Introduction

Intestinal ischemia-reperfusion (IIR) is an acute

condition often caused by cardiopulmonary bypass, small intestinal

transplantation, intestinal obstruction, mesenteric ischemia,

incarcerated hernia, septic shock or trauma with a mortality rate

of >50% and a global incidence rate of >0.001% (1-3).

In America, 30,000 individuals per year experience

ischemia-reperfusion (4).

Furthermore, acute mesenteric ischemia alone accounts for 0.1% of

all hospital admissions globally (5). Despite improvements in treatment

modalities, the mortality rate of acute mesenteric ischemia is

50-80% (5). Therefore,

investigating novel therapeutic strategies to improve the treatment

of IIR is necessary.

During IIR, epithelial cell death and mucosal injury

disrupts the integrity of the mucosal barrier, which increases

intestinal permeability, resulting in systemic inflammatory

response syndrome or shock (6,7).

Previous studies have shown that non-apoptotic cell death

mechanisms, including ferroptosis, pyroptosis and necroptosis,

serve key roles in the pathological process of acute and chronic

gut injury (8,9).

Pyroptosis, a type of proinflammatory programmed

cell death, occurs in multiple types of cells, such as enterocytes,

oligodendrocytes and vascular endothelial cells including those in

the digestive system, under several stress conditions such as

mitochondrial oxidative stress and endoplasmic reticulum stress,

and in response to a large number of metabolites such as

trimethylamine N-oxide and methylglyoxal (10-13). Pyroptotic cells release several

inflammatory cytokines and danger-associated molecular patterns

(DAMPs) through gasdermin D (GSDMD) pores or ruptured membranes,

resulting in the activation of immune cells such as alveolar

macrophages and non-immune cells such as lung endothelial cells

that in turn generate further proinflammatory cytokines (10). This exacerbates inflammation and

induces further pyroptosis, which leads to a positive feedback loop

and host mortality (10,14). For example, interleukin (IL)-1β

and IL-18, released from pyroptotic cells, recruit and activate

immune cells by binding to IL-receptors. This triggers the

production of several proinflammatory cytokines, such as tumor

necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and interferon-γ (IFN-γ), which amplifies

the proinflammatory response (10). IFN-γ and TNF-α induce pyroptosis

and inflammatory responses through the activation of the janus

kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription 1/IFN

regulatory factor 1 pathway. However, blocking the activation of

IFN-γ and TNF-α using neutralizing antibodies ameliorates

infectious and autoinflammatory diseases by inhibiting inflammation

and tissue damage (15,16). In addition, as a DAMP,

high-mobility group box 1 not only activates macrophages to

generate inflammatory cytokines, but it also induces pyroptosis in

macrophages, which further exacerbates the inflammatory response

(14,17). Therefore, the initiation of

excessive pyroptosis leads to severe inflammatory consequences,

whereas its inhibition ameliorates the pathogenic effects of

inflammatory diseases. It is generally accepted that the NOD-, LRR-

and pyrin domain-containing protein 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome, which

is an inflammatory regulatory complex, contributes to the

initiation of pyroptosis (18-20). Once the assembly of inflammasomes

is complete, procaspase-1 is recruited and cleaved, and then its

active fragment not only cleaves pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18 into their

activated forms but it also transforms GSDMD into C- and N-terminal

fragments, which triggers pyroptosis (21,22). In addition, previous studies

demonstrate that NLRP3-GSDMD-dependent pyroptosis contributes to

IIR injury (23-25). Therefore, inhibiting NLRP3

pathway-mediated pyroptosis might be a promising therapeutic option

for IIR injury.

Mitochondrial dysfunction is considered to be one of

the principal contributors to IIR-induced injury. When IIR occurs,

mitochondria inhibit adenosine triphosphate generation, produce

reactive oxygen species (ROS) and increase the amount of

mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) in the blood circulation, thereby

aggravating cell damage (26,27). Recent studies reveal that

mitochondrial dysfunction contributes to NLRP3 inflammasome

activation-induced pyroptosis during pathological processes, such

as septic shock and hepatic encephalopathy (28,29). Mitochondria-associated membrane

formation during IIR activates the NLRP3 inflammasome and induces

pyroptosis (30). Therefore,

mitochondrial dysfunction may contribute to NLRP3 inflammasome

activation-induced pyroptosis in IIR injury. Sirtuin-3 (SIRT3),

which is mainly expressed in mitochondria, is usually reduced in

models of IR, including IIR (31-33). The activation of SIRT3 protects

against IIR injury by ameliorating mitochondrial damage (34). However, whether SIRT3 can

ameliorate NLRP3 inflammasome activation-triggered pyroptosis by

regulating mitochondrial function during IIR has not been fully

elucidated.

Honokiol (HKL), a natural small-molecule polyphenol

extracted from the herb Magnolia officinalis, has been

identified to possess antitumor, anti-inflammatory and antioxidant

properties (35-37). Furthermore, HKL can directly

target SIRT3 and increase SIRT3 expression levels (38). A previous study demonstrates that

HKL can protect mitochondrial integrity by activating SIRT3 in

cisplatin-induced acute kidney injury (39,40). Therefore, the present study

investigated whether HKL can also ameliorate IIR injury.

Subsequently, the present study investigated the underlying

mechanisms of HKL and its effects on IIR in a rat model of small

IIR and in IEC-6 epithelial cells.

Materials and methods

Rat model of small IIR

In total, 96 8-week-old adult male Sprague-Dawley

rats [Shanghai Jihui Laboratory Animal Breeding Co., Ltd.; license

no. SCXK(Hu)2022-0009] weighing 250-300 g were kept in an

environment with a stable humidity (40-70%) and temperature

(22±2°C), with a time-controlled lighting system and unrestricted

access to water and standard commercial food. The time-controlled

lighting system had a 12 h light/dark cycle. All animal

experimental protocols were approved by the ethics committee of the

Southwest Medical University (Luzhou, China; approval no.

20221128-001). After the rats had adapted to their environment for

5 days, 24 rats were used to investigate different durations of

ischemia to determine the duration that gave the most notable

alteration in intestinal damage after IIR. The rats were randomly

divided into groups (n=6/group), namely: The sham; ischemia for 30

min and reperfusion for 2 h; ischemia for 45 min and reperfusion

for 2 h; or ischemia for 60 min and reperfusion for 2 h groups. The

rat IIR model was established as previously described (41,42). Prior to surgery, a mixture

containing ketamine (55 mg/kg) and xylazine (7.5 mg/kg) was

injected once to anesthetize the rats via intraperitoneal injection

(duration, ~70 min). To ensure that the rats were anesthetized, 1

min after injection the rats were rolled onto their sides once

every min until the righting reflex was lost. Subsequently, 1 min

after the righting reflex was lost, a toe pinch test was applied to

each rat to determine whether the withdrawal reflex was present.

Loss of the righting reflex and toe pinch response was used to

confirm that the rats were anesthetized. A midline laparotomy was

carried out, and then the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) was

exposed and clamped for 30, 45 or 60 min at 22±2°C. During the

surgical period and ischemia, a tail pinch test was carried out

once every 5 min and the palpebral reflex was observed to monitor

the degree of anesthesia. If the rats reacted to the tail pinch

test or the palpebral reflex was observed, anesthesia was

maintained with injections of 20 mg/kg ketamine. After ischemia,

the clamp was removed, and the skin was sutured after the

intestines returned to a pink color. Subsequently, reperfusion was

performed for 2 h, and the rats were allowed to wake up. In the

sham group, the rats underwent the same procedure without SMA

occlusion. In the subsequent experiments, the SMA was clamped for

45 min at 22±2°C, and 42 rats were randomly divided into seven

groups (n=6/group) to determine the appropriate dose of HKL,

namely: The sham; IIR; IIR with 0.5 mg/kg HKL (MedChemExpress) (IIR

+ 0.5 HKL); IIR with 1 mg/kg HKL (IIR + 1 HKL); IIR with 5 mg/kg

HKL (IIR + 5 HKL); IIR with 10 mg/kg HKL (IIR + 10 HKL); or IIR

with 20 mg/kg HKL (IIR + 20 HKL) groups. In addition, 30 rats were

randomly divided into three groups (n=10/group),namely: The sham;

IIR; and IIR + 10 HKL groups, which were used for

immunohistochemical (IHC), intestinal fatty acid-binding protein

(i-FABP), IL-1β and IL-18 tests (n=6/group) or western blotting

tests (n=4/group). For the HKL treatment groups, a solvent mixture

of DMSO and PBS at a volume ratio 1:1 was prepared. HKL was

dissolved in the solvent mixture to prepare a 10 mg/ml stock

solution. The HKL stock solution was added to the solvent mixture

of DMSO and PBS to prepare working solutions according to the

injection dose and total mass of each rat. Each rat was

administered an intraperitoneal injection of 1 ml HKL solution once

daily for 7 days prior to surgery (43-45). All animals from the sham and IIR

groups were given an equal volume of the solvent mixture of DMSO

and PBS via an intraperitoneal injection. Following reperfusion,

rats were anesthetized using a mixture of ketamine (55 mg/kg) and

xylazine (7.5 mg/kg), and peripheral blood was collected from the

abdominal aorta to euthanize all animals. Rats were confirmed dead

when the absence of a heartbeat, pulse, breathing and corneal

reflex was observed for >3 min. The rats were then dissected,

and the small intestine collected.

Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining

and pathological score

For pathological experiments, all of the small

intestinal tissues were fixed in 4% polyformaldehyde for 24 h at

4°C and embedded in paraffin. Following cooling at -20°C, 4

µm-thick sections were prepared using a tissue slicer and

stained with H&E solution (cat. no. G1005-500ML; Wuhan

Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.). The sections were stained using

hematoxylin for 5 min at room temperature. After washing with

water, the sections were stained using eosin for 15 sec at room

temperature. Following staining, the morphology of the small

intestine was observed using a light microscope (magnification,

×100; Eclipse E100; Nikon Corporation). The destruction of the

small intestinal tissues was evaluated using Chiu's score (46) and ImageJ software (version 1.8.0;

National Institutes of Health). Two independent observers blinded

to the groups determined the Chiu's score.

IHC staining

Small intestinal tissues were fixed in 4%

polyformaldehyde for 24 h at 4°C and embedded in paraffin.

Following cooling at −20°C, sections (4 µm-thick) of

intestinal tissue were prepared and dewaxed using BioDewax and

Clear Solution (cat. no. G1128-500ML; Wuhan Servicebio Technology

Co., Ltd.) and hydrated in ethanol at different concentrations.

Following antigen retrieval for 20 min at 95°C, the tissue sections

were incubated with 3% BSA (cat. no. GC305010-5 g; Wuhan Servicebio

Technology Co., Ltd.) for 30 min at room temperature. Subsequently,

the tissues were incubated with primary antibodies: Anti-tight

junction protein 1 (ZO-1; 1:250; cat. no. 164329; Chengdu

Zen-Bioscience Co., Ltd.); anti-occludin (1:250; cat. no. 502601;

Chengdu Zen-Bioscience Co., Ltd.); anti-NLRP3 (1:300; cat. no.

GB114320-100; Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.); anti-SIRT3

(1:100; cat. no. GB115590-100; Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co.,

Ltd.); anti-cleaved-Caspase-1 (cleavedCleaved-Casp1; 1:200; cat.

no. YC0003; ImmunoWay Biotechnology Company); and anti-GSDMD

N-terminal domain (GSDMD-N; 1:100; cat. no. DF13758; Affinity

Biosciences) at 4°C overnight. The tissue samples were then

incubated with a HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody

(1:1,000; cat. no. GB23303; Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.)

at room temperature for 50 min and visualized using a DAB substrate

chromogen kit (cat. no. G1212-200T; Wuhan Servicebio Technology

Co., Ltd.), after the cell nuclei were stained with hematoxylin

solution for 5 min at room temperature. All images were captured

using an inverted light microscope (magnification, ×100 and ×400;

OLYMPUS IX73; Olympus Corporation) and analyzed using ImageJ

software (version 1.8.0; National Institutes of Health).

Hypoxia/reoxygenation (H/R) model and

treatments

A rat intestinal IEC-6 epithelial cell line was

provided by Wuhan Sunncell Biotechnology Co., Ltd. IEC-6 cells were

cultured in DMEM (cat. no. 11965092; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.) with 10% FBS (cat. no. 13011-8611;Zhejiang Tianhang

Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) and 10 mg/l insulin at 37°C in a 5%

CO2 atmosphere.

To establish the H/R model in vitro, IEC-6

cells were maintained in a Water-Jacketed CO2 incubator

commercial hypoxia system (Thermo Scientific™ 8000; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.; 94% N2, 5% CO2 and 1%

O2) for 12 h at 37°C. Following hypoxia, IEC-6 cells

were transferred to a normoxic incubator (74% N2, 5%

CO2 and 21% O2) and further cultured for 6 h

at 37°C (47). For the treatment

groups, a solvent mixture of DMSO and PBS at a 1:1 volume ratio was

prepared. HKL was dissolved in the solvent mixture to prepare a 10

mM stock solution. The HKL stock solution was then further diluted

in the solvent mixture of DMSO and PBS to prepare working solutions

according the dose and total volume required. The

mitochondria-targeted antioxidant (Mito-TEMPO; MedChemExpress) was

dissolved in deionized water. HKL (1, 5, 10, 20 or 40 µM) or

Mito-TEMPO (200 µM) solutions were used to treat cells at

37°C for 12 h prior to H/R.

Cell transfection

Small interfering (si)-RNA targeting SIRT3 mRNA

(siSIRT3; sense, 5′-GGA CGG AUA AGA CAG ACU AUG DTD T-3′;

antisense, 5′-CAUA GUC UGU CUU AUC CGU CCD TDT-3′; Shanghai

GenePharma Co., Ltd.) and the scrambled negative control (con)

siRNA (siNC; sense, 5′-ACG UGG GAG AAG AUC GUA CAA DTD T-3′;

antisense, 5′-UUG UAC GAU CUU CUC CCA CGU DTD T-3′; Shanghai

GenePharma Co., Ltd.) were transfected into cells using

Lipofectamine® 2000 (cat. no. 11668019; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.). Briefly, IEC-6 cells (6×105

cells/well) were seeded in a 6-well plate at 37°C overnight for

attachment before being transfected using 12.5 µl of

Lipofectamine® 2000 with 25 nM siSIRT3 or siNC for 48 h

at 37°C. After transfection, cells were immediately used for

subsequent experiments.

Reverse transcription-quantitative

polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

After exposure to H/R and HKL, IEC-6 cells were

collected and treated with TRIzol® reagent (cat. no.

15596-026; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Reverse transcription

was performed using M-MLV Reverse Transcriptase (cat. no. 28025013;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) at 42°C for 1 h and 70°C for 10

min. qPCR was performed using TB Green Fast qPCR Mix (cat. no.

RR430A; Takara Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) under the following

conditions: Initial denaturation at 95°C for 15 sec; followed by 40

cycles of 95°C for 5 sec and 60°C for 30 sec. β-actin was used as a

con. The relative expression of SIRT3 mRNA was calculated using the

2−ΔΔcq method (48).

The primer sequences used in the present study were: SIRT3 forward,

5′-GCC TCT ACA GCA ACC TTC-3′ and reverse, 5′-AAG TAG TGA GCG ACA

TTG G-3′; β-actin forward, 5′-CCA TTG AAC ACG GCA TTG-3′ and

reverse, 5′-TAC GAC CAG AGG CAT ACA-3′.

Western blotting

To extract total protein, IEC-6 cells or small

intestinal tissues were treated with RIPA buffer (cat. no. F1053;

Wuhan Frekang Technology Co., Ltd. The protein concentration was

determined using a BCA protein assay kit (cat. no. K001; Wuhan Fine

Biotech Co., Ltd.). Following separation using 10% SDS-PAGE (20

µg of total protein loaded per lane), the proteins were

transferred to a PVDF membrane (cat. no. 36126ES; Shanghai Yeasen

Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) and blocked using 5% non-fat milk for 2 h

at room temperature. The membrane was incubated with primary

antibodies at 4°C overnight. The primary antibodies used were:

Anti-ZO-1 (1:500; cat. no. GB111402-100; Wuhan Servicebio

Technology Co., Ltd.); anti-occludin (1:800; cat. no. GB11149-50;

Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.); anti-SIRT3 (1:300; cat. no.

GB115590-100; Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.); anti-NLRP3

(1:400; cat. no. GB114320-100; Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co.,

Ltd.); anti-cleaved-Casp1 (1:800; cat. no. AF4005; Affinity

Biosciences); anti-Casp1 (1:1,000; cat. no. AF5418; Affinity

Biosciences); anti-GSDMD (1:500; cat. no. GB114198-50; Wuhan

Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.); anti-GSDMD-N (1:900; cat. no.

DF13758; Affinity Biosciences); and anti-β-actin (1:4,000; cat. no.

30102ES60; Shanghai Yeasen Biotechnology Co., Ltd.). Following

washing with tris buffered saline with tween (0.05%), the membranes

were treated with a HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (1:10,000;

cat. no. GB23303; Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.) at room

temperature for 1 h. The target signals were visualized using a

super ECL detection kit (cat. no. 36208ES60; Shanghai Yeasen

Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) and quantified using ImageJ software

(version 1.8.0; National Institutes of Health).

i-FABP, IL-1β and IL-18 assay

Levels of i-FABP in the serum and culture

supernatant as well as serum IL-1β and IL-18 levels were analyzed

using rat i-FABP ELISA (cat. no. CSB-E08026r; Cusabio Technology,

LLC), rat IL-1β ELISA (cat. no. CSB-E08055r; Cusabio Technology,

LLC) and rat IL-18 ELISA (cat. no. CSB-E04610r; Cusabio Technology,

LLC) kits (49). The standards

and samples were incubated with the biotin-conjugated antibody for

1 h at 37°C, followed by an incubation with HRP-streptavidin for 1

h at 37°C. The tetramethylbenzidine substrate was subsequently

added to all wells. After terminating the reaction, the absorbance

of each well was tested using a microplate reader (Berthold

Tristar2 S LB 942) at 450 nm.

Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) assay

LDH levels in cell supernatants from each treatment

group were tested using a LDH assay kit (cat. no. C0016; Beyotime

Institute of Biotechnology). Briefly, cell culture plates were

centrifuged at 400 × g for 5 min at room temperature, and the

culture supernatants were obtained. The culture supernatants of

IEC-6 cells were treated with the LDH detection working solution

for 30 min at room temperature in a darkroom. The absorbance was

then determined using a microplate reader (Berthold Tristar2 S LB

942) at 490/630 nm.

Cell viability assay

A Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8; cat. no. C0037;

Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) was used to determine IEC-6

cell viability. Briefly, IEC-6 cells (4.5×103

cells/well) were seeded in a 96-well plate for 24 h at 37°C.

Following hypoxia for 12 h and reoxygenation for 6 h at 37°C, 10

µl of CCK-8 solution was added for 1 h. Subsequently, the

absorbance of each group was analyzed using a microplate reader

(Berthold Tristar2 S LB 942) at 450 nm.

Immunofluorescent (IF) staining

Following hypoxia for 12 h and reoxygenation for 6 h

at 37°C, IEC-6 cells were fixed with cold 4% paraformaldehyde

solution for 25 min at 4°C, followed by permeabilization with 1%

Triton X-100 working solution. The cells were then treated with 3%

BSA (cat. no. GC305010-5g; Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.)

at room temperature for 45 min. Anti-NLRP3 (1:300; cat. no.

GB114320-100; Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.);

anti-cleaved-Casp1 (1:100; cat. no. YC0003; ImmunoWay); or

anti-GSDMD-N (1:200; cat. no. DF13758; Affinity Biosciences)

antibodies were incubated with cells at 4°C overnight.

Subsequently, an Alexa Fluor® 488-conjugated secondary

antibody (1:400; cat. no. GB25303; Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co.,

Ltd.) was added for 1 h at 37°C. Cell nuclei were stained using a

DAPI solution (cat. no. G1012; Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co.,

Ltd.) for 10 min at room temperature. All images were captured

using an Eclipse C1 Nikon fluorescence microscope (magnification,

×200; Nikon Corporation).

Mitochondrial morphology and

mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψm) analysis

To assess mitochondrial morphology, IEC-6 cells were

washed and stained with Mito-Tracker Green (final concentration,

100 nM; cat. no. C1048; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) for 20

min at 37°C. An A1+R Nikon confocal microscope(Nikon

Corporation)was then used to observe mitochondrial morphology

(magnification, ×1,000).

For the Δψm analysis, IEC-6 cells were

labeled with 1 ml of tetramethylrhodamine ethyl ester perchlorate

solution (final concentration, 10 µM; cat. no. C2001S;

Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) at 37°C for 35 min. Following

washing, the Δψm was determined using an Eclipse C1

Nikon fluorescence microscope (magnification, ×200; Nikon

Corporation).

Mitochondrial ROS analysis

To assess mitochondrial ROS, IEC-6 cells were

co-labeled with MitoSOX Red (final concentration, 5 µM; cat.

no. S0061S; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) and Mito-Tracker

Green (final concentration, 100 nM; cat. no. C1048; Beyotime

Institute of Biotechnology) for 20 min at 37°C. Microscopy images

were captured using an Eclipse C1 Nikon fluorescence microscope

(magnification, ×400; Nikon Corporation).

Statistical analysis

Statistical data were analyzed using SPSS software

(version 19.0; IBM Corp.). Data are presented as the mean ±

SD. Statistical graphs were created using GraphPad Prism (version

5; GraphPad; Dotmatics). Difference comparisons between groups were

performed using an unpaired Student's t-test or one-way ANOVA

followed by Tukey's post hoc test. P<0.05 was considered to

indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

HKL alleviates IIR-induced intestinal

injury in rats

To produce an appropriate rat IIR model, the SMA was

clamped for 30, 45 or 60 min, followed by reperfusion for 2 h

according to previously described methods (41,42). The results revealed that the most

evident alterations in intestinal damage were observed in the rats

after 45 min of ischemia and 2 h of reperfusion, as demonstrated by

an increased Chiu's score (Fig.

S1). Therefore, 45 min of ischemia and 2 h of reperfusion was

used to induce IIR injury in rats for the subsequent in vivo

experiments.

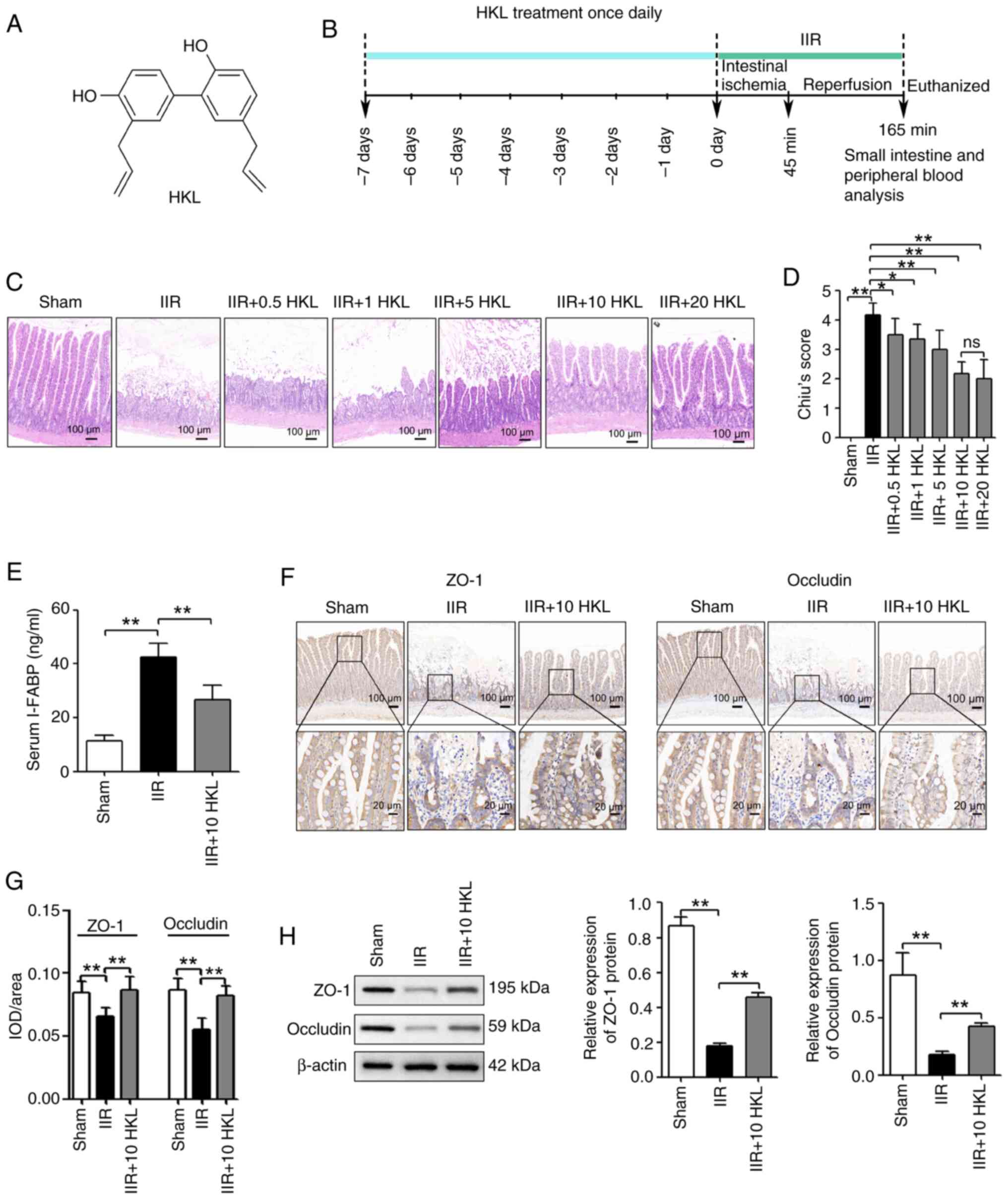

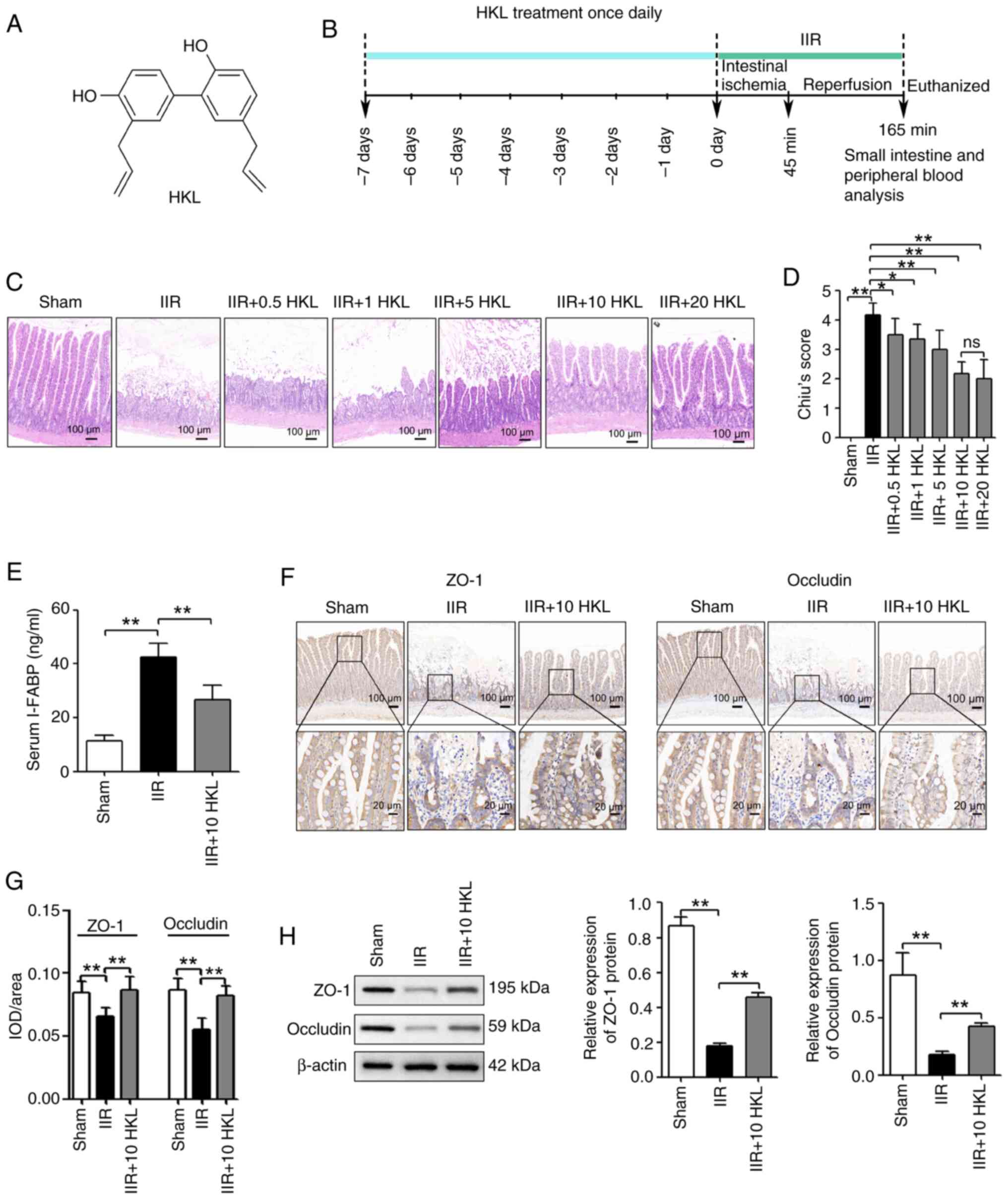

To determine the beneficial effects of HKL (Fig. 1A) treatment on IIR-induced

intestinal injury, five different doses of HKL (0.5, 1, 5, 10 or 20

mg/kg) were used once daily for 7 days prior to surgery (Fig. 1B) based on a previously published

study (50). The results

revealed that the pretreatment of rats with HKL at doses of 0.5, 1,

5, 10 or 20 mg/kg before IIR-induced injury, significantly reduced

the damage to the intestinal mucosa and reduced the Chiu's score

compared with that of the IIR-only group. In addition, the rats

that were pretreated with 10 or 20 mg/kg HKL had reduced damage to

the intestinal mucosa as well as a reduced Chiu's score compared

with those of the 0.5, 1 or 5 mg/kg HKL pretreated rats (Fig. 1C and D). However, 20 mg/kg HKL

did not have a significant effect on improving the damage in the

Chiu score compared with that of HKL at the 10 mg/kg dose (Fig. 1C and D). Therefore, the 10 mg/kg

HKL dose was used in the subsequent experiments. To further

investigate the effect of HKL on IIR-induced intestinal injury, the

concentration of serum i-FABP (a marker of tissue injury) was

determined using ELISA. As shown in Fig. 1E, IIR injury significantly

increased the concentration of serum i-FABP compared with the sham

group. However, in rats with IIR-induced injury, HKL pretreatment

significantly reduced the concentration of serum i-FABP compared

with those without HKL pretreatment. In addition, the effect of HKL

pretreatment on the small intestinal barrier was determined by

analyzing occludin and ZO-1 protein expression levels using IHC

staining and western blotting. The findings revealed that

IIR-induced injury significantly reduced occludin and ZO-1 protein

levels compared with those in the sham group. Furthermore, the

reduced occludin and ZO-1 protein levels that were induced by IIR

injury were significantly reversed with HKL pretreatment (Fig. 1F-H).

| Figure 1HKL treatment reduces IIR-induced

intestinal injury in rats. (A) Chemical structure of HKL. (B)

Workflow of the in vivo experiments. (C) Hematoxylin and

eosin staining of intestinal tissues from rats after treatment with

0, 0.5, 1, 5, 10 or 20 mg/kg HKL (magnification, ×100; scale bar,

100 µm). (D) Histopathological damage was determined using

Chiu's score (n=6). (E) IIR-induced intestinal injury was measured

using the serum i-FABP levels (n=6). (F) Consecutive sectioning of

the same specimen for IHC staining was used to measure the protein

expression levels of occludin and ZO-1 in the intestinal tissues of

rats in different treatment groups (magnification, ×100 or ×400;

scale bars, 100 or 20 µm; n=6). (G) Quantification of ZO-1

and occludin expression levels after IHC staining. (H) The protein

expression levels of occludin and ZO-1 in the intestinal tissues of

rats in different treatment groups were determined using western

blotting (n=4). *P<0.05 and **P<0.01.

ns, not significant; IHC, immunohistochemical; IIR, intestinal

ischemia-reperfusion; HKL, honokiol; i-FABP, intestinal fatty

acid-binding protein; ZO-1, tight junction protein 1; IOD,

integrated optical density. |

HKL alleviates H/R-triggered pyroptosis

in IEC-6 cells

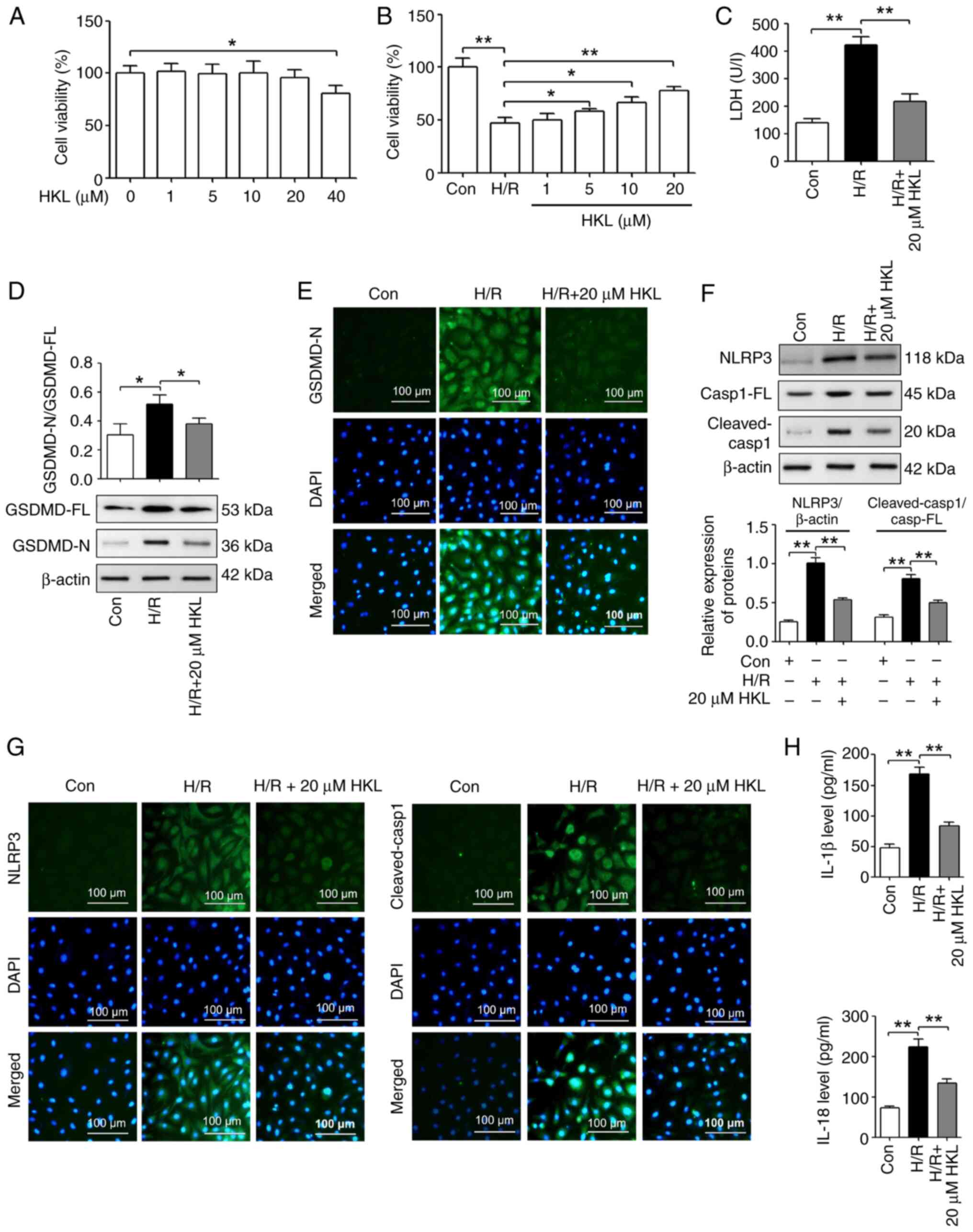

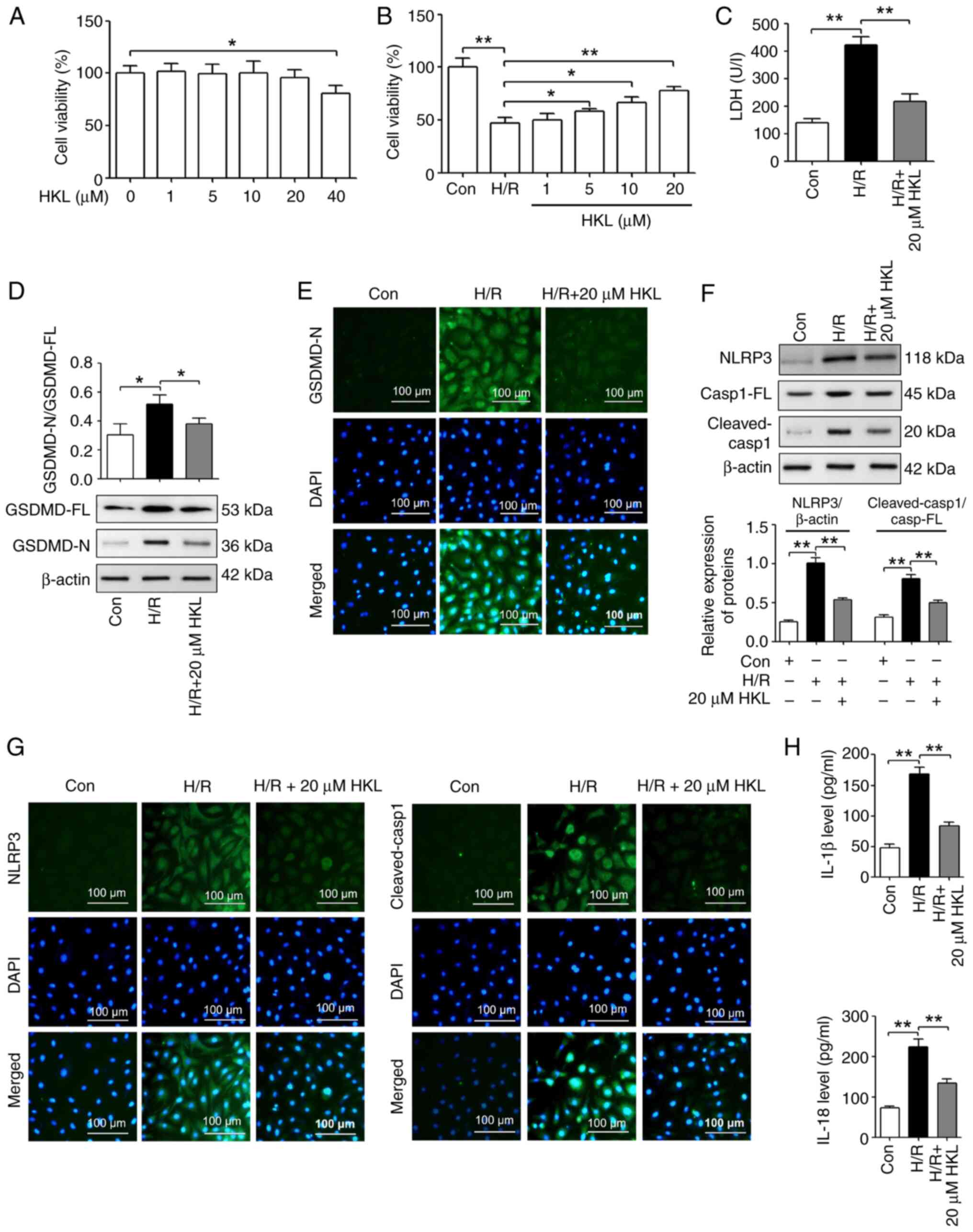

To investigate whether HKL had a beneficial role

in vitro, the cytotoxicity of HKL on IEC-6 cells at five

concentrations (1, 5, 10, 20 or 40 µM) was determined based

on a previously published study (51). As shown in Fig. 2A, 40 µM HKL significantly

reduced the viability of IEC-6 cells following treatment for 12 h.

A H/R model was then established using IEC-6 cells, and a CCK-8

assay was used to investigate the effect of HKL treatment on cell

viability. Compared with the con group, treatment with H/R

significantly reduced the viability of IEC-6 cells. However, the

viability of H/R treated IEC-6 cells was significantly increased

after the cells were pretreated with 5, 10 and 20 µM HKL

compared with those without HKL pretreatment (Fig. 2B). Therefore, 20 µM HKL

was used for the subsequent experiments.

| Figure 2HKL treatment notably inhibits

pyroptosis in IEC-6 cells following H/R. (A) HKL cytotoxicity to

IEC-6 cells was measured using a CCK-8 assay (n=3). (B) The effect

of HKL on the cell viability of H/R-treated IEC-6 cells was

revealed using a CCK-8 assay (n=3). (C) The effect of HKL on cell

injury was investigated by analyzing the LDH levels in cell

supernatants from H/R-treated IEC-6 cells (n=3). (D) Western

blotting assays were used to reveal the effect of HKL on GSDMD-FL

and GSDMD-N expression levels in IEC-6 cells following H/R (n=3).

(E) IF staining assays were used to demonstrate the effect of HKL

on GSDMD-N expression levels in IEC-6 cells following H/R

(magnification, ×200; scale bar, 100 µm; n=3). (F) Western

blotting assays were used to reveal the effects of HKL on the

protein expression levels of NLRP3, Casp1-FL and cleaved-Casp1 in

IEC-6 cells after H/R (n=3). (G) IF staining assays were used to

demonstrate the effects of HKL on the expression levels of NLRP3

and cleaved-Casp1 in IEC-6 cells after H/R (magnification, ×200;

scale bar, 100 µm; n=3). (H) ELISA assays were used to

reveal the effect of HKL on IL-1β and IL-18 protein levels in IEC-6

cells following H/R (n=3). *P<0.05 and

**P<0.01. HKL, honokiol; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase;

GSDMD, gasdermin D; GSDMD-FL, GSDMD-full length; GSDMD-N,

GSDMD-N-terminal domain; H/R, hypoxia/reoxygenation; NLRP3, NOD-,

LRR- and pyrin domain-containing protein 3; IF, immunofluorescent;

IL, interleukin; Con, control; Casp1, caspase-1; Casp1-FL,

Casp1-full length; CCK-8, Cell Counting Kit-8. |

To further investigate whether HKL protected IEC-6

cells following H/R, the LDH (an index of cell injury) levels were

analyzed. Compared with the con group, the LDH levels in the H/R

group were significantly increased. Furthermore, the LDH levels in

the IEC-6 cells treated with H/R and 20 µM HKL were

significantly reduced compared with the cells that were only

treated with H/R (Fig. 2C).

A number of studies show that pyroptosis serves an

important role in IIR-induced injury (23,24). In addition, HKL inhibits NLRP3

inflammasome-mediated pyroptosis, which reduces lipopolysaccharide

(LPS)-induced acute lung injury (50). Therefore, the present H/R model

was used to determine whether HKL affected NLRP3

inflammasome-induced pyroptosis. Western blotting revealed that the

GSDMD-N/GSDMD-full length (GSDMD-FL) ratio was increased in the H/R

group compared with the con group. Furthermore, the

GSDMD-N/GSDMD-FL ratio was significantly reduced in the 20

µM HKL pretreated H/R-induced cells compared with the

H/R-induced cells without HKL pretreatment (Fig. 2D). IF staining experiments

revealed that the protein expression of GSDMD-N was increased in

the H/R group compared with the con group. However, the protein

expression of GSDMD-N was reduced in the 20 µM HKL

pretreated H/R-induced cells compared with the H/R-induced cells

without HKL pretreatment (Fig.

2E). Additionally, the protein levels of NLRP3 and the

cleaved-Casp1/Casp1-full length (Casp1-FL) ratio were significantly

increased in the H/R group compared with those in the con group.

Furthermore, the protein levels of NLRP3 and the

cleaved-Casp1/Casp1-FL ratio were significantly decreased in the 20

µM HKL pretreated H/R-induced cells compared with the

H/R-induced cells without HKL pretreatment (Fig. 2F). IF staining experiments

indicated that the levels of NLRP3 and cleaved-Casp1 were increased

in the H/R group compared with the con group. However, the levels

of NLRP3 and cleaved-Casp1 were reduced in the 20 µM HKL

pretreated H/R-induced cells compared with the H/R-induced cells

without HKL pretreatment (Fig.

2G). Subsequently, the pyroptosis-related inflammatory

products, IL-1β and IL-18, were assessed. The results revealed that

the IL-1β and IL-18 levels in the H/R group were significantly

increased compared with those in the con group. However, the IL-1β

and IL-18 levels were significantly reduced in the 20 µM HKL

pretreated H/R-induced cells compared with the H/R-induced cells

without HKL pretreatment (Fig.

2H).

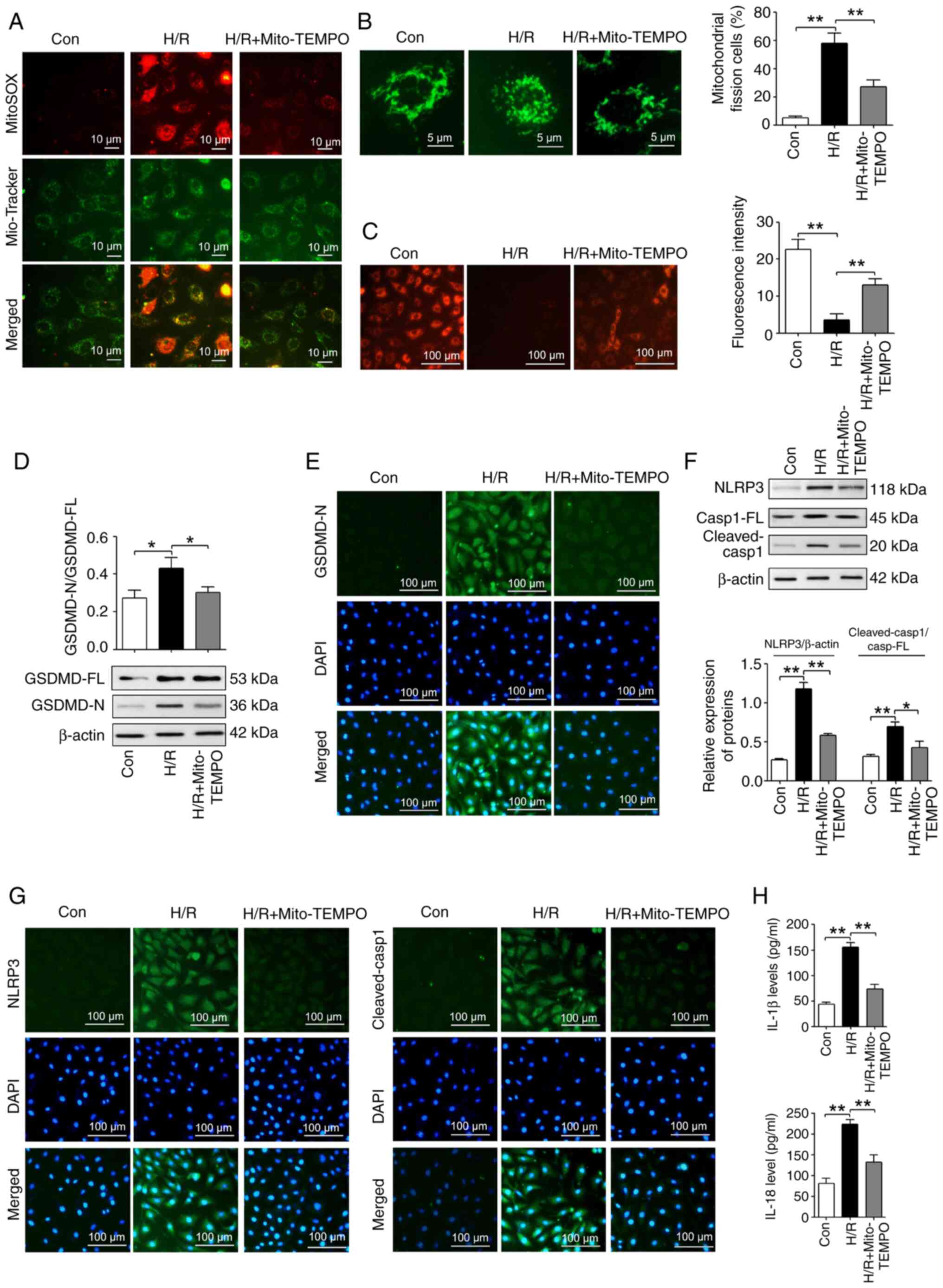

Inhibition of mitochondrial ROS

alleviates H/R-triggered pyroptosis in IEC-6 cells

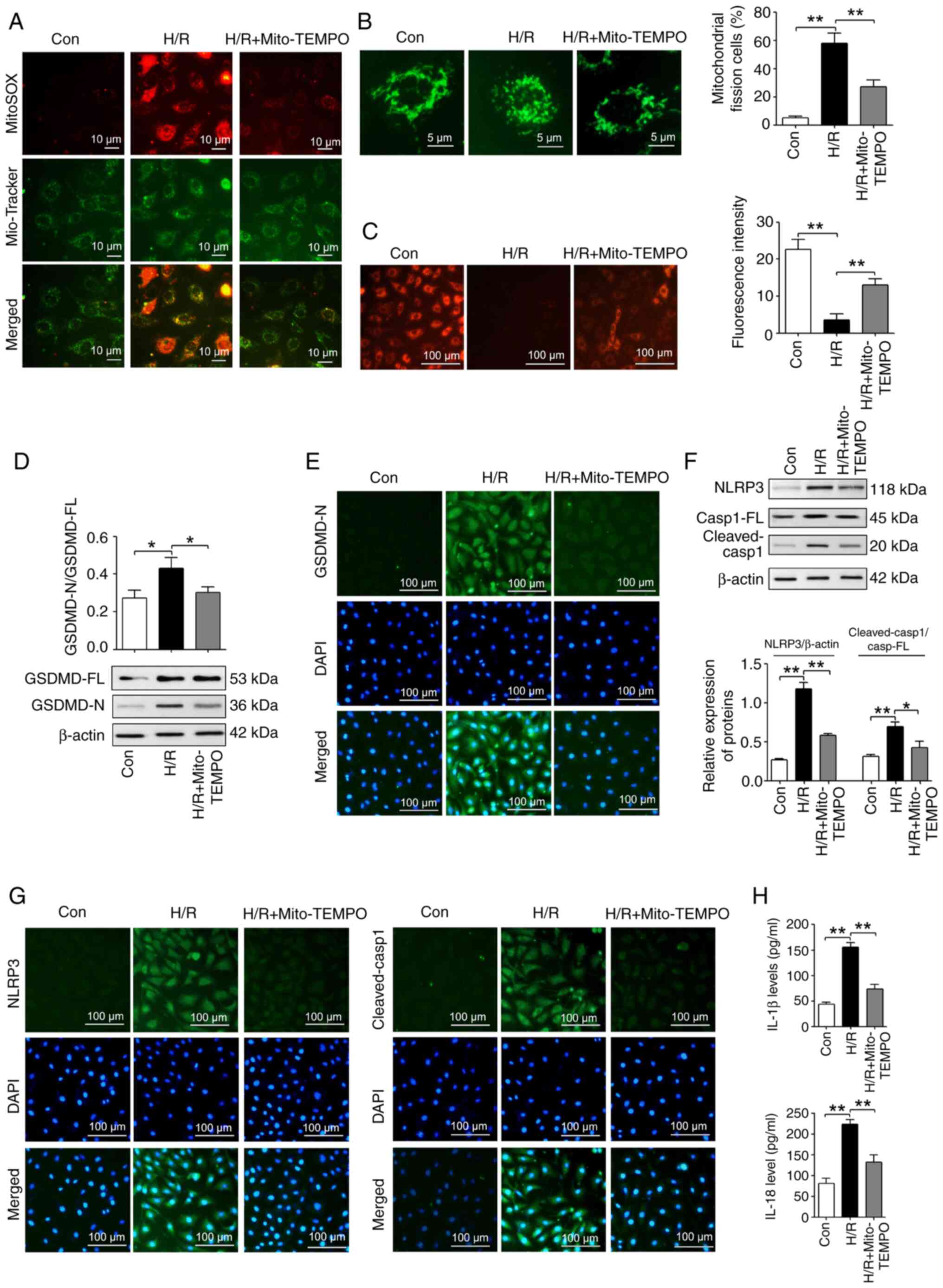

Previous studies reveal that mitochondrial

dysfunction activates pyroptosis by regulating the Δψm

and ROS production (52,53). Mitochondria are the predominant

source of ROS production. To investigate the role of mitochondrial

ROS in H/R-induced pyroptosis, mitochondrial ROS production was

inhibited by Mito-TEMPO, which is a mitochondrion-targeted

superoxide dismutase mimic that is usually used to scavenge

superoxide and alkyl radicals (54). As shown in Fig. 3A, 200 µM Mito-TEMPO

reduced the mitochondrial ROS production that was induced by H/R.

Furthermore, mitochondrial fission was significantly increased in

the H/R-induced IEC-6 cells compared with those in the con group.

However, mitochondrial fission was significantly reduced in the

Mito-TEMPO-treated H/R-induced cells compared with those without

Mito-TEMPO treatment (Fig. 3B).

In addition, H/R significantly reduced the Δψm in IEC-6 cells

compared with the con group. This was significantly reversed in

H/R-induced cells with Mito-TEMPO treatment (Fig. 3C).

| Figure 3Inhibiting mitochondrial ROS with

Mito-TEMPO reduces pyroptosis in IEC-6 cells following H/R. (A)

MitoSOX Red and Mito-Tracker Green co-staining was used to analyze

the production of mitochondrial ROS in different treatment groups

(Mito-TEMPO, 200 µM; magnification, ×400; scale bar, 10

µm). (B) Mitochondrial fission and integrity in different

treatment groups were measured using Mito-Tracker Green staining

(Mito-TEMPO, 200 µM; magnification, ×1,000; scale bar, 5

µm; n=3). (C) The mitochondrial membrane potential was

analyzed in different treatment groups using tetramethylrhodamine

ethyl ester perchlorate staining (Mito-TEMPO, 200 µM;

magnification, ×200; scale bar, 100 µm; n=3). (D) The

GSDMD-FL and GSDMD-N expression levels in different treatment

groups were measured using western blotting assays (Mito-TEMPO, 200

µM; n=3). (E) The GSDMD-N expression levels were measured in

different treatment groups using IF staining assays (Mito-TEMPO,

200 µM; magnification, ×200; scale bar, 100 µm; n=3).

(F) Western blotting assays were used to reveal the expression

levels of NLRP3, Casp1-FL and cleaved-Casp1 in different treatment

groups (Mito-TEMPO, 200 µM; n=3). (G) IF staining assays

were used to measure the expression levels of NLRP3 and

cleaved-Casp1 in different treatment groups (Mito-TEMPO, 200

µM; magnification, ×200; scale bar, 100 µm; n=3). (H)

ELISA assays were used to reveal the IL-1β and IL-18 protein levels

in different treatment groups (Mito-TEMPO, 200 µM; n=3).

*P<0.05 and**P<0.01. Con, control; H/R,

hypoxia/reoxygenation; GSDMD, gasdermin D; GSDMD-FL, GSDMD-full

length; GSDMD-N, GSDMD-N-terminal domain; NLRP3, NOD-, LRR- and

pyrin domain-containing protein 3; IF, immunofluorescent; IL,

interleukin; Casp1, caspase-1; Casp1-FL, Casp1-full length; ROS,

reactive oxygen species. |

Western blotting indicated that the GSDMD-N/GSDMD-FL

ratio was significantly increased in the H/R group compared with

the con group. However, Mito-TEMPO treatment significantly reversed

this H/R-induced change (Fig.

3D). IF staining experiments demonstrated that the protein

expression of GSDMD-N was increased in the H/R group compared with

the con group, while Mito-TEMPO treatment reversed this H/R-induced

change in the GSDMD-N levels (Fig.

3E). Additionally, western blotting assays revealed that

Mito-TEMPO treatment significantly reversed the H/R-induced

increases in the NLRP3 protein levels and cleaved-Casp-1/Casp-1-FL

ratio (Fig. 3F). Furthermore, IF

staining indicated that Mito-TEMPO treatment reversed the

H/R-induced increases in NLRP3 and cleaved-Casp-1 protein levels

(Fig. 3G). In addition,

Mito-TEMPO treatment reversed the H/R-induced increases in the

IL-1β and IL-18 protein levels (Fig.

3H).

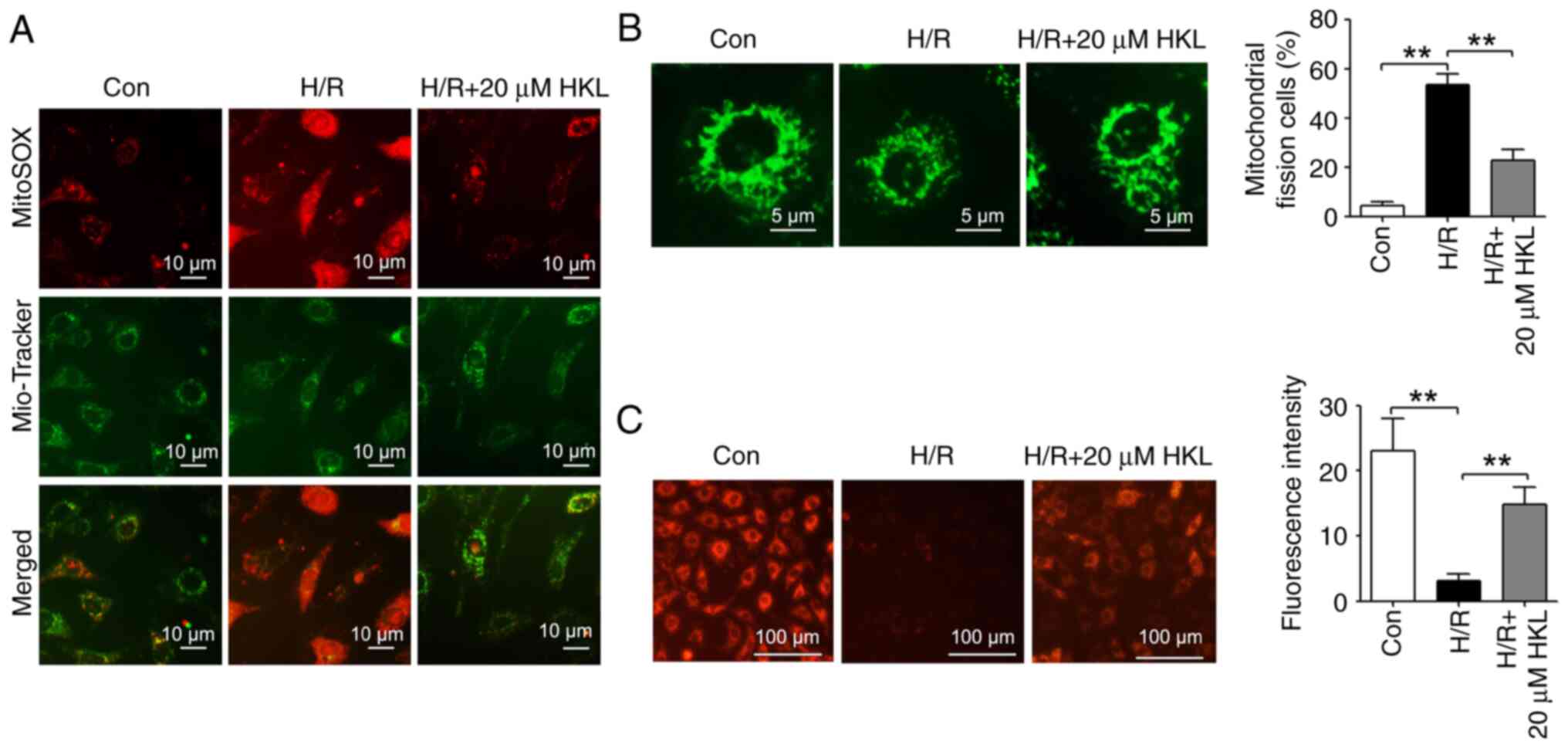

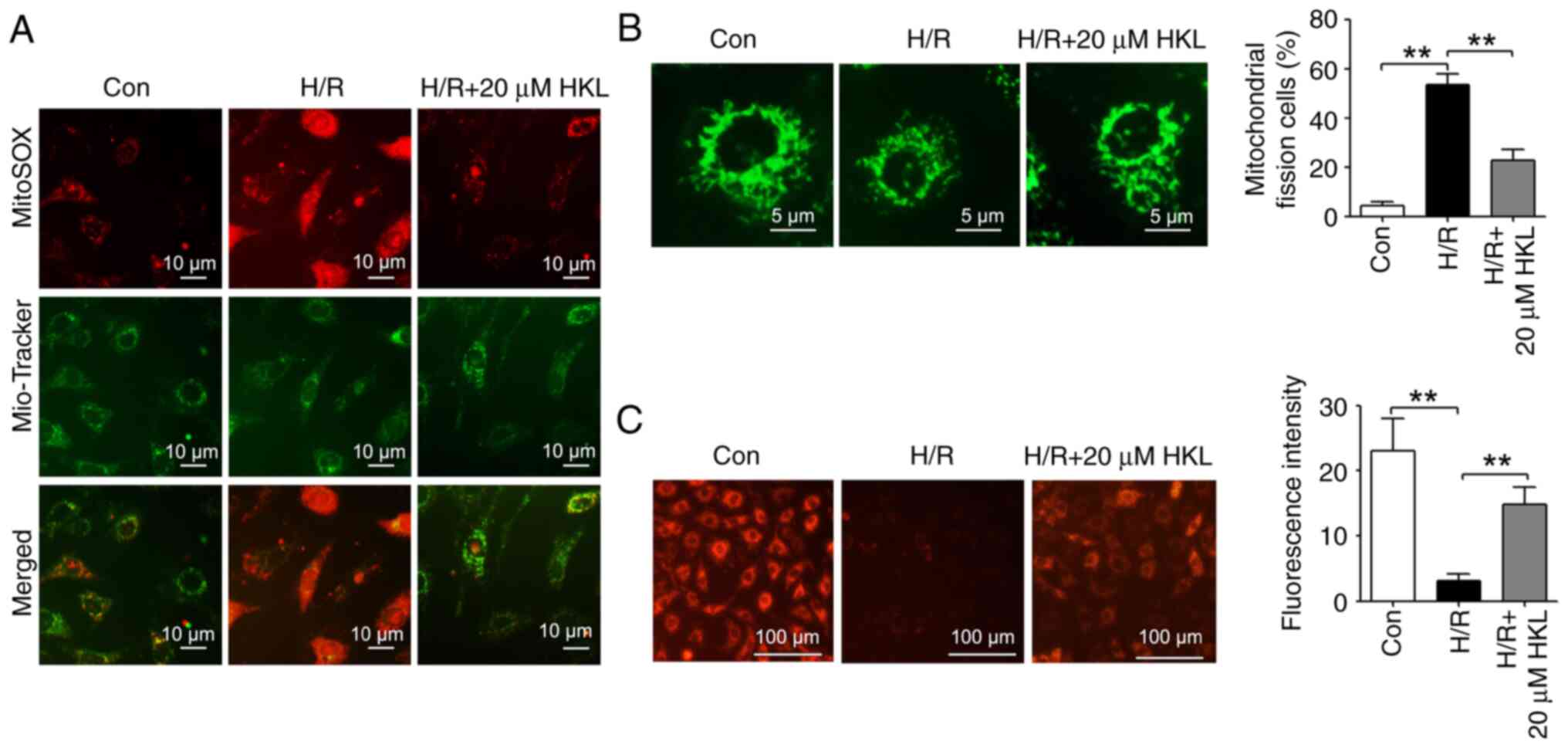

HKL alleviates the H/R-induced

mitochondrial dysfunction in IEC-6 cells

A previous study indicates that HKL alleviates

amyotrophic lateral sclerosis by improving mitochondrial function

and morphology (37). Therefore,

the effect of HKL on mitochondrial dysfunction in the H/R model was

investigated. MitoSOX Red and Mito-Tracker Green co-staining was

carried out to evaluate the production of mitochondrial ROS. As

shown in Fig. 4A, mitochondrial

ROS generation was increased in H/R-induced IEC-6 cells compared

with those in the con group. However, 20 µM HKL treatment

reversed this H/R-induced increase in the ROS accumulation in the

mitochondria. Mito-Tracker Green staining revealed that the

mitochondrial fission was significantly increased in the

H/R-treated IEC-6 cells compared with those in the con group, and

20 µM HKL treatment significantly reversed the H/R-induced

increases in the mitochondrial fission and integrity (Fig. 4B). In addition, the H/R-induced

reduction in the Δψm was significantly reversed with 20

µM HKL treatment (Fig.

4C).

| Figure 4HKL reduces mitochondrial dysfunction

in IEC-6 cells following H/R. (A) MitoSOX Red and Mito-Tracker

Green co-staining was used to investigate the effect of HKL on the

generation of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species in IEC-6 cells

following H/R (magnification, ×400; scale bar, 10 µm). (B)

The effects of HKL on mitochondrial fission and integrity were

demonstrated using Mito-Tracker Green staining in IEC-6 cells after

H/R (magnification, ×1,000; scale bar, 5 µm; n=3). (C) The

mitochondrial membrane potential was analyzed in different

treatment groups using tetramethylrhodamine ethyl ester perchlorate

staining (magnification, ×200; scale bar, 100 µm; n=3).

**P<0.01. Con, control; H/R, hypoxia/reoxygenation;

HKL, honokiol. |

HKL alleviates H/R-induced mitochondrial

dysfunction by inducing the expression of SIRT3 protein in IEC-6

cells

SIRT3 is a mitochondrial protein that is involved in

regulating mitochondrial function (55). In intracerebral hemorrhage, HKL

protects mitochondrial function by increasing the expression of

SIRT3 protein (40). Therefore,

the effects of HKL treatment on SIRT3 in the present H/R cell model

was investigated. SIRT3 levels were revealed to be significantly

reduced in the H/R-induced cells compared with the con group.

However, 20 µM HKL treatment significantly reversed the

H/R-induced reduction in the SIRT3 levels (Fig. 5A). A previous study demonstrates

that HKL also increases the mRNA expression of SIRT3 during cardiac

hypertrophy (38). In the

present study, 20 µM HKL treatment also increased the SIRT3

mRNA levels in IEC-6 cells after H/R inhibition (Fig. S2).

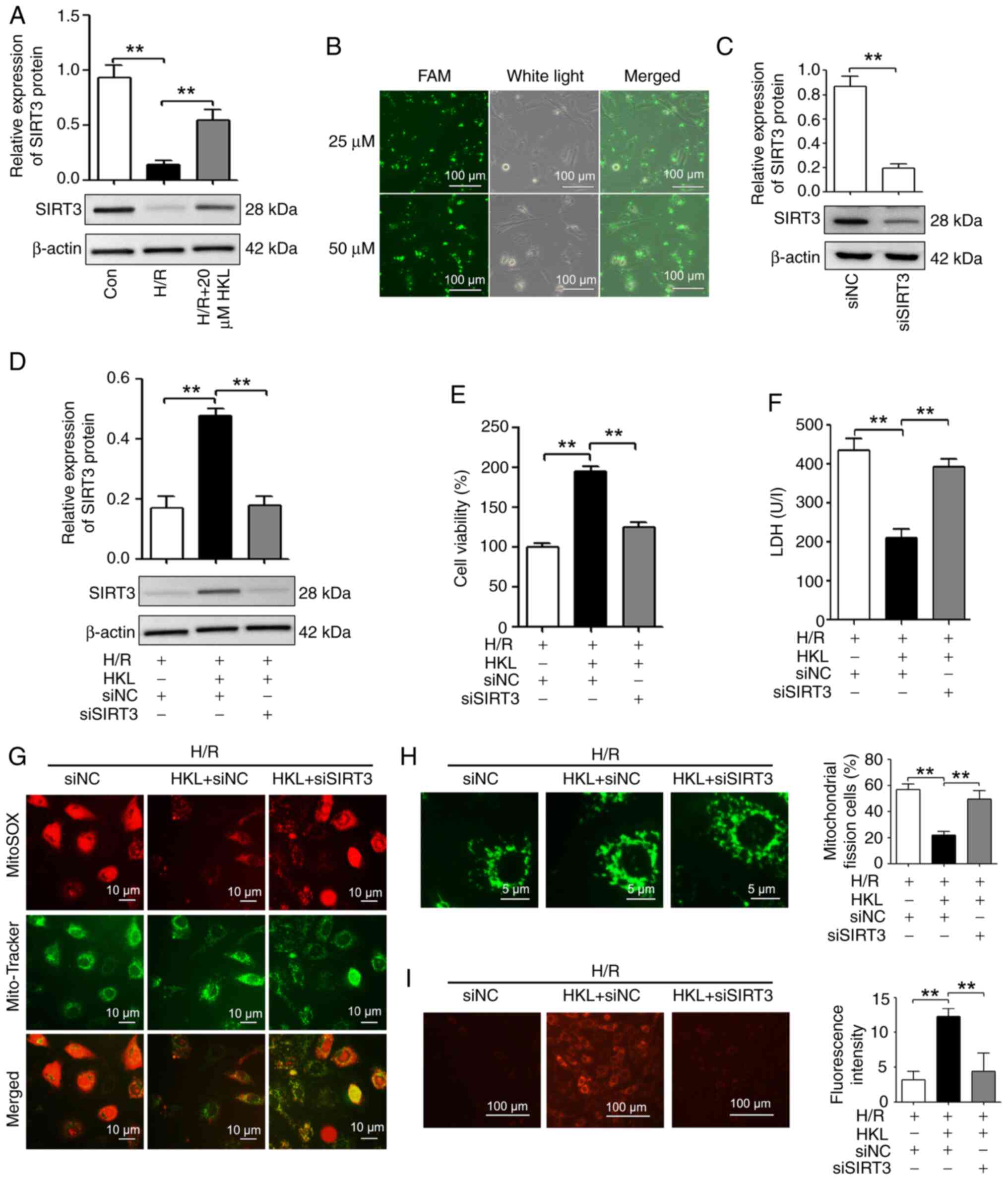

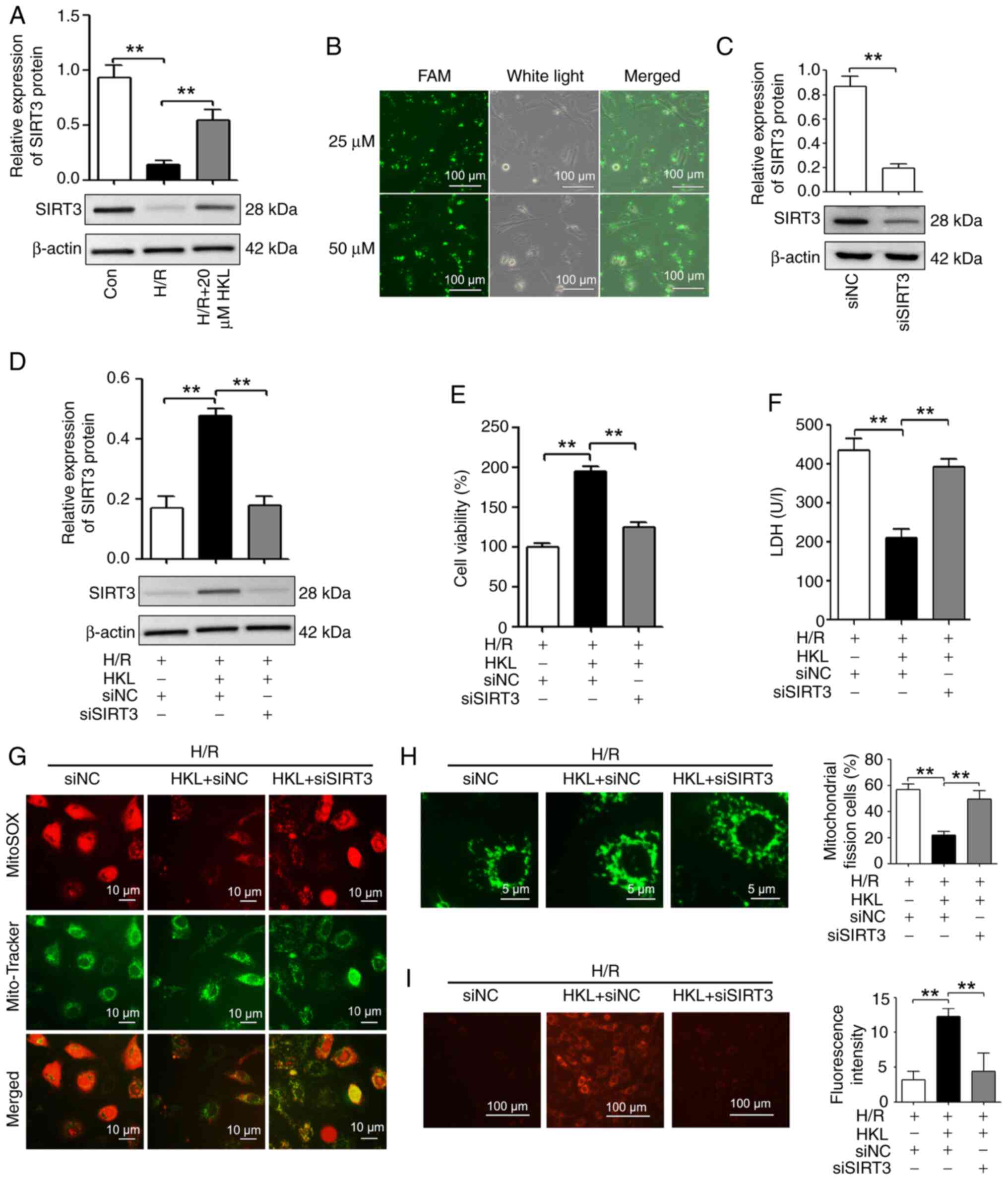

| Figure 5HKL (20 µM) reduces

mitochondrial dysfunction by inducing SIRT3 in IEC-6 cells

following H/R. (A) Western blotting was used to measure the SIRT3

expression levels in different treatment groups (n=3). (B) The

transfection efficiency of siRNAs was demonstrated using

FAM-labeled siNC (magnification, ×200; scale bar, 100 µm).

(C) The knockdown efficiency of siSIRT3 was revealed using western

blotting (n=3). (D) Western blotting was used to demonstrate the

effect of siSIRT3 on the SIRT3 levels in IEC-6 cells after exposure

to H/R and HKL (n=3). (E) The cell viability of IEC-6 cells after

different treatments was measured using a Cell Counting Kit-8 assay

(n=3). (F) The cell injury of IEC-6 cells after different

treatments was investigated by analyzing the LDH levels (n=3). (G)

The generation of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species was

revealed using MitoSOX Red and Mito-Tracker Green co-staining in

IEC-6 cells after different treatments (magnification, ×400; scale

bar, 10 µm). (H) Mitochondrial fission and integrity were

revealed using Mito-Tracker Green staining in H/R-induced IEC-6

cells following HKL and siSIRT3 treatment (magnification, ×1,000;

scale bar, 5 µm; n=3). (I) The mitochondrial membrane

potential was analyzed in different treatment groups using

tetramethylrhodamine ethyl ester perchlorate staining

(magnification, ×200; scale bar, 100 µm; n=3).

**P<0.01. Con, control; H/R, hypoxia/reoxygenation;

SIRT3, sirtuin 3; FAM, fluorescein amidite; LDH, lactate

dehydrogenase; si, small interfering RNA; NC, negative control;

HKL, honokiol. |

To determine whether siRNAs were transfected into

IEC-6 cells, fluorescein amidite (FAM)-labeled siNC at doses of 25

and 50 µM was examined. As shown in Fig. 5B, cells were fluorescent after

transfection with 25 and 50 µM FAM-labeled siNC, which

indicated that transfection efficiency was >90%. As the

transfection efficiency was comparable using 25 or 50 µM

FAM-labeled siNC, siRNAs at doses of 25 µM were used for

subsequent transfections. The knockdown efficiency of the SIRT3

siRNA was then examined. The results revealed that the expression

of SIRT3 was significantly reduced in the siSIRT3 group compared

with the siNC group (Fig.

5C).

To determine whether HKL affected mitochondrial

function after H/R via SIRT3 in IEC-6 cells, SIRT3 levels were

reduced using a SIRT3 specific siRNA (Fig. 5D). SIRT3 inhibition significantly

reversed the HKL-induced differences in cell viability and LDH

levels in the H/R model (Fig. 5E and

F). Furthermore, the results demonstrated that HKL was unable

to suppress the H/R-induced overproduction of mitochondrial ROS

when SIRT3 was silenced in IEC-6 cells (Fig. 5G). Additionally, HKL treatment

did not alleviate the H/R-induced mitochondrial fission in IEC-6

cells following SIRT3 silencing (Fig. 5H). In addition, HKL treatment

reversed the H/R-induced reduction of the Δψm in IEC-6

cells; however, this HKL-induced increase in the Δψm was

reduced when SIRT3 was silenced (Fig. 5I). Therefore, these results

indicated that SIRT3 may be involved in the HKL-induced protection

against mitochondrial dysfunction in the present H/R model.

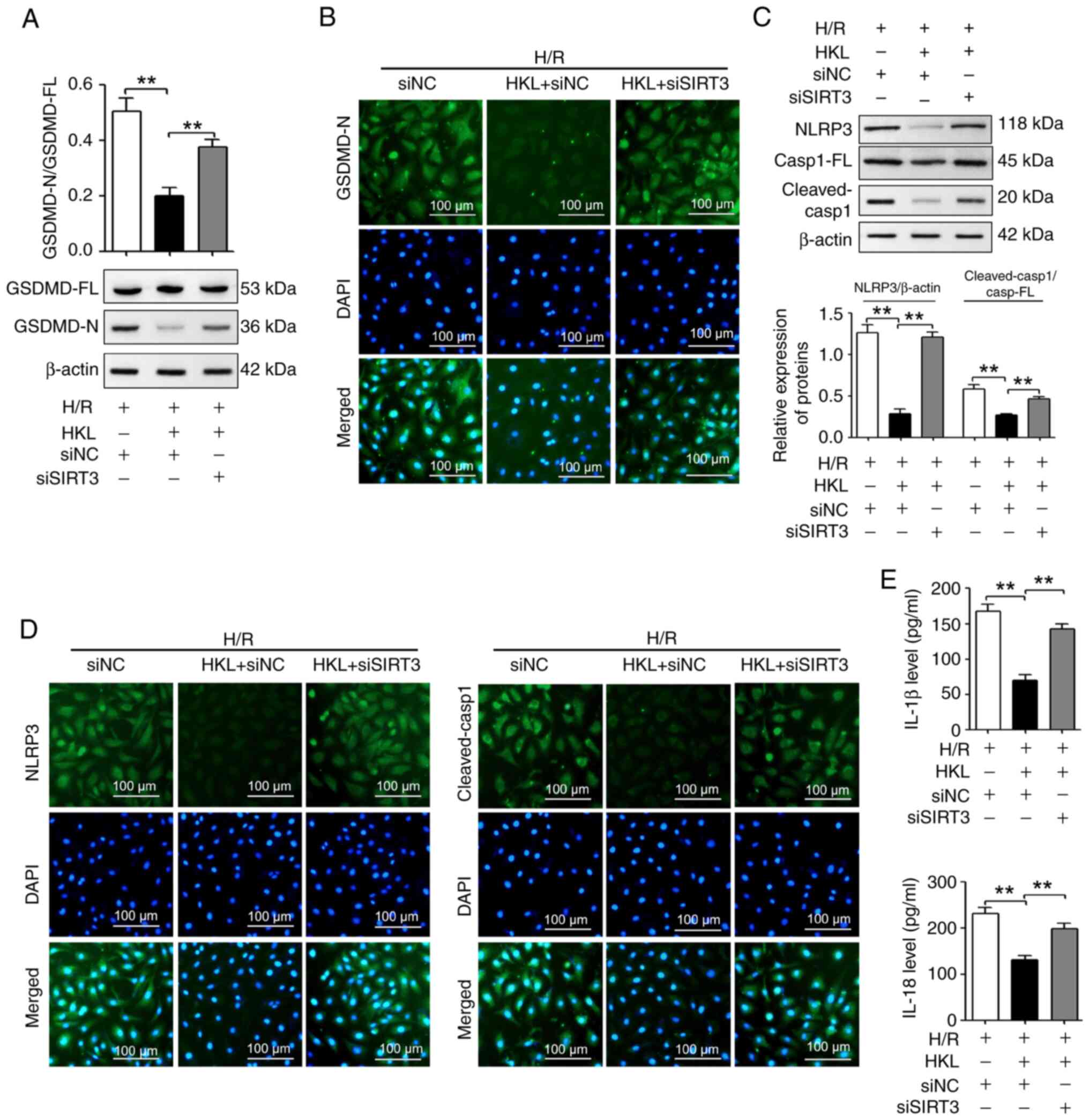

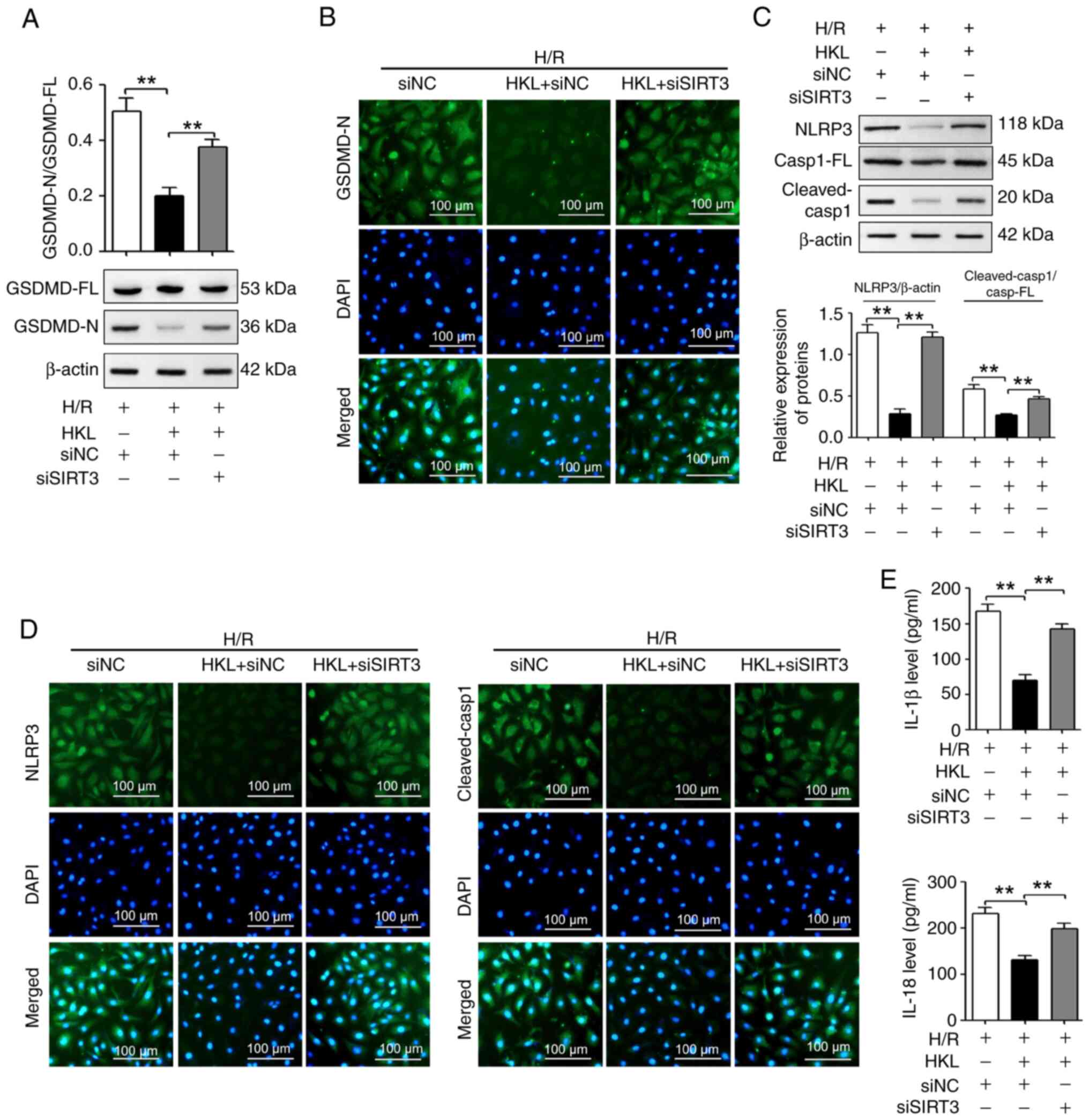

HKL alleviates pyroptosis by increasing

the expression of SIRT3 protein in H/R-induced cells

Due to the association between mitochondrial

function and pyroptosis, the potential role of SIRT3 in the

HKL-induced pyroptosis inhibition in IEC-6 cells was investigated.

Fig. 6A shows that the

HKL-induced reduction of the GSDMD-N/GSDMD-FL ratio was

significantly reversed in the present H/R model following SIRT3

silencing. IF staining experiments also demonstrated that the

HKL-induced reduction of GSDMD-N was reversed in the present H/R

model following SIRT3 silencing (Fig. 6B). Additionally, the results

revealed that the HKL-induced decrease in the NLRP3 protein levels

and the cleaved-Casp1/Casp1-FL ratio in the present H/R model was

significantly reversed following SIRT3 inhibition (Fig. 6C). IF staining experiments also

demonstrated that the HKL-induced downregulation of NLRP3 and

cleaved-Casp1 protein levels in the present H/R model were reversed

following SIRT3 inhibition (Fig.

6D). In addition, HKL treatment significantly decreased the

H/R-induced increases in the IL-1β and IL-18 levels in IEC-6 cells;

however, SIRT3 knockdown significantly reversed the effect of HKL

(Fig. 6E). Therefore, these

results suggested that SIRT3 may be involved in the HKL-mediated

pyroptosis inhibition in IEC-6 cells.

| Figure 6HKL (20 µM)reduces pyroptosis

by increasing the SIRT3 protein levels in IEC-6 cells following

H/R. (A) Western blotting revealed the GSDMD-FL and GSDMD-N protein

levels (n=3). (B) The GSDMD-N protein levels were measured using

immunofluorescent staining assays (magnification, ×200; scale bar,

100 µm; n=3). (C) NLRP3, Casp1-FL and cleaved-Casp1 protein

levels were revealed using western blotting assays (n=3). (D) NLRP3

and cleaved-Casp1 protein levels were measured using

immunofluorescent staining assays in H/R-induced IEC-6 cells with

different treatments (magnification, ×200; scale bar, 100

µm; n=3). (E) ELISA assays were used to analyze the IL-1β

and IL-18 protein levels in different treatment groups (n=3).

**P<0.01. H/R, hypoxia/reoxygenation; SIRT3, sirtuin

3; si, small interfering RNA; NC, negative control; GSDMD,

gasdermin D; GSDMD-FL, GSDMD-full length; GSDMD-N, GSDMD-N-terminal

domain; NLRP3, NOD-, LRR- and pyrin domain-containing protein 3;

IL, interleukin; Casp1, caspase-1; Casp1-FL, Casp1-full length;

HKL, honokiol. |

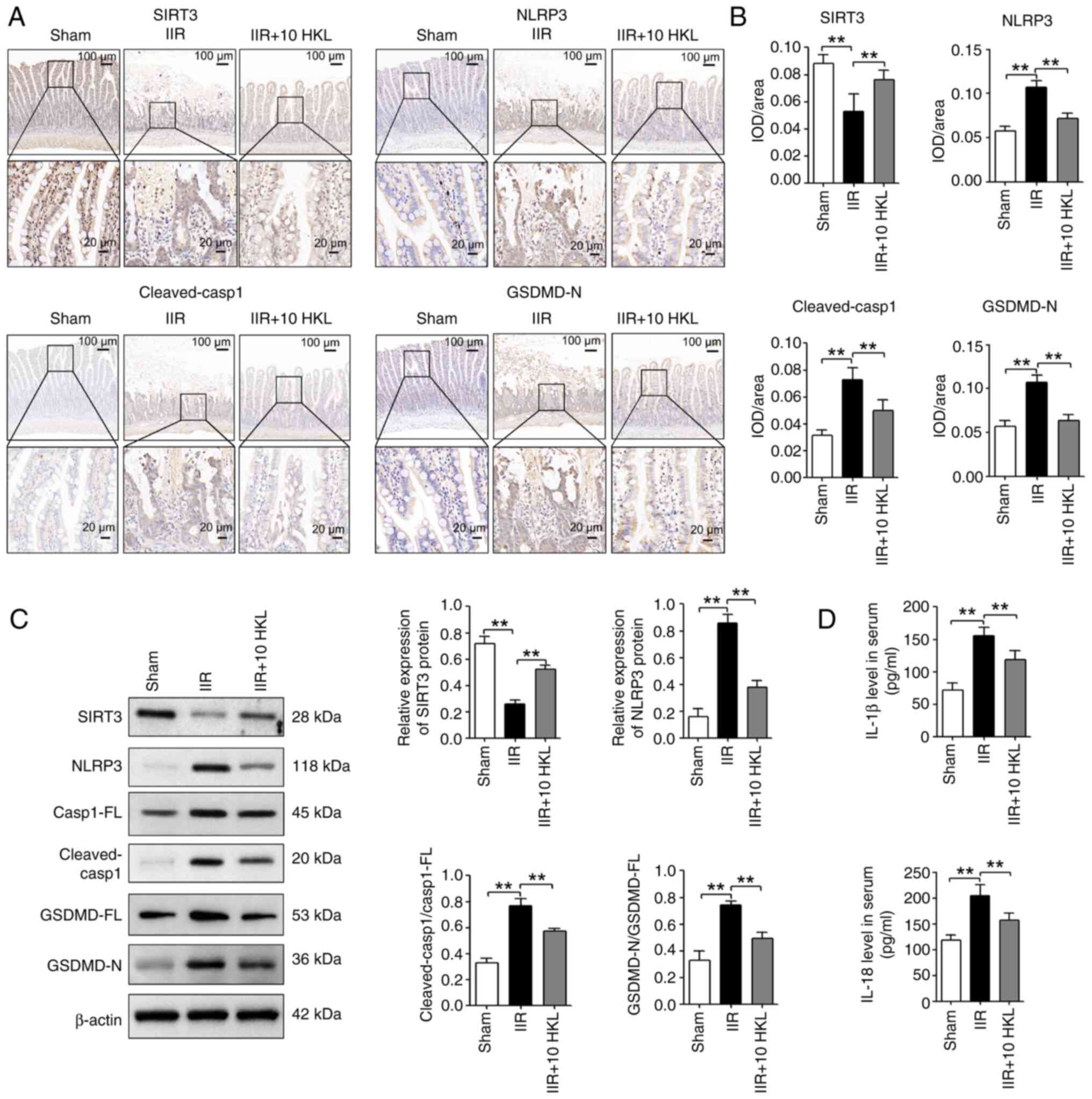

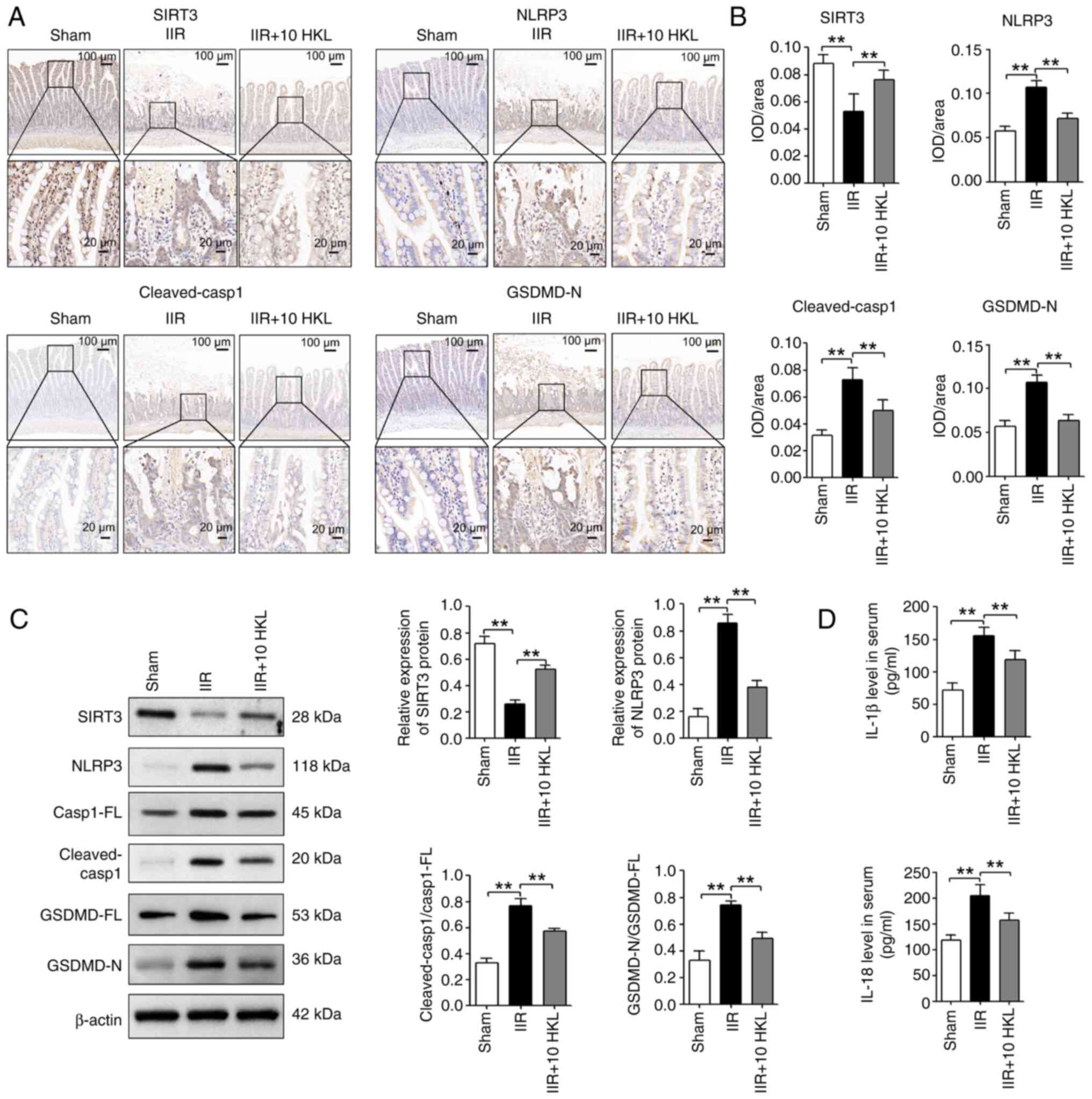

HKL alleviates IIR-induced pyroptosis by

increasing the expression of SIRT3 protein in vivo

IHC staining experiments revealed that SIRT3 was

significantly decreased in the intestinal tissues of IIR-induced

rats compared with the sham group. However, 10 mg/kg HKL treatment

significantly reversed this IIR-induced change (Fig. 7A and B). In addition, 10 mg/kg

HKL treatment significantly reversed the IIR-induced changes in

NLRP3, cleaved-Casp1 and GSDMD-N protein levels in the intestinal

tissues of rats (Fig. 7A and B).

Furthermore, western blotting assays indicated that, compared with

the sham group, IIR significantly reduced the SIRT3 protein levels

and significantly increased the NLRP3 protein levels as well as the

cleaved-Casp1/Casp1-FL and GSDMD-N/GSDMD-FL ratios in the

intestinal tissues of rats (Fig.

7C). However, 10 mg/kg HKL treatment significantly reversed

these IIR-induced changes (Fig.

7C). Compared with the sham group, IIR significantly increased

the serum IL-1β and IL-18 levels in rats; however, 10 mg/kg HKL

treatment significantly reversed these IIR-induced effects

(Fig. 7D). Taken together, these

findings suggested that HKL may inhibit pyroptosis by regulating

the expression of SIRT3 protein in IIR-induced injury.

| Figure 7HKL (10 mg/kg) reduces IIR-induced

pyroptosis by increasing the SIRT3 protein levels in rats. (A)

SIRT3, NLRP3, cleaved-Casp1 and GSDMD-N protein levels were

measured using immunohistochemical staining assays and consecutive

sectioning of the same specimen in the same area of the intestinal

tissues from different treatment groups (magnification, ×100 or

×400; scale bars, 100 or 20 µm; n=6). (B) Quantification of

SIRT3, NLRP3, cleaved-Casp1 and GSDMD-N expression levels after

immunohistochemical staining. (C) SIRT3, NLRP3, Casp1-FL,

cleaved-Casp1, GSDMD-FL and GSDMD-N protein levels were revealed

using western blotting in rats following IIR and 10 mg/kg HKL

treatment (n=4). (D) Serum IL-1β and IL-18 levels were analyzed

using ELISA assays in rats after IIR and 10 mg/kg HKL treatment

(n=6). **P<0.01. HKL, honokiol; IIR, intestinal

ischemia-reperfusion; SIRT3, sirtuin 3; GSDMD, gasdermin D;

GSDMD-FL, GSDMD-full length; GSDMD-N, GSDMD-N-terminal domain;

NLRP3, NOD-, LRR- and pyrin domain-containing protein 3; IL,

interleukin; Casp1, caspase-1; Casp1-FL, Casp1-full length; IOD,

integrated optical density. |

Discussion

Previous studies indicate that HKL possesses

protective functions against a number of ischemia-reperfusion

injuries, such as myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury, renal

ischemia-reperfusion injury and brain ischemia-reperfusion injury

(45,56,57). However, to the best of our

knowledge, the present study was the first to investigate the role

of HKL in IIR injury. In the present study, a rat IIR model was

established, and the effect of HKL on IIR-induced injury was

examined. It was revealed that, compared with IIR-induced injury

alone, HKL pretreatment notably reduced the damage to the

intestinal mucosa, the Chiu's score and the serum i-FABP

concentration, and increased the levels of intestinal barrier

proteins. To further investigate the effect of HKL on IIR-induced

injury in vitro, a H/R cell model was created to mimic

IIR-induced injury. HKL treatment ameliorated the H/R-induced

decrease in the viability of IEC-6 cells and reversed the

H/R-induced levels of LDH. Taken together, the present study

indicated the beneficial role of HKL in IIR-induced injury;

however, the detailed mechanisms need to be further

investigated.

Under normal physiological conditions, pyroptosis

serves a role in the resistance of pathogen infection (11). However, excessive pyroptosis

occurs in a number of pathological processes, such as myocardial

infarction and septicemia, and induces cell death and inflammatory

responses (10). Accumulating

evidence indicates that pyroptosis is associated with

ischemia-reperfusion injury in different organs (58). For example, during cerebral

ischemia-reperfusion injury, pyroptosis is induced in astrocytes

and promotes inflammation, and suppressing pyroptosis improves

sensorimotor function, spatial learning and memory function, and

reduces infarct volume and brain edema (59). When IIR occurs, pyroptosis is

also notably increased, whereas intestinal barrier disruption and

cell death are reduced by inhibiting pyroptosis (23). In addition, HKL improves the

aberrant interactions between tubular epithelial cells and renal

resident macrophages by inhibiting pyroptosis in lupus nephritis

(60). The results of the

present study indicated that IIR induced pyroptosis, as evidenced

by increased levels of GSDMD-N (a marker of pyroptosis). Therefore,

it was hypothesized that HKL may ameliorate IIR-induced injury by

inhibiting pyroptosis. The results of the present study revealed

that HKL treatment inhibited the H/R-induced change in the GSDMD-N

protein level. Under pathological conditions, including

ischemia-reperfusion injury, the canonical pathway of pyroptosis

involves the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome, which increases

cleaved-Casp1 production, resulting in the cleaving of pro-IL-18

and pro-IL-1β into their mature forms and the induction of

pyroptosis (58,61). The present study revealed that

H/R treatment increased the levels of NLRP3, cleaved-Casp1, IL-1β

and IL-18 in IEC-6 cells, and that this change was reversed by HKL.

Additionally, a study by Liu et al (50) reveals that HKL treatment improves

acute lung injury by suppressing NLRP3 inflammasome-induced

pyroptosis. These results indicated that HKL treatment may

ameliorate IIR injury by reversing NLRP3 inflammasome-induced

pyroptosis.

Mitochondrial damage and dysfunction are involved in

IIR-induced injury (26,27,42). During IIR, mitochondrial

dysfunction generates excessive ROS, and the increase in ROS

induces mtDNA damage, which subsequently leads to increased ROS

production and mitochondrial dysfunction, thereby inducing cell

death (26). Evidence suggests

that the overproduction of ROS by damaged mitochondria can induce

pyroptosis (62). The results of

the present study indicated that inhibiting mitochondrial ROS

reduced the H/R-induced mitochondrial fission and reduction of the

Δψm. Therefore, this indicated that mitochondrial ROS

inhibition may improve IIR-induced pyroptosis. The results of the

present study revealed that reducing mitochondrial ROS production

with Mito-TEMPO reduced pyroptosis, which was evidenced by

decreased NLRP3, cleaved-Casp1 and GSDMD-N protein levels, as well

as reduced IL-1β and IL-18 levels. Consistent with these results,

phospholipase C ε1 promotes cardiomyocyte pyroptosis by inducing

defective mitochondrial function in doxorubicin-induced

cardiotoxicity (63). To the

best of our knowledge, the present study was the first to provide

evidence that mitochondrial dysfunction may be involved in

pyroptosis during IIR-induced injury.

Since ROS production induced by mitochondrial

dysfunction can induce pyroptosis, drugs that protect mitochondrial

function may inhibit ROS-induced pyroptosis. HKL has a protective

role in a number of pathological processes by mitigating

mitochondrial dysfunction (45,64). For example, HKL exerts

cardioprotection by inhibiting mitochondrial dysfunction-induced

apoptosis in myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury (45). Therefore, it was hypothesized

that HKL may reduce ROS-induced pyroptosis by improving

mitochondrial dysfunction in IIR-induced injury. In the present

study, the results of the in vitro experiments provided

evidence to support this hypothesis. HKL treatment notably

alleviated H/R-induced mitochondrial fission, reduced mitochondrial

ROS production and reversed the reduction of the

Δψm.

Finally, the results of the present study suggested

that the SIRT3/NLRP3 pathway may be important for HKL

mediated-pyroptosis in IIR injury. SIRT3, a mitochondrial

deacetylase, is involved in regulating mitochondrial function,

cellular energy homeostasis and mitochondrial ROS production

(56,65-67). In a number of

ischemia-reperfusion injuries, including IIR injury, SIRT3

expression levels are reduced; however, increasing the SIRT3

expression levels ameliorates ischemia-reperfusion injury by

preserving mitochondrial function and reducing mitochondrial ROS

production (68-70). A recent study reveals that SIRT3

activation by Liguzinediol alleviates gasdermin E-mediated

pyroptosis by suppressing mitochondrial ROS production, which

inhibits doxorubicin-associated cardiotoxicity (71). In the progression of

atherosclerosis, melatonin inhibits NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated

macrophage pyroptosis by decreasing ROS production by activating

the SIRT3/Forkhead box O3 pathway (72). In trimethylamine-N-oxide-induced

vascular inflammation, the downregulation of SIRT3 leads to

mitochondrial ROS production by suppressing the activation of

superoxide dismutase 2, which results in NLRP3

inflammasome-mediated pyroptosis (73). Additionally, results from

molecular docking reveal that HKL can directly bind to SIRT3

protein with a low binding energy (-4.45 kcal mol−1) at

GLU371 and THR380 (74). HKL can

bind to SIRT3 and promote SIRT3 deacetylase activity by increasing

its affinity for NAD, which reduces the acetylation of

manganese-containing superoxide dismutase and reverses ROS

synthesis and cardiac hypertrophy in mice (38).

As HKL can inhibit NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated

pyroptosis by ameliorating mitochondrial dysfunction-induced

mitochondrial ROS production during IIR-induced injury, it was

hypothesized that HKL would inhibit IIR-induced pyroptosis by

regulating the SIRT3/ROS axis. In the present study, HKL treatment

notably increased the levels of SIRT3 after the H/R and IIR-induced

SIRT3 downregulation in vitro and in vivo. In

addition, knocking down SIRT3 using siRNA reduced the protective

effects of HKL on the viability and mitochondrial dysfunction of

IEC-6 cells. Knocking down SIRT3 also reversed the HKL-induced

reductions in the LDH levels and mitochondrial ROS production.

Furthermore, silencing SIRT3 in the present H/R model reversed the

HKL-induced reductions of GSDMD-N, NLRP3 and cleaved-Casp1 as well

as the reduced IL-1β and IL-18 levels. Therefore, these data

indicated that the SIRT3/NLRP3 pathway may be important for the HKL

mediated pyroptosis inhibition in IIR injury.

The findings of the present study, as well as those

of previous studies, indicated that the SIRT3 protein levels were

increased following HKL treatment (40,75,76). In addition, a previous study

revealed that treatment with HKL also increased the mRNA expression

of SIRT3 during cardiac hypertrophy (38). The results of the present study

also revealed that HKL treatment increased the SIRT3 mRNA levels in

IEC-6 cells after H/R inhibition. The mechanism underlying the

HKL-induced increase to the SIRT3 mRNA levels remains unclear,

which was a limitation of the present study. Previous studies

indicate that nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2

(Nrf2)-induced SIRT3 mRNA transcription is involved in alleviating

mitochondrial dysfunction in stress conditions (77,78). In acute lung injury, HKL reverses

the LPS-induced inhibition of Nrf2, which reduces oxidative stress

and pyroptosis (47). Therefore,

these findings indicated that HKL may promote SIRT3 mRNA

transcription by regulating Nrf2. In addition, HKL maintains the

post-translational activation of SIRT3 and upregulates the SIRT3

mRNA level by activating peroxisome proliferator-activated

receptor-γ coactivator-1α in cardiac hypertrophy (38). Therefore, to further investigate

the positive feedback mechanism regulating SIRT3 mRNA

transcription, an in-depth study is required. Another limitation of

the present study is that the mechanism of the SIRT3-regulated

mitochondrial dysfunction and mitochondrial ROS production in IIR

injury also remains unclear. The underlying regulatory mechanism

should be investigated in future studies.

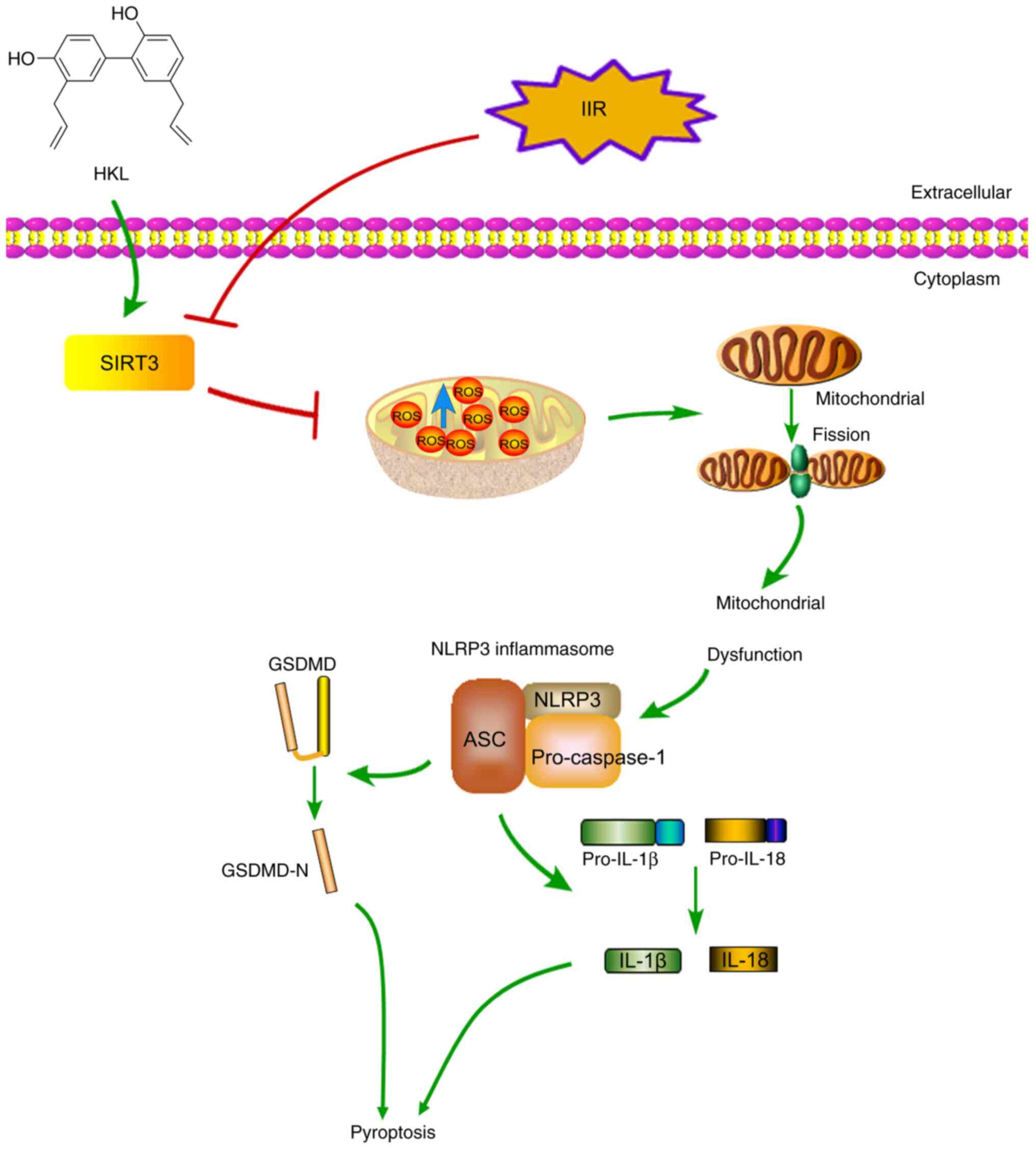

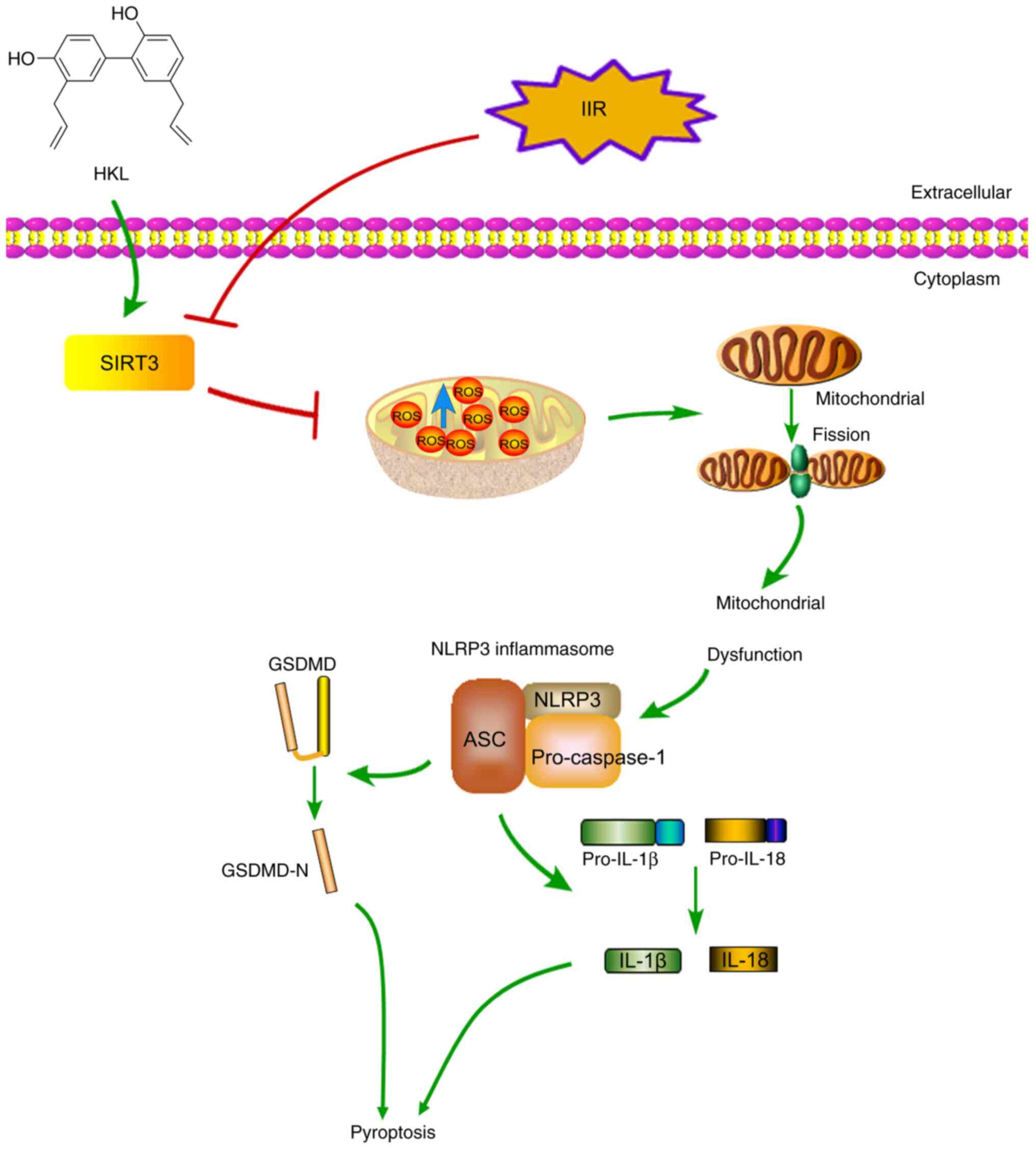

In conclusion, the present study was, to the best

of our knowledge, the first to indicate that IIR-induced

mitochondrial dysfunction triggered pyroptosis via the NLRP3 axis,

and that HKL treatment may have protective effects by upregulating

SIRT3 and alleviating mitochondrial dysfunction (Fig. 8).

| Figure 8Schematic diagram of the suggested

protective mechanism of HKL on IIR-induced injury in rats. HKL

inhibited IIR-induced pyroptosis by alleviating mitochondrial

dysfunction through the upregulation of SIRT3 protein expression

levels. HKL, honokiol; SIRT3, sirtuin 3; GSDMD, gasdermin D;

GSDMD-N, GSDMD-N-terminal domain; NLRP3, NOD-, LRR- and pyrin

domain-containing protein 3; IL, interleukin; ROS, reactive oxygen

species; ASC, apoptosis-associated speck-like protein; IIR,

intestinal ischemia-reperfusion. |

Supplementary Data

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

KW, CX and WG designed the study. KW, ZZ, QW and WG

performed the animal experiments. KW, WL, JP, LW and WG performed

the cell experiments. KW, CX, WL, JP and XM analyzed data. KW, CX

and WG wrote the first draft of the manuscript. WL, JP, ZZ, QW, CX,

LW, XM and WG revised the manuscript. KW, CX and WG confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read and approved the

final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The animal experimental protocols were approved by

the Ethics Committee of Southwest Medical University (Luzhou,

China; approval no. 20221128-001).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was supported by the Sichuan Provincial

Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine 2023 Traditional

Chinese Medicine Research Special Project (grant no. 2023MS038),

the Sichuan Provincial Administration of Traditional Chinese

Medicine 2024 Traditional Chinese Medicine Research Special Project

(grant no. 2024MS151) and the Southwest Medical University

Integrated Traditional Chinese and Western Medicine Special Project

(grant no. 2023ZYYJ07).

References

|

1

|

Jin B, Li G, Zhou L and Fan Z: Mechanism

involved in acute liver injury induced by intestinal

Ischemia-reperfusion. Front Pharmacol. 13:9246952022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Tassopoulos A, Chalkias A, Papalois A,

Iacovidou N and Xanthos T: The effect of antioxidant

supplementation on bacterial translocation after intestinal

ischemia and reperfusion. Redox Rep. 22:1–9. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Taylor LM Jr and Moneta GL: Intestinal

ischemia. Ann Vasc Surg. 5:403–406. 1991. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Slone EA and Fleming SD: Membrane lipid

interactions in intestinal ischemia/reperfusion-induced Injury.

Clin Immunol. 153:228–240. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Stamatakos M, Stefanaki C, Mastrokalos D,

Arampatzi H, Safioleas P, Chatziconstantinou C, Xiromeritis C and

Safioleas M: Mesenteric ischemia: Still a deadly puzzle for the

medical community. Tohoku J Exp Med. 216:197–204. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Li G, Wang S and Fan Z: Oxidative stress

in intestinal ischemia-reperfusion. Front Med (Lausanne).

8:7507312022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Zhang X, Wu J, Liu Q, Li X, Li S, Chen J,

Hong Z, Wu X, Zhao Y and Ren J: mtDNA-STING pathway promotes

necroptosis-dependent enterocyte injury in intestinal ischemia

reperfusion. Cell Death Dis. 11:10502020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Subramanian S, Geng H and Tan XD: Cell

death of intestinal epithelial cells in intestinal diseases. Sheng

Li Xue Bao. 72:308–324. 2020.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Li Y, Feng D, Wang Z, Zhao Y, Sun R, Tian

D, Liu D, Zhang F, Ning S, Yao J and Tian X: Ischemia-induced ACSL4

activation contributes to ferroptosis-mediated tissue injury in

intestinal ischemia/reperfusion. Cell Death Differ. 26:2284–2299.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Wei Y, Yang L, Pandeya A, Cui J, Zhang Y

and Li Z: Pyroptosis-induced inflammation and tissue damage. J Mol

Biol. 434:1673012022. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

11

|

Rao Z, Zhu Y, Yang P, Chen Z, Xia Y, Qiao

C, Liu W, Deng H, Li J, Ning P, et al: Pyroptosis in inflammatory

diseases and cancer. Theranostics. 12:4310–4329. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Ji X, Tian L, Niu S, Yao S and Qu C:

Trimethylamine N-oxide promotes demyelination in spontaneous

hypertension rats through enhancing pyroptosis of oligodendrocytes.

Front Aging Neurosci. 14:9638762022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Wang Y, Chen J, Zheng Y, Jiang J, Wang L,

Wu J, Zhang C and Luo M: Glucose metabolite methylglyoxal induces

vascular endothelial cell pyroptosis via NLRP3 inflammasome

activation and oxidative stress in vitro and in vivo. Cell Mol Life

Sci. 81:4012024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Vasudevan SO, Behl B and Rathinam VA:

Pyroptosis-induced inflammation and tissue damage. Semin Immunol.

69:1017812023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Guo Q, Wu Y, Hou Y, Liu Y, Liu T, Zhang H,

Fan C, Guan H, Li Y, Shan Z and Teng W: Cytokine secretion and

pyroptosis of thyroid follicular cells mediated by enhanced NLRP3,

NLRP1, NLRC4, and AIM2 inflammasomes are associated with autoimmune

thyroiditis. Front Immunol. 9:11972018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Karki R, Sharma BR, Tuladhar S, Williams

EP, Zalduondo L, Samir P, Zheng M, Sundaram B, Banoth B, Malireddi

RKS, et al: Synergism of TNF-α and IFN-γ triggers inflammatory cell

death, tissue damage, and mortality in SARS-CoV-2 infection and

cytokine shock syndromes. Cell. 184:149–168.e17. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Li Y, Yuan Y, Huang ZX, Chen H, Lan R,

Wang Z, Lai K, Chen H, Chen Z, Zou Z, et al: GSDME-mediated

pyroptosis promotes inflammation and fibrosis in obstructive

nephropathy. Cell Death Differ. 28:2333–2350. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Coll RC, Schroder K and Pelegrín P: NLRP3

and pyroptosis blockers for treating inflammatory diseases. Trends

Pharmacol Sci. 43:653–668. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Bai B, Yang Y, Wang Q, Li M, Tian C, Liu

Y, Aung LHH, Li PF, Yu T and Chu XM: NLRP3 inflammasome in

endothelial dysfunction. Cell Death Dis. 11:7762020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Huang Y, Xu W and Zhou R: NLRP3

inflammasome activation and cell death. Cell Mol Immunol.

18:2114–2127. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Zhang L, Ai C, Bai M, Niu J and Zhang Z:

NLRP3 Inflammasome/Pyroptosis: A key driving force in diabetic

cardiomyopathy. Int J Mol Sci. 23:106322022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Kovacs SB and Miao EA: Gasdermins:

Effectors of pyroptosis. Trends Cell Biol. 27:673–684. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Jia Y, Cui R, Wang C, Feng Y, Li Z, Tong

Y, Qu K, Liu C and Zhang J: Metformin protects against intestinal

ischemia-reperfusion injury and cell pyroptosis via

TXNIP-NLRP3-GSDMD pathway. Redox Biol. 32:1015342020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Li W, Yang K, Li B, Wang Y, Liu J, Chen D

and Diao Y: Corilagin alleviates intestinal

ischemia/reperfusion-induced intestinal and lung injury in mice via

inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome activation and pyroptosis. Front

Pharmacol. 13:10601042022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Chen Y, Han B, Guan X, Du G, Sheng B, Tang

X, Zhang Q, Xie H, Jiang X, Tan Q, et al: Enteric fungi protect

against intestinal ischemia-reperfusion injury via inhibiting the

SAA1-GSDMD pathway. J Adv Res. 61:223–237. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Hu Q, Ren J, Li G, Wu J, Wu X, Wang G, Gu

G, Ren H, Hong Z and Li J: The mitochondrially targeted antioxidant

MitoQ protects the intestinal barrier by ameliorating mitochondrial

DNA damage via the Nrf2/ARE signaling pathway. Cell Death Dis.

9:4032018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Liao S, Luo J, Kadier T, Ding K, Chen R

and Meng Q: Mitochondrial DNA release contributes to intestinal

ischemia/reperfusion injury. Front Pharmacol. 13:8549942022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Zhang Y, Lv Y, Zhang Q, Wang X, Han Q,

Liang Y, He S, Yuan Q, Zheng J, Xu C, et al: ALDH2 attenuates

myocardial pyroptosis through breaking down Mitochondrion-NLRP3

inflammasome pathway in septic shock. Front Pharmacol.

14:11258662023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Cheon SY, Kim MY, Kim J, Kim EJ, Kam EH,

Cho I, Koo BN and Kim SY: Hyperammonemia induces microglial NLRP3

inflammasome activation via mitochondrial oxidative stress in

hepatic encephalopathy. Biomed J. 46:1005932023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Li Z, Wang B, Tian L, Zheng B, Zhao X and

Liu R: Methane-rich saline suppresses ER-mitochondria contact and

activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome by regulating the PERK

signaling pathway to ameliorate intestinal Ischemia-reperfusion

injury. Inflammation. 47:376–389. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Mao H, Zhang Y, Xiong Y, Zhu Z, Wang L and

Liu X: Mitochondria-targeted antioxidant mitoquinone maintains

mitochondrial homeostasis through the Sirt3-dependent pathway to

mitigate oxidative damage caused by renal ischemia/reperfusion.

Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2022:22135032022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Zhang Q, Liu XM, Hu Q, Liu ZR, Liu ZY,

Zhang HG, Huang YL, Chen QH, Wang WX and Zhang XK: Dexmedetomidine

inhibits mitochondria damage and apoptosis of enteric glial cells

in experimental intestinal ischemia/reperfusion injury via

SIRT3-dependent PINK1/HDAC3/p53 pathway. J Transl Med. 19:4632021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Shen X, Shi H, Chen X, Han J, Liu H, Yang

J, Shi Y and Ma J: Esculetin alleviates inflammation, oxidative

stress and apoptosis in intestinal ischemia/reperfusion injury via

targeting SIRT3/AMPK/mTOR signaling and regulating autophagy. J

Inflamm Res. 16:3655–3667. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Wang Z, Sun R, Wang G, Chen Z, Li Y, Zhao

Y, Liu D, Zhao H, Zhang F, Yao J, et al: SIRT3-mediated

deacetylation of PRDX3 alleviates mitochondrial oxidative damage

and apoptosis induced by intestinal ischemia/reperfusion injury.

Redox Biol. 28:1013432020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Chen HH, Chang PC, Chen C and Chan MH:

Protective and therapeutic activity of honokiol in reversing motor

deficits and neuronal degeneration in the mouse model of

Parkinson's disease. Pharmacol Rep. 70:668–676. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Huang K, Chen Y, Zhang R, Wu Y, Ma Y, Fang

X and Shen S: Honokiol induces apoptosis and autophagy via the

ROS/ERK1/2 signaling pathway in human osteosarcoma cells in vitro

and in vivo. Cell Death Dis. 9:1572018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Zhou Y, Tang J, Lan J, Zhang Y, Wang H,

Chen Q, Kang Y, Sun Y, Feng X, Wu L, et al: Honokiol alleviated

neurodegeneration by reducing oxidative stress and improving

mitochondrial function in mutant SOD1 cellular and mouse models of

amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Acta Pharm Sin B. 13:577–597. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Pillai VB, Samant S, Sundaresan NR,

Raghuraman H, Kim G, Bonner MY, Arbiser JL, Walker DI, Jones DP,

Gius D and Gupta MP: Honokiol blocks and reverses cardiac

hypertrophy in mice by activating mitochondrial Sirt3. Nat Commun.

6:66562015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Zhang Y, Wen P, Luo J, Ding H, Cao H, He

W, Zen K, Zhou Y, Yang J and Jiang L: Sirtuin 3 regulates

mitochondrial protein acetylation and metabolism in tubular

epithelial cells during renal fibrosis. Cell Death Dis. 12:8472021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Mao RW, He SP, Lan JG and Zhu WZ: Honokiol

ameliorates cisplatin-induced acute kidney injury via inhibition of

mitochondrial fission. Br J Pharmacol. 179:3886–3904. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Gao Y, Chen H, Cang X, Chen H, Di Y, Qi J,

Cai H, Luo K and Jin S: Transplanted hair follicle mesenchymal stem

cells alleviated small intestinal ischemia-reperfusion injury via

intrinsic and paracrine mechanisms in a rat model. Front Cell Dev

Biol. 10:10165972022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Almoiliqy M, Wen J, Xu B, Sun YC, Lian MQ,

Li YL, Qaed E, Al-Azab M, Chen DP, Shopit A, et al: Cinnamaldehyde

protects against rat intestinal ischemia/reperfusion injuries by

synergistic inhibition of NF-κB and p53. Acta Pharmacol Sin.

41:1208–1222. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Zhang B, Zhai M, Li B, Liu Z, Li K, Jiang

L, Zhang M, Yi W, Yang J, Yi D, et al: Honokiol ameliorates

myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury in type 1 diabetic rats by

reducing oxidative stress and apoptosis through activating the

SIRT1-Nrf2 signaling pathway. Oxid Med Cell Longev.

2018:31598012018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Zheng J, Shi L, Liang F, Xu W, Li T, Gao

L, Sun Z, Yu J and Zhang J: Sirt3 ameliorates oxidative stress and

mitochondrial dysfunction after intracerebral hemorrhage in

diabetic rats. Front Neurosci. 12:4142018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Lv L, Kong Q, Li Z and Zhang Y, Chen B, Lv

L and Zhang Y: Honokiol provides cardioprotection from myocardial

ischemia/reperfusion injury (MI/RI) by inhibiting mitochondrial

apoptosis via the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. Cardiovasc Ther.

2022:10016922022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Cong R, Sun L, Yang J, Cui H, Ji X, Zhu J,

Gu JH and He B: Protein O-GlcNAcylation alleviates small intestinal

injury induced by ischemia-reperfusion and oxygen-glucose

deprivation. Biomed Pharmacother. 138:1114772021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Han X, Yao W, Liu Z, Li H, Zhang ZJ, Hei Z

and Xia Z: Lipoxin A4 preconditioning attenuates intestinal

ischemia reperfusion injury through keap1/Nrf2 pathway in a lipoxin

A4 receptor independent manner. Oxid Med Cell Longev.

2016:93036062016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Li Y, Xu B, Xu M, Chen D, Xiong Y, Lian M,

Sun Y, Tang Z, Wang L, Jiang C and Lin Y: 6-Gingerol protects

intestinal barrier from ischemia/reperfusion-induced damage via

inhibition of p38 MAPK to NF-κB signalling. Pharmacol Res.

119:137–148. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Liu Y, Zhou J, Luo Y, Li J, Shang L, Zhou

F and Yang S: Honokiol alleviates LPS-induced acute lung injury by

inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated pyroptosis via Nrf2

activation in vitro and in vivo. Chin Med. 16:1272021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Qiu L, Xu R, Wang S, Li S, Sheng H, Wu J

and Qu Y: Honokiol ameliorates endothelial dysfunction through

suppression of PTX3 expression, a key mediator of IKK/IκB/NF-κB, in

atherosclerotic cell model. Exp Mol Med. 47:e1712015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Wang Y, Shi P, Chen Q, Huang Z, Zou D,

Zhang J, Gao X and Lin Z: Mitochondrial ROS promote macrophage

pyroptosis by inducing GSDMD oxidation. J Mol Cell Biol.

11:1069–1082. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Zheng Z, Bian Y, Zhang Y, Ren G and Li G:

Metformin activates AMPK/SIRT1/NF-κB pathway and induces

mitochondrial dysfunction to drive caspase3/GSDME-mediated cancer

cell pyroptosis. Cell Cycle. 19:1089–1104. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Feng WQ, Zhang YC, Xu ZQ, Yu SY, Huo JT,

Tuersun A, Zheng MH, Zhao JK, Zong YP and Lu AG: IL-17A-mediated

mitochondrial dysfunction induces pyroptosis in colorectal cancer

cells and promotes CD8 + T-cell tumour infiltration. J Transl Med.

21:3352023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Zhang J, Xiang H, Liu J, Chen Y, He RR and

Liu B: Mitochondrial Sirtuin 3: New emerging biological function

and therapeutic target. Theranostics. 10:8315–8342. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Park EJ, Dusabimana T, Je J, Jeong K, Yun

SP, Kim HJ, Kim H and Park SW: Honokiol protects the kidney from

renal ischemia and reperfusion injury by upregulating the

glutathione biosynthetic enzymes. Biomedicines. 8:3522020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|