Introduction

Liver cancer is one of the most prevalent types of

cancer. Hepatoblastoma is a malignant liver cancer with a poor

prognosis and is most commonly diagnosed in the first 3 years of

life of children. Moreover, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the

third leading cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide (1). This statistic is attributed to the

fact that a large number of patients are diagnosed with HCC at an

advance stage, which leads to a poor prognosis. For these patients,

systemic chemotherapy is considered an alternative option. However,

HCC is relatively chemotherapy-resistant and patients receiving

chemotherapy still have an unsatisfactory prognosis and a high rate

of recurrence (2). Some studies

have demonstrated that HCC resistance to chemotherapy may be due to

the presence of hepatic tumor-derived cells, which are commonly

considered to be responsible for tumor initiation, self-renewal,

metastasis and chemoresistance (3). Therefore, a greater understanding of

the mechanisms of tumor chemore-sistance and potential molecular

targets is urgently required.

Hepatic lipase (LIPC), a member of the lipase gene

family, is a hydrolytic enzyme with lipolytic and ligand function

and plays an important role in lipoprotein metabolism and cytokine

homeostasis (4). LIPC has been

reported to be closely associated with coronary artery disease and

diabetes (5). Recent studies have

demonstrated the effects of LIPC in cancer progression and

metastasis. A previous study suggested that monoacylglycerol lipase

(MAGL) promotes tumor cell proliferation, invasion and migration by

regulating a fatty acid network with carcinogenesis signaling

molecules (6). Another study by

Ding et al reported that apolipoprotein B mRNA editing

enzyme catalytic polypeptide-like 3G (APOBEC3G), S100P, LIPC and

CD133 played a critical role in promoting liver metastasis of

colorectal cancer, and could be potential markers for predicting

the likelihood of hepatic metastasis (7). More recently, another study

indicated that the intratumoral level of LIPC positively correlated

with the prognosis of non-small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC), and

patients with relatively low expression of LIPC may benefit from

chemotherapy (8). However, the

precise role of LIPC in tumor development and chemotherapy remains

unknown. CD133 has been commonly considered as a marker of

tumor-derived cells in various tumors including liver cancer and

colon cancer. It has been also found to be involved in

chemoresistance (9,10). Ding et al demonstrated that

both LIPC and CD133 promote the liver metastasis of colorectal

cancer (7). However, no evidence

has been provided as to whether they function interactively or

independently in tumors.

In this study, we aimed to investigate the role of

LIPC in cancer cells and to elucidate the potential underlying

mechanisms. We demonstrate that the downregulation of LIPC

expression significantly decreases cell proliferation and the

colony formation rate of HepG2 cells. The expression of CD133

significantly decreased in short hairpin RNA (shLIPC)-transfected

HepG2 cells compared with control short hairpin RNA

(shCON)-transfected HepG2 cells. The knockdown of LIPC increased

resistance to doxorubicin and 5-floxuridine (5-FU). Microarray

analysis of gene expression profiles in the

shCON/shLIPC-transfected HepG2 cells identified differentially

expressed genes for further analysis.

Materials and methods

Cell lines, cell culture and

reagents

All cells [human colorectal cancer cells SW620

(CCL-227), SW480 (CCL-228), LoVo (CCL-229), LS174T (CL-188), HCT

116 (CCL-247), HT29 (HTB-38), hepatoblastoma cells HepG2 (HB-8065),

and mouse colorectal cancer cells CT26 (CRL-2638)] were purchased

from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA,

USA). The cells were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium

(DMEM; Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA), supplemented with 10% fetal

bovine serum (FBS). The cells were maintained at 37°C under 5%

CO2. Doxorubicin and 5-FU were dissolved in dimethyl

sulfoxide (DMSO) (all from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA) and stored as

10 mmol/l stock solutions in the dark at −20°C.

LIPC activity assay

The cell culture supernatants were collected and the

activity of LIPC was measured using a human hepatic triglyceride

lipase (HTGL) enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit

(Cusabio, Wuhan, China) according to the manufacturer’ s

instructions.

RNA extraction and RT-qPCR

Total RNA was extracted from the cells using TRIzol

reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and First Strand cDNA

synthesis was performed with a PrimeScript™ RT reagent kit

(DRR037A; Takara, Shiga, Japan). qPCR was performed using

SYBR-Green Premix Ex Taq (RR091A; Takara) and analyzed with the

LC480 system (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). Specific primer sequences

were designed using NCBI primerblast for: LIPC, 5′-TCC CAA AGT ACC

CAA AGG C-3′ (sense) and 5′-ACT CCA GCC TTG ACC CAC TC-3′

(antisense); glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), 5′-TGG

AAG GAC TCA TGA CCA CA-3′ (sense) and 5′-TTC AGC TCA GGG ATG ACC

TT-3′ (anti-sense). The qPCR conditions were 95°C for 5 min,

followed by 45 cycles of 95°C for 10 sec, 58°C for 30 sec, and 72°C

for 20 sec. A final extension at 72°C for 5 min was included before

a temperature ramp from 72 to 95°C at 0.1°C/sec. GAPDH was used as

an internal reference gene, and the 2−ΔΔCq method

(11) was used to calculate cycle

threshold values. All experiments were repeated at least 3 times

and the data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD).

Western blot analysis

Total cellular protein was extracted from the cells

using RIPA buffer containing 1X protease inhibitor cocktail (Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and 1X PMSF. The protein

concentration was determined using a BCA protein assay kit

(Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, Shanghai, China). Forty

micrograms of protein lysate were separated by 10% sodium dodecyl

sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE)

electrophoresis and transferred onto PVDF membranes (Millipore,

Billerica, MA, USA). Mouse anti-human LIPC (1:500, sc-21740) and

mouse anti-human β-actin (1:5,000, sc-47778) (both from Santa Cruz

Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA, USA) were used as primary

antibodies, followed by incubation with a secondary antibody (goat

anti-mouse IgG-HRP; 1:5,000, sc-2005; Santa Cruz Biotechnology,

Inc.). After washing, the immunoreactive bands were detected by

enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) reagents (Millipore).

Lentiviral transduction and construction

of stable cell lines

We selected the HepG2 cell line for shRNA

interference assays as the HepG2 cells were found to have a high

expression of LIPC. For the knockdown experiments, a LIPC siRNA

lentiviral vector and a control vector were constructed (GenePharma

Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China). The mouse LIPC gene sequence

(NM-008280) was amplified by PCR and cloned into the pCMV6-Kan/Neo

plasmid (OriGene, Rockvile, MD, USA). A specific LIPC siRNA

sequence was designed as: 5′-GGA GAA ACC CAG CAA AGA AdTdT-3′

(10). Both constructs were

confirmed by DNA sequencing before use. To make the lentiviral

particle, LIPC/control shRNA plasmid constructs were co-transfected

with the helper plasmids pGag/Pol, pRev and pVSV-G into 293T cells

(purchased from ATCC) using RNAi-Mate transfection reagent

(GenePharma Co., Ltd.) according to the manufacturer’s

instructions. The viral particles were collected and the lentiviral

titer was determined by quantifying the EGFP-positive cells by flow

cytometry analysis following infection of the 293T cells. To

prepare stably transfected cell lines, HepG2 cells at 40–60%

confluence (in 24-well plates) were transfected with moieties of

infection (MOI) of 10, in the presence of 5 µg/ml polybrene

(Sigma). G418 was used to select cells at a concentration of 400

g/ml. The efficiency of transfection was determined by measuring

the LIPC levels by western blot analysis after 48–72 h.

Flow cytometric analysis of CD133

expression

To determine the expression of the tumor-derived

cell biomarker, CD133, single cell suspensions were collected and

re-suspended in 200 µl at a density of 1×106 cells/ml in

phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.1–0.5% bovine serum

albumin (BSA). The cells were incubated with antigen presenting

cell x(APC)-conjugated anti-human CD133 (130-090-826; Miltenyi

Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) for 30 min at 4°C in the dark.

Cells incubated with anti-mouse-IgG (sc-2005; Santa Cruz

Biotechnology, Inc.) were used as the isotype control. The cells

were washed with pre-chilled PBS twice and re-suspended for flow

cytometric analysis. For detecting CD133 expression in the

cytoplasm, the cells were first fixed with 100 µl 1%

permeabilization buffer in PBS before staining with CD133

antibodies. The assay was repeated 3 times.

Cell proliferation and colony formation

assay

The HepG2 cells transfected with shLIPC or shCON

vectors were seeded into a 96-well plate at a density of 5,000

cells/well and incubated for 72 h. Subsequently, 20 µl of

3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT)

(0.5 mg/ml) was added and incubated for another 4 h at 37°C. The

medium was aspirated and 150 ml DMSO was added to dissolve the

formazan crystals. After the crystals were completely dissolved,

the absorbance was measured using a microplate reader (ELX800;

Bio-Tek Instruments, Winooski, VT, USA). The number of viable cells

was expressed as a percentage of absorbance. For colony formation

assays, transfected cells were plated in triplicate into 6-well

plates at a density of 200–800 cells/well and incubated for 14 days

(12). After being washed and

fixed with 70% methanol for 15 min, the cells colonies were stained

with 0.1–0.5% crystal violet for 10–15 min. The plates were washed

with water and left to dry. The number of colonies containing

>50 cells was counted. The experiment was repeated 3 times.

Drug resistance

The cells were treated with or without doxorubicin

(0.03–0.3 µM) and 5-FU (0.2–2.0 µM) and further incubated for 48 h.

The proliferation of both the shLIPC- and shCON-transfected HepG2

cells was determined by MTT assay as described above.

cDNA microarray analysis

Microarray experiments were performed by RiboBio

Co., Ltd. (Guangzhou, China). Initially, total RNA of the

shLIPC/shCON-transfected HepG2 cell lines was extracted and the

quantity of RNA was determined using an Agilent 2200 Bioanalyzer

(Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Three independent samples of each

group were prepared and an equal amount of total RNA from each

preparation was pooled, respectively. The CDNA was synthesized and

labeled with Cy3/Cy5, and randomly hybridized to a RiboArray™

Custom array 1×40K (RiboBio, Guangzhou, China) according to the

manufacturer’s instructions. The hybridized microarray was scanned

and the data were analyzed and normalized. The differentially

expressed genes were identified at a fold change ≥2.

GO analysis and pathway enrichment

The gene ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of

Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analysis of the

differentially expressed genes were performed using DAVID

tools.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 20

software. All data were presented as the means ± SD of three

independent experiments. For cell functional assays, the 3

significance between the shLIPC and shCON groups were determined by

a two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test. For chemo-resistance

experiments, data were analyzed with two-factor variance analysis

and Student-Newman-Keuls (SNK) test. P-values <0.05 were

considered statistically significant.

Results

Differential expression of LIPC in cancer

cells

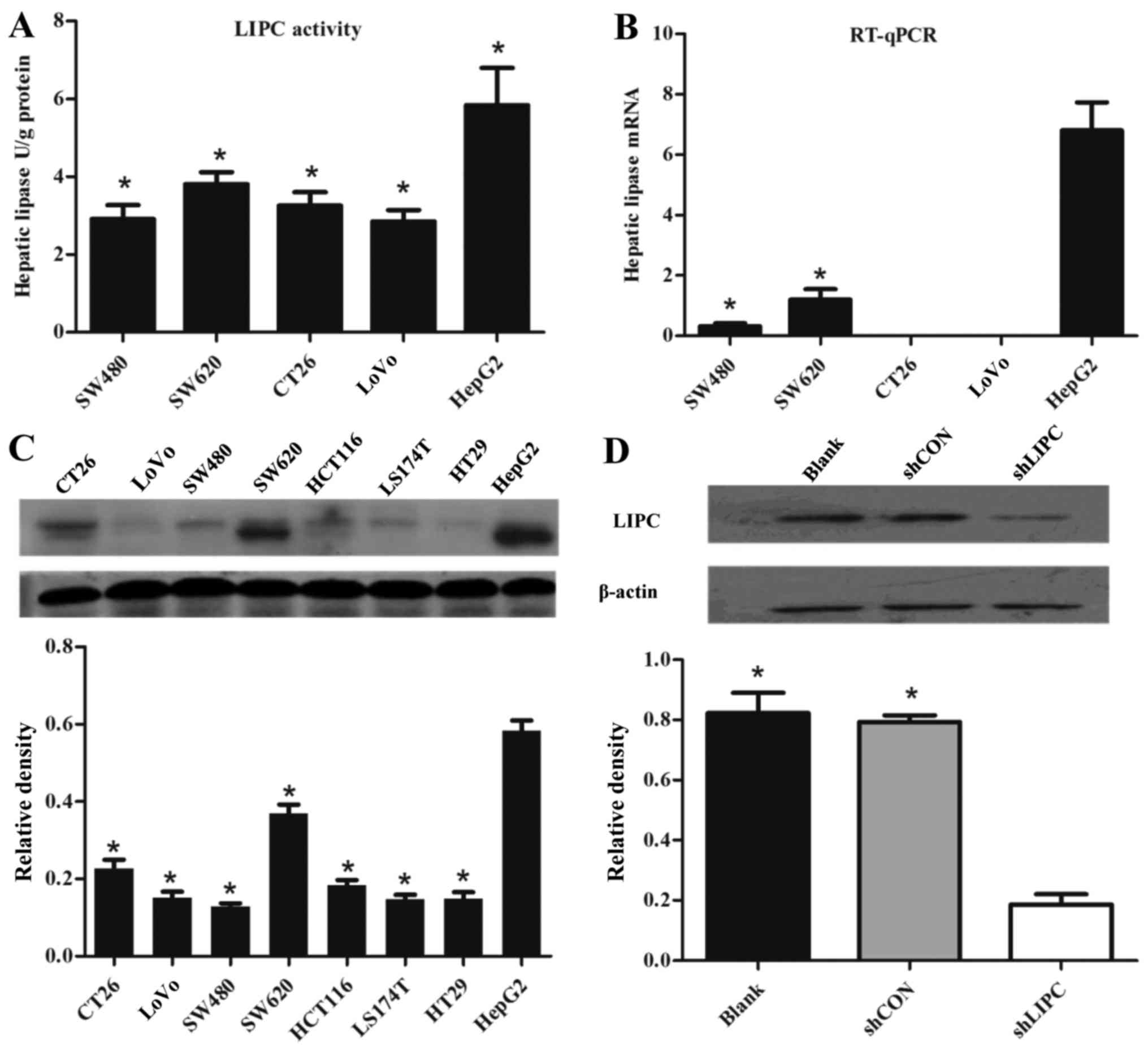

LIPC activity was examined in colorectal cancer

cells (human SW620, SW480 and LoVo cells, and mouse CT26 cells) and

hepatoblastoma HepG2 cells. The HepG2 cells exhibited a 1.92-fold

higher LIPC activity compared to the other cells (P<0.001)

(Fig. 1A). The LIPC mRNA levels

in the HepG2 cells determined by RT-qPCR were the highest among the

cell lines (P<0.001) (Fig.

1B). Similarly, the protein levels of LIPC in the HepG2 cells

were significantly increased compared with the other cell lines

(P<0.001) (Fig. 1C). The HepG2

cells exhibited relatively higher levels of LIPC compared to the

other cell lines, and were thus selected as a suitable model for

shRNA interference assays. The protein levels of LIPC were

determined by western blot analysis. Compared with the

shCON-transfected cells, the mRNA and protein levels of LIPC were

significantly decreased in the shLIPC-transfected cells

(P<0.001) (Fig. 1D).

Downregulation of LIPC decreases the

expression of CD133

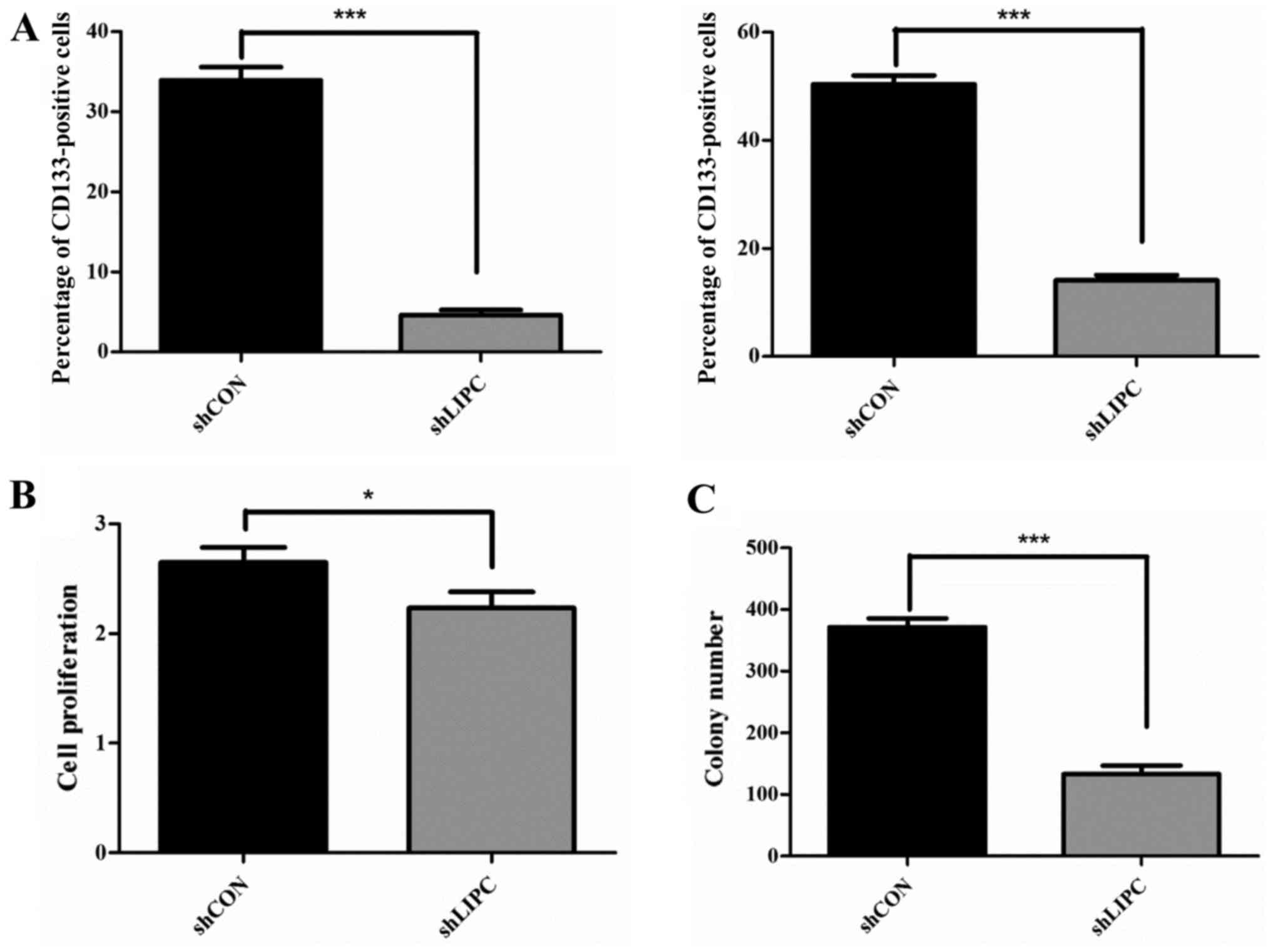

The association between LIPC and the tumor-derived

cell marker, CD133, was explored. CD133 expression was decreased

significantly in the HepG2 cells transfected with shLIPC

(4.62±0.36%) compared to the HepG2 shCON-transfected cells

(33.94±0.94%) (P<0.001) (Fig.

2A, left panel). Similar results were observed for CD133

expression in the cytoplasm. The expression of CD133 in the

cytoplasm of the HepG2 shLIPC-transfected cells (14.11±0.57%) was

significantly decreased compared to that of the HepG2

shCON-transfected cells (50.35 ±0.97%) (P<0.001) (Fig. 2A, right panel).

Downregulation of LIPC decreases cell

proliferation and colony formation

MTT assays indicated that cell proliferation was

slightly decreased after LIPC knockdown compared to the respective

control groups (P<0.05) (Fig.

2B). We also performed a colony formation assay to analyze the

proliferative potential of single cells after the silencing of LIPC

in vitro. The size of single colony formation in

shLIPC-transfected HepG2 cells was markedly smaller and the number

of colonies containing ≥50 cells was reduced by 64.4±2.7% compared

to the shCON-transfected cells (P<0.001) (Fig. 2C). These data suggest that the

knockdown of LIPC inhibits the proliferation and colony formation

of HepG2 cells.

Downregulation of LIPC increases

chemoresistance in HepG2 cells

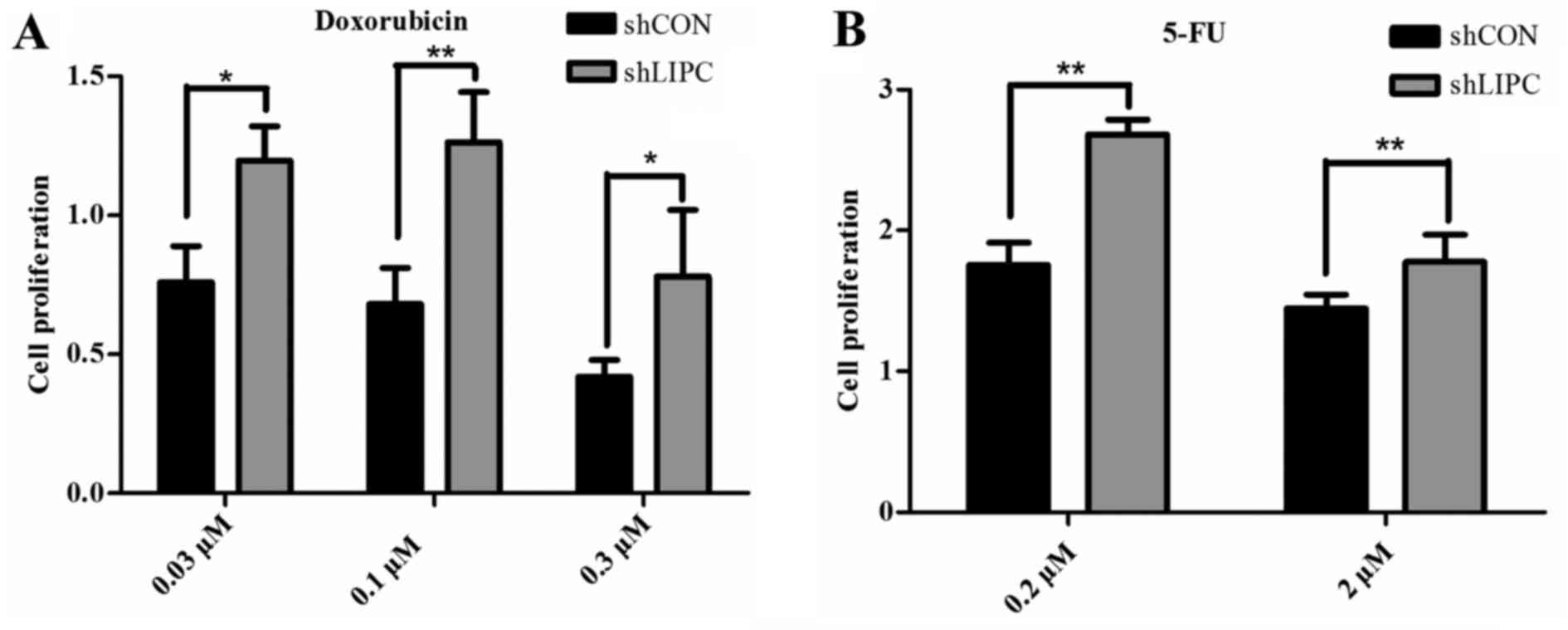

Cells transfected with shLIPC exhibited an increased

cell viability following treatment with 0.03, 0.1 and 0.3 µM

doxorubicin compared to the shCON-transfected cells (P<0.05)

(Fig. 3A). Similar results were

observed in cells treated with 0.2 and 2.0 µM 5-FU (P<0.01)

(Fig. 3B). The current data

suggest that the downregulation of LIPC enhances resistance to

doxorubicin and 5-FU in HepG2 cells. We observed no significant

differences in drug resistance assays following LIPC upregulation

(data not shown).

Genes differentially expressed following

the knockdown of LIPC

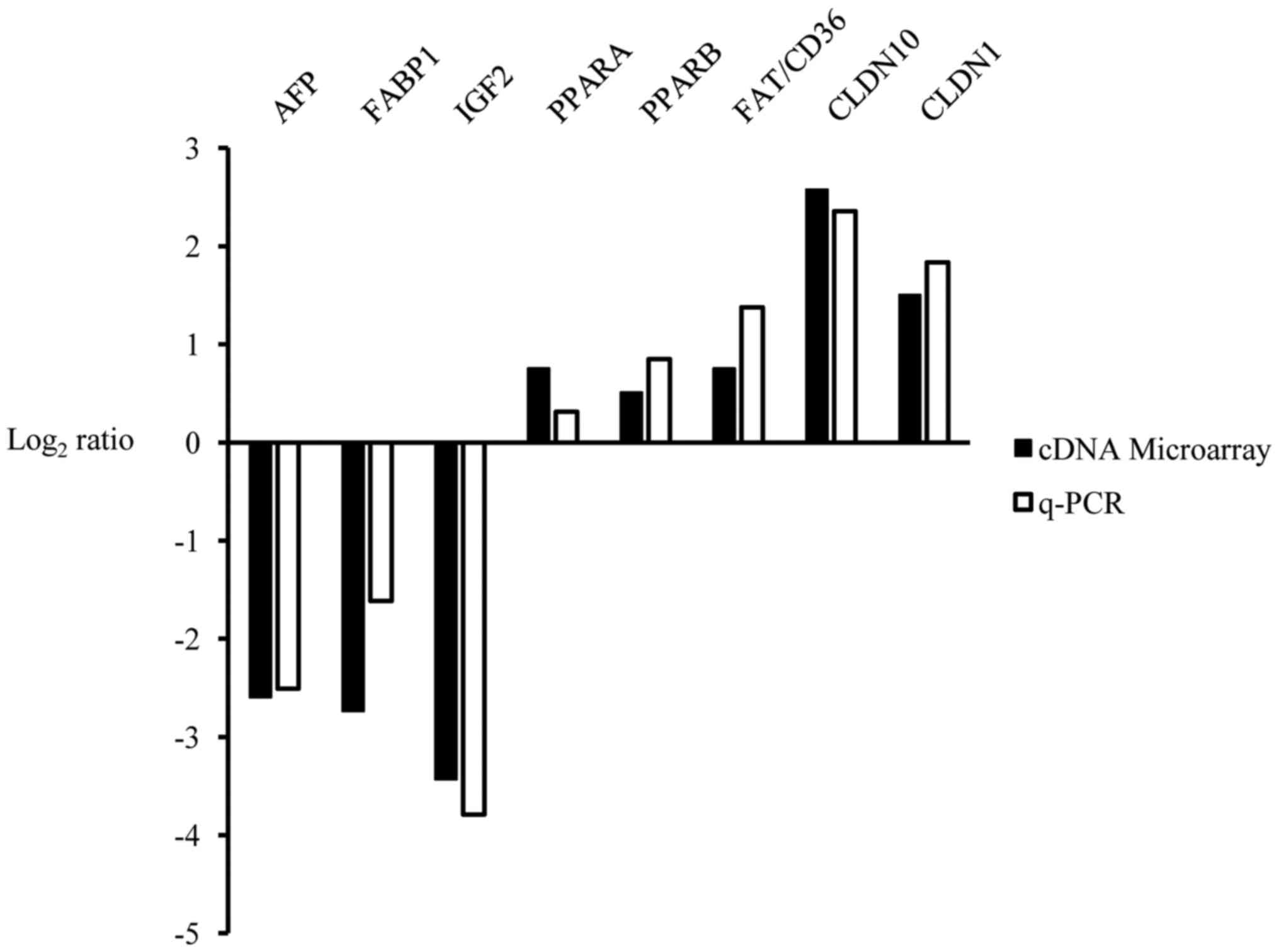

We found 1,602 genes that were upregulated and 716

genes that were downregulated in the shLIPC-transfected cells

compared with the shCON-transfected cells using a log2

(fold change) ≥1 as the standard selection criteria. Detailed gene

lists of the top 25 of the most differentially expressed genes are

summarized in Table I. Eight

candidate genes from the microarray analysis were selected for

validation by RT-qPCR (Fig.

4).

| Table ITop 25 upregulated and downregulated

transcripts in HepG2 cells after the knockdown of hepatic lipase

(LIPC). |

Table I

Top 25 upregulated and downregulated

transcripts in HepG2 cells after the knockdown of hepatic lipase

(LIPC).

| Upregulated

accession | Downregulated gene

ID | Gene symbol | Ratio | Accession | Gene ID | Gene symbol | Ratio |

|---|

| NM_007342 | 11097 | NUPL2 | 22.08 | NM_001005482 | 79310 | OR5H2 | 12.12 |

| NM_001024644 | 2829 | XCR1 | 17.16 | NR_038404 | 100506801 | LOC100506801 | 11.08 |

| NR_037897 | 386627 | FLJ38109 | 14.97 | NM_001127598 | 3481 | IGF2 | 10.80 |

| XR_132758 | 440157 | LOC440157 | 9.665 | NM_001135189 | 3267 | AGFG1 | 10.30 |

| NM_181706 | 120526 | DNAJC24 | 9.400 | NM_182715 | 6856 | SYPL1 | 9.487 |

| NR_029975 | 574413 | MIR409 | 8.755 | NM_021871 | 2243 | FGA | 8.808 |

| NM_001214 | 750 | C16orf3 | 8.626 | NM_014628 | 9587 | MAD2L1BP | 7.579 |

| NM_033306 | 837 | CASP4 | 8.566 | NM_004536 | 4671 | NAIP | 7.358 |

| XR_159202 | 100506518 | LOC100506518 | 8.246 | NM_001443 | 2168 | FABP1 | 6.662 |

| NM_001170796 | 79752 | ZFAND1 | 7.770 | NM_000509 | 2266 | FGG | 6.559 |

| NM_007224 | 11247 | NXPH4 | 7.133 | NM_000612 | 3481 | IGF2 | 6.381 |

| NM_003644 | 8522 | GAS7 | 6.800 | NM_001134 | 174 | AFP | 6.050 |

| NM_001136508 | 284546 | C1orf185 | 6.701 | NM_001100912 | 222389 | BEND7 | 5.778 |

| NM_022746 | 64757 | MARC1 | 6.611 | NR_003512 | 723961 | INS-IGF2 | 5.378 |

| NR_037456 | 100500802 | MIR3685 | 6.551 | NM_019855 | 56344 | CABP5 | 5.132 |

| XR_133419 | 100653086 | LOC100653086 | 6.527 | NM_000327 | 6094 | ROM1 | 5.128 |

| NM_153448 | 80712 | ESX1 | 6.475 | NM_001007559 | 6760 | SS18 | 5.118 |

| NM_206922 | 401262 | CRIP3 | 6.406 | NM_00101172 | 144983 | HNRNPA1L2 | 5.044 |

| NM_014294 | 23471 | TRAM1 | 6.101 | NR_036141 | 100422870 | MIR3180-1 | 5.007 |

| XM_003403794 | 100509542 | LOC100509542 | 6.034 | NR_033832 | 340113 | LOC340113 | 4.978 |

| NM_015474 | 25939 | SAMHD1 | 6.015 | NM_000014 | 2 | A2M | 4.824 |

| NM_006984 | 100500882 | CLDN10 | 5.983 | NM_001063 | 7018 | TF | 4.809 |

| NR_037440 | 9071 | MIR3667 | 5.968 | NM_001025253 | 7163 | TPD52 | 4.751 |

| NR_015364 | 441204 | LOC441204 | 5.911 | NM_001256654 | 7594 | ZNF43 | 4.493 |

| NR_026562 | 55969 | C20orf24 | 5.853 | NR_001443 | 339240 | LOC339240 | 4.422 |

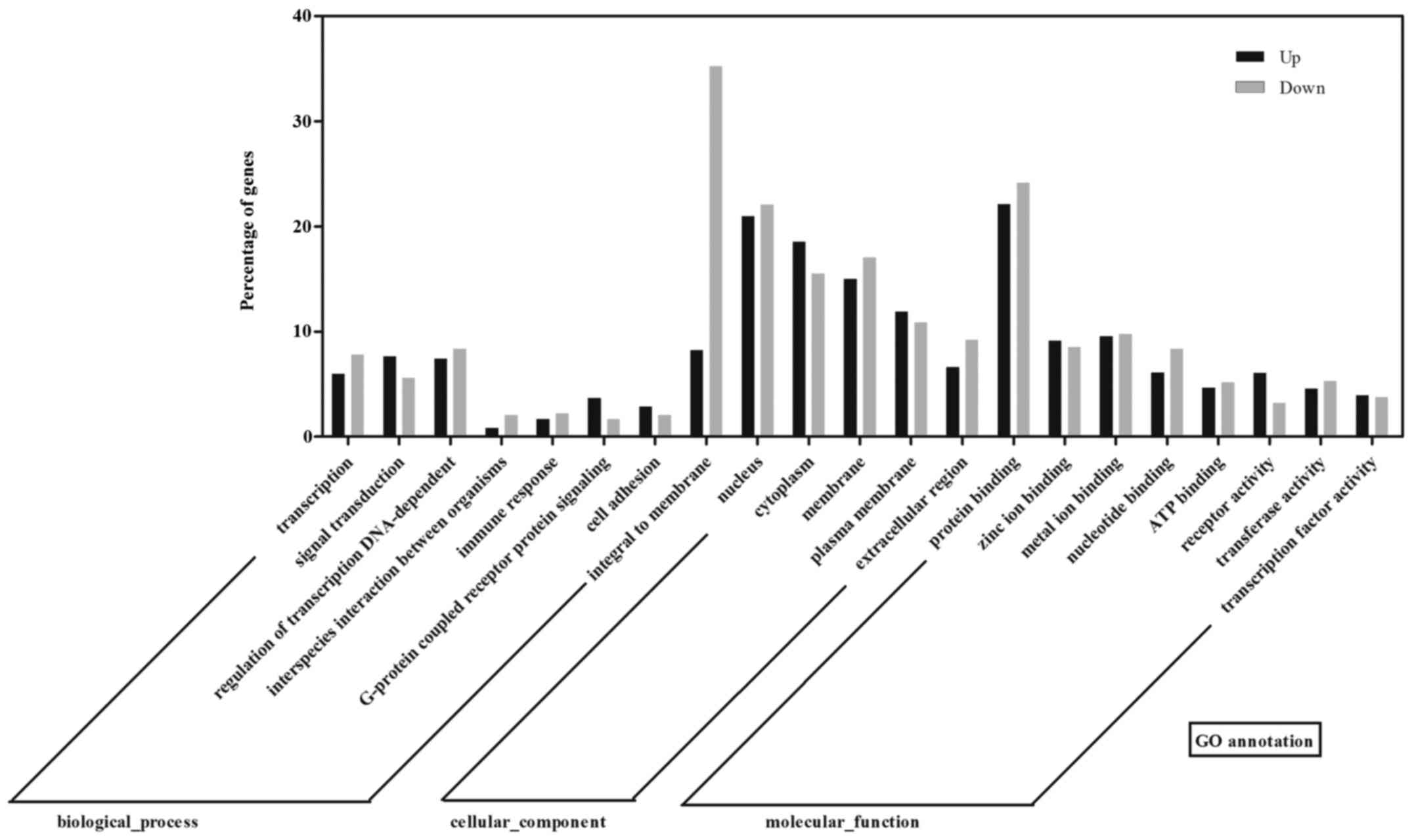

To examine the function of the differentially

expressed mRNAs and identify the biological pathway involved, the

data were further analyzed using Gene Ontology (GO) and the Kyoto

Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) database. GO analysis

revealed that the differentially expressed genes fell into the

following categories: Regulation of transcription, NA-dependent,

signal transduction in biological process ontology; integral to

membrane, nucleus and cytoplasm in cellular component ontology; and

protein binding, zinc ion binding, and metal ion binding in

molecular function ontology (Fig.

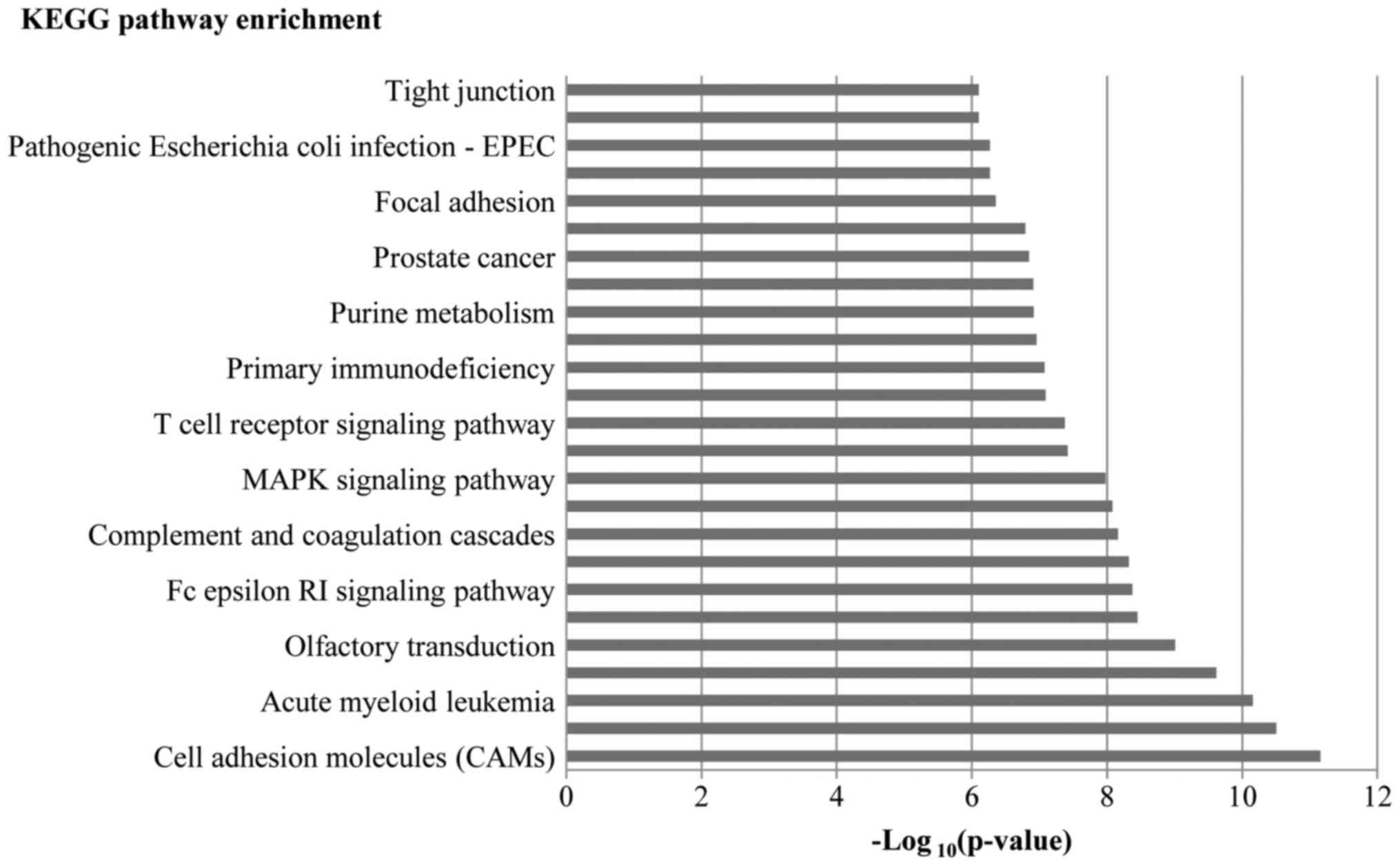

5). In KEGG analysis, a total of 124 pathways were regulated by

the differentially expressed genes, which mainly involved cell

adhesion molecules (CAMs), axon guidance, the vascular endothelia

growth factor (VEGF) signaling pathway, and the Wnt signaling

pathway. The top 12 regulated pathways are listed in Fig. 6.

Discussion

Little is known about the mechanisms of action of

LIPC in cancer cells. Previous studies reported that serum lipase

activities were elevated before detection of tumor relapse or

progression (13–15). These findings suggest that lipase

may play a tumor marker-like role and contributed to the early

detection of malignant neoplasm. In this study, we demonstrated

that the downregulation of LIPC inhibited CD133 expression in and

the colony formation of HepG2 cells.

CD133, also known as prominin-1, is considered a

marker for a tumor-derived cell population of brain tumors

(16), melanoma (17), prostate (18,19), colon (20,21) and liver cancers (22,23). A number of studies have indicated

that CD133(+) cells are capable of greater tumorigenicity and a

higher incidence of metastasis compared to CD133(−) cells. O’Brien

et al demonstrated that only CD133(+) colon cancer cells

were able to initiate tumor growth in immunodeficient mice

(20). Bao et al found

that CD133(+) glioma cancer cells promoted tumor angiogenesis

through VEGF (24). However, the

role of CD133 as a tumor-derived cell marker is controversial. In

fact, a number of studies have indicated that the CD133(−)

population is equally capable, if not more aggressive, of tumor

initiation (25,26). Jaksch et al argued that

differential CD133 expression may be a marker of different cell

cycle stages rather than a marker of stable tumor-derived cells

(27). Taken together, these

studies suggest that too much attention has been placed on the role

of CD133 for the identification of tumor-derived cells, while the

actual biological functions of this molecule remain unknown. A

previous study by Ding et al revealed that both LIPC and

CD133 contributed to liver metastasis (7). The data from the present study

revealed that a decreased CD133 expression was associated with LIPC

deficiency in HepG2 cells, which was demonstrated to inhibit cell

proliferation and decrease the colony formation rates.

However, in terms of chemoresistance, there was no

result that was consistent with that of previous literature

(8), since the reduction in CD133

expression did not decrease chemoresistance to doxorubicin and

5-FU. It might be that it is LIPC not CD133, which plays a role in

regulating drug resistance. As regards the use of CD133 as a stable

marker for tumor-derived cells, some previous studies have

indicated that the biological behavior of tumor-derived cells is

influenced by the surrounding microenvironment, which is affected

by tumor stages, histopathological types, nutritional conditions

and therapies (28). We found

that in LIPC-silenced cells, a higher percentage of

‘membrane-integrated’ genes were downregulated and more cell

adhesion molecules were regulated. Under the conditions of cell

culture, different surrounding microenvironments affecting cell

adhesion in vitro might result in such drug resistance

results. In the next step, the drug resistance in vivo is

worth investigating.

One intriguing finding of the present study was that

the CAM pathway was demonstrated to be the most significantly

regulated pathway by the differentially expressed genes. Moreover,

the mRNA levels of CLDN10 and CLDN1, which participate in the CAMs

pathway, were found to be almost six times and three times higher

in shLIPC cells compared to shCON cells, respectively. Some

previous studies have indicated that a high expression of CLDN10

was associated with the recurrence of primary hepatic carcinoma,

and CLDN10 enhanced cell invasiveness and motility (29,30). Suh et al found that CLDN1

could promote metastasis of liver cancer by inducing

epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) (31). However, in the present study, we

did not see obvious differences in cell migration after the

knockdown of LIPC (data not shown). We speculate that the CAM

pathway may have important implications for the mechanisms involved

in the tumor colony formation induced by LIPC expression.

A limitation of our study was that we performed the

experiments in a hepatoma cell in culture, which may present

distinct biological features without the regulation of the

surrounding microenvironment. Another limitation is that data on

more cell lines were not provided in this study. Further studies

using animal models and clinical tissue specimens are required in

the future. The present findings reveal the potential role of LIPC

as a therapeutic target in liver cancer. The association of LIPC

and CD133 remains to be determined, and further studies are

warranted to determine the specific mechanisms through which LIPC

participates in tumor progression.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Medjaden

Bioscience Limited for the English language editing service.

Funding

The study was sponsored by the Returned Scientific

Research Foundation of the Ministry of Education and National

Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 81471080) to B.N.

This study was supported by the Guangzhou Pilot Project of Clinical

and Translational Research Center (early gastrointestinal cancers,

no. 7415696196402) and the Guangdong Provincial Bio-engineering

Research Center for Gastroenterology Diseases.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current

study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable

request.

Authors’ contributions

XL, JZ and YF finished most of the experiments and

wrote the manuscript. JW and HZ performed the FACS. FD constructed

the stable cell lines. BJ, JW and BN designed the experiments and

revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward

E and Forman D: Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin.

61:69–90. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Asghar U and Meyer T: Are there

opportunities for chemotherapy in the treatment of hepatocellular

cancer? J Hepatol. 56:686–695. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Sukowati CH, Rosso N, Crocè LS and

Tiribelli C: Hepatic cancer stem cells and drug resistance:

Relevance in targeted therapies for hepatocellular carcinoma. World

J Hepatol. 2:114–126. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Wong H and Schotz MC: The lipase gene

family. J Lipid Res. 43:993–999. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Santamarina-Fojo S, González-Navarro H,

Freeman L, Wagner E and Nong Z: Hepatic lipase, lipoprotein

metabolism, and atherogenesis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol.

24:1750–1754. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Nomura DK, Long JZ, Niessen S, Hoover HS,

Ng SW and Cravatt BF: Monoacylglycerol lipase regulates a fatty

acid network that promotes cancer pathogenesis. Cell. 140:49–61.

2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Ding Q, Chang CJ, Xie X, Xia W, Yang JY,

Wang SC, Wang Y, Xia J, Chen L, Cai C, et al: APOBEC3G promotes

liver metastasis in an orthotopic mouse model of colorectal cancer

and predicts human hepatic metastasis. J Clin Invest.

121:4526–4536. 2011. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Galluzzi L, Goubar A, Olaussen KA, Vitale

I, Senovilla L, Michels J, Robin A, Dorvault N, Besse B, Validire

P, et al: Prognostic value of LIPC in non-small cell lung

carcinoma. Cell Cycle. 12:647–654. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Ma S, Lee TK, Zheng BJ, Chan KW and Guan

XY: CD133+ HCC cancer stem cells confer chemoresistance

by preferential expression of the Akt/PKB survival pathway.

Oncogene. 27:1749–1758. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Galluzzi L, Senovilla L, Vitale I, Michels

J, Martins I, Kepp O, Castedo M and Kroemer G: Molecular mechanisms

of cisplatin resistance. Oncogene. 31:1869–1883. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Livak and Schmittgen: Analysis of relative

gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the

2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Franken NA, Rodermond HM, Stap J, Haveman

J and van Bree C: Clonogenic assay of cells in vitro. Nat Protoc.

1:2315–2319. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Stein W, Bohner J and Bahlinger M: Macro

lipase - a new member of the family of immunoglobulin-linked

enzymes. J Clin Chem Clin Biochem. 25:837–843. 1987.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Muñoz-Perez M, Sarrion-Pelous D,

Jimenez-Jimenez J, Martinez-Montiel P and Gallego-Valdes M: Chronic

increased serum lipase in a patient with suspected pancreatic

adenocarcinoma. Clin Chem. 43:191–193. 1997.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Diani G, Poma G, Novazzi F, Zanirato S,

Porta C, Moroni M, Melzi d’ Eril GV and Moratti R: Increased serum

lipase with associated normoamylasemia in cancer patients. Clin

Chem. 44:1043–1045. 1998.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Singh SK, Clarke ID, Terasaki M, Bonn VE,

Hawkins C, Squire J and Dirks PB: Identification of a cancer stem

cell in human brain tumors. Cancer Res. 63:5821–5828.

2003.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Fang D, Nguyen TK, Leishear K, Finko R,

Kulp AN, Hotz S, Van Belle PA, Xu X, Elder DE and Herlyn M: A

tumorigenic subpopulation with stem cell properties in melanomas.

Cancer Res. 65:9328–9337. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Collins AT, Berry PA, Hyde C, Stower MJ

and Maitland NJ: Prospective identification of tumorigenic prostate

cancer stem cells. Cancer Res. 65:10946–10951. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Miki J, Furusato B, Li H, Gu Y, Takahashi

H, Egawa S, Sesterhenn IA, McLeod DG, Srivastava S and Rhim JS:

Identification of putative stem cell markers, CD133 and CXCR4, in

hTERT-immortalized primary nonmalignant and malignant tumor-derived

human prostate epithelial cell lines and in prostate cancer

specimens. Cancer Res. 67:3153–3161. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

O’Brien CA, Pollett A, Gallinger S and

Dick JE: A human colon cancer cell capable of initiating tumour

growth in immunodeficient mice. Nature. 445:106–110. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Ricci-Vitiani L, Lombardi DG, Pilozzi E,

Biffoni M, Todaro M, Peschle C and De Maria R: Identification and

expansion of human colon-cancer-initiating cells. Nature.

445:111–115. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Suetsugu A, Nagaki M, Aoki H, Motohashi T,

Kunisada T and Moriwaki H: Characterization of CD133+

hepatocellular carcinoma cells as cancer stem/progenitor cells.

Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 351:820–824. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Yin S, Li J, Hu C, Chen X, Yao M, Yan M,

Jiang G, Ge C, Xie H, Wan D, et al: CD133 positive hepatocellular

carcinoma cells possess high capacity for tumorigenicity. Int J

Cancer. 120:1444–1450. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Bao S, Wu Q, Sathornsumetee S, Hao Y, Li

Z, Hjelmeland AB, Shi Q, McLendon RE, Bigner DD and Rich JN: Stem

cell-like glioma cells promote tumor angiogenesis through vascular

endothelial growth factor. Cancer Res. 66:7843–7848. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Shmelkov SV, Butler JM, Hooper AT, Hormigo

A, Kushner J, Milde T, St Clair R, Baljevic M, White I, Jin DK, et

al: CD133 expression is not restricted to stem cells, and both

CD133+ and CD133− metastatic colon cancer

cells initiate tumors. J Clin Invest. 118:2111–2120.

2008.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Meng X, Li M, Wang X, Wang Y and Ma D:

Both CD133+ and CD133− subpopulations of A549

and H446 cells contain cancer-initiating cells. Cancer Sci.

100:1040–1046. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Jaksch M, Múnera J, Bajpai R, Terskikh A

and Oshima RG: Cell cycle-dependent variation of a CD133 epitope in

human embryonic stem cell, colon cancer, and melanoma cell lines.

Cancer Res. 68:7882–7886. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Yang JD, Nakamura I and Roberts LR: The

tumor microenvironment in hepatocellular carcinoma: Current status

and therapeutic targets. Semin Cancer Biol. 21:35–43. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

29

|

Cheung ST, Leung KL, Ip YC, Chen X, Fong

DY, Ng IO, Fan ST and So S: Claudin-10 expression level is

associated with recurrence of primary hepatocellular carcinoma.

Clin Cancer Res. 11:551–556. 2005.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Ip YC, Cheung ST, Lee YT, Ho JC and Fan

ST: Inhibition of hepatocellular carcinoma invasion by suppression

of claudin-10 in HLE cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 6:2858–2867. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Suh Y, Yoon CH, Kim RK, Lim EJ, Oh YS,

Hwang SG, An S, Yoon G, Gye MC, Yi JM, et al: Claudin-1 induces

epithelial-mesenchymal transition through activation of the

c-Abl-ERK signaling pathway in human liver cells. Oncogene.

32:4873–4882. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|