Introduction

Sepsis is a clinical syndrome of systemic

dysfunctional metabolism triggered by infection (1). There are ~19 million cases of

sepsis worldwide each year, with a mortality rate of 30%. Surveys

have indicated that the incidence of sepsis and its morbidity rate

are increasing annually (2,3).

Sepsis can lead to functional impairment of multiple organs, with

the heart being the most susceptible, accounting for 16-65% of

cases and being the primary cause of death in patients with sepsis

(4-6). The clinical term for sepsis

accompanied by cardiac dysfunction is sepsis-induced cardiomyopathy

(SIC) (7). SIC is a serious

complication characterized by myocardial damage directly caused by

the production of large amounts of inflammatory factors in the body

after infection, by myocardial systolic depression, or by reduced

cardiac output due to impaired myocardial energy metabolism

(8).

Patients with sepsis usually have altered levels or

functions of hormones, including thyroid hormones, insulin and

adrenal glucocorticoids; low levels of triiodothyronine (T3) in

particular are highly associated with mortality in patients with

sepsis (9). Studies have shown

that alterations in thyroid hormone levels or functions are often

associated with liver and cardiovascular diseases (10,11). Thyroid hormones are synthesized

by thyroid follicular epithelial cells and are stored in the

follicular lumen (12); two

biologically active thyroid hormones circulate in the body, namely,

thyroxine and T3, with T3 being more active and having a greater

affinity for receptors in the nuclei of target organs (13). The heart is one of the most

important target organs for the action of thyroid hormones.

Notably, thyroid hormones regulate calcium homeostasis in

cardiomyocytes by modulating calcium channels and pumps,

influencing physiological processes such as cardiomyocyte

electrophysiology, mechanical contraction and energy metabolism

(14,15).

The pathogenesis of SIC is complex and includes

myocardial cell damage, increased release of proinflammatory

factors, mitochondrial dysfunction and an imbalance in calcium

homeostasis (16). Intracellular

calcium cycling serves as a central regulator of myocardial

contraction and diastole, ensuring proper myocardial cell function

(17,18). The sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR)

releases calcium ions into the cell cytoplasm to induce contraction

and then recycles calcium ions back into the SR via the SR calcium

ATPase (SERCA2) to achieve myocyte relaxation (19,20). This complex process is essential

for excitation-contraction coupling to balance Ca2+

homeostasis, and abnormal Ca2+ handling caused by SR

dysfunction in cardiomyocytes results in systolic dysfunction.

Phospholamban (PLN), which is located in the SR, modulates SERCA2

activity and participates in intracellular calcium recycling,

thereby influencing myocardial contractile and diastolic functions

(21,22). When PLN binds to SERCA2, it

decreases the affinity of the enzyme for calcium ions, preventing

calcium re-entry into the SR and causing its accumulation in the

cytoplasm. Phosphorylated-PLN fails to combine with SERCA2,

facilitating calcium recycling from the cytoplasm to the SR. Thus,

PLN maintains intracellular calcium homeostasis and thereby serves

an important regulatory role in cardiac systolic-diastolic function

(23-25). Numerous studies have indicated

that, in addition to causing disturbances in myocardial contraction

and relaxation, intracellular calcium overload can lead to various

adverse effects, such as arrhythmia, cardiomyocyte apoptosis and

mitochondrial dysfunction (26,27).

Current research on the role of PLN in SIC has

focused primarily on its regulation of cardiac contractile

function. Protein kinase A and the state of PLN itself, such as its

protein pentameric form or monomers and the SERCA-PLN complex can

influence the extent of PLN phosphorylation, thereby affecting

cardiac function (28,29). Additionally, it has been reported

that thyroid hormones are important regulatory factors at the

transcriptional level of SERCA2, indirectly affecting the function

of PLN by influencing the activity and expression of SERCA2 in

cardiac muscle (30). However,

in SIC, the specific molecular mechanism underlying the interaction

between thyroid hormones and PLN has been largely overlooked.

Research investigating the relationship between low T3 syndrome

occurring in sepsis and calcium homeostasis is scarce (11).

Given the aforementioned findings, it may be

hypothesized that T3 mitigates SIC by reducing PLN expression and

calcium overload. The present study aimed to explore the

relationship between low levels of T3 and PLN in SIC, and to

further elucidate the specific mechanisms by which T3 regulates the

expression of PLN. Additionally, the study endeavored to assess the

clinical application of PLN in the context of SIC.

Materials and methods

Clinical patients and healthy

controls

Patients who met the clinical diagnostic criteria

for SIC and those who met the diagnostic criteria for sepsis on the

day of hospital admission were included in the disease group and

the disease control group, respectively. Healthy control group

subjects were recruited from the general population upon completion

of patient recruitment from Children's Hospital of Chongqing

Medical University (Chongqing, China). The mean age of the three

groups (healthy, Sepsis and SIC) was as follows: 6.08 (1-15), 2.67 (0-12) and 4.3 (0-16) years,

respectively. The sex proportion (males/females) for each of the

three groups was 60.0/40.0%. Patients and controls with malignant

tumors, organ transplants, chronic viral infections (hepatitis,

HIV), cirrhosis, chronic renal insufficiency or autoimmune

diseases, and those who had used immunosuppressive drugs within the

past 28 weeks were excluded from the study. A total of 33 children

with SIC and 30 children with sepsis were included in the disease

group and the disease control group, respectively, on the day of

admission from Children's Hospital of Chongqing Medical University.

Clinical data including vital signs, routine blood parameters,

cardiac enzyme profiles, and liver and kidney function test data,

were recorded. In addition, 23 healthy children were recruited as

controls at the Physical Examination Center of the Children's

Hospital of Chongqing Medical University. The complete date range

for patient recruitment was from December 2021 to October 2022.

Written informed consent was obtained from the parents of all of

the patients in accordance with the ethical standards of The

Declaration of Helsinki. The present study protocol was approved by

the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Children's Hospital

of Chongqing Medical University (approval no. 2021-353).

Establishment of an animal model

The SIC model was established via the

intraperitoneal injection of lipopolysaccharide (LPS; cat. no.

L8880; Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.)

dissolved in sterile saline at a dose of 20 mg/kg. A total of 18

male C57BL/6J mice (age, 6-8 weeks; weight, 18-20 g) were purchased

from the Animal Experiment Center of Chongqing Medical University

(SCXK: 2022-0010). All of the mice were maintained under standard

housing conditions: Temperature, 22±1°C; humidity, 50%; 12-h

dark/light cycle; ad libitum access to food and water. After

3 days of acclimation, 18 mice were randomly divided into the

following three groups: The sham group (n=6), the LPS experimental

group (n=6) and the LPS + T3 experimental group (n=6). The sham

group and LPS experimental group were injected intraperitoneally

with saline or LPS solution, respectively, while the LPS + T3 group

was pretreated with 80 mg/kg T3 (cat. no. T162132; Shanghai Aladdin

Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd.) 24 h before injection with LPS.

Since the half-life of T3 has been reported to be 24 h (31), and due to the survival status of

the experimental animals after modeling, the duration of the

experiment was 24 h. Animal healthy behavior and the humane

endpoints, which were defined as a body temperature <33°C,

inactivity of >3 h and/or a drop in weight of >20% of their

original body weight, were monitored every 6 h during the study.

Anesthesia and specific housing conditions were used during

handling and intraperitoneal injection with LPS to ensure minimal

pain, suffering and distress to animals. Each mouse was deeply

anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of 10% chloral

hydrate (350 mg/kg) prior to intraperitoneal injection with LPS,

and no mouse exhibited signs of peritonitis following the

administration of 10% chloral hydrate. Following intraperitoneal

injection of LPS, the mice began to exhibit signs of infection,

including ruffled fur, decreased activity, hunched posture and

tachypnea. Subsequently, at 24 h post-injection, the 6 mice from

the LPS group and the 6 mice from the LPS + T3 group were

sacrificed. The mice in the sham group were euthanized 24 h after

intraperitoneal injection of saline. The mice were euthanized by

inhalation of 30% CO2 for 5 min and death was verified

by cervical dislocation. No moving, no breathing and pupil dilation

of mice were assessed to confirm death. At the end of the

experiment and after the mice were sacrificed, blood was collected

from the retro-orbital vein and myocardial tissue samples were

collected. The present study followed the animal experimentation

guidelines (32) and was

approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of the Children's Hospital

of Chongqing Medical University (approval no.

CHCMU-IACUC20210114036).

Establishment of cell models

H9C2 cells, provided by The Cell Bank of Type

Culture Collection of The Chinese Academy of Sciences, were

cultured in DMEM (4.5 g/l glucose; Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.) in a 5% CO2 humidified

incubator. The cells were divided into four groups: The control

group, the LPS group, the LPS + T3 group and the LPS + SP600125

(SP; MedChemExpress) group. The concentration range was established

according to the literature (33,34), and 80 ng/ml T3 and 10 µM

SP (JNK inhibitor) were selected as the working concentrations The

cells in the control group were cultured in complete medium

containing 10% fetal bovine serum; the cells in the LPS group were

incubated for 24 h after they reached 75% confluence, and the

medium was then replaced with complete DMEM containing 10

µg/ml LPS at 37°C for 24 h to construct an in vitro

model of SIC. In addition, the LPS + T3 and LPS + SP groups were

pretreated with T3 for 24 h before LPS treatment or with SP for 30

min at 37°C, respectively. All of the cell experiments were

independently repeated at least in triplicate.

Detection of serological indicators

Blood samples from patients, as well as mouse blood

obtained from the orbital venous plexus, were centrifuged at 1,000

× g at room temperature for 15 min. According to the manufacturers'

instructions, the levels of PLN, cardiac troponin I (cTnI), and T3

in the serum were determined via human-derived PLN (cat. no.

JL15150; Shanghai Jianglai Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) and T3 (cat.

no. JL13028; Shanghai Jianglai Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) ELISA kits,

and mouse-derived cTnI (cat. no. E-EL-M1203c; Wuhan Elabscience

Biotechnology Co., Ltd.), PLN (cat. no. JL24496; Shanghai Jianglai

Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) and T3 (cat. no. E-EL-0079c;Wuhan

Elabscience Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) ELISA kits. Albumin (ALB) and

creatinine (CREA) were assessed using an automatic biochemical

analyzer (Roche Cobas c701; Roche Diagnostics), procalcitonin (PCT)

was assessed using an automatic chemiluminescence immunoassay

analyzer (Cobas pro e801; Roche Diagnostics), and brain natriuretic

peptide (BNP) was assessed using another automatic

chemiluminescence immunoassay analyzer (Atellica IM 1600;

Siemens).

Histological analysis

After the mice were treated for 24 h to establish an

in vivo model, they were sacrificed with 30% CO2.

The heart tissues were collected, rinsed with isotonic saline, and

fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 12 h at room temperature.

Subsequently, the tissues were dehydrated, embedded in paraffin,

and were sectioned (8 µm) and stained with hematoxylin for 6

min and 1% eosin for 1 min, or Masson for 5 min at room

temperature. The sections were then placed under a light microscope

for observation and images were captured.

Cell viability and drug toxicity

assay

Cell viability and drug toxicity were measured using

the Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) assay. The cells

(4×103/well) were placed in 96-well plates and were

incubated according to the experimental design. Subsequently, 100

µl CCK-8 assay reagent (cat. no. M4839; AbMole BioScience)

was diluted 10 times with serum-free culture medium and was

incubated with the cells for 3 h. The optical density (OD) value

was then detected at 450 nm using a microplate reader (Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.). All OD values were normalized by

converting them to a percentage of the mean control value.

Apoptosis assay

An apoptosis assay kit (cat. no. 556547; BD

Biosciences) was used to detect apoptosis according to the

manufacturer's instructions. All of the cells (including those in

suspension) were collected as a precipitate, and 100 µl 1X

binding buffer diluted in distilled water was added to resuspend

the cell pellet. Subsequently, 5 µl FITC and 5 µl

propidium iodide were added and vortexed sequentially, after which

the samples were incubated at room temperature in the dark for 30

min. Finally, 400 µl 1X binding buffer was added to each

tube, apoptosis was examined by flow cytometry (FACSCanto II;

Becton, Dickinson and Company) and the data were analyzed using

FlowJo (software version 10.8; FlowJo LLC).

Crystal violet staining

The cells were placed in 24-well plates

(5×104/well) and were treated for 24 h. The cells were

then fixed with 1 ml 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min and were

subjected to staining with crystal violet (cat. no. C0121; Beyotime

Institute of Biotechnology) on a shaker at room temperature for 15

min. The cells were rinsed 3-5 times with PBS, air-dried, were

placed under a light microscope for observation and images were

captured. In addition, the OD value was detected at 570 nm using a

microplate reader. All OD values were normalized by converting them

to a percentage of the mean control value.

Calcium assay

Intracellular calcium levels were detected using the

calcium fluorescent probe Fluo-4AM (cat. no. S1060; Beyotime

Institute of Biotechnology). The Fluo-4AM working solution (5

µM) was prepared according to the manufacturer's

instructions, and the cells were incubated with it for 40 min at

37°C in the dark for fluorescent probe loading. The staining

solution was then discarded, and PBS was added and the cells were

incubated for a further 20 min. The cells were then observed and

images were captured under a confocal microscope, and the mean

fluorescence intensity was detected via flow cytometry (FACSCanto

II) and the data were analyzed using FlowJo (software version

10.8). The values of the experimental groups were normalized to

those of the control group.

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) assay

A ROS assay was performed using DHE (cat. no.

KGAF019; Nanjing KeyGen Biotech Co., Ltd.) and Hoechst 33258 (cat.

no. C1011; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) fluorescent probe

kits according to the manufacturers' instructions. Briefly, the

cells were incubated with 5 µM DHE for 30 min at 37°C in the

dark. To measure the levels of ROS, fluorescence images of the

cells were captured under a confocal fluorescence microscope, or

the cell suspension was collected in test tubes, and the mean

fluorescence intensity of DHE was measured by flow cytometry

(FACSCanto II) and the data were analyzed using FlowJo (software

version 10.8). The values of the experimental groups were

normalized to those of the control group.

Plasmid construction and

transfection

The pcDNA3.1(+) plasmid overexpressing c-Jun

contained the coding sequence region of the rat c-Jun gene from

NCBI (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) and

was constructed by Beijing Biomed Gene Technology Co., Ltd. An

empty pcDNA3.1(+) plasmid was used as a negative control. The

overexpression plasmids (900 ng/µl) were transfected into

H9C2 cells (80% confluence) using the PolyJet™ transfection reagent

(cat. no. SL100688; SignaGen Laboratories), according to the

manufacturer's instructions, at 37°C for 6 h. The DNA and PolyJet

were diluted separately at a ratio of 3:1 in serum-free DMEM,

mixed, incubated for 15 min at room temperature and then added to

the cell culture medium. After 12-18 h of transfection, the medium

containing the PolyJet/DNA complex was removed and replaced with

fresh serum-containing complete medium.

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR

(RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted from cell samples or

myocardial tissue samples using an RNA extraction kit (cat. no.

9109; Takara Bio, Inc.), and single-stranded complementary DNA was

synthesized using an RT kit (cat. no. RK20429; ABclonal Biotech

Co., Ltd.). β-actin was selected as the reference gene according to

previous studies (35,36). qPCR was performed using SYBR qPCR

reagents (cat. no. RK21203; ABclonal Biotech Co., Ltd.), and the

values of the average quantification cycle (Cq) were normalized to

the expression of β-actin; finally, the relative mRNA expression

levels were determined using the 2−ΔΔCq method (37). The values of the experimental

groups were normalized to those of the control group. The following

qPCR cycling conditions were used: 3 min at 95°C, followed by 45

cycles at 95°C for 30 min, 95°C for 5 sec and 60°C for 30 sec. The

primer details are shown in Table

I.

| Table IQuantitative PCR primer

sequences. |

Table I

Quantitative PCR primer

sequences.

| Name | Primer sequence,

5′-3′ |

|---|

| PLN-Mouse | F:

CCAAGACAGAAGCAGGTGAAGAGAC |

| R:

AAAGTTGACAACAGGCAGCCAAATG |

| PLN-Rat | F:

TTACTCGCTCGGCTATCAGGAGAG |

| R:

ACAATGATGCAGATCAGCAGCAGAC |

| SERCA2-Mouse | F:

GAATTAAGCCCTTCAGCCCAGAGAG |

| R:

AGCATCATTCACACCATCACCAGTC |

| IL-6-Rat | F:

AGTTGCCTTCTTGGGACTGATGTTG |

| R:

GGTATCCTCTGTGAAGTCTCCTCTCC |

| TNF-α-Rat | F:

ATGGGCTCCCTCTCATCAGTTCC |

| R:

CCTCCGCTTGGTGGTTTGCTAC |

| c-Jun-Rat | F:

CTTCTACGACGATGCCCTCAACG |

| R:

AGGTTCAAGGTCATGCTCTGCTTC |

| β-actin-Mouse | F:

CTGAGAGGGAAATCGTGCGTGAC |

| R:

ACCGCTCGTTGCCAATAGTGATG |

| β-actin-Rat | F:

GCTGTGCTATGTTGCCCTAGACTTC |

| R:

GGAACCGCTCATTGCCGATAGTG |

Western blotting (WB)

Proteins were extracted from cells and myocardial

tissues according to the instructions of the protein extraction kit

(cat. no. KGP2100; Nanjing KeyGen Biotech Co., Ltd.), and their

concentrations were determined with a BCA assay kit (cat. no.

KGP902; Nanjing KeyGen Biotech Co., Ltd.). Proteins (60 µg)

were separated by SDS-PAGE on 10 or 15% gels and were transferred

to PVDF membranes, after which the protein samples were blocked

with 5% skim milk powder for 2 h at room temperature. The membranes

were subsequently incubated with the primary antibodies at 4°C

overnight and with an HRP-conjugated secondary antibody for 1 h at

room temperature. Finally, the blots were rinsed three times with

TBS-0.1% Tween (TBST; 5 min each wash) and 200 µl Pico ECL

Ultrasensitive Substrate Chemiluminescent Detection Kit (cat. no.

PA134-01; Beijing Biomed Gene Technology Co;) was added to scan the

blot using the ChemiDoc MP imaging system (Bio-Rad Laboratories,

Inc.), and the band intensities were measured using ImageJ software

(v1.54; National Institutes of Health). The values of the

experimental groups were normalized to those of the control group.

Each experiment was performed in triplicate, and all samples were

normalized to β-actin. The following antibodies diluted with TBST

(1:500) were used: Rabbit anti-PLN (cat. no. ab219626; Abcam),

rabbit anti-phosphorylated (p)-PLN (Ser16) (cat. no. AP0907;

ABclonal Biotech Co., Ltd.), rabbit anti-p-PLN (Thr17) (cat. no.

AF7278; Affinity Biosciences), rabbit anti-SERCA2 (cat. no. 381667;

ZENBIO), rabbit anti-JNK (cat. no. ET1601-28; HUABIO), rabbit

anti-p-JNK (cat. no. ET1609-42; HUABIO), rabbit anti-c-Jun (cat.

no. ET1608-3; HUABIO), rabbit anti-p-c-Jun (cat. no. ET1608-4;

HUABIO), mouse anti-β-actin (cat. no. R23613; ZENBIO), goat

anti-rabbit-HRP (cat. no. SA00001-2 Proteintech Group, Inc.) and

goat anti-mouse-HRP (cat. no. SA00001-1; Proteintech Group,

Inc.).

Proteomics analyses

The cardiac tissues from three mice in the sham and

LPS groups were collected and used for proteomic analyses. The

essential steps involved in tandem mass tagging (TMT) proteomics

analysis are protein extraction, trypsin digestion, TMT labeling,

HPLC fractionation, LC-MS/MS analysis and data search, which were

performed as previously described (38). The proteomics analysis in the

present study was facilitated by the Jingjie PTM Bioinformatics

Team (Jingjie PTM BioLab Co. Ltd.).

Statistical analysis

Experiments were repeated at least three time,

unless otherwise stated. Data are presented as the mean ± SD and

were statistically analyzed using GraphPad Prism 8.0 (Dotmatics)

and SPSS 27.0 (IBM Corp.) software. Comparisons between two groups

were analyzed using unpaired Students' t-test or Welch's t-test on

the basis of the results of the homogeneity test of variance (F

test). Differences among three or more groups were analyzed using

one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey's test for pairwise

comparisons or Dunnett's test for comparing each group to a control

group. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analyses, and

Spearman correlation analyses between PLN, and serum ALB, PCT and

CREA, were performed in SPSS 27.0. P<0.05 was considered to

indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Serum T3 levels are significantly

negatively correlated with myocardial PLN levels in sepsis

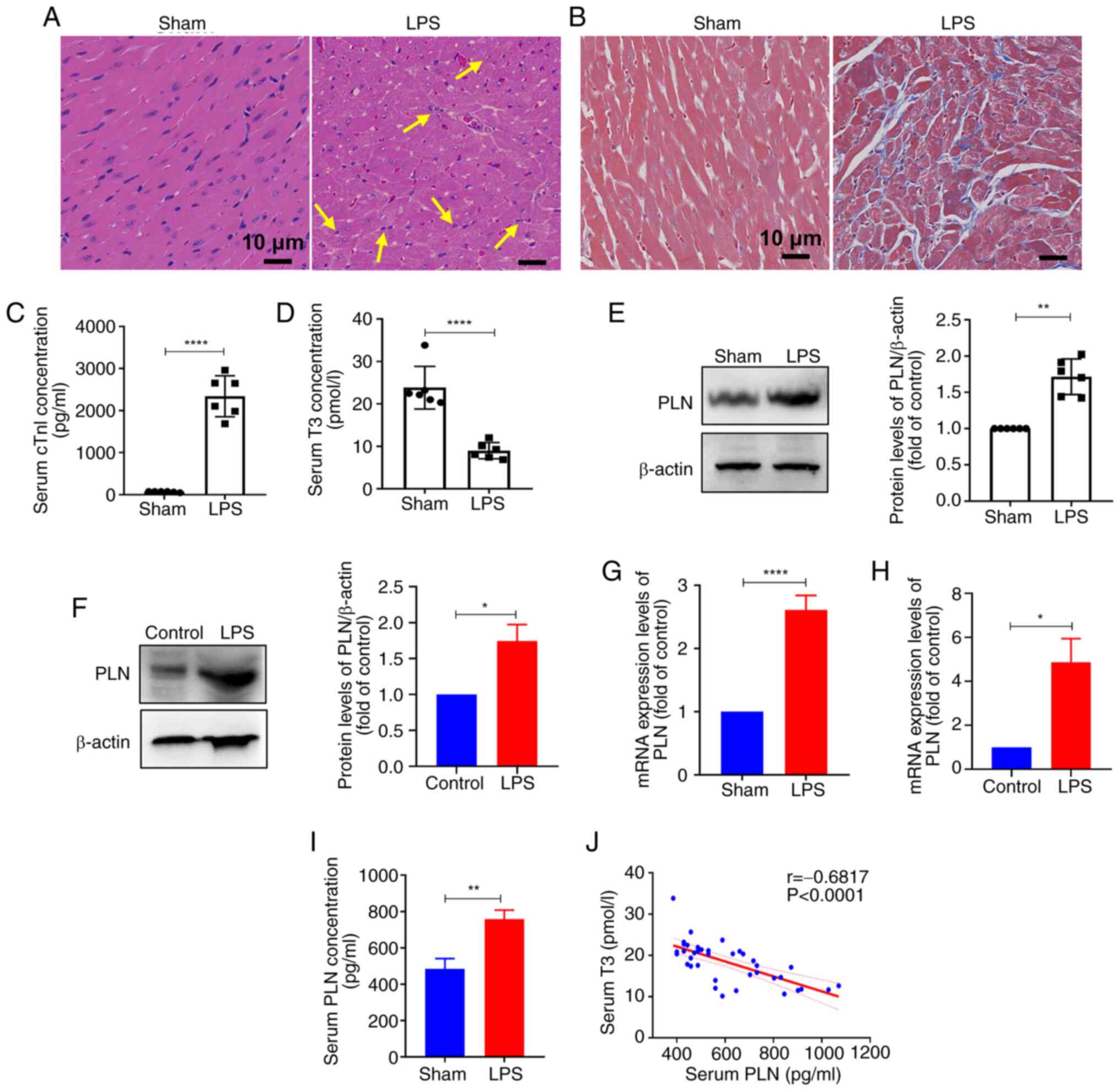

Hematoxylin and eosin and Masson staining of the

cardiac tissue sections revealed inflammatory cell infiltration and

myocardial fibrosis in the LPS group (Fig. 1A and B). The serological levels

of cTnI were significantly greater in the LPS group than those in

the control group (Fig. 1C).

These results indicated that LPS successfully induced SIC in

vivo. Furthermore, serum detection revealed a significant

decrease in the concentration of T3 in response to LPS treatment

(Fig. 1D). Compared with in the

control group cells, the chosen concentration of 80 ng/ml T3 had

the largest effect on cell viability; treatment with this resulted

in a >80% increase in cell viability compared with the control

(Fig. S1). Previous proteomics

analyses of the hearts of normal mice and mice with sepsis (the LPS

group) revealed that the expression of PLN, which is related to T3

regulation of cardiac calcium, was significantly increased in mice

with sepsis (Fig. S2).

Similarly, the results of WB and RT-qPCR further confirmed the

significantly elevated levels of PLN in myocardial tissues and H9C2

cells in the LPS group (Fig.

1E-G). In vitro, the results of proliferation, apoptosis

and inflammation assays revealed that LPS induced inflammatory

damage to cardiomyocytes, as cells treated with LPS exhibited a

decrease in cellular viability, an increased proportion of

apoptotic cells and a reduction in cell growth density compared

with in the control group (Fig.

S3A-D). Moreover, serum PLN concentration was significantly

elevated in the serum of mice with sepsis compared with that in the

control group (Fig. 1I).

Furthermore, analysis of serum T3 and PLN levels revealed a

significant negative correlation between the two parameters in the

mouse model of SIC (Fig. 1J).

PLN is a critical regulator of calcium cycling and contractility in

the heart, and impairs calcium recycling in the endoplasmic

reticulum (30). In the present

study, intracellular calcium overload increased, as indicated by

Fluo-4AM green fluorescence staining, and was accompanied by

abnormally elevated levels of ROS in the LPS group, as indicated by

increased red fluorescence in the nucleus (Fig. S3E-H).

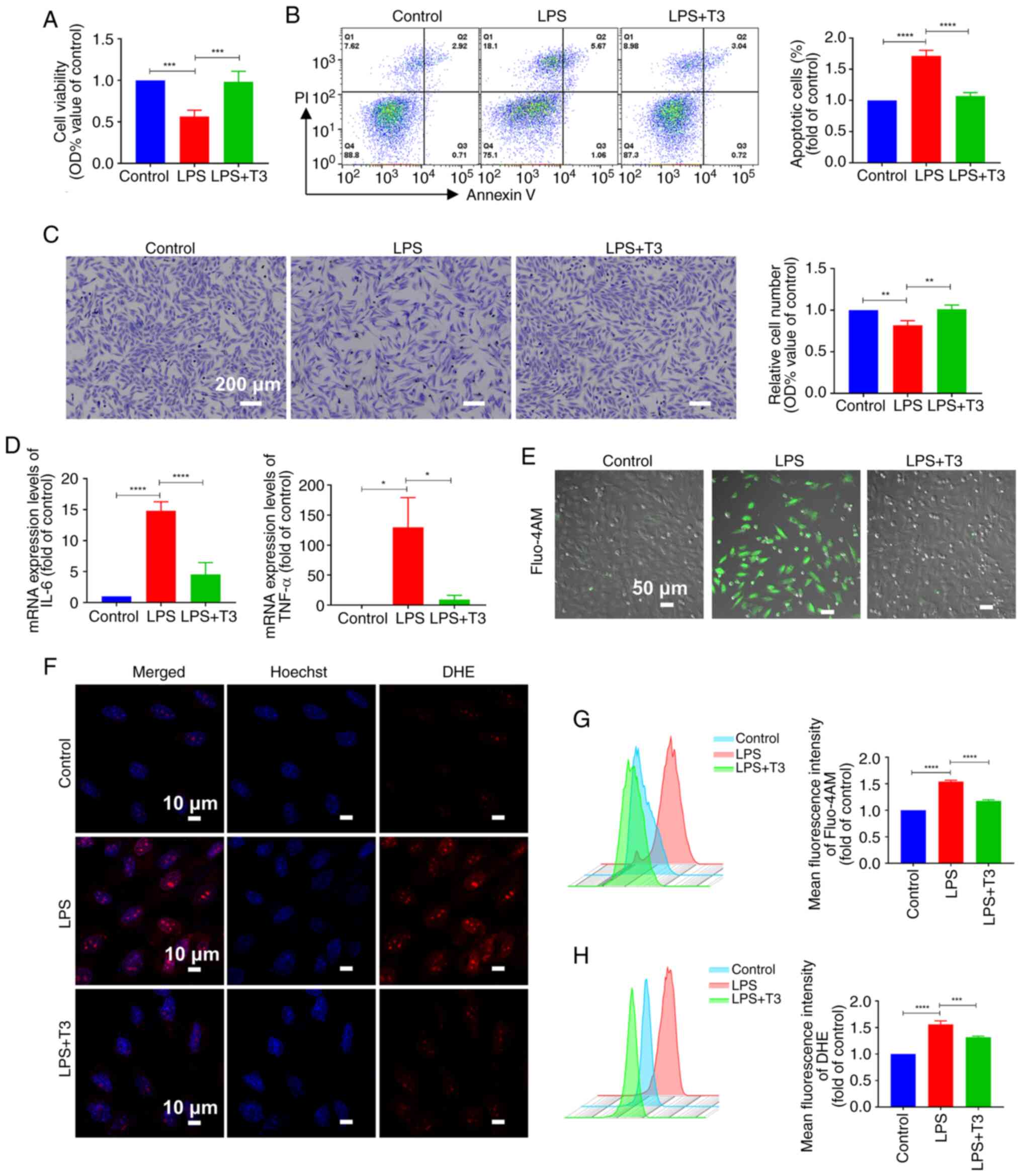

T3 treatment alleviates cardiomyocyte

damage in vitro and in vivo

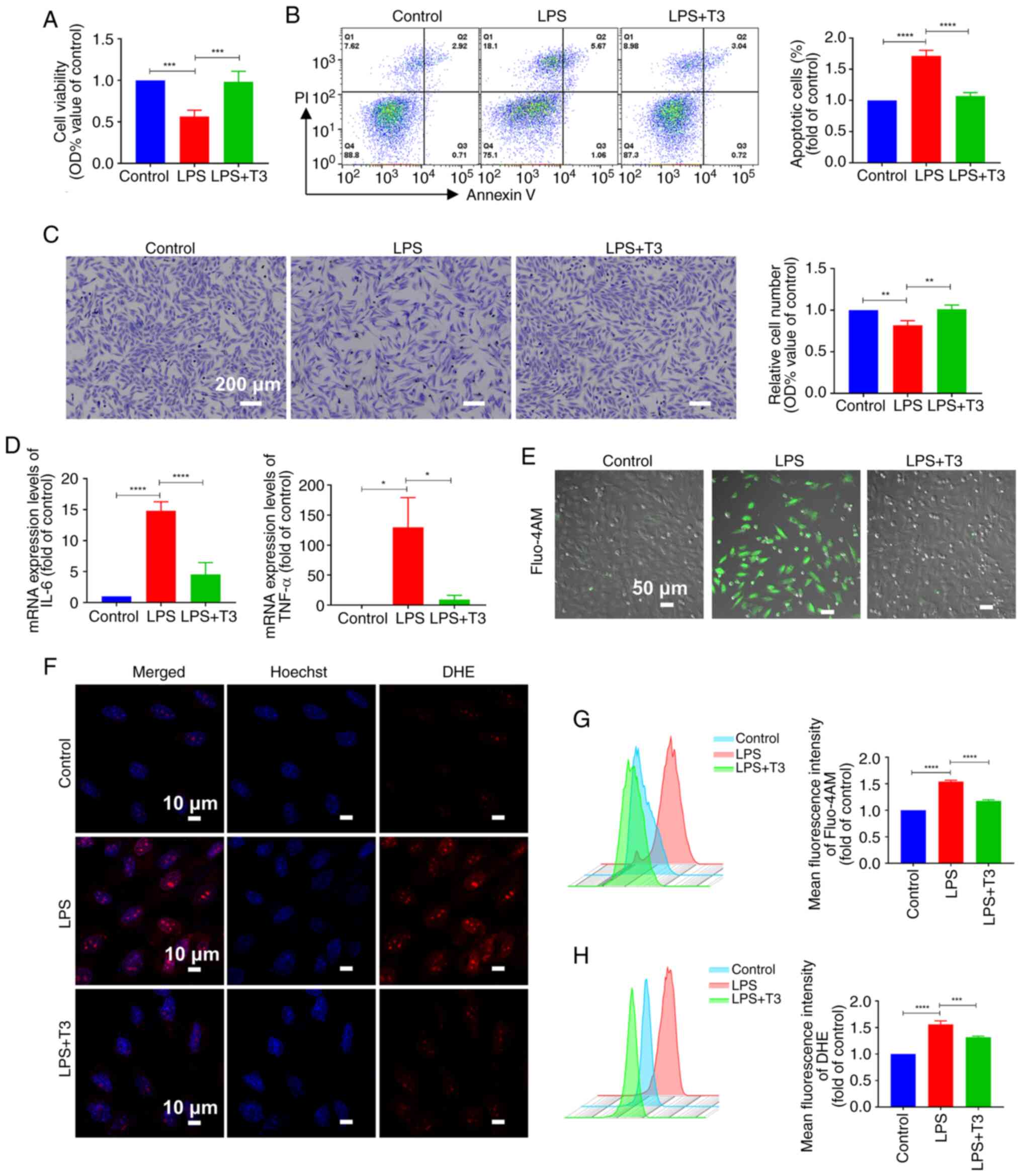

The results revealed that treatment with T3

significantly increased cell viability, reduced the proportion of

apoptotic cells and promoted cell proliferation under LPS challenge

(Fig. 2A-C). Additionally, T3

treatment significantly reduced the expression levels of the

inflammatory factors interleukin 6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor

α compared with in the LPS group (TNF-α) (Fig. 2D). Furthermore, the results of

the present study revealed that, compared with in the LPS group,

intracellular calcium accumulation was reduced and calcium overload

was effectively alleviated after T3 intervention (Fig. 2E and G). In addition, compared

with in the LPS group, T3 treatment reduced the intracellular ROS

content and alleviated intracellular oxidative stress (Fig. 2F and H).

| Figure 2T3 treatment alleviates cardiomyocyte

damage in vitro. (A) Cell Counting Kit-8 assay assessed H9C2

cell viability (n=3). (B) Apoptosis detection and statistical

analysis of H9C2 cells (n=3). (C) Crystal violet staining and

statistical analysis of H9C2 cells (n=3). (D) Quantitative PCR

detected the mRNA expression levels of IL-6 and TNF-α in H9C2 cells

(n=3). (E) Fluo-4AM fluorescence images of H9C2 intracellular

calcium levels. Scale bar, 50 µm; n=3. (F) DHE fluorescence

images of H9C2 intracellular reactive oxygen species levels. Scale

bar, 10 µm; n=3. (G) Flow cytometric detection of (G) Fluo-4

AM and (H) DHE mean fluorescence intensity in H9C2 cells (n=3). All

experiments were repeated three times. Data are presented as the

mean ± standard deviation. *P<0.05,

**P<0.01, ***P<0.001,

****P<0.0001. IL-6, interleukin 6; LPS,

lipopolysaccharide; OD, optical density; PI, propidium iodide; PLN,

phospholamban; T3, triiodothyronine; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor

α. |

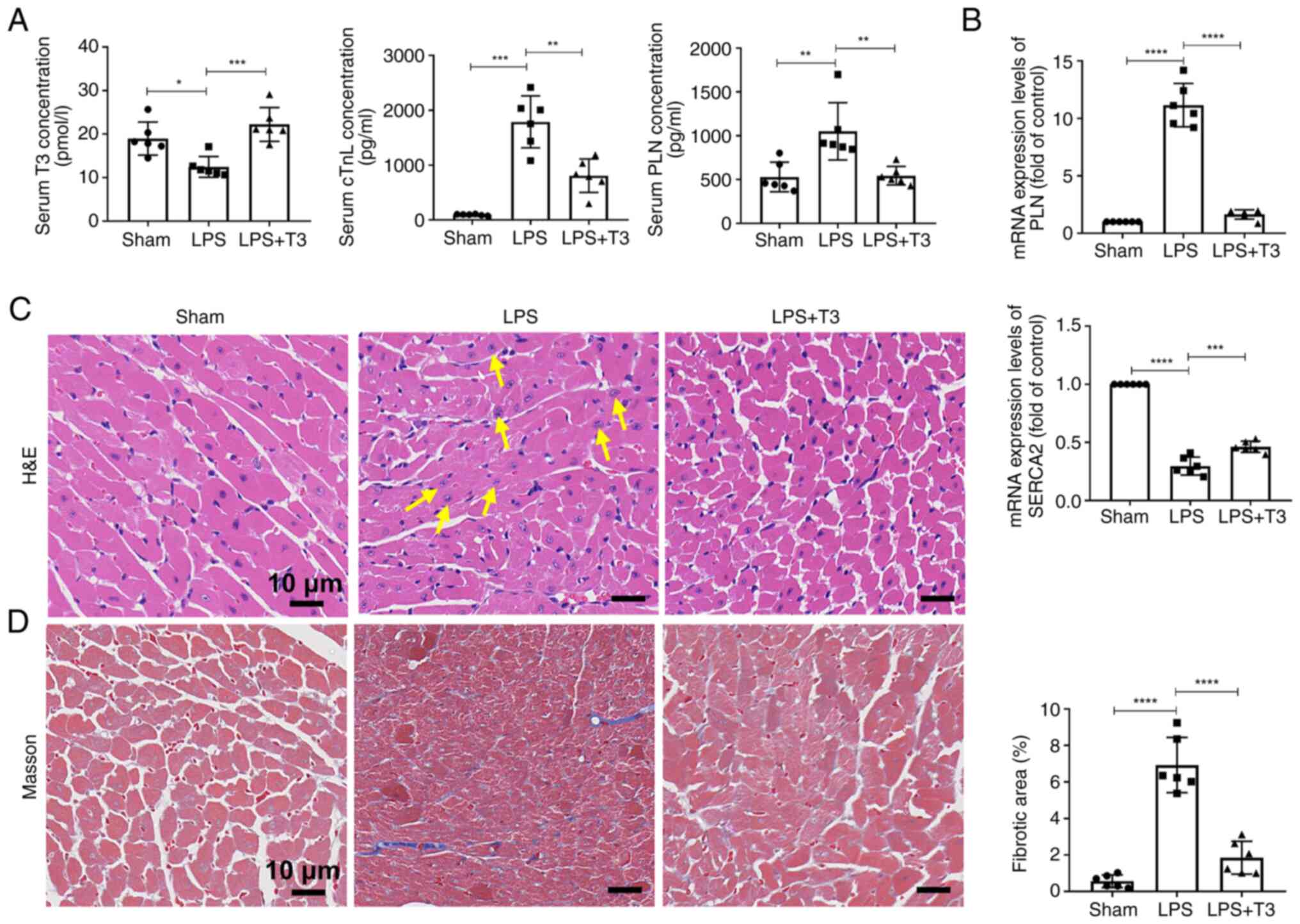

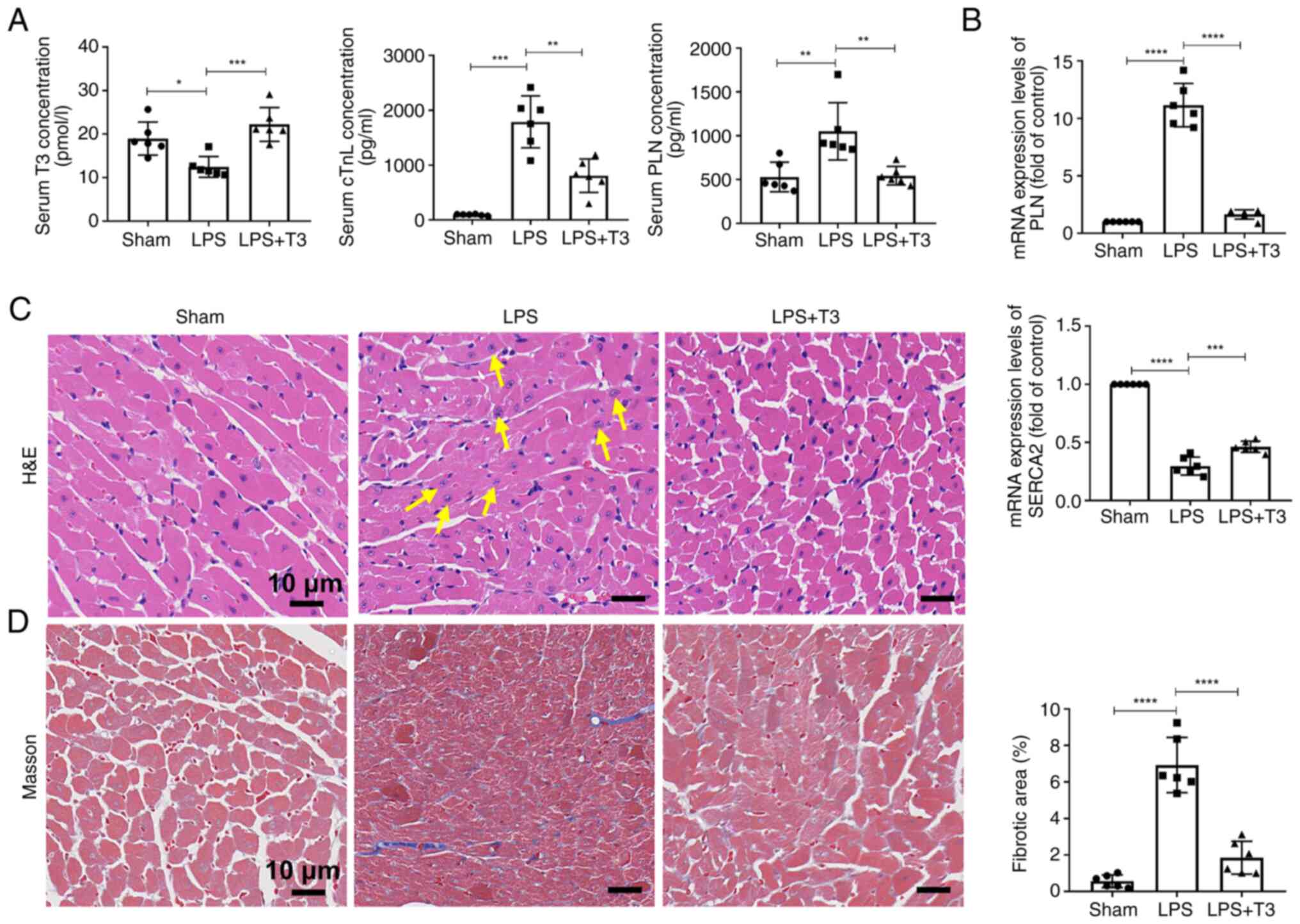

After T3 intervention in the mice, the serum

concentrations of various factors were measured, revealing an

increase in the concentration of T3, and a decrease in cTnI and PLN

concentrations compared with in the LPS group (Fig. 3A). In addition, compared with in

the LPS group, the mRNA expression levels of PLN in myocardial

tissues were reduced, whereas SERCA2 expression was increased after

T3 treatment (Fig. 3B). Tissue

section staining showed that T3 treatment effectively reduced the

infiltration of inflammatory cells in myocardial tissue in the LPS

group (Fig. 3C), decreased the

deposition of collagen fibers and reduced the number of fibroblasts

in myocardial tissue (Fig.

3D).

| Figure 3T3 treatment alleviates cardiomyocyte

damage in vivo. (A) Serum ELISA results for mice (n=6). (B)

Quantitative PCR detection of mRNA expression levels in mice (n=6).

(C) H&E staining was applied to mouse myocardial tissue (n=6).

Yellow arrows indicate inflammatory cells. Scale bar, 10 µm.

(D) Masson staining and quantitative analysis were applied to mouse

myocardial tissue (n=6). Scale bar, 10 µm. All experiments

were conducted in triplicate using independent samples. The data

are presented as the mean ± standard deviation.

*P<0.05, **P<0.01,

***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001. cTnI, cardiac

troponin I; H&E, hematoxylin and eosin; LPS,

lipopolysaccharide; PLN, phospholamban; SERCA2, sarcoplasmic

reticulum calcium ATPase; T3, triiodothyronine. |

T3 reduces PLN expression through

JNK/c-Jun signaling pathway inhibition

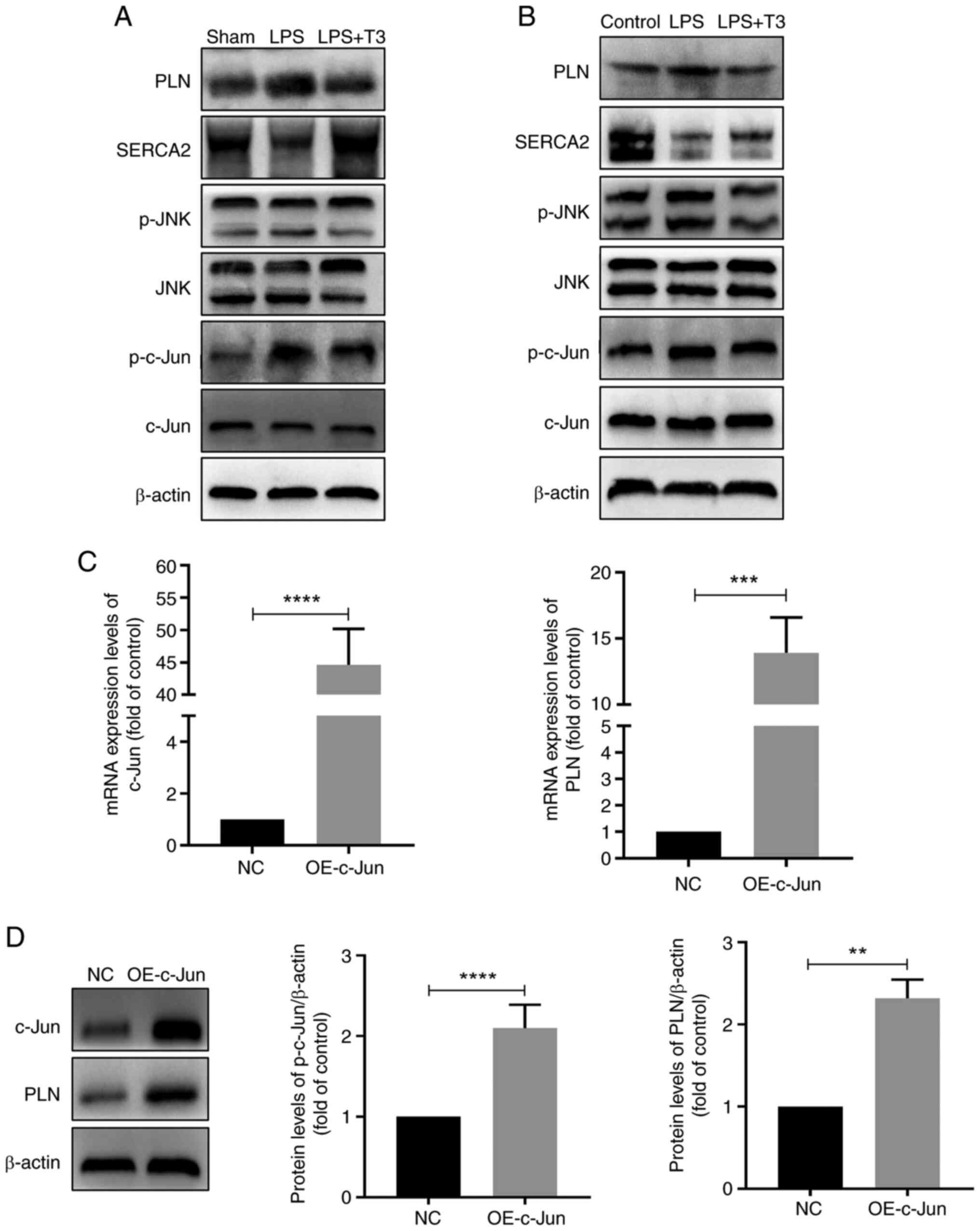

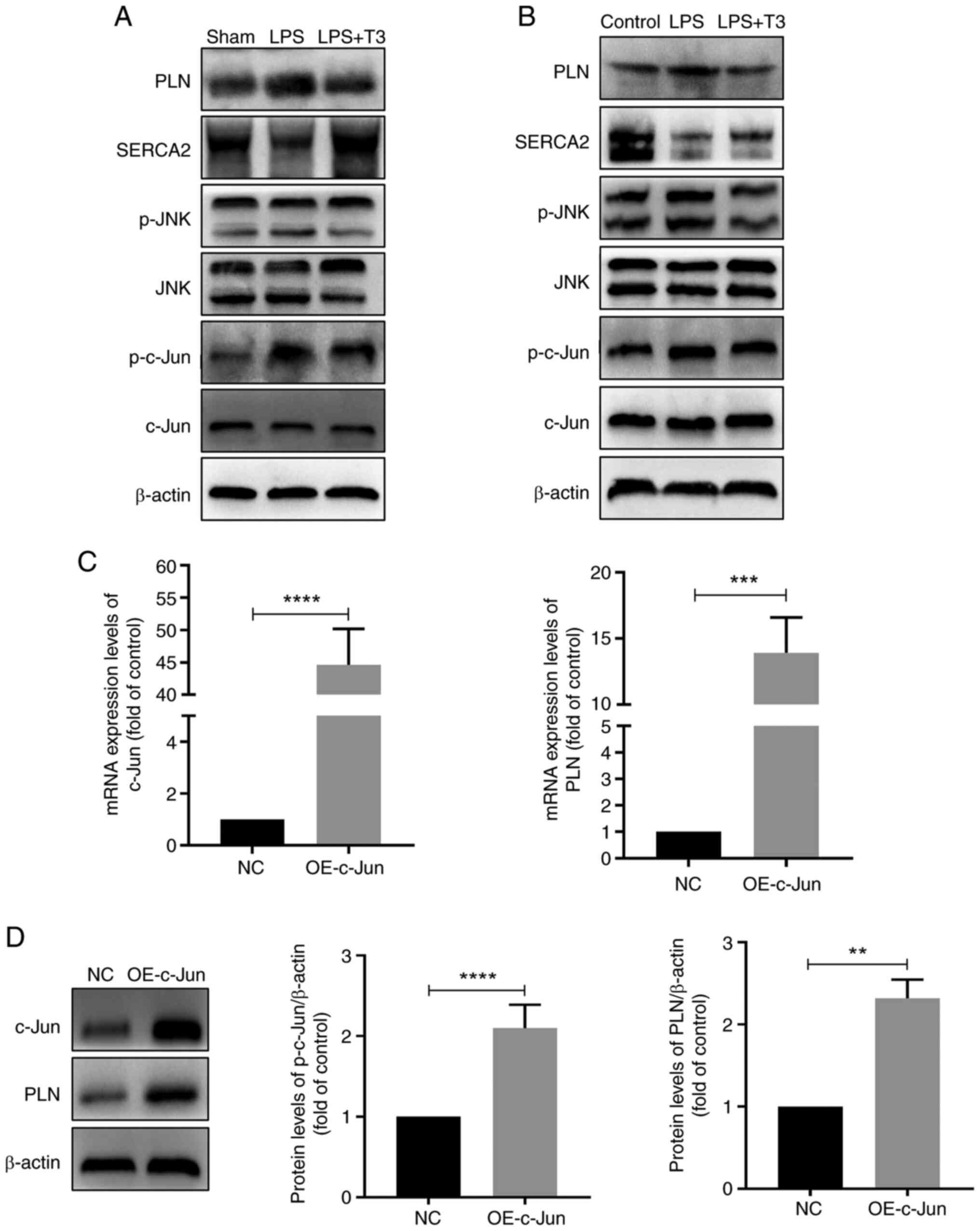

The specific mechanisms by which T3 regulates PLN

were subsequently investigated. According to the results of WB,

treatment with T3 decreased the protein levels of PLN compared with

in the LPS group in vivo and in vitro (Figs. 4A, B, S4A and B). In addition, it was

revealed that since PLN expression decreased, the p-PLN/PLN ratio

increased after T3 treatment (Fig.

S4C and D). It has previously been reported that T3 can

negatively regulate JNK phosphorylation, thereby inhibiting its

proapoptotic effects (27).

Therefore, the present study examined the levels of p-JNK and

phosphorylation of its downstream target protein, c-Jun, following

T3 intervention, and the results revealed that the phosphorylation

of both JNK and c-Jun was decreased compared with in the LPS group

(Figs. 4A, B, S4A and B).

| Figure 4T3 reduces PLN expression through

JNK/c-Jun signaling pathway inhibition. WB detection of protein

levels in the (A) myocardial tissues of mice (n=6) and in (B) H9C2

cells (n=3). (C) Quantitative PCR detection of mRNA expression

levels in H9C2 cells (n=3). (D) WB detection of protein levels in

H9C2 cells (n=3). All in vitro experiments were performed

using triplicate samples and were repeated three times. Data are

presented as the mean ± standard deviation. **P<0.01,

***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001. LPS,

lipopolysaccharide; NC, negative control; OE, overexpression; p-,

phosphorylated; PLN, phospholamban; SERCA2, sarcoplasmic reticulum

calcium ATPase; T3, triiodothyronine; WB, western blotting. |

To further explore the regulatory relationship

between c-Jun and PLN, cells were transfected with a plasmid

overexpressing c-Jun. Overexpression of c-Jun upregulated the mRNA

and protein expression levels of PLN, and decreased the p-PLN/PLN

ratio (Figs. 4C, D, and S4E).

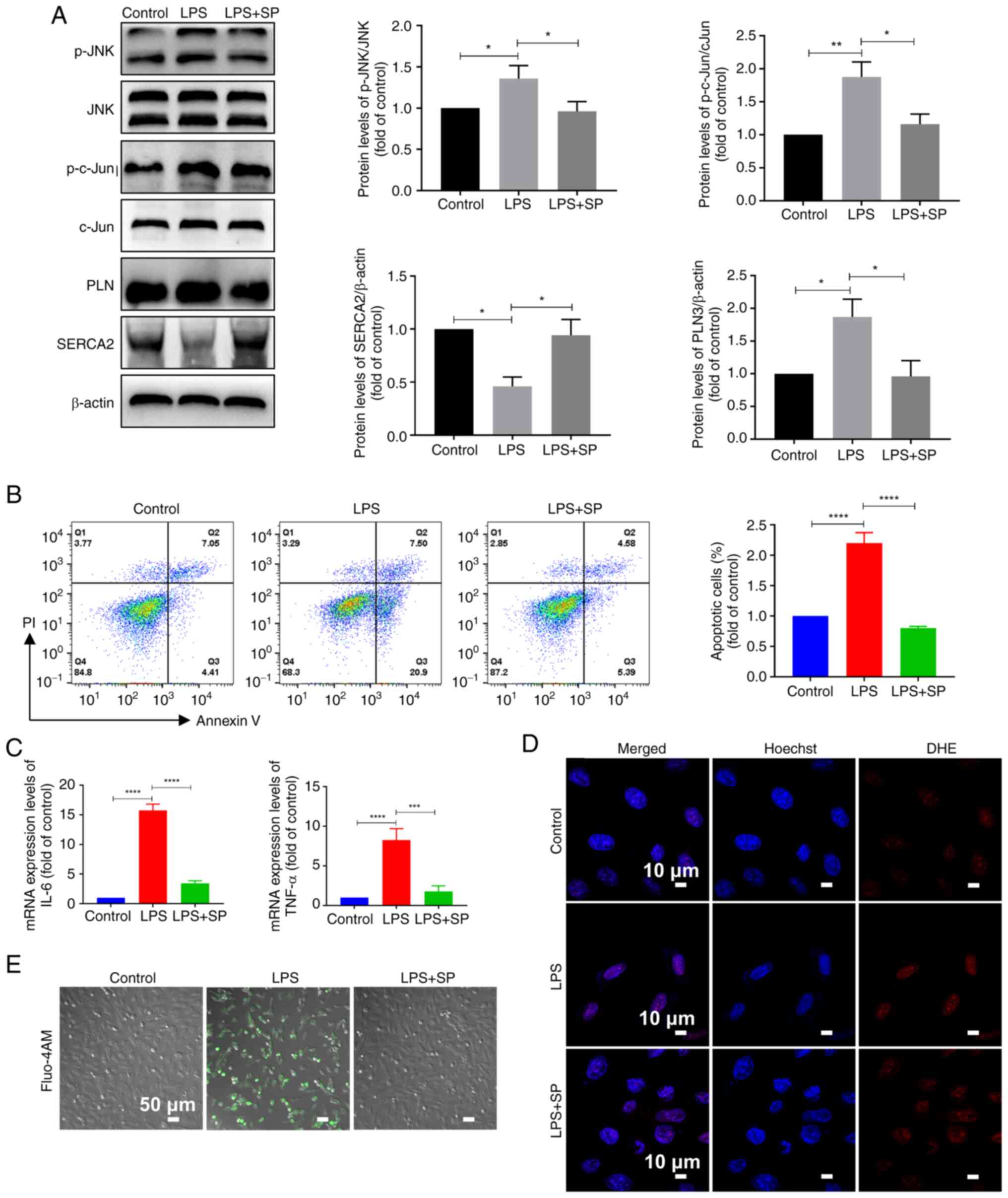

Inhibition of the JNK/c-Jun signaling

pathway reduces cardiomyocyte damage

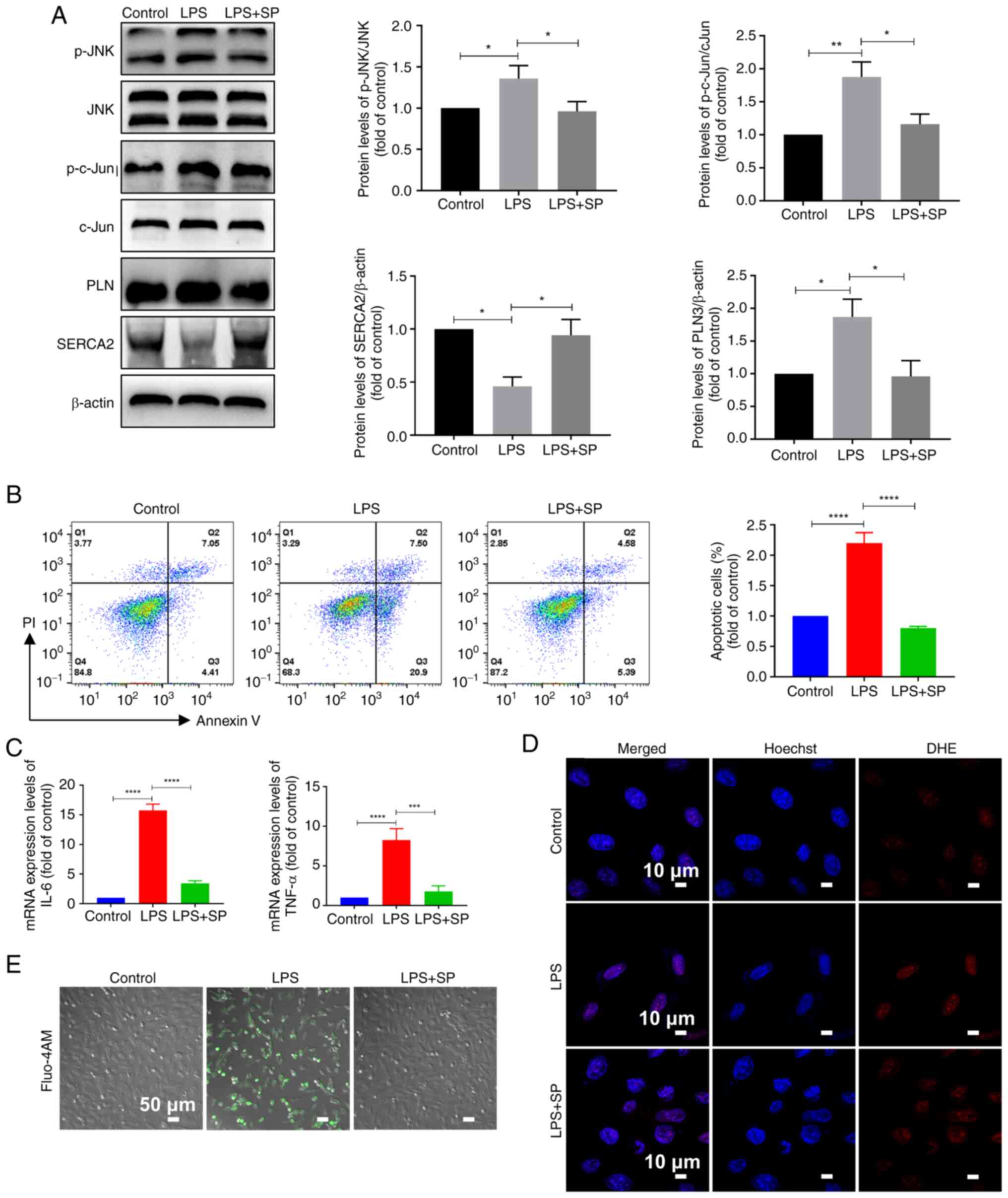

According to the results of the CCK-8 assay, 10

µM was selected as the working concentration of the JNK

inhibitor SP, as 10 µM SP had the least toxic effect on

cells compared with the control (Fig. S1). Subsequently, it was used to

confirm that T3 alleviates cardiomyocyte damage through the

JNK/c-Jun pathway, as T3 and SP similarly reduced the

phosphorylation levels of JNK and c-Jun (Fig. 5A). Further WB revealed that c-Jun

phosphorylation levels were decreased after SP treatment and that

total PLN protein levels were decreased, whereas the p-PLN/PLN

ratio was increased compared with in the LPS group (Figs. 5A and S5). In comparison with the

LPS group, cell apoptosis was decreased, and the intracellular

synthesis of inflammatory factors was reduced following SP

treatment (Fig. 5B and C).

Furthermore, SP intervention decreased intracellular ROS levels and

reduced intracellular calcium ion accumulation compared with in the

LPS group (Fig. 5D and E).

| Figure 5Inhibition of the JNK/c-Jun signaling

pathway improves cardiomyocyte damage. (A) Western blotting

detection of protein levels and semi-quantitative analysis in H9C2

cells (n=3). (B) Apoptosis assay and statistical analysis in H9C2

cells (n=3). (C) Quantitative PCR detection of mRNA expression

levels in H9C2 cells (n=3). (D) Fluorescence images of H9C2

intracellular DHE reactive oxygen species levels. Scale bar, 10

µm; n=3. (E) Fluo-4 AM fluorescence images of H9C2

intracellular calcium levels. Scale bar, 50 µm; n=3. All

experiments were repeated three times. Data are presented as the

mean ± standard deviation. *P<0.05,

**P<0.01, ***P<0.001,

****P<0.0001. IL-6, interleukin 6; LPS,

lipopolysaccharide; p-, phosphorylated; PI, propidium iodide; PLN,

phospholamban; SP, SP600125; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor α. |

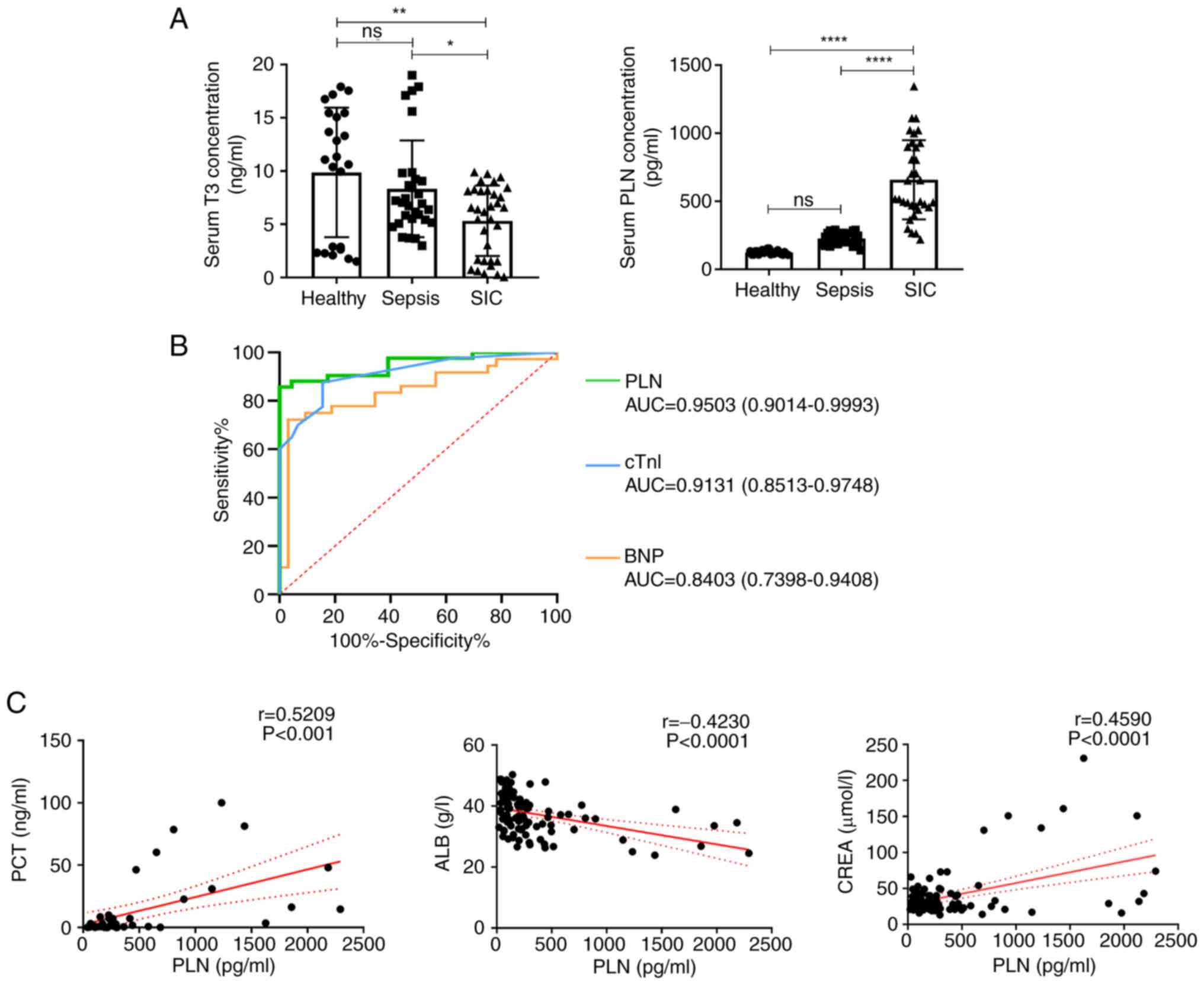

Clinical value of elevated PLN in

patients with SIC

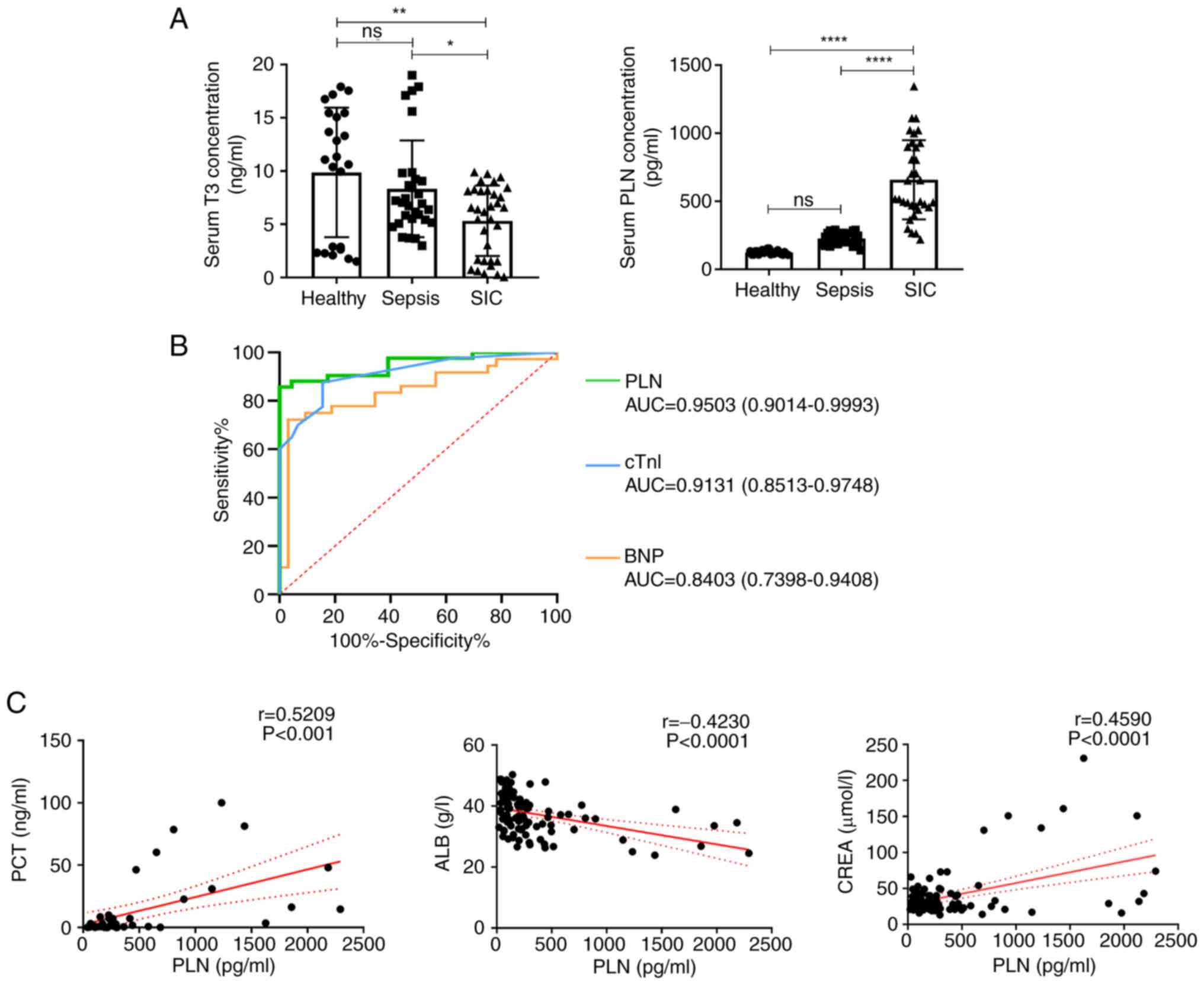

To explore the clinical value of PLN, serum samples

from patients were collected for analysis. The general data of the

patients are listed in Table

SI. The results revealed that in the SIC group, patients had

significantly lower serum T3 levels and significantly higher PLN

levels compared with those in the healthy group (Fig. 6A). ROC curves were constructed on

the basis of the PLN, cTnI and BNP serum contents. PLN had a

greater area under the curve, 0.9503 (95% CI: 0.9014-0.9993),

compared with the other two markers, cTnI [0.9131 (95% CI:

0.8513-0.9748)] and BNP 0.8403 (95% CI: 0.7398-0.9408)], and the

optimal threshold value was determined to be 436.8 pg/ml (Fig. 6B). In addition, PLN was

negatively correlated with serum ALB, whereas it was positively

correlated with serum PCT and serum CREA (Fig. 6C).

| Figure 6Clinical value of elevated PLN in

patients with SIC. (A) Levels of T3 and PLN in each group of

patients were measured by ELISA. (B) Receiver operating

characteristic curves were constructed according to the serum

levels of PLN, cTnI and BNP. (C) Correlation curves of serum PLN

with PCT, ALB and CREA. Data are presented as the mean ± standard

deviation. ns, no significance; *P<0.05,

**P<0.01, ****P<0.0001. ALB, albumin;

AUC, area under the curve; BNP, brain natriuretic peptide; CREA,

creatinine; cTnI, cardiac troponin I; PCT, procalcitonin; PLN,

phospholamban; SIC, sepsis-induced cardiomyopathy; T3,

triiodothyronine |

Discussion

SIC is a critical condition involving the heart, and

is associated with varying degrees of myocardial damage during the

progression of sepsis, often leading to a poor prognosis and high

mortality rate (7). The

pathological mechanisms of SIC are complex and include inflammatory

damage to cardiomyocytes, the release of nitric oxide and ROS,

mitochondrial dysfunction and abnormal calcium regulation (16). Thyroid hormones are important

indicators of disease severity and mortality, and patients with

sepsis often experience thyroid dysfunction (39). In addition to their classical

metabolic regulatory roles, thyroid hormones exert cardioprotective

and reparative effects (40).

Consistent with these findings, significantly low levels of T3 were

observed in patients with SIC, as well as in in vivo and

in vitro models of SIC, in the present study, and

supplementation with T3 mitigated myocardial tissue lesions while

reducing cardiomyocyte calcium overload and ROS levels.

PLN is a small transmembrane protein localized on

the SR of cardiomyocytes that serves a key regulatory role in

inhibiting Ca2+ transport, and thereby crucially

influences cardiac contractile and diastolic functions (41). In cardiomyocytes, PLN reduces the

affinity of SERCA2 for Ca2+, whereas the phosphorylation

of PLN relieves this effect and promotes calcium recycling back

into the SR (36). This process

is vital for regulating myocardial contraction and diastole.

Recently, Stege et al (42) revealed a prominent role for

abnormal PLN protein distribution and SR/endoplasmic reticulum

disorganization in the underlying mechanism of cardiomyopathy.

In the present study, abnormally elevated levels of

PLN were observed in SIC. This elevation may have hindered the

effective recycling of extracellular calcium into the SR, leading

to calcium overload in cardiomyocytes and impairing cardiomyocyte

diastolic function. This effect may be attributed to alterations in

the phosphorylation levels of the Ser16 and Thr17 sites of PLN.

Furthermore, the experimental results indicated that T3 decreased

PLN expression and altered the phosphorylation ratio of PLN in

cardiomyocytes in vivo and in vitro, which is

consistent with the findings of previous studies (43,44); however, the specific mechanism is

unknown.

It has previously been reported that T3 can protect

against heart ischemia/reperfusion injury by modulating various

intracellular kinase signaling pathways (45). The balance between the

proapoptotic and prosurvival kinase signaling pathways is critical

in myocardial injury and remodeling. It has previously been shown

that T3 can significantly reduce the phosphorylation of the

proapoptotic protein kinase JNK (46). Consistent with these findings,

the current study revealed that activated JNK phosphorylation in

SIC was significantly reduced by T3 treatment, indicating that T3

may inhibit the JNK pathway. JNK is a branch of the MAPK pathway

that serves crucial roles in cell proliferation, migration,

survival, senescence and stress responses. Despite its dual roles

in apoptosis and survival regulation (47), the findings of the present study

suggested that JNK inhibition may effectively prevent apoptosis and

promote cell survival. c-Jun is the primary downstream target

molecule of JNK and is a component of the activator protein-1

transcriptional complex, which is modulated by various protein

kinases and has a regulatory role in apoptosis and stress responses

(48). The JNK/c-Jun signaling

pathway is directly associated with the development of various

diseases, and its activation has been shown to have protective

effects on ischemia/reperfusion injury in the liver, lung, brain

and heart (49-51). The phosphorylation of c-Jun is a

critical indicator of its activation (52). Only a few studies, such as Chin

et al (53) and Song

et al (54), have

suggested a relationship between JNK/c-Jun and PLN in the context

of myocardial ischemia/reperfusion or myocardial hypertrophy. In

the present study, the results revealed increased c-Jun

phosphorylation following JNK activation, indicating the activation

of the JNK/c-Jun signaling pathway in SIC. Notably, concurrent

changes in PLN activity were also observed upon inhibition of the

JNK/c-Jun signaling pathway. Specifically, inhibition of this

pathway led to decreased PLN expression and altered phosphorylation

at its regulatory sites. To further investigate the relationship

between the JNK/c-Jun pathway and PLN, plasmid transfection

experiments were conducted to clarify whether c-Jun may act as an

upstream transcription factor regulating PLN synthesis. The results

showed that the mRNA and protein levels of PLN were found to be

consistent with the expression changes of c-Jun.

The unknown cardiac dysfunction underlying SIC,

combined with the complexities of the cardiovascular system, has

resulted in the absence of standardized diagnostic criteria in

clinical practice (55,56). PLN is specifically expressed in

myocardial tissues and has a small molecular weight of 6 kDa in its

monomeric form and 25 kDa in its pentameric form (57). This molecular weight is much

lower than that of CK at 86 kDa or cTnI at 37 kDa, making PLN more

readily released into the bloodstream during myocardial injury and

demonstrating superior sensitivity as a biomarker in serum. The

area under the ROC curve was 0.9503 for PLN, with a 95% confidence

interval of 0.9014-0.9993, indicating that PLN has excellent

diagnostic performance for SIC. Furthermore, serum PLN levels were

revealed to be correlated with markers of liver and kidney injury,

as well as inflammatory indicators. Therefore, it may be concluded

that PLN holds clinical value in pediatric patients to a certain

extent.

In summary, the present study identified abnormally

decreased T3 and elevated PLN concentrations, with these

concentrations showing a negative correlation in a mouse disease

model. Moreover, elevated PLN levels were associated with impaired

intracellular calcium recycling, leading to increased intracellular

oxidative stress levels and subsequent cardiomyocyte injury.

Exogenous supplementation with T3 reversed calcium overload and

oxidative stress by inhibiting PLN and its downstream calcium

regulatory factors, thereby reducing myocardial injury. The present

study also revealed that T3 treatment suppressed the expression and

activity of JNK and c-Jun, indicating that T3 may regulate PLN to

mitigate myocardial injury through the JNK/c-Jun signaling

pathway.

Notably, the current study has several limitations.

First, the clinical sample size was small. Although the findings

revealed increased PLN levels and decreased T3 levels across the

three experimental groups, there was no negative correlation

between PLN and T3 levels in clinical pediatric patients (data not

shown). This discrepancy may be attributed to the incomplete

development of the thyroid gland in children. There are significant

differences in thyroid hormone levels between children and adults,

while these variations tend to approach the adult reference ranges

as age increases (58). Children

have a significantly higher demand for thyroid hormones due to

their growth requirements, which far exceeds that of adults.

Additionally, because their thyroid glands are not yet fully

mature, their hormonal regulatory capabilities are weaker.

Consequently, the fluctuations in hormone levels under stress

conditions are more pronounced in children compared with in adults.

Furthermore, several factors such as obesity, smoking and lifestyle

can influence thyroid hormone levels as age increases (59). To address this limitation, a

larger sample size and a multicenter clinical trial are required to

further validate the scientific hypothesis. Second, additional

robust evidence, such as c-Jun knockdown, is needed to strengthen

the credibility of this mechanism which involves the JNK/c-Jun

signaling pathway in the regulatory mechanisms of T3. Thus, more

direct experimental results including dual-luciferase reporter

assays and other methodologies are needed to substantiate the

interaction between c-Jun and PLN. Addressing these limitations

will contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of the

mechanisms underlying the observed effects of T3 and PLN on SIC.

Finally, Figs. 2, 5 and S3 were derived from several

distinct experiments, where experimental conditions and procedures

may introduce a certain degree of error, hence the rate of

apoptosis between H9C2 cells treated with LPS were not completely

the same among these figures. Thus, in the analysis of each

dataset, the data were normalized to the control group to minimize

the impact of the difference to the greatest extent possible.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated a

negative correlation between low T3 levels and elevated PLN levels

in a mouse model of SIC. The correlation may stem from the

influence of PLN on intracellular calcium cycling and oxidative

stress levels in cardiomyocytes, which are countered by T3 to

improve cardiomyocyte function through the inhibition of PLN

phosphorylation. Moreover, the findings of the current study

suggested that the JNK/c-Jun signaling pathway may serve a crucial

role in mediating the negative regulatory effects of T3 on PLN.

Additionally, PLN was identified as a novel biomarker for SIC,

which has significant potential for early diagnosis of SIC in

pediatric patients.

Supplementary Data

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author. The data generated in the

present study may be found in the iProX database under accession

number PXD059227 or at the following URL: https://www.iprox.cn/page/project.html?id=IPX0010782000.

Authors' contributions

QX and QY analyzed the patient data regarding SIC

and performed experiments on cell models. JZ contributed to study

conception and design, BT analyzed and interpretated the data, and

both were involved in drafting the manuscript or revising it. HXi,

RW and HL performed the histological examination of the heart, and

were major contributors in writing the manuscript. TC and HXu made

substantial contributions to the conception and design of the

research, analysis and interpretation of data, and the acquisition

of funding. TC and HXu confirm the authenticity of all the raw

data. All authors read and approved the final version of the

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The clinical study protocol was approved by the

Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Children's Hospital of

Chongqing Medical University (approval no. 2021-353). Written

informed consent was obtained from the parents of all patients. The

animal experiments were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of

Children's Hospital of Chongqing Medical University (approval no.

CHCMU-IACUC20210114036).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr Qin Zhou and Mrs.

Li Zhao (Department of Pediatric Research Institute, Children's

Hospital of Chongqing Medical University) for their pathology help

and assistance.

Funding

This work was supported by the China Postdoctoral Science

Foundation (grant no. 2023M730447), the Chongqing Science &

Technology Commission (grant no. CSTB2023NSCQ-MSX0603), the

Chongqing Postdoctoral Research Program Special Grant (grant no.

2023CQBSHTB3048), the Chongqing Municipal Talent Program (grant no.

cstc2024ycjh-bgzxm0024) and the Chongqing Medical Scientific

Research Project (Joint project of Chongqing Health Commission and

Science and Technology Bureau; grant no. 2025GDRC008).

References

|

1

|

Singh S, Mohan S and Singhal R:

Definitions for sepsis and septic shock. JAMA. 316:4582016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Gohil SK, Cao C, Phelan M, Tjoa T, Rhee C,

Platt R and Huang SS: Impact of policies on the rise in sepsis

incidence, 2000-2010. Clin Infect Dis. 62:695–703. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Mahla RS, Vincent JL and Sakr Y; ICON and

SOAP Investigators: Sepsis is a global burden to human health:

Incidences are underrepresented: Discussion on 'comparison of

European ICU patients in 2012 (ICON) versus 2002 (SOAP)'. Intensive

Care Med. 44:1197–1198. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Suzuki T, Suzuki Y, Okuda J, Kurazumi T,

Suhara T, Ueda T, Nagata H and Morisaki H: Sepsis-induced cardiac

dysfunction and β-adrenergic blockade therapy for sepsis. J

Intensive Care. 5:222017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Allison SJ: Sepsis: NET-induced

coagulation induces organ damage in sepsis. Nat Rev Nephrol.

13:1332017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Weiss SL, Peters MJ, Alhazzani W, Agus

MSD, Flori HR, Inwald DP, Nadel S, Schlapbach LJ, Tasker RC, Argent

AC, et al: Surviving sepsis campaign international guidelines for

the management of septic shock and sepsis-associated organ

dysfunction in children. Intensive Care Med. 46(Suppl 1): S10–S67.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Hollenberg SM and Singer M:

Pathophysiology of sepsis-induced cardiomyopathy. Nat Rev Cardiol.

18:424–434. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Ehrman RR, Sullivan AN, Favot MJ, Sherwin

RL, Reynolds CA, Abidov A and Levy PD: Pathophysiology,

echocardiographic evaluation, biomarker findings, and prognostic

implications of septic cardiomyopathy: A review of the literature.

Crit Care. 22:1122018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Melis MJ, Miller M, Peters VBM and Singer

M: The role of hormones in sepsis: An integrated overview with a

focus on mitochondrial and immune cell dysfunction. Clin Sci

(Lond). 137:707–725. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Das BK, Agarwal P, Agarwal JK and Mishra

OP: Serum cortisol and thyroid hormone levels in neonates with

sepsis. Indian J Pediatr. 69:663–665. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Vidart J, Axelrud L, Braun AC, Marschner

RA and Wajner SM: Relationship among low T3 levels, type 3

deiodinase, oxidative stress, and mortality in sepsis and septic

shock: Defining patient outcomes. Int J Mol Sci. 24:39352023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Jongejan RMS, Meima ME, Visser WE,

Korevaar TIM, Van Den Berg SAA, Peeters RP and de Rijke YB: Binding

characteristics of thyroid hormone distributor proteins to thyroid

hormone metabolites. Thyroid. 32:990–999. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Salas-Lucia F and Bianco AC: T3 levels and

thyroid hormone signaling. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne).

13:10446912022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Cokkinos DV and Chryssanthopoulos S:

Thyroid hormones and cardiac remodeling. Heart Fail Rev.

21:365–372. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Mastorci F, Sabatino L, Vassalle C and

Pingitore A: Cardioprotection and thyroid hormones in the clinical

setting of heart failure. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 10:9272020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Wang R, Xu Y, Fang Y, Wang C, Xue Y, Wang

F, Cheng J, Ren H, Wang J, Guo W, et al: Pathogenetic mechanisms of

septic cardiomyopathy. J Cell Physiol. 237:49–58. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Shankar TS, Ramadurai DKA, Steinhorst K,

Sommakia S, Badolia R, Thodou Krokidi A, Calder D, Navankasattusas

S, Sander P, Kwon OS, et al: Cardiac-specific deletion of voltage

dependent anion channel 2 leads to dilated cardiomyopathy by

altering calcium homeostasis. Nat Commun. 12:45832021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Capasso JM, Sonnenblick EH and Anversa P:

Chronic calcium channel blockade prevents the progression of

myocardial contractile and electrical dysfunction in the

cardiomyopathic Syrian hamster. Circ Res. 67:1381–1393. 1990.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Selnø ATH, Sumbayev VV and Gibbs BF:

IgE-dependent human basophil responses are inversely associated

with the sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA).

Front Immunol. 13:10522902023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Wang L, Myles RC, Lee IJ, Bers DM and

Ripplinger CM: Role of reduced sarco-endoplasmic reticulum

Ca2+-ATPase function on sarcoplasmic reticulum

Ca2+ alternans in the intact rabbit heart. Front

Physiol. 12:6565162021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Carlson CR, Aronsen JM, Bergan-Dahl A,

Moutty MC, Lunde M, Lunde PK, Jarstadmarken H, Wanichawan P,

Pereira L, Kolstad TRS, et al: AKAP18δ anchors and regulates CaMKII

activity at phospholamban-SERCA2 and RYR. Circ Res. 130:27–44.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Hamstra SI, Whitley KC, Baranowski RW,

Kurgan N, Braun JL, Messner HN and Fajardo VA: The role of

phospholamban and GSK3 in regulating rodent cardiac SERCA function.

Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 319:C694–C699. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Kranias EG and Hajjar RJ: Modulation of

cardiac contractility by the phospholamban/SERCA2a regulatome. Circ

Res. 110:1646–1660. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Sivakumaran V, Stanley BA, Tocchetti CG,

Ballin JD, Caceres V, Zhou L, Keceli G, Rainer PP, Lee DI, Huke S,

et al: HNO enhances SERCA2a activity and cardiomyocyte function by

promoting redox-dependent phospholamban oligomerization. Antioxid

Redox Signal. 19:1185–1197. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Lygren B, Carlson CR, Santamaria K,

Lissandron V, McSorley T, Litzenberg J, Lorenz D, Wiesner B,

Rosenthal W, Zaccolo M, et al: AKAP complex regulates Ca2+

re-uptake into heart sarcoplasmic reticulum. EMBO Rep. 8:1061–1067.

2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Steinberg C, Roston TM, Van der Werf C,

Sanatani S, Chen SRW, Wilde AAM and Krahn AD:

RYR2-ryanodinopathies: From calcium overload to calcium deficiency.

Europace. 25:euad1562023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Strubbe-Rivera JO, Schrad JR, Pavlov EV,

Conway JF, Parent KN and Bazil JN: The mitochondrial permeability

transition phenomenon elucidated by cryo-EM reveals the genuine

impact of calcium overload on mitochondrial structure and function.

Sci Rep. 11:10372021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Reddy LG, Autry JM, Jones LR and Thomas

DD: Co-reconstitution of phospholamban mutants with the Ca-ATPase

reveals dependence of inhibitory function on phospholamban

structure. J Biol Chem. 274:7649–7655. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Qin J, Zhang J, Lin L, Haji-Ghassemi O,

Lin Z, Woycechowsky KJ, Van Petegem F, Zhang Y and Yuchi Z:

Structures of PKA-phospholamban complexes reveal a mechanism of

familial dilated cardiomyopathy. Elife. 11:e753462022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Feyen DAM, Perea-Gil I, Maas RGC,

Harakalova M, Gavidia AA, Arthur Ataam J, Wu TH, Vink A, Pei J,

Vadgama N, et al: Unfolded protein response as a compensatory

mechanism and potential therapeutic target in PLN R14del

cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 144:382–392. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Sinha RA and Yen PM: Metabolic messengers:

Thyroid hormones. Nat Metab. 6:639–650. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Percie du Sert N, Hurst V, Ahluwalia A,

Alam S, Avey MT, Baker M, Browne WJ, Clark A, Cuthill IC, Dirnagl

U, et al: The ARRIVE guidelines 2.0: Updated guidelines for

reporting animal research. PLoS Boil. 18:e30004102020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Feng X, Wang L, Zhou R, Zhou R, Chen L,

Peng H, Huang Y, Guo Q, Luo X and Zhou H: Senescent immune cells

accumulation promotes brown adipose tissue dysfunction during

aging. Nat Commun. 14:32082023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Jiang J, Zhou D, Zhang A, Yu W, Du L, Yuan

H, Zhang C, Wang Z, Jia X, Zhang ZN and Luan B: Thermogenic

adipocyte-derived zinc promotes sympathetic innervation in male

mice. Nat Metab. 5:481–494. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Mahmood SR, Xie X, Hosny El Said N, Venit

T, Gunsalus KC and Percipalle P: β-actin dependent chromatin

remodeling mediates compartment level changes in 3D genome

architecture. Nat Commun. 12:52402021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Hunter T and Garrels JI: Characterization

of the mRNAs for alpha-, beta- and gamma-actin. Cell. 12:767–781.

1977. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Zhang L and Elias JE: Relative protein

quantification using tandem mass tag mass spectrometry. Methods Mol

Biol. 1550:185–198. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Pantos C, Malliopoulou V, Paizis I,

Moraitis P, Mourouzis I, Tzeis S, Karamanoli E, Cokkinos DD,

Carageorgiou H, Varonos D and Cokkinos DV: Thyroid hormone and

cardioprotection: study of p38 MAPK and JNKs during ischaemia and

at reperfusion in isolated rat heart. Mol Cell Biochem.

242:173–180. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Lieder HR, Braczko F, Gedik N, Stroetges

M, Heusch G and Kleinbongard P: Cardioprotection by

post-conditioning with exogenous triiodothyronine in isolated

perfused rat hearts and isolated adult rat cardiomyocytes. Basic

Res Cardiol. 116:272021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Vafiadaki E, Haghighi K, Arvanitis DA,

Kranias EG and Sanoudou D: Aberrant PLN-R14del protein interactions

intensify SERCA2a inhibition, driving impaired Ca2+

handling and arrhythmogenesis. Int J Mol Sci. 23:69472022.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Stege NM, de Boer RA, Makarewich CA, van

der Meer P and Silljé HHW: Reassessing the mechanisms of PLN-R14del

cardiomyopathy: From calcium dysregulation to S/ER malformation.

JACC Basic Transl Sci. 9:1041–1052. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Dong J, Gao C, Liu J, Cao Y and Tian L:

TSH inhibits SERCA2a and the PKA/PLN pathway in rat cardiomyocytes.

Oncotarget. 7:39207–39215. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Gaique TG, Lopes BP, Souza LL, Paula GSM,

Pazos-Moura CC and Oliveira KJ: Cinnamon intake reduces serum T3

level and modulates tissue-specific expression of thyroid hormone

receptor and target genes in rats. J Sci Food Agric. 96:2889–2895.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Mattiazzi A, Tardiff JC and Kranias EG:

Stress seats a new guest at the table of PLN/SERCA and their

partners. Circ Res. 128:471–473. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Zeng B, Liao X, Liu L, Zhang C, Ruan H and

Yang B: Thyroid hormone mediates cardioprotection against

postinfarction remodeling and dysfunction through the

IGF-1/PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. Life Sci. 267:1189772021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

de Castro AL, Fernandes RO, Ortiz VD,

Campos C, Bonetto JH, Fernandes TR, Conzatti A, Siqueira R, Tavares

AV, Schenkel PC, et al: Thyroid hormones improve cardiac function

and decrease expression of pro-apoptotic proteins in the heart of

rats 14 days after infarction. Apoptosis. 21:184–194. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Brennan A, Leech JT, Kad NM and Mason JM:

Selective antagonism of cJun for cancer therapy. J Exp Clin Cancer

Res. 39:1842020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Vernia S, Morel C, Madara JC,

Cavanagh-Kyros J, Barrett T, Chase K, Kennedy NJ, Jung DY, Kim JK,

Aronin N, et al: Excitatory transmission onto AgRP neurons is

regulated by cJun NH2-terminal kinase 3 in response to metabolic

stress. Elife. 5:e100312016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Manieri E, Folgueira C, Rodríguez ME,

Leiva-Vega L, Esteban-Lafuente L, Chen C, Cubero FJ, Barrett T,

Cavanagh-Kyros J, Seruggia D, et al: JNK-mediated disruption of

bile acid homeostasis promotes intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma.

Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 117:16492–16499. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Yang J, Do-Umehara HC, Zhang Q, Wang H,

Hou C, Dong H, Perez EA, Sala MA, Anekalla KR, Walter JM, et al:

miR-221-5p-mediated downregulation of JNK2 aggravates acute lung

injury. Front Immunol. 12:7009332021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Jaeschke A, Karasarides M, Ventura JJ,

Ehrhardt A, Zhang C, Flavell RA, Shokat KM and Davis RJ: JNK2 is a

positive regulator of the cJun transcription factor. Mol Cell.

23:899–911. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Chin KY, Silva LS, Darby IA, Ng DCH and

Woodman OL: Protection against reperfusion injury by

3′,4′-dihydroxyflavonol in rat isolated hearts involves inhibition

of phospholamban and JNK2. Int J Cardiol. 254:265–271. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Song Q, Schmidt AG, Hahn HS, Carr AN,

Frank B, Pater L, Gerst M, Young K, Hoit BD, McConnell BK, et al:

Rescue of cardiomyocyte dysfunction by phospholamban ablation does

not prevent ventricular failure in genetic hypertrophy. J Clin

Invest. 111:859–867. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Sundqvist A, Voytyuk O, Hamdi M, Popeijus

HE, van der Burgt CB, Janssen J, Martens JWM, Moustakas A, Heldin

CH, Ten Dijke P and van Dam H: JNK-dependent cJun phosphorylation

mitigates TGFβ- and EGF-induced pre-malignant breast cancer cell

invasion by suppressing AP-1-mediated transcriptional responses.

Cells. 8:14812019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Martin L, Derwall M, Al Zoubi S,

Zechendorf E, Reuter DA, Thiemermann C and Schuerholz T: The septic

heart: Current understanding of molecular mechanisms and clinical

implications. Chest. 155:427–437. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Funk F, Kronenbitter A, Hackert K, Oebbeke

M, Klebe G, Barth M, Koch D and Schmitt JP: Phospholamban

pentamerization increases sensitivity and dynamic range of cardiac

relaxation. Cardiovasc Res. 119:1568–1582. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Babić Leko M, Gunjača I, Pleić N and

Zemunik T: Environmental factors affecting thyroid-stimulating

hormone and thyroid hormone levels. Int J Mol Sci. 22:65212021.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

59

|

Silvestri E, Lombardi A, de Lange P,

Schiavo L, Lanni A, Goglia F, Visser TJ and Moreno M: Age-related

changes in renal and hepatic cellular mechanisms associated with

variations in rat serum thyroid hormone levels. Am J Physiol

Endocrinol Metab. 294:E1160–E1168. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|