Introduction

In 2020, breast cancer in females emerged as the

global cancer burden, accounting for ~2.3 million newly diagnosed

cases, which constituted 11.7% of all reported cancer cases.

Worldwide, there were 685,000 deaths recorded due to breast cancer,

ranking breast cancer 5th as regards cancer-related mortality

globally (1). In 2020, in India,

there were a total of 179,790 reported cases of breast cancer and

this constituted 10% of all cancer cases in that year. In urban

India, breast cancer among females is the most common malignancy.

The National Program of Cancer Registries (NPCR) reported an annual

percentage change (APC) of 0.68% for cancers at all sites and an

APC of 2% for breast cancer during the 3-year period from

2011-2014(2).

The risk factors for breast cancer are old age, late

menopause, early menarche, obesity, smoking, alcohol, a family

history of the disease, hormone-replacement-therapy, the use of

oral contraceptives and nulliparity. A maternal age of >30 years

at the first live birth is associated with a higher risk and <20

years with a lower risk of developing the disease. The most common

genes involved are p53 and BRCA1; 85% of breast cancers are

sporadic, while 10-15% are hereditary. Luminal-A breast cancer

(estrogen receptor-positive, and progesterone receptor-positive and

Her2neu-negative) is most common type and is associated with the

optimal prognosis. Basal-triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) is

associated with outcomes and high chances of visceral metastasis

(3). Mutations of BRCA predispose

to hereditary breast and ovarian cancer syndrome (HBOC). HBOC

syndrome requires that all primary relatives are counseled and

tested for BRCA gene mutations (4).

The early diagnosis and prompt management of breast

cancer will eventually greatly reduce the morbidity and mortality.

Currently, the majority of cases are diagnosed using the following

techniques: Biopsy, mammography, magnetic resonance imaging,

ultrasonography, computerized tomography and positron emission

tomography (5).

Tissue gene biomarkers improve the diagnosis of

breast cancer to a great extent; however, their applications are

limited as sample collection is invasive, and there is a risk of

hemorrhage and the unpleasant nature of diagnostic procedures.

Thus, there is need for non-invasive marker or minimally-invasive

markers which are highly sensitive and specific, and which can be

used to detect early-stage breast cancer during screening, thus

aiding in diagnosis and prognosis (6).

MicroRNAs (miRNAs/miRs) are short oligonucleotides

(20-25 nucleotides in length), non-coding sequences. They regulate

the expression of post-transcriptional target genes negatively by

silencing mRNA translation and inducing mRNA degradation. miRNAs

contain complementary sequences with their respective target gene

promoter region and complementary sequences with mRNA transcript

coding sequences. The RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) is

present in mRNA transcripts both on the 3' and 5'untranslated

regions. miRNAs recruit RISC to complementary sites and regulates

the target gene expression (7). On

the target genes, the miRNAs have an increased control on

amplification and decreased control on its deletion. Oncosuppressor

miRNAs inhibit the genes which promote cell growth and onco-miRNAs

increase cell proliferation by downregulating tumor suppressor

genes and promoting apoptosis (8).

Of note, >1,200 miRNAs have been identified to be

strongly associated with breast cancer; however, not one has been

translated for use in clinical diagnostics due to a lack of

validation and quality assessment (9). Several studies have been performed to

assess the specificity and sensitivity of miRNAs as screening tools

for the detection of early-stage breast cancer (10,11).

miR-27a has been shown to be associated with tumor proliferation

and metastasis, and its expression is elevated in the circulation

in the presence of breast cancer, suggesting that it may serve as

an early detection marker (12,13).

miRNA-122 facilitates breast cancer metastasis by preparing fuel

utilization in the premetastatic niche and has been tested as a

screening biomarker for early-stage BC (14-16).

Higher circulating levels of miR-155 in patients with breast cancer

are attributed to its dysregulation of tumor suppressors and its

involvement in the crosstalk of genetic and epigenetic messages for

malignant transformations in BC (17,18).

With the research performed over the past two

decades on breast cancer, circulating miRNA levels in blood serve

as minimally invasive or non-invasive biomarkers (6). Recently, reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) was widely used in

detecting circulating miRNAs. It is a highly sensitive and requires

a minimal amount of RNA input (19). The present study aimed to

investigate the diagnostic role of circulating miRNAs (miR-27a,

-122 and 155) in detecting early-stage breast cancer and to compare

the assayed levels with those found in women with benign breast

tumors and healthy controls.

Materials and methods

Ethics approval and study

participants

Ethical clearance obtained from the Institutional

Ethics Committee (IEC) of All India Institute of Medical Sciences

(AIIMS), Bhubaneswar, India (IEC/AIIMS BBSR/PG Thesis/2021-22/32).

After obtaining written informed consent, blood samples were

collected from the study participants (from August, 2021 to March,

2023). The study was conducted on individuals visiting the Surgery

or Onco-Surgery Outpatient Department in our tertiary care

hospital, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Bhubaneswar,

India. All patients resided in Eastern India, namely from the

states of Odisha and West Bengal. They were all of South Asian

Pacific ethnicity. The participants were classified into three

groups as follows: Group 1, included cases with early-stage breast

cancer; group 2, included cases with benign breast tumors; and

group 3, included healthy age-matched females with no breast lumps

or any other tumor or comorbidities.

The study sample size was calculated on the basis of

the results of the study by Swellam et al (13), in which the presence of the miRNA

marker was in 90% of the cases and in 10% of the controls. With an

α error of 0.05 and 80%, the sample size calculated was 56 in each

group, namely 56 healthy controls, 56 benign breast tumor cases and

56 early-stage breast cancer cases that had stage I, stage IIa and

stage IIb disease.

According to the study design, the inclusion

criteria were women within the age group of 20-60 years, women who

had early-stage breast-cancer or benign breast tumors, confirmed by

a FNAC/biopsy report, who had not received any intervention and had

not reported any other malignancies. Blood samples were collected

from all participants in the study from August, 2021 to March, 2023

and serum was separated. A total of 1 ml serum was used for

biochemical analyses (liver and kidney function tests) on the AU

5800 auto analyzer (Beckman Coulter, Inc.), using reagents provided

by the same vendor. Another 1 ml serum was stored in RNase free

aliquots at -80˚C till the extraction of RNA was performed.

miRNA extraction

miRNA was extracted from the serum samples using the

miRNeasy Serum/Plasma kit (cat. no. 217184, Qiagen, Inc.),

according to manufacturer's instructions; all procedures were

performed in RNase free conditions. Finally, elution with 14 µl

RNase-free water resulted into a 12-µl eluate. The purity of the

extracted miRNAs was detected using a Nanodrop spectrophotometer

(Nano Bio-analytical Technologies Limited).

First-strand cDNA synthesis

This protocol involves the conversion of total miRNA

into cDNA by reverse transcription. First-strand cDNA synthesis

reactions were carried out using the miRCURY LNA miRNA PCR Starter

kit (cat. no. 339320, Qiagen, Inc.) and miRCURY LNA RT kit (cat.

no. 339340, Qiagen, Inc.). First the volume of template RNA was

calculated using the following formula: [Template RNA (µl)=elution

volume (µl)/original sample volume (µl)x16 (µl)]. Thus, for a 12-µl

elution volume and a 100-µl original sample volume, the template

RNA volume was 1.92 µl. As recommended in the manufacturer's

instructions, the total volume of 10 µl reverse transcription

reaction components were as follows: 2 µl 5X miRCURY

SYBR®-Green RT Reaction Buffer, 1 µl 10X miRCURY RT

Enzyme Mix, 0.5 µl UniSp6 RNA spike-in, 1.92 µl template miRNA and

4.58 µl RNase-free water. PCR tubes with the 10-µl total reaction

volume were placed in thermal cycler (Eppendorf) and incubated for

60 min at 42˚C for the reverse transcription step, for 5 min at

95˚C to inactivate reverse transcriptase and finally cooled to 4˚C

immediately. PCR tubes were stored at 4˚C until quantitative PCR

was performed.

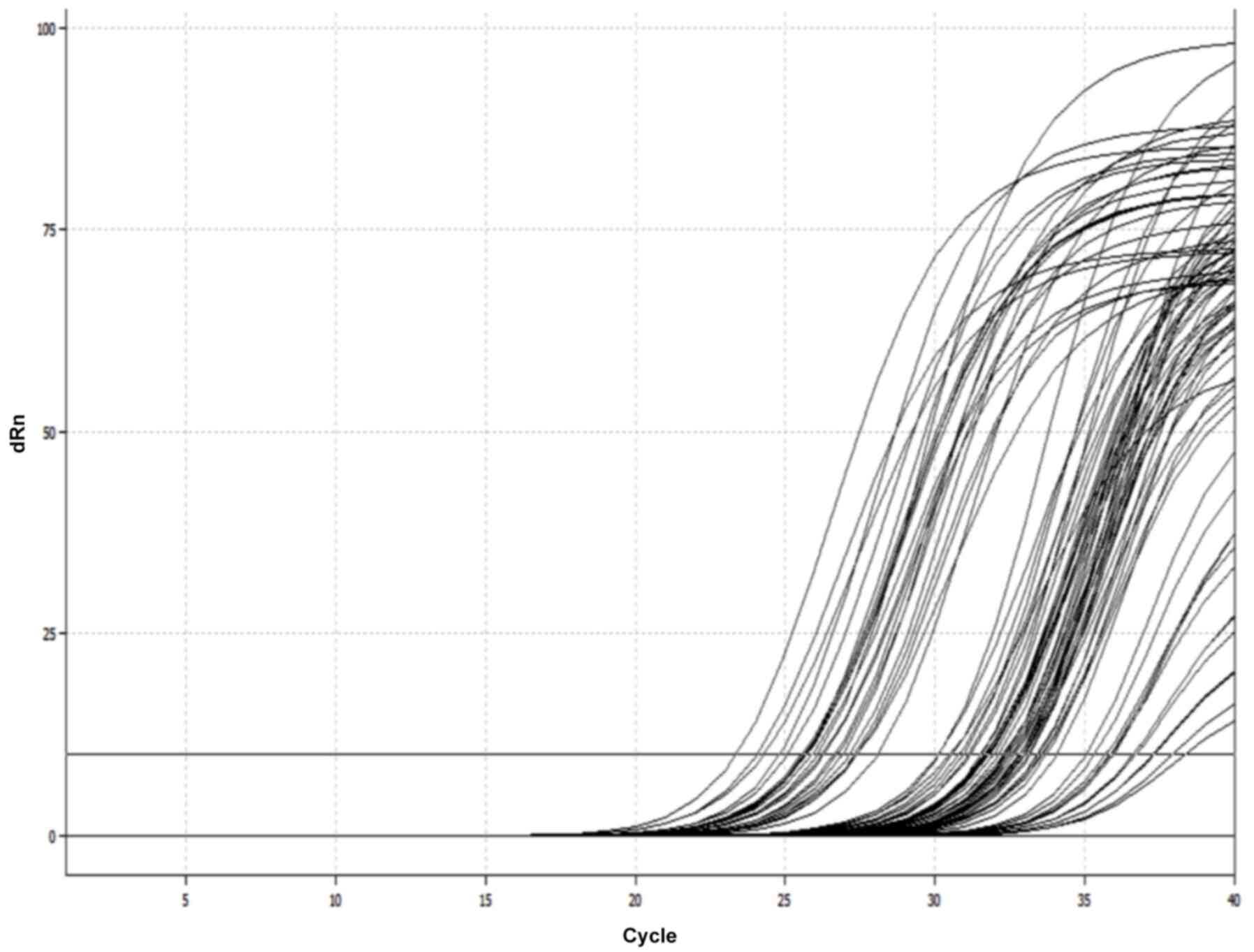

Quantitative PCR

Quantitative PCR was carried using the miRCURY LNA

miRNA PCR Starter kit (cat. no. 339320, Qiagen, Inc.) and the

miRCURY LNA SYBR®-Green PCR kit (cat. no, 339346,

Qiagen, Inc.) on a real-time thermal cycler qTOWER³ (Analytik Jena

India Private Limited). First, the cDNA volume (10 µl total RT

reaction volume) was diluted to 1:30 by the addition of 290 µl

RNase-free water to a 10-µl RT reaction prior to use. The primers

of the miRCURY LNA miRNA PCR assays used were for miR-16, miR-27a,

miR-122 and miR-155. All reactions were carried out in duplicate.

The reaction mixture and real-time cycler program were set up as

per the instructions of the manufacturer. The florescence was

detected and cycle-threshold (Cq) values were obtained. In the

present study, miR-16 was used as an endogenous control to

normalize the expression levels of miR-27a, miR-122 and

miR155(20). Data were analyzed

using the comparative ∆∆Cq method (2-∆∆Cq) (21). The data of miR-27a, miR-122 and

miR155 expression levels were calculated as follows: ∆∆Cq=Cq

(target miR)-[Cq (target miR)-Cq (miR-16)] mean of controls. The

relative quantification was calculated using the 2-∆∆Cq

method for all miRNAs (miR-27a, miR-122 and miR-155) (Fig. 1).

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed using SPSS software

(SPSS software version 29.0.1.0; IBM Corp.). The general

characteristics of the cases and controls were compared using the

t-test; the t-test was used for the comparison of continuous

variables and the Chi-squared was used for categorical data where

the data could be placed in a 2x2 table representation. The

Kruskal-Wallis-H test was used to compare differences in the serum

levels of miRNAs among the three groups (patients with early-stage

breast cancer, benign breast tumors and healthy controls). Dunn's

post hoc test was used following the Kruskal- Wallis test. The

Mann-Whitney test was used for those continuous variables which did

not have normal distribution of data as demonstrated by the

Shapiro-Wilk test. In all analyses, a value of P<0.05 was

considered to indicate a statistically significant difference. For

assessment of the diagnostic potential of miRNAs, receiver

operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was performed and the

area under the ROC curve (AUC) was calculated. The sensitivity,

specificity, negative predictive value (NPV), positive predictive

value (PPV) and likelihood ratios (LRs) for differentiating between

early-stage breast cancer, benign breast tumors and healthy control

were also calculated.

Results

Expression levels of miRNA-27a, -122

and -155 in the study samples

The present study included 112 cases (56 patients

with early-stage breast cancer and 56 patients with benign breast

tumors) and 56 healthy controls to determine the circulating levels

of miRNA-27a, -122 and -155.

The comparison of the age, parity, menstrual status

and body mass index revealed that there were no statistically

significant differences between the cases and healthy controls

(P-value >0.05); however, statistically significant differences

were found in family history and personal habits (tobacco intake)

between the cases and healthy controls (P-value <0.05).

Biochemical parameters, such as alanine transaminase (ALT),

aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), urea,

creatinine, hemoglobin (Hb), total white blood cell (WBC) and

platelet count exhibited no statistically significant differences

between the cases and healthy controls (P-value >0.05) (Table I).

| Table IGeneral examination parameters and

biochemical parameters. |

Table I

General examination parameters and

biochemical parameters.

| Parameter | Cases (n=112) | Controls (n=56) | P-value |

|---|

| Age group | | | P=0.860c |

|

<46

years | 78 (69.6%) | 38 (67.9%) | |

|

≥46

years | 34 (30.4%) | 18 (32.1%) | |

| Age (years) | 37.43±12.51 | 40.5±10.6 | P=0.099

c |

| Parity | | | P=0.589 |

|

Nullipara | 33 (29.5%) | 14 (25%) | |

|

Para | 79 (70.5%) | 42 (75%) | |

| Menstrual

status | | | P=0.721 |

|

Premenopausal | 32 (28.6%) | 18 (32.1%) | |

|

Postmenopausal | 80 (71.4%) | 38 (67.9%) | |

| BMI | 23.28±4.15 | 22.83±2.91 | P=0.416

c |

| Family history | | | P=0.032

c |

|

Negative | 102 (91%) | 56 (100%) | |

|

Positive | 10 (9%) | 0 | |

| Personal habits:

Tobacco intake | | | P=0.03

c |

|

No | 103 (92%) | 56 (100%) | |

|

Yes | 9 (8%) | 0 | |

| ALT (U/l) mean ±

2SD | 26±11.25 | 27.1±8.5 |

P=0.514t |

| AST (U/l) mean ±

2SD | 23.82±14.68 | 27.29±10.39 | P=0.08

t |

| ALP (U/l) mean ±

2SD | 83.7±19.32 | 80.8±18.13 | P=0.342

t |

| Urea(mg/dl) mean ±

2SD | 20.19±5.98 | 20.77±5.95 | P=0.557

t |

| Creatinine (mg/dl)

mean ± 2SD | 0.79±0.13 | 0.83±0.114 | P=0.108

t |

| Hb (g/dl) mean ±

2SD | 11.74±14.68 | 11.79±14.68 | P=0.735

t |

| WBC

(x103/µl) mean ± 2SD | 8.14±2.26 | 7.93±1.91 | P=0.548

t |

| Platelets

(x103/µl) mean ± 2SD | 268.38±79.5 | 262.29±66.3 | P=0.601

t |

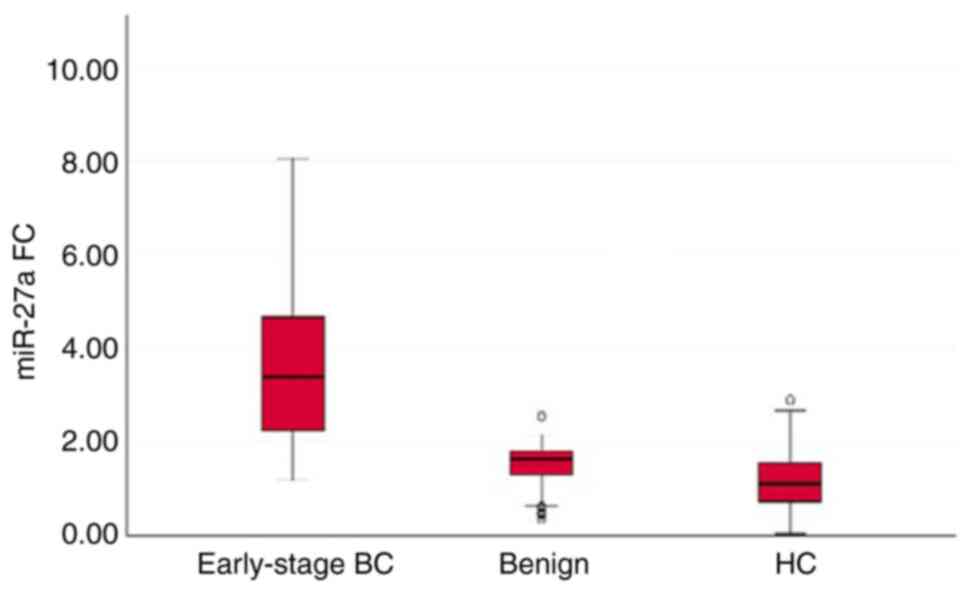

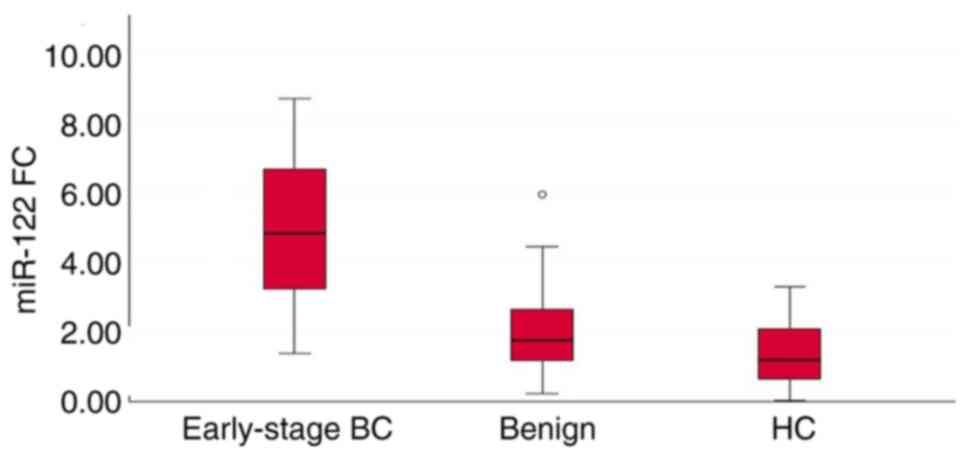

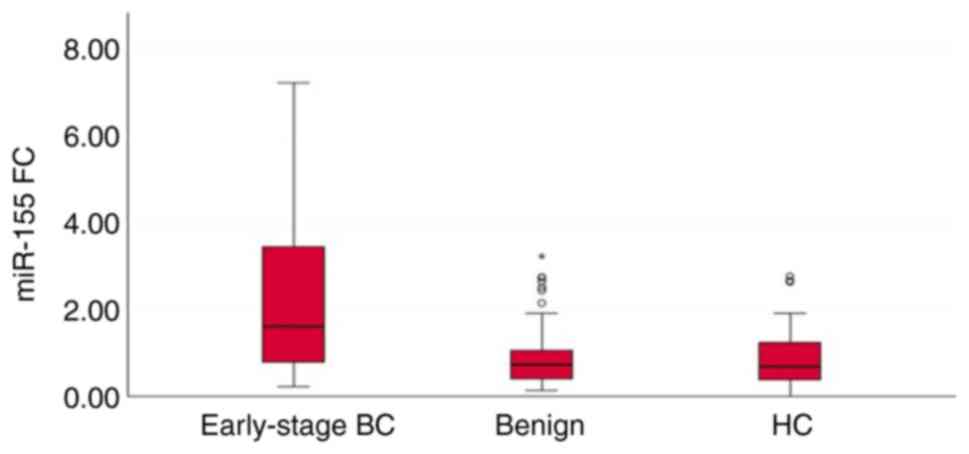

The results revealed that the expression levels of

the three miRNAs (miR-27a, miR-122 and miR-155) in serum were

significantly increased in patients with early-stage breast cancer

when compared to those of patients with benign breast tumors and

healthy controls (P<0.001). There was a significant difference

in the serum levels of miR-27a (P=0.015) and miR-122 (P=0.028),

between the patients with benign breast tumors and healthy

controls; the serum levels of these two miRNAs were upregulated in

patients with benign breast tumors when compared to those of the

healthy controls. However, there was no significant difference in

the serum levels of miR-155 (P=0.935) between the healthy controls

and patients with benign breast tumors (Table II and Figs. 2, 3

and 4). It was also found that the

miRNA-16 expression levels were relatively constant (mean, 1.4586;

SD, 0.08; data not shown).

| Table IISerum levels of miR-27a, -122 and

-155 in patients with early-stage breast cancer, patients with

benign breast tumors and healthy controls. |

Table II

Serum levels of miR-27a, -122 and

-155 in patients with early-stage breast cancer, patients with

benign breast tumors and healthy controls.

| A, Based on the

total study population (n=168) |

|---|

| Variables | miR-27a | P-value | miR-122 | P-value | miR-155 | P-value |

|---|

| Early-stage breast

cancer (n=56) | 3.75±1.98, 3.3995

(1.19-8.07) |

<0.001a,b,c | 4.94±2.07, 4.8356

(1.37-8.71) |

<0.001a,b,c | 2.22±1.77, 1.6279

(0.22-7.23) |

<0.001a,b |

| Benign breast

tumors (n=56) | 1.52±0.49, 1.6566

(0.38-2.56) | | 1.97±1.19, 1.7683

(2.23-5.95) | | 0.95±0.77, 0.7364

(0.15-3.24) | |

| Healthy controls

(n=56) | 1.22±0.69, 1.1175

(0.08-2.92) | | 1.36±0.87, 1.2031

(0.05-3.29) | | 0.91±0.67, 0.6949

(0.02-2.78) | |

| B, Based on age

status (years) |

| Variables | miR-27a | P-value | miR-122 | P-value | miR-155 | P-value |

| <46 years | | | | | | |

|

Early-stage

breast cancer (n=32) | 3.10±1.92, 2.5137

(1.19-8.00) |

<0.001a,b | 4.26±1.95, 4.0168

(1.37-8.71) |

<0.001a,b,c | 1.43±1.21, 1.1016

(0.22-4.87) | 0.172 |

|

Benign

breast tumors (n=46) | 1.53±0.49, 1.6567

(0.38-2.56) | | 1.93±1.19, 1.6457

(0.23-5.95) | | 1.02±0.82, 0.7364

(0.15-3.24) | |

|

Healthy

controls (n=56) | 1.32±0.69, 1.2012

(0.14-2.92) | | 1.52±0.73, 1.3465

(0.32-2.94) | | 1.07±0.72, 0.7789

(0.21-2.78) | |

| ≥46 | | | | | | |

|

Early-stage

breast cancer (n=24) | 4.62±1.75, 3.9969

(1.54-8.07) |

<0.001a,b,c | 5.85±1.89, 6.5157

(1.39-8.15) |

<0.001a,b,c | 3.26±1.86, 2.6926

(0.55-7.24) |

<0.001a,b,c |

|

Benign

breast tumors (n=10) | 1.47±0.55, 1.7148

(0.51-1.91) | | 2.19±2.21, 2.0998

(0.36-4.09) | | 0.63±0.35, 0.6560

(0.22-1.38) | |

|

Healthy

controls (n=18) | 1.00±0.64, 1.0235

(0.08-2.56) | | 1.01±1.05, 0.5133

(0.05-3.29) | | 0.58±0.42, 0.5117

(0.02-1.39) | |

| C, Based on

menstrual status |

| Variables | miR-27a | P-value | miR-122 | P-value | miR-155 | P-value |

| Premenopausal | | | | | | |

|

Early-stage

breast cancer (n=29) | 2.74±1.51, 2.3347

(1.19-6.99) |

<0.001a,b,c | 3.99±1.82,3 .5368

(1.37-8.71) |

<0.001a,b,c | 1.16±0.89, 0.8317

(0.22-4.82) | <0.412 |

|

Benign

breast tumors (n=51) | 1.54±0.48, 1.6662

(0.38-2.56) | | 2.01±1.19, 1.8169

(0.23-5.95) | | 0.98±0.71, 0.7406

(0.15-3.24) | |

|

Healthy

controls (n=38) | 1.35±0.67, 1.2012

(0.41-2.92) | | 1.51±0.71, 1.3465

(0.32-2.94) | | 1.07±0.70, 0.8378

(0.21-2.78) | |

|

Early-stage

breast cancer (n=27) | 4.84±1.87, 4.0706

(1.54-8.07) |

<0.001a,b,c | 5.95±1.84, 6.5415

(1.39-8.25) |

<0.001a,b,c | 3.36±1.77, 3.0635

(1.24-7.24) |

<0.001a,b |

|

Benign

breast tumors (n=5) | 1.30±0.66, 1.6375

(0.51-1.90) | | 1.62±1.29, 1.7196

(0.36-3.48) | | 0.64±0.47, 0.5599

(0.22-1.38) | |

|

Healthy

controls (n=18) | 0.95±0.67, 0.8877

(0.08-2.56) | | 1.03±1.08, 0.5133

(0.05-3.29) | | 0.58±0.46, 0.4451

(0.02-1.75) | |

To examine the effect of aging and menstrual status

on the serum levels of miR-27a, miR-122 and miR-155, the samples

were classified into different groups. In the group aged <46

years and in the premenopausal group, the serum levels of miR-27a

and miR-122 were significantly increased in the patients with

early-stage breast cancer when compared to those with benign breast

tumors and the healthy controls (P<0.01); however, there was no

significant difference between the patients with benign breast

tumors and the healthy controls (miR-27a, P>0.05; and miR-122,

P>0.05). The serum levels of miR-155 exhibited no significance

difference among all three groups (P>0.05). In the group aged

≥46 years and in the postmenopausal group, the serum levels of all

three miRNAs were significantly increased in the patients with

early-stage breast cancer when compared to those with benign breast

tumors and the healthy controls (P<0.01); however, there was a

no significant difference between the patients with benign breast

tumors and the healthy controls (P>0.05) (Table II).

The serum levels of miR-27a, miR-122 and miR-155

exhibited a statistically significant difference between the groups

as regards clinicopathological features, such as Breast Imaging

Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS) scoring and pathological types;

however, there were no statistically significant differences

(P>0.05) among the groups in parameters, such as hormone

receptors (molecular subtypes: Luminal-A, Luminal-B, Her2-enriched

and TNBC), Ki67 proliferation-index (<14 group and ≥14 group)

and the staging of early-stage breast cancer (stage I, IIA and IIB)

(Table III).

| Table IIIComparison of clinicopathological

characteristics of the patients and the serum levels of the three

miRNAs. |

Table III

Comparison of clinicopathological

characteristics of the patients and the serum levels of the three

miRNAs.

| | | miR-27a | miR-122 | miR-155 |

|---|

| Variables | No. of cases | Mean ± 2SD, median

(min-max) | P-value | Mean ± 2SD, median

(min-max) | P-value | Mean ± 2SD, median

(min-max) | P-value |

|---|

| BI-RADS

scoring | | | | | | | |

|

Group 1: 0-2

(0,1,2) | 27 | 1.67±0.37, 1.7119

(0.49-2.56) |

<0.001b,c | 1.94±1.25, 1.6945

(0.45-5.95) |

<0.001a,b,c | 0.77±0.63, 0.5760

(0.15-2.75) |

<0.001b,c |

|

Group 2: 3-5

(3,4,5) | 29 | 1.39±0.56, 1.5369

(0.38-2.17) | | 2.00±1.16, 1.9790

(0.23-4.45) | | 1.11±0.85, 0.8201

(0.15-3.24) | |

|

Group 3:

6 | 56 | 3.75±1.98, 3.3995

(1.19-8.07) | | 4.94±2.07, 4.8356

(1.37-8.71) | | 2.22±1.77, 1.6279

(0.22-7.24) | |

| Pathological

types | | | | | | | |

|

Fibroadenoma

(benign breast tumor) | 56 | 1.52±0.49, 1.6567

(0.38-2.56) |

<0.001a,b | 1.97±1.19, 1.7683

(0.23-5.95) |

<0.001a,b,c | 0.95±0.77, 0.7364

(0.15-3.24) |

<0.001a,b,c |

|

Group 1:

IDC | 49 | 3.73±2.02, 3.2804

(1.25-8.07) | | 4.85±2.13, 4.6807

(1.37-8.71) | | 2.19±1.77, 1.6275

(0.22-7.24) | |

|

Group 2:

ILC | 7 | 3.91±1.80, 1.0706

(1.19-7.05) | | 5.54±1.51, 5.4832

(3.52-7.51) | | 2.44±1.86, 1.6283

(0.71-5.65) | |

| Hormone

receptors | | | | | | | |

|

Group 1:

Luminal A | 26 | 3.23±1.78, 2.9518

(1.19-7.02) | 0.119 | 4.59±2.05, 4.3141

(1.37-7.93) | 0.139 | 2.19±1.85, 1.4834

(0.41-6.67) | 0.931 |

|

Group 2:

Luminal B | 13 | 3.84±1.64, 3.9466

(1.34-7.05) | | 5.86±1.79, 6.0528

(2.79-8.71) | | 2.07±1.35, 1.8185

(0.51-4.96) | |

|

Group 2:

Her2-enriched | 9 | 4.14±2.56, 3.2271

(1.31-8.07) | | 4.14±2.01, 4.2586

(1.46-7.34) | | 2.54±2.33, 1.5536

(0.22-7.24) | |

|

Group 4:

TNBC | 8 | 4.89±2.18, 4.0526

(1.96-8.00) | | 5.46±2.30, 5.9865

(1.89-8.25) | | 2.19±1.67, 1.5673

(0.59-4.87) | |

| Ki67 | | | | | | | |

|

Group 1:

<14 | 28 | 3.54±1.93, 3.4505

(1.19-8.07) | 0.523 | 5.04±1.88, 4.8381

(1.92-8.71) | 0.819 | 2.12±1.65, 1.7569

(0.51-6.67) | 0.819 |

|

Group 2:

≥14 | 28 | 3.96±2.05, 3.3030

(1.30-8.00) | | 4.83±2.27, 4.8355

(1.37-8.25) | | 2.32±1.90, 1.5673

(0.22-7.24) | |

| Tumor staging | | | | | | | |

|

Group 1:

I | 20 | 3.70±1.91, 3.4505

(1.25-8.07) | 0.997 | 4.49±2.01, 4.2114

(1.39-7.51) | 0.104 | 2.53±1.97, 1.8038

(0.22-7.24) | 0.663 |

|

Group 2:

IIA | 18 | 3.83±2.20, 3.2149

(1.19-8.00) | | 4.58±2.21, 4.6483

(1.37-8.25) | | 2.09±1.83, 1.3606

(0.41-6.67) | |

|

Group 3:

IIB | 18 | 3.73±1.94, 3.5885

(1.31-7.23) | | 5.79±1.81, 5.9668

(1.77-8.71) | | 1.99±1.48, 1.5604

(0.49-4.82) | |

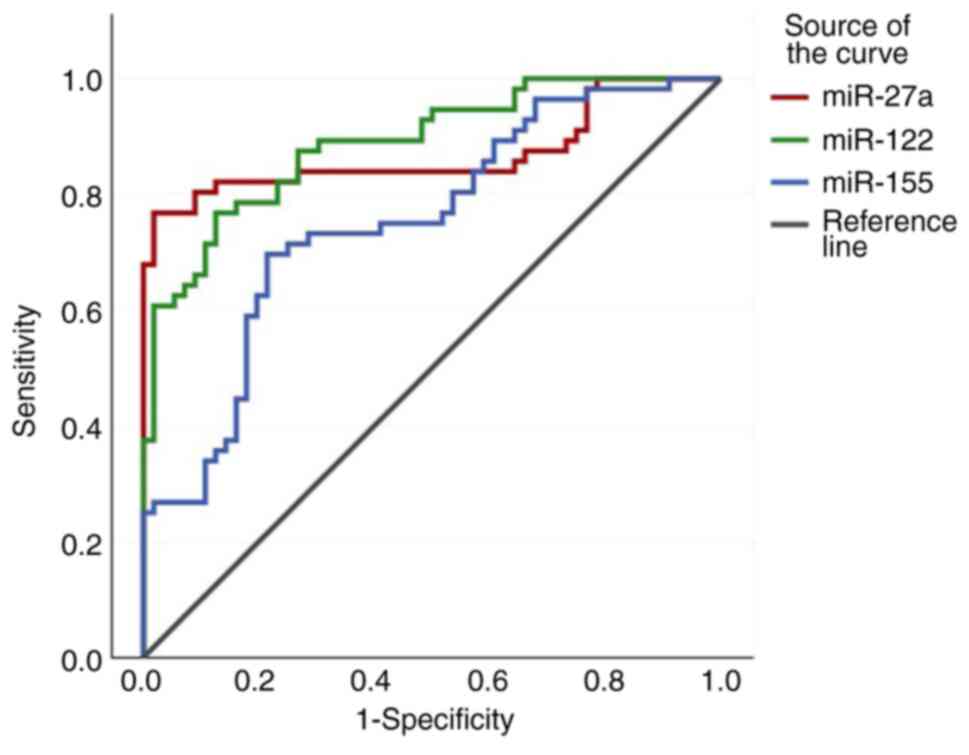

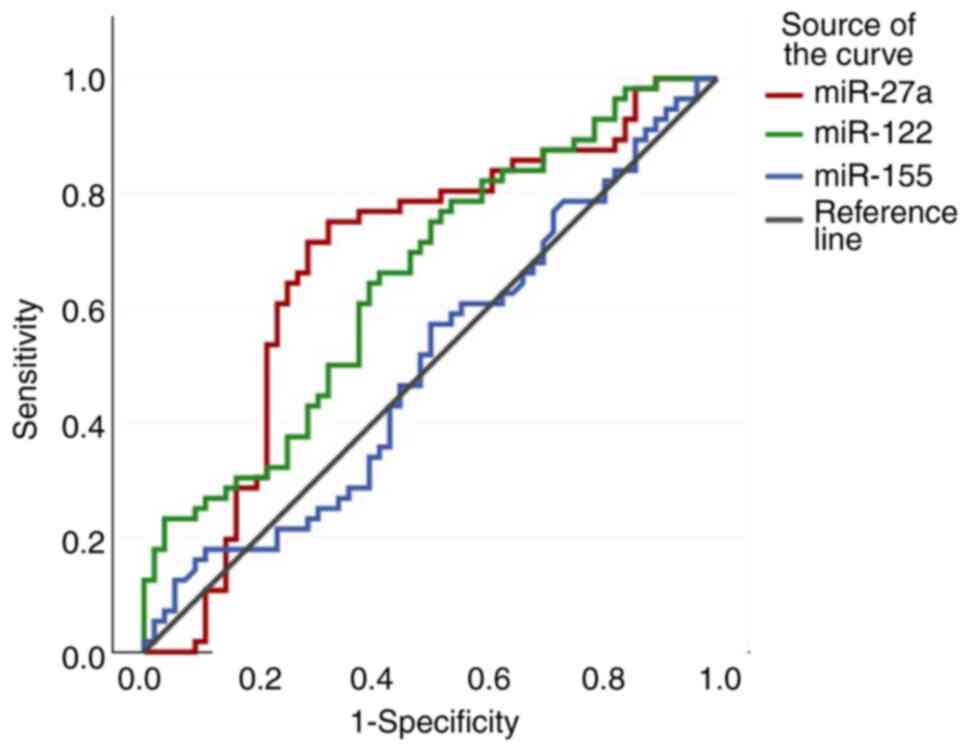

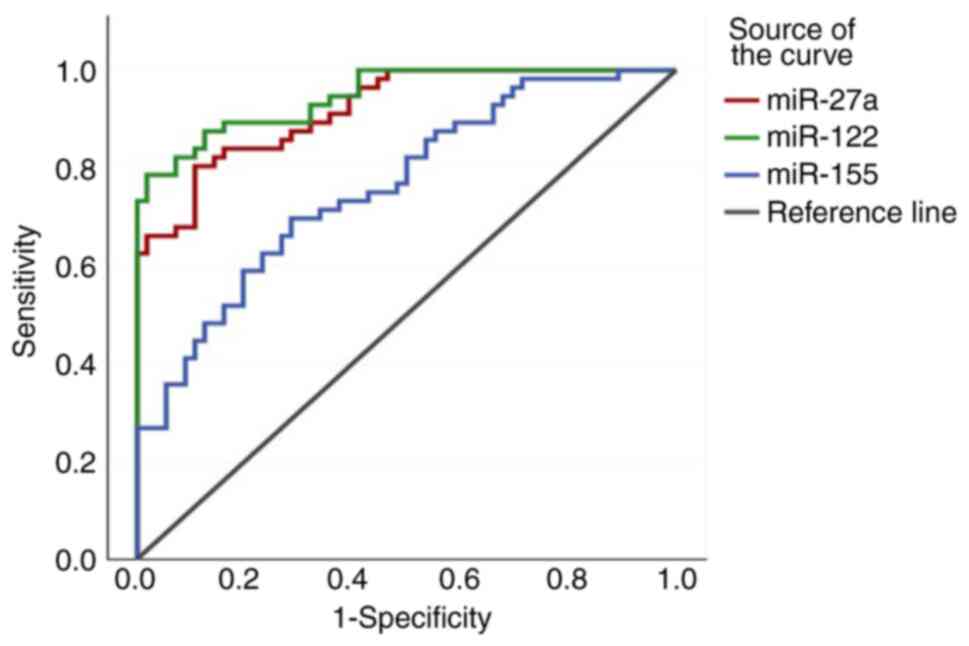

Diagnostic efficacy of miR-27a,

miR-122 and miR-155 evaluated by ROC curve analysis

The diagnostic efficacy of the three miRNAs

(miR-27a, miR-122 and miR-155) in differentiating between patients

with early-stage breast cancer and between patients with benign

breast tumors and healthy controls was then determined. Cut-off

fold change values, P-values, PPV and NPV (Table IV) were obtained. The results

revealed that miR-27a and miR-122 exhibited significant efficacy in

differentiating all groups; however, miR-155 did not exhibit

significant efficacy in differentiating between benign tumors and

healthy controls. The corresponding AUC (95% CI), sensitivity and

specificity of the ROC curves are depicted in Figs. 5, 6

and 7 and Tables V, VI and VII.

| Table IVSensitivity, specificity, NPV, PPV

and LRs of the three miRNAs. |

Table IV

Sensitivity, specificity, NPV, PPV

and LRs of the three miRNAs.

| Compared

Groups | miRNAs | P-value | Cut-off FC

value | AUC (95% CI) | Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV | LR+ | LR- |

|---|

| Early stage breast

cancer (BC)-healthy controls | miR-27a | <0.001 | 2.0651 | 0.920 | 80.4 | 89.3 | 88.2 | 81.9 | 7.51 | 0.22 |

| | miR-122 | <0.001 | 3.0163 | 0.947 | 78.6 | 98.2 | 97.7 | 82 | 43.6 | 0.22 |

| | miR-155 | <0.001 | 1.1272 | 0.762 | 69.6 | 71.4 | 70.9 | 29.8 | 2.43 | 0.42 |

| Early stage breast

cancer-benign tumour | miR-27a | <0.001 | 2.2016 | 0.870 | 76.8 | 98.2 | 97.7 | 80.8 | 42.66 | 0.24 |

| | miR-122 | <0.001 | 3.1888 | 0.888 | 78.6 | 87.5 | 86 | 79 | 6.14 | 0.26 |

| | miR-155 | <0.001 | 1.1336 | 0.753 | 69.6 | 78.6 | 76.4 | 72.1 | 3.25 | 0.39 |

| Benign

tumour-healthy controls | miR-27a | 0.015 | 1.3492 | 0.675 | 75 | 67.9 | 70 | 73 | 2.33 | 0.37 |

| | miR-122 | 0.028 | 0.9302 | 0.651 | 82.1 | 58.9 | 58.2 | 69.6 | 1.39 | 0.43 |

| | miR-155 | 0.935 | 0.6101 | 0.502 | 60.7 | 44.6 | 52 | 53.1 | 1.09 | 0.88 |

| Table VROC curve analysis of the three

miRNAs for differentiating between patients with early-stage breast

cancer and healthy controls (corresponding to Fig. 5). |

Table V

ROC curve analysis of the three

miRNAs for differentiating between patients with early-stage breast

cancer and healthy controls (corresponding to Fig. 5).

| miRNA | Test | Early-stage breast

cancer | Healthy

controls | Total | P-value from

χ2 test |

|---|

| miR-27a cut-off

fold | Test+ | 45 | 6 | 51 | 0.001 |

| change=2.06519 | Test- | 11 | 50 | 61 | |

| Total | | 56 | 56 | 112 | |

| miR-122 cut-off

fold | Test+ | 44 | 1 | 45 | 0.001 |

|

change=3.016371 | Test- | 12 | 55 | 67 | |

| Total | | 56 | 56 | 112 | |

| miR-155 cut-off

fold | Test+ | 39 | 16 | 55 | 0.001 |

| change=1.12727 | Test- | 17 | 40 | 57 | |

| Total | | 56 | 56 | 112 | |

| Table VIROC curve analysis of three miRNAs

for differentiating between patients with early-stage breast cancer

and patients with benign breast tumors (corresponding to Fig. 6). |

Table VI

ROC curve analysis of three miRNAs

for differentiating between patients with early-stage breast cancer

and patients with benign breast tumors (corresponding to Fig. 6).

| miRNA | Test | Early-stage breast

cancer | Healthy

controls | Total | P-value from

χ2 test |

|---|

| miR-27a cut-off

fold | Test+ | 43 | 1 | 44 | 0.001 |

| change=2.20164 | Test- | 13 | 55 | 68 | |

| Total | | 56 | 56 | 112 | |

| miR-122 cut-off

fold | Test+ | 43 | 7 | 60 | 0.001 |

| change=3.18884 | Test- | 13 | 49 | 62 | |

| Total | | 56 | 56 | 112 | |

| miR-155 cut-off

fold | Test+ | 39 | 12 | 51 | 0.001 |

| change=1.13369 | Test- | 17 | 44 | 61 | |

| Total | | 56 | 56 | 112 | |

| Table VIIROC curve analysis of the three

miRNAs for differentiating between patients with benign breast

tumors and healthy controls (corresponding to Fig. 7). |

Table VII

ROC curve analysis of the three

miRNAs for differentiating between patients with benign breast

tumors and healthy controls (corresponding to Fig. 7).

| miRNA | Test | Early-stage breast

cancer | Healthy

controls | Total | P-value from

χ2 test |

|---|

| miR-27a cut-off

fold | Test+ | 42 | 18 | 60 | 0.001 |

| change=1.34919 | Test- | 14 | 38 | 52 | |

| Total | | 56 | 56 | 112 | |

| miR-122 cut-off

fold | Test+ | 46 | 33 | 79 | 0.001 |

| change=0.93025 | Test- | 10 | 23 | 33 | |

| Total | | 56 | 56 | 112 | |

| miR-155 cut-off

fold | Test+ | 34 | 31 | 65 | 0.001 |

| change=0.61011 | Test- | 22 | 25 | 47 | |

| Total | | 56 | 56 | 112 | |

Discussion

Tissue gene biomarkers have improved the diagnosis

of breast cancer to a great extent; however, there are limitations

to their applications due to invasiveness, risk of hemorrhage and

the unpleasant nature of the diagnostic procedures. The estimation

of non-invasive or minimally invasive biomarkers, such as miRNA

expression levels in blood and serum, is a highly sensitive and

specific method which can benefit both clinicians and patients in

the screening, diagnosis and prognosis of patients with early-stage

breast cancer (6). Although there

has been substantial success in the discovery of serum biomarkers,

it is imperative to identify biomarkers that are useful for the

early diagnosis of affected patients.

Of note, in the present study, immunohistochemistry

was performed as routine diagnostic workup for sub-classifying the

patients with breast cancer. In the present study, the expression

levels of the three miRNAs (miR-27a, miR-122 and miR-155) were

significantly upregulated in the serum of patients with early-stage

breast cancer compared to those in patients with benign breast

tumors and healthy controls. These findings indicate that these

three miRNA are more likely related to early-stage breast cancer.

These findings also indicate these three miRNAs may be beneficial

biomarkers for the diagnosis of early-stage breast cancer.

In their study, Swellam et al (13) examined the expression levels of

miR-27a and tumor markers (CEA and CA15.3) among three investigated

groups; patients with primary breast cancer, patients with benign

breast tumors and healthy controls; they demonstrated that

miRNA-27a was superior to the two tumor markers in specificity and

accuracy for the detection of early-stage breast cancer. The

expression levels of miR-27a in serum were significantly increased

in patients with primary breast cancer when compared to those in

patients with benign breast tumors followed by the healthy controls

who had the lowest serum level (13). The results of their study are

comparable to those of the present study as regards the serum

levels of miR-27a. Previous studies performed by Wu et al

(22) and Ding et al

(23) reported the oncogenic role

of miR-27a among several other types of cancer. It was observed

that, the upregulation of miR-27a targeted the FOXO1 gene, which

was responsible for cell cycle regulation, thus promoting evasion

from apoptosis and cell proliferation in breast cancer (24).

Saleh et al (25) demonstrated that miR-122 exhibited an

improved specificity and sensitivity than tumor markers (CEA and

CA15-3) in the diagnosis of breast cancer and in predicting breast

cancer metastasis. In a cohort study, Wu et al (26) demonstrated that circulating levels

of miRNA-122 had a good specificity and sensitivity in predicting

metastasis. It was also found that the miR-122 level was increased

in patients who had relapsed after recovery and was able to

determine relapse in patients with stage IIa, IIb and III breast

cancer (26). On the other hand,

Wang et al (27)

demonstrated that miR-122 functioned as a tumor-suppressor in

breast cancer cells by suppressing the IGF1R-mediated downstream

Akt/mTOR/p70S6K signaling pathway and inhibiting breast cancer cell

growth. They demonstrated that the miR-122 expression levels

decreased in breast cancer cells when compared to normal breast

tissue (27). This discrepancy in

the results of miR-122 levels, between studies performed on breast

tissue samples and blood samples can be explained in the study by

Fong et al (28). Fong et

al (28) demonstrated that

breast cancer cells secrete large amounts of miR-122-secreting

vesicles, which leads to a decrease in miR-122 levels

intracellularly. This secreted miR-122 affects non-cancer cells and

decreases their uptake of glucose by downregulating glycolytic

enzyme pyruvate kinase. In this manner, miR-122 supports cancer

cell viability and metastasis by increasing nutrient supply

(28). Thus, the majority of breast

cancer cells have decreased levels of miR-122. In the present

study, miR-122 expression levels in serum were increased in

patients with early-stage breast cancer compared to those with

benign breast tumors and healthy controls. miR-122 also exhibited

improved sensitivity and specificity in detecting early-stage

breast cancer.

In the study by Hosseini Mojahed et al

(29), it was demonstrated that the

miR-155 expression levels in serum were significantly higher in

patients with breast cancer when compared with healthy controls.

The combination of three miRNAs, miR 17-5p, miR-155 and miR-222

levels, when compared with tumour markers (CEA and CA15.3) for

breast cancer screening, has revealed that the three miRNAs were

more effective than tumour markers for the early diagnosis of

breast cancer, particularly in high-risk groups (13,30).

In another study by Bašová et al (31), the serum levels of miR-155 were

highly predictive in determining relapse in early-stage breast

cancer. Another study demonstrated that the upregulation of miR-155

inhibited the translation of mRNAs, such as RhoA, FOXO3A, and

SOCS1. which led to the evasion of apoptosis and increased cell

proliferation (32). The decreased

levels of BRCA1 due to mutation upregulate the levels of miR-155 in

serum. This occurs since BRCA1 regulates miR-155 by binding to the

miR-155 promotor and recruiting histone deacetylases (33). In the present study, the levels of

miR-155 were significantly increased in patients with early-stage

breast cancer, when compared to healthy controls and have good

sensitivity and specificity were observed.

In the present study, ROC analysis revealed that the

serum levels of miR-27a, miR-122 and miR-155 exhibited good

accuracy with AUC values of 0.920, 0.947 and 0.762, respectively

for differentiating between early-stage breast cancer and healthy

controls. These three miRNAs also exhibited fair accuracy with AUC

values of 0.870, 0.888 and 0.753, respectively for differentiating

between early-stage breast cancer and benign breast tumors.

In conclusion, the results of the present study

indicate that the levels of miR-27a, miR-122 and miR-155 are

increased in patients with breast cancer. Their serum levels have

reliable sensitivity and specificity in detecting early-stage

breast cancer. These three miRNAs may thus potential for use as

non-invasive biomarkers in the diagnosis and screening of breast

cancer. However, their clinical applicability needs to be evaluated

in multiple centers in order to confirm their diagnostic

efficacy.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: The present study was funded by a ICMR-MD/MS thesis

grant (registration no. MD21DEC-0045,

No.3/2/December-2021/PG-Thesis-HRD(14) dated May 30, 2022.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current

study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable

request.

Authors' contributions

SSr and SSa wrote the manuscript and performed the

experiments and generated the figures. DKM and TSM collected the

clinical data. PM and SM provided the data of the recruited

patients from the Departments of Pathology and Radiodiagnosis, All

India Institute of Medical Sciences (Bhubaneswar, India),

respectively. All authors made critical revisions, and all authors

have read and approved the final manuscript. All authors (SSr, SSa,

DKM, TSM, PM and SM) confirm the authenticity of all the raw

data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Ethical clearance obtained from the Institutional

Ethics Committee (IEC) of All India Institute of Medical Sciences

(AIIMS), Bhubaneswar, India (IEC/AIIMS BBSR/PG Thesis/2021-22/32).

Each patient was explained the nature of study and after obtaining

their written consent, they were inducted into the study.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M,

Soerjomataram I, Jemal A and Bray F: Global cancer statistics 2020:

GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36

cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 71:209–249.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Malvia S, Bagadi SA, Dubey US and Saxena

S: Epidemiology of breast cancer in Indian women. Asia Pac J Clin

Oncol. 13:289–295. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Momenimovahed Z and Salehiniya H:

Epidemiological characteristics of and risk factors for breast

cancer in the world. Breast Cancer (Dove Med Press). 11:151–164.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Practice bulletin no 182: Hereditary

breast and ovarian cancer syndrome. Obstet Gynecol. 130:e110–e126.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Jafari SH, Saadatpour Z, Salmaninejad A,

Momeni F, Mokhtari M, Nahand JS, Rahmati M, Mirzaei H and Kianmehr

M: Breast cancer diagnosis: Imaging techniques and biochemical

markers. J Cell Physiol. 233:5200–5213. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Wang L: Early diagnosis of breast cancer.

Sensors (Basel). 17(1572)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Di Leva G, Garofalo M and Croce CM:

MicroRNAs in cancer. Annu Rev Pathol. 9:287–314. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Hussen BM, Hidayat HJ, Salihi A, Sabir DK,

Taheri M and Ghafouri-Fard S: MicroRNA: A signature for cancer

progression. Biomed Pharmacother. 138(111528)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Heneghan HM, Miller N and Kerin MJ:

Circulating microRNAs: Promising breast cancer biomarkers. Breast

Cancer Res. 13(402)2011.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Ng EK, Li R, Shin VY, Jin HC, Leung CP, Ma

ES, Pang R, Chua D, Chu KM, Law WL, et al: Circulating microRNAs as

specific biomarkers for breast cancer detection. PLoS One.

8(e53141)2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Giordano C, Accattatis FM, Gelsomino L,

Del Console P, Győrffy B, Giuliano M, Veneziani BM, Arpino G, De

Angelis C, De Placido P, et al: miRNAs in the box: Potential

diagnostic role for extracellular vesicle-packaged miRNA-27a and

miRNA-128 in breast cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 24(15695)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Ljepoja B, García-Roman J, Sommer AK,

Wagner E and Roidl A: MiRNA-27a sensitizes breast cancer cells to

treatment with selective estrogen receptor modulators. Breast Edinb

Scotl. 43:31–38. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Swellam M, Zahran RFK, Ghonem SA and

Abdel-Malak C: Serum MiRNA-27a as potential diagnostic nucleic

marker for breast cancer. Arch Physiol Biochem. 127:90–96.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Elghoroury EA, Abdelghafar EE, Kamel S,

Awadallah E, Shalaby A, El-Saeed GSM, Mahmoud E, Kamel MM, Abobakr

A and Yousef RN: Dysregulation of miR-122, miR-574 and miR-375 in

Egyptian patients with breast cancer. PLoS One.

19(e0298536)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Ranjbari S, Rezayi M, Arefinia R,

Aghaee-Bakhtiari SH, Hatamluyi B and Pasdar A: A novel

electrochemical biosensor based on signal amplification of Au

HFGNs/PnBA-MXene nanocomposite for the detection of miRNA-122 as a

biomarker of breast cancer. Talanta. 255(124247)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Li M, Zou X, Xia T, Wang T, Liu P, Zhou X,

Wang S and Zhu W: A five-miRNA panel in plasma was identified for

breast cancer diagnosis. Cancer Med. 8:7006–7017. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Ali SA, Abdulrahman ZFA and Faraidun HN:

Circulatory miRNA-155, miRNA-21 target PTEN expression and activity

as a factor in breast cancer development. Cell Mol Biol

(Noisy-le-grand). 66:44–50. 2020.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Dziechciowska I, Dąbrowska M, Mizielska A,

Pyra N, Lisiak N, Kopczyński P, Jankowska-Wajda M and Rubiś B:

miRNA expression profiling in human breast cancer diagnostics and

therapy. Curr Issues Mol Biol. 45:9500–9525. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Kroh EM, Parkin RK, Mitchell PS and Tewari

M: Analysis of circulating microRNA biomarkers in plasma and serum

using quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR). Methods San

Diego Calif. 50:298–301. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Roth C, Rack B, Müller V, Janni W, Pantel

K and Schwarzenbach H: Circulating microRNAs as blood-based markers

for patients with primary and metastatic breast cancer. Breast

Cancer Res. 12(R90)2010.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408.

2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Wu XJ, Li Y, Liu D, Zhao LD, Bai B and Xue

MH: miR-27a as an oncogenic microRNA of hepatitis B virus- related

hepatocellular carcinoma. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 14:885–889.

2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Ding L, Zhang S, Xu M, Zhang R, Sui P and

Yang Q: MicroRNA-27a contributes to the malignant behavior of

gastric cancer cells by directly targeting PH domain and

leucine-rich repeat protein phosphatase 2. J Exp Clin Cancer Res.

36(45)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Guttilla IK and White BA: Coordinate

regulation of FOXO1 by miR-27a, miR-96, and miR-182 in breast

cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 284:23204–23216. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Saleh AA, Soliman SE, Habib MSE, Gohar SF

and Abo-Zeid GS: Potential value of circulatory microRNA122 gene

expression as a prognostic and metastatic prediction marker for

breast cancer. Mol Biol Rep. 46:2809–2818. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Wu X, Somlo G, Yu Y, Palomares MR, Li AX,

Zhou W, Chow A, Yen Y, Rossi JJ, Gao H, et al: De novo sequencing

of circulating miRNAs identifies novel markers predicting clinical

outcome of locally advanced breast cancer. J Transl Med.

10(42)2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Wang B, Wang H and Yang Z: MiR-122

inhibits cell proliferation and tumorigenesis of breast cancer by

targeting IGF1R. PLoS One. 7(e47053)2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Fong MY, Zhou W, Liu L, Alontaga AY,

Chandra M, Ashby J, Chow A, O'Connor ST, Li S, Chin AR, et al:

Breast-cancer-secreted miR-122 reprograms glucose metabolism in

premetastatic niche to promote metastasis. Nat Cell Biol.

17:183–194. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Hosseini Mojahed F, Aalami AH, Pouresmaeil

V, Amirabadi A, Qasemi Rad M and Sahebkar A: Clinical evaluation of

the diagnostic role of MicroRNA-155 in breast cancer. Int J

Genomics. 2020(9514831)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Swellam M, Zahran RFK, Abo El-Sadat Taha

H, El-Khazragy N and Abdel-Malak C: Role of some circulating MiRNAs

on breast cancer diagnosis. Arch Physiol Biochem. 125:456–464.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Bašová P, Pešta M, Sochor M and Stopka T:

Prediction potential of serum miR-155 and miR-24 for relapsing

early breast cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 18(2116)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Mattiske S, Suetani RJ, Neilsen PM and

Callen DF: The oncogenic role of miR-155 in breast cancer. Cancer

Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 21:1236–1243. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Chang S, Wang RH, Akagi K, Kim KA, Martin

BK and Cavallone L: Kathleen Cuningham Foundation Consortium for

Research into Familial Breast Cancer (kConFab). Haines DC, Basik M,

Mai P, et al: Tumor suppressor BRCA1 epigenetically controls

oncogenic microRNA-155. Nat Med. 17:1275–1282. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|