Cord blood (CB) has been a significant source of

haematopoietic stem cells. The therapeutic value of CB has been

examined since the late 90s when the first transplantation

effectively treated a 5-year-old patient with Fanconi anaemia

(1). Considering the potential of

CB and its viability for autologous use, the practice of CB banking

has been extensively embraced to maintain the CB unit from birth,

either through government-funded organisations or private companies

with a storage charge (2).

However, such an approach has also been affected by the high

running cost, the actual clinical utilisation and new emergent

alternatives (3), thus prompting

the cell banking endeavour and its sustainability to be carefully

revisited.

Strategies have been introduced to keep the cell

banking endeavour relevant, including the introduction of criteria

for CB cryopreservation, CB cell expansion, use in allogeneic

transplantation and exploring novel medicinal uses. However, the

use of CB in the clinic is predominantly focused on treating

haematological diseases, which hinders the progress of cell banking

initiatives aimed at achieving broader storage and clinical

benefits.

There is an increasing interest in converting CB

into hiPSCs as an approach to resolve the underutilized CB unit in

the cell bank (4,5), since hiPSCs present with greater

therapeutic value and applications. This could potentially enhance

the utility of CB and satisfy the rising need for hiPSCs, which

could redefine the future of regenerative medicine.

The present review discusses the rise and fall of CB

usage and banking for clinical transplantation, including the early

discovery of CB characteristics and therapeutic value, the

development of past trials that subsequently promoted the growth of

the CB bank and industry, the challenge of using low total

nucleated cells (TNCs) in CB and the strategy to expand the cells

for autologous transplantation, the change in trends of application

from intended autologous to allogeneic use, and lastly, the shift

of preference to haploidentical haematopoietic stem cell (HSC)

transplantation from using allogeneic CB. The review also

summarizes the considerations in reprogramming CB into hiPSCs,

including the reprogramming methods, the advantages of using CB as

the choice of somatic cells for reprogramming, as well as the

disadvantages, and the latest strategies for overcoming iPSC

allogenicity. Lastly, the prospect of using CB-iPSC banking and the

opportunity that it creates is discussed.

HSCs, which can differentiate into any type of blood

cell, are found in umbilical CB. Just 0.02–1.43% of the

mononucleated cells in CB are CD34+ HSCs, which is a

density that is higher than that found in the peripheral blood (PB)

(<0.01%) but lower than that found in the bone marrow (0.5–5.0%)

(6). The colony-forming cell

content has not only been found to be associated with the

CD34+ cell number, but is also associated with the

gestational age of the newborn (7). CB-derived HSCs exhibit a greater

growth response to known mitogens and cytokines, and are less

reliant on the support of stromal cells (8). These properties allow CB-HSCs to

exit the G0/G1 phase and divide more rapidly

than HSCs from other adult tissues under the same culture

conditions (9).

The first CB transplantation to a 5-year-old patient

with severe Fanconi anaemia was performed in 1988 (1), establishing precedence for

subsequent use of CB in transplantation between identical siblings

after cryopreservation (18).

Complete haematopoietic reconstitution has also been shown to be

possible following CB transplantation in HLA mismatched siblings or

unrelated patients with leukaemia, as documented in previous

studies (18,19). Broxmeyer et al (20) reported that nucleated HSCs were

found to remain effective and functional even after being frozen

for 23 years. CD34+ cells isolated from cryopreserved CB

were also capable of successful integration and functioning after 6

months in primary and secondary immunodeficient mice, suggesting

that cryopreservation does not affect the function of injected HSCs

in the long term (20). The

growing banking service for CB worldwide has garnered a substantial

number of transplantable units for use in clinical

transplantation.

According to the World Marrow Donor Association, the

global inventory of CB has grown by >800,000 units in 2022

(21), and >40,000 CB

transplantations have been performed in both paediatric and adult

patients (9), for treating either

malignant or non-malignant haematological diseases. In leukemic

paediatric patients, the transplantation of complete HLA-matched CB

has shown to have comparable effects with bone marrow from sibling

donors (22). In children with

haematopoietic malignancies, related HLA-identical CB

transplantation achieved neutrophil recovery in 90% in patients

with a median age of 5 years, and the incidence of GvHD was only

10–12% at 2 years post-transplant (23), with non-relapse mortality at 9%

and relapse at 47% at 5 years post-transplant. It was also

highlighted that transplanted CB units with higher TNCs contributed

to greater neutrophil recovery and a greater disease-free survival

rate. Similarly, 2-loci mismatched, unrelated CB units also

demonstrated similar therapeutic effects compared with matched

adult marrow transplants (24,25).

It was also found that the higher the HLA disparity

and mismatch, the lower the 5-year survival rate observed in

paediatric donor-recipient pairs who received single unit CB graft

(26). The relative risk of CB

transplant-related mortality has shown to rise with increasing HLA

mismatch (26), despite the lower

rate of relapse (25,27,28). This evidence collectively suggests

that CB transplantation is the ideal option in paediatric patients

provided that the CB unit is sufficiently HLA-matched and the

therapeutic cell number is adequate. In conclusion, successful

transplantation, especially in pediatric patients, relies on

sufficient cell numbers in CB units. Higher TNCs improve outcomes,

while proper HLA matching and cell quantity reduce GvHD. Even

mismatched CB units can perform similarly to matched adult

transplants, highlighting the importance of stem cell numbers for

engraftment and survival.

CB from an allogenic source remains the most used in

clinical transplantation compared with CB from an autologous source

(29). In a survey by the

European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation, it was shown

that, of the 119 patients transfused with CB, 75% of the

transplanted grafts were from unrelated donors. As patients are

unrelated, HLA matching between the donor CB unit and the recipient

patient is important to minimize graft rejection and increase the

eventual patient survival time (29). Based on the National Marrow Donor

Program and The Centre for International Blood and Marrow

Transplant Research (CIBMTR) guidelines, patients and donor CB

grafts should be HLA typed for HLA-A, HLA-B, HLA-C and HLA-DRB1, as

well as the confirmatory typing for DQB1 and DPB1, at high

resolution using DNA methods (30). However, the availability of such

fully HLA-matched CB units (6/6 loci) is only ~10%, and is highly

dependent on the race and ethnic group of the CB donor (31). Mismatched CB units at one or two

HLA loci could be considered and have been previously been found to

work in all patients <20 years old and in 75% of patients ≥20

years old (31–33).

Another factor that determines the outcome of the

transplantation is the number of TNCs in CB unit. Table I (30,34–37) summarizes the minimum cell number

required for single- or double-unit infusion. The Center for

International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR),

Eurocord and the European Group for Blood and Marrow

Transplantation collaborative group recommended a 2×107

TNCs/kg of recipient for a single unit, and this was found to be

associated with sufficient engraftment of progenitor cells and

successful transplantation (27).

A TNC number <2×107 TNCs/kg proved to have a lower

therapeutic value, including delayed engraftment and lower

transplant-related mortality (38). Furthermore, a high TNC number

(>5.0×107/kg) could subdue the effect of two HLA

mismatches, and HLA matching can compensate for the disadvantage of

a low TNC number (39). More

notably, improved event-free survival rate was found to correlate

with higher CD34+ cells in the CB unit but was not

associated with TNC number (19).

Considering the pros and cons, recommendations are

made to ensure the minimum level of both the TNCs and

CD34+ cells in each cryopreserved CB unit are met

(Table I) in order to balance the

cost and the therapeutic benefit. Collected CB units that fail to

meet these requirements are discarded. These ‘unqualified’ CB units

account for ~36–39% of the total collected CB units (40). This practice not only incurs

substantial operational costs involving steps from CB collection to

cell analysis, but also involves sacrificing CB units of high

therapeutic or research value, especially from donors with rare

blood types or diseases (41).

Hence, to address low TNC numbers in CB units, the logical and

immediate solutions to increase the cell number for transplantation

are as follows: i) Combining two CB grafts (42,43); and ii) expanding the autologous

cells to a therapeutically meaningful number in vitro.

A systematic review and meta-analysis of 9

controlled clinical trials (phase I–III) involving 1,146 patients

who underwent umbilical CB transplantation (UCBT) (44–52) using ex vivo expanded or

unmanipulated grafts was conducted by Saiyin et al (2023)

(53). The expansion strategies

employed in the included studies consisted of cytokine cocktails

combined with small molecules such as UM171, nicotinamide (NiCord),

copper chelation, Notch ligand or Stem regenin-1 (SR-1) (Table II) (49,50,52,54–56) or coculture with mesenchymal

stromal cells or double unit transplantation. The meta-analysis

concluded that transplantation using ex vivo expanded CB

significantly reduced neutrophil recovery time in patients compared

to transplantation with unmanipulated units. Notably, the infused

cell dose did not correlate with time to neutrophil and platelet

recovery. Additionally, patients receiving expanded CB transplants

exhibited a significant decrease in the risk of death at the study

endpoint, and graft failure only occurred in 0 to 10% of patients

using expanded cells. Moreover, with the transplantation of

expanded CB units using mesenchymal stromal cells or Notch

ligand-expanded cells in combination with a second unmanipulated

CB, the expanded population were found to be overtaken by

unmanipulated CB at 1-year post-transplantation. SR-1 and NiCord

expanded CB units achieved graft dominance after a year if double

units were used in the transplantation, but this was only seen in

35 and 78% of the patients, respectively (49,51). Nonetheless, the overall CB

expansion and time to initial neutrophil recovery do not always

improve survival, and there is no statistical difference in the

risk of acute GvHD between patients administered ex vivo

expanded CB units and controls (57). A study has also found that

excellent overall survival rate was observed in patients with

unmanipulated CB despite the low medium infusion of TNCs and the

slower engraftment (45).

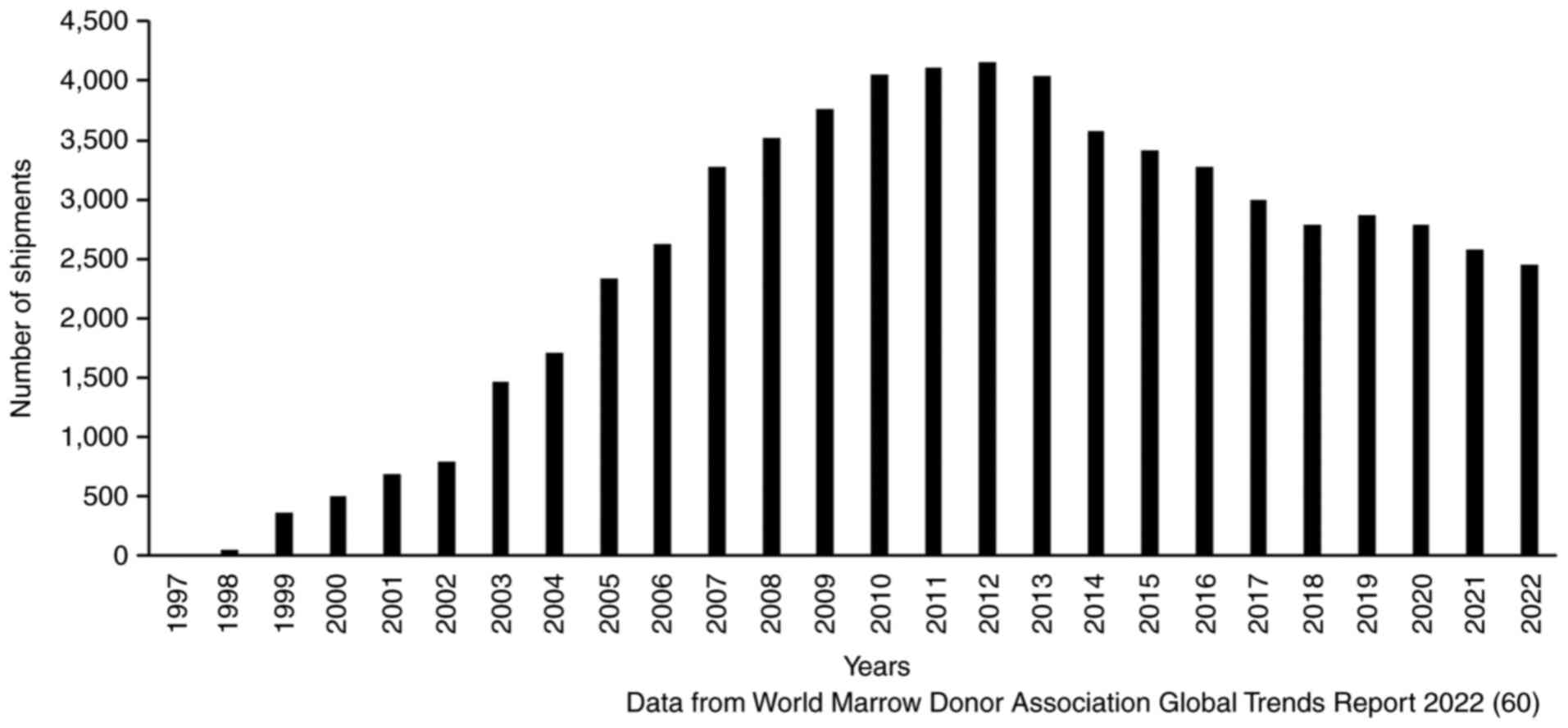

The growing banking service for CB worldwide has

garnered substantial transplantable units for use in clinical

transplantation. Despite the promising growth in the global

inventory of CB (21), the total

number of units dispensed has reduced from 4,150 units in 2012 to

2,450 units in 2022, a reduction of 41.0% in the past decade

(Fig. 1). According to a special

report by Passweg et al studying the trends of

haematopoietic stem cell transplantation in Europe in 2013, CB was

only used in 2 out of 22,998 autologous transplantations, while

only 5 out of 7,624 allogeneic transplantations involved related

family members and 666 out of 8,587 were transplanted to unrelated

patients (58). The decline in

using CB is also due to the marked increase in haploidentical

transplantation, and a similar trend was also observed by the Asia

Pacific Blood and Marrow Transplantation Group (59) and the Worldwide Network of Blood

and Marrow Transplantation (60).

Allogenic stem cell transplantation has become the treatment of

choice for high-risk haematological malignancies, and the

established sources of HSCs for these patients are either CB or

haploidentical donors when there is a lack of HLA-matched

donors.

Haploidentical donors are immediate family members

who possess tissue with half matching HLA haplotypes. The shift of

preference towards haploidentical HSC transplantation, particularly

from PB, is mainly due to the high cell source availability, fresh

HSC isolation from donors upon demand without the need for

cryopreservation, a shorter time to transplantation without the

need to mobilize or transport matched grafts from cell banks, such

as CB, and therefore a significantly lower cost per

transplantation. More importantly, there are no statistical

differences in the main outcomes between haplo-HSC and CB

transplantation, including relapse incidence, leukaemia-free

survival, 2-year non-relapse mortality rate and overall survival

rate (61,62). In some trials, CB transplantation

demonstrated more disadvantages than the haplo-graft

transplantation, including slow neutrophil recovery and a relative

higher risk of grade II–IV acute GvHD (63,64).

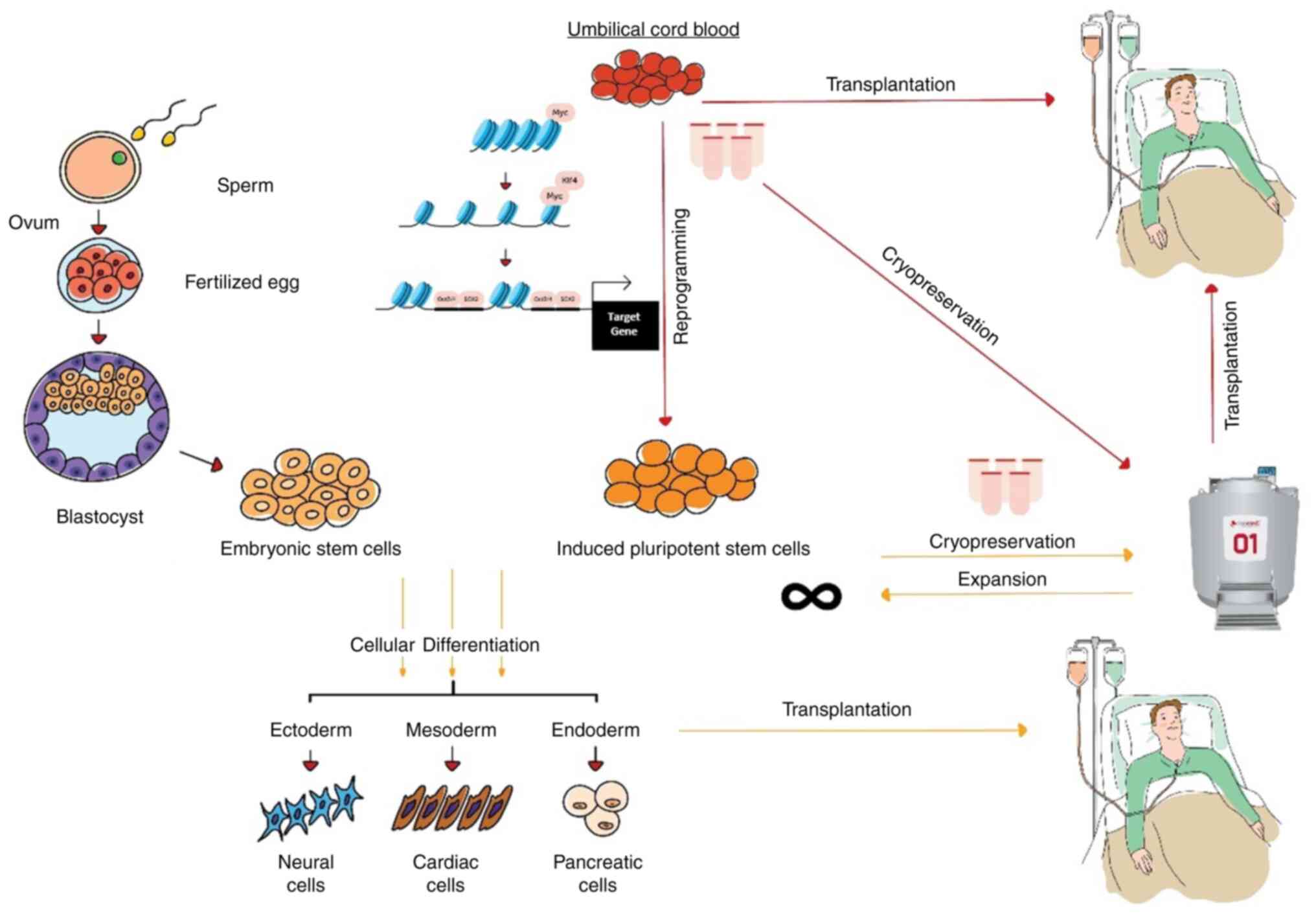

hiPSCs are cells that are created through cellular

reprogramming, a technology introduced by Takahashi and Yamanaka

(2006) to reverse the fate of differentiated cells back to the

pluripotent stage (65). The

invention enables the making of PSCs from any adult somatic cells

possible, and the cells possess the differentiation plasticity of

the embryonic stem cells. Recently, the induced PSCs were also

found to be capable of cultivating synthetic embryos (66), opening vast opportunities to study

complex embryology and early human development. Judging from the

enormous variety of applications and the therapeutic potential that

hiPSCs could offer, and the recent decline in CB transplantation in

clinics, several reports have proposed to convert cryopreserved CB

into hiPSCs (4,67) (Fig.

2). Efforts to revamp the cell banking industry and

revolutionize regenerative medicine have begun by promoting the use

of hiPSCs. The present review discusses and summarizes the

information, including the reprogramming methods assessed on CB,

the comparison between the use of CB and adult PB, and the advances

in establishing hiPSC haplobank or hypoimmunogenic lines as the

off-the-shelf cell source for clinical treatment.

Several reprograming and hiPSC generation methods

have been introduced since its discovery. In general, both

integrating and non-integrating methods have been used in

reprogramming CB (Table III)

(20,68–79). Evidence has shown that the

reprogramming of CB is possible even it has been frozen for 21

years (20). The outcome of this

was also confirmed to be comparable to that of fresh CB (70). The long-term cryopreservation of

CB did not impede the formation of embryoid bodies in both in

vivo and ex vivo studies, and the injection of hiPSCs

into testis capsules of immune-deficient mice demonstrating

spontaneous differentiation into cells of all three germ layers

(20). The present review

summarizes and emphasizes the reprogramming methods that have

previously successfully generated hiPSCs, namely use of

retroviruses and lentiviruses, episomal transfection of vectors,

and use of Sendai virus, self-replicative RNA (srRNA), microRNA

(miRNA/miR) or defined chemicals (Table III).

Retroviruses rely on the infectivity of host cells

via receptor-mediated endocytosis to achieve stable genomic

integration of the RNA reprogramming factors with the aid of the

reverse transcriptase and integrase enzymes (80). The transgenes transduced into host

cells allow for stable expression and maintenance for 30 days

before generating the iPSCs. CD34+ cells that were

transduced with retroviruses carrying Yamanaka's factors and p53

short-hairpin RNA vectors enhanced the reprogramming efficiency.

p53 short hairpin RNA vectors are crucial in inhibiting the p53

pathway (69). However,

retroviruses are prone to insertional mutagenesis, raising the

safety concern over their use in the clinic (68).

Lentiviruses are RNA viruses that are capable of

infecting both dividing and non-dividing cells. After reverse

transcription, the lentiviral genome will be integrated into the

host cell genome, allowing long-term expression of the inserted

genes in the target cells in vitro. Haase et al

(70) successfully generated

iPSCs from proliferative CB endothelial cells and yielded better

results than with PB. Lentiviral vector-mediated transduction of

OCT3/4 and SOX2 alone was found to sufficiently

reprogram CB CD34+ cells into hiPSCs with an efficiency

of 2% (81), an outcome that was

higher by 1,000-fold than that of using a retrovirus. However,

early lentivirus vectors tend to integrate transgenes into target

cells, leading to host genome sequence changes (81). These transgenes were not silenced

in the generated hiPSCs and could result in tumour formation,

especially due to the high expression of c-Myc and

Klf4, known oncogenes. A safer, self-inactivating

third-generation lentiviral system has been introduced, with the

packaging system containing two plasmids: the Rev encoding and Gag

and Pol encoding plasmids. Multiple clinical trials have shown that

third-generation lentiviral vectors can introduce genes to HSCs to

treat hemoglobinopathies and primary immunodeficiencies (82,83). However, the use of

third-generation lentiviral systems is still not applied in iPSC

generation.

The non-integrating, self-replicating vector

delivery system using EBNA1/OriP, capable of long-term persistence

in cells to mediate nuclear import and retention of vector DNA,

allows hiPSC derivation from a single transfection. EBNA vectors

express the EBNA1 gene to deliver episomal vectors into somatic

cells. This method is a transgene-free approach, whereby episomal

vectors are removed from iPSCs without integration into genomic DNA

(72). A study using CB, which

has been cryopreserved for 13 years, demonstrated that transduction

with EBNA1/OriP resulted in a highly efficient generation of hiPSCs

obtained within 14 days, with 1,000 hiPSC colonies created per 2

million transfected cells. A parallel experiment with

PB-mononuclear cells indicated a 50-fold lower efficiency in

deriving hiPSCs compared with that for CB (73).

Also, the non-integrating method using the Sendai

virus vector (SeV) can generate hiPSCs without foreign gene

insertions into the host genome. This approach is highly applicable

for future clinical use, as SeV can be produced with

temperature-sensitive mutations, making the vectors easily

removable at non-permissive temperatures, thereby eliminating the

foreign genes in the mature hiPSCs (74). Another study demonstrated that

CD34+ CB could be reprogrammed with volumes as low as 5

ml for each procedure using a viral mixture of SeV

TS7-OCT3/4, -SOX2, -KLF4 and -c-MYC to

generate 10 independent hiPSCs per ml of blood (74). In 2019, the SeV reprogramming

method was used to reprogram the CB CD34+ cells of a

female child to create iPSCs (75). Recently, Kunitomi et al

(84) developed a more precise

and versatile SeV-KLF4 by modifying the vector to include L-MYC in

place of c-MYC, and also adjusted the temperature settings during

cell maintenance and reprogramming. Thus, naive hiPSCs showed a

significantly improved ability to differentiate into trilineage

lineages (85).

Reprogramming can also be achieved by using srRNA or

miRNA. The non-integrating srRNA that encodes Venezuelan equine

encephalitis (VEE) replicon carried the four reprogramming

transcription factors OCT3/4, SOX2, KLF4 and cMYC, or with GLIS1 in

replacement of cMYC, was found to successfully induce reprogramming

in newborn or adult fibroblasts (86). This reprogramming process was

facilitated by supplementing B18R recombinant protein, an essential

virus-encoded receptor, which increased cell viability during RNA

transfection, that neutralizes type 1 interferon induced by VEE RNA

(86). In addition, the ES

cell-specific cell cycle-regulating miRNAs miR-291-3p, miR-294 and

miR-295 also showed enhanced retrovirus-mediated expression of

OCT3/4, SOX2 and KLF4 (87). Similar mRNA-facilitated srRNA

reprogramming was also employed and assessed in a study that

compared the reprogramming efficiency of CB-derived endothelial

progenitor cells (CB-EPCs) with PB-EPCs. CB-EPCs were found to be

more efficiently reprogrammed than PB-EPCs, as shown by a 3.5-fold

increase in colony formation and cell number, along with results

from pluripotent gene expression microarrays (77).

An alternative reprogramming method has been

introduced using small molecules to replace the conventional

gene-mediated reprogramming method. In the study by Chou et

al (73), it was demonstrated

that the use of the small molecule compound VC6TFZ, consisting of 6

specific molecules [valproic acid sodium salt (VPA), CHIR99021,

616452, tranylcypromine, forskolin and 3-deazaneplanocin A

(DZNep)], followed by dual inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase

and mitogen-activated protein kinase, could efficiently generate

hiPSCs from mouse embryonic fibroblasts without the ectopic

expression of reprogramming genes (88). Nonetheless, this method has not

been used in reprogramming CB cells into hiPSCs, although direct

programming of CB erythroblasts to induced megakaryocytes was

demonstrated using Bix01294, PD0325901, VPA and RG108 (89).

The cellular reprogramming process involves

resetting the epigenetic landscape of a somatic cell and reverting

it back to a pluripotent state. Studies have shown that cellular

reprogramming and the subsequent differentiation efficiency are

affected by several factors, which include the age of the parental

somatic cells, cell origin, type of cell and the method of

reprogramming or differentiation (90–93). The types of parental somatic cells

used in reprogramming do not seem to have induced variability in

the resultant hiPSCs. For instance, a study that tested fibroblast

and blood cells from the same donor showed no major variability

between the produced hiPSCs, in terms of both reprogramming and

differentiation efficiency (94),

but evidence has proven that the retained residual epigenetic

memory in the generated iPSCs could make the cells prone to

differentiation towards their tissue of origin (91,92). Moreover, hiPSCs derived from cells

of genetically different donors revealed significant differences in

the hiPSC differentiation efficiency (90,94).

Additionally, higher reprogramming efficiency was

observed when younger, juvenescent somatic cells that possess less

epigenetic modifications were used (95). A study by Lo Sardo et al

(95) showed that hiPSCs

generated from the PB of young individuals in their twenties,

middle-aged individuals at 49–79 years old and the elderly at

86–100 years old showed no difference in reprogramming efficiency.

The study also reported that a significantly higher level of

methylation was found in donor cells from older individuals, with a

5% increase in the global methylation level at CpG sites (95). This makes the relative resistance

to demethylation in age-associated CpG sites higher during cellular

reprogramming in older donors. This is in line with the observation

reported in the study by Gao et al (2017) (77), which compared hiPSCs derived from

EPCs, CB and adult PB. The study showed that a higher reprogramming

efficiency was evident in CB-EPCs compared with that in PB-derived

cells. Furthermore, hiPSCs from aged donors retained an epigenetic

signature of age, which could be slowly reduced through in

vitro passaging, but the older the parental cells, the higher

the risk of exomic mutation present in the generated hiPSCs, as

evidenced by whole-exome sequencing analyses that demonstrated an

increased frequency of mutations correlating with donor age

(95).

The most discussed advantages of using CB as the

cell source for generating hiPSCs are the availability of the cells

in CB banks, the primitive nature of the cells (free from any

acquired mutations such as those found in other somatic cells) and

their young age. Studies have shown that the function of the

generated hiPSCs does not seem to be affected by the age of the

donor cells (96), as the

epigenetic signature of ageing in hiPSCs can be reduced with in

vitro passaging (95). In

general, CB-derived cells were more proliferative than those from

adult PB (70), and the advantage

of using youthful CB cells was evident in their reprogramming

efficiency (95). However, no

difference in differentiation was found when comparing the hiPSCs

from CB and PB (73). Other

studies have also concluded that the differentiated cells from

different hiPSCs donor sources possess no difference, or functional

superiority in in vivo heart function after transplantation

(92).

Nonetheless, a significant drawback in generating

hiPSCs from CB is the additional cost required for cell separation

to purify mononuclear cells or CD34-expressing HSCs, similar to the

situation in PB. This process is necessary, as attempts to

reprogram red blood cells into hiPSCs have not been successful due

to the lack of a nucleus in mature red blood cells.

The use of CB-iPSCs only for autologous means may

incur a substantial cost of preparation and maintenance, and it is

more applicable to personalized and precision testing, and

treatment in patients with specific conditions or family members.

Allogeneic use of the cells is, however, more likely to be the

option to reduce the cost of maintenance and to maximize the usage

across different patients. One of the strategies to lower the

immunogenicity of CB-hiPSC-derived cells is to identify HLA

haplotype homozygous CB donors. Research has shown that cells from

HLA haplotype homozygous donors can benefit significant numbers of

patients in the country or populations with low HLA diversity

(97,98). By using this method, off-the-shelf

allogenic CB-hiPSCs that are haploidentical to a good majority of

the population can be generated in large quantity and decrease the

time and cost when compared with individualized hiPSC

manufacturing.

In Japan, a clinical-grade hiPSC haplobank was

established with 27 hiPSC lines derived from 7 HLA-homozygous

donors, which was claimed capable of covering 40% of the Japanese

population (99). The haplobank

has provided the iPSCs for more than 10 clinical trials since 2015.

Similarly, in Spain, an iPSC haplobank was established through a

search of 32,000 bone marrow donors and CB donors from the Spanish

Bone Marrow Donor Registry (99).

A total of 10 CB units from homozygous donors stored were found to

meet HLA-A, HLA-B and HLA-DRB1 matching for 28.23% of the

population (100). The efforts

also led to the formation of The Global Alliance for iPSC

Therapies, which consolidate and assess the feasibility in

developing the global haplobank partnership in the generation of

clinical grade hiPSCs (101).

Autologous cell transplantation is still a

favourable option considering its better graft engraftment and low

immunogenicity compared with allogenic cells post-transplantation.

However, generating hiPSCs processed from an autologous source can

be costly and time-consuming, while long-term immunosuppression may

be needed if hiPSCs from an allogeneic source are used, despite

some precedence of successful clinical translation (Table III). The major underlying cause

of the immune rejection is the highly polymorphic major

histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules, the primary trigger of

T-cell-mediated cytotoxic responses upon the recognition of the

alloantigen presented on antigen-presenting cells.

Recently, a strategy to remove the MHC class I and

II expression, by gene-editing the B2m gene (a structural

component of MHC class-I molecules) and Ciita (the master

regulator of MHC class-II molecules), has been introduced to reduce

the cell-immunogenicity, cloaking the cells from the

immuno-surveillance by T cell-mediated adaptive responses (102). The cells were also engineered to

express CD47 transmembrane protein alone (103) or with immunoregulatory factors

inhibitors, such as program death-ligand 1 and human leucocyte

antigen-G, to better prevent both the T cell- and natural killer

cell-mediated immune responses, as well as macrophage engulfment

(104). These methods have

successfully created universal, allogenic hiPSCs with

‘hypoimmunogenic’, without compromising the cell pluripotency,

differentiation and post-differentiation cell functions, as

demonstrated in humanized animals (genetically or biologically

modified to express human genes or contain human cells, tissues or

organs) post-transplantation in the absence of immunosuppression

(103).

A critical issue concerning the clinical use of

patient-specific hiPSCs is the accumulation of somatic (stem) cell

mutations over an organism's lifetime. Acquired somatic mutations

are passed on to hiPSCs during reprogramming and may be associated

with the loss of cellular functions and cancer formation (105). Cell reprogramming has also been

associated with defective epigenetic reversion and gene expression

changes, which raise safety concerns and the possibility of

treatment failure. hiPSCs would inevitably retain a certain form of

epigenetic memory linked to their parental cells (91). The presence of these epigenetic

signatures would thus skew the differentiation potential of these

cells to their tissue of origin.

Additionally, other studies have determined that

modifications related to neoplastic gene methylation and altered

genomic imprinting are present in hiPSC lines, which can cause

malignant transformation and abnormal differentiation (106,107). Efforts to overcome the genomic

instability of hiPSCs centre on implementing two main approaches:

Genetic screening and the prevention of aberrations. These measures

are crucial in ensuring the accuracy and reproducibility of study

outcomes, which at the right time determine the feasibility of

translating hiPSCs to clinical applications.

As abnormalities have been found at various levels

of the genetic hierarchy, the evaluation of hiPSCs is recommended

based on three pillars: Karyotyping for the detection of balanced

aberrations, chromosomal microarray for the identification of copy

number variants and next generation sequencing for the

determination of single nucleotide variants or indels. These

genetic assessments are ideally conducted on each hiPSC line before

being used for research or therapeutic purposes. In the endeavours

to prevent aberrations, recent research has discovered that adding

antioxidant supplements to the culture media of hiPSCs can reduce

genomic instability (108,109). This has been attributed to the

alleviation of the oxidative stress cells are subjected to during

the reprogramming and early passage cultures. Furthermore, research

using small molecules to reprogram cells indicated that this

approach could generate hiPSCs without compromising genomic

stability (110). The mechanism

of action leading to this observation is believed to stem from

initiating the expression of the Zscan4 gene and the

prevention of DNA double-strand breaks (111).

As with the case of reprogramming hiPSCs from CB,

this strategy to repurpose CB to hiPSCs is viewed as advantageous

to prevent genomic instability, as it can exclude any genetic

aberrations accumulated from adult cells, is void of most

epigenetic imprinting and retains the cellular age of a newborn,

thus preserving telomeric length for greater proliferative

capacity. Furthermore, a protocol has been developed to use two

reprogramming factors, OCT3/4 and SOX2, to generate

CB-hiPSCs (72). A recent study

also disclosed that using improved lentiviral vectors with high

efficiency (2–14%) achieved enhancements such as optimized promoter

design, and incorporated genome stabilizers, such as Zscan4, which

could reduce reprogramming-induced mutations (112). This method generated CB-iPSCs

that harbour an average of only 1.3 coding mutations per cell line,

as determined by whole-exome sequencing. These findings

significantly improve the generation and manufacturing procedures

of hiPSCs, and serve as a step forward to bring hiPSCs and their

derivatives to clinical use.

One of the most promising prospects is the

realization of autologous CB-hiPSCs. This will allow patients to

benefit from their own reprogrammed cells, reducing the risk of

immune rejection and improving treatment outcomes. Additionally,

CB-iPSC lines derived from donors with rare blood groups could pave

the way to manufacture blood cells of unique characteristics as

differentiation technologies advance, meeting the demand for

transfusion in patients in need of rare blood (40). Furthermore, analyzing primitive

CB-hiPSCs across different developmental stages may provide

valuable insights into commonly acquired mutations, enhancing our

understanding of genetic changes in human disease development and

aging.

hiPSC technology offers great promising in

regenerative medicine, judging from the pluripotent capability of

the cells to differentiate and regenerate tissues, including those

that were previously considered impossible to regrow. Reprogramming

CB cells into hiPSCs is a viable strategy to expand their use to a

wider range of diseases and reinvent the banking business that

limits the current growth of CB banking services. The formation of

an iPSC haplobank based on the existing cryopreserved CB donations

could serve as a good cell source for regenerative therapy, not

only in the context of allogeneic transplantation, but also as the

foundation for use in autologous tissue regeneration or organ

engineering in future.

Not applicable.

Funding was provided by the Universiti Sains Malaysia Research

University (grant no. 1001/CIPPT/8011101) and a Cryocord Sdn Bhd

Matching Grant (no. 304/CIPPT/6501002/C130).

Not applicable.

FFR, YXY, JJT, SKC, ZG, AP, GCO, KLT, KYT and MNA

contributed to the review conception and design, interpretation and

writing. FFR, YXY and JJT wrote the first draft. SKC, ZG, AP and

JJT reviewed, revised and proofread the manuscript. All authors

read and approved the manuscript. Data authentication is not

applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

JJT received research grants from Cryocord Sdn Bhd

and ALPS Global Holding Bhd. Other authors declare the absence of

any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed

as a potential conflict of interest.

|

1

|

Gluckman E, Broxmeyer HA, Auerbach AD,

Friedman HS, Douglas GW, Devergie A, Esperou H, Thierry D, Socie G,

Lehn P, et al: Hematopoietic reconstitution in a patient with

Fanconi's anemia by means of umbilical-cord blood from an

HLA-identical sibling. N Engl J Med. 321:1174–1178. 1989.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Ballen KK, Verter F and Kurtzberg J:

Umbilical cord blood donation: Public or private? Bone Marrow

Transplant. 50:1271–1278. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

O'Donnell PV, Brunstein CG, Fuchs EJ,

Zhang MJ, Allbee-Johnson M, Antin JH, Leifer ES, Elmariah H,

Grunwald MR, Hashmi H, et al: Umbilical cord blood or

HLA-haploidentical transplantation: Real-world outcomes versus

randomized trial outcomes. Transplant Cell Ther. 28:109.e1–109.e8.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Álvarez-Palomo B, Veiga A, Raya A,

Codinach M, Torrents S, Ponce Verdugo L, Rodriguez-Aierbe C,

Cuellar L, Alenda R, Arbona C, et al: Public cord blood banks as a

source of starting material for clinical grade HLA-homozygous

induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cell Res Ther. 13:4082022.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Abberton K, Tian P, Elefanty A, Stanley E,

Leslie S, Youngson J, Diviney M, Holdsworth R, Tiedemann K, Little

M and Elwood N: Banked cord blood is a potential source of cells

for deriving induced pluripotent stem cell lines suitable for

cellular therapy. Stem Cells Transl Med. 7 (Suppl):S132018.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Hordyjewska A, Popiołek Ł and Horecka A:

Characteristics of hematopoietic stem cells of umbilical cord

blood. Cytotechnology. 67:387–396. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Faivre L, Couzin C, Boucher H, Domet T,

Desproges A, Sibony O, Bechard M, Vanneaux V, Larghero J and Cras

A: Associated factors of umbilical cord blood collection quality.

Transfusion. 58:520–531. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Nies C and Gottwald E: Artificial

hematopoietic stem cell niches-dimensionality matters. Adv Tissue

Eng Regen Med Open Access. 2:236–247. 2017.

|

|

9

|

Mayani H, Wagner JE and Broxmeyer HE: Cord

blood research, banking, and transplantation: Achievements,

challenges, and perspectives. Bone Marrow Transplant. 55:48–61.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Bowie MB, Kent DG, Dykstra B, McKnight KD,

McCaffrey L, Hoodless PA and Eaves CJ: Identification of a new

intrinsically timed developmental checkpoint that reprograms key

hematopoietic stem cell properties. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

104:5878–5882. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Jung JJ, Buisman SC and de Haan G: Do

hematopoietic stem cells get old? Leukemia. 31:529–531. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Jaing TH: Is the benefit-risk ratio for

patients with transfusion-dependent thalassemia treated by

unrelated cord blood transplantation favorable? Int J Mol Sci.

18:24722017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Roura S, Pujal JM, Gálvez-Montón C and

Bayes-Genis A: The role and potential of umbilical cord blood in an

era of new therapies: A review. Stem Cell Res Ther. 6:1232015.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Szabolcs P, Park KD, Reese M, Marti L,

Broadwater G and Kurtzberg J: Coexistent naïve phenotype and higher

cycling rate of cord blood T cells as compared to adult peripheral

blood. Exp Hematol. 31:708–714. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Chalmers IM, Janossy G, Contreras M and

Navarrete C: Intracellular cytokine profile of cord and adult blood

lymphocytes. Blood. 92:11–18. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Gluckman E, Rocha V, Arcese W, Michel G,

Sanz G, Chan KW, Takahashi TA, Ortega J, Filipovich A, Locatelli F,

et al: Factors associated with outcomes of unrelated cord blood

transplant: Guidelines for donor choice. Exp Hematol. 32:397–407.

2004. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Wagner JE and Gluckman E: Umbilical cord

blood transplantation: The first 20 years. Semin Hematol. 47:3–12.

2010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Kurtzberg J, Laughlin M, Graham ML, Smith

C, Olson JF, Halperin EC, Ciocci G, Carrier C, Stevens CE and

Rubinstein P: Placental blood as a source of hematopoietic stem

cells for transplantation into unrelated recipients. N Engl J Med.

335:157–166. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Laughlin MJ, Barker J, Bambach B, Koc ON,

Rizzieri DA, Wagner JE, Gerson SL, Lazarus HM, Cairo M, Stevens CE,

et al: Hematopoietic engraftment and survival in adult recipients

of umbilical-cord blood from unrelated donors. N Engl J Med.

344:1815–1822. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Broxmeyer HE, Lee MR, Hangoc G, Cooper S,

Prasain N, Kim YJ, Mallett C, Ye Z, Witting S, Cornetta K, et al:

Hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells, generation of induced

pluripotent stem cells, and isolation of endothelial progenitors

from 21- to 23.5-year cryopreserved cord blood. Blood.

117:4773–4777. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

World Marrow Donor Association, . Global

Trend Report. 2022.Retrieved from. https://wmda.info/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/30052023-GTR-2022-Summary-slides.pdfJuly

17–2023

|

|

22

|

Rocha V, Kabbara N, Ionescu I, Ruggeri A,

Purtill D and Gluckman E: Pediatric related and unrelated cord

blood transplantation for malignant diseases. Bone Marrow

Transplant. 44:653–659. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Herr AL, Kabbara N, Bonfim CMS, Teira P,

Locatelli F, Tiedemann K, Lankester A, Jouet JP, Messina C,

Bertrand Y, et al: Long-term follow-up and factors influencing

outcomes after related HLA-identical cord blood transplantation for

patients with malignancies: An analysis on behalf of Eurocord-EBMT.

Blood. 116:1849–1856. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Marks DI, Woo KA, Zhong X, Appelbaum FR,

Bachanova V, Barker JN, Brunstein CG, Gibson J, Kebriaei P, Lazarus

HM, et al: Unrelated umbilical cord blood transplant for adult

acute lymphoblastic leukemia in first and second complete

remission: A comparison with allografts from adult unrelated

donors. Haematologica. 99:322–328. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Eapen M, Rubinstein P, Zhang MJ, Stevens

C, Kurtzberg J, Scaradavou A, Loberiza FR, Champlin RE, Klein JP,

Horowitz MM and Wagner JE: Outcomes of transplantation of unrelated

donor umbilical cord blood and bone marrow in children with acute

leukaemia: A comparison study. Lancet. 369:1947–1954. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Eapen M, Wang T, Veys PA, Boelens JJ, St

Martin A, Spellman S, Bonfim CS, Brady C, Cant AJ, Dalle JH, et al:

Allele-level HLA matching for umbilical cord blood transplantation

for non-malignant diseases in children: A retrospective analysis.

Lancet Haematol. 4:e325–e333. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Eapen M, Klein JP, Ruggeri A, Spellman S,

Lee SJ, Anasetti C, Arcese W, Barker JN, Baxter-Lowe LA, Brown M,

et al: Impact of allele-level HLA matching on outcomes after

myeloablative single unit umbilical cord blood transplantation for

hematologic malignancy. Blood. 123:133–140. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Eapen M, Klein JP, Sanz GF, Spellman S,

Ruggeri A, Anasetti C, Brown M, Champlin RE, Garcia-Lopez J,

Hattersely G, et al: Effect of donor-recipient HLA matching at HLA

A, B, C, and DRB1 on outcomes after umbilical-cord blood

transplantation for leukaemia and myelodysplastic syndrome: A

retrospective analysis. Lancet Oncol. 12:1214–1221. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Passweg JR, Baldomero H, Chabannon C,

Basak GW, de la Cámara R, Corbacioglu S, Dolstra H, Duarte R, Glass

B, Greco R, et al: Hematopoietic cell transplantation and cellular

therapy survey of the EBMT: Monitoring of activities and trends

over 30 years. Bone Marrow Transplant. 56:1651–1664. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Dehn J, Spellman S, Hurley CK, Shaw BE,

Barker JN, Burns LJ, Confer DL, Eapen M, Fernandez-Vina M, Hartzman

R, et al: Selection of unrelated donors and cord blood units for

hematopoietic cell transplantation: Guidelines from the

NMDP/CIBMTR. Blood. 134:924–934. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Gragert L, Eapen M, Williams E, Freeman J,

Spellman S, Baitty R, Hartzman R, Rizzo JD, Horowitz M, Confer D

and Maiers M: HLA match likelihoods for hematopoietic stem-cell

grafts in the U.S. registry. N Engl J Med. 371:339–348. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Kanda J, Ichinohe T, Kato S, Uchida N,

Terakura S, Fukuda T, Hidaka M, Ueda Y, Kondo T, Taniguchi S, et

al: Unrelated cord blood transplantation vs related transplantation

with HLA 1-antigen mismatch in the graft-versus-host direction.

Leukemia. 27:286–294. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Laughlin MJ, Eapen M, Rubinstein P, Wagner

JE, Zhang MJ, Champlin RE, Stevens C, Barker JN, Gale RP, Lazarus

HM, et al: Outcomes after transplantation of cord blood or bone

marrow from unrelated donors in adults with leukemia. N Engl J Med.

351:2265–2275. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Politikos I, Davis E, Nhaissi M, Wagner

JE, Brunstein CG, Cohen S, Shpall EJ, Milano F, Scaradavou A and

Barker JN; American Society for Transplantation and Cellular

Therapy Cord Blood Special Interest Group, : Guidelines for cord

blood unit selection. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 26:2190–2196.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Rocha V and Gluckman E; Eurocord-Netcord

registry, European Blood and Marrow Transplant Group, : Improving

outcomes of cord blood transplantation: HLA matching, cell dose and

other graft- and transplantation-related factors. Br J Haematol.

147:262–274. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Ruggeri A: Optimizing cord blood

selection. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2019:522–531.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Querol S, Mufti GJ, Marsh SG, Pagliuca A,

Little AM, Shaw BE, Jeffery R, Garcia J, Goldman JM and Madrigal

JA: Cord blood stem cells for hematopoietic stem cell

transplantation in the UK: How big should the bank be?

Haematologica. 94:536–541. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Wagner JE, Barker JN, DeFor TE, Baker KS,

Blazar BR, Eide C, Goldman A, Kersey J, Krivit W, MacMillan ML, et

al: Transplantation of unrelated donor umbilical cord blood in 102

patients with malignant and nonmalignant diseases: influence of

CD34 cell dose and HLA disparity on treatment-related mortality and

survival. Blood. 100:1611–1618. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Barker JN, Scaradavou A and Stevens CE:

Combined effect of total nucleated cell dose and HLA match on

transplantation outcome in 1061 cord blood recipients with

hematologic malignancies. Blood. 115:1843–1849. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Tan JJ: Cord blood with low cell count:

Re-use, rather than discard. Single Cell Biol. 6:32017.

|

|

41

|

Magalon J, Maiers M, Kurtzberg J,

Navarrete C, Rubinstein P, Brown C, Schramm C, Larghero J,

Katsahian S, Chabannon C, et al: Banking or bankrupting: Strategies

for sustaining the economic future of public cord blood banks. PLoS

One. 10:e01434402015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Marotta D, Rao C and Fossati V: Human

induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) handling protocols:

Maintenance, expansion, and cryopreservation. In: Induced

pluripotent stem (iPS) cells: Methods and protocols. Springer; New

York, NY: pp. 1–15. 2021

|

|

43

|

Natunen S, Satomaa T, Pitkänen V, Salo H,

Mikkola M, Natunen J, Otonkoski T and Valmu L: The binding

specificity of the marker antibodies Tra-1–60 and Tra-1–81 reveals

a novel pluripotency-associated type 1 lactosamine epitope.

Glycobiology. 21:1125–1130. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Horwitz ME, Stiff PJ, Cutler C, Brunstein

C, Hanna R, Maziarz RT, Rezvani AR, Karris NA, McGuirk J, Valcarcel

D, et al: Omidubicel vs standard myeloablative umbilical cord blood

transplantation: Results of a phase 3 randomized study. Blood.

138:1429–1440. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Cohen S, Roy J, Lachance S, Delisle JS,

Marinier A, Busque L, Roy DC, Barabé F, Ahmad I, Bambace N, et al:

Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation using single UM171-expanded

cord blood: a single-arm, phase 1–2 safety and feasibility study.

Lancet Haematol. 7:e134–e145. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Stiff PJ, Montesinos P, Peled T, Landau E,

Goudsmid NR, Mandel J, Hasson N, Olesinski E, Glukhman E, Snyder

DA, et al: Cohort-controlled comparison of umbilical cord blood

transplantation using carlecortemcel-L, a single

progenitor-enriched cord blood, to double cord blood unit

transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 24:1463–1470. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Anand S, Thomas S, Hyslop T, Adcock J,

Corbet K, Gasparetto C, Lopez R, Long GD, Morris AK, Rizzieri DA,

et al: Transplantation of ex vivo expanded umbilical cord blood

(NiCord) decreases early infection and hospitalization. Biol Blood

Marrow Transplant. 23:1151–1157. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Horwitz ME, Wease S, Blackwell B,

Valcarcel D, Frassoni F, Boelens JJ, Nierkens S, Jagasia M, Wagner

JE, Kuball J, et al: Phase I/II study of stem-cell transplantation

using a single cord blood unit expanded ex vivo with nicotinamide.

J Clin Oncol. 37:367–374. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Wagner JE Jr, Brunstein CG, Boitano AE,

DeFor TE, McKenna D, Sumstad D, Blazar BR, Tolar J, Le C, Jones J,

et al: Phase I/II trial of stemregenin-1 expanded umbilical cord

blood hematopoietic stem cells supports testing as a stand-alone

graft. Cell Stem Cell. 18:144–155. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

de Lima M, McNiece I, Robinson SN, Munsell

M, Eapen M, Horowitz M, Alousi A, Saliba R, McMannis JD, Kaur I, et

al: Cord-blood engraftment with ex vivo mesenchymal-cell coculture.

N Engl J Med. 367:2305–2315. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Horwitz ME, Chao NJ, Rizzieri DA, Long GD,

Sullivan KM, Gasparetto C, Chute JP, Morris A, McDonald C,

Waters-Pick B, et al: Umbilical cord blood expansion with

nicotinamide provides long-term multilineage engraftment. J Clin

Invest. 124:3121–3128. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Delaney C, Heimfeld S, Brashem-Stein C,

Voorhies H, Manger RL and Bernstein ID: Notch-mediated expansion of

human cord blood progenitor cells capable of rapid myeloid

reconstitution. Nat Med. 16:232–236. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Saiyin T, Kirkham AM, Bailey AJM, Shorr R,

Pineault N, Maganti HB and Allan DS: Clinical outcomes of umbilical

cord blood transplantation using ex vivo expansion: A systematic

review and meta-analysis of controlled studies. Transplant Cell

Ther. 29:129.e1–129.e9. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Fares I, Chagraoui J, Gareau Y, Gingras S,

Rjean R, Csaszar E, Cohen S, Anne M, Zandstra PW and Sauvageau G:

UM171 is a novel and potent agonist of human hematopoietic stem

cell renewal. Blood. 122:7982013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Peled T, Shoham H, Aschengrau D, Yackoubov

D, Frei G, Rosenheimer GN, Lerrer B, Cohen HY, Nagler A, Fibach E

and Peled A: Nicotinamide, a SIRT1 inhibitor, inhibits

differentiation and facilitates expansion of hematopoietic

progenitor cells with enhanced bone marrow homing and engraftment.

Exp Hematol. 40:342–355.e1. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

de Lima M, McMannis J, Gee A, Komanduri K,

Couriel D, Andersson BS, Hosing C, Khouri I, Jones R, Champlin R,

et al: Transplantation of ex vivo expanded cord blood cells using

the copper chelator tetraethylenepentamine: a phase I/II clinical

trial. Bone Marrow Transplant. 41:771–778. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Mehta RS, Saliba RM, Cao K, Kaur I,

Rezvani K, Chen J, Olson A, Parmar S, Shah N, Marin D, et al: Ex

vivo mesenchymal precursor cell-expanded cord blood transplantation

after reduced-intensity conditioning regimens improves time to

neutrophil recovery. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 23:1359–1366.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

58

|

Passweg JR, Baldomero H, Bregni M, Cesaro

S, Dreger P, Duarte RF, Falkenburg JH, Kröger N, Farge-Bancel D,

Gaspar HB, et al: Hematopoietic SCT in Europe: Data and trends in

2011. Bone Marrow Transplant. 48:1161–1167. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

59

|

Iida M, Dodds A, Akter M, Srivastava A,

Moon JH, Dung PC, Bravo MR, Gyi AA, Jayathilake D, Liu K, et al:

The 2016 APBMT activity survey report: Trends in haploidentical and

cord blood transplantation in the Asia-Pacific region. Blood Cell

Ther. 4:20–28. 2021.

|

|

60

|

Niederwieser D, Baldomero H, Bazuaye N,

Bupp C, Chaudhri N, Corbacioglu S, Elhaddad A, Frutos C, Galeano S,

Hamad N, et al: One and a half million hematopoietic stem cell

transplants: Continuous and differential improvement in worldwide

access with the use of non-identical family donors. Haematologica.

107:1045–1053. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

61

|

Fuchs EJ, O'Donnell PV, Eapen M, Logan B,

Antin JH, Dawson P, Devine S, Horowitz MM, Horwitz ME, Karanes C,

et al: Double unrelated umbilical cord blood vs HLA-haploidentical

bone marrow transplantation: the BMT CTN 1101 trial. Blood.

137:420–428. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

62

|

Ruggeri A, Labopin M, Savani B,

Paviglianiti A, Blaise D, Volt F, Ciceri F, Bacigalupo A, Tischer

J, Chevallier P, et al: Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation

with unrelated cord blood or haploidentical donor grafts in adult

patients with secondary acute myeloid leukemia, a comparative study

from Eurocord and the ALWP EBMT. Bone Marrow Transplant.

54:1987–1994. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

63

|

Konuma T, Kanda J, Yamasaki S, Harada K,

Shimomura Y, Terakura S, Mizuno S, Uchida N, Tanaka M, Doki N, et

al: Single cord blood transplantation versus unmanipulated

haploidentical transplantation for adults with acute myeloid

leukemia in complete remission. Transplant Cell Ther.

27:334.e1–334.e11. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

64

|

Wieduwilt MJ, Metheny L, Zhang MJ, Wang

HL, Estrada-Merly N, Marks DI, Al-Homsi AS, Muffly L, Chao N,

Rizzieri D, et al: Haploidentical vs sibling, unrelated, or cord

blood hematopoietic cell transplantation for acute lymphoblastic

leukemia. Blood Adv. 6:339–357. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

65

|

Takahashi K and Yamanaka S: Induction of

pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast

cultures by defined factors. Cell. 126:663–676. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

66

|

Tarazi S, Aguilera-Castrejon A, Joubran C,

Ghanem N, Ashouokhi S, Roncato F, Wildschutz E, Haddad M, Oldak B,

Gomez-Cesar E, et al: Post-gastrulation synthetic embryos generated

ex utero from mouse naive ESCs. Cell. 185:3290–3306.e25. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

67

|

Abberton KM, McDonald TL, Diviney M,

Holdsworth R, Leslie S, Delatycki MB, Liu L, Klamer G, Johnson P

and Elwood NJ: Identification and Re-consent of existing cord blood

donors for creation of induced pluripotent stem cell lines for

potential clinical applications. Stem Cells Transl Med.

11:1052–1060. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

68

|

Ye Z, Zhan H, Mali P, Dowey S, Williams

DM, Jang YY, Dang CV, Spivak JL, Moliterno AR and Cheng L:

Human-induced pluripotent stem cells from blood cells of healthy

donors and patients with acquired blood disorders. Blood.

114:5473–5480. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

69

|

Takenaka C, Nishishita N, Takada N, Jakt

LM and Kawamata S: Effective generation of iPS cells from CD34+

cord blood cells by inhibition of p53. Exp Hematol. 38:154–162.

2010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

70

|

Haase A, Olmer R, Schwanke K, Wunderlich

S, Merkert S, Hess C, Zweigerdt R, Gruh I, Meyer J, Wagner S, et

al: Generation of induced pluripotent stem cells from human cord

blood. Cell Stem Cell. 5:434–441. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

71

|

Dorn I, Klich K, Arauzo-Bravo MJ, Radstaak

M, Santourlidis S, Ghanjati F, Radke TF, Psathaki OE, Hargus G,

Kramer J, et al: Erythroid differentiation of human induced

pluripotent stem cells is independent of donor cell type of origin.

Haematologica. 100:32–41. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

72

|

Giorgetti A, Montserrat N, Rodriguez-Piza

I, Azqueta C, Veiga A and Izpisúa Belmonte JC: Generation of

induced pluripotent stem cells from human cord blood cells with

only two factors: Oct4 and Sox2. Nat Protoc. 5:811–820. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

73

|

Chou BK, Mali P, Huang X, Ye Z, Dowey SN,

Resar LM, Zou C, Zhang YA, Tong J and Cheng L: Efficient human iPS

cell derivation by a non-integrating plasmid from blood cells with

unique epigenetic and gene expression signatures. Cell Res.

21:518–529. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

74

|

Ban H, Nishishita N, Fusaki N, Tabata T,

Saeki K, Shikamura M, Takada N, Inoue M, Hasegawa M, Kawamata S and

Nishikawa S: Efficient generation of transgene-free human induced

pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) by temperature-sensitive Sendai

virus vectors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 108:14234–14239. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

75

|

Arellano-Viera E, Zabaleta L, Castaño J,

Azkona G, Carvajal-Vergara X and Giorgetti A: Generation of two

transgene-free human iPSC lines from CD133+ cord blood

cells. Stem Cell Res. 36:1014102019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

76

|

Tian P, Elefanty A, Stanley EG, Durnall

JC, Thompson LH and Elwood NJ: Creation of GMP-compliant iPSCs from

banked umbilical cord blood. Front Cell Dev Biol. 10:8353212022.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

77

|

Gao X, Yourick JJ and Sprando RL:

Comparative transcriptomic analysis of endothelial progenitor cells

derived from umbilical cord blood and adult peripheral blood:

Implications for the generation of induced pluripotent stem cells.

Stem Cell Res. 25:202–212. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

78

|

Gao X, Yourick JJ and Sprando RL:

Generation of nine induced pluripotent stem cell lines as an ethnic

diversity panel. Stem Cell Res. 31:193–196. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

79

|

Wang Q, Wang Y, Chang C, Ma F, Peng D,

Yang S, An Y, Deng Q, Wang Q, Gao F, et al: Comparative analysis of

mesenchymal stem/stromal cells derived from human induced

pluripotent stem cells and the cognate umbilical cord mesenchymal

stem/stromal cells. Heliyon. 9:e126832023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

80

|

Takahashi K, Tanabe K, Ohnuki M, Narita M,

Ichisaka T, Tomoda K and Yamanaka S: Induction of pluripotent stem

cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell.

131:861–872. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

81

|

Kane NM, Nowrouzi A, Mukherjee S, Blundell

MP, Greig JA, Lee WK, Houslay MD, Milligan G, Mountford JC, von

Kalle C, et al: Lentivirus-mediated reprogramming of somatic cells

in the absence of transgenic transcription factors. Mol Ther.

18:2139–2145. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

82

|

Shadid M, Shrestha A and Malik P:

Preclinical safety assessment of modified gamma globin lentiviral

vector-mediated autologous hematopoietic stem cell gene therapy for

hemoglobinopathies. PLoS One. 19:e03067192024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

83

|

Thompson AA, Walters MC, Kwiatkowski J,

Rasko JEJ, Ribeil JA, Hongeng S, Magrin E, Schiller GJ, Payen E,

Semeraro M, et al: Gene therapy in patients with

transfusion-dependent β-thalassemia. N Engl J Med. 378:1479–1493.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

84

|

Kunitomi A, Hirohata R, Arreola V, Osawa

M, Kato TM, Nomura M, Kawaguchi J, Hara H, Kusano K, Takashima Y,

et al: Improved Sendai viral system for reprogramming to naive

pluripotency. Cell Rep Methods. 2:1003172022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

85

|

Kunitomi A, Hirohata R, Osawa M, Washizu

K, Arreola V, Saiki N, Kato TM, Nomura M, Kunitomi H, Ohkame T, et

al: H1FOO-DD promotes efficiency and uniformity in reprogramming to

naive pluripotency. Stem Cell Reports. 19:710–728. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

86

|

Yoshioka N, Gros E, Li HR, Kumar S, Deacon

DC, Maron C, Muotri AR, Chi NC, Fu XD, Yu BD and Dowdy SF:

Efficient generation of human iPSCs by a synthetic self-replicative

RNA. Cell Stem Cell. 13:246–254. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

87

|

Judson RL, Babiarz JE, Venere M and

Blelloch R: Embryonic stem cell-specific microRNAs promote induced

pluripotency. Nat Biotechnol. 27:459–461. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

88

|

Hou P, Li Y, Zhang X, Liu C, Guan J, Li H,

Zhao T, Ye J, Yang W, Liu K, et al: Pluripotent stem cells induced

from mouse somatic cells by small-molecule compounds. Science.

341:651–654. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

89

|

Qin J, Zhang J, Jiang J, Zhang B, Li J,

Lin X, Wang S, Zhu M, Fan Z, Lv Y, et al: Direct chemical

reprogramming of human cord blood erythroblasts to induced

megakaryocytes that produce platelets. Cell Stem Cell.

29:1229–1245.e7. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

90

|

Kajiwara M, Aoi T, Okita K, Takahashi R,

Inoue H, Takayama N, Endo H, Eto K, Toguchida J, Uemoto S and

Yamanaka S: Donor-dependent variations in hepatic differentiation

from human-induced pluripotent stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

109:12538–12543. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

91

|

Kim K, Zhao R, Doi A, Ng K, Unternaehrer

J, Cahan P, Huo H, Loh YH, Aryee MJ, Lensch MW, et al: Donor cell

type can influence the epigenome and differentiation potential of

human induced pluripotent stem cells. Nat Biotechnol. 29:1117–1119.

2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

92

|

Sanchez-Freire V, Lee AS, Hu S, Abilez OJ,

Liang P, Lan F, Huber BC, Ong SG, Hong WX, Huang M and Wu JC:

Effect of human donor cell source on differentiation and function

of cardiac induced pluripotent stem cells. J Am Coll Cardiol.

64:436–448. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

93

|

Streckfuss-Bömeke K, Wolf F, Azizian A,

Stauske M, Tiburcy M, Wagner S, Hübscher D, Dressel R, Chen S,

Jende J, et al: Comparative study of human-induced pluripotent stem

cells derived from bone marrow cells, hair keratinocytes, and skin

fibroblasts. Eur Heart J. 34:2618–2629. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

94

|

Kyttälä A, Moraghebi R, Valensisi C,

Kettunen J, Andrus C, Pasumarthy KK, Nakanishi M, Nishimura K,

Ohtaka M, Weltner J, et al: Genetic variability overrides the

impact of parental cell type and determines iPSC differentiation

potential. Stem Cell Reports. 6:200–212. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

95

|

Lo Sardo V, Ferguson W, Erikson GA, Topol

EJ, Baldwin KK and Torkamani A: Influence of donor age on induced

pluripotent stem cells. Nat Biotechnol. 35:69–74. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

96

|

Chang CJ, Mitra K, Koya M, Velho M,

Desprat R, Lenz J and Bouhassira EE: Production of embryonic and

fetal-like red blood cells from human induced pluripotent stem

cells. PLoS One. 6:e257612011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

97

|

Lee S, Huh JY, Turner DM, Lee S, Robinson

J, Stein JE, Shim SH, Hong CP, Kang MS, Nakagawa M, et al:

Repurposing the cord blood bank for haplobanking of HLA-homozygous

iPSCs and their usefulness to multiple populations. Stem Cells.

36:1552–1566. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

98

|

Shin S, Song EY, Kwon YW, Oh S, Park H,

Kim NH and Roh EY: Usefulness of the hematopoietic stem cell donor

pool as a source of HLA-homozygous induced pluripotent stem cells

for haplobanking: Combined analysis of the cord blood inventory and

bone marrow donor registry. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant.

26:e202–e208. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

99

|

Yoshida S, Kato TM, Sato Y, Umekage M,

Ichisaka T, Tsukahara M, Takasu N and Yamanaka S: A clinical-grade

HLA haplobank of human induced pluripotent stem cells matching

approximately 40% of the Japanese population. Med. 4:51–66.e10.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

100

|

Alvarez-Palomo B, Garcia-Martinez I,

Gayoso J, Raya A, Veiga A, Abad ML, Eiras A, Guzmán-Fulgencio M,

Luis-Hidalgo M, Eguizabal C, et al: Evaluation of the Spanish

population coverage of a prospective HLA haplobank of induced

pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cell Res Ther. 12:2332021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

101

|

Sullivan S, Ginty P, McMahon S, May M,

Solomon SL, Kurtz A, Stacey GN, Bennaceur Griscelli A, Li RA, Barry

J, et al: The global alliance for iPSC therapies (GAiT). Stem Cell

Res. 49:1020362020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

102

|

Meissner TB, Schulze HS and Dale SM:

Immune editing: Overcoming immune barriers in stem cell

transplantation. Curr Stem Cell Rep. 8:206–218. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

103

|

Deuse T, Hu X, Gravina A, Wang D,

Tediashvili G, De C, Thayer WO, Wahl A, Garcia JV, Reichenspurner

H, et al: Hypoimmunogenic derivatives of induced pluripotent stem

cells evade immune rejection in fully immunocompetent allogeneic

recipients. Nat Biotechnol. 37:252–258. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

104

|

Han X, Wang M, Duan S, Franco PJ, Kenty

JH, Hedrick P, Xia Y, Allen A, Ferreira LMR, Strominger JL, et al:

Generation of hypoimmunogenic human pluripotent stem cells. Proc

Natl Acad Sci USA. 116:10441–10446. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

105

|

Popp B, Krumbiegel M, Grosch J, Sommer A,

Uebe S, Kohl Z, Plötz S, Farrell M, Trautmann U, Kraus C, et al:

Need for high-resolution genetic analysis in iPSC: Results and

lessons from the ForIPS consortium. Sci Rep. 8:172012018.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

106

|

Ohm JE, Mali P, Van Neste L, Berman DM,

Liang L, Pandiyan K, Briggs KJ, Zhang W, Argani P, Simons B, et al:

Cancer-related epigenome changes associated with reprogramming to

induced pluripotent stem cells. Cancer Res. 70:7662–7673. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

107

|

Pick M, Stelzer Y, Bar-Nur O, Mayshar Y,

Eden A and Benvenisty N: Clone- and gene-specific aberrations of

parental imprinting in human induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem

Cells. 27:2686–2690. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

108

|

Ji J, Sharma V, Qi S, Guarch ME, Zhao P,

Luo Z, Fan W, Wang Y, Mbabaali F, Neculai D, et al: Antioxidant

supplementation reduces genomic aberrations in human induced

pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cell Reports. 2:44–51. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

109

|

Luo L, Kawakatsu M, Guo CW, Urata Y, Huang

WJ, Ali H, Doi H, Kitajima Y, Tanaka T, Goto S, et al: Effects of

antioxidants on the quality and genomic stability of induced

pluripotent stem cells. Sci Rep. 4:37792014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

110

|

Park HS, Hwang I, Choi KA, Jeong H, Lee JY

and Hong S: Generation of induced pluripotent stem cells without

genetic defects by small molecules. Biomaterials. 39:47–58. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

111

|

Akiyama T, Ishiguro KI, Chikazawa N, Ko

SBH, Yukawa M and Ko MSH: ZSCAN4-binding motif-TGCACAC is conserved

and enriched in CA/TG microsatellites in both mouse and human

genomes. DNA Res. 31:dsad0292024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

112

|

Su RJ, Yang Y, Neises A, Payne KJ, Wang J,

Viswanathan K, Wakeland EK, Fang X and Zhang XB: Few single

nucleotide variations in exomes of human cord blood induced

pluripotent stem cells. PLoS One. 8:e599082013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

113

|

Butler MG and Menitove JE: Umbilical cord

blood banking: An update. J Assist Reprod Genet. 28:669–676. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar

|