically, the resected

lower lobe of the right lung was 17x11x3 cm and a capsule with a

size of 3.5x3x1.5 cm was observed in the section 3.5 cm from the

broken end of the bronchus (the contents had been lost; Fig. 3). The thickness of the capsule wall

was 0.1-0.2 cm.

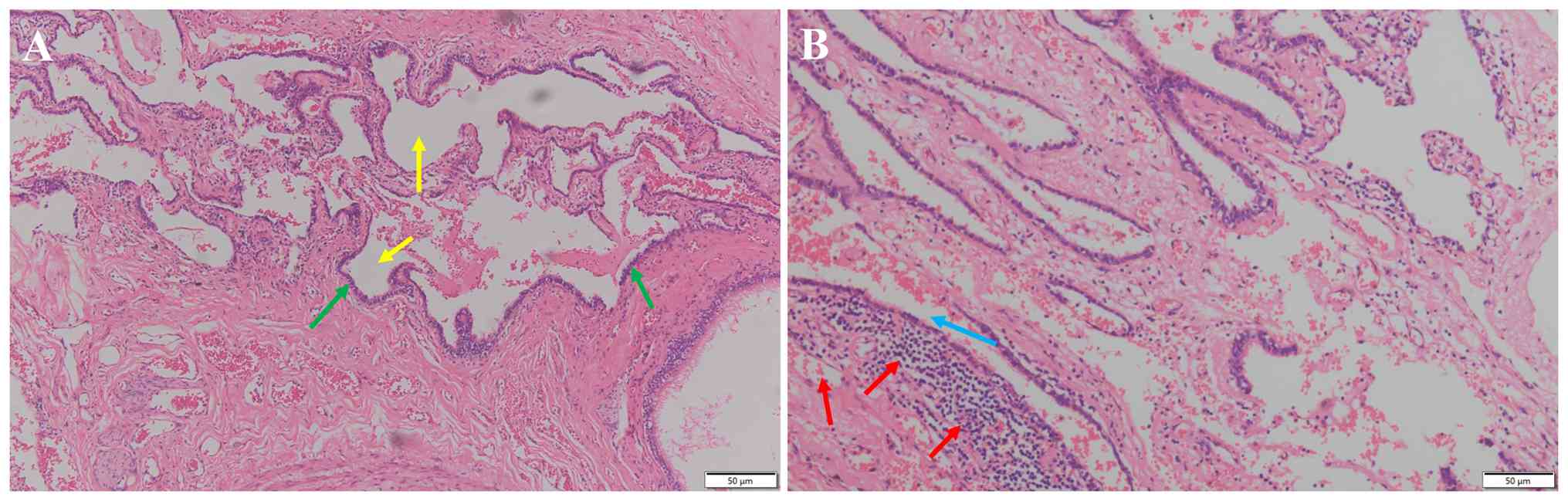

Histologically, compared to the normal lung

architecture, the alveolar septa were widened, interstitial fibrous

tissue was proliferated and there was increased lymphocyte

infiltration, along with hemorrhage, cystic change and histiocyte

aggregation-findings consistent with pulmonary sequestration

(Fig. 4). Notably, a thorough

histopathological examination of the entire resected PS specimen,

including specific staining (PAS and GMS) for fungi, revealed no

evidence of cryptococcal yeast forms or any other fungal elements

within the sequestered lung tissue. Finally, PS in the right lower

lobe and cryptococcal infection in the left lower lobe were

confirmed. Fluconazole (200 mg/day) was administered after surgery

for 6 months. Furthermore, for a total of 3 years after surgery,

the patient was regularly followed up in the Department of

Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine (Taihe Hospital; Shiyan,

China) and shown to be in good condition. In July 2024,

contrast-enhanced CT showed that there was no recurrence of

cryptococcal infection in the left lower lung and that the right

lower lung appeared stable after surgery (Fig. 1B).

Literature review and discussion

PC is an invasive lung fungal disease caused by

Cryptococcus neoformans or Cryptococcus gattii

(4), which typically presents in

immunosuppressed patients (10,11),

often as a solitary nodule mimicking malignancy (10). PS, on the other hand, is a

congenital malformation prone to recurrent infections (12). The concomitant occurrence of PS and

PC is exceedingly rare. The established standard for the diagnosis

of PS has previously been the demonstration of an aberrant systemic

artery on angiography. While contrast-enhanced CT with

three-dimensional reconstruction is highly sensitive and often

diagnostic by visualizing this vascular anomaly (13,14),

it is important to recognize that a subset of cases may present

without clear identification of the feeding vessel on standard

imaging (14-16).

The present case exemplifies this challenging scenario. The absence

of a definitively visualized aberrant artery on contrast-enhanced

CT, compounded by the patient's decision to forgo three-dimensional

reconstruction, shifted the diagnostic pathway towards tissue

confirmation. This underscores a key clinical point, that in the

presence of a radiologically ambiguous mass, particularly when

malignancy is a concern, percutaneous biopsy remains an

indispensable tool. The diagnosis of PS on biopsy is established by

identifying characteristic histopathological features of dysplastic

lung tissue, which in the present case included interstitial

fibrosis, chronic inflammation and cystic changes, findings that

are well-documented in the pathology literature on PS (17). The histopathological findings of

characteristic dysplastic lung tissue with cystic changes, fibrosis

and chronic inflammation can establish the diagnosis of PS even in

the absence of the classic angiographic finding of an aberrant

systemic feeding artery. Therefore, while non-invasive imaging is

still a first-line investigation tool, biopsy remains a key method

within ambiguous cases, in order to rule out malignancy and obtain

tissue supporting the clinical and radiological suspicion of PS.

Histopathological findings can support the diagnosis of PS when

interpreted in conjunction with characteristic imaging findings and

after excluding other causes of localized chronic lung pathology,

such as obstruction (1,12,17).

The present report acknowledges that biopsy findings

themselves are not specific. The definitive diagnosis of PS in the

present case was therefore not based on pathology alone, but on the

integration of the following: i) Typical radiological location and

appearance; ii) histopathology ruling out malignancy and showing

changes compatible with chronic sequestration/recurrent infection;

iii) bronchoscopic exclusion of an endobronchial obstructing lesion

(which would favor a diagnosis of obstructive pneumonia); and iv)

the subsequent surgical resection and pathological examination of

the entire specimen, which demonstrated the absence of a bronchial

communication, a key feature of PS.

The majority of PSs often present as solid masses,

with or without cavity lesions. Wei and Li (3) retrospectively analyzed the chest CT

characteristics of 1,106 PS cases and found that there were four

main types of PS, namely mass lesions (49.01%), cystic lesions

(28.57%), cavitary lesions (11.57%) and pneumonic lesions (7.96%).

Yue et al (13)

demonstrated that the accuracy (>95%) and sensitivity (>95%)

of CT angiography in diagnosing PS were relatively high, which was

considered to be comparable to the established standard, digital

subtraction angiography. In this case, PS exhibited a solid mass

shadow upon chest CT scans. PC is primarily observed in patients

who are immunosuppressed or those with a history of exposure to

soil, dust or pigeon droppings (4,8,18).

However, no history of immunosuppression or exposure was found in

the present case.

Currently, to the best of our knowledge, there is no

consensus on whether there is an association between PS and PC.

Only one previous case by Guan et al (9) has reported this coexistence, whereby

the cryptococcal infection was located within the sequestered lung

segment. Despite aggressive antifungal therapy, the pulmonary

infection relapsed, necessitating a lobectomy to eradicate the

source of persistent infection within the PS. By contrast, the

present case presents a novel pattern of ‘separated coexistence’,

whereby the PS was situated in the right lower lobe and the

cryptococcal nodule was identified as a distinct entity in the

contralateral left lower lobe; therefore, a ‘split-and-conquer’

strategy was employed, involving surgical resection of the PS

combined with targeted antifungal therapy for the PC. The surgery

was primarily aimed at addressing the PS itself, rather than

controlling a drug-refractory infection. The coexistence of PS and

PC in the present case, albeit in different lobes, raises the

question of a potential pathophysiological association beyond just

a coincidence. While the patient in the present case was

immunocompetent systemically, the local immune environment within a

PS may be altered, predisposing it to infections. A PS is

characterized by impaired bronchial communication and defective

drainage, leading to the stagnation of secretions (19,20).

This stagnant environment can compromise local mucociliary

clearance and create a niche susceptible to colonization by a

number of pathogens, including fungi. Furthermore, the chronic

inflammation and structural damage within the sequestered lung

tissue, as seen in the present case with lymphocyte infiltration

and fibrosis, could disrupt the normal local immune surveillance.

This concept of ‘local immunosuppression’ is supported by the

well-documented higher incidence of aspergillosis in patients with

PS compared with the general population (19). Although the cryptococcal infection

in the present case was in a separate lobe, it is plausible that

the patient had a generalized, subclinical susceptibility to

respiratory infections, with the PS and the left lower lobe nodule

representing two different manifestations of this susceptibility.

The route of cryptococcal spread to the sequestration, as suggested

in the literature, could be hematogenous, lymphatic or through the

pores of Kohn (9). Therefore,

while a causal relationship cannot be established from the present

case, the presence of PS may indicate a regional lung environment

that is more permissive to fungal establishment and proliferation.

The management of coexisting PS and PC should be tailored based on

the anatomical relationship between the two conditions (9,19).

The present case underscores the importance of a nuanced treatment

strategy. When PC is located within the sequestered lung segment,

surgical resection of the PS serves a dual purpose. It is both an

established treatment for the congenital malformation and an

effective means of eradicating the entrenched fungal infection. By

contrast, when PC presents as a separate lesion in a different

lobe, as seen in the present patient, a staged approach is

warranted. This involves surgical resection of the PS to address

the source of recurrent infection and potential complications,

combined with preoperative or postoperative antifungal therapy

targeted at the distinct PC nodule. This bifurcated strategy

optimizes outcomes by matching the intervention to the specific

pathological context.

Surgical resection is the optimal choice in the

treatment of PS. At present, PS accounts for 0.15-6.45% of

congenital lung malformations, 1.1-1.8% of lung resections and the

surgical detection rate is ~1.5% (21). A key procedure during this is

complete resection of the diseased lung tissue and ligation of the

blood supply vessels to prevent severe bleeding. The conventional

treatment consists of surgical resection of the PS, but in previous

years, endovascular embolization has been proposed as a valid

therapeutic alternative (22-27).

Deng et al (28) reported a

PS case presented with haemoptysis, coil embolization was performed

instead of surgery and no complications were found after the

operation. In addition, Bi et al (23) conducted a single-center,

retrospective study and assessed the safety and efficacy of

transarterial embolization for PS, showing a clinical success rate

of 90.9%. Borzelli et al (24) demonstrated that arterial

embolization was a valid and effective therapeutic alternative to

surgical resection in the treatment of PS. Based on previous

literature, endovascular embolization concurs the advantages of

less trauma, lower risk and fewer complications and may be the best

alternative to surgery for PS treatment.

According to 2010 updated clinical practice

guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Society of America

(4), amphotericin B combined with

fluconazole is recommended as a primary therapy regimen, followed

by fluconazole as consolidation therapy (4). To avoid the occurrence of reinfection

that destroys the adjacent lung parenchyma, resection of the

malformation is recommended in the presence of complications such

as persistent or recurrent infections, hemoptysis as well as in the

absence of antifungal agents. In the previously reported case

(9), the patient underwent right

lower lobectomy and received liposomal amphotericin B for 3 months,

after which the patient was stable. In the present case, PS was

removed and cryptococcal lesions were treated with anti-infectives

and 200 mg/day fluconazole was administered for 6 months.

Therefore, the accurate differentiation between PS, PC and lung

malignancy is of notable clinical importance, as it directly

determines the treatment strategy and spares patients from

potentially harmful and unnecessary therapies. In the present case,

the initial suspicion of peripheral lung cancer could have led to

more aggressive surgical intervention or even chemotherapy being

performed. Notably, the definitive diagnosis of PC guided targeted

antifungal therapy. The first-line treatment for cryptococcosis,

fluconazole, while generally well-tolerated, is not without risks.

Common side effects include gastrointestinal disturbances (nausea,

vomiting and abdominal pain), a skin rash and headache. More marked

adverse effects involve hepatotoxicity, evidenced by elevated liver

enzymes and rare but serious conditions such as QT interval

prolongation and alopecia (29,30).

Long-term administration, as required for consolidation therapy

(for example, 6-12 months), necessitates regular monitoring of

liver function. Had the pulmonary nodule been misdiagnosed as a

common bacterial infection, prolonged courses of broad-spectrum

antibiotics could have been prescribed, increasing the risk of

Clostridium difficile infection, fostering antimicrobial

resistance and causing dysbiosis without any clinical benefit

(30). Therefore, the combination

of contrast-enhanced CT and histopathological examination was key

in the present case, not only securing the correct diagnoses but

also ensuring that the patient received the most appropriate and

least harmful treatment. This manifested as surgical resection for

the PS and targeted, time-limited antifungal therapy for the PC,

thereby avoiding the consequences of misdirected and potentially

toxic medical or surgical interventions.

This present study exhibits a number of limitations.

Firstly, the spatial separation of the PS and PC lesions makes it

challenging to definitively establish a direct pathophysiological

association between the two conditions. A case with cryptococcal

infection within the sequestered segment itself would provide a

stronger model for investigating such a relationship. Second,

advanced immunological profiling could not be performed on the

resected lung tissue to characterize the local immune cell

populations and cytokine environment, which could have provided

mechanistic insights. Future research involving such cases should

aim to incorporate detailed microbiological and immunological

analyses of the sequestered tissue to improve the understanding of

the local factors that might predispose to specific infections such

as cryptococcosis.

The diagnostic challenge in the present case was

two-fold. First, the solid mass appearance of the PS in the right

lower lobe and the nodular presentation of PC in the left lower

lobe are both radiological mimics of primary lung malignancy, as

was initially suspected in the patient. This often leads to

unnecessary anxiety and could prompt more invasive procedures if

not correctly characterized. Second, the coexistence of two

different pathologies in one immunocompetent patient is uncommon.

There is a cognitive bias in clinical practice to seek a unifying

diagnosis. Upon identifying one pathology (PS), there is a risk of

attributing all abnormalities to this risk and overlooking a

second, independent entity (PC). Therefore, meticulous evaluation

of each lesion with appropriate diagnostic tools, such as

image-guided biopsy for histopathological and microbiological

confirmation, is key in such complex presentations to avoid missed

diagnosis and ensure both conditions are adequately addressed.

Overall, the unique present case of intralobar

pulmonary sequestration with a contralateral pulmonary

cryptococcosis nodule underscores that in the absence of a classic

systemic feeding artery on imaging, percutaneous biopsy is a key

step towards diagnosing PS and excluding malignancy. It

demonstrates the necessity of an anatomy-driven management

strategy, whereby spatially separated pathologies warrant a

combined approach of surgical resection for the PS and targeted

antifungal therapy for the PC. The definitive exclusion of

cryptococcal infection within the resected PS tissue argues for a

coincidental coexistence in this immunocompetent host, highlighting

the importance of evaluating each lesion independently rather than

seeking a unifying diagnosis in complex pulmonary

presentations.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

LH and JW conceived and designed the clinical study.

LH, DC, YueW, and DY were responsible for the acquisition,

analysis, and interpretation of patient data. YueW, DY and YunW

performed the histopathological and surgical data collection and

interpretation. JL and JF contributed to the radiological and

microbiological data interpretation. All authors participated in

drafting the manuscript and critically revising it for important

intellectual content. LH and JW supervised the study and

coordinated the follow-up. JW and DC confirm the authenticity of

all the raw data. All authors read and approved the final version

of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present report was approved by the ethics

committee of Taihe Hospital (approval no. 2024KS02) and performed

in accordance with the principles of Good Clinical Practice

following the Tri-Council guidelines.

Patient consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the

patient for anonymized information (including medical records, case

information and images) to be published in the present report.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Savic B, Birtel FJ, Tholen W, Funke HD and

Knoche R: Lung sequestration: Report of seven cases and review of

540 published cases. Thorax. 34:96–101. 1979.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Montjoy C, Hadique S, Graeber G and

Ghamande S: Intralobar bronchopulmonary sequestra in adults over

age 50: Case series and review. W V Med J. 108:8–13.

2012.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Wei Y and Li F: Pulmonary sequestration: A

retrospective analysis of 2625 cases in China. Eur J Cardiothorac

Surg. 40:e39–e42. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Perfect JR, Dismukes WE, Dromer F, Goldman

DL, Graybill JR, Hamill RJ, Harrison TS, Larsen RA, Lortholary O,

Nguyen MH, et al: Clinical practice guidelines for the management

of cryptococcal disease: 2010 Update by the infectious diseases

society of america. Clin Infect Dis. 50:291–322. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Swinne D, Deppner M, Laroche R, Floch JJ

and Kadende P: Isolation of Cryptococcus neoformans from

houses of AIDS-associated cryptococcosis patients in Bujumbura

(Burundi). AIDS. 3:389–390. 1989.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Yang R, Yan Y, Wang Y, Liu X and Su X:

Plain and contrast-enhanced chest computed tomography scan findings

of pulmonary cryptococcosis in immunocompetent patients. Exp Ther

Med. 14:4417–4424. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Zhou Y, Lin PC, Ye JR, Su SS, Dong L, Wu

Q, Xu HY, Xie YP and Li YP: The performance of serum cryptococcal

capsular polysaccharide antigen test, histopathology and culture of

the lung tissue for diagnosis of pulmonary cryptococcosis in

patients without HIV infection. Infect Drug Resist. 11:2483–2490.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Zhang Y, Li N, Zhang Y, Li H, Chen X, Wang

S, Zhang X, Zhang R, Xu J, Shi J and Yung RC: Clinical analysis of

76 patients pathologically diagnosed with pulmonary cryptococcosis.

Eur Respir J. 40:1191–1200. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Guan C, Chen H, Shao C, He L and Song Y:

Intralobar pulmonary sequestration complicating with cryptococcal

infection. Clin Respir J. 9:22–26. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Setianingrum F, Rautemaa-Richardson R and

Denning DW: Pulmonary cryptococcosis: A review of pathobiology and

clinical aspects. Med Mycol. 57:133–150. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Smith JA and Kauffman CA: Pulmonary fungal

infections. Respirology. 17:913–926. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Qian X, Sun Y, Liu D, Wu X, Wang Z and

Tang Y: Pulmonary sequestration: A case report and literature

review. Int J Clin Exp Med. 8:21822–21825. 2015.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Yue SW, Guo H, Zhang YG, Gao JB, Ma XX and

Ding PX: The clinical value of computer tomographic angiography for

the diagnosis and therapeutic planning of patients with pulmonary

sequestration. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 43:946–951. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Hertzenberg C, Daon E and Kramer J:

Intralobar pulmonary sequestration in adults: Three case reports. J

Thorac Dis. 4:516–519. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Corbett HJ and Humphrey GME: Pulmonary

sequestration. Paediatr Respir Rev. 5:59–68. 2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Büyükoğlan H, Mavili E, Tutar N, Kanbay A,

Bilgin M, Oymak FS, Gülmez I and Demir R: Evaluation of diagnostic

accuracy of computed tomography to assess the angioarchitecture of

pulmonary sequestration. Tuberk Toraks. 59:242–247. 2011.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Gezer S, Taştepe I, Sirmali M, Findik G,

Türüt H, Kaya S, Karaoğlanoğlu N and Cetin G: Pulmonary

sequestration: A single-institutional series composed of 27 cases.

J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 133:955–959. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Hu XP, Wang RY, Wang X, Cao YH, Chen YQ,

Zhao HZ, Wu JQ, Weng XH, Gao XH, Sun RH and Zhu LP: Dectin-2

polymorphism associated with pulmonary cryptococcosis in

HIV-uninfected Chinese patients. Med Mycol. 53:810–816.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Morikawa H, Tanaka T, Hamaji M and Ueno Y:

A case of aspergillosis associated with intralobar pulmonary

sequestration. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann. 19:66–68.

2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Sun X and Xiao Y: Pulmonary sequestration

in adult patients: A retrospective study. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg.

48:279–282. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Kestenholz PB, Schneiter D, Hillinger S,

Lardinois D and Weder W: Thoracoscopic treatment of pulmonary

sequestration. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 29:815–818. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Belczak SQ, da Silva IT, Bernardes JC, de

Macedo FB, Lucato LL, Rodrigues B and Zeque BS: Pulmonary

sequestration and endovascular treatment: A case report. J Vasc

Bras. 18(e20180110)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Bi Y, Li J, Yi M, Ren J and Han X:

Clinical outcomes of transarterial embolization in the treatment of

pulmonary sequestration. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 44:1491–1496.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Borzelli A, Paladini A, Giurazza F, Tecame

S, Giordano F, Cavaglià E, Amodio F, Corvino F, Beomonte Zobel D,

Frauenfelder G, et al: Successful endovascular embolization of an

intralobar pulmonary sequestration. Radiol Case Rep. 13:125–129.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Szmygin M, Pyra K, Sojka M and Jargiełło

T: Successful endovascular treatment of intralobar pulmonary

sequestration-an effective alternative to surgery. Pol J Radiol.

86:e112–e114. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Ellis J, Brahmbhatt S, Desmond D, Ching B

and Hostler J: Coil embolization of intralobar pulmonary

sequestration-an alternative to surgery: A case report. J Med Case

Rep. 12(375)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Roman S, Millet C, Mekheal N, Mekheal E

and Manickam R: Endovascular embolization of pulmonary

sequestration presenting with hemoptysis: A promising alternative

to surgery. Cureus. 13(e17399)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Deng Y, Fang X and Wu B: Coil embolization

to treat pulmonary sequestration in the right upper lobe. Interact

Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 35(ivac178)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Egunsola O, Adefurin A, Fakis A,

Jacqz-Aigrain E, Choonara I and Sammons H: Safety of fluconazole in

paediatrics: A systematic review. Eur J Clin Pharmacol.

69:1211–1221. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Patangia DV, Anthony Ryan C, Dempsey E,

Paul Ross R and Stanton C: Impact of antibiotics on the human

microbiome and consequences for host health. Microbiologyopen.

11(e1260)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|