Introduction

Heart failure (HF) is an end-stage cardiovascular

disease, which has become a notable public health burden due to its

high morbidity and mortality rates (1,2).

Pathological cardiac hypertrophy is an early characteristic of HF,

which manifests as the enlargement of cardiomyocytes, increased

protein synthesis, reactivation of fetal genes and cardiac fibrosis

(3). Notably, there is a lack of

effective treatments for the management of pathological cardiac

hypertrophy in clinical practice (4). Investigating the molecular

mechanisms involved in the progression of cardiac hypertrophy may

provide novel therapeutic targets for treating HF.

Tripartite motif (Trim) proteins are a group of

proteins belonging to the E3 ubiquitin ligase family; these

proteins are involved in the post-translational modification of

proteins by catalyzing the binding of ubiquitin to its substrate

(5). Trim38 is a prototypical

Trim protein that is widely expressed in various cells, which

contains a RING domain, two B-box domains, a coiled-coil domain and

a PRY-SPRY domain, and can be activated by type I IFNs and viral

infection (6). Previous studies

have shown that Trim38 serves critical regulatory roles in innate

immune and inflammatory pathways, such as the Toll-like receptor

signaling pathway, GAS/STING pathway, and MDA5- and RIG-I mediated

antiviral response (7,8). Recently, it has been reported that

Trim38 can attenuate cardiac fibrosis after myocardial infarction

by suppressing TAK1 activation (9). Trim38 has also been shown to

mitigate the development of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

(NAFLD) by promoting TAB2 degradation and inhibiting the MAPK

signaling pathway (10).

However, the role of Trim38 in pathological cardiac hypertrophy has

not yet been fully elucidated.

The present study assessed the expression levels of

Trim38 in a model of pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy

and examined its role in this pathological process.

Materials and methods

Trim38 knockout (Trim38-KO) mice

Trim38-KO mice were generated using the clustered

regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)/CRISPR

associated protein 9 (Cas9) system. The guide RNA (gRNA) was

designed using an online tool (http://chopchop.cbu.uib.no/). The target site was

located ~150 base pairs downstream of the start codon ATG on exon

1; the sequence of this region (5′-GCAATGTCAGCCCAAAAACA-3′)

disrupts the entire protein domain. The Trim38-specific gRNA was

cloned into the pUC57-sgRNA vector (cat. no. 51132; Addgene, Inc.).

The Cas9 expression vector pST1374-Cas9 (cat. no. 44758; Addgene,

Inc.) and the in vitro transcribed Trim38-sgRNA were

combined. This mixture was microinjected into single-cell C57BL/6

mouse embryos using the FemtoJet 5247 microinjection system

(Eppendorf SE). The injected embryos were then transferred into

three pseudopregnant female ICR mice (weight, 29-32 g; age, 8-9

weeks; Beijing Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology Co., Ltd.).

All mice were housed in a specific pathogen-free environment where

temperature (22±2°C), humidity (50-55%) and light cycles (12-h

light/dark cycle) were strictly regulated. In addition, the mice

had ad libitum access to both food and water. After a

gestation period of 19-21 days, the F0 generation mice were born. A

total of 2 weeks postpartum, genomic DNA was extracted from tail

snips to genotype the mice using the following primers:

Trim38-check forward (F)1, 5′-TGG GCT CAG ACT TTA GCA CG-3′;

Trim38-check reverse (R)1, 5′-TCT TCC CAA TAA CAG CGC CA-3′.

Animal model of cardiac hypertrophy

The male wild-type (WT) C57BL/6 mice (age, 8 weeks;

weight, 27-30 g) used were purchased from Beijing Vital River

Laboratory Animal Technology Co., Ltd. The WT mice and Trim38-KO

mice were randomly assigned to four experimental groups, with

initial sample sizes determined to account for potential attrition

during the modeling phase. The group allocations were as follows:

WT Sham (15 mice), WT TAC (15 mice), Trim38-KO Sham (15 mice) and

Trim38-KO TAC (20 mice). Animals were excluded if they either died

during surgery or failed to meet the predefined model success

criteria. After exclusions, a total of 10 mice per group were

included in the final dataset. Both WT and Trim38-KO mice underwent

either sham surgery or TAC surgery to induce pressure overload. The

mice were bred in a specific pathogen-free grade animal laboratory.

Housing conditions included no more than three mice per cage, with

free access to water and food, a 12-h light cycle, room temperature

maintained at 22±2°C and humidity controlled at 50-55%. During the

modeling process, anesthesia was induced via intraperitoneal

injection of a 3% sodium pentobarbital solution at a dose of 50

mg/kg. Transverse aortic constriction (TAC) was adopted to induce

cardiac hypertrophy (11). After

anesthesia, a 27G needle was placed parallel to the aorta. Next, a

needle holder was utilized to pass a 7-0 suture through the aorta

and ligate it together with the needle around the aorta. Once the

ligation was complete, the needle was rapidly removed to establish

aortic stenosis. The sham group underwent thoracotomy without

aortic ligation.

Histological analysis

Upon completion of the experimental period, mouse

hearts were harvested for analysis. The 8-week-old male C57BL/6

mice were euthanized via intraperitoneal injection of pentobarbital

sodium (150 mg/kg body weight) to ensure a rapid and painless

death. To confirm irreversible cessation of vital functions, the

following criteria were monitored: i) Cessation of cardiac

activity, verified by both thoracic palpation and direct visual

inspection post-thoracotomy; ii) bilateral pupillary dilation under

bright light examination; iii) absence of nociceptive reflexes,

demonstrated by unresponsiveness to a standardized toe-pinch

stimulus. Cardiac tissues were harvested only after confirmation of

death. The heart tissues were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 24

h and subsequently dehydrated through a graded series of ethanol

prior to paraffin embedding. Specimens were sectioned at a

thickness of 5 µm, and hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)

staining was employed to assess cardiomyocyte size. For H&E

staining, heart sections were incubated in hematoxylin working

solution for 5 min followed by eosin solution for 3 min. In

addition, picro-sirius red (PSR) staining was utilized to evaluate

the extent of ventricular fibrosis. PSR staining involved applying

a 1% PSR solution to the sections and staining them in a humidified

chamber for 90 min. All procedures were conducted at room

temperature (20-25°C). H&E-stained sections were observed under

a standard light microscope, whereas PSR-stained sections were

examined under a polarized light microscope to facilitate collagen

fiber visualization. Images were captured at ×400 magnification and

data were analyzed using the imaging analysis system Image-Pro Plus

6.0 (Media Cybernetics, Inc.).

Cell culture

Following surface sterilization through immersion in

a 75% ethanol solution, 30 neonatal Sprague-Dawley rats (age, 1-3

days; SPF Biotechnology Co., Ltd.), were euthanized via

decapitation using large, sterile straight scissors. Neonatal rat

cardiomyocytes (NRCMs) were isolated from neonatal rats according

to previously established methods (12). Specifically, the hearts of

neonatal rats were excised, followed by removal of the atria while

retaining the ventricles. NRCMs were subsequently harvested after

treatment with 0.03% pancreatin and 0.04% type II collagenase. The

digestion process with pancreatin and collagenase was conducted at

37°C to maintain enzymatic activity. The initial digestion cycle

lasted for 15 min, followed by subsequent digestion cycles each

lasting 10 min; three cycles were performed until complete tissue

dissociation was achieved. Fibroblasts were eliminated using

differential adhesion. The AC16 human cardiomyocyte cell line (cat.

no. CC-Y1760) was obtained from Shanghai EK-Bioscience

Biotechnology Co., Ltd. Both NRCMs and AC16 cells were seeded into

6-well plates at a density of 2×105 cells/well and

cultured in DMEM/F12 (cat. no. 10565018) supplemented with 10%

fetal bovine serum (cat. no. 10099141C) and 100 U/ml

penicillin/streptomycin (cat. no. 15140122) (all from Gibco; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.) for 48 h under standard conditions (37°C,

5% CO2).

Recombinant vector construction

The Trim38-knockdown adenovirus was generated by

constructing a replication-deficient adenovirus vector carrying

short hairpin RNA (shRNA) targeting Trim38 (AdshTrim38), with the

AdshRNA adenovirus containing a non-specific shRNA used as the

control. The non-specific shRNA does not target any endogenous

genes, thereby eliminating the potential for non-specific gene

knockdown to interfere with experimental outcomes. Additionally, a

rat adenovirus overexpressing Flag-Trim38 (AdTrim38) and an

adenovirus containing dominant-negative TAK1 (Ad-dnTAK1) were

constructed, with an empty vector (AdVector) used as the control.

The dnTAK1 mutant effectively inhibits the normal activation of

endogenous WT TAK1. The plasmid backbone used for these constructs

was pAd-CMV (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and 293 cells

(American Type Culture Collection) were used as the packaging cell

line for adenoviral production. Cells were transfected with 10

µg adenoviral plasmid using polyethyleneimine (PEI; cat. no.

24765-100; Polysciences, Inc.) at a DNA:PEI mass ratio of 1:3. The

DNA-PEI complex was formed in serum-free medium (~22°C, 15 min) and

added to cells. After 6 h, the medium was replaced with fresh

complete medium. Cells were cultured (37°C, 5% CO2) and

observations began on day 2 post-infection at a consistent time

point. Cytopathic effect (CPE) was assessed daily using an inverted

microscope, with cell rounding, detachment and vacuolation recorded

as key markers. CPE typically appeared within 5-7 days. For primary

virus (P1) harvest, when 50-60% of cells exhibited CPE, both the

cells and supernatant were collected. The mixture was centrifuged

at 800 × g for 10 min at 4°C, after which the supernatant was

resuspended. The cell suspension was then subjected to three

freeze-thaw cycles (liquid nitrogen/37°C water bath) to release

viral particles. The primary viral stock (P1 generation) harvested

from the initial transfection of 293 cells was used to infect fresh

293 cells. Subsequent passages (P2-P4) were generated by repeating

the harvest protocol under identical CPE progression criteria (50%

cellular pathology). All viral generations were processed through

identical centrifugation and freeze-thaw cycles as described for

P1. Following three freeze-thaw cycles to lyse the cells, the

lysate was clarified by centrifugation at 800 × g for 10 min at

4°C, and the resulting supernatant was layered onto a discontinuous

CsCl gradient (1.1, 1.3 and 1.4 g/ml) and ultracentrifuged (115,700

× g, 4°C, 2 h; TH641 rotor; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The

viral band (between the 1.3 and 1.4 g/ml CsCl layers) was

collected, dialyzed (4°C, PBS + 5% glycerol), filtered (0.22

µm) and stored at −80°C.

Adenoviruses were used to infect NRCMs at a

multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 50 particles/cells for 24 h at

37°C followed by detection and identification. The shRNA sequence

targeting Trim38 was: 5′-GCA CAA AGG TCA TAC CTT ATT-3′. The

sequences used for the construction of the aforementioned

adenoviral vectors were as follows: AdshTrim38-rat-F, CCG GTA GCT

CTG TCT AAA GGTGGAACT CGA GTT CCA CCT TTA GAC AGA GCT ATT TTTG,

AdshTrim38-rat-R, AAT TCA AAA AGC ACA AAG GTC ATACCT TAT TCT CGA

GAA TAA GGT ATG ACC TTT GTGC; AdTrim38-rat-F, AGG CTA GCG ATA TCG

GAT CCA TGG GCT CAG ACT TTA GCA CAG TG, AdTrim38-rat-R, TCG TCC TTG

TAA TCA CTA GTCT TCT TTC CAT GAT TAT TTA TGG CAG GAG GGA;

Ad-dnTAK1-mouse-F, GAT GTC GCT ATT AAC CAG ATA GAA AGT G;

Ad-dnTAK1-mouse-R, CAC TTT CTA TCT GGT TAA TAG CGA CAT C.

Plasmid construction

The Trim38 gene was amplified utilizing PCR.

Subsequently, it was cloned into the GL107 vector [pSLen

ti-EF1-EGFP-P2A-Puro-CMV-MCS-3xFLAG-WPRE; OBiO Technology

(Shanghai) Corp., Ltd.] using Seamless Cloning Kit [cat. no.

SCNP-20/50; OBiO Technology (Shanghai) Corp., Ltd.]. This process

generated a Trim38 overexpression plasmid designed to induce the

stable overexpression of Trim38 in the AC16 cardiomyocyte cell

line. The forward sequencing primer (CMV-F) was 5′-CGC AAA TGG GCG

GTA GGC GTG-3′ and the reverse sequencing primer (101-R) was 5′-AGA

GAC AGC AAC CAG GAT-3′.

Transduction and transfection

NRCMs were infected with the corresponding

adenoviruses as aforementioned. AC16 cardiomyocytes were

transfected with Trim38 overexpression plasmid to overexpress

Trim38 using Fugene transfection reagent (cat. no. E2311; Promega

Corporation), whereas the control group was transfected with an

empty plasmid. Briefly, 2 µg plasmid DNA was used per well

in a 6-well plate. The complex (plasmid DNA-Fugene HD mixture) was

formulated at ~22°C and transfection was performed at 37°C. The

complex was incubated with the cells for 48 h under standard

conditions (37°C, 5% CO2) to facilitate transfection and

DNA expression. Subsequently, the medium was replaced with

serum-free DMEM/F12 for 12 h. Thereafter, phenylephrine (PE; 50

µM; cat. no. P6126; MilliporeSigma) was used to establish a

cardiomyocyte hypertrophy model at 37°C for 48 h. The control group

was treated with an equivalent volume of PBS under the same

conditions.

Immunofluorescence

NRCMs employed in the experiment were first fixed

with 3.7% formaldehyde at room temperature for 15 min and

permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 20 min. After washing with

PBS, the cells were blocked with 8% BSA (cat. no. A1933;

MilliporeSigma) at room temperature for 60 min. A primary antibody

against α-actinin (1:100; cat. no. 05-384; MilliporeSigma) was then

applied and incubated overnight at 4°C. After removing the primary

antibody, a Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated secondary antibody [donkey

anti-mouse IgG (H+L); 1:200; cat. no. A21202; Invitrogen; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.] was added and incubated in the dark at

37°C for 60 min. The cells were counterstained with SlowFade Gold

antifade reagent containing DAPI for nuclear staining, and cured at

room temperature in the dark for 24 h. Alternatively, the cell

samples were prepared as aforementioned and stained overnight at

4°C with Actin-Tracker Red (1:100; cat. no. C2205S; Beyotime

Institute of Biotechnology). The following day, the samples were

directly mounted with DAPI and observed. Fluorescence images were

acquired using a confocal laser scanning microscope (TCS SP8; Leica

Microsystems GmbH). Image-Pro Plus 6.0 software was employed to

measure the cell surface area.

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR

(RT-qPCR)

RNA was isolated from mouse heart tissue or NRCMs

using TRIzol® reagent (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) and cDNA synthesis was carried out through RT of

the RNA according to the manufacturer's protocol (cat. no.

04896866001; Roche Diagnostics). qPCR was performed to measure the

expression levels of the selected genes, utilizing a specific qPCR

kit (cat. no. 4913850001; Roche Diagnostics), with GAPDH used as an

internal control. Primer details are provided in Table SI. The thermal cycling

conditions were as follows: Pre-incubation at 95°C for 10 min;

followed by 40 cycles of amplification at 95°C for 10 sec, 60° for

30 sec, 72°C for 20 sec; melt curve at 95°C for 5 sec, 60° for 1

min, 95°C for 15 sec; and cooling at 40°C for 10 sec. Based on the

obtained crossing point values, relative quantification analysis

was conducted using the 2−ΔΔCq method (13).

Western blot analysis

Total protein was extracted from heart tissues or

cardiomyocytes using RIPA lysis buffer (100 mg SDS, 29.2 mg EDTA,

788.2 mg Tris-HCl, 200 mg sodium deoxycholate, 1 ml NP-40 and 876.6

mg NaCl dissolved in double-distilled water; pH 7.5; final volume,

100 ml). Protein concentration was determined using a BCA assay

kit. Subsequently, proteins (50 µg) were separated by

SDS-PAGE on a 10% gel and were transferred to PVDF membranes. After

blocking with 5% non-fat milk at room temperature for 1 h, the

membranes were incubated with primary antibodies at 4°C overnight.

The following day, appropriate secondary antibodies were added and

incubated for 1 h at room temperature in the dark. Immunoblots were

visualized using the Odyssey Imaging System (LI-COR Biosciences)

and the results were normalized to GAPDH levels as the internal

control. Protein expression was semi-quantified using Image Lab 5.1

software (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.). Detailed information

regarding the antibodies is provided in Table SII.

Ubiquitination assays

AC16 cells transfected with the Trim38

overexpression plasmid and empty plasmid were lysed using a lysis

buffer added at four times the volume (8 M urea, 1% protease

inhibitor, 50 µM PR-619). The cells were sonicated in a 4°C

water bath for a total duration of 3 min using a high-intensity

ultrasonic processor (Scientz) with the following parameters: 3-sec

pulses followed by a 5-sec pause; power output, 220 W; frequency

range, 20-25 kHz. The supernatant was collected and the protein

concentration was determined using a BCA kit (cat. no. P0011;

Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) according to the

manufacturer's instructions. Subsequently, the lysate was

precipitated with 20% TCA, centrifuged at 4,500 × g for 5 min at

4°C and washed with acetone. After air-drying, TEAB (200 µM)

was added to the precipitate and dispersed by ultrasound. Trypsin

was added at a ratio of 1:50 (enzyme to protein, w/w) and the

mixture was digested overnight. The next day, trypsin was added at

a ratio of 1:100 for a second digestion lasting 4 h. The solution

was reduced with dithiothreitol (5 mM) and alkylated with

iodoacetamide (11 mM) in the dark. To enrich the modified peptides,

the peptides dissolved in NETN buffer (100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 50

mM Tris-HCl, 0.5% NP-40, pH 8.0). Each sample was incubated with 40

µl pre-washed anti-diglycyl-lysine antibody conjugated

agarose beads (cat. no. PTM1104; PTM Biolabs Inc.) at 4°C

overnight. Subsequently, the beads were washed four times with

immunoprecipitation buffer solution (PTM Biolabs Inc.) and twice

with deionized water. Bound peptides were subsequently eluted

through two consecutive washes with 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (100

µl per wash; pH ~2) while subjected to vigorous vortexing.

The eluates were then combined and vacuum-dried. The resulting

peptides were desalted with C18 ZipTips (MilliporeSigma).

Liquid chromatography-tandem mass

spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) analysis

The peptides were dissolved in solvent A (0.1%

formic acid and 2% acetonitrile in water) and loaded onto a

homemade reversed-phase analytical column (length, 25 cm; internal

diameter, 100 µm). The mobile phase consisted of solvent A

and solvent B (0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile). Peptides were

separated using following gradient; 0-40 min, 6-22% solvent B;

40-52 min, 22-30% B; 52-56 min, 30-80% solvent B; 56-60 min, 80%

solvent B. All procedures were conducted at a constant flow rate of

450 nl/min on a NanoElute UHPLC system (Bruker Daltonics; Bruker

Corporation).

Subsequently, the peptides were electrosprayed

through a capillary source, generating charged droplets that

underwent desolvation via solvent evaporation to yield gaseous

ions. These ions were then analyzed in the timsTOF Pro2 mass

spectrometry (Bruker Daltonics; Bruker Corporation). The

electrospray voltage was set to 1.5 kV. Precursors and fragments

were analyzed at the TOF detector, with a MS/MS scan range from

100-1,700 m/z. The timsTOF Pro2 was operated in parallel

accumulation serial fragmentation (PASEF) mode. Precursors with

charge states 0-5 were selected for fragmentation, and 10

PASEF-MS/MS scans were acquired per cycle. The dynamic exclusion

was set to 24 sec. The resulting MS/MS data were processed using

MaxQuant search engine (v.1.6.15.0; https://www.maxquant.org/maxquant/) (14). Tandem mass spectra were searched

against the human SwissProt database (https://www.uniprot.org/) (15) concatenated with reverse decoy and

contaminants database. Trypsin/P was specified as cleavage enzyme

allowing up to 4 missing cleavages. Minimum peptide length was set

at 7 and maximum number of modifications per peptide was set at 5.

The mass tolerance for precursor ions was set at 20 ppm in the

first search and 20 ppm in the main search, and the mass tolerance

for fragment ions was set at 20 ppm. Due to sample pre-treatment

with reduction and alkylation, carbamidomethyl modification on

cysteine residues was set as a fixed modification; ubiquitylation

on lysine residues was specified as a variable modification to

identify ubiquitination sites. The false discovery rate of protein,

peptide and peptide-spectrum match was adjusted to <1%.

Functional enrichment-based cluster

analysis

Hierarchical clustering was conducted to classify

differentially expressed proteins in the Trim38 overexpression

group compared with the control group based on their function.

Based on their expression levels, differentially expressed proteins

were divided into four groups, namely Q1 to Q4, with Q4

representing the most significantly altered proteins. Gene Ontology

(GO) classification and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

(KEGG) pathway enrichment analyses were both conducted on each of

the Q groups. GO annotation was accomplished by analyzing the

identified proteins with eggnog-mapper software v2.0 (https://github.com/eggnogdb/eggnog-mapper) (16) and the KEGG database (https://www.genome.jp/kegg/) (17) was used to conduct KEGG pathway

enrichment analysis. The Fisher's exact test was employed to

analyze the significance of KEGG pathway enrichment of

differentially expressed proteins. P<0.05 was considered to

indicate a statistically significant difference.

Statistical analysis

All values are presented as the mean ± standard

error of the mean. Normality was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk

test. For normally distributed data, comparisons between two groups

were conducted using an unpaired two-tailed Student's t-test and

one-way ANOVA was employed to evaluate differences among multiple

groups. Post-hoc analysis was performed using Bonferroni correction

for data with equal variances and Tamhane's T2 test for data with

unequal variances. For data sets with skewed distributions,

non-parametric statistical methods were applied: The Mann-Whitney U

test for comparisons between two groups and the Kruskal-Wallis test

followed by Dunn's post-hoc test for multiple comparisons.

P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

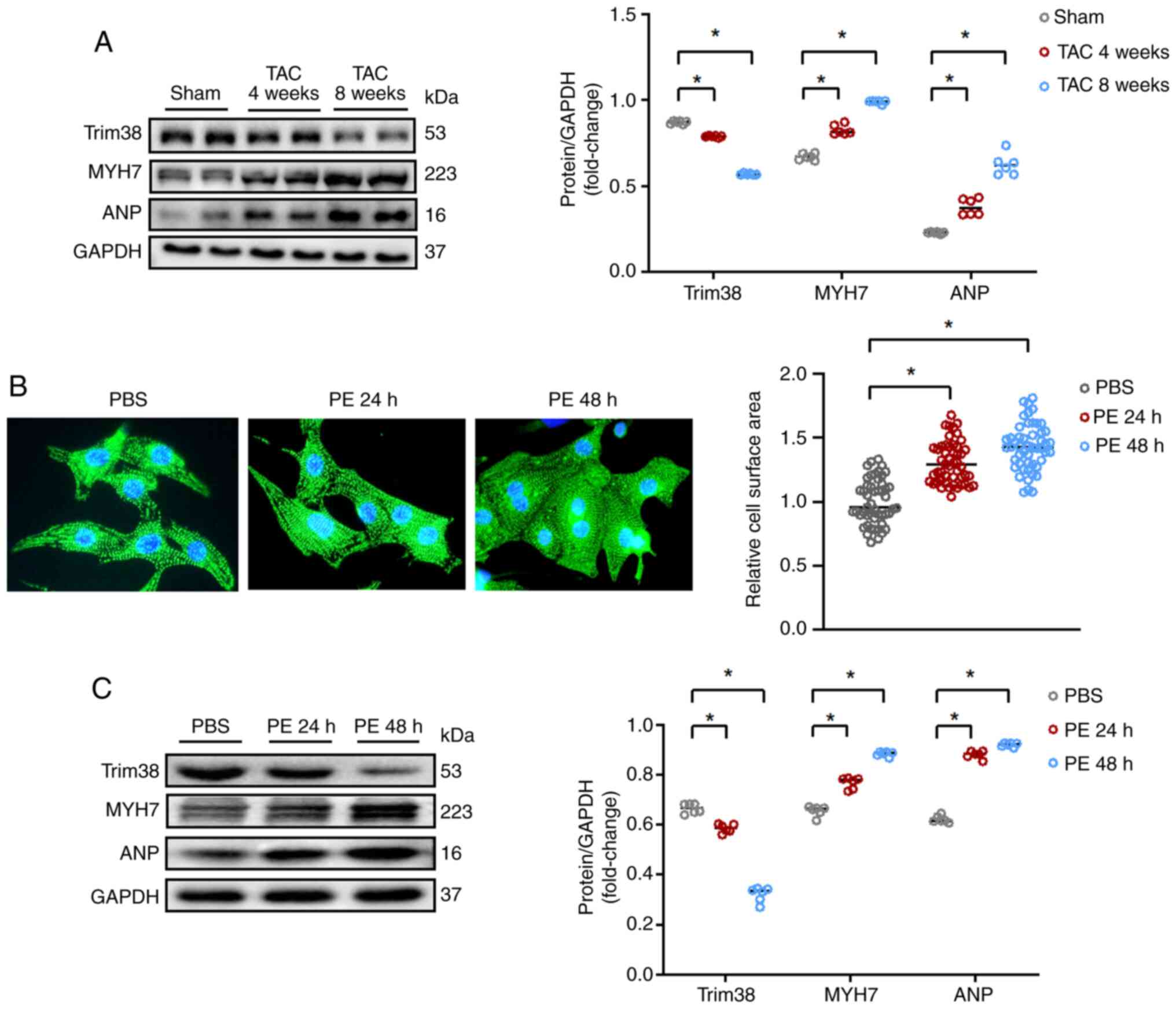

Trim38 expression is decreased in

hypertrophic myocardial tissues and cardiomyocytes

A TAC-induced mouse model of cardiac hypertrophy was

first established and the expression of Trim38 was detected using

western blotting. As shown in Fig.

1A, the expression levels of Trim38 were gradually decreased

after TAC, while the expression levels of biomarkers of cardiac

hypertrophy, such as myosin heavy chain 7 (MYH7) and atrial

natriuretic peptide (ANP), were increased. In addition, in

vitro experiments confirmed the reduced expression of Trim38 in

cardiomyocytes stimulated with PE. After 24 h of treatment with PE,

NRCMs displayed an altered morphology, indicating hypertrophy,

which was more pronounced after 48 h of PE treatment (Fig. 1B). Western blot analysis

(Fig. 1C) also demonstrated a

decrease in Trim38 expression in NRCMs treated with PE, alongside

increased levels of MYH7 and ANP, further confirming the

development of hypertrophy in the cells. Therefore, Trim38 may be

considered a potential target for cardiac hypertrophy.

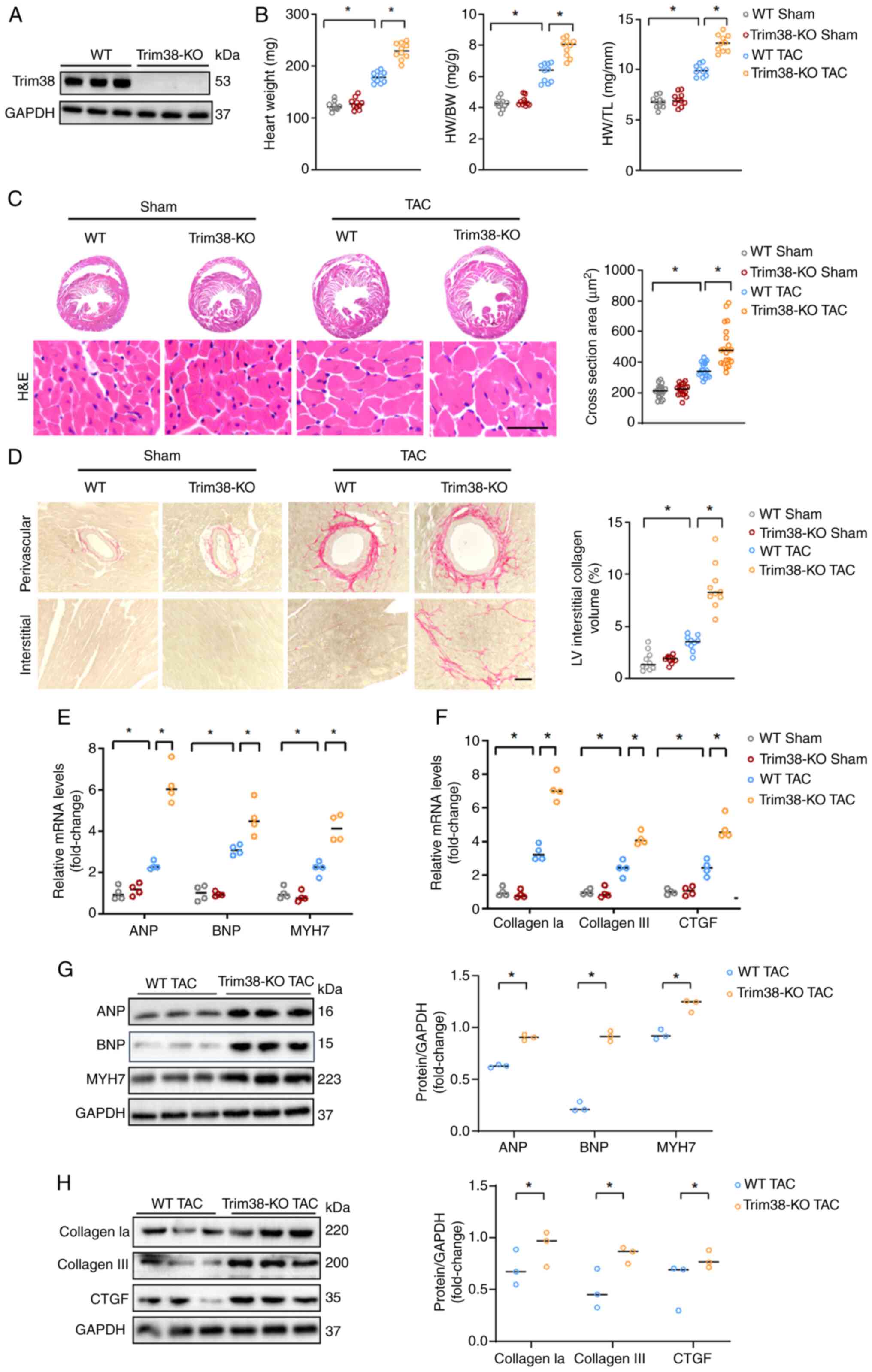

Loss of Trim38 aggravates cardiac

hypertrophy

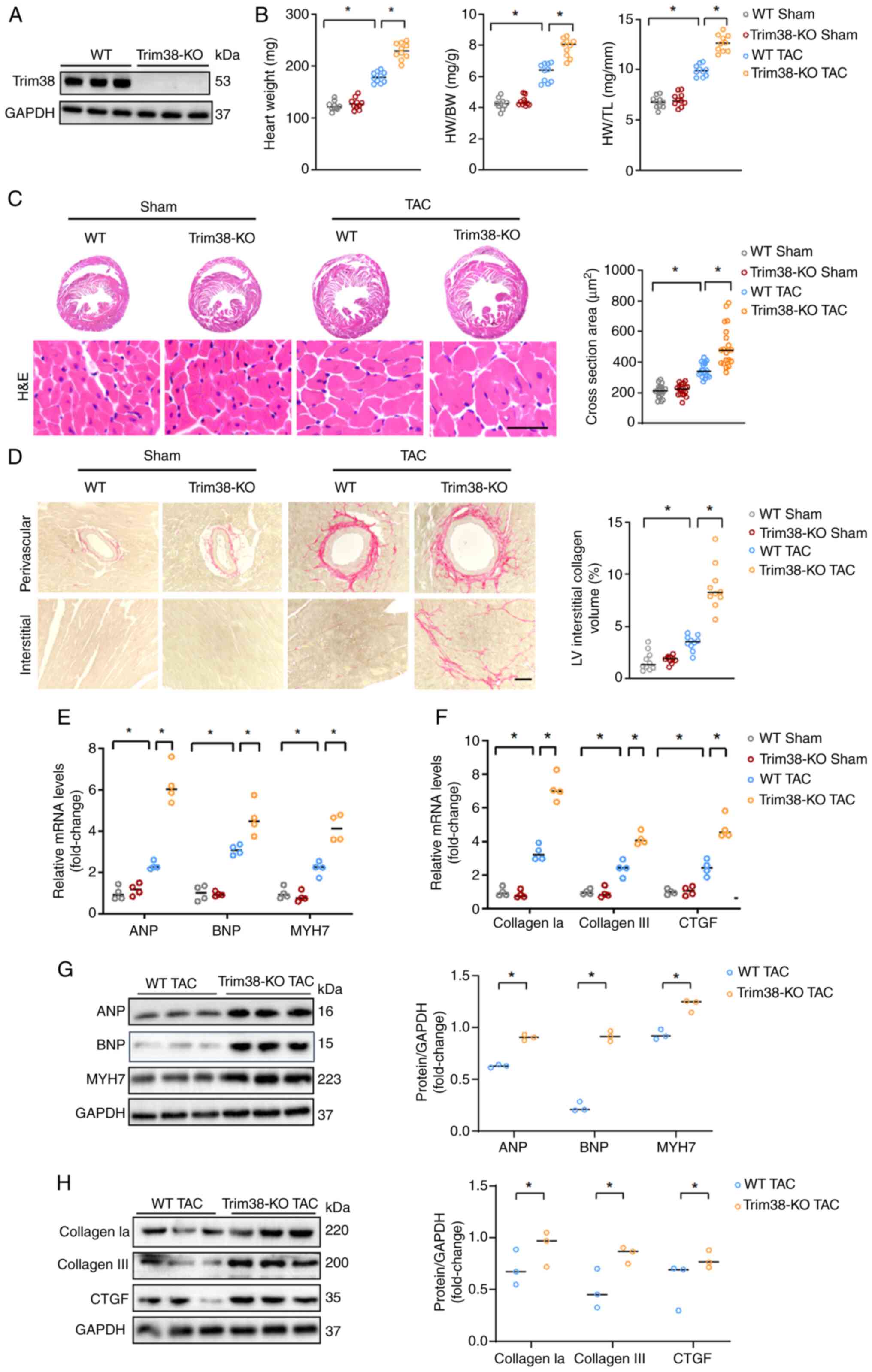

Trim38-KO mice were produced and Trim38 expression

was validated using western blotting to investigate whether Trim38

contributes to cardiac hypertrophy (Fig. 2A). At the baseline, there were no

significant differences in heart weight, myocardial hypertrophy and

myocardial fibrosis levels between WT sham mice and Trim38-KO sham

mice (Figs. 2B-F, and S1A and B). These findings suggested

that Trim38-KO had no significant impact on myocardial hypertrophy

and myocardial fibrosis under physiological conditions. However,

compared with in WT mice, heart weight, heart weight/body weight

ratio and heart weight/tibia length ratio were increased in

Trim38-KO mice 4 weeks after TAC (Fig. 2B). In addition, histological

analysis of cardiac tissue sections demonstrated a marked increase

in cardiomyocyte size upon H&E staining in the Trim38-KO TAC

group compared with in the WT TAC group (Fig. 2C). Furthermore, PSR staining

revealed that Trim38-KO significantly aggravated myocardial

fibrosis (Fig. 2D). Molecular

analyses, including qPCR and western blotting, confirmed that

Trim38-KO led to elevated mRNA and protein expression levels of

ANP, brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) and MYH7 in the heart

(Fig. 2E and G). Additionally,

Trim38-KO upregulated the expression of fibrosis markers, including

collagen type I α1 (collagen Ia), collagen III and connective

tissue growth factor (CTGF) following TAC (Fig. 2F and H). Taken together, these

findings suggested that Trim38-KO may contribute to the development

of cardiac hypertrophy.

| Figure 2Trim38-KO exacerbates cardiac

hypertrophy. (A) Trim38 expression levels in Trim38-KO mice were

detected using western blot analysis. (B) HW, HW/BW ratio and HW/TL

ratio of WT and Trim38-KO mice subjected to TAC (n=10). (C) H&E

staining of heart tissue sections from WT mice and Trim38-KO mice

(scale bars, 25 µm). Cell section area was quantified in

each group (n>50 cells/group). (D) Picro-sirius red staining

showing fibrosis of heart tissue sections from WT and Trim38-KO

mice (scale bars, 50 µm). Collagen volume was quantified in

each group (n>10 files/group). mRNA expression levels of (E)

hypertrophic markers ANP, BNP and MYH7, and (F) collagen Ia,

collagen III and CTGF in each group (n=4 independent experiments).

Western blot analyses of the expression levels of (G) ANP, BNP and

MYH7, and (H) collagen Ia, collagen III and CTGF in WT mice and

Trim38-KO mice after TAC. Blots represent one of three replicated

experiments. *P<0.05. ANP, atrial natriuretic

peptide; BNP, brain natriuretic peptide; BW, brain weight; collagen

Ia, collagen type I α1; CTGF, connective tissue growth factor;

H&E, hematoxylin and eosin; HW, heart weight; KO, knockout; LV,

left ventricle; MYH7, myosin heavy chain 7; TAC, transverse aortic

constriction; TL, tibia length; Trim38, tripartite motif 38; WT,

wild-type. |

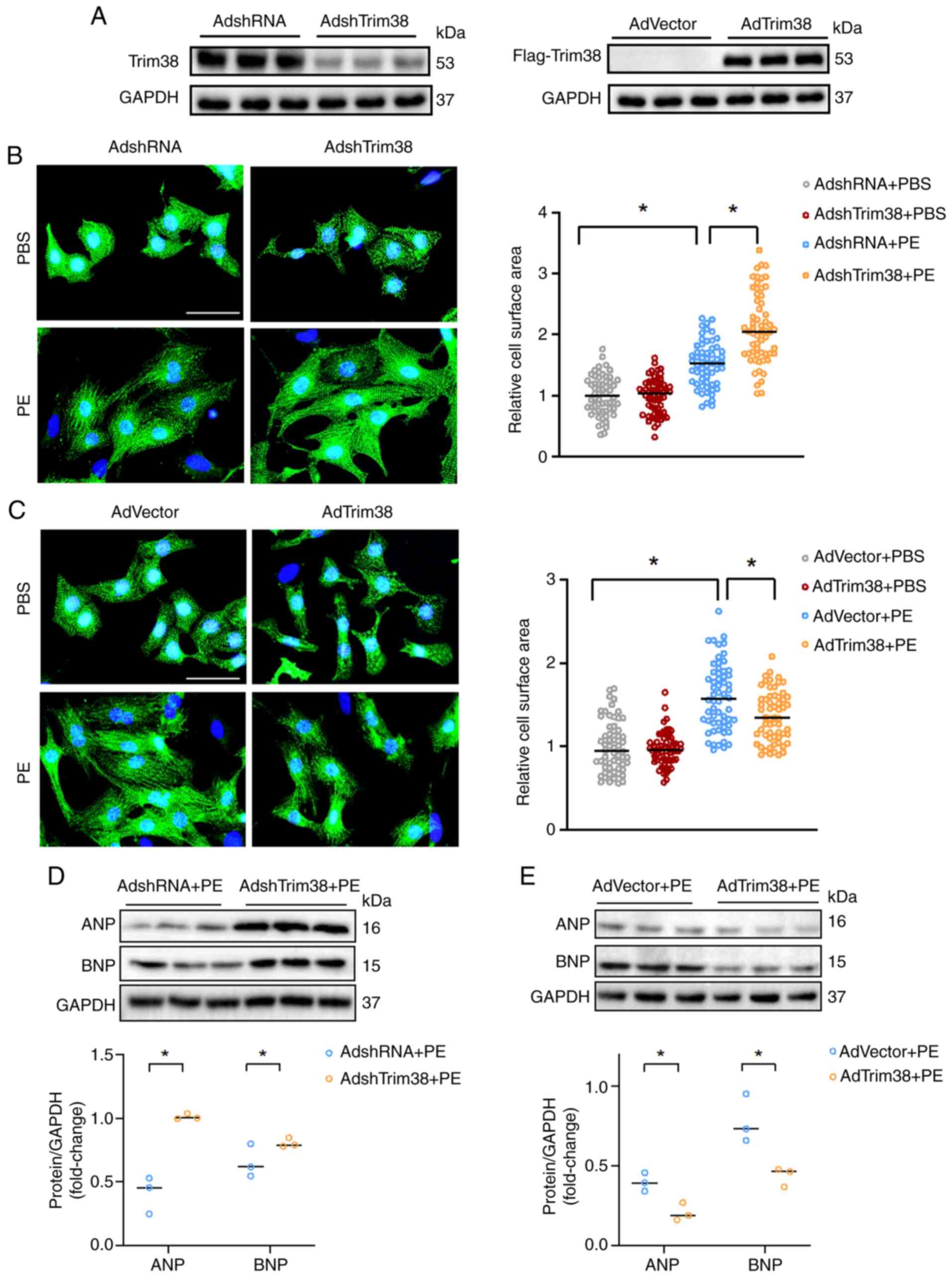

Trim38 ameliorates PE-induced

cardiomyocyte hypertrophy

The present study also investigated the role of

Trim38 in cardiomyocytes in vitro. AdshTrim38 infection was

used to downregulate Trim38 expression in NRCMs, while

AdFlag-Trim38 infection was used to overexpress Trim38 (Fig. 3A). After treatment with PE for 48

h, cells with Trim38 knockdown were of a larger size, and exhibited

enhanced expression levels of ANP and BNP, compared with in cells

infected with AdshRNA (Figs. 3B and

D, and S1C). By contrast,

Trim38 overexpression inhibited cardiomyocyte hypertrophy, and

downregulated PE-induced expression levels of ANP and BNP (Figs. 3C and E, and S1D). Thus, these findings demonstrated

that Trim38 could protect against cardiomyocyte hypertrophy in

vitro.

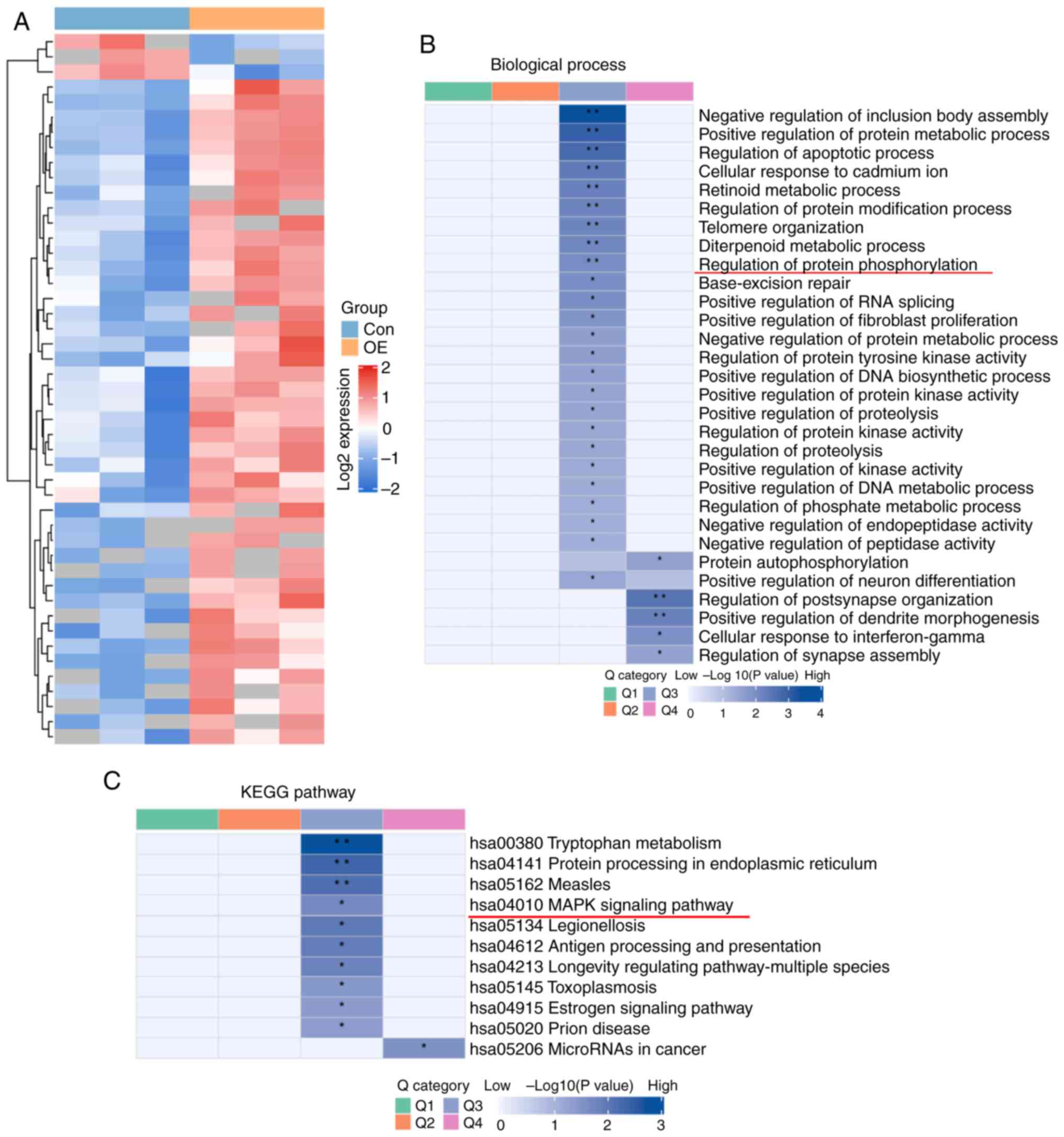

Trim38 protects against cardiac hypertrophy via

the TAK1/JNK/P38 signaling pathway. Given that Trim38 is an E3

ubiquitin ligase, ubiquitinomics analysis was conducted on

cardiomyocytes overexpressing Trim38 treated with PE to explore how

Trim38 regulates cardiac hypertrophy. A heat map demonstrating

differences in protein expression between the Trim38 overexpression

group and the control group is shown in Fig. 4A. Using cluster analysis,

differentially modified proteins were divided into four groups (Q1,

Q2, Q3 and Q4). GO enrichment analyses indicated that they were

involved in 'regulation of protein phosphorylation' (Fig. 4B). KEGG analysis indicated that

differentially modified proteins in the Q3 group (with fold changes

ranging from 1.5 to 2) were enriched in the 'MAPK signaling

pathway' (Fig. 4C). Therefore,

further studies placed a particular emphasis on phosphorylation of

the MAPK signaling pathway. Western blotting was conducted to

identify potential proteins involved in the MAPK signaling pathway,

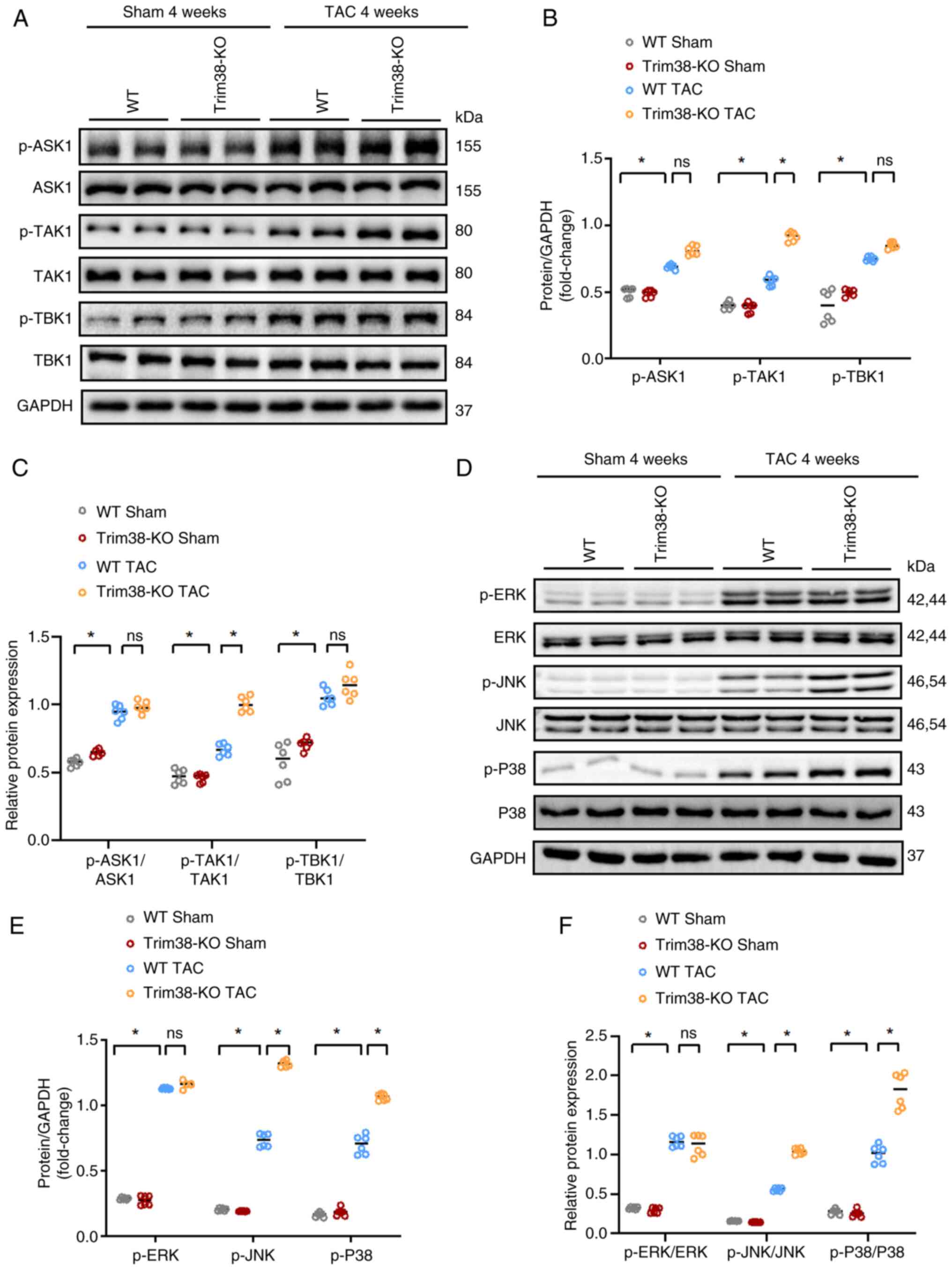

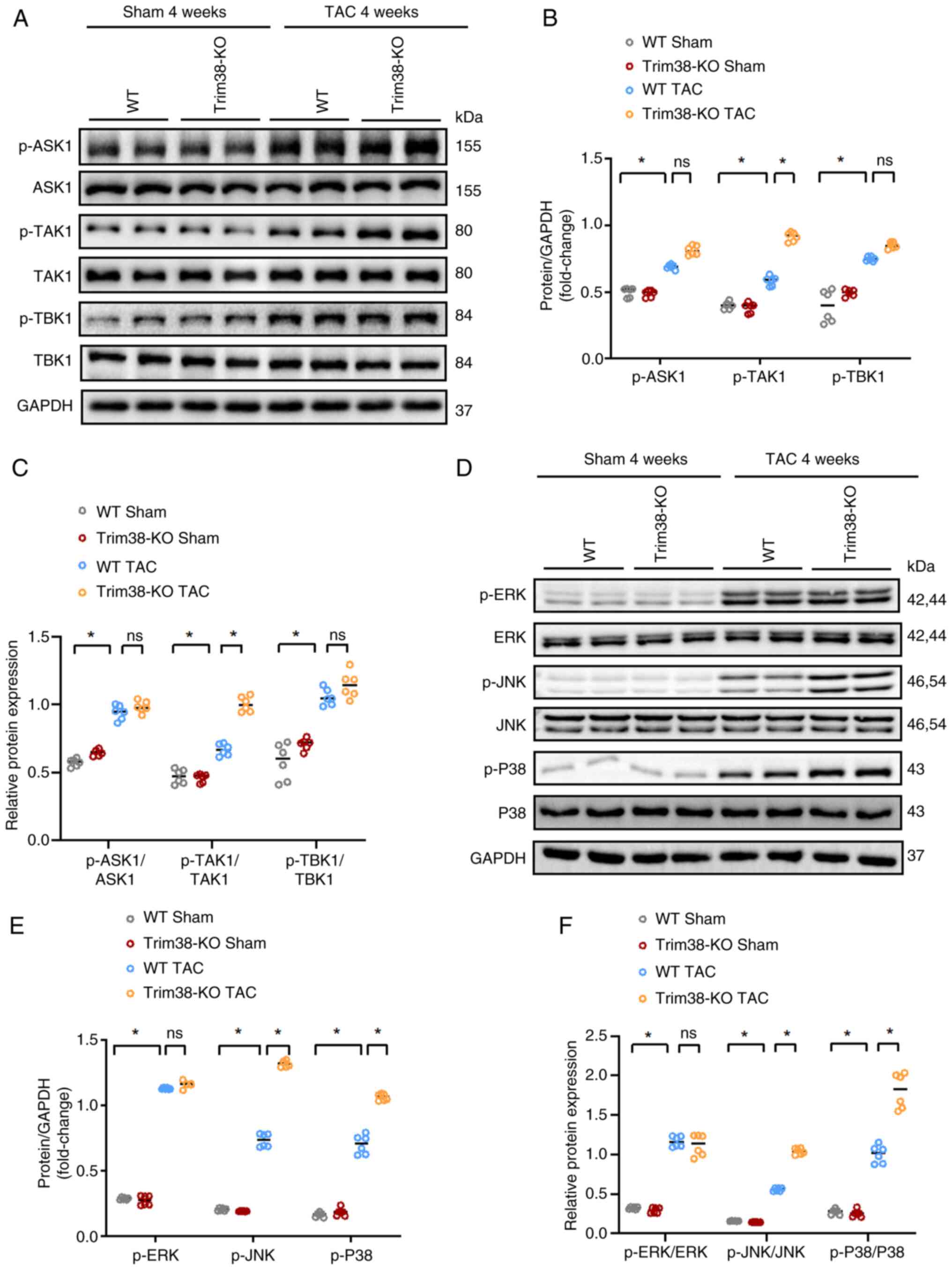

and it was unveiled that after TAC, TAK1 phosphorylation was

markedly upregulated in Trim38-KO mice compared with in the WT TAC

group (Fig. 5A-C). In addition,

Trim38-KO TAC mice exhibited a significant increase in the

phosphorylation of JNK and P38 during cardiac hypertrophy compared

with WT TAC mice (Fig. 5D-F).

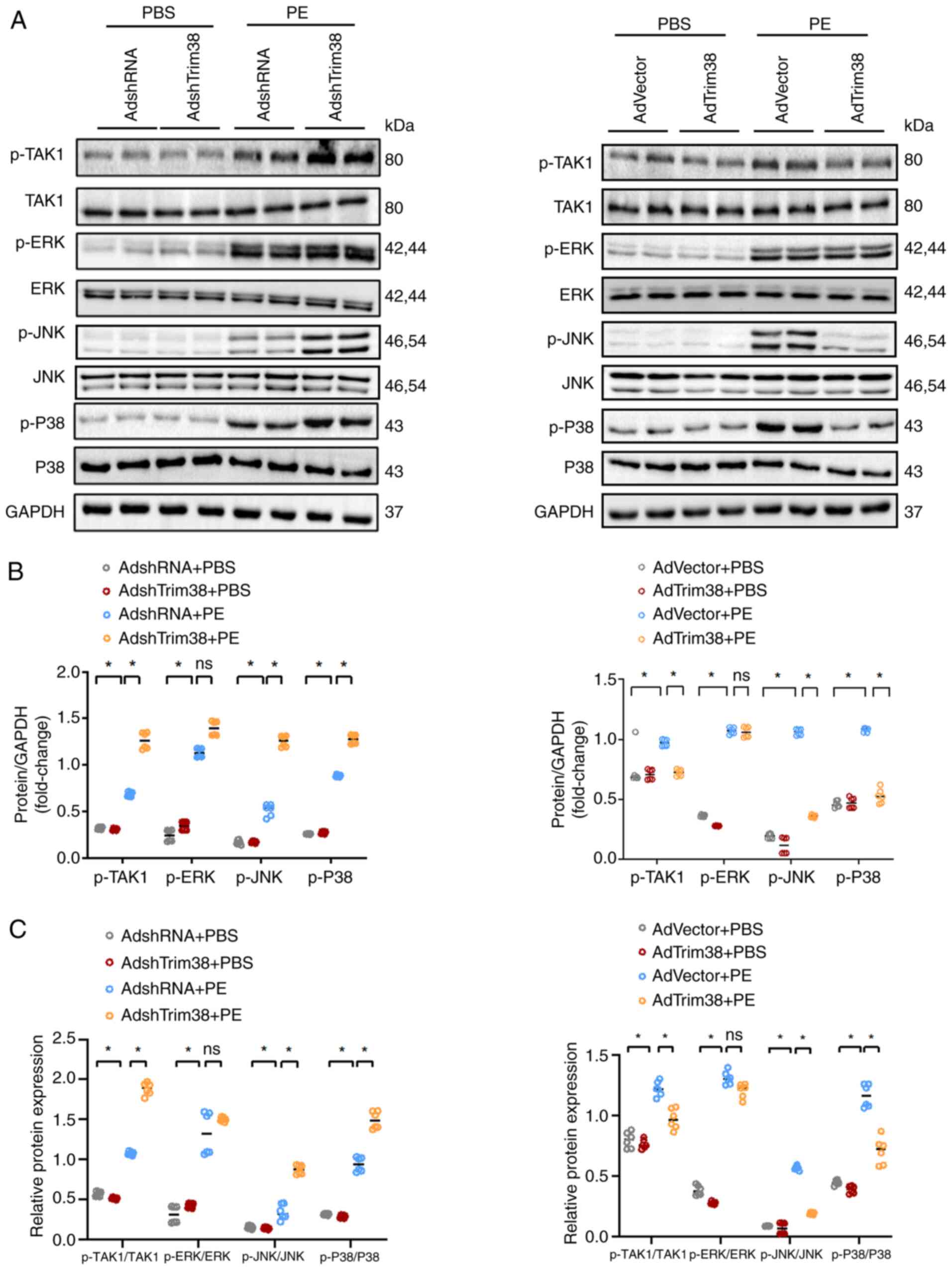

Subsequently, in vitro experiments were conducted to confirm

the underlying mechanism. Western blotting showed that Trim38

knockdown enhanced the phosphorylation of TAK1, JNK and P38,

whereas Trim38 overexpression inhibited the phosphorylation of

TAK1, JNK and P38 in NRCMs treated with PE (Fig. 6A-C). Overall, these results

preliminarily indicated that Trim38 inhibited activation of the

MAPK pathway in cardiac hypertrophy.

| Figure 5Trim38-KO leads to further activation

of the MAPK signaling pathway in mice after TAC. (A) Western blot

analysis comparing the total and p-levels of ASK1, TAK1 and TBK1

between Trim38-KO mice and WT mice. (B) Semi-quantification

analysis of phosphorylation levels of ASK1, TAK1 and TBK1 in each

group. (C) Ratios of p-/total protein levels for ASK1, TAK1 and

TBK1 in each group. (D) Western blot analysis of the total and

p-levels of ERK, JNK and P38 in Trim38-KO mice and WT mice. (E)

Semi-quantification of the phosphorylation levels of ERK, JNK and

P38 in hearts from Trim38-KO mice and WT mice. (F) p-ERK/total ERK,

p-JNK/total JNK and p-P38/total P38 ratios in each group. Blots

represent one of six replicated experiments. *P<0.05.

ASK1, apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1; KO, knockout; p-,

phosphorylated; TAC, transverse aortic constriction; Trim38,

tripartite motif 38; WT, wild-type. |

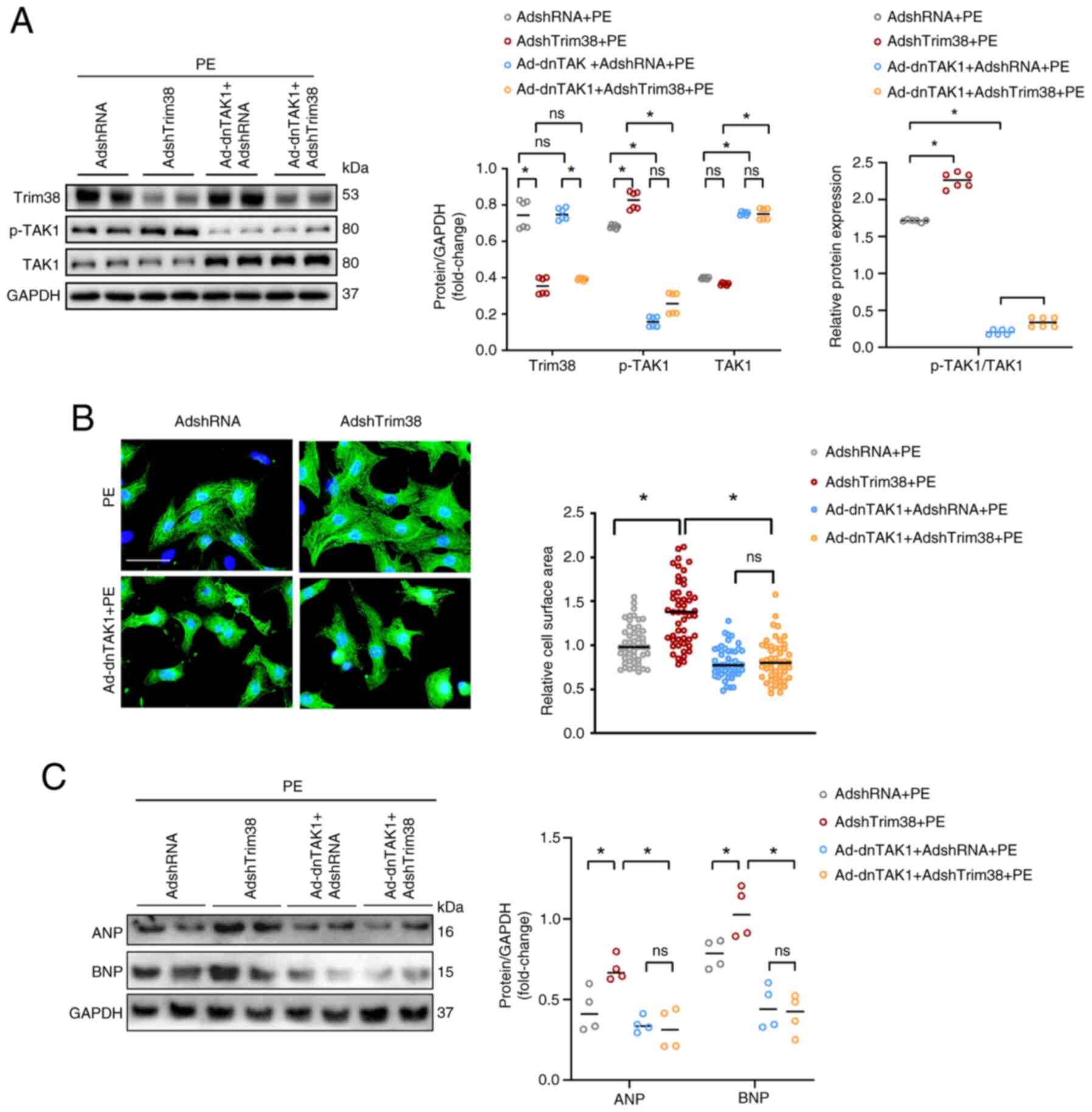

Blocking the activity of TAK1 ameliorates

Trim38 knockdown-induced cardiomyocyte hypertrophy

Ad-dnTAK1 was generated, which lacks kinase

activity, to function as a TAK1 inhibitor. This allowed for

investigation as to whether Trim38 modulates cardiac hypertrophy

via the TAK1/JNK/P38 signaling pathway. The dnTAK1 harbors a

dominant-negative mutation that abolishes its kinase activity and

effectively neutralizes the function of WT TAK1. Upon infection

with Ad-dnTAK1, this mutant form effectively neutralizes the

activity of WT TAK1 while maintaining its own kinase-inactive

state.

Ad-dnTAK1 was co-transfected into NRCMs with either

AdshRNA or AdshTrim38, and the following observations were made.

Under PBS conditions, compared with in cells infected with AdshRNA,

the expression levels of TAK1 were increased in cells

co-transfected with Ad-dnTAK1 and AdshRNA (Ad-dnTAK1 + AdshRNA),

whereas the expression levels of p-TAK1 remained unchanged

(Fig. S2A). Similarly, the cell

area was not significantly altered between these two groups

(Fig. S2B). These findings

suggested that, despite the increased expression levels of TAK1,

its biological activity remained unaltered at baseline due to the

dominant-negative effect of Ad-dnTAK1; this prevents the

phosphorylation of TAK1 and any resultant phenotypic alterations in

the cells.

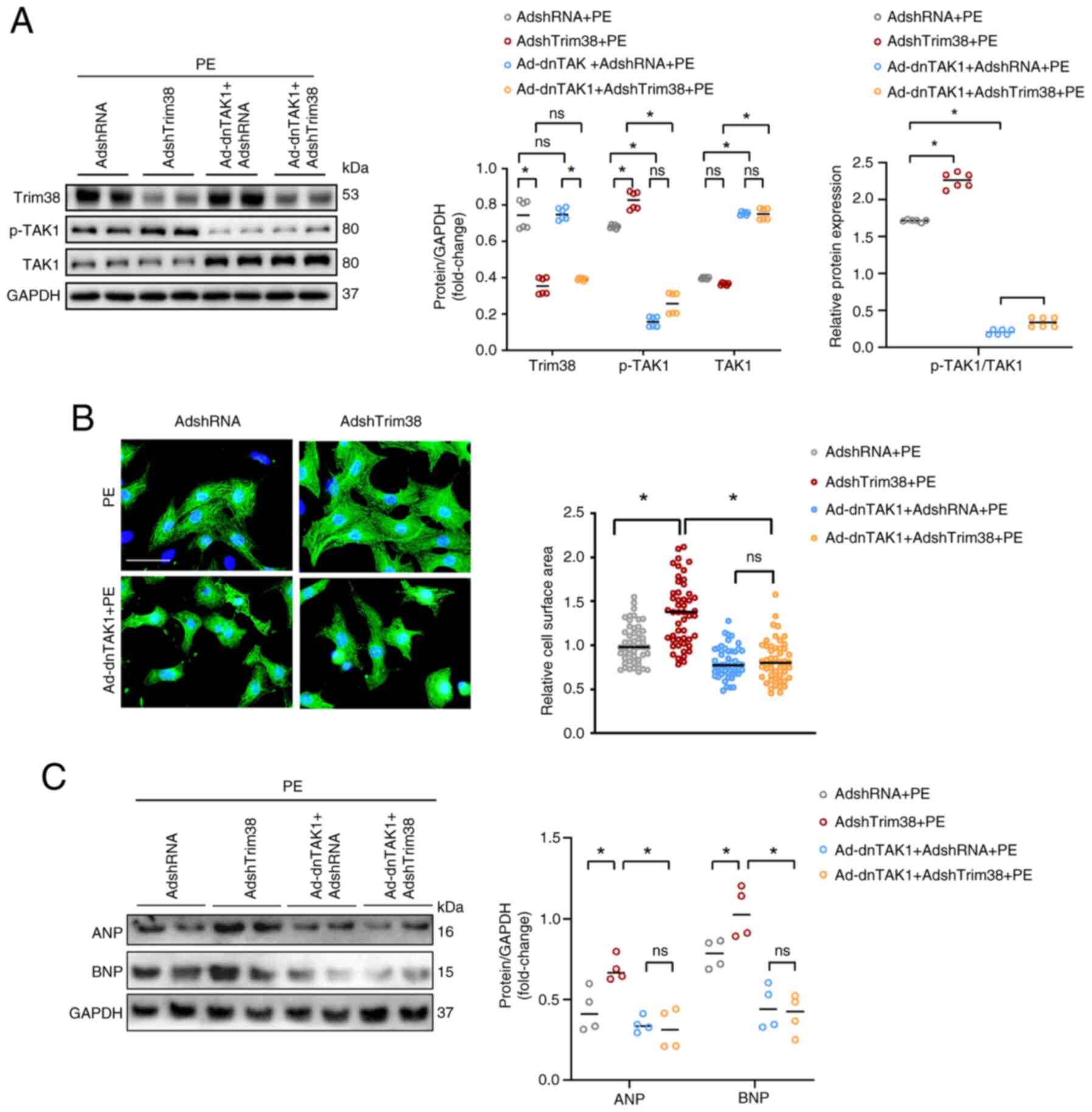

Upon treatment with PE, consistent with the

aforementioned findings, Trim38 knockdown in NRCMs resulted in

increased TAK1 phosphorylation (Fig.

7A) accompanied by an enlargement of cell area (Fig. 7B), and an upregulation of the

hypertrophy markers ANP and BNP compared with in NRCMs infected

with AdshRNA (Figs. 7C and

S1F). Notably, co-infection

with Ad-dnTAK1 and AdshRNA significantly suppressed TAK1

phosphorylation relative to AdshRNA alone. A parallel phenomenon

was observed in AdshTrim38-infected cells: Co-infection with

AdshTrim38 and Ad-dnTAK1 led to a significant reduction in TAK1

phosphorylation compared with infection with AdshTrim38 alone

(Figs. 7A and S1E). Crucially, comparing the NRCMs

co-infected with Ad-dnTAK1 and AdshTrim38 to those infected with

Ad-shTrim38 alone revealed that blockade of TAK1 activity via

Ad-dnTAK1 abrogated the pro-hypertrophic effects of Trim38

deficiency in cardiomyocytes (Figs.

7A-C and S1F).

Collectively, these findings indicated that Trim38 alleviated

cardiomyocyte hypertrophy in a manner that is dependent on TAK1

activity.

| Figure 7TAK1 is essential for Trim38-mediated

improvement of cardiac hypertrophy. (A) Western blot analysis and

semi-quantification of Trim38, TAK1 and p-TAK1 in neonatal rat

cardiomyocytes infected with the indicated Ads and treated with PE.

The p-TAK1/TAK1 ratio is also displayed. Blots represent one of six

replicated experiments. (B) Representative images of α-actinin

staining and quantification of cell cross-sectional area for each

group (n>50 cells/group) (scale bar, 20 µm). (C) Western

blot analysis and semi-quantitation of the expression levels of ANP

and BNP in each group. Blots represent one of four replicated

experiments. *P<0.05. Ad, adenovirus; ANP, atrial

natriuretic peptide; BNP, brain natriuretic peptide; dnTAK1,

dominant-negative TAK1; p-, phosphorylated; PE, phenylephrine; sh,

short hairpin; Trim38, tripartite motif 38. |

Discussion

A previous study revealed that Trim38 expression is

significantly downregulated within the cardiac tissues of mice

subjected to LAD coronary artery permanent ligation, a

well-characterized model of acute myocardial infarction (AMI), and

is also reduced in coronary blood samples from patients with AMI.

Furthermore, this previous study demonstrated that suppression of

Trim38 can enhance the proliferative and secretory activities of

cardiac fibroblasts (CFs), thereby exacerbating cardiac fibrosis

(9). Conversely, upregulation of

Trim38 expression has been observed to mitigate these fibrotic

responses, highlighting its protective role against cardiac

fibrosis under ischemic conditions (9). The present study revealed that

Trim38 confers protection against pathological myocardial

hypertrophy in response to pressure overload. Initial observations

demonstrated downregulated Trim38 expression in hypertrophic

cardiomyocytes and cardiac tissues. To further investigate this

phenomenon, Trim38-KO mice were generated. Under physiological

conditions, these mice exhibited no significant differences in

cardiac structure or function compared with their WT counterparts;

however, under conditions of pressure overload, Trim38-KO

exacerbated pathological hypertrophy, as evidenced by increased

heart weight, enlarged cardiomyocyte area in cardiac tissue

sections and elevated expression of hypertrophy markers, such as

MYH7, ANP and BNP, in Trim38-KO cardiac tissues. Consistent with

these in vivo findings, parallel in vitro experiments

demonstrated that Trim38 knockdown led to increased cardiomyocyte

size and upregulation of hypertrophy markers, whereas Trim38

overexpression resulted in reduced cell size and downregulation of

these markers under PE stimulation. Collectively, these findings

confirmed that Trim38 may have a crucial role in modulating

pathological hypertrophy. Specifically, Trim38 could attenuate

cardiac hypertrophy through inhibition of the JNK/P38 signaling

pathway. Mechanistic insights further revealed that regulation of

TAK1 phosphorylation by Trim38 is a critical factor in this

process. To the best of our knowledge, the present study is the

first to provide evidence that Trim38 alleviates pressure

overload-induced pathological hypertrophy by inhibiting the

TAK1/JNK/P38 signaling pathway.

The development of cardiac hypertrophy is

accompanied by adaptive changes in protein expression, which are

regulated by various factors, including gene transcription, mRNA

translation and post-translational modifications (PTMs) (18). PTMs increase the complexity and

diversity of proteins by adding or introducing new functional

groups (19). Ubiquitination is

a common form of PTM and a reversible process in which ubiquitin

binds to the amino acid side, or C-terminal or N-terminal of

proteins. Through diverse modifications, specifically the

structural variability of ubiquitin chains formed by distinct

lysine linkages (e.g., K48, K63) or linear M1 linkages, and

specific recognition mechanisms, ubiquitination can rapidly and

flexibly regulate signaling pathways without relying on changes in

gene expression or waiting for transcription and translation

processes. The dynamic nature of ubiquitination may make it more

efficient than transcriptional regulation, which requires the

activation of gene expression and the synthesis of new proteins

(20). Ubiquitination serves a

crucial role in determining protein structure, localization and

function, playing a complex and precise regulatory role in cardiac

hypertrophy (21). Trim family

proteins are involved in various processes associated with cardiac

hypertrophy through their ubiquitin ligase activity. These proteins

facilitate the ubiquitination and degradation of specific

substrates, which directly impacts the signaling pathways and

protein turnover associated with hypertrophic responses. Notably,

Trim65 has been demonstrated to prevent pathological cardiac

hypertrophy by promoting mitochondrial autophagy through the

Jak1/Stat1 signaling pathway (22). Moreover, Trim44 has been reported

to promote cardiac hypertrophy by upregulating the expression of

NOX4 and enhancing ferroptosis (23). The present study observed a

decreased expression of Trim38 in cardiac hypertrophy in

vivo and in vitro. After TAC, Trim38-KO increased cell

size, aggravated fibrosis, and upregulated the expression of

hypertrophic and fibrosis markers. Consequently, these findings

suggested that Trim38 serves a crucial role in alleviating pressure

overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy.

Ubiquitination experiments were conducted to

elucidate the underlying mechanisms of Trim38 in cardiac

hypertrophy. Using KEGG and GO enrichment analyses, several key

pathways were identified. Notably, the MAPK pathway emerged as a

classical pathway associated with the progression of cardiac

hypertrophy. It has previously been shown that Trim38 suppresses

cardiac fibrosis by attenuating the TAK1/MAPK signaling pathway in

CFs (9). Consequently, the

present study focused on the MAPK signaling pathway and discovered

that Trim38 can modulate phosphorylation within this pathway.

Multiple PTMs have been reported to maintain cellular homeostasis

(24), and the cooperation of

ubiquitination with other forms of PTMs is crucial for the

orchestration of biological activities. The interplay between

ubiquitination and phosphorylation regulates cellular processes and

has been extensively explored in previous studies (25-27). Skp1/cullin/F box proteins (SCF)

have been well identified as ubiquitin ligases responsible for

phosphorylation-mediated ubiquitination. The F-box domain of SCF

recognizes and binds to phosphodegron motifs, leading to substrate

polyubiquitination, which typically results in proteasomal

degradation (28). In addition

to direct interaction with phosphorylated substrates, Trim16 has

been demonstrated to ubiquitinate both TAK1 and p-TAK1, and promote

the proteasomal degradation of p-TAK1 in nonalcoholic

steatohepatitis through K-48 ubiquitination (29).

The MAPK signaling pathway is a highly conserved

pathway that facilitates the activation of numerous transcription

factors. It is activated in the hypertrophic myocardial tissue of

mice induced by PE or pressure overload and in diseased human

hearts (30). TAK1 functions as

an 'initiation switch' that activates the MAPK signaling pathway,

and upregulation of TAK1 phosphorylation appears to be an adaptive

mechanism after TAC. Cardiac-specific ablation of TAK1 in mice has

been shown to predispose them to cardiac hypertrophy and HF

(31). Furthermore, the results

of the present study revealed that overexpression of Trim38

inhibited the phosphorylation of TAK1, while Trim38 knockdown

upregulated p-TAK1 expression and activated the JNK/P38 signaling

pathway. To determine whether Trim38 protects against cardiac

hypertrophy via p-TAK1, dnTak1 was used to block TAK1 binding to

TAB1, thereby inhibiting TAK1 activation (32). p-TAK1 inactivation reversed cell

enlargement and inhibited the expression of hypertrophic markers

induced by Trim38 knockdown in vitro. Taken together, these

findings suggested that Trim38 may ameliorate cardiac hypertrophy

by inhibiting TAK1 phosphorylation.

The interaction between Trim38 and TAK1 has been

investigated in several studies. Mechanistically, TAK1 activation

necessitates the binding of TAB1, TAB2 and TAB3 to form the

TAK1-TAB complex (33). TAB1

triggers the phosphorylation of TAK1, whereas TAB2 links TAK1 to

the upstream proteins. Moreover, TAB2 and TAB3 serve a crucial role

in maintaining the activation of TAK1 (34). Notably, emerging evidence has

highlighted Trim38 as a key modulator of the TAK1-TAB complex

across diverse pathological contexts, suggesting its potential role

in fine-tuning TAK1-mediated signaling cascades. Previous studies

have indicated that Trim38 mediates lysosome-dependent degradation

of TAB2, thereby inhibiting TAK1 and the NFκB signaling pathway

in vitro (35,36). In CFs treated with PE, Trim38

overexpression has been shown to inhibit total ubiquitination and

K63-linked ubiquitination of TAK1, which seems to be inconsistent

with the fact that Trim38 acts as an E3 ubiquitin ligase that can

promote ubiquitination. Subsequent analysis in the same study

unveiled that Trim38 can promote TAB2 degradation, resulting in

reduced TAK1 ubiquitination and phosphorylation (9). A similar observation has been made

in NAFLD; Trim38 overexpression has been shown to downregulate TAB2

expression, thereby inhibiting the phosphorylation of TAK1 and MAPK

signaling pathways (10). The

present study confirmed previous findings and contributed

additional evidence that Trim38 can protect against cardiac

hypertrophy by suppressing TAK1 phosphorylation and activating the

JNK/P38 signaling pathway. Based on previous findings, it was

hypothesized that the reduction in TAK1 phosphorylation may be

attributed to increased Trim38-mediated degradation of TAB2. This

phenomenon could subsequently disrupt the binding of TAK1 to its

upstream adaptors. However, further studies are needed to fully

understand the underlying mechanisms.

There are several limitations in the present study

that warrant acknowledgment. Firstly, a notable limitation of the

study is the lack of cardiac ultrasound data, which prevented a

direct assessment of ventricular wall thickness and overall cardiac

function. While histological and molecular analyses provide

supportive evidence for cardiac hypertrophy, these methods cannot

fully replicate the distinct advantages of cardiac ultrasound in

evaluating cardiac structure and function. Future studies should

incorporate cardiac ultrasound to offer a more comprehensive

evaluation of cardiac function and myocardial hypertrophy-related

pathological changes. Additionally, the current study did not

provide conclusive evidence on the decrease of Trim38 in the blood

of patients with HF. Based on RNA-sequencing data from the Human

Protein Atlas (https://www.proteinatlas.org/ENSG00000111666-TRIM38)

(37) and GeneCards (https://www.genecards.org/cgi-bin/carddisp.pl?gene=TRIM38)

(38), Trim38 demonstrates low

expression levels in whole blood (TPM <1). This suggests

potentially low concentrations of TRIM38 in circulation, thereby

presenting challenges for its detection. Moreover, further

investigation is necessary to explore the specific mechanism

underlying the interaction between Trim38 and TAK1 in cardiac

hypertrophy. Finally, clinical studies are required to validate the

association between Trim38 and pressure overload-induced cardiac

hypertrophy.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated that

Trim38 serves a protective role against pressure overload-induced

pathological cardiac hypertrophy by suppressing the TAK1/JNK/p38

signaling axis. By contrast, Trim38 deficiency exacerbated

myocardial hypertrophy and upregulated hypertrophic biomarkers

(ANP/BNP). Mechanistically, Trim38 deficiency may activate TAK1

phosphorylation and the downstream MAPK pathway. Conversely, its

overexpression has been shown to inhibit TAK1 phosphorylation and

downstream MAPK pathway activation. Crucially, the detrimental

effects of Trim38 knockdown were revealed to be mitigated by TAK1

inhibition, identifying TAK1 as a central mediator of

Trim38-mediated cardioprotection. To the best of our knowledge, the

present study is the first to highlight Trim38 as a novel negative

regulator of pathological cardiac remodeling, positioning it as a

promising therapeutic target for combating heart failure.

Supplementary Data

Availability of data and materials

The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been

deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE partner

repository with the dataset identifier PXD060763 or at the

following URL: https://www.ebi.ac.uk/pride/archive/projects/PXD060763.

The other data generated in the present study may be requested from

the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

LJ and LH conceived the study and provided financial

support. YP, LW, JX, XX and CG performed the experiments, collected

the data and prepared the figures. YP was a major contributor in

writing the manuscript. YP and LW confirm the authenticity of all

the raw data. All authors contributed to the article, and read and

approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent for

participation

The animal study was reviewed and approved by

Shanghai Tongren Hospital Ethics Committee (approval no.

A2023-086-01; Shanghai, China).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Abbreviations:

|

HF

|

heart failure

|

|

Trim

|

tripartite motif

|

|

NAFLD

|

nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

|

|

MYH7

|

myosin heavy chain 7

|

|

ANP

|

atrial natriuretic peptide

|

|

TAC

|

transverse aortic constriction

|

|

PE

|

phenylephrine

|

|

KO

|

knockout

|

|

WT

|

wild-type

|

|

KEGG

|

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and

Genomes

|

|

GO

|

Gene Ontology

|

|

PTMs

|

post-translational modifications

|

|

SCF

|

Skp1/cullin/F box proteins

|

|

H&E

|

hematoxylin and eosin

|

|

PSR

|

picro-sirius red

|

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Funding

No funding was received.

References

|

1

|

McDonagh TA, Metra M, Adamo M, Gardner RS,

Baumbach A, Böhm M, Burri H, Butler J, Čelutkienė J, Chioncel O, et

al: 2021 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute

and chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J. 42:3599–3726. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Levy D, Larson MG, Vasan RS, Kannel WB and

Ho KK: The progression from hypertension to congestive heart

failure. JAMA. 275:1557–1562. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Martin TG, Juarros MA and Leinwand LA:

Regression of cardiac hypertrophy in health and disease: Mechanisms

and therapeutic potential. Nat Rev Cardiol. 20:347–363. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Katz AM and Rolett EL: Heart failure: When

form fails to follow function. Eur Heart J. 37:449–454. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Dikic I: Proteasomal and autophagic

degradation systems. Annu Rev Biochem. 86:193–224. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Hu MM and Shu HB: Multifaceted roles of

TRIM38 in innate immune and inflammatory responses. Cell Mol

Immunol. 14:331–338. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Xue Q, Zhou Z, Lei X, Liu X, He B, Wang J

and Hung T: TRIM38 negatively regulates TLR3-mediated IFN-β

signaling by targeting TRIF for degradation. PLoS One.

7:e468252012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Hu MM, Yang Q, Xie XQ, Liao CY, Lin H, Liu

TT, Yin L and Shu HB: Sumoylation promotes the stability of the DNA

sensor cGAS and the adaptor STING to regulate the kinetics of

response to DNA virus. Immunity. 45:555–569. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Lu Z, Hao C, Qian H, Zhao Y, Bo X, Yao Y,

Ma G and Chen L: Tripartite motif 38 attenuates cardiac fibrosis

after myocardial infarction by suppressing TAK1 activation via

TAB2/3 degradation. iScience. 25:1047802022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Yao X, Dong R, Hu S, Liu Z, Cui J, Hu F,

Cheng X, Wang X, Ma T, Tian S, et al: Tripartite motif 38

alleviates the pathological process of NAFLD-NASH by promoting TAB2

degradation. J Lipid Res. 64:1003822023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Pang Y, Ma M, Wang D, Li X and Jiang L:

TANK promotes pressure overload induced cardiac hypertrophy via

activating AKT signaling pathway. Front Cardiovasc Med.

8:6875402021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Ehler E, Moore-Morris T and Lange S:

Isolation and culture of neonatal mouse cardiomyocytes. J Vis Exp.

6:501542013.

|

|

13

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Cox J and Mann M: MaxQuant enables high

peptide identification rates, individualized p.p.b.-range mass

accuracies and proteome-wide protein quantification. Nat

Biotechnol. 26:1367–1372. 2008. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

UniProt Consortium: Uniprot: The universal

protein knowledgebase in 2023. Nucleic Acids Res. 51:D523–D531.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

16

|

Cantalapiedra CP, Hernández-Plaza A,

Letunic I, Bork P and Huerta-Cepas J: eggNOG-mapper v2: Functional

annotation, orthology assignments, and domain prediction at the

metagenomic scale. Mol Biol Evol. 38:5825–5829. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Kanehisa M, Furumichi M, Tanabe M, Sato Y

and Morishima K: KEGG: New perspectives on genomes, pathways,

diseases and drugs. Nucleic Acids Res. 45:D353–D361. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

18

|

Oka T, Akazawa H, Naito AT and Komuro I:

Angiogenesis and cardiac hypertrophy: Maintenance of cardiac

function and causative roles in heart failure. Circ Res.

114:565–571. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Wu X, Xu M, Geng M, Chen S, Little PJ, Xu

S and Weng J: Targeting protein modifications in metabolic

diseases: Molecular mechanisms and targeted therapies. Signal

Transduct Target Ther. 8:2202023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Cockram PE, Kist M, Prakash S, Chen SH,

Wertz IE and Vucic D: Ubiquitination in the regulation of

inflammatory cell death and cancer. Cell Death Differ. 28:591–605.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Qiu M, Chen J, Li X and Zhuang J:

Intersection of the ubiquitin-proteasome system with oxidative

stress in cardiovascular disease. Int J Mol Sci. 23:121972022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Liu H, Zhou Z, Deng H, Tian Z, Wu Z, Liu

X, Ren Z and Jiang Z: Trim65 attenuates isoproterenol-induced

cardiac hypertrophy by promoting autophagy and ameliorating

mitochondrial dysfunction via the Jak1/Stat1 signaling pathway. Eur

J Pharmacol. 949:1757352023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Wu L, Jia M, Xiao L, Wang Z, Yao R, Zhang

Y and Gao L: TRIM-containing 44 aggravates cardiac hypertrophy via

TLR4/NOX4-induced ferroptosis. J Mol Med (Berl). 101:685–697. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Lee JM, Hammarén HM, Savitski MM and Baek

SH: Control of protein stability by post-translational

modifications. Nat Commun. 14:2012023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Song L and Luo ZQ: Post-translational

regulation of ubiquitin signaling. J Cell Biol. 218:1776–1786.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Liu P, Cong X, Liao S, Jia X, Wang X, Dai

W, Zhai L, Zhao L, Ji J, Ni D, et al: Global identification of

phospho-dependent SCF substrates reveals a FBXO22 phosphodegron and

an ERK-FBXO22-BAG3 axis in tumorigenesis. Cell Death Differ.

29:1–13. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

27

|

Zhu GW, Chen H, Liu SY, Lin PH, Lin CL and

Ye JX: PPM1B degradation mediated by TRIM25 ubiquitination

modulates cell cycle and promotes gastric cancer growth. Sci Rep.

15:61602025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Barbour H, Nkwe NS, Estavoyer B, Messmer

C, Gushul-Leclaire M, Villot R, Uriarte M, Boulay K, Hlayhel S,

Farhat B, et al: An inventory of crosstalk between ubiquitination

and other post-translational modifications in orchestrating

cellular processes. iScience. 26:1062762023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Wang L, Zhang X, Lin ZB, Yang PJ, Xu H,

Duan JL, Ruan B, Song P, Liu JJ, Yue ZS, et al: Tripartite motif 16

ameliorates nonalcoholic steatohepatitis by promoting the

degradation of phospho-TAK1. Cell Metab. 33:1372–1388.e7. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Dorn GN II and Force T: Protein kinase

cascades in the regulation of cardiac hypertrophy. J Clin Invest.

115:527–537. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Li L, Chen Y, Doan J, Murray J, Molkentin

JD and Liu Q: Transforming growth factor β-activated kinase 1

signaling pathway critically regulates myocardial survival and

remodeling. Circulation. 130:2162–2172. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Xie M, Zhang D, Dyck JR, Li Y, Zhang H,

Morishima M, Mann DL, Taffet GE, Baldini A, Khoury DS and Schneider

MD: A pivotal role for endogenous TGF-beta-activated kinase-1 in

the LKB1/AMP-activated protein kinase energy-sensor pathway. Proc

Natl Acad Sci USA. 103:17378–17383. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Hirata Y, Takahashi M, Morishita T,

Noguchi T and Matsuzawa A: Post-translational modifications of the

TAK1-TAB complex. Int J Mol Sci. 18:2052017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Xu YR and Lei CQ: TAK1-TABs complex: A

central signalosome in inflammatory responses. Front Immunol.

11:6089762021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Hu MM, Yang Q, Zhang J, Liu SM, Zhang Y,

Lin H, Huang ZF, Wang YY, Zhang XD, Zhong B and Shu HB: TRIM38

inhibits TNFα- and IL-1β-triggered NF-κB activation by mediating

lysosome-dependent degradation of TAB2/3. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

111:1509–1514. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Kim K, Kim JH, Kim I, Seong S and Kim N:

TRIM38 regulates NF-κB activation through TAB2 degradation in

osteoclast and osteoblast differentiation. Bone. 113:17–28. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Uhlén M, Fagerberg L, Hallström BM,

Lindskog C, Oksvold P, Mardinoglu A, Sivertsson Å, Kampf C,

Sjöstedt E, Asplund A, et al: Proteomics. Tissue-based map of the

human proteome. Science. 347:12604192015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Stelzer G, Rosen N, Plaschkes I, Zimmerman

S, Twik M, Fishilevich S, Stein TI, Nudel R, Lieder I, Mazor Y, et

al: The genecards suite: From gene data mining to disease genome

sequence analyses. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics. 54:1–30. 2016.

|