Introduction

The emergence of systemic chronic inflammation is

significantly influenced by lifestyle, psychosocial elements and

environmental factors. This intricate interplay fosters a spectrum

of non-infectious inflammation-related maladies, including but not

limited to cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases, diabetes,

autoimmune disorders, chronic nephritis, chronic liver diseases,

and conditions affecting the osteoarticular and neurodegenerative

systems. These diseases collectively represent substantial

contributors to global morbidity and mortality rates. Addressing

the multifaceted determinants of chronic inflammation is imperative

for developing comprehensive strategies to mitigate the impact of

these prevalent and debilitating health conditions on a global

scale (1).

Studies have shown that pyroptosis is widely

involved in the occurrence and development of non-infectious

inflammation-related diseases and plays an important role (2). The sterile inflammatory response,

devoid of microbial infection, plays a crucial role in organ

development, tissue repair and host defense mechanisms.

Nonetheless, dysregulation of sterile inflammation can precipitate

various inflammatory diseases such as lung inflammation, type 2

diabetes and sterile liver diseases. Pyroptosis is a form of

programmed cell death that is distinct from apoptosis and necrosis.

It is an inflammatory form of cell death triggered by certain

cellular signals, particularly inflammasomes, in response to

infection or cellular stress (3).

During pyroptosis, the cell undergoes a series of morphological

changes, including cell swelling, membrane rupture, and release of

pro-inflammatory cytokines and intracellular contents. This process

is mediated by gasdermin proteins, which forms pores in the cell

membrane, leading to cell lysis and the release of inflammatory

molecules (3,4). Given the pivotal influence of

pyroptosis on orchestrating inflammation, there exists a hypothesis

postulating that pyroptosis may serve as a potential contributor in

several sterile inflammatory diseases.

Stem cell therapy, heralded as a groundbreaking

approach to treat diverse diseases and injuries, holds tremendous

promise for tissue repair and regeneration (5). Their therapeutic prowess lies in

their remarkable adaptability to specific tissue environments,

fostering healing through the generation of functional cells. This

adaptability becomes particularly crucial in scenarios where the

body's natural repair mechanisms prove insufficient, as observed in

degenerative diseases, injuries, or chronic disorders (6–8).

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), for example, exhibit

anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory properties, contributing to

tissue repair by reducing inflammation and promoting the

regeneration of damaged cells (9).

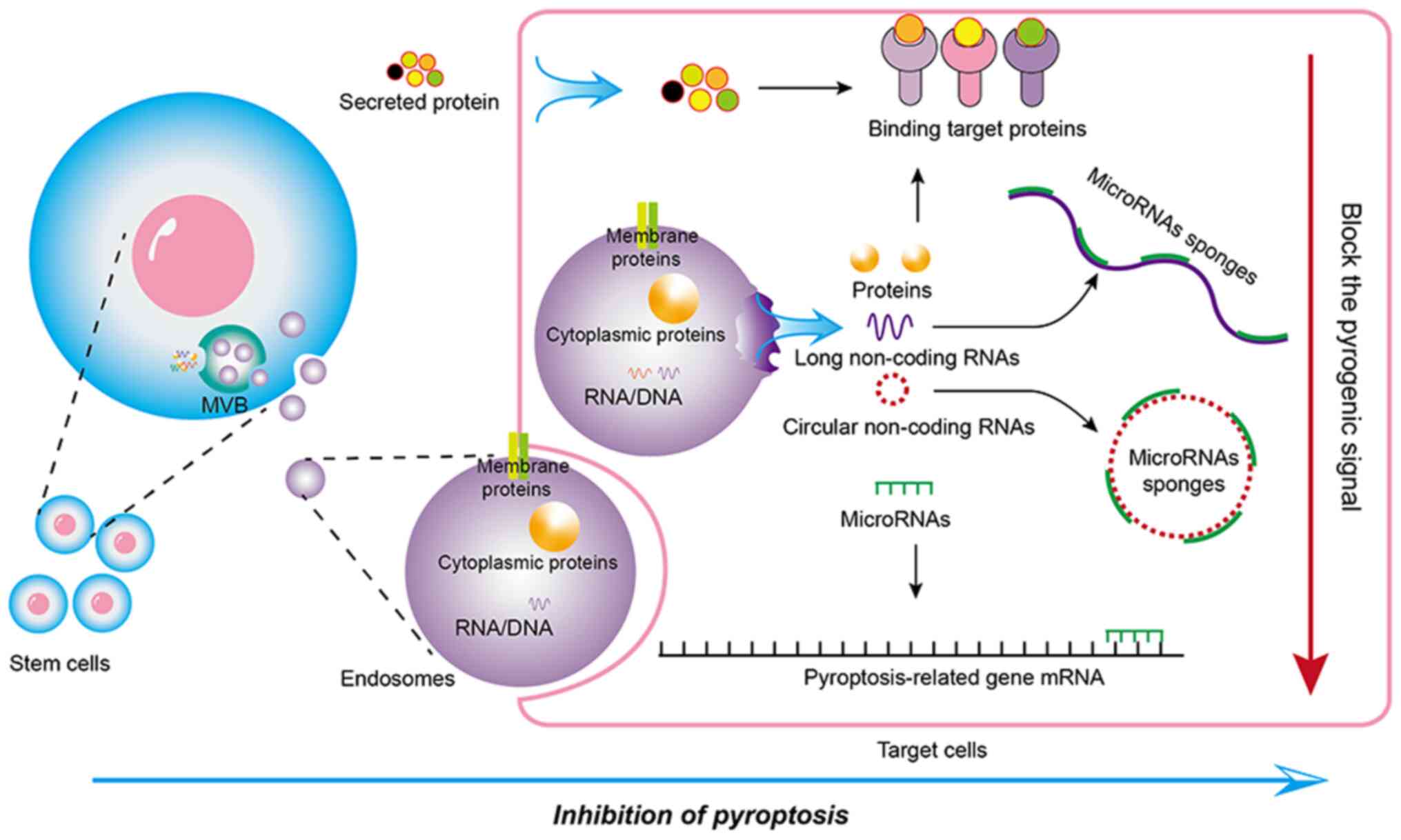

Previous studies have indicated that the ability of

stem cells to regulate pyroptosis has significant implications for

tissue repair and regenerative medicine (9,10).

Stem cells can secrete various factors, including anti-inflammatory

cytokines, growth factors and paracrine factors (Fig. 1), which can play a significant

role in reducing inflammation and promoting tissue repair (9,11).

These secreted factors carry a cargo of bioactive molecules, such

as microRNAs, proteins and lipids, which can directly or indirectly

target pyroptosis signaling pathways to influence neighboring cells

and modulate their behavior (12,13). Through intricate signaling

pathways, stem cells modulate pyroptosis to control the

inflammatory response and foster tissue regeneration (14). This regulatory function is crucial

in addressing injuries, degenerative diseases and other conditions

where pyroptosis may contribute to tissue damage (15).

Understanding the interplay between stem cells and

pyroptosis provides insights into innovative therapeutic

strategies, offering the potential for targeted interventions that

harness the regenerative capacities of stem cells to promote tissue

repair while mitigating excessive inflammatory responses. In the

present comprehensive review, it was presented how stem cells

regulate pyroptosis to promote tissue repair in various

diseases.

Canonical and non-canonical pathways of

pyroptosis

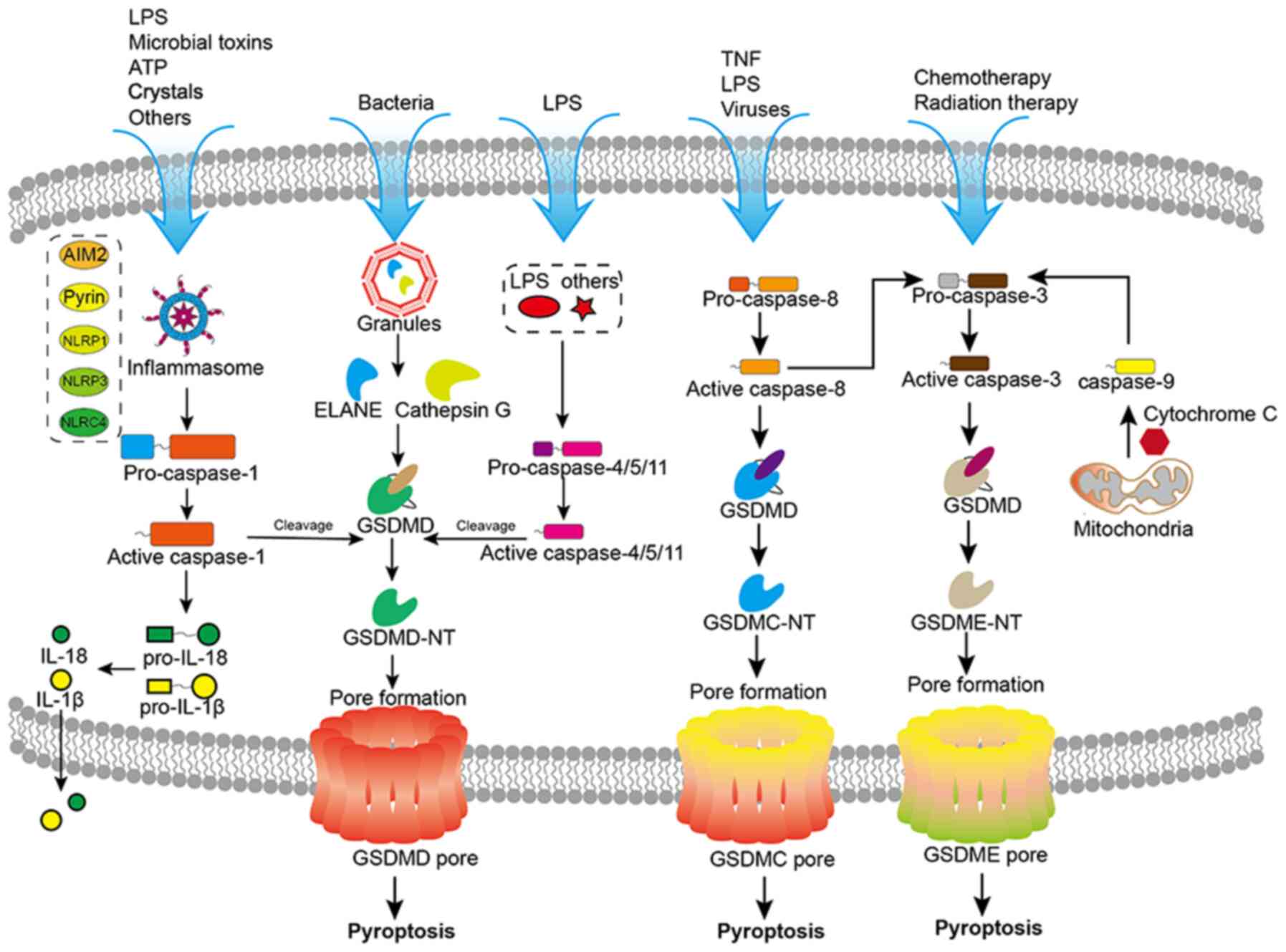

Stem cells influence pyroptosis by modulating the

pyroptosis signaling pathway, thereby further promoting tissue

repair or slowing the pathological process (16). Pyroptosis is activated through

distinct pathways, the canonical and non-canonical pathways

(Fig. 2) (17). Damage-associated molecular

patterns (DAMPs), which selectively bind to their complementary

membrane protein receptors, including Toll-like receptors (TLRs)

and nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptors,

collectively termed pattern recognition receptors (PRRs). Upon

binding to PRRs, DAMPs orchestrate the activation of nuclear factor

kappa B (NF-κB), culminating in the transcriptional upregulation of

numerous pro-inflammatory genes, among which are the essential

components of the inflammasome pathways (18). The assembly of the NOD-like

receptor family, pyrin domain-containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome

facilitates the self-cleavage of pro-caspase-1, transforming it

into its enzymatically active form, caspase-1 (19). Subsequently, active caspase-1

cleaves pro-interleukin into its biologically active counterparts,

IL-1β and IL-18 (20).

Simultaneously, caspase-1 also cleaves gasdermin D (GSDMD),

resulting in the formation of two fragments: GSDMD-N and GSDMD-C.

GSDMD-N subsequently assembles into pores within the plasma

membrane, initiating pyroptotic cell death and the release of IL-1β

and IL-18 to induce more inflammation (21).

In addition to the canonical pathway, emerging

evidence has demonstrated the involvement of caspase-4, caspase-5

and caspase-11 in pyroptosis, particularly in scenarios involving

conventional or unconventional inflammasome signaling (22–24). These caspases play a dual role in

initiating pyroptotic cell death. Firstly, caspase-4/5/11 can

directly cleave GSDMD (25). This

direct cleavage leads to the formation of GSDMD-N, which assembles

into membrane pores, resulting in pyroptotic cell death (25). Secondly, caspase-4/5/11 can also

stimulate the NLRP3 inflammasome/caspase-1 signaling pathway,

eventually leading to pyroptosis. In this context, caspase-4/5/11

serves as an upstream activator, triggering the assembly of the

NLRP3 inflammasome. This, in turn, leads to the activation of

caspase-1, which subsequently cleaves GSDMD, ultimately culminating

in the execution of pyroptotic cell death (26).

The modulation of pyroptosis by stem cells

for alleviating progression in degenerative diseases

Osteoarthritis (OA)

(OA) is a chronic joint disease marked by the

gradual degradation of articular cartilage (AC), along with

subchondral bone sclerosis, synovial hyperplasia, and the formation

of osteophytes (27). Emerging

evidence suggests that pyroptosis may play a crucial role in the

pathogenesis of OA (6). Recent

research has revealed that inhibiting pyroptosis in chondrocytes

can attenuate the development of OA (28). Excessive inflammation within

chondrocytes is a key factor contributing to chondrocyte survival

and is implicated in the progression of OA. In an adjuvant-induced

arthritis model, acid-sensitive ion channel 1a has been identified

as a mediator of chondrocyte pyroptosis, shedding light on the

underlying mechanisms of OA pathology (29). Furthermore, in knee OA,

fibroblast-like synoviocytes have been recognized as the main

effector cells responsible for synovial fibrosis. Pyroptosis in

these cells has been linked to NOD-like receptor family, pyrin

domain-containing 1 and NLRP3 inflammasomes, underscoring the

significance of pyroptosis in driving fibroblast-like synoviocyte

dysfunction in knee OA (30). An

increase in hypoxia-inducible factor-1α levels has been found to

exacerbate synovial fibrosis by promoting fibroblast-like

synoviocyte pyroptosis (31).

These studies elucidate the critical role of pyroptosis in the

pathophysiological processes of OA.

Recently, adipose-derived MSCs (adMSCs) have been

demonstrated to exert a protective effect by delaying the

development of rat OA. This safeguarding mechanism hinges on the

secretion of sTNFR1 by adMSCs, which possesses highly specific

neutralizing activity against tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α).

This inhibition of TNF-α serves to curtail chondrocyte pyroptosis,

a pivotal contributor to OA progression (32). In a similar vein, exosomes derived

from bone marrow MSCs (BMSC-Exos) have demonstrated the ability to

mitigate OA by delivering microRNA (miR)-326 to chondrocytes and

cartilage. Through this delivery, BMSC-Exos target HDAC3 and the

STAT1/NF-κB p65 axis, effectively inhibiting chondrocyte and

cartilage pyroptosis (15).

Likewise, extracellular vesicles derived from human umbilical cord

MSCs (hucMSC-EVs) have emerged as a promising avenue for

alleviating OA and maintaining chondrocyte homeostasis. A novel

therapeutic mechanism was revealed, centered around the pivotal

miR-223. This miR directly binds to the 3′-untranslated region of

NLRP3 mRNA, exerting profound anti-inflammatory and

cartilage-protective effects through hucMSC-EVs (33).

Intervertebral disc degeneration

(IVDD)

IVDD represents a chronic and degenerative disease

characterized by dysregulation of the catabolic and anabolic

processes within the extracellular matrix (ECM) and alterations in

the microenvironment of the intervertebral disc (IVD) (34,35). The healthy intervertebral disc is

a complex tissue composed of a soft inner nucleus pulposus (NP)

surrounded by the fibrocartilaginous ring annulus fibrosus and

cartilage endplates (36,37). However, during IVDD, there is an

aberrant expression of matrix metalloproteinases and a reduction in

collagen II secretion from NP cells (NPCs), which disrupts the

delicate balance of the ECM (38,39). Consequently, remodeling of the

IVDD microenvironment occurs, leading to the accumulation of

inflammatory factors and inducing NLRP3-mediated pyroptosis of NPCs

(40,41). This cascade of events initiates a

series of worsening reactions, contributing to the progression and

severity of the disease.

EVs, specifically exosomes, from stem cells play a

critical role in paracrine signaling, effectively protecting NPCs

from apoptosis, promoting ECM synthesis, and mitigating

inflammatory responses in intervertebral discs (42,43). A thermosensitive acellular ECM

hydrogel coupled with adMSCs exosomes has shown promise. This

approach helps maintain early IVDD microenvironment homeostasis and

ameliorates IVDD (44).

In several studies, the mechanism by which EVs from

stem cells inhibit pyroptosis of NPCs has been reported. In IVDD

patients, methyltransferase like 14 (METTL14) expression is

significantly elevated in NPCs (45). METTL14 stabilizes NLRP3 mRNA in a

manner dependent on insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 2

(46,47). Consequently, the increased NLRP3

levels lead to elevated production of IL-1β and IL-18, triggering

pyroptotic cell death in NPCs. However, hope lies in the

therapeutic potential of miRs derived from exosomes of different

stem cell sources. For instance, miR-26a-5p, found in hucMSCs

exosomes, directly degrades METTL14, effectively improving NP cell

viability and protecting them from pyroptosis (47). Similarly, MSCs-derived exosomal

miR-410 plays an essential role in counteracting pyroptosis by

directly binding to NLRP3 mRNA, thereby suppressing the NLRP3

pathway (9). Furthermore,

exosomal miR-302c, which originates from ESCs, exhibits

anti-pyroptotic properties by inhibiting NLRP3 and consequently

alleviating pyroptosis in NPCs (48).

Cartilage regeneration and

reconstruction

The regeneration and reconstruction of AC after a

defect, including OA and IVDD, pose significant challenges, owing

to its inherently restricted intrinsic reparative capabilities

(49,50). When AC sustains injury, the

afflicted tissue releases damage-associated DAMPs (51), subsequently provoking the

neighboring cells and circulating immune cells to secrete

pro-inflammatory chemokines (52). These inflammatory cytokines,

notably IL-1 and TNF-α, exert a profound inhibitory influence on

the proliferation and differentiation of MSCs and chondrocytes.

Notably, studies have documented that IL-1 and TNF-α impede the

differentiation of growth plate chondrocytes and suppress the

expression of chondrogenic-related genes in MSCs (53,54). The crux of addressing AC defects

lies in effectively promoting regeneration at the site and

controlling the inflammatory response (55).

In recent years, there has been a growing interest

in employing an endogenous regenerative approach that mobilizes

resident MSCs to the sites of injury-a promising alternative

strategy. Research has unveiled a bioactive multifunctional

scaffold designed with the aptamer Apt19S as a mediator for the

targeted recruitment of MSCs. This scaffold not only enhances

cellular chondrogenesis but also exerts effective regulation over

the inflammatory response through the incorporation of

Mg2+ (56). Another

noteworthy study has reported that the incorporation of magnesium

hydroxide nanoparticles within a poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid)

scaffold enhances chondrogenesis by inducing the chondrogenic

differentiation of human BMSCs. Furthermore, it diminishes

pyroptosis during the early stages of chondrogenic differentiation

and curtails the release of inflammatory cytokines (57).

Stem cell-based transplantation holds immense

promise as a therapeutic approach for IVDD (58). MSCs transplantation, in

particular, has gained traction as a representative cell therapy

for IVDD (59). However, the

intra-discal injection of ‘naked’ MSCs faces challenges due to the

harsh IVDD microenvironment, resulting in poor survival rates and

altered activity (60,61). To address this, a novel strategy

involving the use of embryo-derived long-term expandable NP

progenitor cells (NPPCs) and esterase-responsive ibuprofen

nano-micelles (PEG-PIB) was devised for synergistic

transplantation. The PEG-PIB micelles were endocytosed to

pre-modify the NPPCs, rendering them adaptable to the harsh IVDD

microenvironment by inhibiting pyroptosis of NPPCs through the

COX2/NF-κB/Caspase-1 signaling pathway. This synergistic

transplantation approach demonstrated effective functional

recovery, histological regeneration, and inhibition of pyroptosis

during the process of IVDD regeneration (62).

Pyroptosis plays a pivotal role in degenerative

diseases, with a specific emphasis on its impact on OA and IVDD

(41,63). Stem cells exhibit dual

functionality in mitigating degenerative diseases. Firstly, they

impede pyroptosis at lesion sites through paracrine pathways,

thereby decelerating the pathological progression. Secondly, the

hostile microenvironment at lesion sites induces pyroptosis in

transplanted stem cells. Several innovative designs are required to

inhibit stem cell pyroptosis, enhancing the efficacy of lesion

repair.

Stem cell-mediated modulation of pyroptosis

for tissue repair in ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury

Myocardial I/R injury

Myocardial I/R injury is a complex pathological

process that occurs when blood flow to the heart muscle

(myocardium) is temporarily reduced or interrupted (ischemia),

followed by the restoration of blood flow (reperfusion) (64). This intricate phenomenon is

observed in various cardiac conditions, such as acute myocardial

infarction (heart attack) and coronary artery bypass grafting

(65).

During myocardial I/R, the activation of

inflammasomes and the subsequent release of pro-inflammatory

cytokines can trigger pyroptosis, a highly regulated form of cell

death (66). This cascade of

events contributes to the progression of tissue damage and

inflammation, exacerbating the consequences of myocardial I/R

injury. Understanding the mechanisms underlying pyroptosis in the

context of myocardial I/R injury is of utmost importance for

devising novel therapeutic interventions and mitigating the impact

of cardiovascular diseases (67).

Recent evidence highlights the significant role of

exosomes derived from MSCs in conferring protective effects against

myocardial I/R injury by inhibiting myocardial pyroptosis (7). These exosomes act as carriers of

endogenous molecules, including non-coding RNA, which play a

crucial role in suppressing pyroptosis following I/R (68). Specifically, exosomal miR-320b

targets NLRP3 (69), miR-100-5p

targets FOXO3 (16), and

miR-182-5p targets GSDMD (7),

leading to downregulation of these target proteins and subsequent

inhibition of pyroptosis. Additionally, the lncRNA KLF3-AS1,

competes with miR-138-5p to regulate Sirt1 expression, contributing

to the attenuation of pyroptosis (70). Another lncRNA, XIST, serves as a

competing endogenous RNA of miR-214-3p, leading to upregulation of

its target gene Arl2, which in turn attenuates myocardial

pyroptosis (71). Moreover,

MSC-derived exosomes exhibit their protective role in preventing

ischemic injury through the release of circHIPK3, a circular

non-coding RNA. CircHIPK3 downregulates miR-421, resulting in

increased expression of FOXO3a, which effectively inhibits

pyroptosis and the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as

IL-1β and IL-18 (72).

Neuronal I/R injury

Cerebral ischemic stroke stands as the most

prevalent cause of death and disability among central nervous

system (CNS) diseases (73). This

ischemic insult is often accompanied by a robust inflammatory

response. In the face of cerebral I/R injury, various forms of

programmed cell death, including apoptosis and pyroptosis, emerge

as prominent contributors to the ensuing tissue damage (74). Microglia, as the resident immune

cells in the central nervous system, play a pivotal role in the

initiation and progression of I/R injury (75). Notably, prior investigations have

shown that inhibiting microglial pyroptosis in neonatal mice

subjected to cerebral I/R promotes neuronal survival and ultimately

ameliorates brain injury (76).

In the realm of neuroprotection, a distinct class of

MSCs called olfactory mucosa MSCs demonstrate their capacity to

confer neuroprotection by mitigating apoptosis and pyroptosis in

microglial cells, employing an oxygen-glucose

deprivation/reperfusion model that closely mimics I/R conditions

(77). Moreover, emerging

research highlights the significance of MSC-derived exosomes in

inhibiting microglial pyroptosis. These exosomes facilitate

FOXO3a-dependent mitophagy, a cellular process responsible for

clearing damaged mitochondria, thereby mediating neuroprotection

(78). Additionally, MSC-derived

exosomes modulate microglial polarization, shifting them from an M1

phenotype (pro-inflammatory) to an M2 phenotype

(anti-inflammatory), further contributing to the amelioration of

cerebral I/R injury (79).

Another noteworthy finding pertains to BMSCs-derived exosomal

miR193b-5p, which plays a pivotal role in reducing microglia

pyroptosis post-ischemic stroke. The miR targets the absent in

melanoma 2 (AIM2) pathway, effectively suppressing AIM2-mediated

pyroptosis (12).

A recent study suggested that retinal I/R injury may

initiate pyroptosis in retinal neurons (80). Throughout retinal I/R injury,

various cellular processes, including oxidative stress,

mitochondrial dysfunction and activation of inflammasomes,

contribute to the induction of pyroptosis in retinal neurons.

Interventions targeting pyroptosis could prove to be an effective

strategy in preventing I/R-induced retinal damage and subsequent

visual impairment (81). The

neuroprotective effects of intravitreal injection of MSCs and

MSC-conditioned medium in rats during retinal ischemia are

noteworthy (82,83). These effects are primarily

mediated by EVs (84). While both

MSCs and MSC-derived EVs have demonstrated neuroprotective effects

following retinal I/R injury, direct evidence confirming this

protective effect's association with the modulation of pyroptosis

is currently lacking.

Cardiac and cerebral injuries after

cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR)

After CPR, cardiac and cerebral injuries often lead

to unfavorable outcomes in cardiac arrest (CA) victims (85). The pathogenesis of these injuries

may involve cell pyroptosis and ferroptosis. However, promisingly,

MSCs have also emerged as a potential therapeutic strategy for

providing cardiac and cerebral protection for I/R injury. MSCs have

been identified to effectively reduce post-resuscitation cardiac

and cerebral pyroptosis and ferroptosis, offering hope for

improving the prognosis and overall outcome of CA patients

(10). Although the mechanism by

which MSCs reduce pyroptosis in post-resuscitation cardiac and

brain cells is unclear, there is evidence that MSCs downregulate

the level of M1 macrophages and upregulate the level of M2

macrophages after CA (86). Given

the link between pyroptosis and inflammation, the modulation of

post-resuscitation cardiac and cerebral pyroptosis by MSCs may

involve the regulation of the inflammatory microenvironment.

Lung I/R injury (LIRI)

LIRI represents a pathological phenomenon triggered

by various clinical conditions, including lung transplantation,

hemorrhagic shock and pulmonary embolism (87). A key contributing factor to LIRI

is the heightened release of IL-1β and IL-6, leading to pyroptosis

in lung epithelial cells (88).

Remarkably, treatment with human BMSCs has shown significant

efficacy in alleviating hypoxia-induced pulmonary epithelial

injury, offering promise for LIRI intervention (89). Recent investigations have

identified a crucial mechanism by which BMSC-derived exosomes exert

their protective effects against LIRI. Specifically, the exosomal

miR-202-5p plays a central role in repressing pulmonary epithelial

pyroptosis, thereby inhibiting the progression of LIRI (90). The targeted molecule of miR-202-5p

is CMPK2, a mitochondrial nucleotide monophosphate kinase known for

its regulatory role in macrophage activation and inflammatory

responses (91).

Hepatic I/R injury (HIRI)

HIRI is a significant contributor to liver injury

and failure following liver surgery. This condition is

characterized by massive cell death, severe inflammation and

oxidative stress (92). adMSCs

and their exosomes have been demonstrated to reduce pyroptosis in

the injured liver and promote the expression of factors associated

with liver regeneration. Additionally, they can inhibit the NF-κB

pathway while activating the Wnt/β-catenin pathway, both of which

play crucial roles in inflammation and tissue repair (93).

These elucidate the crucial role of pyroptosis in

I/R injuries, particularly focusing on cardiac and cerebral

injuries, lung I/R injury, and hepatic I/R injury (85,87,92,94). In summary, stem cell-based

therapies, particularly involving MSCs and their exosomes, showcase

promising outcomes in alleviating I/R injuries.

Stem cell-mediated modulation of pyroptosis

for tissue repair in drugs-induced injury

Doxorubicin (Dox)-induced

cardiotoxicity

Dox is a potent antineoplastic agent widely used for

cancer treatment. However, its use can lead to cardiotoxicity and

muscle toxicity due to the escalation of oxidative stress and

inflammation, ultimately culminating in pyroptosis. Encouragingly,

the protective effects of exosomes derived from ESCs on Dox-induced

myocardial pyroptosis have been previously demonstrated (95). At a mechanistic level, Dox

treatment significantly upregulates the expression of inflammasome

markers, such as TLR4 and NOD-like receptor protein 3 (NLRP3), as

well as pyroptotic markers, including caspase-1, IL-1β and IL-18

(96). Additionally, Dox

treatment leads to an increase in cell signaling proteins, such as

myeloid differentiation primary response 88 (MyD88), phosphorylated

(p-)P38, and p-JUN N-terminal kinase, which play pivotal roles in

inflammation and cell signaling (96,97). Moreover, the treatment with Dox

promotes the pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages and the secretion of

TNF-α cytokine, further contributing to the pro-inflammatory

environment and pyroptotic response (96,97).

However, the adverse effects induced by Dox,

including pyroptosis, inflammation and cell signaling protein

expression, are effectively counteracted by the application of

ESCs-exosomes or ESCs themselves (97). These protective interventions

demonstrate promising potential in mitigating Dox-induced cardiac

and muscle damage by attenuating the pyroptotic response and

dampening the inflammatory signaling (96,98).

Drugs-induced liver injury (DILI)

DILI involves liver damage resulting from the use of

certain medications. Some drugs may trigger the activation of

inflammasomes, leading to the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines

and initiating pyroptotic pathways in liver cells. This process can

exacerbate liver damage and contribute to the progression of

DILI.

Stem cell-based therapy has exhibited promise in

treating liver diseases due to the regenerative and paracrine

secretion properties of stem cells (99). Notably, MSCs have

anti-inflammatory effects and have been investigated for their

therapeutic potential in various liver diseases. For instance, the

injection of interleukin-10 or transplantation of MSCs has been

found to ameliorate liver injury induced by D-galactosamine, as

evidenced by reduced levels of liver injury markers, inflammatory

cytokines and NH3 (100).

Moreover, when adMSCs are preincubated with green tea theanine,

they demonstrate an enhanced therapeutic effect in rats with liver

injury induced by N-nitrosodiethylamine, significantly suppressing

pyroptosis markers, such as caspase-1 and IL-1β (101).

Various drugs can activate inflammasomes, triggering

the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines and initiating pyroptotic

pathways in affected cells. This process exacerbates tissue damage

and contributes to the progression of drug-induced injuries. These

findings highlight the potential of stem cell-based interventions

in mitigating drug-induced injuries by suppressing pyroptosis.

Stem cell-mediated modulation of pyroptosis

for tissue repair in diabetes complications

Diabetes is a chronic metabolic disorder

characterized by elevated blood sugar levels, which can result from

inadequate insulin production or ineffective insulin utilization.

This condition can lead to various complications, including

cardiovascular diseases, kidney damage, nerve damage, and issues

with the skin and eyes (102).

Diabetic skin wounds

In diabetes, skin wounds become a major medical

concern. High blood sugar levels and impaired wound healing

mechanisms can lead to chronic wounds that heal slowly and are

prone to infections (103).

Pyroptosis, a type of cell death triggered by inflammation, can

exacerbate the inflammatory response at the wound site and hinder

tissue repair, further delaying the healing process (104). Hair follicle MSCs (hfMSCs) have

shown promise in promoting skin wound healing in diabetic mice.

Exosomes from hfMSCs containing long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) H19

have been found to enhance the proliferation and migration of HaCaT

cells (a human keratinocyte cell line) and inhibit pyroptosis by

reversing the stimulation of the NLRP3 inflammasome (105). Moreover, the use of

BMSCs-conditioned medium (BMSC-CM) has revealed positive effects in

diabetic foot ulcers. MSC-CM accelerates wound closure, promotes

cell proliferation and angiogenesis (formation of new blood

vessels), enhances cell autophagy (a process that supports cell

survival and renewal), and reduces cell pyroptosis. By modulating

these cellular processes, MSC-CM facilitates a more efficient wound

healing process in diabetic foot ulcers (13).

In regenerative therapy, providing a conducive

microenvironment is crucial to increasing the survival of

transplanted stem cells. However, hyperglycemia can lead to stem

cell death, hindering the effectiveness of stem cell therapy. A

previous study reported that hyperglycemia-induced oxidative stress

contributes to apoptosis and pyroptosis in human cardiac stem cells

(106). Downregulation of NLRP3

in adipose-derived stem cells has been found to improve the effects

of stem cell therapy under hyperglycemic conditions by suppressing

pyroptosis (107).

Diabetic kidney disease (DKD)

DKD is a serious complication of diabetes

characterized by kidney damage and impaired function resulting from

prolonged high blood sugar levels. It stands as a leading cause of

chronic kidney disease and kidney failure worldwide (108). Promisingly, research has

revealed that BMSCs-derived exosomal miR-30e-5p can effectively

inhibit caspase-1-mediated pyroptosis in HK-2 cells induced by high

glucose. The discovery of this regulatory mechanism opens up new

possibilities for treating DKD (109). By attenuating pyroptosis, which

is known to contribute to kidney damage and dysfunction,

BMSCs-derived exosomal miR-30e-5p offers a promising new strategy

for the management and treatment of diabetic kidney disease.

Diabetes poses various complications, including skin

wounds with impaired healing mechanisms. Pyroptosis, an

inflammation-triggered cell death, exacerbates inflammatory

responses in diabetic skin wounds. In conclusion, stem cells,

including hfMSCs and BMSCs, along with their secreted factors and

exosomes, play pivotal roles in mitigating these complications by

inhibiting pyroptosis.

Stem cell-mediated modulation of pyroptosis

for tissue repair in inflammation-related diseases

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)

IBD comprises chronic inflammatory disorders

primarily affecting the gastrointestinal tract, including Crohn's

disease and ulcerative colitis (110). Pyroptosis plays a significant

role in contributing to the pathogenesis of IBD (111). In the context of IBD, immune

cells in the gut, such as macrophages and epithelial cells, undergo

pyroptosis, releasing pro-inflammatory molecules that lead to

intestinal inflammation and tissue damage. This process exacerbates

the symptoms of IBD, including abdominal pain, diarrhea and ulcers,

emphasizing the importance of understanding and targeting

pyroptosis as a potential therapeutic approach for managing IBD

(112).

hucMSCs-derived exosomes have emerged as novel

cell-free therapeutic agents for IBD. These exosomes have

demonstrated the ability to inhibit the activation of macrophage

NLRP3 inflammasomes, thereby suppressing the secretion of IL-18,

IL-1β and cleaved caspase-1, resulting in reduced cell pyroptosis.

Furthermore, miR-378a-5p, highly expressed in hucMSCs-derived

exosomes, plays a vital role in promoting colitis repair (113). Additionally, miR-203a-3p.2 in

hucMSC-derived exosomes, acts as an effective mediator in the

interaction with caspase-4 in THP-1 macrophage pyroptosis (114).

Lung injury

Acute lung injury (ALI) and its more severe form,

acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), are characterized by

widespread inflammation and injury to the lungs, often leading to

respiratory failure. Pyroptosis is implicated in various

factors-induced ALI/ARDS, such as lipopolysaccharide and sepsis

(115). Emerging evidence

suggests that pyroptosis is involved in the pathogenesis of

ALI/ARDS, contributing to the amplification of the inflammatory

response in the lungs (116).

Influenza A virus infection triggers an exaggerated immune response

in the host, leading to caspase-3-GSDME-mediated pyroptosis of lung

alveolar epithelial cells. This process contributes to the onset of

a cytokine storm, ultimately resulting in ALI or ARDS. Notably,

BMSCs exhibit a therapeutic effect by mitigating ALI through the

inhibition of caspase-3-GSDME-mediated pyroptosis in lung alveolar

epithelial cells (117).

Furthermore, MSCs-derived exosomes play a crucial role in

inhibiting pyroptosis. This inhibition is achieved through miRNAs

targeting the caspase-1-mediated pathway and proteins with

immunoregulatory functions, thereby suppressing alveolar macrophage

pyroptosis and alleviating ALI (118). Specifically, exosomes derived

from BMSCs act as carriers for delivering miR-125b-5p, which

downregulates STAT3. This, in turn, inhibits macrophage pyroptosis,

demonstrating a potential therapeutic avenue for alleviating

sepsis-associated ALI (119).

Besides, cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) has been widely used to

support the heart and lung during cardiac surgery. It has been

reported that BMSCs-derived exosomes ameliorate macrophage

infiltration and oxidative stress, and downregulate expression of

pyroptosis-related proteins in CPB-ALI model, as well as promote

YAP interaction with β-catenin and regulate its transcription

activity (120).

Silicosis is induced by prolonged inhalation of

silica particles, resulting in lung cell injury and disruptions to

the intracellular environment. It is characterized by collagen

deposition and the development of pulmonary fibrosis (121). Pyroptosis and apoptosis play

vital roles in the pathogenesis of silicosis (122). Recently, it has been revealed

that BMSCs possess the ability to mitigate silica-induced pulmonary

fibrosis by inhibiting both apoptosis and pyroptosis (123).

Kidney injury

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is characterized by a

sudden and rapid deterioration in kidney function, leading to an

impaired ability to filter waste and fluid from the blood (124). The involvement of pyroptosis has

been recognized in regulating homeostasis in kidney tissues, thus

playing a significant role in the development of AKI (125). It has been reported that EVs

released by BMSCs might carry a specific miR, miR-223-3p, to

mitigate inflammation and pyroptosis induced by AKI through the

modulation of the HDAC2/SNRK axis (126). Furthermore, another study has

demonstrated the beneficial effects of BMSCs in sepsis-induced AKI.

These stem cells promote mitophagy and inhibit apoptosis and

pyroptosis of renal tubular epithelial cells within kidney tissues.

This therapeutic action is attributed to the upregulation of

SIRT1/Parkin, which plays a crucial role in protecting against AKI

in the context of sepsis (127).

Traumatic injury

The CNS is particularly vulnerable to external

mechanical damage. Traumatic brain injury (TBI) can result from

direct impacts or blows to the head, often caused by factors such

as motor vehicle accidents, crush injuries, or assaults (128). The pathophysiology of TBI

involves both primary and secondary injury mechanisms. The primary

injury occurs at the time of impact and involves mechanical damage

to brain tissue. Secondary injury mechanisms follow the primary

injury and involve processes such as inflammation, oxidative stress

and excitotoxicity. In recent developments, exosomes derived from

hucMSCs have shown significant potential in suppressing neuron cell

apoptosis, pyroptosis and ferroptosis in cases of TBI. This

therapeutic effect is mediated through the PINK1/Parkin pathway,

facilitating mitophagy, a process that removes damaged mitochondria

and aids in cellular recovery (129).

Spinal cord injury (SCI) involves damage to the

spinal cord, leading to functional impairment. The trauma induces a

cascade of events, activating pyroptosis-related molecules and

triggering an inflammatory response. Excessive pyroptosis

exacerbates secondary injury processes, contributing to tissue

damage and neurological deficits. Inhibiting the

pyroptosis-regulated cell death and inflammasome components is a

promising therapeutic approach for the treatment of SCI (130). BMSCs have been previously

reported to exhibit a promising therapeutic effect in treating SCI

by mitigating inflammasome-related pyroptosis. The underlying

mechanism involves BMSCs' exosome-derived circ_003564, a circular

RNA, which has been identified to decrease the expression of

inflammasome-related pyroptosis markers, including cleaved

caspase-1, GSDMD, NLRP3, IL-1β and IL-18 in neurons (14). This reduction in pyroptosis

markers indicates a potential protective effect of BMSC-derived

exosomal circ_003564 on neurons in the context of SCI.

Intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH)

Another cerebrovascular disease with high morbidity

and mortality is ICH, often resulting from the rupture of blood

vessels (131). Hemoglobin and

its breakdown products released from erythrocytes during hemorrhage

can activate inflammasomes, initiating the pyroptotic pathway.

Pyroptosis is strongly related to neuroinflammation, which plays a

crucial role in the pathophysiological processes of secondary brain

injury after ICH. Pyroptosis causes the releases of inflammatory

cytokines and DAMPs can exacerbate neuronal injury and affect

surrounding tissue. It has been reported that stem cell-derived

exosomes have demonstrated a protective effect in ICH by inhibiting

pyroptosis. Specifically, exosomal miR-23b from BMSCs exhibits

antioxidant properties through the inhibition of PTEN, thereby

alleviating NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated pyroptosis. This process

promotes neurologic function recovery in rats with ICH (132).

Extensive research demonstrates their effectiveness

in treating diverse inflammation-related diseases by targeting

signals associated with inflammation and pyroptosis (Table I). There is a basis for optimism

that stem cells and the factors they release may exert favorable

effects in various other inflammatory diseases.

| Table I.Stem cells inhibit pyroptosis in

inflammation-related diseases. |

Table I.

Stem cells inhibit pyroptosis in

inflammation-related diseases.

| Disease types | Classification of

stem cells | Targeted cells | Pyroptotic

signaling molecules | Effectors | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Osteoarthritis | adMSCs | Chondrocyte | TNF-α | sTNFR1 | (32) |

|

| BMSCs | Chondrocyte | HDAC3 | miR-326

(exosomes) | (15) |

|

| hucMSCs | Chondrocyte | NLRP3 | miR-223

(exosomes) | (33) |

| Intervertebral | MSCs | Nucleus

pulposus | METTL14 | miR-26a-5p

(exosomes) | (47) |

| disc

degeneration |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| hucMSCs | Nucleus

pulposus | NLRP3 | miR-410

(exosomes) | (9) |

|

| ESCs | Nucleus

pulposus | NLRP3 | miR-302c

(exosomes) | (48) |

| Myocardial

ischemia/ | MSCs | Myocardial

cell | NLRP3 | miR-320b

(exosomes) | (69) |

| reperfusion

injury |

| Myocardial

cell | GSDMD | miR-182-5p

(exosomes) | (7) |

|

| hucMSCs | Myocardial

cell | FOXO3 | miR-100-5p

(exosomes) | (16) |

|

|

| Myocardial

cell | FOXO3a | Circular non-coding

RNA, | (72) |

|

|

|

|

| circhipk3

(exosomes) |

|

|

| hMSCs | Myocardial

cell | Sirt1 | Long non-coding

RNA, | (70) |

|

|

|

|

| KLF3-AS1

(exosomes) |

|

|

| adMSCs | Myocardial

cell | Arl2 | Long non-coding

RNA, | (71) |

|

|

|

|

| XIST

(exosomes) |

|

| Cerebral

ischemic | omMSCs | Microglial

cells |

| Exosomes | (77,78) |

| stroke | BMSCs | PC12 cells | AIM2 | miR193b-5p

(exosomes) | (12) |

| Lung ischemia- | BMSCs | Pulmonary | CMPK2 | miR-202-5p

(exosomes) | (90) |

| reperfusion

injury |

| epithelial

cells |

|

|

|

| Hepatic

ischemia- | adMSCs | Hepatocyte | NF-κB pathway | Exosomes | (93) |

| reperfusion

injury |

|

| and

Wnt/β-catenin |

|

|

|

|

|

|

pathwaya |

|

|

|

Doxorubicin-induced | ESCs | Myocardial

cell |

| Exosomes | (97) |

| cardiotoxicity |

|

|

|

|

|

| Drugs-induced

liver | ADSCs | Hepatocyte | Caspase-1 and |

| (101) |

| injury |

|

| IL-1βa |

|

|

| Diabetic skin

wounds | hfMSCs | HaCaT cells | NLRP3 | Long non-coding

RNA, | (105) |

|

|

|

|

| H19 (exosomes) |

|

|

| BMSCs |

|

| Bone

marrow-derived | (13) |

|

|

|

|

| mesenchymal

stem |

|

|

|

|

|

| cell-conditioned

medium |

|

| Diabetic

kidney | BMSCs | Renal proximal | ELAVL1 | miR-30e-5p

(exosomes) | (109) |

| disease |

| tubular cells |

|

|

|

| Inflammatory bowel

disease | hucMSCs | THP-1 cells and

mouse peritoneal macrophages | NLRP3 | miR-378a-5p

(exosomes) | (113) |

|

|

| Macrophage | Caspase-4 | miR-203a-3p.2

(exosomes) | (114) |

| Acute lung

injury | BMSCs | Lung cells | YAP/β-catenin

axisa | Exosomes | (120) |

| Silicosis | BMSCs | Lung cells |

|

| (123) |

| Acute kidney

injury | BMSCs | HK-2 cells | HDAC2/SNRK | miR-223-3p

(extracellular | (126) |

|

|

|

|

| vesicles) |

|

|

|

| Renal tubular |

SIRT1/Parkina |

| (127) |

|

|

| epithelial

cells |

|

|

|

| Traumatic brain

injury | hucMSCs | Neuron | PINK1/Parkin | Exosomes | (129) |

| Spinal cord

injury | BMSCs | Neuron |

pathwaya

caspase-1, | Circular non-coding

RNA, |

|

|

|

|

| GSDMD, NLRP3, | circ_003564

(exosomes) | (14) |

|

|

|

| IL-1β and

IL-18a |

|

|

| Intracerebral | BMSCs | Microglial

cells | PTEN | miR-23b

(exosomes) | (132) |

| hemorrhage |

|

|

|

|

|

Prospect

Stem cells are unique cells with the ability to

differentiate into various cell types and self-renew, making them

an attractive option for repairing damaged or diseased tissues

(133). However, its clinical

application also faces numerous challenges and risks (134). On the one hand, the potential

for tumorigenesis, particularly teratoma formation, is a

significant concern associated with the clinical use of ESCs

(135). Teratomas are tumors

that contain a mixture of differentiated tissues from all three

germ layers (ectoderm, mesoderm and endoderm). They can be benign,

but they represent a significant risk associated with the

transplantation of undifferentiated pluripotent cells, including

ESCs (136). While ESC therapy

has immense potential, the risk of teratoma formation underscores

the importance of rigorous safety and quality control measures in

the development and application of these therapies. Researchers and

clinicians are actively working to address these challenges to make

ESC-based treatments safer and more effective (137). On the other hand, autologous

transplantation offers the advantage of using a patient's own

cells, thereby eliminating the risk of immune rejection, but

allogeneic stem cell treatments involve donor cells and carry a

distinct set of potential risks and complications (138). These must be carefully

considered due to the inherent differences between the donor and

recipient, which include factors such as genetic disparities,

tissue compatibility and immunological variations. Overall,

ensuring the safety and efficacy of stem cell treatments, as well

as addressing issues related to immune rejection and ethical

considerations, remain important areas of research (139).

Exosomes derived from stem cells in therapy is their

potential to overcome the limitations associated with stem cell

transplantation, such as potential immune rejection and ethical

concerns. Exosomes can be delivered directly to the target site,

and they have a lower risk of immune response compared with whole

cells. While exosomes hold great promise, further research is

needed to optimize their isolation, characterization and

therapeutic application (8).

Additionally, understanding the precise mechanisms of

exosome-mediated effects will help enhance their efficacy in stem

cell-based therapy and pave the way for more effective regenerative

treatments.

The protective mechanisms employed by stem cells are

remarkably complex, and current understanding only provides a

glimpse of their full potential. In addition to inhibiting

apoptosis, stem cells have been found to suppress pyroptosis and

regulate autophagy (140,141).

While they hold great promise in therapeutic applications, stem

cell therapy is still in its nascent stages and requires extensive

research and clinical practice before it can be fully realized in

clinical settings. Creating an environment that maximizes stem cell

protection and harnessing their potential for therapeutic benefits

necessitate a rigorous and comprehensive approach to furthering

understanding and advancing stem cell-based treatments.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the National Natural Science

Fund (grant no. 82002059), the Hunan Provincial Health Commission

Scientific Research Project (grant nos. D202304108322 and

202105011186), the Hunan Innovation Guidance Project for Clinical

Medical Technology (grant no. 2021SK51826), the Hunan Provincial

Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 2023JJ30542) and the

Hunan Graduate Student Research and Innovation Project (grant no.

CX20221008).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

YiWe and LL conceptualized the study, wrote the

original draft, conducted formal analysis, and wrote, reviewed and

edited the manuscript. YiWa, YC, ZL and CH reviewed and edited the

manuscript. YaW developed methodology. CJ contributed to study

conceptualization, writing the original draft, and writing,

reviewing and editing the manuscript. ZW and JL supervised the

study. All authors have read and approved the final version of the

manuscript. Data authentication is not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

AC

|

articular cartilage

|

|

MSCs

|

mesenchymal stem cells

|

|

adMSCs

|

adipose-derived MSCs

|

|

AIM2

|

absent in melanoma 2

|

|

AKI

|

acute kidney injury

|

|

ALI

|

acute lung injury

|

|

BMSCs

|

bone marrow MSCs

|

|

BMSC-CM

|

BMSCs-conditioned medium

|

|

BMSC-Exos

|

exosomes derived from BMSCs

|

|

CA

|

cardiac arrest

|

|

CNS

|

central nervous system

|

|

CPB

|

cardiopulmonary bypass

|

|

CPR

|

cardiopulmonary resuscitation

|

|

DAMPs

|

damage-associated molecular

patterns

|

|

DKD

|

diabetic kidney disease

|

|

DILI

|

drug-induced liver injury

|

|

Dox

|

doxorubicin

|

|

ECM

|

extracellular matrix

|

|

EVs

|

extracellular vesicles

|

|

GSDMD

|

gasdermin D

|

|

hfMSCs

|

hair follicle MSCs

|

|

I/R

|

ischemia/reperfusion;

|

References

|

1

|

Furman D, Campisi J, Verdin E,

Carrera-Bastos P, Targ S, Franceschi C, Ferrucci L, Gilroy DW,

Fasano A, Miller GW, et al: Chronic inflammation in the etiology of

disease across the life span. Nat Med. 25:1822–1832. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Li T, Zheng G, Li B and Tang L:

Pyroptosis: A promising therapeutic target for noninfectious

diseases. Cell Proliferat. 54:e131372021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Yu P, Zhang X, Liu N, Tang L, Peng C and

Chen X: Pyroptosis: Mechanisms and diseases. Signal Transduct Tar.

6:1282021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Kovacs SB and Miao EA: Gasdermins:

Effectors of pyroptosis. Trends Cell Biol. 27:673–684. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Dekoninck S and Blanpain C: Stem cell

dynamics, migration and plasticity during wound healing. Nat Cell

Biol. 21:18–24. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Mapp PI and Walsh DA: Mechanisms and

targets of angiogenesis and nerve growth in osteoarthritis. Nat Rev

Rheumatol. 8:390–398. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Yue R, Lu S, Luo Y, Zeng J, Liang H, Qin

D, Wang X, Wang T, Pu J and Hu H: Mesenchymal stem cell-derived

exosomal microRNA-182-5p alleviates myocardial ischemia/reperfusion

injury by targeting GSDMD in mice. Cell Death Discov. 8:2022022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Hade MD, Suire CN and Suo Z: Mesenchymal

stem cell-derived exosomes: Applications in regenerative medicine.

Cells-Basel. 10:19592021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Zhang J, Zhang J, Zhang Y, Liu W, Ni W,

Huang X, Yuan J, Zhao B, Xiao H and Xue F: Mesenchymal stem

cells-derived exosomes ameliorate intervertebral disc degeneration

through inhibiting pyroptosis. J Cell Mol Med. 24:11742–11754.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Xu J and Zhang M, Liu F, Shi L, Jiang X,

Chen C, Wang J, Diao M, Khan ZU and Zhang M: Mesenchymal stem cells

alleviate post-resuscitation cardiac and cerebral injuries by

inhibiting cell pyroptosis and ferroptosis in a swine model of

cardiac arrest. Front Pharmacol. 12:7938292021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Li K, Yan G, Huang H, Zheng M, Ma K, Cui

X, Lu D, Zheng L, Zhu B, Cheng J and Zhao J: Anti-inflammatory and

immunomodulatory effects of the extracellular vesicles derived from

human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells on osteoarthritis via

M2 macrophages. J Nanobiotechnol. 20:382022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Wang Y, Chen H, Fan X, Xu C, Li M, Sun H,

Song J, Jia F, Wei W, Jiang F, et al: Bone marrow mesenchymal stem

cell-derived exosomal miR-193b-5p reduces pyroptosis after ischemic

stroke by targeting AIM2. J Stroke Cerebrovasc. 32:1072352023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Xu YF, Wu YX, Wang HM, Gao CH, Xu YY and

Yan Y: Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cell-conditioned medium

ameliorates diabetic foot ulcers in rats. Clinics (Sao Paulo).

78:1001812023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Zhao Y, Chen Y, Wang Z, Xu C, Qiao S, Liu

T, Qi K, Tong D and Li C: Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell exosome

attenuates Inflammasome-Related pyroptosis via delivering

circ_003564 to improve the recovery of spinal cord injury. Mol

Neurobiol. 59:6771–6789. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Xu H and Xu B: BMSC-Derived exosomes

ameliorate osteoarthritis by inhibiting pyroptosis of cartilage via

delivering miR-326 targeting HDAC3 and STAT1//NF-kappaB p65 to

chondrocytes. Mediat Inflamm. 2021:99728052021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Liang C, Liu Y, Xu H, Huang J, Shen Y,

Chen F and Luo M: Exosomes of human umbilical cord MSCs protect

against Hypoxia/Reoxygenation-Induced pyroptosis of cardiomyocytes

via the miRNA-100-5p/FOXO3/NLRP3 pathway. Front Bioeng Biotech.

8:6158502020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Broz P, Ruby T, Belhocine K, Bouley DM,

Kayagaki N, Dixit VM and Monack DM: Caspase-11 increases

susceptibility to Salmonella infection in the absence of caspase-1.

Nature. 490:288–291. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Strowig T, Henao-Mejia J, Elinav E and

Flavell R: Inflammasomes in health and disease. Nature.

481:278–286. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

He Y, Hara H and Nunez G: Mechanism and

regulation of NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Trends Biochem Sci.

41:1012–1021. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Cookson BT and Brennan MA:

Pro-inflammatory programmed cell death. Trends Microbiol.

9:113–114. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Chen X, He WT, Hu L, Li J, Fang Y, Wang X,

Xu X, Wang Z, Huang K and Han J: Pyroptosis is driven by

non-selective gasdermin-D pore and its morphology is different from

MLKL channel-mediated necroptosis. Cell Res. 26:1007–1020. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Kayagaki N, Stowe IB, Lee BL, O'Rourke K,

Anderson K, Warming S, Cuellar T, Haley B, Roose-Girma M, Phung QT,

et al: Caspase-11 cleaves gasdermin D for non-canonical

inflammasome signalling. Nature. 526:666–671. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Boise LH and Collins CM:

Salmonella-induced cell death: Apoptosis, necrosis or programmed

cell death? Trends Microbiol. 9:64–67. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Li J and Yuan J: Caspases in apoptosis and

beyond. Oncogene. 27:6194–6206. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Shi J, Zhao Y, Wang K, Shi X, Wang Y,

Huang H, Zhuang Y, Cai T, Wang F and Shao F: Cleavage of GSDMD by

inflammatory caspases determines pyroptotic cell death. Nature.

526:660–665. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Matikainen S, Nyman TA and Cypryk W:

Function and regulation of noncanonical Caspase-4/5/11

inflammasome. J Immunol. 204:3063–3069. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

O'Neill TW and Felson DT: Mechanisms of

osteoarthritis (OA) pain. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 16:611–616. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Yu H, Yao S, Zhou C, Fu F, Luo H, Du W,

Jin H, Tong P, Chen D, Wu C and Ruan H: Morroniside attenuates

apoptosis and pyroptosis of chondrocytes and ameliorates

osteoarthritic development by inhibiting NF-kappaB signaling. J

Ethnopharmacol. 266:1134472021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Wu X, Ren G, Zhou R, Ge J and Chen FH: The

role of Ca2+ in acid-sensing ion channel 1a-mediated

chondrocyte pyroptosis in rat adjuvant arthritis. Lab Invest.

99:499–513. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Zhao LR, Xing RL, Wang PM, Zhang NS, Yin

SJ, Li XC and Zhang L: NLRP1 and NLRP3 inflammasomes mediate

LPS/ATP-induced pyroptosis in knee osteoarthritis. Mol Med Rep.

17:5463–5469. 2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Zhang L, Zhang L, Huang Z, Xing R, Li X,

Yin S, Mao J, Zhang N, Mei W, Ding L and Wang P: Increased HIF-α in

knee osteoarthritis aggravate synovial fibrosis via Fibroblast-Like

synoviocyte pyroptosis. Oxid Med Cell Longev.

2019:63265172019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Xu L, Zhang F, Cheng G, Yuan X, Wu Y, Wu

H, Wang Q, Chen J, Kuai J, Chang Y, et al: Attenuation of

experimental osteoarthritis with human adipose-derived mesenchymal

stem cell therapy: Inhibition of the pyroptosis in chondrocytes.

Inflamm Res. 72:89–105. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Liu W, Liu A, Li X, Sun Z, Sun Z, Liu Y,

Wang G, Huang D, Xiong H, Yu S, et al: Dual-engineered

cartilage-targeting extracellular vesicles derived from mesenchymal

stem cells enhance osteoarthritis treatment via

miR-223/NLRP3/pyroptosis axis: Toward a precision therapy. Bioact

Mater. 30:169–183. 2023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Sergio MR, Godinho C, Guerra L, Agapito A,

Fonseca F and Costa C: TSH anti-receptor antibodies in Graves'

disease. Acta Medica Port. 9:229–231, (In Portuguese). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Buckley CT, Hoyland JA, Fujii K, Pandit A,

Iatridis JC and Grad S: Critical aspects and challenges for

intervertebral disc repair and regeneration-Harnessing advances in

tissue engineering. Jor Spine. 1:e10292018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Zhao CQ, Wang LM, Jiang LS and Dai LY: The

cell biology of intervertebral disc aging and degeneration. Ageing

Res Rev. 6:247–261. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Basso M, Cavagnaro L, Zanirato A, Divano

S, Formica C, Formica M and Felli L: What is the clinical evidence

on regenerative medicine in intervertebral disc degeneration?

Musculoskelet Surg. 101:93–104. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Binch A, Fitzgerald JC, Growney EA and

Barry F: Cell-based strategies for IVD repair: Clinical progress

and translational obstacles. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 17:158–175. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Francisco V, Pino J, Gonzalez-Gay MA, Lago

F, Karppinen J, Tervonen O, Mobasheri A and Gualillo O: A new

immunometabolic perspective of intervertebral disc degeneration.

Nat Rev Rheumatol. 18:47–60. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Ge Y, Chen Y, Guo C, Luo H, Fu F, Ji W, Wu

C and Ruan H: Pyroptosis and intervertebral disc degeneration:

Mechanistic insights and therapeutic implications. J Inflamm Res.

15:5857–5871. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Luo J, Yang Y, Wang X, Chang X and Fu S:

Role of pyroptosis in intervertebral disc degeneration and its

therapeutic implications. Biomolecules. 12:18042022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Zhang X, Cai Z, Wu M, Huangfu X, Li J and

Liu X: Adipose stem Cell-Derived exosomes recover impaired matrix

metabolism of torn human rotator cuff tendons by maintaining tissue

homeostasis. Am J Sport Med. 49:899–908. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Shi Y and Wang Y, Li Q, Liu K, Hou J, Shao

C and Wang Y: Immunoregulatory mechanisms of mesenchymal stem and

stromal cells in inflammatory diseases. Nat Rev Nephrol.

14:493–507. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Xing H, Zhang Z, Mao Q, Wang C, Zhou Y,

Zhou X, Ying L, Xu H, Hu S and Zhang N: Injectable

exosome-functionalized extracellular matrix hydrogel for metabolism

balance and pyroptosis regulation in intervertebral disc

degeneration. J Nanobiotechnol. 19:2642021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Zhu B, Chen HX, Li S, Tan JH, Xie Y, Zou

MX, Wang C, Xue JB, Li XL, Cao Y and Yan YG: Comprehensive analysis

of N6-methyladenosine (m6A) modification during the degeneration of

lumbar intervertebral disc in mice. J Orthop Transl. 31:126–138.

2021.

|

|

46

|

Shen C, Xuan B, Yan T, Ma Y, Xu P, Tian X,

Zhang X, Cao Y, Ma D, Zhu X, et al: m6A-dependent

glycolysis enhances colorectal cancer progression. Mol Cancer.

19:722020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Yuan X, Li T, Shi L, Miao J, Guo Y and

Chen Y: Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells deliver

exogenous miR-26a-5p via exosomes to inhibit nucleus pulposus cell

pyroptosis through METTL14/NLRP3. Mol Med. 27:912021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Yu Y, Li W, Xian T, Tu M, Wu H and Zhang

J: Human embryonic stem-cell-derived exosomes repress NLRP3

inflammasome to alleviate pyroptosis in nucleus pulposus cells by

transmitting miR-302c. Int J Mol Sci. 24:76642023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Hunziker EB: Articular cartilage repair:

Basic science and clinical progress. A review of the current status

and prospects. Osteoarthr Cartilage. 10:432–463. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Lin F, Zhang W, Xue D, Zhu T, Li J, Chen

E, Yao X and Pan Z: Signaling pathways involved in the effects of

HMGB1 on mesenchymal stem cell migration and osteoblastic

differentiation. Int J Mol Med. 37:789–797. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Bertheloot D and Latz E: HMGB1, IL-1α,

IL-33 and S100 proteins: Dual-function alarmins. Cell Mol Immunol.

14:43–64. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Koh TJ and DiPietro LA: Inflammation and

wound healing: The role of the macrophage. Expert Rev Mol Med.

13:e232011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Han SA, Lee S, Seong SC and Lee MC:

Effects of CD14 macrophages and proinflammatory cytokines on

chondrogenesis in osteoarthritic synovium-derived stem cells.

Tissue Eng Pt A. 20:2680–2691. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Wehling N, Palmer GD, Pilapil C, Liu F,

Wells JW, Muller PE, Evans CH and Porter RM: Interleukin-1beta and

tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibit chondrogenesis by human

mesenchymal stem cells through NF-kappaB-dependent pathways.

Arthritis Rheum. 60:801–812. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Yang Z, Li H, Yuan Z, Fu L, Jiang S, Gao

C, Wang F, Zha K, Tian G, Sun Z, et al: Endogenous cell recruitment

strategy for articular cartilage regeneration. Acta Biomater.

114:31–52. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Liao Z, Fu L, Li P, Wu J, Yuan X, Ning C,

Ding Z, Sui X, Liu S and Guo Q: Incorporation of magnesium ions

into an Aptamer-Functionalized ECM bioactive scaffold for articular

cartilage regeneration. Acs Appl Mater Inter. 15:22944–22958. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Park KS, Kim BJ, Lih E, Park W, Lee SH,

Joung YK and Han DK: Versatile effects of magnesium hydroxide

nanoparticles in PLGA scaffold-mediated chondrogenesis. Acta

Biomater. 73:204–216. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Barakat AH, Elwell VA and Lam KS: Stem

cell therapy in discogenic back pain. J Spine Surg. 5:561–583.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Sakai D and Andersson GB: Stem cell

therapy for intervertebral disc regeneration: Obstacles and

solutions. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 11:243–256. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Yu C, Li D, Wang C, Xia K, Wang J, Zhou X,

Ying L, Shu J, Huang X, Xu H, et al: Injectable kartogenin and

apocynin loaded micelle enhances the alleviation of intervertebral

disc degeneration by adipose-derived stem cell. Bioact Mater.

6:3568–3579. 2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Zhou X, Wang J, Fang W, Tao Y, Zhao T, Xia

K, Liang C, Hua J, Li F and Chen Q: Genipin cross-linked type II

collagen/chondroitin sulfate composite hydrogel-like cell delivery

system induces differentiation of adipose-derived stem cells and

regenerates degenerated nucleus pulposus. Acta Biomater.

71:496–509. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Xia KS, Li DD, Wang CG, Ying LW, Wang JK,

Yang B, Shu JW, Huang XP, Zhang YA, Yu C, et al: An

esterase-responsive ibuprofen nano-micelle pre-modified embryo

derived nucleus pulposus progenitor cells promote the regeneration

of intervertebral disc degeneration. Bioact Mater. 21:69–85.

2023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Yang J, Hu S, Bian Y, Yao J, Wang D, Liu

X, Guo Z, Zhang S and Peng L: Targeting cell death: Pyroptosis,

ferroptosis, apoptosis and necroptosis in osteoarthritis. Front

Cell Dev Biol. 9:7899482021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Tibaut M, Mekis D and Petrovic D:

Pathophysiology of myocardial infarction and acute management

strategies. Cardiovasc Hematol Agents Med Chem. 14:150–159. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Zhou M, Yu Y, Luo X, Wang J, Lan X, Liu P,

Feng Y and Jian W: Myocardial Ischemia-reperfusion injury:

Therapeutics from a mitochondria-centric perspective. Cardiology.

146:781–792. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Toldo S, Mauro AG, Cutter Z and Abbate A:

Inflammasome, pyroptosis, and cytokines in myocardial

ischemia-reperfusion injury. Am J Physiol-Heart C. 315:H1553–H1568.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Qiu Z, Lei S, Zhao B, Wu Y, Su W, Liu M,

Meng Q, Zhou B, Leng Y and Xia ZY: NLRP3 inflammasome

activation-mediated pyroptosis aggravates myocardial

ischemia/reperfusion injury in diabetic rats. Oxid Med Cell Longev.

2017:97432802017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Kalluri R and LeBleu VS: The biology,

function, and biomedical applications of exosomes. Science.

367:eaau69772020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Tang J, Jin L, Liu Y, Li L, Ma Y, Lu L, Ma

J, Ding P, Yang X, Liu J and Yang J: Exosomes derived from

mesenchymal stem cells protect the myocardium against

ischemia/reperfusion injury through inhibiting pyroptosis. Drug Des

Devel Ther. 14:3765–7375. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Mao Q, Liang XL, Zhang CL, Pang YH and Lu

YX: LncRNA KLF3-AS1 in human mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes

ameliorates pyroptosis of cardiomyocytes and myocardial infarction

through miR-138-5p/Sirt1 axis. Stem Cell Res Ther. 10:3932019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Yan B, Liu T, Yao C, Liu X, Du Q and Pan

L: LncRNA XIST shuttled by adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem

cell-derived extracellular vesicles suppresses myocardial

pyroptosis in atrial fibrillation by disrupting miR-214-3p-mediated

Arl2 inhibition. Lab Invest. 101:1427–1438. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Yan B, Zhang Y, Liang C, Liu B, Ding F,

Wang Y, Zhu B, Zhao R, Yu XY and Li Y: Stem cell-derived exosomes

prevent pyroptosis and repair ischemic muscle injury through a

novel exosome/circHIPK3/ FOXO3a pathway. Theranostics.

10:6728–6742. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Feigin VL, Norrving B, George MG, Foltz

JL, Roth GA and Mensah GA: Prevention of stroke: A strategic global

imperative. Nat Rev Neurol. 12:501–512. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Jayaraj RL, Azimullah S, Beiram R, Jalal

FY and Rosenberg GA: Neuroinflammation: Friend and foe for ischemic

stroke. J Neuroinflamm. 16:1422019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

75

|

Madore C, Yin Z, Leibowitz J and Butovsky

O: Microglia, lifestyle stress, and neurodegeneration. Immunity.

52:222–240. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Li W, Shen N, Kong L, Huang H, Wang X,

Zhang Y, Wang G, Xu P and Hu W: STING mediates microglial

pyroptosis via interaction with NLRP3 in cerebral ischaemic stroke.

Stroke Vasc Neurol. svn-2023-002320. 2023.doi:

10.1136/svn-2023-002320. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

77

|

Huang Y, Tan F, Zhuo Y, Liu J, He J, Duan

D, Lu M and Hu Z: Hypoxia-preconditioned olfactory mucosa

mesenchymal stem cells abolish cerebral

ischemia/reperfusion-induced pyroptosis and apoptotic death of

microglial cells by activating HIF-1alpha. Aging (Albany Ny).

12:10931–10950. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Hu Z, Yuan Y, Zhang X, Lu Y, Dong N, Jiang

X, Xu J and Zheng D: Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem

Cell-Derived exosomes attenuate Oxygen-Glucose

Deprivation/Reperfusion-Induced microglial pyroptosis by promoting

FOXO3a-dependent mitophagy. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2021:62197152021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Liu X, Zhang M, Liu H, Zhu R, He H, Zhou

Y, Zhang Y, Li C, Liang D, Zeng Q and Huang G: Bone marrow

mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes attenuate cerebral

ischemia-reperfusion injury-induced neuroinflammation and

pyroptosis by modulating microglia M1/M2 phenotypes. Exp Neurol.

341:1137002021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Huang Y, Wang S, Huang F, Zhang Q, Qin B,

Liao L, Wang M, Wan H, Yan W, Chen D, et al: c-FLIP regulates

pyroptosis in retinal neurons following oxygen-glucose

deprivation/recovery via a GSDMD-mediated pathway. Ann Anat.

235:1516722021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Zhou Z, Shang L, Zhang Q, Hu X, Huang JF

and Xiong K: DTX3L induced NLRP3 ubiquitination inhibit R28 cell

pyroptosis in OGD/R injury. Bba-Mol Cell Res.

1870:1194332023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Dreixler JC, Poston JN, Balyasnikova I,

Shaikh AR, Tupper KY, Conway S, Boddapati V, Marcet MM, Lesniak MS

and Roth S: Delayed administration of bone marrow mesenchymal stem

cell conditioned medium significantly improves outcome after

retinal ischemia in rats. Invest Ophth Vis Sci. 55:3785–3796. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Mathew B, Poston JN, Dreixler JC, Torres

L, Lopez J, Zelkha R, Balyasnikova I, Lesniak MS and Roth S:

Bone-marrow mesenchymal stem-cell administration significantly

improves outcome after retinal ischemia in rats. Graef Arch Clin

Exp. 255:1581–1592. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Mathew B, Ravindran S, Liu X, Torres L,

Chennakesavalu M, Huang CC, Feng L, Zelka R, Lopez J, Sharma M and

Roth S: Mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles and

retinal ischemia-reperfusion. Biomaterials. 197:146–1460. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Neumar RW, Nolan JP, Adrie C, Aibiki M,

Berg RA, Bottiger BW, Callaway C, Clark RS, Geocadin RG, Jauch EC,

et al: Post-cardiac arrest syndrome: Epidemiology, pathophysiology,

treatment, and prognostication. A consensus statement from the

International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (American Heart

Association, Australian and New Zealand Council on Resuscitation,

European Resuscitation Council, Heart and Stroke Foundation of

Canada, InterAmerican Heart Foundation, Resuscitation Council of

Asia, and the Resuscitation Council of Southern Africa); the

American Heart Association Emergency Cardiovascular Care Committee;

the Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia; the Council

on Cardiopulmonary, Perioperative, and Critical Care; the Council

on Clinical Cardiology; and the Stroke Council. Circulation.

118:2452–2483. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Yu Y, Wang D, Li H, Fan J, Liu Y, Zhao X,

Wu J and Jing X: Mesenchymal stem cells derived from induced

pluripotent stem cells play a key role in immunomodulation during

cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Brain Res. 1720:1462932019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

Weyker PD, Webb CA, Kiamanesh D and Flynn

BC: Lung ischemia reperfusion injury: A bench-to-bedside review.

Semin Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 17:28–43. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Fei L, Jingyuan X, Fangte L, Huijun D, Liu

Y, Ren J, Jinyuan L and Linghui P: Preconditioning with rHMGB1

ameliorates lung ischemia-reperfusion injury by inhibiting alveolar

macrophage pyroptosis via the Keap1/Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway. J

Transl Med. 18:3012020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

89

|

Shologu N, Scully M, Laffey JG and O'Toole

D: Human mesenchymal stem cell secretome from bone marrow or

Adipose-Derived tissue sources for treatment of hypoxia-induced

pulmonary epithelial injury. Int J Mol Sci. 19:29962018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

90

|

Sun ZL, You T, Zhang BH, Liu Y and Liu J:

Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes miR-202-5p

inhibited pyroptosis to alleviate lung ischemic-reperfusion injury

by targeting CMPK2. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 39:688–698. 2023.