Introduction

Patients are becoming more educated regarding their

health care and studies have shown that both diet and ethnicity

with genetic variants influence cardiovascular disease (CVD)

development (1-4).

Since CVD is considered the leading cause of mortality worldwide,

preventing, reducing and lessening the development of the disease

is critical for improving mortality and morbidity rates (5). Lifestyle and daily diet vary

considerably between countries and continents, and this has been

shown to affect the development of CVD (6-11).

Patients who are aware of this wish to know what effect they will

have from a certain treatment, medicine or lifestyle change. From a

medical professional point of view, it is crucial to have

information on whether a recommended treatment or lifestyle change

will be effective for an individual patient. Variations in the

effects of drugs between patients have been observed and even more

will be discovered in the future (12,13).

From a health-care planning perspective, finances can be

distributed more accurately there is available knowledge on whether

a patient will experience the desired effect of a drug considered

for prescription. Personalized medicine is currently being more

commonly requested by patients, medical professionals and

politicians.

Garlic (Allium sativum L.) has played a

paramount role in traditional medicine, dating back to the ancient

Egyptians. Garlic extracts have been shown to increase nitric oxide

synthase activity, a critical part of vascular function and

angiogenesis (14). Aged garlic

extract (AGE), a garlic supplement, contains a number of active

ingredients, one of these being S-allylcysteine (SAC) (15). SAC has antioxidant properties, it

prevents lipid and protein oxidation, and is the most extensively

studied component of AGE (16-18).

Ahmadi et al (19)

demonstrated that AGE was associated with a reduction in the levels

of an inflammatory biomarker, a lack of progression of coronary

artery calcification (CAC) and with increased vascular function. In

their studies, Budoff et al (20-22)

also demonstrated an association of AGE with a favorable

improvement in oxidative biomarkers, vascular function and the

reduced progression of atherosclerosis measured by CAC progression.

Steiner et al (23)

revealed that AGE exerted a beneficial effect on lipid profiles and

blood pressure. The authors have previously demonstrated an

association between AGE and improved microcirculation, a decrease

in blood pressure and a positive effect on inflammatory biomarkers

(24-26).

A method for predicting the outcome of various drugs

and medical treatments is known as data mining. It is performed by

analyzing large blocks of information and trying to find patterns,

similarities or trends. Translating a large set of data to a trend

or a new-found pattern can make the data easier to interpret and

lead to new and useful information. The method is based on

combining visualization of diagrams and different algorithms to

finding patterns or trends. There are two starting positions,

either driven by subject-specific information and hypotheses using

data mining to confirm the theory or using data mining to generate

data-driven hypotheses. These two approaches should be combined to

avoid flawed conclusions. Probably the most well-known approach is

the cross-industry standard process for data mining (CRISP-DM)

(27-29).

Using this method and approach, the authors previously developed an

algorithm for predicting which patient will have a more favorable

effect on CAC scores and blood pressure following the intake of AGE

capsules (25). The AGE algorithm

was developed using a European cohort. The aim of the present study

was to validate the method of constructing an algorithm for

prediction of which patient will have a more favorable effect of

AGE on CAC and systolic blood pressure (SBP) using data accumulated

in the USA.

Materials and methods

Study outcome

The primary objective was to validate a method for

developing a predictive model with the aim of identifying patients

who would have a more favorable effect of AGE on CAC and SBP after

12 months of AGE intake.

Study population

The data of the patients in the present study were

collected from five previously published studies. Of these studies,

one study was completed in Sweden on a European cohort (25) and four studies were completed in

the USA (20,30-32).

All patients in these studies had an increased risk of developing

CVD. The Swedish cohort was used solely for the initial model

development in the previous study by the authors (25) and was not included in the model

training, testing, or analysis in the present validation study. The

present study exclusively applied the developed method to an

independent US patient cohort to assess external model performance

(n=78). In the studies examined, all patients were sent for a

cardiac computed tomography (CT) for the definition of the CAC

score, blood pressure was measured, and blood samples were

collected and analyzed using standard techniques in the beginning

of the study, at 0 months and after 12 months. All patients were

administered AGE (Kyolic; Wakunaga of America Co. Ltd.) daily for

the duration of 12 months. Upon receiving the data from the studies

in the USA, the inclusion and exclusion criteria from the Swedish

study were applied; hence, patients with a CAC score >1,000, CAC

score <1 and a body mass index (BMI) >40 in the USA cohort

were excluded. Further details and baseline values of the cohorts

are presented in Table I. More

detailed information about the study populations is available in

the previously published studies (20,25,30-32).

| Table IBaseline data of all the patients

included in the study. |

Table I

Baseline data of all the patients

included in the study.

| | Sweden (n=46) | USA (n=78) | |

|---|

| Parameter | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | P-value |

|---|

| Age (years) | 64.4 | 6.4 | 59.9 | 8.7 | <0.05 |

| BMI | 27.6 | 3.7 | 27.9 | 4.0 | 0.653 |

| CAC | 207.3 | 237.7 | 194.7 | 213.8 | 0.761 |

| CRP

(mg/l)a | 2.2 | 3.6 | 1.0 | 1.4 | <0.05 |

| Triglycerides

(mmol/l) | 1.4 | 0.7 | 1.3 | 0.7 | 0.758 |

| Cholesterol

(mmol/l) | 5.2 | 1.3 | 4.6 | 1.2 | <0.05 |

| HDL (mmol/l) | 1.6 | 0.5 | 1.3 | 0.4 | <0.05 |

| LDL (mmol/l) | 3.4 | 1.1 | 2.7 | 1.0 | <0.05 |

| Il-6

(ng/l)a | 4.5 | 3.7 | 2.0 | 1.6 | <0.05 |

| Homocysteine

(µmol/l)a | 13.4 | 3.8 | 10.7 | 2.4 | <0.05 |

| DBP | 88 | 9 | 82 | 10 | <0.05 |

| SBP | 148 | 19 | 135 | 15 | <0.05 |

Development of the AGE algorithm

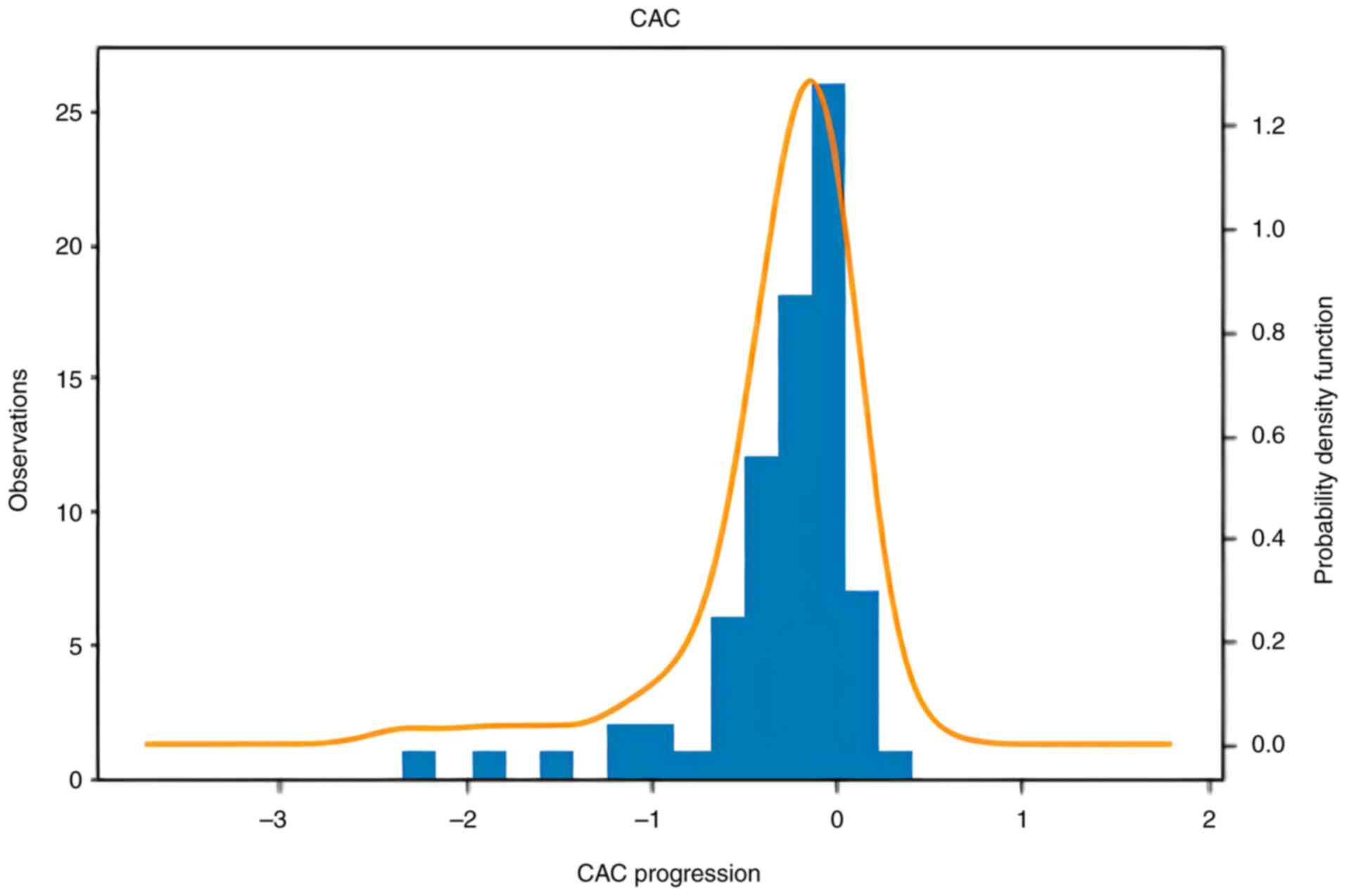

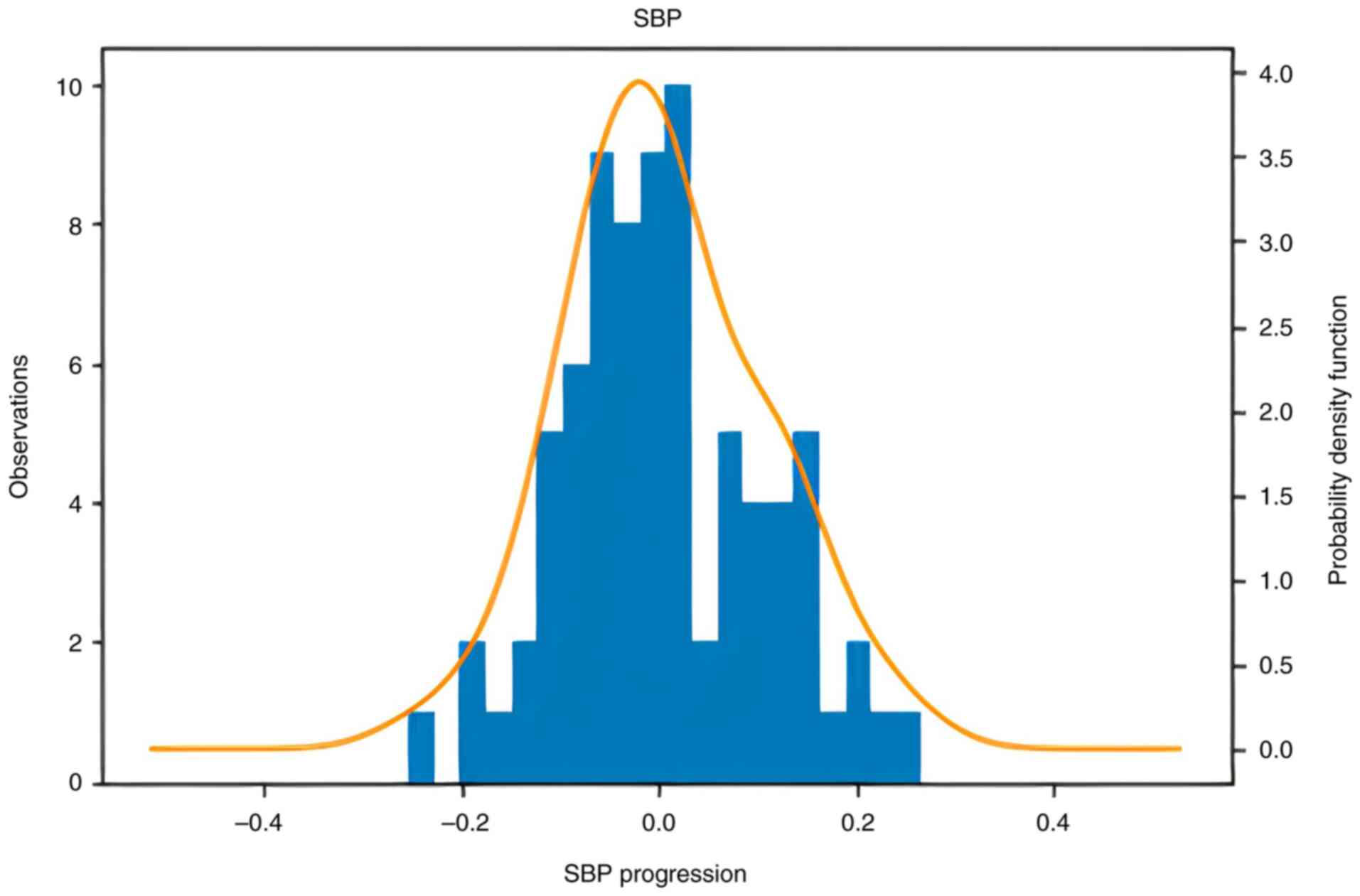

The AGE algorithm developed in the Swedish study was

created using CRISP-DM (25,28).

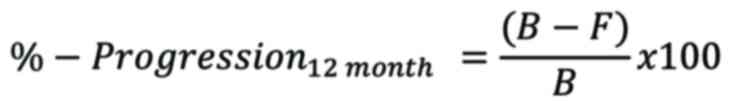

The target variables, i.e., the progression of CAC and SBP, were

created using the measured progression of CAC and SBP following 12

months of treatment with AGE. Information of the distribution of

the progression of CAC and SBP is presented in Figs. 1 and 2. The formula used for measuring the

progression for each target variable was the following:

where ‘B’ represents the baseline measure at the

start of the study and ‘F’ represents the follow-up measure after

12 months of AGE supplementation. To validate the developed method

of engineering an algorithm, new data were acquired from the USA.

The patients in the USA cohort were divided into two groups by the

median, depending on the amount of progression of the target

variables. Patients with a CAC progression larger than the median

were assigned the value 0 and patients with a CAC progression below

the median were assigned the value 1. Patients with a decrease in

SBP larger than the median were assigned the value 1 and the

remainder were assigned the value 0. As a result, 50% of the

patients who benefited most from AGE supplement treatment were

assigned the value 1 and the remainder were assigned the value

0.

Preprocessing and predictor

variables

The following parameters functioned as predictor

variables in the modeling phase: Sex, age, BMI, CAC, cholesterol,

SBP, diastolic blood pressure (DBP), high-density lipoprotein

(HDL), low-density lipoprotein (LDL), homocysteine, interleukin-6

(IL-6), triglycerides and C-reactive protein (CRP). The categorical

variable ‘sex’ was encoded, converting each sex category to 1=male

and 0=female. All parameters were measured at baseline, i.e., at 0

months. In the USA cohort there are missing values of CRP (n=38),

Il-6 (n=41) and homocysteine (n=19). These were completed with the

mean value of the remainder of the cohort for each of the

variables. In the machine-learning algorithm, variables function as

features and were measured ones, i.e. blood samples, clinical

measurements, such as blood pressure, as well as generated ones

from the previously mentioned studies (20,25,30-32).

This was achieved by the addition of polynomial features of the

second-degree and interaction features to capture both non-linear

effects and interactions. Interactions are variables that are

multiplied with other variables and second-degree polynomials are

squared variables. At the end of the preprocessing step the new set

of predictor variables, a total of 105, including the added

features, were standardized. This feature scaling was performed for

the modeling phase in order for the regularization, loss of

function, in the logistic regression to function correctly.

Modeling: Feature selection and

parameter tuning

Following the preprocessing step, the initial

predictor model set consisted of an algorithm with blanks for the

variables. In order to both optimize for the model accuracy and to

reduce overfitting, a feature selection step was performed. The

selected feature selection function was recursive feature

elimination (RFE). This searches for a subset of features by

starting with all features in the training set and removing

features until the desired number remains. RFE functions as a

‘wrapper’ by fitting the given machine-learning algorithm used in

the core of the model, in this case, logistic regression, ranking

features by importance, discarding the least important features and

re-fitting the model. The process is repeated until a specified

number of features remains. Following the feature selection step, a

grid search is performed to optimize for the tuning of the

developed model by searching over a set of hyperparameter settings.

The results from the feature selection and grid search step are

presented in Table II for CAC and

in Table III for SBP.

| Table IIIncluded features of the CAC

model. |

Table II

Included features of the CAC

model.

| Coefficients | Predictor variables

after RFE for CAC |

|---|

| 3.08 | LDL |

| 1.69 | Ses x

cholesterol |

| -2.05 | Sex x SBP |

| -1.17 | Age x TG |

| -0.95 | BMI x LDL |

| -1.31 | CAC2 |

| 1.73 | CAC x

homocysteine |

| -3.83 | Cholesterol x

LDL |

| 2.75 | Cholesterol x

TG |

| 1.93 | IL-6 x SBP |

| -2.09 | IL-6 x TG |

| 0.12 | LDL2 |

| Table IIIIncluded features SBP model. |

Table III

Included features SBP model.

| Coefficients | Predictor variables

from RFE for SBP |

|---|

| -1.98 | Sex x DBP |

| 2.08 | Sex x HDL |

| -1.69 | Age x IL-6 |

| 1.55 | Age x CRP |

| 1.41 | CAC x IL-6 |

| -1.77 | CAC x CRP |

| 1.29 | DBP2 |

| -3.30 | HDL x SBP |

| 6.93 | HDL x CRP |

| 1.44 | Homocysteine x

IL-6 |

| -2.41 | LDL x CRP |

| -10.25 | CRP2 |

Validation of the prediction

model

Leave-one-out cross validation (LOOCV), was selected

as the validation approach. It provides an estimate as to how the

algorithm will perform on unseen data. LOOCV is performed by

training and testing the algorithm on the N-1 patient, N

representing the total number of patients in the cohort, and a

prediction is made for the excluded patient using the parameters of

that patient. This process is repeated until all observations have

been tested (a visualization of the method is presented in Table IV). When the prediction model was

tested on all 78 patients, a mean key performance indicator score

from all tests was obtained.

| Table IVValidation. |

Table IV

Validation.

| | Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | … | Patient 77 | Patient 78 |

|---|

| Model 1 | Train | Train | Train | … | Train | Test |

| Model 2 | Train | Train | Train | … | Test | Train |

| Model 3 | Train | Train | Train | … | Train | Train |

| … | … | … | … | … | … | … |

| Model 77 | Train | Test | Train | … | Train | Train |

| Model 78 | Test | Train | Train | … | Train | Train |

Statistical analyses

The models were created in Python 3.9.0 (Van Rossum,

G. & Drake, F.L., 2009. Python 3 Reference Manual, Scotts

Valley, CA: CreateSpace) utilizing the following listed libraries:

scikit-learn (version 0.23.2) (https://pypi.org/project/scikit-learn/0.23.2/), Pandas

(1.1.3) (https://pypi.org/project/pandas/1.1.3/) and NumPy

(1.19.2) (https://pypi.org/project/numpy/1.19.2/). All

continuous data are presented as the mean ± SD. The Student's

t-test was used to assess differences between groups. A value of

P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

In a previously published article by the authors, we

developed the AGE algorithm on 46 patients in the Swedish cohort.

To validate the method of developing the AGE algorithm in the

present study, data from four studies were retrieved, performed in

the USA, termed the USA cohort. The USA cohort consisted of a total

of 78 patients who received AGE who were included in the present

study. Following the aforementioned developmental steps of the

prediction model, the model was validated using LOOCV. For each of

the 78 subjects in the dataset, the authors computed the estimated

probability of the i:th subject being in the 50th percentile with

the optimal progression following 12 months of AGE supplement

treatment. i:th represents the subject who is being tested on among

the N observations. The following mean modeling key performance

indicators were provided by the LOOCV: CAC: Accuracy, 65%;

precision, 64%; recall, 69%; and SBP: Accuracy, 65%; precision,

66%; recall, 64% (Table V). In

total, 12 features were selected to be in the model for sufficient

accuracy, but to reduce overfitting. For CAC, the 12 features were

the following: LDL, sex x cholesterol, sex x SBP, age x

triglycerides (TG), BMI x LDL, CAC2, CAC x homocysteine,

cholesterol x LDL, cholesterol x TG, Il-6 x SBP, IL-6 x SBP, IL-6 x

TG and LDL2. An overview and each feature of the associated

coefficient are provided in Table

II. For SBP the 12 features were the following: Sex x DBP, sex

x HDL, age x IL-6, age x CRP, CAC x IL-6, CAC x CRP, DBP2, HDL x

SBP, HDL x CRP, homocysteine x IL-6, LDL x CRP and CRP2. An

overview and each feature of the associated coefficient are

provided in Table III.

| Table VPerformance metrics. |

Table V

Performance metrics.

| Algorithm | Accuracy (%) | Precision (%) | Recall (%) |

|---|

| CAC algorithm | 65 | 64 | 69 |

| SBP algorithm | 65 | 66 | 64 |

Discussion

The terms ‘personalized medicine’, ‘precision

medicine’ and ‘stratified medicine’ are all used to describe the

same concept. The majority of articles, reports and researchers use

these terms interchangeably. The concept is to customize and tailor

medical treatments, drugs and recommendations to each individual

patient depending on the predicted response or risk of disease.

Personalized medicine often uses diagnostic testing with molecular

or cellular analysis to allocate patients to groups. In one aspect

of personalized medicine, pharmacogenomics or pharmacogenetics, the

genetic information of an individual is used to tailor medical

treatments. Although this may appear as a very modern approach,

medical professionals have been making decisions such as these for

decades. It is well established that a number of diseases have a

large hereditary component and patients are questioned about this

for the purpose of determining whether they have a smaller or

larger risk of developing a certain disease or condition. The

medical professional then reaches a decision based on this

information, prescribing the recommended medicine as

‘one-size-fits-all’, meaning that the majority of patients are then

prescribed the same drug and dose. The decision behind this is that

the majority of studies are based on broad population averages.

However, not many patients fit into this description and numerous

drugs will not function in the same manner for everyone. The

majority of drugs are also prescribed along the basis of ‘trial and

error’. Treatment begins with the most common and popular drug and

then in the case that the patient develops side-effects or does not

respond in as expected, the drug is changed to the second drug of

choice on the list for that condition. This often results in

frustrated patients and tired doctors. The notion behind

personalized medicine is to avoid this waste of time and money by

selecting the right medicine or recommendation to start with.

The present study used this notion to create an

algorithm that could be applied to patients who wish to know

whether AGE will have a positive effect on their health. As

described previously, patients with diverse lifestyles, certain

genes and diets respond differently to drugs and dietary

supplements (1-4,6-11).

The authors have previously studied patients who are at an

intermediate-to-high risk of developing cardiovascular events and

created an algorithm, the AGE algorithm, to predict the effects of

AGE on CAC progression and blood pressure of an individual

(25). The algorithm is based on

the CAC score, blood lipids and blood pressure and could predict,

with 80% precision, which patient will have a significantly reduced

CAC progression after 12 months of AGE supplement (25). The same type of algorithm, the one

developed in the present study, could predict with a 64% precision

score, which patients will have a significantly reduced CAC

progression after 12 months of AGE supplementation. The algorithm

could predict with a 66% precision score which patients will have a

significant reduction in blood pressure after 12 months of AGE

supplementation. Unlike existing cardiovascular risk calculators,

such as the Framingham Risk Score (https://www.mdcalc.com/calc/38/framingham-risk-score-hard-coronary-heart-disease)

or the ASCVD Risk Estimator (https://www.mdcalc.com/calc/3398/ascvd-atherosclerotic-cardiovascular-disease-2013-risk-calculator-aha-acc),

which predict the likelihood of future cardiovascular events based

on broad population data, the model used herein is specifically

designed to predict individual patient response to a defined

intervention, AGE supplementation. While previous studies have

demonstrated average cohort-level effects of AGE, to the best of

our knowledge, no previous study to date has developed or validated

a personalized prediction tool estimating individual treatment

responses (33,34). By applying data science

methodologies incorporating interaction terms and non-linear

relationships, this model represents a novel, practical step toward

personalized, supplement-based cardiovascular prevention. The

algorithm demonstrated a precision of 64% for CAC and 66% for SBP,

which is notable given the modest sample size. To the best of our

knowledge, this is the first externally validated prediction tool

tailored to identify which patients are most likely to benefit from

AGE, providing a novel contribution to precision prevention

strategies in cardiovascular care. It is clear there is a potential

in predicting which patients would benefit the most from AGE

supplement treatment using a limited sample (25). Therefore, further validation of the

method of developing the algorithm on another cohort is required to

broaden the concept of using it in day-to-day medical consultations

with patients interested in dietary supplements.

When developing the model, a combination of

variables and engineered features was made available for the model

to use. A balance between model complexity and performance was

sought to maintain the number of features to a minimum, to avoid

overfitting and increase model stability. Initially, a model with

10% of the available features was tested, i.e., 10 out of 105

features in total. The model was performing well; however, a model

with an additional two features was tested, which was found to

outperform the model with 10 features. As a result, a model with 12

features was selected as the final model. Logistic regression was

selected for its interpretability and suitability for binary

outcomes in clinical applications. While other machine learning

methods could be used, logistic regression provided a practical

balance of transparency and predictive performance, particularly in

a limited sample size.

Overall, the models generalized well on the test

data. When selecting the validation method, 10-fold cross

validation was explored; however, it was deemed to be too sensitive

to the random sampling effect when creating the folds. It is

important to realize that in a 10-fold cross validation, 10% of the

sample is used as test, while only having 78 patients, the test

fold consists of only 8 patients. With a limited sample size, the

probability of a test set being skewed is high. LOOCV is a reliable

method that produces an unbiased estimate of the performance of a

model, and it is recommended that it is used in situations where

data are limited. Although LOOCV is computationally expensive, the

limited number of observations render the computational cost

negligible. Therefore, with limited data, the random sampling

effects using 10-fold cross validation, limiting bias and enabling

testing on unseen data renders it the optimal validation method to

use.

As aforementioned, the prediction model performs

better on unseen data, i.e., the more data it is used on.

Generally, the effect from the amount of study data available can

be broken down into two parts. First, the negative random effect on

the partitioning of data into training sets and test sets

diminishes the more data is available, i.e., the representativity

of both the training and test set increases. Second, more data

allow for the addition of more categorical predictor features to

the modeling phase. Increased clinical information, such as

lifestyle, certain genes and dietary intake in categorical form

would increase the performance of the model. This is due to the

fact that a model is built on a sample with a higher variance,

i.e., a larger sample, which results in a model with an intrinsic

ability to generalize more effectively on unseen data. Overall, the

present study indicates the feasibility of developing predictive

models classifying patients into who would have the best results

from the AGE supplement or not. This predictive modeling framework

could also be applied to other areas of biomedical research. Recent

advances in AI-driven treatment prediction, organ-on-a-chip

platforms for drug screening, engineered cardiac organoids for

cardiovascular disease modeling and artificial vascular graft

technologies illustrate the expanding opportunities for integrating

predictive models into precision medicine and translational

cardiovascular research (35-38).

It is important to note that baseline differences

between the Swedish and USA cohorts, particularly in age, LDL and

SBP, could influence model performance across populations. Although

the model incorporated interaction terms and non-linear features to

account for these variations, further validation in larger, more

diverse cohorts will be necessary to confirm broader applicability.

The observed decline in model performance when applied to the USA

cohort is likely explained by differences in baseline variable

distributions, particularly in age, LDL, SBP and CAC scores, which

can alter predictor-outcome relationships. Additionally, as feature

selection was based on the Swedish cohort, the relative importance

of certain variables and interactions may have differed in the USA

population, contributing to reduced accuracy and precision. These

findings highlight the importance of accounting for

population-specific variability in model transportability and

support the need for broader validation in diverse clinical

populations.

The requirements of gathering data to assess who

would benefit the most from AGE supplement treatment are not high:

ordinary blood tests and a CT scan can be utilized to gather the

necessary variables. However, further studies, tests and modeling

are necessary before a model can be used to assess which patient

will have a favorable effect of AGE supplement treatment or

not.

The present study had certain limitations which

should be mentioned. The data in the present study were acquired

from four studies performed previously. Given the variation in

collected variables and the limited number of patients, these could

potentially affect the scores. Furthermore, the relatively small

sample size, with 46 patients in the initial model and 78 in the

validation cohort, may limit the power of the model and increase

the risk of overfitting despite the use of recursive feature

elimination and leave-one-out cross-validation. Thus, larger,

prospective studies are warranted to further validate and improve

the predictive accuracy and generalizability of the model. A larger

study cohort would probably reduce the random effect of

within-group variation. CAC progression was defined as the absolute

change in CAC. A potential site variation in regard to different

brands of the CT scan itself and the analyzing software might also

inflict some variations. The interpreting radiologist differed,

which could be observed as a variance of weakness, but also a

strength. The serum level of SAC was not measured to ensure patient

compliance in the studies. All patients were advised not to change

their lifestyle and diet apart from taking the AGE capsules;

however, studies have indicated that patients enrolled in studies

are more likely to adopt lifestyle changes (39,40).

The lifestyle changes were not assessed formally to evaluate the

effect on the endpoint. A randomized trial of diet and lifestyle

would be needed to better assess these potential interventions.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrates that

it is possible and realistic to develop predictive models,

classifying patients into who would have the optimal results from

AGE supplement treatment or not. The algorithm was able to predict

with 64% precision which patient would have a significant reduction

of CAC progression using the AGE supplement. With the same type of

model, we could also predict with 66% precision which patient would

have a significant blood pressure-lowering effect using the AGE

supplement.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the statistical

engineers, Mr. Andreas Timglas (Securitas Security Services, New

Jersey, USA) and Mr. Roy Ollila (Fanwl Consulting, Bjärred, Sweden)

for assisting with the development of the prediction model.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

MW, MJB, EB and SL conceptualized the study and were

involved in the study methodology. MW and SL were involved in data

validation. MW, MM and SL were involved in the formal analysis. AK,

MJB and MW were involved in the investigative aspects of the study.

SL provided monetary and material resources. AK, MJB and MW were

involved in data curation. MW, EB, MM and SL were involved in the

writing and preparation of the original draft of the manuscript. EB

and SL were involved in writing, review and editing the manuscript.

MW and EB were involved in preparation of figures. SL supervised

the study and was involved in project administration. All authors

have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. SL

and MW confirm the authenticity of all the raw data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was based on aggregated data from

previously published studies (20,25,30-32).

The previously published studies have all been approved by ethical

boards, and further details are described in the individual

published studies (20,25,30-32).

No individual level data were accessed at any step in the analysis,

and no indirect identification of the study subjects was possible;

additional ethical vetting was not applicable for the present

study.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Brown AW, Kaiser KA, Keitt A, Fontaine K,

Gibson M, Gower BA, Shikany JM, Vorland CJ, Beitz DC, Bier DM, et

al: Science dialogue mapping of knowledge and knowledge gaps

related to the effects of dairy intake on human cardiovascular

health and disease. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 61:179–195.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Astrup A: Yogurt and dairy product

consumption to prevent cardiometabolic diseases: Epidemiologic and

experimental studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 99 (5 Suppl):1235S–1242S.

2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Diaz-Lopez A, Bullo M, Martinez-Gonzalez

MA, Corella D, Estruch R, Fito M, Gómez-Gracia E, Fiol M, García de

la Corte FJ, Ros E, et al: Dairy product consumption and risk of

type 2 diabetes in an elderly Spanish Mediterranean population at

high cardiovascular risk. Eur J Nutr. 55:349–360. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Leigh JA, Alvarez M and Rodriguez CJ:

Ethnic minorities and coronary heart disease: An update and future

directions. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 18(9)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

World Health Organization (WHO):

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs). WHO, Geneva, 2021. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cardiovascular-diseases-(cvds).

Accessed July 18, 2021.

|

|

6

|

Prentice RL, Aragaki AK, Van Horn L,

Thomson CA, Beresford SA, Robinson J, Snetselaar L, Anderson GL,

Manson JE, Allison MA, et al: Low-fat dietary pattern and

cardiovascular disease: Results from the Women's Health Initiative

randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 106:35–43.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Rees K, Hartley L, Flowers N, Clarke A,

Hooper L, Thorogood M and Stranges S: ‘Mediterranean’ dietary

pattern for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease.

Cochrane Database Syst Rev CD009825, 2013.

|

|

8

|

Denke MA: Diet and lifestyle modification

and its relationship to atherosclerosis. Med Clin North Am.

78:197–223. 1994.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Ruan Y, Huang Y, Zhang Q, Qin S, Du X and

Sun Y: Association between dietary patterns and hypertension among

Han and multi-ethnic population in southwest China. BMC Public

Health. 18(1106)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Wang CJ, Shen YX and Liu Y: Empirically

derived dietary patterns and hypertension likelihood: A

meta-analysis. Kidney Blood Press Res. 41:570–581. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Wang X, Ding N, Tucker KL, Weisskopf MG,

Sparrow D, Hu H and Park SK: A Western diet pattern is associated

with higher concentrations of blood and bone lead among middle-aged

and elderly men. J Nutr. 147:1374–1383. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Dean L and Kane M: Codeine Therapy and

CYP2D6 Genotype. In: Medical Genetics Summaries. Pratt VM, Scott

SA, Pirmohamed M, et al (eds). National Center for

Biotechnology Information (US), Bethesda, MD, 2012.

|

|

13

|

Torkamani A, Pham P, Libiger O, Bansal V,

Zhang G, Scott-Van Zeeland AA, Tewhey R, Topol EJ and Schork NJ:

Clinical implications of human population differences in

genome-wide rates of functional genotypes. Front Genet.

3(211)2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Das I, Khan NS and Sooranna SR: Potent

activation of nitric oxide synthase by garlic: A basis for its

therapeutic applications. Curr Med Res Opin. 13:257–263.

1995.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Zeb I, Ahmadi N, Nasir K, Kadakia J,

Larijani VN, Flores F, Li D and Budoff MJ: Aged garlic extract and

coenzyme Q10 have favorable effect on inflammatory markers and

coronary atherosclerosis progression: A randomized clinical trial.

J Cardiovasc Dis Res. 3:185–190. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Ide N, Matsuura H and Itakura Y:

Scavenging effect of aged garlic extract and its constituents on

active oxygen species. Phytotherapy Res. 10:340–341. 1996.

|

|

17

|

Numagami Y and Ohnishi ST: S-allylcysteine

inhibits free radical production, lipid peroxidation and neuronal

damage in rat brain ischemia. J Nutr. 131 (3s):1100S–1105S.

2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Maldonado PD, Barrera D, Rivero I, Mata R,

Medina-Campos ON, Hernandez-Pando R and Pedraza-Chaverrí J:

Antioxidant S-allylcysteine prevents gentamicin-induced oxidative

stress and renal damage. Free Radic Biol Med. 35:317–324.

2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Ahmadi N, Nabavi V, Hajsadeghi F, Zeb I,

Flores F, Ebrahimi R and Budoff M: Aged garlic extract with

supplement is associated with increase in brown adipose, decrease

in white adipose tissue and predict lack of progression in coronary

atherosclerosis. Int J Cardiol. 168:2310–2314. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Budoff MJ, Ahmadi N, Gul KM, Liu ST,

Flores FR, Tiano J, Miller E and Tsimikas S: Aged garlic extract

supplemented with B vitamins, folic acid and L-arginine retards the

progression of subclinical atherosclerosis: A randomized clinical

trial. Prev Med. 49:101–107. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Budoff M: Aged garlic extract retards

progression of coronary artery calcification. J Nutr. 136 (3

Suppl):741S–744S. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Budoff MJ, Takasu J, Flores FR, Niihara Y,

Lu B, Lau BH, Rosen RT and Amagase H: Inhibiting progression of

coronary calcification using Aged Garlic Extract in patients

receiving statin therapy: A preliminary study. Prev Med.

39:985–991. 2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Steiner M, Khan AH, Holbert D and Lin RI:

A double-blind crossover study in moderately hypercholesterolemic

men that compared the effect of aged garlic extract and placebo

administration on blood lipids. Am J Clin Nutr. 64:866–870.

1996.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Wlosinska M, Nilsson AC, Hlebowicz J,

Malmsjo M, Fakhro M and Lindstedt S: Aged garlic extract preserves

cutaneous microcirculation in patients with increased risk for

cardiovascular diseases: A double-blinded placebo-controlled study.

Int Wound J. 16:1487–1493. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Wlosinska M, Nilsson AC, Hlebowicz J,

Hauggaard A, Kjellin M, Fakhro M and Lindstedt S: The effect of

aged garlic extract on the atherosclerotic process-a randomized

double-blind placebo-controlled trial. BMC Complement Med Ther.

20(132)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Wlosinska M, Nilsson AC, Hlebowicz J,

Fakhro M, Malmsjo M and Lindstedt S: Aged garlic extract reduces

IL-6: A double-blind placebo-controlled trial in females with a low

risk of cardiovascular disease. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med.

2021(6636875)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Rivo E, de la Fuente J, Rivo A,

Garcia-Fontan E, Canizares MA and Gil P: Cross-industry standard

process for data mining is applicable to the lung cancer surgery

domain, improving decision making as well as knowledge and quality

management. Clin Transl Oncol. 14:73–79. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Harper G and Pickett SD: Methods for

mining HTS data. Drug Discov Today. 11:694–699. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Cruz-Bermudez JL, Parejo C, Martinez-Ruiz

F, Sanchez-Gonzalez JC, Ramos Martin-Vegue A, Royuela A,

Rodríguez-González A, Menasalvas-Ruiz E and Provencio M: Applying

data science methods and tools to unveil healthcare use of lung

cancer patients in a teaching hospital in Spain. Clin Transl Oncol.

21:1472–1481. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Larijani VN, Ahmadi N, Zeb I, Khan F,

Flores F and Budoff M: Beneficial effects of aged garlic extract

and coenzyme Q10 on vascular elasticity and endothelial function:

The FAITH randomized clinical trial. Nutrition. 29:71–75.

2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Shaikh K, Kinninger A, Cherukuri L,

Birudaraju D, Nakanishi R, Almeida S, Jayawardena E, Shekar C,

Flores F, Hamal S, et al: Aged garlic extract reduces low

attenuation plaque in coronary arteries of patients with diabetes:

A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Exp Ther Med.

19:1457–1461. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Matsumoto S, Nakanishi R, Li D, Alani A,

Rezaeian P, Prabhu S, Abraham J, Fahmy MA, Dailing C, Flores F, et

al: Aged garlic extract reduces low attenuation plaque in coronary

arteries of patients with metabolic syndrome in a prospective

randomized double-blind study. J Nutr. 146:427S–432S.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Ried K, Frank OR and Stocks NP: Aged

garlic extract reduces blood pressure in hypertensives: A

dose-response trial. Eur J Clin Nutr. 67:64–70. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Ried K, Travica N and Sali A: The effect

of aged garlic extract on blood pressure and other cardiovascular

risk factors in uncontrolled hypertensives: The AGE at Heart trial.

Integr Blood Press Control. 9:9–21. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Bai L, Jing Y, Reis RL, Chen X, Su J and

Liu C: Organoid research: Theory, technology, and therapeutics. OR.

1(025040007)2025.

|

|

36

|

Zhao J, Shen F, Sheng S, Wang J, Wang M,

Wang F, Jiang Y, Jing Y, Xu K and Su J: Cartilage-on-chip for

osteoarthritis drug screening. Organoid Res. 1(8461)2025.

|

|

37

|

Hu K, Li Y, Ke Z, Yang H, Lu C, Li Y, Guo

Y and Wang W: History, progress and future challenges of artificial

blood vessels: A narrative review. Biomater Transl. 3:81–98.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Wang Y, Hou Y, Hao T, Garcia-Contreras M,

Li G, Cretoiu D and Xiao J: Model construction and clinical

therapeutic potential of engineered cardiac organoids for

cardiovascular diseases. Biomater Transl. 5:337–354.

2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Schmidt SK, Hemmestad L, MacDonald CS,

Langberg H and Valentiner LS: Motivation and barriers to

maintaining lifestyle changes in patients with type 2 diabetes

after an intensive lifestyle intervention (The U-TURN Trial): A

longitudinal qualitative study. Int J Environ Res Public Health.

17(7454)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Jones DE, Carson KA, Bleich SN and Cooper

LA: Patient trust in physicians and adoption of lifestyle behaviors

to control high blood pressure. Patient Educ Couns. 89:57–62.

2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|