Introduction

Perimenopause marks a key transitional phase from

reproductive maturity to menopause, characterized by the

progressive decline in ovarian function and reproductive capacity

(1). It typically begins with

noticeable menstrual irregularities and concludes 12 months after

the final menstruation, most commonly occurring between the ages of

40 and 55, although it may start as early as the mid-30s in some

women (2). A hallmark hormonal

change during perimenopause is the gradual decline and fluctuation

of ovarian hormones, particularly estrogen (E2) and progesterone

(3). This hormonal imbalance not

only disrupts the menstrual cycle and ultimately leads to its

cessation but also triggers a range of multisystem symptoms,

including vasomotor disturbances (such as hot flashes and night

sweats), mastalgia, musculoskeletal pain, vaginal dryness, fatigue

and neuropsychiatric symptoms such as anxiety, depression and

cognitive impairment (4-7).

Perimenopausal mood disorders are common yet often

underdiagnosed, exerting notable negative effects on occupational

performance, interpersonal relationships and overall social

functioning (8). Evidence

suggests that these mood disturbances not only reduce quality of

life but also contribute to the development of somatic

comorbidities through dysregulation of the stress axis, endocrine

instability and immune dysfunction (9,10). Current therapeutic options

include psychotherapy (such as cognitive behavioral therapy),

pharmacotherapy (such as antidepressants and anxiolytics) and

hormone replacement therapy (HRT). However, the considerable

variability in individual responses to treatment highlights the

complex and heterogeneous nature of the underlying pathophysiology

(11,12). Understanding the biological

mechanisms of perimenopausal mood disorders is therefore important

to advancing personalized treatment strategies.

Among the emerging mechanisms, mitochondrial

dysfunction has been identified as a central pathological

contributor. Mitochondria are vital organelles responsible for ATP

production and are integral in regulating oxidative stress, calcium

homeostasis, apoptosis and synaptic plasticity (13,14). Increasing evidence has associated

impaired mitochondrial function with various affective disorders,

including major depressive disorder, anxiety and stress-related

conditions (15-17). Disruptions in mitochondrial

homeostasis, characterized by impaired bioenergetics, excessive

reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation and heightened

inflammatory signaling, can damage neuronal structure and function,

particularly in brain regions critical for mood regulation, such as

the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex (18).

During perimenopause, E2 fluctuations exacerbate

these risks. E2 regulates mitochondrial biogenesis, dynamics and

antioxidant defense through both genomic pathways [such as nuclear

receptor-mediated regulation of peroxisome proliferator-activated

receptor γ coactivator 1-α (PGC-1α)] and non-genomic mechanisms

(such as membrane receptor signaling and mitochondrial DNA

protection) (18). As E2levels

decline, mitochondrial instability increases, resulting in greater

neuroenergetic vulnerability. Current interventions targeting these

mechanisms include HRT, mitochondria-targeted pharmacological

agents, antidepressants combined with psychotherapy and

lifestyle-based strategies involving physical activity, dietary

regulation and sleep hygiene (18). These integrated approaches aim to

restore mitochondrial function, reduce oxidative stress and enhance

both emotional and physical well-being in perimenopausal women.

Future research should explore the bidirectional crosstalk between

sex hormones and mitochondrial signaling, paving the way for more

precise and safer therapeutic strategies tailored to individual

pathophysiological profiles.

Perimenopausal mood disorders

Perimenopause denotes the transitional phase from

reproductive to non-reproductive life in women, typically spanning

the 2-8 years preceding menopause and the first year following the

final menstruation (19). This

period is characterized by substantial fluctuations in sex hormone

levels, particularly cyclical declines in E2 and progesterone,

which contribute to both endocrine and clinical heterogeneity

(20-22). These hormonal changes underpin a

range of symptoms, including menstrual irregularities, vasomotor

disturbances and alterations in mood and cognitive function.

Epidemiological characteristics

Extensive evidence highlights a marked increase in

the prevalence of psychiatric symptoms during perimenopause

(23). Epidemiological studies

suggest that ~70% of women experience some form of emotional

disturbance, including irritability, anxiety and depressive

symptoms (24). While some women

report mild mood instability, others may develop moderate-to-severe

depression or anxiety that notably impairs daily functioning and

social adaptation (10). A

meta-analysis of 55 studies revealed a global pooled prevalence of

depressive disorders in perimenopausal women at 33.9% (95% CI:

27.8-40.0%) (25). Another large

population-based study involving 9,141 women revealed that

perimenopausal women are at considerably higher risk of developing

depressive symptoms compared with their premenopausal counterparts

(26).

The onset of perimenopausal mood disorders is

influenced by a complex interaction of biological and psychosocial

risk factors. Low educational attainment, unemployment or part-time

employment, high perceived stress, menstrual irregularity,

constipation poor family relationships (27) and high neuroticism are all

associated with an increased risk of depression (28). By contrast, increased household

income and access to comprehensive healthcare serve as protective

factors (29-32). Notably, a personal history of

affective disorders predicts symptom recurrence or exacerbation

during perimenopause (8,33). In women with bipolar disorder,

perimenopause is often associated with a worsening of mood symptoms

(29-32). One study revealed that 68% of

perimenopausal women diagnosed with bipolar disorder experienced

major depressive episodes, with a markedly higher frequency

compared with their reproductive years (7). Similarly, longitudinal tracking of

13 women with bipolar disorder across premenopausal, perimenopausal

and postmenopausal stages revealed notable mood instability during

the perimenopausal transition (33).

Clinical manifestations

Fluctuating decline in ovarian function during

perimenopause results in considerable hormonal instability,

particularly in E2 and progesterone levels. These endocrine

fluctuations disrupt neurotransmitter systems and neural circuits

involved in emotional regulation, leading to mood symptoms that are

heterogeneous, episodic and often co-occurring with somatic and

cognitive disturbances. Epidemiological studies suggest that

perimenopausal women have a 2- to 4-fold increased risk of

developing major depressive disorder compared with their

premenopausal counterparts (34,35).

Typical depressive symptoms include persistent low

mood, anhedonia, fatigue, impaired concentration, excessive guilt

and pessimism regarding the future. Atypical features, such as

irritability and widespread somatic complaints (such as myalgia),

are also commonly reported (36). Notably, some women show reduced

responsiveness to standard antidepressant therapy. The presence of

severe life stress, a prior history of depression or psychotropic

medication use further elevates the likelihood of progression to

major depressive episodes, which may carry an increased risk of

suicidal ideation and behavior (37,38).

Anxiety is another prevalent symptom cluster, often

characterized by sustained tension, excessive worry, irritability

and distractibility. Autonomic symptoms, such as palpitations,

sweating and tremors, are frequently observed in conjunction with

anxiety (39). In perimenopausal

women, 60-70% report experiencing 'brain fog', a constellation of

mild cognitive deficits, including forgetfulness, reduced attention

and slowed thinking (40,41).

While these symptoms are generally transient, persistent cognitive

decline may heighten the risk for late-life neurodegenerative

disorders, such as Alzheimer's disease and vascular dementia. This

suggests that perimenopause may represent a key window for early

intervention in cognitive aging (42).

Somatic symptoms, including hot flashes, night

sweats, palpitations, headaches and musculoskeletal pain, are also

common and can create a bidirectional feedback loop with mood

disturbances, exacerbating both psychological and physical

symptoms. Sleep disorders are highly prevalent, manifesting as

difficulty falling asleep, frequent nighttime awakenings, early

morning waking and non-restorative sleep (43-45). Poor sleep quality not only

impairs daytime cognitive and physical functioning but is also

associated with anxiety, depression and vasomotor symptoms.

Notably, the interaction between vasomotor symptoms and emotional

states appears to be bidirectional and temporally complex,

collectively contributing to notable declines in quality of life

(46,47).

Pathophysiological mechanisms

Perimenopause represents a phase of profound

endocrine remodeling, during which rapid and irregular fluctuations

in sex hormones, particularly E2 and progesterone, markedly impact

brain regions, such as the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex,

involved in mood regulation (48). Several hormones, including

ovarian steroids, progesterone, testosterone, cortisol and their

neuroactive derivatives, have been implicated in the development

and modulation of perimenopausal mood disorders (22,49).

E2 carries out a key role in this context. Following

menopause, serum E2 levels reduce from premenopausal levels of 5-35

ng/dl to ~1.3 ng/dl (50,51).

This sharp decline is considered a key biological event

contributing to affective instability and cognitive impairment

during the menopausal transition (52,53). E2 exerts neuroprotective and

regulatory effects within the central nervous system (CNS). E2

deficiency induces cerebral hypoperfusion and vasoconstriction,

reducing oxygen supply to brain tissue and exacerbating cognitive

deficits (52). E2 receptors

(ERs) α and β are widely expressed across emotion-related neural

circuits, with particularly high activity in the ventral

corticolimbic-brainstem axis (54,55). ERα primarily regulates nuclear

gene transcription, while ERβ localizes to mitochondrial membranes,

modulating mitochondrial metabolism and cellular stress responses

(56).

E2 deficiency disrupts the synthesis and signaling

of key neurotransmitters, such as acetylcholine, glutamate (Glu)

and neuroprotective peptides, all of which are essential for

cognitive function (57).

Furthermore, E2 modulates dopaminergic and serotonergic systems.

Its withdrawal accelerates dopaminergic neuronal degeneration,

weakening reward circuitry and impairs serotonin (5-HT) synthesis

and reuptake, particularly during the night, contributing to

vasomotor symptoms such as hot flashes and nocturnal sweats

(58,59). Dysfunctional ERβ signaling may

also alter 5-HT transporter (SERT) activity and increase

5-HT1A receptor binding in the amygdala, enhancing the

processing of negative emotions and heightening vulnerability to

depression and anxiety (60,61).

Progesterone levels also fluctuate considerably

during perimenopause due to irregular ovulation and declining

luteal function. One of its key neuroactive metabolites,

allopregnanolone (ALLO), acts as a potent positive allosteric

modulator of the γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA)_A receptor, enhancing

inhibitory neurotransmission and exerting anxiolytic and

antidepressant effects (22,62-64). However, the inconsistent

synthesis of ALLO under conditions of hormonal instability may

destabilize GABAergic signaling, promoting mood lability and

increasing affective vulnerability (65,66). Additionally, concurrent

fluctuations in ovarian hormones and neurosteroids may impair

GABA_A receptor sensitivity, disrupting

hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis homeostasis and heightening

stress responsiveness, thereby elevating susceptibility to anxiety

and depressive symptoms (67,68).

Collectively, these findings emphasize the

multifactorial and hormone-sensitive nature of perimenopausal mood

disorders, shaped by complex interactions among E2, progesterone,

neurosteroids, neurotransmitters and neuroendocrine stress

systems.

Therapeutic strategies

HRT

HRT remains a primary intervention for alleviating

mood disturbances associated with E2 withdrawal in perimenopausal

women. Substantial clinical evidence supports its efficacy in

reducing depressive and anxiety symptoms. In a randomized

controlled trial, 17β-estradiol treatment markedly improved

depressive symptoms compared with placebo (68 vs. 17% remission

rate), highlighting its antidepressant potential (69). HRT has also demonstrated benefits

in improving irritability, sleep disturbances and other affective

symptoms, and, in some cases, serves as an adjunct to psychotropic

medications to enhance treatment response and overall functioning

(54,70).

However, the implementation of HRT requires careful

evaluation of the risk-benefit balance. Although it may reduce the

incidence of hip fractures and endometrial cancer, long-term use is

associated with increased risks of coronary artery disease, stroke,

breast cancer and dementia (71). These risks are especially

relevant for women > 50 years or those using HRT for >5 years

(72). By contrast, initiating

HRT before the age of 50 years may present a more favorable safety

profile. For asymptomatic women, the potential risks may outweigh

the benefits, particularly concerning breast cancer incidence

(71,73).

To overcome the limitations of conventional HRT,

alternative formulations have been developed. Tissue-selective E2

complexes, which combine E2s with selective E2 receptor modulators,

aim to retain therapeutic benefits while minimizing adverse effects

(74). Additionally, plant-based

phytoE2s, such as black cohosh extracts, have been explored for

their potential mood-enhancing effects. While early results are

promising, further research is necessary to confirm their long-term

efficacy and safety in perimenopausal populations (75).

Antidepressant therapy

Selective 5-HT reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and

5-HT-norepinephrine (NE) reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) are considered

first-line pharmacological treatments for perimenopausal depression

and anxiety. These medications function by inhibiting the

presynaptic reuptake of 5-HT and/or NE, thereby increasing synaptic

neurotransmitter availability and enhancing mood regulation

(76). SSRIs specifically target

SERT, while SNRIs inhibit both SERT and the NE transporter, making

them particularly effective for patients with concurrent anxiety

and reduced motivation.

Studies suggest that SSRIs may also have indirect

effects on estradiol levels, potentially enhancing cognitive and

neuroprotective benefits (77).

Due to their favorable efficacy and tolerability profiles, SSRIs

and SNRIs are widely recommended by international guidelines for

managing perimenopausal affective symptoms (71,73). However, considerable

interindividual variability in treatment response persists. Adverse

effects such as nausea, diarrhea, insomnia and sexual dysfunction

may affect some patients, and ~30% may fail to achieve sufficient

symptom relief with a single agent (78). Therefore, personalized medication

selection and continuous monitoring of therapeutic efficacy and

tolerability are key for optimizing patient outcomes.

Mitochondrial homeostasis and its

disruption

Mitochondrial function

Mitochondria are the primary bioenergetic organelles

in eukaryotic cells, responsible for generating ATP through the

tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle and oxidative phosphorylation

(OXPHOS) (79,80). This energy production process is

driven by the electron transport chain (ETC) and ATP synthase,

which together convert nutrients into usable cellular energy

(81). Reducing equivalents such

as NADH and flavin adenine dinucleotide (FADH2) donate

electrons to the ETC, ultimately leading to ATP synthesis and

maintaining cellular homeostasis. The TCA cycle metabolizes

pyruvate into carbon dioxide while producing NADH and

FADH2, which fuel the ETC (82).

Mitochondria also exhibit dynamic behavior regulated

by continuous cycles of fission and fusion. These processes are key

for maintaining mitochondrial integrity and function. Fission

allows for the removal of damaged mitochondria and supports

cellular adaptation under stress, while fusion promotes the mixing

of mitochondrial contents and enhances network connectivity to

optimize energy distribution (83).

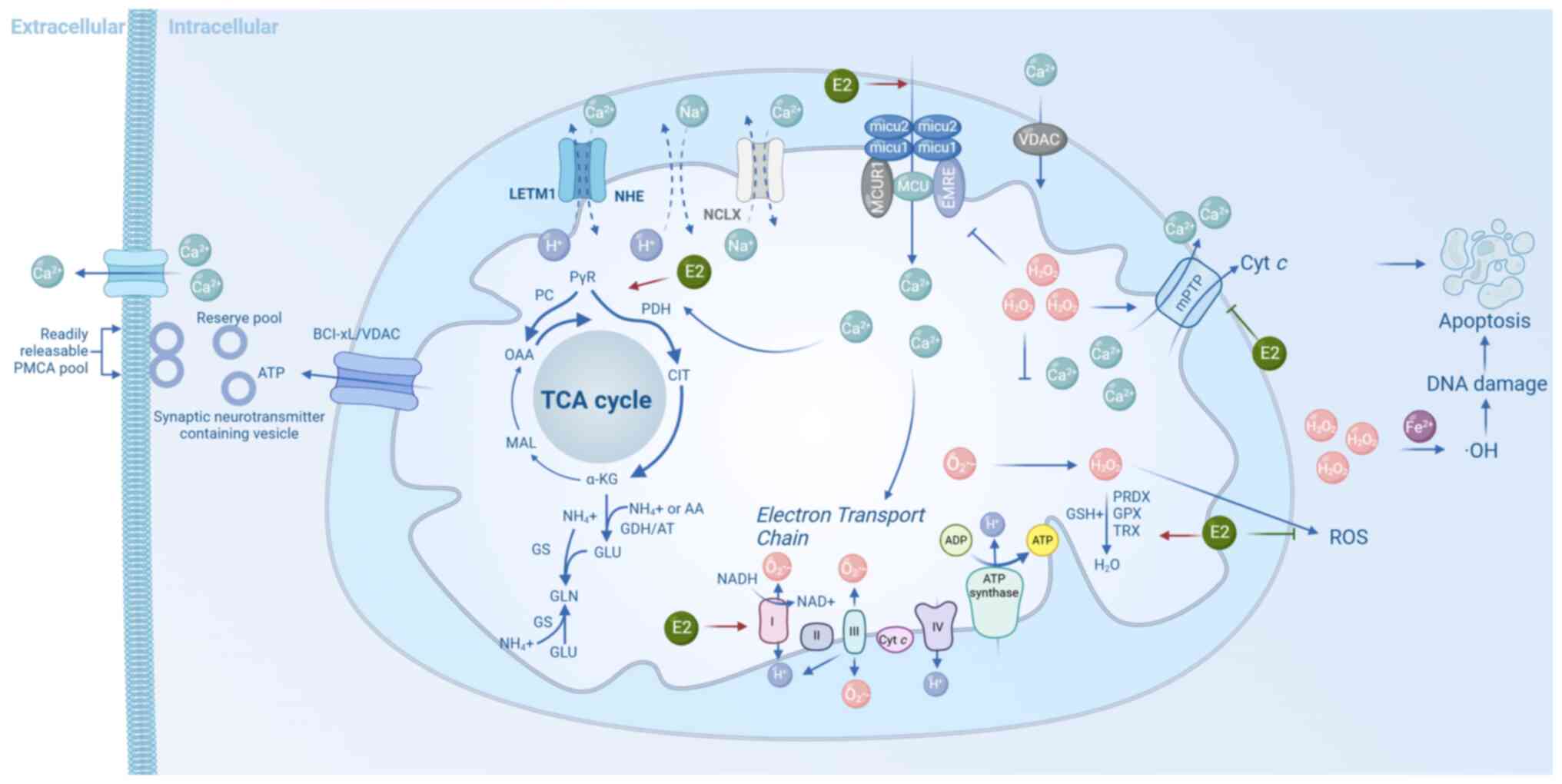

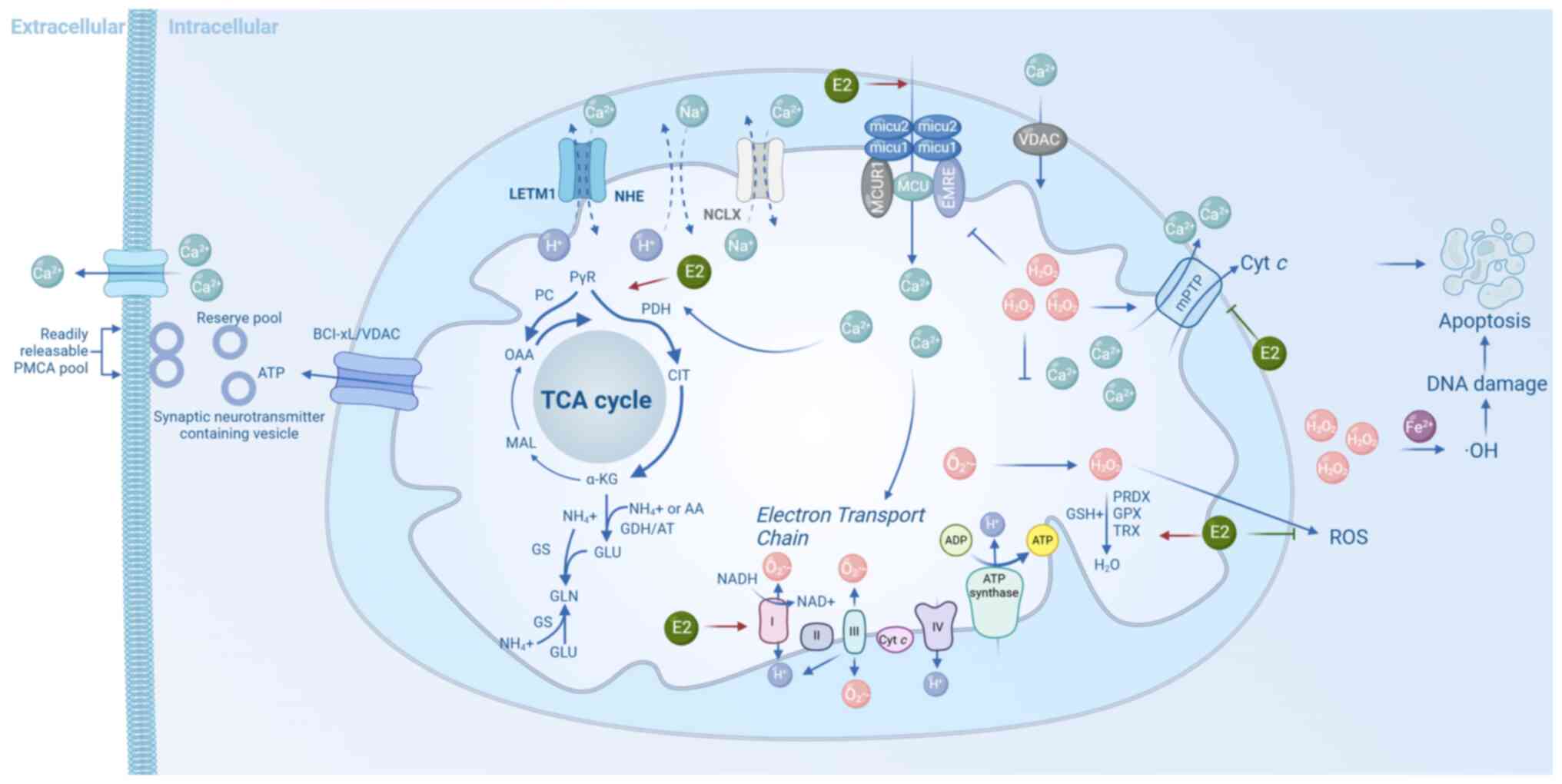

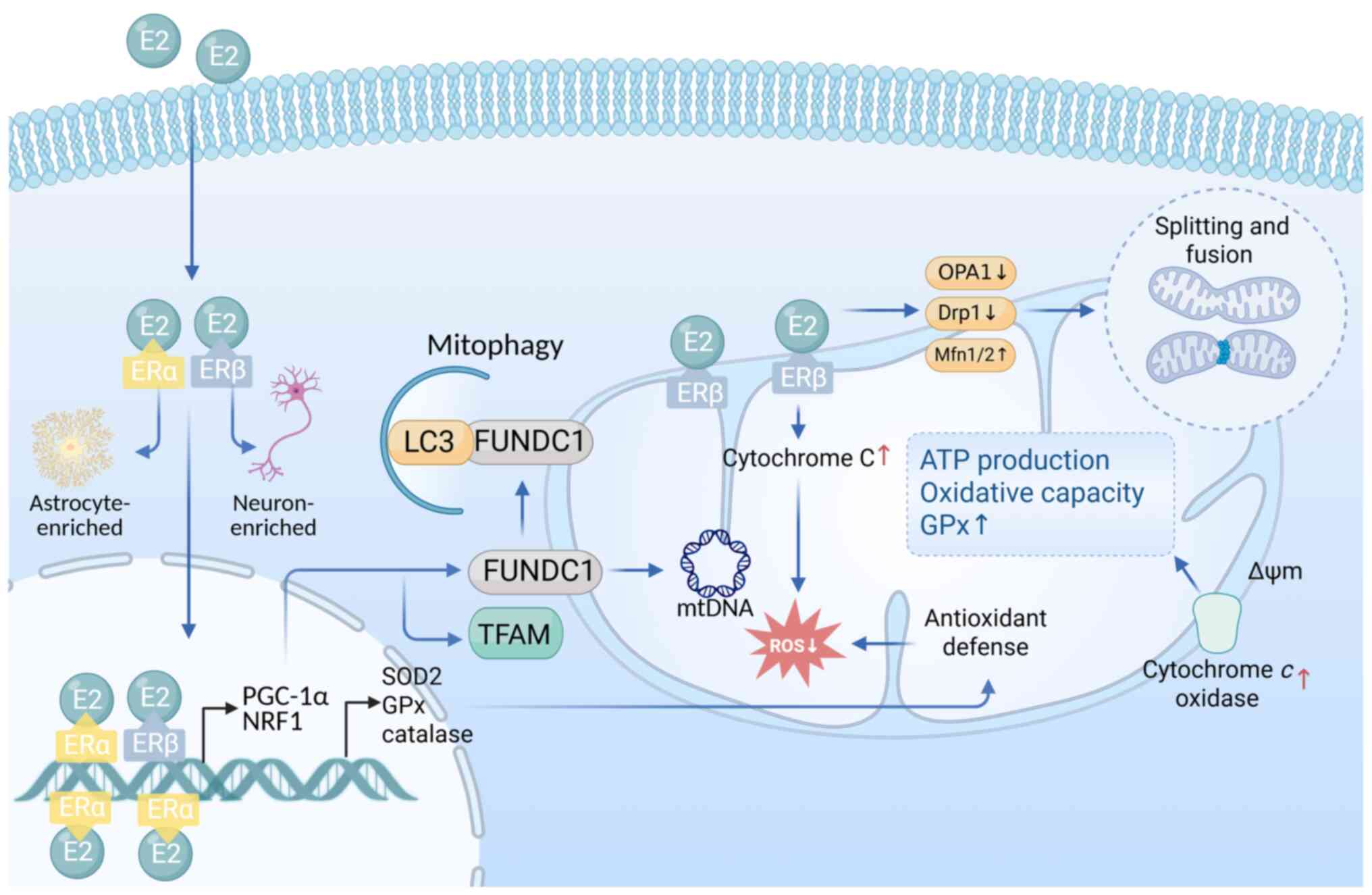

In the CNS, mitochondria are key not only for

sustaining neuronal energy demands but also for regulating

neurotransmitter synthesis, calcium buffering, oxidative stress

responses and apoptotic signaling (84) (Fig. 1). These functions are

particularly vital in neurons, which have high metabolic demands.

Neurons rely heavily on ATP to maintain resting membrane potential,

recycle synaptic vesicles and support neurotransmitter release.

Mitochondria dynamically redistribute within neurons in response to

local energy needs, often clustering near synaptic terminals during

periods of high activity to meet localized energy demands (85). This spatial and functional

plasticity is essential for maintaining synaptic transmission,

neuronal excitability and overall neurophysiological stability.

| Figure 1Key mitochondrial processes in

neuronal homeostasis. Mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake via VDAC

and the MCU complex activates TCA cycle dehydrogenases (PDH,

isocitrate dehydrogenase and α-KG dehydrogenase), promoting

NADH/flavin adenine dinucleotide (reduced form) production and ATP

synthesis. Electron leakage from complexes I/III generates

superoxide (O2−•), converted to

H2O2 and detoxified by antioxidant systems

(superoxide dismutase 2, GPX, PRDX, TRX and GSH). Excess ROS

triggers mPTP opening, cyt c release and apoptosis.

Glutamate is synthesized from α-ketoglutarate via GDH or

transaminases, supporting neurotransmission and nitrogen

metabolism. E2 enhances bioenergetics and antioxidant defense (red

arrows), while inhibiting ROS and apoptosis (green arrows). α-KG,

α-ketoglutarate; ATP, adenosine triphosphate; Ca2+,

calcium ion; Cyt c, cytochrome c; E2, 17β-estradiol;

GDH, glutamate dehydrogenase; GPX, glutathione peroxidase; GSH,

reduced glutathione; H2O2, hydrogen peroxide;

MCU, mitochondrial calcium uniporter; mPTP, mitochondrial

permeability transition pore; NADH, nicotinamide adenine

dinucleotide (reduced form); O2−•, superoxide

anion radical; PDH, pyruvate dehydrogenase; PRDX, peroxiredoxin;

ROS, reactive oxygen species; SOD2, superoxide dismutase 2; TCA

cycle, tricarboxylic acid cycle; TRX, thioredoxin; VDAC,

voltage-dependent anion channel. |

Mitochondria and neurotransmitter

regulation

Mitochondria carry out a direct and essential role

in the synthesis, metabolism and release of various

neurotransmitters. Their functional integrity is important for

maintaining synaptic transmission and emotional stability within

the CNS (85).

Glu, the primary excitatory neurotransmitter in the

brain, also serves as a precursor for the inhibitory

neurotransmitter GABA (86). The

synthesis of Glu is highly dependent on mitochondrial metabolism,

particularly through the TCA cycle, which generates α-ketoglutarate

(α-KG), a key substrate for Glu biosynthesis. Glu is then converted

to GABA via Glu decarboxylase, representing a key biochemical shift

from excitation to inhibition (87). In astrocytes, glutamine (Gln),

the major precursor of Glu, is synthesized via Gln synthetase and

transferred to neurons, where it is converted back into Glu by

phosphate-activated glutaminase, further entering mitochondrial

pathways.

Mitochondrial regulation of calcium

homeostasis

Mitochondria function as major intracellular calcium

(Ca2+) buffers, carrying out a key role in maintaining

cytosolic calcium homeostasis (84). Calcium signaling not only

facilitates intracellular signal transduction but also supports

mitochondrial bioenergetics by modulating the mitochondrial

membrane potential (ΔΨm), which is essential for ATP production. In

the mitochondrial matrix, moderate elevations in Ca2+

levels activate key dehydrogenases of the TCA cycle, such as

isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH) and α-KG dehydrogenase (α-KGDH),

thereby enhancing NADH production, fueling the ETC, and increasing

ATP synthase activity (88).

The precise regulation of mitochondrial calcium flux

is mediated by a network of transmembrane channel complexes. Under

resting conditions, Ca2+ enters the intermembrane space

through voltage-dependent anion channels located on the outer

mitochondrial membrane. It then crosses the inner membrane into the

matrix through the OXPHOS mitochondrial calcium uniporter (MCU)

complex, which includes core subunits such as MCU, MICU1, MCUR1 and

EMRE (89). These components

work together to regulate Ca2+ uptake in a tightly

controlled manner, ensuring efficient and safe calcium accumulation

(90,91). During neuronal excitation,

mitochondrial calcium uptake via the MCU is essential for

sustaining synaptic activity. Calcium buffering within mitochondria

supports synaptic vesicle fusion and neurotransmitter release by

shaping local calcium transients, thereby optimizing the efficiency

and timing of synaptic transmission.

In addition to their intrinsic calcium-handling

systems, mitochondria are functionally and structurally connected

to the ER at specialized membrane contact sites known as

mitochondria-associated membranes. These microdomains facilitate

calcium transfer between organelles. Upon stimulation, inositol

1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors on the ER release stored

Ca2+ near the mitochondrial outer membrane, where it is

taken up via the voltage-dependent anion channel-MCU pathway.

Conversely, sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase

pumps recapture cytosolic Ca2+ back into the ER,

contributing to calcium clearance and recycling (81).

Redox balance and oxidative stress

regulation

Mitochondria carry out a central role in maintaining

cellular redox balance, acting as both the primary source of ROS

and a key platform for their detoxification and stress response.

Under normal physiological conditions, electrons from NADH and

FADH2 are transferred through the mitochondrial ETC to

molecular oxygen, driving ATP synthesis. However, during this

process, especially at Complex I and Complex III, some electrons

may prematurely reduce oxygen, generating superoxide anion

(O2–•), the major intracellular ROS (92,93). Superoxide is rapidly dismutated

by mitochondrial superoxide dismutase (SOD2) into hydrogen peroxide

(H2O2), which can then form highly reactive

hydroxyl radicals (OH•) via Fenton chemistry in the presence of

transition metals such as Fe2+. While ROS at low levels

function as signaling molecules involved in transcriptional

regulation, proliferation, differentiation and immune responses

(94,95), excessive ROS production can

overwhelm the antioxidant defense system, leading to oxidative

stress. This imbalance results in protein oxidation, lipid

peroxidation, DNA damage and mitochondrial dysfunction, ultimately

causing cell death or senescence (92).

The generation of ROS is further exacerbated under

conditions of elevated mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) or an

imbalanced NADH/NAD+ ratio. To mitigate this,

mitochondria are equipped with robust enzymatic and non-enzymatic

antioxidant systems. In addition to SOD2, enzymes such as

glutathione peroxidase (GPx) and the thioredoxin-2/peroxiredoxin-3

system convert H2O2 into water, preventing

harmful accumulation. Glutathione, a major non-enzymatic

antioxidant, maintains the reduced intracellular environment and

participates in free radical neutralization (96).

ROS also activate nuclear antioxidant signaling

pathways that enhance cellular adaptive capacity. For example, ROS

can promote the dissociation of nuclear factor erythroid 2-related

factor 2 (Nrf2) from its repressor Keap1, enabling its nuclear

translocation and subsequent activation of antioxidant enzyme

genes, including SOD, GPx and heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) (97). Simultaneously, ROS activate

mitochondrial biogenesis and stress adaptation pathways through

coactivators and transcription factors such as PGC-1α and FOXO3a,

thereby enhancing mitochondrial resilience (98,99).

Moreover, mitochondrial quality control is

maintained through mitophagy, a process that selectively removes

damaged or ROS-overproducing mitochondria (100). This process is mediated by the

PINK1/Parkin pathway: Upon collapse of the ΔΨm, PINK1 stabilizes on

the outer membrane and recruits the E3 ubiquitin ligase Parkin,

which tags damaged mitochondria for autophagic degradation

(101). This mechanism

effectively prevents the propagation of ROS-induced damage and

preserves cellular homeostasis.

Mitochondria in the balance of cell

survival and apoptosis

Mitochondria are key regulators of the dynamic

balance between neuronal survival and apoptosis, serving as key

checkpoints in determining cell fate. While physiological apoptosis

is essential for eliminating damaged or dysfunctional neurons to

maintain brain homeostasis, aberrant activation of apoptotic

pathways can disrupt neural circuits and contribute to the

pathogenesis of mood disorders and neurodegenerative diseases

(102,103).

Under normal mitochondrial homeostasis,

anti-apoptotic members of the BCL-2 family, such as BCL-2 and

BCL-xL, are anchored in the outer mitochondrial membrane. These

proteins inhibit apoptosis by binding to and neutralizing

pro-apoptotic factors such as Bax and Bak, preventing their

oligomerization and subsequent increase in mitochondrial outer

membrane permeability, thereby promoting neuronal survival

(104). In response to cellular

stressors, including oxidative damage, calcium overload or DNA

damage, pro-apoptotic pathways are activated. For instance,

signaling through the Bad/p53 complex or the JNK-Bim axis promotes

the conformational activation and translocation of Bax to the

mitochondrial outer membrane. This destabilizes the membrane,

leading to a decrease in ΔΨm and the opening of the mitochondrial

permeability transition pore (mPTP) (105). Upon mPTP opening, cytochrome

c (Cyt c) is released from the mitochondrial

intermembrane space into the cytosol, initiating the intrinsic

(mitochondrial) apoptotic pathway. In the cytoplasm, Cyt c

binds to apoptotic protease-activating factor-1 and procaspase-9,

forming the apoptosome. This multiprotein complex activates

executioner caspases, such as caspase-3, initiating a cascade of

proteolytic events that ultimately lead to the programmed death and

clearance of damaged neurons (106).

E2ic regulation of mitochondrial

function

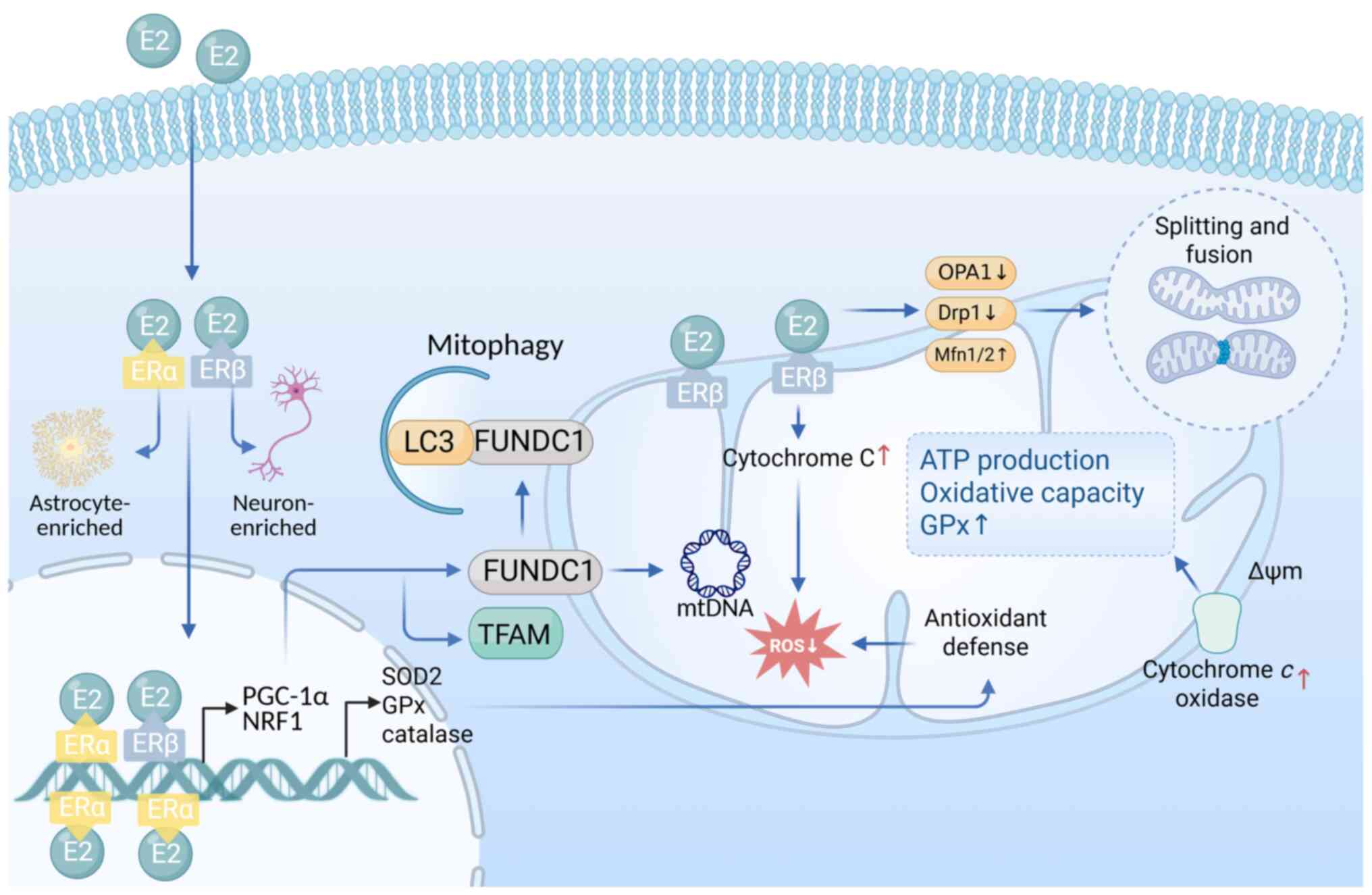

E2 regulates mitochondrial function through both

classical nuclear receptor signaling and rapid non-genomic

pathways, collectively coordinating mitochondrial biogenesis,

morphology, metabolic activity and responses to cellular stress

(Fig. 2) (107).

| Figure 2Estrogenic regulation of

mitochondrial function. E2 engages ERα and ERβ to regulate

mitochondrial function via genomic and non-genomic pathways. ERβ is

mainly located in mitochondria in neurons, while ERα shows

predominant nuclear expression in astrocytes. Genomically, it

upregulates TFAM and antioxidant enzymes (SOD2, GPx and catalase),

enhancing oxidative phosphorylation and redox balance.

Non-genomically, E2 stabilizes mitochondrial dynamics (↑Mfn1/2,

OPA1 and ↓Drp1) and promotes mitophagy via ERβ-FUNDC1 signaling.

Drp1, dynamin-related protein 1; E2, 17β-estradiol; ERα, estrogen

receptor α; ERβ, estrogen receptor β; FUNDC1, FUN14 domain

containing 1; GPx, glutathione peroxidase; Mfn1/2, mitofusin 1/2;

OPA1, optic atrophy 1; SOD2, superoxide dismutase 2; TFAM,

transcription factor A, mitochondrial. |

At the transcriptional level, E2 binds to its

receptor isoforms, ERα and ERβ, to activate several nuclear-encoded

mitochondrial regulatory factors, including nuclear respiratory

factor 1 (NRF1) and PGC-1α (107,108). NRF1 and PGC-1α work

synergistically to promote the expression of key genes such as

mitochondrial transcription factor A (TFAM), which facilitates

mtDNA transcription, replication and translation, thus supporting

the structural and functional integrity of OXPHOS complexes

(109-111). Notably, ERβ is also localized

to the mitochondrial membrane, where it exerts direct non-genomic

control over mitochondrial respiration (112,113). By modulating Cyt c

oxidase (complex IV) activity and stabilizing Δψm, ERβ enhances

respiratory efficiency and reduces electron leakage (113).

E2 further upregulates key mitochondrial antioxidant

enzymes, including SOD2, GPx and catalase, thereby enhancing

ROS-scavenging capacity (109).

It may also indirectly reduce ROS production by increasing Cyt

c mRNA and protein expression, thereby strengthening

antioxidant defenses (114).

Beyond metabolic and redox control, E2 influences mitochondrial

morphology by suppressing the recruitment and activation of the

fission-related protein dynamin-related protein 1 (Drp1) and

promoting the expression of fusion proteins such as mitofusin 1/2

(Mfn1/2) and optic atrophy 1 (OPA1) (115). These actions together support

mitochondrial network integrity and ensure efficient energy

distribution (116).

Mitochondrial homeostasis disruption in

perimenopausal mood disorders

During menopause, the abrupt decline in E2 has been

revealed to disrupt mitochondrial homeostasis, leaving measurable

bioenergetic signatures across both central and peripheral tissues

(99,107-112,114-117) (Table I). Clinical studies indicate that

postmenopausal women exhibit a ~30% reduction in ATP production

efficiency, which associates directly with decreased activity of

mitochondrial complex IV, COX (118). Translational neuroimaging

studies, combining 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron

emission tomography (18F-FDG PET) and phosphorus-31

magnetic resonance spectroscopy (31P-MRS), reveal a

concurrent decline in cerebral metabolic rate of glucose

consumption (CMRglc) and OXPHOS efficiency in perimenopausal women

(118). Notably, the extent of

metabolic decline is inversely correlated with Beck Depression

Inventory-II (BDI-II) scores, suggesting an association between

impaired brain energetics and depressive symptom severity (119). Furthermore, reduced glucose

utilization in the brain has been associated with decreased Cyt

c oxidase activity in peripheral blood platelets, indicating

a parallel dysfunction of mitochondrial metabolism in both the CNS

and peripheral tissues (120).

This pattern of metabolic disruption appears to result not merely

from chronological aging, but from hormone-driven 'endocrine aging'

that destabilizes mitochondrial function. Collectively, these

findings highlight mitochondrial E2 dependence as a key mechanistic

factor underlying perimenopausal mood disorders.

| Table IRegulatory effects of estrogen on

mitochondrial function and after its decline. |

Table I

Regulatory effects of estrogen on

mitochondrial function and after its decline.

| Author/s, year | Regulatory

mechanisms | Role of

estrogen | Effects of estrogen

decline | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Gaignard et

al, 2017; Velarde, 2014; Klinge, 2008 | Mitochondrial gene

expression | Activates NRF1 and

PGC-1α via ERα/ERβ, promoting mitochondrial biogenesis and

respiratory complex expression. | Downregulates NRF1

and PGC-1α, impairs mtDNA replication, reduces energy-related gene

expression by ~40%. | (107,110,111) |

| Salnikova et

al, 2021; Kim et al, 2024; Yin et al, 2021 | Fission and fusion

balance | Inhibited Drp1,

promoted the expression of Mfn1/Mfn2 and Opa1, and maintained

mitochondrial homeostasis. | Increases Drp1

activity (~1.5-fold), reduces fusion proteins, leading to

fragmentation and abnormal morphology. | (115-117) |

| Kemper et

al, 2014; Rettberg et al, 2014; Miao et al,

2024 | Respiration and ATP

synthesis | Enhances ETC

activity, supports COX function, stabilizes Δψm, and boosts ATP

production. | Decreases ATP yield

(~30%), OCR and glucose utilization. | (108,112,118) |

| Gujardo-Correa

et al, 2022; Stirone et al, 2005; Miao et al,

2024 | Antioxidant

defense | Induces SOD2, GPx,

and catalase expression, reducing mitochondrial ROS

accumulation. | Decreases SOD2,

increases ROS by 50-80%, causing oxidative damage to membranes,

proteins and DNA. | (109,114,118) |

| Plovanich et

al, 2013; Hunter et al, 2012 | Calcium

homeostasis | Regulates

MCU-mediated Ca2+ influx, supporting ATP synthase

activity and calcium signaling. | MCU dysfunction

reduces Ca2+ uptake (~40%), impairing respiration and

triggering apoptotic pathways. | (126,127) |

| Liu et al,

2021; Li et al, 2023 | Mitophagy | FUNDC1 is

upregulated by PGC-1α to promote mitochondrial clearance of

damage. | Autophagy disorder

leads to damage mitochondrial accumulation and a further increase

in ROS, creating a vicious cycle. | (99,158) |

Mitochondrial bioenergetic

dysfunction

E2 deficiency during perimenopause is a major driver

of mitochondrial bioenergetic impairment, with the ETC being a

primary target. Experimental studies indicate that E2 enhances the

expression and activity of several ETC complexes, including Complex

I (NDUFB8), Complex IV (MTCO1) and Complex V (121). In the absence of E2, the

Erβ-PGC-1α-NRF1 transcriptional axis is downregulated, leading to

reduced expression of OXPHOS subunits, decreased ΔΨm and impaired

coupling between substrate oxidation and ATP synthesis (122). In ovariectomized rats,

mitochondrial oxygen consumption rate in skeletal muscle decreases

by ~25% at rest, with maximal respiratory capacity reduced by up to

≤40% (123). These deficits

associate with diminished expression of Complex I and IV subunits,

highlighting the structural and functional deterioration of the ETC

as a key mechanism underlying energy failure due to E2

deficiency.

Additionally, E2 regulates the TCA cycle through

epigenetic mechanisms. E2 withdrawal suppresses sirtuin 1-mediated

deacetylation of key metabolic enzymes, resulting in downregulation

of IDH 3α (IDH3α) and α-KGDH, both rate-limiting enzymes in the TCA

cycle (124,125). This suppression limits NADH

production, reducing electron supply to the ETC and slowing TCA

cycle throughput.

E2 also positively regulates the expression and

assembly of the MCU complex. When E2 levels decline <50 pg/ml,

dysfunctional MCU assembly limits mitochondrial Ca2+

uptake, impairing ATP synthase activation and disrupting

calcium-dependent apoptotic signaling (126). Mitochondrial Ca2+ is

essential for activating key dehydrogenases in the TCA cycle, such

as pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH), IDH and α-KGDH, which facilitate

NADH and FADH2 production. These reducing equivalents

fuel the ETC, enhancing ATP synthesis and supporting mitochondrial

bioenergetics. In perimenopausal women, E2 deficiency reduces

mitochondrial Ca2+ sensitivity, impairing respiratory

efficiency and energy output (127). Moreover, dysregulated

mitochondrial Ca2+ buffering disrupts the spatial and

temporal precision of calcium transients required for synaptic

vesicle release. This leads to inefficient neurotransmission and

contributes to excitatory/inhibitory (E/I) imbalance, often

manifested as elevated extracellular Glu levels and reduced

GABAergic tone. Such imbalances compromise synaptic plasticity,

long-term potentiation and network stability in limbic regions

(128).

Furthermore, E2 deficiency impairs fatty acid

oxidation by downregulating carnitine palmitoyltransferase I, a key

enzyme responsible for mitochondrial fatty acid uptake and

β-oxidation. This defect limits the utilization of alternative

energy substrates and reduces overall metabolic flexibility

(125). E2 also influences

glucose metabolism at multiple regulatory points. Its absence leads

to reduced expression of glucose transporters GLUT1 and GLUT4 in

the brain, and GLUT3 and GLUT4 in peripheral tissues. Additionally,

increased phosphorylation of PDH inhibits its activity, impairing

pyruvate utilization and mitochondrial entry. These combined

effects result in reduced glucose uptake and decreased lactate

production, reflecting a broad suppression of glucose oxidative

capacity (129).

Impaired antioxidant defense

E2 deficiency markedly disrupts mitochondrial

antioxidant defense systems, exacerbating oxidative stress and

contributing to mitochondrial dysfunction. The phenolic hydroxyl

group of E2, particularly on the A-ring, acts as a direct free

radical scavenger by donating hydrogen atoms to neutralize ROS,

thereby exerting non-enzymatic antioxidant effects (118). In perimenopausal women, a

decline in circulating E2 levels is associated with a 50-80%

increase in ROS production, positioning E2 loss as a key driver of

mitochondrial oxidative stress. E2 deficiency downregulates the

Erβ-PGC-1α-NRF1 transcriptional axis, leading to suppressed SOD2

expression and impaired clearance of mitochondrial ROS, initiating

a vicious cycle of oxidative damage and mitochondrial

destabilization (122).

Concurrently, reduced expression of OXPHOS subunits further impairs

mitochondrial electron flow, resulting in decreased ΔΨm and

diminished coupling efficiency. These alterations increase the

NADH/NAD+ ratio, which inhibits Complex I activity and

promotes electron leakage to oxygen, generating additional

superoxide radicals and intensifying oxidative injury (130).

Excessive ROS not only impair ETC function but also

activate pro-inflammatory and pro-apoptotic pathways. For example,

elevated ROS levels can trigger the assembly of NLRP3

inflammasomes, promote mPTP opening and initiate caspase-mediated

apoptosis. These downstream effects contribute to neuroinflammation

and neuronal loss, thereby reinforcing the pathological association

between E2 decline, mitochondrial dysfunction and mood disorders

during perimenopause (131).

Imbalance in mitochondrial dynamics

E2 decline also promotes mitochondrial fission,

resulting in fragmented mitochondria with disorganized cristae and

reduced inter-organelle connectivity. Such fragmentation impairs

substrate and protein exchange across the mitochondrial network,

compromises ΔΨm and reduces coupling efficiency between electron

transport and ATP synthesis.

Mechanistically, E2 deficiency increases the

expression and activation of the fission protein Drp1, particularly

through phosphorylation at Ser616. By contrast, the expression of

key fusion proteins, Mfn1/2 and Opa1, is downregulated (117). This imbalance between enhanced

fission and suppressed fusion leads to structural fragmentation,

metabolic uncoupling and deterioration of respiratory chain

function, all of which contribute to bioenergetic failure.

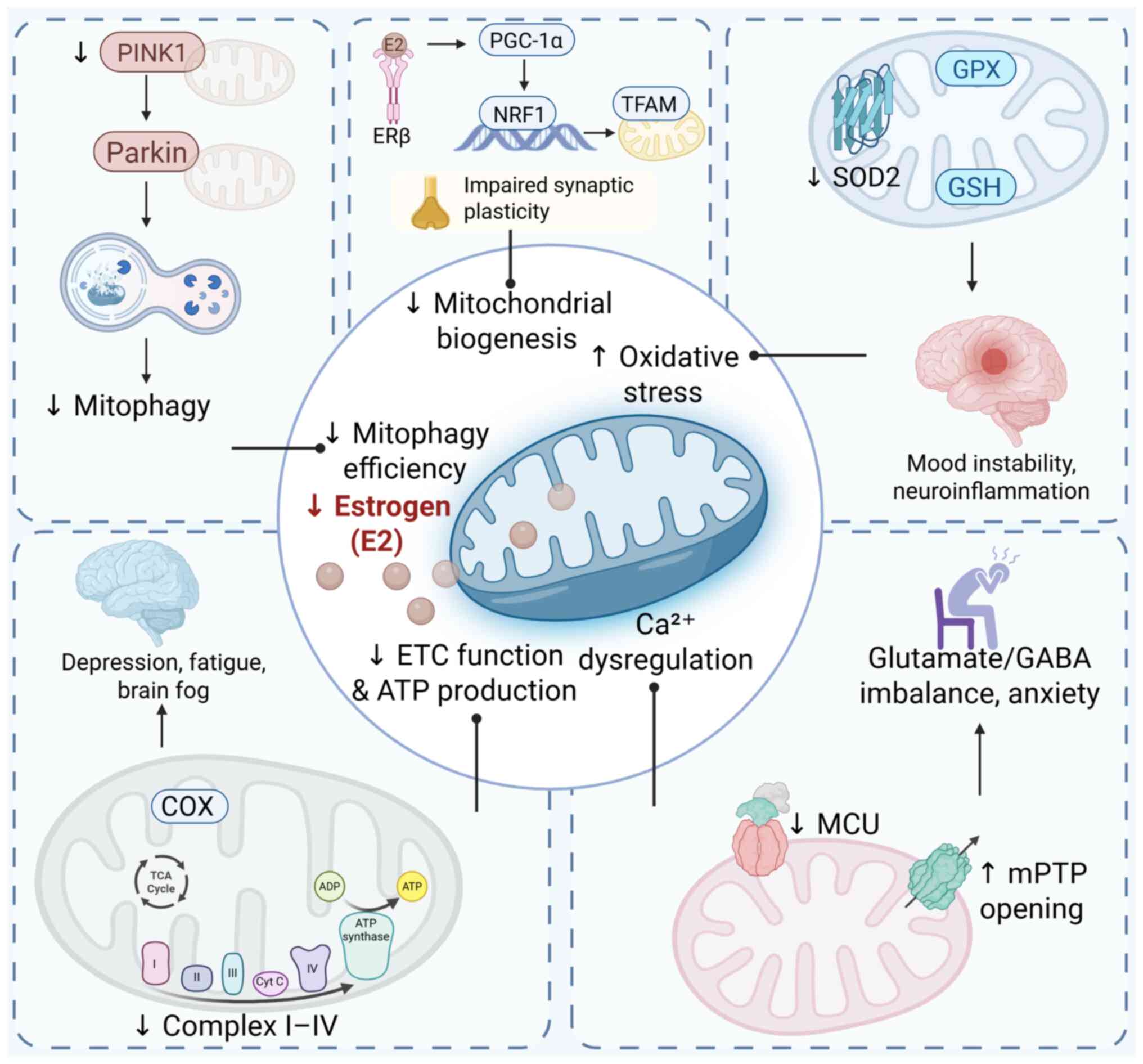

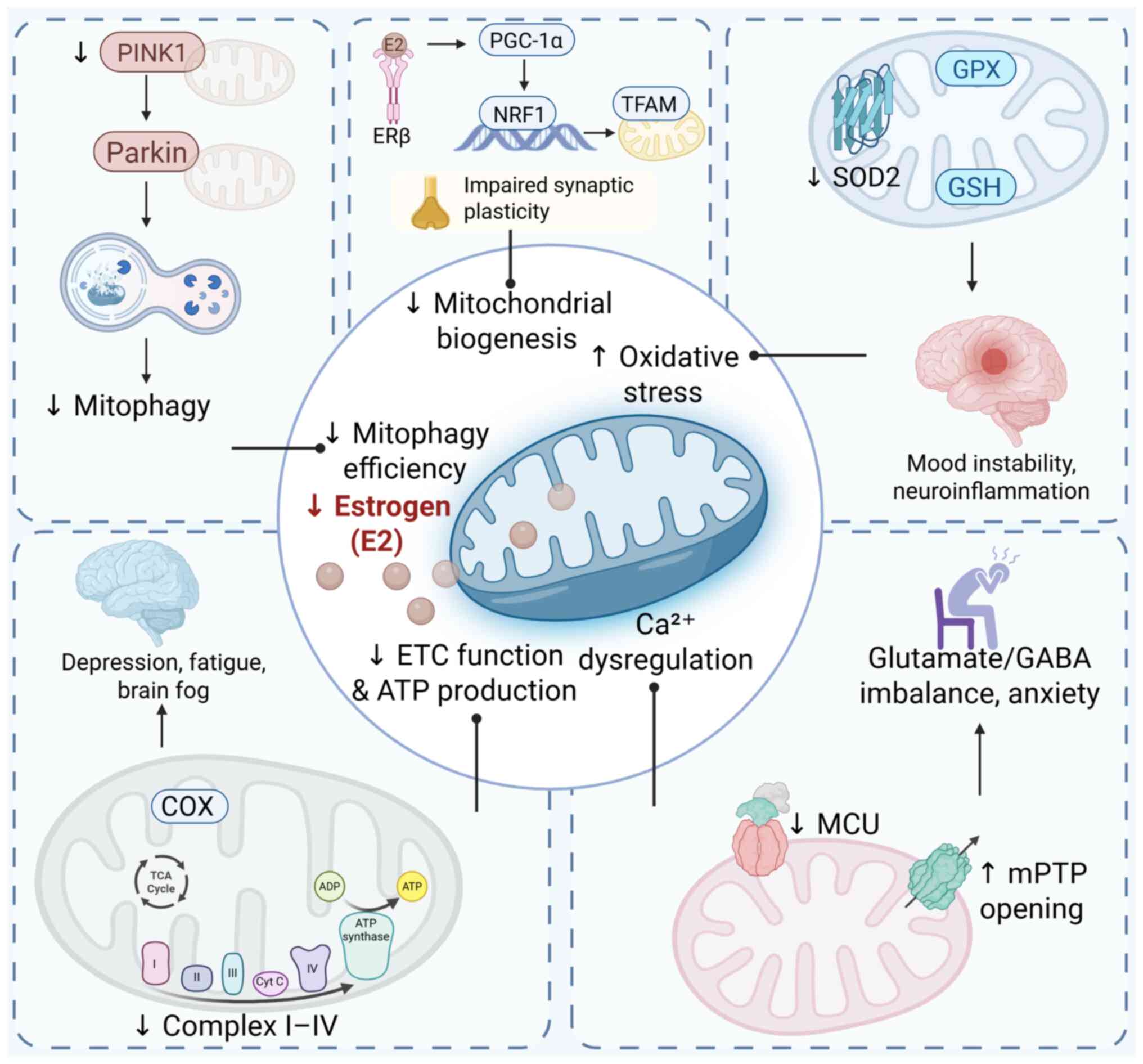

To illustrate the association between E2 signaling,

mitochondrial integrity and mood regulation, a conceptual framework

outlining the hormone-mitochondria-mood axis is proposed (Fig. 3). As summarized, declining E2

levels during perimenopause disrupt key mitochondrial processes,

such as biogenesis, antioxidant defense, calcium homeostasis,

mitophagy and energy metabolism, through multiple nuclear and

cytoplasmic signaling pathways (132). These impairments collectively

compromise neuronal function and synaptic plasticity in

emotion-related brain regions, such as the hippocampus and

prefrontal cortex, contributing to the onset of affective and

cognitive symptoms (133).

| Figure 3Disruption of the

hormone-mitochondria-mood axis in estrogen deficiency. Estrogen

deficiency induces multifaceted mitochondrial dysfunction in

mood-regulating brain regions, characterized by impaired oxidative

phosphorylation, reduced ATP synthesis, excessive reactive oxygen

species accumulation, dysregulated fission-fusion dynamics and

suppressed mitophagy. These alterations compromise neuronal

bioenergetic capacity and redox homeostasis, contributing to

synaptic dysfunction and neuroinflammatory cascades. This

mechanistic continuum constitutes the hormone-mitochondria-mood

axis, wherein endocrine withdrawal drives mitochondrial

destabilization, ultimately predisposing individuals to affective

and cognitive disturbances during the perimenopausal transition.

ATP, adenosine triphosphate; Ca2+, calcium ion; COX,

cytochrome c oxidase (complex IV); E2, 17β-estradiol; ETC, electron

transport chain; GABA, gamma-aminobutyric acid; GPX, glutathione

peroxidase; GSH, reduced glutathione; MCU, mitochondrial calcium

uniporter; mPTP, mitochondrial permeability transition pore; NRF1,

nuclear respiratory factor 1; Parkin, Parkin RBR E3 ubiquitin

protein ligase; PGC-1α, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor

gamma coactivator 1-α; PINK1, PTEN-induced putative kinase 1; ROS,

reactive oxygen species; SOD2, superoxide dismutase 2; TCA,

tricarboxylic acid cycle; TFAM, transcription factor A,

mitochondrial. |

Limitations and prospects

Limitations of current research

Clinical confounders and mechanistic

gaps

Perimenopause represents a complex physiological

transition characterized by notable hormonal fluctuations and

multisystem remodeling. During this stage, E2 and progesterone

levels fluctuate along individualized trajectories, profoundly

affecting CNS function and mood regulation pathways (134). While the majority of women

experience varying degrees of mood disturbances, such as

depression, anxiety and cognitive impairment, others may remain

largely asymptomatic. The clinical presentation of perimenopausal

mood disorders reflects the unique interplay between biological

factors and psychosocial influences, encompassing depressive and

anxious symptoms, cognitive decline and somatic complaints. This

variability is likely due to differences in hormone sensitivity,

genetic polymorphisms, psychiatric history and exposure to life

stressors. These confounding factors introduce considerable

variability, complicating the comparability and generalizability of

clinical research findings. Future studies should implement

stratified analyses based on individual stress exposures, assessed

using validated psychological or life event scales, to

differentiate between stress-induced and hormone-driven

mitochondrial alterations.

Although growing evidence implicates mitochondrial

dysfunction, such as impaired ATP production, elevated oxidative

stress, disrupted mitophagy and calcium dysregulation, in the

pathogenesis of perimenopausal mood disorders, the underlying

mechanisms remain poorly understood (135). To date, no fully integrated

pathological cascade has been established associating sex hormone

decline, mitochondrial dysfunction, neurotransmitter imbalance and

affective symptoms. Much of the mechanistic insight stems from

animal models or in vitro systems, which may not accurately

replicate the physiological complexity of human perimenopause.

Additionally, to the best of our knowledge, high-quality,

longitudinal clinical studies specifically targeting perimenopausal

populations are lacking. This gap restricts the development of

robust, evidence-based conclusions and limits the translational

potential of mitochondrial biomarkers and targeted interventions in

this context. Moreover, individual genetic variations in

mitochondrial or E2-responsive genes, such as ESR1, TFAM, PGC-1α

and NRF1, may influence mitochondrial biogenesis, redox regulation

and susceptibility to hormonal decline (136). These polymorphisms may explain

the heterogeneous responses to both E2 loss and therapeutic

interventions across perimenopausal women.

Limitations of current diagnostic and

therapeutic strategies

Although peripheral mitochondrial markers, such as

platelet Cyt c oxidase activity, have been proposed as

minimally invasive proxies for CNS mitochondrial function, their

diagnostic utility remains limited. Differences in metabolic

demand, regulatory environment and cell-type specificity between

platelets and neurons may obscure central pathophysiological

signals (137). Therefore,

future studies should integrate peripheral bioenergetic markers

with neuroimaging and hormonal profiling to establish more

reliable, multidimensional diagnostic tools.

HRT can enhance ΔΨm, increase ATP synthesis

efficiency and upregulate antioxidant enzymes such as SOD2 and GPx,

thereby improving neuronal bioenergetics and redox homeostasis

while attenuating central oxidative stress (138). Notably, the variability in HRT

efficacy may reflect underlying differences in mitochondrial status

among individuals. Women with higher baseline oxidative stress or

impaired mitophagy may exhibit diminished mitochondrial

responsiveness to E2, limiting the therapeutic benefits of HRT

(56). Identifying such

biomarkers could guide personalized interventions.

Mitochondria-targeted therapies, including antioxidants [such as,

coenzyme Q10, N-acetylcysteine (NAC) and α-lipoic acid] and

mitochondrial nutritional supplements, have emerged as promising

alternatives aimed at mitigating oxidative stress and restoring

mitochondrial function.

Additionally, emerging mitochondria-targeted

compounds, such as SS-31 (elamipretide) and MitoQ, have

demonstrated preclinical efficacy in reducing oxidative damage and

restoring mitochondrial function in neuronal models of depression

and E2 deficiency (139).

Although preclinical studies and animal models have revealed

improvements in energy metabolism, reductions in ROS production,

and beneficial behavioral effects in depression and anxiety

paradigms, human studies remain limited. Current clinical trials in

perimenopausal populations face challenges such as small sample

sizes, short intervention durations and a lack of appropriate

control groups, restricting the generalizability and strength of

evidence needed for clinical implementation. Another key limitation

is the prevailing 'one-size-fits-all' approach in current treatment

paradigms, which fails to account for the considerable

interindividual heterogeneity in clinical phenotype, hormonal

responsiveness, mitochondrial status and genetic background

(140).

Future directions

Multi-omics integration and precision

medicine

The advent of large-scale multi-omics approaches,

including metabolomics, epigenomics and neuroimaging, offers

increasing potential to address the heterogeneity of perimenopausal

mood disorders and move toward precision medicine. By integrating

genetic variations, epigenetic modifications, inflammatory profiles

and metabolic signatures with neurofunctional imaging markers,

researchers have begun identifying biologically distinct subtypes

of depression (141). Recent

studies, for instance, have utilized machine learning clustering

based on low-frequency amplitude features from functional magnetic

resonance imaging, combined with multi-omics data, to classify

depression into molecularly distinct subtypes (141,142). These subtypes demonstrate

divergent characteristics in neurodevelopment, synaptic regulation

and immune-inflammatory dysregulation, and associate with

differences in symptom severity.

Extensive evidence has validated the concept of

mechanism-based stratification and highlighted the need for

personalized interventions tailored to individual molecular and

neurobiological profiles (143-145). Moving forward, the integration

of artificial intelligence and machine learning is expected to

enhance data analysis efficiency and support predictive modeling

for disease trajectories and treatment responsiveness in

perimenopausal populations. To further elucidate the

pathophysiological role of mitochondrial dysfunction and inform

treatment development, future studies should integrate omics-based

profiling with dynamic neuroimaging to map the spatiotemporal

relationship between mitochondrial imbalance and affective

symptoms.

Multipathway combination

therapies

Mitochondrial dysfunction in perimenopausal mood

disorders is often accompanied by oxidative stress and neuronal

injury. Antioxidant agents such as coenzyme Q10, vitamin E and NAC

reduce ROS production, enhance mitochondrial ATP levels, and

restore membrane potential (146). These effects contribute to

improved neuroenergetic function and emotional regulation. For

instance, vitamin E has demonstrated efficacy in improving vaginal

health and modulating hormone levels in perimenopausal women, with

a favorable safety profile (147). However, the majority of studies

on coenzyme Q10 and NAC have primarily focused on ovarian function,

and their long-term efficacy and safety in mood-related contexts

remain insufficiently validated (148,149). Natural compounds that activate

the Nrf2 signaling pathway, such as curcumin and resveratrol, have

also demonstrated promise in reducing oxidative stress, mitigating

inflammation and enhancing mitochondrial resilience in preclinical

models (150). ALA upregulates

mitochondrial TFAM, promoting mtDNA replication and mitochondrial

biogenesis, and functions as a cofactor in the ETC, directly

enhancing redox function (151).

Given the multifactorial nature of mitochondrial

imbalance, multipronged therapeutic strategies are likely more

effective than single-target approaches (Table II) (69,71,73,76,78,146,151-153). For example, Nrf2 activators

upregulate endogenous antioxidant defenses and exert

neuroprotective, anti-apoptotic effects, while mitophagy modulators

promote the selective clearance of dysfunctional mitochondria.

Mitophagy deficits are increasingly implicated in depression

pathogenesis; therefore, enhancing mitochondrial quality control

may offer therapeutic benefits. A growing body of preclinical

evidence supports the antidepressant potential of

mitophagy-promoting interventions in animal and cellular models

(154). While multi-pathway

approaches hold promise, priority should be given to interventions

supported by clinical trials, such as phytoE2s (for example

genistein), melatonin or lifestyle strategies such as exercise and

dietary modulation.

| Table IIComparison of therapeutic strategies

targeting imbalances in mitochondrial homeostasis. |

Table II

Comparison of therapeutic strategies

targeting imbalances in mitochondrial homeostasis.

| Author/s, year | Treatment

strategy | Mechanism of

action | Evidence | Potential

risks/limitations | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Soares et

al, 2001; van Staa et al, 2008; Rossouw et al,

2002 | HRT | Replenishes

estrogen, restores mitochondrial membrane potential, ATP production

and antioxidant defense. | RCTs show notable

symptom reduction in perimenopausal depression (remission, 68 vs.

17%) | Potential long-term

risks: Cardiovascular disease and breast cancer. | (69,71,73) |

| Yan 2014; Wagner

et al, 2012 |

Mitochondria-targeted drugs | Antioxidants

(CoQ10, NAC) reduce ROS; α-lipoic acid enhances energy metabolism

and promotes mitochondrial biogenesis via TFAM. | Animal studies

confirm improved mitochondrial function and gene expression. | Limited clinical

data; long-term safety remains uncertain. | (146,151) |

| Stahl et al,

2005; Parry, 2010 | Antidepressants and

psychological therapy | SSRIs/SNRIs

increase monoamine levels; CBT modifies cognition and alleviates

emotional symptoms. | SSRIs and

phototherapy improve mood; CBT reduces anxiety and sleep

issues. | Side effects (such

as nausea and sexual dysfunction); efficacy varies among

individuals. | (76,78) |

| Shon et al,

2023; Shavaisi et al, 2024 | Lifestyle

interventions | Diet (such as

omega-3 and soy) offers antioxidant/anti-inflammatory effects;

exercise improves metabolism and neuroplasticity. | Improves

progesterone levels, mood, and gut microbiota; reduces

inflammation | Requires long-term

adherence; outcomes vary with individual compliance. | (152,153) |

Nanomedicine and mitochondria-targeted

delivery

To address limitations in drug targeting and

delivery efficiency, the development of mitochondria-targeted

nanomedicine has emerged as a promising strategy. Functionalized

nanoparticles can penetrate both cellular and mitochondrial

membranes, as well as the blood-brain barrier, enabling direct

delivery of therapeutics into neuronal mitochondria. This approach

enhances drug bioavailability, stability and organelle specificity

(155,156).

The structural complexity of mitochondria often

restricts the effective delivery of conventional compounds.

Nanocarriers, such as ligand-functionalized lipid nanoparticles and

MITO-Porter systems, can preferentially accumulate within

mitochondria, facilitating the precise release of antioxidants and

metabolic modulators (157).

However, these experimental strategies are still in the early

stages of development and require further validation before

clinical application.

Conclusion

Perimenopausal mood disorders result from complex

interactions between hormonal decline and mitochondrial

dysfunction. The present review highlights disrupted mitochondrial

homeostasis, including impaired OXPHOS, calcium imbalance, redox

stress and defective mitophagy, as a central mechanism linking E2

loss to neuropsychiatric symptoms. E2 modulates mitochondrial

function through both genomic and non-genomic pathways, positioning

mitochondria as key mediators of hormonal effects on brain health.

While preclinical evidence supports mitochondrial targets, clinical

translation remains hindered by insufficient biomarker-based

stratification and a lack of long-term data. Future research should

integrate multi-omics, neuroimaging and artificial

intelligence-driven subtyping to develop personalized,

mitochondria-targeted interventions. Restoring mitochondrial

integrity presents a novel therapeutic approach for enhancing

emotional and cognitive resilience in perimenopausal women.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

YY and HY drafted the initial version of the

manuscript. ZL and LF contributed to the collection, organization,

and critical interpretation of the literature. JL and YL assisted

in preparing figures and tables and participated in manuscript

editing. WL and HC provided intellectual input, supervised the

writing process, and revised the manuscript for important content.

XW conceived the review topic, guided the overall structure, and

finalized the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final

version. Data authentication is not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present review was funded by Heilongjiang Postdoctoral Fund

(grant no. LBH-Z22283), the Scientific Research Fund of

Heilongjiang University of Chinese Medicine (grant no.

2024XJJ-QNCX020), Heilongjiang Provincial Undergraduate

Universities Basic Scientific Research Fund-Research Project (grant

no. 2024-KYYWF-1389), Heilongjiang Provincial TCM Research Project

(grant no. ZHY2024-233), the Heilongjiang Provincial Natural

Science Foundation (grant no. PL2024H220) and the Heilongjiang

Provincial Chinese Medicine Scientific Research Project (grant no.

HYZ2022-128).

References

|

1

|

Santoro N: Perimenopause: From research to

practice. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 25:332–339. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Cunningham AC, Pal L, Wickham AP, Prentice

C, Goddard FGB, Klepchukova A and Zhaunova L: Chronicling menstrual

cycle patterns across the reproductive lifespan with real-world

data. Sci Rep. 14:101722024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Woods NF, Smith-Dijulio K, Percival DB,

Tao EY, Taylor HJ and Mitchell ES: Symptoms during the menopausal

transition and early postmenopause and their relation to endocrine

levels over time: Observations from the seattle midlife women's

health study. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 16:667–677. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Cheng MH, Hsu CY, Wang SJ, Lee SJ, Wang PH

and Fuh JL: The relationship of self-reported sleep disturbance,

mood, and menopause in a community study. Menopause. 15:958–962.

2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Wang ST, Gu HY, Huang ZC, Li C, Liu WN and

Li R: Comparative accuracy of osteoporosis risk assessment tools in

postmenopausal women: A systematic review and network

meta-analysis. Int J Nurs Stud. 165:1050292025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Freitas JPC, Santos JNV, de Moraes DB,

Gonçalves GT, Teixeira LADC, Otoni Figueiró MT, Cunha T, da Silva

Lage VK, Danielewicz AL, Figueiredo PHS, et al: Handgrip strength

and menopause are associated with cardiovascular risk in women with

obesity: A cross-sectional study. BMC Womens Health. 25:1572025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Woods NF and Mitchell ES: Symptoms during

the perimenopause: Prevalence, severity, trajectory, and

significance in women's lives. Am J Med. 118(Suppl 12B): S14–S24.

2005. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Marsh WK, Templeton A, Ketter TA and

Rasgon NL: Increased frequency of depressive episodes during the

menopausal transition in women with bipolar disorder: Preliminary

report. J Psychiatr Res. 42:247–251. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Marsh WK, Ketter TA and Rasgon NL:

Increased depressive symptoms in menopausal age women with bipolar

disorder: Age and gender comparison. J Psychiatr Res. 43:798–802.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Truong D and Marsh W: Bipolar disorder in

the menopausal transition. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 21:1302019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Toffol E, Heikinheimo O and Partonen T:

Hormone therapy and mood in perimenopausal and postmenopausal

women: A narrative review. Menopause. 22:564–578. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Graziottin A and Serafini A: Depression

and the menopause: Why antidepressants are not enough? Menopause

Int. 15:76–81. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Chen H, Lu M, Lyu Q, Shi L, Zhou C, Li M,

Feng S, Liang X, Zhou X and Ren L: Mitochondrial dynamics

dysfunction: Unraveling the hidden link to depression. Biomed

Pharmacother. 175:1166562024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Khan M, Baussan Y and Hebert-Chatelain E:

Connecting dots between mitochondrial dysfunction and depression.

Biomolecules. 13:6952023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Rezin GT, Amboni G, Zugno AI, Quevedo J

and Streck EL: Mitochondrial dysfunction and psychiatric disorders.

Neurochem Res. 34:1021–1029. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Iwata K: Mitochondrial involvement in

mental disorders; energy metabolism, genetic, and environmental

factors. Methods Mol Biol. 1916:41–48. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Jou SH, Chiu NY and Liu CS: Mitochondrial

dysfunction and psychiatric disorders. Chang Gung Med J.

32:370–379. 2009.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Beikoghli Kalkhoran S and Kararigas G:

Oestrogenic regulation of mitochondrial dynamics. Int J Mol Sci.

23:11182022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

No authors listed. Research on the

menopause in the 1990s. Report of a WHO scientific group. World

Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 866:1–107. 1996.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Schmidt PJ, Roca CA, Bloch M and Rubinow

DR: The perimenopause and affective disorders. Semin Reprod

Endocrinol. 15:91–100. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

No authors listed. Clinical challenges of

perimenopause: Consensus opinion of the North American menopause

society. Menopause. 7:5–13. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Gordon JL, Girdler SS, Meltzer-Brody SE,

Stika CS, Thurston RC, Clark CT, Prairie BA, Moses-Kolko E, Joffe H

and Wisner KL: Ovarian hormone fluctuation, neurosteroids, and HPA

axis dysregulation in perimenopausal depression: A novel heuristic

model. Am J Psychiatry. 172:227–236. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Santoro N, Epperson CN and Mathews SB:

Menopausal symptoms and their management. Endocrinol Metab Clin

North Am. 44:497–515. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Cheng MH, Lee SJ, Wang SJ, Wang PH and Fuh

JL: Does menopausal transition affect the quality of life? A

longitudinal study of middle-aged women in Kinmen. Menopause.

14:885–890. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Jia Y, Zhou Z, Xiang F, Hu W and Cao X:

Global prevalence of depression in menopausal women: A systematic

review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 358:474–482. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Badawy Y, Spector A, Li Z and Desai R: The

risk of depression in the menopausal stages: A systematic review

and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 357:126–133. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Oppermann K, Fuchs SC, Donato G, Bastos CA

and Spritzer PM: Physical, psychological, and menopause-related

symptoms and minor psychiatric disorders in a community-based

sample of Brazilian premenopausal, perimenopausal, and

postmenopausal women. Menopause. 19:355–360. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Li RX, Ma M, Xiao XR, Xu Y, Chen XY and Li

B: Perimenopausal syndrome and mood disorders in perimenopause:

Prevalence, severity, relationships, and risk factors. Medicine

(Baltimore). 95:e44662016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Soares CN and Taylor V: Effects and

management of the menopausal transition in women with depression

and bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 68(Suppl 9): S16–S21.

2007.

|

|

30

|

Timur S and Sahin NH: The prevalence of

depression symptoms and influencing factors among perimenopausal

and postmenopausal women. Menopause. 17:545–551. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Freeman EW: Associations of depression

with the transition to menopause. Menopause. 17:823–827. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Ye B, Zhou Y, Chen M, Chen C, Tan J and Xu

X: The association between depression during perimenopause and

progression of chronic conditions and multimorbidity: Results from

a Chinese prospective cohort. Arch Womens Ment Health. 26:697–705.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Marsh WK, Ketter TA, Crawford SL, Johnson

JV, Kroll-Desrosiers AR and Rothschild AJ: Progression of female

reproductive stages associated with bipolar illness exacerbation.

Bipolar Disord. 14:515–526. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Bromberger JT, Matthews KA, Schott LL,

Brockwell S, Avis NE, Kravitz HM, Everson-Rose SA, Gold EB, Sowers

M and Randolph JF Jr: Depressive symptoms during the menopausal

transition: The Study of women's health across the nation (SWAN). J

Affect Disord. 103:267–272. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Krajewska-Ferishah K, Kułak-Bejda A,

Szyszko-Perłowska A, Shpakou A, Van Damme-Ostapowicz K and

Chatzopulu A: Risk of depression during menopause in women from

Poland, Belarus, Belgium, and Greece. J Clin Med. 11:33712022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Kulkarni J, Gavrilidis E, Hudaib AR,

Bleeker C, Worsley R and Gurvich C: Development and validation of a

new rating scale for perimenopausal depression-the Meno-D. Transl

Psychiatry. 8:1232018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Bromberger JT and Kravitz HM: Mood and

menopause: Findings from the study of women's health across the

nation (SWAN) over 10 years. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am.

38:609–625. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Chen MH, Su TP, Li CT, Chang WH, Chen TJ

and Bai YM: Symptomatic menopausal transition increases the risk of

new-onset depressive disorder in later life: A nationwide

prospective cohort study in Taiwan. PLoS One. 8:e598992013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Bromberger JT, Kravitz HM, Chang Y,

Randolph JF Jr, Avis NE, Gold EB and Matthews KA: Does risk for

anxiety increase during the menopausal transition? Study of women's

health across the nation. Menopause. 20:488–495. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Hogervorst E, Craig J and O'Donnell E:

Cognition and mental health in menopause: A review. Best Pract Res

Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 81:69–84. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Pertesi S, Coughlan G, Puthusseryppady V,

Morris E and Hornberger M: Menopause, cognition and dementia-a

review. Post Reprod Health. 25:200–206. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Sochocka M, Karska J, Pszczołowska M,

Ochnik M, Fułek M, Fułek K, Kurpas D, Chojdak-Łukasiewicz J,

Rosner-Tenerowicz A and Leszek J: Cognitive decline in early and

premature menopause. Int J Mol Sci. 24:65662023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Coborn J, de Wit A, Crawford S, Nathan M,

Rahman S, Finkelstein L, Wiley A and Joffe H: Disruption of Sleep

continuity during the perimenopause: Associations with female

reproductive hormone profiles. J Clin Endocrinol Metab.

107:e4144–e4153. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Baker FC, de Zambotti M, Colrain IM and

Bei B: Sleep problems during the menopausal transition: Prevalence,

impact, and management challenges. Nat Sci Sleep. 10:73–95. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Zhou Q, Wang B, Hua Q, Jin Q, Xie J, Ma J

and Jin F: Investigation of the relationship between hot flashes,

sweating and sleep quality in perimenopausal and postmenopausal

women: The mediating effect of anxiety and depression. BMC Womens

Health. 21:2932021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Aras SG, Grant AD and Konhilas JP:

Clustering of >145,000 symptom logs reveals distinct pre, peri,

and menopausal phenotypes. Sci Rep. 15:6402025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Cray LA, Woods NF, Herting JR and Mitchell

ES: Symptom clusters during the late reproductive stage through the

early postmenopause: Observations from the seattle midlife women's

health study. Menopause. 19:864–869. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Eberling JL, Wu C, Tong-Turnbeaugh R and

Jagust WJ: Estrogen- and tamoxifen-associated effects on brain

structure and function. Neuroimage. 21:364–371. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Bromberger JT, Schott LL, Kravitz HM,

Sowers M, Avis NE, Gold EB, Randolph JF Jr and Matthews KA:

Longitudinal change in reproductive hormones and depressive

symptoms across the menopausal transition: Results from the study

of women's health across the nation (SWAN). Arch Gen Psychiatry.

67:598–607. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Musial N, Ali Z, Grbevski J, Veerakumar A

and Sharma P: Perimenopause and first-onset mood disorders: A

closer look. Focus (Am Psychiatr Publ). 19:330–337. 2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Turek J and Gąsior Ł: Estrogen

fluctuations during the menopausal transition are a risk factor for

depressive disorders. Pharmacol Rep. 75:32–43. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

He L, Guo W, Qiu J, An X and Lu W: Altered

spontaneous brain activity in women during menopause transition and

its association with cognitive function and serum estradiol level.

Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 12:6525122021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Meinhard N, Kessing LV and Vinberg M: The

role of estrogen in bipolar disorder, a review. Nord J Psychiatry.

68:81–87. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Wharton W, Gleason CE, Olson SRMS,

Carlsson CM and Asthana S: Neurobiological underpinnings of the

estrogen-mood relationship. Curr Psychiatry Rev. 8:247–256. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Newhouse P and Albert K: Estrogen, stress,

and depression: A neurocognitive model. JAMA Psychiatry.

72:727–729. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Simpkins JW, Yang SH, Sarkar SN and Pearce

V: Estrogen actions on mitochondria-physiological and pathological

implications. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 290:51–59. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Metcalf CA, Duffy KA, Page CE and Novick

AM: Cognitive problems in perimenopause: A review of recent

evidence. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 25:501–511. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Crandall CJ, Larson JC, Ensrud KE, LaCroix

AZ, Guthrie KA, Reed SD, Bhasin S and Diem S: Are serum estrogen

concentrations associated with menopausal symptom bother among

postmenopausal women? Baseline results from two MsFLASH clinical

trials. Maturitas. 162:23–30. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Zhang Z, DiVittorio JR, Joseph AM and

Correa SM: The effects of estrogens on neural circuits that control

temperature. Endocrinology. 162:bqab0872021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Amin Z, Canli T and Epperson CN: Effect of

estrogen-serotonin interactions on mood and cognition. Behav Cogn

Neurosci Rev. 4:43–58. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Rubinow DR, Schmidt PJ and Roca CA:

Estrogen-serotonin interactions: Implications for affective

regulation. Biol Psychiatry. 44:839–850. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Regidor PA: Progesterone in peri-and

postmenopause: A review. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 74:995–1002.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Memi E, Pavli P, Papagianni M, Vrachnis N

and Mastorakos G: Diagnostic and therapeutic use of oral micronized

progesterone in endocrinology. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 25:751–772.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Cao G, Meng G, Zhu L, Zhu J, Dong N, Zhou

X, Zhang S and Zhang Y: Susceptibility to chronic immobilization

stress-induced depressive-like behaviour in middle-aged female mice

and accompanying changes in dopamine D1 and GABAA

receptors in related brain regions. Behav Brain Funct. 17:22021.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

65

|

Crowley SK, O'Buckley TK, Schiller CE,

Stuebe A, Morrow AL and Girdler SS: Blunted neuroactive steroid and

HPA axis responses to stress are associated with reduced sleep

quality and negative affect in pregnancy: A pilot study.

Psychopharmacology (Berl). 233:1299–1310. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Sanna E, Talani G, Busonero F, Pisu MG,

Purdy RH, Serra M and Biggio G: Brain steroidogenesis mediates

ethanol modulation of GABAA receptor activity in rat hippocampus. J

Neurosci. 24:6521–6530. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Hantsoo L, Jagodnik KM, Novick AM, Baweja