Gastrointestinal cancers (GICs) account for >25%

of all new cancer cases worldwide and contribute to more than

one-third of cancer-related deaths (1). These cancers primarily include

gastric cancer (GC), colorectal cancer (CRC), esophageal squamous

cell carcinoma (ESCC), hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC),

cholangiocarcinoma (CCA), gallbladder cancer (GBC) and pancreatic

cancer. Traditional treatments for GICs, including surgery

intervention, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, targeted therapies

and immunotherapies, have long been the primary approaches for

management (2,3). However, early diagnosis of GICs is

challenging and a proportion of patients are diagnosed in the first

instance with advanced-stage cancer. For patients diagnosed with

advanced-stage cancer, traditional therapies, although essential,

often fall short due to the inherent chemoresistance of GIC cells,

frequently leading to tumor recurrence and distant metastasis

(4), resulting in poor clinical

outcomes for patients with advanced GICs (5).

Ferroptosis, a type of regulated cell death (RCD),

characterized by excessive lipid peroxidation and iron

accumulation, has gained significant attention in recent years

given its critical role in cancer biology (6,7).

Unlike apoptosis or necrosis, ferroptosis occurs due to the buildup

of toxic lipid peroxides, resulting from impaired cellular

antioxidant systems, particularly disruptions in glutathione (GSH)

metabolism (6). Research has

increasingly linked impaired ferroptosis with cancer progression,

suggesting that triggering ferroptosis could be a potential

approach for combating tumors, particularly in overcoming

therapeutic resistance (8-16).

Epigenetic processes, including DNA methylation,

histone modifications and regulatory non-coding (nc)RNAs,

profoundly influence gene expression and can affect cell death

pathways, including ferroptosis (17-19). In GICs, these modifications may

either promote or inhibit ferroptosis, thereby affecting tumor

behavior and treatment responsiveness. For instance, epigenetic

modifications can regulate genes associated with iron metabolism,

antioxidant systems and lipid peroxidation, thereby affecting the

susceptibility of GIC cells to ferroptosis.

Understanding the intricate relationship between

epigenetic regulation and ferroptosis in GICs could reveal novel

therapeutic strategies and targeting epigenetic modifications to

induce ferroptosis may serve as a novel approach to suppress tumor

progression and overcome resistance to conventional treatments. The

present review explores the current understanding of how epigenetic

regulation influences ferroptosis in GICs, highlighting its

implications for cancer progression, treatment and potential future

therapies.

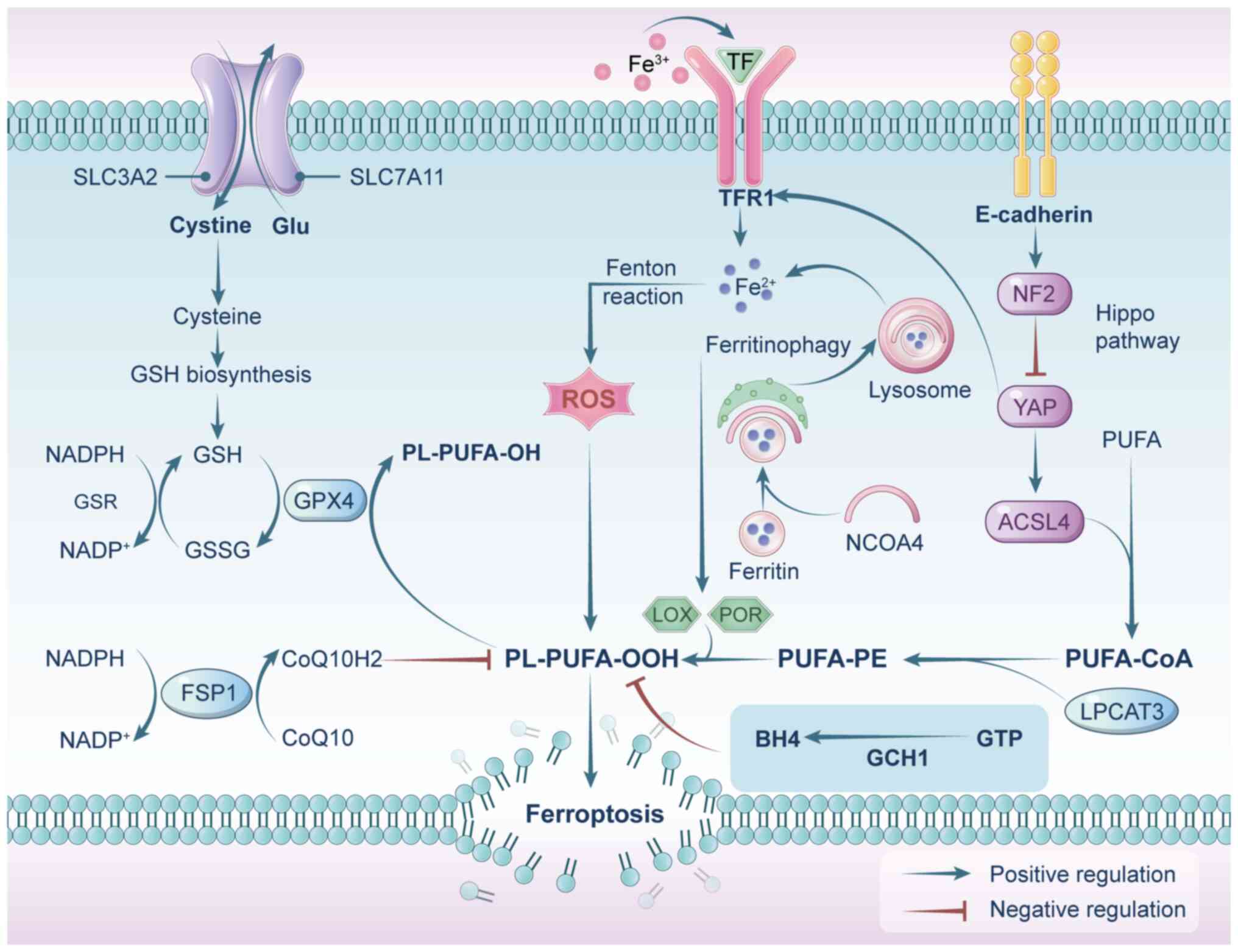

Ferritin, a protein complex responsible for storing

iron, consists of two components: Ferritin heavy chain 1 (FTH1) and

ferritin light chain (FTL). A specialized form of autophagy, known

as ferritinophagy, enhances the susceptibility of a cell to

ferroptosis by increasing the intracellular bioavailability of

Fe2+ (37-40). More specifically, ferritin is

identified by nuclear receptor coactivator 4 (NCOA4), which directs

FTH1 to autophagosomes for lysosomal breakdown, resulting in the

liberation of free iron (Fig. 1)

(39). Reducing lysosomal

activity (41) or downregulating

NCOA4 expression has been demonstrated to block ferroptosis

effectively (37,38). For instance, a relatively

recently discovered ferroptosis inhibitor called Compound 9a can

directly bind to recombinant NCOA4 protein. This binding disrupts

the NCOA4-FTH1 interaction, reducing the intracellular

bioavailability of Fe2+ and ultimately blocking

ferroptosis (42). As a key

regulator of ferroptosis, NCOA4 represents a potential target for

therapeutic intervention. Of note, ferritin and FPN can be

simultaneously upregulated by ATM, thereby rescuing ferroptosis in

multiple cancer cells triggered by cystine deprivation or erastin

(43).

Polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), such as adrenic

acid and arachidonic acid, are highly susceptible to peroxidation.

Enzymes like lysophosphatidylcholine acyltransferase 3 and Acyl-CoA

synthetase long-chain family member 4 (ACSL4) play essential roles

in incorporating these PUFAs into membrane phospholipids, thereby

promoting lipid peroxidation and ferroptotic cell death (44-47) (Fig. 1).

Lipid peroxidation can proceed through two pathways:

Non-enzymatic, driven by free radicals like ROS, and enzymatic

pathways, catalyzed by arachidonate lipoxygenases (ALOXs) and other

enzymes (48-51).

Non-enzymatic lipid peroxidation is a process driven

by free radicals, where ROS initiate the oxidation of PUFAs

(23). The most potent ROS is

the hydroxyl radical. This radical is primarily formed through

Fenton or Fenton-like reactions, which result from the interaction

of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) with free

Fe2+ (52,53).

ALOXs hold a crucial role in catalyzing enzymatic

lipid peroxidation. This family of iron-containing enzymes

encompasses six distinct isoforms (ALOXE3, ALOX5, ALOX12, ALOX12B,

ALOX15 and ALOX15B), which facilitate the dioxygenation of PUFAs

and PUFA-containing lipids within biological membranes to produce a

variety of lipid hydroperoxides in a highly specific manner

(54). This suggests the

potential involvement of ALOXs in initiating ferroptosis. Previous

studies have indicated that certain pharmacological ALOX inhibitors

can effectively hinder ferroptosis (55,56). However, it is noteworthy that the

deletion of ALOX15 did not successfully rescue ferroptosis

triggered by the knockout of glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4)

(57). These results imply the

presence of compensatory mechanisms that could offset the loss of

ALOX15 activity (58). Although

ALOXs are crucial for enzymatic lipid peroxidation, their

contribution to ferroptosis appears context-dependent. ALOX12 is

crucial for p53-induced ferroptosis, but it is not involved in

ferroptosis triggered by erastin or GPX4 inhibitors (59), suggesting differential regulation

of ferroptosis by ALOX isoforms.

Consequently, ALOXs may specifically participate in

certain scenarios within the domain of ferroptosis. To gain a more

precise understanding, further research is needed to clarify the

precise function of ALOXs in ferroptosis. Of note, ALOXs may not be

the only factors governing lipid peroxidation during ferroptosis.

In fact, it has been indicated that cytochrome P450 oxidoreductase

actively contributes to the initiation of lipid peroxidation

(60).

Under physiological conditions, the process of

iron-driven lipid oxidation is carefully regulated by cellular

antioxidant defense systems. A central player in this defense

mechanism is GPX4, a pivotal antioxidant enzyme that plays a

crucial role in reducing membrane lipid hydroperoxides to non-toxic

lipid alcohols (9,61). GPX4 accomplishes this task by

relying on reduced GSH as an essential cofactor (62). Thus, the proper functioning of

GPX4 is intricately linked to the availability of GSH (9,63). GSH is produced through the

combination of three amino acids: Cysteine, glycine and glutamic

acid. Notably, the availability of cysteine stands out as the

primary limiting factor in this biosynthesis process (64,65). Within mammalian cells, the

cystine/glutamate antiporter system xc−,

composed of solute carrier family 7 member 11 (SLC7A11) and SLC3A2,

is responsible for transporting extracellular cystine (the oxidized

form of cysteine) into the cell while releasing intracellular

glutamate in a 1:1 exchange (66,67). The inhibition of system

xc− or GPX4, either pharmacologically or

genetically, triggers lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis (48,68,69). Furthermore, SLC7A11 expression

and function are enhanced by nuclear factor E2-related factor 2

(70) but suppressed by tumor

suppressors, including TP53 (71), BRCA1-associated protein 1 (BAP1)

(72) and beclin 1 (73). Therefore, SLC7A11 serves as a

critical regulatory point in the initiation of ferroptosis, making

it an important factor in the control of this cellular process.

Ferroptosis suppressor protein 1 (FSP1) functions as

a GSH-independent coenzyme Q (CoQ) oxidoreductase and serves as an

essential antioxidant defense system alongside GPX4, making it a

key regulator of ferroptosis (50,51,74). FSP1 utilizes NADH/NADPH to

convert CoQ10 into its reduced, active form, CoQ10H2. In this

reduced form, CoQ10H2 functions as a lipid-soluble antioxidant,

neutralizing free radicals and inhibiting lipid peroxidation,

thereby protecting cells from ferroptosis (50,75). In addition to GPX4/GSH and FSP1,

guanosine triphosphate cyclohydrolase 1 (GCH1) provides an

alternative ferroptosis defense by producing tetrahydrobiopterin

(BH4), which operates independently of the GPX4 system (76).

Epigenetics refers to regulatory mechanisms that

modify gene expression through DNA methylation, histone

modifications and ncRNAs without changing the underlying DNA

sequence (77,78).

In eukaryotic cells, DNA methylation predominantly

occurs at the 5′ position of the cytosine ring within CpG

dinucleotides, exerting regulatory control over gene transcription

by influencing promoters and enhancers (79). This modification involves the

enzymatic actions of DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) and DNA

demethyltransferases (also named TET enzymes) (80-83). CpG dinucleotides are concentrated

in specific regions known as CpG islands (CGIs), and 50-60% of gene

promoters are situated within these CGIs. In healthy cells, CGIs,

particularly those associated with promoters, tend to remain

unmethylated. However, disruptions in DNA methylation processes are

intricately involved in cancer development (84). Promoter hypermethylation-induced

transcriptional silencing of tumor suppressor genes is a common

observation in the majority of cancers (85-87).

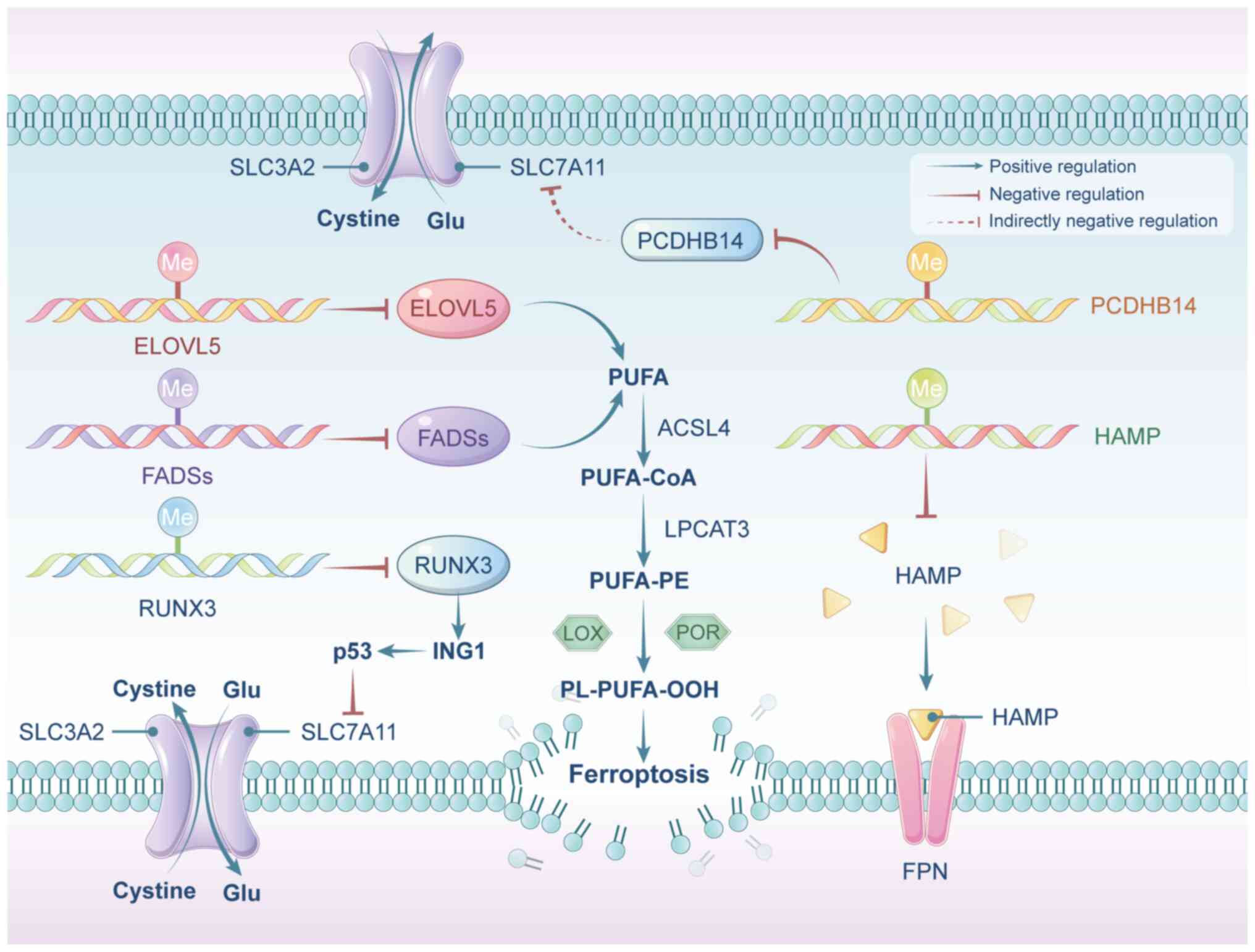

DNA methylation is a key regulatory mechanism that

influences ferroptosis by modulating the expression of critical

genes associated with this pathway (88). In intestinal GC cells, DNA

methylation silences fatty acid desaturase 1 and elongation of very

long-chain fatty acid protein 5, reducing PUFA synthesis and

inhibiting lipid peroxidation, thus suppressing ferroptosis

(89). Similarly, aberrant

hypermethylation of the protocadherin gene 14 promoter in HCC leads

to its inactivation, but p53 activation can reverse this, promoting

ferroptosis by reducing SLC7A11 expression (90). Iron homeostasis is largely

controlled by the HAMP-FPN axis, where HAMP plays a crucial role in

regulating iron absorption, distribution and overall balance

(91). In individuals with HCC,

HAMP expression is suppressed, coinciding with hypermethylation of

a highly conserved CpG island within its promoter region (92,93). In GBC, DNMT1-mediated methylation

downregulates runt-related transcription factor 3 (RUNX3),

impairing ferroptosis. However, activating RUNX3 induces

ferroptosis by enhancing inhibitor of growth 1 transcription, which

in turn downregulates SLC7A11 in a p53-dependent manner (94) (Fig. 2).

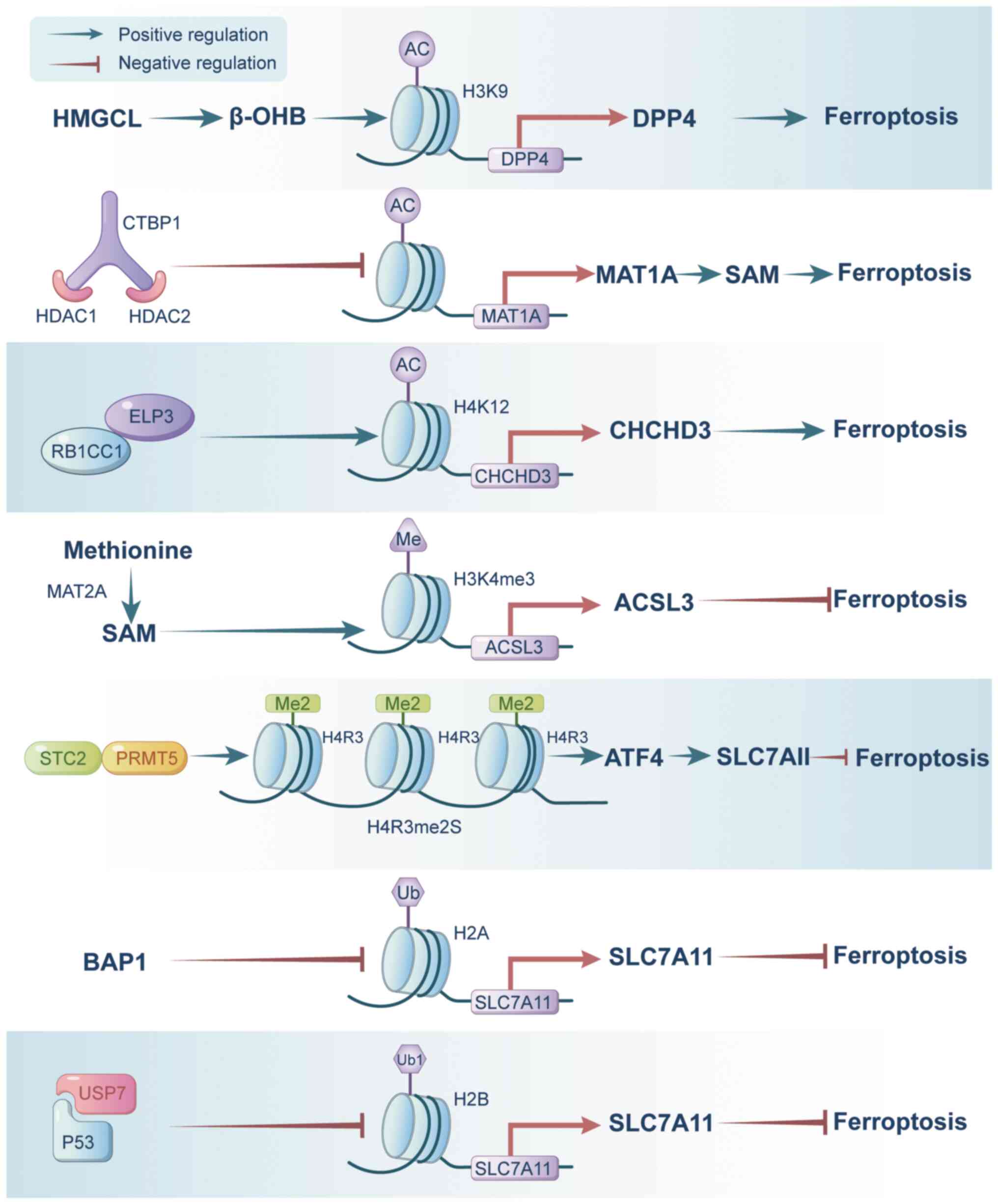

Histone modifications play a key role in shaping

chromatin structure and thus impact gene expression and cancer

development (95,96). This discussion will primarily

center on how histone acetylation, methylation and ubiquitination

contribute to the regulation of ferroptosis.

Histone acetylation modification refers to the

process of adding acetyl groups to histone proteins, which are

crucial for regulating chromatin structure and gene expression.

Acetylation of histone is typically associated with open chromatin

conformation, allowing for increased accessibility of DNA to

transcriptional machinery, and thus, increased gene transcription.

This process is facilitated by histone acetyltransferases, which

add acetyl groups, while histone deacetylases (HDACs) remove them,

leading to chromatin compaction and suppression of gene

expression.

Hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA lyase (HMGCL) catalyzes

the conversion of HMG-CoA into β-hydroxy-butyric acid (β-OHB) and

acetoacetate. Notably, β-OHB acts as a natural inhibitor of HDAC,

promoting elevated histone acetylation levels (97). Recent studies have demonstrated

that HMGCL, via β-OHB, enhances H3K9 acetylation, thereby

upregulating the expression of dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP4). Of

note, DPP4, crucial for intracellular lipid peroxidation, renders

HCC cells susceptible to ferroptosis (98). In addition, C-terminal-binding

protein 1 binds with HDAC1 and HDAC2, creating a transcriptional

complex that downregulates the expression of methionine

adenosyltransferase 1A (MAT1A) through histone deacetylation

modification. Consequently, decreased MAT1A levels reduce

ferroptosis in HCC cells, potentially through direct mechanisms or

by impairing CD8+ T-cell and interferon-γ production, thereby

facilitating the progression of HCC (99). Furthermore, RB1-inducible

coiled-coil 1 facilitates the recruitment of elongator

acetyltransferase complex subunit 3 to enhance H4K12Ac at

ferroptosis-associated enhancers, promoting the transcription of

ferroptosis-associated genes, such as coiled-coil-helix-coile

d-coil-helix domain containing 3 (CHCHD3), and sensitizing cancer

cells to ferroptosis (100)

(Fig. 3).

Histone methylation modification involves the

addition of methyl groups to histone proteins, altering their

structure and affecting gene expression. This process can take

place on various amino acid residues within histone tails,

including lysine and arginine. Depending on the specific site and

extent of methylation, it can either activate or repress gene

transcription.

In the context of ferroptosis, histone methylation

modifications regulate the expression of genes involved in this

process. For instance, MAT2A promotes S-adenosylmethionine

production, leading to elevated H3K4me3 levels at the promoter

region of acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 3, thereby

conferring resistance against ferroptosis in GC cells (101). Similarly, in ESCC,

stanniocalcin 2 induces the activation of protein methyltransferase

5 (PRMT5), which enhances the symmetric dimethylation of histone H4

at arginine 3 (H4R3me2s). This activation, in turn, triggers the

PRMT5-ATF4-SLC3A2/SLC7A11 axis, effectively inhibiting ferroptosis

in ESCC. Furthermore, this process also induces radioresistance by

facilitating DNA damage repair mechanisms (102) (Fig. 3). To date, to the best of our

knowledge, there has been no study on the regulation of ferroptosis

by H3K9me3 in GICs.

Histone ubiquitination modification is a key

epigenetic process that modulates gene expression and various

cellular functions. It involves attaching ubiquitin molecules to

histone proteins, which can alter chromatin structure and affect

transcriptional activity. Additionally, aberrant histone

ubiquitination has been linked to the development of several types

of cancer, including GICs.

SLC7A11, a pivotal gene involved in ferroptosis, is

regulated by histone ubiquitination modification. Tumor

suppressors, such as p53 and BAP, impact the expression of histone

deubiquitination enzymes, thus modulating the histone

ubiquitination modification in the regulatory region of SLC7A11

(Fig. 3). Specifically, BAP1

functions as a nuclear deubiquitinating enzyme that specifically

removes ubiquitin from histone H2A at the SLC7A11 promoter,

resulting in reduced SLC7A11 transcription. This decrease in

SLC7A11 levels leads to increased lipid peroxidation, ultimately

triggering ferroptosis in cancerous cells (72). Similarly, p53 facilitates the

nuclear import of the deubiquitinase USP7, which in turn reduces

H2Bub1 levels at the regulatory region of the SLC7A11 gene, thereby

repressing SLC7A11 expression and promoting ferroptosis in human

hepatoma cells (103).

ncRNAs encompass microRNAs (miRNAs/miRs), long

ncRNAs (lncRNAs) and circular RNAs (circRNAs) (104,105). ncRNAs have been widely

implicated in the regulation of ferroptosis.

miRNAs regulate gene expression at the

post-transcriptional level by binding to the 3′untranslated regions

of mRNA molecules, which either leads to mRNA degradation or blocks

its translation into a protein. They directly modulate the

expression of genes involved in ferroptosis. Specifically, certain

miRNAs may target genes related to lipid metabolism, iron

homeostasis or antioxidant defense systems.

GPX4 is essential for cell survival, as it reduces

harmful lipid peroxides into their non-toxic alcohol forms, thereby

preventing ferroptosis. In CRC and HCC, miR-15a-3p and miR-214-3p

directly target GPX4, suppressing its expression and facilitating

ferroptosis (111,112). Additionally, miRNAs exert an

indirect influence on GPX4. For instance, in CRC, miR-539 activates

the stress-activated protein kinase/c-Jun N-terminal kinase pathway

by targeting TNF-α-induced protein 8, which leads to reduced GPX4

levels and the induction of ferroptosis (113).

Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (NRF2),

an essential transcription factor in the antioxidant response, is

inhibited by the ubiquitin ligase complex formed by Kelch-like

ECH-associated protein 1 (KEAP1) and Cullin 3. NRF2 drives the

expression of antioxidant enzymes, including heme oxygenase 1,

NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 and superoxide dismutase, which

are essential for counteracting ROS, preventing lipid peroxidation

and ultimately inhibiting ferroptosis (114). Several miRNAs, including

miR-124-3p, miR-507, miR-634, miR-450a, miR-129-5p and miR-142-5p,

directly target the 3′-UTR of NRF2 mRNA, leading to decreased NRF2

expression and increased ROS in GC and ESCC (115-117). Furthermore, miRNAs indirectly

regulate NRF2 by targeting KEAP1. In ESCC, HCC and GC cells,

miR-432-3p, miR-200a, miR-141 and miR-328-3p target KEAP1,

resulting in NRF2 upregulation (118-122).

Under conditions of stress, ATF4 expression is

upregulated, leading to the induction of SLC7A11 and subsequent

inhibition of ferroptosis (123,124). Conversely, in HCC, miR-214-3p

directly targets ATF4, thereby promoting ferroptosis (125).

ACSL4 facilitates the incorporation of PUFAs into

phospholipids, thereby increasing the susceptibility of cells to

ferroptosis. By modulating ACSL4, miRNAs play a significant role in

controlling ferroptosis in GICs. For instance, miR-552-5p and

miR-23a-3p specifically target the 3′-UTR of ACSL4 mRNA, leading to

the inhibition of ferroptosis in HCC cells and contributing to

resistance against sorafenib (126,127). In addition, exosomes derived

from cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) transport miR-3173-5p to

gemcitabine-treated pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) cells,

where miR-3173-5p targets ACSL4, thereby inhibiting ferroptosis and

mediating resistance to gemcitabine (128). Similarly, exosomes released by

GC cells deliver miR-214-3p to vascular endothelial cells, where

miR-214-3p targets zinc finger protein A20, resulting in the

negative regulation of ACSL4 and subsequent inhibition of

ferroptosis in these cells (129). Apart from ASCL4, miRNAs have

the potential to modulate additional molecules or pathways linked

to lipid metabolism, influencing the regulation of ferroptosis. The

mevalonate (MVA) pathway, responsible for cholesterol and CoQ10

synthesis, is among the pathways subject to miRNA regulation.

Considering the ability of hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase α subunit

(HADHA) to enhance the expression of key MVA pathway enzymes,

miR-612 may exert a suppressive effect on this pathway by directly

targeting HADHA. This suppression could lead to reduced CoQ10

levels and elevated cellular PUFA levels, which can trigger

ferroptosis in HCC cells (130). The family of ALOXs is regarded

as the key mediator of lipid peroxidation production, which

eventually leads to ferroptosis (56,131). Previous studies have

demonstrated that by targeting ALOX15, exosomal miR-522, secreted

by CAFs, inhibits ferroptosis in GC cells (132).

miRNAs can regulate ferroptosis in GIC cells by

influencing intracellular iron metabolism. Specifically, miR-545

targets TF (133), while

several other miRNAs, such as miR-31, miR-141, miR-145, miR-182,

miR-194, miR-758, miR-22, miR-200a, miR-320 and miR-152, target TFR

in CRC and HCC, thereby reducing TF uptake (134-136). Notably, miR-194 not only

inhibits TFR expression but also inhibits FPN expression in CRC

(134). FPN serves as the

primary means of ferrous iron export (137), and is targeted by miR-150 and

miR-485-3p in HCC (138). In

CRC, miR-133a targets FTL, one of the components of ferritin

responsible for iron storage (134). In addition, miR-19a targets

iron-responsive element-binding protein 2, thus suppressing

ferroptosis in CRC (139).

These intricate regulatory interactions highlight the multifaceted

role of miRNAs in modulating ferroptosis through the regulation of

intracellular iron dynamics in GICs. Table I gives a comprehensive and

detailed overview of how miRNAs regulate ferroptosis in GICs.

lncRNAs are long RNA molecules typically >200

nucleotides in length, which have been recognized as key regulators

of ferroptosis in tumor cells (140). These molecules exhibit a dual

capability in modulating ferroptosis in GICs: They can directly

target key genes or molecules associated with ferroptosis or

indirectly modulate them by acting as miRNA sponges (141). For instance, lncRNAs have been

shown to directly or indirectly modulate the expression of SLC7A11,

impacting ferroptosis in HCC and GC (142-145), as well as modulate the

expression of GPX4, influencing ferroptosis in ESCC, CCA and liver

cancer cells (112,146,147). Additionally, lncRNAs can

directly bind to molecules such as FSP1 or Keap1, thereby

inhibiting ferroptosis in GICs (148,149).

Furthermore, specific lncRNAs, such as

URB1-antisense RNA 1 (AS1), have been implicated in driving

ferritin phase separation, which helps lower cellular free iron

levels and suppressed sorafenib-induced ferroptosis in HCC

(150). Additionally, lncRNA

NEAT1 promotes the expression of Myo-inositol oxygenase, leading to

increased ROS production and a reduction in intracellular NADPH and

GSH levels, thereby intensifying ferroptosis in HCC (151,152). Another crucial enzyme involved

is Stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1 (SCD1), which converts saturated fatty

acids into monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFAs), affecting cellular

membrane composition and susceptibility to lipid

peroxidation-induced ferroptosis (153-156). In colon cancer, lncRNA

LINC01606 has been reported to enhance SCD1 expression by competing

for miR-423-5p, thereby protecting cancer cells from ferroptosis

(157).

Furthermore, in hypoxic tumor microenvironments

(TMEs), lncRNAs are crucial regulators of ferroptosis. For

instance, hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF-1α) activation leads to

the transcriptional upregulation of lncRNA PMAN, which enhances the

output of ELAV-like RNA binding protein 1 (ELAVL1) in the

cytoplasm. ELAVL1 then stabilizes SLC7A11 mRNA, increasing its

expression and preventing ferroptosis in GC peritoneal metastasis

(145). Similarly, HIF-1α

induces lncRNA-CBSLR, which eventually protects GC cells from

ferroptosis and confers chemoresistance to GC cells under hypoxic

conditions by modulating the stability of cystathionine β-synthase

(CBS) mRNA and ACSL4 protein (158).

Furthermore, lncRNAs can utilize exosomes as

carriers to regulate ferroptosis in target cells. Exosomes secreted

by CAFs carry lncRNA DACT3-AS1 into GC cells, where it targets the

miR-181a-5p/sirtuin 1 (SIRT1) axis, inducing ferroptosis and

sensitizing GC cells to oxaliplatin (159). These examples illustrate the

diverse mechanisms through which lncRNAs modulate ferroptosis in

GICs. Table II provides a more

comprehensive overview.

circRNAs, which are single-stranded, covalently

closed ncRNA molecules, exhibit distinct characteristics from other

ncRNAs (160).

In GICs, numerous circRNAs have been identified as

crucial regulators of ferroptosis. circRNAs typically function as

miRNA sponges, indirectly influencing the expression of their

target mRNAs (161-164), including ferroptosis-associated

genes like GPX4 (165) and

SLC7A11. These genes are well-established critical regulators of

ferroptosis and studies have shown that several circRNAs modulate

their expression by sequestering miRNAs, thereby playing a

significant role in controlling ferroptosis in GICs (108,166-171). Notably, circRHOT1 facilitates

the recruitment of KAT5 (acetyltransferase Tip60), increasing

H3K27-mediated acetylation of the GPX4 gene, which promotes its

transcription and inhibits ferroptosis in GC (172).

In addition to acting as miRNA sponges, circRNAs can

directly bind to RNA-binding proteins involved in ferroptosis

signaling pathways, thereby modulating ferroptosis in GICs. For

instance, ELAVL1, an RNA-binding protein, enhances the translation

efficiency of target mRNAs by interacting with AU-rich elements in

their 3′UTRs (173). circRHBDD1

upregulates SCD expression by promoting ELAVL1 binding to SCD mRNA,

leading to the suppression of ferroptosis in CRC (174).

A recent study also elucidated the mechanism by

which circRNA may contribute to the regulation of ferroptosis.

circPDE3B was shown to function as both an miR-516b-5p sponge,

resulting in increased CBS expression, and as a direct binder with

RNA-binding protein heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein K,

resulting in the stabilization of SLC7A11. Consequently, this dual

action of circPDE3B ultimately resulted in the suppression of

ferroptosis in ESCC (175). A

comprehensive and detailed overview of how circRNAs regulate

ferroptosis in GICs is provided in Table III.

It is worth noting that certain key genes or

molecules related to ferroptosis are not only regulated by a single

epigenetic modification but may be influenced by multiple

epigenetic modifications simultaneously. For instance, in cancer

cells, the upstream region of the GPX4 gene exhibits low DNA

methylation, high levels of H3K4 trimethylation and H3K27

acetylation (176), indicating

that GPX4 is regulated not only by DNA methylation but also by

histone modifications. These modifications work together to create

a more complex regulatory framework for ferroptosis.

Aurora kinase A (AURKA), a serine/threonine kinase

responsible for regulating mitotic spindle function (177,178), is another key player.

miR-4715-3p can directly target the 3′-UTR of AURKA, suppressing

its expression, which in turn inhibits GPX4 and promotes

ferroptosis (179). However, in

upper gastrointestinal cancers, miR-4715-3p itself is downregulated

due to hypermethylation of its gene promoter (179). This epigenetic interplay

further complicates the regulation of ferroptosis in these types of

cancer.

ROS are critical in driving ferroptosis and have

been implicated in regulating epigenetic processes, including DNA

methylation and histone acetylation (180,181). In cancer cells, elevated ROS

levels enhance DNA hypermethylation, resulting in the repression of

tumor suppressor and antioxidant genes, which promotes cancer cell

proliferation under oxidative stress (180,181). A notable example is the

epigenetic silencing of RUNX3, a well-established tumor suppressor,

which is frequently downregulated in cancer cells due to

ROS-induced DNA hypermethylation of its promoter. This methylation

process is mediated by DNMT1 and HDAC1, whose expression and

activity are upregulated in response to ROS. DNMT1 and HDAC1 bind

to the RUNX3 promoter, driving its hypermethylation and silencing

(182). Importantly, treatment

with the ROS scavenger N-acetylcysteine or the DNMT1 inhibitor

5-aza-2-deoxycytidine has been shown to reverse this epigenetic

modification, highlighting the potential for therapeutic

intervention. Similarly, ROS-induced promoter hypermethylation has

been observed in other tumor suppressor genes. In CRC, ROS enhances

the methylation of the caudal type homeobox-1 (CDX1) promoter,

leading to its suppression and facilitating cancer progression

(183). In HCC, ROS elevates

Snail expression, which promotes hypermethylation of the E-cadherin

promoter, thereby contributing to tumor growth (184). Overall, ROS-induced epigenetic

modifications play a significant role in cancer progression.

Targeting ROS represents a promising therapeutic strategy-not only

to reverse these epigenetic changes but also to enhance ferroptosis

sensitivity in GICs. Future research should further explore the

mechanisms of ROS-mediated epigenetic silencing and develop

ROS-modulating therapies to improve treatment outcomes in these

malignancies.

The TME is a complex ecosystem consisting of immune

cells, stromal cells, tumor cells and various other elements. Among

immune cells, CD8+ T-cells play a crucial role by releasing

interferon-γ, which suppresses SLC7A11 expression while enhancing

ACSL4 levels, thereby facilitating ferroptosis in cancer cells

(185,186).

CAFs, another critical component of the TME,

significantly influence both innate and adaptive immunity (187). CAFs suppress ferroptosis in GC

cells by secreting miR-522 (132). In GICs, anoctamin 1 inhibits

ferroptosis by activating the PI3K-Akt signaling pathway, promoting

tumor progression and facilitating CAF recruitment via TGF-β

release (188). This disrupts

CD8+ T cell-driven anti-tumor responses, contributing to

immunotherapy resistance (188). These findings highlight the

intricate interactions between cancer cells, immune cells and CAFs

in regulating ferroptosis.

One unique feature of the TME is its metabolic

profile, marked by high lactate accumulation and restricted glucose

supply (189,190). Cancer cells exploit lactate to

counteract ferroptosis by either increasing MUFA-phospholipid

synthesis or enhancing the acidity of the TME (191,192).

The reversible nature of epigenetic modifications

in cancer makes them a valuable target for therapeutic strategies

(193). Since ferroptosis plays

a key role in limiting cancer progression, leveraging epigenetic

mechanisms to regulate ferroptosis has gained interest as a

potential treatment strategy, particularly for GICs. Epigenetic

drugs have shown promising therapeutic potential in targeting

ferroptosis-related cancers, including GICs. A series of

preclinical and clinical studies have explored the efficacy of

various epigenetic modulators, such as HDAC inhibitors (HDACi),

enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2) inhibitors and IDH inhibitors,

in regulating ferroptosis and improving cancer therapy outcomes

(Table IV).

Preclinical research has demonstrated that the

HDACi BEBT-908 can induce ferroptosis in colon adenocarcinoma by

hyperacetylating p53, a critical tumor suppressor protein involved

in ferroptosis regulation (194). CRC is notoriously resistant to

ferroptosis, but preclinical studies have shown that vorinostat, an

HDACi, significantly sensitizes CRC cells to ferroptosis. When

combined with ferroptosis inducers, vorinostat synergistically

suppresses CRC growth (195).

Additionally, entinostat, another HDACi, has been shown to promote

ferroptosis in GC cells (196).

These studies suggest that HDACis may increase ferroptosis

susceptibility in GICs, representing a potential strategy for

overcoming resistance to therapy.

The enhanced effectiveness of HDACis when combined

with other anticancer treatments has led to the development of

combination therapies in clinical trials. A phase I/II clinical

trial (NCT00943449) assessed the efficacy of combining the HDACi

resminostat with sorafenib in patients with HCC who exhibited

radiologically confirmed progression after first-line sorafenib

therapy. The combination treatment achieved a 62.5%

progression-free survival rate following six cycles of treatment

(12 weeks), whereas resminostat monotherapy resulted in a 12.5%

progression-free survival rate (197). Additionally, a notable phase II

clinical trial (NCT03250273) demonstrated that entinostat combined

with nivolumab (a programmed cell death-1 inhibitor) yielded

sustained responses in a limited group of patients with PDAC

(198). Furthermore, the

combination of entinostat with immunotherapeutic agents is being

tested in ongoing clinical trials for melanoma, non-small cell lung

cancer and CRC (ENCORE-601; NCT02437136). These studies highlight

the growing clinical interest in HDACis as key modulators of

ferroptosis and immune response, highlighting their potential to

enhance treatment efficacy across multiple cancer types.

Currently, most approved HDACis are pan-HDACis,

which can lead to significant side effects such as hematologic

toxicity (199),

gastrointestinal toxicity, cardiovascular toxicity (200), metabolic disturbances (201), fatigue and weakness (202), and immune-related side effects

(203). Therefore, there has

been a growing focus on developing selective HDACis to reduce the

toxic side effects of pan-HDACis. Another innovative strategy

involves proteolysis-targeting chimeras (PROTACs), small molecules

that promote the selective degradation of target proteins within

cells (204). HDAC-targeting

PROTACs are an emerging therapeutic strategy, offering several

advantages over traditional HDACi, including improved safety and

the potential to overcome drug resistance (205). Furthermore, it is noteworthy

that an increasing body of research demonstrates the effcacy of

combining low doses of HDACi with other medications to address the

issue of adverse effects.

EZH2 is a histone methyltransferase that represses

gene expression through H3K27 trimethylation (H3K27me3).

Preclinical studies suggested that EZH2 contributes to the

inhibition of ferroptosis in HCC by downregulating TFR2 expression

via H3K27me3 modifications. Of note, combining tazemetostat, an

EZH2 inhibitor, with sorafenib in sorafenib-resistant HCC cells

promotes ferroptosis and significantly enhances the therapeutic

effects of sorafenib (206).

This combination therapy approach demonstrates the potential of

EZH2 inhibition in overcoming resistance to standard treatments and

improving ferroptosis induction in GICs.

Alterations in IDH, particularly IDH1 and IDH2, are

common in several types of cancer, including CCA (207-209). These mutations result in the

accumulation of 2-hydroxyglutarate (210), a byproduct that suppresses

α-ketoglutarate-dependent dioxygenases, such as histone and DNA

demethylases (211-213). This disrupts cellular

differentiation and contributes to cancer development. Preclinical

studies suggest that mutant IDH1 can promote cancer cell survival

by supporting mitochondrial function and antioxidant defenses, thus

reducing the sensitivity to ferroptosis. Pharmacologic inhibition

of mutant IDH1 with ivosidenib has been shown to synergize with

conventional chemotherapeutics, enhancing ferroptosis sensitivity

in PDAC cells (214).

A phase III randomized clinical trial (NCT02989857)

demonstrated that Ivosidenib has significant overall survival

benefits in patients with advanced CCA harboring IDH1 mutations

(215). A current clinical

trial (NCT05209074) is testing the combination of ivosidenib with

chemotherapy in PDAC, demonstrating the promising potential of IDH

inhibitors in improving ferroptosis sensitivity and cancer

treatment outcomes.

In addition to the use of specific inhibitors,

epigenetic modifications such as histone modifications have been

identified as crucial regulators of ferroptosis in GICs. For

instance, anisomycin, an activator of the p38-MAPK pathway,

enhances histone H3 phosphorylation at serine 10 on the NCOA4

promoter. NCOA4 is crucial for ferroptosis as it facilitates

ferritinophagy, a mechanism that liberates iron from ferritin,

triggering lipid peroxidation. In HCC cells, anisomycin-induced

NCOA4 expression sensitizes the cells to ferroptosis, suggesting

that targeting epigenetic modifications like histone

phosphorylation could serve as a potential approach to overcoming

ferroptosis resistance in certain cancer types (216).

ncRNAs, particularly those contained in exosomes,

are essential regulators of ferroptosis and significantly impact

the survival and progression of GIC cells. These exosomal ncRNAs

can deliver miRNAs, lncRNAs and circRNAs directly to cancer cells,

offering significant therapeutic potential for GIC. Preclinical

studies have shown that exosomal lncRNAs, such as DACT3-AS1 derived

from CAFs, can be transferred to GC cells. There, DACT3-AS1 induces

ferroptosis through its regulation of the miR-181a-5p/SIRT1 pathway

(159). Additionally, heat

shock protein family B (small) member 1 (HSPB1) inhibits

ferroptosis by reducing iron uptake through TFRC (217). An interesting study utilized

small extracellular vesicles (sEV) to deliver miR-654-5p, resulting

in engineered vesicles (m654-sEV). The findings revealed that

m654-sEV efficiently transfers miR-654-5p to HCC cells, targeting

HSPB1 and amplifying sorafenib-induced ferroptosis (218). This combined approach using

m654-sEV and sorafenib holds the potential for overcoming sorafenib

resistance in HCC, thereby improving therapeutic efficacy. These

findings suggest that ncRNAs, which promote ferroptosis in GICs,

could be packaged into exosomes or sEVs to target and treat GICs

more effectively. Investigating the role of ncRNAs in modulating

ferroptosis in GICs may offer valuable therapeutic insights and

contribute to the development of more effective clinical strategies

for treating these cancers.

Numerous preclinical investigations and clinical

trials have explored the possibility of combining epigenetic drugs

with ferroptosis inducers in GICs. Sorafenib, a multi-target kinase

inhibitor that acts on Raf kinases, has been approved by the US

Food and Drug Administration as a first-line therapy for advanced

HCC (219). Research has shown

that sorafenib can induce ferroptosis in HCC cells by suppressing

the activity of system Xc−; therefore, sorafenib acts as

a ferroptosis inducer like erastin (220). However, the clinical

effectiveness of sorafenib in HCC is often compromised by both

primary and acquired resistance. A phase I/II clinical trial

involving patients with HCC who had experienced disease progression

with first-line sorafenib treatment investigated the combination of

sorafenib with the HDACi resminostat. The study reported a 62.5%

progression-free survival rate after six treatment cycles (12

weeks, primary endpoint) with the combination therapy, whereas

resminostat alone resulted in a 12.5% progression-free survival

rate (197). These results

indicate that epigenetic drugs combined with sorafenib can overcome

the resistance of HCC cells to sorafenib. Preclinical studies have

shown that lncRNAs play a crucial role in sorafenib resistance in

HCC, and lncRNA metastasis-associated lung adenocarcinoma

transcript 1 (MALAT1) is dysregulated in sorafenib-resistant HCC

cells. MALAT1 contributes to sorafenib resistance in HCC cells by

stabilizing SLC7A11 mRNA through direct interaction with ELAVL1,

promoting its translocation to the cytoplasm and subsequently

inhibiting sorafenib-induced ferroptosis (221). The combination of a MALAT1

inhibitor with sorafenib markedly improved the therapeutic

effectiveness of sorafenib in both in vitro and in

vivo models of HCC (221).

Ferroptosis has emerged as a critical mechanism in

the progression and treatment of GICs. The epigenetic regulation of

ferroptosis, involving DNA methylation, histone modifications and

ncRNAs, represents a complex but promising avenue for therapeutic

intervention. These modifications collectively influence key genes

involved in ferroptosis, including GPX4 and AURKA, which

underscores the potential of targeting epigenetic regulators to

modulate ferroptosis in GIC therapy. Current findings underscore

the importance of epigenetic drugs in modulating ferroptosis and

their potential to enhance therapeutic efficacy in GICs. However,

there remain significant challenges in translating these insights

into widely effective clinical therapies.

There is a need for more extensive research to map

the full range of epigenetic regulators involved in ferroptosis

across different types of GICs. Advanced technologies such as

single-cell RNA sequencing (seq) and multi-omics approaches,

including single-cell assay for transposase-accessible chromatin

seq (222) and chromatin

immunoprecipitation-seq (223),

may provide a high-resolution view of the epigenetic landscape

governing ferroptosis. These techniques can help elucidate

context-specific regulatory mechanisms and identify novel

therapeutic targets.

As the knowledge of the epigenetic mechanisms

governing ferroptosis expands, there is potential for the

development of more selective and effective epigenetic modulators.

The application of CRISPR/Cas9-based epigenome editing could enable

precise modifications of ferroptosis-related genes, allowing

researchers to dissect their functional roles and develop targeted

epigenetic therapies (224).

Furthermore, artificial intelligence (AI)-driven drug discovery and

high-throughput screening platforms could accelerate the

identification of small-molecule inhibitors or activators that

modulate ferroptosis through epigenetic mechanisms (225).

Identifying epigenetic markers that predict a

tumor's sensitivity to ferroptosis-inducing therapies could be

crucial for personalizing treatment. Techniques such as DNA

methylation arrays and bisulfite sequencing may be employed to

assess the methylation status of ferroptosis-related genes

(226,227). In addition, liquid biopsy

approaches using circulating tumor DNA and epigenetic profiling of

cell-free DNA may provide minimally invasive strategies for

monitoring ferroptosis sensitivity and treatment response in

real-time (228).

Resistance to ferroptosis-based therapies remains a

significant barrier. Investigating how epigenetic alterations

contribute to ferroptosis resistance could reveal new targets for

overcoming this challenge, particularly in refractory GICs. The

integration of CRISPR screens and epigenetic drug libraries could

help identify key regulatory elements driving resistance (229). Furthermore, single-cell

transcriptomics and spatial transcriptomics could provide insights

into intra-tumoral heterogeneity and epigenetic adaptations that

enable cancer cells to evade ferroptosis (230).

In conclusion, epigenetic regulation plays a

crucial role in modulating ferroptosis sensitivity in GICs,

offering a promising avenue for therapy. While epigenetic drugs

enhance ferroptosis and inhibit tumor growth, challenges remain in

clinical translation. Advancing technologies like single-cell

sequencing, CRISPR/Cas9 and AI-driven drug discovery may help

overcome resistance and enable personalized ferroptosis-targeted

therapies.

Not applicable.

LG, LW, SL, HY and PJ conceived the study. LG and

LW interpreted the relevant literature and wrote the original

manuscript. SZ, SX and XC prepared figures and tables. YZ and FL

revised the manuscript. SL, HY and PJ reviewed and edited the

manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final

manuscript. Data authentication is not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Not applicable.

This research was funded by the National Natural Science

Foundation of China (grant nos. 81602846 and 82272253), the Natural

Science Foundation of Shandong Province (grant no. ZR2021MH145),

the Taishan Scholar Project of Shandong Province (grant no.

tsqn201812159), the Science and Technology Program of Traditional

Chinese Medicine of Shandong Province (grant no. M-2022066), the

China International Medical Foundation (grant no. Z-2018-35-2002)

and the Key R&D Program of Jining (grant no. 2023YXNS003).

|

1

|

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M,

Soerjomataram I, Jemal A and Bray F: Global cancer statistics 2020:

GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36

cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 71:209–249. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Donohoe CL and Reynolds JV: Neoadjuvant

treatment of locally advanced esophageal and junctional cancer: The

evidence-base, current key questions and clinical trials. J Thorac

Dis. 9(Suppl 8): S697–S704. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Schmidt B, Lee HJ, Ryeom S and Yoon SS:

Combining bevacizumab with radiation or chemoradiation for solid

tumors: A review of the scientific rationale, and clinical trials.

Curr Angiogenes. 1:169–179. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Madden EC, Gorman AM, Logue SE and Samali

A: Tumour cell secretome in chemoresistance and tumour recurrence.

Trends Cancer. 6:489–505. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Smyth EC, Nilsson M, Grabsch HI, van

Grieken NC and Lordick F: Gastric cancer. Lancet. 396:635–648.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Dixon SJ, Lemberg KM, Lamprecht MR, Skouta

R, Zaitsev EM, Gleason CE, Patel DN, Bauer AJ, Cantley AM, Yang WS,

et al: Ferroptosis: An iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell

death. Cell. 149:1060–1072. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Jia M, Qin D, Zhao C, Chai L, Yu Z, Wang

W, Tong L, Lv L, Wang Y, Rehwinkel J, et al: Redox homeostasis

maintained by GPX4 facilitates STING activation. Nat Immunol.

21:727–735. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Zhou B, Liu J, Kang R, Klionsky DJ,

Kroemer G and Tang D: Ferroptosis is a type of autophagy-dependent

cell death. Semin Cancer Biol. 66:89–100. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Yang WS, SriRamaratnam R, Welsch ME,

Shimada K, Skouta R, Viswanathan VS, Cheah JH, Clemons PA, Shamji

AF, Clish CB, et al: Regulation of ferroptotic cancer cell death by

GPX4. Cell. 156:317–331. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Yu Y, Xie Y, Cao L, Yang L, Yang M, Lotze

MT, Zeh HJ, Kang R and Tang D: The ferroptosis inducer erastin

enhances sensitivity of acute myeloid leukemia cells to

chemotherapeutic agents. Mol Cell Oncol. 2:e10545492015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Louandre C, Ezzoukhry Z, Godin C, Barbare

JC, Mazière JC, Chauffert B and Galmiche A: Iron-dependent cell

death of hepatocellular carcinoma cells exposed to sorafenib. Int J

Cancer. 133:1732–1742. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Louandre C, Marcq I, Bouhlal H, Lachaier

E, Godin C, Saidak Z, François C, Chatelain D, Debuysscher V,

Barbare JC, et al: The retinoblastoma (Rb) protein regulates

ferroptosis induced by sorafenib in human hepatocellular carcinoma

cells. Cancer Lett. 356:971–977. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Sun X, Niu X, Chen R, He W, Chen D, Kang R

and Tang D: Metallothionein-1G facilitates sorafenib resistance

through inhibition of ferroptosis. Hepatology. 64:488–500. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Sun X, Ou Z, Chen R, Niu X, Chen D, Kang R

and Tang D: Activation of the p62-Keap1-NRF2 pathway protects

against ferroptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Hepatology.

63:173–184. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Eling N, Reuter L, Hazin J, Hamacher-Brady

A and Brady NR: Identification of artesunate as a specific

activator of ferroptosis in pancreatic cancer cells. Oncoscience.

2:517–532. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Zhu S, Zhang Q, Sun X, Zeh HJ III, Lotze

MT, Kang R and Tang D: HSPA5 regulates ferroptotic cell death in

cancer cells. Cancer Res. 77:2064–2077. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Berger SL, Kouzarides T, Shiekhattar R and

Shilatifard A: An operational definition of epigenetics. Genes Dev.

23:781–783. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Holliday R: The inheritance of epigenetic

defects. Science. 238:163–170. 1987. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Zhou S, Liu J, Wan A, Zhang Y and Qi X:

Epigenetic regulation of diverse cell death modalities in cancer: a

focus on pyroptosis, ferroptosis, cuproptosis, and disulfidptosis.

J Hematol Oncol. 17:222024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Stockwell BR, Friedmann Angeli JP, Bayir

H, Bush AI, Conrad M, Dixon SJ, Fulda S, Gascón S, Hatzios SK,

Kagan VE, et al: Ferroptosis: A regulated cell death nexus linking

metabolism, redox biology, and disease. Cell. 171:273–285. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Kuang F, Liu J, Tang D and Kang R:

Oxidative damage and antioxidant defense in ferroptosis. Front Cell

Dev Biol. 8:5865782020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Torti SV and Torti FM: Iron and cancer:

More ore to be mined. Nat Rev Cancer. 13:342–355. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Hassannia B, Vandenabeele P and Vanden

Berghe T: Targeting ferroptosis to iron out cancer. Cancer Cell.

35:830–849. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Yang WS, Kim KJ, Gaschler MM, Patel M,

Shchepinov MS and Stockwell BR: Peroxidation of polyunsaturated

fatty acids by lipoxygenases drives ferroptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci

USA. 113:E4966–E4975. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Suttner DM and Dennery PA: Reversal of

HO-1 related cytoprotection with increased expression is due to

reactive iron. FASEB J. 13:1800–1809. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Yang WS and Stockwell BR: Synthetic lethal

screening identifies compounds activating Iron-dependent,

nonapoptotic cell death in oncogenic-RAS-harboring cancer cells.

Chem Biol. 15:234–245. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Wang Y, Liu Y, Liu J, Kang R and Tang D:

NEDD4L-mediated LTF protein degradation limits ferroptosis. Biochem

Biophys Res Commun. 531:581–587. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Drakesmith H, Nemeth E and Ganz T: Ironing

out Ferroportin. Cell Metab. 22:777–787. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Donovan A, Lima CA, Pinkus JL, Pinkus GS,

Zon LI, Robine S and Andrews NC: The iron exporter

ferroportin/Slc40a1 is essential for iron homeostasis. Cell Metab.

1:191–200. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Donovan A, Brownlie A, Zhou Y, Shepard J,

Pratt SJ, Moynihan J, Paw BH, Drejer A, Barut B, Zapata A, et al:

Positional cloning of zebrafish ferroportin1 identifies a conserved

vertebrate iron exporter. Nature. 403:776–781. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Nemeth E, Tuttle MS, Powelson J, Vaughn

MB, Donovan A, Ward DM, Ganz T and Kaplan J: Hepcidin regulates

cellular iron efflux by binding to ferroportin and inducing its

internalization. Science. 306:2090–2093. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

De Domenico I, Ward DM, Langelier C,

Vaughn MB, Nemeth E, Sundquist WI, Ganz T, Musci G and Kaplan J:

The molecular mechanism of hepcidin-mediated ferroportin

down-regulation. Mol Biol Cell. 18:2569–2578. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Qiao B, Sugianto P, Fung E,

Del-Castillo-Rueda A, Moran-Jimenez MJ, Ganz T and Nemeth E:

Hepcidin-induced endocytosis of ferroportin is dependent on

ferroportin ubiquitination. Cell Metab. 15:918–924. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Ross SL, Tran L, Winters A, Lee KJ, Plewa

C, Foltz I, King C, Miranda LP, Allen J, Beckman H, et al:

Molecular mechanism of hepcidin-mediated ferroportin

internalization requires ferroportin lysines, not tyrosines or

JAK-STAT. Cell Metab. 15:905–917. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Geng N, Shi BJ, Li SL, Zhong ZY, Li YC,

Xua WL, Zhou H and Cai JH: Knockdown of ferroportin accelerates

erastin-induced ferroptosis in neuroblastoma cells. Eur Rev Med

Pharmacol Sci. 22:3826–3836. 2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Tang Z, Jiang W, Mao M, Zhao J, Chen J and

Cheng N: Deubiquitinase USP35 modulates ferroptosis in lung cancer

via targeting ferroportin. Clin Transl Med. 11:e3902021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Gao M, Monian P, Pan Q, Zhang W, Xiang J

and Jiang X: Ferroptosis is an autophagic cell death process. Cell

Res. 26:1021–1032. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Hou W, Xie Y, Song X, Sun X, Lotze MT, Zeh

HJ III, Kang R and Tang D: Autophagy promotes ferroptosis by

degradation of ferritin. Autophagy. 12:1425–1428. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Mancias JD, Wang X, Gygi SP, Harper JW and

Kimmelman AC: Quantitative proteomics identifies NCOA4 as the cargo

receptor mediating ferritinophagy. Nature. 509:105–109. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Wang YQ, Chang SY, Wu Q, Gou YJ, Jia L,

Cui YM, Yu P, Shi ZH, Wu WS, Gao G and Chang YZ: The Protective

role of mitochondrial ferritin on Erastin-induced ferroptosis.

Front Aging Neurosci. 8:3082016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Torii S, Shintoku R, Kubota C, Yaegashi M,

Torii R, Sasaki M, Suzuki T, Mori M, Yoshimoto Y, Takeuchi T and

Yamada K: An essential role for functional lysosomes in ferroptosis

of cancer cells. Biochem J. 473:769–777. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Fang Y, Chen X, Tan Q, Zhou H, Xu J and Gu

Q: Inhibiting ferroptosis through disrupting the NCOA4-FTH1

interaction: A new mechanism of action. ACS Cent Sci. 7:980–989.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Chen PH, Wu J, Ding CC, Lin CC, Pan S,

Bossa N, Xu Y, Yang WH, Mathey-Prevot B and Chi JT: Kinome screen

of ferroptosis reveals a novel role of ATM in regulating iron

metabolism. Cell Death Differ. 27:1008–1022. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

44

|

Kagan VE, Mao G, Qu F, Angeli JP, Doll S,

Croix CS, Dar HH, Liu B, Tyurin VA, Ritov VB, et al: Oxidized

arachidonic and adrenic PEs navigate cells to ferroptosis. Nat Chem

Biol. 13:81–90. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Doll S, Proneth B, Tyurina YY, Panzilius

E, Kobayashi S, Ingold I, Irmler M, Beckers J, Aichler M, Walch A,

et al: ACSL4 dictates ferroptosis sensitivity by shaping cellular

lipid composition. Nat Chem Biol. 13:91–98. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

46

|

Yuan H, Li X, Zhang X, Kang R and Tang D:

Identification of ACSL4 as a biomarker and contributor of

ferroptosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 478:1338–1343. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Dixon SJ, Winter GE, Musavi LS, Lee ED,

Snijder B, Rebsamen M, Superti-Furga G and Stockwell BR: Human

haploid cell genetics reveals roles for lipid metabolism genes in

nonapoptotic cell death. ACS Chem Biol. 10:1604–1609. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Conrad M and Pratt DA: The chemical basis

of ferroptosis. Nat Chem Biol. 15:1137–1147. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Yin H, Xu L and Porter NA: Free radical

lipid peroxidation: Mechanisms and analysis. Chem Rev.

111:5944–5972. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Doll S, Freitas FP, Shah R, Aldrovandi M,

da Silva MC, Ingold I, Goya Grocin A, Xavier da Silva TN, Panzilius

E, Scheel CH, et al: FSP1 is a glutathione-independent ferroptosis

suppressor. Nature. 575:693–698. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Bersuker K, Hendricks JM, Li Z, Magtanong

L, Ford B, Tang PH, Roberts MA, Tong B, Maimone TJ, Zoncu R, et al:

The CoQ oxidoreductase FSP1 acts parallel to GPX4 to inhibit

ferroptosis. Nature. 575:688–692. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Ayala A, Muñoz MF and Argüelles S: Lipid

peroxidation: Production, metabolism, and signaling mechanisms of

malondialdehyde and 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal. Oxid Med Cell Longev.

2014:3604382014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Fenton HJH: LXXIII.-Oxidation of tartaric

acid in presence of iron. J Chemical Soc Transactions. 65:899–910.

1894. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Haeggström JZ and Funk CD: Lipoxygenase

and leukotriene pathways: Biochemistry, biology, and roles in

disease. Chem Rev. 111:5866–5898. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Li Y, Maher P and Schubert D: A role for

12-lipoxygenase in nerve cell death caused by glutathione

depletion. Neuron. 19:453–463. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Seiler A, Schneider M, Förster H, Roth S,

Wirth EK, Culmsee C, Plesnila N, Kremmer E, Rådmark O, Wurst W, et

al: Glutathione peroxidase 4 senses and translates oxidative stress

into 12/15-lipoxygenase dependent- and AIF-mediated cell death.

Cell Metab. 8:237–248. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Brütsch SH, Wang CC, Li L, Stender H,

Neziroglu N, Richter C, Kuhn H and Borchert A: Expression of

inactive glutathione peroxidase 4 leads to embryonic lethality, and

inactivation of the Alox15 gene does not rescue such knock-in mice.

Antioxid Redox Signal. 22:281–293. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

58

|

Jiang X, Stockwell BR and Conrad M:

Ferroptosis: Mechanisms, biology and role in disease. Nat Rev Mol

Cell Biol. 22:266–282. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Chu B, Kon N, Chen D, Li T, Liu T, Jiang

L, Song S, Tavana O and Gu W: ALOX12 is required for p53-mediated

tumour suppression through a distinct ferroptosis pathway. Nat Cell

Biol. 21:579–591. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Zou Y, Li H, Graham ET, Deik AA, Eaton JK,

Wang W, Sandoval-Gomez G, Clish CB, Doench JG and Schreiber SL:

Cytochrome P450 oxidoreductase contributes to phospholipid

peroxidation in ferroptosis. Nat Chem Biol. 16:302–309. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Xie Y, Kang R, Klionsky DJ and Tang D:

GPX4 in cell death, autophagy, and disease. Autophagy.

19:2621–2638. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Yant LJ, Ran Q, Rao L, Van Remmen H,

Shibatani T, Belter JG, Motta L, Richardson A and Prolla TA: The

selenoprotein GPX4 is essential for mouse development and protects

from radiation and oxidative damage insults. Free Radic Biol Med.

34:496–502. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Brigelius-Flohé R and Maiorino M:

Glutathione peroxidases. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1830:3289–3303.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

64

|

Meister A: Glutathione metabolism. Methods

Enzymol. 251:3–7. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Lu SC: Regulation of glutathione

synthesis. Mol Aspects Med. 30:42–59. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

66

|

Cao JY and Dixon SJ: Mechanisms of

ferroptosis. Cell Mol Life Sci. 73:2195–2209. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Sato H, Tamba M, Ishii T and Bannai S:

Cloning and expression of a plasma membrane cystine/glutamate

exchange transporter composed of two distinct proteins. J Biol

Chem. 274:11455–11458. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Sato H, Shiiya A, Kimata M, Maebara K,

Tamba M, Sakakura Y, Makino N, Sugiyama F, Yagami K, Moriguchi T,

et al: Redox imbalance in cystine/glutamate transporter-deficient

mice. J Biol Chem. 280:37423–37429. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Friedmann Angeli JP, Schneider M, Proneth

B, Tyurina YY, Tyurin VA, Hammond VJ, Herbach N, Aichler M, Walch

A, Eggenhofer E, et al: Inactivation of the ferroptosis regulator

Gpx4 triggers acute renal failure in mice. Nat Cell Biol.

16:1180–1191. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Chen D, Tavana O, Chu B, Erber L, Chen Y,

Baer R and Gu W: NRF2 is a major target of ARF in p53-independent

tumor suppression. Mol Cell. 68:224–232.e4. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Jiang L, Kon N, Li T, Wang SJ, Su T,

Hibshoosh H, Baer R and Gu W: Ferroptosis as a p53-mediated

activity during tumour suppression. Nature. 520:57–62. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Zhang Y, Shi J, Liu X, Feng L, Gong Z,

Koppula P, Sirohi K, Li X, Wei Y, Lee H, et al: BAP1 links

metabolic regulation of ferroptosis to tumour suppression. Nat Cell

Biol. 20:1181–1192. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Song X, Zhu S, Chen P, Hou W, Wen Q, Liu

J, Xie Y, Liu J, Klionsky DJ, Kroemer G, et al: AMPK-mediated BECN1

phosphorylation promotes ferroptosis by directly blocking system

Xc-activity. Curr Biol. 28:2388–2399.e5. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

74

|

Yang M, Tsui MG, Tsang JKW, Goit RK, Yao

KM, So KF, Lam WC and Lo ACY: Involvement of FSP1-CoQ(10)-NADH and

GSH-GPx-4 pathways in retinal pigment epithelium ferroptosis. Cell

Death Dis. 13:4682022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Zeng F, Chen X and Deng G: The

anti-ferroptotic role of FSP1: Current molecular mechanism and

therapeutic approach. Mol Biomed. 3:372022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Kraft VAN, Bezjian CT, Pfeiffer S,

Ringelstetter L, Müller C, Zandkarimi F, Merl-Pham J, Bao X,

Anastasov N, Kössl J, et al: GTP Cyclohydrolase

1/Tetrahydrobiopterin counteract ferroptosis through lipid

remodeling. ACS Cent Sci. 6:41–53. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Cheng Y, He C, Wang M, Ma X, Mo F, Yang S,

Han J and Wei X: Targeting epigenetic regulators for cancer

therapy: Mechanisms and advances in clinical trials. Signal

Transduct Target Ther. 4:622019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Logie E, Van Puyvelde B, Cuypers B,

Schepers A, Berghmans H, Verdonck J, Laukens K, Godderis L,

Dhaenens M, Deforce D, et al: Ferroptosis induction in multiple

myeloma cells triggers DNA methylation and histone modification

changes associated with cellular senescence. Int J Mol Sci.

22:122342021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Bird A: DNA methylation patterns and

epigenetic memory. Genes Dev. 16:6–21. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Parry A, Rulands S and Reik W: Active

turnover of DNA methylation during cell fate decisions. Nat Rev

Genet. 22:59–66. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

81

|

Tahiliani M, Koh KP, Shen Y, Pastor WA,

Bandukwala H, Brudno Y, Agarwal S, Iyer LM, Liu DR, Aravind L, et

al: Conversion of 5-methylcytosine to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in

mammalian DNA by MLL partner TET1. Science. 324:930–935. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Ito S, D'Alessio AC, Taranova OV, Hong K,

Sowers LC and Zhang Y: Role of Tet proteins in 5mC to 5hmC

conversion, ES-cell self-renewal and inner cell mass specification.

Nature. 466:1129–1133. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Ito S, Shen L, Dai Q, Wu SC, Collins LB,

Swenberg JA, He C and Zhang Y: Tet proteins can convert

5-methylcytosine to 5-formylcytosine and 5-carboxylcytosine.

Science. 333:1300–1303. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Robertson KD: DNA methylation and human

disease. Nat Rev Genet. 6:597–610. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Esteller M: Epigenetic gene silencing in

cancer: The DNA hypermethylome. Hum Mol Genet. 16(Spec No 1):

R50–R59. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Veigl ML, Kasturi L, Olechnowicz J, Ma AH,

Lutterbaugh JD, Periyasamy S, Li GM, Drummond J, Modrich PL,

Sedwick WD, et al: Biallelic inactivation of hMLH1 by epigenetic

gene silencing, a novel mechanism causing human MSI cancers. Proc

Natl Acad Sci USA. 95:8698–8702. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

Klutstein M, Nejman D, Greenfield R and

Cedar H: DNA methylation in cancer and aging. Cancer Res.

76:3446–3450. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Liu Z, Zhao Q, Zuo ZX, Yuan SQ, Yu K,

Zhang Q, Zhang X, Sheng H, Ju HQ, Cheng H, et al: Systematic

analysis of the aberrances and functional implications of

ferroptosis in cancer. iScience. 23:1013022020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

89

|

Lee JY, Nam M, Son HY, Hyun K, Jang SY,

Kim JW, Kim MW, Jung Y, Jang E, Yoon SJ, et al: Polyunsaturated

fatty acid biosynthesis pathway determines ferroptosis sensitivity

in gastric cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 117:32433–32442. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

90

|

Liu Y, Ouyang L, Mao C, Chen Y, Li T, Liu

N, Wang Z, Lai W, Zhou Y, Cao Y, et al: PCDHB14 promotes

ferroptosis and is a novel tumor suppressor in hepatocellular

carcinoma. Oncogene. 41:3570–3583. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

91

|

Bolotta A, Abruzzo PM, Baldassarro VA,

Ghezzo A, Scotlandi K, Marini M and Zucchini C: New insights into

the Hepcidin-ferroportin axis and iron homeostasis in iPSC-derived

cardiomyocytes from Friedreich's ataxia patient. Oxid Med Cell

Longev. 2019:76230232019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

92

|

Udali S, Castagna A, Corbella M,

Ruzzenente A, Moruzzi S, Mazzi F, Campagnaro T, De Santis D,

Franceschi A, Pattini P, et al: Hepcidin and DNA promoter

methylation in hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur J Clin Invest.

48:e128702018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

93

|

Udali S, Guarini P, Ruzzenente A,

Ferrarini A, Guglielmi A, Lotto V, Tononi P, Pattini P, Moruzzi S,

Campagnaro T, et al: DNA methylation and gene expression profiles

show novel regulatory pathways in hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin

Epigenetics. 7:432015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

94

|

Cai C, Zhu Y, Mu J, Liu S, Yang Z, Wu Z,

Zhao C, Song X, Ye Y, Gu J, et al: DNA methylation of RUNX3

promotes the progression of gallbladder cancer through repressing

SLC7A11-mediated ferroptosis. Cell Signal. 108:1107102023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

95

|

Cedar H and Bergman Y: Linking DNA

methylation and histone modification: Patterns and paradigms. Nat

Rev Genet. 10:295–304. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

96

|

Du Q, Luu PL, Stirzaker C and Clark SJ:

Methyl-CpG-binding domain proteins: Readers of the epigenome.

Epigenomics. 7:1051–1073. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

97

|

Shimazu T, Hirschey MD, Newman J, He W,

Shirakawa K, Le Moan N, Grueter CA, Lim H, Saunders LR, Stevens RD,

et al: Suppression of oxidative stress by β-hydroxybutyrate, an

endogenous histone deacetylase inhibitor. Science. 339:211–214.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

98

|

Cui X, Yun X, Sun M, Li R, Lyu X, Lao Y,

Qin X and Yu W: HMGCL-induced β-hydroxybutyrate production

attenuates hepatocellular carcinoma via DPP4-mediated ferroptosis

susceptibility. Hepatol Int. 17:377–392. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

99

|

Li Y, Hu G, Huang F, Chen M, Chen Y, Xu Y

and Tong G: MAT1A suppression by the CTBP1/HDAC1/HDAC2

transcriptional complex induces immune escape and reduces

ferroptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Lab Invest.

103:1001802023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

100

|

Xue X, Ma L, Zhang X, Xu X, Guo S, Wang Y,

Qiu S, Cui J, Guo W, Yu Y, et al: Tumour cells are sensitised to

ferroptosis via RB1CC1-mediated transcriptional reprogramming. Clin

Transl Med. 12:e7472022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

101

|

Ma M, Kong P, Huang Y, Wang J, Liu X, Hu

Y, Chen X, Du C and Yang H: Activation of MAT2A-ACSL3 pathway

protects cells from ferroptosis in gastric cancer. Free Radic Biol

Med. 181:288–299. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

102

|

Jiang K, Yin X, Zhang Q, Yin J, Tang Q, Xu

M, Wu L, Shen Y, Zhou Z, Yu H, et al: STC2 activates PRMT5 to

induce radioresistance through DNA damage repair and ferroptosis

pathways in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Redox Biol.

60:1026262023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

103

|

Wang Y, Yang L, Zhang X, Cui W, Liu Y, Sun

QR, He Q, Zhao S, Zhang GA, Wang Y, et al: Epigenetic regulation of

ferroptosis by H2B monoubiquitination and p53. EMBO Rep.

20:e475632019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

104

|

Quinn JJ and Chang HY: Unique features of

long non-coding RNA biogenesis and function. Nat Rev Genet.

17:47–62. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

105

|

Guttman M and Rinn JL: Modular regulatory

principles of large Non-coding RNAs. Nature. 482:339–346. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

106

|

Ni H, Qin H, Sun C, Liu Y, Ruan G, Guo Q,

Xi T, Xing Y and Zheng L: MiR-375 reduces the stemness of gastric

cancer cells through triggering ferroptosis. Stem Cell Res Ther.

12:3252021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

107

|

Mao SH, Zhu CH, Nie Y, Yu J and Wang L:

Levobupivacaine Induces Ferroptosis by miR-489-3p/SLC7A11 Signaling

in Gastric Cancer. Front Pharmacol. 12:6813382021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

108

|

Dong X, Chen X, Zhao Y, Wu Q and Ren Y:

CircTMEM87A promotes the tumorigenesis of gastric cancer by

regulating the miR-1276/SLC7A11 axis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol.

39:121–132. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

109

|

Martino E, Balestrieri A, Aragona F,

Bifulco G, Mele L, Campanile G, Balestrieri ML and D'Onofrio N:

MiR-148a-3p promotes colorectal cancer cell ferroptosis by

targeting SLC7A11. Cancers (Basel). 15:43422023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

110

|

Elrebehy MA, Abdelghany TM, Elshafey MM,

Gomaa MH and Doghish AS: miR-509-5p promotes colorectal cancer cell

ferroptosis by targeting SLC7A11. Pathol Res Pract. 247:1545572023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

111

|

Liu L, Yao H, Zhou X, Chen J, Chen G, Shi

X, Wu G, Zhou G and He S: MiR-15a-3p regulates ferroptosis via

targeting glutathione peroxidase GPX4 in colorectal cancer. Mol

Carcinog. 61:301–310. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

112

|

He GN, Bao NR, Wang S, Xi M, Zhang TH and

Chen FS: Ketamine induces ferroptosis of liver cancer cells by

Targeting lncRNA PVT1/miR-214-3p/GPX4. Drug Des Devel Ther.

15:3965–3978. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

113

|

Yang Y, Lin Z, Han Z, Wu Z, Hua J, Zhong

R, Zhao R, Ran H, Qu K, Huang H, et al: miR-539 activates the

SAPK/JNK signaling pathway to promote ferropotosis in colorectal

cancer by directly targeting TIPE. Cell Death Discov. 7:2722021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

114

|

Dodson M, Castro-Portuguez R and Zhang DD: