Introduction

The cardiac oxygen-sensing mechanism has attracted

extensive attention. A variety of genes relating to hypoxia

adaptation are induced at low-oxygen tensions, including

erythropoietin (EPO), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF),

glycolytic enzymes, glucose transporters, heme proteins, and

hypoxia inducible factor-1 (HIF-1) in various cell types (1–4).

The HIF-1 is the first identified family of transcription factors

that are rapidly elicited by hypoxia by inhibition of their

ubiquitin-dependent degradation (5). Previously, the important role of

HIF-1 in the cellular mechanism of oxygen-sensing was demonstrated

by confirming that the upregulation of 89% of genes induced by

hypoxia is HIF-1-dependent (6).

In their study, Baird et al (7) reported that heat shock proteins

(HSPs) are regulated by HIF-1 during hypoxia.

It has been well documented that cobalt chloride

(CoCl2) is a well-known hypoxia mimetic agent that

mimics the hypoxic response in various ways (3). CoCl2-mimicked hypoxia

enhances the level of HIF-1α protein (8–10).

Thus, CoCl2 has been used to explore the cardiac oxygen-sensing

mechanism in various experiment models. In isolated, perfused rat

hearts in hypoxia/reoxygenation, prior chronic oral

CoCl2 improves cardiac functions by increasing the

levels of VEGF, aldolase-A, and glucose transporter-1 (11). Furthermore, CoCl2

pretreatment before prolonged deep hypothermic circulatory arrest

(DHCA) rescues myocardial apoptosis by mechanisms involving the

phosphorylation of Akt, upregulation of the antiapoptotic protein

Bcl-2 expression and a decreased expression of the proapoptotic

protein Bax (12). These results

showed that preconditioning with CoCl2 protects against

cardiac injury induced by hypoxia or ischemia. The clinical

significance of such a strategy, however, is limited by the

unpredictability of hypoxia or ischemia time. The postconditioning

has been developed and has a similar effect as preconditioning in a

canine model of reversible coronary occlusion (13). Since the hypoxia and/or

ischemia-related diseases or injuries are clinically common,

developing a new therapeutic strategy for treatment of these

diseases or injuries is essential. Since cobalt has been

administered to human patients for the treatment of anemia

(14), and induces several

hypoxia-related protective factors, such as EPO (15,16), HSP90 (17) and heme oxgenase-1 (HO-1) (18,19), we speculates that the co-existence

of low concentrations of CoCl2 with serum and glucose

deprivation (SGD) is likely to attenuate ischemia-like injury in

cardiomyocytes.

To test this hypothesis, we undertook to examine the

protective effect of low concentrations of CoCl2 against

SGD-induced injury of H9c2 cardiomyocytes (H9c2 cells), as well as

the role of HSP90 in this cardioprotection and its mechanisms. The

findings of the present study have demonstrated that the

co-treatment of CoCl2 significantly protects H9c2 cells

against SGD-induced injury. Activation of the oxygen-sensing

mechanism by CoCl2 upregulates the expression of HSP90,

which is an important CoCl2-induced adaptive response to

the SGD condition. Such molecular adaptation to ischemia-like

events may contribute to the functional improvement of

cardiomyocytes, including antioxidation and the preservation of

MMP.

Materials and methods

Materials

CoCl2, glucose,

17-allylamino-17-demethoxygelda-namycin (17-AAG),

dichlorofluorescin diacetate (DCFH-DA) and Rhodamine 123 (Rh123)

were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Corporation (St. Louis, MO, USA).

HSP90 antibody was purchased from Bioworld Technology (Minneapolis,

MN, USA). The cell counter kit-8 (CCK-8) was purchased from Dojindo

Laboratories (Kyushu, Japan). Glucose-free DMEM medium and fetal

bovine serum (FBS) were supplied by Gibco-BRL (Calsbad, CA,

USA).

Cell culture and treatments

H9c2 cells were obtained from Sun Yat-sen University

Experimental Animal Centre (Guangzhou, China). The H9c2 cell line,

a subclone of the original clonal cell line, was derived from

embryonic rat heart tissue. The cells were cultured in DMEM medium

supplemented with normal glucose (5.5 mM) and 15% FBS at 37°C under

an atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 95% air.

H9c2 cells were incubated in glucose- and FBS-free

DMEM medium to set up a model of SGD and mimic ischemia-induced

cardiac injury. CoCl2 was added into the above DMEM

medium to examine its cytoprotective effects. The selective HSP90

inhibitor, 17-AAG, was administered for 60 min prior to exposure of

the H9c2 cells to CoCl2 and SGD.

Cell viability assay

Cell viability was detected by the CCK-8 kit. H9c2

cells were cultured in 96-well plates at a density of 5,000

cells/well. When the cells were ∼70% fused, the indicated

treatments were performed. After the treatments, 10 μl CCK-8

solution was added into each well and the plates were incubated for

3 h. The absorbance at 450 nm was measured with a microplate reader

(Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). A mean optical density

(OD) of 4 wells in each group was used to calculate percentage of

cell viability using the formula: percentage of cell viability = OD

treatment group/OD control group x100%. Experiments were performed

in triplicate.

Western blotting

At the end of the treatments, the H9c2 cells were

harvested and lysed with ice-cold cell lysis solution and the

homogenate was centrifuged at 10,000 x g for 12 min at 4°C. Total

protein in the supernatant was quantified using a BCA protein assay

kit. Total protein (20 μg) from each sample was separated by 12%

SDS-PAGE. The protein in the gel was transferred into

polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane. The membrane was blocked

with 5% fat-free milk in TBS-T for 2 h at room temperature, and

then incubated with the primary antibodies specific to HSP90

(1:2,000), or β-actin (1:8,000) with gentle agitation at 4°C

overnight, followed by horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary

antibodies for 60 min at room temperature. After three washes with

TBS-T, the membranes were developed using an enhanced chemi

luminescence and exposed to X-ray film. To quantify the protein

expression, the X-ray film was scanned and analyzed using ImageJ

1.46i software (National Institutes of Health, USA).

Measurement of intracellular reactive

oxygen species (ROS) level

Intracellular ROS was determined by the oxidative

conversion of cell-permeable DCFH-DA to fluorescent DCF. H9c2 cells

were cultured on a slide in DMEM-F12 medium. After the indicated

treatments, the slides were washed twice with phosphate-buffered

saline (PBS). DCFH-DA solution in serum-free medium was added at a

concentration of 10 μM and co-incubated with H9c2 cells at 37°C for

60 min. The slides were washed three times, and DCF fluorescence

was measured over the entire field of vision using a fluorescent

microscope connected to an imaging system (BX50-FLA; Olympus). Mean

fluorescence intensity (MFI) from three random fields was analyzed

using ImageJ 1.46i software and the MFI of DCF represented the

amount of ROS.

Measurement of mitochondrial membrane

potential (MMP)

MMP was monitored with a fluorescent dye Rh123, a

cell-permeable cationic dye that preferentially enters into

mitochondria based on the highly negative MMP. Depolarization of

MMP results in the loss of Rh123 from mitochondria and a decrease

in intracellular green fluorescence. Rh123 (100 mg/l) was added

into cell cultures for 30 min at 37°C and fluorescence was measured

over the entire field of vision with a fluorescent microscope

connected to an imaging system (BX50-FLA; Olympus). MFI of Rh123

from three random fields was analyzed using ImageJ 1.46i software

and MFI was regarded as an index of the level of MMP.

Statistical analysis

Data were shown as the mean ± SE. The assessment of

differences between groups was analyzed by Tukey’s test of one-way

ANOVA with OriginPro 8.0 (OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA,

USA). P<0.05 was considered to indicate statistical

significance.

Results

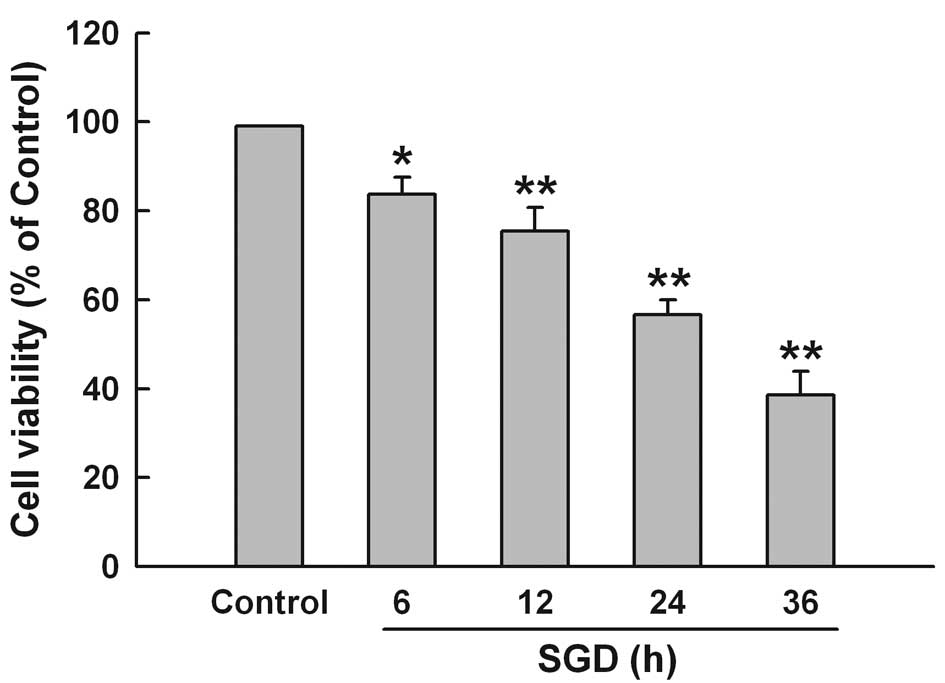

SGD time-dependently enhances

cytotoxicity in H9c2 cells

To test the effect of SGD on cytotoxicity in H9c2

cells, the CCK-8 assay was performed. Fig. 1 shows that SGD obviously induced

cytotoxicity, leading to a time-dependent decrease in cell

viability. Cell survival was decreased to 56.7±3.3% by 24 h of

incubation in serum- and glucose-free medium. Therefore, 24 h of

SGD was used as an effective injury time in the subsequent

experiments.

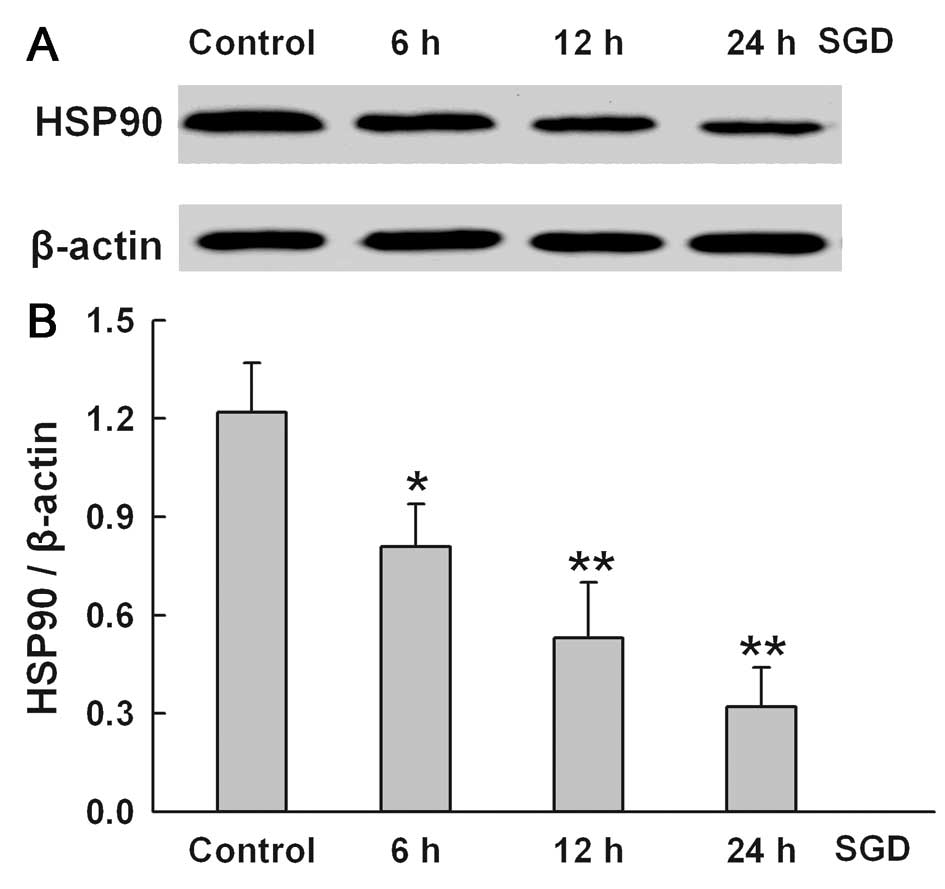

SGD downregulates the expression of HSP90

in H9c2 cells

To determine the effect of SGD on HSP90 expression,

the changes in HSP90 expression were tested in serum- and

glucose-deprived H9c2 cells for the indicated times (6, 12 and 24

h), respectively. SGD attenuated HSP90 expression in a

time-dependent manner, suggesting that the downregulation of HSP90

expression may be one of the mechanisms involved in SGD-induced

injury in the H9c2 cells (Fig.

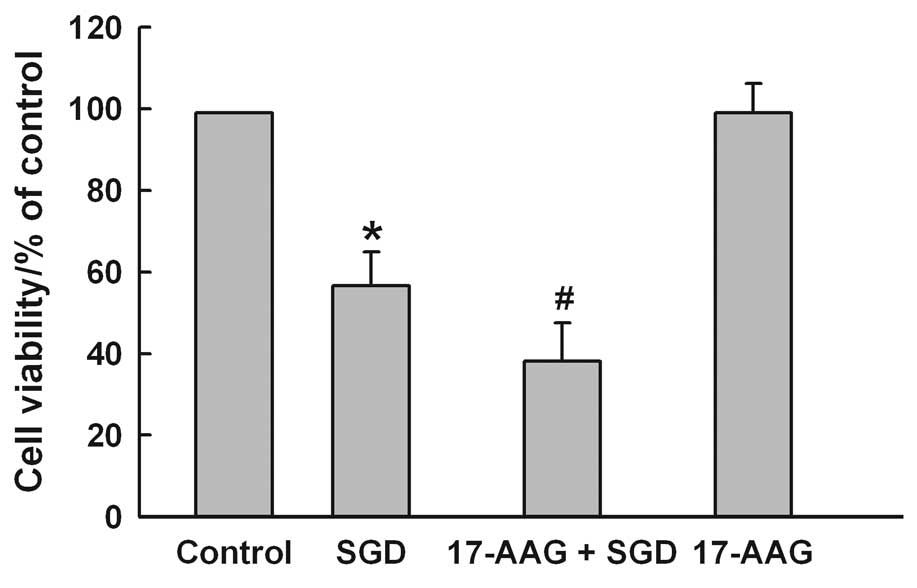

2). The results of subsequent experiments showed that

pretreatment of the cells with 2 μM 17-AAG, a selective inhibitor

of HSP90, for 60 min before SGD for 24 h markedly aggravated

SGD-induced cytotoxicity, evidenced by a further decrease in cell

viability (Fig. 3). However,

17-AAG alone did not alter cell viability in H9c2 cells. These

results showed that HSP90 may be one of the molecular defensive

mechanisms against SGD-induced injury in H9c2 cells.

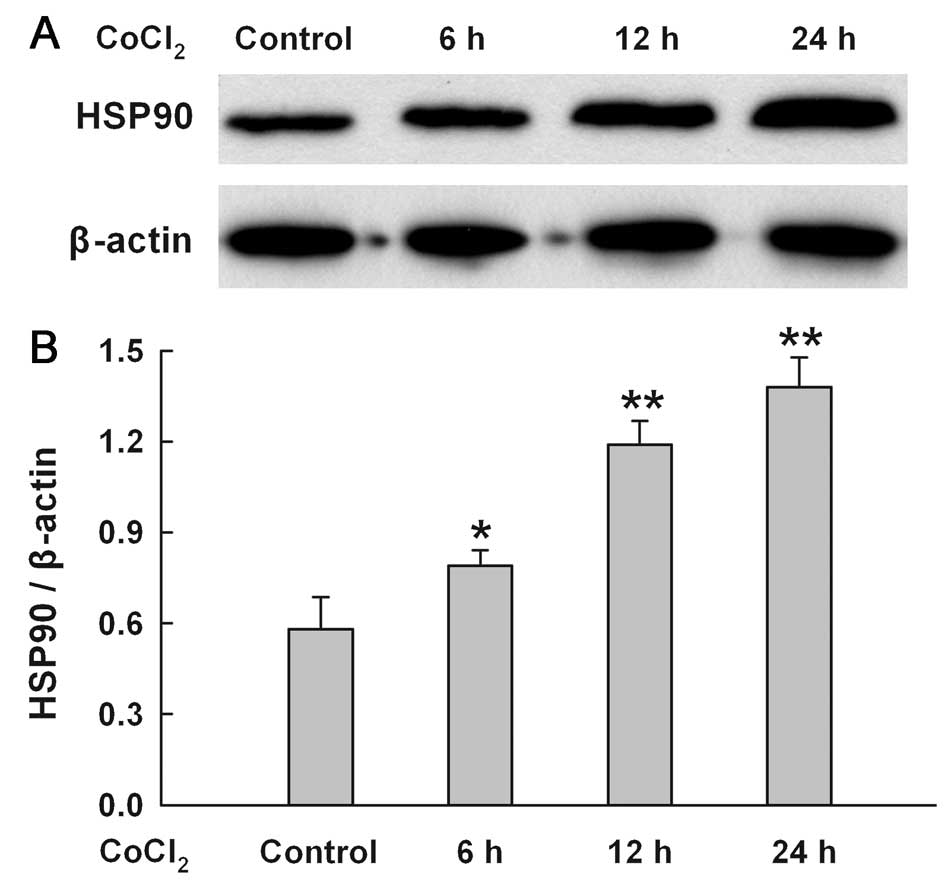

CoCl2 time-dependently

upregulates the expression of HSP90 in H9c2 cells

As shown in Fig.

4, when H9c2 cells were treated with 100 μM CoCl2

for 6–24 h, a time-dependent increase in HSP90 expression was

found.

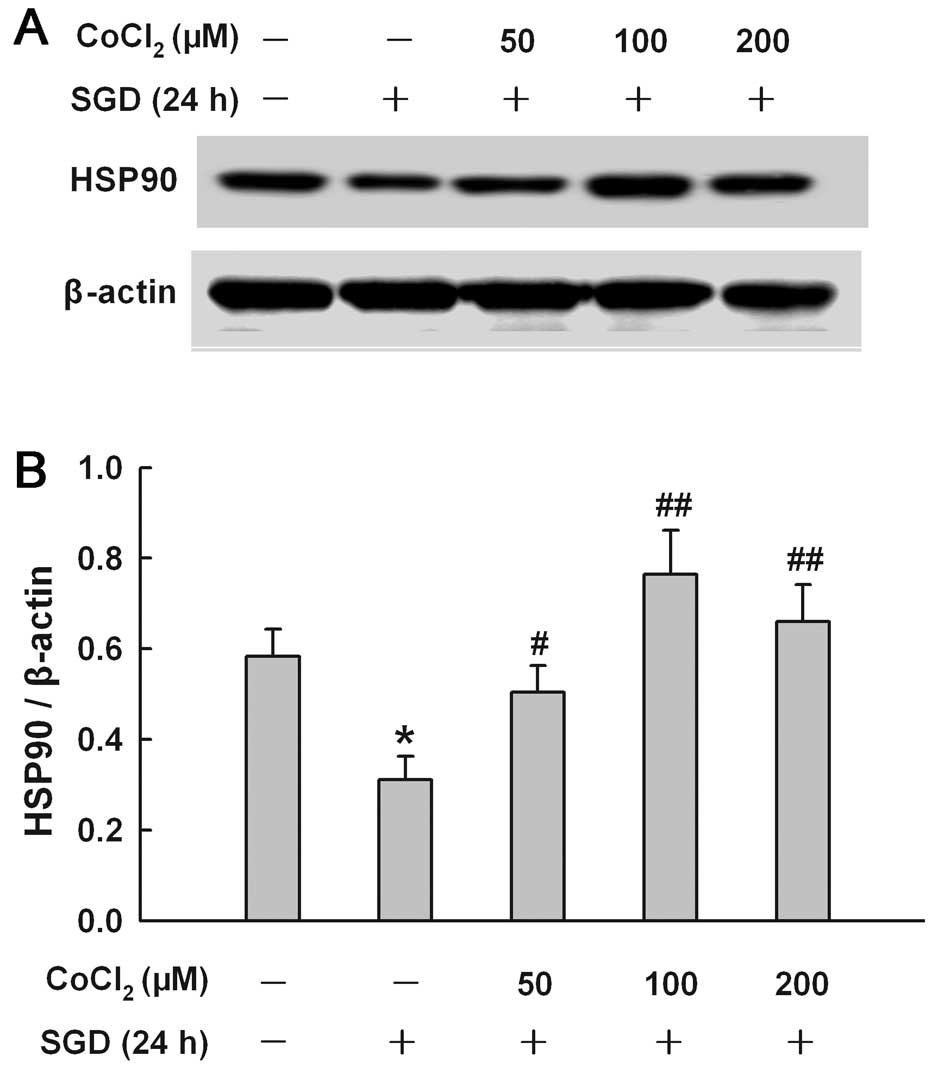

CoCl2 reduces the inhibitory

effect of SGD on the expression of HSP90 in H9c2 cells

To explore the effect of chemical hypoxia on the

SGD-induced inhibition of HSP90 expression, H9c2 cells were treated

with CoCl2 at concentrations ranging from 50 to 200 μM

for 24 h in the presence of SGD, respectively. Fig. 5 shows that co-treatment with

CoCl2 at 50, 100 and 200 μM inhibited the downregulation

of the SGD-induced HSP90 expression. A maximal inhibitory effect of

CoCl2 was observed at 100 μM.

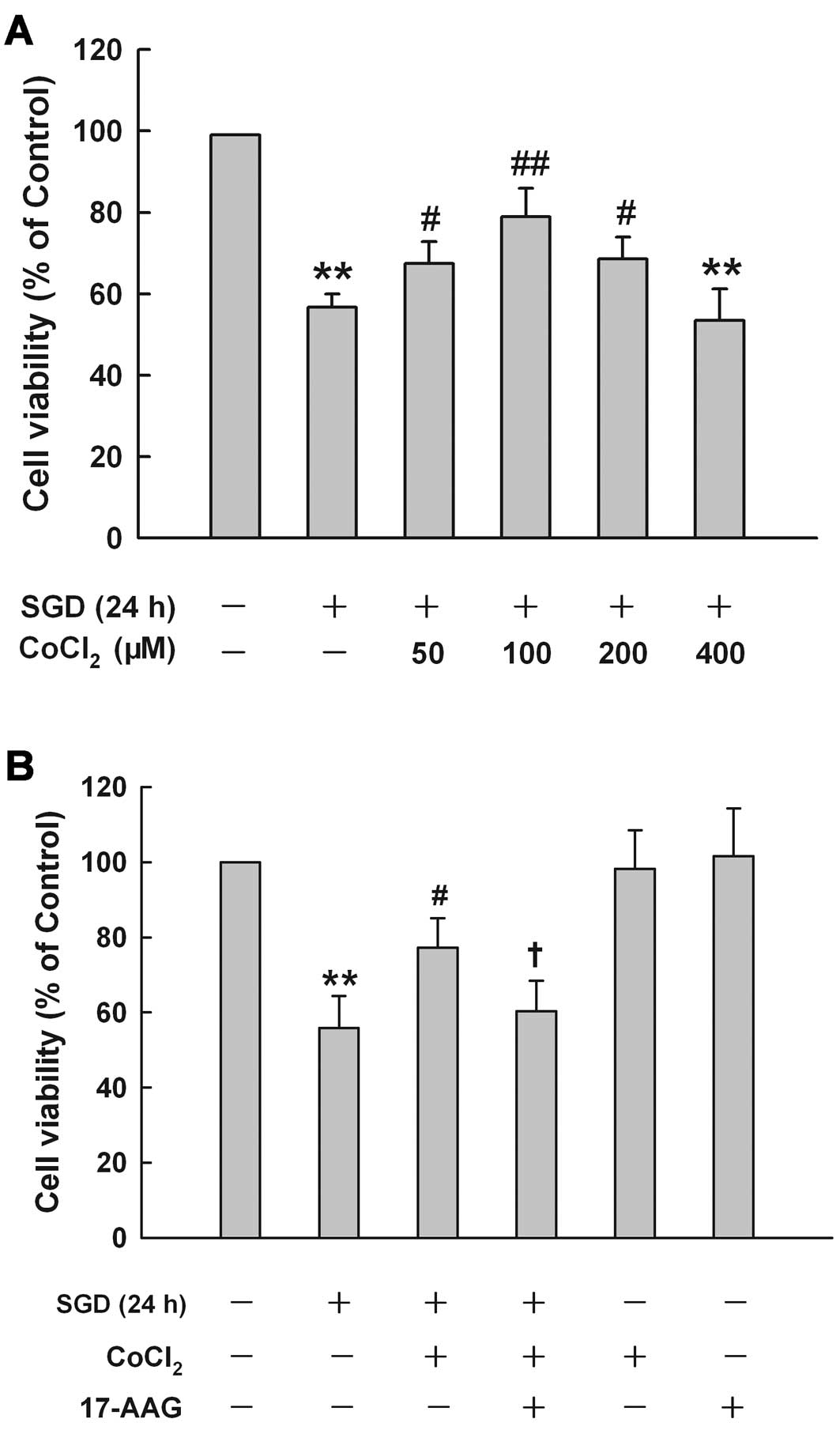

HSP90 contributes to the cytoprotection

at low concentrations of CoCl2 against SGD-induced

cytotoxicity in H9c2 cells

CoCl2 at different concentrations had

different effects on SGD-induced cytotoxicity in H9c2 cells

(Fig. 6A). Treatment of cells

with low concentrations (50, 100 and 200 μM) obviously protected

against SGD-induced cytotoxicity, leading to an increase in cell

viability. These concentrations demonsrated a maximum

cytoprotective effect of CoCl2 at 100 μM, which alone

did not affect cell viability (data not shown). Therefore, 100 μM

of CoCl2 was used as an effective protection

concentration in the subsequent experiments. These results suggest

that sublethal chemical hypoxia treatment is protective against

ischemia-like injury.

To investigate the role of HSP90 in the

cytoprotective effect of CoCl2 at low concentrations

against SGD-induced injury, H9c2 cells were pretreated with 2 μM

17-AAG, a selective inhibitor of HSP90, for 60 min prior to the

co-treatment of 100 μM CoCl2 with SGD for 24 h. Fig. 6B shows that cell treatment with

100 μM CoCl2 considerably reduced SGD-induced

cytotoxicity, evidenced by an increase in cell viability. However,

this cytoprotection of CoCl2 treatment was reduced by

17-AAG pretreatment, suggesting that HSP90 is involved in the

protective effect of sublethal chemical hypoxia against cardiac

toxicity induced by SGD in H9c2 cells. However, 2 μM 17-AAG alone

did not alter cell viability.

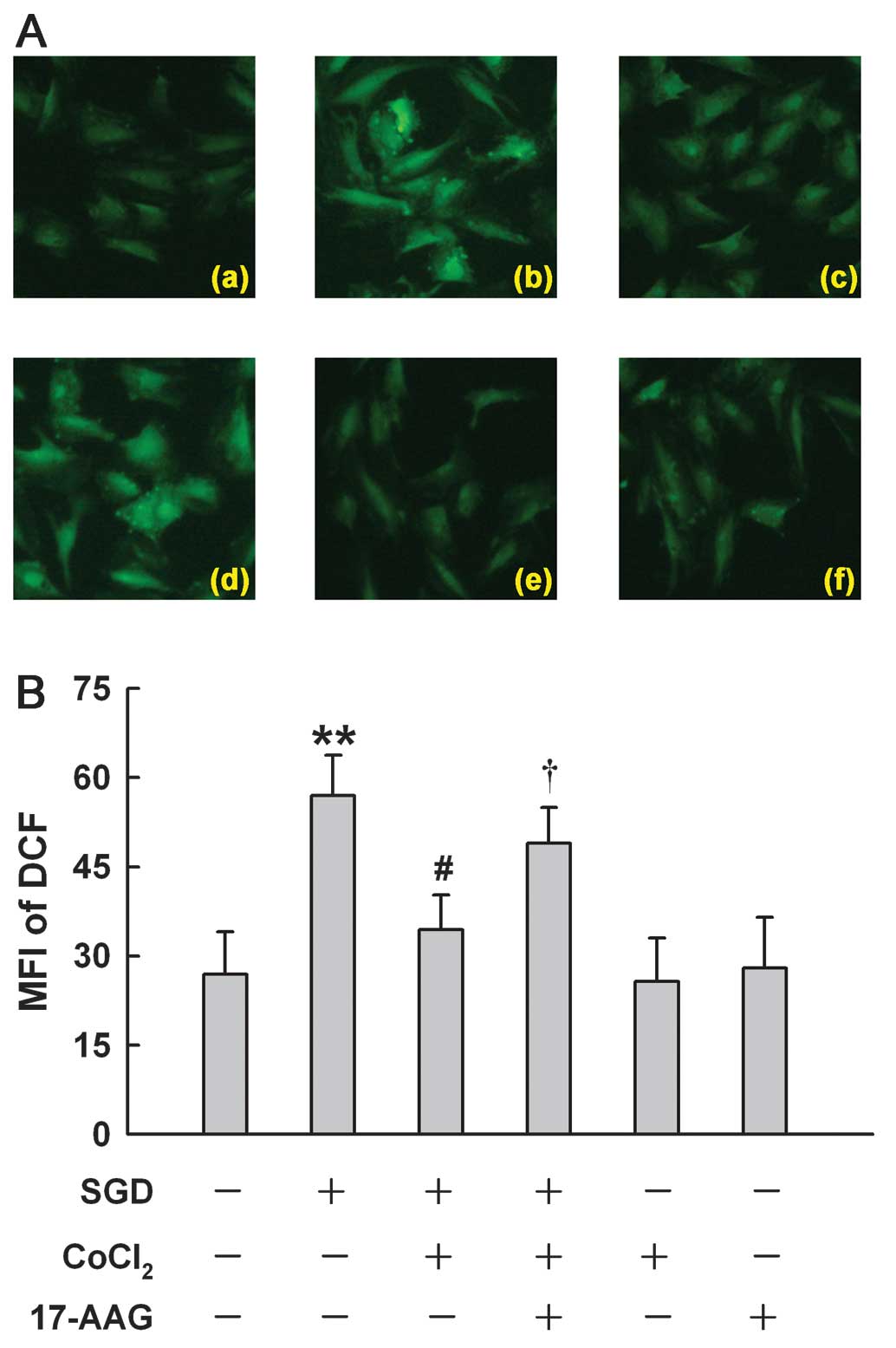

HSP90 participates in the antioxidant

effect induced by a low concentration of CoCl2 in H9c2

cells

A more recent study showed that a high concentration

(600 μM) of CoCl2 induces ROS generation in H9c2 cells

(17). Of note, we found that

CoCl2 at 100 μM reduced SGD-induced ROS generation,

manifesting a decrease in DCF-derive fluorescence (an index of ROS

level) (Fig. 7Ac). However, the

antioxidant effect of 100 M CoCl2 was markedly

suppressed by the inhibition of HSP90 with 17-AAG at 2 μM (Fig. 7Ad). Alone, 100 μM CoCl2

or 2 μM 17-AAG did not alter the basal level of ROS. These results

indicated that the antioxidant effect of low concentrations of

CoCl2 may be associated with an upregulated HSP90

expression.

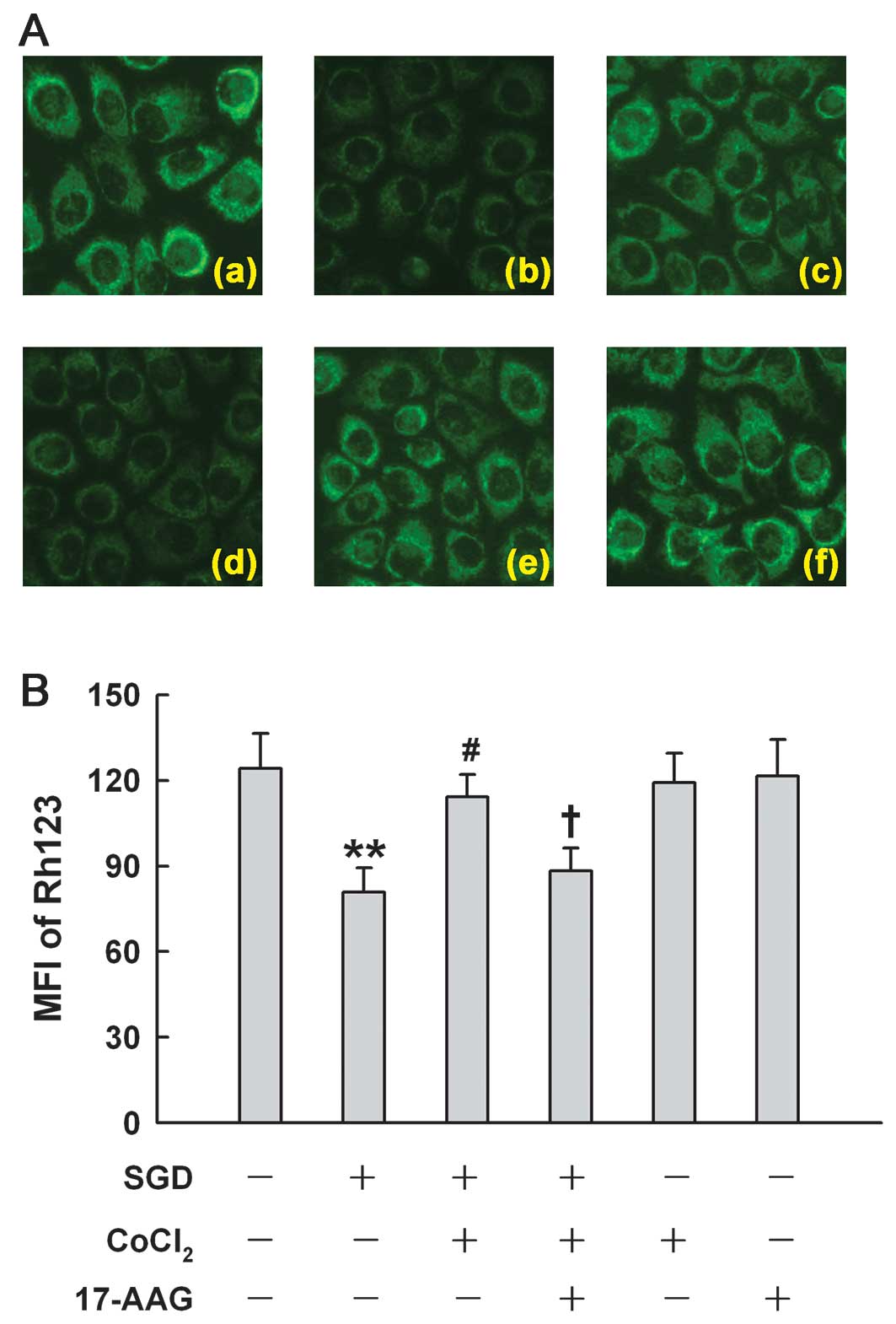

HSP90 is associated with the

mitochondrial protection induced by low concentrations of

CoCl2 in H9c2 cells

Fig. 8 shows that

after H9c2 cells were subjected to SGD for 24 h, mitochondria were

markedly damaged, leading to a decrease in the uptake of Rh123,

demonstrating dissipation of MMP (Fig. 8Ab). The loss of MMP was reduced by

treatment with 100 μM CoCl2 for 24 h (Fig. 8Ac). The inhibition of HSP90 by

17-AAG (2 μM) pretreatment significantly depressed the

mitochondrial protection induced by CoCl2, resulting in

the severe loss of MMP, suggesting that low concentrations of

CoCl2 provide mitochondrial protection by enhancing

HSP90 expression.

Discussion

The important findings of this study are that

co-treatment of low concentrations of CoCl2 with SGD

provides cardioprotection against ischemia-like injury in H9c2

cells and that HSP90 contributes to the cardioprotective effect of

sublethal chemical hypoxia from SGD-induced injury through its

antioxidation and mitochondrial protection. The present study

provides novel evidence to support the hypothesis that sublethal

endogenous hypoxia may be one of the defensive mechanisms by which

cardiomyocytes become more resistant to ischemia-induced injury and

that cobalt, a traditional medicine, may have therapeutic efficacy

for the treatment of ischemia-related cardiac diseases.

Previous studies have shown that pretreatment with

CoCl2, a well-known hypoxia mimetic agent, offers

cardioprotective effects, including attenuation of myocardial

apoptosis (12) and improvement

of cardiac contractile functions (11). Consistent with these studies

(11,12), in the present study, we found that

co-treatment of 100 μM CoCl2, which does not damage H9c2

cells, is able to protect against SGD-induced injury, leading to an

increase in cell viability, a decrease in ROS generation and a

preservation of MMP. Due to the unpredictability of hypoxia or

ischemia timing, the clinical significance of hypoxia

preconditioning is limited. Since co-treatment with

CoCl2 has a similar cardioprotection as CoCl2

preconditioning, the administration of cobalt used in this study

has potential clinical significance for the treatment of

ischemia-related heart diseases. Furthermore, our results provide

new data to demonstrate the inhibitory effect of cobalt on

ischemia-like cardiac injury.

Based on our findings and those of previous studies

(11,12,15–19), several possible mechanisms are

responsible for the cardioprotective effect of low concentrations

of CoCl2: i) its antioxidant effect, by which

CoCl2 is able to reduce SGD-induced ROS generation in

H9c2 cells. Consistent with our findings, a previous study has

shown that manganese-containing superoxide dismutase (SOD) and

mitochondrial-targeted catalase significantly protects against

cytotoxicity and the glucose deprivation-induced oxidative stress

(20); ii) its mitochondrial

protective effect, by which CoCl2 inhibits the

SGD-induced dissipation of MMP. Similarly, cobalt has been shown to

have direct action in preserving ATP in adult rat myocardium

(21); iii) its enhancement

effect on HIF-1 expression, by which CoCl2 is capable of

protecting isolated mouse hearts against ischemia/reperfusion

(I/R)-induced injury (22); iv)

its upregulation effect on EPO, which is one of the target products

of HIF-1. Cai et al (23)

reported that hearts exposed to intermittent hypoxia or EPO are

protected from I/R-induced injury. Previous studies have

demonstrated the effectiveness of EPO in limiting apoptosis in rat

cardiac myocytes (24,25); v) its enhancing the levels of

VEGF, by which low concentrations of CoCl2 improves

cardiac contractile functions (11). VEGF is a potent angiogenic factor

and its upregulation may facilitate tissue perfusion and

oxygenation in hypoxia, an important adaptation to hypoxia; vi) its

inductive effect of glucose transporters (GLUT). In the in

vivo heart and cultured cardiac cells, both hypoxia and

Co2+ rapidly induce GLUT-1 expression in the mRNA level

(26,27). The increased GLUT-1 is involved in

improved cardiac contractile function in hypoxia-reoxygenation in

rats treated with low concentrations of CoCl2 (11).

Besides the above six possible mechanisms underlying

the cardioprotection of low concentrations of CoCl2,

another important mechanism involves the activation of the

oxygen-sensing mechanism by CoCl2, which may upregulate

the expression of HSPs. HSPs are a family of protective proteins,

which provide an endogenous cell defense mechanism against hostile

environmental stress, including hypoxia and ischemia. Accumulating

evidence has shown that the upregulation of HSP expression is

capable of protecting cardiomyocytes from I/R-induced damage

(28) or chemical

hypoxia-triggered injury (17).

Notably, CoCl2 is also able to upregulate the expression

of HSP90 in H9c2 cells (17).

Based on these previous studies (17,29), we hypothesizes that HSP90

possibley contributes to the cardioprotective effect of

co-treatment with low concentrations of CoCl2 from

SGD-induced cardiomyocyte injury. In the present study, we

initially observed that SGD downregulated the expression of HSP90

and that 17-AAG, a selective inhibitor of HSP90, significantly

aggravated SGD-induced cytotoxicity in H9c2 cells, suggesting that

HSP90 is an endogenous protective protein against SGD-induced

injury. Secondly, we found that co-treatment with 100 μM

CoCl2, not only enhanced the expression of HSP90, but

also obviously blocked the inhibitory effect of SGD on HSP90

expression. Thirdly, examination into the roles of HSP90 in the

cardioprotection of low concentrations of CoCl2 against

SGD-induced injuries, including cytotoxicity, overproduction of ROS

and dysfunction of mitochondria was conducted. The findings of the

present study have shown that the inhibition of HSP90 by 17-AAG

markedly blocked the reduction of cytotoxicity induced by

CoCl2 at 100 μM, indicating the involvement of HSP90 in

the cardioprotective effect of CoCl2 against

SGD-triggered injury. Our results are comparable with those of a

recent study whereby the inhibition of HSP90 by geldanamycin, an

inhibitor of HSP90, or siRNA completely eliminates the protective

effect of hypoxic pretreatment against prolonged

hypoxia/reoxygenation-elicited damage in H9c2 cells (30). Yang et al (17) also reported that increased HSP90

expression participates in the cardioprotection induced by hydrogen

sulfide (H2S).

ROS is regarded as a toxic byproduct of aerobic

metabolism following reoxygenation after periods of ischemia or

hypoxia (31). Ahmad et al

(20) indicated that

mitochondrial ROS mediate glucose deprivation-induced cytotoxicity.

In this study, it was shown that co-treatment with low

concentrations of CoCl2 attenuated cytotoxicity, along

with a decrease in ROS production, suggesting that co-treatment

with CoCl2 is likely to induce antioxidants to reduce

ROS generation. Findings of a more recent study have demonstrated

the involvement of HSP90 in the antioxidant effect of

H2S (17). In

agreement with this evidence, our data showed that 17-AAG

significantly depressed CoCl2-induced inhibitory effect

on the overproduction of ROS elicited by SGD in H9c2 cells,

demonstrating that HSP90 is involved in the antioxidant effect of

CoCl2.

Mitochondria play a critical role in determining the

cell fate (32) by regulating the

mitochondrial permeability transition pore (PTP) and the release of

a number of apoptotic factors. Cell death inhibition is accompanied

by MMP preservation (17,33–35). Since antioxidants are able to

inhibit the loss of MMP, the role of HSP90 in the

CoCl2-induced cardioprotective effect may be associated

with the preservation of mitochondrial function. In this study,

co-treatment with CoCl2 considerably inhibited

SGD-induced loss of MMP, and this mitochondrial protective function

was blocked by the inhibition of HSP90 by 17-AAG. Our findings are

supported by those of Yang et al (17) and are consistent with a recent

finding that HSP90 is required for mitochondrial protein import for

hydrophobic membrane proteins, especially under stress conditions

(36).

Taken together, in the present study, we have

demonstrated that chemical hypoxia-upregulated HSP90 expression

contributes to the CoCl2-induced cardioprotective effect

from SGD-triggered injury by depressing cytotoxicity and oxidative

stress as well as preserving MMP. However, more experiments are

required to elucidate the activation of the cardiac oxygen-sensing

mechanism by CoCl2, in particular, the interaction

between HIF-1 and HSP90.

Acknowledgements

The present study was supported by the

Science and Technology Planning Project of Guangdong in China (nos.

2011B031800002 and 2011B080701051) and the Guangdong Natural

Science Foundation (no. S2011010002620).

References

|

1.

|

J FandreyHypoxia-inducible gene

expressionRespir Physiol101110199510.1016/0034-5687(95)00013-4

|

|

2.

|

JM GleadlePJ RatcliffeHypoxia and the

regulation of gene expressionMol Med

Today4122129199810.1016/S1357-4310(97)01198-29575495

|

|

3.

|

MA GoldbergSP DunningHF BunnRegulation of

the erythropoietin gene: evidence that the oxygen sensor is a heme

proteinScience24214121415198810.1126/science.28492062849206

|

|

4.

|

GL SemenzaGL WangA nuclear factor induced

by hypoxia via de novo protein synthesis binds to the human

erythropoietin gene enhancer at a site required for transcriptional

activationMol Cell Biol125447545419921448077

|

|

5.

|

GL SemenzaO2-regulated gene

expression: transcriptional control of cardiorespiratory physiology

by HIF-1J Appl Physiol96117311772004

|

|

6.

|

AE GreijerP van der GroepD

KemmingUp-regulation of gene expression by hypoxia is mediated

predominantly by hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF-1)J

Pathol206291304200510.1002/path.177815906272

|

|

7.

|

NA BairdDW TurnbullEA JohnsonInduction of

the heat shock pathway during hypoxia requires regulation of heat

shock factor by hypoxia-inducible factor-1J Biol

Chem2813867538681200610.1074/jbc.M60801320017040902

|

|

8.

|

Y HuangKM DuZH XueCobalt chloride and low

oxygen tension trigger differentiation of acute myeloid leukemic

cells: possible mediation of hypoxia-inducible

factor-1alphaLeukemia1720652073200310.1038/sj.leu.2403141

|

|

9.

|

EJ KimYG YooWK YangTranscriptional

activation of HIF-1 by RORalpha and its role in hypoxia

signalingArterioscler Thromb Vasc

Biol2817961802200810.1161/ATVBAHA.108.17154618658046

|

|

10.

|

A LanX LiaoL MoHydrogen sulfide protects

against chemical hypoxia-induced injury by inhibiting ROS-activated

ERK1/2 and p38MAPK signaling pathways in PC12 cellsPLoS

One6e25921201110.1371/journal.pone.002592121998720

|

|

11.

|

H EndohT KanekoH NakamuraImproved cardiac

contractile functions in hypoxia-reoxygenation in rats treated with

low concentration Co(2+)Am J Physiol Heart Circ

Physiol279H2713H2719200011087225

|

|

12.

|

F KerendiPM KirshbomME HalkosThoracic

Surgery Directors Association Award. Cobalt chloride pretreatment

attenuates myocardial apoptosis after hypothermic circulatory

arrestAnn Thorac

Surg8120552062200610.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.01.059

|

|

13.

|

ZQ ZhaoJS CorveraME HalkosInhibition of

myocardial injury by ischemic postconditioning during reperfusion:

comparison with ischemic preconditioningAm J Physiol Heart Circ

Physiol285H579H588200310.1152/ajpheart.01064.200212860564

|

|

14.

|

JM DuckhamHA LeeThe treatment of

refractory anaemia of chronic renal failure with cobalt chlorideQ J

Med452772941976940922

|

|

15.

|

JW FisherJW LangstonEffects of

testosterone, cobalt and hypoxia on erythropoietin production in

the isolated perfused dog kidneyAnn NY Acad

Sci1497587196810.1111/j.1749-6632.1968.tb15139.x5240755

|

|

16.

|

WE JandaW FriedCW GurneyCombined effect of

cobalt and testosterone on erythropoiesisProc Soc Exp Biol

Med120443446196510.3181/00379727-120-305585856423

|

|

17.

|

Z YangC YangL XiaoNovel insights into the

role of HSP90 in cytoprotection of H2S against chemical

hypoxia-induced injury in H9c2 cardiac myocytesInt J Mol

Med28397403201121519787

|

|

18.

|

R Eyssen-HernandezA LadouxC

FrelinDifferential regulation of cardiac heme oxygenase-1 and

vascular endothelial growth factor mRNA expressions by hemin, heavy

metals, heat shock and anoxiaFEBS

Lett382229233199610.1016/0014-5793(96)00127-58605975

|

|

19.

|

D KatayoseS IsoyamaH FujitaSeparate

regulation of heme oxygenase and heat shock protein 70 mRNA

expression in the rat heart by hemodynamic stressBiochem Biophys

Res Commun191587594199310.1006/bbrc.1993.12588461015

|

|

20.

|

IM AhmadN Aykin-BurnsJE SimMitochondrial

O2*-and H2O2 mediate

glucose deprivation-induced stress in human cancer cellsJ Biol

Chem28042544263200515561720

|

|

21.

|

CH ConradWW BrooksJS IngwallInhibition of

hypoxic myocardial contracture by Cobalt in the ratJ Mol Cell

Cardiol16345354198410.1016/S0022-2828(84)80605-76726823

|

|

22.

|

L XiM TaherC YinCobalt chloride induces

delayed cardiac preconditioning in mice through selective

activation of HIF-1alpha and AP-1 and iNOS signalingAm J Physiol

Heart Circ

Physiol287H2369H2375200410.1152/ajpheart.00422.200415284066

|

|

23.

|

Z CaiDJ ManaloG WeiHearts from rodents

exposed to intermittent hypoxia or erythropoietin are protected

against ischemia-reperfusion

injuryCirculation1087985200310.1161/01.CIR.0000078635.89229.8A12796124

|

|

24.

|

CJ ParsaA MatsumotoJ KimA novel protective

effect of erythropoietin in the infarcted heartJ Clin

Invest1129991007200310.1172/JCI1820014523037

|

|

25.

|

L CalvilloR LatiniJ KajsturaRecombinant

human erythropoietin protects the myocardium from

ischemia-reperfusion injury and promotes beneficial remodelingProc

Natl Acad Sci USA10048024806200310.1073/pnas.063044410012663857

|

|

26.

|

WI SivitzDD LundB YorekPretranslational

regulation of two cardiac glucose transporters in rats exposed to

hypobaric hypoxiaAm J Physiol263E562E56919921415537

|

|

27.

|

J YbarraA BehroozA

GabrielGlycemia-lowering effect of cobalt chloride in the diabetic

rat: increased GLUT1 mRNA expressionMol Cell

Endocrinol133151160199710.1016/S0303-7207(97)00162-79406861

|

|

28.

|

C YinL XiX WangSilencing heat shock factor

1 by small interfering RNA abrogates heat shock-induced

cardioprotection against ischemia-reperfusion injury in miceJ Mol

Cell Cardiol39681689200510.1016/j.yjmcc.2005.06.005

|

|

29.

|

NA WhitlockN AgarwalJX MaHSP27

upregulation by HIF-1 signaling offers protection against retinal

ischemia in ratsInvest Ophthalmol Vis

Sci4610921098200510.1167/iovs.04-004315728570

|

|

30.

|

JD JiaoV GargB YangNovel functional role

of heat shock protein 90 in ATP-sensitive K+

channel-mediated hypoxic preconditioningCardiovasc

Res77126133200810.1093/cvr/cvm02818006464

|

|

31.

|

JM McCordOxygen-derived free radicals in

postischemic tissue injuryN Engl J

Med312159163198510.1056/NEJM1985011731203052981404

|

|

32.

|

DR GreenJC ReedMitochondria and

apoptosisScience28113091312199810.1126/science.281.5381.13099721092

|

|

33.

|

J ChenXQ TangJL ZhiCurcumin protects PC12

cells against 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium ion-induced apoptosis by

Bcl-2-mitochondria-ROS-iNOS

pathwayApoptosis11943953200610.1007/s10495-006-6715-516547587

|

|

34.

|

K ZhaoGM ZhaoD WuCell-permeable peptide

antioxidants targeted to inner mitochondrial membrane inhibit

mitochondrial swelling, oxidative cell death, and reperfusion

injuryJ Biol Chem2793468234690200410.1074/jbc.M402999200

|

|

35.

|

SL ChenCT YangZL YangHydrogen sulphide

protects H9c2 cells against chemical hypoxia-induced injuryClin Exp

Pharmacol

Physiol37316321201010.1111/j.1440-1681.2009.05289.x19769612

|

|

36.

|

JC YoungNJ HoogenraadFU HartlMolecular

chaperones Hsp90 and Hsp70 deliver preproteins to the mitochondrial

import receptor

Tom70Cell1124150200310.1016/S0092-8674(02)01250-312526792

|