Introduction

Knee osteoarthritis (KOA), a progressive

degenerative joint disorder characterized by articular cartilage

degradation, synovial inflammation and osteophyte formation, is a

leading cause of age-associated mobility disability (1,2).

Epidemiological projections suggest OA prevalence will double by

2030 compared with the levels in the 2010s, reflecting global

demographic shifts toward aging populations (3). Studies suggest that chondrocyte

senescence, a terminal cell cycle arrest state, drives OA

progression (4,5). Senolytic elimination of senescent

chondrocytes preserves cartilage integrity in murine post-traumatic

OA models (6,7), while intra-articular injection of

senescent cells induces OA pathology (8). Mechanistically, senescent

chondrocytes exhibit high levels of senescence-associated secretory

phenotype (SASP) proteins, including MMPs, pro-inflammatory

cytokines and reactive oxygen species (ROS), which collectively

promote extracellular matrix (ECM) degradation and chronic

synovitis (9,10). However, the upstream molecular

mechanisms governing chondrocyte senescence remain incompletely

understood, hindering targeted OA therapy development.

Mitophagy, a selective autophagic process essential

for mitochondrial quality control, serves a key role in age-related

pathology research (11). OA

chondrocytes exhibit impaired mitophagic activity, leading to

pathological accumulation of dysfunctional mitochondria (12-14). This degradation mechanism is

notably suppressed in senescent cells and associated with abnormal

mitochondrial retention and elevated ROS generation (15). Notably, restoring mitophagic flux

attenuates cell senescence markers (16), while mitophagy activation reduces

oxidative stress in OA pathogenesis (17). These findings establish

mitochondrial homeostasis disruption as a key link between

chondrocyte senescence and OA progression.

PTEN-induced putative kinase 1 (PINK1), a master

regulator of mitochondrial quality control, serves critical roles

in age-related pathologies including Parkinson's disease and

cardiac hypertrophy (18,19).

PINK1 orchestrates mitochondrial homeostasis by phosphorylating

ubiquitin chains at Ser65 to recruit Parkin, initiating

ubiquitin-dependent clearance of damaged mitochondria (20). It also phosphorylates

mitochondrial Tu translation elongation factor (TUFm) at Ser222,

inhibiting autophagy-related 5-12 complex formation and suppressing

non-canonical mitophagy (21).

The role of PINK1 in chondrocyte senescence and K OA pathogenesis

remains controversial: While Shin et al (22) reported that PINK1-mediated

mitophagy contributes to cartilage degeneration, other studies

(23,24) have demonstrated that PINK1/Parkin

pathway activation exerts chondroprotective effects through

enhanced mitochondrial quality control. This paradox highlights

context-dependent regulatory functions of PINK1, potentially

influenced by disease stage and microenvironmental factors,

necessitating further mechanistic investigation.

The present study aimed to clarify PINK1-mediated

mitophagy in chondrocyte senescence during OA progression. Using

lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced inflammatory models, the PINK1

modulation effects on mitochondrial function, redox homeostasis and

senescence-related phenotypes were investigated. RNA-sequencing

(seq) with functional validation was performed to identify the

downstream effectors of PINK1, particularly its interaction with

the p38 MAPK/NF-κB signaling axis. The present findings may advance

molecular stratification of OA pathogenesis and establish a

framework for mitochondria-targeted therapy.

Materials and methods

Mouse model generation

A total of 20 male C57BL/6J mice (weight, 25±2 g;

age, 6 weeks) were purchased from Jiangsu Huachuang Xinnuo

Pharmaceutical Technology Co., Ltd. All experimental procedures

were approved by The Animal Ethics Committee of Nanjing University

of Chinese Medicine (Nanjing, China; approval no. 202409A051).

Animals were housed under specific pathogen-free conditions (25°C,

50% relative humidity) with a 12/12-h light/dark cycle, free access

to food and water and ≤5 mice/cage. Using SPSS software (IBM Corp.;

version 22.0), the mice were randomly assigned to the control or

the KOA model group (n=10/group). After a 7-day acclimation period,

destabilization of the medial meniscus (DMM) surgery was performed

on the right hind limb according to established methods (25). Anesthesia was induced with 3%

isoflurane and maintained with 1% isoflurane during surgery. The

surgical area was shaved and disinfected with 75% ethanol, and a

medial approach to the knee joint was used. After blunt layered

separation of the muscles, the medial meniscus was transected with

a scalpel to induce joint instability and establish the KOA model.

The control group underwent a sham procedure, involving all

surgical steps except for transection of the medial meniscus. All

animals were given a 14-day postoperative recovery period to ensure

model establishment. The animal experiment lasted a total of 3

weeks (7 days of acclimatization and 14 days for KOA model

induction). During this period, animals exhibiting severe decline

in mobility, difficulty moving or inability to access food and

water, indicative of extreme debilitation, were designated for

early euthanasia. No unexplained deaths occurred. Euthanasia was

performed by intraperitoneal injection of sodium pentobarbital (150

mg/kg). Death was confirmed based on the absence of spontaneous

respiration for >2 min, no palpable heartbeat, no response to

resuscitation and fixed dilated pupils with loss of the light

reflex. The knee joints were dissected and articular cartilage

specimens were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C

for subsequent analysis.

Micro-computed tomography scanning

Micro-CT scanning (Skyscan; Bruker Corporation) was

performed on knee joint samples. The scanning parameters included a

voltage of 80 kV, current of 100 μA and resolution of 9

μm. The scan region was focused on the subchondral bone area

beneath the tibial plateau in the weight-bearing zone.

Subsequently, CTVox 3.3, Blue Scientific) to perform

three-dimensional reconstruction of the knee joint and conduct

structure model index of trabeculae) and bone volume fraction)

analyses to assess its structural characteristics.

Histological observation

Articular cartilage from the knee joint was

collected and fixed at room temperature in 4% paraformaldehyde for

48 h. The tissue was then decalcified in 10% EDTA) solution at

37°C. After paraffin embedding at 65°C, sections were prepared at a

thickness of 0.4 μm. The sections were stained at room

temperature with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and with Safranin

O-Fast Green (SO/FG). H&E staining was performed with

hematoxylin for 5-10 min and counterstain cytoplasm with eosin for

1-3 min. For SO/FG staining, with Fast Green for 5 min, then stain

with Safranin O for 30 min. The knee articular cartilage was

examined under a light microscope. OA Research Society

International (OARSI) score (26) was calculated to assess

pathological degeneration.

ELISA

The concentrations of pro-inflammatory cytokines,

including IL-1β, IL-6 and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), in serum

samples were quantified using commercially available mouse-specific

ELISA kits according to the manufacturers' instructions [Mouse

IL-1β (cat. no. MLB00C), IL-6 (cat. no. M6000B) and TNF-α ELISA kit

(cat. no. MTA00B; all R&D Systems, Inc.)]. Briefly, serum

samples were collected by centrifugation of whole blood at 3,000 ×

g for 10 min at 4°C and stored at −80°C until analysis. Standards

and samples were added to pre-coated 96-well plates in duplicate

and incubated for 2 h at room temperature. After washing five times

with wash buffer, biotinylated detection antibodies were added for

1 h at room temperature. The optical density was measured at 450

nm. Cytokine concentrations were calculated based on standard

curves generated for each assay. All samples were analyzed in

triplicate to ensure data reliability.

Cell isolation and culture

Immortalized human chondrocytes (SV40 cells; cat.

no. T0021) were purchased from Applied Biological Materials, Inc.

For primary cell culture, articular cartilage was aseptically

isolated from the tibial plateau and washed three times with PBS.

The cleaned cartilage fragments were minced into 1 mm3

pieces and digested in 0.2% type II collagenase at 37°C for 6 h

with gentle agitation. The cell suspension was filtered through a

70-μm cell strainer and centrifuged at 300 × g for 6 min at

room temperature to isolate chondrocytes. The harvested cells were

cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (both

Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and 1%

penicillin/streptomycin (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.) under standard culture conditions (37°C, 5% CO2

and 95% humidity). Medium replacement was performed every 48 h

until 80-90% confluence was achieved. KOA conditions were modeled

by treating cells with 10 ng/ml IL-1β or 10 ng/ml TNF-α for 24 h;

or 1 μg/ml LPS for 24 h. For inhibition of the p38 MAPK

pathway, chondrocytes were treated with 1 μM talmapimod for

24 h. To activate the p38 MAPK signaling pathway, chondrocytes were

treated with 1 μg/ml diprovocim for 24 h. All treatments

were performed at 37°C.

PINK1 short hairpin (sh)RNA

transfection

shRNA designs were sourced from Sigma-Aldrich

website (27). Based on the

PINK1 gene (transcript ID: NM_032409.1), three shRNAs were

designed: TRCN0000007101 (PINK1-interference1) targeting

5'-CGGCTGGAGGAGTATCTGATA-3'), TRCN0000199193 (PINK1-i2) targeting

GAAGCCACCATGCCTACATTG and TRCN0000199446 (PINK1-i3) targeting

CGGACGCTGTTCCTCGTTATG-3'). Negative control) plasmid

(NC-interference) targeted TTCTCCGAACGTGTCACGTT (5'->3'). The

oligonucleotides (oligos) were designed using the stem-loop (loop)

sequence TCAAGAG The specific interference sequences are listed in

Table I. A third-generation

lentiviral system was used for transduction (lentiviral transfer

plasmid, packaging plasmid, and envelope plasmid are mixed at a

4:3:1 ratio (12:9:3 μg), employing a puromycin-resistant

lentiviral shRNA transfer vector and 293T packaging cells (both

Nanjing Kress Biotechnology Co., Ltd.). Transfection was performed

at 37°C using Lipo293™ (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology; cat.

no. C0521) for 6 h, followed by a medium change 24 h

post-transfection. Viral supernatants were collected at 24 and 48 h

post-transfection, filtered through a 0.45 μm sterile

filter, concentrated and purified using a PEG Lentivirus

Purification kit (Chongqing Inovogen Biotechnology Co., Ltd.; cat.

no. P1201), then resuspended in DMEM. Aliquots of 200

μl/tube were prepared and stored at −80°C. Infection was

performed at an MOI of 70 at 37°C for 24 h, followed by selection

with 2 μg/ml puromycin for 48 h. Cells were then switched to

puromycin-free DMEM (Gibco, cat. no. 11965092.) for expansion, and

assessed knockdown efficiency using FITC labelling observed by

fluorescence microscopy and quantitative PCR (qPCR). qPCR was

performed on a LightCycler 480 system using the SYBR Green I Master

kit (Roche, cat. no. 04887352001). Primer sequences (5'→3') were as

follows: human PINK1 (forward: GCCTCATCGAGGAAAAACAGG; reverse:

GATCACTAGCCAGGGAACACG) and the housekeeping gene human GAPDH

(forward: GGAGCGAGATCCCTCCAAAAT; reverse: GGCTGTTGTCATACTTCTCATGG).

Thermal cycling conditions were as follows: initial denaturation at

95°C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 sec, 60°C for

30 sec (annealing), and 72°C for 30 sec. Relative gene expression

was calculated using the 2^-ΔΔCq method (28), normalized to GAPDH, and reported

as fold change relative to the control group. TRCN0000199446 was

selected as the shRNA interference sequence for subsequent

experiments.

| Table IInterference sequences for PINK1

short hairpin RNA and empty vector plasmid. |

Table I

Interference sequences for PINK1

short hairpin RNA and empty vector plasmid.

| Name | Sequence

(5'->3') |

|---|

| NC-iF |

gatccgTTCTCCGAACGTGTCACGTTtcaagagAACGTGACACGTTCGGAGAAtttttt |

| NC-iR |

aattaaaaaaTTCTCCGAACGTGTCACGTTctcttgaAACGTGACACGTTCGGAGAAcg |

| PINK1-i1F |

gatccgCGGCTGGAGGAGTATCTGATAtcaagagTATCAGATACTCCTCCAGCCGtttttt |

| PINK1-i1R |

aattaaaaaaCGGCTGGAGGAGTATCTGATActcttgaTATCAGATACTCCTCCAGCCGcg |

| PINK1-i2F |

gatccGAAGCCACCATGCCTACATTGtcaagagCAATGTAGGCATGGTGGCTTCtttttt |

| PINK1-i2R |

aattaaaaaaGAAGCCACCATGCCTACATTGctcttgaCAATGTAGGCATGGTGGCTTCg |

| PINK1-i3F |

gatccgCGGACGCTGTTCCTCGTTATGtcaagagCATAACGAGGAACAGCGTCCGtttttt |

| PINK1-i3R |

aattaaaaaaCGGACGCTGTCCTCGTTATG ctcttga

CATAACGAGGAACAGCGTCCGcg |

Lentiviral transduction for PINK1

overexpression in primary mouse chondrocytes

For PINK1 overexpression, PINK1 gene oligos (IDs

B5469-1-38) were designed and amplified by Shanghai GenePharma Co.,

Ltd. and transduction was performed using a third-generation

lentiviral system. The control group received an empty-vector virus

with no insert, using the LV5 (EF-1aF/GFP&Puro) backbone. For

the overexpression group, the transcript ID was NM_026880.2 and the

same LV5 (EF-1aF/GFP&Puro) vector was used. The packaging

plasmids included pGag/Pol, pRev and the envelope plasmid pVSV-G.

All vectors/plasmids were supplied by Shanghai GenePharma Co., Ltd.

Packaging was performed in 293T producer cells (Shanghai GenePharma

Co., Ltd.). Cells were transfected at 37°C using the RNAi-mate

transfection reagent (Shanghai Genepharma Co., Ltd.) for 6 h, after

which the medium was replaced with DMEM containing 10% FBS. The

culture was maintained at 37°C for 72 h to collect viral

supernatant. Cell debris was removed by low-speed centrifugation at

4°C, 500 × g for 4 min, followed by filtration through a 0.45

μm sterile filter. Finally, the virus was concentrated by

ultracentrifugation at 4°C, 3,000 × g for 2 h, aliquoted, and

stored at −80°C. Primary mouse chondrocytes were used as target

cells. Infection was performed at an MOI of 90 at 37°C for 24 h,

followed by puromycin selection at 2 μg/ml for 48 h. The

cells were then expanded in puromycin-free medium for subsequent

assays. Lentiviral transfer plasmid, packaging and envelope plasmid

are mixed at a 4:3:1 ratio (12:9:3 μg).

RNA-seq

RNA quality and concentration were assessed using a

NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.)

and an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Inc.), with

RNA integrity number >8.0 considered acceptable for sequencing.

mRNA bearing poly (A) tails was enriched from 1-4 μg of

total RNA using 20 μl Dynabeads Oligo (dT)25 magnetic beads

(Invitrogen, cat. no. 61002). The mRNA was then fragmented into

200-300 bp short fragments by incubating at 94°C for 5 min in a

divalent cation-containing fragmentation buffer with the NEBNext

Magnesium RNA Fragmentation Module (New England Biolabs, cat. no.

E6150S). First-strand cDNA was synthesized using random hexamer

primers (50 μM; Invitrogen, cat. no. N8080127) and

SuperScript III reverse transcriptase (200 U/μl; both

Invitrogen, cat. no. 18080093) under the following conditions: 25°C

for 10 min, 50°C for 50 min, and inactivation at 85°C for 5 min.

Second-strand cDNA synthesis was performed with DNA Polymerase I

(10 U/μl; NEB, cat. no. M0209L) and RNase H (2 U/μl;

NEB, cat. no. M0297S) in a second-strand synthesis buffer

containing dNTPs (10 mM each), incubated at 16°C for 2.5 h. The

double-stranded cDNA was purified, end-repaired and ligated with

sequencing adapters. Libraries were constructed using the NEBNext

Ultra RNA Library Prep kit (cat. no. E7530L, New England BioLabs,

Inc.) and subjected to quality control using the Agilent 2100

Bioanalyzer. Final library concentrations were quantified by qPCR

and diluted to 150 pM. High-quality libraries were sequenced on an

Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform (Illumina, Inc.) in paired-end mode

(150 bp reads). Raw sequencing data were preprocessed using FastQC

(v0.11.9) for quality assessment and Trimmomatic (v0.39) for

adapter trimming and low-quality base removal. Clean reads were

aligned to the reference genome (GRCh38) using HISAT2 (v2.2.1) and

gene expression levels were quantified using StringTie

(v2.2.1).

Transcriptome data analysis

Pearson correlation analysis were performed using

the cor()' function in R (version 4.3.0, The R Foundation for

Statistical Computing). Pearson's correlation coefficients (r) were

calculated for normally distributed continuous variables, while

Spearman rank correlation was used for nonparametric data. The

'corrplot' package (version 0.92, Comprehensive R Archive Network),

combined with hierarchical clustering, was used to visualize the

correlation matrix. Two-sided tests were applied, with P<0.05

indicating statistical significance, and Benjamini-Hochberg

correction was used for multiple comparisons. Principal component

analysis (PCA) was conducted with the 'prcomp()' function. Prior to

analysis, sampling adequacy was assessed with the

Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin test (threshold >0.6), and variable

correlations were evaluated with Bartlett's test of sphericity

(P<0.05). The number of principal components was determined

based on eigenvalues >1 (Kaiser criterion) and the scree plot.

The 'factoextra' package (version 1.0.7, Comprehensive R Archive

Network)) was used to generate biplots showing both sample scores

and variable loadings. The first two principal components (PC1 and

PC2) explaining the cumulative variance were selected for

visualization. Stability of the results was validated with 1,000

bootstrap iterations. Differential gene expression analysis was

performed using DESeq2 (1.40.2, Bioconductor Project), with a

significance threshold of |log2 fold-change|>1 and adjusted

P<0.05. Functional enrichment analysis of differentially

expressed genes was performed using Gene Ontology (GO, https://www.geneontology.org/) and Kyoto Encyclopedia

of Genes and Genomes (KEGG, genome.jp/kegg/) databases. Gene set

enrichment analysis was performed using the GSEA software (version

4.3.2, Broad Institute) in conjunction with the Molecular

Signatures Database (MSigDB v7.5.1, Broad Institute). A pre-ranked

gene list was generated based on log2 fold-change values from

differential expression analysis. The Hallmark gene sets (H) were

used for the analysis.

ROS

According to the manufacturer's instructions, the

intracellular levels of ROS were quantitatively measured using an

ROS Assay kit (cat. no. S0035M; Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology). Briefly, chondrocytes were plated in 6-well culture

plates at a density of 1×106 cells/well and allowed to

adhere overnight at 37°C. Culture medium was replaced with fresh

DMEM (Gibco, cat. no. 11965092) containing the ROS-specific

fluorescent probe working solution, and the cells were maintained

at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator for 30 min.

Cells were washed three times with PBS to remove excess probe

solution and stained with DAPI for 10 min at 37°C. Fluorescence

imaging for ROS detection was performed using an inverted

fluorescence microscope (Leica DMI8; Leica Microsystems GmbH)

equipped for excitation at 488 nm. All procedures were conducted

under standardized conditions to ensure consistency and

reproducibility of the results.

Measurement of mitochondrial membrane

potential

According to the manufacturer's instructions,

mitochondrial membrane potential changes were analyzed using the

Mitochondrial Membrane Potential Assay kit with JC-1 (Beyotime

Institute of Biotechnology). Chondrocytes were seeded at a density

of 1×106 cells/well in 6-well plates and incubated with

DMEM containing JC-1 working solution at 37°C for 20 min.

Fluorescence images were captured using a fluorescence microscope

(Leica DMI8; Leica Microsystems GmbH).

Senescence-associated β-galactosidase

(SA-β-gal) staining

Cell senescence was assessed using a SA-β-gal

Staining kit (cat. no. C0602; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology)

following established protocols (25). Briefly, chondrocytes were rinsed

twice with PBS and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min at room

temperature. Cells were incubated with freshly prepared staining

solution containing X-gal in a humidified 37°C incubator for 16 h

under CO2-free conditions. Quantification was performed

by calculating the percentage of SA-β-gal-positive cells relative

to total cells in five randomly selected fields of view/sample

using ImageJ software (v1.54f, National Institutes of Health).

Protein extraction and western

blotting

Cells were lysed using RIPA buffer (Beyotime

Institute of Biotechnology) supplemented with a protease inhibitor

cocktail on ice for 30 min. The lysates were centrifuged at 12,000

× g for 15 min at 4°C, and the supernatants were collected. Protein

concentration was measured using the BCA protein assay. Equal

amounts of protein (20 μg/lane) were separated by 4-20%

SDS-PAGE and transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride membranes

(MilliporeSigma). The membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat milk

for 1 h at room temperature and incubated overnight at 4°C with the

following primary antibodies: GAPDH (1:50,000; cat. no.

66004-1-Ig), β-tubulin (1:3,000; cat. no. 10094-1-AP), p65 (cat.

no. 10745-1-AP), phosphorylated (p-)p65 (cat. no. 82335-1-RR), p38

(cat. no. 14064-1-AP), p-p38 (all Proteintech Group, Inc.; cat. no.

28796-1-AP), MMP-3 (Affinity Biosciences; cat. no. AF0217), iNOS

(inducible nitric oxide synthase) (cat. no. 18985-1-AP), P16 (both

Proteintech Group, Inc.; cat. no. 10883-1-AP), P21 (Affinity

Biosciences; cat. no. AF6290), PINK1 (cat. no. 23274-1-AP), TUFm

(cat. no. 26730.1.AP), BNIP3L (Bcl-2) interacting protein 3-like)

(cat. no. 12986-1-AP), p62 (cat. no. 18420-1-AP) and LC3B

(Microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3B) (all 1:1,000; all

Proteintech Group, Inc.; cat. no. 18725.1-AP). Following washing

three times with 0.1% TBST, the membranes were incubated with

horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies for 1 h at

room temperature. The secondary antibodies were HRP-conjugated Goat

Anti-Rabbit IgG (H+L) (cat. no. SA00001-2, Proteintech Group, Inc.)

and HRP-conjugated Goat Anti-Mouse IgG (H+L) (both 1:5,000; cat.

no. SA00001-1, Proteintech Group, Inc.). Chemiluminescent detection

was performed with SuperSignal West Pico PLUS substrate (Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.; cat. no. 34580). Protein bands were

visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescence detection system

(cat. no. 1708265, Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.) and analyzed using

ImageJ software (v1.53t, National Institutes of Health). All

experiments were performed in triplicate to ensure

reproducibility.

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as the mean ± standard

deviation of ≥3 independent experimental repeats for continuous

variables. Between-group comparisons were performed using one-way

ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test or Bonferroni correction.

P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference. All analyses and data visualization were conducted

using GraphPad Prism 5 (Dotmatics).

Results

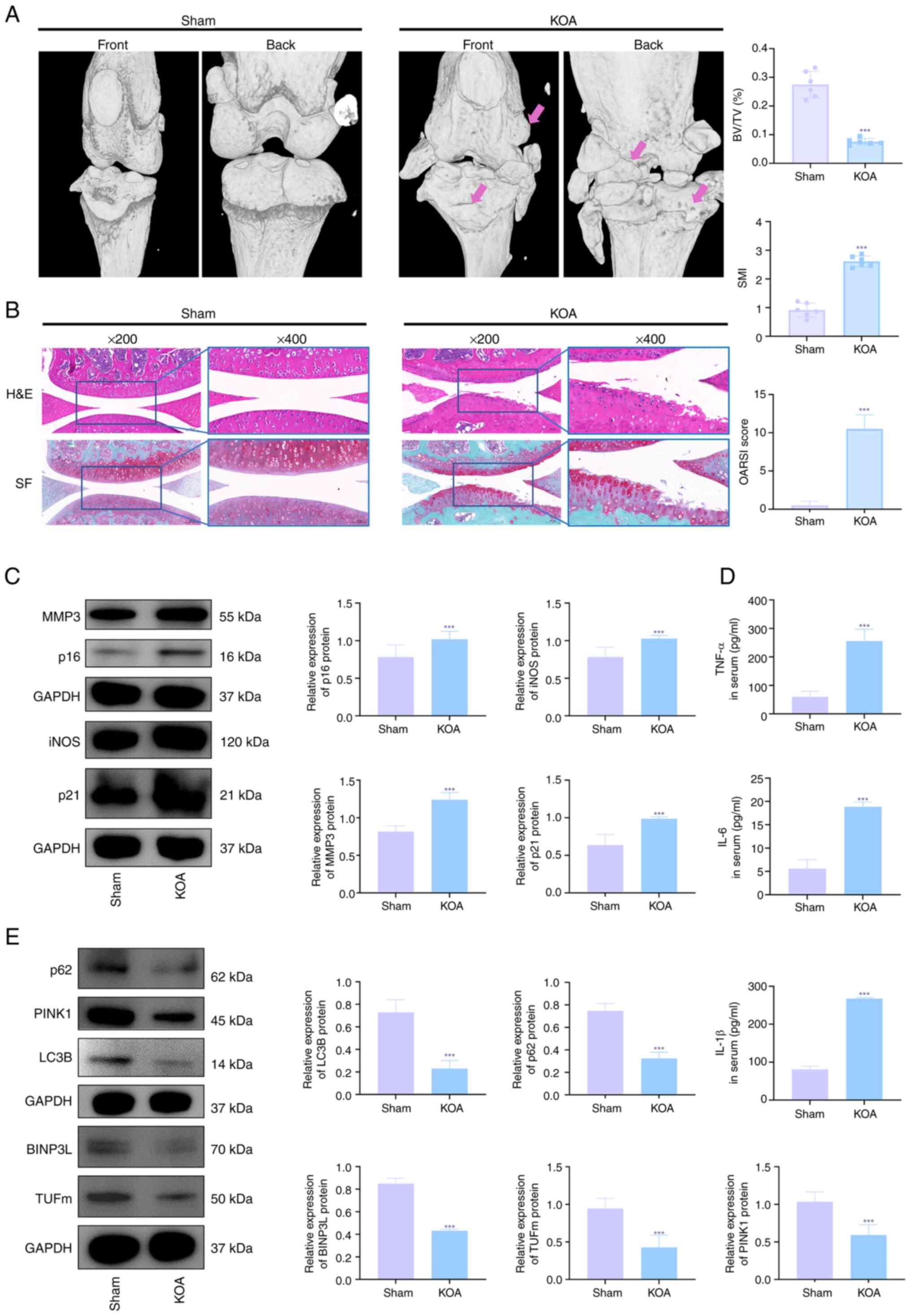

Impaired mitochondrial autophagy and

enhanced cell senescence in KOA cartilage

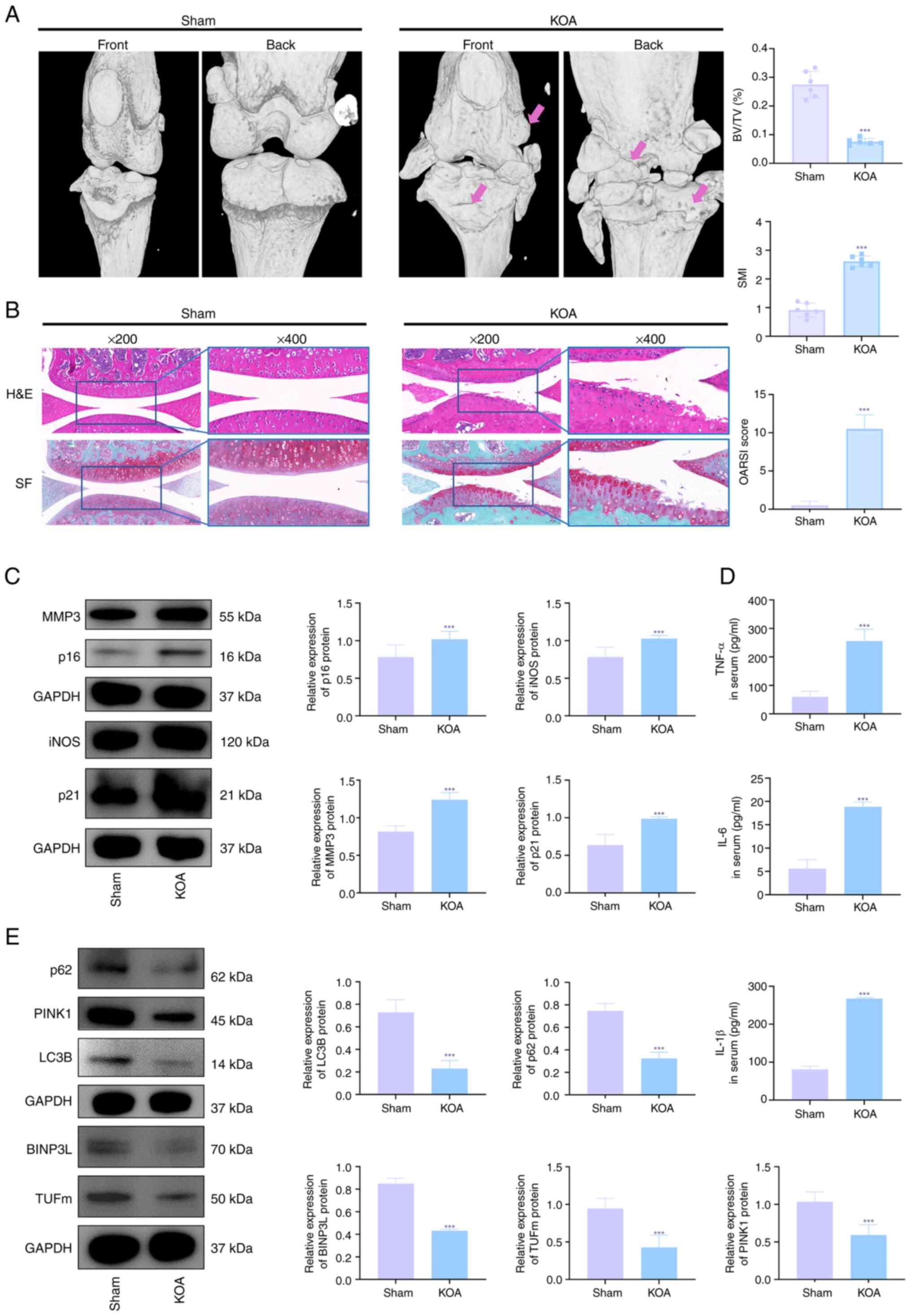

Micro-CT analysis confirmed the successful

establishment of the KOA model. Compared with the sham-operated

group, the KOA group showed a significant increase in osteophyte

formation and more severe cartilage surface wear (Fig. 1A). Calculations of bone volume

fraction and the structure model index of trabeculae showed that

bone destruction was more pronounced in the KOA group than in the

sham group (Fig. 1A).

Histopathological evaluation revealed notable changes in the KOA

group, characterized by marked chondrocyte loss, a posterior shift

of the tidemark, and damage to the superficial cartilage structure.

Further assessment to evaluate cartilage degeneration showed that

the OARSI scores were significantly increased in the KOA group

(Fig. 1B). Quantitative ELISA

revealed significantly elevated levels of the pro-inflammatory

cytokines IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α in KOA compared with sham animals

(Fig. 1C). Western blot analysis

demonstrated a decline in mitophagy regulators (PINK1, TUFm, NIX,

p62 and LC3) concomitant with upregulation of senescence-associated

proteins (MMP3, iNOS, p21 and p16) in KOA cartilage compared with

sham tissue (Fig. 1D). These

protein alterations were conserved at the transcriptional level, as

evidenced by qPCR showing parallel modulation of corresponding mRNA

expression patterns (Fig. 1E).

Collectively, these findings demonstrated KOA progression is

mechanistically linked to impaired mitochondrial clearance and

exacerbated chondrocyte senescence in articular cartilage.

| Figure 1Impaired mitochondrial autophagy and

enhanced cell senescence in KOA cartilage. (A) Representative

microcomputed tomography 3D reconstructions of knee joints from

sham-operated and destabilization of the Medial Meniscus)induced

KOA mice 14 days post-surgery. (B) Histopathological evaluation and

OARSI scoring of knee joint sections (n=6), stained with HE and SF.

Scale bar, 50 μm. (C) Western blot analysis and densitometry

of senescence-associated markers (MMP3, iNOS, p21, p16) in

cartilage, normalized to GAPDH (n=3). (D) Serum levels of

proinflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β) measured by ELISA

using samples collected via cardiac puncture (n=6). (E) Western

blot analysis and densitometry of mitophagy-related proteins

(PINK1, LC3B ratio, p62, BNIP3L, TUFm) in cartilage, normalized to

GAPDH (n=3). ***P<0.001 vs. sham. KOA, knee

osteoarthritis; HE, hematoxylin and eosin; TNF-α, tumor necrosis

factor-α; PINK1, PTEN-induced putative kinase 1; TUFm, Tu

translation elongation factor; OARSI, Osteoarthritis Research

Society International; SO/FG, Safranine O-Fast Green; iNOS,

inducible nitric oxide synthase; BNIP3L, BCL2-interacting Protein 3

Like; SMI, structure model index of trabeculae; BV/TV, bone volume

fration. |

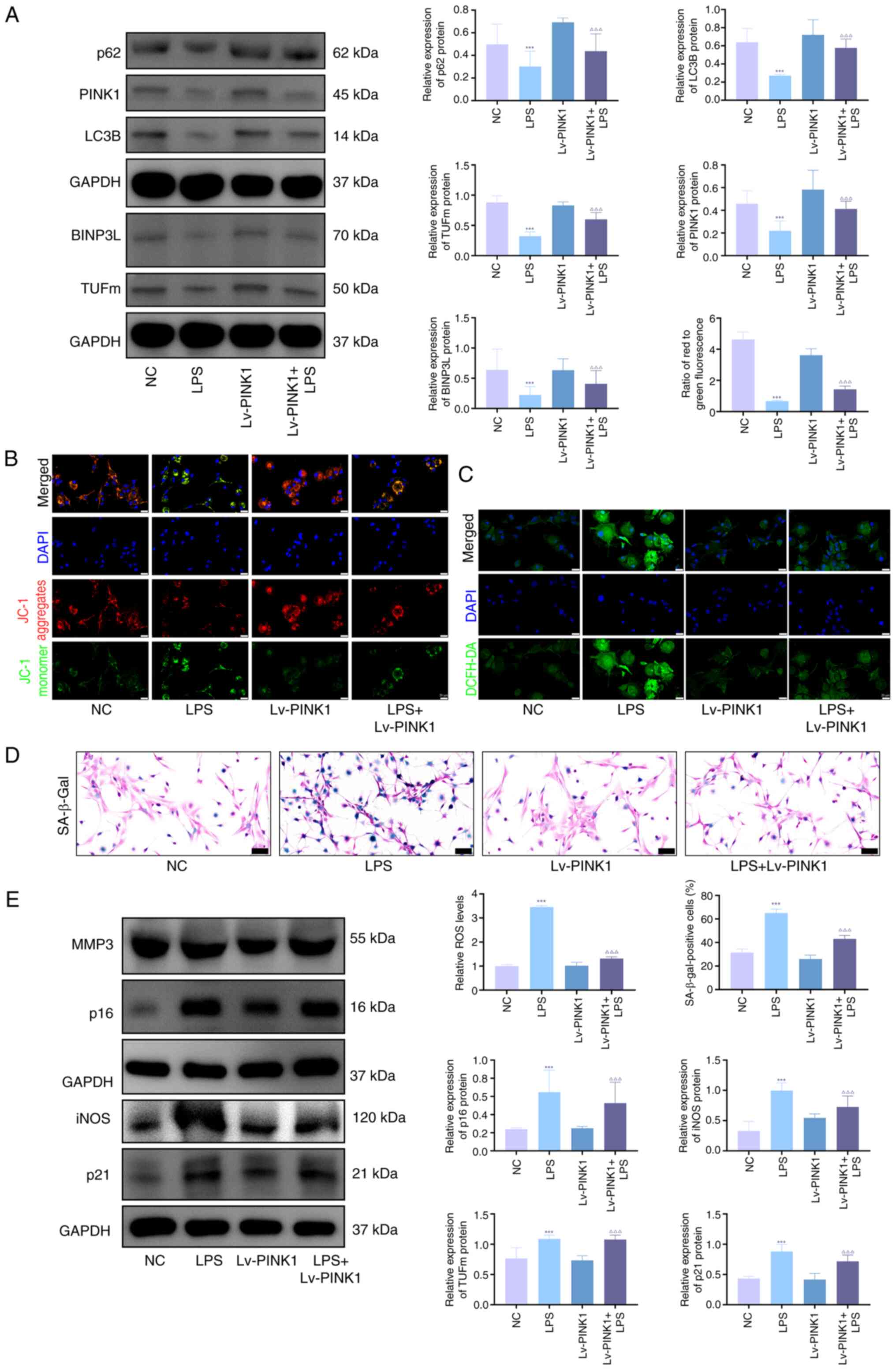

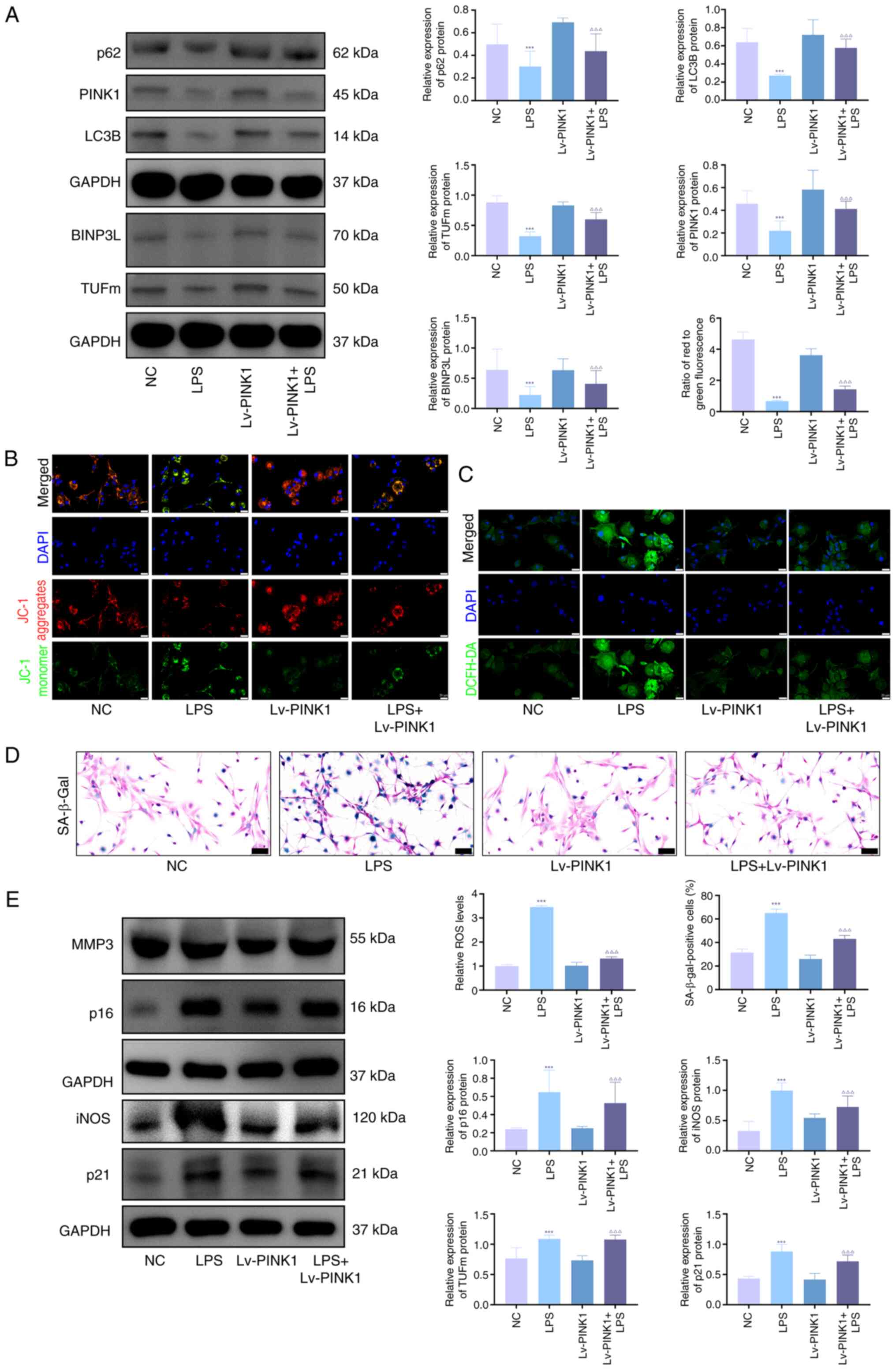

PINK1 overexpression decreases senescence

and promotes mitophagy in chondrocytes

In vitro, LPS, IL-1β and TNF-α significantly

upregulated the protein expression levels of the

senescence-associated markers p21, p16, iNOS and MMP3 (Fig. S1A), and increased the proportion

of SA-β-gal-positive cells (Fig.

S1B). To investigate the role of PINK1 in LPS-stimulated

chondrocytes, overexpression was performed using adenoviral

transfection. Western blot analysis revealed significant

upregulation of mitophagy-associated proteins (PINK1, TUFm, BINPL,

p62 and LC3B) in KOA chondrocytes compared with NC, which was

markedly reversed by Lv-PINK1 infection (Fig. 2A). JC-1 and ROS fluorescence

quantification demonstrated impaired mitochondrial membrane

potential and elevated ROS levels in KOA chondrocytes relative to

NC (Fig. 2B and C), both of

which were significantly ameliorated by Lv-PINK1 treatment.

SA-β-gal staining showed a significant increase in senescent

chondrocytes during KOA progression compared with blank controls,

with Lv-PINK1 infection decreasing senescence markers (Fig. 2D). Western blot analysis

confirmed decreased levels of senescence-associated proteins (MMP3,

iNOS, p21 and p16) following PINK1 overexpression (Fig. 2E). These coordinated changes

demonstrated that enhancing PINK1-mediated mitophagy mitigated

chondrocyte senescence through restored mitochondrial quality

control under inflammatory stress.

| Figure 2PINK1 overexpression decreases

senescence and promotes mitophagy in chondrocytes. (A) Western blot

analysis and densitometric quantification of mitophagy markers

(PINK1, LC3B, p62, BNIP3L, TUFm) in primary mouse chondrocytes

following transduction with Lv-PINK1, followed by LPS treatment (1

μg/ml, 24 h). Protein signals were normalized to GAPDH. (B)

Mitochondrial membrane potential was assessed using JC-1 staining.

Red, healthy mitochondria (J-aggregates); green, depolarized

mitochondria (J-monomers). (C) Levels of intracellular ROS were

detected using the DCFH-DA probe. Green fluorescence intensity was

quantified in ≥100 cells/group. Scale bar, 20 μm. (D)

Cellular senescence (blue) was evaluated by SA-β-gal staining. The

percentage of SA-β-gal-positive cells was quantified (scale bar, 50

μm). (E) Western blot quantification of

senescence-associated secretory phenotype markers (MMP3, iNOS) and

cell cycle inhibitors (p21, p16). Protein signals were normalized

to GAPDH. n=3. ***P<0.001 vs. NC;

∆∆∆P<0.001 vs. LPS. PINK1, PTEN-induced putative

kinase 1; TUFm, Tu translation elongation factor; ROS, reactive

oxygen species; SA-β-gal, senescence-associated β-galactosidase;

LPS, lipopolysaccharide; BNIP3L, BCL2-interacting Protein 3 Like;

Lv, Lentiviral Vector; iNOS, inducible nitric oxide synthase; NC,

negative Control. |

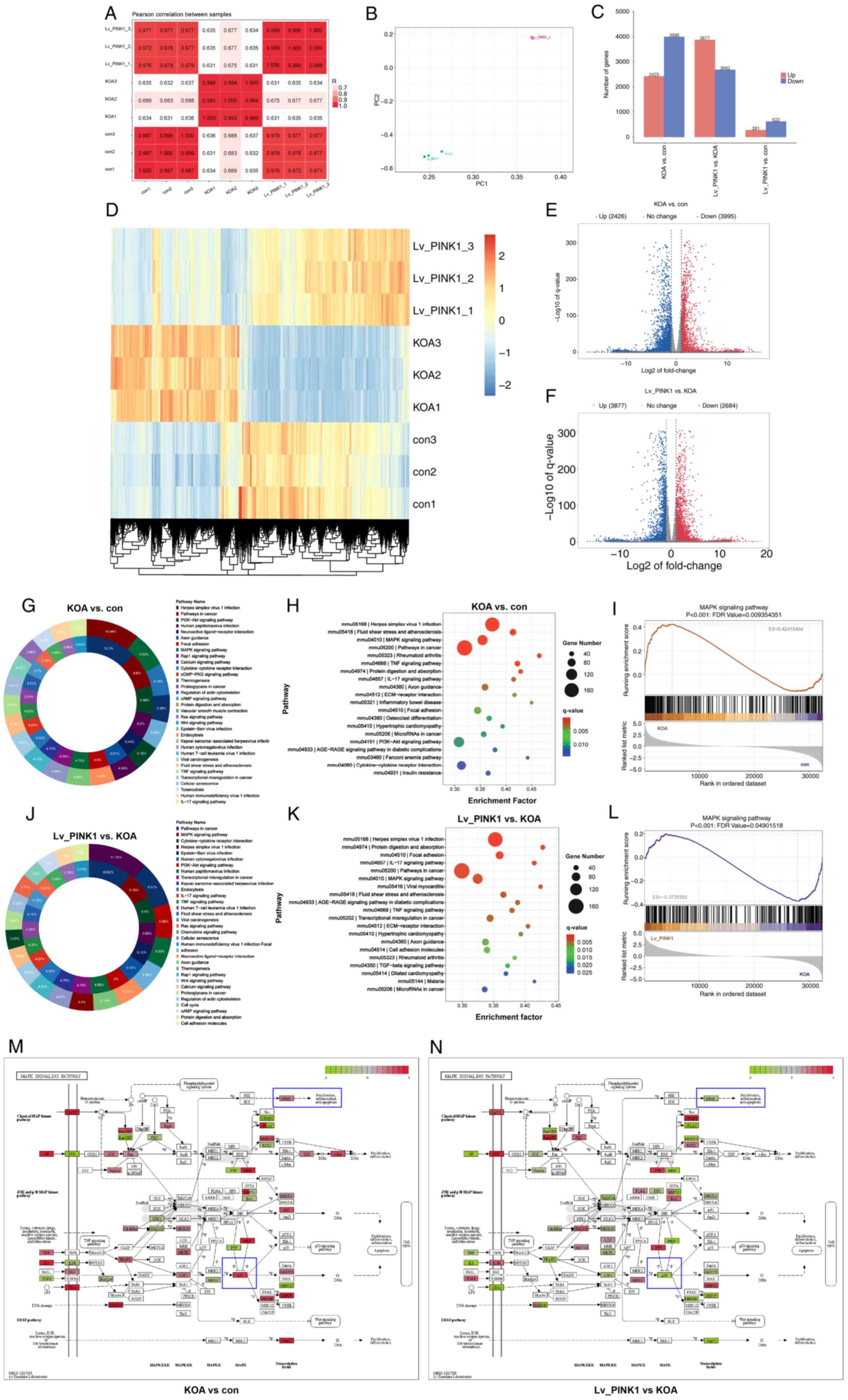

Transcriptomic analysis of PINK1

overexpression in OA chondrocytes

RNA-seq of chondrocytes revealed the anti-senescence

mechanism of PINK1. Correlation (Fig. 3A) and principal component

analysis (Fig. 3B) demonstrated

distinct clustering between KOA and control groups, while

Lv-PINK1-infected chondrocytes exhibited transcriptional profiles

comparable with controls. There were 6,420 dysregulated genes in

KOA vs. controls (2,425 up- and 3,995 downregulated), with Lv-PINK1

intervention altering 6,559 transcripts (3,877 up and 2,682

downregulated; Fig. 3C and D).

The volcano plots using criteria of |log2FC|>1 and P<0.05

confirmed these genome-wide alterations. KEGG pathway analysis

(Fig. 3G and J) and scatter

plots (Fig. 3H and K)

highlighted the top 10 pathways and revealed that 'MAPK signaling

pathway', 'TNF signaling pathway' and 'IL-17 signaling pathway'

were associated with KOA. Lv-PINK1 treatment predominantly

modulated 'focal adhesion' and 'IL-17 signaling pathway'. GSEA;

Fig. 3I and L) confirmed the

involvement of the MAPK signaling pathway in KOA development and

its modulation by Lv-PINK1. Changes in MAPK pathway genes (Fig. 3M and N) showed that p38

expression was increased during KOA but decreased by Lv-PINK1

infection. These multi-omics findings demonstrated that PINK1

overexpression may mitigate chondrocyte senescence and maintain

mitochondrial function via regulation of the MAPK signaling

pathway.

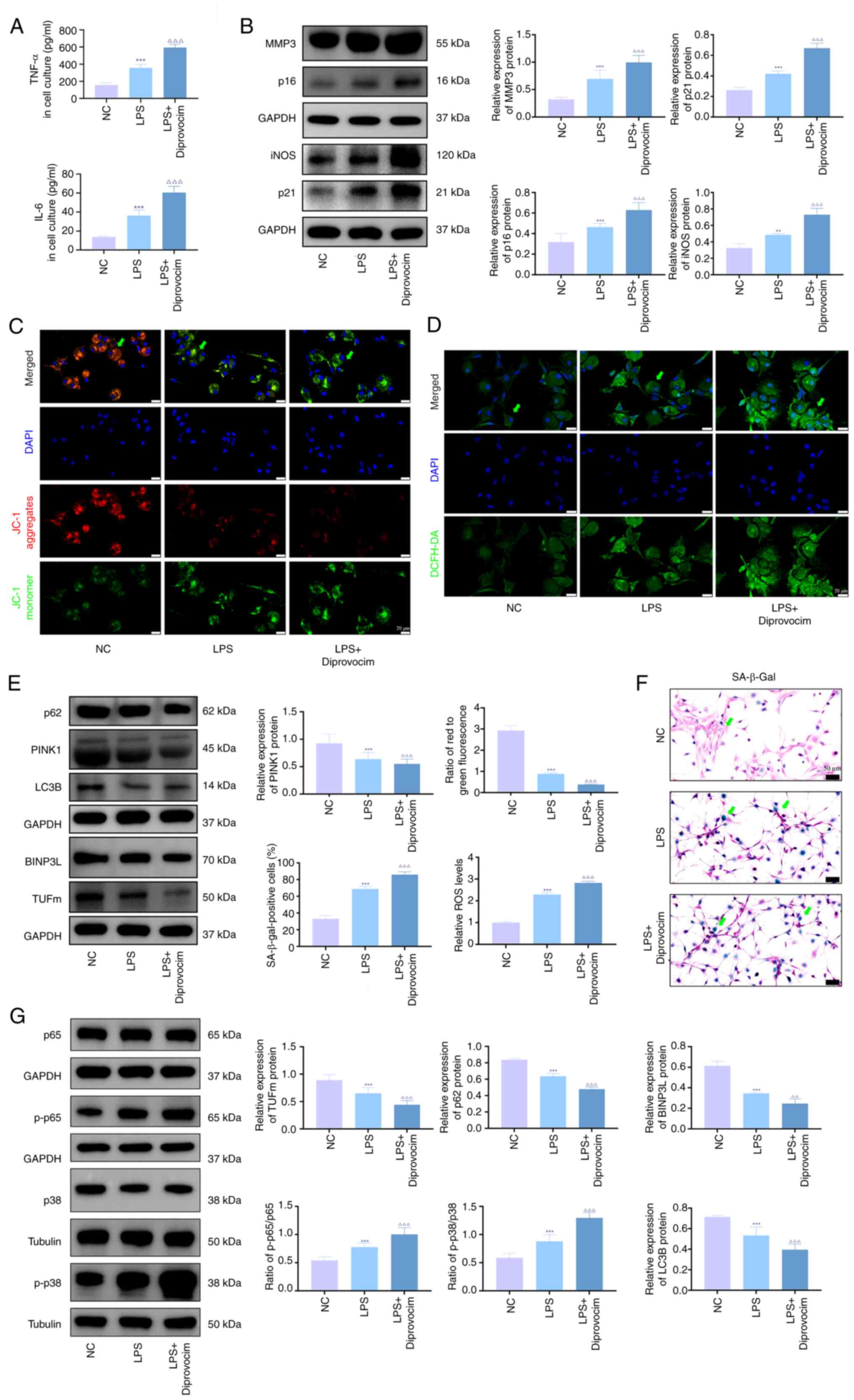

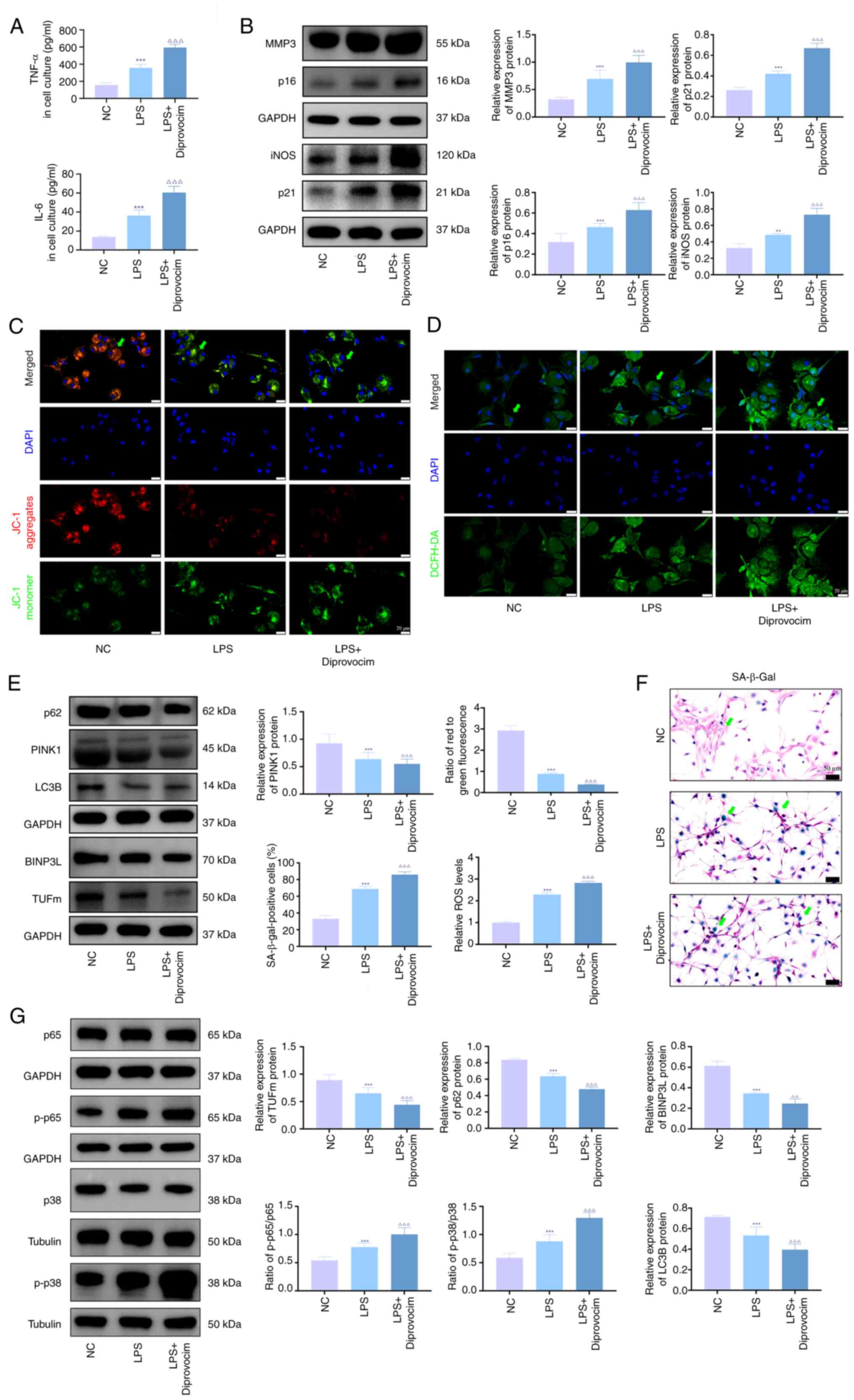

Activation of the p38 MAPK/NF-κB pathway

induces senescence and mitochondrial damage in LPS-treated

chondrocytes

To validate the transcriptomic findings, diprovocim,

a TLR (Toll like receptors)7/8 agonist that indirectly activates

p38 MAPK and NF-κB pathways, was used to investigate its effects on

KOA chondrocytes. ELISA demonstrated that diprovocim significantly

elevated IL-6 and TNF-α levels in the culture medium (Fig. 4A). Western blotting (Fig. 4B) confirmed that diprovocim

upregulated the expression of mitophagy-(PINK1, TUFm, BNIP3L, p62

and LC3B) and senescence-associated proteins (MMP3, iNOS, p21 and

p16), while promoting phosphorylation of p38 MAPK and NF-κB.

SA-β-gal staining revealed a marked increase in senescent cells

following diprovocim treatment (Fig.

4F). JC-1 staining (Fig. 4C)

and ROS assays (Fig. 4D) further

indicated decreased mitochondrial membrane potential and elevated

ROS accumulation in treated chondrocytes.

| Figure 4Activation of the p38 MAPK/NF-κB

pathway induces senescence and mitochondrial damage in LPS-treated

chondrocytes. (A) ELISA was performed to detect the levels of TNF-α

and IL-6 in the culture medium of immortalized human chondrocytes.

(B) Western blotting was performed to detect the protein expression

of MMP3, iNOS, p21 and p16 in immortalized human chondrocytes.

Representative (C) JC-1 staining showing mitochondrial membrane

potential in immortalized human chondrocytes. (D) DCFH-DA staining

showing ROS levels in immortalized human chondrocytes. (E) Western

blotting was performed to detect the protein expression of PINK1,

LC3B, p62, BINPL and TUFm in immortalized human chondrocytes. (F)

Representative SA-β-Gal staining showing senescence levels in each

group of immortalized human chondrocytes. (G) Western blotting was

performed to detect the protein expression levels of p-p65, p65,

p-p38 and p38. n=3. **P<0.01,

***P<0.001 vs. sham; ∆∆∆P<0.001 vs.

LPS. LPS, lipopolysaccharide; ROS, reactive oxygen species; PINK1,

PTEN-induced putative kinase 1; TUFm, Tu translation elongation

factor; SA-β-gal, senescence-associated β-galactosidase; iNOS,

inducible nitric oxide synthase; p-, phosphorylated; BINP3L, BCL2

Interacting Protein 3 Like. |

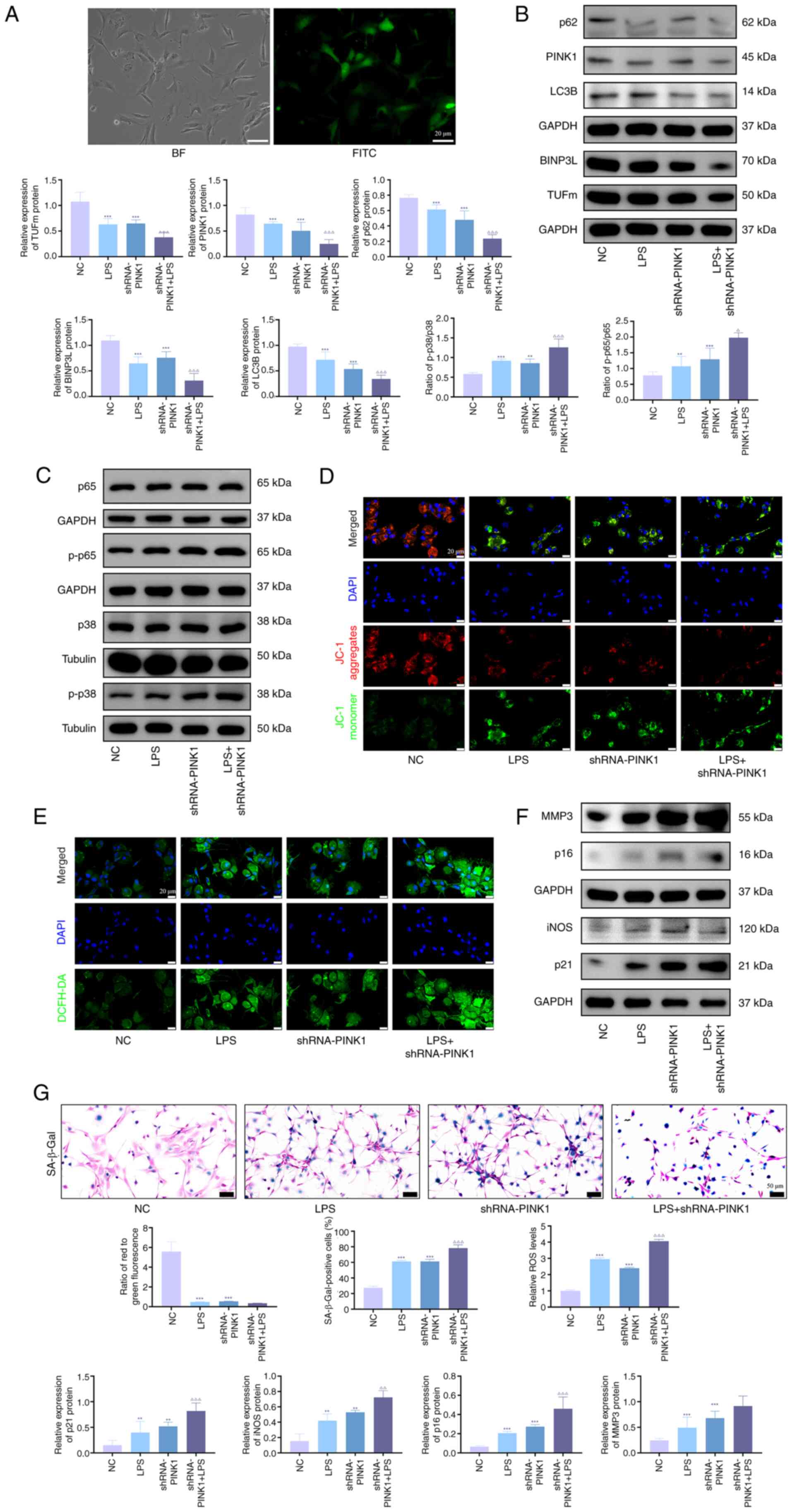

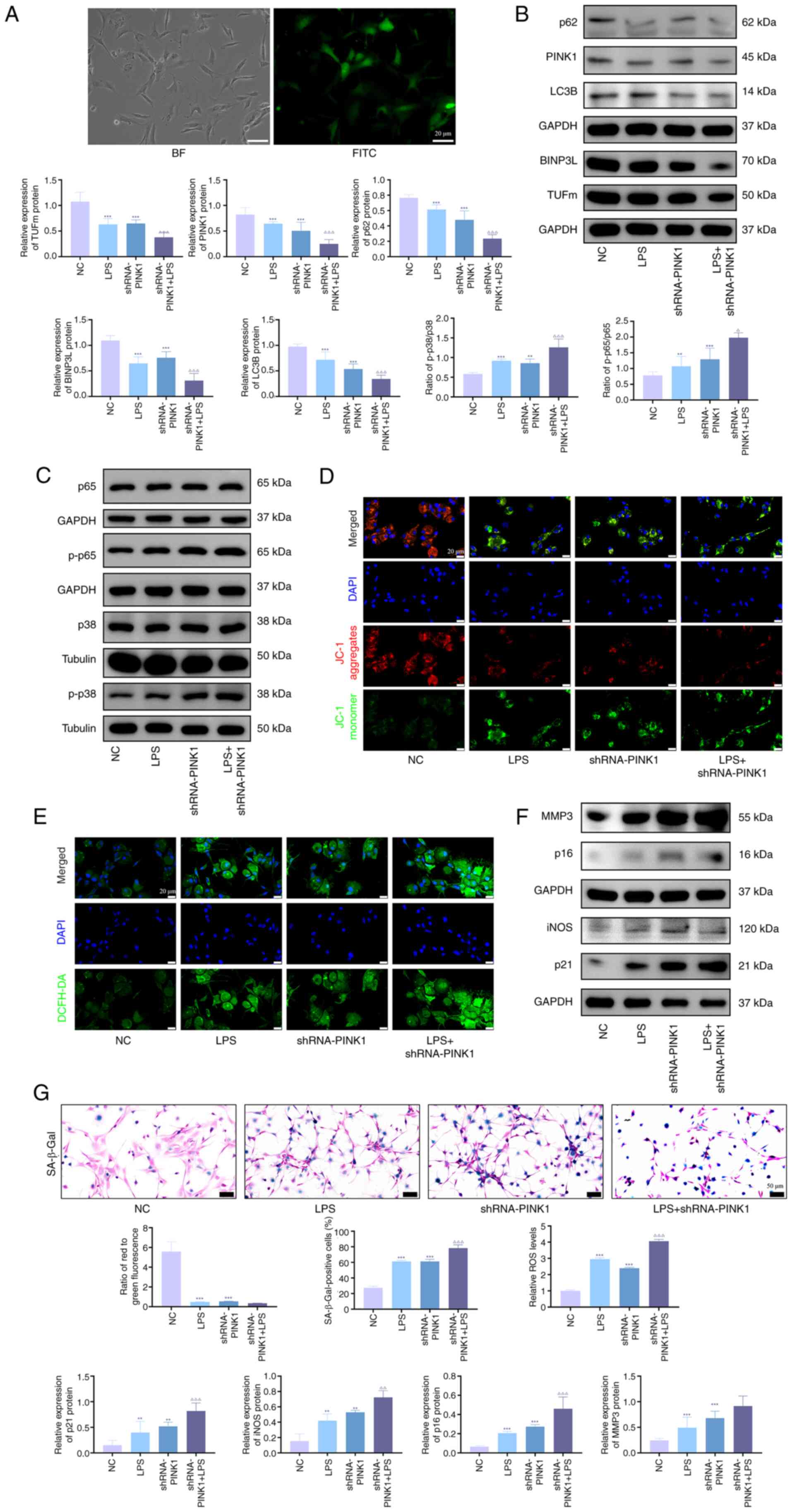

PINK1 gene knockdownenhances p38

MAPK/NF-κB phosphorylation and exacerbates chondrocyte

senescence

To validate the preliminary findings, PINK1

knockdown models in KOA chondrocytes were established to

investigate the activation of the p38 MAPK/NF-κB pathway and cell

senescence progression. Successful shRNA transfection was

demonstrated (Fig. 5A). Western

blot analysis demonstrated that PINK1 deficiency significantly

elevated phosphorylation levels of p38 MAPK and NF-κB compared with

the control (Fig. 5B). In

addition, senescence-associated proteins (MMP3, iNOS, p21 and p16)

were upregulated (Fig. 5C),

whereas mitochondrial autophagy markers (PINK1, TUFm, NIX, p62 and

LC3B) exhibited downregulation (Fig.

5D). LPS stimulation exacerbated these phenotypical alterations

and SA-β-gal staining revealed a pronounced increase in senescent

cells following PINK1 knockdown, particularly in LPS-treated cells

(Fig. 5E). JC-1 assays

demonstrated diminished mitochondrial membrane potential (Fig. 5F), while ROS quantification

confirmed elevated oxidative stress in PINK1-deficient cells

(Fig. 5G).

| Figure 5PINK1 gene knockdown enhances p38

MAPK/NF-κB phosphorylation and exacerbates chondrocyte senescence.

(A) Adenoviral infection efficiency of immortalized human

chondrocytes observed under a fluorescence microscope. Western blot

analysis of (B) PINK1, LC3B, p62, BINPL and TUFm and (C) p-p65,

p65, p-p38 and p38 protein expression. Representative (D) JC-1

staining showing mitochondrial membrane potential and (E) DCFH-DA

staining showing ROS levels in immortalized human chondrocytes. (F)

Western blot analysis of MMP3, iNOS, p21 and p16 protein expression

in immortalized human chondrocytes. (G) Representative SA-β-Gal

staining showing senescence levels in immortalized human

chondrocytes. n=3. **P<0.01, ***P<0.001

vs. sham; ∆P<0.05, ∆∆P<0.01,

∆∆∆P<0.001 vs. LPS. PINK1, PTEN-induced putative

kinase 1; TUFm, Tu translation elongation factor; ROS, reactive

oxygen species; SA-β-Gal, senescence-associated β-galactosidase;

BINP3L, BCL2-interacting Protein 3 Like; p-, Phosphorylation; iNOS,

inducible nitric oxide synthase; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; NC,

Negative Control; sh, short hairpin; BF, Bright field. |

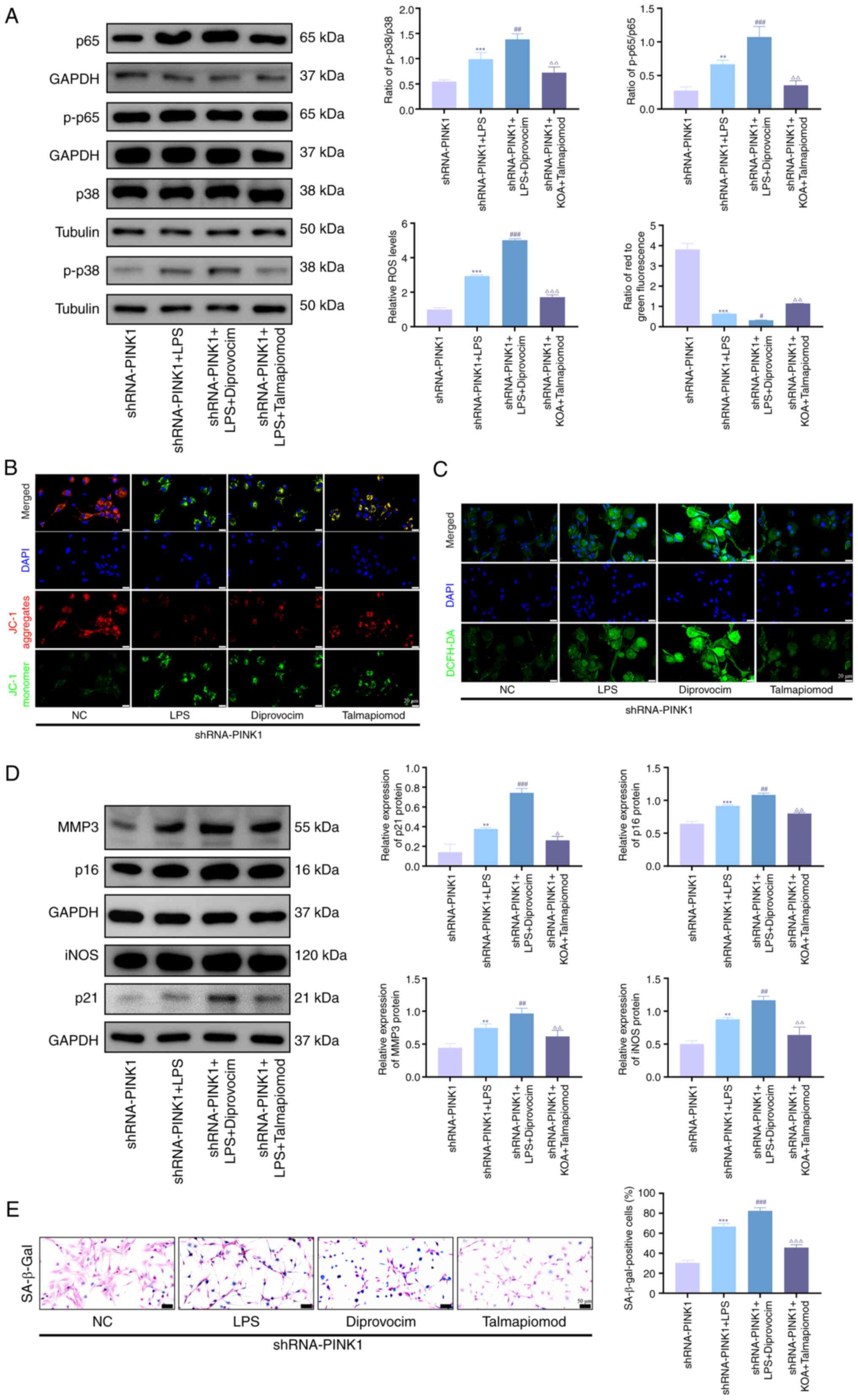

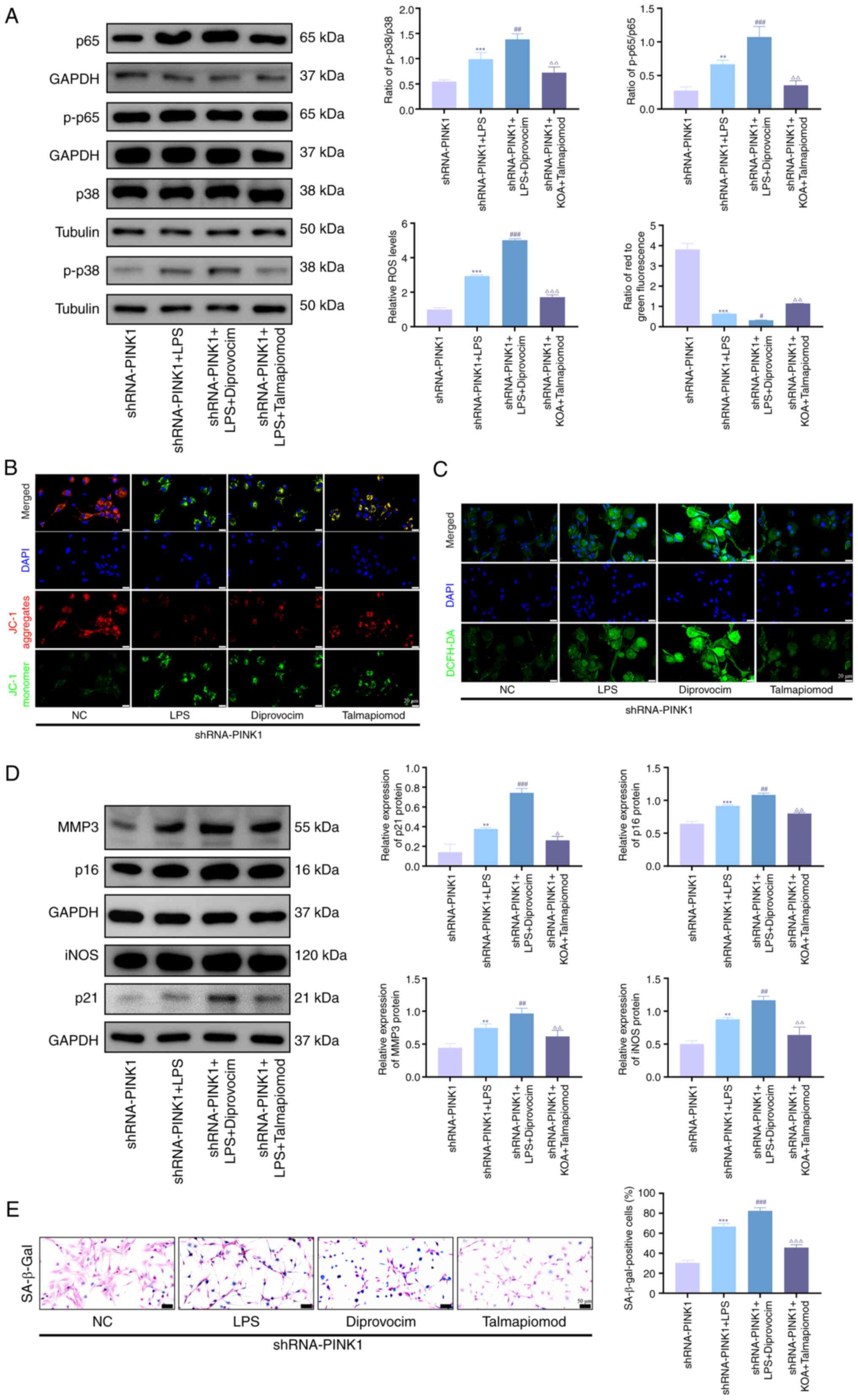

Inhibition of the p38 MAPK/NF-κB pathway

ameliorates senescence and mitochondrial damage in PINK1-silenced

chondrocytes

To investigate whether PINK1 knockdown exacerbates

chondrocyte senescence via activation of the p38 MAPK/NF-κB

pathway, talmapimod, a specific p38 MAPK inhibitor, was used in

PINK1-silenced chondrocytes to evaluate its potential therapeutic

effects. Western blot analysis demonstrated that pharmacological

inhibition of p38 MAPK significantly decreased phosphorylation

levels of both p38 MAPK and NF-κB, while upregulating

senescence-associated proteins such as MMP3, iNOS, p21 and p16

(Fig. 6A and D). By contrast,

treatment with diprovocim produced opposing effects on these

biomarkers. Consistent with these findings, SA-β-gal staining

revealed a marked decrease in senescent cells following inhibitor

treatment, whereas agonist intervention significantly increased the

proportion of senescent cells (Fig.

6E). JC-1 staining indicated that p38 MAPK activation restored

mitochondrial membrane potential and markedly decreased ROS

accumulation (Fig. 6B and C).

Collectively, these results suggested modulation of the p38

MAPK/NF-κB pathway exerted regulatory effects on chondrocyte

senescence through the maintenance of mitochondrial homeostasis.

These results collectively indicated that compromised

PINK1-mediated mitophagy exacerbated mitochondrial dysfunction and

promoted cellular senescence under inflammatory conditions,

potentially via activation of the p38 MAPK/NF-κB pathway.

| Figure 6Inhibition of p38 MAPK/NF-κB pathway

ameliorates senescence and mitochondrial damage in PINK1-silenced

chondrocytes. (A) Western blot analysis of protein expression of

p-p65, p65, p-p38 and p38. (B) Representative JC-1 assay showing

mitochondrial membrane potential and (C) DCFH-DA staining showing

ROS levels, (D) Western blot analysis of protein expression of

MMP3, iNOS, p21 and p16 and (E) representative SA-β-Gal staining

showing senescence levels in immortalized human chondrocytes. n=3.

**P<0.01, ***P<0.001 vs. sham;

#P<0.05, ##P<0.01,

###P<0.001 vs. LPS; ∆P<0.05,

∆∆P<0.01, ∆∆∆P<0.001 vs. diprovocim.

ROS, reactive oxygen species; PINK1, PTEN-induced putative kinase

1; SA-β-gal, senescence-associated β-galactosidase; p-,

Phosphorylation; iNOS, inducible nitric oxide synthase; sh, short

hairpin; NC, Negative Control; LPS, Lipopolysaccharide. |

Discussion

As the sole resident cells of articular cartilage,

chondrocytes serve a key role in maintaining ECM homeostasis.

However, under chronic stress or inflammation, these cells

progressively transform into a senescent phenotype, culminating in

irreversible cell cycle arrest characterized by distinct

morphological changes including enlarged and flattened cell

morphology and functional decline (9). This senescence-associated metabolic

impairment compromises cartilage structural integrity, leading to

ECM degradation and tissue degeneration. Notably, senescent

chondrocytes exhibit paradoxical biological activity through

sustained secretion of proinflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6 and

TNF-α), MMPs and other catabolic mediators, as a phenomenon

collectively termed the SASP (29). The SASP propagates senescence via

paracrine signaling, disrupts ECM biosynthesis and activates

matrix-degrading enzymes, creating a self-amplifying loop that

accelerates cartilage destruction. Clinical evidence reveals

elevated senescence biomarkers, including telomere shortening and

increased senescent cell burden, in joint tissue of young patients

with post-traumatic OA (30).

Complementary studies demonstrate upregulation of SASP factors

across multiple articular compartments, particularly in subchondral

bone, synovium and infrapatellar fat pads (31-33). Here, male mice were used for DMM

modeling and mechanistic experiments to avoid hormone fluctuations

from the estrous cycle in females, which can confound inflammatory

phenotypes and metabolic endpoints. This approach enhances internal

consistency and decreases variability. The present study

corroborated the aforementioned clinical observations, showing

significant upregulation of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors p16

and p21 alongside marked elevation of serum IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α

levels compared with control groups. This multisystemic

manifestation of senescence markers across articular tissue

underscores the systemic nature of cell aging in K OA

pathogenesis.

The molecular mechanisms underlying cell senescence

have been extensively characterized, with mitochondrial dysfunction

emerging as a key determinant following Harman's free radical

theory of aging (34-36). Substantial evidence has

established that mitochondrial impairment orchestrates

intracellular ROS accumulation, disrupts adenosine triphosphate

biosynthesis and ultimately initiates cellular senescence through

defined molecular cascades (37-39). Evolutionary conservation has

equipped eukaryotic cells with sophisticated quality control

systems, including mitophagy, a selective autophagy mechanism

responsible for clearing depolarized mitochondria to preserve

organellar homeostasis (40).

Nevertheless, compromised mitophagic flux induces progressive

accumulation of dysfunctional mitochondria, culminating in

bioenergetic collapse and accelerated chondrocyte senescence. The

present study systematically investigated this mitophagy-senescence

axis through multimodal validation. Immunoblotting demonstrated

significant decreases in PINK1 and LC3-II expression in

osteoarthritic cartilage compared with healthy donor-matched

controls. Complementary in vitro analyses using LPS-induced

senescence models revealed mitochondrial membrane potential

dissipation accompanied by notable ROS elevation vs. untreated

chondrocytes. These mechanistically interlinked findings

substantiate impaired mitochondrial quality control as a

pathognomonic feature of K OA-associated chondrocyte senescence,

consistent with a prior demonstration of mitophagic failure in this

pathology (25).

PINK1 serves as a key regulator of mitophagy,

operating through both canonical and non-canonical molecular

pathways. In the canonical pathway, PINK1 orchestrates

mitochondrial quality control by phosphorylating ubiquitin chains

at Ser65 residues, thereby recruiting parkin to initiate

ubiquitination-mediated marking of damaged mitochondria (41,42). In vitro models of K OA

(25), demonstrated

PINK1-dependent PARKIN regulation, with specific inhibition

decreasing PARKIN expression, while PINK1 overexpression restored

physiological expression levels. These findings confirm the

essential role of the PINK1-PARKIN axis in OA pathogenesis

(23). Notably, the present

investigation revealed a novel non-canonical regulatory mechanism:

In LPS-induced senescent chondrocytes, PINK1 overexpression

upregulated TUFm expression, as determined by western blot

analysis. This finding aligns with the report by Lin et al

(21) in 293T cells, where

activated PINK1 promotes phosphorylation of TUFm at Ser222, which

hinders the formation of the Atg5-Atg12 complex, thereby

maintaining mitophagic flux homeostasis. Mechanistically, this

dual-axis regulatory mechanism explains the mechanism by which

PINK1 overexpression synchronously enhances mitochondrial clearance

efficiency while mitigating autophagic stress-induced cellular

damage.

Notably, the present study provided novel

mechanistic insights into the anti-senescence effects of PINK1

overexpression, demonstrating its dependence on suppression of the

p38 MAPK/NF-κB signaling pathway through integrated omics and

molecular analyses. Transcriptomic profiling revealed marked

upregulation of the MAPK pathway components in K OA progression,

which was attenuated by lentiviral-mediated PINK1 overexpression.

Molecular validation demonstrated elevated p38 phosphorylation

levels in KOA chondrocytes, a phenomenon exacerbated by PINK1

inhibition. This regulatory association corroborates recent

cardiovascular research where cardiac-specific PINK1 overexpression

suppressed p38 signaling activation, thereby ameliorating

pathological remodeling in heart failure models (43-45). Subsequent investigations have

revealed that PINK1 deficiency exacerbates LPS-induced pathological

cascades, characterized by ROS overproduction, aberrant activation

of the p38 MAPK/NF-κB signaling pathway and mitochondrial

dysfunction (46,47). This establishes a

self-perpetuating triad of oxidative stress, inflammatory

activation and autophagic suppression (48). Notably, pharmacological

inhibition of p38 signaling significantly ameliorated these

pathological manifestations and disrupted this degenerative cycle,

thereby underscoring the key role of PINK1 in mitigating senescence

through suppression of the p38 MAPK/NF-κB pathway. This mechanism

demonstrates cross-organ corroboration with the findings of Luo

et al (49) and Qigen

et al (50) in premature

testicular failure research, who demonstrated that p38 MAPK

mediates age- and obesity-induced Leydig cell senescence. The dual

regulatory capacity of PINK1, which simultaneously enhances

mitochondrial clearance and mitigates inflammatory stress,

positions it as a key coordinator of cell homeostasis.

Overexpression of PINK1 promotes cartilage repair

and regeneration through multiple mechanisms. As a key regulator of

mitochondrial quality control, PINK1 overexpression enhances

mitophagy in chondrocytes, clearing damaged mitochondria and

maintaining cellular energy homeostasis (51,52). Studies have shown that PINK1

activates the PARKIN-dependent mitophagy pathway, decreases the

accumulation of ROS, and inhibits chondrocyte apoptosis and matrix

degradation (25,53). PINK1 overexpression upregulates

the synthesis of type II collagen and proteoglycans, facilitating

reconstruction of the cartilage ECM (54). In addition, PINK1 modulates

inflammatory responses by lowering the expression of inflammatory

cytokines such as IL-1β and TNF-α, thereby creating a favorable

microenvironment for cartilage repair (55). These mechanisms make PINK1 a

potential therapeutic target for degenerative cartilage

disease.

PINK1-mediated mitophagy and its downstream p38

MAPK/NF-κB signaling pathway are highly conserved in mammals. This

evolutionary conservation provides a biological basis for

translating findings from animal models to human clinical

applications (56,57). The PINK1/PARKIN pathway, as a

core mechanism of mitochondrial quality control, has been shown to

play a serve role in multiple age-related diseases, including human

Parkinson's disease and cardiac disorder (58,59). These observations suggest that

the mechanism by which PINK1 alleviates chondrocyte senescence by

inhibiting the p38 MAPK/NF-κB signaling pathway, may be present in

human patients with KOA as well (60).

However, the present study had limitations and

potential constraints. First, it lacked direct validation using

human clinical samples. Although immortalized human chondrocytes

were used for in vitro experiments, these cell lines may

lose some physiological characteristics of primary chondrocytes

after multiple passages, making it difficult to reflect the true

pattern of PINK1 expression in cartilage from patients with primary

KOA and its association with disease severity. Second, the present

study primarily focused on changes in cartilage tissue, with

insufficient overall assessment of other joint tissue involved in

KOA and the whole-knee pathological changes. As KOA is a disease of

the entire joint, interactions between these tissues are key to

disease progression. In addition, the DMM model is a post-traumatic

OA model that primarily simulates secondary OA caused by mechanical

instability, which may not represent the pathophysiological

processes of age-related primary KOA, particularly with respect to

aging-associated metabolic and inflammatory mechanisms. Future

studies should integrate clinical sample analyses, extend the

observation period, increase sample size and adopt multi-species

validation strategies to evaluate the clinical value of PINK1 in

the prevention and treatment of human KOA.

In summary, the present study demonstrated that

PINK1, a critical regulator of mitophagy, significantly alleviated

the pathological changes in K OA by ameliorating chondrocyte

senescence. This effect was mediated by inhibition of the p38

MAPK/NF-κB signaling pathway. Further studies are warranted to

elucidate the detailed molecular mechanisms underlying the

regulation by PINK1 on this signaling pathway.

Supplementary Data

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be found

in the National Center for Biotechnology Information) under

accession number PRJNA1331976 or at the following URL: dataview.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/object/PRJNA1331976)

Authors' contributions

SY and PW confirm the authenticity of all the raw

data. LJ conceived and designed the study. YZ performed

experiments; JL performed experiments; ZH performed experiments; HF

performed experiments; ZH contributed to analysis and

interpretation of data; ZZ contributed to analysis and

interpretation of data; XS contributed to analysis and

interpretation of data; PW contributed to analysis and

interpretation of data. SY edited the manuscript. All authors have

read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Ethical approval was obtained from Institutional

Animal Care and Use Committee at Nanjing University of Chinese

Medicine, Nanjing, China. (approval no. 202409A051).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the National Natural Science

Foundation of China (grant no. 82104893), Jiangsu Provincial

Medical Key Discipline (Laboratory) Cultivation Unit (grant no.

JSDW202252), Clinical Medical Innovation Center for Knee

Osteoarthritis of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Jiangsu Provincial

Hospital of Chinese Medicine (grant no. Y2023zx05), Knee

Osteoarthritis Specialized Clinical Research Institute and Nanjing

University of Chinese Medicine (grant no. LCZBYJYZZ2024-003).

References

|

1

|

Arden NK, Perry TA, Bannuru RR, Bruyère O,

Cooper C, Haugen IK, Hochberg MC, McAlindon TE, Mobasheri A and

Reginster JY: Non-surgical management of knee osteoarthritis:

Comparison of ESCEO and OARSI 2019 guidelines. Nat Rev Rheumatol.

17:59–66. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Latourte A, Kloppenburg M and Richette P:

Emerging pharmaceutical therapies for osteoarthritis. Nat Rev

Rheumatol. 16:673–688. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Wallace IJ, Worthington S, Felson DT,

Jurmain RD, Wren KT, Maijanen H, Woods RJ and Lieberman DE: Knee

osteoarthritis has doubled in prevalence since the mid-20th

century. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 114:9332–9336. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Zhang X, Yang B, Xu X, Zhang Z, Tao Z,

Zhang W, Zhang Z and Zhou X: Cellular senescence in skeletal

diseases: A bibliometric analysis from 2007 to 2024. Exp Gerontol.

209:1128572025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Cao X, Luo P, Huang J, Liang C, He J, Wang

Z, Shan D, Peng C and Wu S: Intraarticular senescent chondrocytes

impair the cartilage regeneration capacity of mesenchymal stem

cells. Stem Cell Res Ther. 10:862019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Jeon OH, Kim C, Laberge RM, Demaria M,

Rathod S, Vasserot AP, Chung JW, Kim DH, Poon Y, David N, et al:

Local clearance of senescent cells attenuates the development of

post-traumatic osteoarthritis and creates a pro-regenerative

environment. Nat Med. 23:775–781. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Zhu Z, Wang C, Wei S, Wu R, Zhao W, Zhao

X, Li Y and Yang Y: Benzophenone-3 drives osteoarthritis

pathogenesis by regulating chondrocyte senescence. Chem Biol

Interact. 421:1117572025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Xu M, Bradley EW, Weivoda MM, Hwang SM,

Pirtskhalava T, Decklever T, Curran GL, Ogrodnik M, Jurk D, Johnson

KO, et al: Transplanted senescent cells induce an

osteoarthritis-like condition in mice. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med

Sci. 72:780–785. 2017.

|

|

9

|

Liu Y, Zhang Z, Li T, Xu H and Zhang H:

Senescence in osteoarthritis: From mechanism to potential

treatment. Arthritis Res Ther. 24:1742022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Wakale S, Wu X, Sonar Y, Sun A, Fan X,

Crawford R and Prasadam I: How are aging and osteoarthritis

related? Aging Dis. 14:592–604. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Palikaras K, Lionaki E and Tavernarakis N:

Mechanisms of mitophagy in cellular homeostasis, physiology and

pathology. Nat Cell Biol. 20:1013–1022. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Fang G, Wen X, Jiang Z, Du X, Liu R, Zhang

C, Huang G, Liao W and Zhang Z: FUNDC1/PFKP-mediated mitophagy

induced by KD025 ameliorates cartilage degeneration in

osteoarthritis. Mol Ther. 31:3594–3612. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Jiang N, Xing B, Peng R, Shang J, Wu B,

Xiao P, Lin S, Xu X and Lu H: Inhibition of Cpt1a alleviates

oxidative stress-induced chondrocyte senescence via regulating

mitochondrial dysfunction and activating mitophagy. Mech Ageing

Dev. 205:1116882022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Cao H, Zhou X, Xu B, Hu H, Guo J, Wang M,

Li N and Jun Z: Advances in the study of mitophagy in

osteoarthritis. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 25:197–211. 2024.In English,

Chinese. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Zhang L, Li M, Li X, Liao T, Ma Z, Zhang

L, Xing R, Wang P and Mao J: Characteristics of sensory innervation

in synovium of rats within different knee osteoarthritis models and

the correlation between synovial fibrosis and hyperalgesia. J Adv

Res. 35:141–151. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Hu S, Zhang C, Ni L, Huang C, Chen D, Shi

K, Jin H, Zhang K, Li Y, Xie L, et al: Stabilization of HIF-1α

alleviates osteoarthritis via enhancing mitophagy. Cell Death Dis.

11:4812020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Ansari MY, Khan NM, Ahmad I and Haqqi TM:

Parkin clearance of dysfunctional mitochondria regulates ROS levels

and increases survival of human chondrocytes. Osteoarthritis

Cartilage. 26:1087–1097. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

18

|

Barazzuol L, Giamogante F, Brini M and

Calì T: PINK1/Parkin mediated mitophagy, Ca2+

signalling, and ER-mitochondria contacts in Parkinson's disease.

Int J Mol Sci. 21:17722020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Zhou H, Wang X, Xu T, Gan D, Ma Z, Zhang

H, Zhang J, Zeng Q and Xu D: PINK1-mediated mitophagy attenuates

pathological cardiac hypertrophy by suppressing the mtDNA

release-activated cGAS-STING pathway. Cardiovasc Res. 121:128–142.

2025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Rakovic A, Grünewald A, Voges L, Hofmann

S, Orolicki S, Lohmann K and Klein C: PINK1-interacting proteins:

Proteomic analysis of overexpressed PINK1. Parkinsons Dis.

2011:1539792011.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Lin J, Chen K, Chen W, Yao Y, Ni S, Ye M,

Zhuang G, Hu M, Gao J, Gao C, et al: Paradoxical mitophagy

regulation by PINK1 and TUFm. Mol Cell. 80:607–620.e12. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Shin HJ, Park H, Shin N, Kwon HH, Yin Y,

Hwang JA, Song HJ, Kim J, Kim DW and Beom J: Pink1-mediated

chondrocytic mitophagy contributes to cartilage degeneration in

osteoarthritis. J Clin Med. 8:18492019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Jin Z, Chang B, Wei Y, Yang Y, Zhang H,

Liu J, Piao L and Bai L: Curcumin exerts chondroprotective effects

against osteoarthritis by promoting AMPK/PINK1/Parkin-mediated

mitophagy. Biomed Pharmacother. 151:1130922022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Zhuang H, Ren X, Zhang Y, Li H and Zhou P:

β-Hydroxybutyrate enhances chondrocyte mitophagy and reduces

cartilage degeneration in osteoarthritis via the

HCAR2/AMPK/PINK1/Parkin pathway. Aging Cell. 23:e142942024.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Jie L, Shi X, Kang J, Fu H, Yu L, Tian D,

Mei W and Yin S: Protocatechuic aldehyde attenuates chondrocyte

senescence via the regulation of PTEN-induced kinase

1/Parkin-mediated mitochondrial autophagy. Int J Immunopathol

Pharmacol. 38:39463202412717242024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Glasson SS, Chambers MG, Van Den Berg WB

and Little CB: The OARSI histopathology initiative-recommendations

for histological assessments of osteoarthritis in the mouse.

Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 18(Suppl 3): S17–S23. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Merck: Pre-designed shRNA. https://www.sigmaaldrich.cn/CN/zh/semi-configurators/shrna?activeLink=productSearch.

|

|

28

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2 (−Delta Delta C (T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Rim YA, Nam Y and Ju JH: The role of

chondrocyte hypertrophy and senescence in osteoarthritis initiation

and progression. Int J Mol Sci. 21:23582020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Kuszel L, Trzeciak T, Richter M and

Czarny-Ratajczak M: Osteoarthritis and telomere shortening. J Appl

Genet. 56:169–176. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

31

|

Diekman BO, Sessions GA, Collins JA,

Knecht AK, Strum SL, Mitin NK, Carlson CS, Loeser RF and Sharpless

NE: Expression of p16INK4a is a biomarker of chondrocyte

aging but does not cause osteoarthritis. Aging Cell. 17:e127712018.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Liu Y, Duan J, Dang Y, Hao R, Wang H, Tan

E, Wang R, Li Y, Zhang S, Wang Y, et al: Remodeling of senescent

macrophages in synovium alleviates trauma- and aging-induced

osteoarthritis. Bioact Mater. 55:42–56. 2026.

|

|

33

|

Jiang T, Su S, Tian R, Jiao Y, Zheng S,

Liu T, Yu Y, Hua P, Cao X, Xing Y, et al: Immunoregulatory

orchestrations in osteoarthritis and mesenchymal stromal cells for

therapy. J Orthop Translat. 55:38–54. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Harman D: The biologic clock: The

mitochondria? J Am Geriatr Soc. 20:145–147. 1972. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Xie Z, Zhang X, Li Y and Zhu R:

Mitochondrial dysfunction drives cellular senescence: Molecular

mechanisms of inter-organelle communication. Exp Gerontol.

211:1129132025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Luo Y, Xu H, Xiong S and Ke J:

Understanding myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome

physical fatigue through the perspective of immunosenescence. Compr

Physiol. 15:e700562025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Abate M, Festa A, Falco M, Lombardi A,

Luce A, Grimaldi A, Zappavigna S, Sperlongano P, Irace C, Caraglia

M and Misso G: Mitochondria as playmakers of apoptosis, autophagy

and senescence. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 98:139–153. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Guo QQ, Wang SS, Jiang XY, Xie XC, Zou Y,

Liu JW, Guo Y, Li YH, Liu XY, Hao S, et al: Mitochondrial ROS

triggers mitophagy through activating the DNA damage response

signaling pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 122:e25028411222025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Abdeahad H, Moreno DG, Bloom S, Norman L,

Lesniewski LA and Donato AJ: MitoQ reduces senescence burden in

Doxorubicin-treated endothelial cells by reducing mitochondrial ROS

and DNA damage. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. September

30–2025.Epub ahead of print. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Hamacher-Brady A and Brady NR: Mitophagy

programs: Mechanisms and physiological implications of

mitochondrial targeting by autophagy. Cell Mol Life Sci.

73:775–795. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

41

|

Tufi R, Clark EH, Hoshikawa T, Tsagkaraki

C, Stanley J, Takeda K, Staddon JM and Briston T: High-content

phenotypic screen to identify small molecule enhancers of

Parkin-dependent ubiquitination and mitophagy. SLAS Discov.

28:73–87. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Rusilowicz-Jones EV, Jardine J, Kallinos

A, Pinto-Fernandez A, Guenther F, Giurrandino M, Barone FG,

McCarron K, Burke CJ, Murad A, et al: USP30 sets a trigger

threshold for PINK1-PARKIN amplification of mitochondrial

ubiquitylation. Life Sci Alliance. 3:e2020007682020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Zhang H, Xu T, Mei X, Zhao Q, Yang Q, Zeng

X, Ma Z, Zhou H, Zeng Q, Xu D and Ren H: PINK1 modulates Prdx2 to

reduce lipotoxicity-induced apoptosis and attenuate cardiac

dysfunction in heart failure mice with a preserved ejection

fraction. Clin Transl Med. 15:e701662025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Sedighi S, Liu T, O'Meally R, Cole RN,

O'Rourke B and Foster DB: Inhibition of cardiac p38 Highlights The

Role Of The Phosphoproteome In Heart Failure Progression. ACS

Omega. 10:36082–36097. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Meco M, Giustiniano E, Nisi F, Zulli P and

Agosteo E: MAPK, PI3K/Akt pathways, and GSK-3β activity in severe

acute heart failure in intensive care patients: An updated review.

J Cardiovasc Dev Dis. 12:2662025.

|

|

46

|

Su Z, Shu H, Huang X, Ding L, Liang F, Xu

Z, Zhu Z, Chen M, Wang X, Li G, et al: Rhapontigenin attenuates

neurodegeneration in a parkinson's disease model by downregulating

mtDNA-cGAS-STING-NF-κB-mediated neuroinflammation via

PINK1/DRP1-dependent microglial mitophagy. Cell Mol Life Sci.

82:3372025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Cao B, Fang L, Zhang Y, Lin C, Liu P,

Zhang H, Fan O, Xu M, Qin Z and Wang C: MitoQ alleviates

m.3243A>G-induced mitochondrial dysfunction by stabilizing PINK1

and enhancing mitophagy. J Genet Genomics. S1673-8527(25)00229-2.

August 22–2025.Epub ahead of print. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Wang FS, Kuo CW, Ko JY, Chen YS, Wang SY,

Ke HJ, Kuo PC, Lee CH, Wu JC, Lu WB, et al: Irisin mitigates

oxidative stress, chondrocyte dysfunction and osteoarthritis

development through regulating mitochondrial integrity and

autophagy. Antioxidants (Basel). 9:8102020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Luo D, Qi X, Xu X, Yang L, Yu C and Guan

Q: Involvement of p38 MAPK in Leydig cell aging and age-related

decline in testosterone. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne).

14:10882492023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Qigen X, Haiming C, Kai X, Yong G and

Chunhua D: Prenatal DEHP exposure induces premature testicular

aging by promoting leydig cell senescence through the MAPK

signaling pathways. Adv Biol (Weinh). 7:e23001302023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Zhang Z, Huang T, Chen X, Chen J, Yuan H,

Yi N, Miao C, Sun R and Ni S: Acetyl zingerone inhibits chondrocyte

pyroptosis and alleviates osteoarthritis progression by promoting

mitophagy through the PINK1/parkin signaling pathway. Int

Immunopharmacol. 161:1150552025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Bocheng L, Yongfu C, Junjie C, Ziqi L,

Lina G, Tingli Q, Li T and Qian Z: FoxO1/PINK1/Parkin-dependent

mitophagy mediates the chondroprotective effect of Guzhi Zengsheng

Zhitong decoction in osteoarthritis. Phytomedicine.

148:157322September 26–2025.Epub ahead of print. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Kang J, Jie L, Fu H, Zhang L, Lu G, Yu L,

Tian D, Liao T, Yin S, Xin R and Wang P: Adipose mesenchymal stem

cells derived exosomes ameliorates KOA Cartilage damage and

inflammation by activation of PINK1-mediated mitochondrial

autophagy. FASEB J. 39:e708112025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Wu T, Wang Y, Shen B, Guo K, Zhu Z, Liang

Y, Zeng J and Wu D: FBXO2 alleviates intervertebral disc

degeneration via dual mechanisms: Activating PINK1-Parkin mitophagy

and ubiquitinating LCN2 to suppress ferroptosis. Adv Sci (Weinh).

12:e061502025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Li Q, Gu H, Song K, Kong X, Li Y, Liu Z,

Meng Q, Liu K, Li X, Xie Q, et al: Lentinan rewrites extracellular

matrix homeostasis by activating mitophagy via mTOR/PINK1/Parkin

pathway in cartilage to alleviating osteoarthritis. Int J Biol

Macromol. 322:1469002025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Mohanan A, Washimkar KR and Mugale MN:

Unraveling the interplay between vital organelle stress and

oxidative stress in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Biochim Biophys

Acta Mol Cell Res. 1871:1196762024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Li Y, Chen H, Xie X, Yang B, Wang X, Zhang

J, Qiao T, Guan J, Qiu Y, Huang YX, et al: PINK1-mediated mitophagy

promotes oxidative phosphorylation and redox homeostasis to induce

drug-tolerant persister cancer cells. Cancer Res. 83:398–413. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

58

|

Zheng Y, Wei W, Wang Y, Li T, Wei Y and

Gao S: Gypenosides exert cardioprotective effects by promoting

mitophagy and activating PI3K/Akt/GSK-3β/Mcl-1 signaling. PeerJ.

12:e175382024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

59

|

Liu H, Ho PW, Leung CT, Pang SY, Chang

EES, Choi ZY, Kung MH, Ramsden DB and Ho SL: Aberrant mitochondrial

morphology and function associated with impaired mitophagy and

DNM1L-MAPK/ERK signaling are found in aged mutant Parkinsonian

LRRK2R1441G mice. Autophagy. 17:3196–3220. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

60

|

Wang W, Wang Q, Li W, Xu H, Liang X, Wang

W, Li N, Yang H, Xu Y, Bai J, et al: Targeting APJ drives

BNIP3-PINK1-PARKIN induced mitophagy and improves systemic

inflammatory bone loss. J Adv Res. 76:655–668. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar

|