The skin, as the largest organ of the human body,

provides a protective barrier against mechanical, microbial,

chemical and allergenic insults (1). The gastrointestinal tract, a

crucial mucosal immune organ, maintains immune homeostasis through

dynamic interactions between the microbiome and the intestinal

immune system (2). The

intestinal mucosal immune function is mediated by the mucus layer,

epithelial barrier and resident immune cells, all of which engage

with the gut microbiota (3). The

collective genome of gut microbes is termed the 'gut microbiome,'

which is intimately linked to long-term health (4). As interfaces with the external

environment, both the gut and skin host diverse microbial

communities and are richly innervated and vascularized. As early as

1930, John H. Stokes and Donald M. Pillsbury proposed an intrinsic

relationship between gut microbiota and skin inflammation,

conceptualizing the 'gut-skin axis' (5). Recent advances in microbiology and

immunology have begun to clarify the mechanisms through which gut

microbiota influences skin health. Lee and Sung (6) identified immune pathways by which

alterations in gut and skin microbiota contribute to

dermatopathology, while Szanto et al (7) suggested that gut microbiota

modulation may hold therapeutic potential for specific skin

disorders. These findings not only validate the gut-skin axis

theory but also open new avenues for clinical dermatology. In the

context of increasing antibiotic resistance, therapeutic strategies

are shifting toward alternatives such as probiotics, prebiotics and

dietary interventions, which can restore microbial balance and

modulate immune responses to improve skin health (8,9).

This review examines novel strategies for treating skin diseases

from the perspective of the gut-skin axis and explores future

translational research directions.

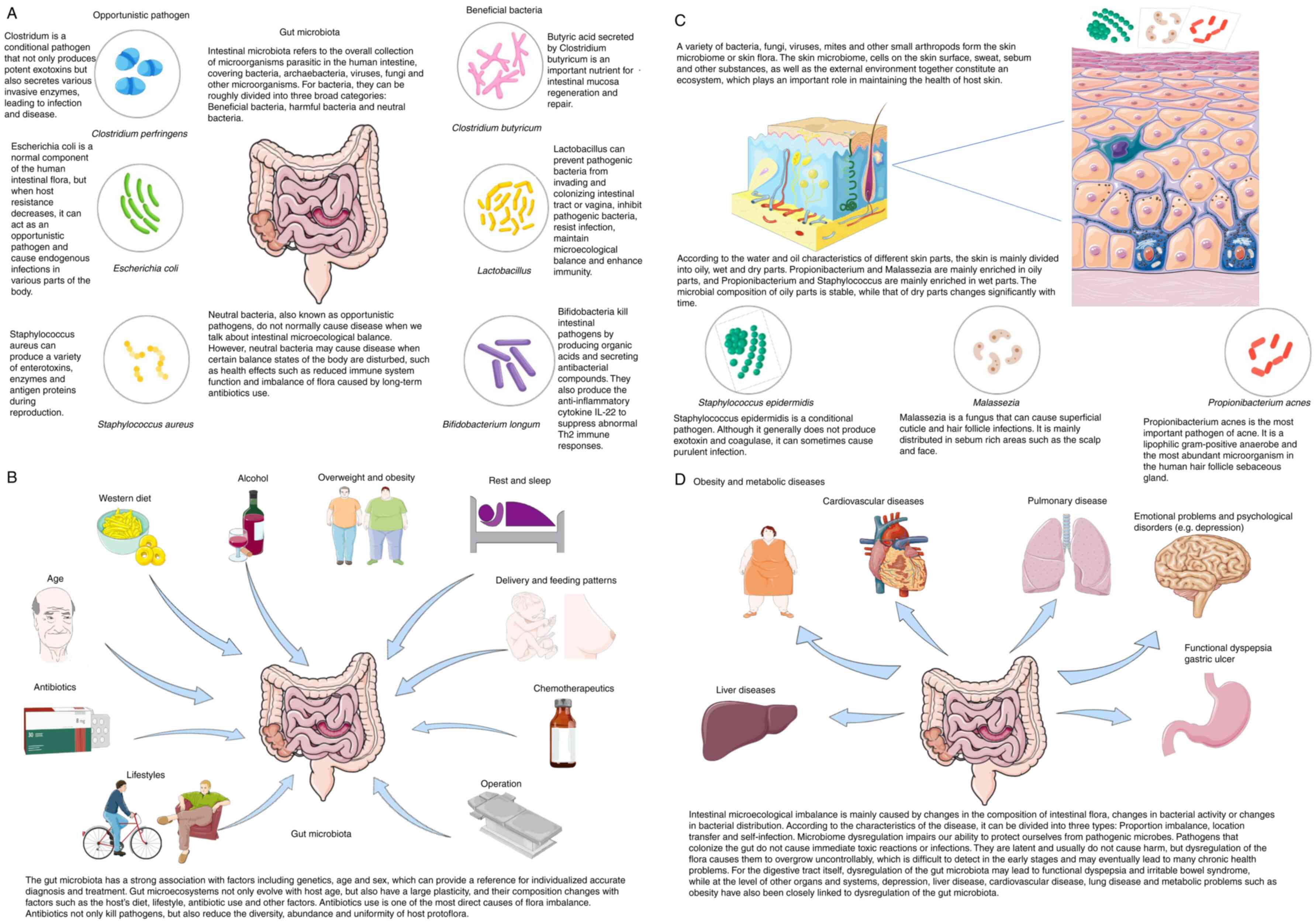

The gut microbiota comprises diverse and dynamic

microbial communities residing in the human gastrointestinal tract

(10) (Fig. 1A). Anatomically and functionally,

the gut is divided into the small and large intestines, each with

distinct physiological conditions and microbial populations

(11). Numerous factors

influence the gut microbiota (Fig.

1B), with diet being a primary determinant of its structure and

function (12). The gut

microbiota evolves from infancy and changes in composition and

diversity over time within an individual (13). There is considerable

interindividual variation in gut microbial composition. Through

host-microbe coevolution, the gut microbiome plays a critical role

in regulating host physiology, including metabolism, immune

development and behavioral responses (14,15).

As the body's outermost barrier, the skin is

continuously exposed to environmental factors and serves as the

first line of immune defense (16). The skin microbiota consists of

microbial communities adapted to the cutaneous environment through

long-term colonization, persisting in the chemical milieu of the

stratum corneum, sweat and sebaceous secretions (17). Environmental factors such as

ultraviolet radiation, temperature, humidity, sebum levels, oxygen

availability and pH create distinct ecological niches across skin

regions, leading to spatial variation in microbial composition

(18). Based on physiological

characteristics, Mahmud et al (19) classified skin into sebaceous

(e.g., between eyebrows), moist (e.g., forearm flexure) and dry

(e.g., palmar forearm) types. Lipophilic bacteria dominate

sebum-rich areas, whereas dry regions may support a more diverse

microbiota (Fig. 1C).

The 'gut-skin axis' theory is part of the broader

'gut-organ axis' framework, emphasizing bidirectional communication

between the gut and other organs via neurological, endocrine and

immune pathways (23). This

theory integrates multiple organs, the gut and the immune system

with the gut microbiota (24).

The gut and skin share structural and functional similarities,

including embryonic origin, symbiotic microbial communities,

innervation patterns and immune functions (19). As internal and external surfaces

in contact with the environment, they utilize similar signaling and

innervation pathways. T-cell-mediated immune responses often

manifest in both intestinal and cutaneous tissues (25).

The gut microbial community is central to

maintaining gut-skin homeostasis and underpins the gut-skin axis

theory (26). The gut microbiota

includes bacteria, fungi, parasites, protozoa and viruses, with

bacteria predominating (27).

Over 90% of gut bacteria belong to the Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes

phyla (28). The

Bacteroidota-to-Firmicutes ratio is commonly used to assess gut

microbiota characteristics and diversity (29). Gut bacteria can be categorized as

beneficial (e.g., Bifidobacteria, Lactobacillus) or opportunistic

pathogens (e.g., Staphylococci, Clostridia), which may cause

infection under certain conditions (30).

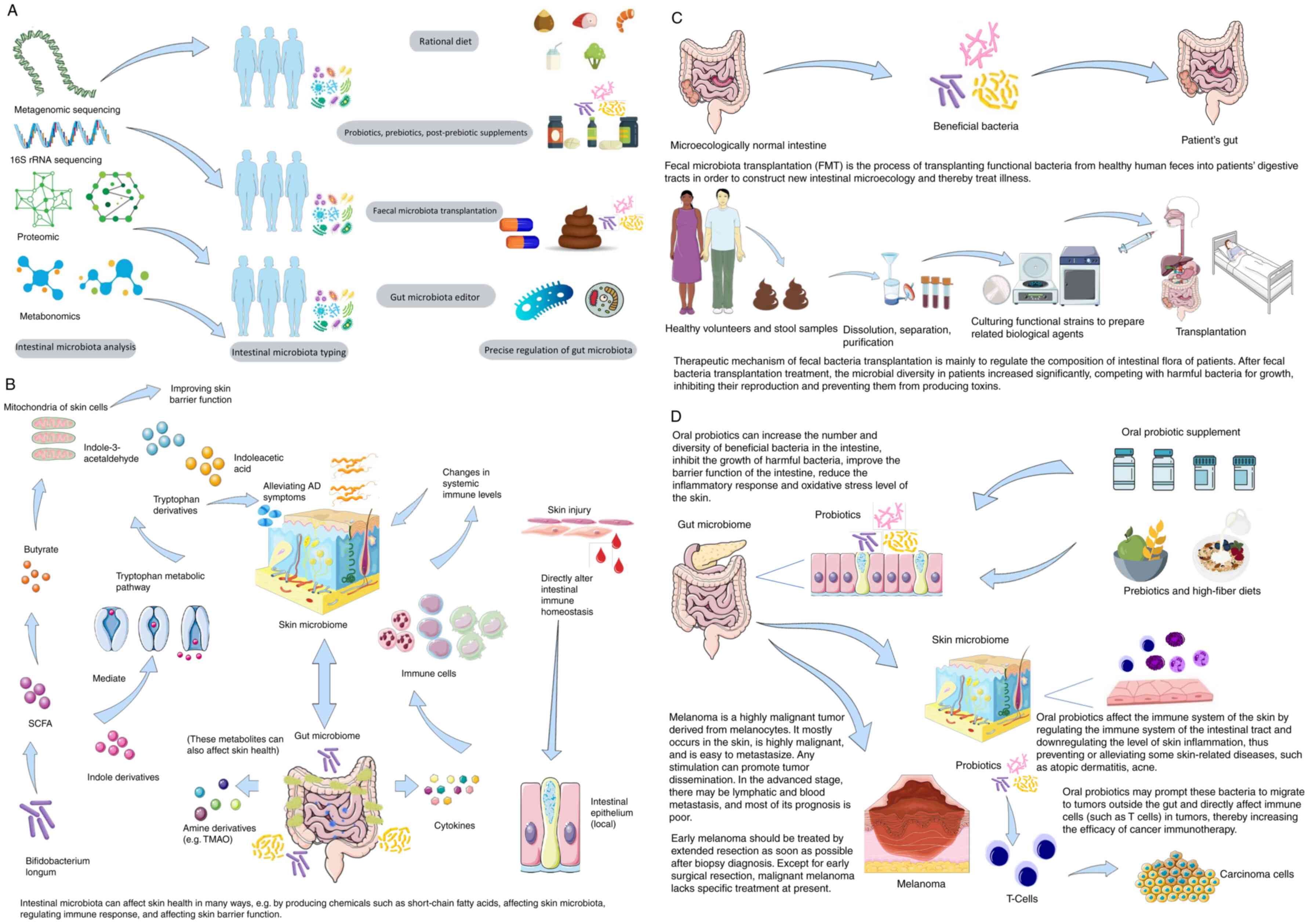

Alterations in gut microbiome composition,

metabolism and immunity can impact skin health. Manos (31) identified interspecies

communication within microbial communities as a key factor in

maintaining cutaneous homeostasis and responding to environmental

stressors, with dysregulation contributing to skin disease.

External factors such as genetics, diet, antimicrobials, and

lifestyle influence microbial diversity (32) (Fig. 2A).

Gut microbiota-derived metabolites mediate skin

interactions through short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), tryptophan

metabolites and amine derivatives (e.g., trimethylamine N-oxide),

which exert systemic effects via specific receptors (36). SCFAs play important roles in

immune regulation; Trompette et al (37) demonstrated that gut-derived

butyrate enhances skin barrier function by modifying mitochondrial

metabolism in keratinocytes. Fang et al (38) reported that Bifidobacterium

longum produces indole derivatives that alleviate AD via the

tryptophan pathway. Tryptophan metabolites (e.g., indoleacetic

acid) are critical for maintaining intestinal and systemic immune

homeostasis (39) (Fig. 2B).

Bidirectional interaction between the gut microbiome

and skin health is central to the gut-skin axis theory. While most

evidence highlights gut microbes influencing skin health, Dokoshi

et al (43) demonstrated

that skin injury directly remodels the gut microbiome (Fig. 2B), providing experimental support

for bidirectional signaling and indicating that skin damage may

impair gut immune homeostasis. Long et al (44), in a two-sample Mendelian

randomization study, established a causal relationship between gut

microbiota and four common inflammatory skin diseases: Eczema,

acne, psoriasis and rosacea.

Understanding gut microbiota-skin interactions

offers novel mechanistic insights for managing dermatological

conditions. Clinical evidence reveals frequent comorbidity of skin

and intestinal disorders, such as enteropathic acrodermatitis (zinc

malabsorption causing dermatitis, alopecia and diarrhea) (45), and celiac disease (associated

with eczema, psoriasis and urticaria) (46).

Restoring gut microbiota balance enhances intestinal

barrier integrity and regulates immune responses (47). This involves upregulating

immunomodulatory cytokines (e.g., IL-10) (48) and suppressing pro-inflammatory

mediators (e.g., TNF-α) (49).

Clinical interventions include probiotics, prebiotics, synbiotics

and fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) (50).

FMT involves transferring processed stool from

healthy donors to patients to rebuild gut microbiota. Initially

used for digestive diseases (51-53), FMT's efficacy depends on donor

and recipient factors (immune status, genetic diversity, gut

microbial composition) and treatment protocols (stool amount,

number of infusions, delivery route and adjuvant therapy) (54) (Fig. 2C).

While most FMT research focuses on gastrointestinal

disorders, recent trials suggest it may modulate systemic immune

responses, including in skin cancers like melanoma. Kim et

al (55) showed that FMT

improved AD symptoms in mice by restoring gut microbiota. FMT

enhances immunotherapy efficacy in cancer patients by modulating

gut microbiota (56). Melanoma,

the most common and prognostically worst skin cancer, is increasing

globally (57). Baruch et

al (58) observed that FMT

induced favorable changes in immune cell infiltration and gene

expression in intestinal and tumor microenvironments. Liu et

al (59) demonstrated that

FMT is effective for moderate to severe AD in adults, altering gut

microbiota composition and function. However, FMT carries risks;

Eshel et al (60) found

that while FMT capsules rarely transmit bloodstream pathogens

directly, they may indirectly promote bacterial translocation via

gut inflammation, potentially compromising intestinal barrier

integrity and increasing infection risk. Further in-depth studies

are required to ascertain the efficacy and safety of FMT in

treating other skin diseases.

Prebiotics are indigestible food components that

selectively stimulate beneficial bacteria (e.g.,

Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus) while inhibiting

pathogenic overgrowth, thereby improving intestinal microecology

(61). Probiotics are live

microorganisms that, when administered in adequate amounts, confer

health benefits through intestinal colonization (62). These interventions show promise

beyond gastrointestinal and cardiovascular diseases (63,64) with emerging applications in

dermatology.

In oncology, gut microbiome modulation may enhance

immunotherapy efficacy. Specific probiotics influence

T-cell-mediated therapies (e.g., anti-programmed cell death 1,

chimeric antigen receptor-T) (68), though strain-specific effects

require further validation. Bender et al (69) demonstrated that Lactobacillus

reuteri translocates to melanoma sites in mice, secreting

indole-3-aldehyde to activate CD8+ T-cell receptors and potentiate

immunotherapy. Such mechanisms hold potential for future

immunomodulatory strategies pending resolution of delivery

challenges and dose optimization.

Psoriasis is an immune-mediated skin disease

characterized by abnormal keratinocyte proliferation and

differentiation, posing significant physical and psychological

burdens (70). Previous studies

suggested gut microbiota dysbiosis in patients with psoriasis, but

the relationship remained vague (71). Zang et al (72) used bidirectional Mendelian

randomization to identify Pasteurellaceae, Brucella

and Methanobrevibacter smithii as potential pathogenic

contributors, suggesting microbial targets for therapy (Table I). Zhao et al (73) demonstrated through metabolomics

that gut microbiota transplantation from severely affected mice

exacerbated skin inflammation in mild cases, while a

phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor alleviated symptoms and restored the

gut microbiota, providing a theoretical basis for gut

microbiota-skin axis-based psoriasis treatment (Table I).

AD is a common chronic inflammatory skin disease

characterized by persistent itching and eczematous rash (74). It increases the risk of

comorbidities like food allergies, asthma, allergic rhinitis and

mental health disorders (75).

The pathogenesis involves hereditary immune dysregulation, skin

barrier dysfunction and environmental factors (76). The gut microbiota modulates

immune system development, implying a key role in AD (77).

First-line AD treatment includes topical

corticosteroids and calcineurin inhibitors (e.g., pimecrolimus,

tacrolimus). For moderate to severe cases, ultraviolet phototherapy

is used adjunctively (78).

Probiotic supplementation is increasingly used, particularly in

children, to modulate gut microbiota and regulate immune responses

(79,80). Meta-analyses indicate certain

probiotics reduce Scoring Atopic Dermatitis indices in adults

(81). Fang et al

(82) showed that

Bifidobacterium CCFM16 and Lactobacillus plantar

CCFM8610 specifically improve AD by altering gut microbiota

composition and function (Table

I).

AV is a chronic inflammatory skin disease affecting

sebaceous units, characterized by comedones, papules, pustules,

nodules and scars, typically on the face, upper trunk and

extremities (83). The global

prevalence is estimated at 8.96% in men and 9.81% in women

(84). The pathogenesis involves

multifactorial mechanisms, with pubertal sebum hypersecretion being

a key factor. AV often persists into adulthood with distinct

features (85). Androgens and

testosterone regulate sebum production, explaining why males often

experience more severe symptoms (86).

Gut dysbiosis may exacerbate AV through upregulated

insulin-like growth factor 1 signaling, insulin resistance and

systemic pro-inflammatory cytokines (87). First-line treatments include

topical retinoids, azelaic acid and benzoyl peroxide (88). The role of gut microbiota

modulation via probiotics in improving AV is underexplored. Jung

et al (89) found that

probiotic-antibiotic combination therapy synergistically reduced

inflammation and antibiotic side effects. Fabbrocini et al

(90) showed that

Lactobacillus rhamnosus SP1 (LSP1) probiotic normalized skin

insulin signaling gene expression. Eguren et al (91) conducted a 12-week trial with

Lactobacillus rhamnosus and Arthrospira in patients

with AV aged 12-30 years, finding the probiotic adjunct safe and

effective (Table I).

Rosacea is a chronic recurrent inflammatory skin

condition affecting the central face (forehead, nose, cheeks, chin)

(92). It is classified into

erythematotelangiectatic, papulopustular, phymatous and ocular

subtypes (93).

According to 2021 guidelines, urticaria is

classified as acute (lasting <6 weeks) or chronic urticaria

(CU). CU is a common inflammatory skin disorder involving mast

cell-mediated allergy and autoimmunity, characterized by recurrent

wheals, angioedema and itching lasting ≥6 weeks (99). Pathophysiology involves immune

dysregulation, inflammatory cascade imbalance and

coagulation-fibrinolytic activation (100). CU subtypes include chronic

spontaneous urticaria (CSU) and chronic inducible urticarial

(101).

Vitiligo is a depigmentation disorder affecting

0.5-2% globally, with a genetic component (106). It presents as white, scaleless

patches (107).

Pathophysiologically, vitiligo is an autoimmune condition where

melanocytes are sensitive to oxidative stress, triggering

inflammatory cytokine release and innate immune activation.

CD8+ T cells destroy melanocytes, driven by IFN-γ.

Oxidative stress may induce gut dysbiosis, promoting autoimmunity.

IFN-γ blockade therapies temporarily reverse depigmentation but

relapse occurs upon cessation (108). The chronic course of vitiligo

affects patients' appearance and psychological well-being;

Kussainova et al (109)

reported a 35.8% anxiety prevalence, higher in women.

Current evidence on the gut-vitiligo link is

limited. Emerging studies suggest gut microbiome involvement. Hadi

et al (110) reported

vitiligo-inflammatory bowel disease comorbidity. Ni et al

(111) documented a

Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio reduction in patients

with vitiligo (Table I), while

Luan et al (112)

observed decreased microbial alpha diversity with altered

cysteine/galactose metabolism (Table

I). These findings support the gut-microbiota-skin hypothesis

but require further investigation for therapeutic applications.

Skin cancer is the fifth most common cancer

globally, with its incidence rising (113). It arises from genetic defects

or DNA mutations in skin cells, primarily due to ultraviolet

exposure (114). Skin cancers

are classified as malignant melanoma (MM) or non-melanoma skin

cancer (NMSC). MM originates from melanocytes, while NMSC (e.g.,

squamous cell carcinoma, basal cell carcinoma) arises from

epidermal cells (115).

Treatments include cryotherapy, radiotherapy and photodynamic

therapy, but novel approaches are needed (116).

MM is highly metastatic, has a poor prognosis and is

the leading cause of death among patients with skin cancer

(117). Mrazek et al

(118) found compositional

differences between melanoma and healthy skin microbiomes, with

elevated Fusobacterium and Eubacterium in tumors

(Table I). Mekadim et al

(119) demonstrated distinct

gut and skin microbiome profiles in melanoma models, addressing

knowledge gaps (Table I).

Several studies confirmed that the gut microbiota

can modulate the response to cancer immune checkpoint blockade

therapy (120-122). Spencer et al (123) reported improved

progression-free survival in ICB-treated patients with higher fiber

intake, particularly without probiotics; fiber/prebiotics enhanced

antitumor T-cell responses via microbiome modulation (Table I). Routy et al (124)'s phase I trial confirmed FMT

safety combined with first-line melanoma therapy, though efficacy

requires further validation (Fig.

2D) (Table I). Future

investigations of the gut-skin axis may yield innovative

therapeutic strategies for skin cancer.

Rare dermatoses like AIBD and LP receive limited

research due to funding and recruitment challenges (125). AIBD involve chronic

immune-mediated blistering, with fragile cutaneous/mucosal vesicles

rupturing into erosions. These include pemphigus vulgaris (PV),

bullous pemphigoid (BP) and mucous membrane pemphigoid (126). PV subtypes include vulgaris,

foliaceus, IgA pemphigus and paraneoplastic pemphigus. BP, the most

common pemphigoid, features tense, rupture-resistant subepidermal

blisters, often involving the oropharyngeal and ocular mucosa. It

primarily affects adults aged >50 years but can also occur in

younger individuals (127).

Pemphigus has a long course and poor prognosis,

severely affecting patients' quality of life, with most deaths due

to uncontrollable secondary infections (128). The pathogenesis involves

Th1/Th2 and Th17/Treg imbalances, leading to IgG autoantibodies

that target epidermal/mucosal antigens, causing loss of cell

adhesion and blister formation (129).

LP is a chronic inflammatory disease presenting as

violaceous pruritic papules on skin, mucosa or nails. Subtypes

include cutaneous LP (CLP) and oral LP (OLP), with possible

esophageal, genital or nail involvement (132). The prevalence of LP ranges from

0.22 to 1%, with OLP about five times more common than CLP

(133). Genital subtypes have

been reported (134), and

concurrent subtypes complicate diagnosis (135). The pathogenesis of CLP involves

cell-mediated immune responses against basal keratinocytes

(136). Georgescu et al

(137) reported an

oxidant-antioxidant imbalance in patients with LP, suggesting

oxidative stress plays a role.

Few studies have focused on the role of the 'gut

microbe-skin axis' in rare skin diseases such as LP and pemphigus

(22). Li et al (138) observed a distinct gut

microbiota in patients with active pemphigus, with

Prevotella spp. and Coriobacteriaceae abundance

correlating with autoantibodies. Roy et al (139) reviewed intestinal

microecological dysregulation in several rare diseases, including

LP, and highlighted the complexity of host-microbiota interactions,

emphasizing knowledge gaps, the need for improved study designs,

and the promise of microbiome-based therapeutics. Kamal et

al (140)'s trial on 60

patients with OLP showed a greater reduction in pain and

Thongprasom scores with combined clobetasol/probiotic therapy vs.

clobetasol alone. Despite research challenges, such as scarce

pathogenic data and small cohorts, elucidating microbiota-skin

interactions could yield novel diagnostics and therapies for rare

dermatoses.

Despite progress, translating gut microbiome

research into clinical applications remains challenging.

Methodological limitations in data collection, representativeness

and analysis are key barriers. Resources like GMrepo (https://gmrepo.humangut.info/home) and gutMGene

(https://bio-computing.hrbmu.edu.cn/gutmgene/#/home)

provide valuable data, but heterogeneity due to geographic,

demographic and lifestyle factors complicates sampling and

standardization (Fig. 2A). The

lack of a consensus definition for 'healthy gut microbiota' impedes

benchmark establishment (141,142).

Patient and provider acceptance barriers persist,

especially in culturally conservative settings. Probiotics, though

generally safer than FMT, carry risks such as bacteremia in

immunocompromised hosts and horizontal gene transfer (152,153). Cases like Lactobacillus

rhamnosus infections in immunosuppressed individuals underscore

the need for further safety research (154-156).

Preclinical gut microbiome research will continue

diversifying. International data-sharing collaborations may

overcome ethnographic limitations (157). Integrating medicine, biology

and informatics could expand the research scope, as seen in machine

learning applications for microbial community analysis (158). Current algorithms predict

health status and identify disease-microbiome associations through

differential abundance analysis (159).

In clinical translation, precision medicine

requires refinement. Longitudinal studies with larger cohorts may

better evaluate probiotic efficacy across populations, informing

targeted microbiome-based interventions using adaptive trial

designs (e.g., cluster randomized controlled trials). These

frameworks would strengthen disease prevention and treatment

strategies.

Emerging technologies like high-intensity

ultrasound show potential for enhancing functional food development

by improving probiotic stability and bioactivity (160), Future validation studies should

assess gut health optimization and personalized approaches

(161,162). Beyond dairy probiotics,

fermented foods and beverages are demonstrating health benefits

(163,164).

The following conclusions can be drawn from the

present review: i) The gut-skin axis framework highlights the

influence of gut microbiota on skin homeostasis, with dysbiosis

implicated in psoriasis, AD, acne and AIBD; ii) the gut microbiota

modulates skin health through immune regulation, microbial

metabolite production (e.g., SCFAs) and systemic inflammation

control. FMT, probiotics and prebiotics show promise in restoring

microbial balance and reducing inflammation, though larger trials

are needed; iii) current evidence primarily establishes

correlations, but causal relationships require validation via

multi-omics approaches integrating genomics, metabolomics and

immune profiling; iv) clinical translation faces challenges

including methodological limitations, ethical concerns with FMT and

insufficient long-term safety data for probiotics; v) mechanistic

insights into rare skin diseases via the gut-skin axis are scarce,

warranting targeted investigations; vi) future research should

prioritize patient-specific microbiome interventions,

machine-learning diagnostics and cross-disciplinary collaboration

(e.g., dermatology-gastroenterology-bioinformatics) to advance

precision dermatology; and vii) the gut-skin axis redefines

skincare paradigms, emphasizing gut health as integral to

dermatological wellness, with breakthroughs in microbiome

engineering and Artificial Intelligence-driven interventions

offering transformative potential.

Not applicable.

YZ performed the analyses and wrote the first draft

of the manuscript. CY, JZ, QY, XZ and XZ performed the literature

search and discussed and edited the manuscript. XZ and XZ

supervised the preparation of the manuscript. Data authentication

is not applicable. All authors have read and approved the final

manuscript.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Not applicable.

This study was partially supported by the National Natural

Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 32170915 and 82172931).

|

1

|

Karimzadeh F, Soltani Fard E, Nadi A,

Malekzadeh R, Elahian F and Mirzaei SA: Advances in skin gene

therapy: Utilizing innovative dressing scaffolds for wound healing,

a comprehensive review. J Mater Chem B. 12:6033–6062. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Shi N, Li N, Duan X and Niu H: Interaction

between the gut microbiome and mucosal immune system. Mil Med Res.

4:142017.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Wang J, He M, Yang M and Ai X: Gut

microbiota as a key regulator of intestinal mucosal immunity. Life

Sci. 345:1226122024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Ezenabor EH, Adeyemi AA and Adeyemi OS:

Gut microbiota and metabolic syndrome: Relationships and

opportunities for new therapeutic strategies. Scientifica (Cairo).

2024:42220832024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Saarialho-Kere U: The gut-skin axis. J

Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 39(Suppl 3): S734–S735. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Lee HR and Sung JH: Multiorgan-on-a-chip

for the realization of gut-skin axis. Biotechnol Bioeng.

119:2590–2601. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Szanto M, Dozsa A, Antal D, Szabo K,

Kemeny L and Bai P: Targeting the gut-skin axis-Probiotics as new

tools for skin disorder management? Exp Dermatol. 28:1210–1218.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Suaini NHA, Siah KTH and Tham EH: Role of

the gut-skin axis in IgE-mediated food allergy and atopic diseases.

Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 37:557–564. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Alesa DI, Alshamrani HM, Alzahrani YA,

Alamssi DN, Alzahrani NS and Almohammadi ME: The role of gut

microbiome in the pathogenesis of psoriasis and the therapeutic

effects of probiotics. J Family Med Prim Care. 8:3496–3503. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Gomaa EZ: Human gut microbiota/microbiome

in health and diseases: A review. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek.

113:2019–2040. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Adak A and Khan MR: An insight into gut

microbiota and its functionalities. Cell Mol Life Sci. 76:473–493.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Zmora N, Suez J and Elinav E: You are what

you eat: Diet, health, and the gut microbiota. Nat Rev

Gastroenterol Hepatol. 16:35–56. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Milani C, Duranti S, Bottacini F, Casey E,

Turroni F, Mahony J, Belzer C, Delgado Palacio S, Arboleya Montes

S, Mancabelli L, et al: The first microbial colonizers of the human

gut: Composition, activities, and health implications of the infant

gut microbiota. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 81:e00036–17. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Aggarwal N, Kitano S, Puah GRY, Kittelmann

S, Hwang IY and Chang MW: Microbiome and human health: Current

understanding, engineering, and enabling technologies. Chem Rev.

123:31–72. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

15

|

Banaszak M, Gorna I, Wozniak D,

Przyslawski J and Drzymala-Czyz S: Association between gut

dysbiosis and the occurrence of SIBO, LIBO, SIFO and IMO.

Microorganisms. 11:5732023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Lee HJ and Kim M: Skin barrier function

and the microbiome. Int J Mol Sci. 23:130712022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Chen YE, Fischbach MA and Belkaid Y: Skin

microbiota-host interactions. Nature. 553:427–436. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Smythe P and Wilkinson HN: The skin

microbiome: Current landscape and future opportunities. Int J Mol

Sci. 24:39502023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Mahmud MR, Akter S, Tamanna SK, Mazumder

L, Esti IZ, Banerjee S, Akter S, Hasan MR, Acharjee M, Hossain MS

and Pirttilä AM: Impact of gut microbiome on skin health: Gut-skin

axis observed through the lenses of therapeutics and skin diseases.

Gut Microbes. 14:20969952022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Petersen C and Round JL: Defining

dysbiosis and its influence on host immunity and disease. Cell

Microbiol. 16:1024–1033. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Rygula I, Pikiewicz W, Grabarek BO, Wojcik

M and Kaminiow K: The role of the gut microbiome and microbial

dysbiosis in common skin diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 25:19842024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Karimova M, Moyes D, Ide M and Setterfield

JF: The human microbiome in immunobullous disorders and lichen

planus. Clin Exp Dermatol. 47:522–528. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Ahlawat S, Asha and Sharma KK: Gut-organ

axis: A microbial outreach and networking. Lett Appl Microbiol.

72:636–668. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Guo Y, Chen X, Gong P, Li G, Yao W and

Yang W: The gut-organ-axis concept: Advances the application of

gut-on-chip technology. Int J Mol Sci. 24:40892023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Yano JM, Yu K, Donaldson GP, Shastri GG,

Ann P, Ma L, Nagler CR, Ismagilov RF, Mazmanian SK and Hsiao EY:

Indigenous bacteria from the gut microbiota regulate host serotonin

biosynthesis. Cell. 161:264–276. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Salem I, Ramser A, Isham N and Ghannoum

MA: The gut microbiome as a major regulator of the gut-skin axis.

Front Microbiol. 9:14592018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Komine M: Recent advances in psoriasis

research; The clue to mysterious relation to gut microbiome. Int J

Mol Sci. 21:25822020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Buhas MC, Gavrilas LI, Candrea R, Catinean

A, Mocan A, Miere D and Tătaru A: Gut microbiota in psoriasis.

Nutrients. 14:29702022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Frioux C, Ansorge R, Ozkurt E, Ghassemi

Nedjad C, Fritscher J, Quince C, Waszak SM and Hildebrand F:

Enterosignatures define common bacterial guilds in the human gut

microbiome. Cell Host Microbe. 31:1111–1125 e6. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Quaglio AEV, Grillo TG, De Oliveira ECS,

Di Stasi LC and Sassaki LY: Gut microbiota, inflammatory bowel

disease, and colorectal cancer. World J Gastroenterol.

28:4053–4060. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Manos J: The human microbiome in disease

and pathology. APMIS. 130:690–705. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Wu J, Wang K, Wang X, Pang Y and Jiang C:

The role of the gut microbiome and its metabolites in metabolic

diseases. Protein Cell. 12:360–373. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

33

|

Chen Y, Zhou J and Wang L: Role and

mechanism of gut microbiota in human disease. Front Cell Infect

Microbiol. 11:6259132021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Olejniczak-Staruch I, Ciazynska M,

Sobolewska-Sztychny D, Narbutt J, Skibinska M and Lesiak A:

Alterations of the skin and gut microbiome in psoriasis and

psoriatic arthritis. Int J Mol Sci. 22:39982021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Park DH, Kim JW, Park HJ and Hahm DH:

Comparative analysis of the microbiome across the gut-skin axis in

atopic dermatitis. Int J Mol Sci. 22:42282021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Stec A, Sikora M, Maciejewska M,

Paralusz-Stec K, Michalska M, Sikorska E and Rudnicka L: Bacterial

metabolites: A link between gut microbiota and dermatological

diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 24:34942023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Trompette A, Pernot J, Perdijk O,

Alqahtani RAA, Domingo JS, Camacho-Munoz D, Wong NC, Kendall AC,

Wiederkehr A, Nicod LP, et al: Gut-derived short-chain fatty acids

modulate skin barrier integrity by promoting keratinocyte

metabolism and differentiation. Mucosal Immunol. 15:908–926. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Fang Z, Pan T, Li L, Wang H, Zhu J, Zhang

H, Zhao J, Chen W and Lu W: Bifidobacterium longum mediated

tryptophan metabolism to improve atopic dermatitis via the gut-skin

axis. Gut Microbes. 14:20447232022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Su X, Gao Y and Yang R: Gut

microbiota-derived tryptophan metabolites maintain gut and systemic

homeostasis. Cells. 11:22962022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Kinashi Y and Hase K: Partners in leaky

gut syndrome: intestinal dysbiosis and autoimmunity. Front Immunol.

12:6737082021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Marrs T, Jo JH, Perkin MR, Rivett DW,

Witney AA, Bruce KD, Logan K, Craven J, Radulovic S, Versteeg SA,

et al: Gut microbiota development during infancy: Impact of

introducing allergenic foods. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 147:613–621

e9. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Jiao Y, Wu L, Huntington ND and Zhang X:

Crosstalk between gut microbiota and innate immunity and its

implication in autoimmune diseases. Front Immunol. 11:2822020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Dokoshi T, Chen Y, Cavagnero KJ, Rahman G,

Hakim D, Brinton S, Schwarz H, Brown EA, O'Neill A, Nakamura Y, et

al: Dermal injury drives a skin-to-gut axis that disrupts the

intestinal microbiome and intestinal immune homeostasis in mice.

Nat Commun. 15:30092024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Long J, Gu J, Yang J, Chen P, Dai Y, Lin

Y, Wu M and Wu Y: Exploring the association between gut microbiota

and inflammatory skin diseases: A two-sample mendelian

randomization analysis. Microorganisms. 11:25862023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Glutsch V, Hamm H and Goebeler M: Zinc and

skin: An update. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 17:589–596. 2019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Therrien A, Kelly CP and Silvester JA:

Celiac disease: Extraintestinal manifestations and associated

conditions. J Clin Gastroenterol. 54:8–21. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Ni Q, Zhang P, Li Q and Han Z: Oxidative

stress and gut microbiome in inflammatory skin diseases. Front Cell

Dev Biol. 10:8499852022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Lee SY, Jhun J, Woo JS, Lee KH, Hwang SH,

Moon J, Park G, Choi SS, Kim SJ, Jung YJ, et al: Gut

microbiome-derived butyrate inhibits the immunosuppressive factors

PD-L1 and IL-10 in tumor-associated macrophages in gastric cancer.

Gut Microbes. 16:23008462024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Xiao P, Hu Z, Lang J, Pan T, Mertens RT,

Zhang H, Guo K, Shen M, Cheng H, Zhang X, et al: Mannose metabolism

normalizes gut homeostasis by blocking the TNF-α-mediated

proinflammatory circuit. Cell Mol Immunol. 20:119–130. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Yadegar A, Bar-Yoseph H, Monaghan TM,

Pakpour S, Severino A, Kuijper EJ, Smits WK, Terveer EM, Neupane S,

Nabavi-Rad A, et al: Fecal microbiota transplantation: current

challenges and future landscapes. Clin Microbiol Rev.

37:e00060222024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Joachim A, Schwerd T, Holz H, Sokollik C,

Konrad LA, Jordan A, Lanzersdorfer R, Schmidt-Choudhury A, Hünseler

C and Adam R: Fecal Microbiota Transfer (FMT) in children and

adolescents-review and statement by the GPGE microbiome working

group. Z Gastroenterol. 60:963–969. 2022.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Porcari S, Severino A, Rondinella D, Bibbo

S, Quaranta G, Masucci L, Maida M, Scaldaferri F, Sanguinetti M,

Gasbarrini A, et al: Fecal microbiota transplantation for recurrent

Clostridioides difficile infection in patients with concurrent

ulcerative colitis. J Autoimmun. 141:1030332023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Porcari S, Baunwall SMD, Occhionero AS,

Ingrosso MR, Ford AC, Hvas CL, Gasbarrini A, Cammarota G and Ianiro

G: Fecal microbiota transplantation for recurrent C. difficile

infection in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: A systematic

review and meta-analysis. J Autoimmun. 141:1030362023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Porcari S, Benech N, Valles-Colomer M,

Segata N, Gasbarrini A, Cammarota G, Sokol H and Ianiro G: Key

determinants of success in fecal microbiota transplantation: From

microbiome to clinic. Cell Host Microbe. 31:712–733. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Kim JH, Kim K and Kim W: Gut microbiota

restoration through fecal microbiota transplantation: A new atopic

dermatitis therapy. Exp Mol Med. 53:907–916. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Liu YH, Chen J, Chen X and Liu H: Factors

of faecal microbiota transplantation applied to cancer management.

J Drug Target. 32:101–114. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Arnold M, Singh D, Laversanne M, Vignat J,

Vaccarella S, Meheus F, Cust AE, de Vries E, Whiteman DC and Bray

F: Global burden of cutaneous melanoma in 2020 and projections to

2040. JAMA Dermatol. 158:495–503. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Baruch EN, Youngster I, Ben-Betzalel G,

Ortenberg R, Lahat A, Katz L, Adler K, Dick-Necula D, Raskin S,

Bloch N, et al: Fecal microbiota transplant promotes response in

immunotherapy-refractory melanoma patients. Science. 371:602–609.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

59

|

Liu X, Luo Y, Chen X, Wu M, Xu X, Tian J,

Gao Y, Zhu J, Wang Z, Zhou Y, et al: Fecal microbiota

transplantation against moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: A

randomized, double-blind controlled exploratory trial. Allergy.

80:1377–1388. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

60

|

Eshel A, Sharon I, Nagler A, Bomze D,

Danylesko I, Fein JA, Geva M, Henig I, Shimoni A, Zuckerman T, et

al: Origins of bloodstream infections following fecal microbiota

transplantation: A strain-level analysis. Blood Adv. 6:568–573.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

61

|

Gibson GR and Roberfroid MB: Dietary

modulation of the human colonic microbiota: Introducing the concept

of prebiotics. J Nutr. 125:1401–1412. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Hill C, Guarner F, Reid G, Gibson GR,

Merenstein DJ, Pot B, Morelli L, Canani RB, Flint HJ, Salminen S,

et al: Expert consensus document. The International Scientific

Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics consensus statement on

the scope and appropriate use of the term probiotic. Nat Rev

Gastroenterol Hepatol. 11:506–514. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Manzoor S, Wani SM, Ahmad Mir S and Rizwan

D: Role of probiotics and prebiotics in mitigation of different

diseases. Nutrition. 96:1116022022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Oniszczuk A, Oniszczuk T, Gancarz M and

Szymanska J: Role of gut microbiota, probiotics and prebiotics in

the cardiovascular diseases. Molecules. 26:11722021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Rahmayani T, Putra IB and Jusuf NK: The

effect of oral probiotics on the interleukin-10 serum levels of

acne vulgaris. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 7:3249–5322. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

66

|

Ouyang W and O'Garra A: IL-10 family

cytokines IL-10 and IL-22: From basic science to clinical

translation. Immunity. 50:871–891. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Buhas MC, Candrea R, Gavrilas LI, Miere D,

Tataru A, Boca A and Cătinean A: Transforming psoriasis care:

Probiotics and prebiotics as novel therapeutic approaches. Int J

Mol Sci. 24:112252023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Stein-Thoeringer CK, Saini NY, Zamir E,

Blumenberg V, Schubert ML, Mor U, Fante MA, Schmidt S, Hayase E,

Hayase T, et al: A non-antibiotic-disrupted gut microbiome is

associated with clinical responses to CD19-CAR-T cell cancer

immunotherapy. Nat Med. 29:906–916. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Bender MJ, McPherson AC, Phelps CM, Pandey

SP, Laughlin CR, Shapira JH, Medina Sanchez L, Rana M, Richie TG,

Mims TS, et al: Dietary tryptophan metabolite released by

intratumoral Lactobacillus reuteri facilitates immune checkpoint

inhibitor treatment. Cell. 186:1846–1862 e26. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Raharja A, Mahil SK and Barker JN:

Psoriasis: A brief overview. Clin Med (Lond). 21:170–173. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Hidalgo-Cantabrana C, Gomez J, Delgado S,

Requena-Lopez S, Queiro-Silva R, Margolles A, Coto E, Sánchez B and

Coto-Segura P: Gut microbiota dysbiosis in a cohort of patients

with psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 181:1287–1295. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Zang C, Liu J, Mao M, Zhu W, Chen W and

Wei B: Causal associations between gut microbiota and psoriasis: A

mendelian randomization study. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb).

13:2331–2343. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Zhao Q, Yu J, Zhou H, Wang X, Zhang C, Hu

J, Hu Y, Zheng H, Zeng F, Yue C, et al: Intestinal dysbiosis

exacerbates the pathogenesis of psoriasis-like phenotype through

changes in fatty acid metabolism. Signal Transduct Target Ther.

8:402023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Sroka-Tomaszewska J and Trzeciak M:

Molecular mechanisms of atopic dermatitis pathogenesis. Int J Mol

Sci. 22:41302021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Langan SM, Irvine AD and Weidinger S:

Atopic dermatitis. Lancet. 396:345–360. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Schuler CF IV, Tsoi LC, Billi AC, Harms

PW, Weidinger S and Gudjonsson JE: Genetic and immunological

pathogenesis of atopic dermatitis. J Invest Dermatol. 144:954–968.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

77

|

Lee SY, Lee E, Park YM and Hong SJ:

Microbiome in the gut-skin axis in atopic dermatitis. Allergy

Asthma Immunol Res. 10:354–362. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Frazier W and Bhardwaj N: Atopic

dermatitis: Diagnosis and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 101:590–598.

2020.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Jiang W, Ni B, Liu Z, Liu X, Xie W, Wu IXY

and Li X: The role of probiotics in the prevention and treatment of

atopic dermatitis in children: An updated systematic review and

meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Paediatr Drugs.

22:535–549. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

D'Elios S, Trambusti I, Verduci E,

Ferrante G, Rosati S, Marseglia GL, Drago L and Peroni DG:

Probiotics in the prevention and treatment of atopic dermatitis.

Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 31(Suppl 26): S43–S45. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

81

|

Umborowati MA, Damayanti D, Anggraeni S,

Endaryanto A, Surono IS, Effendy I and Prakoeswa CRS: The role of

probiotics in the treatment of adult atopic dermatitis: A

meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Health Popul Nutr.

41:372022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Fang Z, Lu W, Zhao J, Zhang H, Qian L,

Wang Q and Chen W: Probiotics modulate the gut microbiota

composition and immune responses in patients with atopic

dermatitis: A pilot study. Eur J Nutr. 59:2119–2130. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

83

|

Sanchez-Pellicer P, Navarro-Moratalla L,

Nunez-Delegido E, Ruzafa-Costas B, Aguera-Santos J and

Navarro-Lopez V: Acne, microbiome, and probiotics: The gut-skin

axis. Microorganisms. 10:13032022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Vos T, Flaxman AD, Naghavi M, Lozano R,

Michaud C, Ezzati M, Shibuya K, Salomon JA, Abdalla S, Aboyans V,

et al: Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289

diseases and injuries, 1990-2010: A systematic analysis for the

Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 380:2163–2196. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Kutlu O, Karadag AS and Wollina U: Adult

acne versus adolescent acne: A narrative review with a focus on

epidemiology to treatment. An Bras Dermatol. 98:75–83. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

86

|

Chilicka K, Rogowska AM, Szygula R,

Dziendziora-Urbinska I and Taradaj J: A comparison of the

effectiveness of azelaic and pyruvic acid peels in the treatment of

female adult acne: A randomized controlled trial. Sci Rep.

10:126122020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

Bowe W, Patel NB and Logan AC: Acne

vulgaris, probiotics, and the gut-brain-skin axis: From anecdote to

translational medicine. Beneficial Microbes. 5:185–199. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

88

|

Mohsin N, Hernandez LE, Martin MR, Does AV

and Nouri K: Acne treatment review and future perspectives.

Dermatol Ther. 35:e157192022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

89

|

Jung GW, Tse JE, Guiha I and Rao J:

Prospective, randomized, open-label trial comparing the safety,

efficacy, and tolerability of an acne treatment regimen with and

without a probiotic supplement and minocycline in subjects with

mild to moderate acne. J Cutan Med Surg. 17:114–122. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

90

|

Fabbrocini G, Bertona M, Picazo O,

Pareja-Galeano H, Monfrecola G and Emanuele E: Supplementation with

Lactobacillus rhamnosus SP1 normalises skin expression of genes

implicated in insulin signalling and improves adult acne. Benef

Microbes. 7:625–630. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

91

|

Eguren C, Navarro-Blasco A, Corral-Forteza

M, Reolid-Perez A, Seto-Torrent N, Garcia-Navarro A, Prieto-Merino

D, Núñez-Delegido E, Sánchez-Pellicer P and Navarro-López V: A

randomized clinical trial to evaluate the efficacy of an oral

probiotic in acne vulgaris. Acta Derm Venereol. 104:adv332062024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

92

|

van Zuuren EJ, Arents BWM, van der Linden

MMD, Vermeulen S, Fedorowicz Z and Tan J: Rosacea: New concepts in

classification and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 22:457–465. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

93

|

Ivanic MG, Oulee A, Norden A, Javadi SS,

Gold MH and Wu JJ: Neurogenic rosacea treatment: A literature

review. J Drugs Dermatol. 22:566–575. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

94

|

Haber R and El Gemayel M: Comorbidities in

rosacea: A systematic review and update. J Am Acad Dermatol.

78:786–792 e8. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

95

|

Jun YK, Yu DA, Han YM, Lee SR, Koh SJ and

Park H: The relationship between rosacea and inflammatory bowel

disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Dermatol Ther

(Heidelb). 13:1465–1475. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

96

|

Li M, He SX, He YX, Hu XH and Zhou Z:

Detecting potential causal relationship between inflammatory bowel

disease and rosacea using bi-directional Mendelian randomization.

Sci Rep. 13:149102023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

97

|

Manzhalii E, Hornuss D and Stremmel W:

Intestinal-borne dermatoses significantly improved by oral

application of Escherichia coli Nissle 1917. World J Gastroenterol.

22:5415–5421. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

98

|

Fortuna MC, Garelli V, Pranteda G,

Romaniello F, Cardone M, Carlesimo M and Rossi A: A case of scalp

rosacea treated with low-dose doxycycline and probiotic therapy and

literature review on therapeutic options. Dermatol Ther.

29:249–251. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

99

|

Zuberbier T, Abdul Latiff AH, Abuzakouk M,

Aquilina S, Asero R, Baker D, Ballmer-Weber B, Bangert C,

Ben-Shoshan M, Bernstein JA, et al: The international

EAACI/GA(2)LEN/EuroGuiDerm/APAAACI guideline for the definition,

classification, diagnosis, and management of urticaria. Allergy.

77:734–766. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

100

|

Kaplan A, Lebwohl M, Gimenez-Arnau AM,

Hide M, Armstrong AW and Maurer M: Chronic spontaneous urticaria:

Focus on pathophysiology to unlock treatment advances. Allergy.

78:389–401. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

101

|

Kolkhir P, Gimenez-Arnau AM, Kulthanan K,

Peter J, Metz M and Maurer M: Urticaria. Nat Rev Dis Primers.

8:612022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

102

|

Wang D, Guo S, He H, Gong L and Cui H: Gut

microbiome and serum metabolome analyses identify unsaturated fatty

acids and butanoate metabolism induced by gut microbiota in

patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria. Front Cell Infect

Microbiol. 10:242020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

103

|

Luo Z, Jin Z, Tao X, Wang T, Wei P, Zhu C

and Wang Z: Combined microbiome and metabolome analysis of gut

microbiota and metabolite interactions in chronic spontaneous

urticaria. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 12:10947372023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

104

|

Fu HY, Yu HD, Bai YP, Yue LF, Wang HM and

Li LL: Effect and safety of probiotics for treating urticaria: A

systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cosmet Dermatol.

22:2663–2670. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

105

|

Bi XD, Lu BZ, Pan XX, Liu S and Wang JY:

Adjunct therapy with probiotics for chronic urticaria in children:

Randomised placebo-controlled trial. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol.

17:392021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

106

|

Spritz RA and Santorico SA: The genetic

basis of vitiligo. J Invest Dermatol. 141:265–273. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

107

|

Bergqvist C and Ezzedine K: Vitiligo: A

review. Dermatology. 236:571–592. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

108

|

Frisoli ML, Essien K and Harris JE:

Vitiligo: Mechanisms of pathogenesis and treatment. Annu Rev

Immunol. 38:621–648. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

109

|

Kussainova A, Kassym L, Akhmetova A,

Glushkova N, Sabirov U, Adilgozhina S, Tuleutayeva R and Semenova

Y: Vitiligo and anxiety: A systematic review and meta-analysis.

PLoS One. 15:e02414452020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

110

|

Hadi A, Wang JF, Uppal P, Penn LA and

Elbuluk N: Comorbid diseases of vitiligo: A 10-year cross-sectional

retrospective study of an urban US population. J Am Acad Dermatol.

82:628–633. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

111

|

Ni Q, Ye Z, Wang Y, Chen J, Zhang W, Ma C,

Li K, Liu Y, Liu L, Han Z, et al: Gut microbial dysbiosis and

plasma metabolic profile in individuals with vitiligo. Front

Microbiol. 11:5922482020. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

112

|

Luan M, Niu M, Yang P, Han D, Zhang Y, Li

W, He Q, Zhao Y, Mao B, Chen J, et al: Metagenomic sequencing

reveals altered gut microbial compositions and gene functions in

patients with non-segmental vitiligo. BMC Microbiol. 23:2652023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

113

|

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Wagle NS and Jemal

A: Cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J Clin. 73:17–48.

2023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

114

|

Arivazhagan N, Mukunthan MA,

Sundaranarayana D, Shankar A, Vinoth Kumar S, Kesavan R,

Chandrasekaran S, Shyamala Devi M, Maithili K, Barakkath Nisha U

and Abebe TG: Analysis of skin cancer and patient healthcare using

data mining techniques. Comput Intell Neurosci. 2022:22502752022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

115

|

Hasan N, Nadaf A, Imran M, Jiba U, Sheikh

A, Almalki WH, Almujri SS, Mohammed YH, Kesharwani P and Ahmad FJ:

Skin cancer: Understanding the journey of transformation from

conventional to advanced treatment approaches. Mol Cancer.

22:1682023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

116

|

Jindal M, Kaur M, Nagpal M, Singh M,

Aggarwal G and Dhingra GA: Skin cancer management: Current scenario

and future perspectives. Curr Drug Saf. 18:143–158. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

117

|

Abbas O, Miller DD and Bhawan J: Cutaneous

malignant melanoma: Update on diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers.

Am J Dermatopathol. 36:363–379. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

118

|

Mrazek J, Mekadim C, Kucerova P, Svejstil

R, Salmonova H, Vlasakova J, Tarasová R, Čížková J and Červinková

M: Melanoma-related changes in skin microbiome. Folia Microbiol

(Praha). 64:435–442. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

119

|

Mekadim C, Skalnikova HK, Cizkova J,

Cizkova V, Palanova A, Horak V and Mrazek J: Dysbiosis of skin

microbiome and gut microbiome in melanoma progression. BMC

Microbiol. 22:632022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

120

|

Jia D, Wang Q, Qi Y, Jiang Y, He J, Lin Y,

Sun Y, Xu J, Chen W, Fan L, et al: Microbial metabolite enhances

immunotherapy efficacy by modulating T cell stemness in pan-cancer.

Cell. 187:1651–1665 e21. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

121

|

Zhou CB, Zhou YL and Fang JY: Gut

microbiota in cancer immune response and immunotherapy. Trends

Cancer. 7:647–660. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

122

|

Andrews MC, Duong CPM, Gopalakrishnan V,

Iebba V, Chen WS, Derosa L, Khan MAW, Cogdill AP, White MG, Wong

MC, et al: Gut microbiota signatures are associated with toxicity

to combined CTLA-4 and PD-1 blockade. Nat Med. 27:1432–1441. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

123

|

Spencer CN, McQuade JL, Gopalakrishnan V,

McCulloch JA, Vetizou M, Cogdill AP, Khan MAW, Zhang X, White MG,

Peterson CB, et al: Dietary fiber and probiotics influence the gut

microbiome and melanoma immunotherapy response. Science.

374:1632–1640. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

124

|

Routy B, Lenehan JG, Miller WH Jr, Jamal

R, Messaoudene M, Daisley BA, Hes C, Al KF, Martinez-Gili L,

Punčochář M, et al: Author correction: Fecal microbiota

transplantation plus anti-PD-1 immunotherapy in advanced melanoma:

A phase I trial. Nat Med. 30:6042024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

125

|

Ingram J: Editor's choice: Rare skin

diseases themed issue. Br J Dermatol. 182:ix2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

126

|

Buonavoglia A, Leone P, Dammacco R, Di

Lernia G, Petruzzi M, Bonamonte D, Vacca A, Racanelli V and

Dammacco F: Pemphigus and mucous membrane pemphigoid: An update

from diagnosis to therapy. Autoimmun Rev. 18:349–358. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

127

|

Malik AM, Tupchong S, Huang S, Are A, Hsu

S and Otaparthi K: An updated review of pemphigus diseases.

Medicina (Kaunas). 57:10802021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

128

|

Kridin K: Pemphigus group: overview,

epidemiology, mortality, and comorbidities. Immunol Res.

66:255–270. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

129

|

Yamagami J: B-cell targeted therapy of

pemphigus. J Dermatol. 50:124–131. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

130

|

Huang S, Mao J, Zhou L, Xiong X and Deng

Y: The imbalance of gut microbiota and its correlation with plasma

inflammatory cytokines in pemphigus vulgaris patients. Scand J

Immunol. 90:e127992019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

131

|

Han Z, Fan Y, Wu Q, Guo F, Li S, Hu X and

Zuo YG: Comparison of gut microbiota dysbiosis between pemphigus

vulgaris and bullous pemphigoid. Int Immunopharmacol.

128:1114702024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

132

|

Ioannides D, Vakirlis E, Kemeny L,

Marinovic B, Massone C, Murphy R, Nast A, Ronnevig J, Ruzicka T,

Cooper SM, et al: European S1 guidelines on the management of

lichen planus: A cooperation of the European Dermatology Forum with

the European academy of dermatology and venereology. J Eur Acad

Dermatol Venereol. 34:1403–1414. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

133

|

Chen K, Qin Y, Yan L, Dong Y, Lv S, Xu J,

Kang N, Luo Z, Liu Y, Pu J, et al: Variations in salivary

microbiota and metabolic phenotype related to oral lichen planus

with psychiatric symptoms. BMC Oral Health. 25:9932025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

134

|

Jacques L, Kornik R, Bennett DD and

Eschenbach DA: Diagnosis and management of vulvovaginal lichen

planus. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 75:624–635. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

135

|

van Hees CLM and van der Meij EH: Lichen

planus. Ned Tijdschr Tandheelkd. 130:221–226. 2023.In Dutch.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

136

|

Husein-ElAhmed H, Gieler U and Steinhoff

M: Lichen planus: A comprehensive evidence-based analysis of

medical treatment. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 33:1847–1862.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

137

|

Georgescu SR, Mitran CI, Mitran MI,

Nicolae I, Matei C, Ene CD, Popa GL and Tampa M: Oxidative stress

in cutaneous lichen planus narrative review. J Clin Med.

10:26922021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

138

|

Li SZ, Wu QY, Fan Y, Guo F, Hu XM and Zuo

YG: Gut microbiome dysbiosis in patients with pemphigus and

correlation with pathogenic autoantibodies. Biomolecules.

14:8802024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

139

|

Roy S, Nag S, Saini A and Choudhury L:

Association of human gut microbiota with rare diseases: A close

peek through. Intractable Rare Dis Res. 11:52–62. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

140

|

Kamal Y, Abdelwhab A, Salem ST and Fakhr

M: Evaluation of the efficacy of supplementary probiotic capsules

with topical clobetasol propionate 0.05% versus topical clobetasol

propionate 0.05% in the treatment of oral lichen planus (a

randomized clinical trial). BMC Oral Health. 25:3442025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

141

|

Shanahan F, Ghosh TS and O'Toole PW: The

healthy microbiome-what is the definition of a healthy gut

microbiome? Gastroenterology. 160:483–494. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

142

|

Shalon D, Culver RN, Grembi JA, Folz J,

Treit PV, Shi H, Rosenberger FA, Dethlefsen L, Meng X, Yaffe E, et

al: Profiling the human intestinal environment under physiological

conditions. Nature. 617:581–591. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

143

|

Schmidt TSB, Raes J and Bork P: The human

gut microbiome: From association to modulation. Cell.

172:1198–1215. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

144

|

McCallum G and Tropini C: The gut

microbiota and its biogeography. Nat Rev Microbiol. 22:105–118.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

145

|

Wang J and Jia H: Metagenome-wide

association studies: fine-mining the microbiome. Nat Rev Microbiol.

14:508–522. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

146

|

Uitterlinden AG: An introduction to

genome-wide association studies: GWAS for dummies. Semin Reprod

Med. 34:196–204. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

147

|

Li L, Yang S, Li R, Su J, Zhou X, Zhu X

and Gao R: Unraveling shared and unique genetic causal relationship

between gut microbiota and four types of uterine-related diseases:

Bidirectional mendelian inheritance approaches to dissect the

'gut-uterus axis'. Ann Epidemiol. 100:16–26. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

148

|

Asnicar F, Thomas AM, Passerini A, Waldron

L and Segata N: Machine learning for microbiologists. Nat Rev

Microbiol. 22:191–205. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

149

|

Ma J, Fang Y, Li S, Zeng L, Chen S, Li Z,

Ji G, Yang X and Wu W: Interpretable machine learning algorithms

reveal gut microbiome features associated with atopic dermatitis.

Front Immunol. 16:15280462025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

150

|

Al-Bakri AG, Akour AA and Al-Delaimy WK:

Knowledge, attitudes, ethical and social perspectives towards fecal

microbiota transplantation (FMT) among Jordanian healthcare

providers. BMC Med Ethics. 22:192021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

151

|

Benech N, Barbut F, Fitzpatrick F, Krutova

M, Davies K, Druart C, Cordaillat-Simmons M, Heritage J, Guery B

and Kuijper E; ESGCD and ESGHAMI: Update on microbiota-derived

therapies for recurrent Clostridioides difficile infections. Clin

Microbiol Infect. 30:462–468. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

152

|

Sada RM, Matsuo H, Motooka D, Kutsuna S,

Hamaguchi S, Yamamoto G and Ueda A: Clostridium butyricum

Bacteremia associated with probiotic use, Japan. Emerg Infect Dis.

30:665–671. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

153

|

Zawistowska-Rojek A and Tyski S: Are

probiotics safe for humans? Pol J Microbiol. 67:251–258. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

154

|

Gouriet F, Million M, Henri M, Fournier PE

and Raoult D: Lactobacillus rhamnosus bacteremia: An emerging

clinical entity. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 31:2469–2480.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

155

|

Harty DW, Oakey HJ, Patrikakis M, Hume EB

and Knox KW: Pathogenic potential of lactobacilli. Int J Food

Microbiol. 24:179–189. 1994. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

156

|

Bartalesi F, Veloci S, Baragli F,

Mantengoli E, Guidi S, Bartolesi AM, Mannino R, Pecile P and

Bartoloni A: Successful tigecycline lock therapy in a Lactobacillus

rhamnosus catheter-related bloodstream infection. Infection.

40:331–334. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

157

|

Jin DM, Morton JT and Bonneau R:

Meta-analysis of the human gut microbiome uncovers shared and

distinct microbial signatures between diseases. mSystems.

9:e00295242024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

158

|

Camacho DM, Collins KM, Powers RK,

Costello JC and Collins JJ: Next-generation machine learning for

biological networks. Cell. 173:1581–1592. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

159

|

Su Q, Liu Q, Lau RI, Zhang J, Xu Z, Yeoh

YK, Leung TWH, Tang W, Zhang L, Liang JQY, et al: Faecal

microbiome-based machine learning for multi-class disease

diagnosis. Nat Commun. 13:68182022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

160

|

Chuang YF, Fan KC, Su YY, Wu MF, Chiu YL,

Liu YC and Lin CC: Precision probiotics supplement strategy in an

aging population based on gut microbiome composition. Brief

Bioinform. 25:bbae3512024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

161

|

Guimaraes JT, Balthazar CF, Scudino H,

Pimentel TC, Esmerino EA, Ashokkumar M, Freitas MQ and Cruz AG:

High-intensity ultrasound: A novel technology for the development

of probiotic and prebiotic dairy products. Ultrason Sonochem.

57:12–21. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

162

|

Balthazar CF, Guimaraes JF, Coutinho NM,

Pimentel TC, Ranadheera CS, Santillo A, Albenzio M, Cruz AG and

Sant'Ana AS: The future of functional food: Emerging technologies

application on prebiotics, probiotics, and postbiotics. Compr Rev

Food Sci Food Saf. 21:2560–2586. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

163

|

Kucukgoz K and Trzaskowska M: Nondairy

probiotic products: Functional foods that require more attention.

Nutrients. 14:7532022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

164

|

Shumye Gebre T, Admassu Emire S, Okomo

Aloo S, Chelliah R, Vijayalakshmi S and Hwan Oh D: Unveiling the

potential of African fermented cereal-based beverages: Probiotics,

functional drinks, health benefits and bioactive components. Food

Res Int. 191:1146562024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|