Introduction

Ischemic cerebrovascular disease poses an increasing

threat to human health due to its high rate of incidence and

resulting disability (1). Rate of

recurrence and mortality associated with ischemic cerebrovascular

disease in Beijing, China was estimated as 27% (1). Cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury

is the leading cause of poor prognosis and high rate of severe

disability observed in the clinical practice (2-4).

The pathophysiology of this disease involves a variety of immune

cells of the central nervous system, mainly microglia, which

excessively activate and release a large quantity of oxygen free

radicals, inflammatory cytokines and other pro-inflammatory

compounds. The inflammatory injury then leads to neuronal death and

increases the damage resulting from the stroke (5-7).

Therefore, the focus of stroke research has become the

identification of an effective drug that can suppress inflammation

and improve patient prognosis.

Propofol is widely used in clinical practice as an

intravenous anesthetic due to its rapid induction and recovery

times (8). Recent research has

identified that the mechanism of action of propofol in sedation may

be associated with adenosine receptors (9,10).

Propofol inhibits adenosine reabsorption and increases the

concentrations of extracellular adenosine (11). Adenosine receptors A1 and A2 are

widely present in brain tissues. Subsequent to activation by

adenosine, A1 and A2 receptors exert neuroprotective effects by

increasing the intracellular cyclic adenosine monophosphate level,

promoting glycogen decomposition, inhibiting the activation of

central nervous system immune cells and improving the utilization

rate of metabolic substrates (12-14).

Therefore, in the present study, it was hypothesized

that propofol may activate the A2b receptor and inhibit microglial

activation, thereby reducing inflammatory injury following cerebral

infarction. Through a number of in vitro and in

vivoexperiments, alterations in the microglia activation

conditions, the levels of cytotoxic molecules and the expression of

inflammatory factors were detected following treatment with

propofol.

Materials and methods

Microglia isolation and culture

All procedures involving animals were reviewed and

approved by the Institutional Clinical Experiments Committee and

Institutional Review Board of the Hainan Medical University

(Haikou, China). A total of 90 male Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats

weighing 250-300 g were sacrificed by overdose of anesthetic at 3

days after birth. The microglia isolation procedure was performed

as previously described (15,16). Briefly, brains were removed and

washed with sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Meninges and

brain blood vessels were stripped, and the bilateral cerebral

cortex was cut into sections and digested for 10 min in trypsin.

Next, the cells were filtered (port size, 70 µm), seeded on

poly-L-lysine-coated flasks at a density of 4×105/ml and

cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM)-F12 medium

(Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA)

containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) at 37°C. After the cells had grown to cover the

bottom of the culture flasks, the flasks were shaken using a

rotatory shaker (Cellnest Shaker; Sino-Biotop, Shanghai, China) at

a speed of 200 rpm for 2 h at 37°C. Subsequently, cells

(1×106/ml) were collected and seeded into 250 ml flasks

and 6-well culture plates. Non-adherent cells were washed away

after 1 h, and fresh medium was added into all the culture flasks

and plates.

For in vitro experiments, five groups of

microglia were stimulated for 24-48 h respectively with 1

µg/ml lipopoly-saccharide (LPS; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA,

Darmstadt, Germany; n=8), with LPS and 1, 3 or 5 µg/ml

propofol (AstraZeneca plc, Cambridge, UK; n=8), or with LPS, 5

µg/ml propofol and 100 µM MRS agar (Sigma-Aldrich;

Merck KGaA) (n=8). The control group was only treated with DMEM/F12

medium (n=8).

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) and nitric

oxide (NO) detection

For ROS detection, pretreated microglia in each

group were incubated with the molecular probe

2′,7′-dichlorodihydro-fluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA; 10 µM;

Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) in serum-free medium at 37°C for 1 h in

the dark and then washed twice with PBS (17,18). ROS levels were measured at 492/520

nm using a microplate reader (Synergy HT; BioTek Instruments, Inc.,

Winooski, VT, USA).

The total NO levels in microglia were measured using

the Griess reagent kit (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.). Pretreated microglia were incubated with Griess reagent in

serum-free medium at 37°C for 20 min in the dark and then washed

twice with PBS (19). The control

group only contained complete medium and Griess reagent. NO levels

were measured at 540 nm using the microplate reader.

Immunofluorescence staining of

F-actin

Microglia from each test group were respectively

harvested, seeded (1×106/ml) and stimulated on glass

cover slips in 12-well poly-L-lysine-coated culture plates at 37°C.

Following fixation and permeabilization, 3% goat serum (R&D

Systems, Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA) was used to block non-specific

microglial proteins for 0.5 h at room temperature. Subsequently,

cells were stained with 5 µg/ml FITC-phalloidin (Invitrogen;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) at 24°C for 1 h and washed with PBS

(20-22). Next, 100 ng/ml DAPI (Invitrogen;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) was added into the culture plates,

and the nuclei were stained for 15 min. Finally, cells were imaged

using a confocal imaging system (Leica TCS SPE; Leica Microsystems

GmbH, Wetzlar, Germany).

MTT assay

Microglia from each test group were seeded on glass

coverslips in 96-well culture plates (1×104 cells per

well) at 37°C. Next, 5% MTT solution (0.2 mg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich;

Merck KGaA) was added into each well (20 µl per well) on the

following day. After 4 h, dimethyl sulfoxide (D4540; Sigma-Aldrich;

Merck KGaA) was added to each well (200 µl per well).

Finally, a microplate reader was used to measure the absorbance of

each well at 490 nm.

In vitro migration assay

Microglia were harvested and seeded into the upper

chamber of a 12-well Transwell plate (0.65 µm; Corning,

Inc., Corning, NY, USA). The lower chamber contained 1 µg/ml

LPS, LPS and 5 µg/ml propofol, or LPS with 5 µg/ml

propofol and 100 µM MRS agar. The control group only

contained culture medium. After 12-h incubation at 37°C, cells on

the lower chamber were fixed and stained with crystal violet. The

number of migrating microglia was observed under a light microscope

(Leica DVM6; Leica Microsystems GmbH).

In vitro scratch wound assay

Microglia (1×106/ml) were plated onto a

12-well tissue culture plate and allowed to reach near-confluence

overnight at 4°C. Mitomycin (5 µg/ml; Bio-Rad Laboratories,

Inc., Hercules, CA, USA) was added to the culture medium to inhibit

cell proliferation at 2 h before the scratch wound was applied.

Each well was scratched across the center using a sterile P-200

pipet tip to create an artificial in vitro wound. Cells in

each group were treated as described earlier. After 12-h incubation

at 37°C, the cells were washed with PBS and stained with 0.5%

crystal violet. Imaging as performed by light microscopy and

analyzed with ImageJ software (version 1.48; National Institutes of

Health, Bethesda, MD, USA).

Animal transient middle cerebral artery

occlusion (tMCAO) model

A total of 40 male SD rats (age, 8-12 weeks; weight,

220-250 g) were selected and purchased from the Experimental Animal

Center of Hainan Medical University 5 days before the experiments.

All procedures performed with animals were approved by the

Institutional Clinical Experiments Committee of the Second

Affiliated Hospital of Hainan Medical University (Haikou, China).

Rats were housed at 21-26°C with a humidity of 65±5%, 0.03%

CO2 and 12 h light/dark cycle with free access to water

and food. They were fasted for 6 h before tMCAO. Briefly, 2.5%

sodium pentobarbital (36 mg/kg; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) was

injected into the abdominal cavity of rats. Next, the common,

internal and external carotid arteries of the neck were exposed by

blunt dissection. A 1.8 cm-long nylon filament (diameter, 0.24-0.28

mm; Biospes Co., Ltd., Chongqing, China) was inserted via a cut of

the internal carotid artery, and the middle cerebral artery was

occluded by inserting the nylon filament (23,24). Rats were kept at 37°C during the

entire surgical procedure. The nylon filament was untied 2 h after

tMCAO. Finally, the rats in the experimental group were treated

with propofol (100 mg/kg; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA), while the

rats without any surgery in the sham group and rats subjected to

tMCAO in control group were only treated with saline (100 mg/kg;

Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) (25,26). A total of 10 animals were used for

each group.

BrdU immunofluorescence

At 2 days after tMCAO challenge, SD rats were

intravenously treated with BrdU (50 mg/kg; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck

KGaA) two times at 12-h intervals. Then, rats were euthanized using

2.5% sodium pentobarbital. Cryostat brain sections (20 µm)

from the frontal to the occipital poles were cut using a

cryomicrotome (HM525 NX; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham,

MA, USA). The sections were then incubated with HCl (2N) at 37°C

for 30 min, and borate buffer was used to neutralize the HCl

through three washes. Next, the sections were blocked with 1% FBS

in 0.3% Triton X-100 at 37°C for 10 min and stained using a BrdU

cell proliferation assay kit (Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.,

Danvers, MA, USA) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Microglia

were labeled with a primary antibody against ionized calcium

binding adaptor molecule 1 (Iba1; cat. no. 019-19741; 1:500

dilution; Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Ltd., Osaka, Japan) at 4°C

overnight. In addition, 702- Rat IgG1 kappa antibody (cat. no.

67-4301-80; 1:500; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) was used as the

control antibody. Subsequently, the cells were stained with an

Alexa488-conjugated secondary antibody (cat. no. S11223; 1:1,000

dilution; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) after the unbound primary

antibody was washed three times using PBS. Finally, cells were

imaged using laser scanning confocal microscopy (TCS SP8 DLS; Leica

Microsystems GmbH). The number of double immune positive microglia

in 10 different fields-of-view was analyzed using ImageJ

software.

ELISA

At 12 h after tMCAO, the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)

of SD rats was extracted following a previously described method

(27). Subsequently, the levels

of interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6 and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) in

the CSF were measured using ELISA kits (cat. nos. EK0393, EK0412

and EK0526; Boster Biological Technology, Ltd., Wuhan, China)

following the manufacturer’s protocol.

Statistical analysis

Experimental values are reported as the mean ±

standard deviation, and the one-way analysis of variance followed

by Student-Newman-Keuls post hoc test was used to evaluate

statistically significant differences between groups. Differences

were considered to be statistically significant when the P-value

was <0.05. Statistical evaluations were performed with the SPSS

version 13 software package (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Propofol inhibits NO and ROS

overexpression induced by LPS in microglia through the A2b

receptor

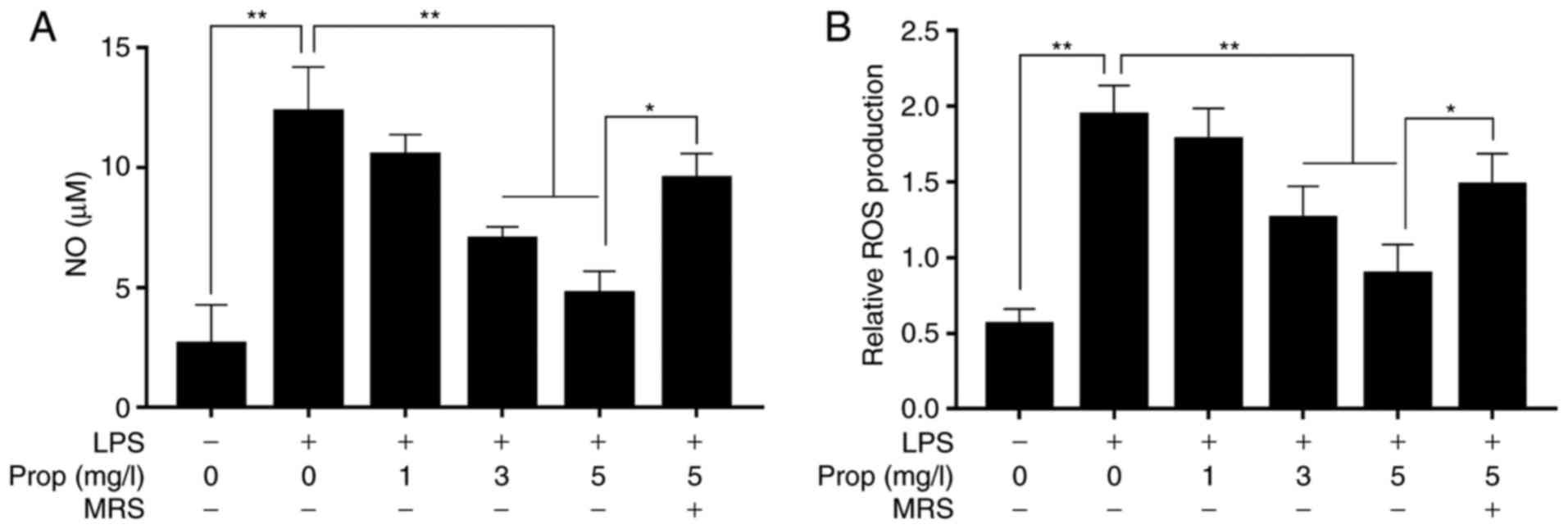

ROS and NO are the major cytotoxic factors secreted

by overactive microglia (Fig. 1).

The present study results revealed that the expression levels of

ROS and NO in microglia were 0.58 and 2.52 µM in untreated

cells (Fig. 2). Following

stimulation with LPS (1 µg/ml), the levels of ROS and NO

increased by 379.3 and 491.6% (both P<0.01), respectively.

However, the ROS and NO levels decreased by 8.3 and 12.2% as

compared with the LPS alone group when LPS-treated microglia were

stimulated with propofol (1 mg/l) (P<0.01). When the

concentration of propofol was increased to 3 mg/l, the ROS and NO

levels in LPS-treated cells decreased by 31.6 and 39.5%,

respectively, and further decreased by 52.3 and 49.8% following

treatment with 5 mg/l propofol (P<0.01). However, the effect of

propofol (5 mg/l) on microglia was inhibited by 100 µM MRS

agar, an A2b receptor antagonist, and the levels of ROS and NO were

increased by 169.5 and 172.4% (P<0.05), respectively, as

compared with those in the LPS and propofol (5 mg/l) group

(Fig. 2A and B).

Propofol inhibits structural alterations

in cytoskeletal protein F-actin in microglia through A2b

receptors

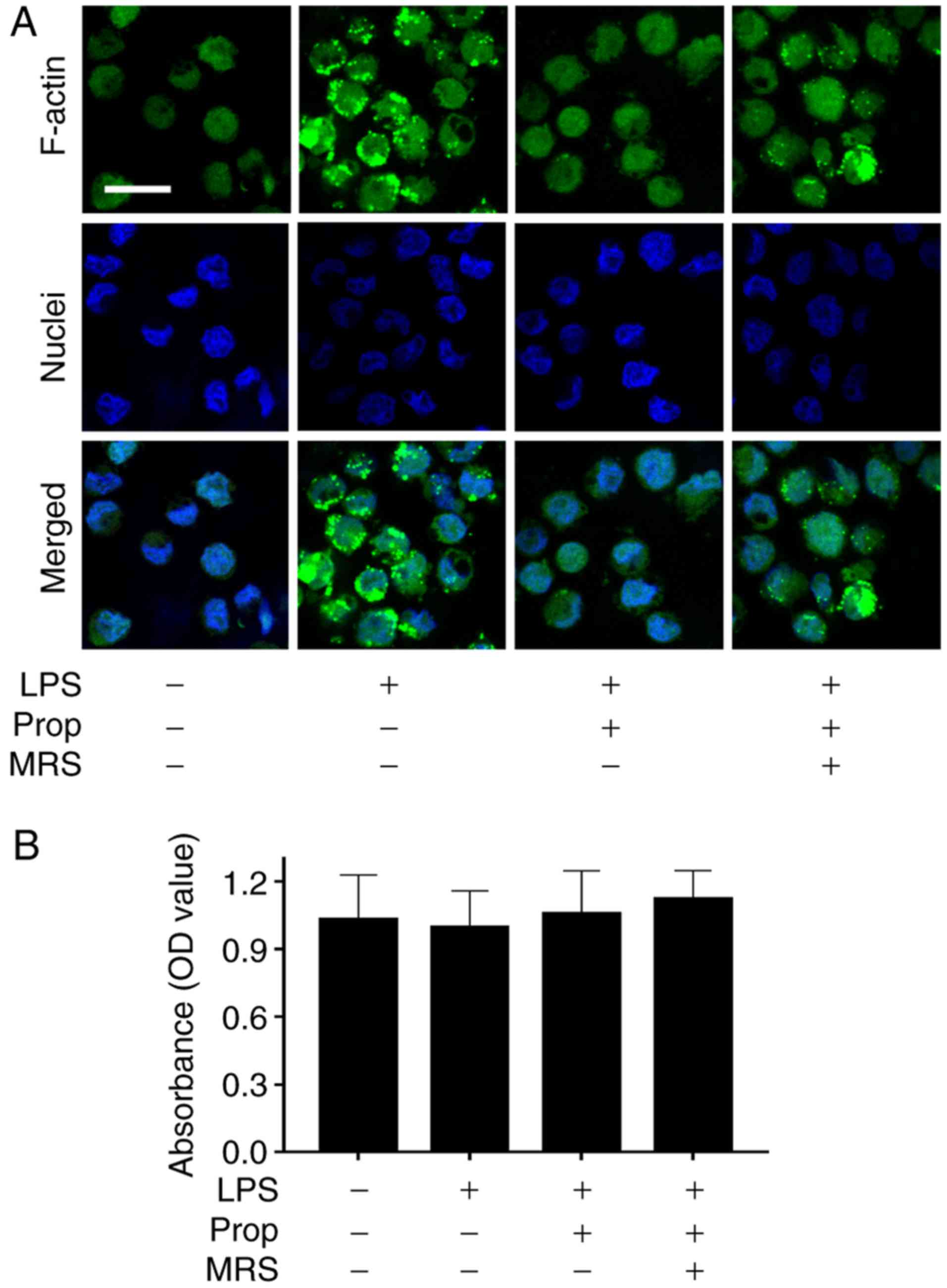

The actin cytoskeleton serves an important role in

the morphological alteration of cells, and structural change in

F-actin is one of the results of microglial activation (Fig. 1) (28). In the present study, the changes

in F-actin were detected by fluorescence staining (Fig. 3A). The results revealed that the

fluorescence intensity of F-actin in microglia was low in untreated

control cells, whereas it significantly increased following the

addition of LPS. The fluorescence intensity in microglia strongly

decreased subsequent to treatment with propofol, which demonstrated

that propofol inhibited the structural alterations in the

cytoskeletal protein in microglia. However, the effect of propofol

on microglia was suppressed by the addition of 100 µM MRS

agar (Fig. 3A). MTT results

demonstrated that microglial survival rates were similar among all

four experimental groups, as the OD value was ~1.0 and there was no

significant difference between any of the groups (Fig. 3B).

Propofol inhibits LPS-induced abnormal

migration of microglia via the A2b receptor

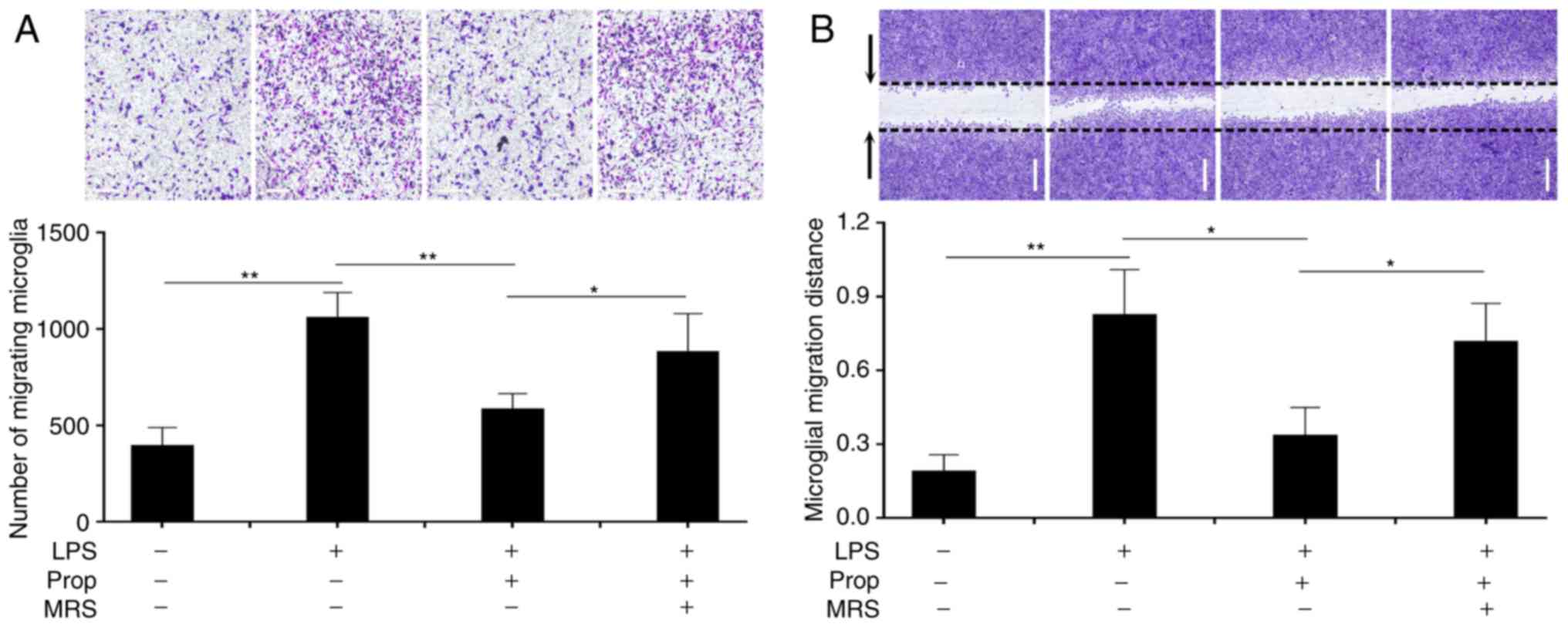

Microglia migration increased abnormally following

cerebral infarction (Figs. 1 and

4) (29). In untreated control cells, the

number of migrating cells was 473 and the migration distance was

0.195 mm (Fig. 4). Subsequent to

treatment with LPS, microglial migration was significantly

increased, as the number of migrating cells and the migration

distance had increased to 236.7 and 412.5% (P<0.01),

respectively. However, microglial migration decreased following

treatment with propofol (5 mg/ml), as the number of migrating cells

and the migration distance markedly decreased by 46.4 and 54.1%

(P<0.01), respectively. These results demonstrated that propofol

inhibited microglial migration following cerebral ischemia. Similar

to the aforementioned results of other experiments, the effect of

propofol was inhibited by MRS agar treatment, as the number of

migrating cells and the migration distance in the MRS agar-treated

group increased to 137.6 and 196.4% (P<0.05), respectively,

compared with that of the LPS and propofol (5 mg/l) group (Fig. 4A and B).

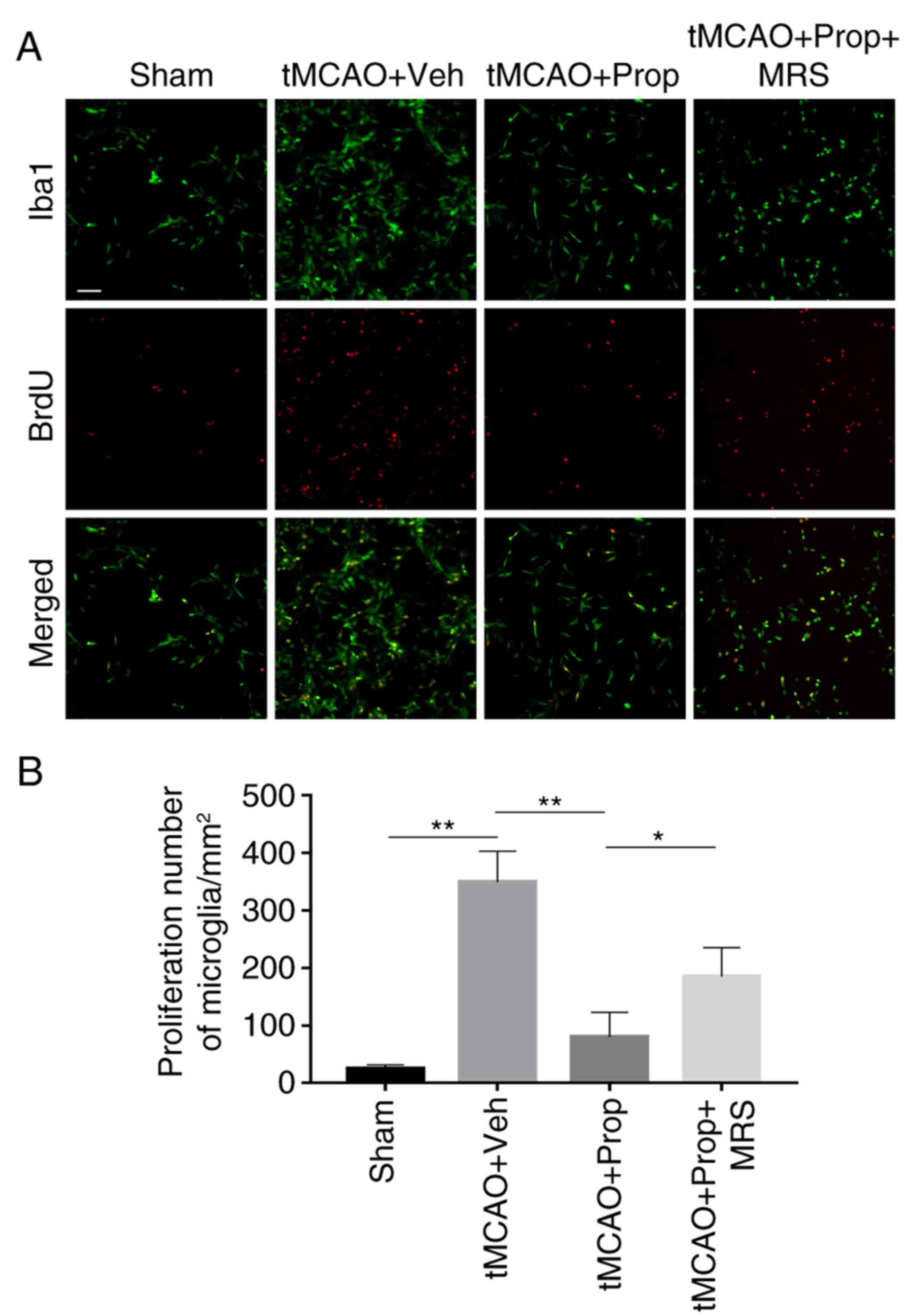

Propofol inhibits abnormal proliferation

of microglia in the tMCAO model through the A2b receptor

Abnormal proliferative potential of microglia is

associated with brain ischemia and reperfusion (30). In order to assess the effect of

propofol on microglial proliferation, brain sections were processed

with double-immunofluorescence with BrdU and an antibody against

Iba1, a microglia-specific marker. In the control group, microglia

exhibited a low proliferative potential, the number of

double-positive cells was 28.6/mm2. Microglial

proliferative potential increased significantly subsequent tMCAO,

and the number of double-positive cells increased to

367.2/mm2 at 3 days following tMCAO (P<0.01). Upon

treatment with propofol (5 mg/l), the number of double-positive

cells in the tMCAO model rats decreased to 92/mm2

(P<0.01). However, the effect of propofol was significantly

inhibited by the addition of MRS agar, as the number of microglia

increased to 196/mm2 in the MRS agar-treated group

(P<0.05) (Fig. 5A and B).

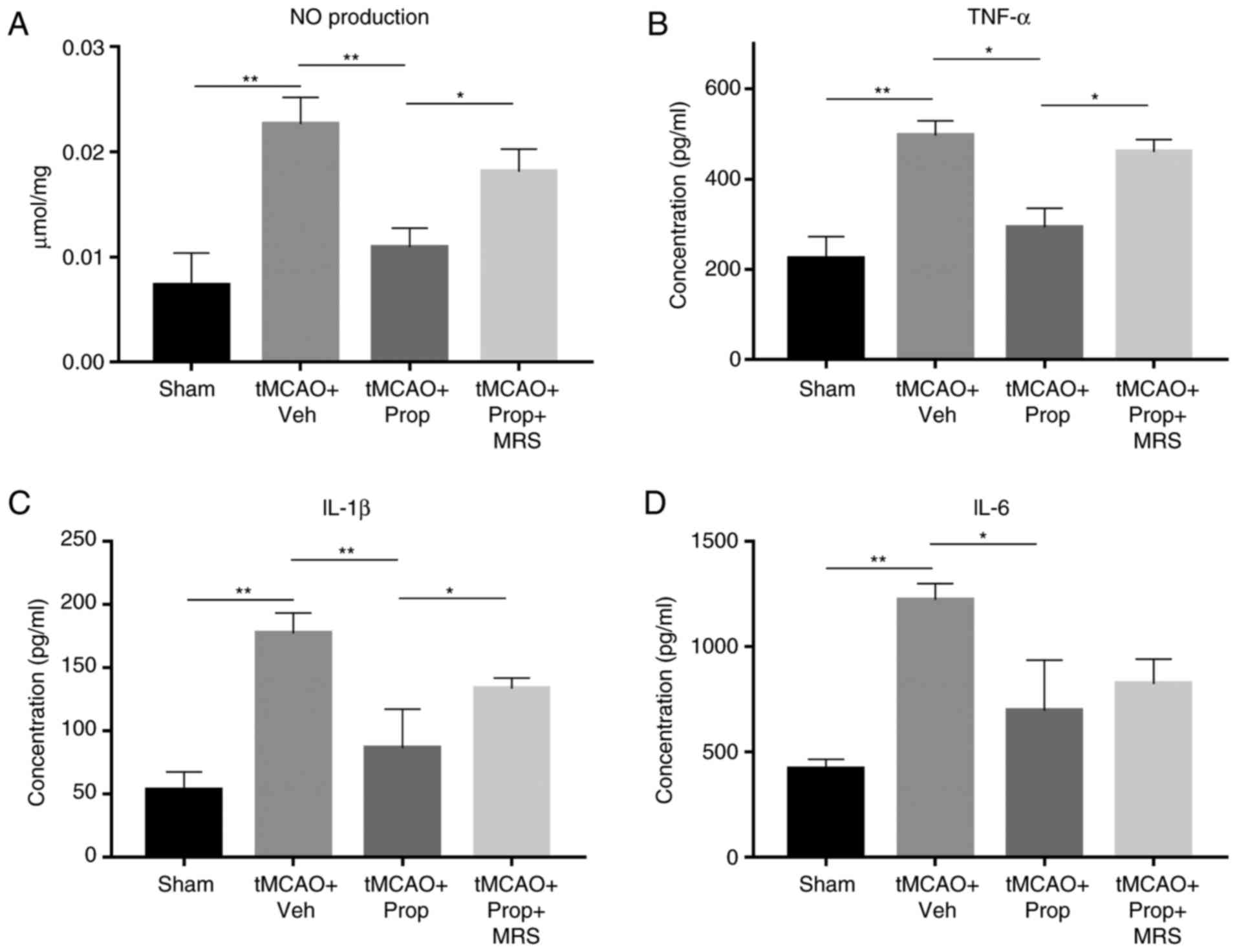

Propofol inhibits the overexpression of

microglial inflammatory factors in the tMCAO model via the A2b

receptor

Following cerebral ischemia and reperfusion,

microglia and other associated inflammatory cells release a large

quantity of pro-inflammatory and cytotoxic factors, including IL-6,

IL-1β, TNF-α and NO. In the control group, the inflammatory

response remained at a low level, and the measured levels of IL-6,

IL-1β and TNF-α in the CSF were 461, 53 and 226 pg/ml,

respectively, while the level of NO was 0.0088 µmol/mg. The

inflammatory response was significantly enhanced at 3 days after

tMCAO challenge, and the levels of IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α and NO

increased to 294.1, 312.4, 255.7 and 283.4%, respectively (all

P<0.01), compared with those observed in the control group.

Following treatment with propofol (5 mg/ml), the inflammatory

response decreased, and the production of IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α and NO

decreased by 61 (P<0.05), 49 (P<0.01), 63 (P<0.05) and 47%

(P<0.01), respectively. However, the effect of propofol on

microglia and other inflammatory cells was significantly inhibited

by MRS agar treatment, as the production of IL-1β, TNF-α and NO in

the CSF increased by 1.33-, 1.41- and 1.39-fold (P<0.05),

respectively, when compared with the LPS and propofol-treated alone

group. Notably, the expression of IL-6 was less affected by MRS

agar treatment, and the IL-6 production only increased to 1.15-fold

that of the propofol-treated group in the MRS-treated group, with

no significant difference observed (Fig. 6).

Discussion

Excessive activation of microglia is considered to

be the main cause of cerebral infarction injury in the central

nervous system (31-32). Secreted cytotoxic and inflammatory

cytokines can lead to neuritis, immune response and damage of the

nervous system, and may be the main pathological basis of several

neurodegenerative diseases (33).

A number of previous studies had found that propofol has

neuroprotective effects in animal models (34-36). However, there is a lack of studies

on the mechanism of action of propofol regarding its

neuroprotective role (37). In

the present study, the effects of propofol on suppressing

inflammation were examined, and it was attempted to identify a

suitable dose for clinical use.

LPS can induce microglia to release abundant

quantities of NO and ROS. These factors are major cytotoxic

substances released following ischemic stroke (38,39). Comparing microglia from each

experimental group, the current study observed that propofol was

able to inhibit the overexpression of NO and ROS, and these results

are in agreement with recent evidence (40). In addition, the experimental

results of the present study revealed that there was a negative

correlation between the expression of cytotoxic factors and the

propofol dose within a certain concentration range. Simultaneously,

the effect of propofol on microglial activityand survival was also

investigated by MTT assay, and the results indicated that propofol

treatment has no significant effect on microglial activity. These

findings are important for future clinical applications of

propofol.

Following ischemic stroke, activated microglia

migrates rapidly to the site of injury and mediates the

inflammatory reaction (28).

Comparing the number of migrated cells in the Trans well experiment

and scratch injury assays conducted in the present study, it was

observed that propofol inhibited the abnormal proliferation of

overactive microglia. These in vitro experimental results

preliminarily demonstrate that propofol is able to inhibit the

aberrant migration of overactive microglia and the overexpression

of cytotoxic factors.

It is known that cytoskeletal proteins serve an

important role in maintaining cellular morphology and function

(41). In the present study,

fluorescence staining of microglial F-actin demonstrated that

propofol treatment inhibited the structural alterations induced by

LPS in the microglial cytoskeleton induced.

A tMCAO rat model was also employed in the current

study to assess microglial proliferation and inflammatory factor

secretion in vivo. It was observed that propofol inhibited

the proliferation and activation of microglia. In addition, the

levels of IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α and NO were evidently low in the

propofol-treated group, which indicated that propofol attenuated

inflammation in tMACO. Although it remains uncertain whether all

these inflammatory factors are secreted only by microglia, it is

likely that propofol inhibits the overall levels of inflammatory

factors in the brain subsequent to ischemic stroke.

In the aforementioned experiments, an MRS

agartreatment group was used to determine the mechanism of action

of propofol on cerebral inflammation. The results suggested that

MRS agar, an A2b receptor antagonist, effectively blocked nearly

all the effects of propofol on microglia. This supports the

hypothesis that the A2b receptor serves a significant role in the

inflammation-attenuating effects of propofol. However, blocking the

A2b receptor did not significantly affect the level of IL-6,

suggesting that propofol may also fulfill its anti-inflammatory

function via another route.

In conclusion, propofol was demonstrated to inhibit

excessive microglial activation, abnormal proliferation and

migration, as well as the release of cytotoxic and inflammatory

factors, and its effects were likely mediated by the A2b receptor.

Therefore, the present study determined a feasible drug and an

appropriate clinical dosage for the purpose of reducing

inflammation and improving the prognosis in cerebral infarction. In

addition, A2b receptor may be not the only receptor through which

propofol acts on microglia, and other pathways remain to be

explored (42). Determining the

ideal reaction time, propofol dosage and possible side effects will

be the direction of future research.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was supported by the 2016 Cultivation

Fund of Hainan Medical University (grant no. HY2016-07) and the

Industry Research Project of Hainan Health and Family Planning

Commission (grant no. 1601032054A2001).

Availability of data and material

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current

study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable

request.

Authors’ contributions

HY took part in all experiments and was the major

contributor in writing the manuscript. XW analyzed and interpreted

the data regarding cell experiments. FK and ZC established the

tMCAO model and conducted other experiments in vivo. YM

analyzed and interpreted data regarding experiments in vivo.

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

All procedures involving animals were reviewed and

approved by the Institutional Clinical Experiments Committee and

Institutional Review Board of the Hainan Medical University

(Haikou, China).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Liu J, Zhao D, Wang W, Sun JY, Li Y and

Jia YN: Trends regarding the incidence of recurrent stroke events

in Beijing. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 28:437–440. 2007.In

Chinese. PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Labeyrie C, Cauquil C, Sarov M, Adams D

and Denier C: Cerebral infarction following subcutaneous

immunoglobulin therapy for chronic inflammatory demyelinating

polyradiculo-neuropathy. Muscle Nerve. 54:166–167. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Numata K, Suzuki M, Mashiko R and Tokuda

Y: Lethal bilateral cerebral infarction caused by moyamoya disease.

OJM. 109:5012016.

|

|

4

|

Zhan R, Xu K, Pan J, Xu Q, Xu S and Shen

J: Long noncoding RNA MEG3 mediated angiogenesis after cerebral

infarction through regulating p53/X4 axis. Biochem Biophys Res

Commun. 490:700–706. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Kwon SK, Ahn M, Song HJ, Kang SK, Jung SB,

Harsha N, Jee S, Moon JY, Suh KS, Lee SD, et al: Nafamostat

mesilate attenuates transient focal ischemia/reperfusion-induced

brain injury via the inhibition of endoplasmic reticulum stress.

Brain Res. 1627:12–20. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Yang S, Gao L, Lu F, Wang B, Gao F, Zhu G,

Cai Z, Lai J and Yang Q: Transcription factor myocyte enhancer

factor 2D regulates interleukin-10 production in microglia to

protect neuronal cells from inflammation-induced death. J

Neuroinflammation. 12:332015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Brown A: Understanding the MIND phenotype:

Macrophage/ microglia inflammation in neurocognitive disorders

related to human immunodeficiency virus infection. Clin Transl Med.

4:72015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Pessach I and Paret G: PICU propofol use,

where do we go from here? Pediatr Crit Care Med. 17:273–275. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Shi SS, Yang WZ, Chen Y, Chen JP and Tu

XK: Profol reduces inflammatory reaction and ischemic brain damage

in cerebral ischemia in rats. Neurochem Res. 39:793–799. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Woldegerima N, Rosenblatt K and Mintz CD:

Neurotoxic properties of propofol sedation following traumatic

brain injury. Crit Care Med. 44:455–456. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Liu J, Gao XF, Ni W and Li JB: Effects of

propofol on P2X7 receptors and the secretion of tumor necrosis

factor-α in cultured astrocytes. Clin Exp Med. 12:31–37. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Perígolo-Vicente R, Ritt K,

Gonçalves-de-Albuquerque CF, Castro-Faria-Neto HC, Paes-de-Carvalho

R and Giestal-de-Araujo E: IL-6, A1 and A2aR: A crosstalk that

modulates BDNF and induces neuroprotection. Biochem Biophys Res

Commun. 449:477–482. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Zywert A, Szkudelska K and Szkudelski T:

Effects of adenosine A1 receptor antagonism on insulin

secretion from rat pancreatic islets. Physiol Res. 60:905–911.

2011.

|

|

14

|

Ohnishi M, Urasaki T, Ochiai H, Matsuoka

K, Takeo S, Harada T, Ohsugi Y and Inoue A: Selective enhancement

of wnt4 expression by cyclic AMP-associated cooperation between rat

central astrocytes and microglia. Biochem Biophys Res Commun.

467:367–372. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Kim JB, Yu YM, Kim SW and Lee JK:

Anti-inflammatory mechanism is involved in ethyl pyruvate-mediated

efficacious neuroprotection in the postischemic brain. Brain Res.

1060:188–192. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Wang AL, Yu AC, He QH, Zhu X and Tso MO:

AGEs mediated expression and secretion of TNFα in rat retinal

microglia. Exp Eye Res. 84:905–913. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Guo H, Hu LM, Wang SX, Wang YL, Shi F, Li

H, Liu Y, Kang LY and Gao XM: Neuroprotective effects of

scutellarin against hypoxic-ischemic-induced cerebral injury via

augmentation of antioxidant defense capacity. Chin J Physiol.

54:399–405. 2011.

|

|

18

|

Hands S, Sajjad MU, Newton MJ and

Wyttenbach A: In vitro and in vivo aggregation of a fragment of

huntingtin protein directly causes free radical production. J Biol

Chem. 286:44512–44520. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Lee JK, Chung J, McAlpine FE and Tansey

MG: Regulator of G-protein signaling-10 negatively regulates NF-κB

in microglia and neuroprotects dopaminergic neurons in

hemiparkinsonian rats. J Neurosci. 31:11879–11888. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Shen K, Tolbert CE, Guilluy C, Swaminathan

VS, Berginski ME, Burridge K, Superfine R and Campbell SL: The

vinculin C-terminal hairpin mediates F-actin bundle formation,

focal adhesion, and cell mechanical properties. J Biol Chem.

286:45103–45115. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Gorbatyuk V, Nguyen K, Podolnikova NP,

Deshmukh L, Lin X, Ugarova TP and Vinogradova O: Skelemin

association with αIIbβ3 integrin: A

structural mode. Biochemistry. 53:6766–6775. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Li X, Liu Y and Haas TA: Skelemin in

integrin αIIbβ3 mediated cell spreading.

Biochemistry. 52:681–689. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Zuhayra M, Zhao Y, von Forstner C, Henze

E, Gohlke P, Culman J and Lützen U: Activation of cerebral

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors γ (PPARγ) reduces

neuronal damage in the substantia nigra after transient focal

cerebral ischaemia in the rat. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol.

37:738–752. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Cao LJ, Wang J, Hao PP, Sun CL and Chen

YG: Effects of ulinastatin, a urinary trypsin inhibitor, on

synaptic plasticity and spatial memory in a rat model of cerebral

ischemia/reperfusion injury. Chin J Physiol. 54:435–442. 2011.

|

|

25

|

Stekiel TA, Conteny SJ, Roman RJ, Weber

CA, Stadnicka A, Bosnjak ZJ, Greene AS and Moreno C:

Pharmacogenomic strain differences in cardiovascular sensitivity to

propofol. Anesthesiology. 115:1192–1200. 2011.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Tanaka K, Tsutsumi YM, Kinoshita M, Kakuta

N, Hirose K, Kimura M and Oshita S: Differential effects of

propofol and isoflurane on glucose utilization and insulin

secretion. Life Sci. 88:96–103. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Mariappan TT, Kurawattimath V, Gautam SS,

Kulkarni CP, Kallem R, Taskar KS, Marathe PH and Mandlekar S:

Estimation of the unbound brain concentration of P-glycoprotein

substrates or nonsubstrates by a serial cerebrospinal fluid

sampling technique in rats. Mol Pharm. 11:477–485. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Wessler S, Gimona M and Rieder G:

Regulation of the actin cytoskeleton in Helicobacter pylori-induced

migration and invasive growth of gastric epithelial cells. Cell

Commun Signal. 9:272011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Davalos D, Grutzendler J, Yang G, Kim JV,

Zuo Y, Jung S, Littman DR, Dustin ML and Gan WB: ATP mediates rapid

microglial response to local brain injury in vivo. Nat Neurosci.

8:752–758. 2005. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Campanella M, Sciorati C, Tarozzo G and

Beltramo M: Flow cytometric analysis of inflammatory cells in

ischemic rat brain. Stroke. 33:586–592. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Jin YL, Luo HL, Liu L, Cheng CF and Ho LC:

Inhibitory effects of different concentrations of curcumin on

excessive activation of microglia cultured in vitro. J Clin Rehabil

Tissue Eng Res. 15:6951–6955. 2011.

|

|

32

|

Stertz L, Magalhães PV and Kapczinski F:

Is bipolar disorder an inflammatory condition? The relevance of

microglia activation. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 26:19–26. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Kokubu Y, Yamaguchi T and Kawabata K: In

vitro model of cerebral ischemia by using brain microvascular

endothelial cells derived from human induced pluripotent stem

cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 486:577–583. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Zhou R, Yang Z, Tang X, Tan Y, Wu X and

Liu F: Propofol protects against focal cerebral ischemia via

inhibition of microglia-mediated proinflammatory cytokines in a rat

model of experimental stroke. Plos One. 8:e827292013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Li J, Han B, Ma X and Qi S: The effects of

propofol on hippocampal caspase-3 and Bcl-2 expression following

forebrain ischemia-reperfusion in rats. Brain Res. 1356:11–23.

2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Harman F, Hasturk AE, Yaman M, Arca T,

Kilinc K, Sargon MF and Kaptanoglu E: Neuroprotective effects of

propofol, thiopental, etomidate, and midazolam in fetal rat brain

in ischemia-reperfusion model. Childs Nerv Syst. 28:1055–1062.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Pfeilschifter W, Czech-Zechmeister B,

Sujak M, Mirceska A, Koch A, Rami A, Steinmetz H, Foerch C, Huwiler

A and Pfeilschifter J: Activation of sphingosine kinase 2 is an

endogenous protective mechanism in cerebral ischemia. Biochem

Biophys Res Commun. 413:212–217. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Shuhua X, Ziyou L, Ling Y, Fei W and Sun

G: A role of fluofide on free radical generation and oxidative

stress in BV-2 microglia cells. Mediators Inflamm. 2012:1029542012.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Brites D and Femandes A: Neuroinflammation

and depression: Microglia activation, extracellular mierovesicles

and microRNA dysregulation. Front Cell Neurosci. 9:4762015.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Zheng X, Huang H, Liu J, Li M, Liu M and

Luo T: Propofol attenuates inflammatory response in LPS-activated

microglia by regulating the miR-155/SOCS1 pathway. Inflammation.

41:11–19. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Hagiwara S, Iwaska H, Hasegawa A, Hidaka

S, Uno A, Kaori U, Uchida T and Noguchi T: Continuous

hemodiafiltration therapy ameliorates LPS-induced systemic

inflammation in a rat model. J Surg Res. 171:791–796. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Tang J, Chen X, Tu W, Guo Y, Zhao Z, Xue

Q, Lin C, Xiao J, Sun X, Tao T, et al: Propofol inhibits the

activation of p38 through up-regulating the expression of annexin

A1 to exert its anti-inflammation effect. PLoS One. 6:e278902011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|