Introduction

The Greek feta cheese is a traditional semi-soft

white pickled cheese produced from 0-30% goat milk and 70-100%

sheep milk or exclusively from sheep milk (1). Since 2002, it has been recognised as

a protected designation of origin (PDO) product, in accordance with

Commission Regulation (EC) No 1829/2002 (2,3). PDO

cheeses ensure the authenticity of tte product linked to its

geographical indication where it is produced, processed and

developed with recognised expertise characterizing traditional and

craft production. Greek feta PDO is a regional product of

particular areas of Greece (Macedonia, Epirus, Thessaly and

mainland Greece) and is matured in tins or wooden barrels for at

least 60 days (4). Although there

is a variety of >600 different oak species globally (5), only four have been reported to be

suitable for feta PDO cheese production (6). These are Quercus frainetto,

Quercus pubescens, Quercus petraea and Quercus robur and

in Greece, these are found in Western Macedonia, Thrace, Eurytania

and Pindus National Park (7-10).

These species are endemic to specific Greek regions and have

traditionally been used in the construction of wooden barrels for

the maturation of feta PDO cheese. Alongside oak, beech wood is

also considered appropriate.

Wood in contact with raw or pasteurised milk and

cheese is rapidly covered by a microbial biofilm (11,12).

In previous studies, researchers have shown a high biodiversity of

microorganisms that are present in biofilms, not only between the

different types of cheeses studied, but also within the same cheese

variety, between different wooden vats (tina or gerle) used in

different cheese plants (13,14).

The biodiversity confirmed and demonstrated the strong

characterisation of the territorial origin of the products

(15-17).

In cheese, the correct maintenance of wooden vats promotes the

selection of microbial flora, able to play an active role in the

achievement of food safety through the biocompetitive activity of

lactic acid bacteria (LAB) and their inhibitory activity against

pathogenic bacteria, particularly Listeria monocytogenes

(13,18-20).

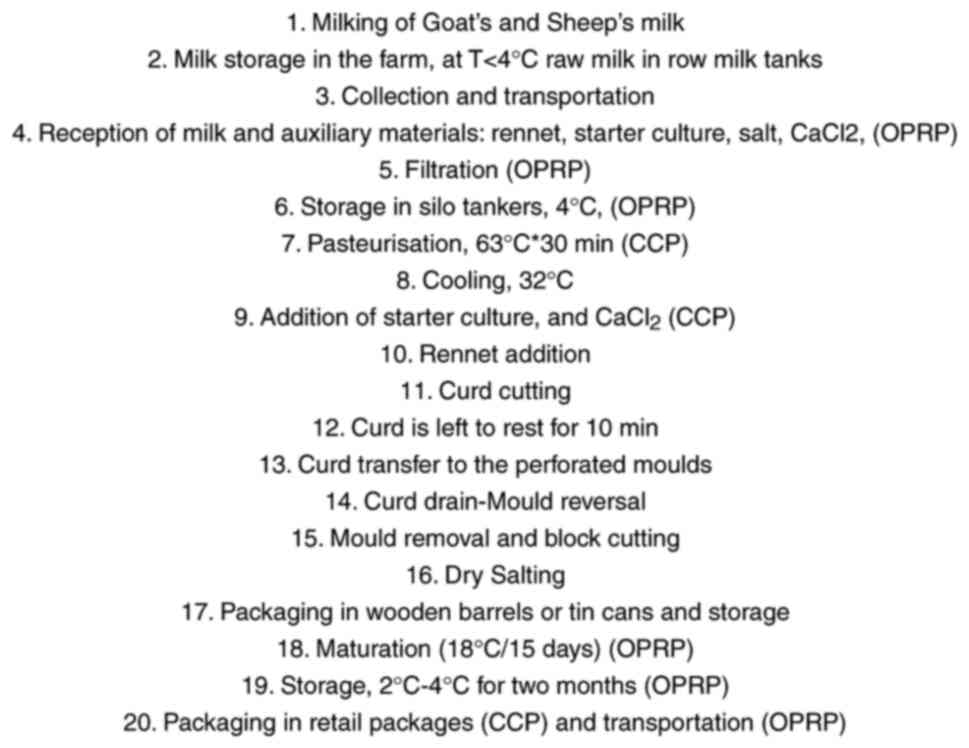

Greek dairies have traditionally produced feta PDO cheese, using

equipment consisting of wooden utensils and wooden barrels of a

capacity of up to 60 kg (6) (as

illustrated in Fig. 1).

According to the guidelines of the Hellenic Food

Safety Authority (EFET) (21), and

Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Point (HACCP) principles for

the traditional small dairy production units in Greece (22), the wooden barrel can be used among

other wooden utensils, to mature traditional feta PDO and white

cheese, such as barrel-aged goat cheese. Their porous structure

supports beneficial microflora, while their use enhances the

texture and flavour through the natural maturation process

(23-25).

On the other hand, the use of traditional and reusable equipment,

particularly in small and medium-sized enterprises producing

barrel-aged feta PDO (2), requires

special attention concerning the implementation of critical control

points (CCPs), that are designed to reduce microbiological (M),

chemical (C) and physical (P) risks in line with HACCP guidelines.

These CCPs and the related Operational Prerequisite Programs

(OPRPs) are outlined throughout the production routine, as

illustrated in the flowchart of the feta PDO cheese production

(Fig. 2) (26). Some studies have demonstrated that

the wooden vats used for raw milk cheese production allow for the

development of a biofilm on the inner surface, which actively

participates in the production process by adding unique sensory

characteristics to the traditional products, such as aroma,

appearance, taste and texture, which is associated with the total

viable count of microorganisms, mesophilic LAB, lactic

cocci/streptococci and yeast/moulds (11,12,27,28).

The present study aimed to monitor the

microbiological parameters during all the stages of the ripening

period of the Fagus sylvatica (beech) barrel-aged feta PDO

cheese (2), to enhance the

established control according to the methodology that complies with

food safety in the final product.

Materials and methods

Wood type selection for the use of the

barrel

A hand-crafted Greek beech barrel constructed by

artisans of the Metsovo area was used to produce and mature feta

PDO cheese. The evaluation of the suitability of the beech wood for

its use in the dairy sector is approved by the State General

Chemistry of Greece and the competent Forest Service, which

verifies the origin of the timber, lawful harvesting and intended

use through official forest marking (29,30).

Beech barrel cleaning

The barrel was inspected for leak tightness and was

then vigorously and thoroughly brushed with pressurised water to

remove any gross solids, such as salts, brine residues, fat,

bacteria and any crumbled feta PDO due to previous usage, which

could impede any further natural sanitation treatments reaching

into the barrel wood. It was then filled with heated whey of 95˚C

[from which the majority of the whey proteins had been removed

through myzithra cheese production (31)] and left at room temperature for 24

h. The barrel was then emptied of the whey, washed with

high-pressure water, and allowed to dry at ambient temperature for

a further 24 h.

Flow diagram of feta PDO cheese

production

Following milking (step 1), raw milk is cooled to

<4˚C and maintained at this temperature during transportation to

the dairy facility (steps 2 and 3). Upon arrival, a milk sample is

collected and analysed for antibiotic residues, and the pH is

measured (step 4) (32,33). The milk is then filtered (step 5)

and stored in large silos (step 6).

The milk is processed within 48 h of milking.

Pasteurization is performed at 63˚C for 30 min (step 7), followed

by cooling to 32˚C (step 8) with intermittent stirring. At this

point, before the stainless steel vat is filled, a starter culture

and calcium chloride are added to its base (step 9). Once filled,

rennet is added under constant stirring, and coagulation occurs

within 45-50 min (step 10).

Following coagulation, the curd is inspected, cut

(step 11), and allowed to rest for 10 min until whey appears on the

cheese surface (step 12). It is then transferred into perforated

moulds (step 13), where it drains and is subsequently reversed

(step 14). The mould is removed, the cheese is cut (step 15) and

dry salt is applied to the surface (step 16). After two hours, the

blocks are flipped and salted again (step16).

Depending on production needs, the salted cheese

blocks are placed into wooden barrels or metal tins on pallets

(step 17), where they remain in the facility area for an additional

24 h. The following day, they are transferred to the ripening

chamber and held at 18˚C for ~15 days, until the pH decreases to

<4.6 (step 18). Finally, the barrels or tins are moved to cold

storage at 2-4˚C for maturation (step 19). The cheese becomes

suitable for consumption 2 months following production (step 19)

(32). Following that period, feta

PDO cheese is being packed into retail packages and is transported

at the point of sale (step 20) (Fig.

2).

Cheese sampling

Feta PDO cheese was produced according to the

requirements described at EL/PDO/0017/0427(34). Moreover, the sale of the cheese as

feta PDO requires certification by the competent controlling

authority ELGO-DEMETER (2,35). In brief, fresh cheese was left to

mature in beech-aged wooden barrels. All samples, namely fresh

milk, wood, curd and brine, were collected and analysed

microbiologically at different time intervals following the

maturation schedule of the 1st day of cheese-making, the 3rd and

45th day of cheese-making, and on the 150th day of the ripening

period.

Biofilm sampling

The biofilms were collected for the enumeration of

total mesophilic count (TMC), and the estimation of the hygiene

indicator bacteria from the inside of the barrel. The biofilm was

scraped off from the beech wood surface using a sterilised razor

blade within a random interior surface of 100 cm2 area,

delimited with a 10x10 cm sterile plastic mask (80 cm2

from the bottom and 20 cm2 from the side surface) at a

depth of ~1.5 mm within the beech barrel. The detection of

Listeria monocytogenes, Staphylococcus aureus and

Salmonella spp. was performed on a larger surface, using a

20x20 cm mask and it was then cleaned with a sterile gauze.

Microbiological analysis

All samples were obtained from the dairy company,

Pagonis Sisters and Co., and were microbiologically analysed. More

specifically, samples derived from the pasteurised sheep and goat

milk, biofilm samples from the empty barrel, samples of feta cheese

during its maturation stages, biofilm samples in the opened barrel

and samples of brine were analysed. The enumeration of the TMC was

conducted in plate count agar (PCA; Biokar diagnostics) incubated

at 30˚C for 72 h (ISO 4833-1:2013) (36), Coliforms on Violet Red Bile Agar

(VRBA; Oxoid; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), incubated at 30˚C

for 24 h (ISO 4832:2006) (37),

Enterobacteria on Violet Red Bile Glucose Agar (VRBG,

Biolife) incubated at 30˚C for 24 h (ISO 21528-2:2017) (38), Escherichia coli in Tryptone

Bile X-Gluc Agar-TBX at 44˚C for 24 h (ISO16649-2/2001) (39,40),

and in chromIDTM Coli Agar (COLI ID-F) NF VALID (AFNOR BIO

12/19-12/06) for further confirmation.

Listeria monocytogenes, Staphylococcus

aureus and Salmonella spp. were detected in compliance

with the microbiological criteria for foodstuffs determined in

Commission Regulation (EC) No 2073/2005 (41,42).

Listeria monocytogenes and Salmonella spp. testing

was performed using a mini VIDAS Compact automated immunoassay

system based on the enzyme linked fluorescent assay (ELFA)

principles by Biomerieux using methods according to the protocols,

VIDAS Listeria monocytogenes II LMO2 BIO-12/11-03/04 and

VIDAS Easy Salmonella SLM BIO-12/16-09/05, respectively.

Both methods were accredited under ISO/IEC 17025:2005. The

enumeration of coagulase-positive staphylococci (CPS,

Staphylococcus aureus) was performed with ISO

6888-2:1999/AMD 1:2003. All methods used for the detection of

foodborne pathogens were accredited according to ISO/IEC 17025 by

the Hellenic Accreditation System E.SY.D. with certification no.

1111(43).

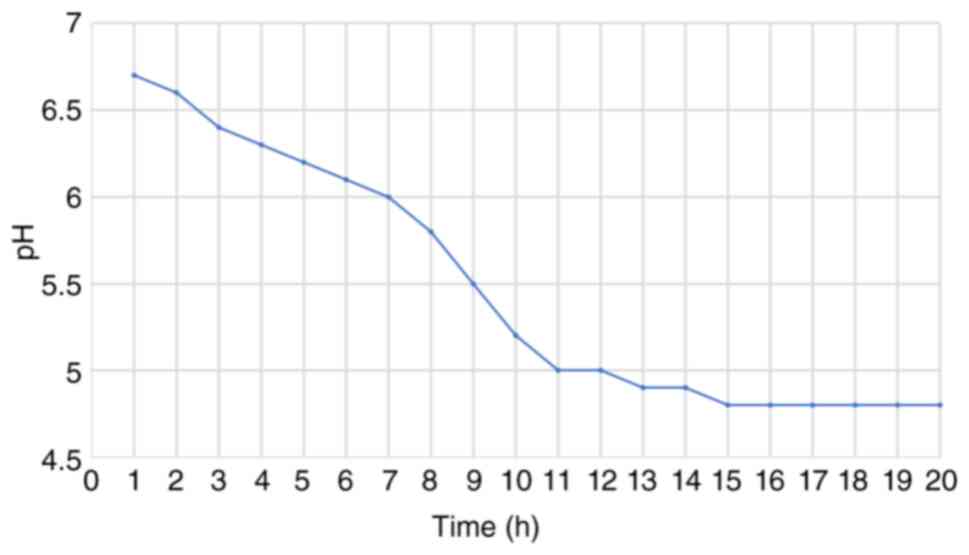

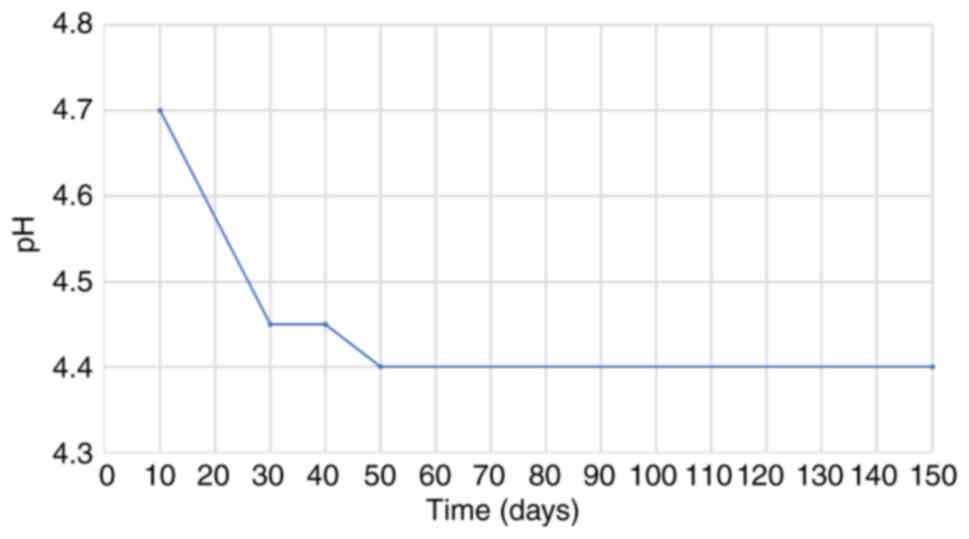

pH value measurement

The pH value of cheese was measured using a RL150 pH

meter (Russel) throughout the maturation process. The pH was

measured by immersing the glass electrode into the cheese sample at

independent time points, without interfering with the

microbiological assessment.

Results

The data obtained from the microbiological analysis

carried out on samples of feta PDO, brine, and biofilm are reported

in Table I, Table II and Table III. The levels of total coliform

bacteria, Enterobacteriaceae and Escherichia coli, in the

pasteurised goat and sheep's milk were zero. Similarly, the 7.6%

(w/w) NaCl microbial loads of brine were null. The TMC ranged from

5.67x105 cfu/cm2 in the biofilm of the empty

barrel to 5.91x105 cfu/cm2 in the biofilm of

the opened barrel, which according to the literature (12,44),

confirms the slight quantitative variation over the ripening period

of feta PDO. Coagulase-positive staphylococci, Listeria

monocytogenes and Salmonella spp. were absent in all

cheese samples. The absence of pathogens was observed in the

biofilm samples taken from the inner surface of the wooden barrel

(45). The follow-up of pH

measurements in feta PDO revealed a gradual decline from 6.7 to 4.5

within the period of monitoring lasted from the first hours of

repining to the fifth month, as shown in Figs. 3 and 4, verifying that acidification proceeded

as expected and that pH levels fell within the target range for the

ripening of feta PDO cheese.

| Table IMicrobiological analysis of

pasteurised milk and feta PDO cheese. |

Table I

Microbiological analysis of

pasteurised milk and feta PDO cheese.

| |

Enterobacteriaceae | E. coli | L.

Monocytogenes | Salmonella

spp. | S. aureus

(coagulase+) |

|---|

| Sample | TMC (log cfu/ml or

cfu/g) | Coliforms (log

cfu/ml or log cfu/g) | log cfu/ml | Limita,b | log cfu/ml or log

cfu/g | Limita | cfu/25 g | Limita,b | cfu/25 g | Limit | cfu/g | Limita,b |

|---|

| D1 milk | 3.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | n=5, c=2, m<1

cfu/ml, M=5 cfu/ml | 0.00 | | | | | | | |

| D1 cheese | | 3.08 | | | 0.00 | | Absent | | Absent | | <10 | |

| D2 cheese | | 0.00 | | | 0.00 | | Absent | | Absent | | <10 | |

| D4 cheese | | 0.00 | | | 0.00 | | Absent | | Absent | | <10 | |

| D15 cheese | | 0.00 | | | 0.00 | | Absent | | Absent | | <10 | |

| D150 cheese | | 0.00 | | | 0.00 | n=5, c=2, m=100

cfu/g M=1.000 cfu/g | <10 | n=5, c=2, m=100

cfu/g, M=1,000 cfu/g | Absent | n=5, c=0, Absent in

25 g | Absent | n=5, c=0, Absent in

25 g |

| Table IIEvaluation of microbial load (log

CFU/ml) of brine following a period of 150 days of feta PDO cheese

maturation. |

Table II

Evaluation of microbial load (log

CFU/ml) of brine following a period of 150 days of feta PDO cheese

maturation.

| Sample-brine | TMC (log

cfu/ml) | Coliforms (log

cfu/ml) | Enterobacteria (log

cfu/ml) | E. coli (log

cfu/ml) | L.

monocytogenes (presence/absence) | Salmonella

spp. (presence/absence) | S. aureus

(coagulase+) (cfu/g) | Regulatory limit

for natural brine (reference) |

|---|

| D150 | 5.77 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | Absent | Absent | <10 | No regulatory

limits exist for brine |

| Table IIIBiofilm microbiological analysis. |

Table III

Biofilm microbiological analysis.

| Biofilm sample/time

point | TMC (log

cfu/cm2) | E. coli (log

cfu/cm2) | L.

monocytogenes (cfu/cm2) | Salmonella

spp. (cfu/cm2) | S. aureus

coagulase+ (cfu/cm2) | Regulatory limit

for biofilm (reference) |

|---|

| Biofilm sample of

D1 before feta PDO was transferred into the barrel | 5.75 | 0.00 | Absent | Absent | <10 | No regulatory

limits exist for biofilm |

| Biofilm sample of

feta PDO on D150 of ripening | 5.77 | 0.00 | Absent | Absent | <10 | Same as above |

Discussion

Greek feta PDO cheese is a national treasure,

representing 90% of the total cheese production of the country

(44). The essential ingredients

for its production include milk, salt, rennet and microorganisms

(46). The matrix of dairy

products facilitates microorganism proliferation, such as

Staphylococcus aureus, Listeria monocytogenes,

Escherichia coli, Brucella abortus, Campylobacter jejuni,

Salmonella, Yersinia enterocolitica, and several others,

compromising the public health status (26,47).

Traceability plays a key role in food chain

management, particularly in the case of rapidly deteriorating

products, such as milk and cheese (48). In this context, traceability has

become a requirement for a better understanding of the life cycle

of products and conscientious delight. Thus, the major concern of

the dairy companies is the respect of the traditional practices

through a certified quality control system according to ISO

22000:2005 and implementing a HACCP daily workflow, illustrated by

Casino et al (49), and in

the workflow of Fig. 2, to

guarantee excellent quality.

Food safety is an increasingly critical public

health concern, and the proposed traceability procedure enhances

the improved process control for managing any future product

recalls and/or product quality. Microbial food contamination in

dairy plants is of utmost significance for the monitoring of food

quality and safety (6,50). For instance, it is known that

Listeria monocytogenes has the potential to survive at low

temperatures (0˚C), low pH values (pH 4.4) and in salt media with

10-20% (w/v) of NaCl (28),

conditions that are close to the physicochemical characteristics of

feta cheese. For the purpose of the present study, further

investigated the food safety of beech barrel-aged Feta PDO, 2.5%

(w/w) NaCl, following the monitoring of pH and through the in-depth

microbiological analysis across the time-points of the production

workflow (Fig. 2).

Previous studies describe that the microbial ecology

found in cheese-making establishments exhibits a great

differentiation in composition, regarding taxonomy classification,

due to the processing procedures (51-53).

The conditions that favour microbiome settlement are several and

are associated with the age, conservation, quality and nature of

the wooden vats. Additionally, the presence of microbial ecosystems

and environmental conditioning (54), such as temperature, humidity, or

pH, markedly affects the selective survival of the microbiome

(55). Humidity, cleaning

protocols, nutrient availability and composition also have a

regulatory impact on the ability of microbes to develop biofilms.

The availability of nutrients in wooden barrels can promote biofilm

development. However, this effect is modulated by key environmental

factors, such as salinity, moisture and pH, which suppress the the

proliferation of pathogenic microorganisms even in nutrient-rich

conditions. This specific microenvironment favours the development

of stable, functional biofilms that enhance the microbial stability

and hygiene of the final product (56). In particular, the limited moisture,

regulated by the high salinity of the brine, combined with the

acidic pH (~4.4), creates a selective ecosystem. Within this

environment, the growth of pathogens, such as Listeria

monocytogenes, Staphylococcus aureus and

Salmonella spp. is inhibited, while microorganisms naturally

adapted to high-salt and low-pH conditions are favoured. These

salt- and acid-tolerant microbiota include lactic acid bacteria

such as Lactobacillus spp., as well as probiotic strains

such as Lactobacillus paracasei and Bifidobacterium

spp., which form resilient, protective biofilms (17). In the present study, the

aggregation of microorganisms referred to as ‘biofilm’ formed in

the wooden barrels used in the production of feta PDO cheese is

characterised by minimal variation in TMC, with a quantitative

change of <5% following 150 days of ripening. Additionally, the

structural and chemical properties of beech wood exert further

selective pressure. Cleaning protocols effectively eliminate

pathogens while preserving these non-pathogenic, functionally

advantageous biofilms. Nutrient limitation during advanced ripening

likely restricts microbial overgrowth, supporting a balanced

beneficial microbiota and ensuring the microbiological safety and

quality of the final product (57-59).

However, in the case of feta PDO production, which has always been

an artisanal process, the improvements through empirical trials

have emerged long before the current scientific knowledge of these

fermentations.

The establishment of the LAB protects against

spoilage bacteria through differential colonisation capability

(60), which creates food

bio-protection conditions, providing antifungal and antimicrobial

activity. This could be explained through mechanisms of competition

for nutrients (61). In the case

of the traditional art that characterises feta PDO aged in a wooden

barrel, surface spoilage is subject to the irregularity of the

surface material, which represents a cardinal issue for compliance

with standard hygiene regulations in food processing plants

(50). In the present study, it

was demonstrated that the traditional practice for the production

of feta PDO cheese using wooden-beech barrels for cheese ageing met

the standards of Good Manufacturing Practice (GΜP) (62), including the appropriate practices

of sanitation to ensure food safety.

Wood, due to its organic properties, particularly

its porosity and hygroscopic nature, is a renewable natural

resource that allows a progressive inlet of oxygen into the barrel

and attributes a sharp flavour to the cheese, but also a slightly

harder texture (23,54,60).

Previous studies have demonstrated that some commonly used wood

species have antimicrobial activities and are suitable for food

contact surfaces (63,64). Wooden barrels remain an

indispensable requirement characterising the traditional practice

of barrel-aged feta PDO. This peculiar maturing process could

significantly influence the future and the perspective of this

iconic Greek product.

Specifically, the use of beech barrels (Fagus

sylvatica) allows for controlled micro-oxygenation, as wood

enables oxygen to reach the inside of feta cheese as it matures.

This oxygen interaction enhances the flavour, contributes to the

development of a sharp, piquant and distinct sensory profile, but

also defines the texture of the cheese. These organoleptic

characteristics are associated to the presence of wood-derived

compounds, such as phenolics, for example, syringyl derivatives,

and mild, insignificant tree lactones (65-67),

as well as tannins, that exert antimicrobial efficacy and

structural resilience in brine (68). This maturation technique highlights

the artisanal and terroir-specific identity of feta, affirming its

value as a PDO product.

Additionally, wooden barrels used in the production

of feta PDO support sustainability goals, as they are biodegradable

and eco-friendly. Their local sourcing supports circular production

and promotes the cultural legacy of cheese, which in turn fosters

the rural economy and helps prevent land abandonment. Furthermore,

the implementation of forest certification protocols could help

prevent and mitigate the decline of tree species commonly used for

timber of beech (Fagus spp.) populations in Mediterranean

regions, while contributing to improved stand structure by

protecting mature trees and promoting natural regeneration

(69).

Consequently, the long-term commitment to using

beech wooden barrels in the production of feta PDO cheese (8,70,71)

ensures not only the preservation of the cultural and nutritional

heritage, but also highlights the use of sustainable forest

management (72,73). This contributes to establishing the

continuity and the viability of agricultural livelihoods in

Greece.

Despite its advantages, wooden barrel sanitisation

poses challenges for product safety, as it carries the risk of

microbial contamination due to the porous nature of the wood

(74). Nevertheless,

forward-looking strategies could further develop Greek feta PDO

cheese, ensuring product safety and enhancing its nutritional

profile, with the potential to qualify as a functional food through

targeted fortification and the integration of adjunct co-culture

strains exhibiting probiotic and technological potential (28,75-76).

These strategies may not only satisfy consumer expectations for

authenticity and safety, but may also boost the market prospects of

traditional cheeses, particularly feta PDO cheese.

Although the specifications for Greek feta PDO

clearly define the origin of the milk, they do not impose specific

requirements on the type of wood used for barrels, since the

regulation does not include this parameter (2). For example, chestnut (Castanea

sativa) has been recommended for fresh cheeses due to its

antioxidant properties and its capacity to enhance product

stability as well as the shelf life in other agro-industrial

by-products (56,77). Likewise, sweet cherry (Prunus

avium L.) is known for its high phenolic content, contributing

to organoleptic, antioxidant, and anti-hyperglycemic benefits

(78,79). At the same time, walnut (Juglans

regia L.) has been incorporated into functional cheese

fortification, as seen in the case of Beyaz cheese (78,79).

Despite these favourable attributes, none of these woods aligns

with the cultural and historical framework that governs the

production of feta PDO.

Although oak is beneficial for cheese ageing, the

porosity of the wood, creates an organic wicking effect that

favours the conditions of drying and ageing of cheese, because it

sustains bacterial growth and the development of biofilms. This is

beneficial, as the prevalence of desirable organisms that are

immobilised within the thick layer of polysaccharides, promotes the

contribution of flavour and positive organoleptic characteristics

to the Feta PDO cheese. Specifically, lactococci and lactobacilli

are critical as they contribute to the cheese acidification and

flavour formation of the feta cheese (23).

To better illustrate how exogenous or endogenous

environmental factors impact microbial populations during feta PDO

cheese ripening, Table IV

summarises the selective pressure acting on several bacterial

species, deduced from both our observations and the literature

evidence. The perspective is that characterisation and mapping of

the microbiome of feta PDO cheese may become a valuable tool for

the monitoring of environmental contamination, to improve the

quality control in the dairy plants, particularly under routine and

experimental conditions such as salinity, moisture, temperature and

pH adjustments. Therefore, understanding the interactions between

feta cheese and selected bacterial flora could be meaningful for

feta PDO cheese manufacturing of a standard quality (50) and variability of organoleptic

features. Moreover, the growth of pathogens and the risk of their

survival is a fundamental issue and needs to be addressed by

validated and frequently monitored good sanitation practices.

| Table IVSummary of endogenous and exogenous

conditions affecting bacterial species during feta PDO cheese

production. |

Table IV

Summary of endogenous and exogenous

conditions affecting bacterial species during feta PDO cheese

production.

| Environmental

factor | Effect on pathogens

(Refs.) | Effect on

beneficial bacteria (LAB) (Refs.) | Remarks |

|---|

| pH

<4.6-(endogenous) | Inhibits pathogen

growth such L. monocytogenes, Salmonella spp., E.

coli (80,81) | Favours

Lactobacillus spp., L. paracasei, Lactococcus

spp. (82,83) | Acid-tolerant LAB

dominate in low pH environments |

| NaCl curd 2.5-2.8%

(w/w) (endogenous) | Osmotic stress

inhibits pathogens, such as S. aureus, Bacillus cereus,

Yersinia spp. (84) | Enhances LAB

survival; stimulates biofilm formation Lactobaccilus

bulgaricus, Lactococcus lactis (85) | LAB possess

salt-tolerance mechanisms |

| Low temperature

(4-10˚C) (exogenous) | Suppresses

mesophilic pathogens (85)’ i.e.,

L. monocytogenes, Salmonella spp., E.

coli | Psychrotolerant

LAB, such as Lactococcus lactis survive and metabolise

slowly (85) | Cold ripening

favours LAB over pathogens |

| Environmental

humidity (exogenous) and brine (endogenous) | Exogenous factor:

Reduces desiccation (86), but

limits aerobic pathogen survival (endogenous factors) (87) | Both exogenous and

endogenous factors support LAB surface colonisation and

stability | Moist environment

promotes biofilm integrity on the wood surface |

| Wooden barrel

(beech or oak) | Surface

irregularities complicate pathogen removal (56) | Promotes biofilm of

LAB (e.g., Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium) (56) | Wood porosity

allows oxygen gradients; enhances flavour development |

| Cleaning (hot

whey) | Effectively removes

planktonic pathogens | Preserves

biofilm-associated beneficial flora | Traditional

cleaning helps balance hygiene with microbial stability |

In conclusion, the present study provides a

comprehensive assessment of the microbiological safety of

handcrafted feta PDO cheese aged in wooden barrels, in accordance

with current food safety regulations in Greece. The results confirm

that the traditional maturation process using beech barrels, when

accompanied by proper cleaning protocols inhibit the presence of

key foodborne pathogens, including Listeria monocytogenes,

Salmonella spp. and Staphylococcus aureus. In

particular, to the best of our knowledge, the present study is the

first to formally document and evaluate under microbiological

criteria the traditional cleaning method of hot whey rinsing during

the ripening of Greek artisanal feta PDO cheesemaking in Fagus

sylvatica barrels, demonstrating that it contributes to the

effective hygienic maintenance of wooden barrels used in the

maturation process.

The observed TMC in biofilm samples revealed minimal

fluctuations (≤5%) over a 150-day ripening period, suggesting a

stable microbial ecosystem. The dominance of beneficial LAB,

fostered by selective environmental pressures such as low pH and

high salinity, supports the formation of functional, protective

biofilms that contribute to both microbial safety and flavour

development. While the complexity and variability of the cheese

microbiota pose challenges for standardisation, they also highlight

the unique sensory identity of feta PDO. In particular, the

presence of beneficial microbial communities within the beech

wood-associated biofilm contributes to both microbial stability and

the organoleptic profile of the cheese during ripening. Future

studies utilizing advanced molecular approaches, such as next

generation sequencing (NGS) and metagenomic analysis, will be

essential for elucidating the role of the microbiome in ripening

dynamics, biofilm formation, and sensory development.

Overall, the present study reinforces the

compatibility of traditional wooden-barrel aging practices with

modern food safety requirements and highlights the potential of

microbial mapping as a future tool for quality control and process

optimisation in artisanal dairy production. Furthermore, the

presence of beneficial microbial populations, particularly

probiotic strains, provides a promising basis for the development

of functional feta cheese with potential health-promoting

properties.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge Mr. Konstantinos

Pagonis, founder of Pagonis Sis & Co., for supporting this

research by sharing his expertise and practical experience in feta

PDO production and Mrs. Eirini Christodoulou, Quality Control

manager of Pagonis Sis & Co., for her insightful suggestions.

The authors would also thank the cooperage company of Barsoukis

Sons and Metsovo Forest Service for specifying the tree

species.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

MP, VZ, GTT and ND conceptualised and designed the

study. MP, AP, IM and AT were involved in the study methodology.

MP, DP and IM provided software (Excel for graph design, GIMP for

image editing and LAB Fit for curve fitting). MP and AP were

involved in the investigative aspects of the study and in the

provision of resources (milk, cheese, brine and biofilm samples).

MP and AP confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. AP, IM, DP

and NPR were involved in data analysis and curation. MP, VZ and AP

were involved in the writing and preparation of the original draft

of the manuscript. MP, DP, AP, IM, NPR and GTT were involved in the

writing, reviewing and editing of the manuscript. AP, ND and GTT

supervised the study. All authors have read and approved the final

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

MP and AP are co-owners of the company Pagonis Sis

& Co. from which the feta was procured. DP, VZ, IM, AT, NPR,

GTT and ND declare that they have no competing interests.

References

|

1

|

Manolopoulou E, Sarantinopoulos P, Zoidou

E, Aktypis A, Moschopoulou E, Kandarakis IG and Anifantakis EM:

Evolution of microbial populations during traditional feta cheese

manufacture and ripening. Int J Food Microbiol. 82:153–161.

2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

European Commission: Commission Regulation

(EC) No 1829/2002 of 14 October 2002 amending the Annex to

Regulation (EC) No 1107/96 with regard to the name ‘Feta’, 2002.

https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2002/1829/oj.

Accessed on December 6, 2024.

|

|

3

|

Bozoudi D, Kotzamanidis C, Hatzikamari M,

Tzanetakis N, Menexes G and Litopoulou-Tzanetaki E: A comparison

for acid production, proteolysis, autolysis and inhibitory

properties of lactic acid bacteria from fresh and mature feta PDO

Greek cheese, made at three different mountainous areas. Int J Food

Microbiol. 200:87–96. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Kritikou AS, Aalizadeh R, Damalas DE,

Barla IV, Baessmann C and Thomaidis NS: MALDI-TOF-MS integrated

workflow for food authenticity investigations: An untargeted

protein-based approach for rapid detection of PDO feta cheese

adulteration. Food Chem. 370(131057)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Chalyan T, Magnus I, Konstantaki M,

Pissadakis S, Diamantakis Z, Thienpont H and Ottevaere H:

Benchmarking spectroscopic techniques combined with machine

learning to study oak barrels for wine ageing. Biosensors (Basel).

12(227)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Katsouri E, Magriplis E, Zampelas A,

Nychas GJ and Drosinos EH: Nutritional characteristics of prepacked

feta PDO cheese products in greece: Assessment of dietary intakes

and nutritional profiles. Foods. 9(253)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Biagi P, Starnini E, Efstratiou N, Nisbet

R, Hughes PD and Woodward JC: Mountain landscape and human

settlement in the Pindus Range: The Samarina Highland Zones of

Western Macedonia, Greece. Land. 12(96)2023.

|

|

8

|

Fyllas NM, Koufaki T, Sazeides CI,

Spyroglou G and Theodorou K: Potential impacts of climate change on

the habitat suitability of the dominant tree species in Greece.

Plants (Basel). 11(1616)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Opgenoorth L, Dauphin B, Benavides R, Heer

K, Alizoti P, Martínez-Sancho E, Alía R, Ambrosio O, Audrey A,

Auñón F, et al: The GenTree platform: Growth traits and tree-level

environmental data in 12 European forest tree species. Gigascience.

10(giab010)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Crous PW, Wingfield MJ, Jurjevic Z,

Balashov S, Osieck ER, Marin-Felix Y, Luangsa-Ard JJ, Mejía LC,

Cappelli A, Parra LA, et al: Fungal Planet description sheets:

1697-1780. Fungal Syst Evol. 14:325–577. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Lortal S, Di Blasi A, Madec MN,

Pediliggieri C, Tuminello L, Tanguy G, Fauquant J, Lecuona Y, Campo

P, Carpino S and Licitra G: Tina wooden vat biofilm: A safe and

highly efficient lactic acid bacteria delivering system in PDO

Ragusano cheese making. Int J Food Microbiol. 132:1–8.

2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Didienne R, Defargues C, Callon C,

Meylheuc T, Hulin S and Montel MC: Characteristics of microbial

biofilm on wooden vats (‘gerles’) in PDO Salers cheese. Int J Food

Microbiol. 156:91–101. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Bonanno A, Tornambe G, Bellina V, De

Pasquale C, Mazza F, Maniaci G and Di Grigoli A: Effect of farming

system and cheesemaking technology on the physicochemical

characteristics, fatty acid profile, and sensory properties of

Caciocavallo Palermitano cheese. J Dairy Sci. 96:710–724.

2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Scatassa ML, Cardamone C, Miraglia V,

Lazzara F, Fiorenza G, Macaluso G, Arcuri L, Settanni L and Mancuso

I: Characterisation of the microflora contaminating the wooden vats

used for traditional sicilian cheese production. Ital J Food Saf.

4(4509)2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Lortal S, Licitra G and Valence F: Wooden

tools: Reservoirs of microbial biodiversity in traditional

cheesemaking. Microbiol Spectr. 2(CM-0008-2012)2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Gaglio R, Cruciata M, Di Gerlando R,

Scatassa ML, Cardamone C, Mancuso I, Sardina MT, Moschetti G,

Portolano B and Settanni L: Microbial activation of wooden vats

used for traditional cheese production and evolution of neoformed

biofilms. Appl Environ Microbiol. 82:585–595. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Cruciata M, Gaglio R, Scatassa ML, Sala G,

Cardamone C, Palmeri M, Moschetti G, La Mantia T and Settanni L:

Formation and characterization of early bacterial biofilms on

different wood typologies applied in dairy production. Appl Environ

Microbiol. 84:e02107–e02117. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Quigley L, O'Sullivan O, Beresford TP,

Ross RP, Fitzgerald GF and Cotter PD: Molecular approaches to

analysing the microbial composition of raw milk and raw milk

cheese. Int J Food Microbiol. 150:81–94. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Licitra G, Caccamo M, Valence F and Lortal

S: Traditional wooden equipment used for cheesemaking and their

effect on quality. In: Global Cheesemaking Technology, pp 157-172,

2017.

|

|

20

|

Papadimitriou K, Anastasiou R, Georgalaki

M, Bounenni R, Paximadaki A, Charmpi C, Alexandraki V, Kazou M and

Tsakalidou E: Comparison of the microbiome of artisanal homemade

and industrial feta cheese through amplicon sequencing and shotgun

metagenomics. Microorganisms. 10(1073)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Varzakas TH, Tsigarida E, Apostolopoulos

C, Kalogridou-Vassiliadou D and Jukes D: The role of the Hellenic

food safety authority in Greece-Implementation strategies. Food

Control. 17:957–965. 2006.

|

|

22

|

Koutou A: The framework of hygiene

inspections in the food sector in greece-implementation of HACCP

principles and penalties in case of non-compliance. Health Sci J.

12(573)2018.

|

|

23

|

Thodis P, Kosma IS, Nesseris K, Badeka AV

and Kontominas MG: Evaluation of a new bulk packaging container for

the ripening of feta cheese. Foods. 12(2176)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Carrascosa C, Millan R, Saavedra P, Jaber

JR, Raposo A and Sanjuan E: Identification of the risk factors

associated with cheese production to implement the hazard analysis

and critical control points (HACCP) system on cheese farms. J Dairy

Sci. 99:2606–2616. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Ruta S, Belvedere G, Licitra G, Nero LA,

Caggia C, Randazzo CL and Caccamo M: Recent insights on the

multifaceted roles of wooden tools in cheese-making: A review of

their impacts on safety and final traits of traditional cheeses.

Int J Food Microbiol. 435(111179)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Geronikou A, Srimahaeak T, Rantsiou K,

Triantafillidis G, Larsen N and Jespersen L: Occurrence of yeasts

in white-brined cheeses: Methodologies for identification, spoilage

potential and good manufacturing practices. Front Microbiol.

11(582778)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Settanni L, Di Grigoli A, Tornambe G,

Bellina V, Francesca N, Moschetti G and Bonanno A: Persistence of

wild Streptococcus thermophilus strains on wooden vat and during

the manufacture of a traditional Caciocavallo type cheese. Int J

Food Microbiol. 155:73–81. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Papadopoulou OS, Argyri AA, Varzakis EE,

Tassou CC and Chorianopoulos NG: Greek functional Feta cheese:

Enhancing quality and safety using a Lactobacillus plantarum strain

with probiotic potential. Food Microbiol. 74:21–33. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Independent Authority for Public Revenue:

Food and Drinks Code, 2024. https://www.aade.gr/en/chemical-laboratories/food-materials-contact-food/chemical-laboratory/food-and-drinks-code.

Accessed on December 15, 2024.

|

|

30

|

Koulelis PP, Proutsos N, Solomou AD,

Avramidou EV, Malliarou E, Athanasiou M, Xanthopoulos G and

Petrakis PV: Effects of climate change on greek forests: A review.

Atmosphere. 14(1155)2023.

|

|

31

|

Andritsos ND and Mataragas M:

Characterization and antibiotic resistance of listeria

monocytogenes strains isolated from greek myzithra soft whey cheese

and related food processing surfaces over two-and-a-half years of

safety monitoring in a cheese processing facility. Foods.

12(1200)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Lappa IK, Natsia A, Alimpoumpa D,

Stylianopoulou E, Prapa I, Tegopoulos K, Pavlatou C, Skavdis G,

Papadaki A and Kopsahelis N: Novel probiotic candidates in

artisanal feta-type kefalonian cheese: Unveiling a

still-undisclosed biodiversity. Probiotics Antimicrob Proteins: Mar

13, 2024 (Epub ahead of print). doi:

10.1007/s12602-024-10239-x.

|

|

33

|

EFSA Panel on Biological Hazards (BIOHAZ).

Koutsoumanis K, Allende A, Alvarez-Ordóñez A, Bolton D, Bover-Cid

S, Chemaly M, Davies R, De Cesare A, Hilbert F, et al: Scientific

opinion on the update of the list of QPS-recommended biological

agents intentionally added to food or feed as notified to EFSA

(2017-2019). EFSA J. 18(e05966)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

European Commission: eAmbrosia: Union

register of geographical indications, 2002. https://ec.europa.eu/agriculture/eambrosia/geographical-indications-register/details/EUGI00000013179.

Accessed on July 12, 2024.

|

|

35

|

Hellenic Agricultural

Organization-Demeter: Control and certification of PDO and PGI

products, 2025. https://www.elgo.gr/index.php?option=com_content&view=category&id=188&Itemid=1259.

Accessed on June 24, 2024.

|

|

36

|

International Organization for

Standardization: ISO 4833-1: Microbiology of the Food

Chain-Horizontal Method for the Enumeration of Microorganisms-Part

1: Colony Count at 30˚C by the Pour Plate Technique, 2013.

https://www.iso.org/standard/53728.html. Accessed on

August 11, 2020.

|

|

37

|

International Organization for

Standardization: ISO 4832:2006: Microbiology of food and animal

feeding stuffs-Horizontal method for the enumeration of

coliforms-Colony-count technique, 2006. https://www.iso.org/standard/38282.html. Accessed on

July 17, 2024.

|

|

38

|

Ogura A, Iwasaki M, Ogihara H and Teramura

H: Evaluation of the novel dry sheet culture method for the

enumeration of enterobacteriaceae. Biocontrol Sci. 23:235–240.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Teramura H, Ogura A, Everis L and Betts G:

MC-Media pad EC for enumeration of escherichia coli and coliforms

in a variety of foods. J AOAC Int. 102:1502–1515. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

International Organization for

Standardization: ISO 16649-2:2001: Microbiology of food and animal

feeding stuffs-Horizontal method for the enumeration of

beta-glucuronidase-positive Escherichia coli: Part 2:

Colony-count technique at 44 degrees C using

5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl beta-D-glucuronide, 2001. https://www.iso.org/standard/29824.html. Accessed on

August 24, 2024.

|

|

41

|

European Commission: Commission Regulation

(EC) No 2073/2005 of 15 November 2005 on microbiological criteria

for foodstuffs, 2005. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2005/2073/oj.

Accessed on August 5, 2024.

|

|

42

|

European Commission: Commission Regulation

(EC) No 1441/2007 of 5 December 2007 amending Regulation (EC) No

2073/2005 on microbiological criteria for foodstuffs, 2007.

https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2007/1441/oj.

Accessed on August 5, 2024.

|

|

43

|

(ESYD) HAS: Certificate Number: 1111-3,

2025. http://esydops.gr/portal/p/esyd/en/showOrgInfo.jsp?id=224143.

Accessed on September 14, 2023.

|

|

44

|

Papadakis P, Konteles S, Batrinou A,

Ouzounis S, Tsironi T, Halvatsiotis P, Tsakali E, Van Impe JFM,

Vougiouklaki D, Strati IF and Houhoula D: Characterization of

bacterial microbiota of P.D.O. Feta cheese by 16S metagenomic

analysis. Microorganisms. 9(2377)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Bintsis T, Litopoulou-Tzanetaki E and

Robinson RK: Microbiology of brines used to mature Feta cheese. Int

J Food Microbiol. 53:106–112. 2000.

|

|

46

|

Anagnostopoulos AK and Tsangaris GT: Feta

cheese proteins: Manifesting the identity of Greece's National

treasure. Data Brief. 19:2037–2040. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Rantsiou K, Urso R, Dolci P, Comi G and

Cocolin L: Microflora of Feta cheese from four Greek manufacturers.

Int J Food Microbiol. 126:36–42. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Mania I, Delgado AM, Barone C and Parisi

S: Traceability in the dairy industry in Europe. In: Traceability

in the Dairy Industry in Europe, pp129-139, 2018.

|

|

49

|

Casino F, Kanakaris V, Dasaklis TK,

Moschuris S, Stachtiaris S, Pagoni M and Rachaniotis NP:

Blockchain-based food supply chain traceability: A case study in

the dairy sector. Int J Prod Res. 59:5758–5770. 2021.

|

|

50

|

Stellato G, De Filippis F, La Storia A and

Ercolini D: Coexistence of lactic acid bacteria and potential

spoilage microbiota in a dairy processing environment. Appl Environ

Microbiol. 81:7893–7904. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Afshari R, Pillidge CJ, Dias DA, Osborn AM

and Gill H: Cheesomics: The future pathway to understanding cheese

flavour and quality. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 60:33–47.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Mahony J, McDonnell B, Casey E and van

Sinderen D: Phage-Host interactions of cheese-making lactic acid

bacteria. Annu Rev Food Sci Technol. 7:267–285. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Montel MC, Buchin S, Mallet A, Delbes-Paus

C, Vuitton DA, Desmasures N and Berthier F: Traditional cheeses:

Rich and diverse microbiota with associated benefits. Int J Food

Microbiol. 177:136–154. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Bokulich NA and Mills DA:

Facility-specific ‘house’ microbiome drives microbial landscapes of

artisan cheesemaking plants. Appl Environ Microbiol. 79:5214–5223.

2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Funari R and Shen AQ: Detection and

characterization of bacterial biofilms and biofilm-based sensors.

ACS Sens. 7:347–357. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Gaglio R, Cruciata M, Scatassa ML, Tolone

M, Mancuso I, Cardamone C, Corona O, Todaro M and Settanni L:

Influence of the early bacterial biofilms developed on vats made

with seven wood types on PDO Vastedda della valle del Belìce cheese

characteristics. Int J Food Microbiol. 291:91–103. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Rather MA, Gupta K, Bardhan P, Borah M,

Sarkar A, Eldiehy KSH, Bhuyan S and Mandal M: Microbial biofilm: A

matter of grave concern for human health and food industry. J Basic

Microbiol. 61:380–395. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

58

|

Licitra G, Ogier JC, Parayre S,

Pediliggieri C, Carnemolla TM, Falentin H, Madec MN, Carpino S and

Lortal S: Variability of bacterial biofilms of the ‘tina’ wood vats

used in the ragusano cheese-making process. Appl Environ Microbiol.

73:6980–6987. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

59

|

Skowron K, Wiktorczyk N, Grudlewska K,

Kwiecińska-Piróg J, Wałecka-Zacharska E, Paluszak Z and

Gospodarek-Komkowska E: Drug-susceptibility, biofilm-forming

ability and biofilm survival on stainless steel of Listeria spp.

Strains isolated from cheese. Int J Food Microbiol. 296:75–82.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

60

|

Munir MT, Pailhories H, Eveillard M, Irle

M, Aviat F, Dubreil L, Federighi M and Belloncle C: Testing the

antimicrobial characteristics of wood materials: A review of

methods. Antibiotics (Basel). 9(225)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

61

|

Siedler S, Balti R and Neves AR:

Bioprotective mechanisms of lactic acid bacteria against fungal

spoilage of food. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 56:138–146. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

62

|

de Oliveira CAF, da Cruz AG, Tavolaro P

and Corassin CH: Chapter 10-food safety: Good manufacturing

practices (GMP), Sanitation standard operating procedures (SSOP),

hazard analysis and critical control point (HACCP). In:

Antimicrobial food packaging. Barros-Velázquez J (ed.) Academic

Press, San Diego, pp 129-139, 2016.

|

|

63

|

Aviat F, Gerhards C, Rodriguez-Jerez JJ,

Michel V, Bayon IL, Ismail R and Federighi M: Microbial safety of

wood in contact with food: A review. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf.

15:491–505. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

64

|

Goncalves JM, Rodrigues KL, Almeida ATS,

Pereira GM and Buchweitz MRD: Assessment of good practices in

hospital food service by comparing evaluation tools. Nutr Hosp.

32:1796–1801. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

65

|

Issa-Issa H, Lipan L, Cano-Lamadrid M,

Nems A, Corell M, Calatayud-García P, Carbonell-Barrachina AA and

López-Lluch D: Effect of aging vessel (Clay-Tinaja versus Oak

Barrel) on the Volatile composition, descriptive sensory profile,

and consumer acceptance of red wine. Beverages. 7(35)2021.

|

|

66

|

Formato M, Scharenberg F, Pacifico S and

Zidorn C: Seasonal variations in phenolic natural products in Fagus

sylvatica (European beech) leaves. Phytochemistry.

203(113385)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

67

|

Wang J, Minami E, Asmadi M and Kawamoto H:

Effect of delignification on thermal degradation reactivities of

hemicellulose and cellulose in wood cell walls. J Wood Sci.

67(19)2021.

|

|

68

|

Das AK, Islam MN, Faruk MO, Ashaduzzaman M

and Dungani R: Review on tannins: Extraction processes,

applications and possibilities. South African J Botany. 135:58–70.

2020.

|

|

69

|

Morales-Molino C, Steffen M, Samartin S,

van Leeuwen JFN, Hürlimann D, Vescovi E and Tinner W: Long-Term

responses of mediterranean mountain forests to climate change, fire

and human activities in the Northern Apennines (Italy). Ecosystems.

24:1361–1377. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

70

|

Stagakis S, Markos N, Vanikiotis T,

Levizou E and Kyparissis A: Multi-year monitoring of deciduous

forests ecophysiology and the role of temperature and precipitation

as controlling factors. Plants (Basel). 11(2257)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

71

|

Varsamis G, Papageorgiou AC, Merou T,

Takos I, Malesios C, Manolis A, Tsiripidis I and Gailing O:

Adaptive diversity of beech seedlings under climate change

scenarios. Front Plant Sci. 9(1918)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

72

|

Winkel G, Lovrić M, Muys B, Katila P,

Lundhede T, Pecurul M, Pettenella D, Pipart N, Plieninger T,

Prokofieva I, et al: Governing Europe's forests for multiple

ecosystem services: Opportunities, challenges, and policy options.

For Policy Econ. 145:2022.

|

|

73

|

Food and Agriculture Organization of the

United Nations: Sustainable Forest Management Toolbox, 2025.

https://www.fao.org/sustainable-forest-management/toolbox.

Accessed on August 15, 2025.

|

|

74

|

Sainz-García A, González-Marcos A,

Múgica-Vidal R, Muro-Fraguas I, Escribano-Viana R,

González-Arenzana L, López-Alfaro I, Alba-Elías F and Sainz-García

E: Application of atmospheric pressure cold plasma to sanitize oak

wine barrels. LWT. 139(110509)2021.

|

|

75

|

Vettorazzi A, de Cerain AL, Sanz-Serrano

J, Gil AG and Azqueta A: European regulatory framework and safety

assessment of food-related bioactive compounds. Nutrients.

12(613)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

76

|

The European Food Information Council:

Bioactive compounds, 2021. https://www.eufic.org/en/whats-in-food/category/bioactive-compounds.

Accessed on May 1, 2023.

|

|

77

|

Ferreira SM, Matos LC and Santos L:

Harnessing the potential of chestnut shell extract to enhance fresh

cheese: A sustainable approach for nutritional enrichment and

shelf-life extension. Journal of Food Measurement and

Characterization. 18:1559–1573. 2024.

|

|

78

|

Nunes AR, Gonçalves AC, Pinto E, Amaro F,

Flores-Félix JD, Almeida A, de Pinho PG, Falcão A, Alves G and

Silva LR: Mineral content and volatile profiling of prunus avium L.

(Sweet Cherry) By-products from fundão region (Portugal). Foods.

11(751)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

79

|

Salık MA and Çakmakçı S: Development and

techno-functional characterization of beyaz cheese fortified with

walnut (Juglans regia L.) leaf powder and lactobacillus acidophilus

LA-5. Probiotics Antimicrob Proteins: Jun 14, 2025 (Epub ahead of

print). doi: 10.1007/s12602-025-10629-9, 2025.

|

|

80

|

Suehr QJ, Chen F, Anderson NM and Keller

SE: Effect of Ph on survival of escherichia coli O157, escherichia

coli O121, and salmonella enterica during desiccation and

short-term storage. J Food Prot. 83:211–220. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

81

|

Chacón-Flores NA, Olivas-Orozco GI,

Acosta-Muñiz CH, Gutiérrez-Méndez N and Sepúlveda-Ahumada DR:

Effect of water activity, pH, and lactic acid bacteria to inhibit

escherichia coli during chihuahua cheese manufacture. Foods.

12(3751)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

82

|

Samelis J and Kakouri A: Microbiological

characterization of greek galotyri cheese PDO products relative to

whether they are marketed fresh or ripened. Fermentation.

8(492)2022.

|

|

83

|

Li Y, Yu H, Tang Z, Wang J, Zeng T and Lu

S: Effect of Coreopsis tinctoria microcapsules on tyramine

production by Enterococcus faecium in smoked horsemeat sausage.

LWT. 170(113974)2022.

|

|

84

|

Akbulut S, Dasdemir E, Ozkan H and

Adiguzel A: Determination of bacteriocin genes and antimicrobial

activity of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum isolated from feta cheese

samples. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 372(fnaf002)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

85

|

Tzora A, Nelli A, Voidarou C, Fthenakis G,

Rozos G, Theodorides G, Bonos E and Skoufos I: Microbiota

‘Fingerprint’ of greek feta cheese through ripening. Appl Sci.

11(5631)2021.

|

|

86

|

Georgalaki M, Anastasiou R, Zoumpopoulou

G, Charmpi C, Lazaropoulos G, Bounenni R, Papadimitriou K and

Tsakalidou E: Feta cheese: A pool of Non-Starter Lactic Acid

Bacteria (NSLAB) with anti-hypertensive potential. Int Dairy J.

162(106144)2025.

|

|

87

|

Doukaki A, Papadopoulou OS, Baraki A,

Siapka M, Ntalakas I, Tzoumkas I, Papadimitriou K, Tassou C,

Skandamis P, Nychas GJ and Chorianopoulos N: Effect of the

bioprotective properties of lactic acid bacteria strains on quality

and safety of feta cheese stored under different conditions.

Microorganisms. 12(1870)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|