Severe acute respiratory coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)

is the causative agent of the viral disease known as coronavirus

disease 2019 (COVID-19). This illness was first identified in

December 2019 in Wuhan, China, and has since spread throughout the

globe, culminating in a pandemic (1-3).

COVID-19 is a systemic disease that may present in a broad variety

of clinical manifestations, ranging from patients who are

asymptomatic to those who have significant respiratory symptoms and

even conditions that are life-threatening (3-5).

There are several underlying mechanisms and interactions with

pre-existing conditions, such as obesity among others, that drive

the pathogenesis of the disease, which includes the activation or

dysregulation of localized (for example, vascular) and widespread

inflammation, ultimately resulting in the failure of several organs

and eventually, mortality (2,4,6-16).

With the pandemic now characterized passed the acute

phase, attention is shifting to post-acute sequelae of COVID-19

(PASC), is often referred to as 'long COVID' and possible

preventative and therapeutic approaches are warranted (17,18). PACS comprises from a variety of

symptoms and clinical manifestations, which may include persistent

tiredness, respiratory symptoms (including dyspnea, cough, chest

tightness), joint rigidness, impaired smell and headache, whereas

respiratory, cardiovascular, neurological, cognitive, psychiatric

and gastrointestinal manifestations continue to be the most common

and potentially gravest, presentations of PASC (17,19-21). Recent evidence suggests that a

number of these manifestations may be linked to an unfavorable

impact of the disease on the mitochondrial function of various

tissues and organs (18,22).

Considering the numerous mechanisms and

pathophysiological processes that spread from the deregulation of

the immune system in acute COVID-19 and the potential mitochondrial

basis of long COVID, an ideal and efficient therapeutic option

could be a molecule which functionally behaves as a 'Swiss Army

Knife', such as melatonin (23,24). Indeed, since the SARS-CoV-2 was

classified as a pandemic, numerous studies have proposed that the

use of melatonin should be investigated as a treatment option that

is both safe and likely to be effective with regard to treating the

infection (17,25-27). Its usage is justified not just by

its superior safety profile, but also from its innumerable

beneficial actions as already reviewed extensively elsewhere

(27-30) and it has been demonstrated to

even possess broad-spectrum antiviral drug characteristics

(31,32). Moreover, various potentially

harmful and costly repurposed medicines, such as colchicine,

glucocorticoids, remdesivir and several others, have been advocated

for or utilized as therapeutic options (25,27,33-37). Additionally, despite their

importance, even the presently available vaccinations have major

adverse effects on occasion (38,39). Furthermore, as the virus has

evolved, the efficiency of the immunizations has reduced, several

strains have already been found, and more are expected to emerge,

reducing the efficacy of vaccinations even further (40). All these factors underlie the

need for further therapeutic options despite the various preventive

and already utilized medicinal options.

The present review provides a summary of the

features of melatonin that provide support to its use in the

treatment and/or prevention of SARS-CoV-2 infection and its

complications. The present review initially presents several

actions of melatonin in health and disease, followed by the key

pathophysiological mechanisms of COVID-19 and the potential

mechanisms through which melatonin would interact and mitigate

them, with a focus on long COVID and the mitochondrial functions of

melatonin.

Finally, the results of the available clinical

trials examining the use of melatonin in individuals with COVID-19

are summarized, and future steps on further examining the use of

melatonin are proposed.

Melatonin is an ubiquitous molecule that can be

found in all living organisms of the animal kingdom, with traces

even found in higher plants, such as fruits, seeds and leaves. The

term 'melatonin' originates from the Greek words 'melas', which

means black or dark, and 'tonos', which means color or tune.

Melatonin is ultimately used to describe the hormone that is

responsible for darkness (41-44). It has been preserved over the

course of evolution, perhaps for these and numerous other

additional features, and it is regarded to be an evolutionarily old

antioxidant, as it has the ability to scavenge free radicals and

stimulate antioxidant enzymes (44-47). Melatonin is primarily synthesized

and secreted (predominantly released at night) by the pineal gland

via the process of hydroxylation of the essential amino acid

tryptophan, whereas tryptophan hydroxylase is responsible for the

formation of 5-hydroxytryptophan (42,43,45,47-49). Serotonin, also known as

5-hydroxytryptamine, is the neurotransmitter that is produced as a

result of this process. Melatonin is the immediate precursor of

serotonin (42,43,45,47,48). Other organs, including the

retina, kidneys, gastrointestinal system, skin and lymphocytes,

produce a modest amount of melatonin (42,43,45,47,48). The role of melatonin in various

biosynthetic metabolic pathways is evident, with different species

having distinct biosynthetic pathways and genes that encode the

enzymes involved in the process of its biosynthesis (42,43,45,47,48). Hydoxyindole-O-methyltransferase,

an enzyme that is indirectly controlled by the photo-neural system,

is responsible for regulating the production of melatonin (42,43,45,47,48). Melatonin is primarily synthesized

at night and is bound to albumin and orosomucoid glycoprotein and

through the process of crossing the blood-brain barrier, it is able

to go to all tissues in the body and regulate brain function

(43,50,51). Melatonin production peaks at 3

months of age and decreases by 80% by the adult stage (43).

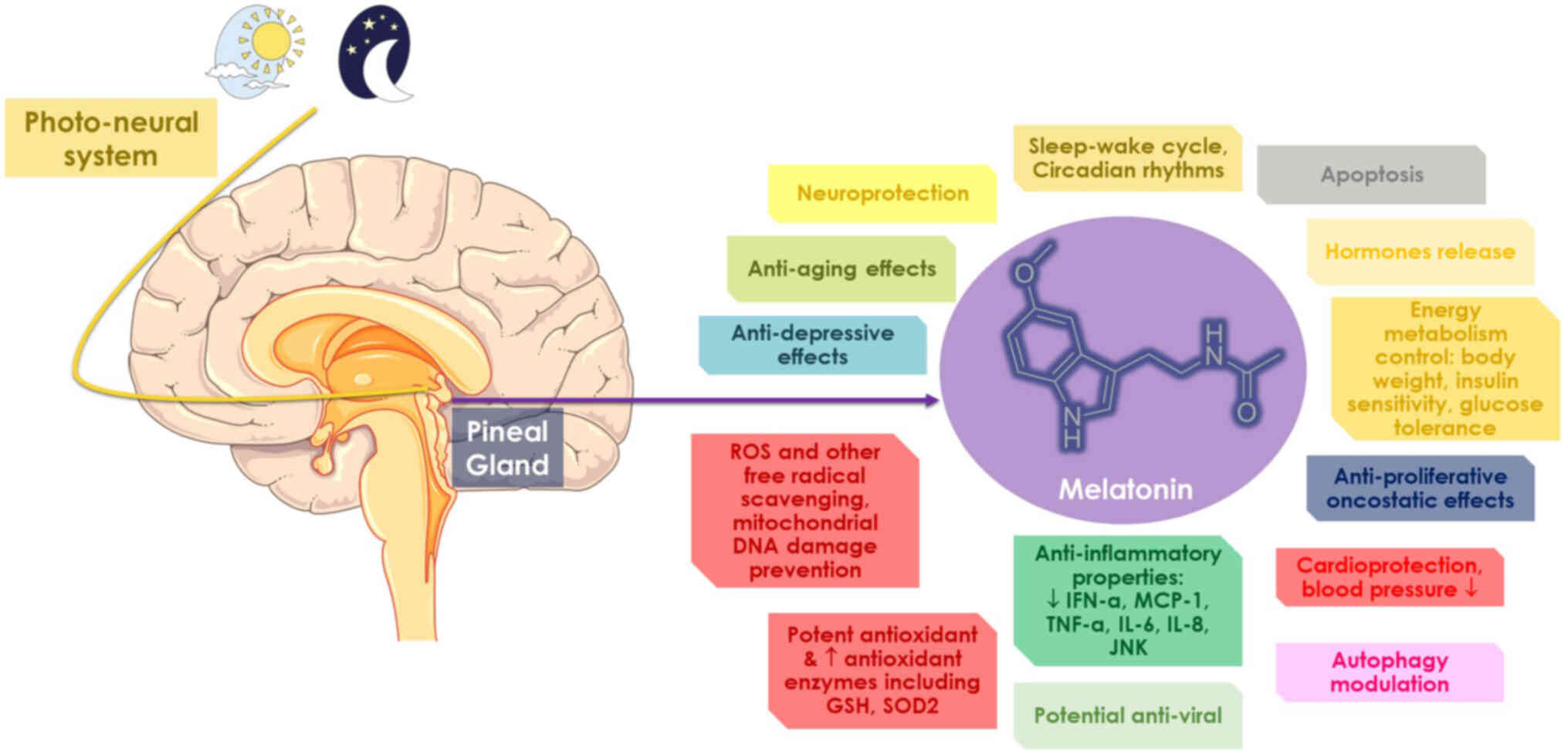

Melatonin is primarily considered to govern

physiological processes, such as circadian rhythms in humans, the

sleep-wake cycle, and it may be used as a natural sleep aid

(43,45,52-54). It is a pleiotropic hormone that

regulates several biological processes, including the release of

other hormones, apoptosis and immunological responses (32,49,55,56). The effects of melatonin are

mediated in various cells via either the melatonin receptors type 1

and type 2, G-protein coupled (membrane-independent pathway) or

indirectly (membrane independent) with nuclear orphan receptors

from either the RAR-related orphan receptor α/Z receptor family or

through other pathways, as extensively reviewed elsewhere (57). The oncostatic, anti-inflammatory

and antioxidant characteristics of melatonin indicate that it may

have potential use in the treatment of a variety of disorders

(32,43,58). Both the preventative and

therapeutic benefits of melatonin have been the subject of

substantial research in a variety of neurological conditions,

including Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, Huntington's

disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, multiple sclerosis and

epilepsy (47,59-62). In lipopolysaccharide-induced

depression, melatonin has been shown to exert antidepressant

effects, which are mediated via the regulation of autophagy

(63). Additionally, it exhibits

anti-aging properties and has the potential for use in the

management and treatment of age-related disorders in human beings

(55,64,65).

Melatonin has been widely investigated for its

anti-proliferative and anti-apoptotic properties on cancer cells,

revealing its oncostatic effects. Melatonin also reduces the loss

of cells, which is a significant benefit (66,67). Melatonin, which has been found in

both in vitro and in vivo studies, has been shown to

inhibit the development of tumors through membrane-independent and

membrane-dependent mechanisms. Melatonin has an effect on cancer

during the initiation phase, such as through DNA repair, and in the

development, progression and metastasis phases, of the

tumorigenesis process (66-68). Melatonin has potent

anti-angiogenic, anti-proliferative and ultimately anti-metastatic

properties that may be used in the treatment of a wide range of

malignancies, particularly those that have a high risk of cancer

spreading to other parts of the body. Additionally, it exerts

synergistic effects with conventional therapy, which increases the

vulnerability of cancer cells to apoptosis (66-68). Melatonin significantly reduces

the adverse effects of cardiotoxic drugs in patients with cancer

and has been shown to have a beneficial effect on coagulopathy

(49). Melatonin has been found

to improve cardiac function and lower blood pressure in patients

who have hypertension, according to clinical data from human

studies and various lines of evidence from animal studies, which

have been reviewed elsewhere (52,60,69-71). Melatonin, a substance that

neutralizes free radicals, has been utilized to mitigate the

harmful effects of certain chemical compounds, such as

methamphetamine (42,50,60,72-74). The use of melatonin as a possible

anti-viral drug for the treatment of viral illnesses, such as Ebola

and COVID-19 has been suggested (27,31,75). As extensively reviewed elsewhere

(31), melatonin exhibits a

plethora of potential antiviral actions in various viral models

(31,75), including the regulation of viral

phase separation and epitranscriptomics in long COVID-19 (17).

Studies have indicated that the anti-inflammatory

properties of melatonin involve suppressing interferon (IFN)-α,

tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), interleukin (IL)-6 and IL-8,

inhibiting Janus kinase (JNK) phosphorylation and monocyte

chemoattractant protein-1, and promoting protein degradation for

tight junction integrity, according to numerous studies (56,76-81). During the catastrophic hemorrhage

that occurs during the late phase of Ebola virus infection,

melatonin plays a crucial role in preserving the integrity of the

blood vessels and shielding endothelial cells from damage (31,75,78,82,83). It also exhibits various

biological activities, such as neuroprotective and immunomodulatory

effects, regulatory effects on reproduction, tumor preventive

effects, protective effects on gastrointestinal function and

anti-aging effects (45,84).

Melatonin is also a key factor in the regulation of

energy homeostasis, which includes the regulation of body weight,

insulin sensitivity and glucose tolerance of the body (45,85). It regulates energy metabolism,

affecting intake, flow and expenditure in the energy balance, which

in turn may be critical for preventing a variety of dysmetabolic

conditions, particularly obesity, which in turn can affect the

outcome of patients with COVID-19 (11,86-89). In addition to this, it

synchronizes the needs for energy metabolism with the daily and

yearly cyclical environmental photoperiod by means of its

chronobiotic and seasonal effects (45,85). In experimental

ischemia/reperfusion research, particularly in cases of myocardial

infarction and stroke, melatonin has been shown to successfully

prevent oxidative damage and the pathophysiological repercussions

of such damage are essential (43,82,90,91). Of utmost importance is to further

present the free radical scavenging properties of melatonin, as

these protect against mitochondrial DNA damage induced by reactive

oxygen species (ROS) displaying another of its significant effects

on mitochondrial homeostasis (24,92,93). In preclinical studies, the

administration of melatonin has been shown to increase the activity

of several antioxidant markers/enzymes, including glutathione

peroxidase and superoxide dismutase 2 (SOD2). The latter was

achieved by promoting the function of sirtuin 3, that deacetylates

SOD2, essentially facilitating its activation (24,92,94-97). Whether melatonin is present in

the mitochondria has been debatable (24,92); however, experimental evidence

demonstrates up to 100-fold higher levels of melatonin within the

mitochondria post-administration on mitochondrial membranes

(98). It appears that the

highest concentration of melatonin occurs in the mitochondria,

where the highest amount of ROS and oxidative stress occur

(99). High amounts of melatonin

in the mitochondria may be due to oligopeptide transporters 1/2 or

mitochondria generating their own melatonin, with research

indicating the existence of such enzymes in brain mitochondria

(92,94,100-102). The effects of melatonin on

mitochondria may be mediated via MT1/2 receptors, resulting in

decreased ROS generation, higher antioxidant capabilities, and

therefore, in less neural apoptosis, activating nuclear factor

erythroid 2-related factor 2, as shown in preclinical models

(24,92,103,104). Melatonin additionally prevents

stress-induced cytochrome c release from mitochondrial outer

membranes (100). Finally,

melatonin appears to increase classes of oxidative phosphorylation

(OXPHOS) proteins, thereby preventing damage (105). All these mitochondria-related

features of melatonin are of key relevance, apart from the acute

phase of COVID-19, which is strongly associated with oxidative

stress, but also long COVID, which will be discussed in the

following section. Based on novel data, melatonin is related to the

mitochondrial dysfunction/downregulation of vital mitochondrial

markers. The physiology of melatonin is summarized in the schematic

diagram in Fig. 1.

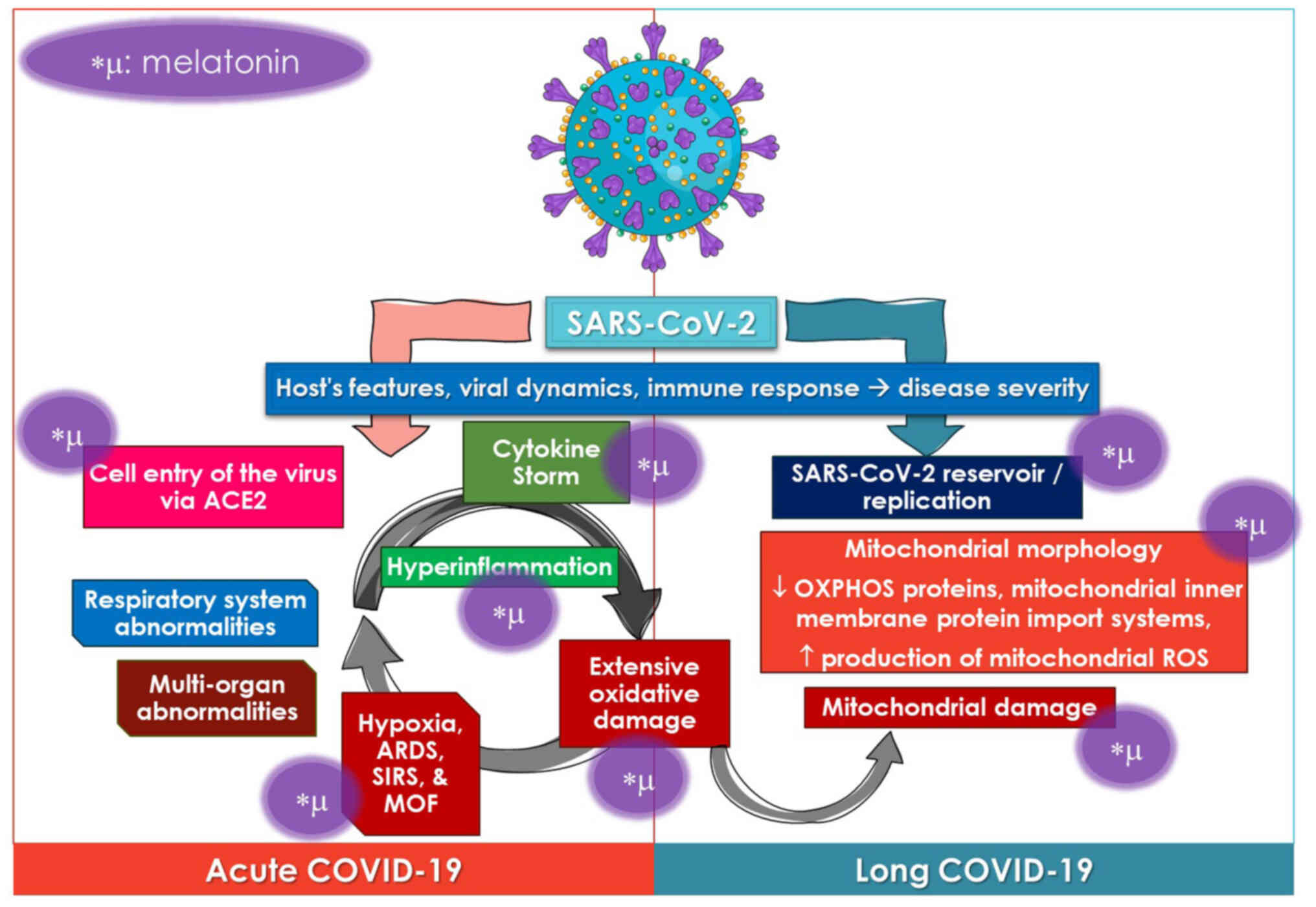

Although individuals with COVID-19 often have modest

symptoms, 20% develop substantial to severe illness that requires

hospitalization (106). The

most common include respiratory system abnormalities; however,

several other organs may also be affected (3,7,10-12,33,34). The features of the host, viral

dynamics and immune response are associated with the severity of

the disease and in general, severe COVID-19, as well as a higher

mortality rate are linked to an older age, high body mass index,

and comorbidities such as cardiovascular diseases, diabetes or

cancer (3,8,10,11,87,107,108).

The pathophysiological symptoms of COVID-19 are

partly mediated by the cell entrance of the virus, which is

enhanced by the binding of the viral spike peptides to the

angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptors in diverse organs

(2,7,8,109). In humans, ACE2 is expressed in

numerous organ systems and tissues, including the lungs (e.g., the

pneumocytes of alveolar sacs), hepatic, cardiac tissue, kidney,

gastrointestinal endothelium, adipose tissue (AT) and vascular

endothelium (3,49,110,111). This wide distribution likely

explains the multisystem involvement of the infection, while also

enhancing the magnitude of the illness in patients afflicted by

SARS-CoV-2 (49). Interstitial

pneumonia, the most prevalent lung involvement in patients with

COVID-19, if left untreated, may lead to a hypoxic status,

resulting in acute respiratory distress syndrome and/or systemic

inflammatory response syndrome and fatal multiorgan failure

(3,6,13,15,37, 108,112,113). These sepsis-related

consequences occur from a pathophysiological perspective, have the

same underlying backgrounds, ignited by the cytokine storm and

hyperinflammatory statuses with significant oxidative damage caused

by the reaction of the host to SARS-CoV-2 (49,114).

It is possible that the widespread extrapulmonary

damage observed in patients with COVID-19 may be attributed to the

presence of ACE2 receptors on cells other than those that lining

the respiratory alveoli (113).

Other organ involvement results in symptoms that are particular to

the organ; for example, gastrointestinal involvement may cause

symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, diarrhea and abdominal pain

(113). Hepatic damage, as

evidenced by increased levels of circulating liver enzymes, is also

prevalent (3). There are several

symptoms that may be associated with peripheral and central nervous

system involvement, and these include headaches and dizziness,

hyposmia or anosmia (indicative of encephalopathy), neuralgia and

Guillain-Barré syndrome (115,116). Hospitalized patients are more

likely to experience thromboembolic events, which have been

established as an independent risk factor for a poor prognosis, and

acute coronary modalities, cardiomyopathies, several types of

arrhythmias, pericarditis and various thromboembolic events

(49,117). Infections caused by SARS-CoV-2

may also result in coagulopathies, thrombocytopenia being the most

prevalent, which play a crucial role in the development of

extrapulmonary complications (8,49). In critically ill patients, deep

venous thrombosis and/or pulmonary embolism are frequent, with

pulmonary embolism being more prevalent in patients in intensive

care units (49). Inflammation,

immunological responses, coagulation cascades and the dysregulation

of the renin-angiotensin system may cause acute kidney damage in

25% of hospitalized patients (8,49,118). Finally, AT from individuals

with obesity is hypothesized to exhibit higher amounts of ACE2,

perhaps serving as a SARS-CoV-2 repository with postponed viral

shedding and may presumably contribute to long COVID (3).

Long COVID refers to patients who have experienced

persistent impairments following infection with COVID-19, including

various organs and tissues (18,119-122). A previous retrospective

analysis of 193,113 participants found an elevated risk for

respiratory impairment and pulmonary function impairment after 6

months in these patients (123). The most prevalent manifestation

is impaired diffusion capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO) (124). Survivors with a critical

illness had a greater risk of DLCO impairment, lower residual

volume and lower total lung capacity (124,125). Notably, the risk of developing

long COVID appears to differ depending on the various strains.

Studies have found a lower risk of complications, intensive care

unit admission, ventilation requirement and mortality rate in

omicron-infected individuals compared to those infected with other

variants (126). Furthermore,

as compared to the delta variant, the omicron variant has been

shown to be associated with a lower likelihood of developing long

COVID (127).

Mutations in antigenic sites are essential for

antibody and immunological evasion, and chronic symptoms in

patients with long COVID-19 may be partly due to a lessening of the

antibody response to vaccination or to variant resistance (17,122,128,129). Of note, >100 persistent

symptoms were recorded by participants at least 4 weeks after

infection, according to a scoping analysis that included 50 trials

(130). It is possible for the

majority of 'long-haulers' to have a relapse as a result of either

physical or mental stress, and cognitive impairment or memory

issues are common regardless of age (18,131). The establishment of a viral

reservoir in individuals with PASC may potentially be a possible

explanation for the improvement in clinical symptoms that occurred

following the administration of the SARS-CoV-2 immunization

(132). Reservoirs of viruses

are cells or anatomical locations where the virus may persist and

accumulate with better kinetic stability than the primary pool of

viruses that are actively reproducing (17,133,134). There is a increasing evidence

of an association between the presence of viral RNA in probable

SARS-CoV-2 reservoirs in extrapulmonary organs and tissues, and the

continued manifestation of symptoms in PASC (17,18,133,134). Patients who have been diagnosed

with COVID for a long period of time often have reactivated

viruses, which may cause mitochondrial fragmentation and disrupt

energy metabolism (18,135-137). In addition, there is evidence

of oxidative stress, abnormal amounts of mitochondrial proteins and

deficits in tetrahydrobiopterin (138,139).

In addition to the dysregulations of inflammatory

responses, COVID-19 has been connected to mitochondrial function.

Mitochondria play a critical role in the control of immune

responses and cellular metabolism (22,140-143). The shape of the mitochondria is

altered by infection, which results in a reduction in the number of

OXPHOS proteins, a reduction in the number of mitochondrial inner

membrane protein import systems, and an increase in the release of

mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (144-146). The SARS-CoV-2 virus is capable

of binding to a variety of host proteins, with mitochondrial

proteins accounting for up to 16% of the total (22,147-149). Human cells and tissues that

have been infected display a decrease in the amount of proteins and

transcripts of OXPHOS genes, an increase in glycolysis, a

suppression of OXPHOS, an increase in mitochondrial ROS production,

inflammation factors, and an increase in hypoxia inducible

factor-1α (HIF-1α) and its target genes (22,144,150-155). A disruption in the process of

mitochondrial protein synthesis may lead to an imbalance in the

proportion of mitochondrial proteins that are coded by nuclear DNA

and mitochondrial DNA, which has the potential to activate the

integrated stress response and have a number of unfavorable

repercussions (22). Recently,

Guarnieri et al (22)

demonstrated that once the viral titter peaks, this causes a

systemic reaction from the host, which includes the regulation of

mitochondrial gene transcription and glycolysis, ultimately

resulting in an antiviral immune defense mechanism. Nevertheless,

despite the fact that lung clearance and lung mitochondrial

function recovery were documented, mitochondrial function in the

heart, kidney, liver and lymph nodes continues to be damaged, which

may result in severe COVID-19 pathology (22).

Melatonin, which is well-known for its antioxidant

and anti-inflammatory qualities, has the potential to assist in

overcoming the cytokine storm that is associated with virus-related

infections, such as SARS-CoV-2, and may also be able to prevent

mitochondrial-related chronic consequences of the disease. The

anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties of melatonin may

potentially be beneficial for the treatment of possibly chronic

inflammation in patients with long COVID-19. These views are

discussed in the following section. The effects of melatonin on the

pathophysiological mechanisms of COVID-19 are summarized in the

schematic diagram in Fig. 2.

Melatonin supplementation has the potential to

target and benefit the host by reducing the exaggeration of the

innate immune system, which is essential for improving tolerance

against the invasion of pathogens (156). There is a substantial

association between the immunological response of the host,

particularly the innate immune network, and the symptoms and the

results of viral infections with the host (156,157). The overwhelming inflammatory

response that is triggered by the cytokine storm is responsible for

the majority of the detrimental effects caused by SARS-CoV-2

(36,114,156,157). Consequently, this excessive

production of cytokines is harmful to organs and tissues, which

ultimately results in oxidative damage to several organs (36,114,157,158). A considerable improvement in

the outcomes of patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection may be achieved

by downregulating the innate immune response and reducing the

inflammatory reaction. This provides evidence for the use of this

treatment method in the treatment of patients with severe COVID-19

(77,159).

Melatonin is a potent free radical scavenger and

antioxidant that directly detoxifies a wide range of ROS and

reactive nitrogen species (RNS). These ROS and RNS include hydroxyl

radicals, peroxynitrite anion, hydrogen peroxide, superoxide anion

radicals and hypoochlorous acid (25,27,50,93,160). Its electron-donating

metabolites outperform traditional antioxidants, such as vitamins C

and E, carotenoids, and NADH in reducing other oxidizing compounds

(156,161). Additionally, melatonin has an

advantageous cellular distribution due to its solubility in both

water and lipids, and it may form hydrogen bonds with proteins and

DNA to provide protection (60,161). Additionally, it upregulates the

gene expression levels of several antioxidant enzymes, thus

indirectly enhancing the cellular antioxidant capacity (161,162). By interacting on the

mitochondrial metabolism, melatonin is also able to inhibit the

production of ROS and RNS (60,156).

Melatonin is a potent anti-inflammatory chemical

that functions by rescuing the peroxynitrite anion, which leads to

the inhibition of inflammation that is not specific to any one

substance, such as carrageenan or zymosan (79,163,164). Its anti-inflammatory mechanisms

are diverse, including the suppression of the activity or

downregulation of pro-inflammatory enzymes, such as

cyclooxygenase-2, inducible nitric oxide synthase, eosinophilic

peroxidase and matrix metalloproteinase 2 (MMP)2, which are

responsible for the generation of inflammatory mediators (156,165-167). Furthermore, melatonin has the

ability to inhibit the advancement of the NLR family pyrin domain

containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome, which ultimately results in the

activation of caspase-1 and the maturation of IL-1β and IL-18. This

ultimately leads to pyroptosis, a damaging consequence of

inflammation (168-170). Melatonin is able to effectively

prevent the production of NLRP3 inflammasomes and reduce

inflammation, both of which are connected to COVID-19. This affect

is achieved by its interaction with signal transduction pathways

(167-169). Melatonin has the ability to

decrease the phosphorylation of IκBα, therefore reducing the

translocation of NF-κB into the nucleus. This, in turn, helps to

control the cytokine storm that occurs following infection with

COVID-19 and may be associated with damaging inflammation (171-174). The downregulation of melatonin

also stimulates autophagic capacity, which is often accompanied by

a reduction in the creation of inflammasomes. This may speed up the

process of tissue healing from inflammation (174,175).

Melatonin is a hormone that controls the immune

system, reducing the excessive response of both the innate immune

system and fostering the development of adaptive immunity (156,176). Some examples of pathogen

associated molecular pattern receptors are Toll-like receptors

(TLRs), Nod-like receptors (NLRs), AIM2-like receptors, GMP-AMP

synthase (cGAS) and AIM2. These receptors are responsible for

driving the innate immune system, which is the initial line of

defense against the invasion of pathogens (156,177). Innate immune cells are able to

eliminate infections with the assistance of these receptors, which

are able to identify RNA, DNA, proteins and lipids that are

associated with pathogens (156,177). However, their excessive

responses often result in injury to the tissues. Melatonin is able

to suppress the activation of TLR4, TLR9 and cGAS, which results in

a reduction in the innate immune response and a reduction in the

damage to tissue that is caused by infections, ischemia/reperfusion

and other disturbances (156,178-180).

Innate immune cells are directly affected by

melatonin, principally via the negative regulatory functions that

it has (156,181). It does this by preventing ERK

phosphorylation, which in turn prevents neutrophil migration and

the tissue damage that is associated with it (182). The administration of melatonin

lowers mast cell activation, TNF-α and IL-6 production, and

IKK/NF-κB signal transduction in activated mast cells (155,182-185). Treatment with melatonin

reverses the transformation from M2 anti-inflammatory macrophages

to M1 pro-inflammatory subtypes, which assists in the elimination

of SARS-CoV-2 and suppresses the dysfunctional hyper-inflammatory

response that is mediated by M1 macrophages (156,186). Whens physiological

circumstances are met, melatonin has the potential to boost innate

immunity, thus maintaining its protective effects against the

invasion of pathogens (31,187).

Melatonin may also have an effect on COVID-19

infection by preventing the virus from entering cells and

replicating after first entry (17,25,156). There are three enzymes that are

responsible for the entry of SARS-CoV-2 into cells: ACE2,

transmembrane protease serine 2 and A disintegrin and

metalloprotease 17 (188-190). It is possible that melatonin

can target these molecules in order to delay the entry of the

coronavirus into the cells (189). The progression of COVID-19 may

be controlled by the circadian system, while the melatonin

circadian rhythm may also be responsible for this regulation

(155,188-190). It is also possible that

melatonin may influence ACE2 activity in an indirect manner by

binding to calmodulin or MMP9 (191). Recent research has indicated

that melatonin has the potential for use as a therapeutic agent on

ACE2. It has been found that transgenic mice exhibit greater

vulnerability to SARS-CoV-2 infection, as well as delayed clinical

signs and an enhanced survival (192,193). In addition, melatonin has the

potential to decrease the activation of CD147 during a SARS-CoV-2

infection via inhibiting the production of HIF-1A (194). Research has demonstrated that

melatonin may reduce the reproduction of some viruses, such as

swine coronaviruses and Dengue virus, with the effectiveness of

this effect being dose-dependent (195,196). Melatonin may suppress

SARS-CoV-2 replication; however, to date, no animal research has

shown this to be true (197).

It is possible that melatonin inhibits viral replication by

blocking growth factor signaling (27,198,199). Due to its uniqueness and lack

of presence in host cells, the major protease (Mpro) of SARS-CoV-2

has emerged as a possible target for the development of replication

inhibitors (156). According to

the crystal structure of the SARS-CoV-2 Mpro and PF-07321332

complex, melatonin binds to the catalytic amino acid residues of

C145 and H41 via pi-sulfur/conventional hydrogen bonds and

carbon-hydrogen bonds. This suggests that melatonin works as an

effective Mpro inhibitor (156,194,200,201). In the following section, the

limited evidence of the beneficial effects of melatonin on patients

with COVID-19 is discussed, building on these potential advantages

derived from previous clinical or preclinical research.

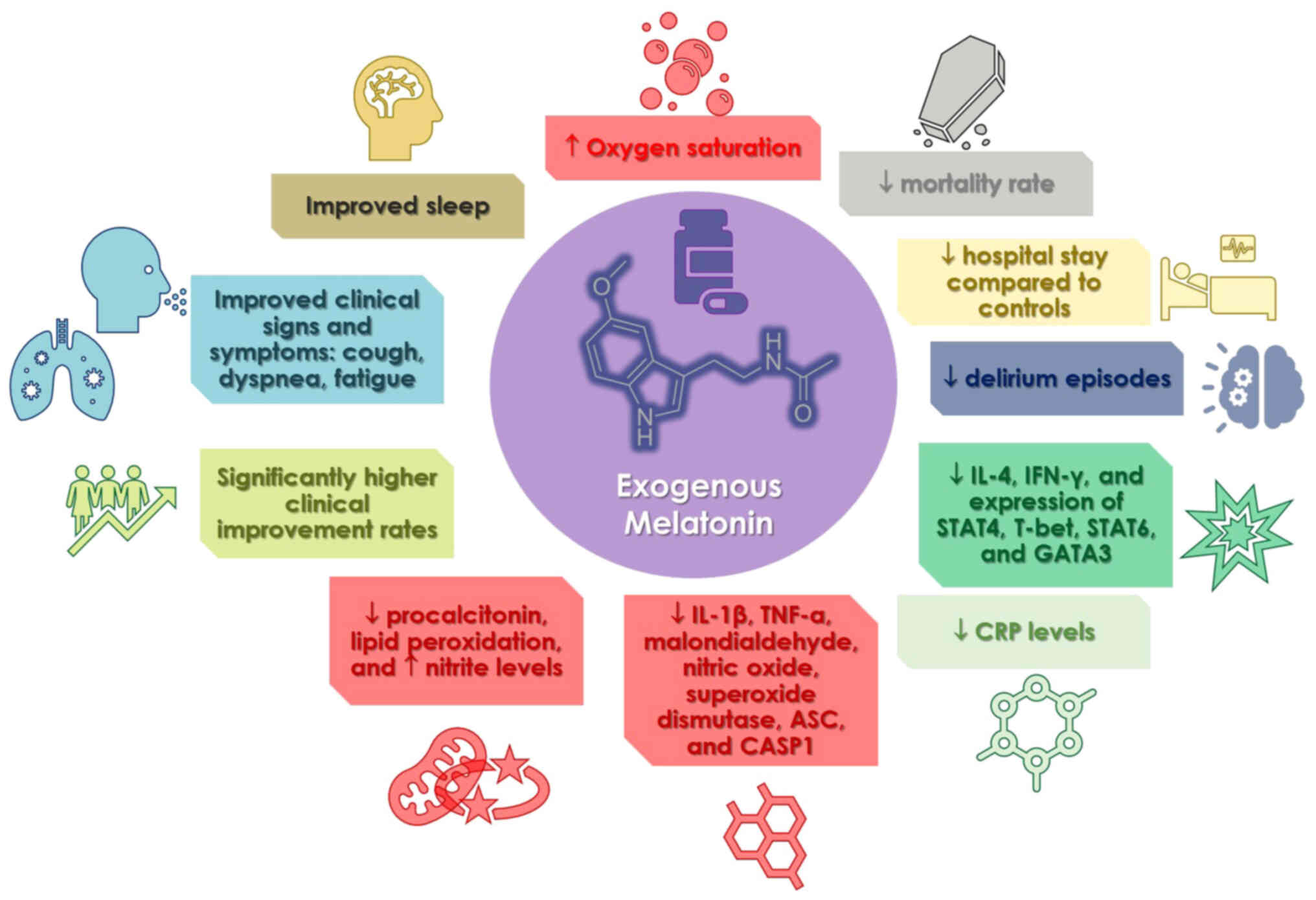

Previous research on other viral diseases, together

with the possible antiviral properties of melatonin, has led to its

suggestion as a possible therapeutic agent for COVID-19 (17,49,202). Melatonin has been tested in

clinical studies for the treatment of COVID-19. The results

revealed that the drug improved sleep quality, reduced the duration

of hospitalization and was useful as a preventative measure

(155,180,202,203). However, the studies are

restricted owing to inadequate financial assistance (melatonin is

affordable and non-patentable) (156).

Only a small number of trials have studied the

safety and effectiveness of melatonin and its therapeutic value in

COVID-19, and they were only recently evaluated in a meta-analysis

(202). The most notable

findings were that patients using melatonin had a much higher

clinical improvement rate than the control groups (202). Melatonin administration also

resulted in a reduced death rate, reduced C-reactive protein (CRP)

concentration, and length of hospital stay than the controls

(202). The study concluded

that melatonin had significant benefits on patients with COVID-19

when administered as adjuvant treatment, boosting clinical

improvement and shortening recovery time owing to shorter hospital

stays and mechanical ventilation durations (202). Other research included the

following observations: The case group exhibited lower levels of

IL-4 and IFN-γ in their plasma, as well as lower levels of signal

transducer and activator of transcription (STAT)4, T-bet, STAT6 and

GATA binding protein 3 expression in comparison to the control

group (203). In their study,

Alizadeh et al (204)

discovered that the case group exhibited a reduction in CRP levels

both before and after the ingestion of melatonin. On the other

hand, the control group did not exhibit a significant reduction in

CRP levels. A different case group exhibited an improvement in

clinical signs and symptoms, such as cough, dyspnea and tiredness,

while simultaneously exhibiting a decrease in CRP levels in

comparison to the control group (205). When compared to the control

group, the low dosage of melatonin resulted in a reduction in CRP

levels, lung involvement, a shorter time to discharge from the

hospital, and a shorter period after returning to baseline health

(206). According to the

findings of another study that examined the quality of sleep and

other outcomes of patients with COVID-19, both oxygen saturation

and sleep quality increased (207). Chavarría et al (208) demonstrated that melatonin

supplementation in patients with moderate symptoms resulted in

decreased levels of CRP, IL-6, procalcitonin and lipid

peroxidation, and elevated nitrite levels. In addition, the levels

of numerous pro-inflammatory indicators, such as IL-1β, TNF-α,

malondialdehyde, nitric oxide, superoxide dismutase, ASC and CASP1,

were found to be lower in persons who were administered melatonin

in comparison to the group that served as the control (209). Finally, patients with COVID-19

and insomnia who received prolonged-release melatonin exhibited

improvements in their sleep, a reduction in the number of episodes

of delirium, a shorter length of hospitalization, a shorter stay in

the sub-intensive care unit, and a shorter duration of therapy with

non-invasive ventilation (210). The benefits associated with the

use of melatonin in COVID-19 clinical studies are illustrated in

Fig. 3.

COVID-19 remains a critical global health concern.

Acute COVID pathophysiology linked to the cytokine storm and

oxidative stress, and long COVID research have yielded

mitochondrial dysfunction among other mechanisms, all of which can

be alleviated by providing melatonin (17). The treatment options that have

been proposed include, in addition to enhancing the function of

immune cells, the elimination of autoantibodies, immunosuppressants

and antivirals, as well as agents that possess antioxidant

properties, mitochondrial support and the generation of

mitochondrial energy (18,159). A number of these could be

achieved by including the use of melatonin as an adjuvant

therapeutic option. However, despite promising and with positive

outcomes based on a small number of clinical trials, its actions

need to be investigated further, as an ample amount of the

therapeutic potential of melatonin remains underexplored, also due

to funding limitations (27,202). On the other hand, further

clinical studies that are well-designed are warranted in order to

validate these findings (202).

Of utmost interest would be the design of trials with various time

points primarily examining the acute phase anti-inflammatory

properties and on a longer term, the preventive potential against

mitochondrial damage and long COVID pathology (17). Finally, the factors influencing

the effects of melatonin, including dosage also need to be

thoroughly explored.

Not applicable.

DAS and VEG conceptualized the study. IGL, VEG, RJR

and DAS made a substantial contribution to the interpretation and

analysis of data from the literature to be included in the review,

and wrote and prepared the draft of the manuscript. DAS and RJR

analyzed the data and provided critical revisions. All authors

contributed to manuscript revision, and have read and approved the

final version of the manuscript. Data authentication is not

applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

DAS is the Editor-in-Chief for the journal, but had

no personal involvement in the reviewing process, or any influence

in terms of adjudicating on the final decision, for this article.

The other authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

The title of the present review was inspired by

William Shakespeare's theatrical masterpiece 'A Midsummer

Night's Dream'.

No funding was received.

|

1

|

Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, Zhu F, Liu X, Zhang J,

Wang B, Xiang H, Cheng Z, Xiong Y, et al: Clinical characteristics

of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected

pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 323:1061–1069. 2020.

|

|

2

|

Georgakopoulou VE, Makrodimitri S,

Triantafyllou M, Samara S, Voutsinas PM, Anastasopoulou A,

Papageorgiou CV, Spandidos DA, Gkoufa A, Papalexis P, et al:

Immature granulocytes: Innovative biomarker for SARS-CoV-2

infection. Mol Med Rep. 26:2172022.

|

|

3

|

Lempesis IG, Karlafti E, Papalexis P,

Fotakopoulos G, Tarantinos K, Lekakis V, Papadakos SP, Cholongitas

E and Georgakopoulou VE: COVID-19 and liver injury in individuals

with obesity. World J Gastroenterol. 29:908–916. 2023.

|

|

4

|

Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, Liang WH, Ou CQ, He

JX, Liu L, Shan H, Lei CL, Hui DSC, et al: Clinical characteristics

of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 382:1708–1720.

2020.

|

|

5

|

Gracia-Ramos AE, Jaquez-Quintana JO,

Contreras-Omana R and Auron M: Liver dysfunction and SARS-CoV-2

infection. World J Gastroenterol. 27:3951–3970. 2021.

|

|

6

|

Gkoufa A, Maneta E, Ntoumas GN,

Georgakopoulou VE, Mantelou A, Kokkoris S and Routsi C: Elderly

adults with COVID-19 admitted to intensive care unit: A narrative

review. World J Crit Care Med. 10:278–289. 2021.

|

|

7

|

Georgakopoulou VE, Gkoufa A, Garmpis N,

Makrodimitri S, Papageorgiou CV, Barlampa D, Garmpi A, Chiapoutakis

S, Sklapani P, Trakas N and Damaskos C: COVID-19 and acute

pancreatitis: A systematic review of case reports and case series.

Ann Saudi Med. 42:276–287. 2022.

|

|

8

|

Georgakopoulou VE, Lembessis P, Skarlis C,

Gkoufa A, Sipsas NV and Mavragani CP: Hematological abnormalities

in COVID-19 disease: Association with type I interferon pathway

activation and disease outcomes. Front Med (Lausanne).

9:8504722022.

|

|

9

|

Madjid M, Safavi-Naeini P, Solomon SD and

Vardeny O: Potential effects of coronaviruses on the cardiovascular

system: A review. JAMA Cardiol. 5:831–840. 2020.

|

|

10

|

Lempesis IG and Georgakopoulou VE:

Implications of obesity and adiposopathy on respiratory infections;

focus on emerging challenges. World J Clin Cases. 11:2925–2933.

2023.

|

|

11

|

Lempesis IG and Georgakopoulou VE:

Physiopathological mechanisms related to inflammation in obesity

and type 2 diabetes mellitus. World J Exp Med. 13:7–16. 2023.

|

|

12

|

Georgakopoulou VE, Bali T, Adamantou M,

Asimakopoulou S, Makrodimitri S, Samara S, Triantafyllou M,

Voutsinas PM, Eliadi I, Karamanakos G, et al: Acute hepatitis and

liver injury in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 infection. Exp

Ther Med. 24:6912022.

|

|

13

|

Mathioudakis N, Zachiotis M, Papadakos S,

Triantafyllou M, Karapanou A, Samara S, Karamanakos G, Spandidos

DA, Papalexis P, Damaskos C, et al: Onodera's prognostic

nutritional index: Comparison of its role in the severity and

outcomes of patients with COVID-19 during the periods of alpha,

delta and omicron variant predominance. Exp Ther Med.

24:6752022.

|

|

14

|

Cholongitas E, Bali T, Georgakopoulou VE,

Kamiliou A, Vergos I, Makrodimitri S, Samara S, Triantafylou M,

Basoulis D, Eliadi I, et al: Comparison of liver function test- and

inflammation-based prognostic scores for coronavirus disease 2019:

A single center study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 34:1165–1171.

2022.

|

|

15

|

Georgakopoulou VE, Gkoufa A, Damaskos C,

Papalexis P, Pierrakou A, Makrodimitri S, Sypsa G, Apostolou A,

Asimakopoulou S, Chlapoutakis S, et al: COVID-19-associated acute

appendicitis in adults. A report of five cases and a review of the

literature. Exp Ther Med. 24:4822022.

|

|

16

|

Cholongitas E, Bali T, Georgakopoulou VE,

Giannakodimos A, Gyftopoulos A, Georgilaki V, Gerogiannis D,

Basoulis D, Eliadi I, Karamanakos G, et al: Prevalence of abnormal

liver biochemistry and its impact on COVID-19 patients' outcomes: A

single-center Greek study. Ann Gastroenterol. 35:290–296. 2022.

|

|

17

|

Loh D and Reiter RJ: Melatonin: Regulation

of viral phase separation and epitranscriptomics in post-acute

sequelae of COVID-19. Int J Mol Sci. 23:81222022.

|

|

18

|

Davis HE, McCorkell L, Vogel JM and Topol

EJ: Long COVID: Major findings, mechanisms and recommendations. Nat

Rev Microbiol. 21:133–146. 2023.

|

|

19

|

Mehandru S and Merad M: Pathological

sequelae of long-haul COVID. Nat Immunol. 23:194–202. 2022.

|

|

20

|

Vehar S, Boushra M, Ntiamoah P and Biehl

M: Post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection: Caring for the

'long-haulers'. Cleve Clin J Med. 88:267–272. 2021.

|

|

21

|

Bali T, Georgakopoulou VE, Kamiliou A,

Vergos I, Adamantou M, Vlachos S, Ermidis G, Sipsas NV, Samarkos M

and Cholongitas E: Abnormal liver function tests and coronavirus

disease 2019: A close relationship. J Viral Hepat. 30:79–80.

2023.

|

|

22

|

Guarnieri JW, Dybas JM, Fazelinia H, Kim

MS, Frere J, Zhang Y, Soto Albrecht Y, Murdock DG, Angelin A, Singh

LN, et al: Core mitochondrial genes are down-regulated during

SARS-CoV-2 infection of rodent and human hosts. Sci Transl Med.

15:eabq15332023.

|

|

23

|

Reiter RJ, Tan DX and Galano A: Melatonin:

Exceeding expectations. Physiology (Bethesda). 29:325–333.

2014.

|

|

24

|

Reiter RJ, Sharma R, Rosales-Corral S, de

Campos Zuccari DAP and de Almeida Chuffa LG: Melatonin: A

mitochondrial resident with a diverse skill set. Life Sci.

301:1206122022.

|

|

25

|

Reiter RJ, Sharma R, Tan DX, Neel RL,

Simko F, Manucha W, Rosales-Corral S and Cardinali DP: Melatonin

use for SARS-CoV-2 infection: Time to diversify the treatment

portfolio. J Med Virol. 94:2928–2930. 2022.

|

|

26

|

Romero A, Ramos E, López-Muñoz F,

Gil-Martín E, Escames G and Reiter RJ: Coronavirus disease 2019

(COVID-19) and its neuroinvasive capacity: Is it time for

melatonin? Cell Mol Neurobiol. 42:489–500. 2022.

|

|

27

|

Reiter RJ, Sharma R, Simko F,

Dominguez-Rodriguez A, Tesarik J, Neel RL, Slominski AT,

Kleszczynski K, Martin-Gimenez VM, Manucha W and Cardinali DP:

Melatonin: Highlighting its use as a potential treatment for

SARS-CoV-2 infection. Cell Mol Life Sci. 79:1432022.

|

|

28

|

Mouffak S, Shubbar Q, Saleh E and El-Awady

R: Recent advances in management of COVID-19: A review. Biomed

Pharmacother. 143:1121072021.

|

|

29

|

Wichniak A, Kania A, Siemiński M and

Cubała WJ: Melatonin as a potential adjuvant treatment for COVID-19

beyond sleep disorders. Int J Mol Sci. 22:86232021.

|

|

30

|

Ramos E, López-Muñoz F, Gil-Martín E, Egea

J, Álvarez-Merz I, Painuli S, Semwal P, Martins N, Hernández-Guijo

JM and Romero A: The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): key

emphasis on melatonin safety and therapeutic efficacy. Antioxidants

(Basel). 10:11522021.

|

|

31

|

Boga JA, Coto-Montes A, Rosales-Corral SA,

Tan DX and Reiter RJ: Beneficial actions of melatonin in the

management of viral infections: A new use for this 'molecular

handyman'? Rev Med Virol. 22:323–338. 2012.

|

|

32

|

Juybari KB, Pourhanifeh MH, Hosseinzadeh

A, Hemati K and Mehrzadi S: Melatonin potentials against viral

infections including COVID-19: Current evidence and new findings.

Virus Res. 287:1981082020.

|

|

33

|

Georgakopoulou VE, Gkoufa A, Makrodimitri

S, Basoulis D, Tsakanikas A, Karamanakos G, Mastrogianni E,

Voutsinas PM, Spandidos DA, Papageorgiou CV, et al: Early 3-day

course of remdesivir for the prevention of the progression to

severe COVID-19 in the elderly: A single-centre, real-life cohort

study. Exp Ther Med. 26:4622023.

|

|

34

|

Basoulis D, Tsakanikas A, Gkoufa A,

Bitsani A, Karamanakos G, Mastrogianni E, Georgakopoulou VE,

Makrodimitri S, Voutsinas PM, Lamprou P, et al: Effectiveness of

oral nirmatrelvir/ritonavir vs intravenous three-day remdesivir in

preventing progression to severe COVID-19: A single-center,

prospective, comparative, real-life study. Viruses.

15:15152023.

|

|

35

|

Papadopoulou A, Karavalakis G,

Papadopoulou E, Xochelli A, Bousiou Z, Vogiatzoglou A, Papayanni

PG, Georgakopoulou A, Giannaki M, Stavridou F, et al:

SARS-CoV-2-specific T cell therapy for severe COVID-19: a

randomized phase 1/2 trial. Nat Med. 29:2019–2029. 2023.

|

|

36

|

Karlafti E, Paramythiotis D, Pantazi K,

Georgakopoulou VE, Kaiafa G, Papalexis P, Protopapas AA, Ztriva E,

Fyntanidou V and Savopoulos C: Drug-induced liver injury in

hospitalized patients during SARS-CoV-2 infection. Medicina

(Kaunas). 58:18482022.

|

|

37

|

Georgakopoulou VE, Basoulis D, Voutsinas

PM, Makrodimitri S, Samara S, Triantafyllou M, Eliadi I,

Karamanakos G, Papageorgiou CV, Anastasopoulou A, et al: Factors

predicting poor outcomes of patients treated with tocilizumab for

COVID-19-associated pneumonia: A retrospective study. Exp Ther Med.

24:7242022.

|

|

38

|

Gkoufa A, Saridaki M, Georgakopoulou VE,

Spandidos DA and Cholongitas E: COVID-19 vaccination in liver

transplant recipients (Review). Exp Ther Med. 25:2912023.

|

|

39

|

Elrashdy F, Tambuwala MM, Hassan SS, Adadi

P, Seyran M, Abd El-Aziz TM, Rezaei N, Lal A, Aljabali AAA,

Kandimalla R, et al: Autoimmunity roots of the thrombotic events

after COVID-19 vaccination. Autoimmun Rev. 20:1029412021.

|

|

40

|

Taskou C, Sarantaki A, Beloukas A,

Georgakopoulou VE, Daskalakis G, Papalexis P and Lykeridou A:

Knowledge and attitudes of healthcare professionals regarding

perinatal influenza vaccination during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Vaccines (Basel). 11:1682023.

|

|

41

|

Goeser S, Ruble J and Chandler L:

Melatonin: Historical and clinical perspectives. J Pharmaceut Care

Pain Symptom Contr. 5:37–49. 1997.

|

|

42

|

Beyer CE, Steketee JD and Saphier D:

Antioxidant properties of melatonin-an emerging mystery. Biochem

Pharmacol. 56:1265–1272. 1998.

|

|

43

|

Ahmad SB, Ali A, Bilal M, Rashid SM, Wani

AB, Bhat RR and Rehman MU: Melatonin and health: Insights of

melatonin action, biological functions, and associated disorders.

Cell Mol Neurobiol. 43:2437–2458. 2023.

|

|

44

|

Hardeland R, Balzer I, Poeggeler B,

Fuhrberg B, Uría H, Behrmann G, Wolf R, Meyer TJ and Reiter RJ: On

the primary functions of melatonin in evolution: Mediation of

photoperiodic signals in a unicell, photooxidation, and scavenging

of free radicals. J Pineal Res. 18:104–111. 1995.

|

|

45

|

Cipolla-Neto J and Amaral FGD: Melatonin

as a hormone: New physiological and clinical insights. Endocr Rev.

39:990–1028. 2018.

|

|

46

|

Manchester LC, Coto-Montes A, Boga JA,

Andersen LP, Zhou Z, Galano A, Vriend J, Tan DX and Reiter RJ:

Melatonin: An ancient molecule that makes oxygen metabolically

tolerable. J Pineal Res. 59:403–419. 2015.

|

|

47

|

Hardeland R, Reiter R, Poeggeler B and Tan

DX: The significance of the metabolism of the neurohormone

melatonin: Antioxidative protection and formation of bioactive

substances. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 17:347–357. 1993.

|

|

48

|

Reiter RJ: Pineal melatonin: Cell biology

of its synthesis and of its physiological interactions. Endocr Rev.

12:151–180. 1991.

|

|

49

|

Hosseinzadeh A, Bagherifard A, Koosha F,

Amiri S, Karimi-Behnagh A, Reiter RJ and Mehrzadi S: Melatonin

effect on platelets and coagulation: Implications for a

prophylactic indication in COVID-19. Life Sci. 307:1208662022.

|

|

50

|

Tan DX, Hardeland R, Manchester LC,

Paredes SD, Korkmaz A, Sainz RM, Mayo JC, Fuentes-Broto L and

Reiter RJ: The changing biological roles of melatonin during

evolution: From an antioxidant to signals of darkness, sexual

selection and fitness. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc. 85:607–623.

2010.

|

|

51

|

Andersen LPH, Gögenur I, Rosenberg J and

Reiter RJ: Pharmacokinetics of melatonin: The missing link in

clinical efficacy? Clin Pharmacokinet. 55:1027–1030. 2016.

|

|

52

|

Reiter RJ, Tan DX and Korkmaz A: The

circadian melatonin rhythm and its modulation: Possible impact on

hypertension. J Hypertens Suppl. 27:S17–S20. 2009.

|

|

53

|

Vriend J and Reiter RJ: Melatonin feedback

on clock genes: A theory involving the proteasome. J Pineal Res.

58:1–11. 2015.

|

|

54

|

Erren TC and Reiter RJ: Melatonin: A

universal time messenger. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. 36:187–192.

2015.

|

|

55

|

Mehrzadi S, Karimi MY, Fatemi A, Reiter RJ

and Hosseinzadeh A: SARS-CoV-2 and other coronaviruses negatively

influence mitochondrial quality control: Beneficial effects of

melatonin. Pharmacol Ther. 224:1078252021.

|

|

56

|

Mauriz JL, Collado PS, Veneroso C, Reiter

RJ and González-Gallego J: A review of the molecular aspects of

melatonin's anti-inflammatory actions: Recent insights and new

perspectives. J Pineal Res. 54:1–14. 2013.

|

|

57

|

Slominski RM, Reiter RJ,

Schlabritz-Loutsevitch N, Ostrom RS and Slominski AT: Melatonin

membrane receptors in peripheral tissues: Distribution and

functions. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 351:152–166. 2012.

|

|

58

|

Gurunathan S, Kang MH, Choi Y, Reiter RJ

and Kim JH: Melatonin: A potential therapeutic agent against

COVID-19. Melatonin Res. 4:30–69. 2021.

|

|

59

|

Naskar A, Prabhakar V, Singh R, Dutta D

and Mohanakumar KP: Melatonin enhances L-DOPA therapeutic effects,

helps to reduce its dose, and protects dopaminergic neurons in

1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine-induced Parkinsonism

in mice. J Pineal Res. 58:262–274. 2015.

|

|

60

|

Reiter RJ, Mayo JC, Tan DX, Sainz RM,

Alatorre-Jimenez M and Qin L: Melatonin as an antioxidant: Under

promises but over delivers. J Pineal Res. 61:253–278. 2016.

|

|

61

|

Ramos E, Patiño P, Reiter RJ, Gil-Martín

E, Marco-Contelles J, Parada E, de Los Rios C, Romero A and Egea J:

Ischemic brain injury: New insights on the protective role of

melatonin. Free Radic Biol Med. 104:32–53. 2017.

|

|

62

|

Sanchez-Barcelo EJ, Rueda N, Mediavilla

MD, Martinez-Cue C and Reiter RJ: Clinical uses of melatonin in

neurological diseases and mental and behavioural disorders. Curr

Med Chem. 24:3851–3878. 2017.

|

|

63

|

Ali T, Rahman SU, Hao Q, Li W, Liu Z, Ali

Shah F, Murtaza I, Zhang Z, Yang X, Liu G and Li S: Melatonin

prevents neuroinflammation and relieves depression by attenuating

autophagy impairment through FOXO3a regulation. J Pineal Res.

69:e126672020.

|

|

64

|

Vriend J and Reiter RJ: Melatonin as a

proteasome inhibitor. Is there any clinical evidence? Life Sci.

115:8–14. 2014.

|

|

65

|

Mayo JC, Sainz RM, González Menéndez P,

Cepas V, Tan DX and Reiter RJ: Melatonin and sirtuins: A 'not-so

unexpected' relationship. J Pineal Res. 62:e123912017.

|

|

66

|

Gurunathan S, Qasim M, Kang MH and Kim JH:

Role and therapeutic potential of melatonin in various type of

cancers. Onco Targets Ther. 14:2019–2052. 2021.

|

|

67

|

Pourhanifeh MH, Mehrzadi S, Kamali M and

Hosseinzadeh A: Melatonin and gastrointestinal cancers: Current

evidence based on underlying signaling pathways. Eur J Pharmacol.

886:1734712020.

|

|

68

|

Reiter RJ, Rosales-Corral SA, Tan DX,

Acuna-Castroviejo D, Qin L, Yang SF and Xu K: Melatonin, a full

service anti-cancer agent: inhibition of initiation, progression

and metastasis. Int J Mol Sci. 18:8432017.

|

|

69

|

Reiter RJ, Tan DX, Paredes SD and

Fuentes-Broto L: Beneficial effects of melatonin in cardiovascular

disease. Ann Med. 42:276–285. 2010.

|

|

70

|

Galano A, Tan DX and Reiter RJ: Melatonin:

A versatile protector against oxidative DNA damage. Molecules.

23:5302018.

|

|

71

|

Simko F, Baka T, Paulis L and Reiter RJ:

Elevated heart rate and nondipping heart rate as potential targets

for melatonin: A review. J Pineal Res. 61:127–137. 2016.

|

|

72

|

Reiter RJ, Tan DX, Kim SJ and Qi W:

Melatonin as a pharmacological agent against oxidative damage to

lipids and DNA. Proc West Pharmacol Soc. 41:229–236. 1998.

|

|

73

|

Reiter RJ, Tan DX, Rosales-Corral S and

Manchester LC: The universal nature, unequal distribution and

antioxidant functions of melatonin and its derivatives. Mini Rev

Med Chem. 13:373–384. 2013.

|

|

74

|

García JJ, López-Pingarrón L,

Almeida-Souza P, Tres A, Escudero P, García-Gil FA, Tan DX, Reiter

RJ, Ramírez JM and Bernal-Pérez M: Protective effects of melatonin

in reducing oxidative stress and in preserving the fluidity of

biological membranes: A review. J Pineal Res. 56:225–237. 2014.

|

|

75

|

Tan DX, Korkmaz A, Reiter RJ and

Manchester LC: Ebola virus disease: Potential use of melatonin as a

treatment. J Pineal Res. 57:381–384. 2014.

|

|

76

|

Reiter RJ, Ma Q and Sharma R: Treatment of

Ebola and other infectious diseases: Melatonin 'goes viral'.

Melatonin Res. 3:43–57. 2020.

|

|

77

|

Reiter RJ, Sharma R, Ma Q, Liu C, Manucha

W, González P and Dominguez-Rodriguez A: Metabolic plasticity of

activated immune cells: Advantages for suppression of COVID-19

disease by melatonin. Melatonin Res. 3:362–379. 2020.

|

|

78

|

Reiter RJ, Sharma R, Ma Q,

Dominquez-Rodriguez A, Marik PE and Abreu-Gonzalez P: Melatonin

inhibits COVID-19-induced cytokine storm by reversing aerobic

glycolysis in immune cells: A mechanistic analysis. Med Drug

Discov. 6:1000442020.

|

|

79

|

Sarkar S, Chattopadhyay A and

Bandyopadhyay D: Multiple strategies of melatonin protecting

against cardiovascular injury related to inflammation: A

comprehensive overview. Melatonin Res. 4:1–29. 2021.

|

|

80

|

Esposito E and Cuzzocrea S:

Antiinflammatory activity of melatonin in central nervous system.

Curr Neuropharmacol. 8:228–242. 2010.

|

|

81

|

Hardeland R, Cardinali DP, Brown GM and

Pandi-Perumal SR: Melatonin and brain inflammaging. Prog Neurobiol.

127-128:46–63. 2015.

|

|

82

|

Farez MF, Mascanfroni ID, Méndez-Huergo

SP, Yeste A, Murugaiyan G, Garo LP, Balbuena Aguirre ME, Patel B,

Ysrraelit MC, Zhu C, et al: Melatonin contributes to the

seasonality of multiple sclerosis relapses. Cell. 162:1338–1352.

2015.

|

|

83

|

Dominguez-Rodriguez A, Abreu-Gonzalez P,

Marik PE and Reiter RJ: Melatonin, cardiovascular disease and

COVID-19: A potential therapeutic strategy? Melatonin Res.

3:318–321. 2020.

|

|

84

|

Ozdemir G, Ergün Y, Bakariş S, Kılınç M,

Durdu H and Ganiyusufoğlu E: Melatonin prevents retinal oxidative

stress and vascular changes in diabetic rats. Eye (Lond).

28:1020–1027. 2014.

|

|

85

|

Gheban BA, Rosca IA and Crisan M: The

morphological and functional characteristics of the pineal gland.

Med Pharm Rep. 92:226–234. 2019.

|

|

86

|

Cipolla-Neto J, Amaral F, Afeche SC, Tan

DX and Reiter RJ: Melatonin, energy metabolism, and obesity: A

review. J Pineal Res. 56:371–381. 2014.

|

|

87

|

Lempesis IG, Hoebers N, Essers Y, Jocken

JWE, Dineen R, Blaak EE, Manolopoulos KN and Goossens GH: Distinct

inflammatory signatures of upper and lower body adipose tissue and

adipocytes in women with normal weight or obesity. Front Endocrinol

(Lausanne). 14:12057992023.

|

|

88

|

Lempesis IG, Varrias D, Sagris M, Attaran

RR, Altin ES, Bakoyiannis C, Palaiodimos L, Dalamaga M and

Kokkinidis DG: Obesity and peripheral artery disease: Current

evidence and controversies. Curr Obes Rep. 12:264–279. 2023.

|

|

89

|

Lempesis IG, Apple SJ, Duarte G,

Palaiodimos L, Kalaitzopoulos DR, Dalamaga M and Kokkinidis DG:

Cardiometabolic effects of SGLT2 inhibitors on polycystic ovary

syndrome. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 39:e36822023.

|

|

90

|

Lempesis IG, Tsilingiris D, Liu J and

Dalamaga M: Of mice and men: Considerations on adipose tissue

physiology in animal models of obesity and human studies. Metabol

Open. 15:1002082022.

|

|

91

|

Simko F, Hrenak J, Dominguez-Rodriguez A

and Reiter RJ: Melatonin as a putative protection against

myocardial injury in COVID-19 infection. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol.

13:921–924. 2020.

|

|

92

|

Mirza-Aghazadeh-Attari M, Reiter RJ,

Rikhtegar R, Jalili J, Hajalioghli P, Mihanfar A, Majidinia M and

Yousefi B: Melatonin: An atypical hormone with major functions in

the regulation of angiogenesis. IUBMB Life. 72:1560–1584. 2020.

|

|

93

|

Melhuish Beaupre LM, Brown GM, Gonçalves

VF and Kennedy JL: Melatonin's neuroprotective role in mitochondria

and its potential as a biomarker in aging, cognition and

psychiatric disorders. Transl Psychiatry. 11:3392021.

|

|

94

|

Reiter RJ, Rosales-Corral S, Tan DX, Jou

MJ, Galano A and Xu B: Melatonin as a mitochondria-targeted

antioxidant: One of evolution's best ideas. Cell Mol Life Sci.

74:3863–3881. 2017.

|

|

95

|

Reiter RJ, Ma Q and Sharma R: Melatonin in

mitochondria: Mitigating clear and present dangers. Physiology

(Bethesda). 35:86–95. 2020.

|

|

96

|

Wakatsuki A, Okatani Y, Shinohara K,

Ikenoue N, Kaneda C and Fukaya T: Melatonin protects fetal rat

brain against oxidative mitochondrial damage. J Pineal Res.

30:22–28. 2001.

|

|

97

|

Reiter RJ, Tan DX, Rosales-Corral S,

Galano A, Jou MJ and Acuna-Castroviejo D: Melatonin mitigates

mitochondrial meltdown: Interactions with SIRT3. Int J Mol Sci.

19:24392018.

|

|

98

|

Han L, Wang H, Li L, Li X, Ge J, Reiter RJ

and Wang Q: Melatonin protects against maternal obesity-associated

oxidative stress and meiotic defects in oocytes via the

SIRT3-SOD2-dependent pathway. J Pineal Res. 63:e124312017.

|

|

99

|

Mar tín M, Macías M, Escames G, León J and

Acuña-Castroviejo D: Melatonin but not vitamins C and E maintains

glutathione homeostasis in t-butyl hydroperoxide-induced

mitochondrial oxidative stress. FASEB J. 14:1677–1679. 2000.

|

|

100

|

Venegas C, García JA, Escames G, Ortiz F,

López A, Doerrier C, García-Corzo L, López LC, Reiter RJ and

Acuña-Castroviejo D: Extrapineal melatonin: Analysis of its

subcellular distribution and daily fluctuations. J Pineal Res.

52:217–227. 2012.

|

|

101

|

Suofu Y, Li W, Jean-Alphonse FG, Jia J,

Khattar NK, Li J, Baranov SV, Leronni D, Mihalik AC, He Y, et al:

Dual role of mitochondria in producing melatonin and driving GPCR

signaling to block cytochrome c release. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

114:E7997–E8006. 2017.

|

|

102

|

He C, Wang J, Zhang Z, Yang M, Li Y, Tian

X, Ma T, Tao J, Zhu K, Song Y, et al: Mitochondria synthesize

melatonin to ameliorate its function and improve mice oocyte's

quality under in vitro conditions. Int J Mol Sci. 17:9392016.

|

|

103

|

Tan DX and Reiter RJ: Mitochondria: The

birth place, battle ground and the site of melatonin metabolism in

cells. Melatonin Res. 2:44–66. 2019.

|

|

104

|

Chumboatong W, Thummayot S, Govitrapong P,

Tocharus C, Jittiwat J and Tocharus J: Neuroprotection of

agomelatine against cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury through an

antiapoptotic pathway in rat. Neurochem Int. 102:114–122. 2017.

|

|

105

|

de Vries HE, Witte M, Hondius D,

Rozemuller AJ, Drukarch B, Hoozemans J and van Horssen J:

Nrf2-induced antioxidant protection: A promising target to

counteract ROS-mediated damage in neurodegenerative disease? Free

Radic Biol Med. 45:1375–1383. 2008.

|

|

106

|

Martin M, Macias M, Escames G, Reiter RJ,

Agapito MT, Ortiz GG and Acuña-Castroviejo D: Melatonin-induced

increased activity of the respiratory chain complexes I and IV can

prevent mitochondrial damage induced by ruthenium red in vivo. J

Pineal Res. 28:242–248. 2000.

|

|

107

|

Sheleme T, Bekele F and Ayela T: Clinical

presentation of patients infected with coronavirus disease 19: A

systematic review. Infect Dis (Auckl). 13:11786337209520762020.

|

|

108

|

Lempesis IG, Georgakopoulou VE, Papalexis

P, Chrousos GP and Spandidos DA: Role of stress in the pathogenesis

of cancer (Review). Int J Oncol. 63:1242023.

|

|

109

|

Georgakopoulou VE, Gkoufa A, Bougea A,

Basoulis D, Tsakanikas A, Makrodimitri S, Karamanakos G, Spandidos

DA, Angelopoulou E and Sipsas NV: Characteristics and outcomes of

elderly patients with Parkinson's disease hospitalized due to

COVID-19-associated pneumonia. Med Int (Lond). 3:342023.

|

|

110

|

Bourgonje AR, Abdulle AE, Timens W,

Hillebrands JL, Navis GJ, Gordijn SJ, Bolling MC, Dijkstra G, Voors

AA, Osterhaus AD, et al: Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2),

SARS-CoV-2 and the pathophysiology of coronavirus disease 2019

(COVID-19). J Pathol. 251:228–248. 2020.

|

|

111

|

Ozkurt Z and Çınar Tanrıverdi E: COVID-19:

Gastrointestinal manifestations, liver injury and recommendations.

World J Clin Cases. 10:1140–1163. 2022.

|

|

112

|

Zhang Q, Xiang R, Huo S, Zhou Y, Jiang S,

Wang Q and Yu F: Molecular mechanism of interaction between

SARS-CoV-2 and host cells and interventional therapy. Signal

Transduct Target Ther. 6:2332021.

|

|

113

|

Georgakopoulou VE, Gkoufa A, Tsakanikas A,

Makrodimitri S, Karamanakos G, Basoulis D, Voutsinas PM, Eliadi I,

Bougea A, Spandidos DA, et al: Predictors of COVID-19-associated

mortality among hospitalized elderly patients with dementia. Exp

Ther Med. 26:3952023.

|

|

114

|

Thakur V, Ratho RK, Kumar P, Bhatia SK,

Bora I, Mohi GK, Saxena SK, Devi M, Yadav D and Mehariya S:

Multi-organ involvement in COVID-19: Beyond pulmonary

manifestations. J Clin Med. 10:4462021.

|

|

115

|

Martín Giménez VM, de las Heras N, Ferder

L, Lahera V, Reiter RJ and Manucha W: Potential Effects of

melatonin and micronutrients on mitochondrial dysfunction during a

cytokine storm typical of oxidative/inflammatory diseases.

Diseases. 9:302021.

|

|

116

|

Bougea A, Georgakopoulou VE, Palkopoulou

M, Efthymiopoulou E, Angelopoulou E, Spandidos DA and Zikos P:

New-onset non-motor symptoms in patients with Parkinson's disease

and post-COVID-19 syndrome: A prospective cross-sectional study.

Med Int (Lond). 3:232023.

|

|

117

|

Ahmad I and Rathore FA: Neurological

manifestations and complications of COVID-19: A literature review.

J Clin Neurosci. 77:8–12. 2020.

|

|

118

|

Long B, Brady WJ, Koyfman A and Gottlieb

M: Cardiovascular complications in COVID-19. Am J Emerg Med.

38:1504–1507. 2020.

|

|

119

|

Legrand M, Bell S, Forni L, Joannidis M,

Koyner JL, Liu K and Cantaluppi V: Pathophysiology of

COVID-19-associated acute kidney injury. Nat Rev Nephrol.

17:751–764. 2021.

|

|

120

|

Thaweethai T, Jolley SE, Karlson EW,

Levitan EB, Levy B, McComsey GA, McCorkell L, Nadkarni GN,

Parthasarathy S, Singh U, et al: Development of a definition of

postacute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection. JAMA. 329:1934–1946.

2023.

|

|

121

|

Efstathiou V, Stefanou MI, Demetriou M,

Siafakas N, Makris M, Tsivgoulis G, Zoumpourlis V, Kympouropoulos

SP, Tsoporis JN, Spandidos DA, et al: Long COVID and

neuropsychiatric manifestations (Review). Exp Ther Med.

23:3632022.

|

|

122

|

Efstathiou V, Stefanou MI, Demetriou M,

Siafakas N, Katsantoni E, Makris M, Tsivgoulis G, Zoumpourlis V,

Kympouropoulos SP, Tsoporis JN, et al: New-onset neuropsychiatric

sequelae and 'long-COVID'syndrome (Review). Exp Ther Med.

24:7052022.

|

|

123

|

Daugherty SE, Guo Y, Heath K, Dasmariñas

MC, Jubilo KG, Samranvedhya J, Lipsitch M and Cohen K: Risk of

clinical sequelae after the acute phase of SARS-CoV-2 infection:

Retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 373:n10982021.

|

|

124

|

Huang L, Li X, Gu X, Zhang H, Ren L, Guo

L, Liu M, Wang Y, Cui D, Wang Y, et al: Health outcomes in people 2

years after surviving hospitalisation with COVID-19: A longitudinal

cohort study. Lancet Respir Med. 10:863–876. 2022.

|

|

125

|

Huang C, Huang L, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Gu

X, Kang L, Guo L, Liu M, Zhou X, et al: 6-Month consequences of

COVID-19 in patients discharged from hospital: A cohort study.

Lancet. 397:220–232. 2021.

|

|

126

|

E E, R F, Öi E, Im L, M L, S R, E W, C J,

M H and A M: Impaired diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide is

common in critically ill Covid-19 patients at four months

post-discharge. Respir Med. 182:1063942021.

|

|

127

|

Antonelli M, Pujol JC, Spector TD,

Ourselin S and Steves CJ: Risk of long COVID associated with delta

versus omicron variants of SARS-CoV-2. Lancet. 399:2263–2264.

2022.

|

|

128

|

Quaglia F, Salladini E, Carraro M,

Minervini G, Tosatto SCE and Le Mercier P: SARS-CoV-2 variants

preferentially emerge at intrinsically disordered protein sites

helping immune evasion. FEBS J. 289:4240–4250. 2022.

|

|

129

|

Lipsitch M, Krammer F, Regev-Yochay G,

Lustig Y and Balicer RD: SARS-CoV-2 breakthrough infections in

vaccinated individuals: Measurement, causes and impact. Nat Rev

Immunol. 22:57–65. 2022.

|

|

130

|

Hayes LD, Ingram J and Sculthorpe NF: More

than 100 persistent symptoms of SARS-CoV-2 (long COVID): A scoping

review. Front Med (Lausanne). 8:7503782021.

|

|

131

|

Davis HE, Assaf GS, McCorkell L, Wei H,

Low RJ, Re'em Y, Redfield S, Austin JP and Akrami A: Characterizing

long COVID in an international cohort: 7 Months of symptoms and

their impact. EClinicalMedicine. 38:1010192021.

|

|

132

|

Gaebler C, Wang Z, Lorenzi JCC, Muecksch

F, Finkin S, Tokuyama M, Cho A, Jankovic M, Schaefer-Babajew D,

Oliveira TY, et al: Evolution of antibody immunity to SARS-CoV-2.

Nature. 591:639–644. 2021.

|

|

133

|

Proal AD and VanElzakker MB: Long COVID or

post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC): An overview of biological

factors that may contribute to persistent symptoms. Front

Microbiol. 12:6981692021.

|

|

134

|

Kalkeri R, Goebel S and Sharma GD:

SARS-CoV-2 shedding from asymptomatic patients: Contribution of

potential extrapulmonary tissue reservoirs. Am J Trop Med Hyg.

103:18–21. 2020.

|

|

135

|

Zubchenko S, Kril I, Nadizhko O, Matsyura

O and Chopyak V: Herpesvirus infections and post-COVID-19

manifestations: A pilot observational study. Rheumatol Int.

42:1523–1530. 2022.

|

|

136

|

Su Y, Yuan D, Chen DG, Ng RH, Wang K, Choi

J, Li S, Hong S, Zhang R, Xie J, et al: Multiple early factors

anticipate post-acute COVID-19 sequelae. Cell. 185:881–895.e20.

2022.

|

|

137

|

Schreiner P, Harrer T, Scheibenbogen C,

Lamer S, Schlosser A, Naviaux RK and Prusty BK: Human herpesvirus-6

reactivation, mitochondrial fragmentation, and the coordination of

antiviral and metabolic phenotypes in myalgic

encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Immunohorizons.

4:201–215. 2020.

|

|

138

|

Peluso MJ, Deeks SG, Mustapic M,

Kapogiannis D, Henrich TJ, Lu S, Goldberg SA, Hoh R, Chen JY,

Martinez EO, et al: SARS-CoV-2 and mitochondrial proteins in

neural-derived exosomes of COVID-19. Ann Neurol. 91:772–781.

2022.

|

|

139

|

Villaume WA: Marginal BH4 deficiencies,

iNOS, and self-perpetuating oxidative stress in post-acute sequelae

of Covid-19. Med Hypotheses. 163:1108422022.

|

|

140

|

Saleh J, Peyssonnaux C, Singh KK and Edeas

M: Mitochondria and microbiota dysfunction in COVID-19

pathogenesis. Mitochondrion. 54:1–7. 2020.

|

|

141

|

Singh KK, Chaubey G, Chen JY and

Suravajhala P: Decoding SARS-CoV-2 hijacking of host mitochondria

in COVID-19 pathogenesis. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 319:C258–C267.

2020.

|

|

142

|

Marchi S, Guilbaud E, Tait SWG, Yamazaki T

and Galluzzi L: Mitochondrial control of inflammation. Nat Rev

Immunol. 23:159–173. 2023.

|

|

143

|

West AP and Shadel GS: Mitochondrial DNA

in innate immune responses and inflammatory pathology. Nat Rev

Immunol. 17:363–375. 2017.

|

|

144

|

Wang P, Luo R, Zhang M, Wang Y, Song T,

Tao T, Li Z, Jin L, Zheng H, Chen W, et al: A cross-talk between

epithelium and endothelium mediates human alveolar-capillary injury

during SARS-CoV-2 infection. Cell Death Dis. 11:10422020.

|

|

145

|

Cortese M, Lee JY, Cerikan B, Neufeldt CJ,

Oorschot VMJ, Köhrer S, Hennies J, Schieber NL, Ronchi P, Mizzon G,

et al: Integrative imaging reveals SARS-CoV-2-induced reshaping of

subcellular morphologies. Cell Host Microbe. 28:853–866.e5.

2020.

|

|

146

|

Hui DS, I Azhar E, Madani TA, Ntoumi F,

Kock R, Dar O, Ippolito G, Mchugh TD, Memish ZA, Drosten C, et al:

The continuing 2019-nCoV epidemic threat of novel coronaviruses to

global health-the latest 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak in Wuhan,

China. Int J Infect Dis. 91:264–266. 2020.

|

|

147

|

Gordon DE, Hiatt J, Bouhaddou M, Rezelj

VV, Ulferts S, Braberg H, Jureka AS, Obernier K, Guo JZ, Batra J,

et al: Comparative host-coronavirus protein interaction networks

reveal pan-viral disease mechanisms. Science. 370:eabe94032020.

|

|

148

|

Gordon DE, Jang GM, Bouhaddou M, Xu J,

Obernier K, White KM, O'Meara MJ, Rezelj VV, Guo JZ, Swaney DL, et

al: A SARS-CoV-2 protein interaction map reveals targets for drug

repurposing. Nature. 583:459–468. 2020.

|

|

149

|

Stukalov A, Girault V, Grass V, Karayel O,

Bergant V, Urban C, Haas DA, Huang Y, Oubraham L, Wang A, et al:

Multilevel proteomics reveals host perturbations by SARS-CoV-2 and

SARS-CoV. Nature. 594:246–252. 2021.

|

|

150

|

Li S, Ma F, Yokota T, Garcia G Jr, Palermo

A, Wang Y, Farrell C, Wang YC, Wu R, Zhou Z, et al: Metabolic

reprogramming and epigenetic changes of vital organs in

SARS-CoV-2-induced systemic toxicity. JCI insight.

6:e1450272021.

|

|

151

|

Bojkova D, Klann K, Koch B, Widera M,

Krause D, Ciesek S, Cinatl J and Münch C: Proteomics of

SARS-CoV-2-infected host cells reveals therapy targets. Nature.

583:469–472. 2020.

|

|

152

|

Miller B, Silverstein A, Flores M, Cao K,

Kumagai H, Mehta HH, Yen K, Kim SJ and Cohen P: Host mitochondrial

transcriptome response to SARS-CoV-2 in multiple cell models and

clinical samples. Sci Rep. 11:32021.

|

|

153

|

Medini H, Zirman A and Mishmar D: Immune

system cells from COVID-19 patients display compromised

mitochondrial-nuclear expression co-regulation and rewiring toward

glycolysis. iScience. 24:1034712021.

|

|

154

|

Codo AC, Davanzo GG, Monteiro LB, de Souza