Introduction

According to statistics, ovarian cancer accounts for

2.5% of all malignant tumors, and accounts for 5% of female

cancer-related deaths, mainly due to late diagnosis. Despite recent

improvements in the diagnosis, ~70% of ovarian cancers are

diagnosed at an advanced stage, and only 30% of patients with

advanced-stage ovarian cancer survive for >5 years. Ovarian

cancer is a heterogeneous group of malignant tumors that vary in

etiology and molecular biology. Although the incidence and

mortality rates have decreased in recent years, there is still an

urgent need to explore the molecular biology of ovarian cancer in

order to further identify early diagnostic and therapeutic targets

(1,2).

There are numerous post-transcriptional

modifications in organisms, among which

N6-methyladenosine (m6A) is the most abundant

internal modification in eukaryotes (3), which plays a key role in various

biological processes, such as stem cell self-renewal and

differentiation, DNA damage and heat shock. m6A can be

regulated by specific enzymes known as ‘writers’, ‘erasers’ and

‘readers’. The ‘writers’ are methyltransferases, including

methyltransferase-like (METTL)3, METTL14 and Wilms tumor

1-associated protein. The ‘erasers’ are demethyltransferases,

including fat mass and obesity-associated and AlkB homolog 5, RNA

demethylase. The ‘readers’ are RNA-binding proteins, including the

YTH family. m6A-related proteins play a role in

modification and the regulation of the pathogenesis of various

types of cancer, such as leukemia, brain tumors, breast cancer,

liver cancer, cervical cancer and lung cancer (4).

Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) are DNA

sequence polymorphisms caused by variations in a single nucleotide

at the genomic level, which is the most common form of genetic

variation in humans (5). Some

studies have found that m6A and its polymorphisms are

associated with susceptibility to bladder cancer, gastric cancer,

pancreatic cancer and hepatoblastoma (6-9).

Moreover, METTL3 polymorphisms have been reported to affect the

susceptibility to neuroblastoma, hepatoblastoma and nephroblastoma

(10-12).

The association between METTL3 polymorphisms and the

development of ovarian cancer has rarely been reported, at least to

the best of our knowledge. Given that m6A and its

polymorphisms are associated with tumor susceptibility, it was

hypothesized that METTL3 SNPs may be associated with the risk of

developing ovarian cancer. In order to verify this hypothesis, the

present multicenter large sample case-control study was conducted

to investigate the association between METTL3 polymorphisms and the

susceptibility to ovarian cancer.

Patients and methods

Study population

Tissue samples from 244 patients with ovarian cancer

diagnosed by pathological analysis and blood samples from 276

normal controls were collected from the First Affiliated Hospital

of Jinan University (Guangzhou, China), Guangzhou Women's and

Children's Medical Center (Guangzhou, China) and Shunde Hospital of

Southern Medical University (Foshan, China). The present study was

approved by the ethics committees of the above three hospitals [the

Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Jinan

University (KY-2022-233), the Ethics Committee of Guangzhou Medical

University Women and Children's Medical Center (117A01), and the

Ethics Committee of Shunde Hospital, Southern Medical University

(KYLS20220903)]. In addition, written informed consent was obtained

from the subjects. The clinical data of the subjects has been

permitted for public disclosure, and the personal information of

the subjects has been concealed in the study results. The clinical

and pathological information of all subjects in the ovarian cancer

group was collected from the databases of the aforementioned

hospitals, including name, age, pregnancy and delivery, tumor

stage, pathological type and immunohistochemistry results. The

relevant information was obtained by querying the clinical medical

record system (Table SI).

SNP selection and genotyping

Genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood and

paraffin samples using the DNA extraction kit (Tiangen Biotech Co.,

Ltd.) (DP304-03). SNPs with potential biological functions were

screened using the NCBI dbSNP database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) and SNPinfo (http://snpinfo.niehs.nih.gov/) online software. Of

note, four SNPs (rs1263801 G>C, rs1139130 G>A, rs1061027

C>A and rs1061026 T>G) were selected for analysis. The

sequences for these SNPs were as follows: rs1263801 G>C,

CTGCCAAGAAATGACCACTACAAAA[C/G] and AGTCGTTATAACTGAGGGAACAAAG;

rs1139130 G>A, ACACAACCACTACTTACCCCCAGAG[A/G] and

TTTAGACATTCTCTCCCCAACTCCA; rs1061027 C>A,

TTCTGTCCTTAATCATAAATAATAG[A/C] and CCCTTGAGGACTAGCCTGTTCTCTG;

rs1061026 T>G, AAAACAATGTGAAGCTCTACTAAGT[G/T] and

CTGTCCTTAATCATAAATAATAGCC. Genotyping of the extracted genomic DNA

was performed using a TaqMan assay with the TIANtough Genotyping

qPCR PreMix (Probe) (TianGen, Guangzhou Z-ZHI Biotechnology). The

PCR protocol consisted of an initial denaturation at 95˚C for 10

min, followed by 45 cycles of 95˚C for 15 sec and 60˚C for 60

sec.

SNP-SNP interaction analysis

Interactions between SNP loci and their epistasis

were verified using the multifactor dimensionality reduction (MDR)

method using MDR software v3.0.2 (Laboratory of Computational

Genetics, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA;

available free of charge at http://www.epist asis.org). This method can identify

correlations in studies with a small sample size and low SNP

penetrance. Cross-validation consistency (CVC) and test accuracy

were used to determine the optimal interaction model. The optimal

model was the one with the highest CVC and test accuracy values.

Values of P<0.05 were considered to indicate statistically

significant differences.

Statistical analysis

The Chi-squared test was used to determine whether

there was a statistically significant difference in age between the

experimental and control groups. Logistic regression analysis was

used to calculate odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals

(CIs) to assess the association between METTL3 polymorphisms and

susceptibility to ovarian cancer, and age was corrected to avoid

the influence of confounding factors. Stratified analyses were

performed according to age, clinical stage, pregnancy outcomes and

immunohistochemistry results to investigate the association between

genotypes and susceptibility to ovarian cancer in each sub-stratum.

Haplotype analysis was performed using logistic regression

analysis, which was used to comprehensively evaluate the effect of

selected SNPs of the gene on susceptibility to ovarian cancer. The

goodness-of-fit test was used to determine whether the frequency

distribution of the genotypes of each SNP in the control group

satisfied the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE); a value of

P>0.05 was considered to indicate statistically significant

difference, which indicated that the SNP locus in the control group

complied with the HWE. The Gene-Tissue Expression (GTEx) portal

(https://www.gtexportal.org/home/) was

also used for expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) analysis to

predict potential associations between SNPs and gene expression

levels. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS 9.4 software

(SAS Institute Inc.

Results

Characteristics of the study

participants

Detailed information on the demographic and clinical

characteristics of the patients with ovarian cancer (n=244) and the

controls (n=276) is presented in Table

SI. There was no statistically significant difference in age

between the ovarian cancer and control groups (P=0.47).

Association of METTL3 gene

polymorphisms with susceptibility to ovarian cancer

Genotyping was performed on 244 patients and 276

control subjects. The association between METTL3 polymorphisms and

susceptibility to ovarian cancer is presented in Table I. None of the selected SNPs were

statistically different in HWE (P>0.05). First, single locus

analysis was performed which yielded the following results:

rs1263801 CC vs. GG: Adjusted OR, 0.480; 95% CI, 0.238-0.968;

P=0.0402; CC vs. GG/GC: Adjusted OR, 0.48; 95% CI, 0.246-0.966;

P=0.0395; rs1061027 CA vs. CC: Adjusted OR, 0.500; 95% CI,

0.331-0.754; P=0.001; CA/AA vs. CC: Adjusted OR, 0.629; 95% CI,

0.428-0.925; P=0.0185; rs1061026 TG vs. TT: Adjusted OR, 0.580; 95%

CI, 0.359-0.937; P=0.0262; TG/GG vs. TT: Adjusted OR, 0.0366; 95%

CI, 0.386-0.977; P=0.0395. Allelic variants reduced the risk of

developing ovarian cancer. However, rs1139130 was not associated

with the risk of developing ovarian cancer (Table I).

| Table ILogistic regression analysis of

associations between METTL3 polymorphisms and susceptibility to

ovarian cancer. |

Table I

Logistic regression analysis of

associations between METTL3 polymorphisms and susceptibility to

ovarian cancer.

| Genotype | Cases (n=244), n

(%) | Controls (n=276), n

(%) | P-valuea | Crude OR (95%

CI) | P-value | Adjusted OR (95%

CI) | P-valueb |

|---|

| rs1263801 G>C

(HWE=0.68) | | | | | | | |

|

GG | 124 (51.88) | 128 (47.58) | | 1 | | 1.00 | |

|

GC | 102 (42.68) | 113 (42.01) | | 0.945

(0.659-1.355) | 0.7568 | 0.944

(0.658-1.354) | 0.7552 |

|

CC | 13 (5.44) | 28 (10.41) | | 0.486

(0.241-0.979) | 0.0435 | 0.480

(0.238-0.968) | 0.0402 |

|

Additive | | | 0.1132 | 0.794

(0.602-1.047) | 0.1017 | 0.790

(0.599-1.042) | 0.0949 |

|

Dominant | 11 5(48.12) | 141 (52.42) | 0.3334 | 0.842

(0.594-1.193) | 0.3335 | 0.839

(0.592-1.189) | 0.3236 |

|

Recessive | 226 (94.56) | 241 (89.59) | 0.0401 | 0.495

(0.250-0.980) | 0.0435 | 0.488

(0.246-0.966) | 0.0395 |

| rs1139130 G>A

(HWE=0.55) | | | | | | | |

|

GG | 102 (43.22) | 206 (39.41) | | 1 | | 1 | |

|

GA | 101 (42.80) | 122 (45.35) | | 0.850

(0.586-1.234) | 0.3935 | 0.847

(0.583-1.229) | 0.3812 |

|

AA | 33 (13.98) | 41 (15.24) | | 0.827

(0.488-1.402) | 0.4805 | 0.819

(0.482-1.390) | 0.4592 |

|

Additive | | | 0.6817 | 0.901

(0.701-1.158) | 0.4157 | 0.895

(0.696-1.151) | 0.3875 |

|

Dominant | 134 (56.78) | 163 (60.59) | 0.3848 | 0.854

(0.599-1.219) | 0.3849 | 0.847

(0.594-1.210) | 0.3615 |

|

Recessive | 203 (86.02) | 228 (84.76) | 0.6899 | 0.904

(0.551-1.485) | 0.6908 | 0.895

(0.545-1.471) | 0.6622 |

| rs1061027 C>A

(HWE=0.45) | | | | | | | |

|

CC | 156 (71.89) | 167 (61.85) | | 1 | | 1 | |

|

CA | 47 (21.66) | 88 (32.59) | | 0.505

(0.335-0.761) | 0.0011 | 0.500

(0.331-0.754) | 0.001 |

|

AA | 14 (6.45) | 15 (5.56) | | 0.882

(0.414-1.882) | 0.7460 | 0.894

(0.419-1.090) | 0.7726 |

|

Additive | | | 0.0276 | 0.771

(0.569-1.046) | 0.0951 | 0.770

(0.567-1.045) | 0.0937 |

|

Dominant | 61 (28.11) | 103 (38.15) | 0.0198 | 0.634

(0.432-0.931) | 0.0202 | 0.629

(0.428-0.925) | 0.0185 |

|

Recessive | 203 (93.55) | 255 (94.44) | 0.6779 | 1.172

(0.553-2.4850) | 0.6782 | 1.195

(0.563-2.538) | 0.6424 |

| rs1061026 T>G

(HWE=0.31) | | | | | | | |

|

TT | 190 (84.82) | 208 (77.32) | | 1 | | 1 | |

|

TG | 31 (13.84) | 55 (20.45) | | 0.577

(0.357-0.932) | 0.0246 | 0.580

(0.359-0.937) | 0.0262 |

|

GG | 3 (1.34) | 6 (2.23) | | 0.512

(0.126-2.074) | 0.3482 | 0.502

(0.124-2.038) | 0.3352 |

|

Additive | | | 0.1085 | 0.652

(0.432-0.983) | 0.0414 | 0.653

(0.433-0.986) | 0.0426 |

|

Dominant | 34 (15.18) | 61 (22.68) | 0.0356 | 0.610

(0.384-0.970) | 0.0366 | 0.614

(0.386-0.977) | 0.0395 |

|

Recessive | 221 (98.66) | 263 (97.77) | 0.4618 | 0.595

(0.147-2.4070 | 0.4666 | 0.573

(0.141-2.323) | 0.4351 |

Stratified analysis

The rs1263801 allele variant reduced the incidence

of ovarian cancer in patients aged >51 years (adjusted OR,

0.398; 95% CI, 0.159-0.996; P=0.0489) (Table II).

| Table IIStratification analysis of METTL3

polymorphisms with susceptibility to ovarian cancer in rs1263801

G>C. |

Table II

Stratification analysis of METTL3

polymorphisms with susceptibility to ovarian cancer in rs1263801

G>C.

| | rs1263801 G>C

(cases/controls) | |

|---|

| Variables | GG/GC | CC | Adjusted

ORa (95% CI) |

P-valuea |

|---|

| Age, years | | | | |

|

≤51 | 108 | 6 | 0.641

(0.230-1.792) | 0.3969 |

|

>51 | 118 | 7 | 0.398

(0.159-0.996) | 0.0489 |

| Metastasis | | | | |

|

Yes | 81/241 | 4/28 | 0.403

(0.136-1.188) | 0.0993 |

|

No | 128/241 | 9/28 | 0.609

(0.279-1.331) | 0.2141 |

| Clinical stage | | | | |

|

1 | 46/241 | 5/28 | 0.982

(0.358-2.693) | 0.9717 |

|

2 | 41/241 | 2/28 | 0.437

(0.100-1.915) | 0.2722 |

|

3 | 76/241 | 3/28 | 0.325

(0.096-1.102) | 0.0712 |

|

4 | 20/241 | 1/28 | 0.407

(0.052-3.160) | 0.3897 |

| No. of times

pregnant | | | | |

|

≥3 | 92/241 | 5/28 | 0.449

(0.168-1.203) | 0.1113 |

|

<3 | 134/241 | 8/28 | 0.511

(0.226-1.155) | 0.1068 |

| Menopause | | | | |

|

Post-menopause | 146/241 | 9/28 | 0.476

(0.215-1.052) | 0.0665 |

|

Pre-menopause | 74/241 | 4/28 | 0.536

(0.176-1.632) | 0.272 |

| ER | | | | |

|

Low | 27/241 | 2/28 | 0.587

(0.131-2.618) | 0.4846 |

|

High | 60/241 | 3/28 | 0.437

(0.128-1.489) | 0.1859 |

| PR | | | | |

|

Low | 26/241 | 2/28 | 0.670

(0.150-2.990) | 0.5996 |

|

High | 35/242 | 2/28 | 0.507

(0.115-2.226) | 0.3679 |

| PAX8 | | | | |

|

Low | 26/241 | 2/28 | 0.654

(0.147-2.920) | 0.5783 |

|

High | 54/241 | 1/28 | 0.155

(0.021-1.163) | 0.0698 |

| WTI | | | | |

|

Low | 31/241 | 3/28 | 0.752

(0.214-2.646) | 0.6576 |

|

High | 71/241 | 2/28 | 0.236

(0.055-1.017) | 0.0526 |

| p16 | | | | |

|

Low | 37/241 | 3/28 | 0.765

(0.218-2.686) | 0.6759 |

|

High | 61/241 | 2/28 | 0.276

(0.064-1.193) | 0.0847 |

| Ki-67 | | | | |

|

Low | 36/241 | 2/28 | 0.506

(0.115-2.229) | 0.3683 |

|

High | 69/241 | 3/28 | 0.370

(0.109-1.256) | 0.1108 |

| Wild-type p53 | | | | |

|

Positive | 51/241 | 1/28 | 0.168

(0.022-1.267) | 0.0835 |

|

Negative | 166/241 | 11/28 | 0.559

(0.270-1.155) | 0.1164 |

| Mutant p53 | | | | |

|

Positive | 98/241 | 5/28 | 0.436

(0.163-1.163) | 0.0972 |

|

Negative | 119/241 | 7/28 | 0.492

(0.208-1.161) | 0.1054 |

For the rs1061027 gene polymorphism, compared with

the CC genotype, the CA/AA genotype reduced the risk of developing

ovarian cancer in patients aged ≤51 years (adjusted OR, 0.544; 95%

CI, 0.308-0.960; P=0.0357), in those without metastases (adjusted

OR, 0.576; 95% CI, 0.359-0.924; P=0.0222), those with clinical

stage III disease (adjusted OR, 0.542; 95% CI, 0.308-0.954;

P=0.0338), those who had been pregnant three times or more

(adjusted OR, 0.525; 95% CI, 0.305-0.903 P=0.0200), those at

post-menopause (adjusted OR, 0.578; 95% CI, 0.367-0.911; P=0.0182),

those who were estrogen receptor (ER) strongly positive (adjusted

OR, 0.517; 95% CI, 0.270-0.991; P=0.0470), progesterone receptor

(PR) weakly positive (adjusted OR, 0.297; 95% CI, 0.099-0.886;

P=0.0295), those who were weakly positive for paired box 8 (PAX8)

(adjusted OR, 0.281; 95% CI, 0.094-0.836; P=0.0225), weakly

positive for WT1 (adjusted OR, 0.368l 95% CI, 0.146-0.928;

P=0.0341), strongly positive for p16 (adjusted OR, 0.498; 95% CI,

0.255-0.972; P=0.0411), weakly positive for p16 (adjusted OR,

0.284; 95% CI, 0.106-0.761; P=0.0123), weakly positive for Ki-67

(adjusted OR, 0.196; 95% CI, 0.058-0.667; P=0.0091), wild-type

p53-negative (adjusted OR, 0.583; 95% CI, 0.378-0.900; P=0.0148)

and mutant p53-positive (adjusted OR, 0.560; 95% CI, 0.333-0.939,

P=0.0280) (Table III).

| Table IIIStratification analysis of METTL3

polymorphisms with susceptibility to ovarian cancer in rs1061027

C>A. |

Table III

Stratification analysis of METTL3

polymorphisms with susceptibility to ovarian cancer in rs1061027

C>A.

| | rs1061027 C>A

(cases/contorls) | |

|---|

| Variables | CC | CA/AA | Adjusted

ORa (95% CI) |

P-valuea |

|---|

| Age, years | | | | |

|

≤51 | 76/86 | 25/52 | 0.544

(0.308-0.960) | 0.0357 |

|

>51 | 80/81 | 36/51 | 0.715

(0.422-1.210) | 0.2114 |

| Metastasis | | | | |

|

Yes | 55/167 | 24/103 | 0.695

(0.405-1.194) | 0.1876 |

|

No | 90/167 | 32/103 | 0.576

(0.359-0.924) | 0.0222 |

| Clinical stage | | | | |

|

1 | 24/167 | 14/103 | 0.952

(0.470-1.931) | 0.8925 |

|

2 | 30/167 | 10/103 | 0.543

(0.255-1.157) | 0.1136 |

|

3 | 59/167 | 20/103 | 0.542

(0.308-0.954) | 0.0338 |

|

4 | 13/167 | 8/103 | 0.993

(0.397-2.482) | 0.9872 |

| No. of times

pregnant | | | | |

|

≥3 | 67/167 | 22/103 | 0.525

(0.305-0.903) | 0.0200 |

|

<3 | 89/167 | 39/103 | 0.709

(0.452-1.112) | 0.1343 |

| Menopause | | | | |

|

Post-menopause | 104/167 | 39/103 | 0.578

(0.367-0.911) | 0.0182 |

|

Pre-menopause | 48/167 | 20/103 | 0.676

(0.371-1.231) | 0.2002 |

| ER | | | | |

|

Low | 18/167 | 5/103 | 0.444

(0.160-1.237) | 0.1205 |

|

High | 44/167 | 14/103 | 0.517

(0.270-0.991) | 0.0470 |

| PR | | | | |

|

Low | 22/167 | 4/103 | 0.297

(0.099-0.886) | 0.0295 |

|

High | 26/167 | 10/103 | 0.627

(0.290-1.354) | 0.2345 |

| PAX8 | | | | |

|

Low | 23/167 | 4/103 | 0.281

(0.094-0.836) | 0.0225 |

|

High | 36/167 | 15/103 | 0.668

(0.348-1.281) | 0.2247 |

| WTI | | | | |

|

Low | 26/167 | 6/103 | 0.368

(0.146-0.928) | 0.0341 |

|

High | 48/167 | 18/103 | 0.598

(0.330-1.087) | 0.0915 |

| p16 | | | | |

|

Low | 28/167 | 5/103 | 0.284

(0.106-0.761) | 0.0123 |

|

High | 42/167 | 13/103 | 0.498

(0.255-0.972) | 0.0411 |

| Ki-67 | | | | |

|

Low | 25/167 | 3/103 | 0.196

(0.058-0.667) | 0.0091 |

|

High | 43/167 | 21/103 | 0.790

(0.444-1.406) | 0.4227 |

| Wild-type p53 | | | | |

|

Positive | 37/167 | 16/103 | 0.700

(0.370-1.323) | 0.2723 |

|

Negative | 114/167 | 41/103 | 0.583

(0.378-0.900) | 0.0148 |

| Mutant p53 | | | | |

|

Positive | 72/167 | 25/103 | 0.560

(0.333-0.939) | 0.0280 |

|

Negative | 79/167 | 32/103 | 0.655

(0.405-1.057) | 0.0834 |

For the rs1061026 gene polymorphism, the TG/GG

genotype reduced the risk of developing ovarian cancer compared

with the TT genotype in those with clinical staged stage I disease

(adjusted OR, 0.253; 95% CI, 0.075-0.850; P=0.0262), those at

post-menopause (adjusted OR, 0.548; 95% CI, 0.312-0.963; P=0.0366),

those who were weakly positive for Ki-67 (adjusted OR, 0.105; 95%

CI, 0.014-0.783; P=0.0279), those who were wild-type p53-negative

(adjusted OR, 0.455; 95% CI, 0.260-0.795; P=0.0057) and mutant

p53-negative (OR, 0.487; 95% CI, 0.264-0.898; P=0.0211) (Table IV).

| Table IVStratification analysis of METTL3

polymorphisms with susceptibility to ovarian cancer in rs1061026

T>G. |

Table IV

Stratification analysis of METTL3

polymorphisms with susceptibility to ovarian cancer in rs1061026

T>G.

| | rs1061026 T>G

(cases/controls) | |

|---|

| Variables | TT | TG/GG | Adjusted

ORa (95% CI) |

P-valuea |

|---|

| Age, years | | | | |

|

≤51 | 87/104 | 15/34 | 0.527

(0.270-1.032) | 0.0617 |

|

>51 | 103/104 | 19/27 | 0.711

(0.372-1.357) | 0.3006 |

| Metastasis | | | | |

|

Yes | 72/208 | 13/61 | 0.624

(0.323-1.204) | 0.1597 |

|

No | 105/208 | 18/61 | 0.585

(0.329-1.041) | 0.0684 |

| Clinical stage | | | | |

|

1 | 39/208 | 3/61 | 0.253

(0.075-0.850) | 0.0262 |

|

2 | 34/208 | 6/61 | 0.597

(0.239-1.490) | 0.2693 |

|

3 | 66/208 | 13/61 | 0.679

(0.351-1.314) | 0.2506 |

|

4 | 14/208 | 7/61 | 1.742

(0.671-4.527) | 0.2545 |

| No. of times

pregnan | | | | |

|

≥3 | 80/208 | 14/61 | 0.602

(0.318-1.137) | 0.1178 |

|

<3 | 110/208 | 20/61 | 0.625

(0.359-1.090) | 0.0979 |

| Menopause | | | | |

|

Post-menopause | 127/208 | 20/61 | 0.548

(0.312-0.963) | 0.0366 |

|

Pre-menopause | 29/208 | 12/61 | 0.634

(0.313-1.284) | 0.2058 |

| ER | | | | |

|

Low | 24/208 | 3/61 | 0.443

(0.129-1.528) | 0.1976 |

|

High | 48/208 | 10/61 | 0.708

(0.338-1.482) | 0.3592 |

| PR | | | | |

|

Low | 19/208 | 7/61 | 1.252

(0.502-3.119) | 0.6296 |

|

High | 31/208 | 5/61 | 0.541

(0.201-1.454) | 0.2233 |

| PAX8 | | | | |

|

Low | 33/208 | 5/61 | 0.743

(0.271-2.040) | 0.5646 |

|

High | 44/208 | 10/61 | 0.783

(0.372-1.650) | 0.5204 |

| WTI | | | | |

|

Low | 28/208 | 6/61 | 0.764

(0.301-1.939) | 0.5707 |

|

High | 57/208 | 11/61 | 0.667

(0.329-1.353) | 0.2621 |

| p16 | | | | |

|

Low | 29/208 | 5/61 | 0.610

(0.226-1.650) | 0.3307 |

|

High | 49/208 | 10/61 | 0.702

(0.335-1.469_ | 0.3473 |

| Ki-67 | | | | |

|

Low | 32/208 | 1/61 | 0.105

(0.014-0.783) | 0.0279 |

|

High | 54/208 | 12/61 | 0.765

(0.284-1.522) | 0.4447 |

| Wild-type p53 | | | | |

|

Positive | 39/208 | 13/61 |

1.135(0.569-2.264) | 0.7183 |

|

Negative | 144/208 | 19/61 |

0.455(0.260-0.795) | 0.0057 |

| Mutant p53 | | | | |

|

Positive | 77/208 | 17/61 | 0.761

(0.418-1.384) | 0.3707 |

|

Negative | 106/208 | 15/61 | 0.487

(0.264-0.898) | 0.0211 |

METTL3 haplotype analysis

Polymorphisms of rs1263801, rs1061027 and rs1061026

were selected for haplotype analysis, as demonstrated in Table V; haplotype GCT was used as a

control. It was found that the risk of developing ovarian cancer

was significantly reduced in subjects with haplotype CAT (adjusted

OR, 0.638; 95% CI, 0.434-0.940; P=0.023) and haplotype CAG

(adjusted OR, 0.285; 95% CI, 0.095-0.858; P=0.026).

| Table VAssociation between inferred

haplotypes of the METTL3 genes and the risk of developing ovarian

cancer. |

Table V

Association between inferred

haplotypes of the METTL3 genes and the risk of developing ovarian

cancer.

| Haplotypes | Cases (n=412), n

(%) | Controls (n=538), n

(%) | Crude OR (95%

CI) |

P-valuea | Adjusted OR (95%

CI) |

P-valueb |

|---|

| CT | 288 (69.90) | 352 (65.43) | 1.000 | | 1.000 | |

| CAT | 47 (11.41) | 89 (16.54) | 0.645

(0.439-0.950) | 0.026 | 0.638

(0.434-0.940) | 0.023 |

| CCG | 26 (6.31) | 43 (7.99) | 0.739

(0.443-1.232) | 0.246 | 0.748

(0.448-1.248) | 0.266 |

| CCT | 30 (7.28) | 20 (3.72) | 1.833

(1.019-3.297) | 0.043 | 1.796

(0.997-3.234) | 0.051 |

| GAT | 12 (2.91) | 10 (1.86) | 1.467

(0.625-3.444) | 0.379 | 1.454

(0.618-3.419) | 0.391 |

| CAG | 4 (0.97) | 17 (3.16) | 0.288

(0.096-0.864) | 0.026 | 0.285

(0.095-0.858) | 0.026 |

| GCG | 5 (1.21) | 5 (0.93) | 1.222

(0.350-4.263) | 0.753 | 1.141

(0.326-3.995) | 0.836 |

| GAG | 0 | 2 (0.37) | / | 0.980 | / | 0.981 |

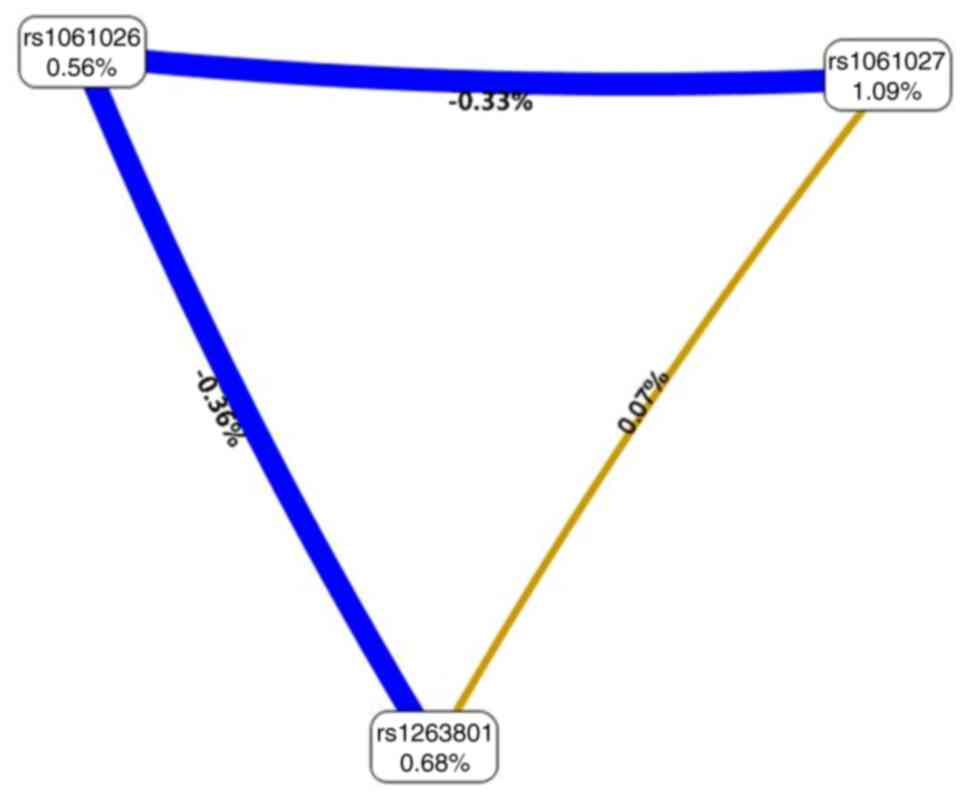

SNP-SNP interactions

The MDR analysis revealed that the CVC value of the

rs1061027 polymorphism as a single factor model in the METTL3 gene

was 10/10, with a testing accuracy of 0.5242, 95% CI, 0.4495-5.5072

and OR, 1.5734. The interaction models rs1263801 x rs1061027 and

rs1263801 x rs1061027 x rs1061026 were not statistically

significant (Table VI). The

interaction map revealed rs1061026 x rs1263801>rs1061026 x

rs1061027>rs1061027 x rs1263801 with negative entropy or

independence (0.36, 0.33 and 0.07%, respectively, indicated in blue

and yellow) (Fig. 1).

| Table VIOptimal multifactor dimensionality

reduction interaction models. |

Table VI

Optimal multifactor dimensionality

reduction interaction models.

| Locus number | Testing

accuracy | CVC | OR | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|

| rs1061027 | 0.5242 | 10/10 | 1.5734 |

(0.4495-5.5072) | 0.4769 |

| rs1263801,

rs1061027 | 0.4947 | 7/10 | 1.1874 |

(0.3455-4.0813) | 0.785 |

| rs1263801,

rs1061027, rs1061026 | 0.5813 | 10/10 | 1.7637 |

(0.5393-5.7677) | 0.346 |

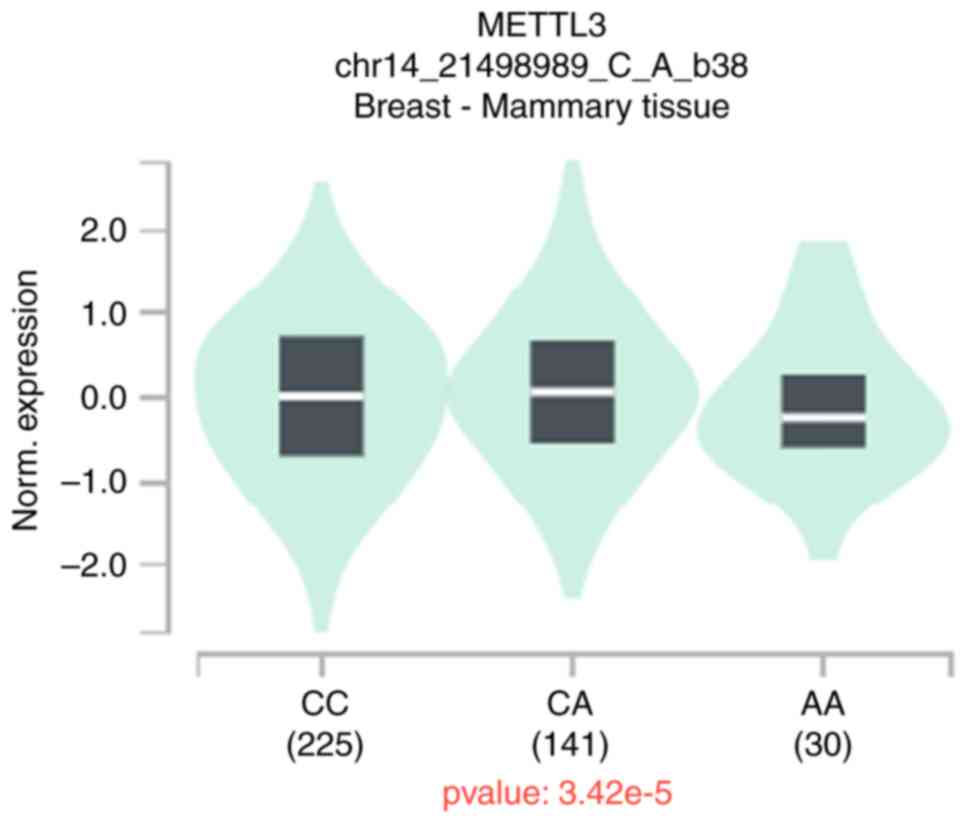

eQTL analysis

To further analyze the functional relevance of

rs1263801 G>C, rs1061027 C>A and rs1061026 T>G, eQTL

analysis was performed using data published by GTEx. The expression

of the appeal locus was not found in the patients with ovarian

cancer; however, it was found that patients with breast cancer who

carry the rs1061027 A genotype have a decreased expression of

METTL3 (Fig. 2).

Discussion

m6A has been reported to be involved in

the regulation of specific developmental processes in eukaryotes.

METTL3 with 580 amino acids is composed of a zinc finger structural

domain and a methyltransferase structural domain. When combined

with METTL14, METTL3 exerts methyltransferase activity and plays a

key role in cancer development as an oncogene or an oncogene

suppressor (13,14). It has been reported that mice

transplanted with ovarian cancer cells accompanied by

myeloid-specific METTL3 knockout exhibited increased tumor growth

(15). Moreover, it has been

reported that METTL3 targeting miR-1246 promotes the proliferation

and migration, and inhibits the apoptosis of ovarian cancer cells

(16). The silencing of METTL3

inhibits miR-126-5p to block the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway and inhibit

the development of ovarian cancer (17).

In the present multicenter large sample case-control

study, it was investigated whether METTL3 polymorphisms are

associated with the development of ovarian cancer. First, four SNPs

were screened, among which rs1263801 may affect the binding force

of transcription factors, rs1139130 is located at the splicing

site, and rs1061026 and rs1061027 are the binding sites of miRNAs

(12,18). The present study revealed that the

CC genotype of rs1263801 was a protective factor against ovarian

cancer and was closely related to the risk of developing ovarian

cancer in women aged >51 years. The CA genotype of rs1061027 was

also a protective factor for ovarian cancer, and the results

revealed that compared with the CC genotype, the prevalence of the

CA/AA genotype was lower in women aged <51 years, those who were

pregnant three times or more and those at post-menopause. The same

findings were found in patients with clinical stage III disease and

without metastasis. For rs1061026, it was found that the TG

genotype was associated with a reduced risk of developing ovarian

cancer. Further stratified analysis demonstrated that compared with

the TT genotype, the TG/GG genotype reduced the risk of ovarian

cancer in patients with clinical stage I disease and in

post-menopausal women.

Ki-67 suggests that proliferation is associated with

the prognosis of ovarian cancer (19). It has been reported that Ki-67 and

p53 expression are significantly elevated in ovarian cancer stages

III and IV compared with stages I and II (20). p53 mutations are the most common

mutated genes in ovarian cancer, the majority of which are missense

mutations, resulting in the loss of tumor suppressor function and

enhancing oncogenic function (21,22).

The present study demonstrated that the rs1061027 A

allele and rs1061026 G allele were protective factors against

ovarian cancer in women with a low Ki-67 expression and in

wild-type p53-negative women. However, as regards rs1061027, the

CA/AA genotype reduced the risk of ovarian cancer in mutant

p53-positive women compared with the CC genotype. As regards

rs1061026, the TG/GG genotype reduced the risk of developing

ovarian cancer in mutant p53-negative women compared with the TT

genotype.

PAX8 belongs to the paired-box gene family and plays

a role in tumor growth and participates in multiple oncogenic

pathways (23-25).

It has been reported PAX8 expression is higher in primary ovarian

cancer than in metastatic ovarian cancer; the downregulation of

PAX8 can decrease ovarian cancer cell migration and invasion,

leading to apoptosis (26). The

present study identified rs1061027A as a protective factor for

ovarian cancer in women with a low PAX8 expression.

The present study did not find an association

between rs1263801 G>C, rs1061027C>A and rs1061026 T>G with

METTL3 expression in ovarian tissues by analyzing the data released

by GTEx. Considering that ovarian and breast cancer share the same

cancer-related genes, such as BRCA1/2, p53, Ki-67, PKP3, CHEK2,

PALB2, and PVRL4 (27-29)

Furthermore, it was found that patients with breast cancer who

carry the rs1061027A genotype have a decreased expression of

METTL3; it was thus inferred that rs1061027 affected ovarian cancer

development by influencing the expression of METTL3. However,

further studies are required to confirm these finidngs.

The present study collected cases from three

hospitals; however, as a genetic polymorphism study, the sample

size remains relatively small. Ovarian cancer exhibits multiple

pathological subtypes, each with distinct mechanisms of onset and

prognosis. However, the present study did not standardize for

pathological subtypes. Despite the limitations of the present

study, it was found that METTL3 gene polymorphisms are associated

with susceptibility to ovarian cancer, and the three SNP loci of

the METTL3 gene are independent risk factors. The findings may

provide new insight for the early diagnosis of ovarian cancer.

Further studies are warranted however, to include more cases

meeting the inclusion criteria, classify pathological types and

conduct external validation.

Supplementary Material

Frequency distribution of selected

characteristics in OC cases and cancer-free controls.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: The present study was supported by the National College

Students Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program (grant

no. CX18024) and the Science and Technology Projects in Guangzhou

(grant no. 202102010134).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

SS and DJ designed the study. FL performed the

statistical analysis. LL and HW collected the clinical samples. SS

and DJ confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. DJ edited the

manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final version of

the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of

the First Affiliated Hospital of Jinan University (KY-2022-233),

the Ethics Committee of Guangzhou Medical University Women and

Children's Medical Center (117A01), and the Ethics Committee of

Shunde Hospital, Southern Medical University (KYLS20220903) and

written informed consent was obtained by all enrolled patients.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Torre LA, Trabert B, DeSantis CE, Miller

KD, Samimi G, Runowicz CD, Gaudet MM, Jemal A and Siegel RL:

Ovarian cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin. 68:284–296.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Cho KR and Shih I: Ovarian cancer. Annu

Rev Pathol. 4:287–313. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Zaccara S, Ries RJ and Jaffrey SR:

Reading, writing and erasing mRNA methylation. Nat Rev Mol Cell

Biol. 20:608–624. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Deng X, Su R, Weng H, Huang H, Li Z and

Chen J: RNA N6-methyladenosine modification in cancers:

Current status and perspectives. Cell Res. 28:507–517.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Zheng Q, Ma C, Ullah I, Hu K, Ma RJ, Zhang

N and Sun ZG: Roles of N6-methyladenosine demethylase FTO in

malignant tumors progression. Onco Targets Ther. 14:4837–4846.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Zhuo Z, Hua R, Chen Z, Zhu J, Wang M, Yang

Z, Zhang J, Li Y, Li L, Li S, et al: WTAP gene variants confer

hepatoblastoma susceptibility: A Seven-center Case-control study.

Mol Ther Oncolytics. 18:118–125. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Wang X, Guan D, Wang D, Liu H, Wu Y, Gong

W, Du M, Chu H, Qian J and Zhang Z: Genetic variants in

m6A regulators are associated with gastric cancer risk.

Arch Toxicol. 95:1081–1098. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Ying P, Li Y, Yang N, Wang X, Wang H, He

H, Li B, Peng X, Zou D, Zhu Y, et al: Identification of genetic

variants in m6A modification genes associated with

pancreatic cancer risk in the Chinese population. Arch Toxicol.

95:1117–1128. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Lv J, Song Q, Bai K, Han J, Yu H, Li K,

Zhuang J, Yang X, Yang H and Lu Q: N6-methyladenosine-related

single-nucleotide polymorphism analyses identify oncogene RNFT2 in

bladder cancer. Cancer Cell Int. 22(301)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Bian J, Zhuo Z, Zhu J, Yang Z, Jiao Z, Li

Y, Cheng J, Zhou H, Li S, Li L, et al: Association between METTL3

gene polymorphisms and neuroblastoma susceptibility: A nine-centre

case-control study. J Cell Mol Med. 24:9280–9286. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Lin A, Zhou M, Hua RX, Zhang J, Zhou H, Li

S, Cheng J, Xia H, Fu W and He J: METTL3 polymorphisms and Wilms

tumor susceptibility in Chinese children: A five-center

case-control study. J Gene Med. 22(e3255)2020.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Chen H, Duan F, Wang M, Zhu J, Zhang J,

Cheng J, Li L, Li S, Li Y, Yang Z, et al: Polymorphisms in METTL3

gene and hepatoblastoma risk in Chinese children: A seven-center

case-control study. Gene. 800(145834)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Zeng C, Huang W, Li Y and Weng H: Roles of

METTL3 in cancer: Mechanisms and therapeutic targeting. J Hematol

Oncol. 13(117)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Xu Y, Song M, Hong Z, Chen W, Zhang Q,

Zhou J, Yang C, He Z, Yu J, Peng X, et al: The N6-methyladenosine

METTL3 regulates tumorigenesis and glycolysis by mediating m6A

methylation of the tumor suppressor LATS1 in breast cancer. J Exp

Clin Cancer Res. 42(10)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Wang J, Ling D, Shi L, Li H, Peng M, Wen

H, Liu T, Liang R, Lin Y, Wei L, et al: METTL3-mediated m6A

methylation regulates ovarian cancer progression by recruiting

myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Cell Biosci.

13(202)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Bi X, Lv X, Liu D, Guo H, Yao G, Wang L,

Liang X and Yang Y: METTL3 promotes the initiation and metastasis

of ovarian cancer by inhibiting CCNG2 expression via promoting the

maturation of pri-microRNA-1246. Cell Death Discov.

7(237)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Bi X, Lv X, Liu D, Guo H, Yao G, Wang L,

Liang X and Yang Y: METTL3-mediated maturation of miR-126-5p

promotes ovarian cancer progression via PTEN-mediated PI3K/Akt/mTOR

pathway. Cancer Gene Ther. 28:335–349. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Xu Z and Taylor JA: SNPinfo: Integrating

GWAS and candidate gene information into functional SNP selection

for genetic association studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 37:W600–W605.

2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Kucukgoz Gulec U, Gumurdulu D, Guzel AB,

Paydas S, Seydaoglu G, Acikalin A, Khatib G, Zeren H, Vardar MA and

Altintas A: Prognostic importance of survivin, Ki-67, and

topoisomerase IIα in ovarian carcinoma. Arch Gynecol Obstet.

289:393–398. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Harlozinska A, Bar JK, Sedlaczek P and

Gerber J: Expression of p53 protein and Ki-67 reactivity in ovarian

neoplasms. Correlation with histopathology. Am J Clin Pathol.

105:334–340. 1996.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Walerych D, Napoli M, Collavin L and Del

Sal G: The rebel angel: Mutant p53 as the driving oncogene in

breast cancer. Carcinogenesis. 33:2007–2017. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Walerych D, Lisek K and Del Sal G:

Multi-omics reveals global effects of mutant p53 gain-of-function.

Cell Cycle. 15:3009–3010. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Chaves-Moreira D, Morin PJ and Drapkin R:

Unraveling the mysteries of PAX8 in reproductive tract cancers.

Cancer Res. 81:806–810. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Di Palma T and Zannini M: PAX8 as a

potential target for ovarian cancer: What We Know so Far. Onco

Targets Ther. 15:1273–1280. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Zhou Q, Li H, Cheng Y, Ma X, Tang S and

Tang C: Pax-8: Molecular biology, pathophysiology, and potential

pathogenesis. Biofactors. 50:408–421. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Kim J, Kim NY, Pyo J, Min K and Kang D:

Diagnostic roles of PAX8 immunohistochemistry in ovarian tumors.

Pathol Res Pract. 250(154822)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Zhang Y, Chen J, Tian J, Zhou Y and Liu Y:

Role and function of plakophilin 3 in cancer progression and skin

disease. Cancer Sci. 115:17–23. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Infante M, Arranz-Ledo M, Lastra E,

Olaverri A, Ferreira R, Orozco M, Hernández L, Martínez N and Durán

M: Profiling of the genetic features of patients with breast,

ovarian, colorectal and extracolonic cancers: Association to CHEK2

and PALB2 germline mutations. Clin Chim Acta.

552(117695)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Nanamiya T, Takane K, Yamaguchi K, Okawara

Y, Arakawa M, Saku A, Ikenoue T, Fujiyuki T, Yoneda M, Kai C and

Furukawa Y: Expression of PVRL4, a molecular target for cancer

treatment, is transcriptionally regulated by FOS. Oncol Rep.

51(17)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|