Introduction

The Filoviridae family of RNA viruses

includes the highly contagious and lethal Ebola virus, which was

initially identified in 1976 in Sudan and the Democratic Republic

of the Congo (formerly Zaire), where it was responsible for two

epidemics of severe hemorrhagic fever that occurred at the same

time (1). The first-recorded

epidemic of the disease caused by the virus, termed Ebola virus

disease (EVD), occurred close to the Ebola River; thus, the virus

was named Ebola. Up to 90% case fatality rates have been observed

during certain outbreaks of the virus, which is regarded as one of

the most lethal viral pathogens worldwide (2). The Zaire, Sudan, Bundibugyo, Reston,

and Tai Forest ebolaviruses constitute the five species of Ebola

viruses that are currently known to exist (3). A linear, negative-sense RNA genome is

contained in filamentous, pleomorphic viral particles that encase

the encapsulated Ebola virus (4).

On January 11, 2023, the most recent Ebola virus

illness outbreak, was declared. According to the World Health

Organization (WHO), the epidemic began in September, 2022 in

Mubende District, Uganda, and was the fifth known outbreak caused

by the Sudan ebolavirus species. There were 142 confirmed cases, 55

fatalities and 22 suspected cases in the epidemic (5). The West African Ebola epidemic, which

began on March 23, 2014, in Guinea and was caused by the Zaire

ebolavirus species, was the largest Ebola outbreak in history. In

terms of worldwide public health, that epidemic resulted in ~28,652

total cases, 11,325 fatalities and a mortality rate of 40-70%

(6). Guinea, Liberia and Sierra

Leone were countries that were mostly affected by the epidemic; as

these countries were already afflicted by war and poverty, the

provision of essential care and containment measures was difficult

(7). Aside from the casualties

themselves, the outbreak had an impact on other healthcare

services, such as maternity and child health, the treatment of

human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and running vaccine programs

(8). Ebolaviruses are considered to

be zoonotic viruses, which means they are suspected to be

transferred from an animal to a human via direct contact with

bodily fluids from infected animals, or through contact with items

contaminated by these bodily fluids. Humans, once infected, can

further transmit the illness by coming into close touch with body

fluids, such as blood or saliva, or contaminated items and surfaces

(9). A spillover event occurs when

a disease, such as a virus, spreads from one species to another

species that is not its reservoir host (10). Understanding spillover occurrences

is critical for preventing the spread of emerging infectious

illnesses. It is considered that three species of fruit bats of the

Pteropodidae family are the natural reservoir host of the

Zaire ebolavirus, following various modeling and serological

experiments (11). The Ebola virus

enters the human body through mucous membranes or skin breaches.

Once in the body, the virus infects immune cells, particularly

macrophages and dendritic cells, and other cell types such as liver

cells, endothelial cells and fibroblasts (12). The incubation period for EVD can

range from 2 to 21 days, with an average of 5 to 7 days. The virus

replicates in the body of the host throughout this asymptomatic

incubation phase, and the host can only transmit the infection when

symptoms appear (13). Typical

symptoms of EVD in the early stages include fever, headache,

jaundice, myalgia and gastrointestinal symptoms such as nausea,

vomiting and diarrhea (13).

Infected patients may experience complications such as internal

bleeding or multi-organ malfunction as the illness advances

(13). For diagnosis, the virus can

be detected using various techniques, such as enzyme-linked

immunosorbent assay (ELISA), reverse transcription-polymerase chain

reaction (RT-PCR), serological tests and on-field rapid diagnostic

kits (14). The handling of

patients and patient samples requires the use of personal

protective equipment by medical personnel and stringent

decontamination regimes, while the study of viral samples requires

biosafety level 4-grade facilities (15).

The Ebola virus particle or virion is a complex

structure comprised of multiple unique components. The

single-stranded RNA genome, which runs ~19,000 base pairs in

length, is at the heart of the virion. This genome is encircled by

viral structural proteins, which join together to form the inner

ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex (16). The nucleoprotein (NP) and the

RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (L) are two key components of the RNP

complex. These proteins perform critical functions in viral

replication, ensuring that the virus can reproduce and propagate

inside the host cells (17). The

viral envelope, which is comprised of two viral glycoproteins, GP1

and GP2, surrounds the RNP complex. The glycoproteins interact with

host cell surface receptors, such as C-type lectin family

receptors, to enable attachment of the virus and membrane fusion

for subsequent entrance into cells (18). Knowledge of the Ebola virus

structure and replication cycle provides a foundation for the

development of prophylactic and therapeutic strategies. Notable

approved anti-Ebola vaccines include rVSV-ZEBOV-GP (ERVEBO),

Ad5-EBOV and rVSV/Ad5, all expressing the ebolavirus glycoprotein

as the immune system-stimulating antigen (19-21).

Treatment strategies encompass various types, such as the

convalescent serum of infected individuals, therapeutic

interferons, gene therapies such as small interfering RNAs that

target viral genes and lastly, inhibitors and monoclonal antibodies

(22). Inhibitors may target

various host machinery or viral enzymes crucial for the ebolavirus

life cycle; ion channel inhibitors target cell ion channels to

inhibit viral entry and viral entry inhibitors target host or viral

enzymes crucial for viral attachment, viral fusion and entry

(23). Moreover, monoclonal

antibodies have been approved for the treatment of EVD; Inmazeb and

the more recent Ebanga both target the ebolavirus glycoprotein,

thus inhibiting viral entry and attenuating viral spread across

host cells (24,25). Lastly, nucleotide analogues, such as

Remdesivir, become incorporated into nascent RNA molecules during

the viral RNA synthesis and thus interfere with viral replication

(26).

The threat of Ebola virus remains, as demonstrated

by the recurrent outbreaks even well into 2023, reaffirming the

need for safe and effective prophylactic measures and treatments.

Research on the Ebola virus is made challenging by the requirement

for austere safety measures in the laboratory setting, to prevent

accidental transmission of the pathogen (17). Furthermore, the drug development

process itself is a time-consuming and costly process from target

identification to lead development and optimization, with a

fraction of drugs under development finally making it to market

(27). Data abundance marks the

current state of scientific knowledge; a trove of structural,

genetic, chemical and molecular data is harnessed and is available

in public databases (28,29). Machine learning and deep learning

solutions, additionally, are being increasingly used in the context

of the drug development process (30). A risk prediction model for lymph

node metastasis in Ewing's sarcoma (ES) has been created using

clinicopathological data leading to the design of a clinical-use

service to improve detection of this metastasis in patients with ES

(31). Similarly, a model was

trained with medical data from patients with kidney cancer to aid

in the stratification for the risk of developing bone metastasis

and inform personalized treatment decisions (32).

Emerging technologies, such as semantic analysis or

neural networks can be employed in tasks such as target

identification or drug development against single-stranded RNA

viruses (28). The use of

computational methods has the potential to accelerate the

preclinical drug development of novel antivirals, reducing costs

and removing the need for biosafety measures. The present study

describes a computational pipeline for the generation of new

molecules targeting the Ebola virus polymerase, employing neural

network architectures, chemical data and structural bioinformatics.

The use of public big data of existing anti-virals enables the

training of models on critical features of anti-viral agents, which

in turns informs the design of novel candidates by the neural

network. The in silico assessment of the neural network

designed ligands by computational bioinformatics and the design of

pharmacophores further compresses these features and creates a

profile of antiviral potential, capable of informing further

experiments. The flexibility and scalability of the pipeline

components enhances and accelerates research on the preclinical

stage, where scale and safety are all the more relevant when faced

with the challenge of viral epidemics and pandemics.

Data and methods

Construction of pipeline

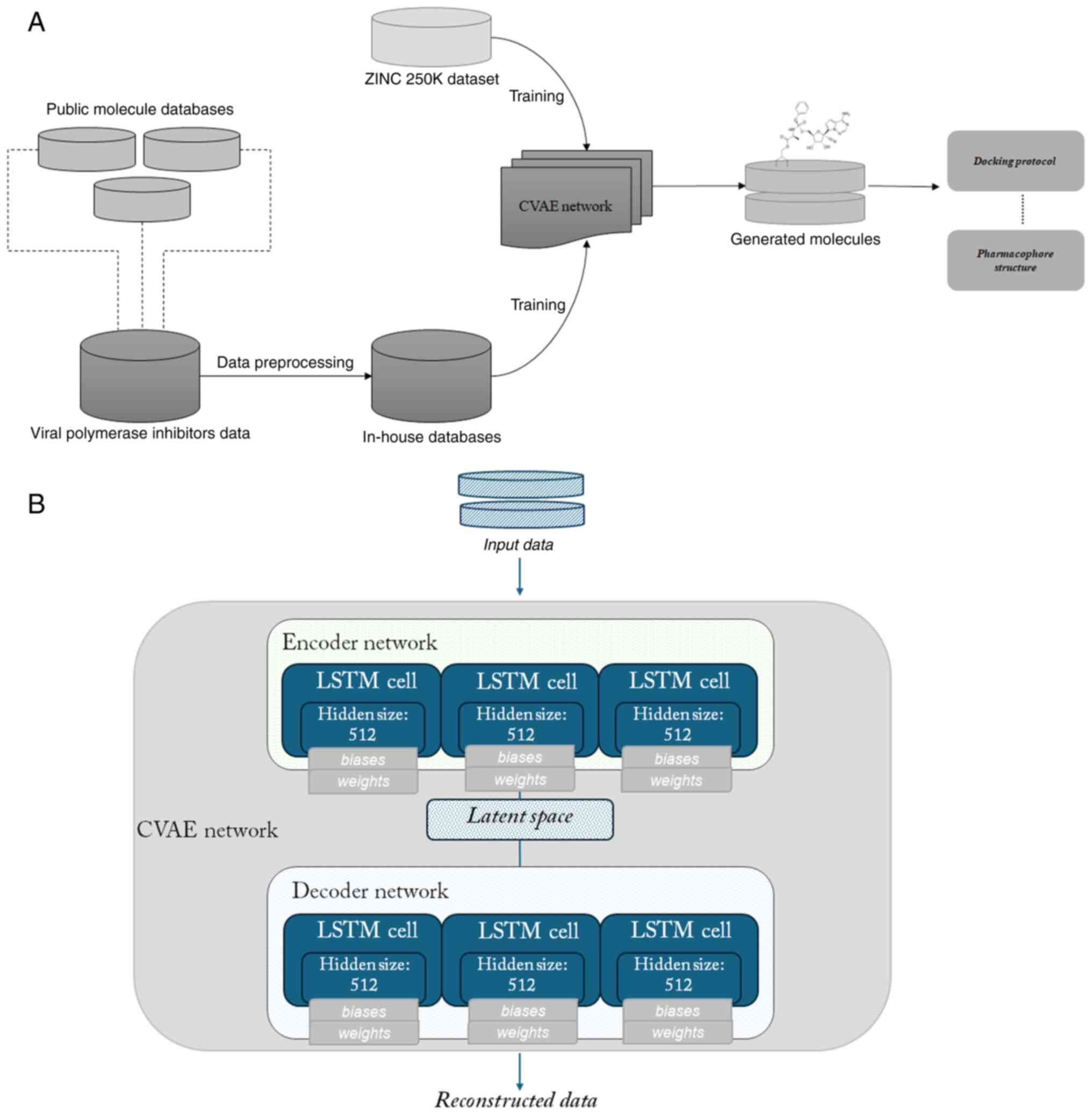

The overview of the pipeline is summarized in

Fig. 1A and is as follows: Public

chemical databases were employed towards building an in-house

chemical database of existing compounds which target viral

polymerases. A neural network was designed and trained on the

in-house database to learn the underlying features and

distribution. Subsequently, the latent space defined by the network

was explored to generate new molecules with a set of desired

properties. The resulting novel ligands were further filtered and a

conformational search was subsequently carried out to generate

three-dimensional conformations of the molecules, in preparation

for a docking simulation. A high throughput screening protocol was

used to dock the ligands against the previously experimentally

determined, three-dimensional structure of the Ebola virus

polymerase-VP35 complex, and lead performing ligands served as the

basis for pharmacophore construction.

Creation of in-house chemical database

and data pre-processing

In the era of big data and high-throughput

processes, vast amounts of chemical data are available in openly

accessible databases. ChEMBL constitutes a widely-known, public

database of curated chemicals, containing more than two million

preclinical drugs with associated bioactivities, ~14,000 clinical

candidate drugs and >4,000 clinical drugs (33). Its sister database, SureChEMBL,

aggregates similar data (34). The

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) Drug database

collects drug data across three different continents in a

systematic manner (35). The Virus

Pathogen Database and Analysis Resource (ViPR) hosts multi-omics

data regarding various viral families, combining data from

archives, as well as data submitted by scientific groups and

virologists, rendering it a valuable source of information

(36). PubChem, supported by the

National Library of Medicine of NIH, constitutes a principal

information source for medicinal chemistry and drug discovery, with

substance, compound and bioassay records available along with

various metadata (37).

Modules were built in Python to use the Application

Programming Interface (API) of ChEMBL, PubChem, KEGG and SureChEMBL

to collect data of compounds which target viral polymerases. The

selection of the data sources was steered by a set of defined

criteria, such as the scope and coverage of the data, the public of

private nature of the datasets, the format of the data, as well the

availability of an API to enable the efficient sourcing. The

chemical data were collected in simplified molecular input line

entry system (SMILES) format. SMILES is used to convert the

three-dimensional structure of a chemical's into a string of

symbols that can be used as input in neural network training tasks

or other bioinformatic analyses (38). In the case of ViPR, where the API

availability is not straightforward, the collection of compounds

was executed in a semi-manual manner. The ChEMBL Python module, for

instance, queries the ChEMBL molecule endpoint against a set of

ChEMBL target identifiers of interest (such as the influenza

polymerase, CHEMBL4523676) to collect compounds against that

target, along with metadata such as compound preferred names, max

phase, molecular formula, molecular weight and the canonical SMILES

string. The module can be found in the following repository:

https://github.com/IoDiakou/Automatic-collection-of-drugs-for-specific-target-from-ChEMBL.

Analogous modules were constructed for all the aforementioned

databases and the collections of compounds queried from each

database were finally collected into an in-house SQLite database of

viral inhibitors. SQLite offers flexible and scalable storage,

which enables the preprocessing and handling of the data (39).

Upon establishing the database, preprocessing was

carried out using the Python RDKit interface, which allows the easy

manipulation and transformation of chemical strings (40). Functions were used to filter noisy

compounds out of the in-house database; examples include mixtures,

non-organic salts, organometallic compounds, polymers. Considerably

lengthy molecules were also filtered out, as lengthy strings which

exceed a threshold of ~120 characters can hinder deep learning and

cheminformatics tasks. Furthermore, to handle the existence of

duplicate records, as a direct result of sourcing inhibitors from

public databases where overlap may occur, a deduplication step was

also carried out. Lastly, molecular properties of interest were

calculated for each entry of the filtered and deduplicated

compounds database.

Neural network architecture design and

training

Generative probabilistic models based on neural

networks have gained traction over the past decade, with generative

adversarial nets and variational autoencoders (VAEs) as two

prominent examples, being applied to various tasks (41). The neural network learns a

distribution p(x) across data points and allows sampling, thus

carrying out the generative portion (42). The architecture used herein is a

subtype of VAE, termed a conditional variational autoencoder

(CVAE); the model samples from the generative distribution upon a

set condition, to generate novel data points and simultaneously

predict properties. All data handling and machine learning tasks

were carried out using Python; the neural network model design and

deployment was carried out using the TensorFlow framework, which

offers scalability and reliability for machine-learning tasks

(43). The VAE consists of two

units, the encoder, which maps input data points to a distribution

over the low-dimensional, latent space, and the decoder, which maps

the points of the aforementioned latent space back into the data

space. During training, the loss function implemented aims to

balance two objectives. The reconstruction loss reflects how well

the decoded data points match their original inputs and is

calculated by the mean squared error (44). The regularization part of the loss

function encourages the high similarity between the distribution

which the neural network learns, and an a priori distribution,

commonly a standard Gaussian distribution.

The encoder component of the network comprises of a

list of Long short-term memory (LSTM) cells, with each LSTM cell in

the list having a specific hidden size, and all LSTM cells are

wrapped into a multi-layered LSTM cell. An analogous structure of

LSTM cells is defined for the decoder. LSTMs belong to the umbrella

group of recurrent neural networks and constitute, one might say,

an evolution of them (45). A

schematic of the configuration and cell structure of the neural

network is presented in Fig. 1B.

The designed neural network was trained sequentially on the ZINC

250K dataset and then the in-house database of viral polymerase

inhibitors, to learn the representations and the characteristics

underlining these viral inhibitors. The ZINC database and

established subsets of it are commonly used in docking experiments

or other string-based chemical research approaches; the 250K subset

of the ZINC database has been used in Kaggle applications and other

autoencoder-related articles (46).

Generation and filtering of novel

molecules

Upon being fine-tuned on the dataset of existing

viral polymerase inhibitors, the CVAE was tasked with generating

novel molecules in SMILES format. The generation was steered

towards molecules which would exhibit the properties within the

‘neighborhood’ of an established small-molecule viral polymerase

inhibitor. Both the training and the sampling stage were carried

out in VS Code, using a system comprising of a quad-core Intel Core

i7-3770 processor and an NVIDIA GeForce GXT 1650 architecture for

GPU acceleration, which is crucial for machine-learning tasks.

The dataset of generated molecules was stored in a

new SQLite table instance for the subsequent pipeline steps of

re-filtering and docking experiments. RDKit functions and SMARTS

patterns were used to flag compounds with high similarity to the

starting in-house dataset, or with low likelihood of being

synthesized or proceeding further during a conventional hit

identification stage, such as fully acyclic compounds.

Docking and pharmacophore

generation

To investigate the potential efficacy of the novel

molecules as inhibitors for the Ebola polymerase, docking

experiments were carried out in molecular operating environment

(MOE); docking is a popular technique in computational drug

discovery for the study of ligand-target interactions (47). To transition from the generated

molecules, which are in a 2-dimensional flat string format, to a

three-dimensional molecule, conformational search protocols were

carried out. The complex of EBOV polymerase and cofactor VP35 with

suramin (PDB id: 7YET) served as the docking structure, following

structure preparation steps of assigning formal charges, energy

minimization and extraction of the suramin molecule in complex. The

complexed suramin additionally served as a baseline for the binding

site region as well as for interactions with surrounding residues

and binding affinities. High-throughput screening constitutes a

robust protocol for the rapid assay of candidate compounds,

allowing for the time and computational resource-efficient

evaluation of large sets of chemical data against a target

(48). Pharmacophore modeling was

carried out on the generated molecules with optimal binding scores

and interactions; pharmacophores can serve as a framework for

virtual screening efforts, allowing the identification of motifs

and interactions of interest underlying activity (49).

Results

Construction of in-house chemical

database

In the stage of database creation, API queries were

built against public databases, such as PubChem and ViPR, for the

search and retrieval of information related to molecules with

inhibitory activity against viral polymerases. Prior to filtering,

the in-house database of compounds contained 12,369 molecules;

following deduplication and removing out-of-scope molecules, such

as mixtures, non-organic salts and molecules >120 characters,

the database contained 11,960 unique molecule entries. For each

SMILES molecule, relevant molecular properties were calculated,

namely molecular weight, logP and topological polar surface area

(TPSA), serving as additional descriptors and features for the

training of the machine-learning model. The TPSA represents the

total of the contributions to the molecule (typically van der

Waals) surface area of polar atoms, e.g., nitrogen, oxygen or

associated hydrogens (50). It

constitutes a popular molecular descriptor for tasks of evaluating

transport ability, penetrative ability (such as through the

blood-brain barrier) and absorption within the intestine (50).

Neural network training

The SMILES input molecular data are one-hot encoded

into their vector embedding, within the first layers of the

encoding unit, along with the corresponding molecular properties

previously calculated for each data entry. The latent

representation is created in the encoder unit and subsequently

serves as input for the decoder unit; the decoded vector generated

by the decoder unit is funneled through a transformative layer of

equal size to the original one-hot encoding vector of the encoding

unit, to ensure the faithful reconstruction of the input. Softmax

activation is applied to the vectors. To set the basis for the

faithful reconstruction of encoded SMILES, the neural network was

first trained for 10 epochs on the ZINC 250K dataset, using Adam as

the optimizer, while also implementing an early-stopping criterion.

Subsequently, the model was fine-tuned on the in-house database of

existing inhibitors using ten-fold augmentation, to prepare for the

generative step of the pipeline.

Novel molecule generation, docking and

pharmacophore design

The latent space constructed between the encoder and

decoder unit served as the chemical space for the generation of

novel molecules. The latent space was sampled for the generation of

1,400 novel molecules along with prediction of molecular properties

for the generated molecules, resulting in sets of SMILES,

properties. SMARTS patterns were employed, post-deduplication, for

the removal of invalid SMILES strings from the resulting dataset.

As a last step the generated molecules were evaluated for

sufficient dissimilarity against the existing inhibitors within our

in-house database, which served as the fine-tuning set.

To investigate the binding behavior and interactions

between the generated molecules and the target of interest, herein

the ebolavirus polymerase, the structure of the ebolavirus

polymerase complex was first prepared in MOE in anticipation of the

docking experiments. The employed structure consists of the Ebola

virus L polymerase complexed with the co-factor VP35, an accessory

protein that is an essential part of the replication unit, with

supplementary roles as an antagonist of the host immune response

and virulence factor (51). VP35,

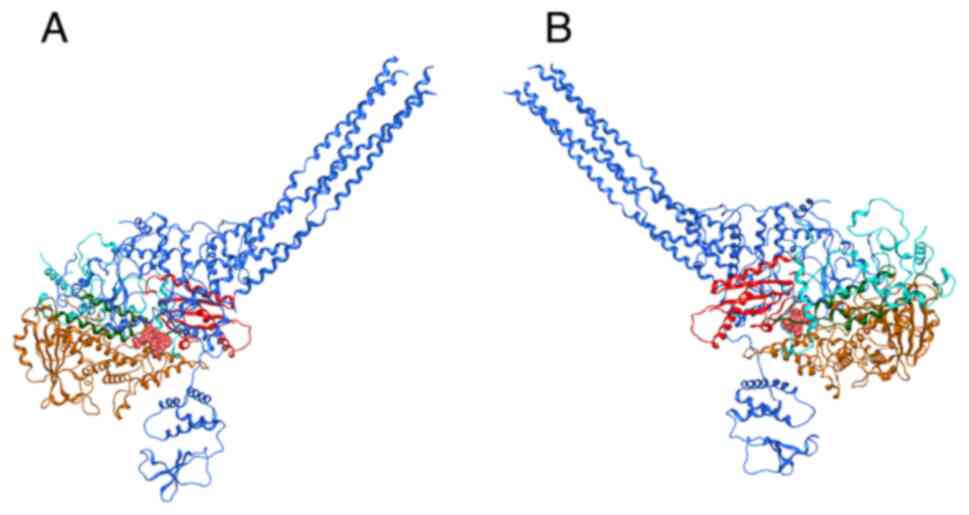

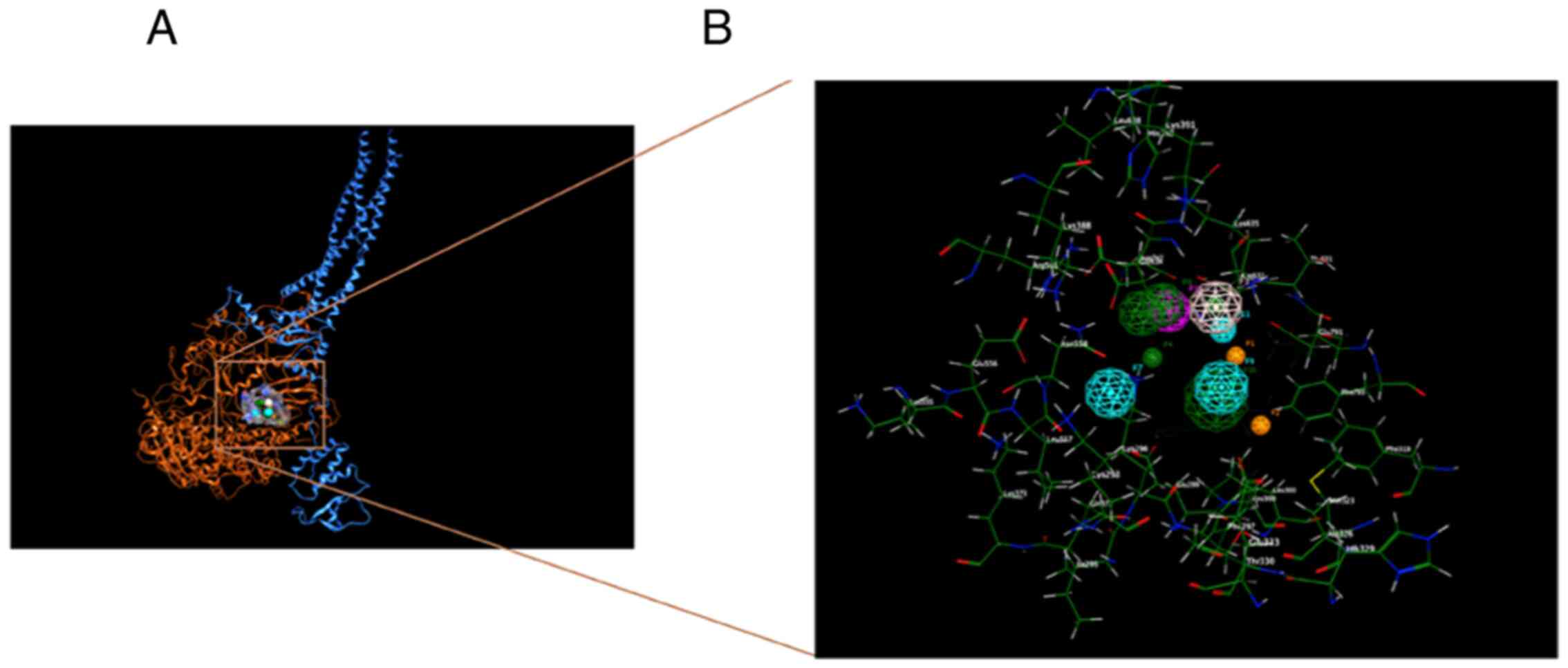

which is illustrated by the dark blue ribbon formation in Fig. 2A, interacts with the Ebola virus L

protein (Fig. 2A with red, yellow

and cyan ribbons for the different polymerase domains) to form the

replication complex for the generation of viral genome strands

during the viral cycle. In the employed three-dimensional structure

(PDB ID: 7YET), suramin is additionally bound to the complex

(52) (Fig. 2 in pink sphere representation to

denote the span of its molecular surface).

The generated molecules underwent a protocol of

conformational search within MOE to build a library of

three-dimensional conformations, which are crucial for the

exploration of the structural space of the binding site during the

docking experiments. Detailed conformational search cycles were

performed, with 100 iterations threshold per molecule for each

conformation, and a set of ten conformations per molecule within

the dataset. The suramin molecule which is bound to the active site

of the Ebola virus L-VP35 complex served as a guideline for the

identification of the site for docking, using dummy atoms to define

the site and the receptor and solvent as the receptor parameter.

The ligand database containing the conformations of the novel

molecules was then docked against the site (53).

The docking results were collected in a MOE

molecular database (mdb) file for further analysis, which

encompassed the evaluation of the results on multiple levels. The

docking scores and position of suramin within the site, upon using

the same docking protocol and parameters, served as a baseline for

the comparison of the scoring results of the novel molecules as

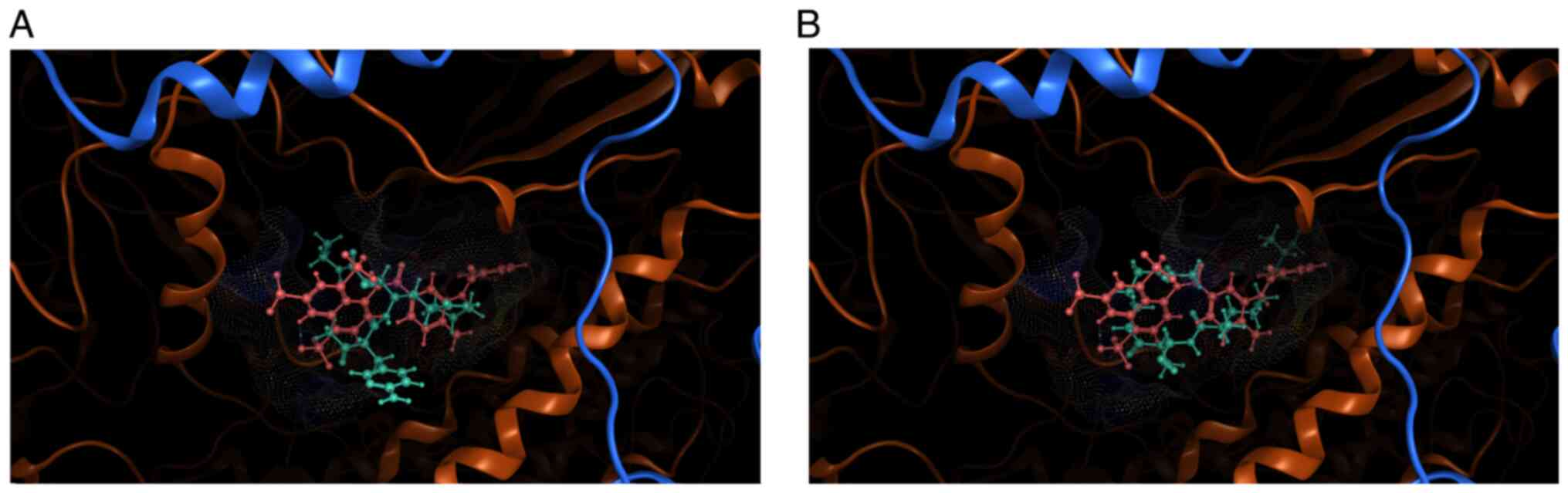

well as for visual comparisons. Examples of docking positions of

the novel molecules are illustrated in Fig. 3, with the positioning of suramin

(pale pink coloring) for visual comparison. Energy minimization was

additionally carried out to optimize the poses, monitoring the

shift in the positioning of the docked conformer. This is

exemplified in Fig. 3, where the

positioning of the ligand (light blue) relative to the binding

pocket and position of suramin (in pale pink) has shifted following

energy minimization cycles.

Furthermore, the ligand interaction functionality

within MOE allowed the examination of the specific interactions

between the atoms of the molecules and crucial residues around the

binding site of the viral polymerase. Conformational and spatial

characteristics, such as steric hindrances, were also taken into

account during the analysis of the docking results; structural

characteristics, such as the absence or presence of highly cyclic

groups, can serve as additional indicators of the molecules'

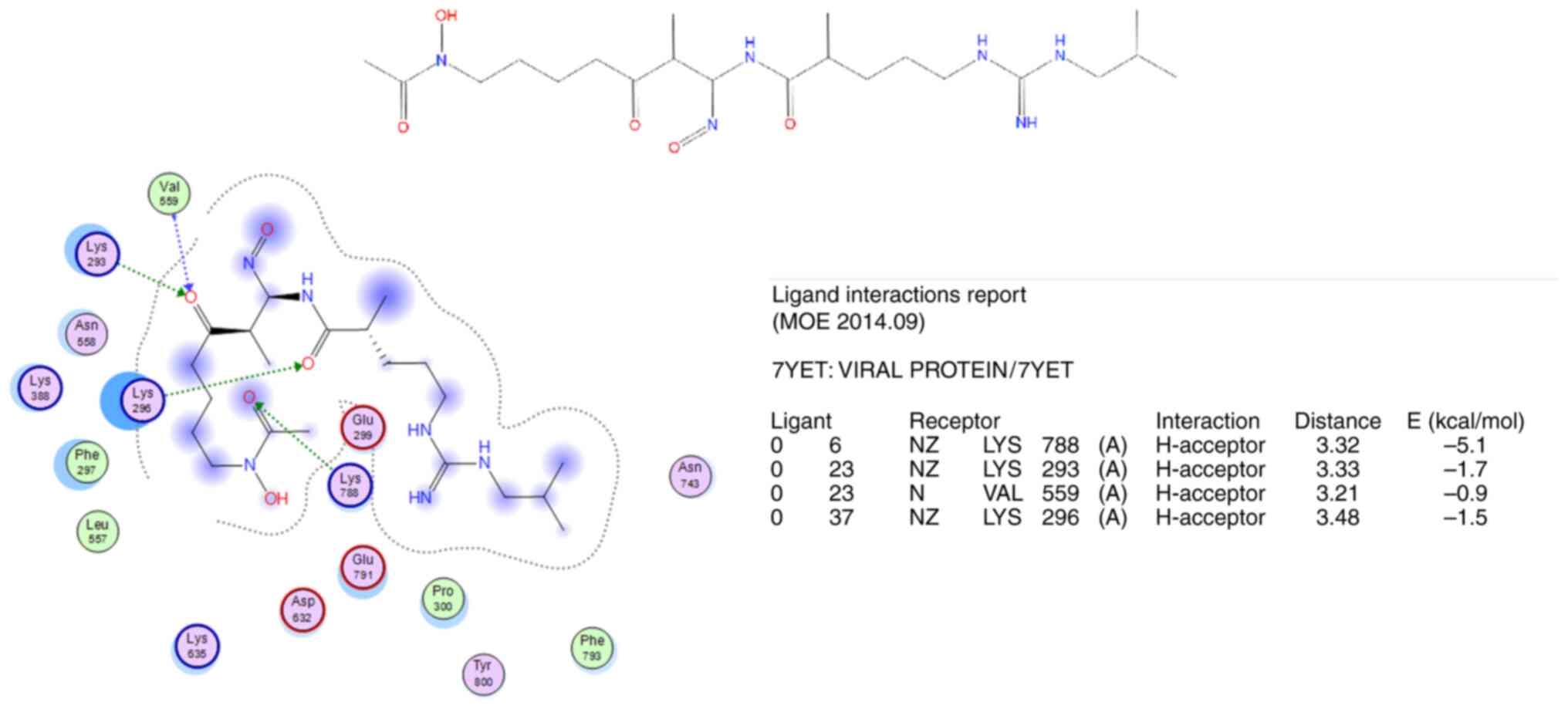

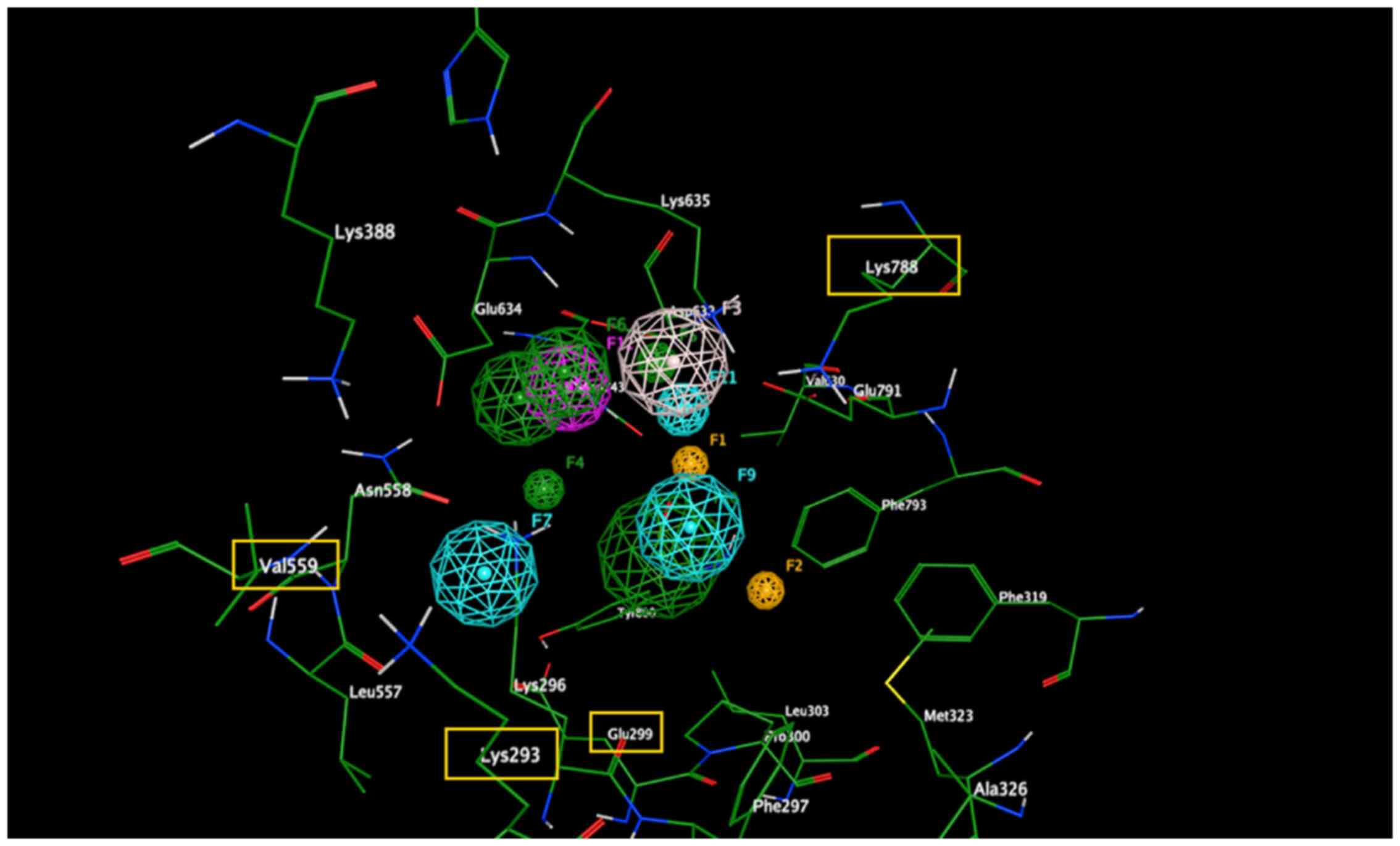

nature, such as their potential toxicity. Fig. 4 depicts this type of interactions

information for the same docked molecule as in Fig. 3, termed mol_2 for brevity.

The interaction diagram illustrated in Fig. 4, on the bottom left panel, confirms

that mol_2, for instance, forms several hydrogen bonds with the

receptor ebolavirus protein complex. Key residues involved in these

interactions are Lys 788, Lys 293, Val 559 and Lys 296. The

hydrogen bonds, indicated by green dashed lines, suggest that these

interactions are key for stabilizing the ligand-receptor complex.

The interaction table provides quantitative details, with

interaction energies ranging from -0.9 to -5.1 kcal/mol. These

values indicate the strength of the hydrogen bonds, with the

interaction between mol_2 atom O6 and EBOV polymerase Lys 788 being

the most significant due to its lowest energy (-5.1 kcal/mol). The

distances of these interactions (around 3.2-3.5 Å) are typical for

hydrogen bonds, further validating the strength and specificity of

these interactions. Top performing molecules as identified during

this evaluation process were further optimized with molecular

dynamics simulations without restraints, monitoring their shifts in

positions as in the example of Fig.

3. Lastly, pharmacophore modeling was carried out via the

pharmacophore building utility of MOE, calculating consensus

features from the bound ligands wherever meaningful.

To carry out the union of consensus pharmacophores

generated by different schemes, for each scheme, the individual

pharmacophores were first generated per ligand member among the top

100 scoring docked ligands. The R-strength value was enabled, and

each feature was adjusted with an appropriate assignment of

weights, after assessing its importance in the set of overall

interactions between the ligand and the receptor residues.

Pharmacophore data were saved in the pharmacophore format of MOE,

to be subsequently used to build the consensus pharmacophore for

the scheme by combining the individual pharmacophore features from

all ligands. As illustrated in Figs.

5 and 6, the unified

pharmacophore features span the pocket defined by the docking site,

reflecting interactions between the novel ligands and key residues

of the viral enzyme. Overall, the binding site environment is

comprised of a mix of hydrophobic and polar/charged residues. This

diverse environment supports a range of interactions, from

hydrophobic and aromatic interactions to hydrogen bonding and ionic

interactions. Key residues of the receptor harboring potential

interactions with features of the ligand are highlighted in yellow

boxes in depicted Fig. 6, colored

dark green and in stick figure representation as captured in MOE.

Notably, Lys393, Glu398, Val583, Glu394 and Glu399 are highlighted,

as these are key residues for binding interactions, highlighted by

the analyzed interactions of suramin as well. Aromatic

interactions, as highlighted in the generated pharmacophores, play

a pivotal role in the ligand binding, particularly through π-π

stacking interactions.

The unified pharmacophore reflects a comprehensive

interaction profile, capable of forming multiple types of

interactions within the receptor binding site, spanning aromatic,

hydrophobic, hydrogen bonding and potential metal ion coordination

interactions. Furthermore, this rich set of binding and chemical

feature information can be employed in the subsequent design or

screening of candidates against the specific target, employing the

availed pharmacophoric features as quick guidelines for the design,

screening or optimization of compounds and leads. Within the

context of the pipeline described herein, the data which were

collected during the docking and pharmacophore step of the pipeline

were fed back into the SQLite database, linked as metadata to the

SMILES molecules and further enhancing the knowledgebase.

Discussion

The pipeline described herein constitutes a scalable

approach for the discovery of novel potentially active anti-Ebola

agents, harnessing the rapidly increasing power of machine learning

capabilities and publicly accessible chemical data. Integral

processes of the drug design challenge, such as the hit

identification and lead optimization, can be supported by

state-of-the-art computational methods, which have the potential of

bringing vetted candidate molecules to the preclinical and

laboratory stage, effectively reducing operational costs and time,

both of which are crucial in the drug development cycle. This is

all the more relevant when the target of interest is a virus,

which, as exhibited by the recent COVID-19 epidemic, can grow into

a global issue rapidly. Through the implementation of rapid and

effective computational pipelines which combine string-based

formats of drugs and active compounds, with the power of robust

neural networks, a shift can be supported towards the adoption of a

proactive stance in the development of safe and effective

anti-virals.

Such a pipeline is marked by key features of

scalability and repurposing. The training dataset and the target of

interest are vessels, able to adopt different identities, depending

on the task at hand. What is described herein as the design and

evaluation of candidate, novel polymerase inhibitors targeting the

EBOV polymerase can be efficiently translated into the generation

of novel immunosuppressants in the context of Lupus, for instance,

or the generation of novel inhibitors against a metabolic enzyme

implicated in metabolic disorders. Furthermore, the neural network

architecture itself constitutes a flexible parameter of great

impact; tuning different parameters such as the network cell of

choice or the optimization algorithm can in turn yield different

generative behaviors, rendering the generation of novel data

points, or molecules, more or less restrictive or more or less

imaginative. One must note that there are inherent challenges in

using SMILES as a representation of chemical information for the

design and deployment of deep neural networks, including limited

ability to reflect stereochemistry and challenges in encoding and

interpreting complex molecules. Canonical SMILES can be employed to

address the aspect of ambiguity, while the combination of SMILES

with state-of-the-art tokenization techniques may enhance

performance (54).

Processes similar to the framework described herein,

such as the one proposed by van Tilborg and Grisoni (55), incorporate novel data acquisition to

perform iterative model improvement, parallel to the model's

execution of the task, which, in the study by van Tilborg and

Grisoni (55), is hit detection

through screening. Despite not incorporating this factor of ‘active

learning’, the proposed framework leverages the size and complexity

of the training data of anti-virals that have been designed and

assessed by the scientific and biomedical community, often in the

lab setting. This allows the model to learn features from

real-world examples, a ground truth of chemical information that

leads to precise, multifaceted, in-depth learning and subsequent

design of novel ligands. In summary, the proposed framework

reflects the significant potential which exists in the application

of machine-learning approaches in the field of computational drug

design. Leveraging big data and state-of-the-art algorithms

supports the effort of developing effective therapeutic agents,

under the scope of precision medicine and a proactive stance

against emerging viral threats.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author. The employed programming

code and datasets can be accessed in the first author's repository,

in the following web link: https://github.com/IoDiakou/anti-ebola-drugs-vae.

Authors' contributions

ID, GPC, DV and EE were involved in the design and

conceptualization of the study. ID, GPC, DV and EE contributed to

the collection and analysis of the data, as well as the design and

implementation of the pipeline described herein. ID, GPC, DV and EE

were involved in the writing and editing of the manuscript and in

the generation of relevant figures. ID, DV and EE confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. All authors have read and

approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

GPC is the Editor in Chief of the journal, and DV

and EE are Editors of the journal. However, they had no personal

involvement in the reviewing process, or any influence in terms of

adjudicating on the final decision, for this article. ID declares

that she has no competing interests.

References

|

1

|

Clegg J and Lloyd G: Ebola haemorrhagic

fever in Zaire, 1995. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 8:225–228. 1995.

|

|

2

|

Muyembe-Tamfum JJ, Mulangu S, Masumu J,

Kayembe JM, Kemp A and Paweska JT: Ebola virus outbreaks in Africa:

Past and present. Onderstepoort J Vet Res. 79(451)2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Zheng H, Yin C, Hoang T, He RL, Yang J and

Yau SS: Ebolavirus classification based on natural vectors. DNA

Cell Biol. 34:418–428. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Ajelli M, Merler S, Fumanelli L, Pastore

Y, Piontti A, Dean NE, Longini IM Jr, Halloran ME and Vespignani A:

Spatiotemporal dynamics of the Ebola epidemic in Guinea and

implications for vaccination and disease elimination: A

computational modeling analysis. BMC Med. 14(130)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Branda F, Mahal A, Maruotti A, Pierini M

and Mazzoli S: The challenges of open data for future epidemic

preparedness: The experience of the 2022 Ebolavirus outbreak in

Uganda. Front Pharmacol. 14(1101894)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Kucharski AJ and Edmunds WJ: Case fatality

rate for Ebola virus disease in west Africa. Lancet.

384(1260)2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Gostin LO and Friedman EA: A retrospective

and prospective analysis of the west African Ebola virus disease

epidemic: Robust national health systems at the foundation and an

empowered WHO at the apex. Lancet. 385:1902–1909. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Brolin Ribacke KJ, Saulnier DD, Eriksson A

and von Schreeb J: Effects of the West Africa ebola virus disease

on health-care utilization - A systematic review. Front Public

Health. 4(422)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Marí Saéz A, Weiss S, Nowak K, Lapeyre V,

Zimmermann F, Düx A, Kühl HS, Kaba M, Regnaut S, Merkel K, et al:

Investigating the zoonotic origin of the West African Ebola

epidemic. EMBO Mol Med. 7:17–23. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Plowright RK, Parrish CR, McCallum H,

Hudson PJ, Ko AI, Graham AL and Lloyd-Smith JO: Pathways to

zoonotic spillover. Nat Rev Microbiol. 15:502–510. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Koch LK, Cunze S, Kochmann J and Klimpel

S: Bats as putative Zaire ebolavirus reservoir hosts and their

habitat suitability in Africa. Sci Rep. 10(14268)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Osterholm MT, Moore KA, Kelley NS,

Brosseau LM, Wong G, Murphy FA, Peters CJ, LeDuc JW, Russell PK,

Van Herp M, et al: Transmission of ebola viruses: What We know and

what we do not know. mBio. 6(e00137)2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Velásquez GE, Aibana O, Ling EJ, Diakite

I, Mooring EQ and Murray MB: Time from infection to disease and

infectiousness for ebola virus disease, a systematic review. Clin

Infect Dis. 61:1135–1140. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Bettini A, Lapa D and Garbuglia AR:

Diagnostics of ebola virus. Front Public Health.

11(1123024)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Verbeek JH, Rajamaki B, Ijaz S, Sauni R,

Toomey E, Blackwood B, Tikka C, Ruotsalainen JH and Kilinc Balci

FS: Personal protective equipment for preventing highly infectious

diseases due to exposure to contaminated body fluids in healthcare

staff. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 4(CD011621)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Ghosh S, Saha A, Samanta S and Saha RP:

Genome structure and genetic diversity in the Ebola virus. Curr

Opin Pharmacol. 60:83–90. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Judson S, Prescott J and Munster V:

Understanding ebola virus transmission. Viruses. 7:511–521.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Nanbo A, Imai M, Watanabe S, Noda T,

Takahashi K, Neumann G, Halfmann P and Kawaoka Y: Ebolavirus is

internalized into host cells via macropinocytosis in a viral

glycoprotein-dependent manner. PLoS Pathog.

6(e1001121)2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Wolf J, Jannat R, Dubey S, Troth S,

Onorato MT, Coller BA, Hanson ME and Simon JK: Development of

pandemic vaccines: ERVEBO case study. Vaccines (Basel).

9(190)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Dolzhikova IV, Zubkova OV, Tukhvatulin AI,

Dzharullaeva AS, Tukhvatulina NM, Shcheblyakov DV, Shmarov MM,

Tokarskaya EA, Simakova YV, Egorova DA, et al: Safety and

immunogenicity of GamEvac-Combi, a heterologous VSV- and

Ad5-vectored Ebola vaccine: An open phase I/II trial in healthy

adults in Russia. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 13:613–620.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Li Y, Wang L, Zhu T, Wu S, Feng L, Cheng

P, Liu J and Wang J: Establishing China's national standard for the

recombinant adenovirus type 5 vector-based ebola vaccine (Ad5-EBOV)

virus titer. Hum Gene Ther Clin Dev. 29:226–232. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Malik S and Waheed Y: Tracing down the

updates on Ebola virus surges: An update on anti-ebola therapeutic

strategies. J Transl Int Med. 11:216–225. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Lee JS, Adhikari NKJ, Kwon HY, Teo K,

Siemieniuk R, Lamontagne F, Chan A, Mishra S, Murthy S, Kiiza P, et

al: Anti-Ebola therapy for patients with Ebola virus disease: A

systematic review. BMC Infect Dis. 19(376)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Taki E, Ghanavati R, Navidifar T, Dashtbin

S, Heidary M and Moghadamnia M: Ebanga™: The most recent

FDA-approved drug for treating Ebola. Front Pharmacol.

14(1083429)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Saxena D, Kaul G, Dasgupta A and Chopra S:

Atoltivimab/maftivimab/odesivimab (Inmazeb) combination to treat

infection caused by Zaire ebolavirus. Drugs Today (Barc).

57:483–490. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Tchesnokov EP, Feng JY, Porter DP and

Götte M: Mechanism of inhibition of Ebola virus RNA-Dependent RNA

polymerase by remdesivir. Viruses. 11(326)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Sun D, Gao W, Hu H and Zhou S: Why 90% of

clinical drug development fails and how to improve it? Acta Pharm

Sin B. 12:3049–3062. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Vlachakis D: Genetic and structural

analyses of ssRNA viruses pave the way for the discovery of novel

antiviral pharmacological targets. Mol Omics. 17:357–364.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Papageorgiou L, Loukatou S, Sofia K,

Maroulis D and Vlachakis D: An updated evolutionary study of

Flaviviridae NS3 helicase and NS5 RNA-dependent RNA polymerase

reveals novel invariable motifs as potential pharmacological

targets. Mol Biosyst. 12:2080–2093. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Dara S, Dhamercherla S, Jadav SS, Babu CM

and Ahsan MJ: Machine learning in drug discovery: A review. Artif

Intell Rev. 55:1947–1999. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Li W, Zhou Q, Liu W, Xu C, Tang ZR, Dong

S, Wang H, Li W, Zhang K, Li R, et al: A machine learning-based

predictive model for predicting lymph node metastasis in patients

with ewing's sarcoma. Front Med (Lausanne).

9(832108)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Dong S, Yang H, Tang ZR, Ke Y, Wang H, Li

W and Tian K: Development and Validation of a predictive model to

evaluate the risk of bone metastasis in kidney cancer. Front Oncol.

11(731905)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Davies M, Nowotka M, Papadatos G, Dedman

N, Gaulton A, Atkinson F, Bellis L and Overington JP: ChEMBL web

services: Streamlining access to drug discovery data and utilities.

Nucleic Acids Res. 43:W612–W620. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Papadatos G, Davies M, Dedman N, Chambers

J, Gaulton A, Siddle J, Koks R, Irvine SA, Pettersson J, Goncharoff

N, et al: SureChEMBL: A large-scale, chemically annotated patent

document database. Nucleic Acids Res. 44:D1220–D1228.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Kanehisa M and Goto S: KEGG: Kyoto

encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 28:27–30.

2000.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Pickett BE, Sadat EL, Zhang Y, Noronha JM,

Squires RB, Hunt V, Liu M, Kumar S, Zaremba S, Gu Z, et al: ViPR:

An open bioinformatics database and analysis resource for virology

research. Nucleic Acids Res. 40:D593–D598. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Kim S, Chen J, Cheng T, Gindulyte A, He J,

He S, Li Q, Shoemaker BA, Thiessen PA, Yu B, et al: PubChem in

2021: New data content and improved web interfaces. Nucleic Acids

Res. 49:D1388–D1395. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Polanski J and Gasteiger J: Computer

Representation of Chemical Compounds. Springer International

Publishing, pp1997-2039, 2017.

|

|

39

|

Silva Y, Almeida I and Queiroz M: SQL:

From Traditional Databases to Big Data. SIGCSE. 413–418. 2016.

|

|

40

|

Landrum G: RDKit. Open-Source

Cheminformatics Software. 2010. Available from: https://www.rdkit.org.

|

|

41

|

Goodfellow I, Pouget-Abadie J, Mirza M, Xu

B, Warde-Farley D, Ozair S, Courville A and Bengio Y: Generative

Adversarial Networks. Vol 27. Advances in Neural Information

Processing Systems, 2014.

|

|

42

|

Kingma DP and Welling M: An introduction

to variational autoencoders. ArXiv: Dec 11, 2019 (Epub ahead of

print).

|

|

43

|

Abadi M, Barham P, Chen J, Chen Z, Davis

A, Dean J, Devin M, Ghemawat S, Irving G, Isard M, et al:

TensorFlow: A system for large-scale machine learning. ArXiv: May

31, 2016 (Epub ahead of print).

|

|

44

|

Hodson TO: Root-Mean-Square Error (RMSE)

or Mean Absolute Error (MAE): When to use them or not.

Geoscientific Model Development. Vol 15. European Geosciences

Union, pp5481-5487, 2022.

|

|

45

|

DiPietro R and Hager G: Deep learning:

RNNs and LSTM. pp503-519, 2020.

|

|

46

|

Akhmetshin T, Lin A, Mazitov D, Ziaikin E,

Madzhidov T and Varnek A: HyFactor: Hydrogen-count labelled

graph-based defactorization Autoencoder. Comput Theor Chem: Dec 6,

2021 (Epub ahead of print).

|

|

47

|

Chemical Computing Group: Computer-Aided

Molecular Design. Molecular Operating Environment (MOE). 2024.

Available from: https://www.chemcomp.com/en/Products.htm.

|

|

48

|

Szymański P, Markowicz M and

Mikiciuk-Olasik E: Adaptation of high-throughput screening in drug

discovery-toxicological screening tests. Int J Mol Sci. 13:427–452.

2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Giordano D, Biancaniello C, Argenio MA and

Facchiano A: Drug design by pharmacophore and virtual screening

approach. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 15(646)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Prasanna S and Doerksen RJ: Topological

polar surface area: A useful descriptor in 2D-QSAR. Curr Med Chem.

16:21–41. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Leung DW, Prins KC, Basler CF and

Amarasinghe GK: Ebolavirus VP35 is a multifunctional virulence

factor. Virulence. 1:526–531. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Yuan B, Peng Q, Cheng J, Wang M, Zhong J,

Qi J, Gao GF and Shi Y: Structure of the Ebola virus polymerase

complex. Nature. 610:394–401. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Kalinowsky L, Weber J, Balasupramaniam S,

Baumann K and Proschak E: A diverse benchmark based on 3D matched

molecular pairs for validating scoring functions. ACS Omega.

3:5704–5714. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Leon M, Perezhohin Y, Peres F, Popovič A

and Castelli M: Comparing SMILES and SELFIES tokenization for

enhanced chemical language modeling. Sci Rep.

14(25016)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

van Tilborg D and Grisoni F: Traversing

chemical space with active deep learning for low-data drug

discovery. Nat Comput Sci. 4:786–796. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|