Introduction

A functionally and structurally intact vascular

endothelium is essential for maintaining the normal function and

activity of the cardiovascular system. Continuous stimulation

(e.g., stress, inflammation and hypoxia) can cause vascular

endothelial activation and injury, eventually leading to

atherosclerosis (1,2). Angiogenesis, mainly manifested as

endothelial cell (EC) proliferation, migration and tube formation,

is an essential pathological process of atherosclerosis (3). Understanding the regulatory

mechanisms of angiogenesis during endothelial activation and injury

is crucial for controlling the progression of atherosclerosis.

Exosomes, with a size of 50 to 150 nm, are produced

by most cell types and contain a wide range of functional proteins,

lipids, messenger RNAs (mRNAs) and microRNAs (miRNAs or miRs)

(4). Increasing evidence has

indicated that the physiological functions of EC can be regulated

by exosomes shed from various types of cells (5-9).

In particular, ECs secrete functional exosomes, which can in turn

affect the physiological behavior of recipient ECs by delivering

miRNAs or proteins (10,11). In spite of extensive studies, the

effects and mechanisms underlying the communication between

vascular ECs during exosome-mediated angiogenesis remain to be

fully elucidated. As one of the key pathogenetic factors of

angiogenesis during atherosclerosis, oxidative stress can induce

angiogenesis via vascular endothelial growth

factor-dependent/independent signaling pathways (12). However, the role and mechanisms of

exosomes secreted by oxidative stress-stimulated ECs in

angiogenesis remain unclear.

miRNAs are a class of small non-coding RNAs that

post-transcriptionally suppress gene expression by binding to the

3′ untranslated region (3′UTR) of target mRNAs. Several miRNAs have

been shown to regulate vascular endothelial function and

angiogenesis (13), and miR-92a

is most closely related to these processes (14-19). The overexpression of miR-92a in

ECs has been shown to block angiogenesis by targeting several

pro-angiogenic proteins (14). In

the present study, through high-throughput screening, it was found

that miR-92a-3p was markedly downregulated and was the most

abundant miRNA differentially expressed in ECs treated with

oxidative stress-stimulated EC-derived exosomes. It was also

demonstrated that exosomes shed from oxidative stress-stimulated

ECs enhanced EC proliferation, migration and angiogenesis by

decreasing miR-92a-3p expression in target ECs. Moreover, it was

confirmed that tissue factor (TF) was a novel target gene of

miR-92a-3p, which may mediate the regulatory role of miR-92a-3p in

angiogenesis.

Materials and methods

Cells and cell culture

Human umbilical vein ECs (HUVECs) and 293 cells were

purchased from the Shanghai Institutes for Biological Sciences

(CAS). HUVECs were cultured in endothelial cell medium (ECM)

supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% endothelial cell

growth supplement (ECGS), penicillin (100 U/ml) and streptomycin

(100 mg/ml) (Sciencell, Inc.). When HUVEC confluency reached

approximately 70-80%, FBS in ECM was replaced by 5% exosome-free

FBS (System Biosciences) and HUVECs were stimulated with or without

100 µM H2O2 for 24 h to produce

exosomes. HUVECs incubated with exosomes were all cultured in basal

medium (without FBS). 293 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's

modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) containing 10% FBS, penicillin (100

U/ml) and streptomycin (100 µg/ml). All the cells were

cultured in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C (Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.).

miRNA transfection

HUVECs at 70-80% confluency were transfected with

miR-92a-3p inhibitor (66.7 nM), miR-92a-3p mimic (40.0 nM), a

negative control (NC) inhibitor or NC mimic (Suzhou Genepharma Co.,

Ltd.), respectively, using Lipofectamine 2000 (2.7 µg/ml for

inhibitor, 1.3 µg/ml for mimic) (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.). The sequences of miR-92a-3p/NC mimic or

inhibitor were as follows: miR-92a-3p inhibitor, 5′-ACA GGC CGG GAC

AAG UGC AAU A-3′; miR-92a-3p mimic, 5′-UAU UGC ACU UGU CCC GGC CUG

U-3′ and 5′-AGG CCG GGA CAA GUG CAA UAU U-3′; NC inhibitor, 5′-CAG

UAC UUU UGU GUA GUA CAA-3′; NC mimic, 5′-UUC UCC GAA CGU GUC ACG

UTT-3′ and 5′-ACG UGA CAC GUU CGG AGA ATT-3′. Following 24 or 48 h

of transfection, the cells were harvested or further treated with

exosomes according to the different experimental purposes.

Exosome isolation

Endothelial exosomes in the conditioned medium were

isolated by differential centrifugation, as previously described

(20). The medium was centrifuged

at 300 × g for 10 min, 2,000 × g for 10 min and 10,000 × g for 30

min at 4°C. The supernatant was then filtered through a

0.22-µm filter (EMD Millipore) to remove cellular debris,

followed by ultracentrifugation at 100,000 × g and 4°C for 70 min

(WX+ Ultra series; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The exosome

pellets were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), followed

by a second ultracentrifugation at 100,000 × g and 4°C for 70 min,

after which the exosomes were resuspended in PBS and stored at

−80°C.

Transmission electron microscopy

Exosome morphology was observed using a transmission

electron microscope (TEM). A total of 20 µl of samples were

dropped onto a carbon-coated grid, which was then baked at 60°C for

5 min using a polymerizer (ZB-J0010; Beijing Zhongxing Bairui

Technology Co., Ltd.). The excess liquid was absorbed using filter

paper. The grid was subsequently stained with 2% tungstophosphoric

acid for 5 min. Following 2 washes with distilled water, the grid

was baked again at 60°C and visualized using a TEM at 80 kV

(JEM-1400; Jeol, Ltd.).

Nanoparticle tracking analysis

The particle size of the exosomes was analyzed by

nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) using ZetaView PMX110

(Particle Metrix GmbH) in the size mode. Exosome samples were

diluted to the working range

(106-109particles/ml) of the detecting system

with PBS. The video of the Brownian motion of particles was

captured at 11 positions and the particle size was measured using

ZetaView 8.02.28 software.

Exosome labeling

Exosomes were labeled with the red fluorescent dye,

PKH26, according to manufacturer′s instructions with minor

modifications (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) (20). A total of 2 µg of exosomes

were rapidly mixed with 1 ml of PKH26 solution (PKH26 dye: Diluent

C, 1:50 dilution). Following 5 min of incubation at 37°C, 5 ml of

whole ECM medium containing 5% exosome-free FBS were added to

terminate the labeling reaction. The labeled exosomes were washed

with PBS and centrifuged at 100,000 × g and 4°C for 1 h. Exosome

pellets were resuspended in 200 µl of PBS. Subsequently, the

labeled exosomes were added to HUVECs and incubated for 12 h in a

5% CO2 incubator at 37°C (Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.). Following incubation, the HUVECs were washed twice and fixed

with 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 15 min. The cells

were washed 3 times and treated with 0.2% Triton X-100 at 37°C for

15 min. Following 2 more washes, the cells were stained with 10

µg/ml of 4,6 diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) for 5 min and

then imaged under a confocal laser scanning microscope (Leica TCS

SP5, Leica Microsystems GmbH).

Small RNA sequencing analysis

Following 24 h of incubation with exosomes, HUVECs

were collected and total RNA were extracted using the miRNeasy Mini

kit (Qiagen, Inc.). NEBNext®Multiplex Small RNA Library

Prep Set for Illumina® (New England Biolabs, Inc.) was

used to generate the sequencing library according to the

manufacturer′s instructions. Briefly, NEB 3′ SR adaptors were

ligated to the 3′ end of small RNA and SR RT Primer hybridized to

the excessive 3′ SR adaptor. The 5′ adapters were then ligated to

the 5′ ends of small RNA. M-MuLV Reverse Transcriptase (RNase

H-) was used to synthesize the first-strand cDNA.

LongAmp Taq 2X Master Mix, SR Primer for illumina and index (X)

primer were used for PCR amplification. The PCR products

corresponding to 140-160 bp were enriched to generate the cDNA

library. Library quality was assessed on an Agilent 2200 system

with DNA High Sensitivity Chips. The clustering of index-coded

samples was carried out on a cBot Cluster Generation System using

the TruSeq SR Cluster kit v3-cBot-HS (Illumina, Inc.) following the

manufacturer′s instructions. The sequencing (for 50-base read

length) of cDNA library was performed on an Illumina Hiseq 2500.

The clean data were obtained by trimming adaptor sequences and

removing low-quality reads. The small RNA tags were aligned using

Bowtie and mapped to the human genome reference (version: GRCh38

NCBI). miRBase20.0 was used as reference to obtain known miRNAs.

Software mirdeep2 and miREvo were integrated to identify novel

miRNAs. Differentially expressed miRNAs were analyzed using the

DESeq R package (1.8.3). miRNAs with a P-value <0.05 were

considered to exhibit a significant differential expression. miRNAs

with similar expression pattern were clustered and displayed as a

heatmap.

Messenger RNA (mRNA) sequencing

analysis

HUVECs were transfected with miR-92a-3p inhibitor

for 48 h and then total RNA were isolated using the miRNeasy Mini

kit (Qiagen, Inc.). The NEBNext® Ultra™ Directional RNA

Library Prep kit for Illumina® (New England Biolabs,

Inc.) was used to generate the sequencing library according to the

manufacturer′s instructions. Briefly, mRNA was fragmented into

150-200 bp using divalent cations at 94°C for 8 min. The cleaved

mRNA fragments were reverse-transcribed into first-strand cDNA, and

the fragments were end repaired and ligated with indexed adapters.

Target bands were harvested through AMPure XP Beads (Beckman

Coulter, Inc.). The products were purified and enriched by PCR to

generate the final cDNA libraries and quantified by Agilent 2200.

The tagged cDNA libraries were pooled in equal ratio and used for

150 bp paired-end sequencing in a single lane of the Illumina

HiSeqXTen. To obtain clean data, raw reads were processed by

removing the adaptor sequences, reads with >5% ambiguous bases

and low-quality reads containing >20% of bases with qualities of

<20. The sequencing data were aligned to human genome (version:

GRCh38 NCBI) using the hisat2 algorithm. HTseq was used to count

gene and the reads per kilobase per million mapped reads (RPKM)

method was used to determine gene expression. Differentially

expressed genes were analyzed using the DESeq2 algorithm with a

fold change of >1.5 or <0.5, a P-value <0.05 and a false

discovery rate of <0.05.

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR

(RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was isolated from the HUVECs or exosomes

using the miRNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen, Inc.). miRNA-specific

stem-loop primers and the TaqMan MicroRNA Reverse Transcription kit

(Applied Biosystems, Inc.) were used for the amplification of

mature miRNAs. The expression level of mature miR-92a-3p was

normalized to the expression levels of RNU6B in HUVECs and

synthetic C. elegans miR-39 (cel-miR-39) (10 fmol/sample)

(Qiagen, Inc.) in exosomes, respectively. The ImProm-II™

Transcription System and GoTaq 2-Step RT-qPCR System (Promega

Corporation) were used for TF amplification. The TF expression

level was normalized to the expression of GAPDH. The sequences of

the primers were as follows: TF forward, 5′-GCC AGG AGA AAG GGG

AAT-3′ and reverse, 5′-CAG TGC AAT ATA GCA TTT GCA GTA GC-3′; GAPDH

forward, 5′-GAG TCA ACG GAT TTG GTC GT-3′ and reverse, 5′-GAC AAG

CTT CCC GTT CTC AG-3′. The amplifications were performed as

previously described (21). For

the quantification of primary miR-92a, the levels of pri-miR-92a-1

and pri-miR-92a-2 were measured using the High Capacity cDNA

Reverse Transcription kit (Applied Biosystems, Inc.), TaqMan

Pri-miRNA assays (pri-miR-92a-1 assay ID: Hs03302603_pri,

pri-miR-92a-2 assay ID: Hs03295977_pri) and TaqMan Gene Expression

Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Inc.) according to the

manufacturer′s instructions. The amplification conditions were

pre-incubation at 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C

for 15 sec and 60°C for 1 min. The results were normalized to the

expression of GAPDH (TaqMan assay ID: Hs02758991_g1). qPCR was

performed on an Applied Biosystems system (ViiA7) and all data are

expressed as 2−ΔΔCq(22).

Western blot analysis

HUVECs or exosome samples were lysed using a RIPA

buffer (Solarbio, Inc.) and then centri-fuged at 12,000 × g and 4°C

for 15 min. The supernatant was collected and the protein

concentration was measured using the bicinchoninic acid (BCA)

protein assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) according to the

manufacturer′s instructions. A total of 10-20 µg of proteins

were separated on a 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel and

electrophoretically transferred to PVDF membranes (EMD Millipore).

The membranes were incubated with one of the following primary

antibodies: TF (1:1,000; cat. no. 55147S, Cell Signaling

Technology, Inc.), GAPDH (1:2,000; cat. no. sc-32233; Santa Cruz

Biotechnology, Inc.), Flotillin-1 (1:200; cat. no. sc25506; Santa

Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), GM130 (1:250; cat. no. 610822, BD

Biosciences), Lamin A/C (1:500; cat. no. sc-7292; Santa Cruz

Biotechnology, Inc.) and Tom20 (1:500; cat. no. sc-17764, Santa

Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) at 4°C overnight and were then incubated

with HRP-conjugated goat-anti-rabbit (1:2,000; cat. no. sc-2004,

Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) or mouse (1:4,000 for GAPDH or

1:2,000 for the rest, cat. no. sc-2005; Santa Cruz Biotechnology,

Inc.) IgG secondary antibodies at room temperature for 2 h. The

membranes were visualized using an enhanced-chemiluminescence

system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The bands were quantified

using Image J 1.52a software. The expression level of TF was

normalized to that of GAPDH.

EdU incorporation assay

Proliferating HUVECs were identified using the

Click-iT Plus EdU Imaging kit (Life tech-nologies; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.). Following co-culture with exosomes or

transfection with miRNA inhibitor, the HUVECs were incubated with

10 µM EdU for 16 h, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15

min at room temperature and washed with PBS containing 3% bovine

serum albumin (BSA). The cells were then treated according to the

following steps: 20 min in 0.5% Triton X-100, 30 min in the

Click-iT Plus reaction cocktail, and 30 min in 5 µg/ml of

Hoechst 33342 at room temperature. Cell images were captured using

an Olympus IX70 microscope (Olympus Corporation). The ratio of

EdU-positive cells to total cells was analyzed by counting

approximately 1,000 cells in several randomly selected fields.

Scratch wound migration assay

The assessment of HUVEC migration was performed as

previously described (23). A

confluent layer of HUVECs in 24-well plates was scratched with a

sterile 10-µl tip and the detached cells were removed by

washing with PBS. The adherent cells were then incubated with 5

µg/ml exosomes for 20 h before cell migration was captured

using a Leica DM IL LED microscope (Leica Microsystems GmbH) and

quantified by measuring the size of recovered area using ImageJ

1.52a software.

Tube formation assay

Matrigel Matrix Growth Factor Reduced (BD

Biosciences) (300 µl/well) was coated on 24-well plates and

incubated at 37°C for 30 min. Approximately 8×104

HUVECs/well were then seeded onto the gel and cultured in FBS-free

ECM for 20 h to allow tube formation. Tube formation was observed

using a Leica DM IL LED microscope (Leica Microsystems GmbH). The

averages of the total number of branching points and total number

of loops in 4 representative fields were analyzed using ImageJ

1.52a software.

In vivo Matrigel plug assay

A total of 8 female, 8-week-old, BALB/c nude mice

(Charles River Laboratories, Inc.) were used in this study. All the

mice were housed in specific pathogen-free conditions under a

controlled temperature (23±3°C), humidity (60±15%) and 12 h

dark/light cycle, with sterile rodent chow and water provided ad

libitum. The mice were kept in specific pathogen-free grade

filter-top cages and infectious diseases were not detected.

Following transfection with miR-92a-3p inhibitor or NC inhibitor

for 48 h, the HUVECs were mixed with Matrigel Matrix High

Concentration (BD Biosciences) at ratio of 1:1 (V:V). Subsequently,

1 ml of mixture containing 1×107 HUVECs was

subcutaneously injected into the dorsal surface of each nude mouse

(n=4/group) using a 25-gauge needle. After 2 weeks, the mice were

euthanized by an intraperitoneal injection of an overdose of

pentobarbital (120 mg/kg). The Matrigel plugs were harvested,

transferred to ice-cold PBS and embedded in OCT compound. Serial

5-µm-thick sections were cut and stained with anti-CD31

antibody (1:100; cat. no. ab28364, Abcam) at 4°C overnight. The

sections were observed under a Jenoptik fluorescence microscope. A

representative surface of blood vessels was analyzed by analyzing

the CD31-positive region (24).

The animal experimental protocol was approved by Peking University

People′s Hospital Ethics Committee (approval no. 2016PHC072).

Luciferase reporter assay

Luciferase reporter assay was performed as

previously described (21). The

sequence (1,284 bp) of TF 3′UTR containing the miR-92a-3p binding

site was synthesized and cloned into a Firefly luciferase reporter

plasmid pMIR-REPORT™ (Ambion; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). To

construct the mutant plasmid, the predicted target nucleotides of

miR-92a-3p in TF 3′UTR were changed to opposite bases. 293 cells

were co-transfected with 0.06 pmol/µl of miRNA mimic, 0.3

ng/µl of Firefly luciferase reporter plasmid, as well as

0.01 ng/µl of Renilla luciferase as the control

(pRLTK; Promega Corporation). Following 24 h of transfection, the

luciferase activity was measured using the Dual Luciferase Assay

System (Promega Corporation). Each measured value of Firefly

luciferase activity was normalized to that of Renilla

luciferase activity.

Statistical analysis

The data are presented as the means ± stan-dard

error of the mean (SEM). The Student′s t-test was used to compare

differences between 2 groups, and one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey′s

post hoc test was used to compare differ-ences among multiple

groups. A two-sided value of P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference. Prism 5.0 was used for all

statistical analyses.

Results

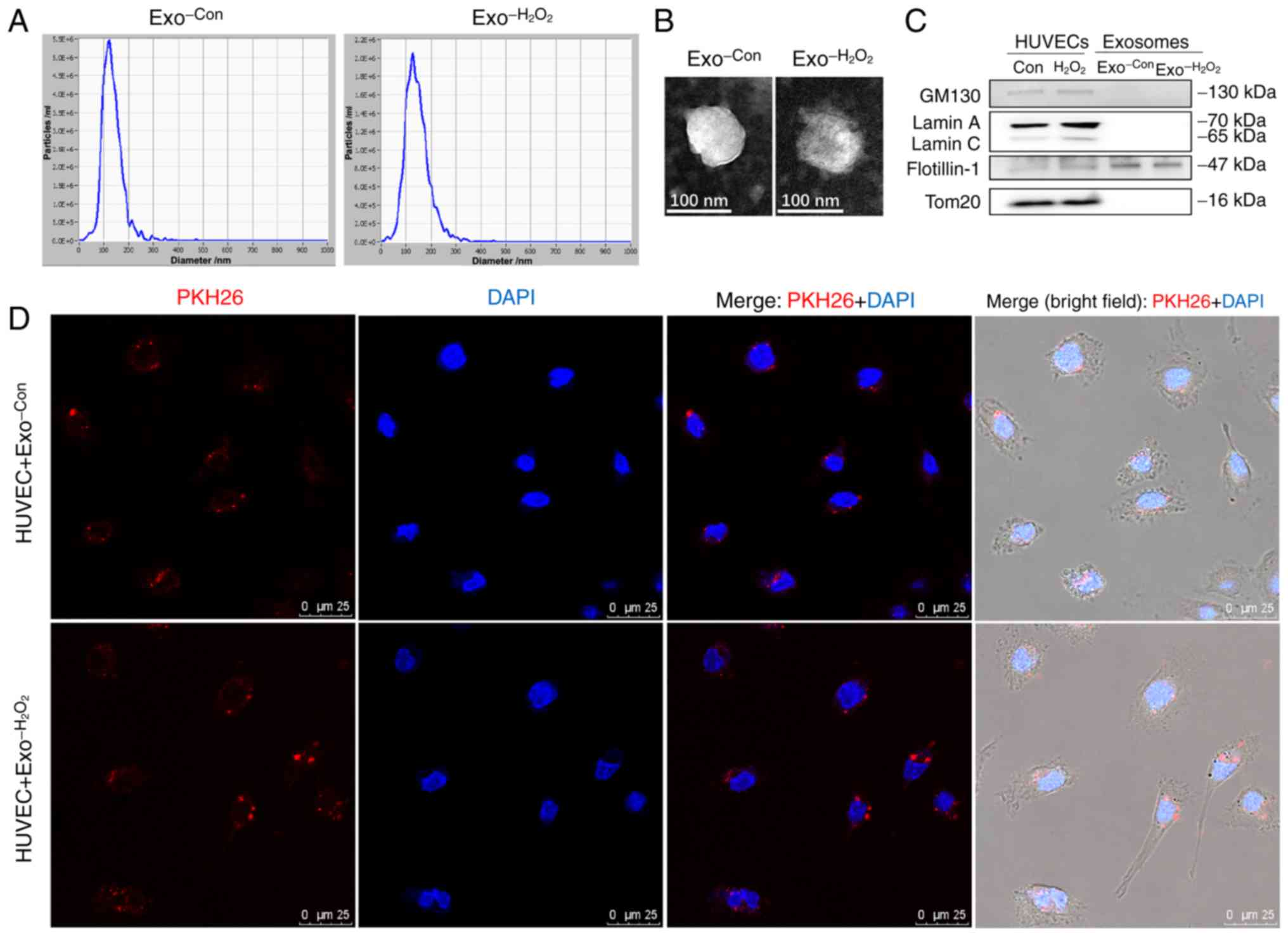

Characterization and internalization of

exosomes derived from ECs

To obtain exosomes from oxidative stress-stimu-lated

ECs, HUVECs were cultured in ECM containing 5% of exosome-free FBS

and treated with 100 µM of H2O2 (these

exosomes were termed Exo−H2O2).

The control exosomes were obtained from HUVECs without

H2O2 stimulation (these exosomes were termed

Exo-Con). Following 24 h of incubation, the conditioned

medium was collected and the exosomes were isolated. The results of

NTA revealed that the particle size distribution of the exosomes

was 50-140 nm in both groups (Fig.

1A); TEM analysis revealed the cup-shaped appearance of the

exosomes (Fig. 1B). The results

of western blot analysis demonstrated that the exosomes (marker,

flotillin 1) (10,25) were not contaminated with Golgi

(marker, GM130), nuclear (marker, Lamin A/C) and mitochondrial

(marker, Tom20) substances (Fig.

1C).

To examine the uptake of exosomes by recipient ECs,

exosomes were labeled with PKH26 and incubated with HUVECs.

Confocal laser scanning microscopic analysis revealed that the

PKH26-labled exosomes were efficiently internalized by the HUVECs

(Fig. 1D).

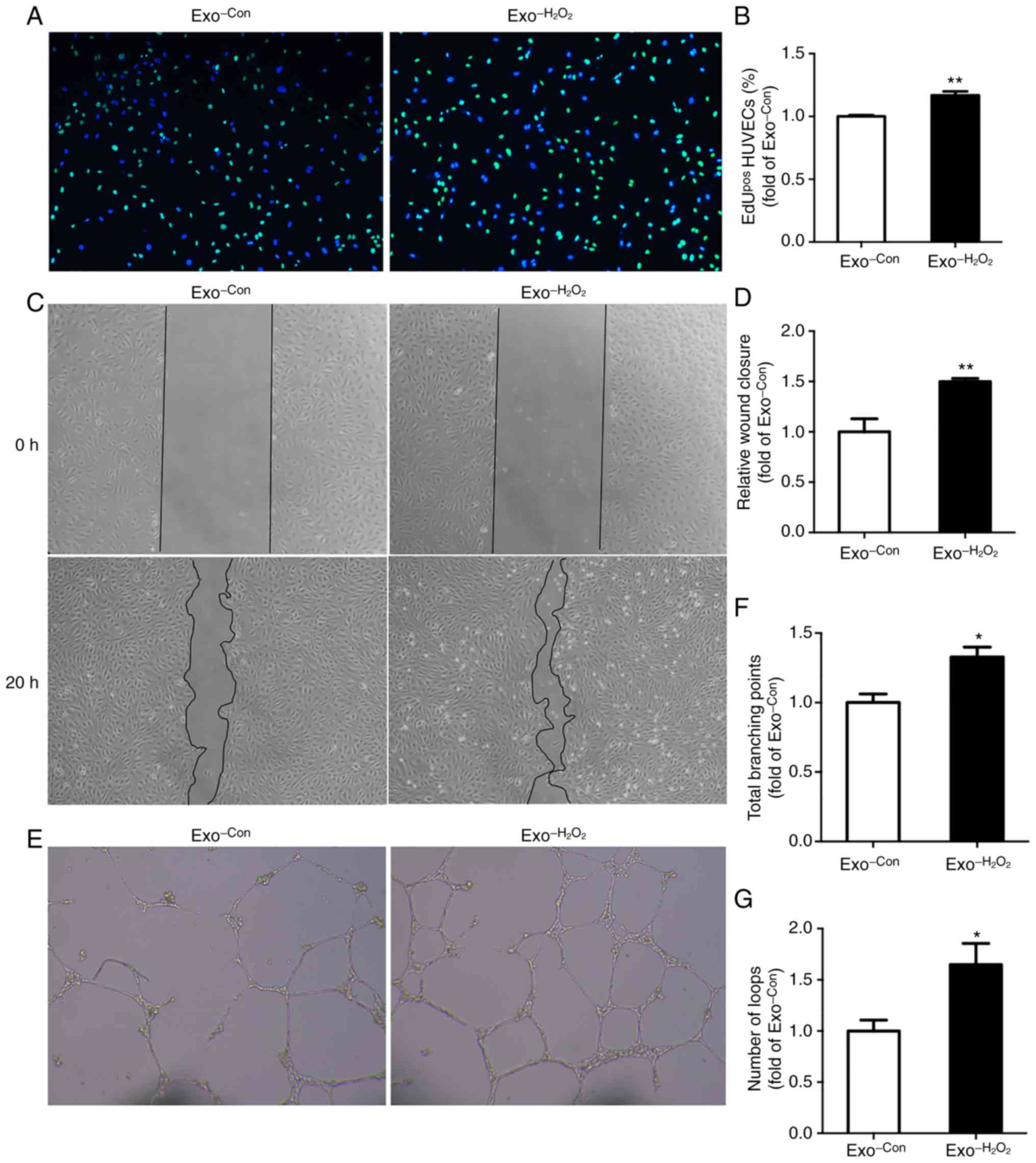

Oxidative stress-induced ECs promote EC

proliferation, migration and angiogenesis

EdU incorporation assay, scratch wound migration

assay and tube formation assay were performed to examine the

effects of exosomes released by oxidative stress-stimulated ECs on

the proliferation, migration and angiogenesis of recipient ECs,

respectively. For the EdU incorporation assay, the HUVECs were

incubated with 5 µg/ml exosomes ( Exo−H2O2 or Exo-Con). Following

48 h of incubation, HUVECs were treated with 10 µM EdU for

16 h. The proliferating cells were incorporated with EdU (green)

and nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33342 (blue). HUVEC

proliferation was increased by 1.2-fold by Exo−H2O2 compared with that by

Exo-Con(Fig. 2A and

B). For scratch wound migration assay, the HUVECs were

scratched and incubated with exosomes for 20 h. HUVEC migration was

enhanced by 1.5-fold by Exo−H2O2 compared with that by

Exo-Con(Fig. 2C and

D). For tube formation assay, the HUVECs were treated with

exosomes for 24 h and then seeded in the Matrigel, and endothelial

networks could be observed after 20 h. The numbers of total

branching points and loops increased by 1.3- and 1.6-fold,

respectively, as compared to the control (Fig. 2E-G).

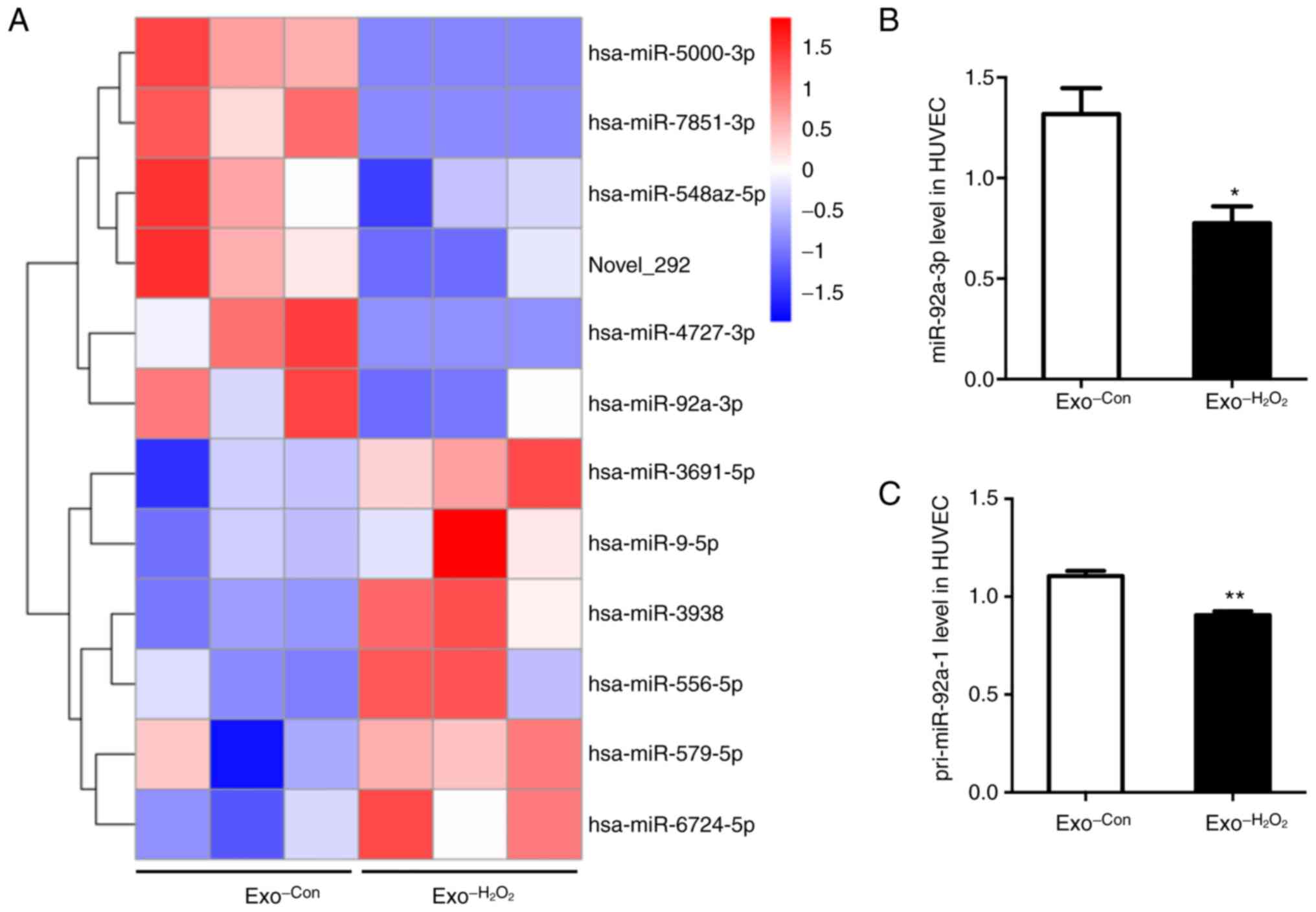

miR-92a-3p expression is inhibited by

Exo−H2O2 in recipient ECs

To explore whether miRNAs mediate the effects of

Exo−H2O2 on recipient ECs,

miRNAs differentially expressed in Exo−H2O2 - and Exo-Con-treated

HUVECs were identified by small RNA sequencing. Following 24 h of

incubation with exosomes, total RNA was extracted from the HUVECs.

The results indicated the presence of 12 miRNAs differentially

expressed between the 2 groups (Fig.

3A and Table SI). Among the

12 miRNAs, miR-92a-3p was the most abundant and has been reported

to play a key role in regulating angio-genesis (13). Therefore, miR-92a-3p was selected

for further validation by RT-qPCR. The results revealed that

miR-92a-3p expression was decreased by 40% in the Exo−H2O2 -treated HUVECs compared with that

in the Exo-Con-treated group (Fig. 3B). Furthermore, to reveal the

cause for the decrease in miR-92a-3p expression in recipient

HUVECs, the expression of primary miR-92a (pri-miR-92a-1 and

pri-miR-92a-2) in HUVECs co-cultured with exosomes was detected by

RT-PCR. The results revealed that pri-miR-92a-1 expression was

decreased by 20% (Fig. 3C) in the

Exo−H2O2 -treated HUVECs

compared with that in the control, and pri-miR-92a-2 was almost

undetectable (data not shown) in both groups. Taken together, these

results suggested that the Exo−H2O2-mediated stimulation of EC

proliferation, migration and angiogenesis may be achieved via the

inhibition of miR-92a-3p in recipient cells.

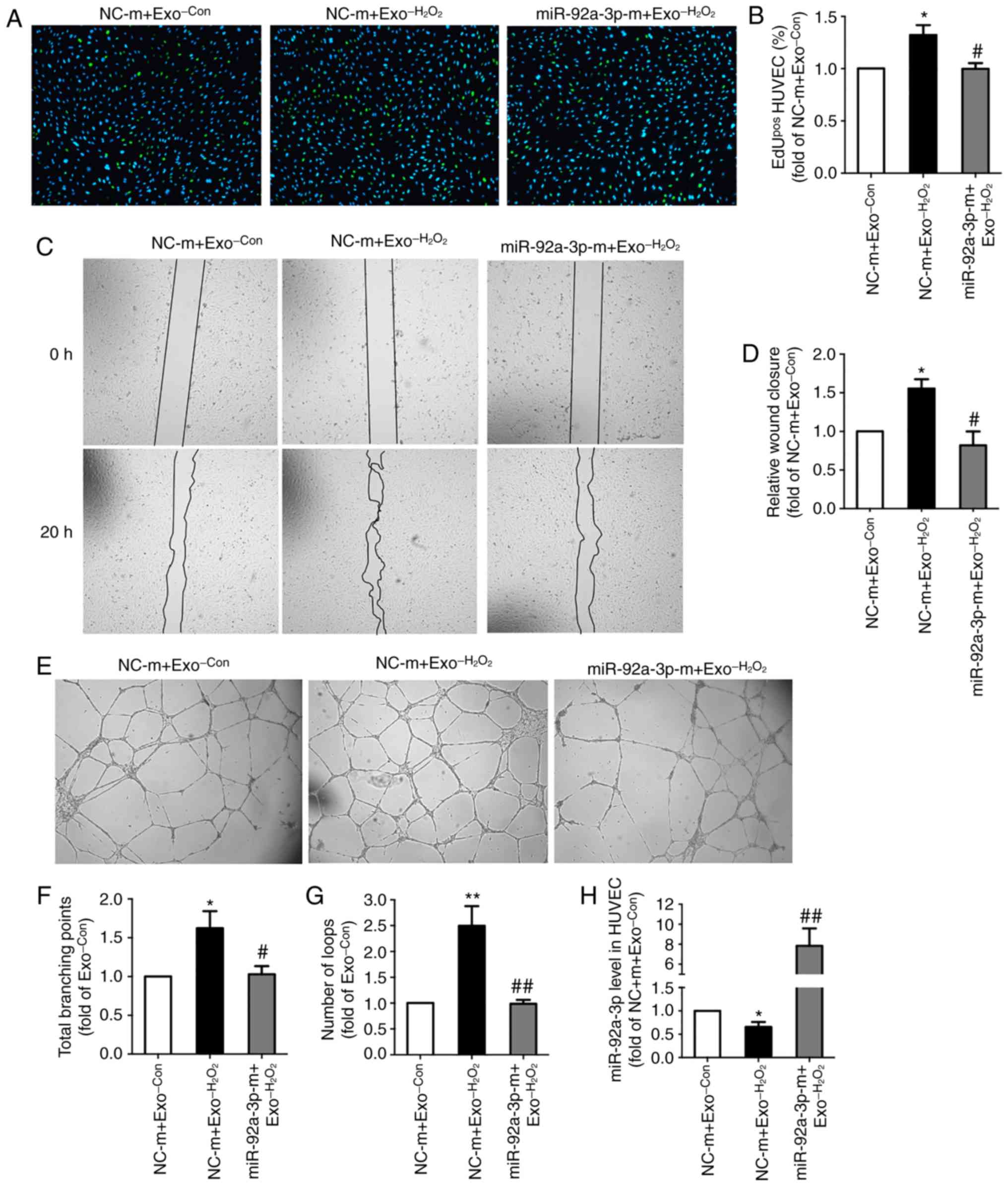

miR-92a-3p overexpression blocks the

effects of Exo−H2O2 on

recipient ECs

To investigate whether miR-92a-3p is involved in the

effects of Exo−H2O2 on target

ECs, miR-92a-3p expression was increased by transfecting the cells

with miR-92a-3p mimic (miR-92a-3p-m) for 24 h prior to the addition

of exosomes. The results of RT-qPCR revealed that miR-92a-3p

expression was significantly upregulated (Fig. 4H). EdU incorporation assay,

scratch wound migration assay and tube formation assay were

performed after incubating the HUVECs with exosomes for 24 h.

Compared with Exo-Con(group, NC-m + Exo-Con)

(set as 1), Exo−H2O2 (group,

NC-m + Exo−H2O2) promoted HUVEC

proliferation (1.3-fold) (Fig. 4A and

B), migration (1.6-fold) (Fig. 4C

and D) and angiogenic capacity (total branching points,

1.6-fold; number of loops, 2.5-fold) (Fig. 4E-G). The above-mentioned effects

induced by Exo−H2O2 were all

abrogated by the overexpression of miR-92a-3p (group, miR-92a-3p-m

+ Exo−H2O2) (Fig. 4A-G). These results indicated that

downregulated expression of miR-92a-3p mediated the role of

Exo−H2O2 in promoting

endothelial proliferation, migration and angiogenesis.

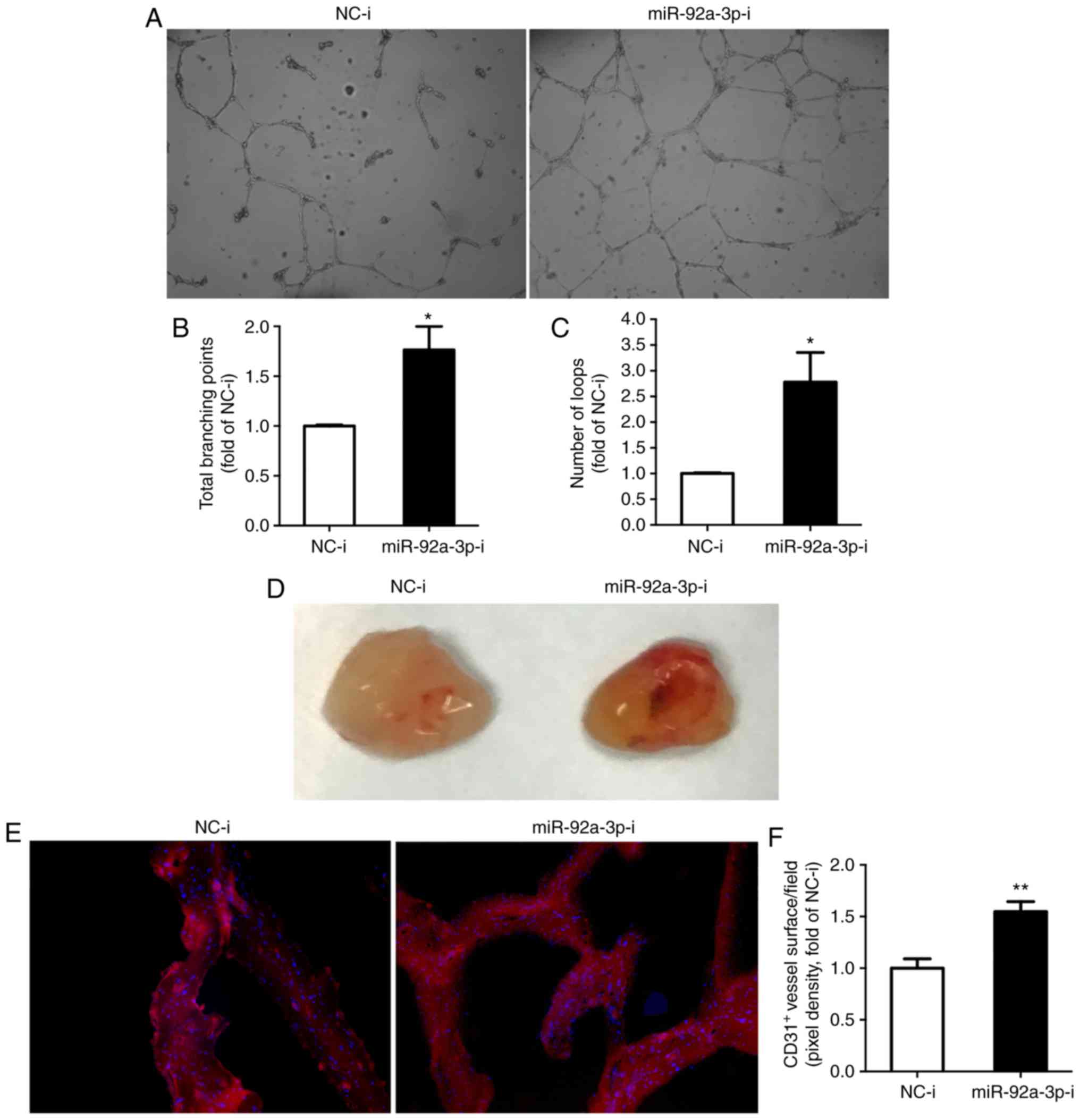

Inhibition of miR-92a-3p induces

angiogenesis

To further determine the role of miR-92a-3p in

angiogenesis, miR-92a-3p expression was directly inhibited by

transfecting the HUVECs with miR-92a-3p inhibitor for 48 h. The

decreased expression of miR-92a-3p induced EC proliferation

(1.2-fold) (Fig. S1A and B),

migration (2.0-fold) (Fig. S1C and

D) and angiogenesis in vitro (total branching points,

1.7-fold; number of loops, 2.8-fold) (Fig. 5A-C). Moreover, the in vivo

Matrigel plug assay revealed that in vivo blood vessel

formation was enhanced by 1.5-fold in the miR-92a-3p inhibitor

group (Fig. 5D-F). Taken

together, these results further indicated that Exo−H2O2 promoted angiogenesis by

decreasing miR-92a-3p expression in recipient HUVECs.

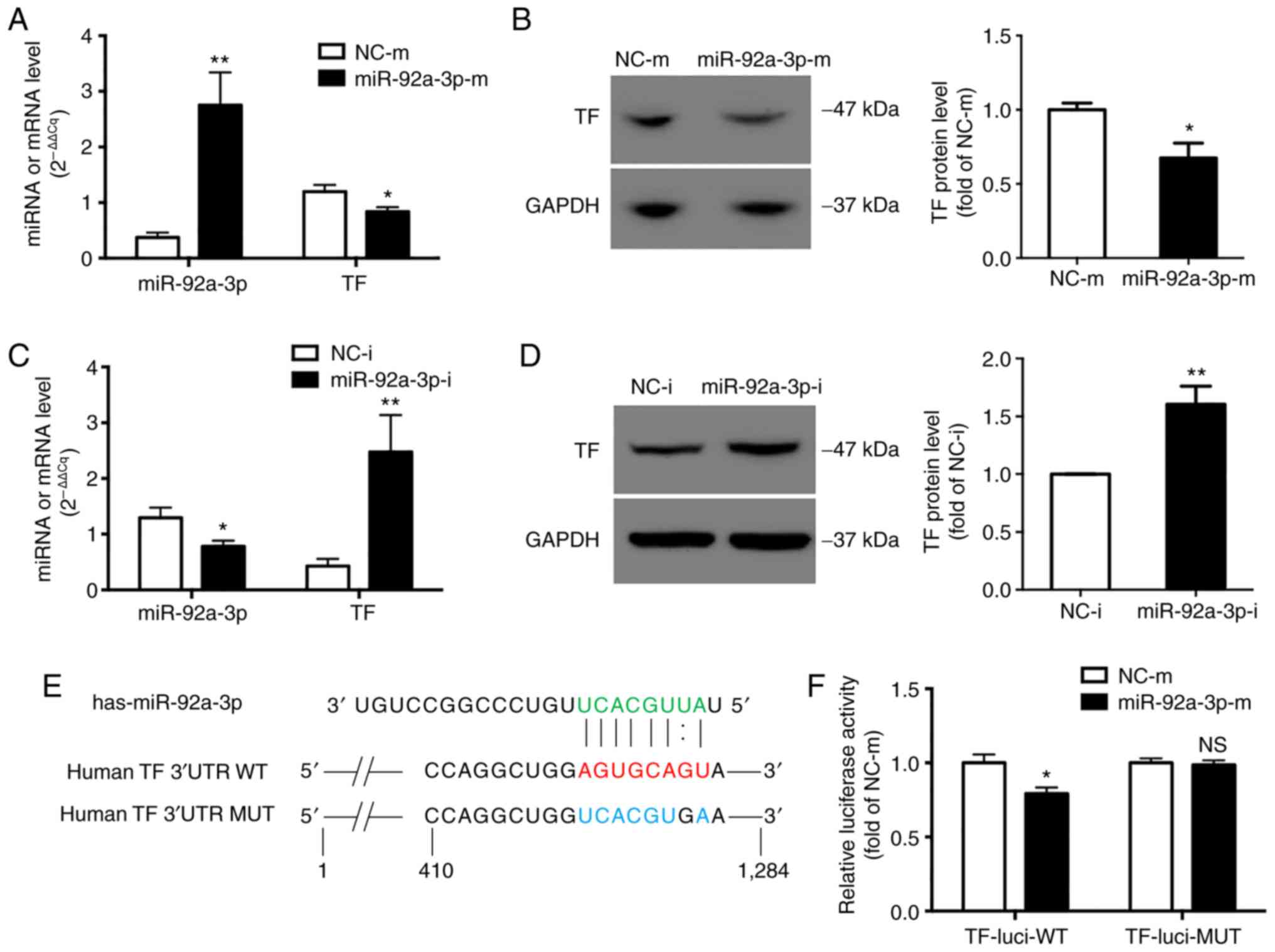

miR-92a-3p inhibits TF expression in

ECs

To identify the targets of miR-92a-3p involved in

angiogenesis, differentially expressed genes were identified in

HUVECs transfected for 48 h with miR-92a-3p inhibitor or

NC-inhibitor. The results identified 197 differentially expressed

mRNAs, among which 91 mRNAs were upregulated (Fig. S2). In addition, 4,167 targets of

miR-92a-3p were predicted using the RNAhybrid program (26), including 21 upregulated genes that

were also identified by mRNA sequencing (Fig. S2 and Table I). Among the genes closely related

to angiogenesis, TF (F3) was most significantly upregulated.

| Table IPotential targets of miR-92a-3p in

HUVECs. |

Table I

Potential targets of miR-92a-3p in

HUVECs.

| Gene | Fold change

(miR-92a-3p-i vs. NC-i) | FDR |

|---|

| TNFRSF9 | 3.5 | 4.1E-05 |

| NCOA7 | 1.9 | 5.5E-11 |

| TNFAIP2 | 3.7 | 0.0E+00 |

| IL1R1 | 1.6 | 1.2E-02 |

| NUAK2 | 2.3 | 8.2E-13 |

| INSR | 1.6 | 2.2E-04 |

| GUCY1A3 | 2.7 | 4.9E-11 |

| F3 (TF) | 7.0 | 0.0E+00 |

| AQP1 | 1.8 | 1.5E-04 |

| C2CD4A | 13.0 | 0.0E+00 |

| SOD2 | 2.0 | 1.3E-12 |

| SLC16A7 | 2.0 | 4.0E-03 |

| SPAST | 1.6 | 1.3E-03 |

| SGPP2 | 11.6 | 2.8E-05 |

| CX3CL1 | 6.7 | 0.0E+00 |

| TRAF1 | 1.6 | 5.5E-03 |

| TNIP3 | 4.9 | 3.4E-09 |

| C8orf4 | 2.2 | 2.7E-12 |

| ZC2HC1A | 2.3 | 1.5E-02 |

| ICAM1 | 2.5 | 1.2E-15 |

| CD83 | 2.1 | 2.8E-04 |

To determine whether TF is a novel target of

miR-92a-3p, gain- and loss-of-function experiments were performed

by transfecting HUVECs for 48 h with miR-92a-3p mimic or inhibitor,

respectively. The results of RT-qPCR revealed that miR-92a-3p was

successfully overexpressed (Fig.

6A) or inhibited (Fig. 6C).

Accordingly, the upregulation of miR-92a-3p inhibited TF expression

by 30% at the mRNA level (Fig.

6A) and by 33% at the protein level (Fig. 6B), whereas the down-regulation of

miR-92a-3p increased TF expression by 6.4-fold at the mRNA level

(Fig. 6C) and by 1.6-fold at the

protein level (Fig. 6D).

TF is a direct target of miR-92a-3p

To examine whether miR-92a-3p acts directly on TF

3′UTR, 2 luciferase reporter plasmids containing wild-type

(TF-luci-WT) or mutant TF 3′UTR (TF-luci-MUT) (Fig. 6E) were constructed. The results of

luciferase activity assay revealed that miR-92a-3p inhibited the

luciferase activity of TF-luci-WT constructs by approxi-mately 20%

(Fig. 6F), but failed to decrease

the luciferase activity of TF-luci-MUT (Fig. 6F).

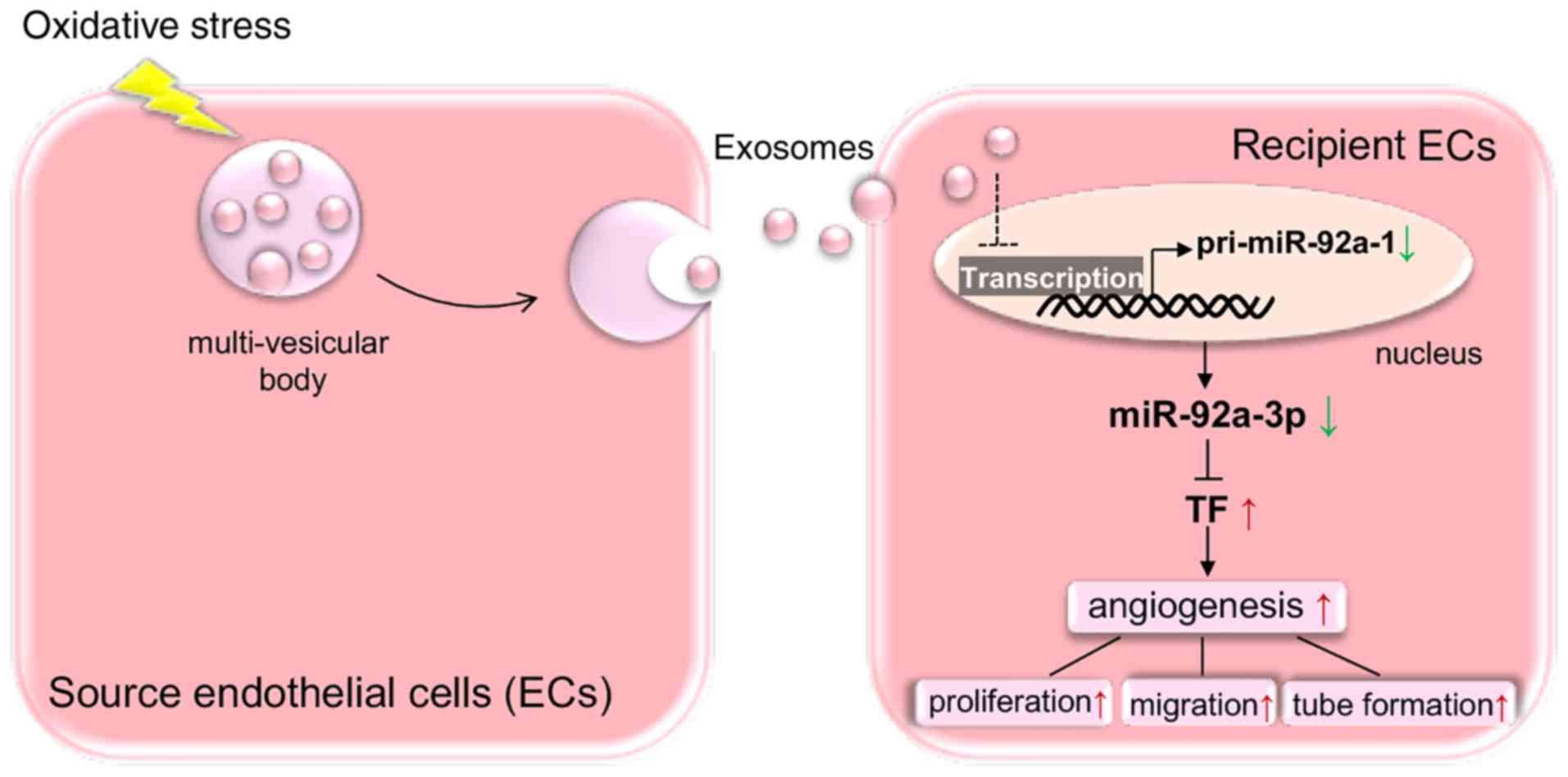

Taken together, the present study revealed a novel

proangiogenic mechanism between ECs mediated by oxidative

stress-stimulated endothelial exosomes by inhibiting the expression

of miR-92a-3p in target ECs (Fig.

7).

Discussion

Various types of pathological stimulation can lead

to vascular endothelial activation and injury. Activated or injured

ECs release characteristic extracellular vesicles (EVs), including

exosomes, microvesicles and apoptotic bodies. The content of

exosomes may partly depend on the stimuli and the state of donor

cells, which can exert distinct biological effects on target cells

(4). The roles of non-EC-derived

EVs in angiogenesis have previously been investigated (3), whereas the regulation of endothelial

exosomes in angiogenesis remains to be fully determined.

The present study aimed to investigate the role of

exosomes shed by oxidative stress-activated ECs in angio-genesis.

It was found that the exosomes derived from oxidative

stress-activated ECs promoted EC proliferation, migration and

angiogenesis, which were mediated by the downregulation of

miR-92a-3p in recipient ECs. Moreover, TF, a procoagulant and

proangiogenic gene (27), was

identified as a novel target of miR-92a-3p, and may be involved in

the role of activated endothelial exosomes in promoting

angiogenesis.

Several studies have revealed the signaling

transfer and proangiogenic effects of exosomes between non-ECs and

ECs (5-9). As regards EC-to-EC communication, it

has been reported that exosomes isolated from ECs cultured in

exosome-free medium or stimulated by interleukin-3 can promote

angiogenesis (10,11). Similarly, it was observed in the

present study that H2O2-activated endothelial

exosomes were effectively taken up by target ECs and led to an

enhanced cell proliferation, migration and angiogenesis. Although

the exosomes isolated from ECs exposed to different stimuli and in

a different state exerted similar effects, the mechanisms reported

in these studies differ. The exosomes isolated from ECs cultured in

an exosome-free medium promoted angiogenesis by suppressing the

expression of ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM) via transferring

miR-214 into recipient ECs. Endothelial exosomes generated in

response to interleukin-3 stimulation enhanced angiogenesis by

delivering miR-126-3p and pSTAT5 into recipient ECs, leading to the

activation of the pro-angiogenic pathway and the suppression of

antiangiogenic signal molecules (10,11). Herein, it was confirmed that the

exosomes isolated from H2O2-activated ECs

stimulated angiogenesis by decreasing miR-92a-3p expression in

recipient cells. The effect was similar to that observed with the

direct inhibition of miR-92a-3p in ECs observed in the present

study and other studies (14-18). Conversely, a recent study reported

that endothelial microvesicles (100-1,000 nm in size), which were

derived from ECs exposed to oxidized low-density lipoprotein

(oxLDL) stimulation, promoted angiogenesis by transferring

upregulated miR-92a-3p to recipient cells (19). The controversial role of

miR-92a-3p in regulating angio-genesis may change depending on the

experimental model and condition.

In previous findings on cell-to-cell

communications, the dysregulation of miRNAs in recipient cells has

been found to be usually caused by the delivery of miRNAs from

donor cells. In addition, intercellular protein transfer can

regulate the activity of specific signal pathways in recipient

cells (28). In the present

study, it was found that the decreased expression of miR-92a-3p in

Exo−H2O2-treated HUVEC may be

attributed to the transcriptional inhibition of miR-92a-3p, which

may be caused by the cargo in exosomes. The potential active

molecules or signaling path-ways involved in this process warrant

further investigation. miR-9-5p has also been reported to be

closely associated with angiogenesis (29-32). In the small RNA sequencing data of

the present study, miR-9-5p was significantly upreg-ulated in

Exo−H2O2-treated HUVECs. It was

also found that miR-9-5p expression was increased in both

H2O2-stimulated HUVEC and their exosomes

(data not shown). These results suggested that miR-9-5p, delivered

by Exo−H2O2-induced ECs, may

also be involved in the regulation of the biological effects on

target HUVECs, and the molecular mechanisms of miR-9-5p

upregulation differ from those of miR-92a-3p downregulation in

HUVECs caused by Exo−H2O2

exposure. miR-9-5p and miR-92a-3p may synergistically regulate EC

angiogenesis induced by Exo−H2O2, and this hypothesis is still

under investigation.

There are multiple known mRNA targets of miR-92a in

regulating cell proliferation, migration and angiogenesis, such as

Kruppel-like factor 2 (KLF2) (33), KLF4 (15), integrin subunit alpha5 (ITGA5)

(14,17) and sirtuin 1 (17). The mRNA expression profiles

obtained in the present study suggested that 91 of 197 differently

expressed genes were markedly upregulated by the inhibition of

miR-92a-3p in target ECs. A to9tal of 21 of the 91 genes were

candidate targets of miR-92a-3p predicted by the RNAhybrid program.

Among these 21 genes, TF is not only an initiator of blood

coagulation, but also an activator of angiogenesis, and may mediate

the effects of miR-92a-3p observed in the present study. There are

2 natural isoforms of TF, membrane-bound full-length (fl)TF and

soluble alternatively spliced (as)TF. Both isoforms have been found

to affect cell proliferation, migration and angiogenesis (27). It has been reported that the

inhibition of miR-19a and miR-126 promoted flTF and asTF synthesis

in EC (34). flTF has been shown

to indirectly promote angiogenesis via the induction of

proangiogenic factor expression by the FVIIa/protease-activated

receptors (PAR)-2 dependent signaling (35), whereas asTF has been reported to

directly increase the proangiogenic activity of EC independently of

the PAR-2 signaling via integrin ligation (36). In the present study, TF was found

as a new target of miR-92a-3p by gain and loss of function assays

and luciferase reporter assays.

There are some limitations to the present study.

The present study did not i) validate the pro-angiogenic effect of

oxidative stress-activated endothelial exosomes through in

vivo experiments; ii) determine the molecules or signaling

pathway, inducing the downregulation of miR-92a-3p in target EC

incubated with oxidative stress-activated endothelial exosomes;

iii) clarify the synergistically proangiogenic role of miR-9-5p

from oxidative stress-activated endothelial exosomes and miR-92a-3p

in target ECs. These questions remain to be investigated in future

studies.

In conclusion, the findings of the present study

provide new mechanistic insight into the regulation of

angiogenesis. In response to oxidative stress, exosomes are

released from ECs and convey potentially proangiogenic signals to

target ECs, eventually leading to a decreased miR-92a-3p expression

and subsequent angiogenesis. Moreover, TF may mediate the

biological effects of miR-92a-3p on ECs. Finally, this study

revealed a pro-angiogenic mechanism in ECs mediated by the

suppression of miR-92a-3p expression via oxidative

stress-stimulated endothelial exosomes (Fig. 7).

Supplementary Data

Funding

The present study was funded by grants from the

National Natural Science Foundation of China (nos. 81600340,

81770356 and 81970301), Capital Health Research and Development of

Special Funds (no. 2020-2-4084) and Peking University People′s

Hospital Research and Development Funds (no. RDY2018-26).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed in the current

study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable

request.

Authors′ contributions

HC and SL designed the study. SL performed

experiments, analyzed data and wrote the manuscript. LY performed

experiments and analyzed data. LS, ZL, CL, FZ, YC and MW performed

experiments. HC and CL critically revised the manuscript. All

authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The animal experimental protocol was approved by

Peking University People′s Hospital Ethics Committee (approval no.

2016PHC072).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

References

|

1

|

Potente M and Mäkinen T: Vascular

heterogeneity and specialization in development and disease. Nat

Rev Mol Cell Biol. 18:477–494. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Münzel T, Camici GG, Maack C, Bonetti NR,

Fuster V and Kovacic JC: Impact of oxidative stress on the heart

and vasculature: Part 2 of a 3-part series. J Am Coll Cardiol.

70:212–229. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Todorova D, Simoncini S, Lacroix R,

Sabatier F and Dignat-George F: Extracellular vesicles in

angiogenesis. Circ Res. 120:1658–1673. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Mathieu M, Martin-Jaular L, Lavieu G and

Théry C: Specificities of secretion and uptake of exosomes and

other extracellular vesicles for cell-to-cell communication. Nat

Cell Biol. 21:9–17. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Li J, Zhang Y, Liu Y, Dai X, Li W, Cai X,

Yin Y, Wang Q, Xue Y, Wang C, et al: Microvesicle-mediated transfer

of microRNA-150 from monocytes to endothelial cells promotes

angiogenesis. J Biol Chem. 288:23586–23596. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Zheng B, Yin WN, Suzuki T, Zhang XH, Zhang

Y, Song LL, Jin LS, Zhan H, Zhang H, Li JS and Wen JK:

Exosome-mediated miR-155 transfer from smooth muscle cells to

endothelial cells induces endothelial injury and promotes

atherosclerosis. Mol Ther. 25:1279–1294. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Deregibus MC, Cantaluppi V, Calogero R, Lo

Iacono M, Tetta C, Biancone L, Bruno S, Bussolati B and Camussi G:

Endothelial progenitor cell derived microvesicles activate an

angiogenic program in endothelial cells by a horizontal transfer of

mRNA. Blood. 110:2440–2448. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Gong M, Yu B, Wang J, Wang Y, Liu M, Paul

C, Millard RW, Xiao DS, Ashraf M and Xu M: Mesenchymal stem cells

release exosomes that transfer miRNAs to endothelial cells and

promote angiogenesis. Oncotarget. 8:45200–45212. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Umezu T, Tadokoro H, Azuma K, Yoshizawa S,

Ohyashiki K and Ohyashiki JH: Exosomal miR-135b shed from hypoxic

multiple myeloma cells enhances angiogenesis by targeting

factor-inhib-iting HIF-1. Blood. 124:3748–3757. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

van Balkom BW, de Jong OG, Smits M,

Brummelman J, den Ouden K, de Bree PM, van Eijndhoven MA, Pegtel

DM, Stoorvogel W, Würdinger T and Verhaar MC: Endothelial cells

require miR-214 to secrete exosomes that suppress senescence and

induce angiogenesis in human and mouse endothelial cells. Blood.

121:3997–4006. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Lombardo G, Dentelli P, Togliatto G, Rosso

A, Gili M, Gallo S, Deregibus MC, Camussi G and Brizzi MF:

Activated Stat5 trafficking via endothelial cell-derived

extracellular vesicles controls IL-3 pro-angiogenic paracrine

action. Sci Rep. 6:256892016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Kim YW and Byzova TV: Oxidative stress in

angiogenesis and vascular disease. Blood. 123:625–631. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

13

|

Sun LL, Li WD, Lei FR and Li XQ: The

regulatory role of microRNAs in angiogenesis-related diseases. J

Cell Mol Med. 22:4568–4587. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Bonauer A, Carmona G, Iwasaki M, Mione M,

Koyanagi M, Fischer A, Burchfield J, Fox H, Doebele C, Ohtani K, et

al: MicroRNA-92a controls angiogenesis and functional recovery of

ischemic tissues in mice. Science. 324:1710–1713. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Iaconetti C, Polimeni A, Sorrentino S,

Sabatino J, Pironti G, Esposito G, Curcio A and Indolfi C:

Inhibition of miR-92a increases endothelial proliferation and

migration in vitro as well as reduces neointimal proliferation in

vivo after vascular injury. Basic Res Cardiol. 107:2962012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Hinkel R, Penzkofer D, Zühlke S, Fischer

A, Husada W, Xu QF, Baloch E, van Rooij E, Zeiher AM, Kupatt C and

Dimmeler S: Inhibition of microRNA-92a protects against

ischemia/reperfusion injury in a large-animal model. Circulation.

128:1066–1075. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Daniel JM, Penzkofer D, Teske R, Dutzmann

J, Koch A, Bielenberg W, Bonauer A, Boon RA, Fischer A, Bauersachs

J, et al: Inhibition of miR-92a improves re-endothelialization and

prevents neointima formation following vascular injury. Cardiovasc

Res. 103:564–572. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Bellera N, Barba I, Rodriguez-Sinovas A,

Ferret E, Asín MA, Gonzalez-Alujas MT, Pérez-Rodon J, Esteves M,

Fonseca C, Toran N, et al: Single intracoronary injection of

encapsulated antagomir-92a promotes angiogenesis and prevents

adverse infarct remodeling. J Am Heart Assoc. 3:e0009462014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Liu Y, Li Q, Hosen MR, Zietzer A, Flender

A, Levermann P, Schmitz T, Frühwald D, Goody P, Nickenig G, et al:

Atherosclerotic conditions promote the packaging of functional

MicroRNA-92a-3p into endothelial microvesicles. Circ Res.

124:575–587. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Bang C, Batkai S, Dangwal S, Gupta SK,

Foinquinos A, Holzmann A, Just A, Remke J, Zimmer K, Zeug A, et al:

Cardiac fibroblast-derived microRNA passenger strand-enriched

exosomes mediate cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. J Clin Invest.

124:2136–2146. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Li S, Chen H, Ren J, Geng Q, Song J, Lee

C, Cao C, Zhang J and Xu N: MicroRNA-223 inhibits tissue factor

expression in vascular endothelial cells. Atherosclerosis.

237:514–520. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Li S, Geng Q, Chen H, Zhang J, Cao C,

Zhang F, Song J, Liu C and Liang W: The potential inhibitory

effects of miR-19b on vulnerable plaque formation via the

suppression of STAT3 transcriptional activity. Int J Mol Med.

41:859–867. 2018.

|

|

24

|

Rabiolo A, Bignami F, Rama P and Ferrari

G: VesselJ: A new tool for semiautomatic measurement of corneal

neovascularization. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 56:8199–8206. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

van Balkom BW, Eisele AS, Pegtel DM,

Bervoets S and Verhaar MC: Quantitative and qualitative analysis of

small RNAs in human endothelial cells and exosomes provides

insights into localized RNA processing, degradation and sorting. J

Extracell Vesicles. 4:267602015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Rehmsmeier M, Steffen P, Hochsmann M and

Giegerich R: Fast and effective prediction of microRNA/target

duplexes. RNA. 10:1507–1517. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Eisenreich A and Rauch U: Regulation and

differential role of the tissue factor isoforms in cardiovascular

biology. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 20:199–203. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Raposo G and Stahl PD: Extracellular

vesicles: A new communication paradigm? Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol.

20:509–510. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Chen X, Yang F, Zhang T, Wang W, Xi W, Li

Y, Zhang D, Huo Y, Zhang J, Yang A and Wang T: MiR-9 promotes

tumorigenesis and angiogenesis and is activated by MYC and OCT4 in

human glioma. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 38:992019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Zhuang G, Wu X, Jiang Z, Kasman I, Yao J,

Guan Y, Oeh J, Modrusan Z, Bais C, Sampath D and Ferrara N:

Tumour-secreted miR-9 promotes endothelial cell migration and

angiogenesis by activating the JAK-STAT pathway. EMBO J.

31:3513–3523. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Madelaine R, Sloan SA, Huber N, Notwell

JH, Leung LC, Skariah G, Halluin C, Paşca SP, Bejerano G, Krasnow

MA, et al: MicroRNA-9 couples brain neurogenesis and angiogenesis.

. Cell Rep. 20:1533–1542. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Zhang H, Qi M, Li S, Qi T, Mei H, Huang K,

Zheng L and Tong Q: MicroRNA-9 targets matrix metalloproteinase 14

to inhibit invasion, metastasis, and angiogenesis of neuroblastoma

cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 11:1454–1466. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Shyu KG, Wang BW, Pan CM, Fang WJ and Lin

CM: Hyperbaric oxygen boosts long noncoding RNA MALAT1 exosome

secretion to suppress microRNA-92a expression in therapeutic

angiogenesis. Int J Cardiol. 274:271–278. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Eisenreich A, Bolbrinker J and Leppert U:

Tissue factor: A conventional or alternative target in cancer

therapy. Clin Chem. 62:563–570. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Versteeg HH, Schaffner F, Kerver M,

Petersen HH, Ahamed J, Felding-Habermann B, Takada Y, Mueller BM

and Ruf W: Inhibition of tissue factor signaling suppresses tumor

growth. Blood. 111:190–199. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

van den Berg YW, van den Hengel LG, Myers

HR, Ayachi O, Jordanova E, Ruf W, Spek CA, Reitsma PH, Bogdanov VY

and Versteeg HH: Alternatively spliced tissue factor induces

angiogenesis through integrin ligation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

106:19497–19502. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|